Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.1.1. Diagnostic Performance of AI in Ultrasound-Based nodule Classification

3.1.2. Risk Prediction Models for Surgical and Postoperative Outcomes

3.1.3. Study Designs and Risk of Bias Assessment

3.1.4. Integration of Multi-Modal Data

3.1.5. Real- World Clinical Utility and Workflow Optimization

3.1.6. Reporting Transparency and Methodological Rigor

4. Discussion

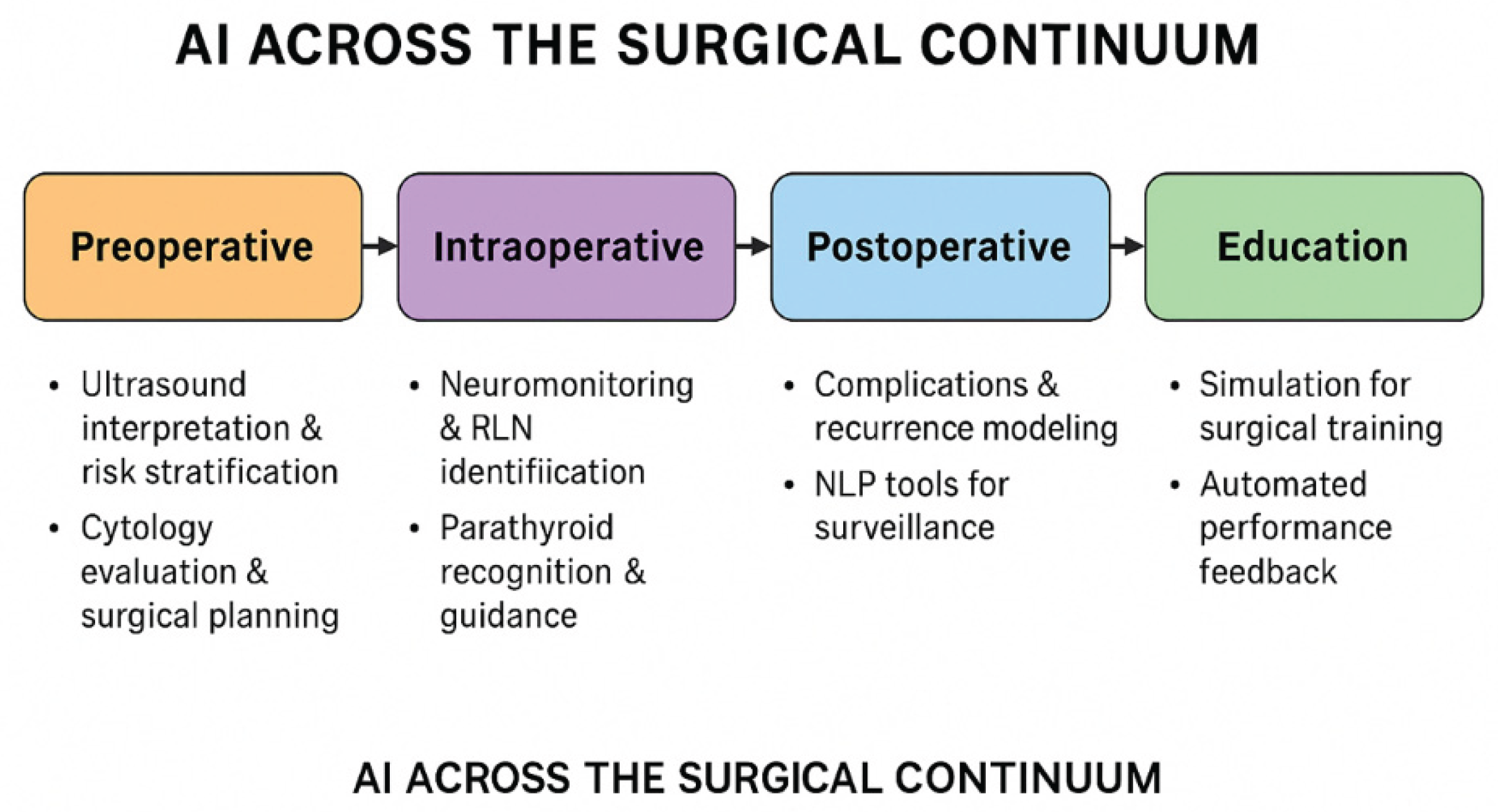

4.1. Diagnostic Advances in Preoperative Assessment

4.2. AI- Enhanced Intraoperative Tools

4.3. Postoperative Prognostics and Quality Improvement

4.4. Methodological Strengths and Shortcomings

4.5. Future Directions in Thyroid Surgical AI

4.6. Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CQI | Continuous Quality Improvement |

| CONSORT-AI | Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials-Artificial Intelligence |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| FNA | Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portable and Accountability Act |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| IONM | Intraoperative Neural Monitoring |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PROBAST | Prediction Model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies, Version 2 |

| SaMD | Software as a Medical Device |

| STARD | Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy |

| TI-RADS | Thyroid Imaging Reporting And Data System |

| TOETVA | Transoral Endoscopic Thyroidectomy Vestibular Approach |

| TRIPOD | Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual Prognosis or Diagnosis |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Aljameel, S.S. (2022) ‘A proactive explainable artificial neural network model for the early diagnosis of thyroid cancer’, Computation (Basel, Switzerland), 10(10), p. 183. [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.-L. et al. (2022) ‘Orbital and eyelid diseases: The next breakthrough in artificial intelligence?’, Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 10, p. 1069248. [CrossRef]

- Bellantuono,L. (2024) Artificial Intelligence-assisted thyroid cancer diagnosis from Raman spectra of histological samples (no date a). [CrossRef]

- Bellantuono, L. et al. (2023) ‘An eXplainable Artificial Intelligence analysis of Raman spectra for thyroid cancer diagnosis’, Scientific reports, 13(1), p. 16590. [CrossRef]

- Cece, A. et al. (2025) ‘Role of artificial intelligence in thyroid cancer diagnosis’, Journal of clinical medicine, 14(7). [CrossRef]

- Chantasartrassamee, P. et al. (2024) ‘Artificial intelligence-enhanced infrared thermography as a diagnostic tool for thyroid malignancy detection’, Annals of medicine, 56(1), p. 2425826. [CrossRef]

- Cong, P., Wang, X.-M. and Zhang, Y.-F. (2024) ‘Comparison of artificial intelligence, elastic imaging, and the thyroid imaging reporting and data system in the differential diagnosis of suspicious nodules’, Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 14(1), pp. 711–721. [CrossRef]

- David, E. et al. (2024) ‘Thyroid nodule characterization: Overview and state of the art of diagnosis with recent developments, from imaging to molecular diagnosis and artificial intelligence’, Biomedicines, 12(8), p. 1676. [CrossRef]

- Dip, F. et al. (2025) ‘Thyroid surgery under nerve auto-fluorescence & artificial intelligence tissue identification software guidance’, Langenbeck s Archives of Surgery, 410(1), p. 23. [CrossRef]

- Esce, A.R. et al. (2021) ‘Predicting nodal metastases in papillary thyroid carcinoma using artificial intelligence’, American journal of surgery, 222(5), pp. 952–958. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., Ran, X. and Ding, W. (2023) ‘The progress of radiomics in thyroid nodules’, Frontiers in oncology, 13, p. 1109319. [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.F. et al. (2023) ‘An Artificial Intelligence system for optimizing radioactive iodine therapy dosimetry’, Journal of clinical medicine, 13(1), p. 117. [CrossRef]

- Gorris, M.A. et al. (2025) ‘Assessing ChatGPT’s capability in addressing thyroid cancer patient queries: A comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation’, Journal of the Endocrine Society, 9(2), p. bvaf003. [CrossRef]

- Guo, F. et al. (2023) ‘Assessment of the statistical optimization strategies and clinical evaluation of an artificial intelligence-based automated diagnostic system for thyroid nodule screening’, Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 13(2), pp. 695–706. [CrossRef]

- Ha, E.J. and Baek, J.H. (2021) ‘Applications of machine learning and deep learning to thyroid imaging: where do we stand?’, Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea), 40(1), pp. 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, A. et al. (2025) ‘Can artificial intelligence software be utilised for thyroid multi-disciplinary team outcomes?’, Clinical otolaryngology: official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery, 50(4), pp. 769–774. [CrossRef]

- Jassal, K. et al. (2023) ‘Artificial intelligence for pre-operative diagnosis of malignant thyroid nodules based on sonographic features and cytology category’, World journal of surgery, 47(2), pp. 330–339. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E. et al. (2024) ‘Improving the diagnostic performance of inexperienced readers for thyroid nodules through digital self-learning and artificial intelligence assistance’, Frontiers in endocrinology, 15, p. 1372397. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-R. et al. (2020) ‘Artificial intelligence for personalized medicine in thyroid cancer: Current status and future perspectives’, Frontiers in oncology, 10, p. 604051. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, M. et al. (2023) ‘The use of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis and classification of thyroid nodules: An update’, Cancers, 15(3). [CrossRef]

- Luvhengo, T.E. et al. (2024) ‘Holomics and artificial intelligence-driven precision oncology for medullary thyroid carcinoma: Addressing challenges of a rare and aggressive disease’, Cancers, 16(20). [CrossRef]

- Mcintyre, C. et al. (2019) ‘Artificial Intelligence Thyroid MDT’, Artificial Intelligence Thyroid MDT. *BRITISH JOURNAL SURGERY* [Preprint].

- Namsena, P. et al. (2024) ‘Diagnostic performance of artificial intelligence in interpreting thyroid nodules on ultrasound images: a multicenter retrospective study’, Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 14(5), pp. 3676–3694. [CrossRef]

- Nishiya, Y. et al. (2024) ‘Anatomical recognition artificial intelligence for identifying the recurrent laryngeal nerve during endoscopic thyroid surgery: A single-center feasibility study’, Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology, 9(6), p. e70049. [CrossRef]

- Palomba, G. et al. (2024) ‘Artificial intelligence in screening and diagnosis of surgical diseases: A narrative review’, AIMS public health, 11(2), pp. 557–576. [CrossRef]

- Paydar, S., Pourahmad, S., et al. (2016) ‘The evolution of a malignancy risk prediction model for thyroid nodules using the artificial neural network’, Middle East Journal of Cancer, 7, pp. 47–52. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288616849.

- Piga, I. et al. (2023) ‘Paving the path toward multi-omics approaches in the diagnostic challenges faced in thyroid pathology’, Expert review of proteomics, 20(12), pp. 419–437. [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Ş. et al. (2024) ‘Evaluating the success of ChatGPT in addressing patient questions concerning thyroid surgery’, The journal of craniofacial surgery, 35(6), pp. e572–e575. [CrossRef]

- Sant, V.R. et al. (2024) ‘From bench-to-bedside: How artificial intelligence is changing thyroid nodule diagnostics, a systematic review’, The journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 109(7), pp. 1684–1693. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X., Yuan, A. and Zhang, K. (2022) ‘Ultrasound image under artificial intelligence algorithm in thoracoscopic surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma’, Scientific programming, 2022, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Song, X. et al. (2021) ‘Artificial intelligence CT screening model for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy and tests under clinical conditions’, International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery, 16(2), pp. 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, S. et al. (2022) ‘Artificial intelligence for thyroid nodule characterization: Where are we standing?’, Cancers, 14(14), p. 3357. [CrossRef]

- Swan, K.Z. et al. (2022) ‘External validation of AIBx, an artificial intelligence model for risk stratification, in thyroid nodules’, European thyroid journal, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Taha, A. et al. (2024) ‘Analysis of artificial intelligence in thyroid diagnostics and surgery: A scoping review’, American journal of surgery, 229, pp. 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi, A. et al. (2020) ‘Ultrasonographic risk stratification of indeterminate thyroid nodules; a comparison of an artificial intelligence algorithm with radiologist performance’, in 2020 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS). 2020 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Teiu, R.E. et al. (2024) ‘The use of artificial intelligence in the therapeutic management of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: A randomized controlled trial protocol’, Romanian Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 16(4), pp. 466–470. [CrossRef]

- Teodoriu, L. et al. (2022) ‘Personalized diagnosis in differentiated thyroid cancers by molecular and functional imaging biomarkers: Present and future’, Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 12(4), p. 944. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. and Haertling, T. (2020) ‘AIBx, artificial intelligence model to risk stratify thyroid nodules’, Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association, 30(6), pp. 878–884. [CrossRef]

- Tuo, J., Si, X. and Song, H. (2023) ‘Artificial intelligence technology enhances the performance of shear wave elastography in thyroid nodule diagnosis’, American journal of translational research, 15(10), pp. 6226–6233. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37969190.

- Wang, B. et al. (2022) ‘Development of Artificial Intelligence for parathyroid recognition during endoscopic thyroid surgery’, The Laryngoscope, 132(12), pp. 2516–2523. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. et al. (2023) ‘Diagnostic value of a dynamic artificial intelligence ultrasonic intelligent auxiliary diagnosis system for benign and malignant thyroid nodules in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis’, Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 13(6), pp. 3618–3629. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. et al. (2024) ‘Intraoperative AI-assisted early prediction of parathyroid and ischemia alert in endoscopic thyroid surgery’, Head & neck, 46(8), pp. 1975–1987. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. et al. (2023) ‘Artificial intelligence-based prediction of cervical lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer with CT’, European radiology, 33(10), pp. 6828–6840. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. et al. (2019) ‘Automatic thyroid nodule recognition and diagnosis in ultrasound imaging with the YOLOv2 neural network’, World journal of surgical oncology, 17(1), p. 12. [CrossRef]

- Xia, E. et al. (2021) ‘Preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma by an artificial intelligence algorithm’, American journal of translational research, 13(7), pp. 7695–7704. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34377246.

- Yang, W.-T., Ma, B.-Y. and Chen, Y. (2024) ‘A narrative review of deep learning in thyroid imaging: current progress and future prospects’, Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 14(2), pp. 2069–2088. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. et al. (2023) ‘Targeting the inward rectifier potassium channel 5.1 in thyroid cancer: artificial intelligence-facilitated molecular docking for drug discovery’, BMC endocrine disorders, 23(1), p. 113. [CrossRef]

- You, S. et al. (2025) ‘The diagnostic value of artificial intelligence in C-TIRADS 4-5 nodules, real-time dynamic ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound to enhance the difference between papillary thyroid carcinoma and nodular goiter’, Journal of clinical ultrasound: JCU [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.J. et al. (2021) ‘Adequacy and effectiveness of Watson for Oncology in the treatment of thyroid carcinoma’, Frontiers in endocrinology, 12, p. 585364. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. et al. (2024) ‘US of thyroid nodules: can AI-assisted diagnostic system compete with fine needle aspiration?’, European radiology, 34(2), pp. 1324–1333. [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B.D. et al. (2016) ‘The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate’, Big data & society, 3(2), p. 205395171667967. [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. (2019) ‘High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence’, Nature medicine, 25(1), pp. 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Morley, J. et al. (2020) ‘The ethics of AI in health care: A mapping review’, Social science & medicine (1982), 260(113172), p. 113172. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.Y. et al. (2021) ‘Ethical machine learning in healthcare’, Annual review of biomedical data science, 4(1), pp. 123–144. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. et al. (2021) ‘Deep learning-based artificial intelligence model to assist thyroid nodule diagnosis and management: a multicentre diagnostic study’, The Lancet. Digital health, 3(4), pp. e250–e259. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. et al. (2020) ‘Validation of the 2018 FIGO staging system of cervical cancer for stage III patients with a cohort from China’, Cancer management and research, 12, pp. 1405–1410. [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S. and Mertens, S. (2019) ‘SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles’, Research integrity and peer review, 4(1), p. 5. [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F. et al. (2011) ‘QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies’, Annals of internal medicine, 155(8), pp. 529–536. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, R.F. et al. (2019) ‘PROBAST: A tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies’, Annals of internal medicine, 170(1), pp. 51–58. [CrossRef]

| No. | First Author (Year) | Title (Shortened) | QUADAS-2 | PROBAST |

| 1 | Aljameel (2022) | Explainable ANN for Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Bao (2022) | AI in Orbital & Eyelid Diseases | No | No |

| 3 | Bellantuono (2024) | AI-Assisted Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis (Raman Spectra) | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Bellantuono (2023) | Explainable AI Raman Spectra for Thyroid Cancer | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Cece (2025) | AI in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Chantasartrassamee (2024) | AI-Enhanced Infrared Thermography for Thyroid Malignancy | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Cong (2024) | AI vs Elastic Imaging for Nodule Diagnosis | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | David (2024) | AI in Thyroid Nodule Characterization | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Dip (2025) | AI Tissue ID in Thyroid Surgery | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Esce (2021) | AI for Nodal Metastases Prediction in Thyroid Carcinoma | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Gao (2023) | Radiomics in Thyroid Nodules (Review) | No | No |

| 12 | Georgiou (2024) | AI for Radioactive Iodine Therapy Dosimetry | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Gorris (2025) | ChatGPT for Thyroid Cancer Patient Queries | No | No |

| 14 | Guo (2023) | AI Diagnostic System for Thyroid Nodule Screening | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Ha (2021) | ML/DL in Thyroid Imaging (Review) | No | No |

| 16 | Habeeb (2025) | AI for Thyroid MDT Outcomes | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | Jassal (2023) | AI for Pre-op Diagnosis of Malignant Thyroid Nodules | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Lee (2024) | AI Self-Learning for Thyroid Nodule Diagnosis | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | Li (2021) | AI for Personalized Medicine in Thyroid Cancer (Review) | No | No |

| 20 | Ludwig (2023) | AI in Diagnosis & Classification of Thyroid Nodules | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | Luvhengo (2024) | AI in Precision Oncology for Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | McIntyre (2019) | AI Thyroid MDT | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | Namsena (2024) | AI for Thyroid Nodule US Interpretation | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | Nishiya (2024) | AI for RLN Recognition in Thyroid Surgery | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | Palomba (2024) | AI in Surgical Disease Screening (Narrative Review) | No | No |

| 26 | Paydar (2016) | ANN for Malignancy Risk Prediction in Thyroid Nodules | Yes | Yes |

| 27 | Piga (2023) | Multi-omics in Thyroid Pathology (Review) | No | No |

| 28 | Sahin (2024) | ChatGPT for Thyroid Surgery Patient Questions | No | No |

| 29 | Sant (2024) | AI in Thyroid Nodule Diagnostics (Systematic Review) | No | No |

| 30 | Shen (2022) | AI Algorithm in Thoracoscopic Surgery for Thyroid Carcinoma | Yes | Yes |

| 31 | Song (2021) | AI CT Screening for Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy | Yes | Yes |

| 32 | Sorrenti (2022) | AI for Thyroid Nodule Characterization | Yes | Yes |

| 33 | Swan (2022) | External Validation of AIBx AI Model | Yes | Yes |

| 34 | Taha (2024) | AI in Thyroid Diagnostics & Surgery (Scoping Review) | No | No |

| 35 | Tahmasebi (2020) | AI vs Radiologist for Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules | Yes | Yes |

| 36 | Teiu (2024) | AI in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma Management (RCT Protocol) | Yes | Yes |

| 37 | Teodoriu (2022) | Personalized Diagnosis in Thyroid Cancers (Review) | No | No |

| 38 | Thomas (2020) | AIBx AI Model for Risk Stratification | Yes | Yes |

| 39 | Tuo (2023) | AI for Shear Wave Elastography in Thyroid Nodule Diagnosis | Yes | Yes |

| 40 | Wang, Bing (2023) | AI US Diagnosis in Hashimoto Thyroiditis | Yes | Yes |

| 41 | Wang, Bo (2024) | Intraoperative AI in Endoscopic Thyroid Surgery | Yes | Yes |

| 42 | Wang, Bo (2022) | AI for Parathyroid Recognition During Thyroid Surgery | Yes | Yes |

| 43 | Wang, Cai (2023) | AI Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in PTC (CT) | Yes | Yes |

| 44 | Wang, Lei (2019) | YOLOv2 AI for Thyroid Nodule US Diagnosis | Yes | Yes |

| 45 | Xia (2021) | AI for Pre-op Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis | Yes | Yes |

| 46 | Yang, Wan-Ting (2024) | Deep Learning in Thyroid Imaging (Narrative Review) | No | No |

| 47 | Yang, Xue (2023) | AI Molecular Docking for Drug Discovery in Thyroid Cancer | No | No |

| 48 | You (2025) | AI in C-TIRADS 4-5 Nodules Diagnosis | Yes | Yes |

| 49 | Yun (2021) | Watson for Oncology in Thyroid Carcinoma | Yes | Yes |

| 50 | Zhou (2024) | AI-Assisted US vs FNA for Thyroid Nodules | Yes | Yes |

| No. | First Author (Year) | Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | Flow & Timing | Applicability Concerns (Patient / Index / Reference) | Score (LowRisk Domains) |

| 1 | Aljameel (2022) | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low / Low / High | 2 |

| 2 | Bao (2022) | High | High | High | High | High / High / High | 0 |

| 3 | Bellantuono (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 4 | Bellantuono (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 5 | Cece (2025) | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low / Low / Unclear | 3 |

| 6 | Chantasartrassamee (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 7 | Cong (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 8 | David (2024) | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Low / Unclear | 1 |

| 9 | Dip (2025) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 10 | Esce (2021) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 11 | Gao (2023) | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Low / Unclear | 1 |

| 12 | Georgiou (2024) | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low / Low / Unclear | 2 |

| 13 | Gorris (2025) | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low / Unclear / Unclear | 1 |

| 14 | Guo (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 15 | Ha (2021) | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low / Low / Unclear | 3 |

| 16 | Habeeb (2025) | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low / Low / Unclear | 3 |

| 17 | Jassal (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 18 | Lee (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 19 | Li (2021) | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Low / Unclear | 1 |

| 20 | Ludwig (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 21 | Luvhengo (2024) | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Low / Unclear | 1 |

| 22 | McIntyre (2019) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Unclear / Unclear | 0 |

| 23 | Namsena (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 24 | Nishiya (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 25 | Palomba (2024) | High | High | High | High | High / High / High | 0 |

| 26 | Paydar (2016) | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Low / Unclear | 1 |

| 27 | Piga (2023) | Unclear | High | High | High | Unclear / High / High | 0 |

| 28 | Sahin (2024) | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low / Low / Unclear | 2 |

| 29 | Sant (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 30 | Shen (2022) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 31 | Song (2021) | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Low / Unclear | 1 |

| 32 | Sorrenti (2022) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 33 | Swan (2022) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 34 | Taha (2024) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / Unclear / Unclear | 0 |

| 35 | Tahmasebi (2020) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 36 | Teiu (2024) | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low / Low / Unclear | 3 |

| 37 | Teodoriu (2022) | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / High / Unclear | 0 |

| 38 | Thomas (2020) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 39 | Tuo (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 40 | Wang, Bing (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 41 | Wang, Bo (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 42 | Wang, Bo (2022) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 43 | Wang, Cai (2023) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 44 | Wang, Lei (2019) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| 45 | Xia (2021) | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low / Low / Unclear | 2 |

| 46 | Yang, Wan-Ting (2024) | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / High / Unclear | 0 |

| 47 | Yang, Xue (2023) | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear / High / Unclear | 0 |

| 48 | You (2025) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low / Low / Low | 3 |

| 49 | Yun (2021) | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low / Low / Unclear | 2 |

| 50 | Zhou (2024) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low / Low / Low | 4 |

| Reference Number | Title | 1. Justification of Importance (0-2) | 2. Aims/Questions Stated (0-2) | 3. Literature Search Described (0-2) | 4. Referencing (0-2) | 5. Scientific Reasoning (0-2) | 6. Presentation of Data (0-2) | Total Score (0-12) |

| 25 | Artificial intelligence in screening and diagnosis of surgical diseases: A narrative review | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| 34 | Analysis of artificial intelligence in thyroid diagnostics and surgery: A scoping review | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| 46 | A narrative review of deep learning in thyroid imaging: current progress and future prospects | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).