1. Introduction

Yoghurts are dairy products made by fermenting cows’ milk in the presence of lactic acid bacteria such as

Lactobacillus bulgaricus and

Streptococcus thermophilus [

1]. The scarcity and high cost of cows’ milk, coupled with the problems of lactose intolerance that affect around 70% of the worlds’ population [

2], have led researchers in the field of food science to develop plant-based yoghurts. Numerous plant-based yoghurts have since been developed from Bambara seed [

3], soybeans [

4], coconut cream and modified maize starch or Cashew “milk” and tapioca starch [

5]. Yoghurts made from plant are cheaper and have considerable nutritional and therapeutic potential. Tiger nuts, also known as yellow nutsedge is one of the most under-utilised plant resources in Africa, yet it is rich in amino acids [

6], has high levels of essential fatty acids [

7], dietary fibres, vitamins, minerals [

8] and phytochemicals such as phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids and saponins [

9]. Recent studies have demonstrated the biological effects of tigernuts, such as anti-diabetic, cholesterol-lowering, hepatoprotective, aphrodisiac [

10], antibacterial and galactogenic [

11]. In Cameroon, tiger nuts are processed locally into milk and then into yoghurt in small production units using the traditional method of extracting milk from seeds that have been soaked for at least 24 hours. This sector is slow to expand because of the sensory qualities of the yoghurts produced, which are not always universally appreciated by consumers. Numerous studies have shown the impact that pre-treatment methods (soaking, sprouting, drying, boiling and roasting) of vegetable products could have on the quality of the products resulting from their processing. Previous studies have shown the effect of roasting on increasing proteins, total ash, crude fibres and lipids. Like roasting, boiling, germination and drying of plant products significantly reduce the content of anti-nutritional factors and have a positive effect on the sensory characteristics of the final product [

12]. Pretreatment of seeds could therefore be beneficial, as it will boost the nutritional and sensory value of our yoghurts and reduce their levels of anti-nutritional factors. Fermentation of tiger nut milk is of particular interest because of the prospects for generating lactose-free, yoghurt-like products with improved microbial stability and extended shelf life with acceptable sensory values. Such fermented systems could hold promise as a valuable alternative source of nutrients, particularly in many developing countries where children, adults and the elderly have a high prevalence of lactose intolerance with limited access to nutritious foods [

13]. Although tiger-nuts based vegetable yoghurt is important for people with intolerances to dairy products [

3], studies on the impact of pretreatment methods on the sensory and nutritional properties of a vegetable yoghurt made with tiger nuts are scarce. The aim of this work was to evaluate the sensory and nutritional properties of a yoghurt-like product made from tiger nuts pretreated by various methods (soaking, drying, roasting, boiling and germination).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Dried and mature tiger nuts (Cyperus esculentus L.) and starter culture were purchased at the Mokolo market, (Yaoundé, Cameroon). Once at the Laboratory of Food Sciences and Metabolism (LabSAM) of the University of Yaoundé 1 where the experiments took place, those nuts were sorted to get rid of any foreign body and/or deteriorated one. The starter culture was two weeks old, homemade plain yoghurt, kept in a refrigerator (4°C) and made of a mixture of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophillus.

2.2. Pretreatment and Preparation of Tiger Nut Yoghurt

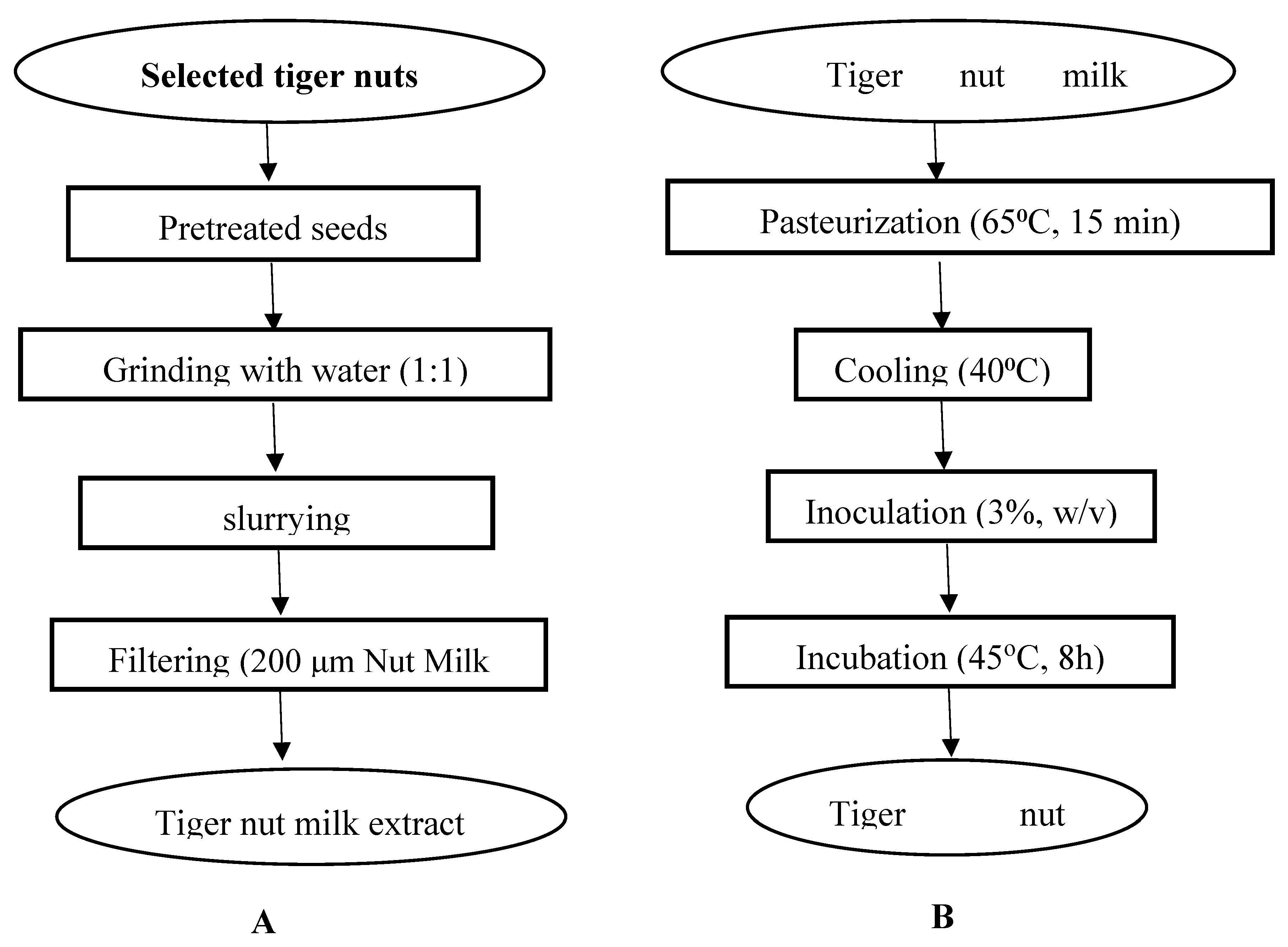

Six kinds of vegetable yoghurt were produced from the milk obtained after different pre-treatment methods of the tiger nuts. The pretreatment methods used were soaking, germination, roasting, drying and boiling. The control sample encoded “TeYS” was prepared with tiger nuts that had not undergone any pretreatment. For soaking pretreatment, approximately 500 g of tiger nuts were soaked for 24 hours in 3 litres of distilled water. The water was changed every 3 hour to avoid spontaneous fermentation. Germination consists on spreading out 500g of seeds on jute bags which were moistened every 12 h for 72 h to stimulate germination. For roasting, 500 g of dried nuts were pan-roasted (open roasting method) at around 300°C for 15 min. For drying, 500 g of nuts were dried in an oven at 45°C for 48 h, and for boiling, 500 g of nuts were introduced into 3 L of boiling water for 30 min. Milk extraction was carried out according to the modified protocol of Seydi, 2002 (

Figure 1a). The various milk samples obtained previously were pasteurised at 63°C for 30 minutes before being cooled to a temperature of approximately 45°C. One litre of pasteurised milk was homogenised using a mixer before being inoculated with the starter at a concentration of 3% (w/v) (

Figure 1b). The resulting preparation was incubated at 45°C for 8 h. The yoghurts obtained were refrigerated in sterile plastic bottles and coded. The codes TYS, EYS, SYS, GYS and RYS were assigned to the yoghurt samples produced from tiger nuts pretreated with the following methods respectively: soaking, boiling, drying, germination and roasting.

2.3. Physico-Chemical Analysis of Samples of Tiger Nut Yoghurts

2.3.1. pH and Total Titratable Acidity

The pH value was determined by the direct reading with the digital pH metre (Hanna HI-98128) as given in KC and Rai, [

14].

Titratable acidity was determined by neutralising the acid present in 10 g of the yogurt samples using 0.11 N NaOH solution. The titration was performed using 10 drops of phenolphthalein as indicator until a pink endpoint was reached. The quantity of NaOH used to neutralise the solutions was divided by 10 in order to obtain the titratable acidity.

2.3.2. Syneresis

The degree of syneresis was measured by a method used by Lee and Lucey [

15]. A 100 g sample of yoghurt was placed on a filter paper resting on the top of a funnel. After 10 min of drainage in vacuum condition, the quantity of the remained yoghurt was weighed and syneresis was calculated as follows:

2.3.3 Water Holding Capacity

The method described by Silva and O’Mahony [

16] was followed for the analysis of water holding capacity. In brief, 20 g of yogurt sample was placed in 50 mL tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and centrifuged at 640× g for 20 min at 4 °C in a Sorvall RC 5C Plus centrifuge, equipped with a Sorvall SS-34 rotor (Du Pont Instruments, Wilmington, DE, USA), after which the supernatant was collected and weighed. Water holding capacity (WHC) was calculated according to the equation below:

2.4. Proximate Analysis,

2.4.1. Moisture Content

The method described by AFNOR [

17] was adopted for the determination of moisture content of vegetable yoghurt sample. A clean crucible was dried to a constant weight in air oven at 110°C, cooled in a desiccator and Weighed (W1). Two grams of yoghurt sample was accurately weighed into the previously labeled crucible and reweighed (W2). The crucible containing the sample was dried in the same oven to constant Weight (W3). The percentage moisture content was calculated thus:

2.4.2. Ash content

The methodology set by AFNOR [

17] was used for the determination of ash content. The porcelain crucible was dried in an oven at 100°C for 10 min, cooled in a desiccator and Weighed (W1). Two grams of the vegetable yoghurt sample was placed into a previously weighed porcelain crucible and reweighed (W2), it was first ignited and then transferred into a furnace which was set at 550°C. The sample was left in the furnace for eight hours to ensure proper ashing. The crucible containing the ash was then removed; cooled in a desiccator and Weighed (W3).

The percentage ash content was calculated as follows:

2.4.3. Lipids

The determination of crude lipid content was done with soxhlet apparatus according to the method describe by Bourely [

18]. A clean, dried 500 cm3 round bottom flask containing few anti-bumping granules was Weighed (W1) with 300 cm3 hexane) for extraction poured into the flask filled with soxhlet extraction unit. The extractor thimble weighing twenty grams was fixed into the Soxhlet unit. The round bottom flask and a condenser were connected to the Soxhlet extractor and cold water circulation was connected/put on. The heating mantle was switched on and the heating rate adjusted until the solvent was refluxing at a steady rate. Extraction was carried out for 6 h. The solvent was recovered and the oil dried in an oven set at 70°C for 1 h. The round bottom flask and oil was then Weighed (W2). The lipid content was calculated thus:

2.4.4. Crude Fibre Content

The determination of crude fibre was done according to the method describe by A.O.A.C [

19]. The defatted yoghurt sample (1 g) was weighed into a round bottom flask, 100 cm

3 of sulphuric acid solution (0.25 M) was added and the mixture boiled under reflux for 30 min. The hot solution was quickly filtered under suction. The insoluble matter was washed several times with hot water until it was acid free. It was quantitatively transferred into the flask and 100 cm

3 of hot 0.31 M, Sodium Hydroxide solution was added, the mixture boiled under reflux for 30 min and filtered under suction. The residue was washed with boiling water until it was base free, dried to constant weight in an oven at 100°C, cooled in a desiccator and weighed (C1). The weighed sample (C1) was then incinerated in a muffle furnace at 550°C for 2 h, cooled in a desiccator and reweighed (C2).

Calculation: The loss in weight on incineration = C1-C2

2.4.5. Crude Protein Content

Crude protein content was determined following the Kjeldahl method [

20] for the mineralization of nitrogen, and the method of Davani et al, [

21] for the titration of nitrogen.

The ground defatted sample (91.5 g) in an ashless filter study was dropped into a 300 cm3 Kjeldahl flask. The flask was then transferred to the Kjeldahl digestion apparatus. The sample was digested unit a clear green colour was obtained. The digest was cooled and diluted with 100 cm3 with distilled water.

Distillation of the digest: Into 500 cm3 Kjeldahl flask containing antibumping chips and 40 cm3 of 40% NaOH was slowly added to the flask containing mixture of 50 cm3 2% boric acid and 3 drops of mixed indicator was used to trap the ammonia being liberated. The conical flask and the Kjeldahl flask were then placed on Kjeldahl distillation apparatus with the tubes inserted into the conical flask, heat was applied to distill out the NH3 evolved with the distillate collected into the boric acid solution. The distillate was then titrated with 0.1 MHCl.

Calculation:

where,

M = Actual Molarity of Acid, V = Titre Value (Volume) of HCl used, Vt = Total volume of diluted digest, Va = Aliquot volume distilled

2.4.6. Carbohydrate

Carbohydrate contents were determined according to the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [

22]. The carbohydrate value was expressed as the difference of the protein, fat, crude fiber, total ash, and moisture content of the sample from 100%.

2.5. Bioactive Compounds

2.5.1. Total Phenolic and Total Flavonoids Contents

The total phenolic content and the total flavonoids content were determined according to the methods described by Chandra et al, [

23]. For total phenolic compounds, of Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent (10%) and Na2CO3 (7%) were used. Gallic acid solutions in methanol (5-500 mg/L) were prepared for the standard curve, and total phenolic content was calculated as mg Gallic acid equivalents per gram of fresh weight of the sample (GAE/g). Total flavonoid content of the extract was investigated using the aluminium chloride colourimetric. The standard calibration curve was prepared for Quercetin; the total flavonoid content was expressed as milligram quercetin equivalent per gram of extracted sample based on a standard curve of Quercetin (mg QCE/g sample).

2.5.2. Alkaloid Content

The total alkaloid content in ethanolic extracts of yoghurt were determined according to method employed by Singh et al [

24], using quinine as standard. The total alkaloid content of the samples was measured using 1,10-phenanthroline. The reaction mixture contained 1ml yoghurt extract, 1ml of 0.025M Ferric chloride in 0.5M hydrochloric acid and 1ml of 0.05M of 1, 10-phenantroline in ethanol. The mixture was incubated for 30 minutes in hot water bath with maintained temperature of 70ºc.The absorbance of red coloured complex was measured at 510nm against reagent blank. Alkaloid contents were estimated and it was calculated with the help of standard curve of quinine.

2.6. Antinutritional Factors

2.6.1. Oxalate Content

The titration method described by Aina et al., [

25] was used to determine the oxalate content of the sample. One gram of dry yoghurt sample was macerated with 75 mL of 3 mol/L H2SO4 in a conical flask. The mixture was stirred with a magnetic stirrer for 1 h and filtered. The filtrate (25 mL) was collected and heated to 80–90 °C then maintained at 70 °C. The hot aliquot was titrated continuously with 0.05 mol/L of KMnO4 until the end point of a light pink colour which persists for 15 s. The oxalate content was calculated by taking 1 mL of 0.05 mol/L of KMnO4 as equivalent to 2.2 mg oxalate.

2.6.2. The phytic acid concentration was determined using wade reagents of 0.03% FeCl3. 6H2O and 0.3% sulfosalicylic acid. A standard phytic acid curve was constructed under the same conditions, and results were expressed as phytic acid mg/100 g of fresh weight of the sample [

26]

2.6.3. Saponin Content

Saponin content was determined by weight difference after extraction in solvent [

27]. To a conical flask containing 50 ml of 20% aqueous ethanol, 2 g each of samples was added. With continuous stirring, the samples were heated over a hot water bath (at about 55°C ) for 4 hours, then filter. The residue was re-extracted with another 50 ml of 20% ethanol. This was followed by reduction of combined extracts to 40 ml over water bath at 90°C. 20 ml of diethyl ether was added and shaken vigorously after concentrates were transferred into a 250 ml of separator funnel. The purification process was repeated after recovered of aqueous layer and discarding of the ether layer. This is followed by addition of 60 ml of n-butanol extract, then washing twice of combined n-butanol (extracted) in 10 ml of aqueous sodium chloride. The remaining solution was heated in a water bath. After evaporation, the sample was dried in the oven to a constant weight after evaporation. The saponins content was calculated as percentage.

where, B = Weight of Whatmann filter paper, A = Weight of Whatmann filter paper with sample, and S = Sample weight.

2.6.4. Condensed Tannins

Condensed tannins content of samples was determined by Ndhlala et al., [

28]. 3 ml of butanol–HCl reagent (95:5, v/v) was added to 500 μl of each extract, followed by 100 μl ferric reagent (2% ferric ammonium sulphate in 2 N HCl). The test combination was vortexed and placed in a water bath (1000C) for 60 min. The absorbance was then read at 550 nm against a blank prepared in a similar way, but without heating. Each extract had three replicates. Condensed tannin (%) was calculated as leucocyanidin equivalents using the formula developed by Porter et al. [

29]

With A550, the absorbance of the sample at 550 nm and Rd is the extraction yield.

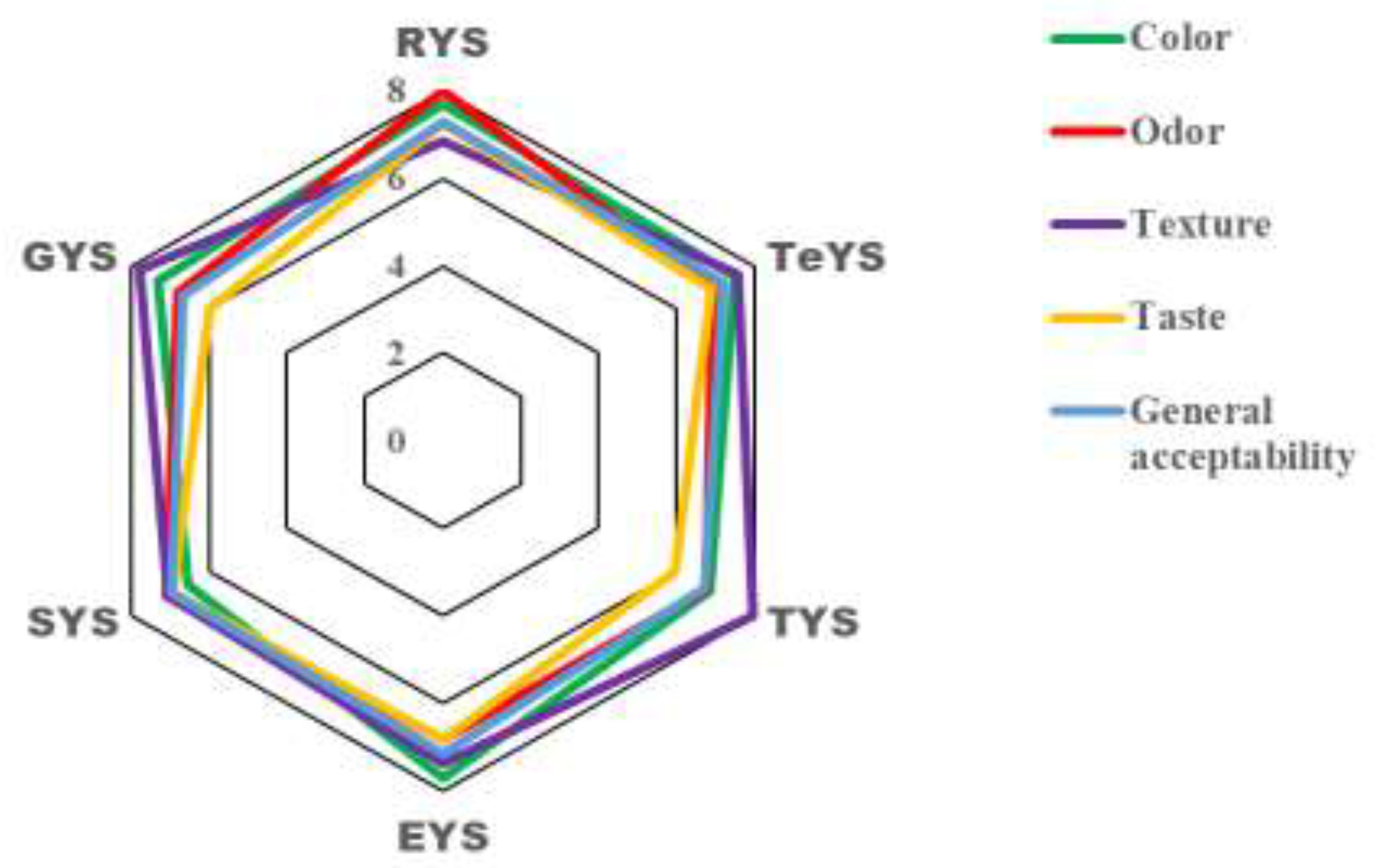

2.7. Sensory Evaluation and Acceptability of Pretreated Tiger Nut Yoghurt

Sixty untrained consumer panelists were recruited, targeting souchet eaters among students at the University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon. The age of the panelists ranged from 18 to 36 years. The souchet yoghurt evaluation was repeated three times in sessions of 2.5 h per day in the morning for three days [

30]. Yoghurts with pre-treated seeds and the control were presented to each panelist and labelled with a random three- to four-letter code. Operationally, 50 ml of each sample of fresh tiger nuts yoghurt contained in opaque jars was presented simultaneously to panelists who had been fasting for at least 6 hours. The panelists were instructed to rinse their mouths thoroughly with mineral water between samples. The panelists were asked to assess the yoghurts in terms of their aroma, taste, colour, texture and general acceptability by scoring them on a nine-point hedonic scale (1 means the yoghurt is extremely unpleasant and 9 means it is extremely pleasant).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using a oneway analysis of variance (ANOVA) for chemical composition, and sensory acceptability data. The experiments were run in triplicate. Means were separated using Turkey's (HSD) test, and p-values <0.05 at 95 percent confidence the interval was considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Tiger Nut Yoghurts

In this study, the quality control of vegetable yoghurt samples was carried out by determining some of their physico-chemical characteristics.

Table 1 below shows the physico-chemical characteristics (pH, Total Titratable Acidity, Syneresis, Water Holding Capacity) of the yogurt samples immediately after manufacture. These characteristics represent not only the indicators of fermentation, but also the indicators of quality and the criteria of consumer preferences for this category of food product [

15,

31,

32].

The pH values of the manufacture products range from 4.11 in the control sample (TeYS) to 4.75 in the yoghurt obtained from roasted nuts (RYS). Conversely, the titratable acidity varies from 0.89 % in RYS samples to 1.88 % in control samples. These results corroborate those obtained by Odejobi et al, [

33] who found that the pH and titratable acidity of tiger nuts yoghurts were ranged from 3.93 to 5.06 and from 0.45 to 2.04 % respectively.

With regard to syneresis and water holding capacity, no significant differences were observed between the different products obtained. This suggests that fermentation did not have any significant effect on these parameters. Among these products, samples obtained after roasting the nuts have the lowest syneresis values (18.11%) while control yoghurts (39.73%) and those obtained from soaked nuts have the highest water holding capacity (39.06%). Water holding capacity is an important parameter of yoghurts, linked to its ability to form gels. In fact, acidification of the medium during fermentation leads to the accumulation of casein that captures water molecules. This parameter is particularly important because it is responsible for the texture of yoghurt and essential for microbial growth [

34,

35,

36]. Syneseris, on the other hand, is an undesirable parameter because it reflects the capacity of yogurt to lose water. Vegetable yogurts with low syneresis have a stable texture. This indicates that these products have good water retention capacity and a greater capacity to maintain the stability of a gel [

37].

3.2. Proximate Analysis of Nutritional Composition of Souchet Yoghurts

The table 2 presents the proximate composition of yogurt samples made from pretreated tiger nuts. A significant variation (P<0.05) in the nutrient composition of the different yogurts was recorded as a function of the pretreatments applied to the tiger nuts. Pretreatment of tiger nuts by drying resulted in a significantly higher fat content (8.89 g/100gMS) as did the protein content (5.46%) in the yoghurt sample manufactured with germinating tiger nuts. The ash content (1.67%) which represents the total mineral content was higher in the sample obtained after pretreated the tiger nuts by roasting while boiling of tiger nuts led to yoghurt sample with the higher fibre content (2.80 %). The higher level of ash in yoghurt made with roasting nuts could provide more minerals to the organism. However, these values were lower to the average ash content in tiger nuts according to Muhammed et al. [

38], which is 2.2%. The protein content ranged between 4.01 to 5.46 % while fiber content ranged between 0.55 to 2.8 %. These results of protein and crude fiber contents are similar with those found by Akoma and Elekwa [

39] and Matela et al, [

40]. The fibre content of the yoghurt increase according to the type of pre-treatment applied to the tiger nuts prior to the formulation of the yoghurt. Because of its fibre content, yoghurt with boiled nuts particularly could facilitate digestion. Crude fibre or insoluble fibre speeds up the transit of food through the digestive system and, in so doing, promotes the regularity or evacuation of stools [

41]. The drying of nutsedge seeds for the formulation of yoghurt gives it a higher energy value compared with other pretreatments applied to tiger nuts, 165, 81±7.85, which could be explained by the high lipid content of this yoghurt. The germination of tiger nuts results in a higher protein content in the yoghurt. This observation is due to the activation of proteolytic enzymes during germination, such as proteases, which break down reserve proteins into amino acids that can then be used to synthesise new proteins [

42,

43]. Moisture contents ranged between of 75,98 and 67,54 % and were relatively higher than those of cow milk yoghurt. This is in agreement with similar study by Cheng [

44], who revealed that high moisture in vegetable yoghurts such as soy yoghurt is present as free water that is not incorporated in the coagulated protein. This implies the occurrence of syneresis during coagulation. In addition, high moisture content in yoghurt is typical and essential for its refreshing and thirst-quenching properties. However, such a level of hydration requires that the product should be store in a cool environment to prevent microbial growth and thus extend its shelf life [

45]. The range of crude fat content was higher compared to those found by Bristone et al, [

46] in tiger nut yoghurt from Nigeria. Fat is a major component in these samples aside from moisture content, contributing to the overall texture and mouthfeel of the yoghurt. Fats also provides essential fatty acids and aids in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins [

47]. The yoghurt with dried tiger nuts contained more lipids than the other yoghurts. This could be explained by the pre-treatment method, i.e. drying, which makes the lipids contained in the nuts more available. Since fat is contributing for energy, tiger nuts yoghurt made from dry nuts could provide the body with a considerable amount of energy.

3.3. Bioactive Compounds Contents

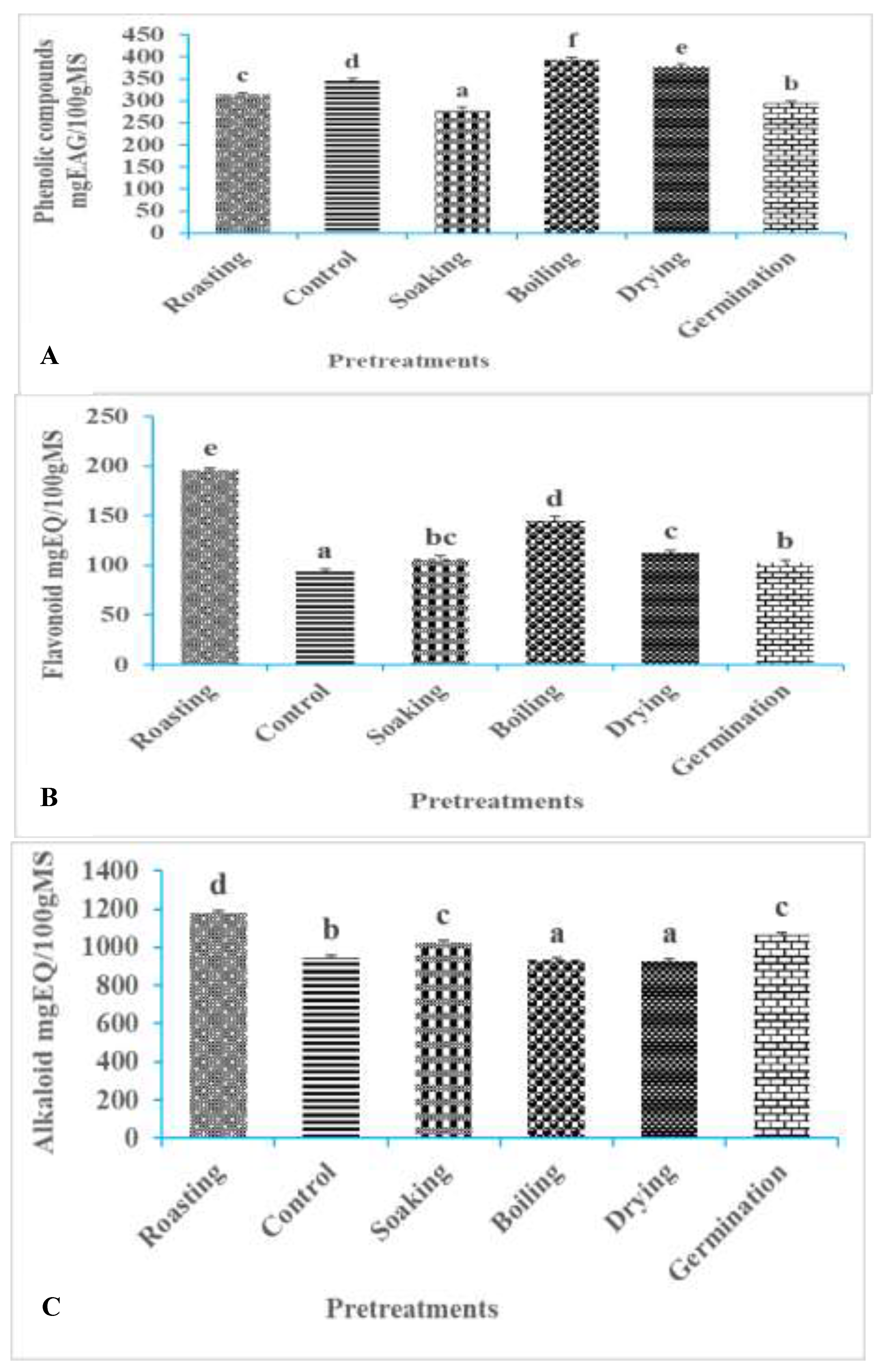

The bioactive compounds in the yoghurts are shown in

Figure 2 ( a, b c). A large significant variation (P<0.05) in the concentration of bioactive compounds in the different yoghurts was recorded in relation to the pretreatments. The concentrations of phenolic compounds (

Figure 2a), flavonoids (

Figure 2b) and alkaloids (

Figure 2c) were significantly affected by the pretreatment methods. Boiling tiger nuts had the greatest significant influence (P<0.05) on the concentration of phenolic compounds in the yoghurt samples, whereas roasting those nuts gave the highest concentrations of flavonoids and alkaloids compared with the other pretreatment methods and the control. In fact, boiling the tiger nuts to formulate the yoghurt resulted in the highest content of phenolic compounds (393.39±1.65mgEAG/100g). This would be due to the heat that would allow the degradation of the cell walls of the tiger nuts seeds, thus releasing the bound phytochemical compounds, and boiling can activate the enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of these compounds, thus increasing their concentration. [

48,

49]. Roasting nutsedge seeds leads to an increase in flavonoids and alkaloids in nutsedge yoghurt compared with other pretreatments because during the roasting process, the heat applied can cause Maillard reactions between carbohydrates and amino acids, forming new phenolic compounds and alkaloids. Similarly, roasting also promotes the release and concentration of flavonoids already present in nutsedge seeds [

50].

3.4. Antinutrients in Tiger Nut Yoghurts

A significant decrease (P<0.05) in all the antinutrients assessed was observed after pretreatment of the tiger nuts. (

Table 3). The rate of decrease was greatest in the yoghurt for saponins (68 %; 17.84mg/100MS) with germinated tiger nuts, for phytates (43%; 0.37mg/100MS) with roasted tiger nuts; and tannins (69%; 7.83mg/100MS) with dried tiger nuts. Antinutrients interferes with digestion and reduces their nutritional contribution, leading to numerous undesirable effects in the body [

51]. The reduction in oxalates and saponins is more significant in yoghurt where the seeds have undergone germination and drying for tannins because during germination, the natural enzymes in tiger nut seeds are activated, which can help break down antinutrients and improve nutrient digestibility [

52]. Roasting, on the other hand, is the seed pretreatment that reduces the phytate content of yellow nutsedge yoghurt the most. During roasting, the heat degrades the phytates, making them less active, and the proteins present in the nutsedge seeds undergo structural changes that can lead to a reduction in phytate activity, such as enzyme and lectin inhibitors and their ability to form complexes with minerals and interfere with their absorption [

53]. Tannins can bind to proteins and minerals, reducing their bioavailability [

54]. While tannins have been noted for their antinutritional effects, they also offer health benefits, such as improving heart health by lowering blood pressure [

55], having antibacterial properties [

56], and potential neuroprotective effects that might slow down conditions like dementia and Parkinson’s disease [

57]. According to Oly-alawuba and Obiakor-Okeke, [

58], the inconvenients with phytates is that, they can chelates positively charged cations such as zinc, magnesium, iron and calcium and form insoluble complexe, making those minerals unavailable for absorprtion. However, phytates may also have some beneficial effects, such as acting as antioxidants, having antineoplastic properties and reduction of pathological calcifications in blood vessels and organs [

59,

60]. All yoghurt samples have low levels of oxalate range from 0.26 mg/100gMS in yoghurt sample made with germinated nuts to 0.63 mg/100gMS in product made with untreated sample. High levels of oxalates can interfere with calcium absorption and lead to the formation of kidney stones [

61]. However, the low levels found in the yoghurt samples are unlikely to pose a significant health risk.

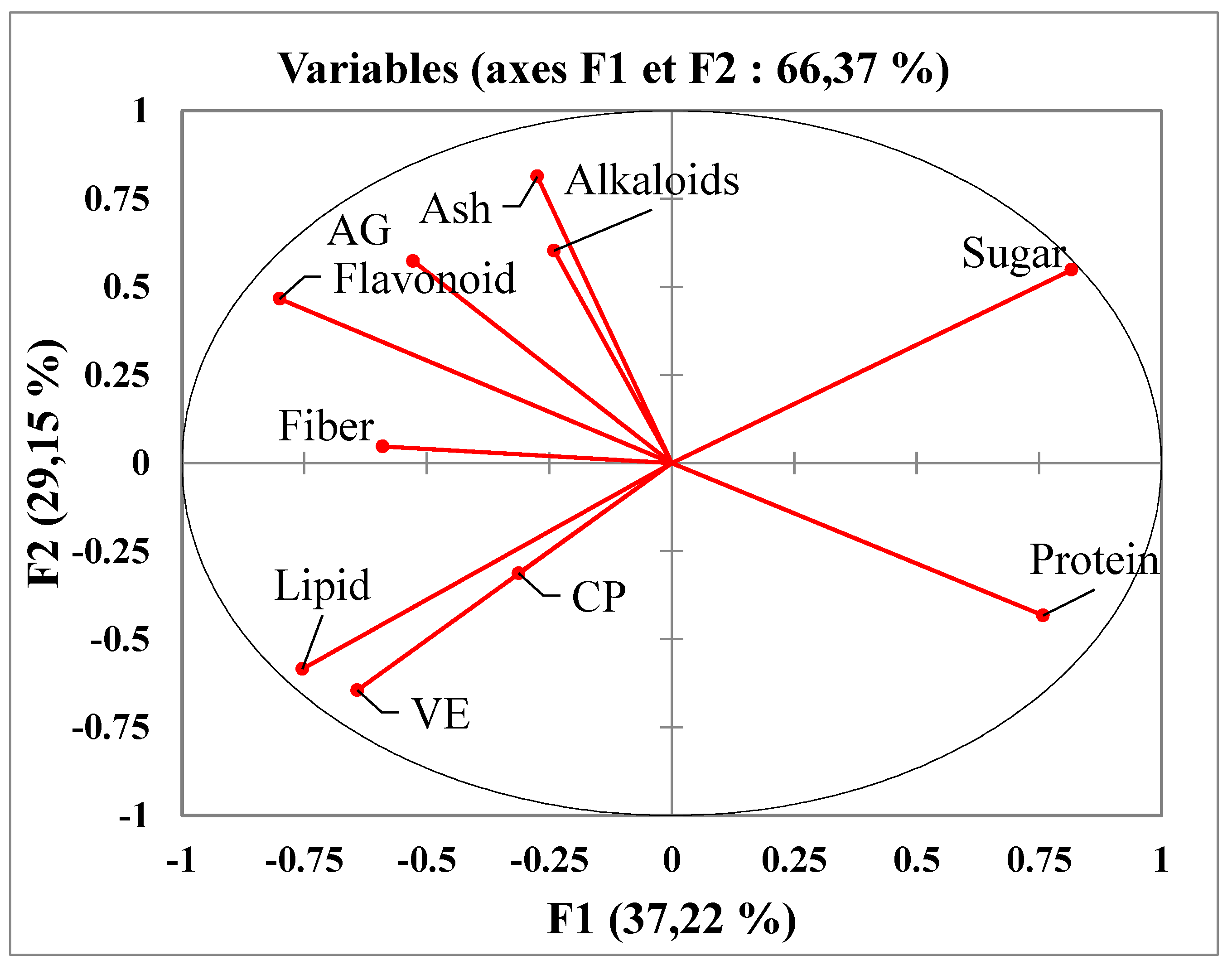

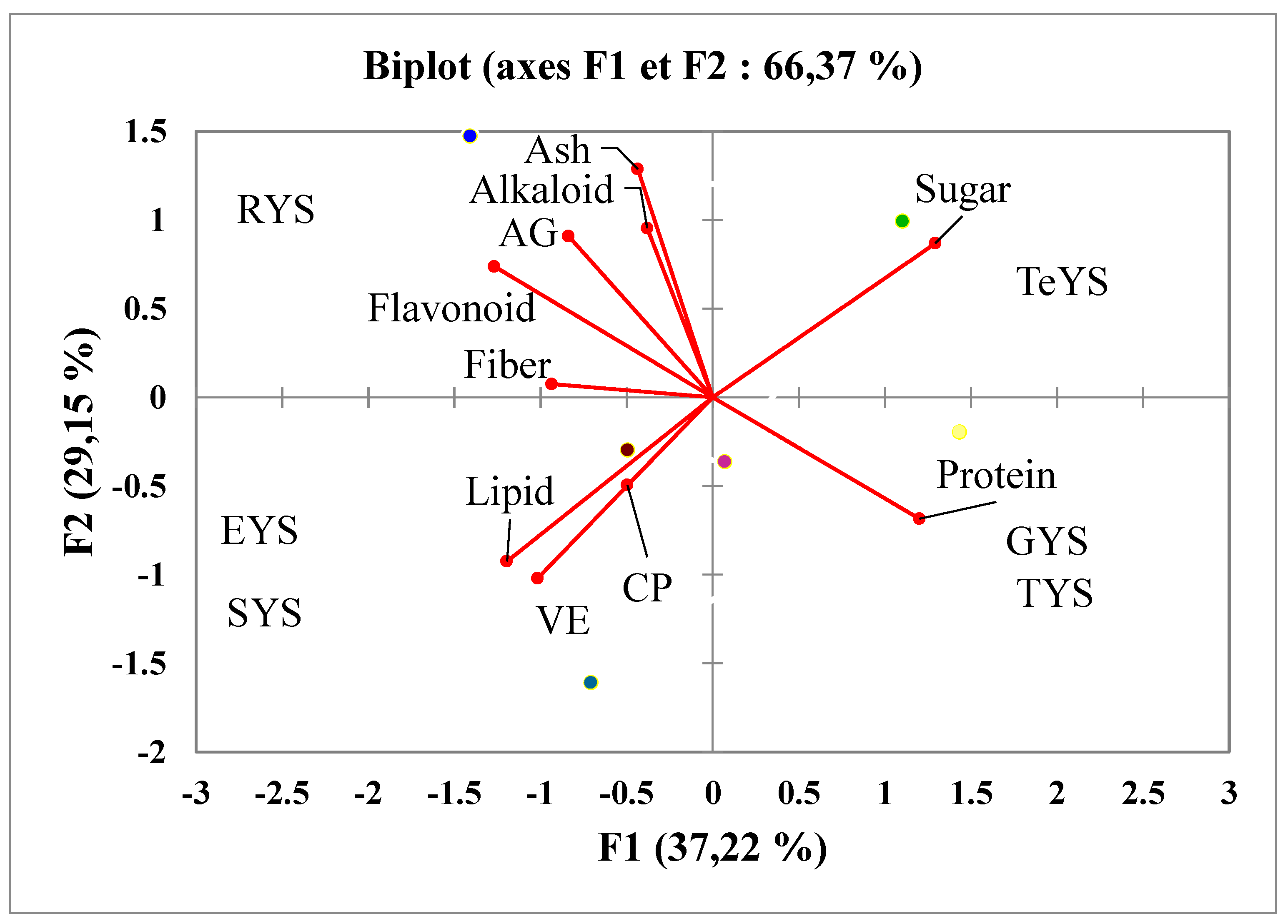

3.5 Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out to classify the different yoghurts according to their general acceptability and their nutritional and functional value. Different yoghurts according to their general acceptability as well as their nutritional and functional value.

Figure 3 shows the correlation circle between the different variables, in particular general acceptability, nutritional value (ash, energy value, sugars, fat, protein, fibre) and bioactive compounds (phenolic compounds, flavonoids and alkaloids). The figure shows that these variables contribute 66.37% to the formation of the (F1xF2) axis system. The F1 axis alone explains 37.22% of the variables observed, while the second axis, F2, explains 29.15%.

Figure 4 shows that the yoghurts whose nuts had undergone germination and soaking showed a positive correlation with the proteins in the tiger nuts yoghurt. The control, on the other hand, showed a positive correlation with sugars.

Table 4 below shows the average scores for the sensory attributes attributed by panelists following the preference test on the various samples of tiger nuts yoghurt produced. This shows that, with the exception of the taste of tiger nuts yoghurt, produced from soaked seeds (TYS), the sensory attributes of all the other products received average scores of over 6 (a little pleasant). It should be noted that for each sensory attribute, the average score awarded is correlated with the panel's assessment. The average scores attributed to smell (7.98), taste (7.23) and general acceptability (7.28) were higher for tiger nuts yoghurts produced with roasted seeds. Yellow nutsedge yoghurts produced from soaked seeds (TYS) received the highest average score for texture (7.98), while those produced from boiled seeds (EYS) received the highest average score for colour (7.70). Munzur et al., [

62] described that the colour of the yogurt depends on the colour of milk used.

Figure 5 below show the general acceptability of tiger nuts yoghurt samples made by panelists. Yoghurt made from roasted tiger nuts had the highest score, followed by the control, boiling, drying, soaking and sprouting. This is perhaps due to Maillard reaction that occurred during the roasting of dry tiger nuts causing browning in the final product [

63]. Significant differences (P<0.05) were found between these samples, namely sprouting, the control, drying and boiling. However, more than 53.48% of panelists said they liked these yoghurts with a preference for roasting, which is in line with the results. Taste and texture were the main contributors to this score, but odour and colour were sensory attributes that had a negative impact on overall acceptability.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this work was to evaluate the sensory and nutritional properties of a yoghurt-like product made from tiger nuts pretreated by various methods (soaking, drying, roasting, boiling and germination). From the results, the pretreatment of tigernut seeds is a better alternative for the formulation of tigernut yoghurt, as it improves not only the sensory parameters of tigernut yoghurt but also its nutritional values. The pre-treatment of tiger nuts also reduces significantly the anti-nutrient content of the yoghurt. The preparation of yoghurt like product from tiger nuts is of economic significance since cow milk is relatively expensive and highly perishable. Among all the pretreatment methods carry out in this study, the roasting, the germinating and soaking of tiger nuts seem to be the most promising pre-treatment techniques as regard to the sensory properties, the level of nutritional, bioactive and antinutritional compounds. This transformation is a major innovation in the tiger nut yoghurt production process. The consumption of yoghurt made from plant products such as tiger nuts will be of great importance, both to overcome intolerance to animal milk and for its nutritional benefits. However, further research is recommended to explore the long-term stability and shelf-life of pretreated tiger nut yoghurt.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.K.S., G.M.M., G.A. R.P., E.F., and M.A.; methodology, A.G.K.S.. H.M.C., G.M.M., A.R, ; software, G.M.M, A.R,.; validation, A.G.K.S., I.S.B., G.M.M., E.F., and M.A; formal analysis, I.S.B., G.M.M.,; investigation, G.M.M., H.M.C., A.R,; resources, H.M.C.; data curation, A.G.K.S., I.S.B., G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.K.S., I.S.B., G.M.M.,; writing—review and editing, A.G.K.S., I.S.B., G.M.M., G.A.,; visualization, A.G.K.S, I.S.B., E.F., and M.A; supervision, A.G.K.S. G.A., R.P., E.F., and M.A; project administration, A.G.K.S., G.A., R.P., E.F., and M.A;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Farinde E., Obatolu V., Fasoyiro, S. (2017). Microbial, nutritional and sensory qualities of baked cooked and steamed cooked lima beans. American Journal of Food ScienceTechnology. 5(4): 156-161. [CrossRef]

- Glanville JM, Brown S, Shamir R, Szajewska H, Eales JF. (2015). The scale of the evidence base on the health effects of conventional yogurt consumption: Findings of a scoping review. Front Pharmacol 2015;6:246. [CrossRef]

- Balogun, O.O., Dagvodorj, A., Anigo, K.M., Ota, E. & Sasaki, S. 2015. Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr, 11(4): 433-451. [CrossRef]

- Ye M, Ren L, Wu Y, Wang Y, Liu Y. Quality characteristics and antioxidant activity of hickory-black soybean yogurt. LWT – Food Science and Technology. 2013;51(1):314–318. [CrossRef]

- Grasso, N.; Alonso-Miravalles, L.; O’Mahony, J.A. Composition, physicochemical and sensorial properties of commercial plant-based yogurts. Foods 2020, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele A. K., Aina J. O. K. (2007). Chemical composition and functional properties of flour from two varieties of tigernut (Cyperus esculentus). African Journal of Biotechnology, volume (21): 2473-2476. [CrossRef]

- Shaker, M.A., Ahmed, M.G., Amany, M.B. and Shereen, L.N. (2009) Chufa Tubers (Cyperusesculentus L.): As a New Source of Food. World Applied Sciences Journal, 7, 151-156.

- Emurotu, J.E. (2017) Comparison of the Nutritive Value of the Yellow and Brown Varieties of Tiger Nut. IOSR Journal of Applied Chemistry, 10, 29-32.

- Imam, T., Aliyu, F. and Umar, H. (2013) Preliminary Phytochemical Screening, Elemental and Proximate Composition of Two Varieties of Cyperus esculentus (Tiger Nut). Nigerian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 21, 247-251. 10.4314/njbas.v21i4.

- El-Naggar, E. (2017). Biological Effect of Tiger Nut (Cyperusesculentus L.) Oil on Healthy and Hypercholesterolemia Rats. Syrian Journal of Agricultural Research, 4,133-147.

- Ndiaye, M., 2002. Contribution à l'étude de conformité de l'étiquetage et de la qualité microbiologique des yaourts commercialisés à Dakar. DEA Thesis: Animal Production: Dakar (EISMV); 9.

- Adeiye, O.A., Gbadamosi, S.O. and Taiwo, A.K. (2013). Effects of some processing factors on the characteristics of stored groundnut milk extract Academic Journals of Food Science, 7(6): 134-142. 10.5897/AJFS12.149.

- Bertrand-Harb, C., Ivanova, I. V., Dalgalarrondo, M. & Haertll, T. (2003). Evolution of blactoglobulin and a-lactalbumin content during yoghurt fermentation. International Dairy Journal 13, 39-45. [CrossRef]

- KC, J. B., & Rai, B. K. (2007). Basic food analysis handbook (1st ed.). Kathmandu, Nepal: Mrs. Maya K.C.

- Lee,W.; Lucey, J. Formation and Physical Properties of Yogurt. Anim. Biosci. 2010, 23, 1127–1136. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V.C.; O’Mahony, J.A. Microparticulated whey protein addition modulates rheological and microstructural properties of high-protein acid milk gels. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 78, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFNOR (Association Française de Normalisation) (1982) Recueil des normes françaises des produits dérivés des fruits et légumes. Jus de fruits. 1ère éd., Paris la défense.

- Bourely, J. (1982) Observations on the Dosage of Cottonseed Oil. Cotton and Tropical Fibers, 27, 183-196.

- A.O.A.C. (1980). Official Methods of Analysis (13th Ed) William Horwitz, Washington, D.C. Association of Official Analytical Chemistry.

- AFNOR, 1984. Recueil française : corps gras, graines oléagineuses et produits dérivés. Paris. 459p.

- Davani, M.B., Shishoo, C.J Shah and Suhagia, M.B. (1989). Spectrophotometric methods for micro determination of nitrogen in Kjeldahl digest. Micro-chemical Methods. [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis. 20th ed., Association of Official Analytic Chemists, Washngton DC: (2012).

- Chandra Suman, Shabana Khan, Bharathi Avula, Hemant Lata, Min Hye Yang, Mahmoud A Elsohly, Ikhlas A Khan. 2014. Assessment of total phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant properties, and yield of aeroponically and conventionally grown leafy vegetables and fruit crops: a comparative study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Volume 2014, Article ID 253875, 9 pages. [CrossRef]

- Singh Dhruv, K., Bhavana Srivastava and Archana Sahu. (2004). Spectrophotmetric Determination of Rauwolfo Alkaloids: Festimation of Reserpine in pharmaceuticals, 20: 571- 573. [CrossRef]

- Aina, V.O., Sambo, B., Zakari, A., Haruna, H.M.S., Umar, K., Akinboboye, R.M. and Mohammed, A. 2012. Determination of nutritional and antinutritional content of Vitis vinifera (grapes) grown in Bomo (Area C) Zaria, Nigeria. Adv. J. Food Technol. 4(6):225-228.

- Olayeye, L.D., Owolabi, B.J., Adesina, A.O. and Isiaka, A.A. 2013. Chemical composition of red and white cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) leaves. Int. J. Sci. Res. 11(2):121-125.

- Obadoni, B.O. and Ochuko, P.O. 2001. Phytochemical studies and comparative efficacy of the extracts of some haemostatic plants in Edo and Delta States of Nigeria. Glob. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 8:203-218. [CrossRef]

- Ndhlala, Kasiyamhuru, Mupure, Chitindingu, Benhura and Muchuweti (2007): Phenolic composition of flacourtia indica, Opuntia megacantha and Sclerocarya birrea. Composition of flacourtia indica, Opuntia megacantha and Sclerocarya birrea. Food Chemistry. 103(1): 82- 87. [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.J., Hrstich, L.N. and Chan, B.G. (1986) The Conversion of Procyanidins and Prodelphinidins to Cyanidin and Delphinidin. Phytochemistry, 25, 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Lawless H, Heymann H (1999). Sensory syrup in baking and confectionery. Food Evaluation: Principles and Practices. Pak J Nutr 11(8): 688-695.

- Martin, F.; Cachon, R.; Pernin, K.; De Coninck, J.; Gervais, P.; Guichard, E.; Cayot, N. Effect of oxidoreduction potential on aroma biosynthesis by lactic acid bacteria in nonfat yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.S.; Cisneros, M.G. Quality control in yogurt: Alternative parameters for assessment. Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 1, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Odejobi Oludare Johnson, Babatunde Olawoye and Orobola Roland Ogundipe. 2018.0Modelling and Optimisation of Yoghurt Production from Tigernut (Cyperus esculentus L.) Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Asian Food Science Journal 4(3): 1-12; Article no.AFSJ.44137.

- Hole, M. Storage Stability.Mechanisms of Degradation. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 2nd ed.; Caballero, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 5604–5612. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M.; Stanton, C.; Slattery, H.; O’Sullivan, O.; Hill, C.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Casein fermentate of Lactobacillus animalis DPC6134 contains a range of novel propeptide angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4658–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, C.; Qi, J.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. NMR Relaxometry ofWater in Set Yogurt During Fermentation. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2008, 17, 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- Chaima Sellami & Merabet Abdennour.2023. L'effet des fruits sur la qualité des produits laitiers "yaourt". Université Badji - MOKHTAR – Annaba. Faculté : Sciences ; Département : Biochimie. 74 pages.

- Muhammad, N.O., Bamishaiye E.I., Bamishaiye, O.M., Usman, L.A., Salawu M.O,Nafiu., M.O and Oloyede O.B. (2011).Physicochemical Properties and FattyAcid Composition of Cyperus esculentus (Tiger Nut) Tuber Oil. BioresearchBulletin 5: 51-54.

- Akoma and Elekwa 2000. Yoghurt from coconut and tiger nuts. The journal of Food Technology in Africa. Vol 5. 4. 132-134.

- Matela KS, Pillai MK, Ranthimo PM, Ntakatsane M. Analysis of Proximate Compositions and Physiochemical Properties of Some Yoghurt Samples from Maseru, Lesotho. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research 2 (2019): 245-252.

- Bingham S. A., Day N. E. and Luben R. (2003). Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer nutrition (EPIC): An Observational Study, Lancet, 361: 1496-1501.

- Gallardo, K. ,Job, C., Groot, S. p., Puype, M., Demol, Vandekerckhove, J.et Job,b.(2001). Protemics of Arabidopsis seed germination and establishment of early defense mechanisms. Plant physiology, 1 (3),910-923.

- Rajjou, L., Belghazi, M., Huguet, R., Robin, C., Moreau, A., Job, C., et al. (2006). Proteomic investigation of the effect of salicylic acid on Arabidopsis seed germination and establishment of early defense mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 141, 910–923. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.J (1988). Comparison of dairy yoghurt with imitation yoghurt fermentation by different lactic culture from soybean milk. An MSc Thesis submitted to Graduate faculty of Texas Technology University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree (MSc) in Food Technology.

- Mbaeyi-Nwaoha, I.E. and Iwezor-Godwin, L.C. (2015). Production and evaluation of yoghurt flavoured with fresh and dried cashew (Anacardium occidentale) apple pulp. African Journal of Food Science and Technology 6(8): 234. [CrossRef]

- Bristone Charles, Mamudu H. Badau, Joseph U. Igwebuike and Amin O. Igwegbe. 2015. Production and Evaluation of Yoghurt from Mixtures of Cow Milk, Milk Extract from Soybean and Tiger Nut. World Journal of Dairy & Food Sciences 10 (2): 159-169, 2015. ISSN 1817-308X.

- CSS (Conseil Supérieur de la Santé). (2009). Nutritional recommendations for Belgium. P (53).

- Raffo, A., Leonardi C., Fogliano V., Ambrosino P., Salucci M., Gennaro L., Bugianesi R., GiuffridaF.Quaglia G (2002). "Nutritional value of cherry tomatoes (Lycopersicumesculentum Cv Naomi F1) harvested at different ripening stages. "Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.22: 6550-6556. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F. and Ambigaipalan, P. (2015) Phenolics and Polyphenolics in Foods, Beverages and Spices: Antioxidant Activity and Health Effects—A Review. Journal of Functional Foods, 18, 820-897. [CrossRef]

- Carocho, M. and Ferreira, I.C.F. (2013) A Review on Antioxidants, Proxidants and Related Controversy: Natural and Synthetic Screening and Analysis Methodologies and Future Perspectives. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 51, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lo D., Wang H., Wu W., Yang R. (2018). Antinutrient components and their concentration in edible parts in vegetale families. ISSN 1749-8848.

- Adebooye, O, C, and Singh, V. (2010). Effect of processing on the oxalate and cyanide contents of some Nigerian indigenous Vegetables. Journal of food processing and presevation, 34(5), 803-815.

- Oboh, G. and Shodehinde S. A. (2009). Distribution of nutrients, polyphenols and antioxidant activities in the pilei and stipes of some commonly consumed edible mushrooms in Nigeria. Bulletin of Chemical Society of Ethiopia, 23 : 391-398.

- Duodu, K. G., Taylor, J. R., Belton, P. S., & Hamaker, B. R. (2002). Factors affecting sorghum protein digestibility. Journal of Cereal Science, 38(2), 117-13. [CrossRef]

- Ajebli, M., & Eddouks, M. (2019). The promising role of plant tannins as bioactive antidiabetic agents. Current medicinal chemistry, 26(25), 4852-4884. [CrossRef]

- Farha, A. K., Yang, Q. Q., Kim, G., Li, H. B., Zhu, F., Liu, H. Y., ... & Corke, H. (2020). Tannins as an alternative to antibiotics. Food Bioscience, 38, 100751.

- Hussain, G., Huang, J., Rasul, A., Anwar, H., Imran, A., Maqbool, J.,... & Sun, T. (2019). Putative roles of plant-derived tannins in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatry disorders: An updated review. Molecules, 24(12), 2213.

- Oly-alawuba, N. M., & Obiakor-Okeke, P. N. (2014). Evaluation of the anti-nutritional factors in some local spices consumed in Nigeria. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences, 3(6), 520-523.

- Sanchis, P., Lopez-Gonzalez, A. A., Costa-Bauza, A., Busquets-Cortes, C., Riutord, P., Calvo, P., et al. (2021). Understanding the protective effect of phytate in bone decalcification related-diseases. Nutrients 13, 2859. [CrossRef]

- Pires SMG, Reis RS, Cardoso SM, Pezzani R, Paredes-Osses E, Seilkhan A, Ydyrys A, Martorell M, Sönmez Gürer E, Setzer WN, Abdull Razis AF, Modu B, Calina D and Sharifi-Rad J (2023), Phytates as a natural source for health promotion: A critical evaluation of clinical trials. Front. Chem. 11:1174109. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., and Shamsher, S. K. (2018). Kidney stones: Mechanism of formation, pathogenesis and possible treatments. J. Biomol. Biochem, 2(1), 1-5.

- Munzur, M.M, Islam M.N, Akhtar S. and Islam M.R, (2004).Effect of different levels ofvegetable oils for the manufacture of Dahi from skim milk. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci., 17(7):1019-1025.

- Maillard, L. C. (1912). Action of amino acids on sugars: methodical formation of melanoidins by methodical means. C R Hebd. Séances Acad. Sci. 154, 66-68.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).