Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical Screening

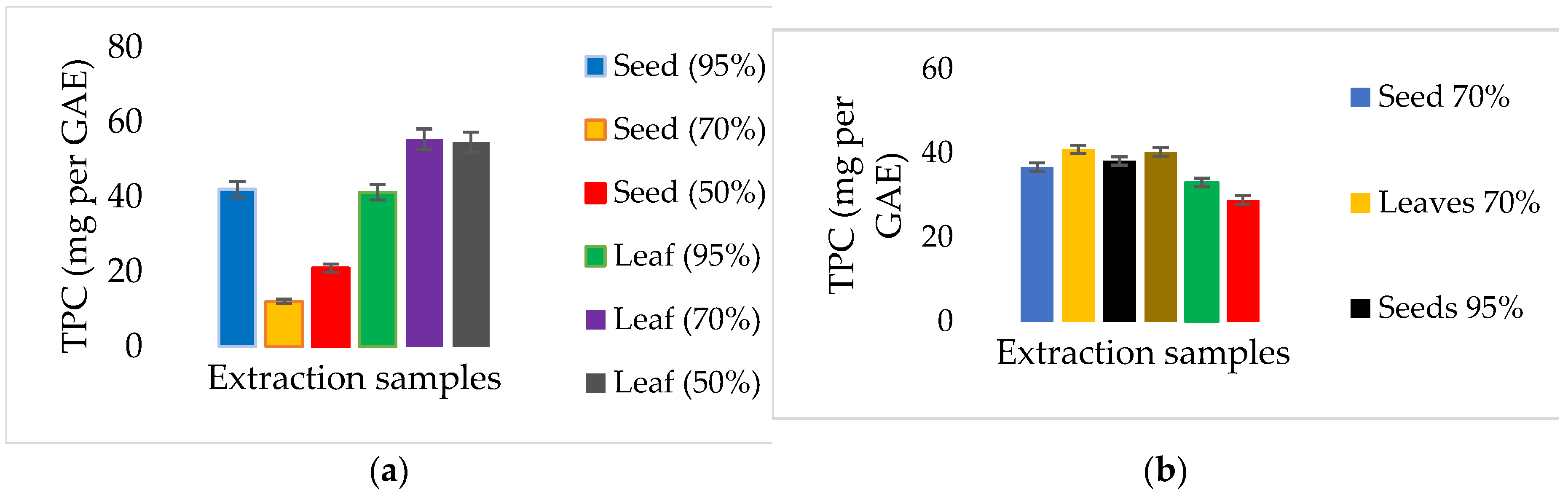

3.2. Total Phenolic Compounds

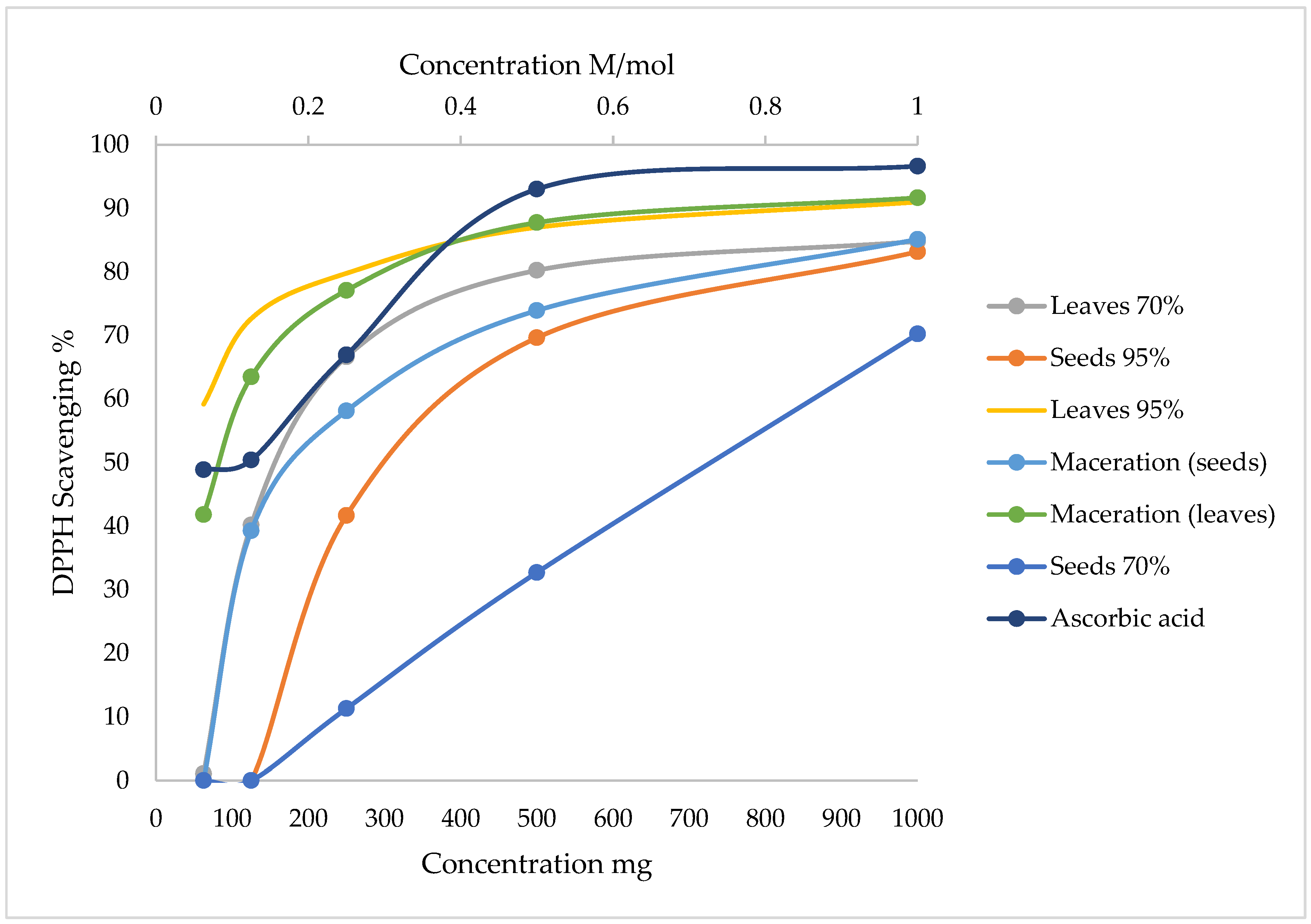

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

3.4. Yoghurt Analysis

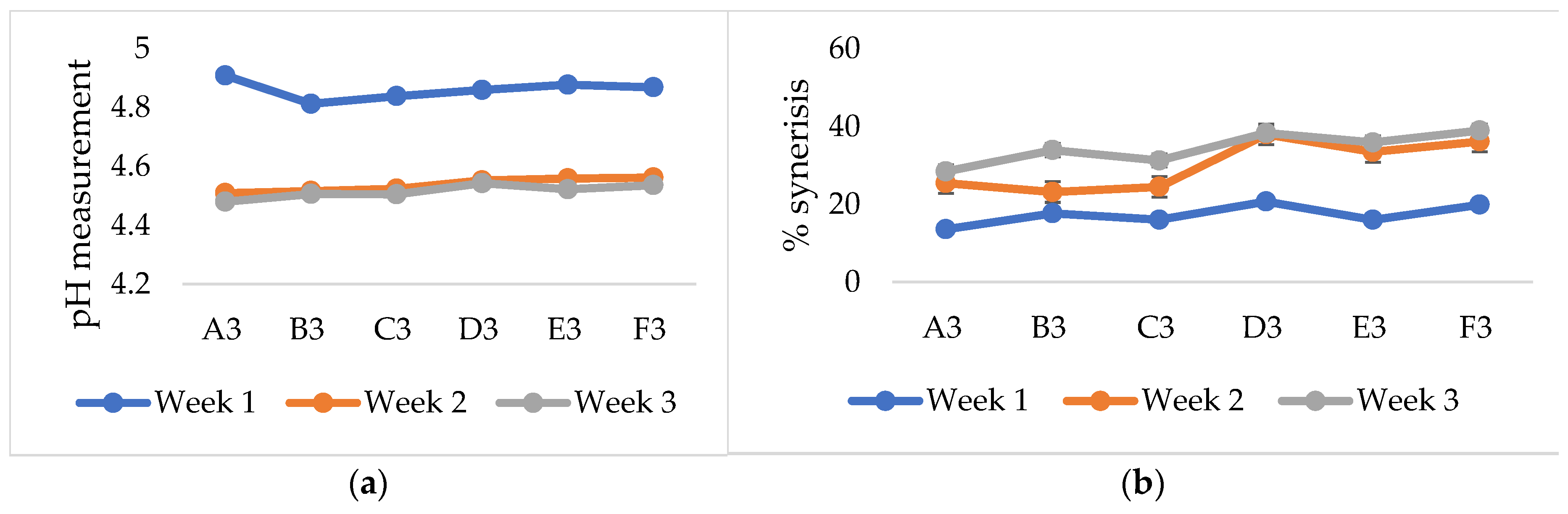

3.4.1. Yoghurt pH

3.4.2. Syneresis

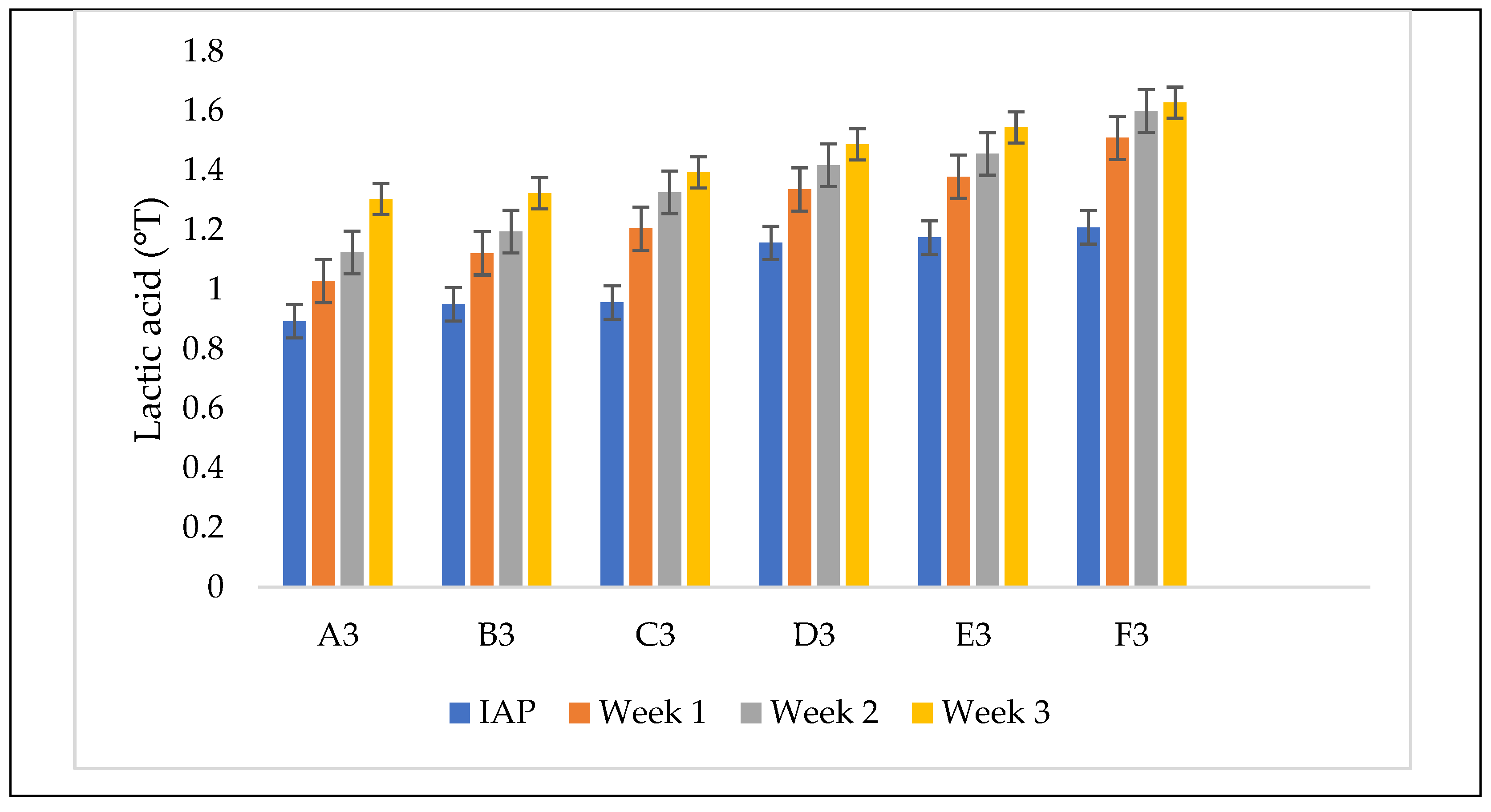

3.4.3. Titratable Acidity

3.4.6. Antioxidant Activity of the Fortified Yoghurts

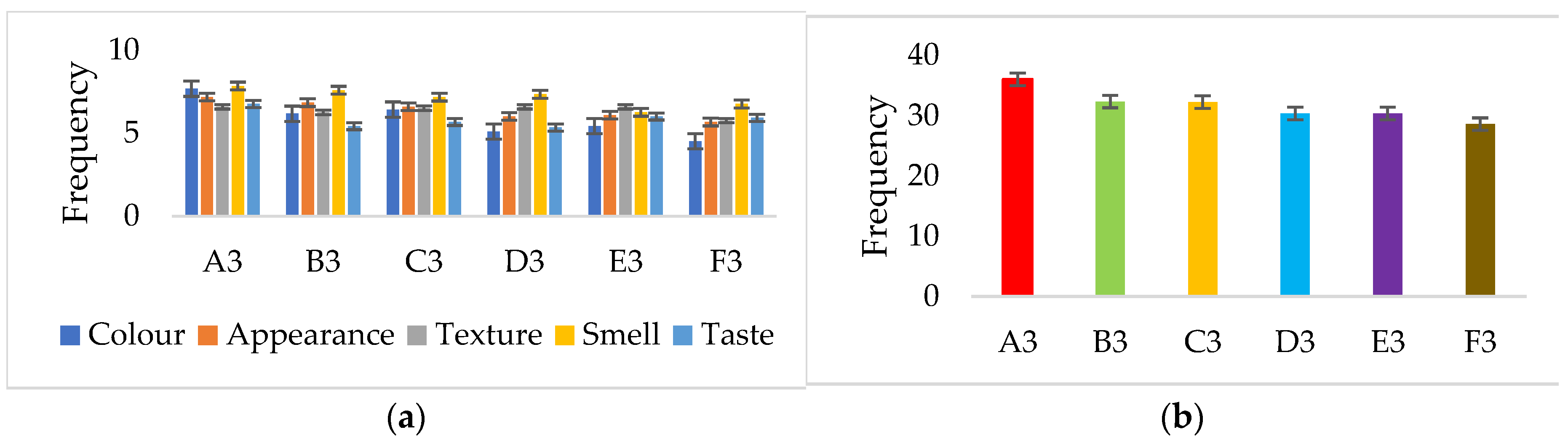

3.4.7. Organoleptic Properties of the Produced Yoghurts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPC | Total Phenolic Content |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalent |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-Picryl-Hydrazyl |

| AOA | Antiopxidant Activity |

References

- Grochowicz, J.; Fabisiak, A.; Ekielski, A. Importance of Physical and Functional Properties of Foods Targeted to Seniors. Journal of Future Foods 2021, 1, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C. Functional Foods: What Are the Benefits? Br J Community Nurs 2009, 14, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A.; Soleimani, T. Improvement of Artemisinin Production by Different Biotic Elicitors In Artemisia Annua by Elicitation–Infiltration Method. Banats J Biotechnol 2016, VII, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.; Joseph Kamal, S.W.; Bajrang Chole, P.; Dayal, D.; Chaubey, K.K.; Pal, A.K.; Xavier, J.; Manjunath, B.T.; Bachheti, R.K. Functional Foods: Exploring the Health Benefits of Bioactive Compounds from Plant and Animal Sources. J Food Qual 2023, 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Lan, Q.; Li, M.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Lin, D.; Qin, W.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Protein Glycosylation: A Promising Way to Modify the Functional Properties and Extend the Application in Food System. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 2506–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Saeed, F.; Anjum, F.M.; Afzaal, M.; Tufail, T.; Bashir, M.S.; Ishtiaq, A.; Hussain, S.; Suleria, H.A.R. Natural Polyphenols: An Overview. Int J Food Prop 2017, 20, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, M.M.; Quispe, C.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Tutuncu, S.; Aydar, E.F.; Topkaya, C.; Mertdinc, Z.; Ozcelik, B.; Aital, M.; et al. A Review of Recent Studies on the Antioxidant and Anti-Infectious Properties of Senna Plants. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Md.M.; Al-Noman, Md.A.; Khatun, S.; Alam, R.; Shetu, M.H.; Talukder, Md.E.K.; Imon, R.R.; Biswas, Y.; Anis-Ul-Haque, K.M.; Uddin, M.J.; et al. Senna Tora (L.) Roxb. Leaves Are the Sources of Bioactive Molecules Against Oxidant, Inflammation, and Bacterial Infection: An in Vitro, in Vivo, and in Silico Study. SSRN Electronic Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T.T.H.; Anh, L.N.; Trung, N.Q.; Quang, T.H.; Anh, D.H.; Cuong, N.X.; Nam, N.H.; Van Minh, C. Cytotoxic Phenolic Glycosides from the Seeds of Senna Tora. Phytochem Lett 2021, 45, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongchai, S.; Chokchaitaweesuk, C.; Kongdang, P.; Chomdej, S.; Buddhachat, K. In Vitro Chondroprotective Potential of Senna Alata and Senna Tora in Porcine Cartilage Explants and Their Species Differentiation by DNA Barcoding-High Resolution Melting (Bar-HRM) Analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimaran, S.; Venkatachalam, K.; Krishnan, G.; Govindasamy, A.; Sakthivel, V. Antimicrobial Activity and Phytochemical Screening of Leaf Extracts of Senna Tora (L.) Roxb. International journal of multidisciplinary advanced scientific research and innovation 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnadurai, P.; Stojšin, D.; Liu, K.; Frierdich, G.E.; Glenn, K.C.; Geng, T.; Schapaugh, A.; Huang, K.; Deffenbaugh, A.E.; Liu, Z.L.; et al. Variability of CP4 EPSPS Expression in Genetically Engineered Soybean (Glycine Max L. Merrill). Transgenic Res 2018, 27, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joung, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Ha, Y.S.; Shin, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, N.S. Enhanced Microbial, Functional and Sensory Properties of Herbal Yogurt Fermented with Korean Traditional Plant Extracts. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour 2016, 36, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Hwang, H.; Selvaraj, B.; Lee, J.W.J.H.; Park, W.; Ryu, S.M.; Lee, D.; Park, J.S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.W.J.H.; et al. Phenolic Constituents Isolated from Senna Tora Sprouts and Their Neuroprotective Effects against Glutamate-Induced Oxidative Stress in HT22 and R28 Cells. Bioorg Chem 2021, 114, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysin, A.P.; Egorov, A.R.; Godzishevskaya, A.A.; Kirichuk, A.A.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kritchenkov, A.S. Biologically Active Supplements Affecting Producer Microorganisms in Food Biotechnology: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakouli, K.; Mpesios, A.; Kouretas, D.; Petrotos, K.; Mitsagga, C.; Giavasis, I.; Jamurtas, A.Z. The Effects of an Olive Fruit Polyphenol-Enriched Yogurt on Body Composition, Blood Redox Status, Physiological and Metabolic Parameters and Yogurt Microflora. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanashkina, T. V.; Piankova, A.F.; Semenyuta, A.A.; Kantemirov, A. V.; Prikhodko, Y. V. Buckwheat Grass Tea Beverages: Row Materials, Production Methods, and Biological Activity. Food Processing: Techniques and Technology 2021, 51, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, M.; Ozden, M.; Vardin, H.; Turkoglu, H. Phenolic Fortification of Yogurt Using Grape and Callus Extracts. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Determination of Antioxidants by DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity and Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis of Ficus Religiosa. Molecules 2022, 27, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, R.; Bansal, G.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, A. Estimation of Total Phenols and Flavonoids in Extracts of Actaea Spicata Roots and Antioxidant Activity Studies.

- GOST 31450-2013: Drinking milk. Technical Conditions. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_31450-2013 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- GOST 31981-2013: Yoghurt. General Technical Conditions. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_31981-2013 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Palmeri, R.; Parafati, L.; Trippa, D.; Siracusa, L.; Arena, E.; Restuccia, C.; Fallico, B. Addition of Olive Leaf Extract (OLE) for Producing Fortified Fresh Pasteurized Milk with an Extended Shelf Life. Antioxidants 2019, Vol. 8, Page 255 2019, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 31976-2012: Yoghurts and Yoghurt Products. Potentiometric Method for Determining Titratable Acidity. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_31976-2012 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Oliveira, C. de; Lopes-Júnior, L.C.; Sousa, C.P. de Microbiological Quality of Pasteurized Human Milk from a Milk Bank of São Paulo. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 2022, 35, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.M.; Santos, L. Incorporation of Phenolic Extracts from Different By-Products in Yoghurts to Create Fortified and Sustainable Foods. Food Biosci 2023, 51, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST R 51331-99: Yoghurt. General Technical Conditions. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_Р_51331-99 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Halal, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Impact of In-Vitro Gastro-Pancreatic Digestion on Polyphenols and Cinnamaldehyde Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Activity in Stirred Cinnamon-Fortified Yogurt. LWT 2018, 89, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST ISO 11036-2017: Organoleptic Analysis. Methodology. Characteristics of Structure. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_ISO_11036-2017 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- GOST ISO 5492-2014: Organoleptic Analysis. Dictionary. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_ISO_5492-2014 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- GOST ISO 8586-2015: Organoleptic Analysis. General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Supervision of Selected Testers and Expert Testers. Available online: https://standartgost.ru/g/ГОСТ_ISO_8586-2015 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Joung, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Ha, Y.S.; Shin, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, N.S. Enhanced Microbial, Functional and Sensory Properties of Herbal Yogurt Fermented with Korean Traditional Plant Extracts. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour 2016, 36, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngombe, N.K.; Ngolo, C.N.; Kialengila, D.M.; Wamba, A.L.; Mungisthi, P.M.; Tshibangu, P.T.; Dibungi, P.K.T.; Kantola, P.T.; Kapepula, P.M.; Ngombe, N.K.; et al. Cellular Antioxidant Activity and Peroxidase Inhibition of Infusions from Different Aerial Parts of Cassia Occidentalis. J Biosci Med (Irvine) 2019, 7, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.P.; Arya, V.; Yadav, S.; Panghal, M.; Kumar, S.; Dhankhar, S. Cassia Occidentalis L.: A Review on Its Ethnobotany, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile. Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajarajeswari, B.; Kumar, P. Comparative Evaluation of Phytochemicals, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Efficiency of Cassia occidentalis and Pithecellobium dulce Leaves Extract. Journal of Hunan University(Natural Sciences) 2021, 48, 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Balarabe, S.; Aliyu, B.S.; Muhammad, H.; Nafisa, M.A.; Namadina, M.M. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and Fourier Transformed Infrared Analysis of Senna occidentalis Root. Nigerian Journal of Botany 2020, 33, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gali Adamu Ishaku; Abudulhamid Abdulrahman Arabo; Adebiyi Adedayo; Useh Mercy Uwem; Etuk-Udo Godwin Physicochemical Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Senna occidentalis Linn. Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Sciences 2016, 6, 9–18.

- Mandal, A.; Sarkar, B.; Mandal, S.; Vithanage, M.; Patra, A.K.; Manna, M.C. Impact of Agrochemicals on Soil Health. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 161–187. [Google Scholar]

- Javad, S. Microwave Assisted Extraction of Phytochemicals from Bark of Cassia occidentalis L. Pure and Applied Biology 2016, 5, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine C; Abdulrahman BS Comparative Evaluation of the Proximate Composition and Anti-Nutritive Components of Tropical Sickle Pod (Senna obtusifolia) and Coffee Senna (Senna occidentalis) Seed Meals Indigenous to Mubi Area of Adamawa State Nigeria. Explore International Research Journal Consortium www.irjcjournals.org 2014, 3, 2319–4421.

- Manikandaselvi, S.; Vadivel, V.; Brindha, P. Studies on Physicochemical and Nutritional Properties of Aerial Parts of Cassia Occidentalis L. J Food Drug Anal 2016, 24, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-W.; Lin, L.-G.; Ye, W.-C. Techniques for Extraction and Isolation of Natural Products: A Comprehensive Review. Chin Med 2018, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryal, S.; Baniya, M.K.; Danekhu, K.; Kunwar, P.; Gurung, R.; Koirala, N. Total Phenolic Content, Flavonoid Content and Antioxidant Potential of Wild Vegetables from Western Nepal. Plants 2019, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.V.; Jain, J.; Mishra, A.K. Evaluation of Anticonvulsant and Antioxidant Activity of Senna Occidentalis Seeds Extracts. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics 2019, 9, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushotham, K.; Nandeeshwar, P.; Srikanth, I.; Ramanjaneyulu, K.; Himabindhu, J. Phytochemical Screening and In-Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Senna occidentalis. Res J Pharm Technol 2019, 12, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, L.A.; Morr, C. V. Improved Acid, Flavor and Volatile Compound Production in a High Protein and Fiber Soymilk Yogurt-like Product. J Food Sci 1996, 61, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeneke, C.A.; Aryana, K.J. Effect of Folic Acid Fortification on the Characteristics of Lemon Yogurt. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2008, 41, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, Ö.; Mogol, B.A.; Gökmen, V. Syneresis and Rheological Behaviors of Set Yogurt Containing Green Tea and Green Coffee Powders. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, K.J.; Troukhanova, N. V.; Lynn, P.Y. Nature of Polyphenol-Protein Interactions. J Agric Food Chem 1996, 44, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Jin, H.Y.; Yang, H.S.; Lee, S.C.; Huh, C.K. Quality and Storage Characteristics of Yogurt Containing Lacobacillus Sakei ALI033 and Cinnamon Ethanol Extract. J Anim Sci Technol 2016, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makinde, F.M.; Afolabi, M.O.; Ajayi, O.A.; Olatunji, O.M.; Eze, E.E. Effect of Selected Plant Extracts on Phytochemical, Antioxidant, Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Yoghurt. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2023, 1219, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Hwang, E.S. Quality Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity of Yogurt Supplemented with Aronia (Aronia Melanocarpa) Juice. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2016, 21, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeon, S.J.; Hong, G.E.; Kim, C.K.; Park, W.J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, C.H. Effects of Yogurt Containing Fermented Pepper Juice on the Body Fat and Cholesterol Level in High Fat and High Cholesterol Diet Fed Rat. Food Sci Anim Resour 2015, 35, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Sample | Antioxidant activity |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Seeds (95%) | 63.85 ± 0.64 |

| B1 | Seeds (70%) | 73.90 ± 3.33 |

| C1 | Seeds (50%) | 59.17 ± 1.02 |

| D1 | Leaves (95%) | 75.84 ± 0.44 |

| E1 | Leaves (70%) | 84.09 ± 0.53 |

| F1 | Leaves (50%) | 68.20 ± 2.28 |

| Control | Ascorbic acid | 93.57 ± 0.16 |

| Yogurt | First week AOA (%) | Third week AOA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A3 | 44.19 | 45.86 |

| B3 | 48.25 | 46.16 |

| C3 | 50.08 | 47.29 |

| D3 | 53.05 | 46.88 |

| E3 | 55.51 | 48.51 |

| F3 | 54.93 | 49.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).