1. Introduction

Questionnaire development is one of the most crucial tasks in the survey lifecycle, alongside sampling and non-response mitigation, as it is extremely difficult to make corrections after the fact. If we sample—and consequently interview—the wrong people, our results will be biased due to a lack of representativeness in our data. We will have collected data on a different group of people to the one we wanted to investigate. Asking the wrong questions, or questions that are poorly designed or worded, will likely cause

measurement error, meaning that we will not get answers to the questions we originally intended, leading to further bias in the results

Groves et al. (

2009);

Groves and Lyberg (

2010);

Biemer and Lyberg (

2003);

Lyberg and Weisberg (

2016).

This is not a trivial matter. Biased results can lead to scientific artefacts and incorrect policy advice, causing real-world issues. This is particularly relevant in large-scale survey infrastructures that form the basis of much policy-relevant research, such as the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe

Börsch-Supan et al. (

2013) [SHARE].

1 With over 20,000 data users at universities, research institutes, national and supra-national agencies around the world, and hundreds of new publications every year, the quality of SHARE data is not only of academic interest, but also has real-world impact.

Following thorough conceptual work and diligence in operationalising the questions of interest,

pretesting is a core part of implementing new and revised questions as part of a high-quality survey instrument

Bradburn et al. (

2004). While quantitative pretesting is an important step in evaluating the technical feasibility of a particular question or set of questions, it provides only limited insight into quality issues with regard to

if and

how respondents understand questions. From a measurement perspective these issues are key, as they can render the collected data unusable for any further analysis. Therefore, it is prudent to complement quantitative pretests with open forms of pretesting. This allows for a more in-depth analysis of specific problems respondents may have understanding and answering the survey questions, providing a basis for revisions that improve measurement quality.

In preparation for the 10th panel wave of SHARE, which was collected in 2025, the questionnaire module on IT usage was revised to extend its scope and update question wording in line with technological developments. To evaluate the questionnaire revisions Qualitative Pretest Interviews QPIs; see

Bethmann et al. (

2019);

Buschle et al. (

2022) were conducted. The QPI is similar to the Cognitive Interview CI; see

Willis (

2015,

2005,

2016);

Lenzner et al. (

2024) in its aim to evaluate survey questionnaires by involving potential respondents in a more open form of pretesting than quantitative pretests. Unlike the CI the QPI focuses on a dialogic clarification of meaning, using qualitative-interpretive methodology in a sociological context see also

Miller et al. (

2014).

When revising the SHARE IT module using QPIs, we had two objectives. Firstly, with regard to the development of the questionnaire module itself, we aimed to evaluate how respondents understood the questions and whether they answered them as intended. During the QPI, we also sought suggestions for improving the questionnaire based on our interactions with respondents. Even when direct adjustment of the questions was not possible, we documented issues relating to understanding the questions and the underlying concepts, which could be useful when interpreting subsequent analyses of the survey data.

Secondly, we aimed to test and further develop the QPI method in the context of a large-scale survey such as SHARE. QPIs have previously been used and proven effective in smaller, mostly one-off studies. To ensure that the qualitative interviews were conducted consistently and in a methodologically sound manner, we trained an in-house team of interviewers

Hunsicker and Bethmann (

2023). This also enabled us to leverage SHARE staff’s in-depth knowledge of the study to inform the interview process and explore problematic theoretical and methodological aspects in more depth. These in-house QPI interviewers will also be available for upcoming revisions to the SHARE questionnaire.

This paper discusses the concept, implementation and results of revising the SHARE IT questionnaire module using QPIs. First, we introduce the QPI methodology and the SHARE IT module. We then describe the concept and practical implementation of QPIs within the project. Next, we present the results of the interview analyses and subsequent adaptations to the questionnaire module. Finally, we will share the lessons learned and consider the implications for SHARE and questionnaire development more broadly.

1.1. QPI Methodology

QPIs focus on formulating questions in a way that ensures they are understood and elicit valid responses

Buschle et al. (

2022);

Bethmann et al. (). The key feature of QPIs is the interviewer’s interaction with

respondents as co-experts. They engage in dialogical clarification of the manifest and implicit meanings of the survey questions in everyday language to achieve

intersubjective understanding.

This interaction is based on an integrated portfolio of principles and techniques for research communication, borrowed from qualitative interview methodologies such as problem-centred interviews

Witzel and Reiter (

2012). In particular, QPIs employ the concepts of

general and specific exploration to gather information, enabling interviewers to switch between active listening and active understanding depending on the progress of the interview.

Interviewers are also responsible for engaging participants in their role as co-experts, providing a thorough briefing at the beginning of the interview and continually reinforcing the relationship throughout. In this way, QPIs can explore the full range of (mis)understandings that respondents may experience, utilising their potential to improve the questionnaire. The interviewer’s role in QPIs is very involved and requires specific training, ideally in addition to prior training in qualitative interview methodology.

Section 2.1 will provide more information on the training procedures used in this project.

QPIs produce interview material that provides a rich contextualisation of the interviewee’s understanding of the survey questions, as well as the problem-centred interaction between interviewer and interviewee. This requires analytical approaches that can handle the complex nature of the data and make optimal use of the comprehensive material. While analytical methods that address the specific characteristics of QPIs are currently being developed e.g.

Buschle and Reiter (), approaches from qualitative interpretive methodology will be effective tools see e.g.

Flick (

2014);

Miller et al. (

2014);

Bethmann et al. ().

Although many of these approaches can be effectively employed to analyse QPIs (e.g. coding, qualitative content analysis), we had to use a more efficient approach for this project to fit within the strict SHARE timeline and to make the best use of our limited personnel resources. This will be described in the

Section 2.3.

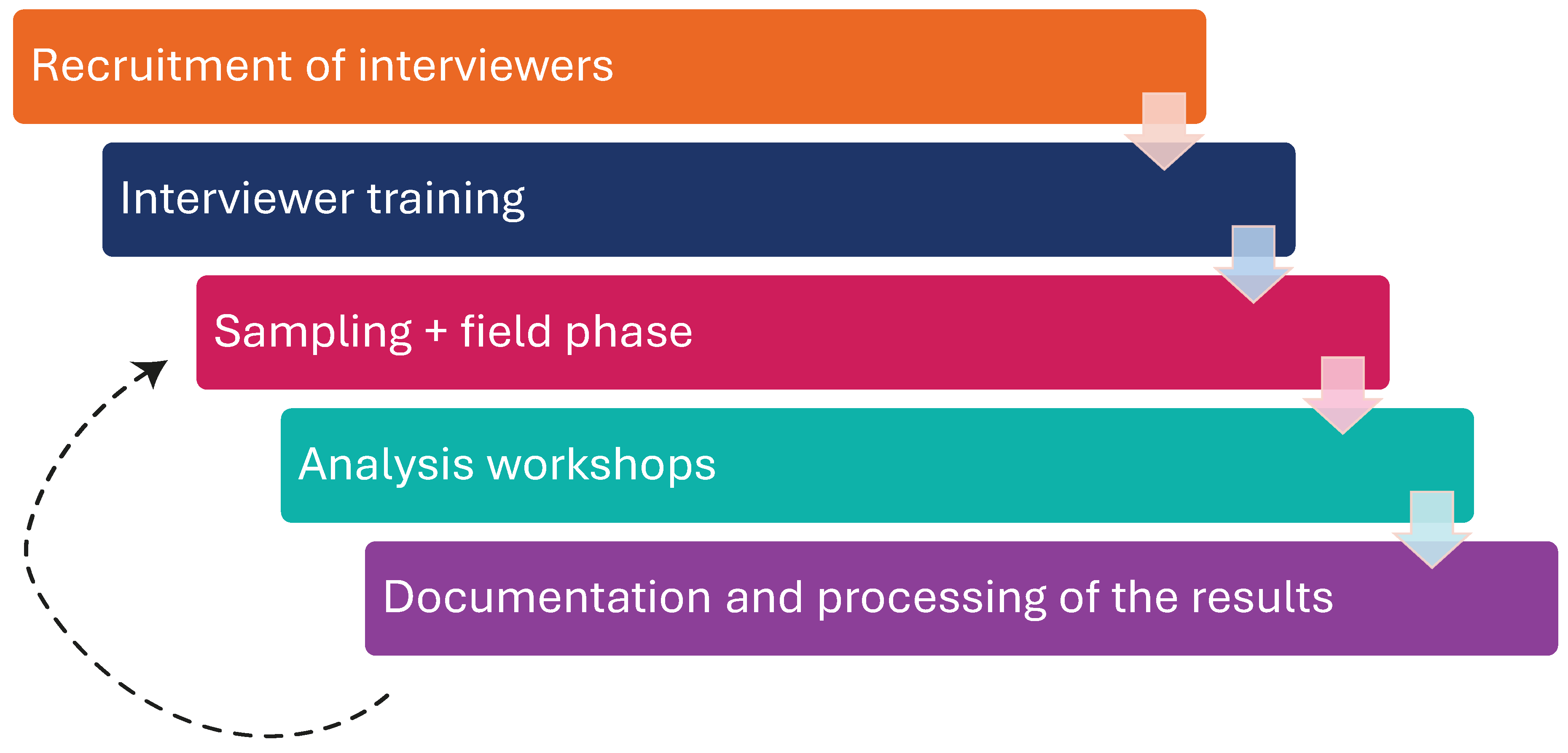

Implementing QPIs involves several steps, as shown in

Figure 1, including recruitment and sampling, data collection, analysis and questionnaire adjustment. This will be discussed further in the context of pretesting the revised IT module in

Section 2. Ideally, QPIs are used in an iterative process, incorporating findings from previous rounds into subsequent interviews. This ensures that adjustments improve the questionnaire and that issues which only emerge during analysis can be explored further through subsequent interaction with respondents.

1.2. Wave 10 IT-Module

The digital transformation of societies presents both opportunities and challenges, particularly for older adults. As the

European Commission (

2023) states: "Putting people at the centre of the digital transformation of our societies and economies is at the core of the EU vision for the Digital Decade. The EU and its Member States have agreed to ensure digital technologies enhance the well-being and quality of life of all Europeans, respect their rights and freedoms, and promote democracy and equality."

To inform such policy ambitions with reliable evidence, high-quality data on internet access, usage patterns, and digital proficiency across different population groups is essential. The SHARE IT module contributes to this effort by generating comprehensive insights into the digital engagement of Europe’s ageing population. The development of the Wave 10 IT module was guided by two key objectives:

First, the module aimed to close existing gaps in knowledge about internet use, digital literacy, and device access among older Europeans. By collecting detailed information across all three levels of the digital divide, the module provides a more differentiated understanding of how Europe’s ageing population engages with digital technologies.

Second, the module also serves a methodological purpose within SHARE. As the survey prepares for future transitions toward "SHARE 2.0" and the potential implementation of web-based data collection modes, understanding respondents’ technological capabilities becomes increasingly important for methodological planning.

To address these aims the original SHARE IT module was substantially expanded. The first version of the module was introduced in Wave 5 (2013) and consisted of four questions on topics such as computer use at work, self-assessed computer skills, and recent internet use. Given the rapid pace of technological development and increasing internet usage over the past decade

ITU (

2023), the scope for the Wave 10 update was broadened considerably. New questions were added to capture access to and use of internet-enabled devices, frequency of use, online activities, support patterns, proxy internet use, how long respondents have been using the internet, and—where relevant—reasons for limited or non-use.

2. Implementation

The implementation of Qualitative Pretest Interviews (QPIs) in SHARE was carefully designed to systematically evaluate and improve the questionnaire of the Wave 10 IT module. The German sub-study was selected as the testing ground for this methodological exploration, recognizing the importance of linguistic and cultural specificity in survey research.

The process began with recruiting interviewers from within the SHARE staff. They received comprehensive training to ensure a shared understanding of QPI methodology and standardized interview techniques. This training was essential for achieving the QPI objective of gaining deep, intersubjective understanding with interview participants.

Participants were recruited using a purposive approach. The aim was to archieve variation across gender, age, and retirement/working status, with a specific focus on individuals aged 50 and older. This approach was intended to capture a broad range of perspectives and experiences with internet use and digital technologies.

Data collection involved conducting in-depth interviews following the QPI methodology, with a strong focus on exploring respondent’ comprehension of the questionnaire items. All interviews were recorded and documented, producing a rich body of material for subsequent analysis. The analysis was carried out in collaborative workshops, where transcripts, recordings, and interviewer notes were examined. These sessions allowed for an iterative approach to understanding respondents’ interpretations, identifying potential misunderstandings, and exploring patterns of question comprehension.

Findings were then communicated to the Area Coordination (AC) team, SHARE’s scientific experts in charge of making decisions on questionnaire content, together with proposals for questionnaire adjustments. In this way, the QPI results directly fed into the refinement of the survey instrument, ensuring that the Wave 10 IT module was better aligned with respondents’ realities and improving the overall quality of SHARE data collection.

2.1. Interviewer Training

The first step was to prepare the team of interviewers. Three virtual training sessions were conducted to prepare them for fieldwork. The first two sessions, held on consecutive days, provided the methodological and practical foundation for conducting QPIs.

The initial session introduced the principles of qualitative interviewing with a particular focus on concepts central to QPIs such as intersubjective understanding and indexicality

Buschle et al. (

2022). Communication strategies for achieving intersubjective understanding through active listening and active understanding were presented and demonstrated in a live interview.

The second session focused on practice. Interviewers developed their own QPI interview plans and applied the techniques in mock interviews, receiving feedback from the trainers and peers.

A third training session was held shortly before the start of the fieldwork. This refresher session revisited the content from the first two training sessions and also addressed practical aspects of the project, such as participant recruitment procedures, the use of interview materials, etc.

With the training complete, interviewers were ready to move into the fieldwork phase.

2.2. Qualitative Fieldwork

In line with qualitative research practice, QPI methodology relies on purposive rather than random sampling. Instead of aiming for statistical representativeness, respondents are selected for characteristics relevant to the study objectives. For the evaluation of the Wave 10 IT module, participants were recruited through the family and social networks of the interviewers. The sample aimed to reflect variation in gender, age (50+), retirement/working status and levels of internet literacy. Recruiting individuals with little or no internet experience proved especially challenging. Following the field phase described in this report, part of the research team set out to recruit so-called ’true offline users’ for subsequent QPIs

zur Kammer et al. (

2025).

Table 1 summarizes the sample composition. In total, 17 German-speaking adults over the age of 50 participated in the QPIs.

To prevent personal relationships from influencing the interview process, interviewers were encouraged to rotate the participants they recruited. About half of the interviews were conducted between interviewers and respondents who did not know each other beforehand.

Most interviews were conducted in person at respondents’ homes, creating a familiar and informal setting. Two interviews took place virtually using the Internet meeting platform Zoom. Interview duration ranged from 20 to 120 minutes, with an average of 45 minutes per interview.

All interviews were audio-recorded and supplemented with interviewer postscripts. Transcripts were then created from the recordings. Together, transcripts, postscripts, and recordings provided the basis for the subsequent analysis workshops.

Table 2.

Interview Overview.

Table 2.

Interview Overview.

| |

Inter- |

Duration |

|

Prior relationship |

| No. |

viewer |

(in mins) |

Mode |

between I and IP |

| 001 |

001 |

42 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 002 |

002 |

45 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 003 |

003 |

55 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 004 |

003 |

40 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 005 |

004 |

65 |

Personal |

No |

| 006 |

005 |

64 |

Personal |

No |

| 007 |

006 |

18 |

Personal |

No |

| 008 |

006 |

16 |

Personal |

No |

| 009 |

006 |

29 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 010 |

006 |

32 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 011 |

004 |

120 |

Personal |

No |

| 012 |

007 |

45 |

Video |

No |

| 013 |

007 |

25 |

Video |

No |

| 014 |

007 |

43 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 015 |

001 |

37 |

Personal |

Yes |

| 016 |

008 |

67 |

Video |

No |

| 017 |

008 |

53 |

Video |

No |

2.3. Analysis Workshops

Following the fieldwork, the analysis phase was structured around a series of three workshops that brought together interviewers and QPI experts. The workshops adopted a pragmatic approach: while efficiency was necessary, the aim was to maintain a comprehensive understanding of respondents’ interpretations. The focus lay on identifying recurring interpretative themes, patterns of (mis)understanding, and potential sources of error across interviews, thereby generating insights into the validity of the questionnaire items.

A key principle to the workshop was the commitment to accurately represent the voices of the interview partners. Original comments, expressions, and examples provided by participants were carefully considered, ensuring that the analysis captured their lived experiences and maintained the authenticity of the qualitative data.

The analytical process was iterative, moving back and forth between interviewers’ impressions, collective interpretation of responses, and close examination of the original material. Relevant passages from transcripts and audio recordings were revisited to verify interpretations and refine the understanding of specific questionnaire items.

To ensure thorough documentation, these workshops were recorded. This recording process served as a valuable resource for reviewing discussions, preserving insights, and maintaining accuracy in subsequent analyses.

Due to time constraints, it was not possible to analyze every question of the IT module in detail. Priority was therefore given to those items that appeared to generate the greatest difficulties for respondents. This selective focus enabled the team to address the most critical issues efficiently, while still laying a foundation for further refinement in future pretesting phases.

3. Results

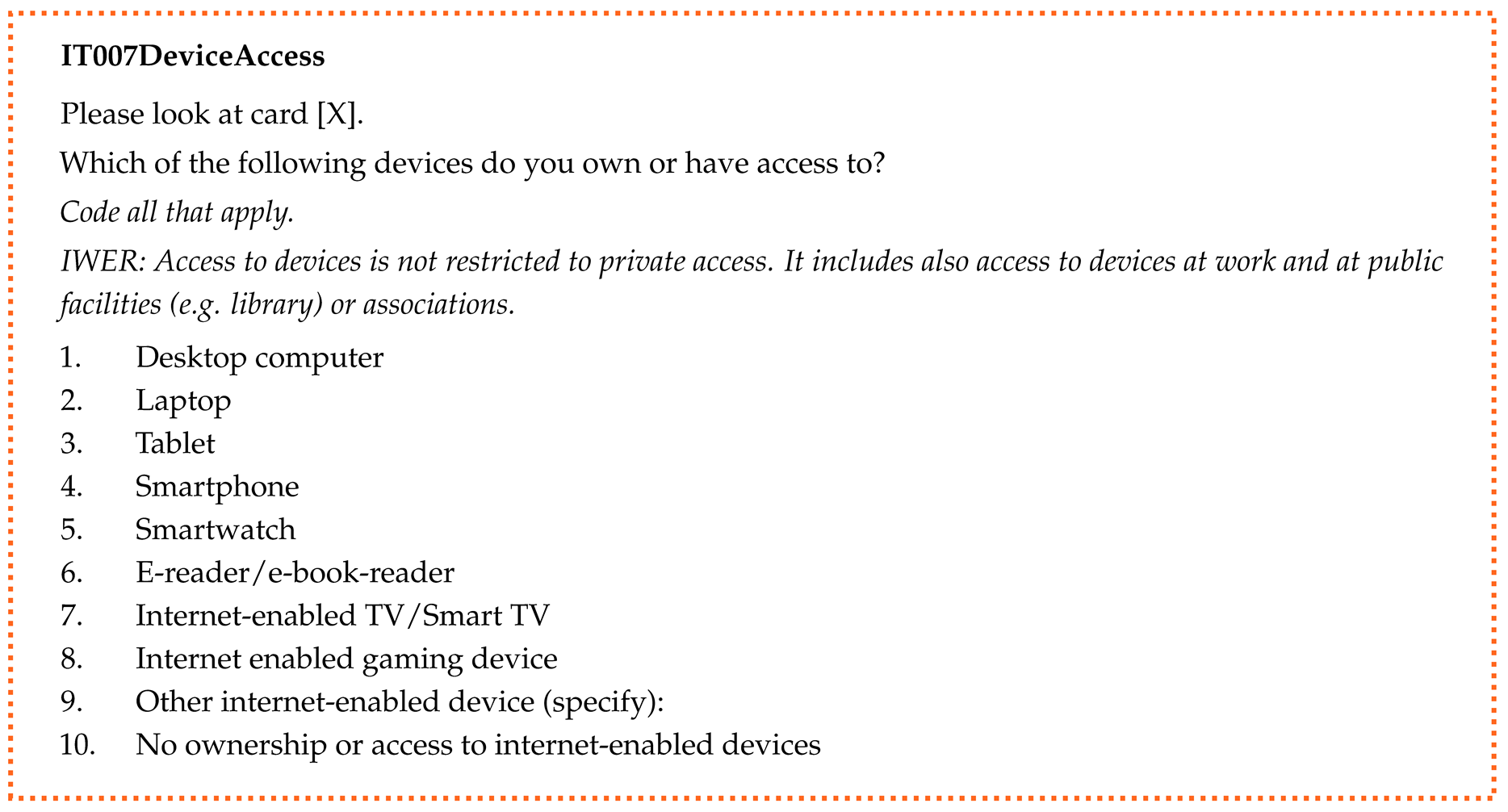

In this section, we will present the most prominent findings of our analysis. As previously mentioned, time and personnel restrictions forced us to prioritise the most salient items producing problems or irritations for the interview partners. These items—device access (IT007), online activities (IT010), help frequency (IT011), and years using the internet (IT014)—will therefore be discussed in more detail, including findings, discussion and suggestions for further development, as well as the changes implemented in the wave 10 SHARE questionnaire based on the QPI results. This will be followed by a summary of the results, which will also provide an overview of findings for items not analysed in detail due to time constraints.

3.1. Device Access

Description

The aim of this question is to assess the accessibility of different internet-enabled devices.

Findings

When analysing responses to item IT007, it was found that, although respondents generally understood the question, the nuances surrounding the distinction between "use" and "access" were not always clear. For instance, one respondent found it difficult to answer the question because they owned a smartphone but did not use its internet function.

Interpretations of "access to Internet-enabled devices" also varied: some participants extended the concept to include workplace devices, while others strictly limited it to those available at home. Without prompting from the interviewer, access to public devices (e.g., in libraries or cafés) was rarely mentioned.

In addition, some respondents had difficulty naming certain devices. The distinction between a "desktop computer," a "laptop," and a "tablet" was not always clear. Moreover, not all participants were familiar with terms such as "smartwatch" and "smart TV."

Discussion and Suggestions

The findings raised the question of whether the item should focus exclusively on access to devices, or whether it should also cover regular use. Clarifying this distinction would help reduce inconsistent interpretations. Workshop discussions also highlighted the need to provide interviewers with clearer instructions, including definitions and concrete examples of specific device types (e.g., distinguishing between smartphones and basic mobile phones, specifying the functions of smartwatches, or naming e-reader brands). In addition, explicitly defining the term "access" within the question could help respondents to answer more accurately and consistently.

Questionnaire Changes

For Wave 10, the question was rephrased to: "Which of these devices do you own or are at your disposal at your home?" This emphasised ownership and availability within the household, while excluding workplace or public devices.

The interviewer instructions were expanded to clarify the meaning of "at your disposal at home" and provide further guidance on device categories, such as distinguishing between smartphones and basic mobile phones, specifying that a smartwatch refers to a device with extended functionality such as biomonitoring or GPS, and giving concrete examples of e-readers like "Kindle" or "Tolino".

Furthermore, the category "internet-enabled gaming device" was removed due to persistent confusion, and the category "TV" was simplified as respondents found it difficult to distinguish between a "smart TV" and a TV without internet access.

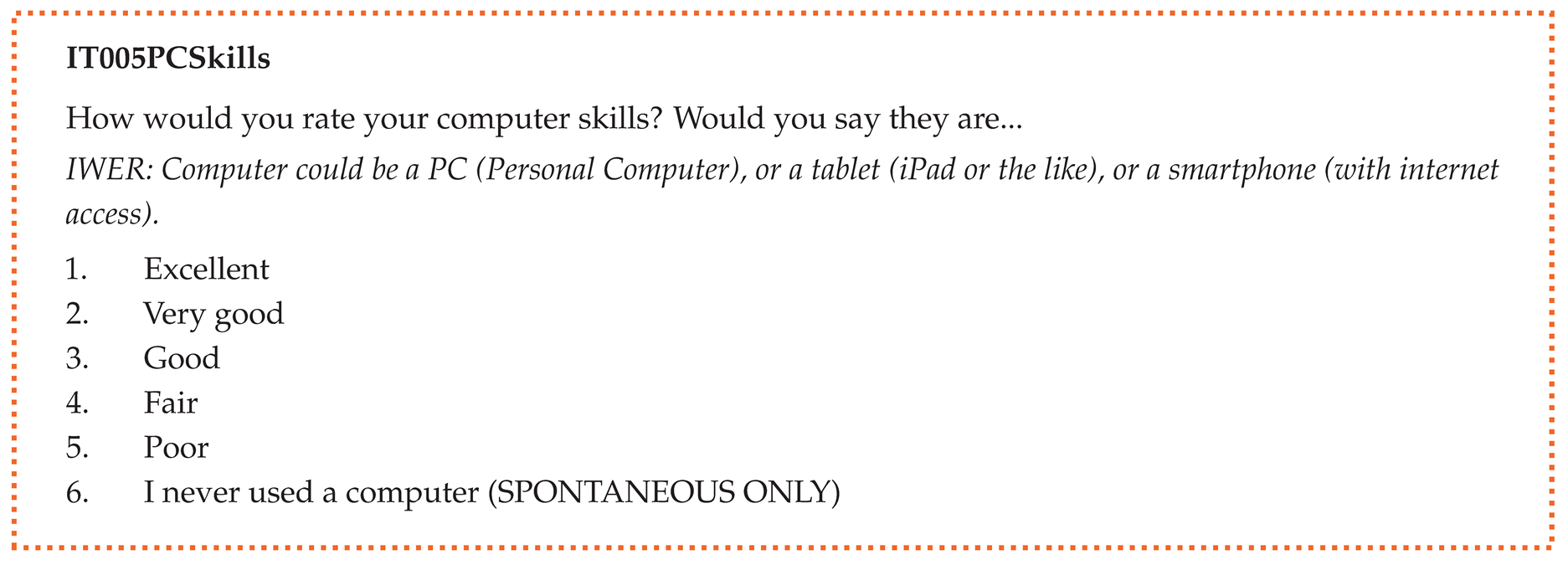

3.2. PC Skills

Description

This question aims to evaluate the work ability of senior workers and to assess whether retirement is brought about by their obsolescence.

Findings

Respondents frequently encountered difficulties when rating their computer skills. Many struggled to place themselves on the response scale, and their self-assessments often differed from the interviewers’ impressions. This suggests that they relied on different reference points.

Furthermore, the term "computer skills" was interpreted inconsistently: for some, it referred mainly to basic hardware-related abilities, whereas for others it encompassed broader digital competencies, such as programming. The response category "fair" (German: "mittelmäßig") was discussed as potentially socially desirable, with some respondents seemingly choosing it to avoid placing themselves at the extremes.

Discussion and Suggestions

The QPIs highlighted several challenges with the current wording. One option discussed was reframing the question to ask how confident, competent, or satisfied respondents feel with their digital abilities. This approach could provide a more intuitive basis for self-assessment.

Another suggestion was to place this item after the question on internet activities, so that respondents could draw on concrete examples from their own experience when evaluating their skills.

Finally, there was discussion about whether a more objective, competence-based measure (such as a digital literacy scale) might yield more comparable results across respondents than a purely subjective self-rating.

Questionnaire Changes

Despite the identified problems, the item was not revised for Wave 10. The primary reason was the need to ensure comparability with earlier SHARE data, as this question has been included in five previous waves. Changing the wording would compromise the ability to conduct longitudinal analyses. Nevertheless, the findings highlight a methodological dilemma: whether to retain an item that respondents interpret inconsistently, or to improve clarity at the expense of comparability.

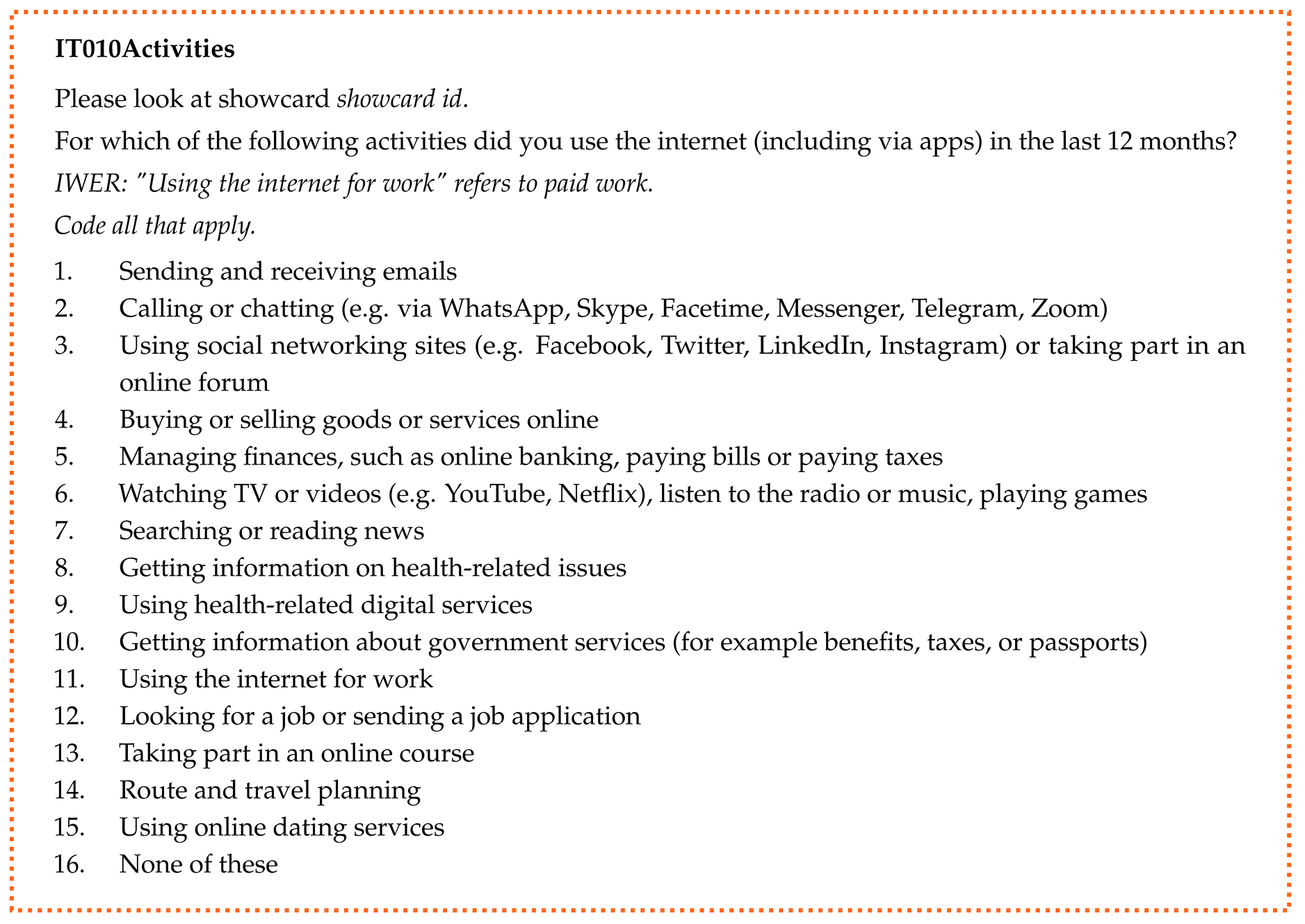

3.3. Online Activities

Description

The aim of this question is to identify various areas of daily life in which repondents use the internet, such as for communication, accessing information, entertainment and administrative services.

Findings

The question on internet activities presents a challenge due to its extensive list of response options, which may overwhelm respondents. Some respondents found some of these options difficult to understand or distinguish from one another.

Sending and receiving emails: No problems were identified.

Calling or chatting: The term "chat" was unfamiliar to some respondents. Additionally, examples provided caused confusion, e.g., one respondent associated "Zoom" with enlarging a photo rather than video calls.

Using social networking sites or taking part in an online forum: Respondents often struggled to distinguish between social networks and messenger services. The term "online forum" was often unfamiliar, and the examples provided were not universally understood. There was also uncertainty as to whether the question referred to active use, such as posting, or included passive activities such as reading posts and viewing photos.

Buying or selling goods or services online: No significant problems were reported. However, questions emerged as to whether booking services (without online payment) should be included. There was also uncertainty about including the exchange of goods or services (without monetary payment).

Managing finances, such as online banking, paying bills or paying taxes: No problems were identified.

Watching TV or videos, listen to the radio or music, playing games: Some confusion arose over the term "videos", with one respondent associating it with videotapes rather than streaming platforms. Similarly, some respondents interpreted "radio" as a physical device rather than an online activity.

Searching or reading news: In German, the word "Nachrichten" can mean either "news" or "messages", which can lead to ambiguity in interpretation. It is important to note that this issue is specific to the German version of the questionnaire.

Getting information on health-related issues: see 9.

Using health-related digital services: Respondents found it difficult to distinguish between these two answer options. The term "health-related digital services" in particular caused confusion, highlighting the need for clearer distinctions and the possible inclusion of examples.

Getting information about government services (for example benefits, taxes, or passports): No major problems were identified.

Using the internet for work: It was noted that an earlier question in the questionnaire (IT002PC Work) had already covered computer use at work. As it is difficult to distinguish between computer and internet use, this additional item may not be necessary.

Looking for a job or sending a job application: Some respondents were unsure as to whether volunteering and similar activities should be included.

Taking part in an online course: The broad nature of the term "online course" has led to uncertainty over what should be included in this category, with examples including YouTube tutorials, online lectures, and language learning apps.

Route and travel planning: While some respondents referred only to planning trips (e.g., by public transport), others included planning vacations in their answers.

Using online dating services: Not all respondents were familiar with the term "dating", but this issue might only be relevant for the German version.

Overall, the length of the list and the lack of clarity in certain categories created difficulties for many participants.

Discussion and Suggestions

The extensive list of options, as well as the difficulty of understanding and distinguishing between the categories highlight the need for refinement. Grouping response options under thematic subheadings was considered as a way to improve clarity and reduce respondent burden.

However, the respondents’ unfamiliarity with certain terms and the potential for confusion arising from the given examples, emphasise the importance of linguistic precision and cultural sensitivity. Future iterations of the questionnaire might benefit from testing alternative wordings and explanations to improve clarity and ensure a more accurate representation of respondents’ internet activities.

Questionnaire Changes

The question on internet activities was one of the most extensively revised, as several categories in the original version proved too broad or were often misunderstood. For instance, "chatting" was clarified as "writing and reading text messages in a messenger app or making internet-based calls, possibly with video (e.g., WhatsApp, Telegram)". Similarly, "online forum" was replaced with a more detailed description of social network use, explicitly including posting and reading content.

Examples were added across multiple categories to better reflect respondents’ everyday practices. These include online shopping (e.g., Amazon, eBay, online pharmacy, food and grocery delivery), managing finances (expanded to include mobile payments), and using digital government services (e.g., scheduling appointments, submitting forms). Health-related digital services were specified with examples such as video consultations and insurance apps. The wording of media-related activities was also adjusted: "Watching TV or videos, listening to the radio or music, playing games" was rephrased as "Watching movies or videos online (e.g., YouTube, Netflix); listening to online radio, audiobooks, podcasts, or music (e.g., Audible, Spotify)." This change aimed to avoid confusion between online and offline media use. Additional examples were also included for route and travel planning.

Furthermore, "taking part in an online course" was expanded to include the use of learning apps. New categories were also introduced to capture emerging practices, such as using apps for health and well-being (e.g., sleep tracking, mindfulness) and playing computer or mobile games as a distinct activity. At the same time, certain categories were removed. "Online dating" was omitted due to limited relevance and recurring comprehension issues, while "using the internet for work" was removed because it overlapped with Question IT004 ("Does your current job require using a computer?").

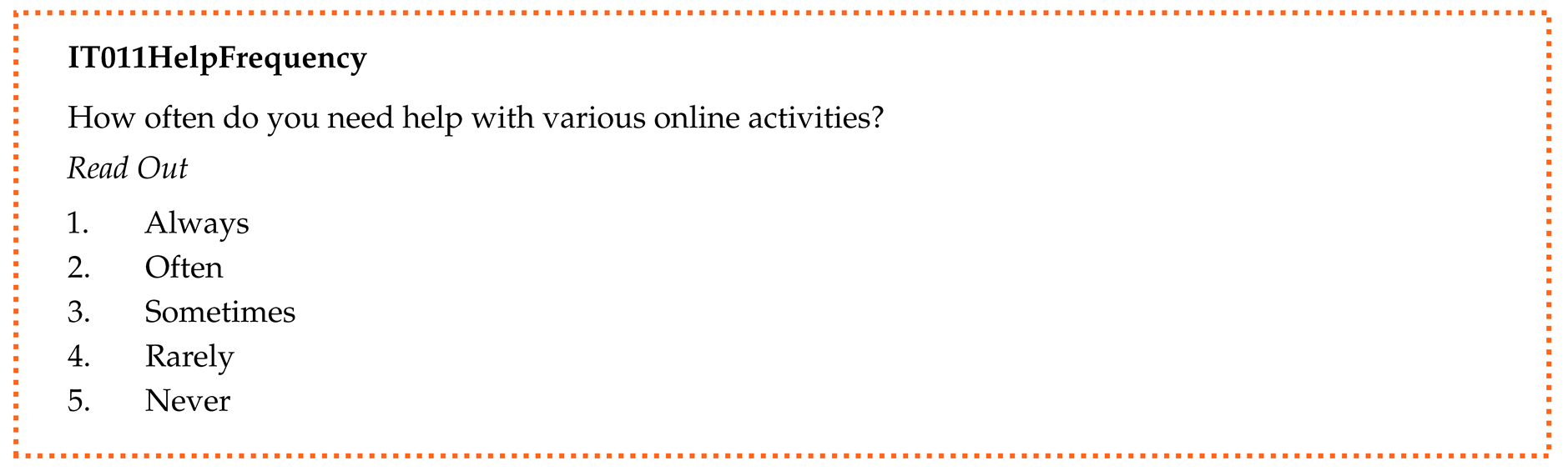

3.4. Help Frequency

Description

This question aims to assess the level of support needed for digital participation.

Findings

Respondents’ interpretations of the question on help-seeking for online activities varied considerably, exposing limitations in how the answer categories captured their experiences. Some respondents included situations in which they received support with general technical problems, such as setting up a device or resolving software issues, that were not strictly related to internet use. Several interview partners also found that the predefined response options did not accurately reflect the frequency or type of support they had actually received. This suggests a mismatch between the provided categories and the diversity of real-life help-seeking situations.

Discussion and Suggestions

Based on these findings, the possibility of broadening the question to include support with technical devices more generally, rather than just help related to online activities, was discussed. It was suggested that replacing the term "help" with "support" would reduce the risk of misunderstandings and more accurately reflect respondents’ experiences. To better capture the variety and frequency of support received, it was proposed that a revised set of answer categories be used, such as "very often", "often", "sometimes", "rarely", and "hardly ever or never".

Questionnaire Changes

Given the complexity of support dynamics and the shortcomings identified in the QPIs, it was decided that this question required further development before implementation. As a result, the item was omitted from the Wave 10 SHARE questionnaire. It has been flagged for refinement and is expected to undergo further development and testing for potential inclusion in future waves.

3.5. Years Using the Internet

Description

The aim of this question is to differentiate between "new internet users" and "experienced internet users".

Findings

Respondents often anchored their reported duration of internet use to personal life events, such as purchasing their first computer, writing a dissertation, or the birth of a child. This indicates that the question prompted reflections not only on technology, but also meaningful biographical associations.

Several participants expressed a desire for greater flexibility, stating that they would prefer to be able to specify the exact year they first went online rather than selecting from predefined categories.

Finally, some respondents seemed to equate general computer use with internet use, highlighting a possible source of confusion and suggesting that the distinction between the two may need to be made clearer in the question wording.

Discussion and Suggestions

In the subsequent analysis workshops, two versions were considered for further testing: one with a different gradation of years and another offering the option to specify a particular year. The aim of this experimentation is to find the most respondent-friendly approach, in line with their preferences for reporting internet usage duration.

In addition, the QPI team discussed the potential impact of changing the wording of the question to focus specifically on internet use. A suggested alternative question was considered: "Since when do you regularly use a device that is connected to the internet?" This phrasing aimed to shift the focus more explicitly towards internet-related activities.

Questionnaire Changes

The original question, ’For how many years have you been using the internet?’, was revised to ’Since when have you been using the internet?’ This was done because many respondents linked their first use of the internet to specific life events, such as buying their first computer or starting a new job. Allowing respondents to provide a specific year made the question easier to answer and more precise. To facilitate this, an entry field was added in which respondents could enter a number between 1989 and 2025.

3.6. Summary

Analysis of the QPIs revealed that the items tested in the IT module required different forms of treatment. Some items were adjusted based on respondent feedback, some were retained in their original form without changes, and a few were omitted from the Wave 10 questionnaire to allow more time for further development.

Several questions were adjusted in order to improve clarity and better reflect respondents’ experiences. The question on device access (IT007), for example, was refined through the addition of interviewer instructions, clarifying the concept of "access", and by revising answer options, ensuring more precise reporting. In addition, the answer categories for IT011 ("Which of the following devices do you typically use to access the internet?") were aligned with the devices listed in IT007. The question on online activities underwent substantial revision: categories were clarified, terms rephrased, and examples added to avoid misunderstandings and align more closely with everyday practices. Similarly, the question on years using the internet (IT014) was reformulated to allow respondents to provide a specific year rather than an approximate duration. This reflects the way many participants anchored their recollections in specific life events. Furthermore, the two questions addressing reasons for not using the internet (more often) were merged into a single item (IT012) to streamline the response process.

Other questions were not adjusted, either because they performed sufficiently well or because maintaining comparability across waves was prioritised. For instance, the PC skills question (IT003) remained unchanged, even though some respondents found it difficult to assess their own abilities, in order to maintain continuity with previous waves. The questions on computer use at work (IT001 and IT002) did not reveal major problems during the QPIs and were therefore retained. The same applied to the items on whether respondents had used the internet in the past seven days (IT008) and on frequency of internet use (IT009). Apart from IT009, all of these questions had been part of the previous questionnaire, and changes would have compromised comparability across waves.

A smaller number of items were omitted entirely, as their complexity required more fundamental development before being fielded in the main questionnaire. The most prominent example was of this was the help frequency item. Respondents interpreted “help” in many different ways, and the response options did not capture the diversity or frequency of support dynamics in practice. It was therefore decided to omit the question for Wave 10 and dedicate additional time to refining it for potential inclusion in future waves. Consequently, the item on who usually provides help was also omitted. The same applied to questions, which asked whether respondents requested others to use the internet on their behalf and, if so, from whom. Within the online activities item, specific categories such as online dating or using the internet for work were also removed, as they either caused recurring comprehension problems or overlapped with other existing questions.

In summary, the QPIs provided a nuanced picture of item functioning, which directly informed questionnaire development. These results not only guided the concrete adjustments made for Wave 10 and also highlighted broader methodological challenges, such as the trade-off between clarity and longitudinal comparability—a central issue in panel survey design. The following conclusion chapter reflects on these insights and discusses their implications for the further methodological development of the QPIs as well as future pretesting practices in SHARE.

4. Conclusion

Two main aims were pursued by conducting QPIs to evaluate the revision of the SHARE Wave 10 IT questionnaire module. The first was to inform the evaluation process by feedback from respondents themselves in order to make revisions to the questionnaire improving the validity of the answers collected in the main survey wave. Secondly, the QPI approach was to be implemented for the first time in a complex, large-scale survey and should be conducted by specifically trained in-house interviewers to test and further develop the approach itself.

Regarding the first objective, this report demonstrates that QPIs enabled issues with several items to be identified and addressed. The material collected during the in-depth interviews provided a rich foundation for further analysis during the workshops, informing discussions between interviewers and the questionnaire development team and providing targeted respondent feedback. Based on these discussions, several decisions regarding adaptations to the questionnaire were developed, proposed to the Area Coordination team, and subsequently implemented.

With regard to the second aim, the resource-intensive QPI approach was successfully integrated into SHARE’s strict processes and schedule. During this process, a training programme for a team of QPI interviewers recruited from in-house staff was developed and implemented for the first time, as well as an efficient, collaborative approach for analysing QPIs in the form of the analysis workshops.

Limitations

Although the IT questionnaire module was successfully revised, adapting the QPI methodology to SHARE also highlighted several key challenges and limitations, providing valuable insights for future development and implementation.

The sample composition revealed a significant challenge. Despite efforts to recruit a diverse group of participants, the sample did not include any "true" offline users, a demographic that is notoriously difficult to locate. This absence potentially limits the comprehensiveness of insights into digital exclusion and internet non-use (see

zur Kammer et al. (

2025) for more details on the efforts to recruit "offliners" in the project).

An additional methodological nuance emerged from the relationship dynamics between interviewers and participants. While some pre-existing relationships were not inherently negative and could potentially facilitate more precise questioning, they nonetheless introduced a potential source of bias that could influence interview dynamics and responses.

Cross-Country Perspective

Perhaps the most significant issue is that the study’s scope was constrained both geographically and linguistically, with the focus placed exclusively on the German context. This limits the generalisability of the findings to other cultural and linguistic environments—a particularly pertinent issue for SHARE, given that it involves 28 participating countries and a questionnaire in 39 different language versions. The current project is therefore just a first step, and QPIs need to be further developed if they are to be properly implemented in cross-country studies. See

Willis and Miller (

2011) for a similar discussion in Cognitive Interviewing.

Furthermore, SHARE’s international nature presented communication challenges, as the Area Coordination team—who have the most comprehensive understanding of the questionnaire’s scientific content and objectives—were not fully integrated into the first stages of the QPI experiment due to language barriers, since they are based in Italy and the interviews were conducted in German.

In-House Interviewers

There are certain advantages to recruiting interviewers from within a survey project’s staff. They have more detailed knowledge of the study than third-party interviewers, and once trained, they can be used for multiple questionnaire revisions. It should be noted, though, that interviewers, who were SHARE staff members, might have faced conflicting roles due to their involvement in questionnaire development. This way their insider perspective, while potentially beneficial, also posed the risk to introduce unintended biases into the interview process. On the other hand, this perspective is particularly useful, given that QPIs usually assume that the researcher conducting the study is also conducting the QPI. This ensures that the researcher/interviewer’s research knowledge and the interview partner’s everyday knowledge are aligned, producing insights for improving the questionnaire once intersubjective understanding is reached.

In more complex surveys, communication is more indirect. For example, in the case of SHARE, the subject matter experts would be the Area Coordination team, who work with the Questionnaire Development (QD) team, which is responsible for turning questions into something that can be surveyed through the questionnaire. QPI interviewers were QD and other SHARE staff members. This created a more indirect link between research knowledge and the perspective of the interview partners than in smaller studies with less division of labour. Nevertheless, this approach may still be preferable to employing a third party to conduct the interviews.

A common drawback is that survey staff are often not trained in qualitative interviewing methodology. This increases the need for proper training and practice, as conducting qualitative interviews—including QPIs—greatly benefits from experience. Therefore, when hiring new staff, it might be advisable to also consider candidates with a background in qualitative or mixed-methods research.

These challenges underscore the complexity of implementing qualitative pretesting methods in large-scale, international survey research. They highlight the need for careful methodological design, participant selection, interviewer training, and ongoing refinement of interview techniques, particularly with a focus on cross-lingual/cultural comparability.

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w3.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w4.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.900, 10.6103/SHARE. w6.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.DBS.100, 10.6103/SHARE.w7.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w8.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w8ca.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w9.900, 10.6103/SHARE.w9ca900, 10.6103/SHARE.HCAP1.100); see

Börsch-Supan et al. (

2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission, DG RTD through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982, DASISH: GA N°283646) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SHARE-COHESION: GA N°870628, SERISS: GA N°654221, SSHOC: GA N°823782, SHARE-COVID19: GA N°101015924) and by DG Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion through VS 2015/0195, VS 2016/0135, VS 2018/0285, VS 2019/0332, VS 2020/0313, SHARE-EUCOV: GA N°101052589 and EUCOVII: GA N°101102412. Additional funding from the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (01UW1301, 01UW1801, 01UW2202), the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, BSR12-04, R01_AG052527-02, R01_AG056329-02, R01_AG063944, HHSN271201300071C, RAG052527A) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see

https://share-eric.eu/).

References

- Bethmann, Arne, Christina Buschle, and Herwig Reiter. 2019. Kognitiv oder qualitativ?: Pretest-Interviews in der Fragebogenentwicklung. In Qualitätssicherung sozialwissenschaftlicher Erhebungsinstrumente. Edited by N. Menold and T. Wolbring. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 159–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethmann, Arne, Christina Buschle, and Herwig Reiter. Qualitative pretest interviews. In Encyclopedia of social measurement (Second Edition). Edited by S. Sinharay. Elsevier.

- Biemer, Paul P., and Lars Lyberg. 2003. Introduction to survey quality

. In Wiley series in survey methodology. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan, Axel, Martina Brandt, Christian Hunkler, Thorsten Kneip, Julie Korbmacher, Frederic Malter, Barbara Schaan, Stephanie Stuck, and Sabrina Zuber. 2013. Data Resource Profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology 42, 4: 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradburn, Norman M., Seymour Sudman, and Brian Wansink. 2004. Asking questions: the definitive guide to questionnaire design, for market research, political polls, and social and health questionnaires, Rev. ed ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Buschle, Christina, and Herwig Reiter. Analysing qualitative pretest interviews using qualitative content analysis. In Handbook of Qualitative Content Analysis. Edited by M. Schreier and N. Weydmann. Edward Elgar.

- Buschle, Christina, Herwig Reiter, and Arne Bethmann. 2022, April. The qualitative pretest interview for questionnaire development: outline of programme and practice. Quality & Quantity 56(2), 823–842. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2023. European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles for the Digital Decade. Official Journal of the European Union C 23/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/ ?uri=CELEX:32023C0123(01).

- Flick, Uwe. 2014. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, R. M., and L. Lyberg. 2010. Total Survey Error: Past, Present, and Future. Public Opinion Quarterly 74, 5: 849–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, Robert M., Floyd J. Fowler, Mick P. Couper, James M. Lepkowski, Eleanor Singer, and Roger Tourangeau. 2009. Survey methodology (2nd ed ed.). Wiley series in survey methodology. Hoboken, N.J:Wiley.

- Hunsicker, Charlotte, and Arne Bethmann. 2023. SHARE Wave 10 - An Initial Report of Qualitative Pretest Interviews on the Wave 10 IT Module. Internal report, SHARE, November. [Google Scholar]

- ITU. 2023. Facts and Figure 2023. Measuring digital development. Technical report, International Telecommunication Union, Geneva. https://www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-indict_mdd-2023-1/.

- Lenzner, Timo, Patricia Hadler, and Cornelia Neuert. 2024. Cognitive Pretesting. Technical report, GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.15465/GESIS-SG_EN_049.

- Lyberg, Lars E., and Herbert F. Weisberg. 2016. Total Survey Error: A Paradigm for Survey Methodology. In The SAGE Handbook of Survey Methodology. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Cognitive Interviewing Methodology, 2014, 1 ed. Miller, Kristen, Stephanie Willson, Valerie Chepp, and José-Luis Padilla, eds. Wiley, July. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Gordon B. 2005. Cognitive Interviewing. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States of America: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Gordon B. 2015. Analysis of the Cognitive Interview in Questionnaire Design. S.l.: Oxford University Press.

- Willis, Gordon B. 2016. Questionnaire Pretesting. In The SAGE Handbook of Survey Methodology. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Gordon B., and Kristen Miller. 2011. Cross-Cultural Cognitive Interviewing: Seeking Comparability and Enhancing Understanding. Field Methods 23, 4: 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, Andreas, and Herwig Reiter. 2012. The Problem-Centred Interview: Principles and Practice. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zur Kammer, Kenneth, Annika Hudelmayer, and Johanna Schütz. 2025. „Ich kann alles Mögliche, aber ins Internet kann ich nicht — Doch in Google komme ich rein“: Erkenntnisse aus Qualitativen Pretest Interviews mit Offliner:innen zum IT-Modul in SHARE und Implikationen für die Umfrageforschung. BZPD Working Paper Series; 10-2025. [CrossRef]

- zur Kammer, Kenneth, Johanna Schütz, Annika Hudelmayer, Charlotte Hunsicker, and Arne Bethmann. 2025. Measuring computer skills of older people in share. evaluation of the item it003_pc_skills (it module) using qualitative pretest interviews. Share working paper series 98-2025, SHARE-ERIC.

| 1 |

The authors would like to thank Claudia Weileder, Magdalena Hecher, Imke Herold, Silvia Strutinsky and Franziska Schäfer for their invaluable contributions to the project.

|

|

|

|

For further details on the results of the QPIs on this question and reflections on the measurement of computer skills among older adults in longitudinal surveys, see zur Kammer et al. ( 2025). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).