Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Analysis

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Real-Life Consenting Behaviours

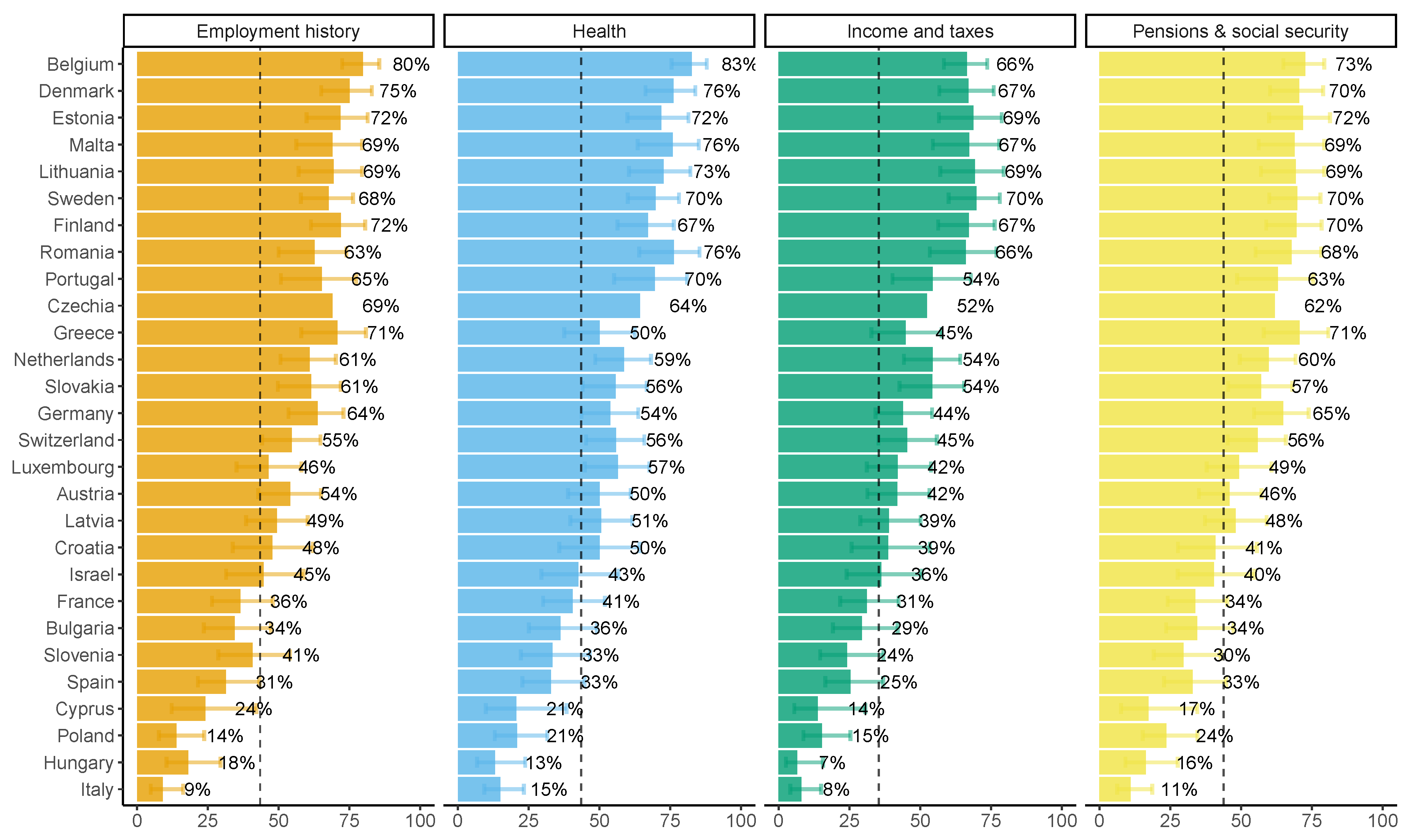

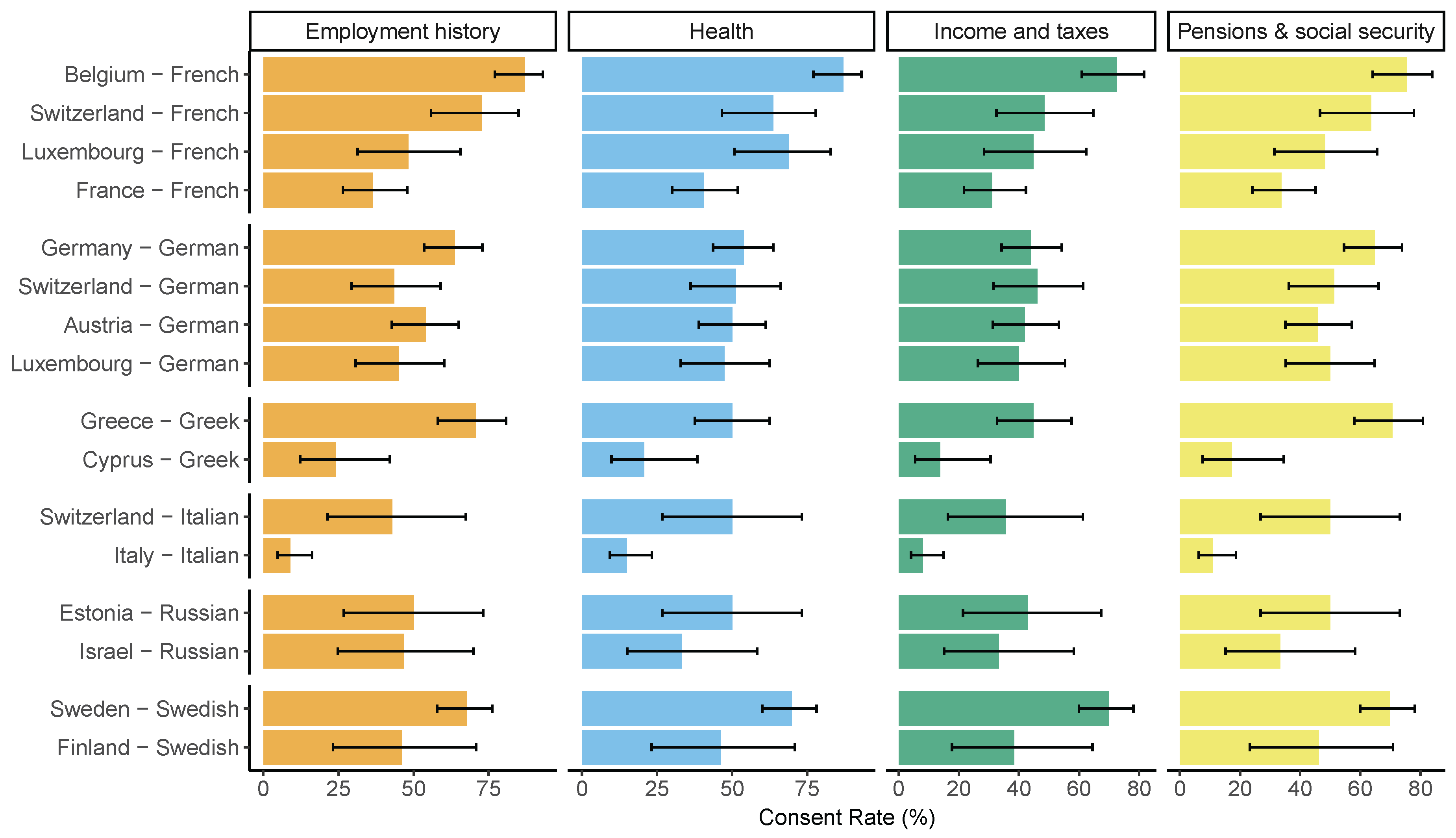

2.3. Hypothetical Willingness to Consent to Data Linkage

"Given the conditions of absolute confidentiality, anonymity and academic use only, in the case that SHARE would invite you to link your interview responses to administrative information on [data domain] in the future, would you be willing to give your consent? (Yes / No)"

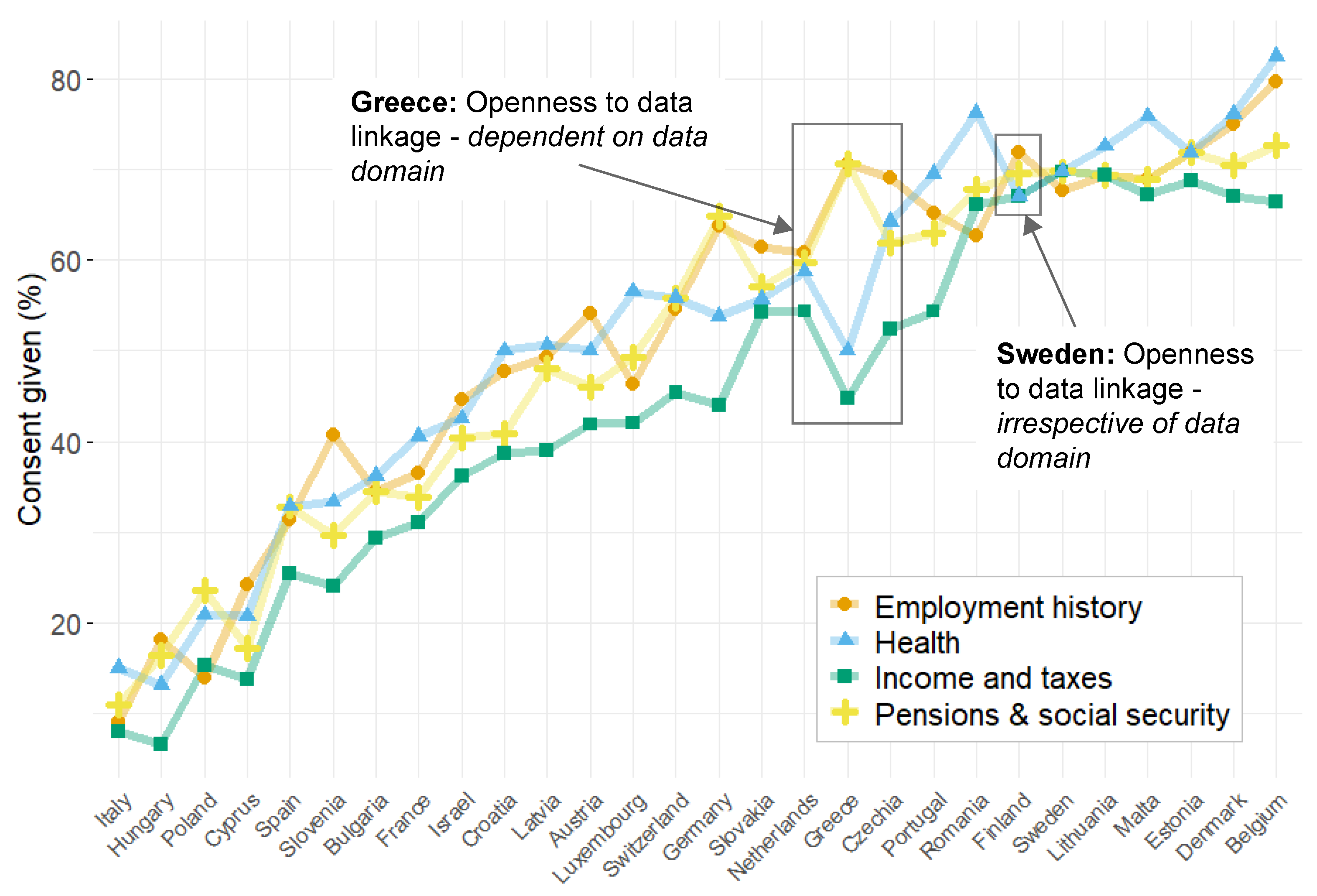

- In some countries consent was more dependent on data domain than in others, where individuals show a greater tendency towards a blanket yes/no to data linkage consent regardless of domain

- Ranking of domain consent likelihood was not consistent across countries. While the average country respondent is almost always least likely to consent to linking income and tax information, the other domains switch ranks between countries.

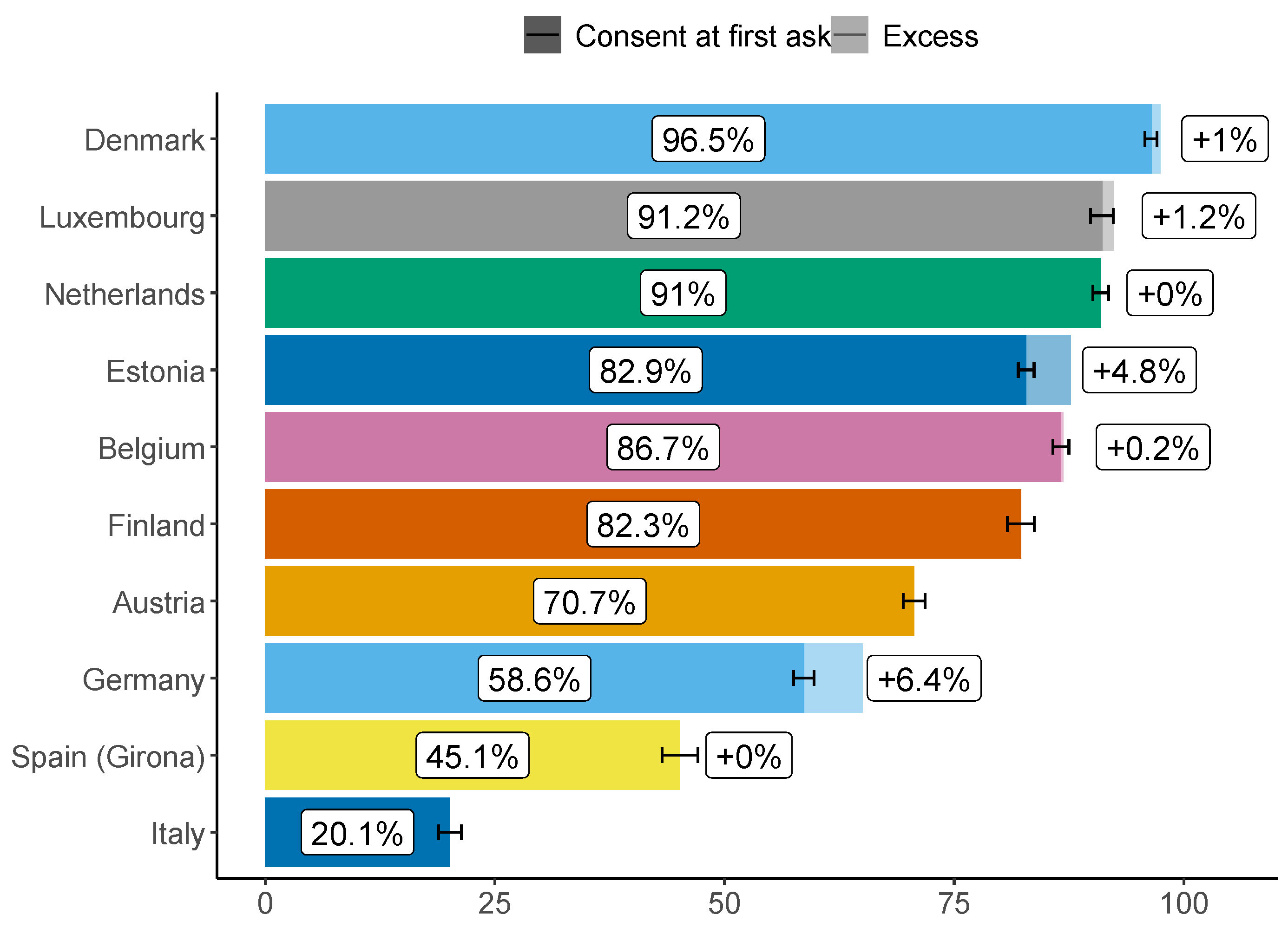

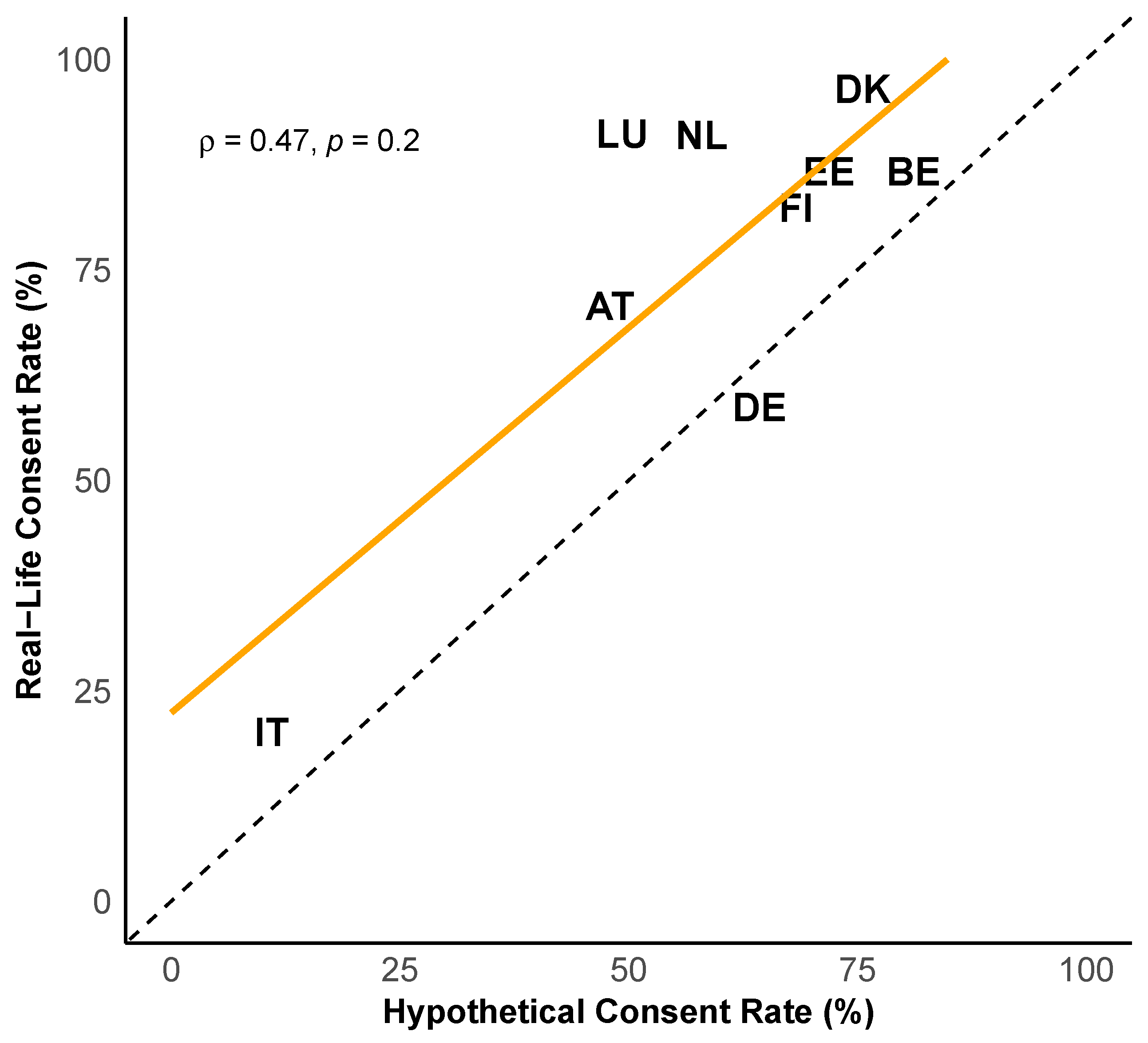

2.4. Comparing Real-Life and Hypothetical Consent Rates

3. Discussion

3.1. Individual Differences in Consent Behaviour

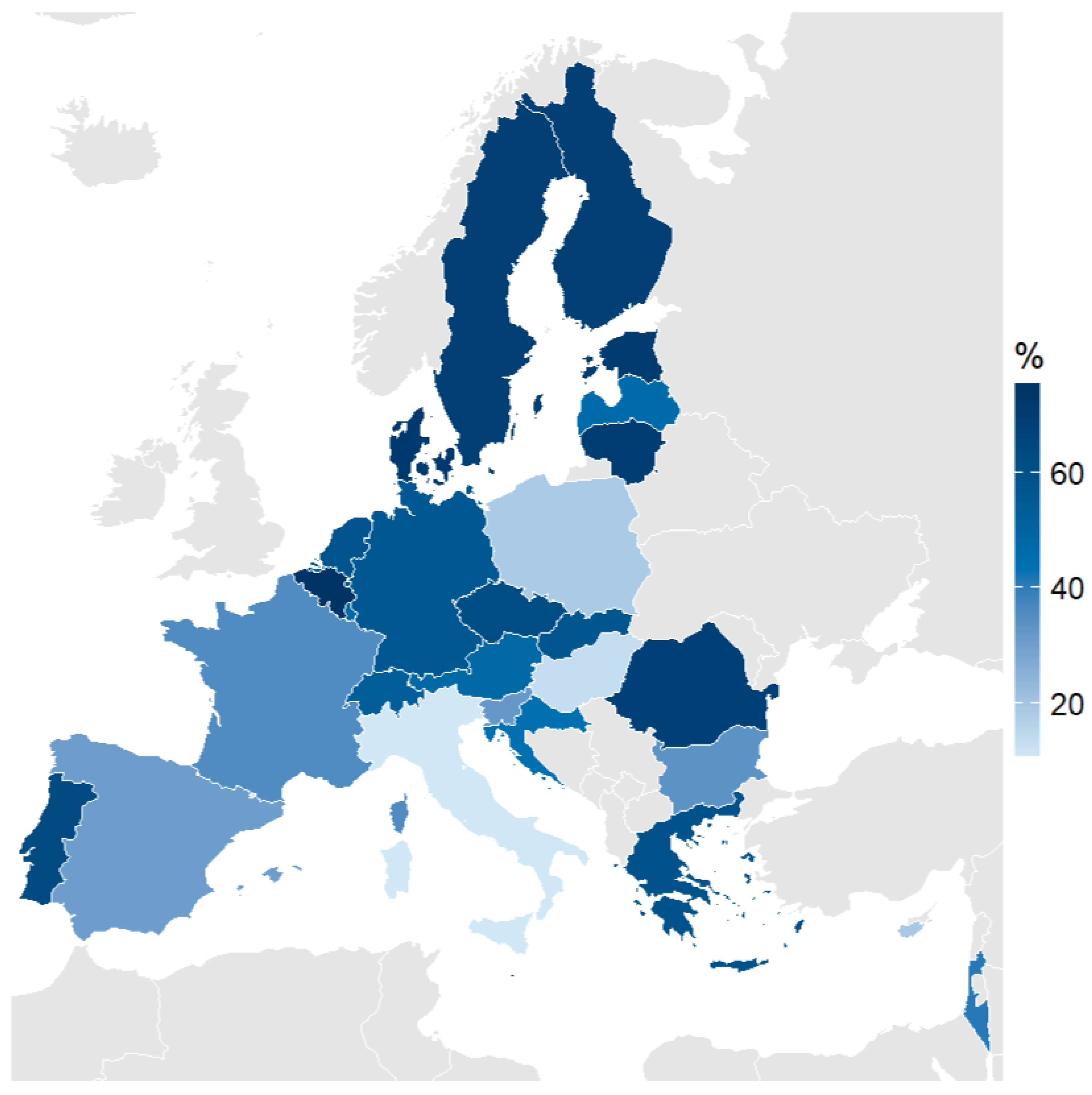

3.2. Cross-National Variations and the Role of Macro-Level Factors

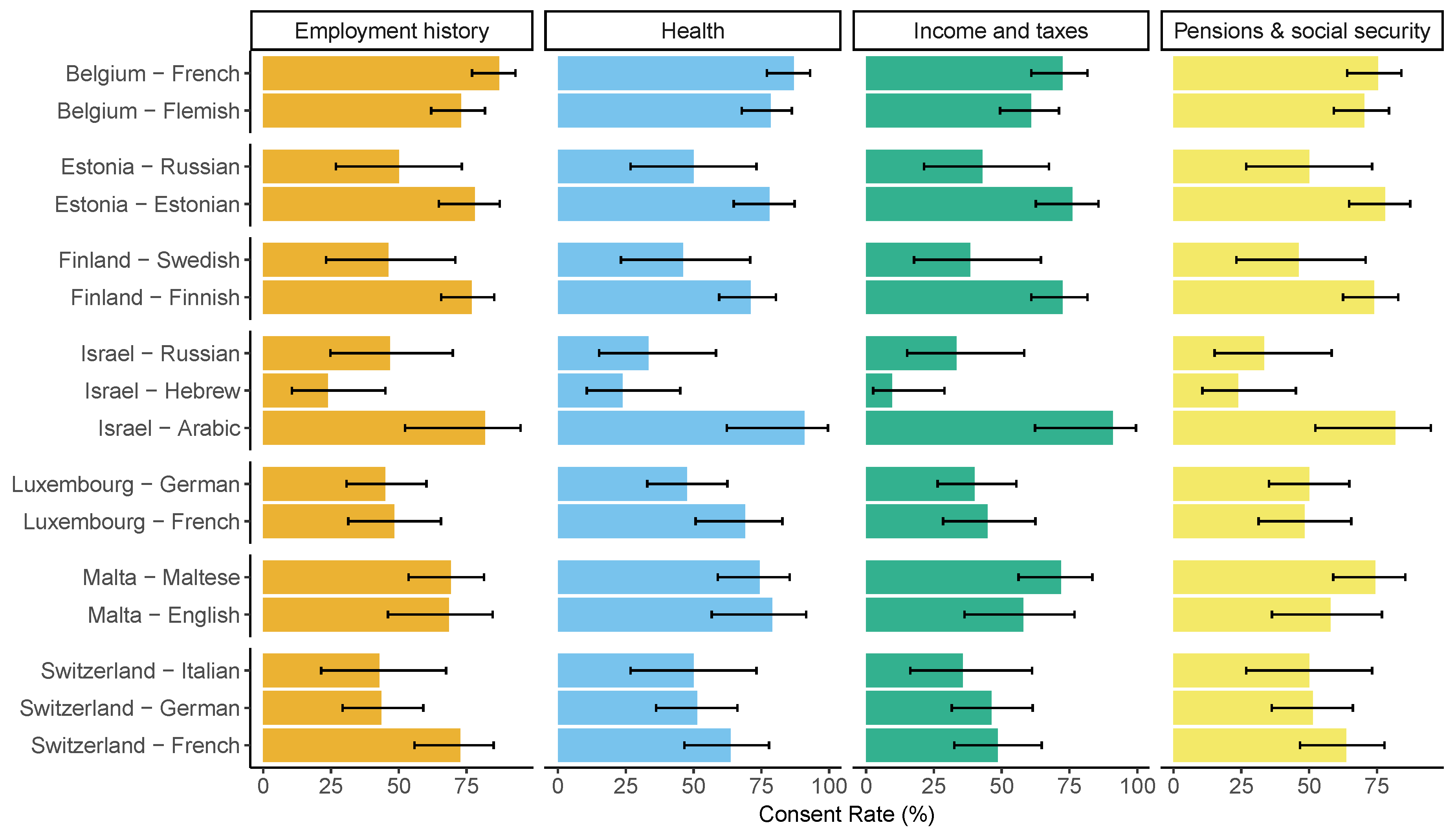

3.3. Language Group Differences

3.4. Temporal Discrepancies and Familiarity Effects

3.5. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

| Country | Consent procedure |

|---|---|

| Austria | Respondents have been asked verbally for consent to link their interview responses to the Austrian Social Security Institution and the Public Employment Service Austria since Wave 5 (except Wave 6 and Wave 7). All respondents have only been asked once for their consent. |

| Belgium | Asked for the first time in Wave 7 for consent. With the implementation of the GDPR guidelines in 2018, adaptations needed to be made to the consent documents and all respondents had to be asked again in Wave 9. Written consent was obtained for a linkage with the Belgian Statistical Office (Statbel). As interviews are conducted in French and Dutch, consent documents were provided in both languages. |

| Spain (Girona) | In the region of Girona, respondents were asked within a special project to consent to the linkage of SHARE data with some of their official medical records. The consent was obtained in written form and only in Wave 6. |

| Denmark | Has conducted linkage since Wave 5. Before GDPR (Wave 5 to Wave 7), consent was not required under Danish law. From Wave 8 onwards, consent was obtained in written form for a linkage with Statistics Denmark and the Danish Health Data Authority. In Wave 8, all respondents were asked; in Wave 9, only those who had not consented in Wave 8 were asked. |

| Estonia | Has been asking for consent since Wave 5 for linkage with Statistics Estonia and several health data registries. In Wave 5, all respondents were asked; in Waves 6 and 7, only those who had not consented before. In Wave 8, all respondents had to be asked again due to GDPR; in Wave 9, only those who had not consented in Wave 8 were asked. The consent question and material were provided in Russian and Estonian. |

| Finland | Introduced a record linkage project in Wave 7 and asked verbally for consent. With GDPR, the consent request changed to written consent in Wave 8 and all respondents were asked again. The consent covers linkage with Statistics Finland, Finnish Center for Pensions (ETK), and Finnish Social Insurance Institution (Kela). In Wave 9, only those who had not consented before were asked. Consent material was provided in Finnish and Swedish. |

| Germany | Started a linkage project in Wave 3, but only consent data from Wave 5 onwards is used. Written consent was asked for linkage from Wave 3 to Wave 9 (except Wave 7) with data from the German Pension Insurance. Respondents were re-asked if they had not consented or if data could not be linked. From Wave 8 onwards, the consent request was restricted to those who had not refused twice already and changed from passive to active request. |

| Italy | Respondents were asked for consent to linkage with the Italian Social Security Institution (INPS) for the first time in Wave 8. Written consent was obtained from all respondents. The request was repeated in Wave 9 for those not asked before. |

| Luxembourg | Introduced a verbal consent question for linkage with the General Inspectorate of Social Security (IGSS) in Wave 5. All respondents received the question in Waves 5 and 6. Consent material was provided in German and French. |

| Netherlands | Verbal consent obtained in Waves 5 and 9 for linkage with Statistics Netherlands. In Wave 9, an additional information sheet was provided, and only those who had not been asked before received the consent request. |

| Country | At first ask (%) | Excess (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 70.67 | 0.00 |

| Germany | 58.64 | 7.92 |

| Netherlands | 91.00 | 0.00 |

| Spain (Girona) | 45.15 | 0.00 |

| Italy | 20.08 | 0.00 |

| Denmark | 96.50 | 1.00 |

| Belgium | 86.66 | 4.49 |

| Luxembourg | 91.15 | 4.08 |

| Estonia | 82.86 | 8.19 |

| Finland | 82.31 | 2.74 |

| Characteristic | Employment History | Health | Income and Taxes | Pensions and Social Security | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRUE (N=1053) | FALSE (N=910) | TRUE (N=1057) | FALSE (N=906) | TRUE (N=902) | FALSE (N=1061) | TRUE (N=1025) | FALSE (N=938) | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 575 (54.6%) | 550 (60.4%) | 580 (54.9%) | 545 (60.2%) | 490 (54.3%) | 635 (59.8%) | 558 (54.4%) | 567 (60.4%) |

| Male | 478 (45.4%) | 360 (39.6%) | 477 (45.1%) | 361 (39.8%) | 412 (45.7%) | 426 (40.2%) | 467 (45.6%) | 371 (39.6%) |

| Age Category | ||||||||

| 50–65 | 468 (44.4%) | 387 (42.5%) | 465 (44.0%) | 390 (43.0%) | 395 (43.8%) | 460 (43.4%) | 455 (44.4%) | 400 (42.6%) |

| 66–80 | 511 (48.5%) | 462 (50.8%) | 513 (48.5%) | 460 (50.8%) | 434 (48.1%) | 539 (50.8%) | 494 (48.2%) | 479 (51.1%) |

| 81+ | 72 (6.8%) | 56 (6.2%) | 77 (7.3%) | 51 (5.6%) | 71 (7.9%) | 57 (5.4%) | 74 (7.2%) | 54 (5.8%) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.5%) | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.5%) | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.5%) |

| Education Level | ||||||||

| Low | 167 (15.9%) | 151 (16.6%) | 172 (16.3%) | 146 (16.1%) | 151 (16.7%) | 167 (15.7%) | 163 (15.9%) | 155 (16.5%) |

| High | 421 (40.0%) | 259 (28.5%) | 404 (38.2%) | 276 (30.5%) | 346 (38.4%) | 334 (31.5%) | 397 (38.7%) | 283 (30.2%) |

| Medium | 430 (40.8%) | 439 (48.2%) | 439 (41.5%) | 430 (47.5%) | 373 (41.4%) | 496 (46.7%) | 427 (41.7%) | 442 (47.1%) |

| Missing | 35 (3.3%) | 61 (6.7%) | 42 (4.0%) | 54 (6.0%) | 32 (3.5%) | 64 (6.0%) | 38 (3.7%) | 58 (6.2%) |

| Minority Language | ||||||||

| Yes | 48 (4.6%) | 38 (4.2%) | 50 (4.7%) | 36 (4.0%) | 42 (4.7%) | 44 (4.1%) | 45 (4.4%) | 41 (4.4%) |

| No | 1005 (95.4%) | 872 (95.8%) | 1007 (95.3%) | 870 (96.0%) | 860 (95.3%) | 1017 (95.9%) | 980 (95.6%) | 897 (95.6%) |

References

- Bacher, Johann. 2023. Willingness to consent to data linkage in austria - results of a pilot study on hypothetical willingness for different domains. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. [CrossRef]

- Baghal, Tarek Al, Gundi Knies, and Jonathan Burton. 2014, 12. Linking administrative records to surveys: Differences in the correlates to consent decisions. Understanding Society Working Paper Series. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Michael, Thorsten Kneip, Giuseppe De Luca, and Annette Scherpenzeel. 2019. Survey participation in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE Working Paper Series, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Michael, Thorsten Kneip, Giuseppe De Luca, and Annette Scherpenzeel. 2022. Survey participation in the eighth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE Working Paper Series. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Michael, Melanie Wagner, and Axel Börsch-Supan. 2021. Share wave 8 methodology: Collecting cross-national survey data in times of covid-19. Munich: MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

- Bethmann, Arne and Michael Bergmann. 2023. Share sampling guide 10. SHARE Working Paper Series. [CrossRef]

- Beuthner, Christoph, Florian Keusch, Henning Silber, Bernd Weiß, and Jette Schröder. 2022, 1. Consent to data linkage for different data domains – the role of question order, question wording, and incentives. SocArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bohensky, Megan A., Damien Jolley, Vijaya Sundararajan, Sue Evans, David V. Pilcher, Ian Scott, and Caroline A. Brand. 2010. Data linkage: A powerful research tool with potential problems. BMC Health Services Research 10. [CrossRef]

- Brand, Türknur and Ahmet Sinan Türkyılmaz. 2024, 5. Investigating the determinants that influence consent behavior for linking survey data with administrative records. Fiscaoeconomia 8, 495–516. [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, Axel, Martina Brandt, Christian Hunkler, Thorsten Kneip, Julie Korbmacher, Frederic Malter, Barbara Schaan, Stephanie Stuck, and Sabrina Zuber. 2013, August. Data resource profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology 42(4), 992–1001. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, Márcia Elizabeth Marinho, Cláudia Medina Coeli, Miriam Ventura, Marisa Palacios, Mônica Maria Ferreira Magnanini, Thais Medina Coeli Rochel Camargo, and Kenneth Rochel Camargo. 2012. Informed consent for record linkage: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Ethics 38. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Kate M., Kelvin Jordan, Rosie J. Lacey, Mark Shapley, and Clare Jinks. 2004, 6. Patterns of consent in epidemiologic research: Evidence from over 25,000 responders. American Journal of Epidemiology 159, 1087–1094. [CrossRef]

- Fobia, Aleia Clark, Jessica Holzberg, Casey Eggleston, Jennifer Hunter Childs, Jenny Marlar, and Gerson Morales. 2019. Attitudes towards data linkage for evidence-based policymaking. Public Opinion Quarterly 83, 264–279. [CrossRef]

- Herold, Imke, Michael Bergmann, and Arne Bethmann. Trust, concerns and attitudes: Examples for respondent (non-)cooperation in SHARE. Survey Research Methods.

- Herold, Imke, Michael Bergmann, and Arne Bethmann. 2023, 1. Trust in surveys, income non-response and linkage consent - the SHARE perspective. Discussion Paper. [CrossRef]

- Herold, Imke, Yuri Pettinicchi, and Daniel Schmidutz. 2021. Harmonising record linkage procedures in share. In M. Bergmann, M. Wagner, and A. Börsch-Supan (Eds.), SHARE Wave 8 Methodology: Collecting cross-national survey data in times of COVID-19. MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

- Huang, Nicole, Shu Fang Shih, Hsing Yi Chang, and Yiing Jenq Chou. 2007. Record linkage research and informed consent: Who consents? BMC Health Services Research 7. [CrossRef]

- Jäckle, Annette, Kelsey Beninger, Jonathan Burton, and Mick P. Couper. 2021, 1. Understanding Data Linkage Consent in Longitudinal Surveys, pp. 122–150. wiley. [CrossRef]

- Jäckle, Annette, Jonathan Burton, Mick P Couper, Thomas F Crossley, and Sandra Walzenbach. 2023, 11. Survey consent to administrative data linkage: Five experiments on wording and format. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology. [CrossRef]

- Knies, Gundi and Jonathan Burton. 2014. Analysis of four studies in a comparative framework reveals: Health linkage consent rates on british cohort studies higher than on uk household panel surveys. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, Frauke, Joseph W. Sakshaug, and Roger Tourangeau. 2016, 3. The framing of the record linkage consent question. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, Tarek. 2014, 11. Variation within households in consent to link survey data to administrative records: Evidence from the uk millennium cohort study. Technical report, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Peycheva, Darina, George Ploubidis, and Lisa Calderwood. 2021, 1. Determinants of Consent to Administrative Records Linkage in Longitudinal Surveys: Evidence from Next Steps, pp. 151–180. wiley. [CrossRef]

- Sakshaug, Joseph W and Frauke Kreuter. 2012. Assessing the magnitude of non-consent biases in linked survey and administrative data. Survey Research Methods 6, 113–122.

- Sakshaug, J W, A Schmucker, F Kreuter, M P Couper, and L Holtmann. 2021. Respondent understanding of data linkage consent survey methods: Insights from the field. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024a. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 1. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024b. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 2. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024c. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 3 – SHARELIFE. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024d. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 4. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024e. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 5. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024f. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 6. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024g. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 7. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024h. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2024i. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 9. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC. 2025a. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 4-10. Field Rehearsal & Pretest Data. Release version: 1. Internal data set. SHARE-ERIC, Munich.

- SHARE-ERIC. 2025b. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 5-9. Linkage Data. Release version: 1. Internal data set. SHARE-ERIC, Munich.

- Walzenbach, Sandra, Jonathan Burton, Mick P. Couper, Thomas F. Crossley, and Annette Jäckle. 2023, 6. Experiments on multiple requests for consent to data linkage in surveys. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 11, 518–540. [CrossRef]

| Age Category | Education Level | Minority | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | N | Female | 50–65 | 66–80 | 81+ | Low | Medium | High | Missing | Language | Consent |

| Austria | 5608 | 56.3% | 52.5% | 37.7% | 9.8% | 22.1% | 50.5% | 26.5% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 70.7% |

| Germany | 7302 | 51.5% | 59.5% | 33.1% | 7.3% | 11.5% | 56.4% | 32.0% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 58.7% |

| Netherlands | 4251 | 54.8% | 48.6% | 41.7% | 9.7% | 45.1% | 24.9% | 27.2% | 2.8% | 0.0% | 91.0% |

| Spain (Girona) | 4014 | 54.0% | 49.1% | 41.7% | 9.1% | 76.7% | 19.7% | 3.6% | 0.6% | 5.0% | 45.4% |

| Italy | 3923 | 56.1% | 52.0% | 43.9% | 4.0% | 66.7% | 23.8% | 9.4% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 20.1% |

| Denmark | 2941 | 53.8% | 44.2% | 44.6% | 11.3% | 14.8% | 37.5% | 47.5% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 96.5% |

| Belgium | 5923 | 55.2% | 50.3% | 36.8% | 12.8% | 34.0% | 28.3% | 37.0% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 86.3% |

| Luxembourg | 2024 | 53.3% | 59.5% | 31.9% | 8.6% | 45.7% | 34.7% | 19.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 91.2% |

| Estonia | 8396 | 59.4% | 51.3% | 38.0% | 10.7% | 24.6% | 52.2% | 23.2% | 0.1% | 18.9% | 82.7% |

| Finland | 2654 | 52.6% | 45.6% | 45.1% | 9.3% | 27.3% | 33.2% | 39.4% | 0.0% | 4.7% | 82.4% |

| Consent at first ask | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education level (Ref: Low) | ||

| High | 0. | (0.035) |

| Medium | 0. | (0.032) |

| Minority language speaker | 0. | (0.066) |

| Age group (Ref: 50 to 65) | ||

| 66 to 80 | 0. | (0.027) |

| 81+ | -0. | (0.041) |

| First consent (Ref: 2013) | ||

| 2015 | -0. | (0.087) |

| 2017 | -0.134 | (0.075) |

| 2019 | -0. | (0.048) |

| 2021 | -0. | (0.041) |

| Male gender | -0.004 | (0.025) |

| Constant | 1. | (0.406) |

| Observations | 44,174 | |

| Bayesian Inf. Crit. | 42,216.270 | |

| Social security | Income | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Employment | and pensions | and taxes | |||||

| Consent | S.E. | S.E. | S.E. | S.E. | ||||

| Education level (Ref: Low) | ||||||||

| Medium | -0.077 | (0.156) | -0.120 | (0.158) | -0.081 | (0.156) | -0.200 | (0.156) |

| High | 0.175 | (0.162) | 0.272 | (0.164) | 0.180 | (0.161) | -0.011 | (0.161) |

| Minority Language Speaker | -0.126 | (0.275) | -0.289 | (0.274) | -0.402 | (0.271) | -0.316 | (0.272) |

| Age group (Ref: 50 to 65) | ||||||||

| 66 to 80 | -0.161 | (0.110) | -0.165 | (0.111) | -0.168 | (0.109) | -0.179 | (0.110) |

| 81+ | 0.044 | (0.223) | -0.145 | (0.221) | -0.004 | (0.220) | 0.185 | (0.220) |

| Male gender | 0. | (0.104) | 0. | (0.105) | 0. | (0.103) | 0. | (0.103) |

| sd(Country) | 0.873 | 0.945 | 0.898 | 0.928 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).