Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

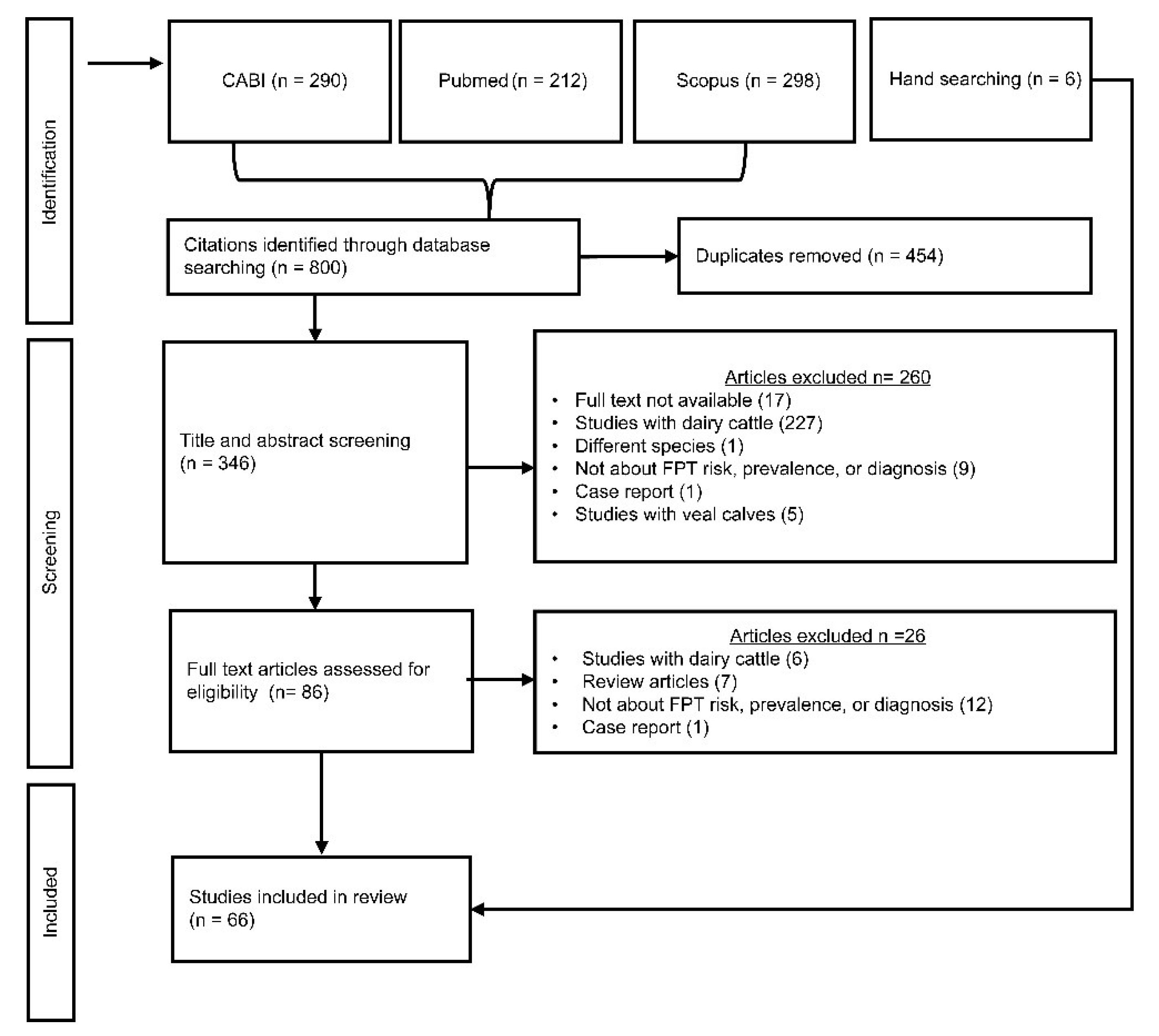

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening Processes

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

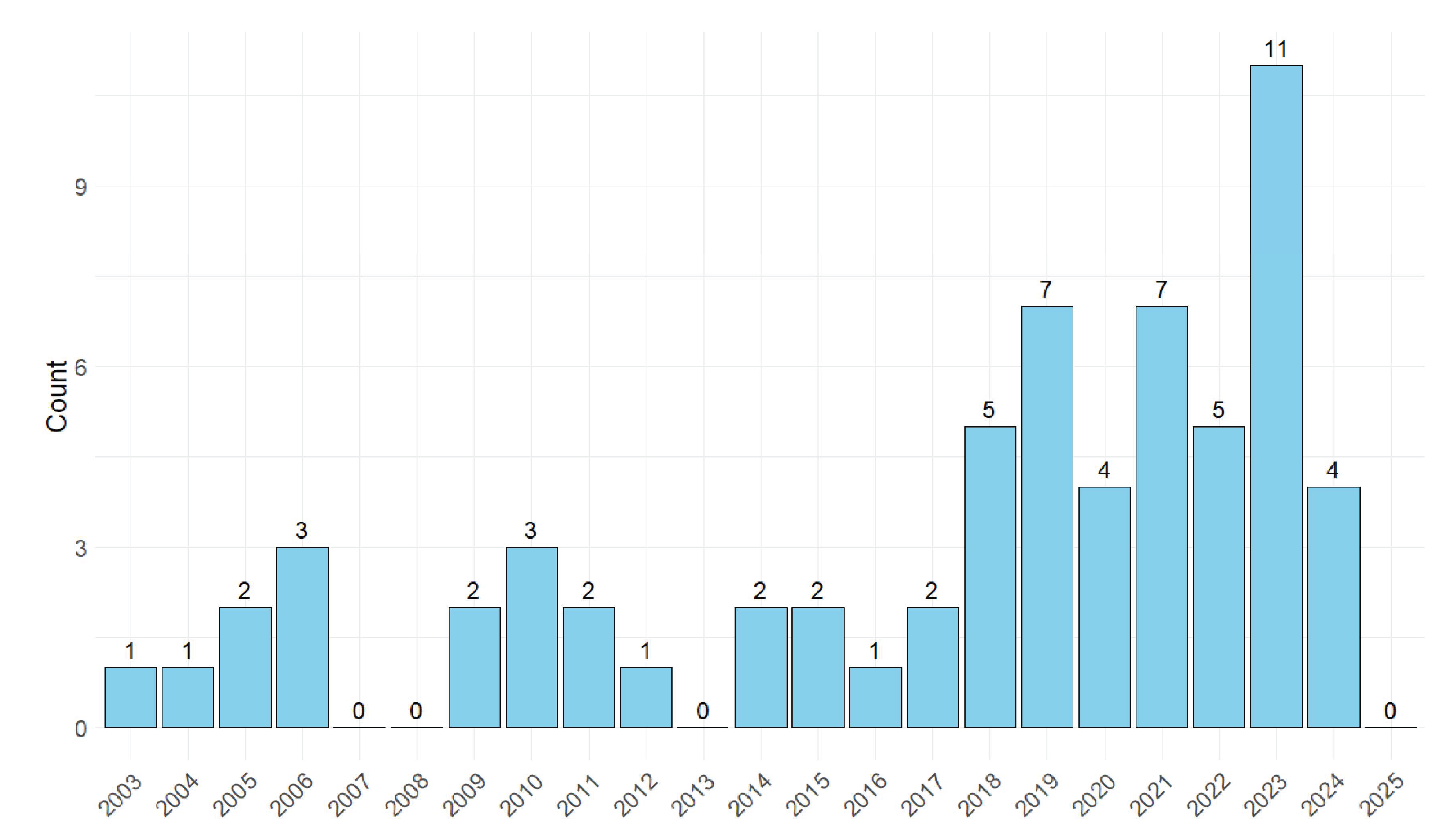

3.1. Descriptive Summaries

3.2. Prevalence Estimates of FPT in Beef Calves

3.3. Association Between FPT and Calf Health Outcomes

3.4. Factors Related to Colostrum Management

3.4.1. Colostrum Quantity or Volume

3.4.2. Colostrum Quality (IgG Concentration or Source)

3.4.3. Timing of Colostrum Feeding

3.4.4. Method of Colostrum Feeding

3.4.5. Microbial Content of Colostrum

3.5. Factors Related to Calves

3.5.1. Calf Sex or Twin Status

3.5.2. Calf Vigor at Birth

3.5.3. Reproductive Technologies Used at Breeding

3.5.4. Calf Birthweight

3.5.5. Month of Birth

3.5.6. Calf Cortisol and Epinephrine Levels

3.6. Factors Related to Dams

3.6.1. Dam Body Condition Score or Udder Conformation

3.6.2. Dam Breed

3.6.3. Dam Prepartum Vaccination

3.6.4. Dam Parity

3.6.5. Dam Prepartum Nutrition

3.6.6. Calving Area

3.6.7. Calving Difficulty

3.6.8. Genetics and Heritability

3.7. Methods of FPT Detection in Beef Calves

4. Discussion

Prevalence of FPT and Associations with Health Outcomes

4.1. Calf-Related Risk Factors

Colostrum Management

Calf Sex, Twin Status, Birthweight

4.2. Dam Related Factors

4.2.1. Dam Breed, and Body Condition

Calving Difficulty

4.2.2. Dam Nutrition

4.2.3. Dam Prepartum Vaccination

4.2.4. Genetics and Heritability

4.1.2. Methodology to Assess FPT in Beef Calves

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cortese, V.S. Neonatal Immunology. Veter- Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pr. 2009, 25, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrill, K.; Conrad, E.; Lago, A.; Campbell, J.; Quigley, J.; Tyler, H. Nationwide evaluation of quality and composition of colostrum on dairy farms in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3997–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J.; Otterby, D. Availability, Storage, Treatment, Composition, and Feeding Value of Surplus Colostrum: A Review. J. Dairy Sci. 1978, 61, 1033–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, G.; Marx, D.; Menefee, B.; Nightengale, G. Colostral Immunoglobulin Transfer in Calves I. Period of Absorption. J. Dairy Sci. 1979, 62, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.E. Bovine Immunoglobulins: A Review. J. Dairy Sci. 1969, 52, 1895–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, M.L.; Heaton, M.P.; Chitko-McKown, C.G.; Fox, J.M.; Smith, T.P.L.; Snelling, W.M.; Keele, J.W.; Laegreid, W.W. Beta-2-microglobulin haplotypes in U.S. beef cattle and association with failure of passive transfer in newborn calves. Mamm. Genome 2004, 15, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewell, R.D.; Hungerford, L.L.; Keen, J.E.; Laegreid, W.W.; Griffin, D.D.; Rupp, G.P.; Grotelueschen, D.M. Association of neonatal serum immunoglobulin G1 concentration with health and performance in beef calves. J. Am. Veter- Med Assoc. 2006, 228, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, R.; Macrae, A.; Lycett, S.; Burrough, E.; Russell, G.; Corbishley, A. Prevalence and risk factors associated with failure of transfer of passive immunity in spring born beef suckler calves in Great Britain. Prev. Veter- Med. 2020, 181, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.; Stott, G.; DeNise, S. Effects of Passive Immunity on Growth and Survival in the Dairy Heifer. J. Dairy Sci. 1988, 71, 1283–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, R. Generic antibiotics, antibiotic resistance, and drug licensing. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboisson, D.; Trillat, P.; Dervillé, M.; Cahuzac, C.; Maigné, E.; Loor, J.J. Defining health standards through economic optimisation: The example of colostrum management in beef and dairy production. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0196377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyama, T.; Kelton, D.F.; Winder, C.B.; Dunn, J.; Goetz, H.M.; LeBlanc, S.J.; McClure, J.T.; Renaud, D.L.; Yildirim, A. Colostrum management practices that improve the transfer of passive immunity in neonatal dairy calves: A scoping review. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.; Glasziou, P.; Del Mar, C.; Bannach-Brown, A.; Stehlik, P.; Scott, A.M. A full systematic review was completed in 2 weeks using automation tools: a case study. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2020, 121, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filteau, V.; Bouchard, E.; Fecteau, G.; Dutil, L.; DuTremblay, D. Health status and risk factors associated with failure of passive transfer of immunity in newborn beef calves in Québec. . 2003, 44, 907–13. [Google Scholar]

- Waldner, C.L.; Rosengren, L.B. Factors associated with serum immunoglobulin levels in beef calves from Alberta and Saskatchewan and association between passive transfer and health outcomes. . 2009, 50, 275–81. [Google Scholar]

- O’sHaughnessy, J.; Earley, B.; Barrett, D.; Doherty, M.L.; Crosson, P.; de Waal, T.; Mee, J.F. Disease screening profiles and colostrum management practices on 16 Irish suckler beef farms. Ir. Veter- J. 2015, 68, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustronck, B.; Hoflack, G.; Lebrun, M.; Vertenten, G. Bayesian latent class analysis of the characteristics of diagnostic tests to assess the passive immunity transfer status in neonatal Belgian Blue beef calves. Prev. Veter- Med. 2022, 207, 105729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, F.; Joulié, A.; Herry, V.; Masset, N.; Lemaire, G.; Barral, A.; Raboisson, D.; Roy, C.; Herman, N. Failure of Passive Immunity Transfer Is Not a Risk Factor for Omphalitis in Beef Calves. Veter- Sci. 2023, 10, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, R.; Corbishley, A.; Lycett, S.; Burrough, E.; Russell, G.; Macrae, A. Effect of neonatal immunoglobulin status on the outcomes of spring-born suckler calves. Veter- Rec. 2023, 192, e2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsjäger, L.; Haines, D.M.; Lévy, M.; Pajor, E.A.; Campbell, J.R.; Windeyer, M.C. Total and pathogen-specific serum Immunoglobulin G concentrations in neonatal beef calves, Part 2: Associations with health and growth. Prev. Veter- Med. 2023, 220, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Vinet, A.; Denis, C.; Grohs, C.; Chanteloup, L.; Dozias, D.; Maupetit, D.; Sapa, J.; Renand, G.; Blanc, F. Determination of immunoglobulin concentrations and genetic parameters for colostrum and calf serum in Charolais animals. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, C.; McGee, M.; Tiernan, K.; Crosson, P.; O’rIordan, E.; McClure, J.; Lorenz, I.; Earley, B. An observational study on passive immunity in Irish suckler beef and dairy calves: Tests for failure of passive transfer of immunity and associations with health and performance. Prev. Veter- Med. 2018, 159, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamsjäger, L.; Haines, D.; Pajor, E.; Lévy, M.; Windeyer, M. Impact of volume, immunoglobulin G concentration, and feeding method of colostrum product on neonatal nursing behavior and transfer of passive immunity in beef calves. Animal 2021, 15, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, M.F.; Saucedo, M.; Gamsjaeger, L.; Reppert, E.J.; Miesner, M.; Passler, T. Colostrum Replacement and Serum IgG Concentrations in Beef Calves Delivered by Elective Cesarean Section. Veter- Sci. 2024, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Kim, S.; Hwangbo, D.; Oh, Y.; Yu, J.; Bae, J.; Kim, N.Y. Performance of Hanwoo calves fed a commercial colostrum replacer versus natural bovine colostrum. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homerosky, E.; Timsit, E.; Pajor, E.; Kastelic, J.; Windeyer, M. Predictors and impacts of colostrum consumption by 4 h after birth in newborn beef calves. Veter- J. 2017, 228, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.M.; Pajor, E.; Campbell, J.; Levy, M.; Caulkett, N.; Windeyer, M.C. A randomised controlled trial investigating the effects of administering a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug to beef calves assisted at birth and risk factors associated with passive immunity, health, and growth. Veter- Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, L.; Sala, G.; Rueca, F.; Passamonti, F.; Pravettoni, D.; Ranciati, S.; Boccardo, A.; Bergero, D.; Forte, C. An exploratory cross-sectional study of the impact of farm characteristics and calf management practices on morbidity and passive transfer of immunity in 202 Chianina beef-suckler calves. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, M.; Drennan, M.J.; Caffrey, P.J. Effect of Age and Nutrient Restriction Pre Partum on Beef Suckler Cow Serum Immunoglobulin Concentrations, Colostrum Yield, Composition and Immunoglobulin Concentration and Immune Status of Their Progeny. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research 2006, 45, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenta-Oliveira, A.; Oliveira-Filho, J.P.; Dias, A.; Gonçalves, R.C. Morbidity-mortality and performance evaluation of Brahman calves from in vitro embryo production. BMC Veter- Res. 2011, 7, 79–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hese, I.; Goossens, K.; Ampe, B.; Haegeman, A.; Opsomer, G. Exploring the microbial composition of Holstein Friesian and Belgian Blue colostrum in relation to the transfer of passive immunity. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7623–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavirani, S.; Gambetti, C.; Schiano, E.; Casaletti, E.; Spadini, C.; Mezzasalma, N.; Cabassi, C.S.; Taddei, S. Comparison of Immunoglobulin G Concentrations in Colostrum and Newborn Calf Serum from Animals of Different Breeds, Parity and Gender. Large Animal Review 2024, 30, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Waldner, C.L.; Rosengren, L.B. Factors associated with serum immunoglobulin levels in beef calves from Alberta and Saskatchewan and association between passive transfer and health outcomes. . 2009, 50, 275–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J.M.; Homerosky, E.R.; A Caulkett, N.; Campbell, J.R.; Levy, M.; A Pajor, E.; Windeyer, M.C. Quantifying subclinical trauma associated with calving difficulty, vigour, and passive immunity in newborn beef calves. Veter- Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, N.C.; Banta, J.P.; Neuendorff, D.A.; White, J.C.; Vann, R.C.; Laurenz, J.C.; Welsh, T.H.; Randel, R.D. Interrelationships among growth, endocrine, immune, and temperament variables in neonatal Brahman calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 3202–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, S.L.; Scholljegerdes, E.J.; Small, W.T.; Belden, E.L.; Paisley, S.I.; Rule, D.C.; Hess, B.W. Immune response and serum immunoglobulin G concentrations in beef calves suckling cows of differing body condition score at parturition and supplemented with high-linoleate or high-oleate safflower seeds1. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RE, H.; PJ, B.; NP, M.; PR, K.; ST, M. The Influence of Age and Breed of Cow on Colostrum Indicators of Suckled Beef Calves. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the New Zealand Society of Animal Production.

- E Altvater-Hughes, T.; Hodgins, D.C.; Wagter-Lesperance, L.; Beard, S.C.; Cartwright, S.L.; A Mallard, B. Concentration and heritability of immunoglobulin G and natural antibody immunoglobulin M in dairy and beef colostrum along with serum total protein in their calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, N.; McGee, M.; Beltman, M.; Byrne, C.J.; Meredith, D.; Earley, B. Effect of suckler cow breed type and parity on the development of the cow-calf bond post-partum and calf passive immunity. Ir. Veter- J. 2024, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, R.E.; Back, P.J.; Martin, N.P.; Kenyon, P.R.; Morris, S.T. The Influence of Age and Breed of Cow on Colostrum Indicators of Suckled Beef Calves. Proceedings of the New Zealand Society of Animal Production 76, 163–168.

- McGee, M.; Drennan, M.J.; Caffrey, P.J. Effect of Suckler Cow Genotype on Cow Serum Immunoglobulin (Ig) Levels, Colostrum Yield, Composition and Ig Concentration and Subsequent Immune Status of Their Progeny. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research 44, 173–183.

- Murphy, B.M.; Drennan, M.J.; O’Mara, F.P.; Earley, B. Cow Serum and Colostrum Immunoglobulin (IgGj) Concentration of Five Suckler Cow Breed Types and Subsequent Immune Status of Their Calves. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research 44, 205–213.

- Earley, B.; Tiernan, K.; Duffy, C.; Dunn, A.; Waters, S.; Morrison, S.; McGee, M. Effect of suckler cow vaccination against glycoprotein E (gE)-negative bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1) on passive immunity and physiological response to subsequent bovine respiratory disease vaccination of their progeny. Res. Veter- Sci. 2018, 118, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, F.A.; Decaris, N.; Parreño, V.; Brandão, P.E.; Ayres, H.; Gomes, V. Efficacy of prepartum vaccination against neonatal calf diarrhea in Nelore dams as a prevention measure. BMC Veter- Res. 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppert, E.J.; Chamorro, M.F.; Robinson, L.; Cernicchiaro, N.; Wick, J.; Weaber, R.L.; Haines, D.M. Effect of vaccination of pregnant beef heifers on the concentrations of serum IgG and specific antibodies to bovine herpesvirus 1, bovine viral diarrhea virus 1, and bovine viral diarrhea virus 2 in heifers and calves. 2019, 83, 313–316.

- Stegner, J.; Alaniz, G.; Meinert, T.; Gallo, G.; Cortese, V. Passive Transfer of Antibodies in Pregnant Cattle Following Vaccination with Bovi-Shield®. Am. Assoc. Bov. Pr. Conf. Proc. 2010, 250–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curci, V.; Nogueira, A.; Nobrega, F.; Araujo, R.; Perri, S.; Cardoso, T.; Dutra, I. Neonatal immune response of Brazilian beef cattle to vaccination with Clostridium botulinum toxoids types C and D by indirect ELISA. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 16, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsjäger, L.; Haines, D.M.; Lévy, M.; Pajor, E.A.; Campbell, J.R.; Windeyer, M.C. Total and pathogen-specific serum Immunoglobulin G concentrations in neonatal beef calves, Part 1: Risk factors. Prev. Veter- Med. 2023, 220, 106026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsjäger, L.; Haines, D.M.; Lévy, M.; Pajor, E.A.; Campbell, J.R.; Windeyer, M.C. Total and pathogen-specific serum Immunoglobulin G concentrations in neonatal beef calves, Part 2: Associations with health and growth. Prev. Veter- Med. 2023, 220, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, T.G.; Nociti, R.P.; Sampaio, A.A.M.; Fagliari, S.J. Passive Immunity Transfer and Serum Constituents of Crossbred Calves. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileiravol. 32issue 6(2012)pp: 515-522Published by Colégio Brasileiro de Patologia Animal - CBPA.

- Noya, A.; Casasús, I.; Ferrer, J.; Sanz, A. Long-Term Effects of Maternal Subnutrition in Early Pregnancy on Cow-Calf Performance, Immunological and Physiological Profiles during the Next Lactation. Animals 2019, 9, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichman, L.G.; A Redifer, C.; Meyer, A.M. Maternal nutrient restriction during late gestation reduces vigor and alters blood chemistry and hematology in neonatal beef calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperson, K.D.; Vorachek, W.R.; Dolan, B.P.; Bobe, G.; Pirelli, G.J.; Hall, J.A. Effects of feeding pregnant beef cows selenium-enriched alfalfa hay on passive transfer of ovalbumin in their newborn calves. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2018, 50, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.G.; Bobe, G.; Vorachek, W.R.; Dolan, B.P.; Estill, C.T.; Pirelli, G.J.; Hall, J.A. Effects of feeding pregnant beef cows selenium-enriched alfalfa hay on selenium status and antibody titers in their newborn calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 2408–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks, R.; Cook, E.; Long, N. Effects of supplementing ruminal-bypass unsaturated fatty acids during late gestation on beef cow and calf serum and colostrum fatty acids, transfer of passive immunity, and cow and calf performance. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 36, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.F.P.; Muller, J.; Cavalieri, J.; Fordyce, G.; Chauhan, S. Immediate prepartum supplementation accelerates progesterone decline, boosting passive immunity transfer in tropically adapted beef cattle. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2022, 62, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtas, E.; Zachwieja, A.; Piksa, E.; Zielak-Steciwko, A.E.; Szumny, A.; Jarosz, B. Effect of Soy Lecithin Supplementation in Beef Cows before Calving on Colostrum Composition and Serum Total Protein and Immunoglobulin G Concentrations in Calves. Animals 2020, 10, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, V.C.; Gaspers, J.J.; Mordhorst, B.R.; Stokka, G.L.; Swanson, K.C.; Bauer, M.L.; A Vonnahme, K. Late gestation supplementation of corn dried distiller’s grains plus solubles to beef cows fed a low-quality forage: III. effects on mammary gland blood flow, colostrum and milk production, and calf body weights. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 3337–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linneen, S.; Mourer, G.; Sparks, J.; Jennings, J.; Goad, C.; Lalman, D. Effects of mannan oligosaccharide on beef-cow performance and passive immunity transfer to calves. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2014, 30, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M.J.; Van Emon, M.L.; Gunn, P.J.; Eicher, S.D.; Lemenager, R.P.; Burgess, J.; Pyatt, N.; Lake, S.L. Effects of maternal natural (RRR α-tocopherol acetate) or synthetic (all-rac α-tocopherol acetate) vitamin E supplementation on suckling calf performance, colostrum immunoglobulin G, and immune function. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 3128–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, J.L.; Baumgaertner, F.; Bochantin-Winders, K.A.; Jurgens, I.M.; Sedivec, K.K.; Dahlen, C.R. Effects of Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation During Gestation in Beef Heifers on Immunoglobulin Concentrations in Colostrum and Immune Responses in Naturally and Artificially Reared Calves. Veter- Sci. 2024, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, E.L.; Rathert-Williams, A.R.; Kenny, A.L.; Nagy, D.W.; Shoemake, B.M.; McFadden, T.B.; A Tucker, H.; Meyer, A.M. Effects of copper, zinc, and manganese source and inclusion during late gestation on beef cow–calf performance, mineral transfer, and metabolism. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 7, txad097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Vinet, A.; Denis, C.; Grohs, C.; Chanteloup, L.; Dozias, D.; Maupetit, D.; Sapa, J.; Renand, G.; Blanc, F. Determination of immunoglobulin concentrations and genetic parameters for colostrum and calf serum in Charolais animals. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Mukiibi, R.; Waters, S.M.; McGee, M.; Surlis, C.; McClure, J.C.; McClure, M.C.; Todd, C.G.; Earley, B. Genome wide association study of passive immunity and disease traits in beef-suckler and dairy calves on Irish farms. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akköse, M.; Buczinski, S.; Özbeyaz, C.; Kurban, M.; Cengiz, M.; Polat, Y.; Aslan, O. Diagnostic accuracy of refractometry methods for estimating passive immunity status in neonatal beef calves. Veter- Clin. Pathol. 2022, 52, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsjäger, L.; Elsohaby, I.; Pearson, J.M.; Levy, M.; Pajor, E.A.; Windeyer, M.C. Evaluation of 3 refractometers to determine transfer of passive immunity in neonatal beef calves. J. Veter- Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, L.; Boccardo, A.; Forte, C.; Pravettoni, D.; D’avino, N.; Passamonti, F.; Rueca, F. Evaluation of digital and optical refractometers for assessing failure of transfer of passive immunity in Chianina beef–suckler calves reared in Umbria. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeputte, S.; Detilleux, J.; Rollin, F. Comparison of Four Refractometers for the Investigation of the Passive Transfer in Beef Calves. J. Veter- Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.; Leão, J.; Campos, J.; Coelho5, S.; Campos, M.; Mello Lima, J.; Faria, B. Evaluation of the Correlation between Total Plasma Protein of Serum of F1 Crossbred Holstein x Zebu Calves Evaluated with Optical and Digital Refractometer; 52a Reunião Anual da Sociedade Brasileira de Zootecnia, 2015.

- Drikic, M.; Windeyer, C.; Olsen, S.; Fu, Y.; Doepel, L.; De Buck, J. Determining the IgG concentrations in bovine colostrum and calf sera with a novel enzymatic assay. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenvey, C.J.; Reichel, M.P.; Lanyon, S.R.; Cockcroft, P.D. Optimizing the Measurement of Colostrum Antibody Concentrations for Identifying BVDV Persistently Infected Calves. Veter- Sci. 2015, 2, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhez, P.; Meurette, E.; Knapp, E.; Theron, L.; Daube, G.; Rao, A.-S. Assessment of a Rapid Semi-Quantitative Immunochromatographic Test for the Evaluation of Transfer of Passive Immunity in Calves. Animals 2021, 11, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.; Duffy, C.; Gordon, A.; Morrison, S.; Argűello, A.; Welsh, M.; Earley, B. Comparison of single radial immunodiffusion and ELISA for the quantification of immunoglobulin G in bovine colostrum, milk and calf sera. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2017, 46, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuder, A.J.; Breuer, R.M.; Wiley, C.; Dohlman, T.; Smith, J.S.; McKeen, L. Comparison of turbidometric immunoassay, refractometry, and gamma-glutamyl transferase to radial immunodiffusion for assessment of transfer of passive immunity in high-risk beef calves. J. Veter- Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.C.; Wills, R.W.; Smith, D.R. Sources of variance in the results of a commercial bovine immunoglobulin G radial immunodiffusion assay. J. Veter- Diagn. Investig. 2022, 35, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, L.; Boccardo, A.; Forte, C.; Pravettoni, D.; D’avino, N.; Passamonti, F.; Rueca, F. Evaluation of digital and optical refractometers for assessing failure of transfer of passive immunity in Chianina beef–suckler calves reared in Umbria. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, M.; Earley, B. Review: passive immunity in beef-suckler calves. Animal 2019, 13, 810–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, T.E.; Gay, C.C.; Pritchett, L. Comparison of three methods of feeding colostrum to dairy calves. J. Am. Veter- Med Assoc. 1991, 198, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, M.; McFadden, T.; Cockrell, D.; Besser, T. Regulation of Colostrum Formation in Beef and Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1994, 77, 3002–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.F.; Leslie, K.E. Newborn calf vitality: Risk factors, characteristics, assessment, resulting outcomes and strategies for improvement. Veter- J. 2013, 198, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odde, K.G. Survival of the Neonatal Calf. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 1988, 4, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, E.H.; Roberts, A. Genomic Analysis of Heterosis in an Angus × Hereford Cattle Population. Animals 2023, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topics, risk factors, or interventions | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Prevalence estimates of FPT in beef calves | 5 |

| Association between FPT and calf health outcomes | 8 |

| Factors related to colostrum management | |

| Colostrum quantity or volume fed | 1 |

| Colostrum quality (IgG concentration or source) | 3 |

| Timing of colostrum feeding | 2 |

| Colostrum microbial content | 1 |

| Colostrum feeding method | 8 |

| Factors related to calves | |

| Calf sex or twin status | 6 |

| Calf vigor at birth | 3 |

| Reproductive technologies used during breeding | 1 |

| Calf birth weight | 3 |

| Month of birth | 1 |

| Calf cortisol and epinephrine levels | 1 |

| Factors related to dams | |

| Dam body condition score (BCS) or udder conformation | 5 |

| Dam breed | 8 |

| Dam prepartum vaccination | 7 |

| Dam parity | 10 |

| Dam prepartum nutrition | 13 |

| Calving area (type and location) | 1 |

| Calving difficulty | 8 |

| Genetics and heritability | 4 |

| Methods of FPT detection in beef calves | 11 |

| Country where study was conducted | n | Study design | n | Breed | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 18 | Randomized controlled trial | 28 | Crossbred | 32 |

| Canada | 13 | Cohort study | 13 | Angus | 10 |

| Ireland | 9 | Diagnostic accuracy study | 12 | Charolais | 9 |

| Brazil | 5 | Cross-sectional study | 11 | Belgian Blue | 6 |

| Belgium | 4 | Case-control study | 1 | Limousin | 6 |

| France | 4 | Simmental | 4 | ||

| Italy | 4 | Hereford | 3 | ||

| Great Britain | 2 | Brahman | 2 | ||

| Australia | 1 | Chianina | 2 | ||

| Korea | 1 | Nelore | 2 | ||

| New Zealand | 1 | Aberdeen | 1 | ||

| Poland | 1 | Aubrac | 1 | ||

| Spain | 1 | Blonde d’Aquitaine | 1 | ||

| Turkey | 1 | Droughtmaster | 1 | ||

| Hanwoo | 1 | ||||

| Padra de Montana | 1 | ||||

| Pirenaica | 1 | ||||

| Salers | 1 |

| Reference | Method | Cutoff | Outcome Effect measure (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filteau et al., 2003 [14] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG1 | < 10.0 g/L | No association between FPT and health status (P = 0.17) in calves 24 h to 7 d old |

| Waldner and Rosengren, 2009 [15] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG | < 8 g/L < 16 g/L |

No association between FPT and calf death or treatment (P > 0.25) |

| < 24 g/L | Calf death before 3 months of age OR 1.6 (1.1- 2.3) |

||

| Calf treatment for any reason OR 1.5 (1.0 – 2.3) | |||

| Perrot et al., 2023 [18] | Serum % Brix | < 8.1 | No association between prevalence of omphalitis and FPT (P = 0.86) |

| Serum total protein | <5.1 g/dL | No association between prevalence of omphalitis and FPT (P = 0.63) | |

| Bragg et al., 2023 [19] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG | Every g/L increase | Death and/or treatment for disease within 9 months OR 0.97 (0.95 – 0.99) |

| Dewell et al., 2006 [7] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG1 | < 2,400 mg/dL | Disease before weaningLikelihood ratio 1.6 (1.19 – 2.28) |

| Death before weaning: Likelihood ratio 2.7 (1.34 – 5.36) | |||

| ≥ 2,700 mg/dL | 3.4 kg higher body weight at 205 days | ||

| Gamsjäger et al., 2023 [20] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG1 | < 10.0 g/L | Treatment for disease OR 7.9 (2.7–23.7) Mortality OR 18.5 (3.7–93.4) |

| < 24.0 g/L | Mortality OR 10.1 (2.6–40.2) |

||

| Martin et al., 2021 [21] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG levels | < 10g/L | Mortality Chi squared test compared to calves with IgG levels > 20 g/L, P < 0.001 |

| Todd et al., 2018 [22] | Serum total protein, digital refractometer | < 5.8 g/dL | Morbidity any cause (0 – 6 months) OR 1.6 (1.1 – 2.3) |

| < 5.8 g/dL | BRD (0 – 6 months)OR 2.3 (1.2 – 4.3) | ||

| < 6.3 g/dL | Other causes of disease (0 – 3 months)OR 2.5 (1.2 – 5.3) | ||

| < 5.3 g/dL | Mortality (0 – 6 months)OR 3.9 (2.0 – 7.7) | ||

| Serum IgG ELISA | < 8 mg/ml | Morbidity any cause (0 – 3 months) OR 2.0 (1.3 – 2.9) |

|

| < 8 mg/ml | BRD (0 – 1 months)OR 4.5 (1.4 – 14.5) | ||

| < 8 mg/ml | Other causes of disease (0 – 1 months)OR 1.8 (1.0 – 3.1) | ||

| < 9 mg/ml | Mortality (0 – 6 months)OR 2.8 (1.4 – 5.8) | ||

| Serum total protein, clinical analyzer | < 61 g/L | Morbidity any cause (0 – 3 months) OR 1.5 (1.1 – 2.2) |

|

| < 56 g/L | BRD (0 – 1 months)OR 6.2 (1.7 – 22.6) | ||

| < 61 g/L | Other causes of disease (0 – 6 months)OR 2.1 (1.2 – 3.7) | ||

| 60 g/L | Mortality (0 – 6 months)OR 4.3 (1.8 – 10.1) | ||

| Serum IgG globulin, clinical analyzer | 26 g/L | Morbidity any cause (0 – 3 months) OR 1.6 (1.1 – 2.4) |

|

| 32 g/L | BRD (0 – 1 months)OR 6.3 (1.3 – 29.8) | ||

| 40 g/L | Other causes of disease (0 – 1 months)OR 3.1 (1.2 – 8.0) | ||

| 32 g/L | Mortality (0 – 6 months)OR 3.4 (1.5 – 7.5) | ||

| Serum IgG Zinc sulphate turbidity, units | 12 g/L | Morbidity any cause (0 – 3 months) OR 1.8 (1.3 – 2.6) |

|

| 14 g/L | BRD (0 – 1 months)OR 11.2 (2.1 – 60.4) | ||

| 18 g/L | Other causes of disease (0 – 1 months)OR 2.2 (1.1 – 4.3) | ||

| 14 g/L | Mortality (0 – 6 months)OR 3.4 (1.6 – 7.0) | ||

| Serum total solids percentage, Brix | 8.4% | Morbidity any cause (0 – 6 months) OR 1.5 (1.1 – 2.2) |

|

| 8.4% | BRD (0 – 1 months)OR 7.2 (1.8 – 30.0) | ||

| 8.4% | Other causes of disease (0 – 6 months)OR 1.7 (1.1 –2.9) | ||

| 8.4% | Mortality (0 – 6 months)OR 2.8 (1.4 – 5.6) |

| Reference | Reference Method and Cutoff | Comparative Method and Cutoff | Measures of Test Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dunn et al. 2018 [73] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG concentration | Commercial serum ELISA | R2 = 0.97, P < 0.001 Fixed bias (sRID – ELISA) = 12.36 ± 6.60 mg/mL |

| Zinc sulphate turbidity | R2 = 078, P<0.001 | ||

| Akköse et al. 2021[65] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG concentration | Digital Brix refractometer |

|

| < 10 mg/mL | < 8.5% | Se 100% (95% CI 87.9 – 100), Sp 94.2% (95% CI 89.6 – 97.2) | |

| < 16 mg/mL | < 8.5% | Se 92.1% (95% CI 78.6 – 98.2) Sp 97.6% (95% CI 93.9 - 99.3) |

|

| < 24 mg/mL | < 10.1% | Se 88.8% (95% CI 79.7 – 94.7) Sp 67.2% (95% CI 58.1 – 75.4) |

|

| Digital serum total protein refractometer | |||

| < 10 mg/mL | < 5.2 g/dL | Se 100% (95% CI 87.9 – 100), Sp 93.6% (95% CI 88.9 – 96.8) | |

| < 16 mg/mL | < 5.2 g/dL | Se 92.1% (95% CI 78.6 – 98.2) Sp 97.0% (95% CI 93.0 - 99.0) |

|

| < 24 mg/mL | < 6.4 g/dL | Se 87.5% (95% CI 78.2 – 93.8) Sp 69.7% (95% CI 60.7 – 77.7) |

|

| Delhez et al., 2021[72] | Bovine IgG ELISA | Immunochromatographic assay for serum IgG with EDTA blood | |

| < 10 mg/mL | < 10 mg/mL | Se 83% Pr 94% | |

| 10.0 – 14.9 mg/mL | 10.0 – 14.9 mg/mL | Se 78% Pr 58% | |

| 15.0 – 19.9 mg/mL | 15.0– 19.9 mg/mL | Se 50% Pr 86% | |

| > 20.0 mg/mL | > 20.0 mg/mL | Se 100% Pr 70% | |

| Immunochromatographic assay for serum IgG with heparin blood | |||

| < 10 mg/mL | < 10 mg/mL | Se 96% Pr 81% | |

| 10.0 – 14.9 mg/mL | 10.0 – 14.9 mg/mL | Se 72% Pr 90% | |

| 15.0 – 19.9 mg/mL | 15.0– 19.9 mg/mL | Se 50% Pr 43% | |

| > 20.0 mg/mL | > 20.0 mg/mL | Se 74% Pr 70% | |

| Drikic et al. 2018 [70] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG concentration | Split trehalase IgG assay | |

| 24 mg/mL | OD 450 nm 0.3 | Se 69.2% Sp 97.2% | |

| Gamsjäger et al. 2021 [66] | Radial Immunodiffusion serum IgG | Digital Brix refractometer | |

| < 10 g/L | ≤ 7.9% | Se 81.2% (95% CI 54.4 – 96.0) Sp 94.8% (95% CI 92.0 – 96.8) |

|

| < 16 g/L | ≤ 8.3% | Se 88.2% (95% CI 72.5 – 96.7) Sp 90.9% (95% CI 87.5 – 93.7) |

|

| < 24 g/L | ≤ 8.7% | Se 80.0% (95% CI 68.7 – 88.6) Sp 93.0% (95% CI 89.6 – 95.5) |

|

| Digital and optical serum total protein refractometers | |||

| < 10 g/L | ≤ 5.1 g/dL | Digital Se 100% (95% CI 79.4 - 100) Sp 91.4% (95% CI 88.1 – 94.0) Optical Se 100% (95% CI 79.4 - 100) Sp 93.7% (95% CI 90.8 – 95.9) |

|

| < 16 g/L | ≤ 5.1 g/dL | Digital: Se 94.1% (95% CI 80.3 – 99.3) Sp: 95.3% (95% CI 92.6 – 97.3) Optical: Se 85.3 (95% CI 68.9-95.0) Sp 97.0 (95% CI 94.7-98.5) |

|

| < 24 g/L | ≤ 5.7 g/dL | Digital: Se 95.7 (95% CI 88.0-99.1) Sp: 93.3 (95% CI 90.0-95.7) Optical: Se 91.4 (95% CI 82.3-96.8) Sp 91.2 (95% CI 87.5-94.0) |

|

| Kreuder et al., 2022 [74] | Radial Immunodiffusion serum IgG | Turbidimetric immunoassay | |

| < 18.0 g/L | 9.89 g/L | Se: 0.910 (95% CI 0.861-0.951) Sp: 0.888 (95% CI: 0.772 – 1) |

|

| < 25.0 g/L | 13.76 g/L | Se: 0.813 (95% CI 0.729-0.885) SP: 0.818 (95% CI 0.712-0.909) |

|

| Digital serum total protein refractometer | |||

| < 18.0 g/L | 5.5 g/dL | Se: 0.818 (95% CI 0.761-0.869) Sp: 0.75 (95% CI 0.55-0.9) |

|

| < 25.0 g/L | 6.0 g/dL | Se: 0.756 (95% CI 0.677-0.827) Sp: 0.754 (95% CI 0.652-0.855) |

|

| Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase | |||

| < 18.0 g/L | 2303 IU/L | Se: 0.737 (95% CI 0.669-0.8) Sp: 0.7 (95% CI 0.5-0.9) |

|

| < 25.0 g/L | 1831 IU/L | Se: 0.905 (95% CI 0.849-0.952) Sp: 0.406 (95% CI 0.290-0.522) |

|

| Pisello et al., 2021 [76] | Radial Immunodiffusion serum IgG | Digital serum total protein refractometer | |

| < 16 g/L | 51 g/L | Se 63% Sp 96% | |

| Optical serum total protein refractometer | |||

| < 16 g/L | 52 g/L | Se 69% Sp 90% | |

| Digital Brix refractometer | |||

| < 16 g/L | 8.3% | Se 77% Sp 92% | |

| Optical Brix refractometer | |||

| < 16 g/L | 8.3% | Se 66% Sp 92% | |

| De Souza et al., 2015 [69] | Serum total protein optical refractometer | Serum total protein digital refractometer | No specific values mentioned, Pearson correlation between method results = 0.9588 |

| Sustronck et al. 2022 [17] | Radial immunodiffusion serum IgG | Digital Brix refractometer | |

| 10 g/L | 8.4% | Se 80.9 (95% CI 67.6–91.3) Sp 89.5 (95% CI 81.9–96.5) |

|

| 15 g/L | 8.9% | Se 77.9 (95% CI 69.0–86.0) Sp 90.2 (95% CI 78.7–97.7) |

|

| 20 g/L | 9.4% | Se 89.6 (95% CI 84.3–94.1) Sp 88.3 (95% CI 68.5–98.4) |

|

| Serum protein capillary electrophoresis | |||

| 10 g/L | 10 g/L | Se 81.8% (95% CI 68.0–92.5) Sp 91.0% (95% CI 83.5–97.7) |

|

| 15 g/L | 15 g/L | Se 92.4% (95% CI 85.4–97.6) Sp 80.0% (95% CI 65.6–91.5) |

|

| 20 g/L | 20 g/L | Se 98.3% (95% CI 95.1–99.9) Sp 87.6% (95% CI 63.0–98.7) |

|

| Vandeputte et al., 2011 [68] | Serum IgG with biuret method | Serum total protein handheld refractometer with Automatic Temperature Compensation (ATC), Atago conversion | |

| 1600 mg/dL | 58 g/L | Se 100% (95% CI 82 – 100) Sp 90% (95% CI 82.1 – 94.6) |

|

| Serum total protein handheld refractometer with ATC, Wolf conversion | |||

| 1600 mg/dL | 54 g/L | Se 100% (95% CI 82 – 100) Sp 93.3% (95% CI 86.2 – 96.9) |

|

| Serum total protein standard laboratory refractometer without ATC, Atago conversion | |||

| 1600 mg/dL | 56 g/L | Se 100% (95% CI 82 - 100) Sp 91.1% (95% CI 83.4- 95.4) |

|

| Serum total protein digital ATC handheld | |||

| 1600 mg/dL | 56 g/L | Se 100 (95% CI 82 – 100) Sp 92.2 (95% CI 84.8 – 96.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).