1. Introduction

The development and application of digital workflows in prosthetic dentistry have advanced significantly in recent years, particularly in the fabrication of removable complete dentures. Despite these technological innovations, most complete dentures are still produced using conventional methods, which involve multiple clinical sessions, extensive laboratory procedures, and considerable resource expenditure. These conventional processes are often characterized by multiple clinical appointments and different laboratory procedures, demanding considerable time and resources and incurring additional costs. Furthermore, the chosen workflow and the state of edentulism can substantially impact a patient’s quality of life and oral health. While digital workflows offer potential advantages, concerns persist regarding the feasibility and accuracy of acquiring intraoral scans of edentulous arches. Intraoral scanning, in such cases, presents complexities and necessitates a significant learning curve for practitioners.

Nevertheless, existing scientific literature indicates that digital dentures can achieve clinically acceptable values for occlusal plane correctness and adaptation. The final fabrication stage in a digital workflow can involve either milling or 3D printing techniques. These differing fabrication methods can influence complete dentures’ adaptation and retention and fracture resistance, surface roughness, biocompatibility, and aesthetics. Challenges inherent to intraoral scanning technology, particularly for edentulous patients, have prompted the exploration of alternative approaches. The smooth, translucent nature of intraoral mucosa, often covered with saliva, can lead to errors during the 3D model stitching process, thereby compromising the accuracy of the final digital model, especially in capturing intricate mucosal details. Moreover, while intraoral scanners effectively capture soft tissues without direct contact, they encounter difficulties obtaining functional impressions, particularly at the peripheral seal area crucial for defining the complete denture shape and size. Retracting lips for scanning labial areas can also introduce discrepancies between the scanned image and the actual vestibular dimensions. Consequently, while intraoral scanning can yield highly accurate prostheses on adherent mucosa, achieving proper adaptation on free mucosa in edentulous patients often remains problematic, potentially affecting the fit and comfort of the final prosthesis and limiting the utility of fully digital workflows in complex scenarios. In response to these limitations, a hybrid digital-conventional protocol has been developed to combine the precision of digital techniques with the reliability of conventional impression methods. This integrated approach seeks to mitigate inaccuracies inherent in exclusively digital procedures, particularly those involving mandibular impressions in severely atrophic cases. Therefore, the present study aims to systematically evaluate the clinical efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and patient-reported outcomes associated with this hybrid protocol.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective study enrolled 30 patients presenting with complete edentulism in both arches. Participants were recruited and received treatment between March 2023 and March 2025 at the Department of Dental and Maxillofacial Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome. Selection criteria included an age of over 65 years, a state of complete edentulism, and socioeconomic status.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Dental and Maxillofacial Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study and any study-related procedures in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Hybrid Digital Prosthetic Rehabilitation Protocol

The prosthetic rehabilitation protocol was designed to include the following sequential clinical and laboratory steps:

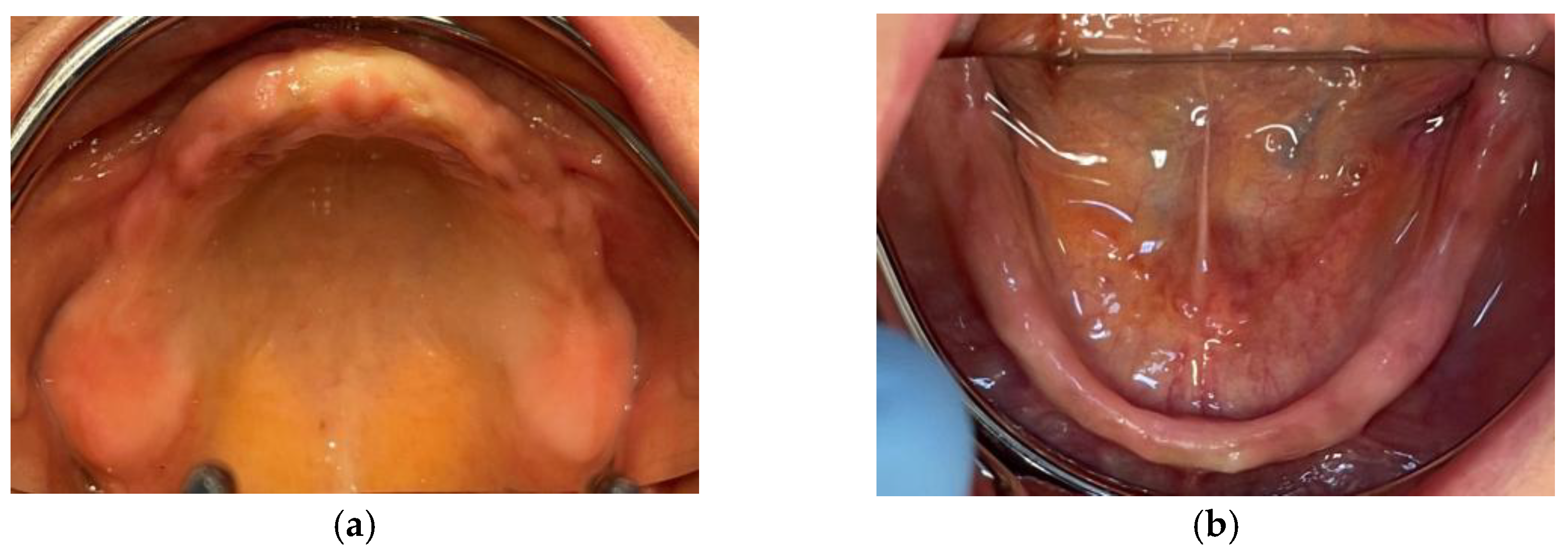

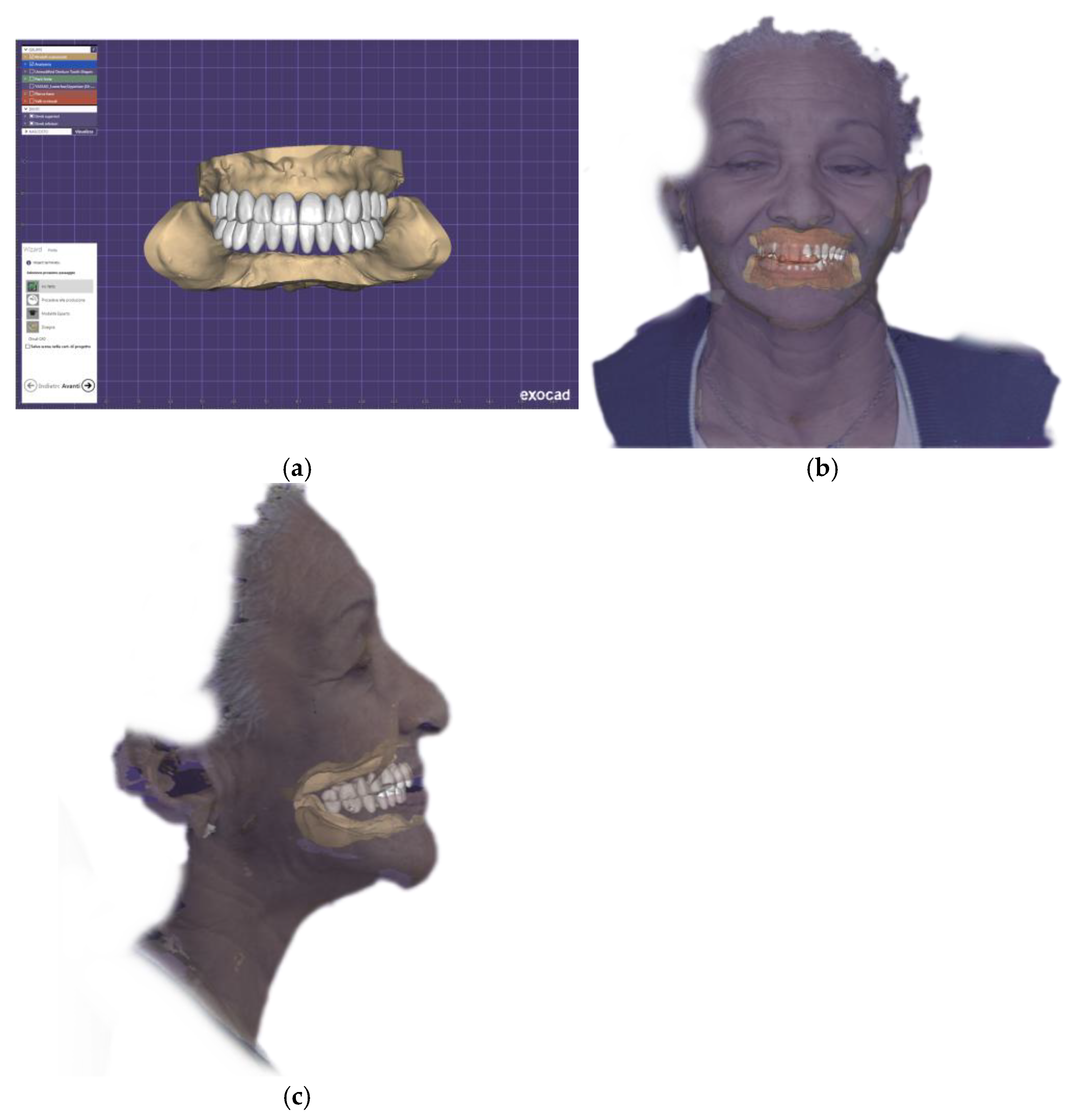

1) The first step of the prosthetic rehabilitation protocol involved extraoral and intraoral analysis of the patient’s face (

Figure 1), followed by intraoral assessment. Digital impressions of the edentulous maxillary and mandibular arches were acquired using the Medit i700 intraoral scanner (Medit Corp., Seoul, Korea).

The upper digital impression is recorded starting from landmarks, which are represented by the palatine wrinkles (

Figure 2a). The scanner tip must be positioned almost in contact with the intraoral surfaces that allows the correct registration of the mucosa and teeth. The edentulous ridges are then scanned by positioning the tip in an occlusal position and moving it outwards and inwards of the mouth until both the ridges and the labial and buccal vestibule are adequately recorded. To obtain digital scans of the vestibular areas, the scan was made after retracting the lips and cheeks with the scanner head while maximally stretching the vestibular area with a retractor [

1]. Furthermore, it is essential to record the entire hard palate up to the postdam, the reference limit on which the posterior prosthetic margin must reach.

2) The lower digital impression is always recorded, starting from the edentulous ridges, therefore with the tip directed occlusally, taking the labial or lingual frenulum as reference points for a better scan. The scan is then completed by recording the vestibular and lingual areas of the edentulous ridge, up to the retromolar trigone. A dermographic marker was used to create fixed reference points and facilitate the impression recording. Intraoral scanning was difficult in cases of particularly atrophic mandibular ridges, so an analog step had to be introduced into the digital workflow. In instances of severely atrophic mandibular ridges where achieving a stable and accurate full-arch intraoral scan proved difficult, a modified analog-digital approach was employed: a mucocompressive impression was made using alginate, and this impression was subsequently scanned directly with the intraoral scanner to create the digital model of the mandibular arch (

Figure 2b).

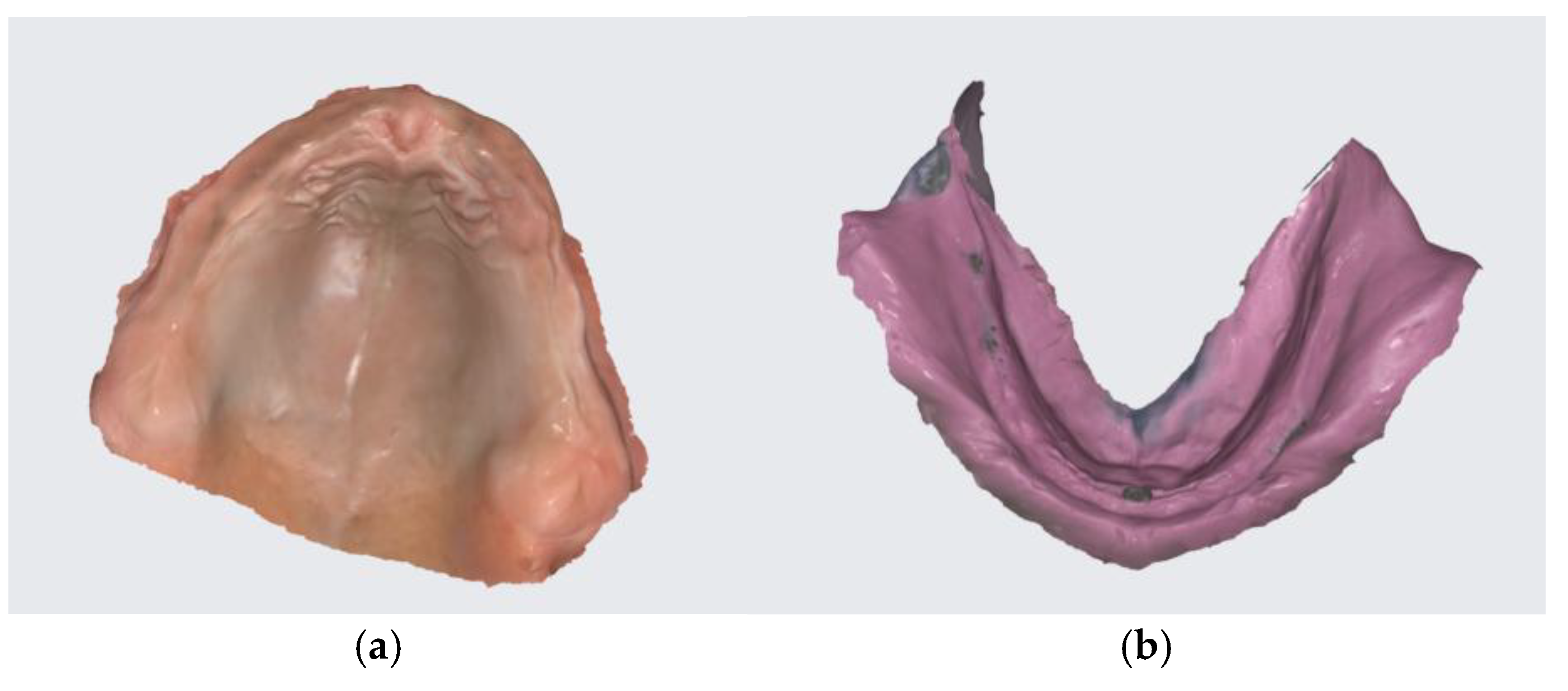

3) The acquired intraoral scan data were exported as Standard Tessellation Language (STL) files. Virtual models and centric registration bases were constructed based on these scans (

Figure 3).

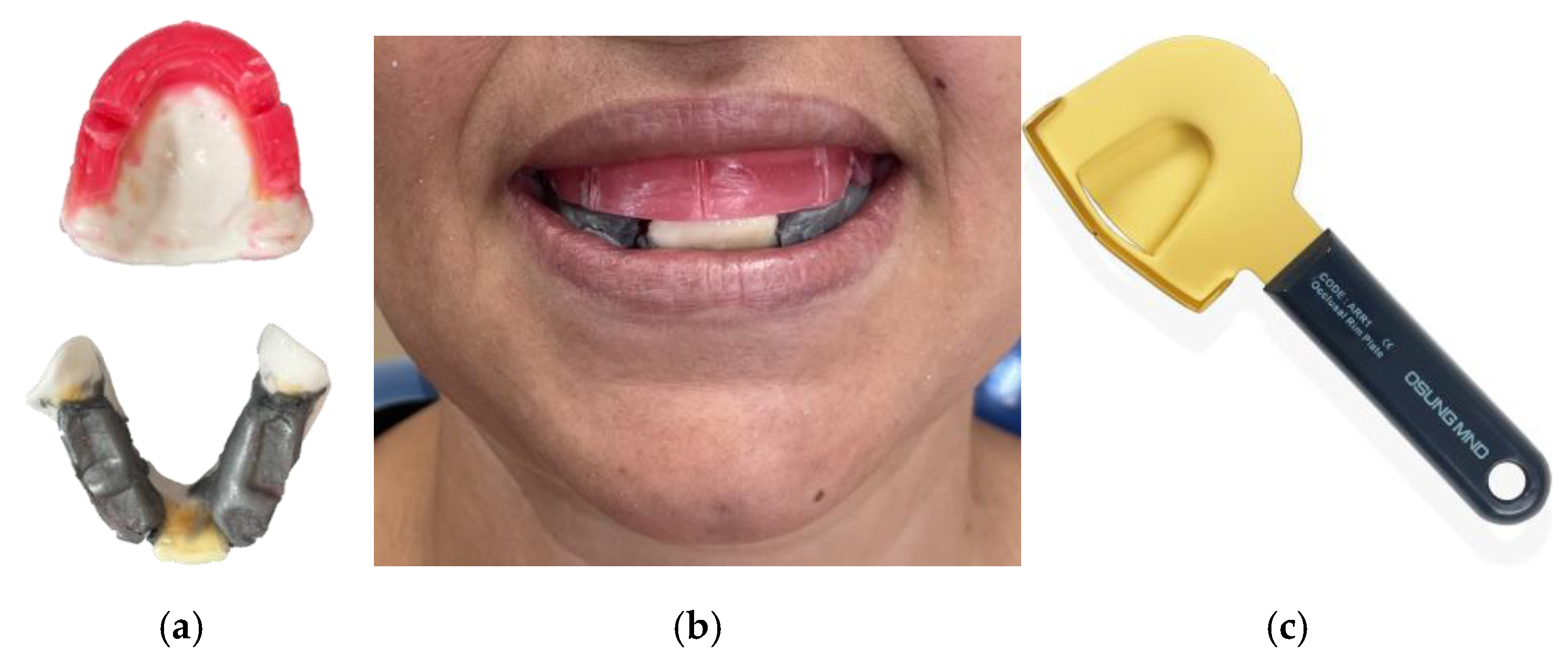

4) The vertex-centric registration bases are tested clinically (

Figure 4). The retention of the two articulations is initially assessed. The upper wax rim is discarded occlusally until an adequate height of the upper arch is determined with the help of the V and F phonemes test. The Rim occlusal inclinator is then heated to establish the inclination of the upper wax rim to be parallel to the Camper plane. The lower articulation base is positioned, the S phoneme test is performed, and the wax is discarded until pronounced correctly. Finally, notches are created on the upper wax rim in the posterior area, and the lower wax rim is heated in the posterior region to ensure the correct interlocking of the two rims that determine the previously established vertical dimension. To determine the interincisive line, the face’s midline and the nose’s tip are taken as a reference, while to record the canine bumps, the wings of the nose are referred to. The interzygomatic distance is also recorded with a caliper to help the technician choose the correct mesio-distal dimension of the frontal sector. The standard mesio-distal distance of the superior centrals is 1:16 of the interzygomatic distance [

2].

Although some studies report a ratio of 1:16 between the mesiodistal width of the central maxillary incisor and the interzygomatic distance, the available scientific evidence suggests that this ratio is not universal and may vary depending on the population and other factors. Therefore, it is advisable to use this ratio as a preliminary guide, adapting it to the specific characteristics of the patient [

3].

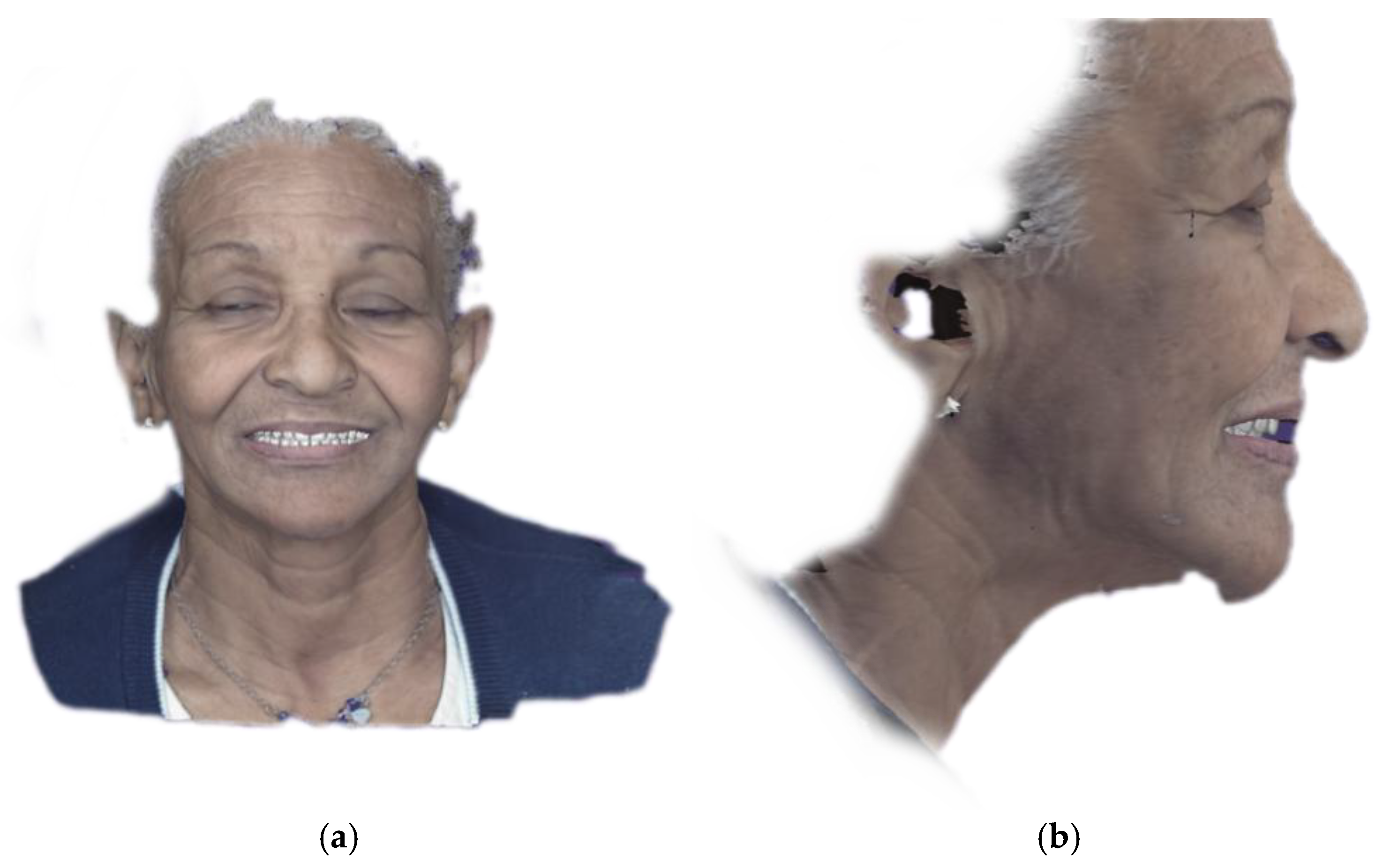

5) A 3D facial scan was acquired using a dedicated handheld facial scanner (MetiSmile; Shining 3D Tech Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). (

Figure 5) The facial scan was performed with the maxillary registration rim (incorporating the established occlusal plane and incisal edge position) seated intraorally. This procedure allowed for the subsequent superimposition and alignment of the intraoral scan data with the patient’s facial topography in the dental CAD software, facilitating a more aesthetically driven and patient-specific virtual tooth arrangement. This acquisition considered lip support, smile characteristics, and overall facial symmetry.

6) The STL files from the intraoral scans (or scanned impressions), the recorded maxillomandibular relationship, and the facial scan were integrated within the dental CAD software (Exocad DentalCAD, DentalCAD ULTIMATE Rjeka edition; Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). A complete 3D virtual patient model was thereby created.

The dental technician performed the virtual setup of denture teeth selected from a digital tooth library (e.g., VITA Physiodens, VITA Zahnfabrik H. Rauter GmbH & Co. KG, Bad Säckingen, Germany; or similar), arranging them according to the recorded occlusal parameters, esthetic requirements, and principles of complete denture occlusion. (

Figure 6) Tools within the software for analyzing occlusal contacts and excursive movements (virtual articulation) were utilized.

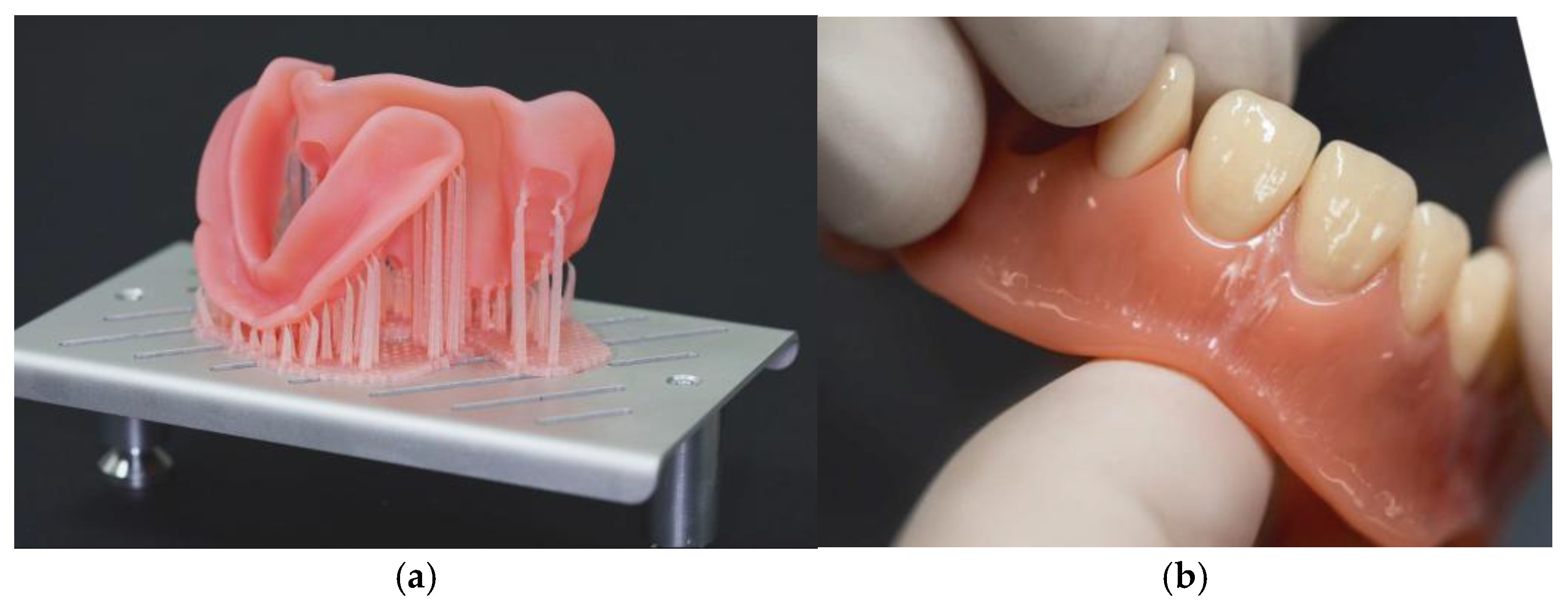

7) A monolithic resin prototype of the complete dentures was designed following a virtual esthetic preview and approval. This digital design (STL file) was then used to fabricate a physical prototype via 3D printing for clinical evaluation. (

Figure 7). Finally, the color of the dental elements is chosen based on the VITA color scale.

8) Based on the modifications identified and confirmed during the clinical prototype evaluation, the digital design was finalized in the CAD software. The definitive prosthetic bases were fabricated using a high-impact, esthetic denture base resin, 3D-printed using Digital Light Processing (DLP) technology with a specialized 3D printer (SolFlex 170 HD; Voco GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany) and a compatible photopolymerizing resin (V-Print dentbase; Voco GmbH) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for printing and post-curing. (

Figure 8a) Prefabricated, multi-layered acrylic resin denture teeth (VITA MFT) corresponding to the selected shade and molds were then bonded into the sockets of the 3D-printed denture bases using a dedicated PMMA-based adhesive system (V-Print C&B temp bond; Voco GmbH, or similar) following strict adherence to the manufacturer’s protocol for surface treatment and bonding. (

Figure 8b) The prostheses were then finished, polished, and delivered to the patient.

Follow-Up and Outcome Measures

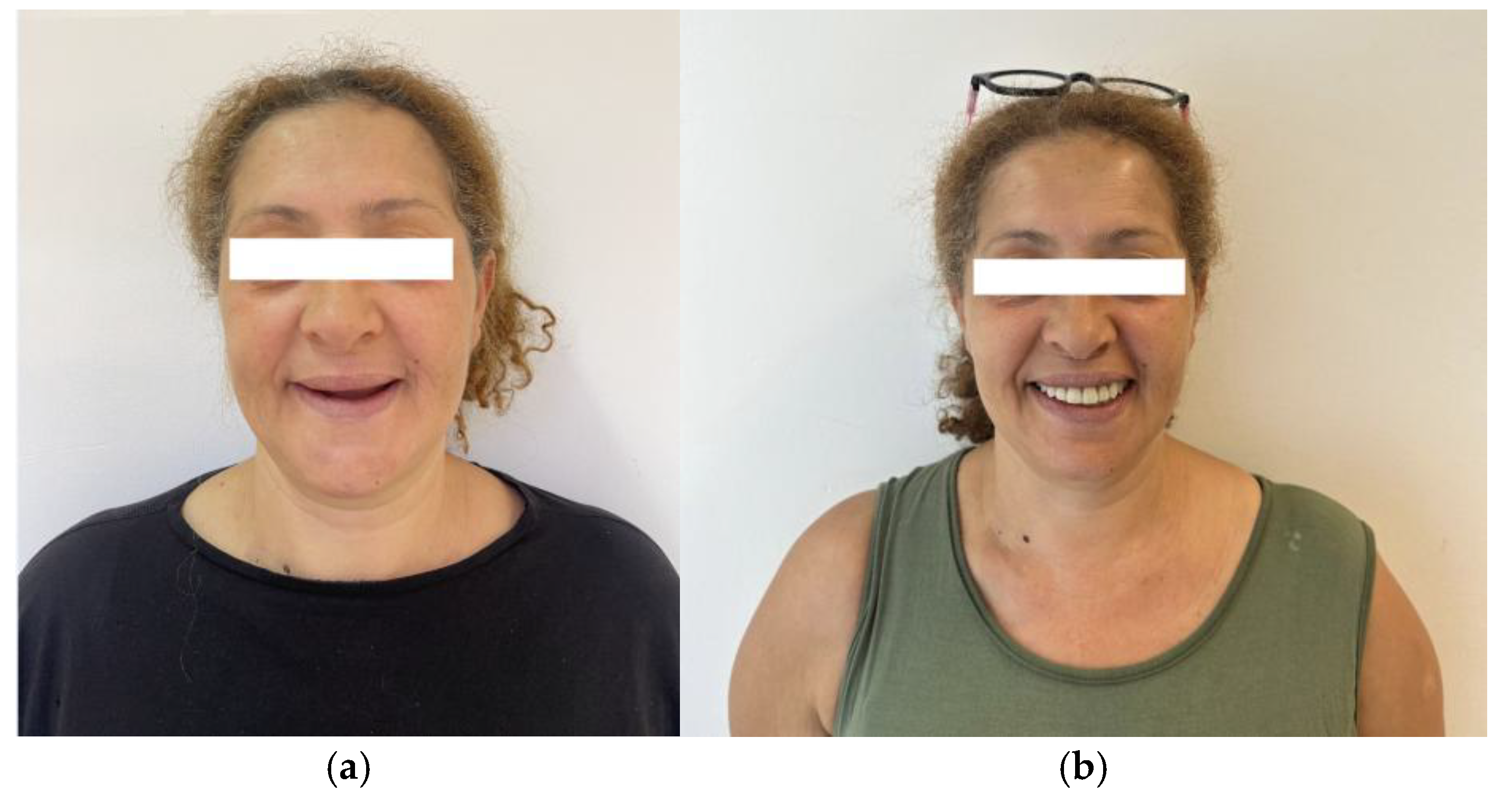

A follow-up appointment was scheduled approximately two weeks post-delivery to evaluate patient adaptation, comfort, masticatory function, speech, and the health of the supporting oral tissues. Any necessary minor adjustments to the denture borders or occlusion were performed. Subsequent follow-up appointments were arranged as clinically indicated throughout the 6-month initial observation period. (

Figure 9).

In addition, the GOHAI was administered to all participants by a trained interviewer at the initial baseline appointment (T0, before prosthetic rehabilitation) and again 3 months after the delivery and final adjustment of the new complete dentures (T1). The GOHAI is a 12-item self-reported questionnaire designed to evaluate an individual’s perception of their oral health and its impact on their quality of life across five dimensions: oral function (comfort while eating, talking, swallowing), appearance, pain or discomfort, and psychosocial impact (food restriction, self-consciousness, social interaction). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale indicating the frequency of an experience (e.g., never, seldom, sometimes, often, always). For consistent scoring, responses were coded from 1 (representing the most frequent negative experience or least frequent positive experience) to 5 (representing the least frequent negative experience or most frequent positive experience). GOHAI total scores were calculated by summing the scores for all 12 items, yielding a potential range from 12 (poorest perceived oral health) to 60 (best perceived oral health). For descriptive analysis and interpretation, GOHAI total scores were categorized based on established conventions as follows: 12-20 indicative of very poor perceived oral health, 21-30 poor, 31-40 moderate, 41-50 good and 51-60 excellent [

4].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR), were calculated for each variable. To evaluate the change in GOHAI scores from T0 to T1, the distribution of the difference scores (T1-T0) was first assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. As the assumption of normality for the paired differences was violated (Shapiro-Wilk test, p < .05), the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was employed to determine if there was a statistically significant median change in GOHAI scores following prosthetic rehabilitation. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

All 30 participants, each presenting with complete maxillary and mandibular edentulism, were successfully rehabilitated using the described hybrid digital-conventional protocol. The protocol typically required three to four clinical appointments for completion. The mean laboratory production time for each set of complete dentures (maxillary and mandibular) was 6.5 hours, with an average fabrication and delivery cost of €310 per unit. Each patient was followed for an initial clinical observation period of one month, which included two scheduled check-up visits.

During the 6-month post-delivery observation period, two patients experienced a fracture of their maxillary prosthesis; both fractures occurred between the central incisors. These prostheses were repaired, and no further instances of fracture were noted for these patients. No other major prosthesis-related clinical complications were recorded during this 6-month period. Some individuals reported minor transient mucosal discomfort, generally consistent with the adaptation phase to new dentures, particularly in those who had been edentulous for an extended duration without prior prosthetic rehabilitation.

Patient-reported outcomes, assessed using the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), revealed notable functional limitations and psychosocial impacts at baseline. For instance, prior to rehabilitation, a substantial proportion of participants reported frequently limiting their food choices (30% “very often,” 23.3% “always”) and experiencing difficulty chewing harder foods (30.0% “very often,” 33.3% “always”). Difficulty in swallowing was also prevalent, with 30.0% reporting it “always” and 20.0% “very often.” A considerable number of patients (46.7%) were “never” satisfied with their dental appearance pre-treatment, and 46.7% reported “regularly” feeling nervous or embarrassed due to their dental condition.

The mean GOHAI score for the study population before prosthetic rehabilitation (T0) was 36.86±4.21 (range: 29–43). Following 3 months after the delivery and adjustment of the new dentures (T1), the mean GOHAI score increased to 41.05±5.66 (range: 27–47). This change indicates a statistically significant improvement in the cohort’s perceived oral health-related quality of life (p=0.024). However, some residual challenges persisted, including limited dissatisfaction with aesthetics and minor functional discomfort.

4. Discussion

The present clinical study described and evaluated a hybrid digital-conventional protocol for the fabrication of removable complete dentures, focusing on clinical efficiency, economic aspects, and patient-reported outcomes. The findings indicated that this hybrid approach required fewer clinical appointments (3-4 visits) and demonstrated efficient laboratory production times (approximately 6.5 hours) with a comparatively lower fabrication cost (€310 per unit) when compared to normative data for conventional workflows. Furthermore, a statistically significant improvement in patients’ perceived oral health-related quality of life, as measured by the GOHAI, was observed following prosthetic rehabilitation with this protocol.

The hybrid protocol was primarily chosen to overcome the difficulties of intraoral scanning for completely edentulous mandibular arches, especially in cases involving severe residual ridge atrophy. The decision to integrate a conventional mucocompressive alginate impression for the mandibular arch, which was subsequently digitized, aimed to combine the predictable tissue displacement of a conventional technique for enhanced retention with the efficiencies of the digital workflow. This approach aligns with observations by Lo Russo et al. [

5], who suggested that while mucostatic impressions (typical of direct intraoral scans) might favor long-term ridge preservation, mucocompressive techniques may yield superior initial retention. The influence of saliva and tissue mobility during direct scanning, especially in the mandible, can lead to inaccuracies [

6], further justifying the selective use of an analog impression step for this arch in challenging cases. This integration underscores a current practical limitation of fully digital workflows and illustrates the adaptability of combining methodologies to optimize results.

This study’s outcomes are comparable to those reported in the literature concerning CAD-CAM complete dentures. A systematic review by Srinivasan et al. [

7] indicated that CAD-CAM complete dentures generally demonstrate improved mechanical properties and are not inferior to conventionally fabricated dentures across multiple assessed parameters. The requirement of 3-4 clinical visits in the present study improves the 5-7 visits commonly associated with conventional denture fabrication protocols. Their laboratory time of 6.5 hours noted in this study is also less than the approximate 9 hours often reported for conventional methods [

7]. These findings are shown by Deng et al. [

8], who reported average time savings of 28.0 minutes clinically and 64.3 minutes in the laboratory with a digital complete denture protocol. Similarly, Peroz et al. [

9] documented a reduction in appointments (2 for digital versus 5 for conventional) and significantly shorter fabrication times (4 hours for digital compared to 10.5 for conventional). The production cost of €310 per prosthesis observed in this study aligns with meta-analyses suggesting that CAD-CAM complete dentures incur lower overall costs than traditional fabrication methods [

10]. The main factor affecting this difference is the cost of skilled labour, which is approximately 36% lower in the digital process, from €280.00 to €180.00. This figure suggests that the use of digital flows, including intraoral scanning, CAD design and CAM production, allows a significant optimisation of the time and human resources required, reducing manual intervention. In contrast, material-related expenses (such as prefabricated teeth and resin for palates) and general operating costs do not vary significantly between the traditional and digital methods. This indicates that the economic efficiency of the digital method is closely linked to a reduction in manual labour and not necessarily to savings on consumables. These data are consistent with a study by the University of Siena, in which the authors reveal a price difference between the production costs of traditional and digital prostheses, similar to that found in our study. Indeed the authors reveal that the production costs of traditional prostheses are higher than those of prostheses made with digital technologies [

11].

The statistically significant improvement in mean GOHAI scores post-rehabilitation (from 36.86±4.21 to 41.05±5.66) effectively demonstrates the positive impact of the dentures fabricated using the hybrid protocol on patients’ perceived oral health and functional well-being. The observed increase in GOHAI scores suggests that the prostheses addressed many pre-existing patient-reported limitations concerning eating, speaking, and social interaction, thereby contributing positively to psychological well-being and self-perception [

12]. Nevertheless, some patients continued to experience minor discomfort or express aesthetic concerns; such occurrences are not uncommon during the adaptation period to new prostheses and may also be influenced by individual patient expectations or specific anatomical complexities.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. The sample size (N=30), while offering initial clinical data, represents a relatively modest sample size, potentially restricting the broader generalizability of the results. Furthermore, an extended follow-up period beyond the reported 6 months would be advantageous for evaluating the long-term clinical performance of the prostheses, including aspects such as wear resistance and the sustained stability of patient satisfaction. Additionally, the present study assessed a hybrid workflow that incorporated specific materials, scanning technologies, computer-aided design software, and 3D printing systems. A variation in any of these components—such as different intraoral scanner models, alternative CAD platforms, different 3D printing technologies, or other formulations of denture base resins—could potentially yield different clinical and patient-reported outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the evaluated hybrid digital-conventional protocol for the fabrication of complete removable dentures demonstrated clinical efficacy and offered notable benefits regarding treatment efficiency and patient-reported outcomes. Integrating digital scanning and design with selective conventional laboratory procedures resulted in a workflow characterized by reduced patient appointments and efficient laboratory production times.

Furthermore, prosthetic rehabilitation using this hybrid approach was associated with statistically significant improvements in participants’ perceived oral health-related quality of life. These findings suggest that the described hybrid protocol represents an effective treatment modality for completely edentulous patients.

References

- Fang, J.H.; An, X.; Jeong, S.M.; Choi, B.H. Digital immediate denture: A clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonanno, U. (2016). I denti umani. Tavole-Disegno tecnico. Per le scuole superiori. Con e-book. Con espansione online. La forma (Vol. 1). SAB Edizioni.

- Radia S, Sherriff M, McDonald F, Naini FB. Relationship between maxillary central incisor proportions and facial proportions. J Prosthet Dent. 2016 Jun;115(6):741-8.

- Denis, F.; Hamad, M.; Trojak, B.; Tubert-Jeannin, S.; Rat, C.; Pelletier, J.F.; Rude, N. Psychometric characteristics of the “General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI)” in a French representative sample of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, R.; Ruggiero, G.; Leone, R.; Di Mauro, M.I.; Cagidiaco, E.F.; Joda, T.; Lo Russo, L.; Zarone, F. Influence of different palatal morphologies on the accuracy of intraoral scanning of the edentulous maxilla: A three-dimensional analysis. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2024, 68, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahya Karaca, S.; Akca, K. Comparison of conventional and digital impression approaches for edentulous maxilla: Clinical study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, M.; Kamnoedboon, P.; McKenna, G.; Angst, L.; Schimmel, M.; Özcan, M.; Müller, F. CAD-CAM removable complete dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trueness of fit, biocompatibility, mechanical properties, surface characteristics, color stability, time-cost analysis, clinical and patient-reported outcomes. J. Dent. 2021, 113, 103777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y. Comparison of treatment outcomes and time efficiency between a digital complete denture and conventional complete denture: A pilot study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peroz, S.; Peroz, I.; Beuer, F.; Sterzenbach, G.; von Stein-Lausnitz, M. Digital versus conventional complete dentures: A randomized, controlled, blinded study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarpour, D.; Haricharan, P.B.; de Souza, R.F. CAD/CAM versus traditional complete dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient- and clinician-reported outcomes and costs. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 1911–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casucci A, Ferrari Cagidiaco E, Verniani G, Ferrari M, Borracchini A. Digital vs. conventional removable complete dentures: A retrospective study on clinical effectiveness and cost-efficiency in edentulous patients: Clinical effectiveness and cost-efficiency analysis of digital dentures. J Dent. 2025 Feb;153:105505.

- De Carvalho, B.M.D.F.; Parente, R.C.; Franco, J.M.P.L.; Silva, P.G.B. GOHAI and OHIP-EDENT Evaluation in Removable Dental Prostheses Users: Factorial Analysis and Influence of Clinical and Prosthetic Variables. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).