1. Introduction

Globally, soil covers about 29% of Earth's land surface and serves as a fundamental resource for sustaining life and human activities. Approximately 38% of this land area is dedicated to agriculture, encompassing croplands, pastures, and orchards. Beyond its role in supporting plant growth, soil is integral to the broader ecosystem, contributing to water retention, nutrient cycling, and the sustenance of diverse microbial life that sustains soil health and productivity [

1]. As the global population is projected to surpass 9 billion by mid-century, optimizing agricultural land use has become increasingly urgent. Sustainable soil management practices will be essential not only to meet the rising food demand but also to safeguard the environmental integrity of our planet.

Historically, farmers have developed a wide range of soil cultivation techniques, each affecting soil health, crop yields, and environmental outcomes in unique ways. Traditional deep plowing, for instance, has been used to aerate the soil and incorporate organic residues. While this method can provide immediate benefits in terms of soil aeration and nutrient mixing, it also leads to long-term challenges such as increased soil erosion and a reduction in soil organic matter [

2]. On the other hand, modern practices like no-till and minimal tillage farming focus on preserving soil structure and reducing mechanical disruption. These approaches aim to maintain or even enhance soil fertility over time by increasing biodiversity, improving water retention, and promoting better microbial health [

3]. Despite requiring careful management of weeds and soil nutrients, no-till methods are widely considered an effective means of mitigating soil degradation, enhancing long-term agricultural productivity, and reducing the carbon footprint of farming.

Soil management techniques like terracing and contour farming have long been integral to agriculture in mountainous and sloped regions. Terracing, an ancient practice, involves the creation of flat, stepped plots on slopes to reduce water runoff, minimize erosion, and enhance water retention. This technique allows farmers to transform steep terrains into viable agricultural lands [

4]. Similarly, contour farming, which entails planting along the natural contours of the land, helps distribute water more evenly and reduces the speed of water runoff, which in turn prevents soil erosion. These methods have demonstrated their effectiveness in diverse agricultural landscapes, from the Andes in South America to Southeast Asia, where they have been crucial for enhancing crop productivity while conserving soil resources.

In flatter or gently rolling plains, orchards thrive due to deeper soils and easier access for farm equipment. These conditions make it easier to implement practices such as uniform fertilizer and pesticide application, as well as the use of modern irrigation systems. Maximizing orchard performance in such settings requires choosing tree varieties suited to local conditions and employing cutting-edge agricultural tools like drones and soil sensors for real-time monitoring. Integrated pest management (IPM) also plays an important role in promoting tree health and optimizing yields, ensuring that orchards remain productive over time.

However, orchards located in hilly or mountainous regions face distinct challenges due to uneven topography and varying microclimates. To address these challenges, soil-shaping techniques such as terracing and soil undulation are especially valuable. Soil undulation involves creating subtle rises and depressions across the landscape to optimize water retention, improve soil infiltration, and reduce water runoff [

5]. This practice not only enhances local moisture retention, which can significantly reduce the need for irrigation, but also improves aeration and reduces the risk of waterlogging—two crucial factors for maintaining healthy tree roots. Additionally, the gentle variations in the land's surface help buffer temperature fluctuations, creating a more stable environment for tree growth. These characteristics make soil undulation an ideal method for enhancing orchard productivity in areas with challenging topography.

The benefits of soil undulation for orchard systems extend beyond water management. By improving moisture retention and facilitating better drainage, this technique helps prevent erosion and ensures that the soil remains fertile over time. Soil undulation also reduces the need for irrigation, which not only conserves water but also lowers operational costs for farmers. Furthermore, the enhanced drainage capacity helps mitigate the risk of root diseases that could otherwise harm tree health. As a result, orchards that implement soil undulation can achieve higher yields and a more sustainable approach to farming [

6].

Soil composition is another critical factor that influences orchard success. Loess soils, known for their light texture and mineral content, provide excellent aeration and moisture retention, making them ideal for root growth [

6]. Clay soils, on the other hand, can retain nutrients but often suffer from poor drainage, which requires careful management to avoid waterlogging. Sandy soils drain quickly but tend to hold less moisture and nutrients, meaning orchards in such areas need targeted irrigation and fertilization strategies to maintain healthy tree growth.

Regions like Tuscany in Italy exemplify the successful integration of terracing and soil undulation in orchard management. Despite challenging climates and sloped terrains, these techniques have helped improve water capture, reduce soil erosion, and ensure reliable fruit production. Similarly, mountainous orchard regions in Greece and Spain have long used these methods to adapt agricultural practices to steep and uneven landscapes. In California, U.S., orchards have adopted a combination of modern soil-shaping techniques and high-efficiency irrigation technologies to optimize productivity and environmental sustainability [

7].

The impacts of climate change have further complicated orchard management, as rising temperature variability, erratic precipitation, and extreme weather events threaten soil quality and tree health. In response, conservation techniques like soil undulation, terracing, and contour farming are becoming even more vital. These practices help mitigate the adverse effects of climate change by maintaining soil moisture, preventing erosion, and preserving nutrient balance, which collectively contribute to the resilience of orchards under shifting climatic conditions [

8].

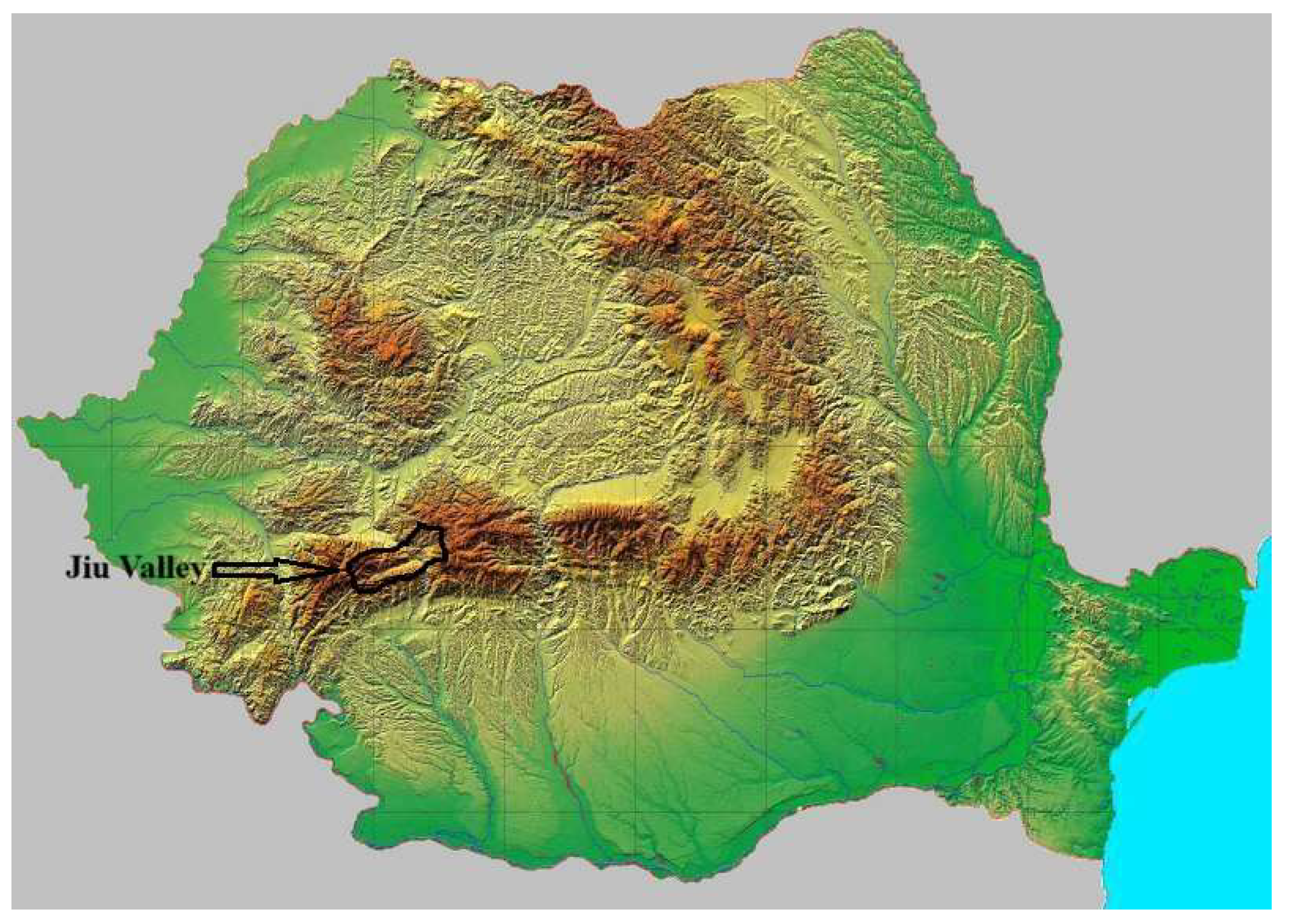

The Jiu Valley presented in

Figure 1, situated in southwestern Romania provides an excellent case for the application of sustainable orchard practices. This region, with its hilly terrain and continental climate, has long been dominated by industrial activity but is now shifting toward more sustainable agricultural practices.

The implementation of soil undulation, along with terracing and contour farming, could mitigate erosion, enhance water retention, and stabilize soil fertility, particularly during dry spells. Precision farming tools like GPS mapping (

Figure 2), soil moisture sensors, and drones could enable more targeted interventions tailored to local soil characteristics, further improving water efficiency and reducing the use of inputs.

In addition to technical practices, community involvement and education are crucial for the successful adoption of sustainable soil management methods. Farmer cooperatives, workshops, and field demonstrations can help disseminate knowledge and encourage the implementation of practices like soil undulation. Public-private partnerships, which include government subsidies, tax incentives, and private investments in agricultural technologies, can also facilitate the large-scale adoption of these practices. Furthermore, promoting agro-tourism and establishing a unique brand identity for sustainably grown orchard products can generate new economic opportunities, benefiting both local communities and the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to analyze the impact of soil undulation in orchard plantations on soil stability, resource use efficiency, and the reduction of the carbon footprint. The soil carbon footprint is an increasingly studied component within the context of sustainable agriculture, representing the total amount of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, emitted or absorbed as a result of land management practices [

9]. Soils can act either as sources of emissions or as carbon reservoirs, depending on human interventions.

Agricultural practices that conserve organic matter and limit erosion contribute to the sequestration of atmospheric carbon in soil profiles over time [

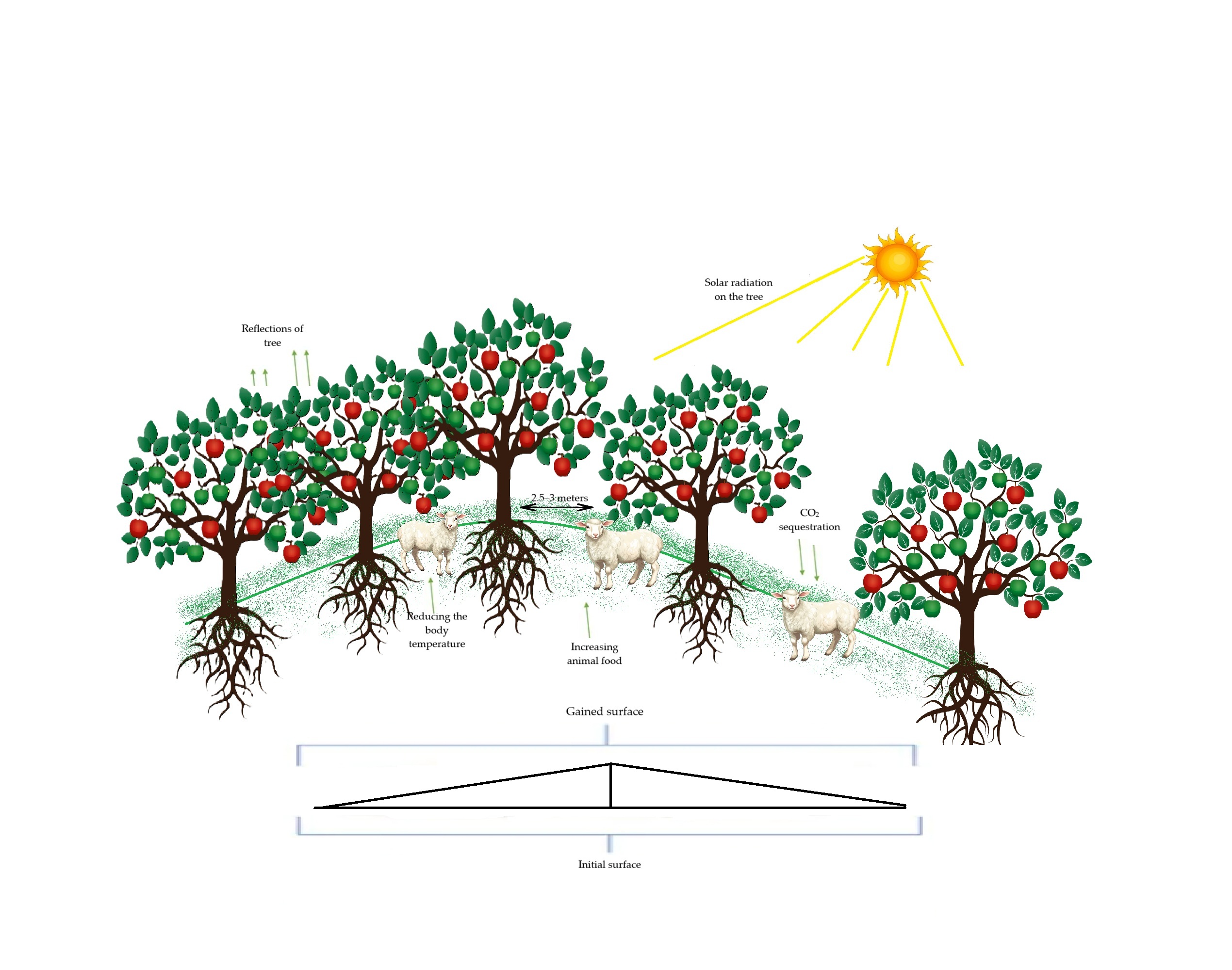

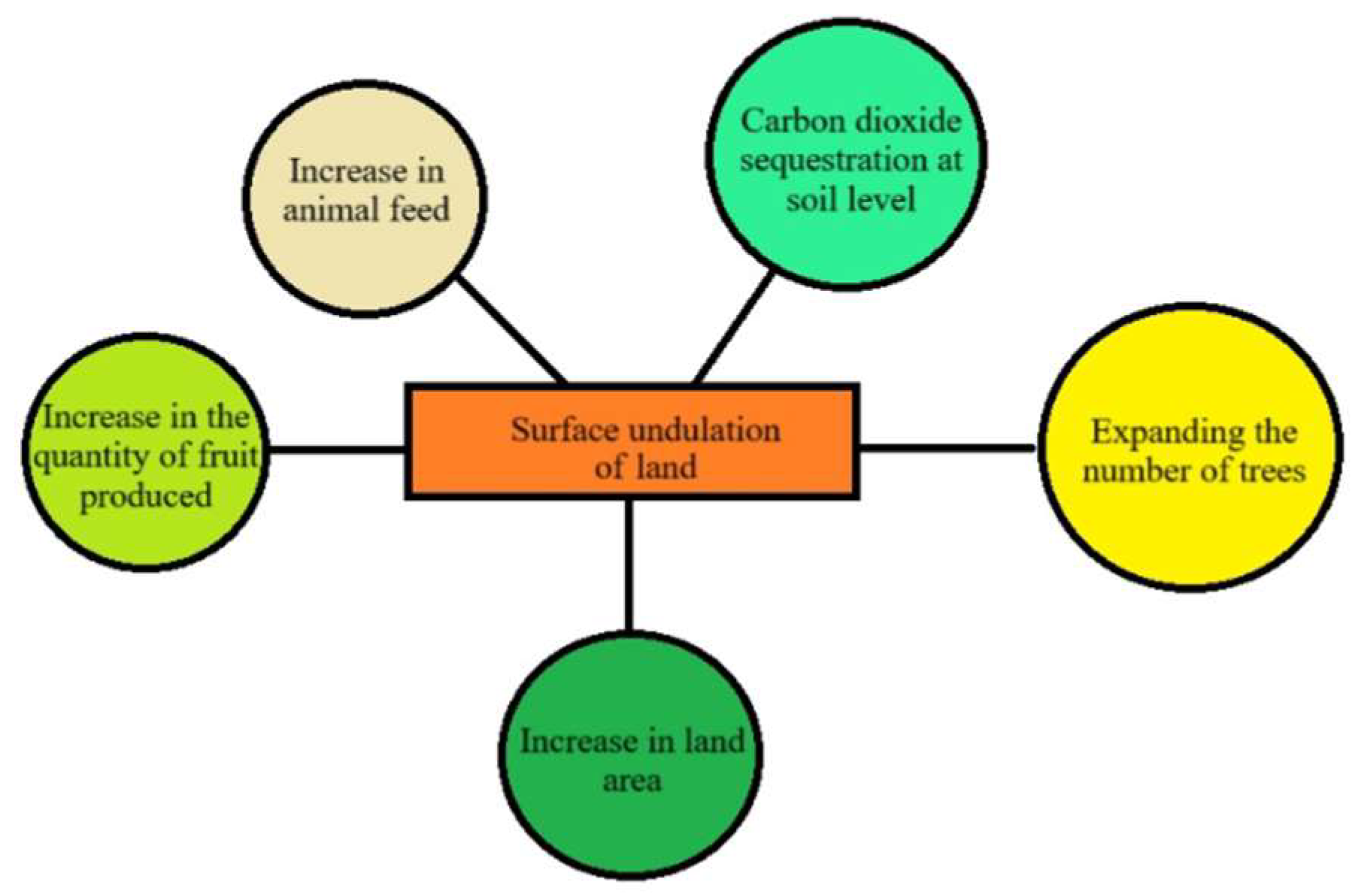

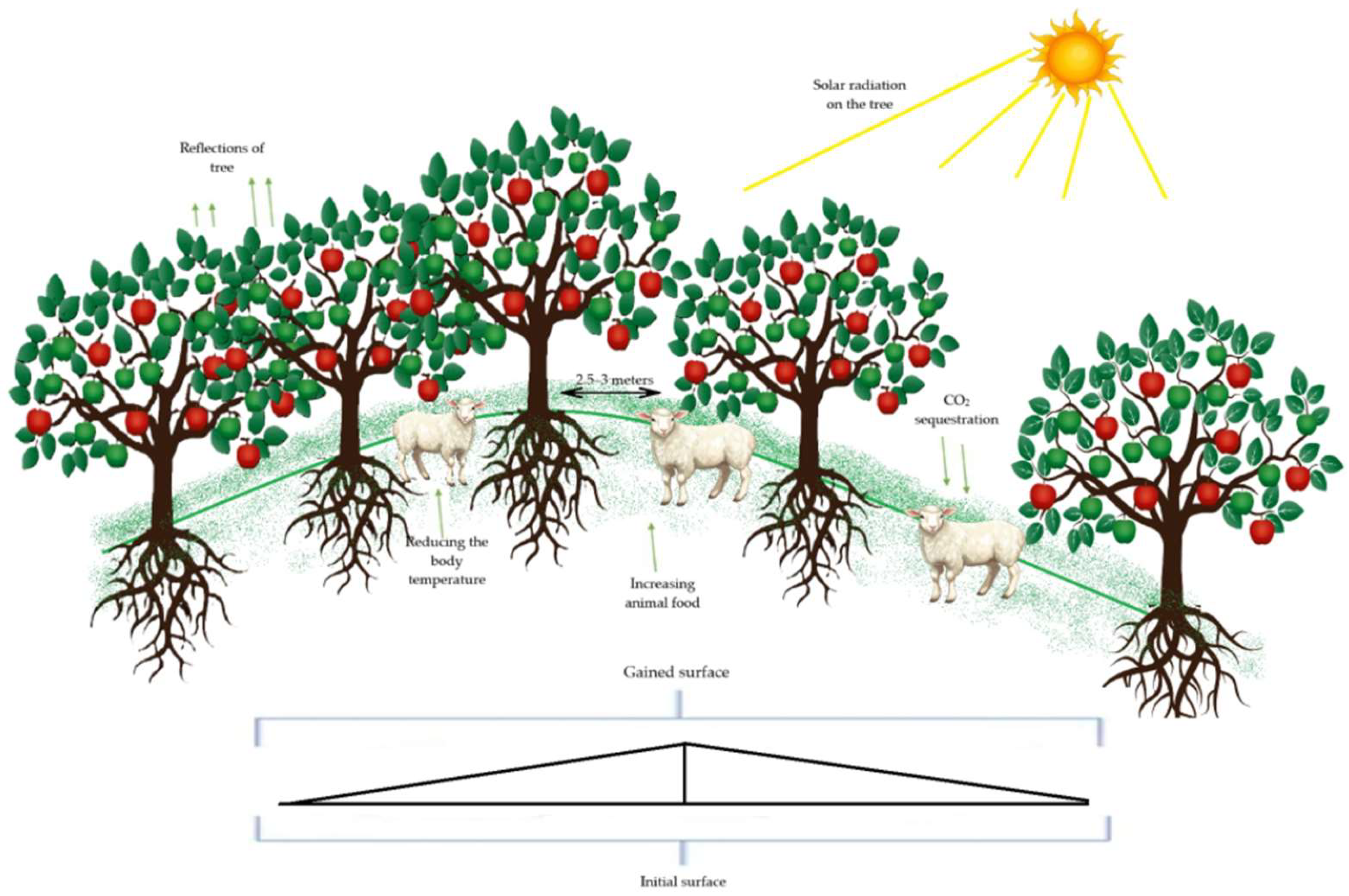

10]. Therefore, introducing controlled soil undulations in orchard plantations has the potential to reduce organic matter loss and stimulate its accumulation, thus contributing to the reduction of the carbon footprint. Some of the most important effects of undulation are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The images shows a sustainable agricultural and ecological system, highlighting the benefits of planting fruit trees in a wavy system. The trees in the image play an essential role in regulating the ambient temperature, reducing the heat generated by solar radiation through their reflection, which contributes to the creation of a cooler microclimate. In addition, these trees help to sequester carbon dioxide (CO2), a process by which carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is captured and stored in the soil, thus having a positive impact on climate change and contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gases.

Regarding fauna, trees can grow food for animals, provide fruit, but also a more favorable environment, because through the shade generated by their branches, they help to reduce the body temperature of animals, thus protecting them from heat waves or extreme heat conditions.

Also, due to a spacing between trees of 2.5 to 3 meters, the optimal development of each tree is ensured, without creating excessive competition for soil resources. This spacing contributes to a healthy development of the trees and a more efficient use of the land.

Last but not least, the area gained by implementing this planting system, compared to the initial area, is larger. This suggests that by planting trees and creating a sustainable ecosystem, a more valuable and productive land can be obtained, with ecological and economic benefits.

The Jiu Valley region is characterized by a moderate continental climate with mountain influences, with average annual temperatures ranging between 8 and 9°C. Precipitation levels are relatively abundant, fluctuating between 700 and 1,200 mm annually, as is presented in

Table 1 [

11], and the alternation between wet and dry periods favors soil undulations, especially in areas with clayey textures prone to contraction and cracking.

This dynamic negatively affects the root development of trees through mechanical displacements and limited access to resources during periods of hydric stress. Furthermore, the variation in temperature and moisture levels can lead to significant fluctuations in soil moisture, exacerbating the effects of drought and excessive water retention. As a result, these conditions create challenges for agricultural productivity, particularly for fruit-bearing trees that are highly sensitive to soil moisture changes.

Additionally, soil erosion may become a concern due to the alternation of wet and dry periods, further destabilizing the soil structure. Over time, the cumulative effects of these factors can lead to a decrease in soil fertility, ultimately impacting long-term crop yields in the region.

It is essential to mention that the Jiu Valley is a region profoundly impacted by mining activities, where mine closures have left behind vast degraded lands, including waste dumps. These areas are characterized by unstable soil, poor in organic matter, acidic, and with deficient structure [

12]. Transforming these lands into an

agro-orchard system through undulation and reconversion can contribute not only to ecological rehabilitation but also to the economic diversification of the region in accordance with the principles of sustainable development [

13]. The integration of orchard trees on these surfaces can stabilize the soil, improve air and water quality, and create functional microecosystems in areas previously biologically sterile.

The configuration of plantations must be designed in accordance with the specific relief of the area. In apple or plum plantations, it is recommended that the spacing between trees be 2.5–3 meters and between rows 4–4.5 meters [

14], to allow normal crown development and mechanized work. On sloped terrain, rows should be arranged along contour lines, an effective practice to prevent erosion [

15,

16]. Slopes between 5% and 12% are ideal for such plantations, offering a balance between drainage and stability.

Therefore, applying the undulation technique on mining lands or waste dumps represents a strategic agroecological intervention with the potential for functional and productive restoration of a region marked by industrial decline.

This study seeks to establish whether this approach is feasible agronomically and ecologically, opening the perspective for productive use of lands otherwise considered unusable.

When measuring a distance on land, if the surface is perfectly flat, the distance measured on the horizontal plane coincides with the actual distance on the terrain. However, in the case of undulating terrain with slopes and irregularities, the real distance follows the curves and inclinations of the land, becoming longer than its horizontal projection. This phenomenon is crucial for accurate topographical measurements, cadastral work, and precise evaluation of land surfaces.

To quantify the difference between the planar distance and the real distance, we applied the Pythagorean theorem to a simplified model that represents the segment of land as the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

The horizontal leg of this triangle corresponds to the distance measured on the plane, while the vertical leg represents the elevation difference or terrain irregularity over that distance.

The hypotenuse, which is the actual length of the terrain, is calculated using the fundamental Pythagorean theorem formula:

where a is the horizontal distance and b is the vertical elevation difference.

To relate the vertical elevation difference to the degree of terrain undulation, we considered an angle θ between the terrain surface and the horizontal plane. Thus, the vertical elevation bbb is directly proportional to the tangent of angle θ multiplied by the measured horizontal distance, according to the relation:

This allows the calculation of elevation difference for any degree of undulation. For example, for a horizontal distance of 100 meters and an angle of 20°, the resulting elevation difference is approximately 36.4 meters.

Applying the Pythagorean theorem with these values, the actual terrain length is calculated as the hypotenuse of the right triangle formed, that is:

yielding a value of approximately 106.41 meters. This means that due to terrain irregularities, the real distance is 6.41 meters longer than the planar distance measured.

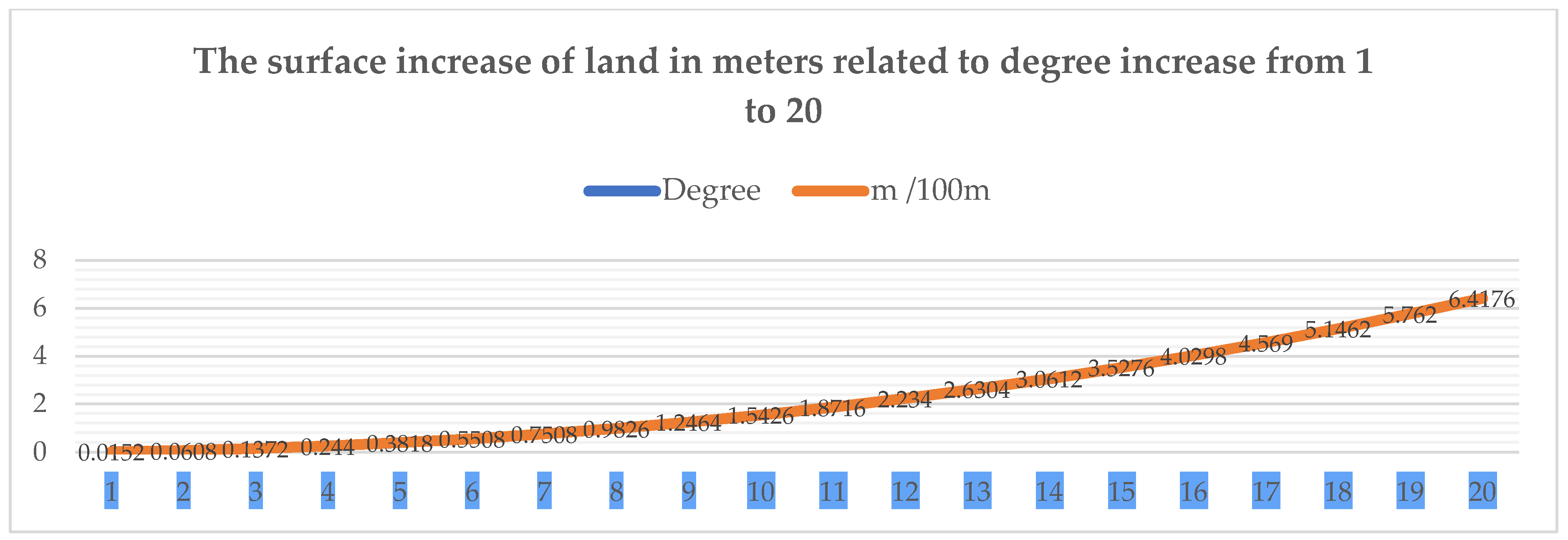

This mathematical model was applied across a range of undulation degrees, from 1° to 20°, enabling the generation of graphs that illustrate the increase in length—and consequently the real surface area of the terrain—as a function of the degree of undulation. Thus, the calculation process was based on determining the vertical difference through the tangent relation and applying the Pythagorean theorem to obtain the actual distance.

The results clearly demonstrate that terrains with significant elevation changes have an effective surface area larger than the one measured horizontally, which is essential in fields such as cadastral surveying, land valuation, agriculture, and infrastructure design.

When a piece of land is measured on a horizontal plane and assigned a length of 100 meters, this measurement represents only the “projected” distance on a flat surface, without accounting for the actual undulations and irregularities of the terrain. In reality, the land may have small or significant variations in elevation—such as hills, valleys, or slopes—that increase the true distance over the surface. Thus, if the land has a waviness degree of 20, its real length increases to approximately 106.41 meters, meaning an effective gain of over 6 meters compared to the simple planar measurement as it is presented in

Table 2.

In the agricultural and forestry sectors, precise measurement of undulated terrain is crucial for accurately calculating the scope of necessary work. For example, when determining the amount of seed required for sowing, fertilizer doses, or irrigation volumes, figures based on flat measurements may underestimate the actual needs, impacting productivity and operational efficiency. On an uneven terrain, the real treated surface is larger, and adjusting resources accordingly can increase yields and reduce waste.

Last but not least, in the planning and implementation of investments—such as building agricultural roads, irrigation systems, large-scale planting, or other infrastructure works—knowing the actual length and surface area of the land is essential for accurate cost estimation and material requirements. Ignoring the terrain’s waviness can lead to budget underestimations and project delays, negatively affecting profitability.

Therefore, rigorous measurements that consider these details help optimize costs and enable realistic planning of project stages, improving efficiency and quality outcomes.

Based on these considerations, a 10-year study was conducted in the Jiu Valley area, especially on the former tailing ponds, starting in 2015 and continuing to the present.

This study involves undulating the surfaces of the tailing ponds and planting fruit trees characteristic of the mountain area, such as the Red Melba apple and the Romanian Blue plum. These species were chosen because they have low soil quality requirements, are resistant to frost, and offer high productivity[

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Experimental Conditions

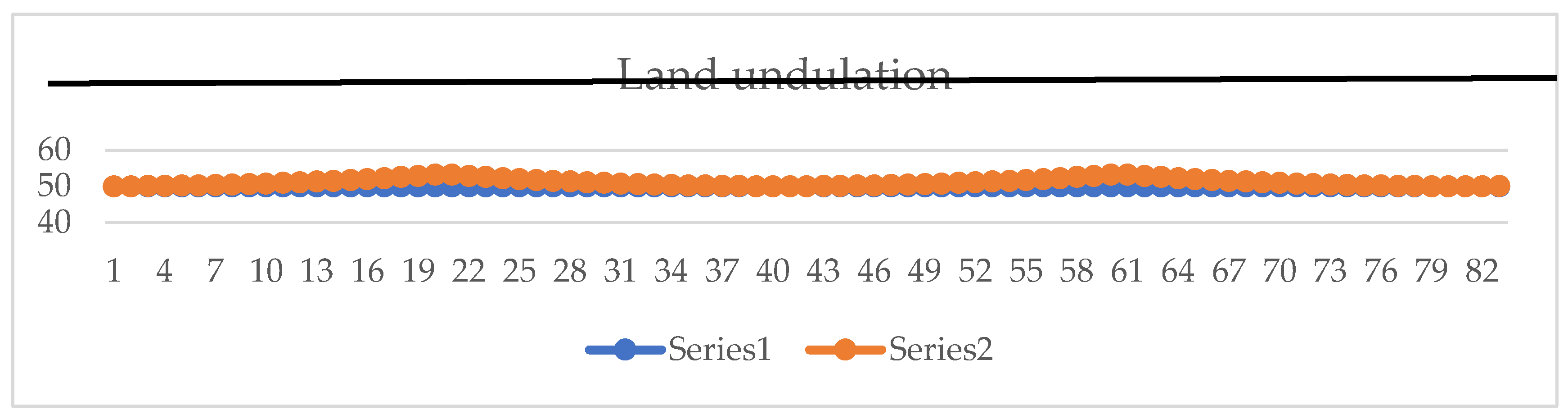

As a result of the study, we obtained the data presented in

Figure 5, which illustrates the variation in the terrain altitude over a certain section of land. The flat baseline, represented by the blue line, represents the hypothetical horizontal projection of the terrain at a constant height of 50 meters, providing a reference point for comparison. The orange line, on the other hand, follows the real terrain profile, highlighting the undulation and height fluctuations throughout the measured section. These terrain fluctuations reflect the realized variations that will occur in a landscape and which, inevitably, affect the real length of the surface. It is important to note that, despite the fact that the terrain may appear relatively flat when viewed from a horizontal perspective, its real contours add distance. In fact, the real length of the terrain will always be greater than the distance measured on the horizontal line, due to these undulations. This difference between the horizontal projection and the actual shape of the land emphasizes the importance of correctly measuring the land according to its natural contours, in order to obtain a complete and accurate picture of its dimensions.

Such elevation variations can be particularly relevant in our study because these details help to understand how the land can influence environmental conditions and its subsequent use, whether it is soil cultivation, water management or the protection of natural resources.

Figure 6 quantifies the change in actual land length as a function of the slope degree, measured over a standard 100-meter horizontal distance. The data clearly illustrates a nonlinear, almost exponential relationship between slope and surface length: as the degree of undulation increases, the real surface distance expands at an accelerating rate.

At lower slope degrees (1-5), the increase in land length is relatively small and barely noticeable. However, as the slope surpasses 10 degrees, the rate of increase becomes more pronounced. By the time the slope reaches 20 degrees, the surface length exceeds the original horizontal distance by more than 6 meters. This exponential growth highlights the critical impact that even slight increases in slope can have on land measurement.

Such insights are crucial for precise land evaluations, as they influence a variety of fields, including land valuation, agricultural or forestry project planning, and infrastructure budgeting.

For instance, when calculating the resources required for agricultural or forestry activities, or when planning infrastructure projects like roads, irrigation systems, or drainage, overlooking the surface increase could result in significant underestimation of necessary materials, labor, or overall project costs. Accurately accounting for these surface variations ensures that resources are allocated properly and helps avoid potential delays or budget overruns.

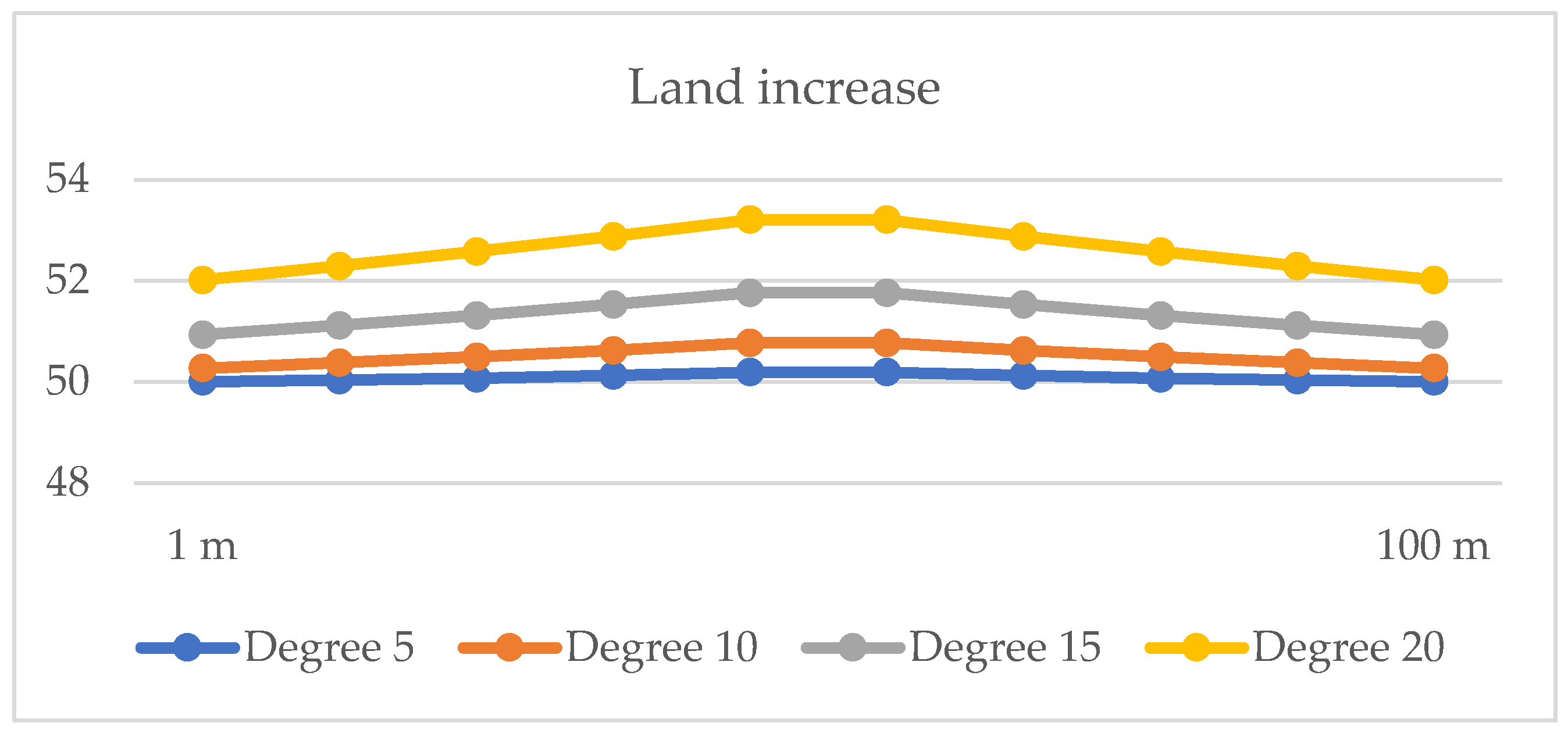

The

Figure 7 presents a comparative analysis of how varying slope degrees—5, 10, 15, and 20 degrees—impact the measured length of land over a fixed horizontal distance. The data reveals a clear trend: as the degree of terrain undulation rises, so does the actual surface length, with the highest slope (20 degrees) causing the most significant increase. This upward trend emphasizes the fact that a terrain’s natural undulations, such as slopes and hills, effectively expand the available land for cultivation by increasing the actual surface area compared to its horizontal projection.

The increase in surface area as the slope intensifies is crucial, especially in agricultural contexts. For farmers, this means that even a relatively steep incline could offer more usable land than initially expected.

In fact, land that appears to have limited potential due to its slope may, in reality, provide a significantly larger area for planting or cultivation. This factor becomes particularly important when planning crops, determining irrigation needs, or assessing soil fertility over a given area. For instance, on a 20-degree slope, the actual land available for cultivation may be up to 6 meters longer than the flat horizontal projection, which could translate into substantial gains in agricultural output over large areas.

In the agricultural context, carbon sequestration is the natural process by which carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere is captured and stored in plants and soil, a process that is essential in combating climate change, and planting trees on hilly land contributes significantly to this strategy.

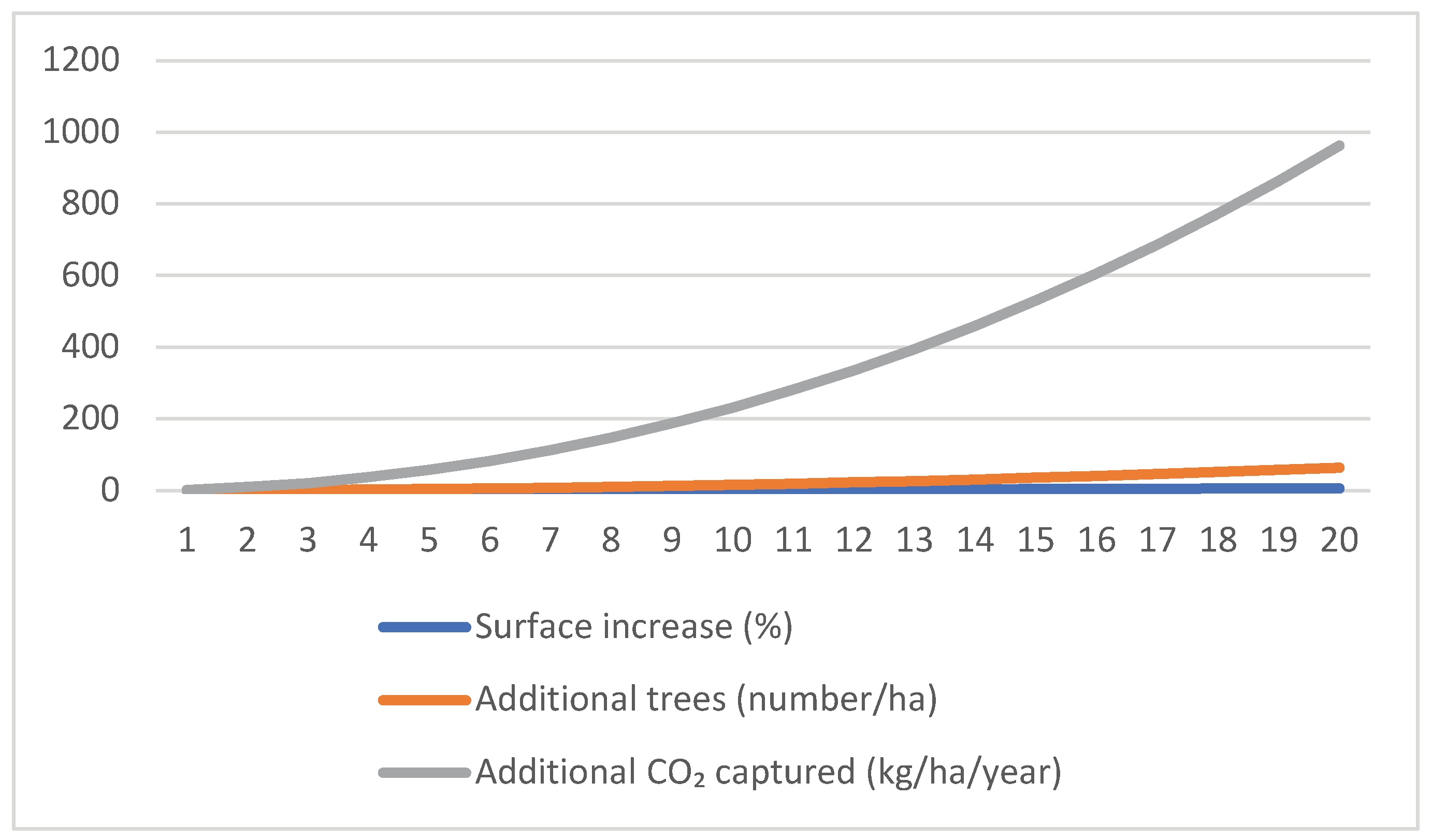

When comparing flat land with hilly land, it is observed that the actual land area increases with increasing slope. As previously highlighted, this expansion allows a greater number of trees to be planted per hectare, without compromising the optimal spacing required for healthy development. Each additional tree contributes directly to the capture of CO₂ from the atmosphere through the process of photosynthesis.

Trees absorb CO₂ and transform it into organic matter, storing carbon in their trunk, branches, leaves, fruits and root system. In this way, trees become long-term “carbon reservoirs”. On average, a mature fruit tree can sequester between 10 and 22 kg of CO₂ per year. In the case of hilly land, the additional number of trees per hectare can lead to an additional sequestration of approximately 960 kg of CO₂ per hectare per year, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

This increased sequestration capacity not only improves the environmental benefits of the orchard but also contributes to the long-term sustainability of the agricultural system. Over time, this additional carbon storage can play a meaningful role in regional and even global carbon balance efforts.

Figure 8.

The quantity of CO2 captured kg/ha/year.

Figure 8.

The quantity of CO2 captured kg/ha/year.

In addition to sequestering carbon in tree biomass, soil also plays a crucial role in carbon storage. Tree root systems promote humus formation and support the development of beneficial soil microorganisms, contributing to the accumulation of organic matter. Through appropriate management practices - such as contour planting and erosion control - organic carbon is more effectively conserved in the soil, while the risk of loss through erosion is significantly reduced.

An additional advantage of this system is the creation of a more favorable local microclimate. Trees help to lower soil and air temperatures through shading and evapotranspiration, which maintain moisture and stabilize the growing environment. These factors promote soil health and support the ongoing process of carbon sequestration.

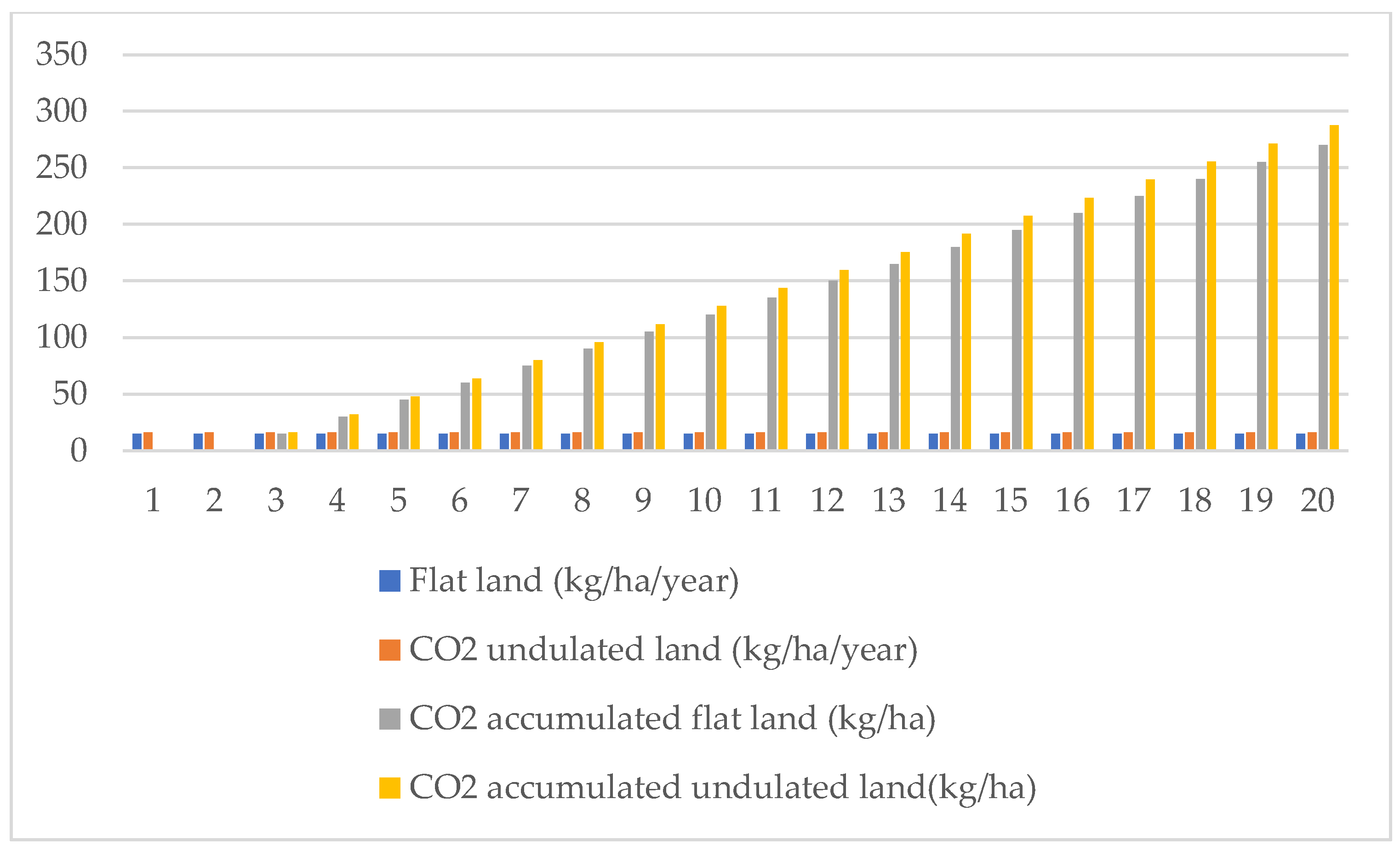

In the long term, carbon sequestration becomes increasingly significant. As trees mature, their annual CO₂ capture increases, and the soil continues to accumulate organic carbon at a steady rate. Over a period of 10 to 20 years, hilly land will have a clear advantage over flat land, both in terms of agricultural productivity and greenhouse gas emission reductions, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

The increase of captured CO2 kg/ha/year.

Figure 8.

The increase of captured CO2 kg/ha/year.

3.2. Correlation Between Undulation Land and Flat Land

Due to the undulation of the land and other agronomic factors, including crop type, planting density, climatic and soil conditions, but also the specificity of the land, especially in areas with established slopes, the analysis of the undulation of the land plays an essential role, since its undulation effectively increases the cultivable area, which can have a significant impact on the crop yield. Based on the data collected, it can be estimated that land with a slope of 20 degrees has an actual area approximately 6.4 meters longer than a horizontal projection of 100 meters. This implies that, on land with significant slopes, the effective cultivable area increases, which can lead to higher productivity compared to flat land. Thus, for fruit tree crops, such as apple or plum trees, where the distances between trees are 2.5-3 meters in a row and 4-4.5 meters between rows, increasing the available area per hectare can lead to a proportional increase in the number of trees, and consequently, in the amount of fruit obtained.

Thus, if in areas with slopes of 20 degrees, the actual length of the land increases by 6.4 meters for every 100 meters measured on flat land, this means that, on one hectare, a significant additional area can be cultivated. Given that at a density of 1000 trees per hectare (almost 2.5 meters between trees per row and 4.5 meters between rows), each increase of 6.4 meters per hectare can add an additional number of trees, which will contribute to increasing fruit production.

Considering that an apple tree produces an average of 20 to 30 kilograms of fruit per year, and the additional density brought by the undulation of the land is 6.4 meters per hectare, then a significant increase in the amount of fruit per hectare can be estimated. If we add approximately 10-20 additional trees per hectare due to the increase in the length of the land, this can add between 200 and 600 kilograms of additional fruit, depending on the type of crop.

Thus, we started planting the trees as shown in

Figure 8, and obtained the following: In the first 10 years, for Red Melba apple and Romanian Blue plum trees, the production is considered zero during the first 2 years due to the acclimatization period of the trees, and then gradually increases until production stabilizes as is presented in

Table 3. Red Melba apple produces approximately 20–30 kg/tree/year, while Romanian Blue plum produces approximately 15–20 kg/tree/year.

Figure 8.

Tree on undulating land.

Figure 8.

Tree on undulating land.

3.3. Economic Impact

The land contouring project for CO₂ capture requires a significant initial investment but can bring considerable benefits in the long term, both ecologically and financially. Regarding implementation costs, these can range from €800 to €1,500 per hectare, depending on the complexity of the land and the necessary equipment. These costs include terracing works, equipment acquisition, and the labor required for the realization and maintenance of the project.

On the other hand, revenues from the sale of CO₂ emission certificates can range from €67 to €77 per hectare per year, depending on the price of the certificates, which fluctuates between €70 and €80 per ton of CO₂. One hectare of land can capture approximately 0.96 tons of CO₂ per year. Therefore, the annual income generated from the sale of green certificates can be recovered in a period of 10–15 years, excluding other sources of income or external funding as we can see in

Table 4.

An important factor that can significantly influence the profitability of the project is the possible external funding from the European Union, targeted at environmental or agricultural programs. Such funding can reduce initial costs and, consequently, the payback period of the investment. For example, in the case of 30% funding, the implementation costs are reduced, and the payback period can be significantly shortened, reaching about 8–14 years, depending on the initial value of the investment.