Background

The European Commission (COM) proposed on July 5, 2023 a

lex specialis to amend the European Union’s (EU) regulatory framework for the deliberate release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) into the environment [

1]. The goal is to simplify the regulation for genetically modified (GM) plants developed with new genomic techniques (NGTs) by treating certain NGT-generated plants as

equivalent to conventionally bred plants. Over the past two years, the proposal passed through the initial legislative steps, with both the European Parliament and the Council adopting their respective negotiating positions. At this point, the trilogue negotiations have been initiated, where the Commission, Parliament, and Council work toward a final agreement. A timely moment, then, to thoroughly examine the core of the proposal: the criteria that supposedly justify equivalence. Those equivalence criteria are a crucial yet scarcely discussed aspect of the proposal [

2].

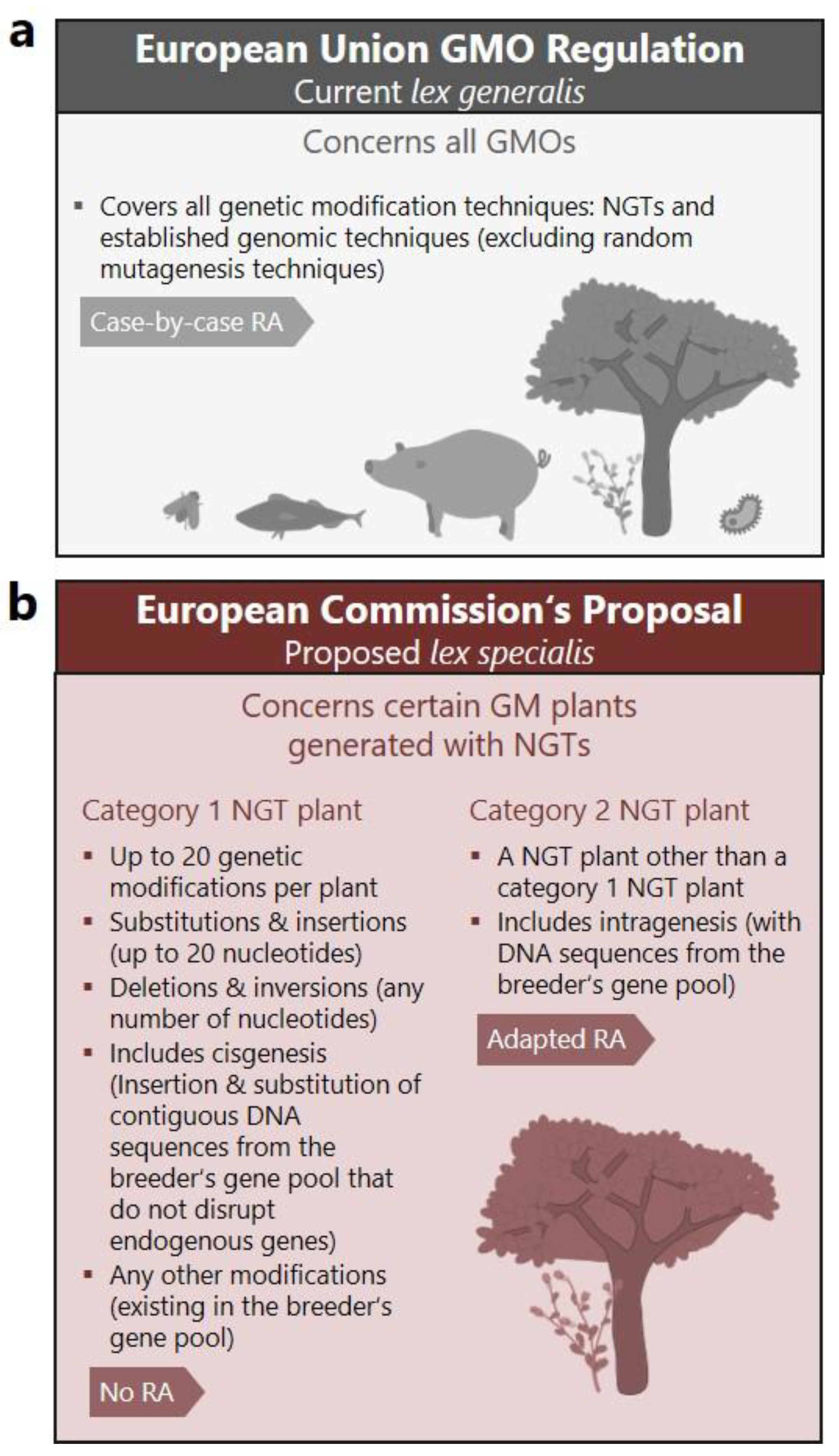

The proposal introduces a two-tier classification system for certain GM plants that have been generated with NGTs, while all other GM plants would continue to be regulated under Directive 2001/18/EC (

Figure 1) [

1]. GM plants meeting the criteria for “category 2 NGT plants” (NGT2) shall undergo an attenuated risk assessment on a case-by-case basis. For so-called “category 1 NGT plants” (NGT1) the proposal goes further—granting direct market access (cultivation and import) without risk assessment, requiring only a technical verification procedure. This approach rests on the central premise of the proposal, namely the assertion that the genetic modifications introduced into NGT1 plants “could also occur naturally or be produced by conventional breeding techniques” [

1]. On this basis, the proposal argues that a mandatory risk assessment is no longer necessary, as the potential associated risks are acceptable according to the principle of proportionality [

1].

Annex I of the proposal defines which GM plants can be approved under the suggested fast-track procedure for NGT1 plants, which bypasses risk assessment. In Annex I, one prerequisite and five criteria of genetic modifications are listed that would qualify GM plants as NGT1 plants (

Figure 1) [

3]. Of these, two criteria are threshold-based and define that (i) “no more than 20 genetic modifications” and (ii) “substitution or insertion of no more than 20 nucleotides” may be introduced per NGT1 plant [

3]. The aim of the criteria is to “exclude from category 1 of the proposal NGT plants with complex modifications unlikely to be obtainable by conventional breeding methods” [

4]. Thereby, Annex I forms the core of the proposal, underpinning all derived measures—including the waiving of risk assessment and safeguard mechanisms. Its scientific validity and internal logic are therefore of critical importance to meet a key objective of the proposal: “to ensure a high level of protection of human and animal health and the environment” [

1].

This policy brief evaluates the scientific basis behind the proposed threshold-based criteria categorizing NGT plants. We examine whether key biological factors—like genetic context, mutational bias, and relevant time scales—were adequately considered to justify an equivalence status for NGT1 plants with conventional breeding. We question whether a simplified, threshold-based classification can truly exclude complex genetic modifications and enable a coherent regulation. As genetic engineering increasingly intersects with synthetic biology and artificial intelligence (AI), we assess whether the proposals approach is fit for the future. Finally, we evaluate whether inclusion of proportional risks can uphold the EU’s high level of protection under the precautionary principle as enshrined in European primary law.

Beyond Thresholds: Why Genetic Context and Function Matters

Threshold values are a key regulatory trigger in the proposal and thus deserve a closer examination with regard to their origin and justification. The proposals accompanying technical paper explains the scientific basis for setting those threshold values for the types, size restrictions, and numerical limits of genetic modifications [

4]. To this end, genetic variability observed naturally or in conventional breeding is evaluated. Thereby, the technical paper draws on available experimental data that measures, for example, the average mutation rate per generation. This average mutation rate is used to define the key prerequisite of Annex I that a NGT1 plant should differ “from the recipient/parental plant by no more than 20 genetic modifications […] in any DNA sequence sharing sequence similarity with the targeted site” [

3]. In addition, the technical paper also notes that “insertions of more random sequences are typically of a length of less than ten nucleotides” [

4]. Based on these findings, the second threshold-based criterion in Annex I was introduced, which allows “substitutions or insertions of no more than 20 nucleotides” [

3,

4]. While the proposals technical paper focuses on the justification for these numerical limits—based on the naturally observed number and length of mutations—it completely ignores the more critical factor: the genetic context.

If only the average mutation rates or the size of random insertions are taken into account, neither the position in the genome nor the biological effects of genetic modifications are considered. However, both the position and sequence of a genetic change influence how likely it is that this variation would occur and persist under natural and breeding conditions. Mutations are not evenly distributed throughout the genome [

5,

6]. There are various biological influences that affect the likelihood of mutations in an unidirectional but unpredictable manner (reviewed by [

7]). Depending on selective pressure and structural constraints, genomic regions exhibit different mutation rates, which can be observed for example between coding and non-coding regions. The probability of multiple mutations occurring directly in the same gene or between linked gene groups is comparatively lower. Even taking into account powerful pre-breeding random mutagenesis approaches (like TILLING) that theoretically can promote mutations in every gene of interest, the number and outcome of mutations per gene would be still restricted considering technical limitations like lethality and phenotypic drawbacks (reviewed by [

8]). Relying on average mutation rates in the scientific reasoning, therefore, neither captures the known mutational bias nor the unpredictable progression of incremental mutations.

Furthermore, selective breeding relies on recombination to combine desired or separate unwanted mutations. During recombination, pieces of DNA are exchanged to produce new combinations of alleles. However, recombination occurs rarely within the same gene or among genes in close proximity (reviewed by [

9,

10]). Also, the probability of intragenic recombination is influenced by several factors and varies, e.g., between conserved and highly variable genes. The principles of linkage drag and linked genes represent a common drawback in conventional breeding, often requiring many generations before a linkage is resolved. In some crops significant parts of the genome are even inaccessible by breeding [

11,

12]. The greater the number of genes underlying a desired trait, the more difficult it becomes to combine all favorable alleles in the same genotype. Thus, certain combinations of genetic modifications can exceed the limits of intragenic recombination in conventional breeding.

Interestingly, in the argumentative derivation for the second threshold-based criterion –allowing insertions and substitutions of up to 20 nucleotides—the word “random” is used multiple times to describe small genetic changes that occur naturally. However, the term “random” is neither defined in more detail nor included in the final Annex I criterion. Generally,

random refers to something that occurs without specific pattern, purpose, or predictable outcome. But since nucleotides do not exist in isolation within the genome, the genetic context determines whether a mutation appears random or fits into a pattern with biological meaning. Of course, in a protein-coding region, each nucleotide triplet (codon) has a predictable outcome: it encodes a specific amino acid. Even if a random sequence of up to 20 nucleotides has been observed somewhere in the genome, this does not imply that the specific insertion of those nucleotides at a specific site is somewhat likely in conventional breeding. The biological function influences the selection or suppression of a mutation. The argument presented for Annex I—that the “theoretical probability that a random sequence” smaller than 21 nucleotides “may already occur elsewhere in the genome” [

4]—is disconnected from the biological reality of whether such a sequence behaves randomly or fits a functional pattern at another genomic location.

In general, the two threshold-based criteria of Annex I treat all genetic changes across the genome as equally likely. Although the scientific data already challenge the validity of this threshold-based approach, it could also be refuted using statistics. Statistical models typically assume a uniform distribution of mutations, based on average mutation rates and genome sizes using, for example, well-studied organisms such as

Arabidopsis thaliana [

5,

6]. The proposal’s initial scientific rationale relied on detectable average mutation rates per generation from conventional breeding, which causes random mutations—mostly single nucleotide polymorphisms [

4]. In contrast, the actually proposed criterion is based on the likelihood of specific mutations at specific genomic sites over unlimited generations. From a statistical perspective, these two scenarios involve fundamentally different variables. To illustrate this, one could compare it to lottery odds. The probability that some numbers will be drawn each week is 100%, similar to the assumption that mutations occur every generation. But the odds of winning the lottery are 1 in 140 million—and while the lottery balls are limited in number, the genome contains exceedingly more base pairs. With regard to the threshold-based criteria, the number of generations needed to achieve 20 specific changes would be biologically unrealistic in any relevant breeding or evolutionary timeframe. The proposed thresholds thus rely on an unsupported assumption: that any desired genetic change could eventually be produced through breeding or mutagenesis. Statistically, this assumption doesn’t hold.

It is fair to say that despite enormous technical advances in conventional breeding, plant breeders remain limited to imprecise and random genome repair outcomes. Besides the necessary selection to achieve desired traits, additional mutations may even be required for functionality. In contrast, the proposed threshold-based criteria in Annex I rely on oversimplified and unscientific assumptions—treating all mutations as equally likely and neglecting the genetic context, mutational bias, and breeding constraints. As a result, the proposed thresholds lack a solid genetic basis. Scientific and statistical evidence shows that the space of possible genetic changes is severely limited, making many desired genetic modifications unachievable through conventional breeding methods. Thus, the asserted equivalence between NGT1 plants and conventional bred plants, based on Annex I, is scientifically unjustified.

NGTs: From Targeted Errors to AI-Driven Design

In risk assessing NGT plants there is a need to evaluate the actual method used to create the genetic modification [

28], however Annex I makes no methodological distinction between techniques. NGTs, such as Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) systems, cut the DNA with nucleases to generate double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at targeted sites in the genome. DSBs are repaired predominately by non-homologous end joining mostly resulting in small random nucleotide insertions, substitutions, and deletions—mechanisms beyond human control [reviewed by [

13]]. This application is commonly known as site-directed nuclease 1 (SDN1), which requires subsequent selection procedures [reviewed by [

14]]. Avoiding DSBs, newer CRISPR/Cas tools—such as base and prime editing—use nickases to bypass error-prone repair pathways, which enables pre-determined nucleotide insertions [reviewed by [

15]]. Another technical advancement is multiplexing, which allows multiple simultaneous or stepwise NGT-generated mutations—even in complex genomic regions with gene redundancies [

16,

17,

18]. NGTs have thus evolved from mimicking random DNA errors to performing specific, purpose-driven genetic edits. CRISPR’s success lies not only in where it can edit, but also what it edits—enabling breakthroughs beyond the limits of traditional breeding.

For example, the precision of prime editing has been highlighted in rice: A classic polyhistidine-tag encoded by eighteen nucleotides has been precisely inserted upstream of a stop codon [

19]. This tag is not achievable through conventional breeding in relevant time frames due to the lack of selective pressure, absence of a visible phenotype, and the probability of six consecutive identical triplets is virtually zero. Furthermore, a precise insertion is essential to avoid disrupting protein function while enabling epitope-specific antibody binding. Prime editing, thus, makes tagging of any protein of interest feasible, a task unthinkable under natural circumstances or with conventional breeding. This genetic modification would however be granted NGT 1 status according to Annex I.

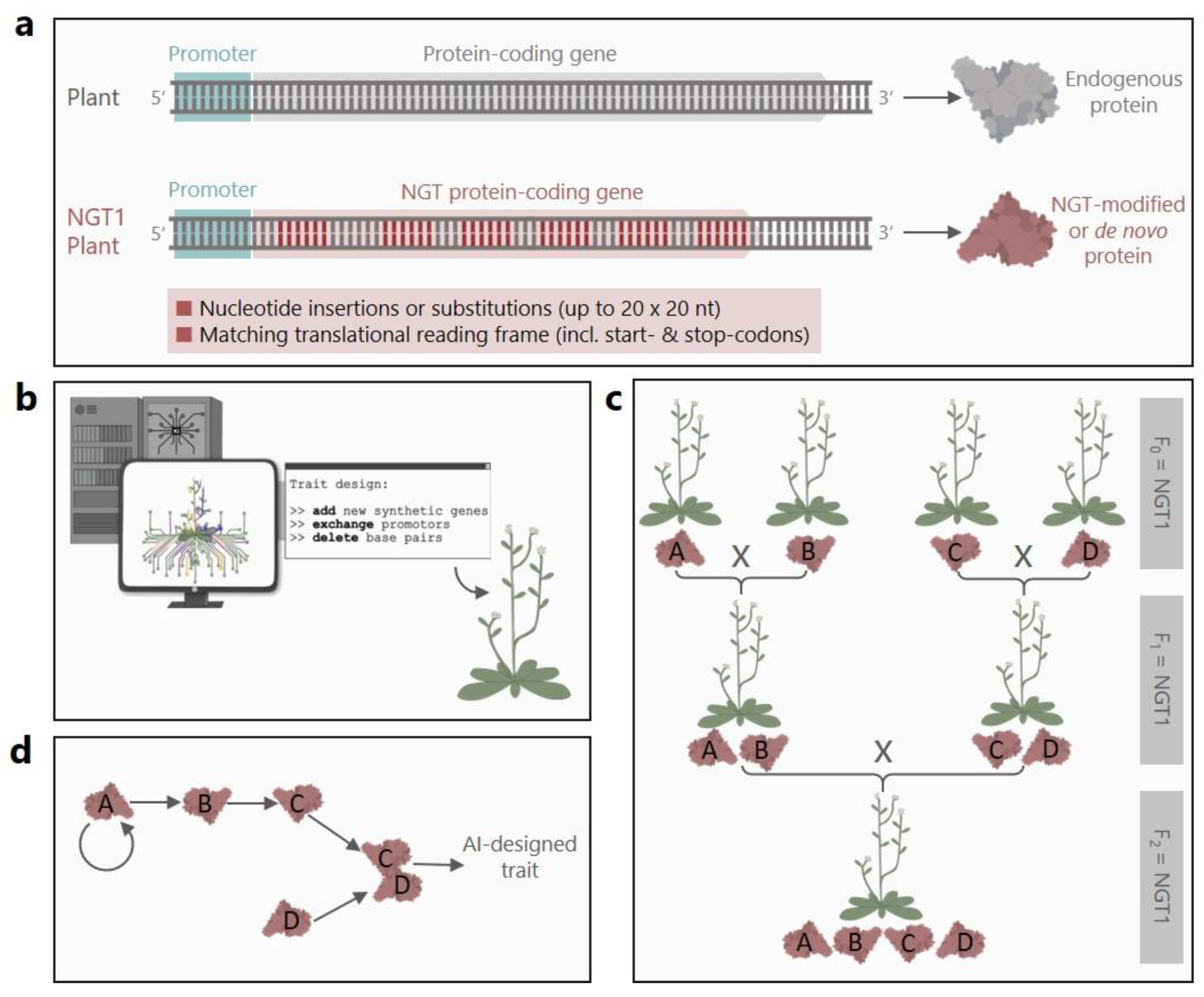

Annex I has another important flaw: It does not contain any spacing rules for the up to 20 possible genetic modifications per NGT1 plant. Theoretically a single endogenous nucleotide in between two modifications would be sufficient as a spacer. If 20 changes are possible side by side, we are no longer talking about the insertion (or substitution) of 20 nucleotides. We are talking about up to 400 precisely selected nucleotides—only interrupted by individual endogenous nucleotides—that could be translated into 140 amino acids. In this way, NGTs could be used not only to completely remodel protein functions—affecting, for example, the catalytic center of proteins or their intracellular transport, solubility, activation, binding, or recognition—but also to create virtually new proteins (

Figure 2a). Furthermore, such genomic interventions would not be limited to protein-coding genes, but could also redesign promoters or non-coding RNAs (

Supplementary Figure S1) [

20,

21,

22]. The process, how, when and where individual sequence components are combined and inserted by NGTs, is neither specifically considered nor relevant in the proposal—opening a technical loophole. Hence, without considering the arrangement or function of even small edits, the proposal effectively permits complex genomic alterations under the guise of equivalence.

Moreover, the proposal defines all sequence changes that are longer than 20 nt either as cisgenesis (contiguous DNA from crossable species), intragenesis (novel combinations from crossable species) or transgenesis (foreign DNA from non-crossable species). Whereas all sequences that are below this threshold slip through this definitional grit, with their origin or combination left unexamined. Thereby, the boundaries between supposedly small changes and sequence constellations that exhibit characteristics of intragenesis and transgenesis are becoming blurred or are abandoned altogether. And the possibility of combining the different Annex I criteria would considerably broaden the spectrum of complex genetic modifications. For example, a newly inserted, highly expressed cisgene could be further altered with up to 19 specific 20 nt insertions to enable the high expression of a modified protein. Consequently, GM plants falling into the realm of synthetic biology could receive NGT1 status, as the criteria of Annex I do not consider the constellation of individual changes within the genetic context.

When it comes to AI, the comparison of NGTs to conventional breeding is especially invalid. AI has become a transformative, rapidly evolving tool in the field of genetic engineering and the future will show how AI would use the leeway of Annex I [reviewed by [

23,

24]]. In the light of big data analyses, algorithms, and machine learning, AI-driven tools can analyze vast datasets of plant genomes and phenotypes, thereby identifying new targets for engineering (

Figure 2b). For instance, AI leverages the evolutionarily constrained protein sequence space to explore and optimize amino acid sequences and predict protein folding and functional structures [reviewed by [

23,

25]]. In this way, rather than modifying existing proteins,

de novo protein design enables the development of entirely new protein sequences to create molecules with desired properties [reviewed by [

26]]. There is also the possibility that there is no precedent for

de novo designed molecules and networks and that these may be completely

new to nature. This potential of AI-assisted NGT applications to actively expand the evolutionary sequence space necessitates a closer look at the synergistic functionality of genetic changes.

Importantly, the proposal also stipulates that NGT1 plants that are crossed with each other remain NGT1 plants. This also applies if the breeding product exceeds the threshold-based criteria of Annex I. Crossbreeding could thereby produce NGT1 plants that accumulate multiple

de novo proteins, allowing their combination and expression

ad libitum (

Figure 2c). Furthermore, it would be possible to combine

de novo proteins that act synergistically or as signaling cascades to elicit desired traits (

Figure 2d). In fact, the artificial assembly of multiple regulatory elements and molecules might even be considered synthetic biology especially when biological pathways and networks are systematically redesigned [reviewed by [

24]]. Thus, the overlooked convergence of NGTs and AI renders the proposals concept

ad absurdum, as context-free, threshold-based criteria would offer an virtually unrestrained design space for AI-tools.

Risks: Within the Scope of a Simplified Regulation

The proposal aims to abolish risk assessment for NGT1 plants. The proposal thus accepts potential risks associated with NGT1 plants by comparing them with potential risks posed by conventionally bred plants, which are considered within the scope of proportionality [

1]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has confirmed in response to an extensive analysis of the Annex I criteria by the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES) that the proposals “criteria are not meant to define levels of risk” [

2,

27]. Consequently, potential risks associated with NGT1 plants cannot be ruled out

per se. Even in individual cases or retrospectively, potential damage cannot be excluded or mitigated. For the NGT1 verification request, neither relevant information for risk assessment must be submitted, nor any monitoring measures are foreseen, nor would there be any mechanisms implemented to allow rejecting or retrospectively revoking a decision due to plausible risks. Taking into account the possible high exposure—assuming significant amounts of cultivation of a large variety of NGT1 plants in the European Union in the future—the potential hazard is considerable.

Moreover, the proposed approach of defining the Annex I criteria on a molecular basis, independent of the genetic context and functionality, falls short not only regarding the asserted equivalence to conventional breeding but also regarding potential risks. In general, the risk potential of an NGT plant is not only linked to the type, size, or extent of the genetic modification. The properties and potential risks of NGT-generated plants arise from a complex interplay between the molecular interactome, plant properties, and the receiving environment [reviewed by [

28]]. If the scientific validity of Annex I—especially the threshold-based classification—is subject to reasonable scientific doubt as argued above, this calls into question the approach of the entire proposal. All measures derived from the equivalence argument—including the abolishment of risk assessment and safeguard mechanisms—can no longer be regarded as reliable in individual cases.

Furthermore, the regulatory proposal uses an inappropriate comparator for NGTs: instead of a comparison to conventional breeding, the comparator should be other GM techniques. The latter would be in line with the 2018 ruling of the European Court of Justice, which clarifies that NGT plants are GMOs according to the European Directive 2001/18/EC [

29]. Importantly, Directive 2001/18/EC names diverse potential risks of GMOs to human health and the environment, including adverse impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems, harmful effects on target and non-target species, and far-reaching changes in agricultural practices [

30]. Overall, it must be assumed that individual NGT1-compatible plants could have a similar, if not greater, risk potential than plants produced by other genetic engineering techniques.

For example, while fitting NGT1 requirements, small non-coding RNAs (e.g., miRNAs) could be modified to act as an insecticide by triggering RNA interference (RNAi) in target and potentially also non-target organisms (

Supplementary Figure S1, for more details on such RNAi effects see [

22]). To design an effective NGT1-RNAi plant, coordinated and complex genetic modifications are necessary [

22], which can be considered synthetic biology and are nearly impossible to be achieved by conventional breeding. Besides, such NGT1-RNAi plants would have a clear risk profile similar to other insecticidal GM-plants like Bt-corn and should—in stark contrast to the proposal—be regulated in an analogous fashion.

Another critical point is that the adaptation of the GMO regulatory framework could be in place for decades to come. The proposal must therefore consider potential risks accompanying the rapid technical progress. Even if methods for certain complex modifications are currently not available, technical feasibility should only be a matter of time at the current pace of development. It is important to discuss which GM plants would currently be subject to the proposed regulation [

22]. However, the proposal would not only affect the currently most common SDN1 applications [

31]. In the future, genetic modifications in plants could be specifically designed to meet the proposed criteria for the NGT1 fast-track, bypassing the currently mandatory risk assessment. Therefore, only a case-by-case risk assessment can keep pace with technological progress to ensure a future-proof regulation.

Summary and Outlook

The COM’s proposal to simplify GMO regulation for plants produced with NGTs relies on threshold-based criteria to determine equivalence with conventional bred plants. These thresholds in Annex I—limiting the number, type and size of genetic modifications acceptable for NGT1 plants—are intended to exclude complex modifications unlikely to arise naturally or through conventional breeding. However, the proposal treats all genetic changes as equally probable, ignoring their position in the genome, biological function, and the mutational constraints of conventional breeding. This approach is thus based on overly simplified and scientifically unjustified assumptions. As a result, Annex I would cover NGT-generated modifications that go far beyond the reach of conventional breeding. This undermines the proposal’s core claim of equivalence and opens a serious regulatory gap.

At a time when AI is expanding the boundaries of what is possible with genetic engineering, it is remarkable that the proposal reverts to outdated breeding benchmarks to justify deregulation. An AI-assisted design enables multi-step NGT modifications that can create novel traits and proteins that might even appear new to nature. Crossbreeding between NGT1 plants can further accumulate such traits ad libitum. Therefore, the increasing convergence of NGTs, synthetic biology, and AI demands even more a regulatory approach that is future-proof, context-aware, and proportionate to potential risks—not one based on arbitrary numerical thresholds. In contrast, the proposal does not restrict the purpose or function of the genetic edits.

Accordingly, the exemption of NGT1 plants from risk assessment is not scientifically sound. The precautionary principle, which is enshrined in EU primary law (TFEU Article 191), requires that regulatory decisions account for uncertainty and scientific limits. Risks may be subtle, synergistic, or long-term, but without case-by-case evaluation or monitoring, they remain undetected. Yet, the proposal eliminates case-by-case risk assessment for NGT1 plants, despite admitting that its criteria are not designed to reflect risk. The assumption that risk is automatically low if thresholds are met is inconsistent with both science and the EU’s legal framework.

Instead of rushing to conclude the legislative process, a scientifically accurate and future-proof proposal is needed, which considers potential risks—both from the intended traits as well as NGT methods, including AI-driven tools.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

JM conceptualized the manuscript, analyzed the scientific literature, prepared the figures, wrote the original draft, and controlled the writing-review and -editing. SS conceptualized the manuscript, analyzed the scientific literature, and contributed to the manuscript writing. ME supervised and contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mathias Otto and Luise Zühl for critical comments regarding the manuscript and Finja Bohle for illustrations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

List of Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ANSES |

Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire |

| Cas |

CRISPR-associated system |

| COM |

European Commission |

| CRISPR |

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| DSB |

Double-stranded breaks |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| RA |

Risk assessment |

| GM |

Genetically modified |

| GMO |

Genetically modified organism |

| miRNA |

Micro RNA |

| NGT |

New genomic technique |

| NGT1 |

Category 1 NGT |

| NGT2 |

Category 2 NGT |

| nt |

Nucleotide |

| SDN1 |

Site-directed nucleases 1 |

References

- European Commission. Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625: COM(2023) 411 final; 2023.

- AGENCE NATIONALE DE SÉCURITÉ SANITAIRE (ANSES) de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail. OPINION of the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety on the scientific analysis of Annex I of the European Commission’s Proposal for a Regulation of 5 July 2023 on new genomic techniques (NGTs): Review of the proposed equivalence criteria for defining category 1 NGT plants; 2023.

- European Commission. ANNEXES to the Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625: COM(2023) 411 final ANNEXES 1 to 3; 2023.

- European Commission. Regulation on new genomic techniques (NGT)—Technical paper on the rationale for the equivalence criteria in Annex I: 2023/0226(COD), 14204/23; 2023.

- Ossowski S, Schneeberger K, Lucas-Lledó JI, Warthmann N, Clark RM, Shaw RG, et al. The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2010;327:92–4. [CrossRef]

- Weng M-L, Becker C, Hildebrandt J, Neumann M, Rutter MT, Shaw RG, et al. Fine-grained analysis of spontaneous mutation spectrum and frequency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2019;211:703–14. [CrossRef]

- Quiroz D, Lensink M, Kliebenstein DJ, Monroe JG. Causes of mutation rate variability in plant genomes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2023;74:751–75. [CrossRef]

- Szurman-Zubrzycka M, Kurowska M, Till BJ, Szarejko I. Is it the end of TILLING era in plant science? Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1160695. [CrossRef]

- Otto SP, Payseur BA. Crossover interference: shedding light on the evolution of recombination. Annual Review of Genetics. 2019;53:19–44. [CrossRef]

- Epstein R, Sajai N, Zelkowski M, Zhou A, Robbins KR, Pawlowski WP. Exploring impact of recombination landscapes on breeding outcomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:e2205785119. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-Y, Schreiber M, Bayer MM, Dawson IK, Hedley PE, Lei L, et al. The evolutionary patterns of barley pericentromeric chromosome regions, as shaped by linkage disequilibrium and domestication. Plant J. 2022;111:1580–94. [CrossRef]

- Des Danguy Déserts A, Bouchet S, Sourdille P, Servin B. Evolution of recombination landscapes in diverging populations of bread wheat. Genome Biol Evol 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bennett EP, Petersen BL, Johansen IE, Niu Y, Yang Z, Chamberlain CA, et al. INDEL detection, the ‘Achilles heel’ of precise genome editing: a survey of methods for accurate profiling of gene editing induced indels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:11958–81. [CrossRef]

- Cardi T, Murovec J, Bakhsh A, Boniecka J, Bruegmann T, Bull SE, et al. CRISPR/Cas-mediated plant genome editing: outstanding challenges a decade after implementation. Trends Plant Sci. 2023;28:1144–65. [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan SJ, Kumar M, Ramrao Devde P, Rai AC, Mishra AK, Singh PK, Siddique KHM. Progress in gene editing tools, implications and success in plants: a review. Front Genome Ed. 2023;5:1272678. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman M, Wei Z, Rohila JS, Zhao K. Multiplex genome-editing technologies for revolutionizing plant biology and crop Improvement. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:721203. [CrossRef]

- Nei M, Rooney AP. Concerted and birth-and-death evolution of multigene families. Annual Review of Genetics. 2005:121–52. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-León S, Gil-Humanes J, Ozuna CV, Giménez MJ, Sousa C, Voytas DF, Barro F. Low-gluten, nontransgenic wheat engineered with CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Biotechnol J. 2018;16:902–10. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Ding J, Zhu J, Xu R, Gu D, Liu X, et al. Prime editing-mediated precise knockin of protein tag sequences in the rice genome. Plant Commun. 2023;4:100572. [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen E, Wang J, Riaz M, Zhang L, Zuo K. Designing artificial synthetic promoters for accurate, smart, and versatile gene expression in plants. Plant Commun. 2023;4:100558. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vázquez LA, Méndez-García A, Chamu-García V, Rodríguez AL, Bandyopadhyay A, Paul S. The applications of CRISPR/Cas-mediated microRNA and lncRNA editing in plant biology: shaping the future of plant non-coding RNA research. Planta. 2023;259:32. [CrossRef]

- Bohle F, Schneider R, Mundorf J, Zühl L, Simon S, Engelhard M. Where does the EU-path on new genomic techniques lead us? Front. Genome Ed. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Winnifrith A, Outeiral C, Hie BL. Generative artificial intelligence for de novo protein design. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2024;86:102794. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D, Xu F, Wang F, Le L, Pu L. Synthetic biology and artificial intelligence in crop improvement. Plant Commun. 2024:101220. [CrossRef]

- Hayes T, Rao R, Akin H, Sofroniew NJ, Oktay D, Lin Z, et al. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. Science. 2025:eads0018. [CrossRef]

- Huang P-S, Boyken SE, Baker D. The coming of age of de novo protein design. Nature. 2016;537:320–7. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms. Scientific opinion on the ANSES analysis of Annex I of the EC proposal COM (2023) 411 (EFSA-Q-2024-00178). EFSA Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eckerstorfer MF, Grabowski M, Lener M, Engelhard M, Simon S, Dolezel M, et al. Biosafety of genome editing applications in plant breeding: Considerations for a focused case-specific risk assessment in the EU. BioTech 2021. [CrossRef]

- European Court of Justice. Judgement of the Court (Grand Chamber) in Case C-528/16. 2018, July 25.

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2001/18/EC on the deliberate release into the environment of genetically modified organisms and repealing Council Directive 90/220/EEC; 2001.

- Parisi C, Rodríguez-Cerezo E. Current and future market applications of new genomic techniques. Publications Office of the European Union 2001. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).