Introduction

Plants are constantly under threat of insect herbivory. Being sessile in nature, they rely on physical defenses (such as trichomes) that are often complemented by chemical defenses (secondary metabolites such as alkaloids and phenolics) to deter insect herbivores (Kariyat et al. 2018; Paudel et al. 2019; Musser et al. 2002). Chemical defenses can be constitutive (always present in the plant) or induced (produced in response to an insect attack) and often act as a second line of defense for plants. Induced defenses are often regulated by plant signaling molecules and/or phytohormones such as jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA).

Herbivory by chewing herbivores causes an accumulation of JA in the attacked plant (McCloud and Baldwin 1997; Karssemeijer et al. 2019). JA accumulation has been shown to induce the synthesis of anti-herbivore defense proteins such as proteinase inhibitors and polyphenol oxidase (Farmer and Ryan 1990; Thaler et al. 1996). These defenses are typically antinutritive for the herbivores consuming them, and lead to lower palatability of plant tissue, thus reducing caterpillar relative growth rates on defense-induced plants (Thaler et al. 1996; Lin et al. 2020; Paudel et al. 2019). SA acts antagonistically to JA and several studies demonstrate SA or its derivatives counteracting JA and its effects on defense signaling (Doherty et al. 1988; Pena-Cortes et al. 1993; Doares et al. 1995). While leaf-chewing insects usually elicit the JA pathway, piercing-sucking or phloem-feeding insects are negatively affected by defenses activated via the SA pathway (Li et al. 2006; Thaler et al. 2010).

These physical and chemical defenses are the means through which plants and insects compete with one another. To counter plant defenses, insects evolve novel counter defense strategies. Insects can employ behavioral changes, for example, caterpillars mow down plant trichomes before feeding on leaf tissue (Hulley 1988), essentially rendering plant primary defenses obsolete. Some beetles have been observed biting milkweed midribs before eating leaf tissue to reduce exudate consumption (Dussourd 1999), and caterpillars have been observed cutting trenches in plant tissues presumably to decrease exposure to defenses (Dussourd and Denno 1991). Beyond physical disruption, insects have also been shown to be capable of countering plant chemical defenses. For example, they can detoxify and sequester toxic plant-derived compounds after their ingestion and make plant material more palatable (Snyder et al. 1993; Snyder et al. 1994). Alternatively, they can also interfere with plant defense signaling and inhibit the production of plant defense compounds. For example, the saliva of the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda - FAW) contained phytohormones, and treating cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) with the phytohormones that were present in FAW saliva suppressed tomato defenses 96 hours after treatment (Acevedo et al. 2019).

However, insect salivary enzymes can elicit different responses in plants depending upon the enzyme and the specific plant-insect interaction under consideration. The salivary enzyme glucose oxidase (GOX) from Lepidopteran caterpillars can both induce (Tian et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2020) and suppress (Musser et al. 2002; Musser et al. 2005; Zong and Wang 2004; Deizel et al. 2009; Bede et al. 2006) plant defenses. In the present snapshot of this evolutionary arms race between plants and insects, it seems difficult to generalize the role of GOX in plant-insect interactions, whether it acts as an elicitor of plant defenses or suppressor. Furthermore, there is disagreement concerning its primary mode of action, as this changes with the specific system of study. Despite numerous proposed mechanisms for the mode of action of GOX, there is no clear consensus on which mechanism is correct. Discovering the precise mechanism is critical for understanding the role of GOX in plant-insect interactions. Our discussion aims to review the current state of GOX in plant-insect interactions, propose a new model of GOX action, and examine potential strategies in using tomatoes as a system to elucidate the mechanism of GOX action.

Glucose Oxidase

Glucose oxidase (GOX) belongs to the GMC oxidoreductase family (Cavener 1992) and was initially discovered in the fungal species Aspergillus niger (Heller and Ulstrup 2021). In insects, GOX was initially discovered in the caterpillar Helicoverpa zea in 1999, and since then has also been reported in many other Lepidopteran caterpillar saliva (Eichenseer et al. 1999; Eichenseer et al. 2010). Although primarily observed in caterpillar saliva, it is also expressed in caterpillar labial glands (that produce saliva), caterpillar midguts, and other tissues. It catalyzes the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and d-gluconolactone from glucose in the presence of oxygen (Cavener 1992). GOX has also been found in bees and honey, where it acts as an antimicrobial agent (White et al. 1963), plays a role in detoxifying plant nectar by reducing phenolic content (Liu et al. 2005), and has been proposed to contribute to social immunity (Lopez-Uribe et al. 2017).

Compounds derived from insects (such as insect oral secretions or insect saliva) can be broken down into two functional categories: effectors (which disrupt/ suppress plant defensive responses) and elicitors (which elicit/induce plant defensive responses) (Jones et al. 2021). GOX has been reported to play both roles. GOX from the caterpillar species H. zea was initially reported as an effector in the cultivated tobacco plant Nicotiana tabacum, reducing the amount of nicotine (a plant defense) accumulation in leaves (Musser et al. 2002). Zong and Wang (2004) found that feeding by two other GOX-producing Helicoverpa species: Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta suppressed nicotine induction in N. tabacum compared to mechanical wounding. Application of H. zea labial gland extract with active GOX to mechanically damaged N. tabacum leaves also showed suppression of nicotine accumulation compared to labial gland extract with inactive GOX and water treatments (Musser et al. 2005). A study on Medicago truncatula showed that fungal GOX and H2O2 application to mechanically damaged leaves resulted in lower transcription of certain defense-related genes (Bede et al. 2006). Caterpillar saliva is released through an opening in the caterpillar’s lip called the spinneret, which is external to the mouth cavity. Cauterization of the spinneret prevents secretion of saliva from labial glands. A study on Arabidopsis thaliana found that cauterizing Spodoptera exigua caterpillar spinnerets increased JA levels at least 4 times more than those seen in plants exposed to caterpillars with intact spinnerets (Weech et al. 2008), indicating the importance of saliva-derived compounds in defense suppression. Generalist caterpillars typically have higher amounts of GOX compared to specialist caterpillars (Eichenseer et al. 2010), possibly linked to a generalists’ need to suppress defenses in a wider variety of plants (although later research on other plant systems calls into question how widespread GOX’s benefits as an effector are). GOX has also been shown to cause stomatal closure in tomatoes, soybean, and maize, which might reduce plant volatile signaling, acting as a suppressor of indirect plant defenses (Lin et al. 2021; Jones et al. 2023).

In cultivated tomato however, multiple studies have consistently documented the fact that GOX acts as an elicitor of plant defenses. Musser and colleagues (2005) found that insects feeding on non-wounded tomato plants had twice the weight of insects that fed on all wounded tomato treatments (with water, purified GOX, and labial extracts with active and inactive GOX) after ten days of feeding. They also found that trypsin inhibitor levels were significantly higher in their wounded plant treatments when compared to non-wounded plants, and that salivary gland extracts with active GOX showed lower trypsin inhibitor levels than plants treated with purified GOX, water, or inactivated GOX salivary extracts. Tian and colleagues (2012) showed that H. zea caterpillars with intact spinnerets significantly induced higher PIN2 gene expression (a JA-inducible gene that is involved in the synthesis of proteinase inhibitors) than caterpillars with ablated spinnerets in tomatoes after 48 hours. They also showed that JA levels were around 13 and 40 times higher in saliva-treated plants than in buffer-treated and control plants respectively after 4 hours of treatment. These findings indicate that saliva induces early JA induction while defense genes are induced much later. However, our unpublished data indicates that GOX is not responsible for the JA elicitation. In another study, Lin and colleagues (2020) showed that applying mechanical damage and fungal GOX to cultivated tomato plants led to a high level of trypsin inhibitor when compared to other treatments.

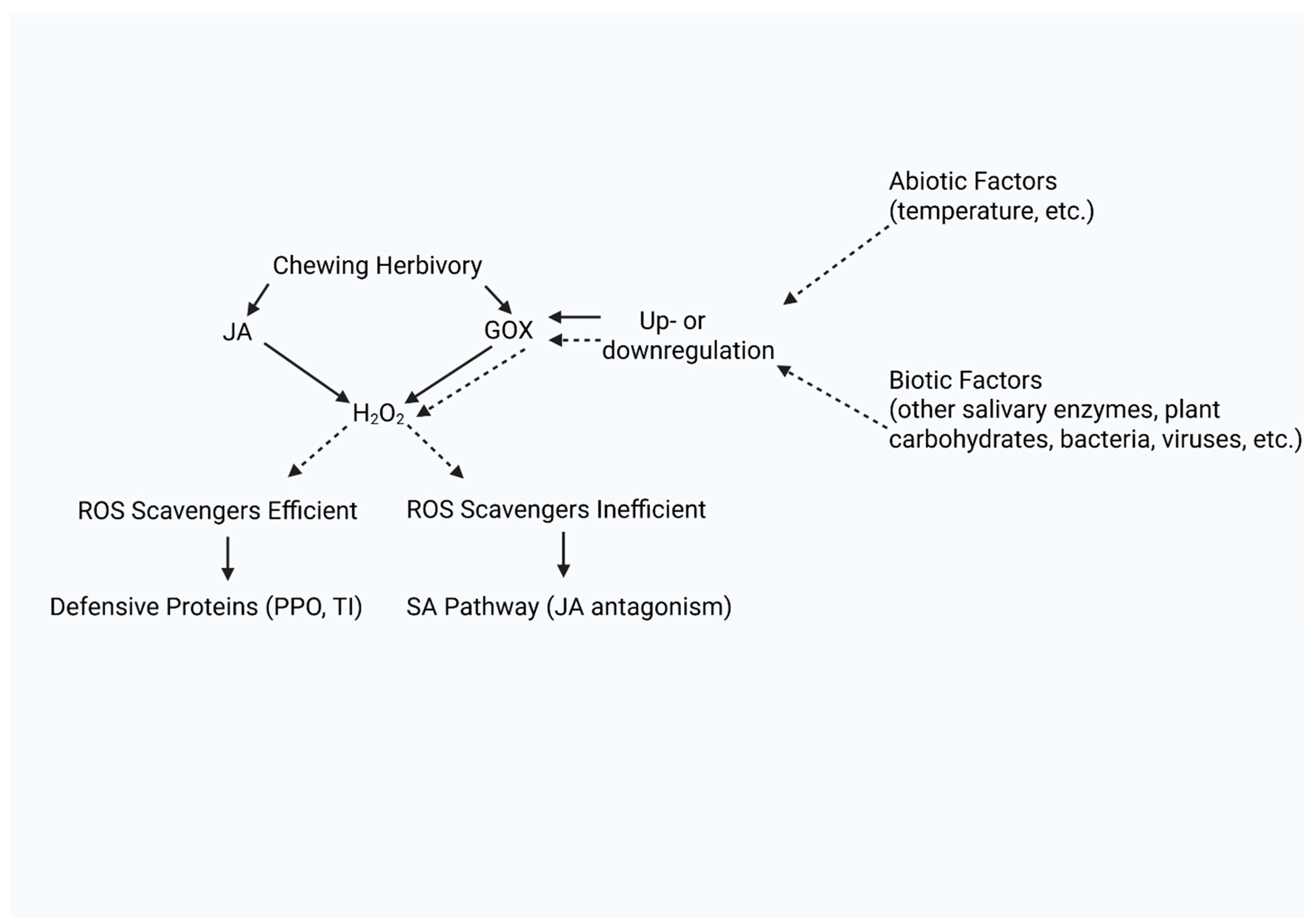

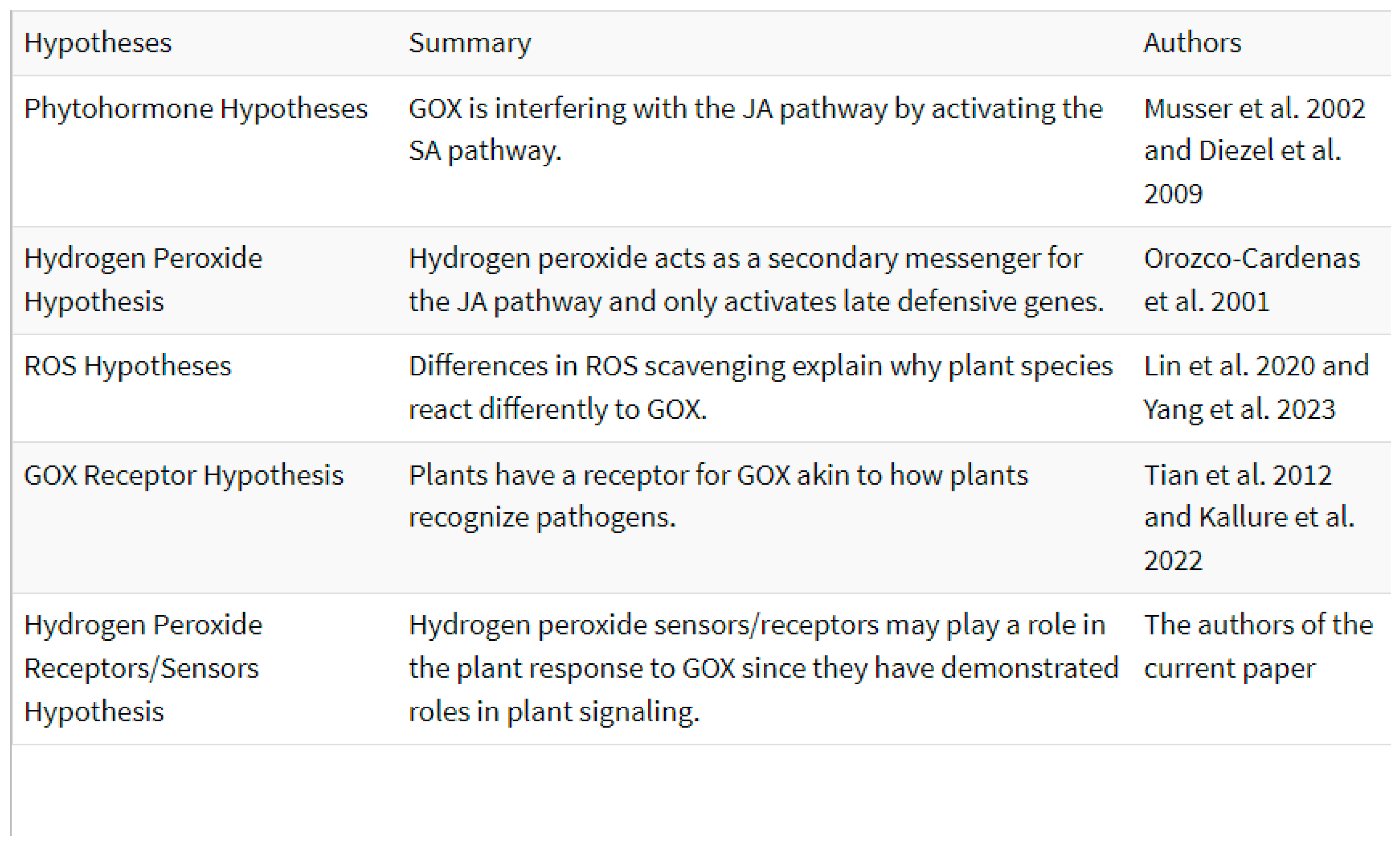

With GOX playing dual roles of defense suppression and induction, there have been multiple proposals for how GOX causes these differences in plant defenses (

Table 1). The exact mechanism of GOX action however, remains undecided.

Mechanism of GOX Action

Phytohormone signaling: One proposed mechanism of GOX action is through the activation of phytohormonal crosstalk. In the publication that first reported GOX as an effector, the authors speculated that GOX may be acting to directly inhibit JA or disrupt it by interfering with its interactions with other phytohormonal pathways (Musser et al. 2002). In a follow up study on transgenic, SA-deficient tobacco plants, caterpillar feeding with intact salivary glands still elicited lower amount of nicotine induction than feeding from caterpillars with ablated salivary glands, which led the authors to speculate that this was a change not solely mediated by SA and that perhaps ethylene biosynthesis was involved in GOX’s suppression of nicotine (Musser et al. 2005). Diezel and colleagues (2009) found that two insect species elicited varying phytohormonal responses in Nicotiana attenuata. Herbivory by Spodoptera exigua (caterpillar with higher GOX activity) resulted in higher SA levels and lower JA levels than Manduca sexta herbivory. In a study done prior to the discovery of GOX in caterpillars, Bi and colleagues (1997) found that H. zea feeding resulted in a significant increase of SA in Gossypium hirsutum (cotton).

These results are further complicated by studies on other Solanaceous plant species such as tomatoes that show elevated JA-mediated defenses in response to GOX (Tian et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2020). Therefore, there seems to be species-specificity in GOX interaction with SA and JA.

Additionally, supplementing M. sexta oral secretions with GOX decreased ethylene (ET) emissions by 25% compared to M. sexta oral secretions alone, suggesting a modulation to the ethylene pathway (Diezel et al. 2009). They postulated that GOX may act as a negative regulator of ET production in N. attenuata which could affect other phytohormone levels (Diezel et al. 2009). Zong and Wang (2004) hypothesized that GOX leads to H2O2 production, which then leads to ethylene production that results in the inhibition of nicotine biosynthesis. Taken together, these studies imply that there is more behind GOX action than simply activating a single phytohormonal pathway using JA, SA, or ET. GOX may activate different phytohormonal pathways in different plant species, however the mechanism(s) underlying this interaction are unclear.

Hydrogen Peroxide as Secondary Messenger: Another proposed mode of action for GOX is through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), namely, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which can act as a secondary messenger downstream of the JA-phytohormonal pathway. Orozco-Cardenas and colleagues (2001) proposed a model in which H2O2 acted as a secondary messenger in tomato plants to activate late defensive genes. Plant leaves contain substantial levels of glucose, which serves as the substrate for GOX and results in H2O2 production. Orozco-Cardenas and colleagues (2001) showed that excised tomato leaves treated with GOX and supplemented with glucose activated plant defense genes, but not signaling genes. Applying H2O2 has been able to elicit similar defensive responses to GOX in some plant species (Lin et al. 2020). This model is also supported by other studies that show H2O2 plays a role in plant signaling (Bi et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2020). These studies indicate that the presence of GOX-derived H2O2 elicits plant responses and plays a role in plant signaling. Different plants can contain different levels of glucose, resulting in varied H2O2 production, which can partly explain species-specific differences in GOX action.

ROS Scavenging Efficiency: This hypothesis partially explains species-specific responses through antioxidant capacity. Several Solanaceous plants showed varying reactions (either an induction of defensive proteins or no response at all relative to other treatments) to GOX treatment (Lin et al. 2020). While tomatoes and soybeans showed GOX-induced stomatal closure, cotton plants were unaffected (Lin et al. 2021). The authors of these papers suggested that differences in plant responses could be due to how effectively plants can scavenge ROS, causing variations in defensive responses and stomatal dynamics (Lin et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2021). More recent work by Yang and colleagues (2023) presented a model in which the herbivore Plutella xylostella uses GOX to produce H2O2, which itself activates the SA pathway to interfere with JA signaling while peroxidase is used to scavenge H2O2 and activate defenses. The authors also note that the differences in plant response may be due to differences in ROS scavenging between plant species (Yang et al. 2023). Plants contain many antioxidant enzymes such as catalases, peroxidases, and superoxide dismutases that regulate H2O2 levels in tissues (Prasad et al. 1994; Li and Yi 2012). Overall, it seems likely that improper ROS scavenging can result in the continuous presence of ROS molecules resulting in varied signaling responses.

GOX and Hydrogen Peroxide Receptors/Sensors: This hypothesis suggests direct molecular recognition and a dedicated pathway towards GOX action. Initial speculations of the presence of a possible GOX receptor in plants akin to R-gene-like receptors for pathogens have been made (Tian et al. 2012), with a recent review referring to this idea too (Kallure et al. 2022). However, no GOX receptors have been identified yet, and most phenomena can be explained by H2O2-mediated responses. The presence of a GOX receptor and further molecules in a signaling cascade would prove more towards a specialized pathway dedicated to GOX action, rather than GOX action via shared molecules with other signaling pathways.

Additionally, H2O2 receptors and sensors in A. thaliana have been investigated (Bi et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2020). The leucine-rich-repeat receptor kinase HPA1C was found to be activated by H2O2. HPA1C is required for stomatal closure by mediating H2O2 induced activation of calcium channels in guard cells (Wu et al. 2020). The cytosolic thiol peroxidase PRXIIB was found to act as a sensor for H2O2, playing a role in stomatal immunity (Bi et al. 2022). These H2O2 sensors have an established role in plant signaling but could also be involved in plant responses to GOX. Lin and colleagues (2021) found that GOX caused stomatal closure in the cultivated tomato and Glycine max (soybean), but not in Gossypium hirsutum (cotton). As these receptors and sensors influence stomatal dynamics, it seems that variations in them may partially explain why plants have different responses to GOX.

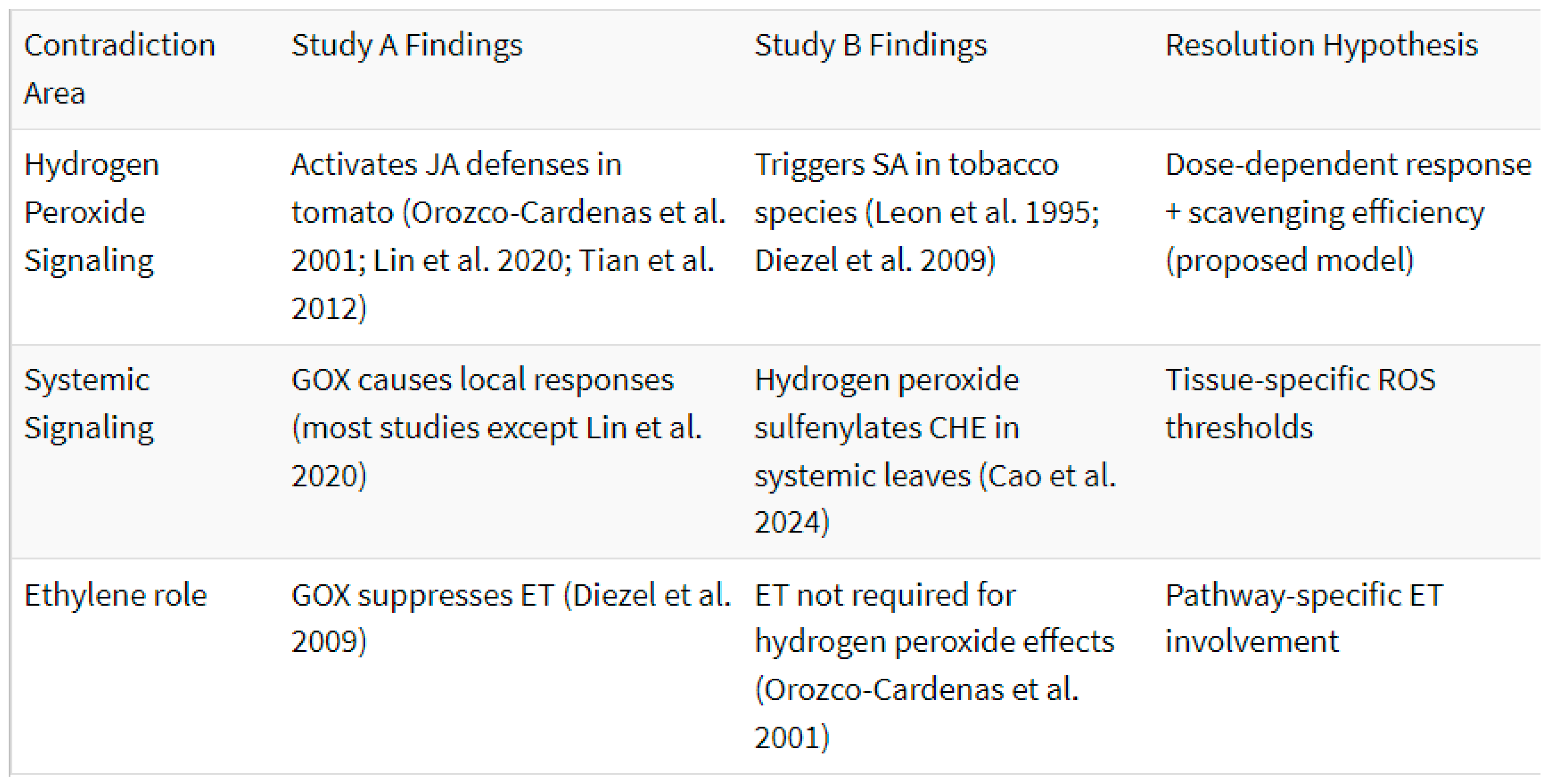

While all these mechanisms have been proposed, none have been definitively and widely demonstrated (

Table 2). GOX signaling has varying results. Plants within the same family seem to react differently to GOX despite their somewhat close relation (Musser et al. 2005; Lin et al. 2020). The question then becomes why are these plants reacting differently to GOX?

GOX Regulation by External Factors

GOX activity and expression are influenced by diverse abiotic and biotic factors which can lead to context-dependent functional outcomes. Elevated temperatures alter carbohydrate metabolism pathways linked to GOX functionality. A study showed that H. zea caterpillars reared on lower temperatures showed higher amounts of salivary GOX, potentially because of a growth-immunity trade-off. Caterpillars reared at lower temperatures also elicited higher amounts of defense proteins in tomatoes post herbivory (Paudel et al. 2020). Plant secondary metabolites and sugar content shape GOX activity in herbivores. For example, H. armigera feeding on artificial diet (high sugar, no defenses) exhibited elevated GOX activity compared to those feeding on tobacco leaves (Hu et al. 2008). In another study, H. zea larvae feeding on cotton and soybean showed lower GOX activity than diet-fed or geranium-fed H. zea larvae (Eichenseer et al. 2010). This shows how GOX activities are affected by insect diet. Finally, bacteria and polydnaviruses (PDVs) can also affect the secretion of GOX (Wang et al. 2017). H. zea caterpillars infected with PDVs from parasitoid wasps reduced GOX transcript levels and dampened plant immune responses, which led to enhanced caterpillar growth rates (Tan et al. 2018). This multi-trophic interaction between a virus, parasitoid, caterpillar, and plant further stresses on how multiple factors could lead to differential effects across systems.

It is also important to note that GOX does not exist and function in isolation. Insects have multiple other salivary constituents that could function in influencing GOX activity. Local glucose concentrations can be increased by activities of other salivary enzymes such as salivary amylase (hydrolyzes starch) (Asadi et al. 2010; Rivera-Vega et al. 2017), fructosidase (cleaves sucrose into glucose and fructose) (Rivera-Vega et al. 2017), and glucosidases (hydrolyze polysaccharides into glucose) (Rivera-Vega et al. 2017). Increased glucose (substrate) availability for GOX can enhance GOX activity. It has been demonstrated that insects can sequester plant carotenoids in many places of the body, including the mandibular and labial salivary glands (Eichenseer et al. 2002). These carotenoids may act as antioxidants, but the authors of the previous study pointed out that the antioxidant effects of the carotenoids were not enough to protect insects from the prooxidant properties of tomato leaves. These components can create a dynamic system influencing GOX action.

A New Model for GOX Action: ROS Threshold Dependent Defense Toggle

To address the limitations of previous models of GOX action, we propose a new model. Briefly, the reaction of GOX with glucose results in the production of H2O2, which acts as a signaling molecule. Species-specific antioxidant enzyme pathways determine H2O2 persistence in plants. H2O2-concentration dependent phytohormonal pathway activation leads to the activation of plant defense genes. Low H2O2 concentrations activate JA while high concentrations result in SA dominance.

Plant defensive signaling is influenced by many factors. The Orozco-Cardenas model suggests that when a plant is damaged, the phytohormone JA mediates the activation of early defense genes and H2O2 acts as a secondary messenger to activate late defense genes (Orozco-Cardenas et al. 2001). Their model decouples phytohormones from certain aspects of defense signaling, since theoretically H2O2 alone should be enough to activate defensive genes. Furthermore, since one of the products of GOX action is H2O2, it is possible that H2O2 production alone is sufficient to explain the elicitation of plant defenses. Their study also agrees with the findings of Tian and colleagues (2012) and Lin and colleagues (2020) both of which report elicitation of defenses for the cultivated tomato.

However, it conflicts with Musser’s first hypothesis (2002) and the Diezel model (2009). Although both the Diezel model (2009) and the Orozco-Cardenas model (2001) claim H2O2 as the responsible molecule for triggering defenses related to phytohormonal pathways, the Diezel model claims it is responsible for activating the SA pathway while Orozco-Cardenas claim that it activates defensive genes that are related to the JA pathway (although Diezel and colleagues also say that GOX may be activating SA directly). It is possible that the reaction to GOX is species specific, but this still does not explain the underlying mechanism of what’s driving the observed differences.

The Orozco-Cardenas model (2001) and the Diezel model (2009) also come into conflict with the GOX receptor hypothesis. Again, if H2O2 is responsible for the defensive response, then a plant would not necessarily require a GOX-specific receptor to mount a defensive response and would benefit from the evolution of a specialized H2O2 pathway, independent of GOX action. This idea coupled with the fact that no GOX receptor has been identified make the GOX receptor model currently unsupported (although to our knowledge, no one has actively searched for such a receptor). If H2O2 is what leads to defense signaling, and it is implemented in both antagonistic pathways, then what explains the difference observed in how different species react to GOX?

Another more serious difficulty is that there is a body of literature that shows that H2O2 causes a secondary ROS burst, (comprising of multiple other ROS molecules) which leads to the activation of the SA pathway. Leon and colleagues (1995) found that injecting certain concentrations of H2O2 into cultivated tobacco caused significant increases in SA levels. Summermatter and colleagues (1995) did similar work on A. thaliana and found that by injecting leaves with H2O2 concentrations of 50 mM or higher caused changes in the amounts of bound SA (free SA increased during the first 24 hours, and then SA concentrations returned to basal levels which was interpreted as a conversion to the bound form of SA). How can the plants be using the same molecule, i.e H2O2, to activate both pathways? This is partly addressed by the reactive oxygen species scavenger hypothesis presented by Lin and colleagues (2020) and the model produced by Yang and colleagues (2023).

Insect herbivory or the presence of insect-derived compounds can trigger rapid bursts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants within minutes (Block et al. 2018; Sperdouli et al. 2022). The production of ROS such as H2O2 and superoxide (O2-) is often mediated by membrane-localized oxidases. These ROS molecules participate in signaling cascades that activate various defense responses. They can act as secondary messengers, being involved in changes in gene expression and inducing the production of defensive compounds (Orozco-Cardenas et al. 2001). ROS molecules are also involved in many hormonal pathways such as the JA and SA pathway which further regulate plant defense responses (Orozco-Cardenas et al. 2001; Leon et al. 1995; Louis et al. 2013).

To manage the potentially damaging effects of excessive ROS, plants have evolved sophisticated ROS-scavenging mechanisms. These include enzymatic antioxidants such as catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase, as well as non-enzymatic antioxidants like ascorbic acid, glutathione, phenolics, carotenoids, and non-protein thiols (Prasad et al. 1994; Li and Yi 2012; Yu et al. 2019; Shen et al. 2018). The delicate balance between ROS production and scavenging is crucial towards maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and determining the outcome of ROS signaling (Bi and Felton 1995).

Levine and colleagues (1994) reported that their applications of exogenous H2O2 at concentrations as high as 10 mM to soybean cell suspension cultures were eliminated within 10 minutes, indicating that perhaps H2O2 effects are dose dependent. This agrees with the observations of Leon and colleagues (1995) that only certain concentrations caused significant increases in SA levels as well as another study by Neuenschwander and colleagues (1995) that showed that out of three concentrations of H2O2 tested, only the highest concentration caused free SA accumulation that differed from the control in N. tabacum. It is also supported by a recent paper that demonstrated that systemic acquired resistance and the associated accumulation of salicylic acid in Arabidopsis thaliana is dependent upon an optimal dose of H2O2 (Cao et al. 2024). This would mean that ROS scavenging enzymes are equally relevant as ROS molecules themselves, as they decide how quickly a species can deal with the accumulation of ROS.

Our new model states that both the act of herbivory and subsequent exposure to GOX create ROS bursts (H

2O

2), that induce phytohormonal signaling. Which defense pathway is activated and maintained (SA or JA pathway) depends upon the concentration and rate of H

2O

2 production as well as the efficiency of the ROS scavenging enzymes (

Figure 1). GOX may act as an elicitor when H

2O

2 is kept under a certain concentration and may act as an effector when it hits a higher concentration and elicits an SA burst. Under our model H

2O

2 acts as a secondary messenger of the JA pathway, as in the Orozco-Cardenas model (2001).

It is important to note that these predictions apply to a locally damaged leaf. Systemic signaling in plants is variable and not a part of our model. To our knowledge, only one study has investigated systemic leaf signaling in the context of the effects of GOX (Lin et al. 2020). Cao and colleagues (2024) demonstrated that H2O2 sulfenylates a transcription factor (CHE - CCA1 Hiking Expedition) only in systemic leaves which leads to Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR), while higher levels of ROS in local tissues cause further oxidation of cysteine residues in CHE. This study leaves open the possibility that insects that produce high levels of GOX may be able to cause systemic signaling in certain plants, which could be extremely costly for a plant to do if it is dealing with pests that are vulnerable to JA-related defenses and instead produces SA-related defenses.

It is also important to note that plant responses may be different in different leaves within the same plant due to factors relating to age such as differences in ROS scavenging ability. This is an important distinction, as many previous studies do not seem to highlight the differences that may be apparent in GOX-induced signaling within a single plant. Other additional factors may include the availability of substrate (in this case, glucose), as the availability of glucose determines the production of hydrogen peroxide. Orozco-Cardenas and colleagues (2001) demonstrated that defense gene expression was only induced by a combination of GOX and glucose, not by GOX alone. Louis and colleagues (2013) found that by supplementing mechanical damage treatments in maize with GOX and glucose, they could cause significantly higher induction of maize protease inhibitor compared to mechanical damage treatments involving GOX and glucose alone. Lin and colleagues (2020) also noted in their work that the differences they observed between species in response to GOX may be due to differences in plant carbohydrates such as glucose, starch, and fructose content (e.g., starch may be broken down into glucose by salivary amylase) as well as differences in ROS scavenging. Together, these results indicate that important carbohydrate differences in plants may contribute heavily to how a plant reacts to GOX.

Finally, while we use the term concentration regarding H2O2 it is also likely that lower concentrations at higher amounts may cause results similar or identical to those seen using smaller amounts of H2O2 at higher concentrations. While this model does seem to resolve some difficulties that other models do not, it requires rigorous testing. One system that is attractive for research is the cultivated tomato.

Cultivated Tomato as a System to Investigate GOX Action

The cultivated tomato is a Solanaceous plant related to other crops such as eggplants, peppers, and potatoes. Originating from Mesoamerica (Razifard et al. 2020; Blanca et al. 2022), it has since become a globally produced vegetable with 186 million tons being produced in 2022 (FAO 2023). Besides being an economically important crop, it has served as a model system for many avenues of research like plant pathology, stress tolerance, genetics, and plant-insect interactions. Multiple abiotic factors such as extreme temperatures (Dat et al. 1998; Prasad et al. 1994), high intensity light (Dat et al. 2003; Vandenabeele et al. 2004) and drought (Moran et al. 1994; Selote and Khanna-Chopra 2004) have the potential to produce oxidative stress/ ROS accumulation in plants which could lead to damage. For this reason, topics like these have been studied in tomato with the goal of identifying resistant genotypes. Several studies exist comparing the heat tolerance (Abdul-Baki 1991; Haque et al. 2021), drought tolerance (Conti et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2017), chilling tolerance (Cao et al. 2015), and salt tolerance (Pawar et al. 2025) of different types of tomatoes. The tomato genome was sequenced in 2012 (The Tomato Genome Consortium). This has led to projects such as an examination of the genetic variation in multiple tomato accessions and wild relatives (The 100 Tomato Genome Sequencing Consortium et al. 2014) and genetic examinations of tomato evolution (Lin et al. 2014).

Tomatoes have been widely utilized to understand plant-insect interactions. The plant enzyme polyphenol oxidase (PPO) was demonstrated as an anti-nutritive defense in tomato (Felton et al. 1989), with further investigations looking into proteinase inhibitors (Glassmire et al. 2024; Lin et al. 2020; Paudel et al. 2019). The well-mapped out defensive responses of tomato make it an ideal system to scrutinize the mechanism of GOX. Taken together, tomato is a system that has been studied intensively. It is a model system for biotic and abiotic stressors. Its genome has been sequenced for over a decade, and it has been used extensively in plant-insect interactions. Furthermore, the elicitation of plant defenses in this system via GOX makes it a desirable system to use when dissecting the mechanisms that GOX acts through.

We propose a variety of methods of investigation to use to test the proposed model. Since the model relies heavily upon hydrogen peroxide persistence and ROS-scavenging efficiency, a direct way to test the model is to quantify the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in plants that have different reactions to GOX (induced and suppressed responses) such as in the cultivated tomato and cotton (or N. attenuata). This could be accomplished by using feeding assays with insects (such as H. zea) or by mechanical damage with repeated applications of hydrogen peroxide. This should be coupled with investigations of the gene expression of ROS scavengers, as we predict that species/genotypes with more efficient scavenging will have a JA-pathway related response to GOX. Another method of investigation would be to investigate whether a plant such as the cultivated tomato responds to GOX with defense suppression if the ROS scavenging enzymes it has are impaired (this could be done using knockout plants). A final suggestion would be to see if improved ROS scavenging efficiency would lead to the opposite (a defense induction in a system where GOX usually causes suppression).

Conclusion and Future Directions

GOX is at the convergence of many areas of research such as plant-insect interactions, ecology, physiology etc. It is an enzyme that has been studied in many plant systems, with species-specific effects and unclear mechanisms of action. Although many models of GOX action have been proposed, none seem definitive. In this review, we propose a new model which aims to resolve many difficulties posed by previous models but needs further rigorous testing to validate.

The model system of tomato plants offers many advantages to investigate the mechanisms of GOX. Mainly, GOX has been shown to induce defenses in tomato, unlike other systems where GOX suppresses defenses. If the model proposed in this paper is correct, overcoming the H2O2 threshold should be able to push tomatoes from showing defense elicitation to defense suppression under GOX

Although this review has largely focused on the molecular mechanisms behind GOX, there are many other avenues of research still open to investigation. GOX is a widespread enzyme in Lepidoptera, and therefore it may play an important role in plant-insect interactions in the wild. Much of the knowledge accumulated about GOX comes from cultivated species (Musser et al. 2002; Musser et al. 2005; Tian et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2021). It would be useful to observe the reactions of wild plants to this enzyme to ascertain the ecological role it plays in plant-insect interactions. The sharply contrasting roles of GOX as an elicitor and an effector make it possible that it plays an important role in choosing host plants. There are many wild species of plants like tomato and tobacco available that make these investigations feasible.

In line with the ecological role that GOX may play, it may also offer insights into fields like induced defense theory. There has been a considerable amount of research on induced defenses (Lin et al. 2020; Paudel et al. 2019; Agrawal et al. 2014) and many papers on the theory behind their benefit and evolution (Agrawal 2005; Karban et al. 1997; Karban and Myers 1989). Authors have predicted that induced defenses are favored in environments with variable herbivory (Adler and Karban 1994) however measuring the costs of induced defenses has proven difficult (Brown 1988; Karban 1993). GOX research would add to our understanding of induced defenses because it modulates plant defenses. Studies that don’t appreciate this may be either over or underestimating the true range of induced defenses that a plant is capable of. This is especially pertinent because of the range of GOX in insects such as Lepidoptera (Eichenseer et al. 2010). Much of the earlier writing on the theory behind induced plant resistance focuses on plants. There does not seem to be as much attention paid to the complexity of the herbivore side of the interactions in terms of elicitors and effectors as many of the older papers predate the discovery of molecules like GOX.

In this review, we have proposed a new model for the mechanism of GOX action. Our new model builds upon previous work in several ways. While other previous authors have noted that ROS scavenging is likely important (Lin et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2023), we have made an important distinction. Oxidative damage can be harmful to plants (Larkindale and Knight 2002), making ROS scavenging a vitally important function. In our model, however, inefficient ROS scavenging instead leads to SA pathway activation. This is consistent with the observations of several studies that SA activation is dependent upon certain concentrations of H2O2 (Leon et al. 1995; Neuenschwander et al. 1995). We have also drawn attention to the fact that GOX may cause different signaling responses within a plant, since ROS scavenging may differ between leaves due to age. Several papers document differences in antioxidant and/or ROS scavenging abilities and/or transcripts between younger and older leaves (Casano et al. 1994; Cspregi et al. 2017; Dertinger et al. 2003; Li et al. 1995; Moustaka et al. 2015). It is also important to note that while we focus on SA pathway activation that SA activation and oxidative damage are not necessarily mutually exclusive. There is evidence that SA can inhibit ROS scavenging enzymes and increase hydrogen peroxide concentrations (Chen et al. 1993). However, it is important to note that Bi and colleagues (1997) found that even at a concentration of 1mM, SA was not enough to inhibit cotton foliar ROS scavengers like catalase in vitro, so there may be a level of system specificity in this regard as well. We have also taken systemic signaling into consideration, which to our knowledge only one study on GOX has addressed (Lin et al. 2020).

Another aspect of GOX research that has been largely neglected is the potential of GOX’s other product, gluconolactone. Although the paper that established GOX as an effector mentioned that gluconic acid itself when applied to leaf wounds caused a 29.3% reduction in nicotine content compared to a control consisting of damage and water (Musser et al. 2002), other studies have focused almost solely on the role of H2O2 in defense signaling. Gluconolactone is converted spontaneously into gluconic acid (Bentley and Neuberger 1949), and this may lead to a change in pH. This is important, as if too much accumulates there is a chance that this product of GOX may destabilize the enzyme (although the disruption in pH may also affect the functioning of plant proteins involved in defense responses such as PPO and ROS scavengers). More research should be conducted in this vein, as this aspect of possible interference is very pertinent to how long GOX may be effective in altering plant defense signaling. It is also important to note that certain microbes possess lactonases, which break down lactones (Brodie and Lipmann 1954). It would be informative to know if symbiotic plant microbes can disrupt GOX action through breaking down gluconolactone into gluconic acid.

Finally, although GOX likely plays an important role in plant-insect interactions it is only one piece of the puzzle. There are many other elicitors and effectors that insect herbivores possess. Likewise, there are many aspects of plant defense signaling that are still poorly understood. Studying these interactions will help us to begin to understand the rich complexity of the evolutionary arms race between plants and insects.

Funding Declaration

There was no funding for this paper.

References

- 100 Tomato Genome Sequencing Consortium, Aflitos S, Schijlen E, de Jong H, de Ridder D, Smit S, Finkers R, Wang J, Zhang G, Li N, et al. 2014. Exploring genetic variation in the tomato (Solanumsection Lycopersicon) clade by whole-genome sequencing. Plant J. 80(1):136–148. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Baki AA. 1991. Tolerance of tomato cultivars and selected germplasm to heat stress. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 116(6):1113–1116. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo FE, Smith P, Peiffer M, Helms A, Tooker J, Felton GW. 2019. Phytohormones in fall armyworm saliva modulate defense responses in plants. J Chem Ecol. 45(7):598–609. [CrossRef]

- Adler FR, Karban R. 1994. Defended fortresses or moving targets? Another model of inducible defenses inspired by military metaphors. Am Nat. 144(5):813–832. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal AA. 2005. Future directions in the study of induced plant responses to herbivory. Entomol Exp Appl. 115(1):97–105. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal AA, Hastings AP, Patrick ET, Knight AC. 2014. Specificity of herbivore-induced hormonal signaling and defensive traits in five closely related milkweeds (Asclepias spp.). J Chem Ecol. 40(7):717–729. [CrossRef]

- Asadi A, Ghadamyari M, Reza Hassan Sajedi, Jalal Jalali Sendi, Mehrdad Tabari. 2010. Biochemical characterization of midgut, salivary glands and haemolymph α-amylases of Naranga aenescens. Bulletin of insectology. 63(2):175–181.

- Bede JC, Musser RO, Felton GW, Korth KL. 2006. Caterpillar herbivory and salivary enzymes decrease transcript levels of Medicago truncatula genes encoding early enzymes in terpenoid biosynthesis.Plant Mol Biol. 60(4):519–531. [CrossRef]

- Bentley R, Neuberger A. 1949. The mechanism of the action of notatin. Biochem J. 45(5):584–590. [CrossRef]

- Bi G, Hu M, Fu L, Zhang X, Zuo J, Li J, Yang J, Zhou J-M. 2022. The cytosolic thiol peroxidasePRXIIB is an intracellular sensor for H2O2 that regulates plant immunity through a redox relay. Nat Plants. 8(10):1160–1175. [CrossRef]

- Bi JL, Felton GW. 1995. Foliar oxidative stress and insect herbivory: Primary compounds, secondary metabolites, and reactive oxygen species as components of induced resistance. J Chem Ecol. 21(10):1511–1530. [CrossRef]

- Bi JL, Murphy JB, Felton GW. 1997. Does salicylic acid act as a signal in cotton for induced resistanceto Helicoverpa zea? J Chem Ecol. 23(7):1805–1818. [CrossRef]

- Blanca J, Sanchez-Matarredona D, Ziarsolo P, Montero-Pau J, van der Knaap E, Díez MJ, Cañizares J. 2022. Haplotype analyses reveal novel insights into tomato history and domestication driven by long-distance migrations and latitudinal adaptations. Hortic Res. 9. [CrossRef]

- Block A, Christensen SA, Hunter CT, Alborn HT. 2018. Herbivore-derived fatty-acid amides elicit reactive oxygen species burst in plants. J Exp Bot. 69(5):1235–1245. [CrossRef]

- Brodie AF, Lipmann F. 1955. Identification of a gluconolactonase. J Biol Chem. 212(2):677–685. [CrossRef]

- Brown DG. 1988. The cost of plant defense: an experimental analysis with inducible proteinase inhibitors in tomato. Oecologia. 76(3):467–470. [CrossRef]

- Cao L, Karapetyan S, Yoo H, Chen T, Mwimba M, Zhang X, Dong X. 2024. H2O2 sulfenylates CHE, linking local infection to the establishment of systemic acquired resistance. Science. 385(6714):1211–1217. [CrossRef]

- Cao X, Jiang F, Wang X, Zang Y, Wu Z. 2015. Comprehensive evaluation and screening for chilling-tolerance in tomato lines at the seedling stage. Euphytica. 205(2):569–584. [CrossRef]

- Casano LM, Martin M, Sabater B. 1994. Sensitivity of superoxide dismutase transcript levels and activities to oxidative stress is lower in mature-senescent than in young barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 106(3):1033–1039. [CrossRef]

- Cavener DR. 1992. GMC oxidoreductases. A newly defined family of homologous proteins with diverse catalytic activities. J Mol Biol. 223(3):811–814. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Silva H, Klessig DF. 1993. Active oxygen species in the induction of plant systemic acquired resistance by salicylic acid. Science. 262(5141):1883–1886. [CrossRef]

- Conti V, Mareri L, Faleri C, Nepi M, Romi M, Cai G, Cantini C. 2019. Drought stress affects the response of Italian local tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in a genotype-dependent manner. Plants. 8(9):336. [CrossRef]

- Csepregi K, Coffey A, Cunningham N, Prinsen E, Hideg É, Jansen MAK. 2017. Developmental age and UV-B exposure co-determine antioxidant capacity and flavonol accumulation in Arabidopsis leaves. Environ Exp Bot. 140:19–25. [CrossRef]

- Dat JF, Lopez-Delgado H, Foyer CH, Scott IM. 1998. Parallel changes in H2O2 and catalase during thermotolerance induced by salicylic acid or heat acclimation in mustard seedlings. Plant Physiol. 116(4):1351–1357. [CrossRef]

- Dat JF, Pellinen R, Beeckman T, Van De Cotte B, Langebartels C, Kangasjärvi J, Inzé D, Van Breusegem F.2003. Changes in hydrogen peroxide homeostasis trigger an active cell death process in tobacco: changes in H2O2homeostasis: triggering tobacco active cell death. Plant J. 33(4):621–632. [CrossRef]

- Dertinger U, Schaz U, Schulze E-D. 2003. Age-dependence of the antioxidative system in tobacco with enhanced glutathione reductase activity or senescence-induced production of cytokinins. Physiol Plant. 119(1):19–29. [CrossRef]

- Diezel C, von Dahl CC, Gaquerel E, Baldwin IT. 2009. Different lepidopteran elicitors account for cross-talk in herbivory-induced phytohormone signaling. Plant Physiol. 150(3):1576–1586. [CrossRef]

- Doares SH, Narvaez-Vasquez J, Conconi A, Ryan CA. 1995. Salicylic acid inhibits synthesis of proteinase inhibitors in tomato leaves induced by systemin and jasmonic acid. Plant Physiol. 108(4):1741–1746. [CrossRef]

- Doherty HM, Selvendran RR, Bowles DJ. 1988. The wound response of tomato plants can be inhibited by aspirin and related hydroxy-benzoic acids. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 33(3):377–384. [CrossRef]

- Dussourd DE, Denno RF. 1991. Deactivation of plant defense: Correspondence between insect behavior and secretory canal architecture. Ecology. 72(4):1383–1396. [CrossRef]

- Dussourd DE. 1999. Behavioral Sabotage of Plant Defense: Do Vein Cuts and Trenches Reduce Insect.

- Exposure to Exudate? Journal of Insect Behavior. 12(4):501–515. [CrossRef]

- Eichenseer H, Mathews MC, Bi JL, Murphy JB, Felton GW. 1999. Salivary glucose oxidase: multifunctional roles for helicoverpa zea? Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 42(1):99–109.

- Eichenseer H, Mathews MC, Powell JS, Felton GW. 2010. Survey of a salivary effector in caterpillars: glucose oxidase variation and correlation with host range. J Chem Ecol. 36(8):885–897. [CrossRef]

- Eichenseer H, Murphy JB, Felton GW. 2002. Sequestration of host plant carotenoids in the larval tissues of Helicoverpa zea. J Insect Physiol. 48(3):311–318. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2023. Agricultural production statistics 2000–2022. FAOSTAT Analytical Briefs, No. 79. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Farmer EE, Ryan CA. 1990. Interplant communication: airborne methyl jasmonate induces synthesis of proteinase inhibitors in plant leaves. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 87(19):7713–7716. [CrossRef]

- Felton GW, Donato K, Del Vecchio RJ, Duffey SS. 1989. Activation of plant foliar oxidases by insect feeding reduces nutritive quality of foliage for noctuid herbivores. J Chem Ecol. 15(12):2667–2694. [CrossRef]

- Glassmire AE, Hauri KC, Turner DB, Zehr LN, Sugimoto K, Howe GA, Wetzel WC. 2024. The frequency and chemical phenotype of neighboring plants determine the effects of intraspecific plant diversity. Ecology. 105(9):e4392. [CrossRef]

- Haque MS, Husna MT, Uddin MN, Hossain MA, Sarwar AKMG, Ali OM, Abdel Latef AAH, Hossain A.2021. Heat stress at early reproductive stage differentially alters several physiological and biochemical traits of three tomato cultivars. Horticulturae. 7(10):330. [CrossRef]

- Heller A, Ulstrup J. 2021. Detlev Müller’s discovery of glucose oxidase in 1925. Anal Chem. 93(18):7148–7149. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y-H, Leung DWM, Kang L, Wang C-Z. 2008. Diet factors responsible for the change of the glucose oxidase activity in labial salivary glands of Helicoverpa armigera. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 68(2):113–121. [CrossRef]

- Hulley PE. 1988. Caterpillar attacks plant mechanical defence by mowing trichomes before feeding. Ecol Entomol. 13(2):239–241. [CrossRef]

- Jones AC, Felton GW, Tumlinson JH. 2022. The dual function of elicitors and effectors from insects: reviewing the “arms race” against plant defenses. Plant Mol Biol. 109(4–5):427–445. [CrossRef]

- Jones AC, Lin P-A, Peiffer M, Felton G. 2023. Caterpillar salivary glucose oxidase decreases green leaf volatile emission and increases terpene emission from maize. J Chem Ecol. 49(9–10):518–527. [CrossRef]

- Kallure GS, Kumari A, Shinde BA, Giri AP. 2022. Characterized constituents of insect herbivore oral secretions and their influence on the regulation of plant defenses. Phytochemistry. 193(113008):113008. [CrossRef]

- Karban R. 1993. Costs and benefits of induced resistance and plant density for a native shrub, Gossypium thurberi. Ecology. 74(1):9–19. [CrossRef]

- Karban R, Agrawal AA, Mangel M. 1997. The benefits of induced defenses against herbivores. Ecology. 78(5):1351. [CrossRef]

- Karban R, Myers JH. 1989. Induced plant responses to herbivory. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 20(1):331–348. [CrossRef]

- Kariyat RR, Hardison SB, Ryan AB, Stephenson AG, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. 2018. Leaf trichomes affect caterpillar feeding in an instar-specific manner. Commun Integr Biol. 11(3):1–6. [CrossRef]

- Karssemeijer PN, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, van Loon J, Dicke M. 2020. Foliar herbivory by caterpillars and aphids differentially affects phytohormonal signalling in roots and plant defence to a root herbivore: Foliar herbivory affects roots and root herbivores. Plant Cell Environ. 43(3):775–786. [CrossRef]

- Larkindale J, Knight MR. 2002. Protection against heat stress-induced oxidative damage in Arabidopsis involves calcium, abscisic acid, ethylene, and salicylic acid. Plant Physiol. 128(2):682–695. [CrossRef]

- Leon J, Lawton MA, Raskin I. 1995. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates salicylic acid biosynthesis in tobacco.Plant Physiol. 108(4):1673–1678. [CrossRef]

- Levine A, Tenhaken R, Dixon R, Lamb C. 1994. H2O2 from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell. 79(4):583–593. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wu Z, He G. 1995. Effects of low temperature and physiological age on superoxide dismutase in water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes Solms). Aquat Bot. 50(2):193–200. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Yi H. 2012. Effect of sulfur dioxide on ROS production, gene expression and antioxidant enzyme activity in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 58:46–53. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Xie Q-G, Smith-Becker J, Navarre DA, Kaloshian I. 2006. Mi-1-Mediated aphid resistance involves salicylic acid and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 19(6):655–664. [CrossRef]

- Lin P-A, Chen Y, Chaverra-Rodriguez D, Heu CC, Zainuddin NB, Sidhu JS, Peiffer M, Tan C-W, Helms A, Kim D, et al. 2021. Silencing the alarm: an insect salivary enzyme closes plant stomata and inhibits volatile release. New Phytol. 230(2):793–803. [CrossRef]

- Lin P-A, Peiffer M, Felton GW. 2020. Induction of defensive proteins in Solanaceae by salivary glucose oxidase of Helicoverpa zea caterpillars and consequences for larval performance. Arthropod Plant Interact. 14(3):317–325. [CrossRef]

- Lin T, Zhu G, Zhang J, Xu X, Yu Q, Zheng Z, Zhang Z, Lun Y, Li S, Wang X, et al. 2014. Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat Genet. 46(11):1220–1226. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, He J, Fu W. 2005. Highly controlled nest homeostasis of honey bees helps deactivate phenolics in nectar. Sci Nat. 92(6):297–299. [CrossRef]

- López-Uribe MM, Fitzgerald A, Simone-Finstrom M. 2017. Inducible versus constitutive social immunity: examining effects of colony infection on glucose oxidase and defensin-1 production in honeybees. R Soc Open Sci. 4(5):170224. [CrossRef]

- Louis J, Peiffer M, Ray S, Luthe DS, Felton GW. 2013. Host-specific salivary elicitor(s) of European corn borer induce defenses in tomato and maize. New Phytol. 199(1):66–73. [CrossRef]

- McCloud ES, Baldwin IT. 1997. Herbivory and caterpillar regurgitants amplify the wound-induced increases in jasmonic acid but not nicotine in Nicotiana sylvestris. Planta. 203(4):430–435. [CrossRef]

- Moran J, Becana M, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frechilla S, Klucas R, Aparicio-Tejo P. 1994. Drought induces oxidative stress in pea plants. Planta. 194(3). [CrossRef]

- Moustaka J, Tanou G, Adamakis I-D, Eleftheriou EP, Moustakas M. 2015. Leaf age-dependent photoprotective and antioxidative response mechanisms to paraquat-induced oxidative stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 16(6):13989–14006. [CrossRef]

- Musser RO, Cipollini DF, Hum-Musser SM, Williams SA, Brown JK, Felton GW. 2005. Evidence that the caterpillar salivary enzyme glucose oxidase provides herbivore offense in solanaceous plants. ArchInsect Biochem Physiol. 58(2):128–137. [CrossRef]

- Musser RO, Hum-Musser SM, Eichenseer H, Peiffer M, Ervin G, Murphy JB, Felton GW. 2002. Herbivory: caterpillar saliva beats plant defences: Herbivory. Nature. 416(6881):599–600. [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander U, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Uknes S, Kessmann H, Ryals J. 1995. Is hydrogen peroxide a second messenger of salicylic acid in systemic acquired resistance? Plant J. 8(2):227–233. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Cárdenas ML, Narváez-Vásquez J, Ryan CA. 2001. Hydrogen peroxide acts as a second messenger for the induction of defense genes in tomato plants in response to wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell. 13(1):179–191. [CrossRef]

- Paudel S, Lin P-A, Foolad MR, Ali JG, Rajotte EG, Felton GW. 2019. Induced plant defenses against herbivory in cultivated and wild tomato. J Chem Ecol. 45(8):693–707. [CrossRef]

- Paudel S, Lin P-A, Hoover K, Felton GW, Rajotte EG. 2020. Asymmetric responses to climate change: Temperature differentially alters herbivore salivary elicitor and host plant responses to herbivory. J Chem Ecol. 46(9):891–905. [CrossRef]

- Pawar SV, Paranjape SM, Kalowsky GK, Peiffer M, McCartney N, Ali JG, Felton GW. 2025. Tomato defenses under stress: The impact of salinity on direct defenses against insect herbivores. Plant Cell Environ. [CrossRef]

- Pena-Cortes H, Albrecht T, Prat S, Weiler E, Willmitzer L. 1993. Aspirin prevents wound-induced gene expression in tomato leaves by blocking jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Planta. 191(1). [CrossRef]

- Prasad TK, Anderson MD, Martin BA, Stewart CR. 1994. Evidence for chilling-induced oxidative stress in maize seedlings and a regulatory role for hydrogen peroxide. Plant Cell. 6(1):65–74. [CrossRef]

- Razifard H, Ramos A, Della Valle AL, Bodary C, Goetz E, Manser EJ, Li X, Zhang L, Visa S, Tieman D,et al. 2020. Genomic evidence for complex domestication history of the cultivated tomato in Latin America. Mol Biol Evol. 37(4):1118–1132. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Vega LJ, Acevedo FE, Felton GW. 2017. Genomics of Lepidoptera saliva reveals function in herbivory. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 19:61–69. [CrossRef]

- Selote DS, Khanna-Chopra R. 2004. Drought-induced spikelet sterility is associated with an inefficient antioxidant defence in rice panicles. Physiol Plant. 121(3):462–471. [CrossRef]

- Snyder MJ, Hsu EL, Feyereisen R. 1993. Induction of cytochrome P-450 activities by nicotine in the tobacco hornworm,Manduca sexta. J Chem Ecol. 19(12):2903–2916. [CrossRef]

- Snyder MJ, Walding JK, Feyereisen R. 1994. Metabolic fate of the allelochemical nicotine in the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 24(8):837–846. [CrossRef]

- Sperdouli I, Andreadis SS, Adamakis I-DS, Moustaka J, Koutsogeorgiou EI, Moustakas M. 2022. Reactive oxygen species initiate defence responses of potato photosystem II to sap-sucking insect feeding. Insects. 13(5):409. doi:10.3390/insects13050409. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/insects13050409. Summermatter K, Sticher L, Metraux JP. 1995. Systemic Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana Infected and Challenged with Pseudomonas syringae pv syringae. Plant Physiol. 108(4):1379–1385. [CrossRef]

- Tan C-W, Peiffer M, Hoover K, Rosa C, Acevedo FE, Felton GW. 2018. Symbiotic polydnavirus of a parasite manipulates caterpillar and plant immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 115(20):5199–5204. [CrossRef]

- Thaler JS, Agrawal AA, Halitschke R. 2010. Salicylate-mediated interactions between pathogens and herbivores. Ecology. 91(4):1075–1082. [CrossRef]

- Thaler JS, Stout MJ, Karban R, Duffey SS. 1996. Exogenous jasmonates simulate insect wounding in tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum) in the laboratory and field. J Chem Ecol. 22(10):1767–1781. [CrossRef]

- Tian D, Peiffer M, Shoemaker E, Tooker J, Haubruge E, Francis F, Luthe DS, Felton GW. 2012. Salivary glucose oxidase from caterpillars mediates the induction of rapid and delayed-induced defenses in the tomato plant. PLoS One. 7(4):e36168. [CrossRef]

- Tomato Genome Consortium. 2012. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 485(7400):635–641. [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele S, Vanderauwera S, Vuylsteke M, Rombauts S, Langebartels C, Seidlitz HK, Zabeau M, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, Van Breusegem F. 2004. Catalase deficiency drastically affects gene expression induced by high light in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 39(1):45–58. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Peiffer M, Hoover K, Rosa C, Zeng R, Felton GW. 2017. Helicoverpa zea gut-associated bacteria indirectly induce defenses in tomato by triggering a salivary elicitor(s). New Phytol. 214(3):1294–1306. [CrossRef]

- Weech M-H, Chapleau M, Pan L, Ide C, Bede JC. 2008. Caterpillar saliva interferes with induced Arabidopsis thaliana defence responses via the systemic acquired resistance pathway. J Exp Bot. 59(9):2437–2448. [CrossRef]

- White JW Jr, Subers MH, Schepartz AI. 1963. The identification of inhibine, the antibacterial factor in honey, as hydrogen peroxide and its origin in a honey glucose-oxidase system. Biochim Biophys Acta.73(1):57–70. [CrossRef]

- Wu F, Chi Y, Jiang Z, Xu Y, Xie L, Huang F, Wan D, Ni J, Yuan F, Wu X, et al. 2020. Hydrogen peroxide sensor HPCA1 is an LRR receptor kinase in Arabidopsis. Nature. 578(7796):577–581. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Jing X, Dong R, Zhou L, Xu X, Dong Y, Zhang L, Zheng L, Lai Y, Chen Y, et al. 2023. Glucose oxidase of a Crucifer-specialized insect: A potential role in suppressing plant defense via modulating antagonistic plant hormones. J Agric Food Chem. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Wang J, Li S, Kakan X, Zhou Y, Miao Y, Wang F, Qin H, Huang R. 2019. Ascorbic acid integrates the antagonistic modulation of ethylene and abscisic acid in the accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol. 179(4):1861–1875. [CrossRef]

- Zhou R, Yu X, Ottosen C-O, Rosenqvist E, Zhao L, Wang Y, Yu W, Zhao T, Wu Z. 2017. Drought stress had a predominant effect over heat stress on three tomato cultivars subjected to combined stress. BMCPlant Biol. 17(1):24. [CrossRef]

- Zong N, Wang C. 2004. Induction of nicotine in tobacco by herbivory and its relation to glucose oxidase activity in the labial gland of three noctuid caterpillars. Chin Sci Bull. 49(15):1596–1601. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).