1. Introduction

Transformer models have reshaped the landscape of natural language processing—the branch of AI that trains machines to interpret and generate human language. In older architectures such as (RNNs) (Elman 1990), inputs are processed sequentially, with each step depending on the previous one. The key innovation introduced by Transformer models is the attention mechanism, which allows the model to evaluate all elements of a sequence and their relative organisation simultaneously, enabling faster and more flexible learning (Vaswani et al. 2017).

By capturing long-range dependencies (i.e. relationships between words that may be far apart in a sentence or passage), Transformer models can interpret context and intended meaning more accurately and efficiently. These models form the foundation of widely used systems such as BERT (for understanding text) and GPT (for generating text) (Devlin et al. 2019; Radford et al. 2018; Radford et al. 2019). The same architecture has also been adapted for other types of data, including image recognition and analysis (Dosovitskiy et al. 2020).

In parallel, machine learning in neuroimaging has advanced considerably, but many models still treat brain features as spatially independent or interchangeable, overlooking the hierarchical and multiscale organization of the brain. Prior efforts to incorporate biology into brain modelling have used gene expression maps or connectivity matrices, but none to date have embedded such priors directly into the architecture of deep learning models. Transformer models, with their ability to capture long-range dependencies, could be well suited to interpreting multivariate and multiscale neuroimaging data (Hansen et al. 2022; Lawn et al. 2023), filling this gap by using biologically plausible filters as static attention mechanisms that shape learning in a structured and interpretable way.

In this study, we introduce Neuro-BOTs—a framework inspired by Transformer architectures that applies attention mechanisms to brain imaging data. Rather than learning attention weights entirely from the data, Neuro-BOTs incorporate biologically informed filters derived from prior knowledge, such as neurotransmitter maps (Beliveau et al. 2017), mitochondrial distribution (Mosharov et al. 2024), and structural connectivity (Betzel et al. 2019). These filters are used to construct static attention matrices, which shape the flow of information through the model by emphasizing biologically plausible relationships between brain regions. In this way, Neuro-BOTs embed neuroscience priors directly into the learning architecture, improving both interpretability and biological grounding.

To demonstrate the utility of Neuro-BOTs, we apply the model to a binary classification task using resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) data from patients with Parkinson’s disease and healthy controls. This type of data is particularly suited to this framework, as it captures intrinsic functional connectivity patterns that are shaped by both anatomical wiring and underlying neuromodulatory systems and it is commonly used for benchmarking predictive models. The presented framework is particularly generalisable beyond the case study and could be extended to other neuroscience applications where multiscale biological structure plays a critical role.

1.1. NLP Transformers

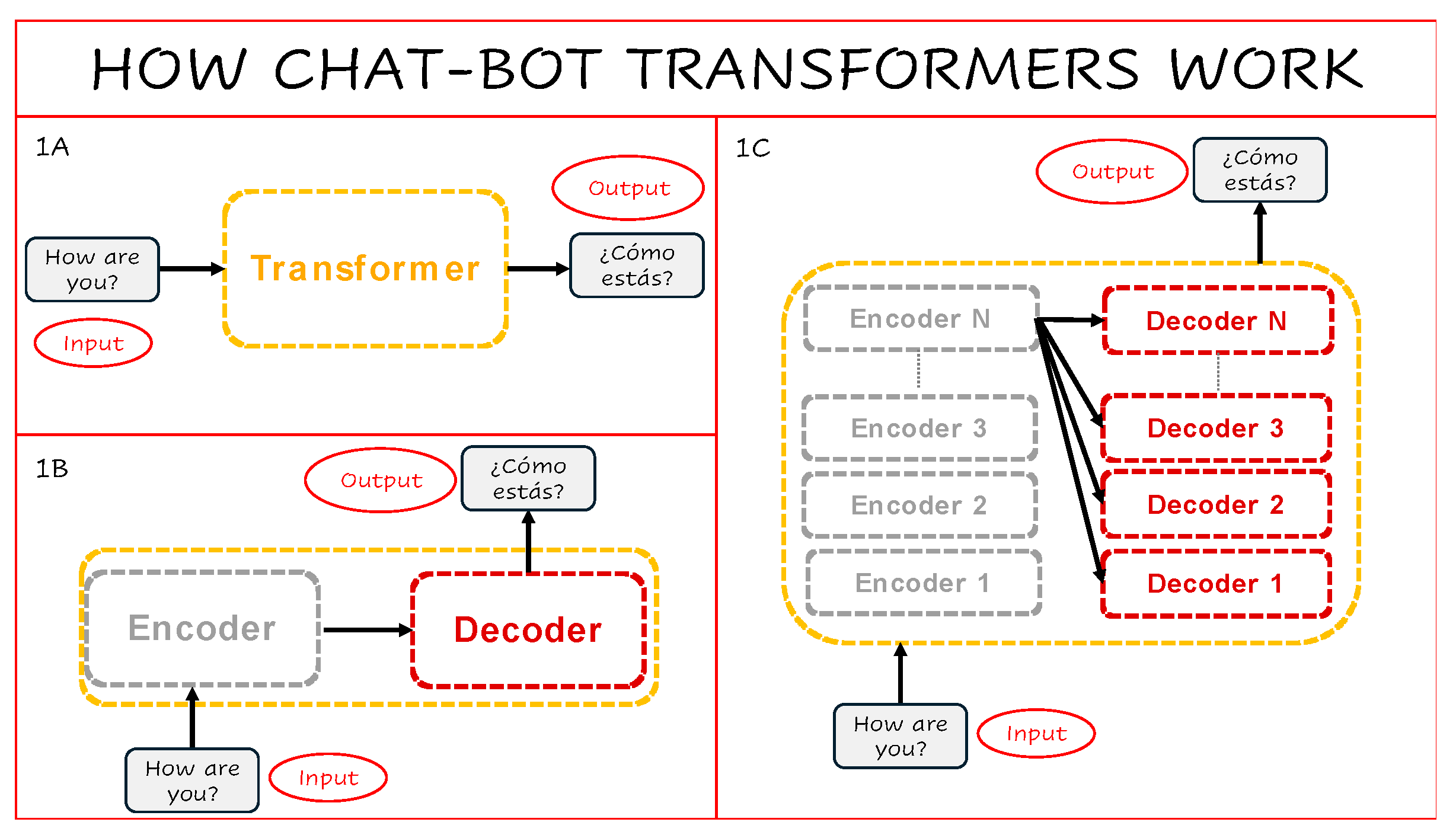

Transformer models used in natural language processing (NLP) are built around two main components: an encoder and a decoder. The encoder processes an input sentence—such as “How are you?”—and transforms it into a numerical representation. The decoder then takes this representation and generates a corresponding output, for example in another language: “¿Cómo estás?” (

Figure 1A–B). Modern Transformers typically stack multiple encoder and decoder blocks in parallel, allowing them to model complex dependencies across input and output sequences (

Figure 1C).

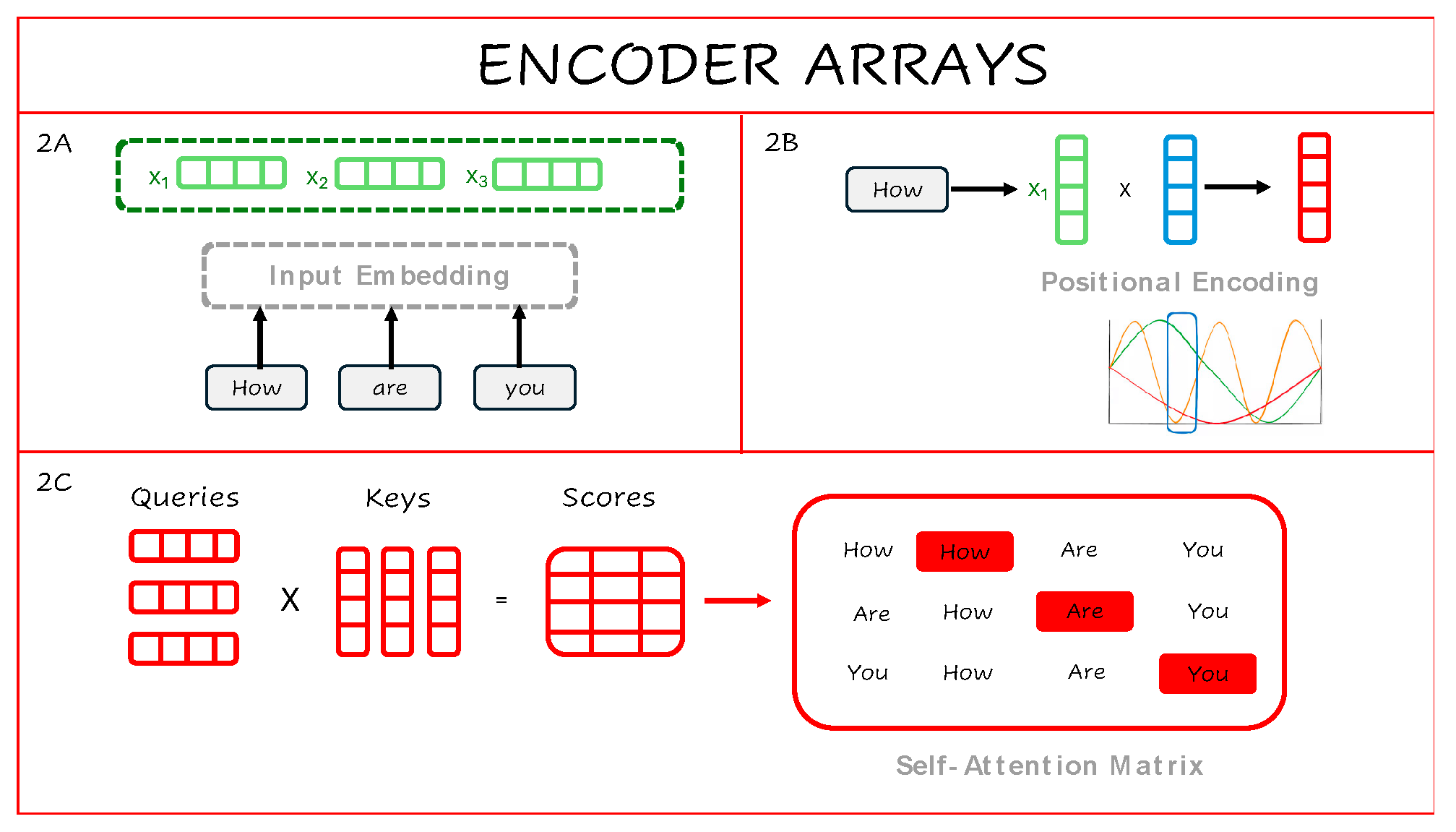

The core innovation of Transformer models lies in the attention mechanism, which enables the relevance of each word in a sentence to be evaluated with respect to every other word—without relying on sequential processing. To do this, each word is first converted into a numerical array through input embedding and combined with positional encodings, which preserve word order using periodic functions (

Figure 2A–B). This combined representation is then used to calculate self-attention scores by comparing each word to every other word via dot products of learned vectors—referred to as queries, keys, and values (

Figure 2C).

The result is a self-attention matrix that reflects contextual relationships across the entire sentence. A single attention head produces one such matrix, while multi-head attention allows the model to generate multiple contextual views in parallel, improving representational richness. Each attention head learns to focus on different types of relationships—such as short- or long-range associations—so combining them enables the model to capture diverse patterns in the input more effectively.

Although initially designed for language processing, Transformer models have recently been applied to neuroimaging. In one line of work, they were used to reduce high-dimensional brain images into compact latent representations (abstract numerical summaries), using architectures such as vector quantized variational autoencoders (VQ-VAE)

(Razavi, Van den Oord, and Vinyals 2019; van den Oord, Vinyals, and Kavukcuoglu 2017). VQ-VAE are neural networks that compress high-dimensional data into discrete codes, allowing complex inputs like brain images to be represented in a simplified format. They have also been adapted into normative models, which are trained on healthy brain data to learn a probability distribution over typical patterns. These models can then be used to detect both localized lesions and more subtle distributed abnormalities (Razavi, Van den Oord, and Vinyals 2019; Mendes et al. 2024).

In the following section, we introduce a new application of Transformer-based architectures—Neuro-BOTs—that directly integrate biological priors into the attention mechanism, enabling interpretable learning across spatially organized brain imaging features.

1.2. The Neuro-BOT Transformer Architecture

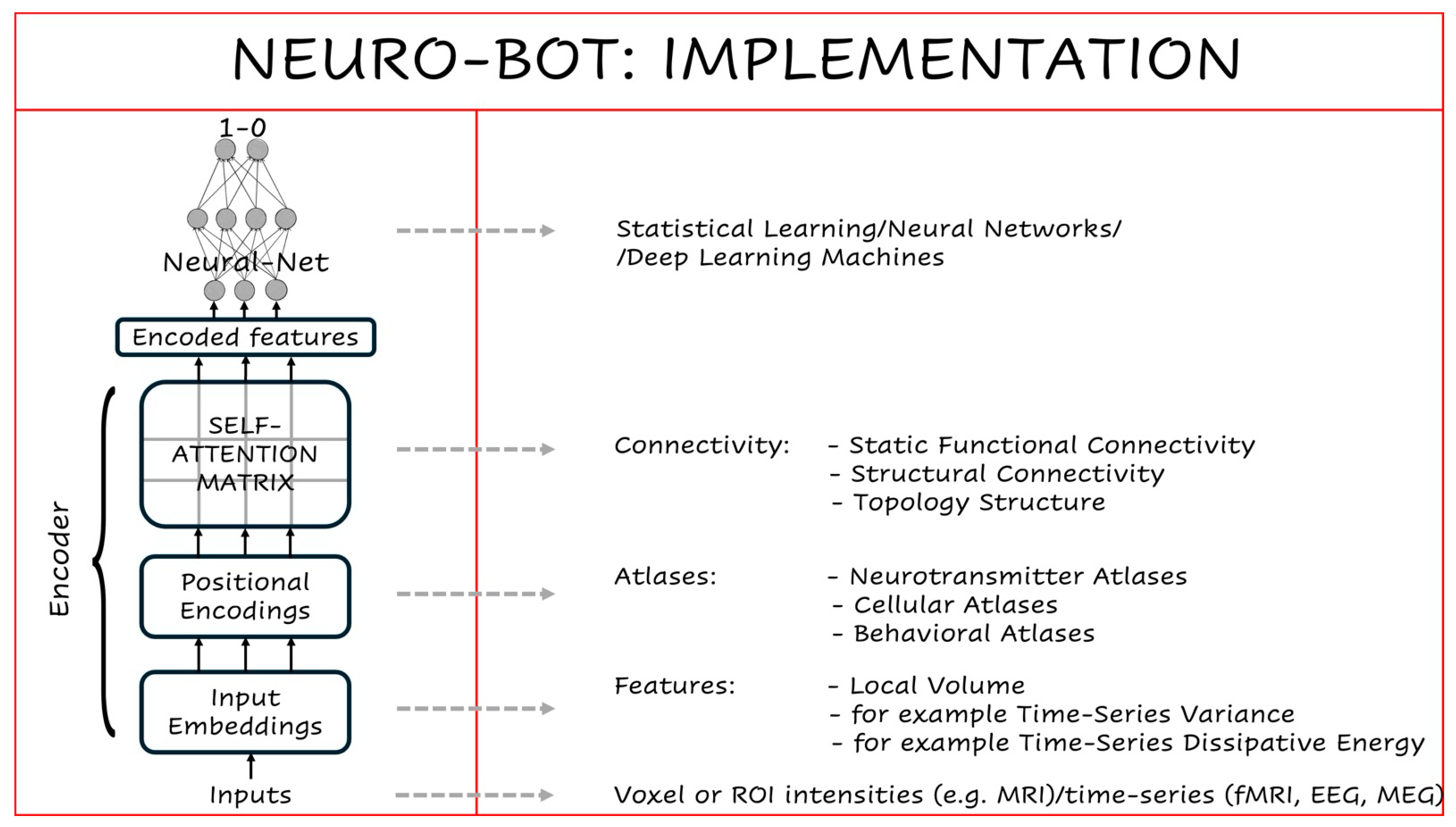

Neuro-BOTs adapt the Transformer encoder stack to explicitly embed biological knowledge in a single feature vector that is directly fedinto a statistical learning layer for neuroimaging-based prediction tasks (

Figure 3).

Rather than learning all attention patterns from data, Neuro-BOTs use structured, domain-informed filters that reflect known features of brain organization. These filters are integrated through each encoder stage, allowing multiscale neurobiological priors to shape the flow of information. The result is an architecture that supports both accurate classification and biologically interpretable inference.

1.3. Input Embeddings

In NLP, input embeddings convert words into numerical vectors that the model can process. In Neuro-BOTs, these inputs are not words, but imaging-derived features sampled from spatial units such as voxels or anatomically defined regions of interest (ROIs). The nature of these features depends on the imaging modality. For example, in structural MRI, input features may include voxel-wise intensities or morphometric metrics (Schaefer et al. 2018). In rs-fMRI, they may reflect time-series statistics such as variance or dissipative energy (Fagerholm et al. 2024). For EEG or MEG data, features might include power spectral density in specific frequency bands (e.g., alpha or gamma) or measures of signal complexity such as spectral entropy or multiscale entropy. These features form the base input array for the encoder.

1.4. Positional Encodings

While NLP models use positional encodings to track word order, Neuro-BOTs redefine them as biologically grounded spatial filters. Each encoding array represents prior knowledge from a brain atlas—for instance, maps of grey matter morphometry (Bethlehem et al. 2022), myelin content (Glasser and Van Essen 2011), gene expression (Hawrylycz et al. 2012), cytoarchitecture (Scholtens et al. 2018), neurotransmitter receptor density (Beliveau et al. 2017; Hansen et al. 2022), laminar differentiation (Wagstyl et al. 2020), evolutionary expansion (Zilles and Palomero-Gallagher 2017) patterns of brain activation during specific behavioural tasks as derived from meta-analysis (Yarkoni et al. 2011),. These arrays are applied to the input via elementwise (scalar) multiplication, modulating signal intensity in a coordinated and spatially heterogeneous manner. This enforces anatomical, molecular or functional structure early in the encoding process.

1.5. Self-Attention Matrices

While positional encodings impose localized modulation, self-attention matrices introduce global dependencies. These are derived from known covariance structures—such as functional connectivity networks, structural connectomes, or topological graphs. Each matrix captures relationships among brain regions based on shared activity or structure, obtained using techniques like singular value decomposition, independent component analysis (ICA) (Calhoun et al. 2001) and graph-based or topological network analysis (Petri et al. 2014; Sporns 2013). As with positional encodings, these matrices are applied to the input using scalar products. This step allows the model to incorporate large-scale inter-regional relationships that reflect known brain-wide patterns.

1.6. Mono-Head vs Multi-Head Attention

Neuro-BOTs can apply either a single attention filter (mono-head) or a combination of filters (multi-head). In the multi-head case, multiple positional or self-attention matrices are applied in parallel, and their outputs concatenated to form a composite feature vector. This allows the model to integrate multiple biological priors simultaneously—for example, laminar maps alongside dopamine receptor density maps—while preserving dimensional alignment with the original input space.

1.7. Statistical Learning

Once the data pass through the encoder stages, the resulting feature vector is passed to a statistical learning model. Neuro-BOTs are agnostic to the specific learning algorithm: one can use linear models (e.g., logistic regression), nonlinear classifiers (e.g., neural networks), or ensemble techniques (Dafflon et al. 2020). In high-dimensional, low-sample settings typical of neuroimaging, feature selection methods (Pudjihartono et al. 2022) can be applied prior to classification to reduce overfitting.

1.8. Task-Specific Application: Parkinson’s Disease

In this study, we apply Neuro-BOTs to a binary classification task using rs-fMRI data to distinguish patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) from healthy controls. The encoder is constructed using fixed attention matrices that reflect neurobiological features implicated in PD pathophysiology. In addition to classifying clinical state, the model provides biologically interpretable insights into which systems contribute most to prediction. This dual capability—of both inference and classification—is a key feature of the Neuro-BOT framework.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study included 41 patients with idiopathic PD, enrolled at the Parkinson’s Foundation Centre of Excellence at King’s College Hospital, London.

Seventeen age-matched healthy controls with no neurological or psychiatric history were also recruited. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Verona (Project No. 2899, Approval No. 48632, 14/09/2020), and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. MRI Acquisition

All MRI data were acquired using a 3 T GE Discovery MR750 scanner equipped with a 32-channel head coil. The imaging protocol included a T1-weighted (T1w) structural scan using a Fast Grey Matter Acquisition T1 Inversion Recovery (FGATIR) 3D sequence (TR = 6150 ms, TE = 2.1 ms, TI = 450 ms, voxel size = 1 x 1 x 1 mm³); approximately 7 minutes of rs-fMRI acquired using a multiband single-echo 3D Echo-Planar Imaging (EPI) sequence (TR = 890 ms, TE = 39 ms, flip angle = 50°, voxel size = 2.7 x 2.7 x 2.4 mm³, MultiBand acceleration factor = 6, 495 volumes).

2.3. Image Pre-Processing

Preproce-ssing of anatomical and functional data was performed using FMRIPREP version 23.2.2 (Esteban et al. 2019). The T1w image was corrected for intensity non-uniformity and skull-stripped. Brain surfaces were reconstructed using ‘recon-all’ from FreeSurfer (Fischl 2012), and the brain mask estimated previously was refined with a custom variation of the method to reconcile ANTs-derived and FreeSurfer-derived segmentations of the cortical grey matter (GM). Spatial normalization to the ICBM 152 Nonlinear Asymmetrical template version 2006 was performed through nonlinear registration, using brain-extracted versions of both the T1w volume and the template. Brain tissue segmentation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), white matter (WM), and GM was performed on the brain-extracted T1w using FSL’s FAST tool.

The first 8 volumes of the rs-fMRI acquisition were removed, to allow the magnetization to reach the steady state. Functional data was then slice-time corrected and motion corrected. This was followed by co-registration to the corresponding T1w using boundary-based registration with six degrees of freedom. Motion correction transformations, BOLD-to-T1w transformation, and T1w-to-template (MNI) warp were concatenated and applied in a single step. Physiological noise regressors were extracted using CompCor. Principal components were estimated for the two CompCor variants: temporal (tCompCor) and anatomical (aCompCor). A mask to exclude signal with cortical origin was obtained by eroding the brain mask, ensuring it only contained subcortical structures. Six tCompCor components were then calculated, including only the top 5% variable voxels within that subcortical mask. For aCompCor, six components were calculated within the intersection of the subcortical mask and the union of CSF and WM masks calculated in T1w space, after their projection to the native space of each functional run. Frame-wise displacement (FD) was calculated for each functional volume.

The FMRIPREP functional outputs were then subjected to additional processing using xcp_d version 0.7.4 (Mehta et al. 2024). After interpolating high-motion outlier volumes (FD > 0.5 mm) with cubic spline, confound regression was applied to the fMRI data. The regression matrix included six motion parameters and their derivatives, five aCompCor components relative to CSF and five to WM. Finally, high-pass temporal filtering with a cut-off frequency of 0.001 Hz was applied, followed by spatial smoothing with a FWHM of 6 mm.

Time series were extracted from 200 cortical parcels using the Schaefer functional atlas(Schaefer et al. 2018).

2.4. NEUROBOT Transformer Implementation

The attention layers incorporated into the Neuro-BOT framework were selected to reflect multiscale biological systems that are mechanistically relevant to PD. These included molecular, metabolic, and structural priors, each designed to act as inductive constraints that guide model learning in a biologically meaningful way. Their inclusion served a dual purpose: first, to enhance model interpretability by embedding well-characterized neurobiological systems into the architecture; second, to test which systems contribute most strongly to classification performance.

At the molecular level, we included whole-brain maps of neurotransmitter transporter density for dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline, and acetylcholine reported in (Lawn et al. 2024). These systems are all implicated to varying degrees in PD. Dopaminergic neurodegeneration is the most recognized feature of the disease, but growing evidence highlights early involvement of other monoaminergic systems. Noradrenaline and serotonin, originating from the locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei respectively, are particularly relevant in the prodromal phase and have been associated with non-motor symptoms such as REM sleep behaviour disorder, fatigue, and depression. The acetylcholine system, while more closely associated with cognitive decline in later disease stages, was included as a biologically plausible control to assess the specificity of monoaminergic contributions.

To capture cellular-level dysfunction, we incorporated mitochondrial maps describing Complex II and IV expression, mitochondrial tissue density, and respiratory capacity (Mosharov et al. 2024). Mitochondrial impairment is a central feature of PD pathophysiology, contributing to neuronal vulnerability through impaired ATP production, oxidative stress, and failure of energy-dependent cellular processes. Including these maps allowed the model to evaluate whether regional variation in metabolic integrity improves detection of disease-related patterns in functional activity.

Structural priors were derived from principal components of structural connectivity matrices (Jolliffe 2002) based on data from healthy individuals in the Human Connectome Project (Van Essen et al. 2013), following the methods of (Betzel et al. 2019). These were used to define self-attention matrices that capture large-scale brain topology. Structural architecture shapes the propagation of activity across networks, and prior studies suggest that disease-related functional alterations in PD are constrained by underlying anatomical pathways. By incorporating structural priors, the model can account for how topological embedding may facilitate or restrict the expression of pathological dynamics.

Regional estimates of dissipative energy were computed from the rs-fMRI time series using a validated algorithm that quantifies deviation from conservative dynamics in BOLD fluctuations (Fagerholm et al. 2024). These estimates reflect the extent to which neural activity in a given region dissipates energy over time. Each participant’s data was represented as a 200-dimensional feature vector, aligned to the Schaefer parcellation.

Each biological map or structural component was similarly resampled into Schaefer space and applied to the input embeddings via elementwise scalar multiplication (for vectors) or dot product operations (for matrices) - either amplifying or suppressing specific patterns. Each biologically informed encoder transformed the input features prior to classification and was tested independently. As mentioned before, when data dimensionality allows, multi-head approaches when different processed features are collected together before learning, can be used. However, for the data at hand, a sequential testing of each mono-layer was preferred.

To reduce dimensionality, an ANOVA-based feature selection method (Guyon 2003) retained the 10 most informative features per encoder. These reduced feature vectors were then passed to a statistical learning pipeline implemented in MATLAB using the Classification Learner of the Machine Learning and Deep Learning Toolbox. We evaluated multiple classification algorithms, including linear predictors, decision trees, discriminant analysis, naïve Bayes, logistic regression, support vector machines (SVM), k-nearest neighbours (k-NN), kernel approximations, ensemble methods, and neural networks. Model performance was assessed using 5-fold cross-validation that, by default, ensures that the class proportions in each fold remain approximately the same as the class proportions in the response variable. (Paluszek, Thomas, and Ham 2022). For each biologically informed encoder, we recorded the mean classification accuracy across the top three performing classifiers.

2.5. Statistics

To determine whether any individual attention or self-attention layer significantly improved classification performance, we tested accuracy values against a null hypothesis of no improvement. For this, we applied MATLAB’s inbuilt outlier detection function, using both parametric and non-parametric criteria:

2.5.1. Parametric Outlier Detection (Grubbs’ Test)

Grubbs’ test identifies a single outlier by computing a studentized deviation—the distance of the most extreme value from the sample mean, scaled by the standard deviation (Grubbs 1950). The test rejects the null hypothesis if this deviation corresponds to a .

2.5.2. Non-Parametric Outlier Detection (MAD)

In the non-parametric approach, outliers are defined as values more than three scaled median absolute deviations (MAD) from the median, also approximately corresponding to

. The scaled MAD is computed as:

where:

and the function

is the inverse of the complementary error function

:

This dual approach ensures robustness in detecting statistical outliers among model accuracies, both under normality assumptions (Grubbs) and without them (MAD).

3. Results

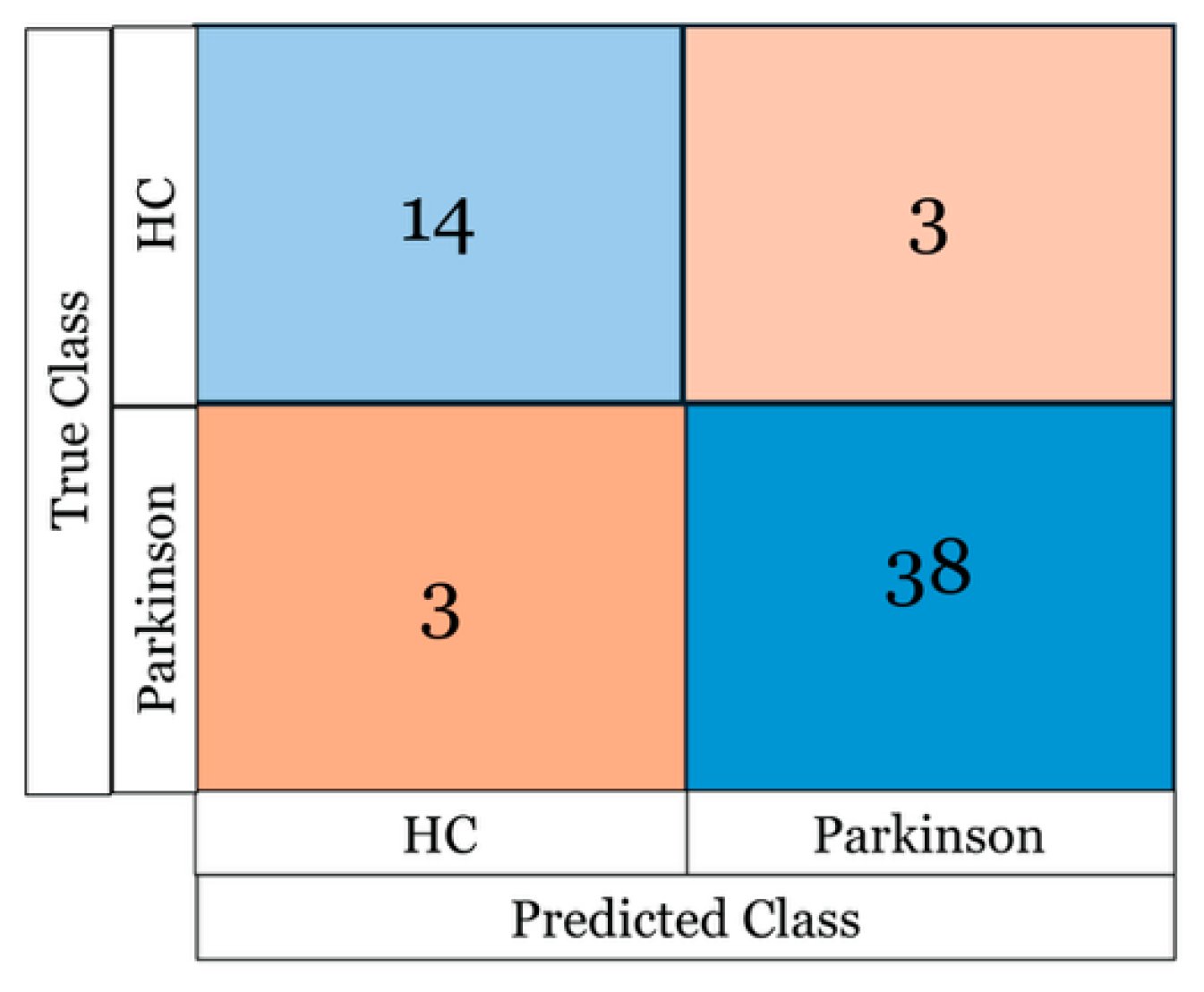

Table 1 summarizes the mean classification accuracy across the top three performing statistical algorithms for each configuration. These results reflect the effect of applying different positional and self-attention layers to the base input vector (regional dissipative energy estimates). Although the three best algorithms varied by condition, ensemble methods and neural networks were the most frequent top performers overall.

Among the five structural networks extracted via PCA from the Human Connectome Project data (representing of total variance), none of the self-attention layers led to notable accuracy improvements. Across all layers tested, accuracies clustered tightly around a mean of . The one clear exception was the noradrenaline-based positional encoder, which yielded a substantial performance increase—achieving an accuracy of , significantly higher than all other layers , as confirmed by both Grubbs’ test and scaled MAD outlier detection.

Figure 4 shows the confusion matrix for the best-performing model (a neural network) using the noradrenaline encoder. Despite the limited sample size and class imbalance, the classifier achieved strong discrimination between healthy controls and PD patients.

4. Discussion

In this study, we introduced Neuro-BOTs: a Transformer-based architecture for analysing brain imaging data using biologically informed attention mechanisms. By incorporating domain knowledge—such as molecular, metabolic, or connectivity-based maps—into positional and self-attention layers, Neuro-BOTs enable both improved predictive accuracy and biologically interpretable modelling. In our case study using regional dissipative energy estimates from resting-state fMRI, one particular attention layer—derived from noradrenaline transporter distribution—significantly improved classification of Parkinson’s disease versus control participants. The high classification performance achieved using a noradrenergic attention layer highlights the clinical relevance of brainstem monoaminergic systems in early Parkinson’s disease (Braak et al. 2003; Surmeier, Obeso, and Halliday 2017; Weinshenker 2018). While the lack of substantial gains with dopaminergic encoders might appear surprising given dopamine’s central role in PD, it is consistent with evidence that noradrenergic degeneration in the locus coeruleus often precedes dopaminergic loss in the substantia nigra. This aligns with histopathological staging showing early alpha-synuclein deposition in the locus coeruleus—the primary source of noradrenaline in the brain—as well as recent findings linking noradrenergic dysfunction to REM sleep behaviour disorder (Delaville, Deurwaerdère, and Benazzouz 2011; Doppler et al. 2021) and glymphatic clearance deficits which in turn compromises mitochondrial energy production (Hauglund et al. 2025; Kopeć et al. 2023). Our model’s sensitivity to noradrenergic disruption suggests that biologically constrained attention layers may capture early pathophysiological signatures that are otherwise obscured in purely data-driven models.

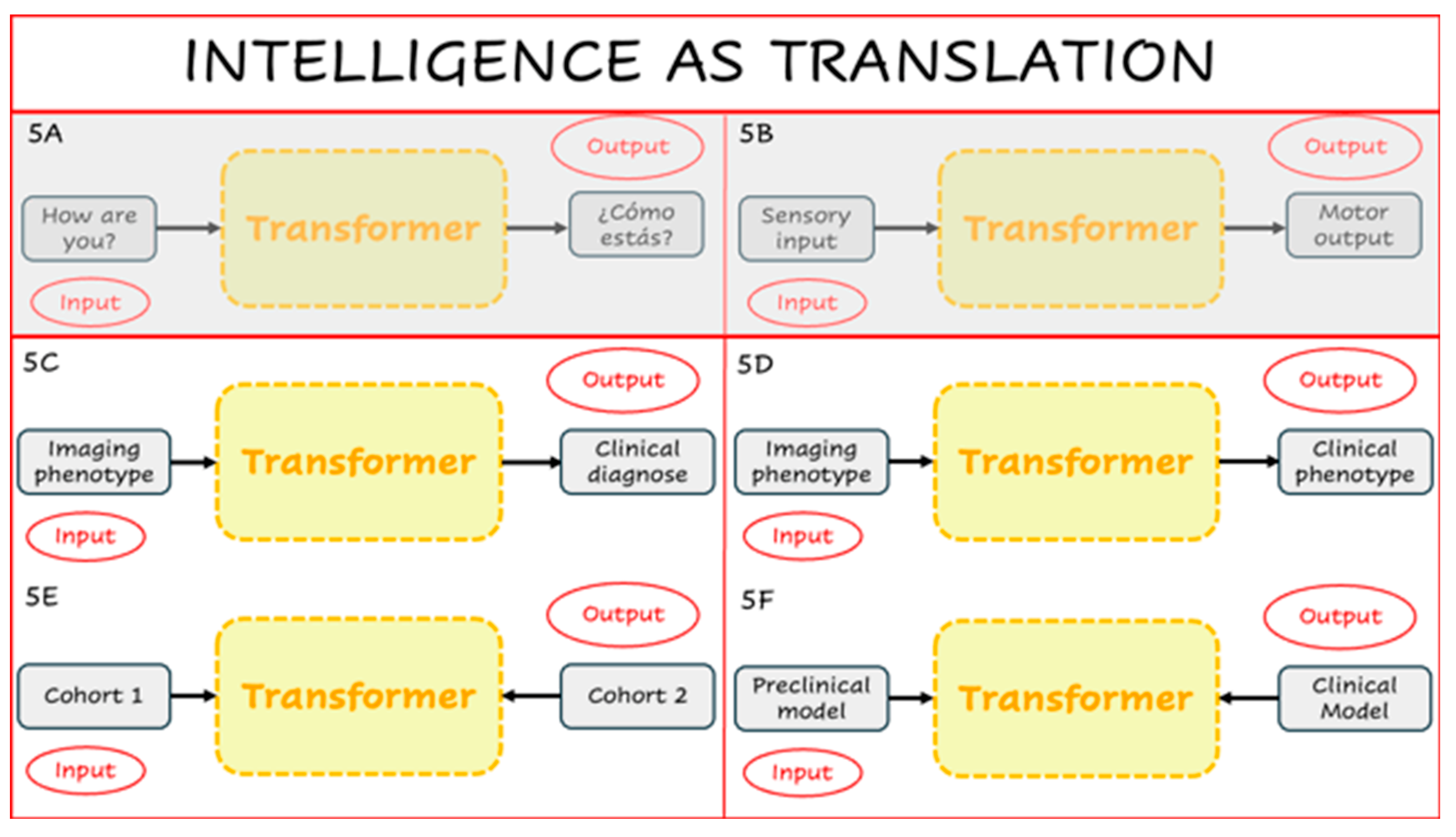

Beyond this specific example, Neuro-BOTs suggest a broader conceptual shift. Like their NLP counterparts, these models are designed to translate one representational space into another. In standard language models, Transformers convert an input sentence into a syntactically and semantically appropriate output (

Figure 5A). This mirrors a more general principle of cognition: human intelligence can itself be viewed as a process of translation, converting sensory input into meaningful behavioural or internal representations (

Figure 5B). Following this metaphor, inference problems in neuroscience can also be reframed as translational tasks. For instance, a Transformer might map imaging features to a clinical diagnosis (

Figure 5C), or translate between different neurobiological descriptors of the same condition (

Figure 5D). With appropriate encoder–decoder configurations, Neuro-BOTs could also align neural representations across patient subgroups (

Figure 5E), or evaluate how well a preclinical model (e.g., rodent) replicates human disease biology (

Figure 5F).

Such cross-domain mappings have traditionally relied on linear models of shared variance, including canonical correlation and partial least squares (McIntosh et al. 1996). Neuro-BOTs generalize these approaches into the nonlinear, high-dimensional regime—while retaining interpretability through fixed, biologically meaningful attention layers. In cognitive science, intelligence itself has been described as the act of translation between internal and external states (Fu and Liu 2024). Neuro-BOTs provide a formal architecture for enacting this transformation using architectures originally designed for language within the context of biologically grounded brain models. This opens new methodological territory: not only can Neuro-BOTs be used for classification or clustering, but also as scientific instruments for hypothesis generation and mechanistic inference. For instance, beyond PD, dopaminergic encoders may improve classification accuracy in schizophrenia or ADHD, where mesostriatal dysfunction is central to pathophysiology. Serotonergic priors could enhance modelling of depression and anxiety, potentially predicting treatment response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In disorders with altered arousal and fatigue - such as chronic fatigue syndrome, post-COVID19 syndrome, or post-traumatic stress disorder - histaminergic or noradrenergic encoders may capture latent phenotypes linked to neuromodulatory dysregulation. In Alzheimer’s disease, cholinergic priors may be particularly sensitive to early-stage degeneration. Furthermore, combining priors - for example, mitochondrial and neuromodulatory maps - via multi-head attention could reveal synergistic effects in disorders with multifactorial origins, such as bipolar disorder or multiple sclerosis. These hypotheses are empirically testable using public neuroimaging datasets, PET imaging validation, pharmacological challenge designs, and longitudinal response prediction. Such extensions not only broaden the clinical relevance of Neuro-BOTs but also support their use as generative tools for mechanistic hypothesis testing grounded in neurobiology.

Despite promising results, our study is not without limitations. The sample size is modest and not balanced between groups, which may limit generalizability. Additionally, our use of fixed biological priors, while interpretable, may constrain flexibility in other domains. Looking ahead, future work with larger and more diverse cohorts will be essential to validate these findings and expand the model’s applicability. Future work should expand the use of Neuro-BOTs beyond classification to more complex generative or time-series modelling tasks. This could include decoder modules for generative modelling, integration of multimodal inputs (e.g., PET-fMRI), or time-series prediction. The interpretability of biologically informed attention layers also opens new avenues for model-based hypothesis testing—such as quantifying the contribution of specific neurotransmitter systems to psychiatric or neurodegenerative phenotypes.

Ultimately, the value of Neuro-BOTs may lie not only in performance gains but in their ability to formalize new scientific questions - reframing brain modelling as a biologically grounded translation problem, and offering a principled approach to multiscale, mechanistic inference. Incorporating decoders would allow such full bidirectional inference, while multimodal attention maps—combining molecular, anatomical, and behavioural priors—could further improve both predictive accuracy and scientific insight. As these architectures evolve, their value may lie not only in performance, but in the ability to ask new kinds of biologically informed questions.

Acknowledgments

F.E.T. and D.M. are funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. G.d.A. is funded by the “London Interdisciplinary Doctoral Programme” (LIDo), funded by the BBSRC. E.D.F. and M.B. are funded by Masaryk University. MV is supported by EU funding within the Italian the Italian Ministry of University and Research PNRR “National Center for HPC, BIG DATA AND QUANTUM COMPUTING (Project no. CN00000013 CN1), the Italian Ministry of University and Research within the Complementary National Plan PNC DIGITAL LIFELONG PREVENTION - DARE (Project no PNC0000002_DARE), and by Fondo per il Programma Nazionale di Ricerca e Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN), (Project no 2022RXM3H7).

Conflicts of Interest

No competing interests are declared by all the authors.

Author Contributions

FET developed the concept, wrote part of the scripts, performed part of the computations and wrote the manuscript. DM, EDF, GdA, MF, MM wrote part of the scripts and performed part of the calculations. LB and SR coordinated the clinical experimental work and collected the data. MP, PE and MV contributed to the concept and the data analysis plan. All the authors contributed to the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

References

- Beliveau, V., M. Ganz, L. Feng, B. Ozenne, L. Højgaard, P. M. Fisher, C. Svarer, D. N. Greve, and G. M. Knudsen. 2017. ’A High-Resolution In Vivo Atlas of the Human Brain’s Serotonin System’, J Neurosci, 37: 120-28.

- Bethlehem, R. A. I., J. Seidlitz, S. R. White, J. W. Vogel, K. M. Anderson, C. Adamson, S. Adler, G. S. Alexopoulos, E. Anagnostou, A. Areces-Gonzalez, D. E. Astle, B. Auyeung, M. Ayub, J. Bae, G. Ball, S. Baron-Cohen, R. Beare, S. A. Bedford, V. Benegal, F. Beyer, J. Blangero, M. Blesa Cábez, J. P. Boardman, M. Borzage, J. F. Bosch-Bayard, N. Bourke, V. D. Calhoun, M. M. Chakravarty, C. Chen, C. Chertavian, G. Chetelat, Y. S. Chong, J. H. Cole, A. Corvin, M. Costantino, E. Courchesne, F. Crivello, V. L. Cropley, J. Crosbie, N. Crossley, M. Delarue, R. Delorme, S. Desrivieres, G. A. Devenyi, M. A. Di Biase, R. Dolan, K. A. Donald, G. Donohoe, K. Dunlop, A. D. Edwards, J. T. Elison, C. T. Ellis, J. A. Elman, L. Eyler, D. A. Fair, E. Feczko, P. C. Fletcher, P. Fonagy, C. E. Franz, L. Galan-Garcia, A. Gholipour, J. Giedd, J. H. Gilmore, D. C. Glahn, I. M. Goodyer, P. E. Grant, N. A. Groenewold, F. M. Gunning, R. E. Gur, R. C. Gur, C. F. Hammill, O. Hansson, T. Hedden, A. Heinz, R. N. Henson, K. Heuer, J. Hoare, B. Holla, A. J. Holmes, R. Holt, H. Huang, K. Im, J. Ipser, C. R. Jack, Jr., A. P. Jackowski, T. Jia, K. A. Johnson, P. B. Jones, D. T. Jones, R. S. Kahn, H. Karlsson, L. Karlsson, R. Kawashima, E. A. Kelley, S. Kern, K. W. Kim, M. G. Kitzbichler, W. S. Kremen, F. Lalonde, B. Landeau, S. Lee, J. Lerch, J. D. Lewis, J. Li, W. Liao, C. Liston, M. V. Lombardo, J. Lv, C. Lynch, T. T. Mallard, M. Marcelis, R. D. Markello, S. R. Mathias, B. Mazoyer, P. McGuire, M. J. Meaney, A. Mechelli, N. Medic, B. Misic, S. E. Morgan, D. Mothersill, J. Nigg, M. Q. W. Ong, C. Ortinau, R. Ossenkoppele, M. Ouyang, L. Palaniyappan, L. Paly, P. M. Pan, C. Pantelis, M. M. Park, T. Paus, Z. Pausova, D. Paz-Linares, A. Pichet Binette, K. Pierce, X. Qian, J. Qiu, A. Qiu, A. Raznahan, T. Rittman, A. Rodrigue, C. K. Rollins, R. Romero-Garcia, L. Ronan, M. D. Rosenberg, D. H. Rowitch, G. A. Salum, T. D. Satterthwaite, H. L. Schaare, R. J. Schachar, A. P. Schultz, G. Schumann, M. Schöll, D. Sharp, R. T. Shinohara, I. Skoog, C. D. Smyser, R. A. Sperling, D. J. Stein, A. Stolicyn, J. Suckling, G. Sullivan, Y. Taki, B. Thyreau, R. Toro, N. Traut, K. A. Tsvetanov, N. B. Turk-Browne, J. J. Tuulari, C. Tzourio, É Vachon-Presseau, M. J. Valdes-Sosa, P. A. Valdes-Sosa, S. L. Valk, T. van Amelsvoort, S. N. Vandekar, L. Vasung, L. W. Victoria, S. Villeneuve, A. Villringer, P. E. Vértes, K. Wagstyl, Y. S. Wang, S. K. Warfield, V. Warrier, E. Westman, M. L. Westwater, H. C. Whalley, A. V. Witte, N. Yang, B. Yeo, H. Yun, A. Zalesky, H. J. Zar, A. Zettergren, J. H. Zhou, H. Ziauddeen, A. Zugman, X. N. Zuo, E. T. Bullmore, and A. F. Alexander-Bloch. 2022. ’Brain charts for the human lifespan’, Nature, 604: 525-33.

- Betzel, R. F., A. Griffa, P. Hagmann, and B. Mišić. 2019. ’Distance-dependent consensus thresholds for generating group-representative structural brain networks’, Netw Neurosci, 3: 475-96.

- Braak, H., K. Del Tredici, U. Rüb, R. A. de Vos, E. N. Jansen Steur, and E. Braak. 2003. ’Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease’, Neurobiol Aging, 24: 197-211.

- Calhoun, V. D., T. Adali, G. D. Pearlson, and J. J. Pekar. 2001. ’A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis’, Hum Brain Mapp, 14: 140-51.

- Dafflon, J., W. H. L. Pinaya, F. Turkheimer, J. H. Cole, R. Leech, M. A. Harris, S. R. Cox, H. C. Whalley, A. M. McIntosh, and P. J. Hellyer. 2020. ’An automated machine learning approach to predict brain age from cortical anatomical measures’, Hum Brain Mapp, 41: 3555-66.

- Delaville, C., P. D. Deurwaerdère, and A. Benazzouz. 2011. ’Noradrenaline and Parkinson’s disease’, Front Syst Neurosci, 5: 31.

- Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. "BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding." In, 4171-86. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Doppler, C. E. J., J. A. M. Smit, M. Hommelsen, A. Seger, J. Horsager, M. B. Kinnerup, A. K. Hansen, T. D. Fedorova, K. Knudsen, M. Otto, A. Nahimi, P. Borghammer, and M. Sommerauer. 2021. ’Microsleep disturbances are associated with noradrenergic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease’, Sleep, 44.

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Neil Houlsby. 2020. ’An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale’, ArXiv, abs/2010.11929.

- Elman, Jeffrey L. 1990. ’Finding Structure in Time’, Cognitive Science, 14: 179-211.

- Esteban, O., C. J. Markiewicz, R. W. Blair, C. A. Moodie, A. I. Isik, A. Erramuzpe, J. D. Kent, M. Goncalves, E. DuPre, M. Snyder, H. Oya, S. S. Ghosh, J. Wright, J. Durnez, R. A. Poldrack, and K. J. Gorgolewski. 2019. ’fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI’, Nat Methods, 16: 111-16.

- Fagerholm, E. D., R. Leech, F. E. Turkheimer, G. Scott, and M. Brázdil. 2024. ’Estimating the energy of dissipative neural systems’, Cogn Neurodyn, 18: 3839-46.

- Fischl, B. 2012. ’FreeSurfer’, Neuroimage, 62: 774-81.

- Fu, Linling, and Lei Liu. 2024. ’What are the differences? A comparative study of generative artificial intelligence translation and human translation of scientific texts’, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11: 1236.

- Glasser, M. F., and D. C. Van Essen. 2011. ’Mapping human cortical areas in vivo based on myelin content as revealed by T1- and T2-weighted MRI’, J Neurosci, 31: 11597-616.

- Grubbs, F. E. 1950. ’Sample Criteria for Testing Outlying Observations’, Ann. Math. Statist. , 21: 27-58.

- Guyon, I. 2003. ’An Introduction to Variable and Feature Selection’, Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3: 1157-82.

- Hansen, J. Y., G. Shafiei, R. D. Markello, K. Smart, S. M. L. Cox, M. Nørgaard, V. Beliveau, Y. Wu, J. D. Gallezot, É Aumont, S. Servaes, S. G. Scala, J. M. DuBois, G. Wainstein, G. Bezgin, T. Funck, T. W. Schmitz, R. N. Spreng, M. Galovic, M. J. Koepp, J. S. Duncan, J. P. Coles, T. D. Fryer, F. I. Aigbirhio, C. J. McGinnity, A. Hammers, J. P. Soucy, S. Baillet, S. Guimond, J. Hietala, M. A. Bedard, M. Leyton, E. Kobayashi, P. Rosa-Neto, M. Ganz, G. M. Knudsen, N. Palomero-Gallagher, J. M. Shine, R. E. Carson, L. Tuominen, A. Dagher, and B. Misic. 2022. ’Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex’, Nat Neurosci, 25: 1569-81.

- Hauglund, Natalie L., Mie Andersen, Klaudia Tokarska, Tessa Radovanovic, Celia Kjaerby, Frederikke L. Sørensen, Zuzanna Bojarowska, Verena Untiet, Sheyla B. Ballestero, Mie G. Kolmos, Pia Weikop, Hajime Hirase, and Maiken Nedergaard. 2025. ’Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep’, Cell, 188: 606-22.e17.

- Hawrylycz, M. J., E. S. Lein, A. L. Guillozet-Bongaarts, E. H. Shen, L. Ng, J. A. Miller, L. N. van de Lagemaat, K. A. Smith, A. Ebbert, Z. L. Riley, C. Abajian, C. F. Beckmann, A. Bernard, D. Bertagnolli, A. F. Boe, P. M. Cartagena, M. M. Chakravarty, M. Chapin, J. Chong, R. A. Dalley, B. David Daly, C. Dang, S. Datta, N. Dee, T. A. Dolbeare, V. Faber, D. Feng, D. R. Fowler, J. Goldy, B. W. Gregor, Z. Haradon, D. R. Haynor, J. G. Hohmann, S. Horvath, R. E. Howard, A. Jeromin, J. M. Jochim, M. Kinnunen, C. Lau, E. T. Lazarz, C. Lee, T. A. Lemon, L. Li, Y. Li, J. A. Morris, C. C. Overly, P. D. Parker, S. E. Parry, M. Reding, J. J. Royall, J. Schulkin, P. A. Sequeira, C. R. Slaughterbeck, S. C. Smith, A. J. Sodt, S. M. Sunkin, B. E. Swanson, M. P. Vawter, D. Williams, P. Wohnoutka, H. R. Zielke, D. H. Geschwind, P. R. Hof, S. M. Smith, C. Koch, S. G. N. Grant, and A. R. Jones. 2012. ’An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome’, Nature, 489: 391-99.

- Jolliffe, I.T. 2002. Principal Component Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, Inc: New York).

- Kopeć, K., S. Szleszkowski, D. Koziorowski, and S. Szlufik. 2023. ’Glymphatic System and Mitochondrial Dysfunction as Two Crucial Players in Pathophysiology of Neurodegenerative Disorders’, Int J Mol Sci, 24.

- Lawn, T., A. Giacomel, D. Martins, M. Veronese, M. Howard, F. E. Turkheimer, and O. Dipasquale. 2024. ’Normative modelling of molecular-based functional circuits captures clinical heterogeneity transdiagnostically in psychiatric patients’, Commun Biol, 7: 689.

- Lawn, T., M. A. Howard, F. Turkheimer, B. Misic, G. Deco, D. Martins, and O. Dipasquale. 2023. ’From neurotransmitters to networks: Transcending organisational hierarchies with molecular-informed functional imaging’, Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 150: 105193.

- McIntosh, A. R., F. L. Bookstein, J. V. Haxby, and C. L. Grady. 1996. ’Spatial pattern analysis of functional brain images using partial least squares’, Neuroimage, 3: 143-57.

- Mehta, Kahini, Taylor Salo, Thomas J. Madison, Azeez Adebimpe, Danielle S. Bassett, Max Bertolero, Matthew Cieslak, Sydney Covitz, Audrey Houghton, Arielle S. Keller, Jacob T. Lundquist, Audrey Luo, Oscar Miranda-Dominguez, Steve M. Nelson, Golia Shafiei, Sheila Shanmugan, Russell T. Shinohara, Christopher D. Smyser, Valerie J. Sydnor, Kimberly B. Weldon, Eric Feczko, Damien A. Fair, and Theodore D. Satterthwaite. 2024. ’XCP-D: A robust pipeline for the post-processing of fMRI data’, Imaging Neuroscience, 2: 1-26.

- Mendes, Sergio Leonardo, Walter Hugo Lopez Pinaya, Pedro Mario Pan, Ary Gadelha, Sintia Belangero, Andrea Parolin Jackowski, Luis Augusto Rohde, Euripedes Constantino Miguel, and João Ricardo Sato. 2024. ’GPT-based normative models of brain sMRI correlate with dimensional psychopathology’, Imaging Neuroscience, 2: 1-15.

- Mosharov, E. V., A. M. Rosenberg, A. S. Monzel, C. A. Osto, L. Stiles, G. B. Rosoklija, A. J. Dwork, S. Bindra, Y. Zhang, M. Fujita, M. B. Mariani, M. Bakalian, D. Sulzer, P. L. De Jager, V. Menon, O. S. Shirihai, J. J. Mann, M. Underwood, M. Boldrini, M. T. de Schotten, and M. Picard. 2024. ’A Human Brain Map of Mitochondrial Respiratory Capacity and Diversity’, bioRxiv.

- Paluszek, Michael, Stephanie Thomas, and Eric Ham. 2022. ’MATLAB Machine Learning Toolboxes.’ in Michael Paluszek, Stephanie Thomas and Eric Ham (eds.), Practical MATLAB Deep Learning: A Projects-Based Approach (Apress: Berkeley, CA).

- Petri, G., P. Expert, F. Turkheimer, R. Carhart-Harris, D. Nutt, P. J. Hellyer, and F. Vaccarino. 2014. ’Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks’, J R Soc Interface, 11: 20140873.

- Pudjihartono, N., T. Fadason, A. W. Kempa-Liehr, and J. M. O’Sullivan. 2022. ’A Review of Feature Selection Methods for Machine Learning-Based Disease Risk Prediction’, Front Bioinform, 2: 927312.

- Radford, Alec, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. 2018. ’Improving language understanding by generative pre-training’.

- Radford, Alec, Jeff Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, and Ilya Sutskever. 2019. "Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners." In.

- Razavi, Ali, Aaron Van den Oord, and Oriol Vinyals. 2019. ’Generating diverse high-fidelity images with vq-vae-2’, Advances in neural information processing systems, 32.

- Schaefer, A., R. Kong, E. M. Gordon, T. O. Laumann, X. N. Zuo, A. J. Holmes, S. B. Eickhoff, and B. T. T. Yeo. 2018. ’Local-Global Parcellation of the Human Cerebral Cortex from Intrinsic Functional Connectivity MRI’, Cereb Cortex, 28: 3095-114.

- Scholtens, L. H., M. A. de Reus, S. C. de Lange, R. Schmidt, and M. P. van den Heuvel. 2018. ’An MRI Von Economo - Koskinas atlas’, Neuroimage, 170: 249-56.

- Sporns, O. 2013. ’Structure and function of complex brain networks’, Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 15: 247-62.

- Surmeier, D. J., J. A. Obeso, and G. M. Halliday. 2017. ’Selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson disease’, Nat Rev Neurosci, 18: 101-13.

- van den Oord, Aäron, Oriol Vinyals, and Koray Kavukcuoglu. 2017. ’Neural discrete representation learning. CoRR abs/1711.00937 (2017)’, arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.00937.

- Van Essen, D. C., S. M. Smith, D. M. Barch, T. E. Behrens, E. Yacoub, and K. Ugurbil. 2013. ’The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: an overview’, Neuroimage, 80: 62-79.

- Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. ’Attention Is All You Need’.

- Wagstyl, K., S. Larocque, G. Cucurull, C. Lepage, J. P. Cohen, S. Bludau, N. Palomero-Gallagher, L. B. Lewis, T. Funck, H. Spitzer, T. Dickscheid, P. C. Fletcher, A. Romero, K. Zilles, K. Amunts, Y. Bengio, and A. C. Evans. 2020. ’BigBrain 3D atlas of cortical layers: Cortical and laminar thickness gradients diverge in sensory and motor cortices’, PLoS Biol, 18: e3000678.

- Weinshenker, D. 2018. ’Long Road to Ruin: Noradrenergic Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Disease’, Trends Neurosci, 41: 211-23.

- Yarkoni, T., R. A. Poldrack, T. E. Nichols, D. C. Van Essen, and T. D. Wager. 2011. ’Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data’, Nat Methods, 8: 665-70.

- Zilles, K., and N. Palomero-Gallagher. 2017. ’Multiple Transmitter Receptors in Regions and Layers of the Human Cerebral Cortex’, Front Neuroanat, 11: 78.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).