Highlight

▪ Fifteen new charged triazoles with quaternized triazole cores were synthesized with high yields and confirmed structural integrity.

▪ Derivatives 9 and 14 exhibited nanomolar BChE inhibition, outperforming the reference drug donepezil.

▪ Compound 9 also showed potent anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting TNF-α production in LPS-stimulated PBMCs.

▪ In silico predictions and molecular docking confirmed stable and specific enzyme binding with low mutagenic potential.

1. Introduction

Cholinesterases are key enzymes responsible for hydrolyzing acetylcholine (ACh) and butyrylcholine (BCh), thereby terminating cholinergic transmission. The two principal types are acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which is predominantly found in synaptic clefts, and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), which is more widely distributed in plasma and non-neuronal tissues [

1]. Pharmacological inhibition of these enzymes has therapeutic applications, particularly in treating Alzheimer's disease (AD), myasthenia gravis, and acute organophosphate poisoning [

2]. Non-selective cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) target both AChE and BChE, making them a versatile class of compounds with expanding clinical and experimental relevance. A notable area of growing interest is the role of molecular charge, especially the therapeutic advantages offered by positively charged (cationic) molecules.

ChEIs function by blocking the degradation of ACh, thereby enhancing cholinergic signaling. This mechanism is exploited in the symptomatic treatment of neurodegenerative conditions such as AD, where cholinergic deficits are prominent [

3,

4]. Non-selective inhibitors, by acting on both AChE and BChE, may confer broader efficacy. In the later stages of AD, the activity of BChE increases and may compensate for the decline in AChE activity, highlighting the importance of targeting both enzymes [

5,

6]. Approved ChEIs such as donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine have demonstrated central efficacy, while peripheral inhibitors like neostigmine play a vital role in anesthesia and neuromuscular disorders [

7,

8].

Non-selective cholinesterase inhibitors encompass both classic compounds, such as physostigmine and neostigmine, and newer experimental agents that combine reversible and irreversible properties. Many of these molecules are designed to contain quaternary ammonium groups, which confer a permanent positive charge. This positive charge renders the molecules hydrophilic and significantly limits their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), resulting in predominantly peripheral effects [

9]. Charged ChEIs, particularly those containing quaternary ammonium groups, offer several pharmacological and safety advantages in clinical applications. Due to their polar nature, these molecules exhibit poor penetration through the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is advantageous in clinical settings where central nervous system (CNS) side effects are undesirable [

10,

11].

Moreover, the restricted CNS distribution of charged molecules enhances their suitability for peripheral therapeutic targets. This is particularly beneficial in conditions such as myasthenia gravis or in the reversal of neuromuscular blockade following surgery, where a peripheral mode of action is preferred [

8,

12]. Their limited distribution within the CNS also contributes to a reduced risk of neurotoxicity and convulsions, making them safer for use in acute or emergency settings [

13,

14]. Additionally, their hydrophilic nature leads to predictable pharmacokinetics, with distribution confined mainly to extracellular fluids, facilitating consistent plasma concentrations and easier dosing adjustments [

15]. Despite their advantages, charged ChEIs have several limitations. Their inability to cross the BBB makes them ineffective for treating CNS-related disorders such as AD unless administered through alternative delivery methods or modified chemically to enhance CNS penetration [

16]. Clinically, several charged non-selective ChEIs are in use. Neostigmine and pyridostigmine are commonly used in anesthesiology and for treating myasthenia gravis, while edrophonium serves a diagnostic purpose by transiently improving muscle strength. Ambenonium, though now less commonly used, represents another example of a charged molecule that demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of limiting drug distribution to the peripheral nervous system [

17]. These drugs exemplify how charged structures can provide targeted therapeutic action while minimizing central toxicity.

Recent advances in medicinal chemistry aim to overcome the limitations of charged molecules while retaining their advantages. One approach involves designing hybrid or prodrug forms that temporarily mask the charge to facilitate BBB penetration, with activation occurring at the target site [

16]. Research also continues into dual-action inhibitors that combine ChE inhibition with anti-oxidant or anti-amyloid properties, which could provide multifunctional benefits in neurodegenerative diseases [

5,

11]. Efforts are also ongoing to develop tissue-specific delivery systems and nanocarriers that allow controlled distribution of polar ChEIs [

18]. Non-selective cholinesterase inhibitors with charged structures offer considerable therapeutic advantages, particularly in the peripheral nervous system, where CNS penetration is undesirable. Their hydrophilic and cationic nature allows for targeted, predictable, and relatively safe pharmacological profiles. However, their limited CNS access remains a significant obstacle in treating brain-related disorders. Ongoing research into prodrug strategies and hybrid molecules holds promise for extending the utility of charged ChEIs in broader clinical contexts.

In our previous research [

19], pairs of uncharged thienobenzo-triazoles and their corresponding charged salts were prepared to examine the role of the positive charge on the nitrogen of the triazole ring in interactions within the active site of the cholinesterase enzymes. The intention was also to compare the selectivity of 1,2,3-triazolium salts with that of their uncharged analogs. Uncharged thienobenzo-triazoles

I (

Figure 1) preferred inhibition of BChE over AChE. Conversion to the salt form (structure

II,

Figure 1) significantly increased inhibition of AChE (the most active IC

50 4.4 μM), and, to a good extent, also of BChE (the most active IC

50 0.47 μM). It was concluded that the most important structural feature for thienobenzo-triazoles is the presence or absence of charge. Triazole salts [

19] were shown to be dual inhibitors, whose potency of inhibition varies depending on the substituents on the thiophene and triazole heterocycles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Remarks

NMR spectra were obtained using either a Bruker AV300 or AV600 spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) with a 5 mm probe. Standard

1H and proton-decoupled

13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded at a frequency of 600.130 MHz for

1H, and 75.432 and 150.903 MHz for

13C. Chemical shifts (

δ/ppm) for both

1H and

13C NMR spectra were referenced to the tetramethylsilane (TMS) signal. All spectra were measured in deuterated chloroform (CD

3OD) at 25 °C. Photochemical reactions were carried out in a 50.0 mL solution in quartz cuvettes that transmitted light. For this purpose, a Luzchem photochemical reactor equipped with UV lamps (16) with a wavelength of 300 nm was used. All solvents used in this work were purified by distillation and were commercially available. The phosphonium salts were synthesized in our laboratory, and 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1

H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde used was previously synthesized in our laboratory [

20]. Reaction progress was monitored via thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel-coated plates (0.2 mm, 60/Kieselguhr F254), placed in 10 mL of the appropriate solvent system. After each synthesis, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C, and then a certain amount of diethyl ether was added to precipitate the product. The resulting suspension was centrifuged (Centrifuge Eba 20, Hettich, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 2 x 3000 rpm for 10 minutes and then at 5 x 5000 rpm for 10 minutes. It was then decanted and finally evaporated. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analyses were performed on a MALDI TOF/TOF analyzer, using an Nd:YAG laser at 355 nm with a fitting rate of 200 Hz.

2.2. Synthesis of Bromide Salts 1–15

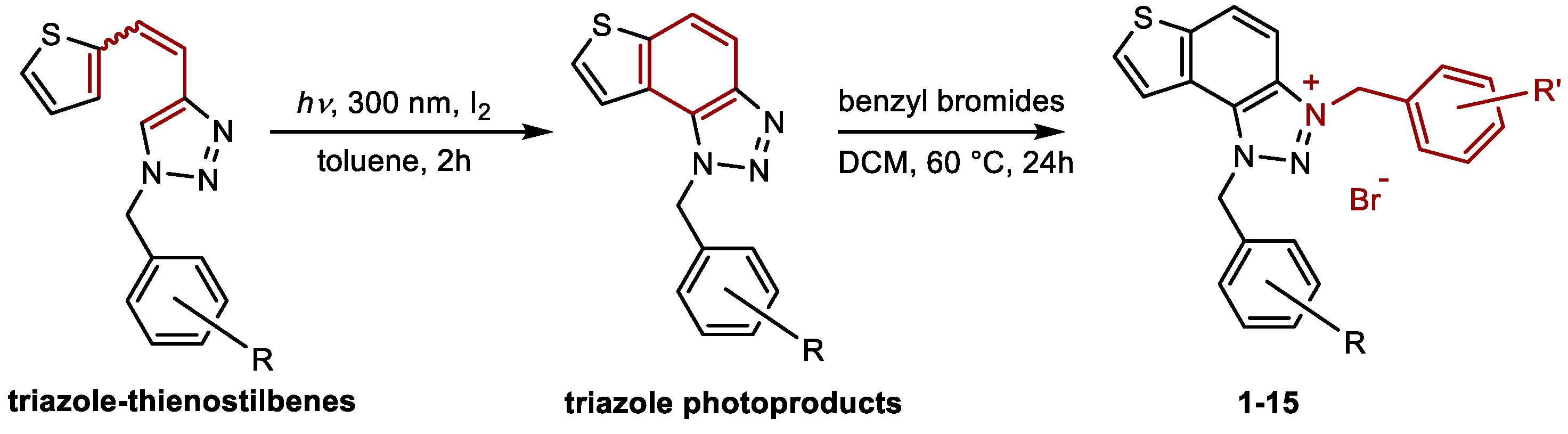

Triazole photoproducts (

Scheme 1) previously developed by our group [

19,

21,

22,

23] served as the starting materials for the synthesis of bromide salts

1–15. In a small vial, triazole analogues were dissolved in 0.6 mL of dry DCM and then purged briefly with argon. Furthermore, 20 eq of the corresponding benzyl bromide was added, and the reaction vial was then stirred in an oil bath at 60 °C for 24 h. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C and then approximately 5 mL of diethyl ether was added, forming a white suspension. At the end, the suspension was centrifuged 2 x 3 000 rpm for 10 minutes and more 5 x 5 000 rpm for 10 minutes, decanted and evaporated using a rotary evaporator. According to NMR analyses, all bromide salts 1–15 were successfully synthesized in mostly high yields.

1-(4-chlorobenzyl)-3-(4-methylbenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

1): 9 mg (isolated 69%), white powder; m.p. 117-118 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.51 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.10–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.43 (m, 6H), 7.28 (d,

J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.50 (s, 2H), 6.25 (s, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 143.0, 139.7, 135.1, 134.0, 133.1, 130.9, 130.7, 129.7, 129.4, 129.2, 129.0, 128.5, 126.9, 123.1, 120.4, 107.9, 55.3, 55.2, 19.8; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

23H

19ClN

3S

+ Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 404.0988, and [M + H]

+measured = 404.0997.

1,3-bis(4-chlorobenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

2): 13 mg (isolated 96%), white powder; m.p. 108-110 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.54 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d,

J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.13–8.08 (m, 2H), 7.57 (d,

J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.50–7.43 (m, 6H), 6.50 (s, 2H), 6.30 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 143.1, 135.1, 135.40, 134.2, 133.2, 131.0, 130.7, 130.6, 130.3, 129.5, 129.4, 129.2, 127.2, 123.2, 120.4, 107.7, 55.4, 54.4.; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

22H

16Cl

2N

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 424.0442, and [M + H]

+measured = 424.0448.

1,3-bis(4-chlorobenzyl)-7-methyl-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

3): 10 mg (isolated 95%), white powder; m.p. 105-107 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.39 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d,

J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.49–7.43 (m, 6H), 6.45 (s, 2H), 6.26 (s, 2H), 2.77 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 150.2, 131.7, 131.0, 130.6, 129.8, 129.4, 119.9, 108.0, 55.7, 56.7, 16.1 (several signals are missing due to the small quantity of the sample); HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

23H

18C

l2N

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 438.0598, and [M + H]

+measured = 438.0610.

3-benzyl-1-(3-chlorobenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

4): 5 mg (isolated 27%), white powder; m.p. 119-120 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.53 (d,

J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d,

J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.13–8.09 (m, 3H), 7.57 (d,

J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.49–7.40 (m, 5H), 6.52 (s, 2H), 6.31 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 143.1, 135.0, 134.1, 133.2, 132.1, 131.0, 130.6, 129.4, 129.3, 129.1, 128.5, 127.8, 127.0, 126.1, 123.1, 120.4, 107.8, 55.3; MS (ESI) (

m/z, %) for C

22H

17ClN

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+ 391 (100), 250 (85).

1-(3-chlorobenzyl)-3-(4-methylbenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

5): 11 mg (isolated 57%), white powder; m.p. 104-105 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.51 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d,

J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 8.12–8.08 (m, 2H), 7.53–7.36 (m, 6H), 7.28 (d,

J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.51 (s, 2H), 6.26 (s, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 144.5, 141.1, 136.4, 135.5, 135.4, 134.5, 132.4, 132.0, 131.1, 130.7, 130.0, 129.2, 128.4, 127.5, 124.5, 121.8, 109.3, 56.7, 56.6, 21.2; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

23H

19ClN

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 404.0988, and [M + H]

+measured = 404.0998.

1-(3-chlorobenzyl)-3-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

6): 8 mg (isolated 40%), white powder; m.p. 111-113 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.55 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.14–8.10 (m, 2H), 7.58 (d,

J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (t,

J = 1.5, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.41 (m, 4H), 7.38 (dt,

J = 1.5, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (s, 2H), 6.28 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 143.2, 135.4, 134.9, 134.1, 133.8, 133.2, 130.6, 130.3, 129.2, 129.3, 127.9, 127.2, 126.2, 123.1, 120.3 55.3, 54.3; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

22H

16Cl

2N

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 424.0442, and [M + H]

+measured = 424.0447.

1-(3-chlorobenzyl)-3-(4-nitrobenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

7): 9 mg (isolated 42%), white powder; m.p. 125-126 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.57 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (d,

J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 8.27 (d,

J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.15–8.11 (m, 3H), 7.80–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.38 (m, 3H) 6.53 (s, 2H), 6.47 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 140.3, 136.4, 135.9, 135.3, 134.8, 132.1, 131.1, 130.6, 130.7, 129.4, 128.8, 127.7, 125.4, 124.6, 123.9, 121.8, 110.0, 56.9, 55.4; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

22H

16ClN

4O

2S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 435.0682, and [M + H]

+measured = 435.0690.

3-benzyl-1-(3-fluorobenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

8): 7 mg (isolated 48%), white powder; m.p. 103-104 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.53 (d,

J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.13–8.05 (m, 3H), 7.58 (dd,

J = 1.8, 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.49–7.42 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.21 (m, 2H), 6.53 (s, 2H), 6.31 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 145.3 (d,

JCF = 236.7 Hz), 143.7, 139.1, 138.0, 137.1, 134.9, 134.6, 133.6, 133.4, 133.1, 132.9, 132.5, 130.9, 127.1, 124.3, 111.8, 59.3, 59.2 (signals for four quaternary C are missing); HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

22H

17FN

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 374.1127, and [M + H]

+measured = 374.1131.

1-(3-fluorobenzyl)-3-(4-methylbenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

9): 14 mg (isolated 93%), white powder; m.p. 116-117 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.51 (dd,

J = 0.7, 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d,

J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 8.12–8.05 (m, 2H), 7.50–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.30 – 7.22 (m, 4H), 7.19–7.15 (m, 1H), 6.53 (s, 2H), 6.27 (s, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 167.1 (d,

JCF = 246.2 Hz), 147.0, 143.7, 138.4 (d,

JCF = 8.0 Hz), 138.0, 137.0, 135.0 (d,

JCF = 8.7 Hz), 133.6, 132.9, 132.5, 130.9, 127.4, 127.3, 127.0, 124.3, 119.9 (d,

JCF = 21.7 Hz), 118.5 (d,

JCF = 23.3 Hz), 59.3, 59.2, 23.7; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

23H

19FN

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 388.1284, and [M + H]

+measured = 388.1292.

3-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1-(3-fluorobenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

10): 7 mg (isolated 45%), white powder; m.p. 110-112 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.55 (dd,

J = 0.7, 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.14–8.10 (m, 1H), 8.08–8.06 (m, 1H), 7.58 (d,

J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.50–7.44 (m, 3H), 7.29–7.15 (m, 3H), 6.53 (s, 2H), 6.31 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 143.2, 136.3 (d,

JCF = 216.2 Hz), 135.4 , 134.2, 133.6, 133.2, 132.7, 131.1 (d,

JCF = 8.1 Hz), 130.7, 130.3, 129.2, 127.2, 123.5, 123.1, 120.4, 115.9 (d,

JCF = 21.9 Hz), 114.6 (d,

JCF = 23.2 Hz), 107.7, 55.4, 54.5 (signals for 2 quaternary C are missing); HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

22H

16ClFN

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 408.0738, and [M + H]

+measured = 408.0745

.

3-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1-(3-methylbenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

11): 8 mg (isolated 94%), white powder; m.p. 122-123 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.53 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d,

J =5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.14–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.58 (d,

J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d,

J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.32–7.17 (m, 4H), 6.46 (s, 2H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 2.32 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 144.5, 140.7, 136.8, 135.6, 134.5, 133.2, 132.4, 131.7, 131.2, 130.6, 130.4, 129.4, 128.5, 125.9, 124.6, 122.0, 109.1, 55.8, 57.5, 21.3; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

23H

19ClN

3S

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 404.0988, and [M + H]

+measured = 404.0996

.

1-(4-methoxybenzyl)-3-(4-methylbenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

12): 9 mg (isolated 95%), white powder; m.p. 120-122 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.49 (d,

J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.15–8.11 (m, 1H), 8.06 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d,

J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d,

J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d,

J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d,

J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.42 (s, 2H), 6.24 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 142.9, 139.7, 134.3, 133.9, 132.9, 130.8, 129.7, 129.2, 129.1, 128.4, 126.8, 123.6, 123.2, 120.6, 114.3, 107.8, 65.4, 54.3, 53.4, 19.8; HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

24H

22N

3OS

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 400.1484, and [M + H]

+measured = 400.1487.

3-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1-(4-methoxybenzyl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

13): 7 mg (isolated 74%), white powder; m.p. 124-125 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.52 (dd,

J = 0.7, 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d,

J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d,

J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (d,

J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d,

J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.42 (s, 2H), 6.29 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 134.5, 132.3, 131.6, 130.7, 130.6, 128.5, 125.5, 124.9, 122.1, 115.8, 109.1, 57.3, 55.8, 55.7 (signals for 5 quaternary C are missing); HRMS (ESI) (

m/z) for C

23H

19ClN

3OS

+Br

-: [M + H]

+calcd = 420.0937, and [M + H]

+measured = 420.0943.

1-allyl-3-benzyl-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

14): 8 mg (isolated 64%), white powder; m.p. 101-102 °C;

1H NMR (CD

3OD, 300 MHz)

δ/ppm: 8.52 (d,

J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d,

J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.14–8.05 (m, 2H), 7.61–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.49–7.41 (m, 2H), 6.40–6.32 (m, 1H), 6.30 (s, 2H), 5.92 (d,

J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 5.52 (d,

J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 5.41 (d,

J = 17.1 Hz, 1H);

13C NMR (CD

3OD, 75 MHz)

δ/ppm: 142.9, 133.9, 133.02, 132.1, 129.3, 129.1, 128.8, 128.5, 126.9, 123.2, 120.7, 120.2, 114.5, 107.7, 55.2, 54.9; MS (EI) (

m/z, %) for C

18H

16N

3S

+Br

-: 306 (100).

3-benzyl-1-(prop-1-en-1-yl)-1

H-thieno[3',2':3,4]benzo[1,2-

d][

1,

2,

3]triazol-3-ium bromide (

15): 11 mg (isolated 51%), yellow oil; mixture of

cis- and

trans-isomer; MS (EI) (

m/z, %) for C

18H

16N

3S

+Br

-: 306 (100).

2.3. In Vitro Cholinesterase Inhibition Activity Measurements

The inhibition of AChE and BChE was determined using a modified Ellman’s spectrophotometric assay [

24]. Enzymes AChE (EC 3.1.1.7,

Electrophorus electricus, Type V-S) and BChE (EC 3.1.1.8, equine serum) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All the remaining chemicals: Trisma base (2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol), acetylthiocholine iodide (ATChI),

S-butyrylthiocholine iodide (BTChI), and standard Donepezil, were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, while Ellman's reagent 5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was sourced from Zwijndrecht (Antwerpen, Belgium). The various concentrations of the tested compounds dissolved in ethanol were added (10 µL) to 180 µL of Tris buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), 10 µL of enzyme solution (final concentration 0.03 U/mL), and 10 µL of DTNB (final concentration 0.3 mM). The enzymatic reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 µL of substrate ATChI or BTChI, resulting in a final substrate concentration of 0.5 mM. Non-enzymatic hydrolysis was measured as a blank for control measurement without inhibitors. The non-enzymatic hydrolysis reaction with added inhibitor was used as a blank for the samples. The enzyme was replaced with an equivalent amount of buffer. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm over a 5-minute period at room temperature using a 96-well microplate reader (BioTek 800TSUV Absorbance Reader, Agilent). All measurements were conducted in triplicate. The percentage of inhibition was calculated using the following equation: Inhibition (%) = [(

AC –

AT)/

AC] × 100, where AC represents the enzyme activity in the absence of the test sample, and AT represents the enzyme activity in the presence of the test compound. Inhibition data were used to calculate the IC

50 value by nonlinear fitting of the inhibitor concentration versus response. The inhibitory activity of ethanol was also measured, and its contribution to inhibition was subtracted. The IC

50 value is represented as a mean value of three measurements ± standard deviation. Selectivity index is calculated as IC

50(AChE)/IC

50(BChE).

2.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The effect of triazole salts

1–15 on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production was assessed as described previously [

25]. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from buffy coats obtained from healthy adult volunteers and resuspended in RPMI1640 medium (Capricorn Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Biowest), 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco), and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco). In a 96-well plate, 2×10

5 PBMCs were seeded per well. Triazole salts

1–15 were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma), and three-fold serial dilutions in DMSO were prepared and added to cells, with a starting concentration of 100 µM. After 1 h pre-incubation with triazole salts

1–15, cells were stimulated with 1 ng/mL LPS from

E. coli 0111:B4 (Sigma). Cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2, followed by the collection of supernatants for the measurement of TNF-α and assessment of cell viability. To analyse cell viability, CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, and signals obtained in compound-treated wells were compared with signals in LPS-stimulated vehicle-treated samples.

TNF-α concentration in supernatants was measured by ELISA using antibodies and recombinant human TNF-α protein (standard) from R&D Systems. Lumitrac 600 384-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) were coated with 1 µg/mL of TNF-α capture antibody diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco) overnight at 4°C. The next day, plates were blocked with 5% sucrose (Kemika) in assay diluent (1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS) for 4 hours at room temperature (RT). After the blocking step, triazole salts 1–15 samples and standards were added to the plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Afterwards, 250 ng/mL of TNF-α detection antibody was added to the wells, followed by a 2-hour incubation at RT. Finally, after the plates were incubated with streptavidin-HRP (Invitrogen), chemiluminescence ELISA Substrate (Roche) was added to the wells, and luminescence was measured using an EnVision 2105 multilabel reader (Revvity). Measured luminescence was used to calculate the concentrations of TNF-α in the supernatants by interpolation from the standard curve. Percentages of inhibition were calculated from the obtained cytokine concentrations, and IC50 values were determined using GraphPad Prism v9 software with a nonlinear regression curve fit (four parameters with variable slope).

2.5. Computational Details

Conformational analysis and geometry optimization of two compounds selected for the docking study were performed using the Gaussian16 program package [

26], employing the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory. The most stable conformers were used as ligands in the molecular docking study, which was conducted with the AutoDock4 suite [

27]. Crystal structures 4EY7.pdb and 1P0I.pdb, corresponding to AChE and BChE, respectively, were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank [

28,

29] and prepared for docking (non-amino acid residues were removed, polar hydrogens added, and Kollman charges assigned). The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm was employed for docking, with 25 runs generated per ligand, while the enzyme residues were kept rigid.

2.6. ADME-Tox Predictions

pkCSM is a free-to-use machine learning platform that predicts small-molecule pharmacokinetic properties using graph-based signatures. It includes 28 models that cover key ADMET properties, including factors such as permeability, solubility, absorption, distribution in the body, interactions with metabolic enzymes, excretion, and various toxicity measures. Swiss ADME allows you to compute physicochemical descriptors for free, as well as predict ADME parameters, pharmacokinetic properties, drug-like nature, and medicinal chemistry friendliness for one or multiple small molecules to support drug discovery. AdmetSAR 3.0 is a free-access chemical risk assessment tool [

30]. ADMETLAb 3.0 provides easy access to comprehensive, accurate, and efficient predictions of ADMET profiles for chemicals. These predictions are based on a high-quality database of 0.37 million entries spanning 77 endpoints and the Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) framework. For this paper, all triazole salts 1–15 were evaluated using multiple tools, and predictions of key features for the lead molecules were presented.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Charged Thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazoles 1–15

New charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazoles

1–

15 were prepared to investigate their potential as AChE and BChE inhibitors based on the previous encouraging results [

19]. To achieve this, targeted triazole-thienostilbenes (

Scheme 1) were prepared through a series of consecutive reactions [

19]. Mixtures of the geometrical isomers of triazole-thienostilbenes were subjected to photochemical cyclization, yielding triazole photoproducts, which served as the starting structures for preparing charged triazole benzyl salts

1–

15. The photoproducts were converted into triazole salts 1–15 as targeted products using the corresponding benzyl bromides. According to NMR analyses, all bromide salts

1–

15 were successfully synthesized in mostly high utilizations (

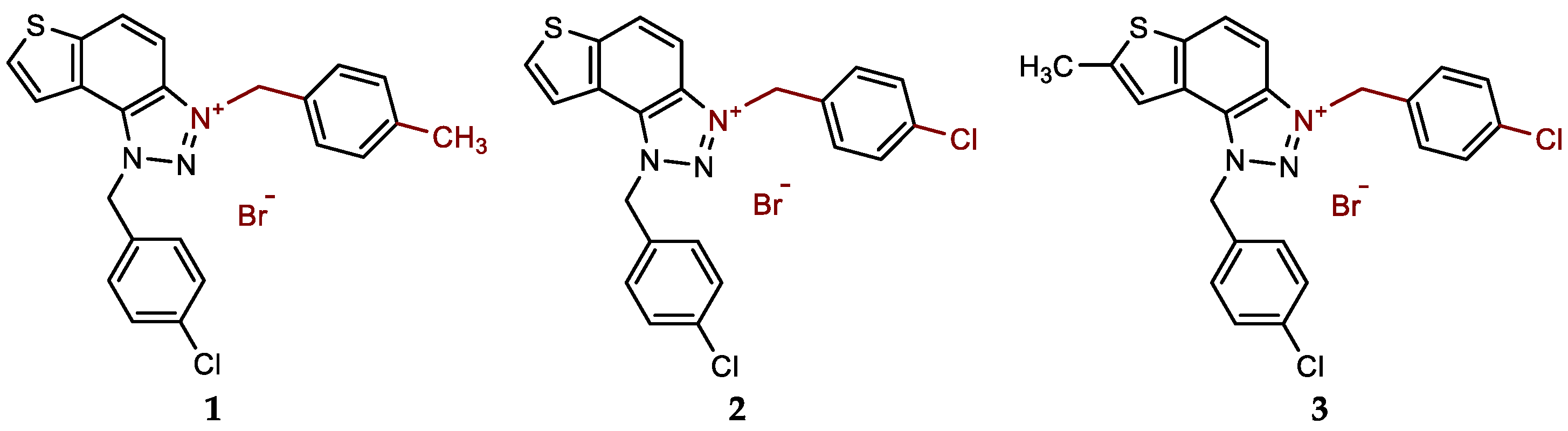

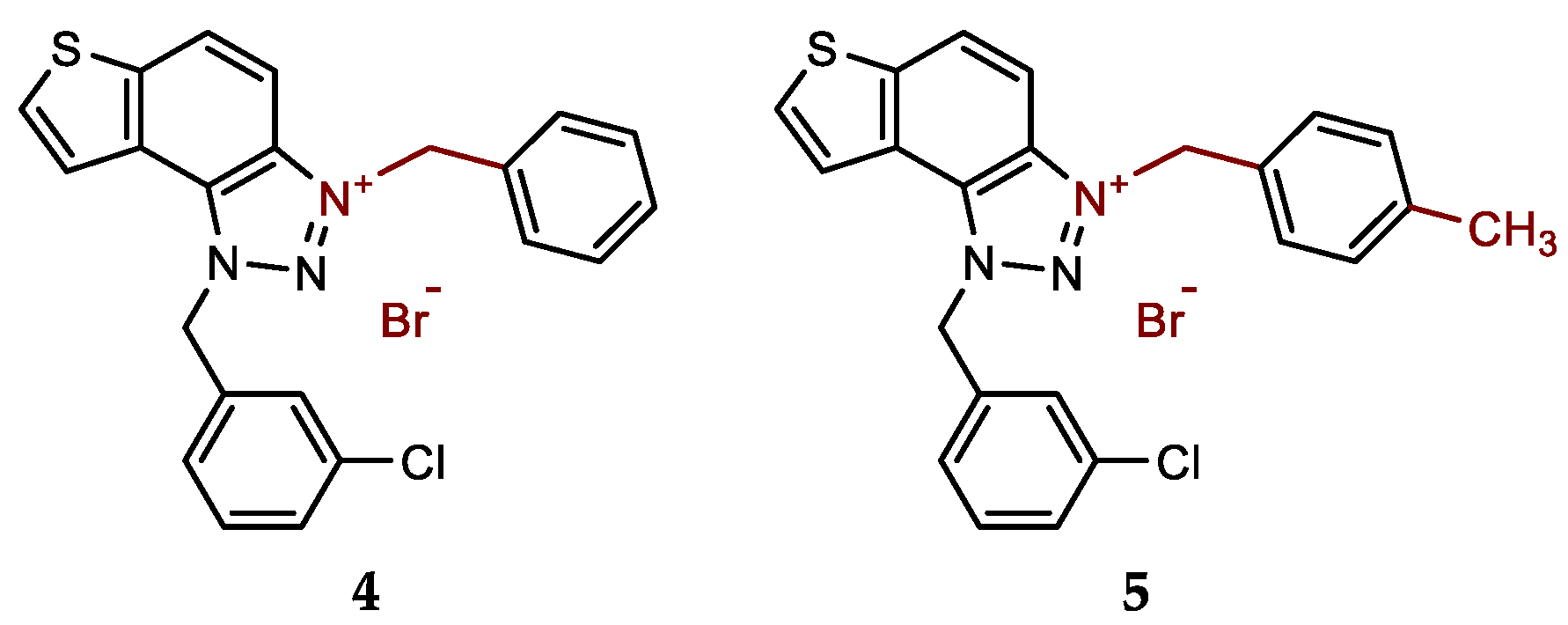

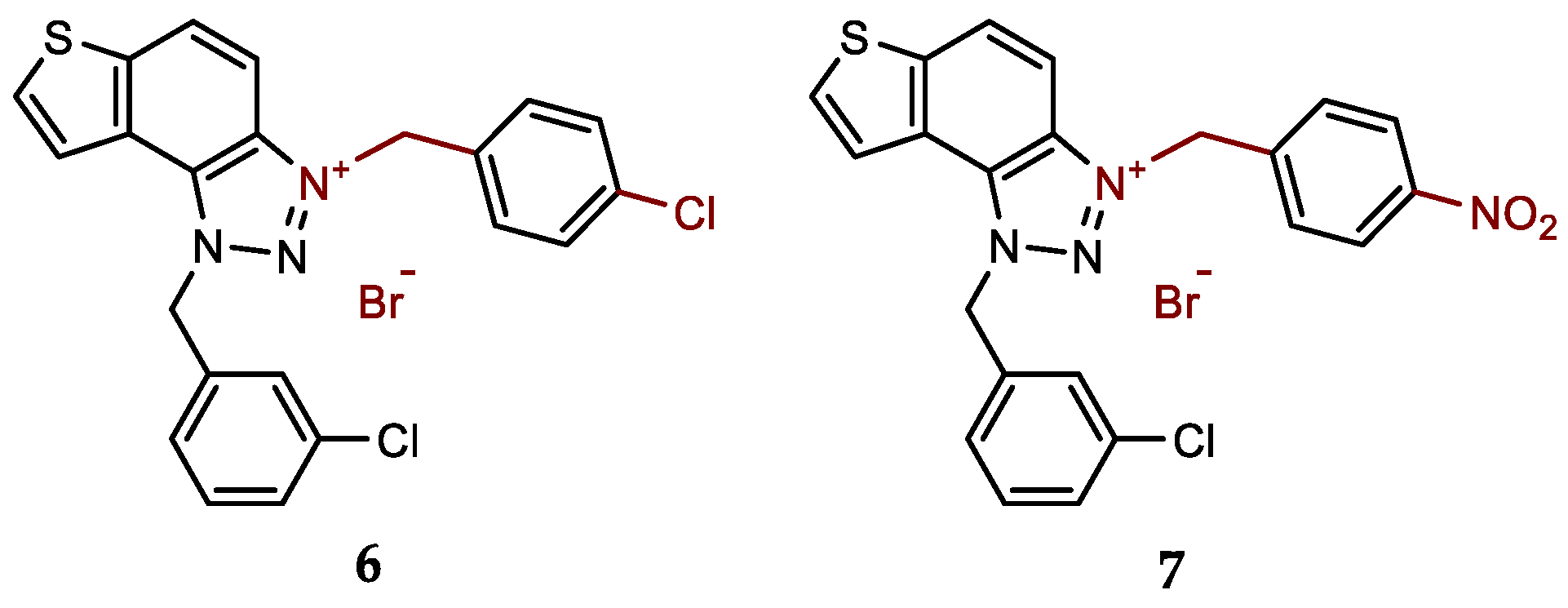

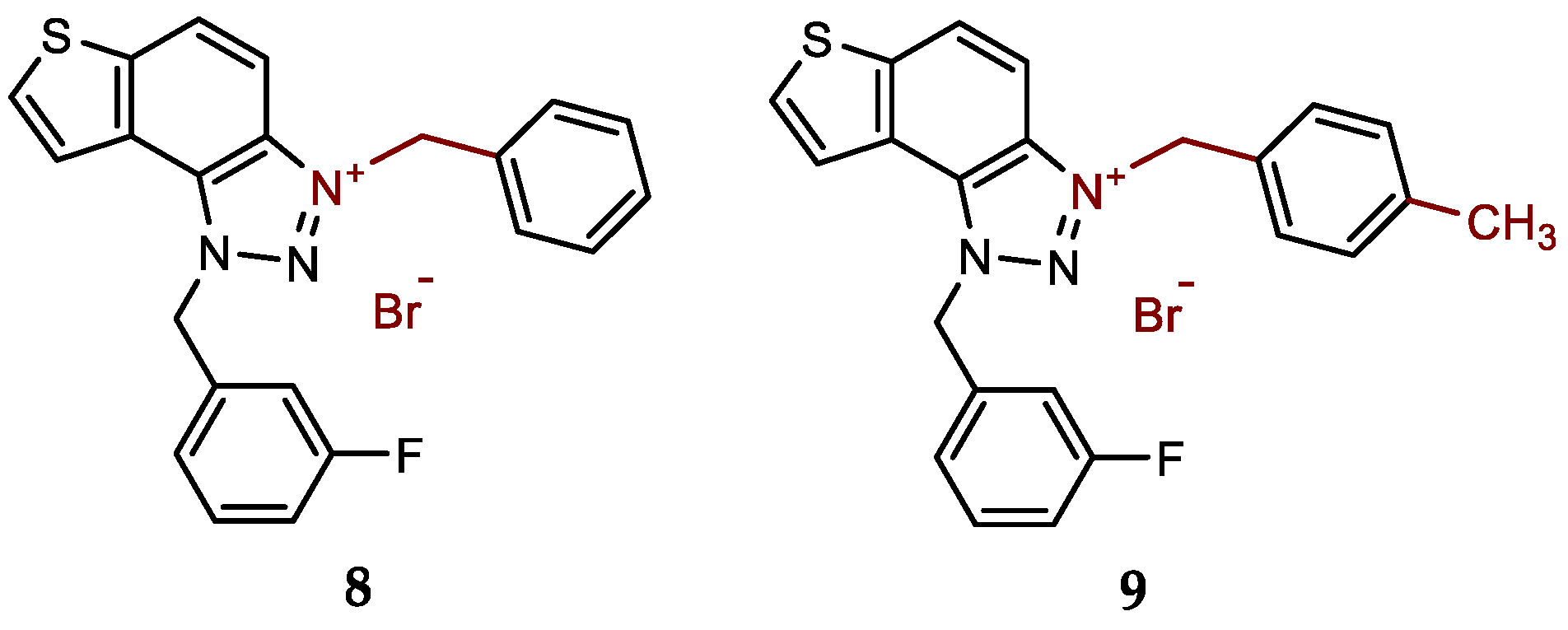

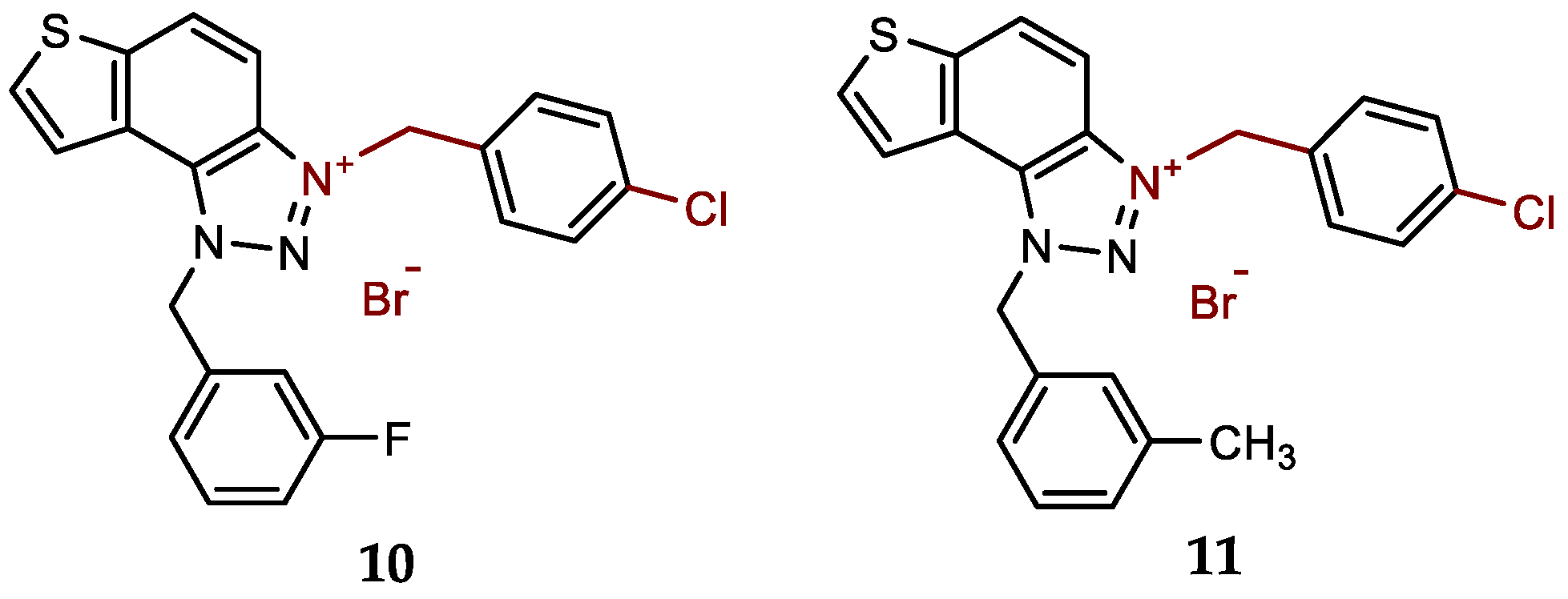

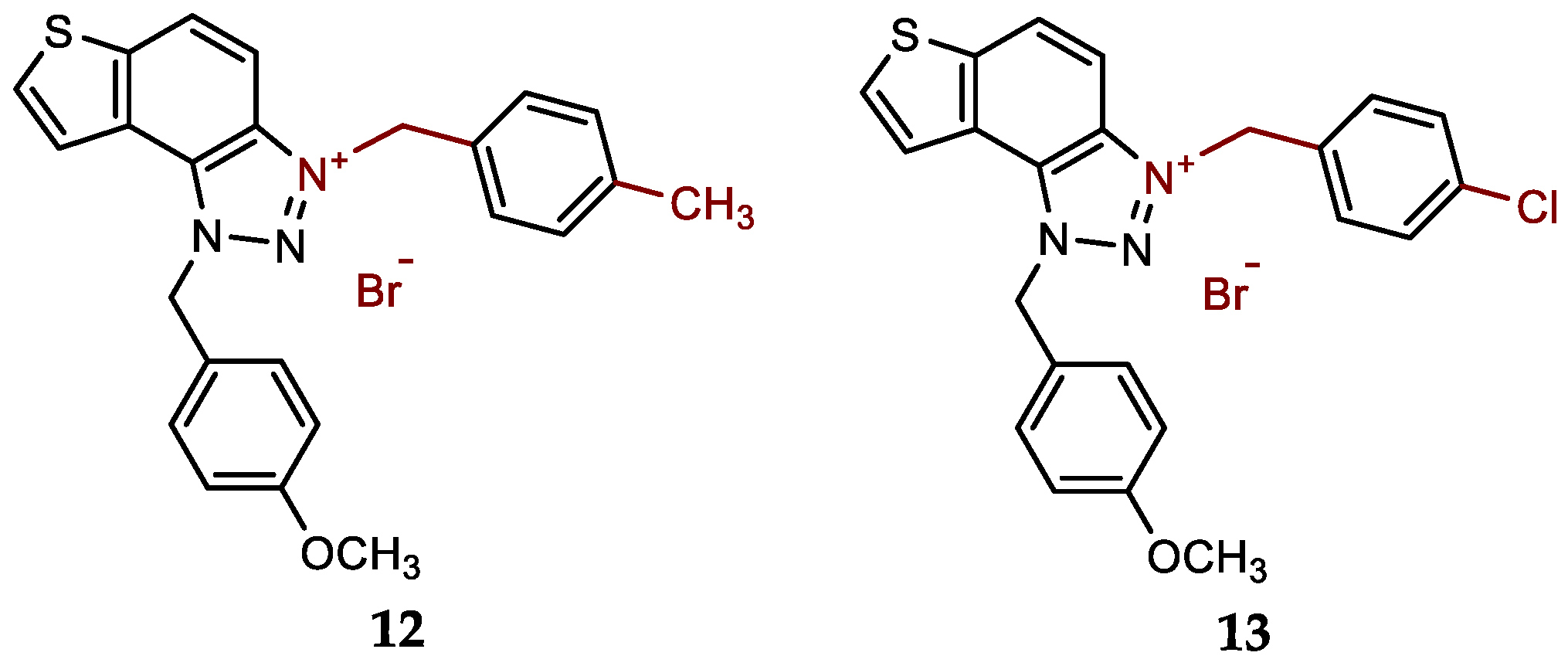

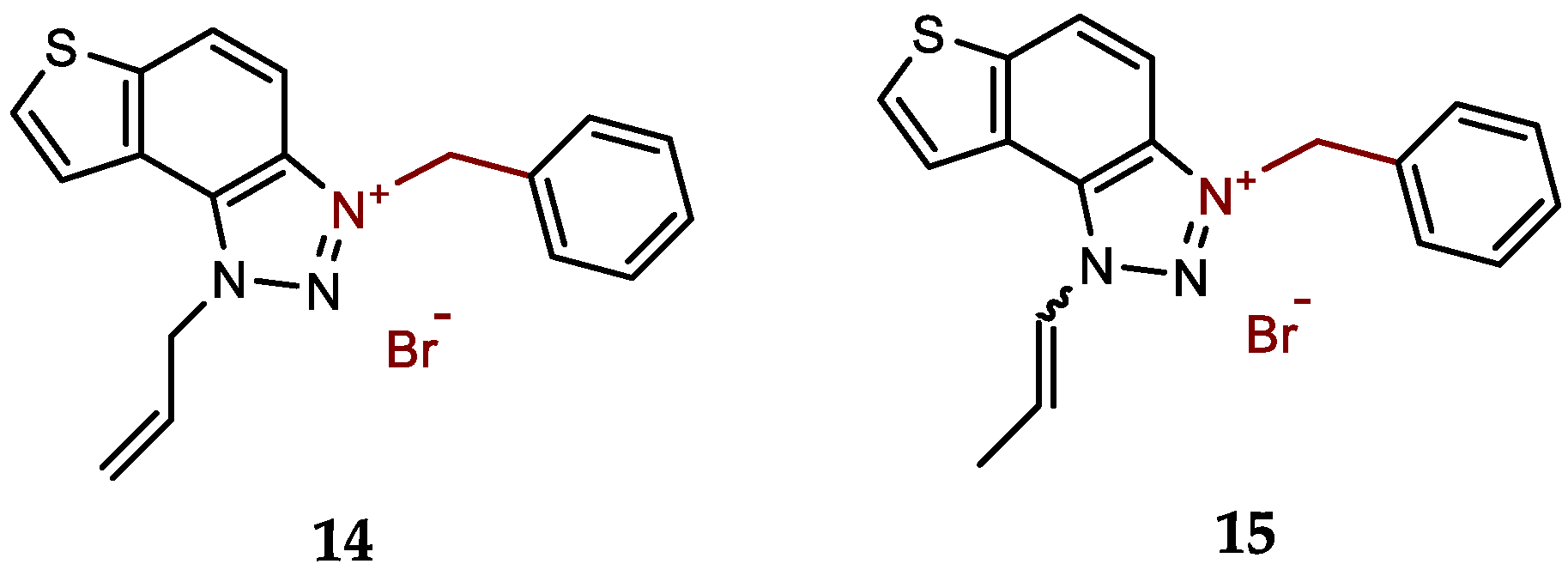

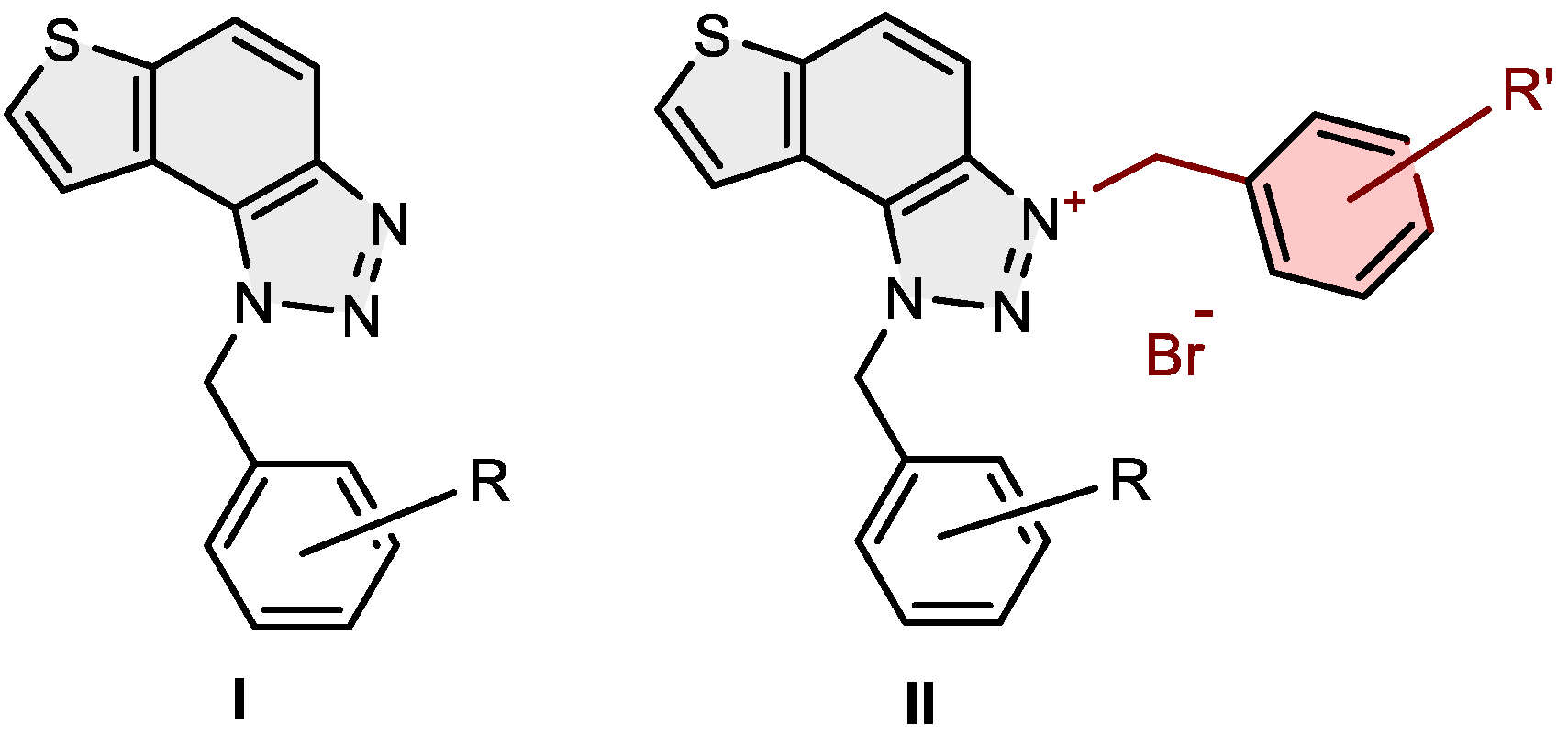

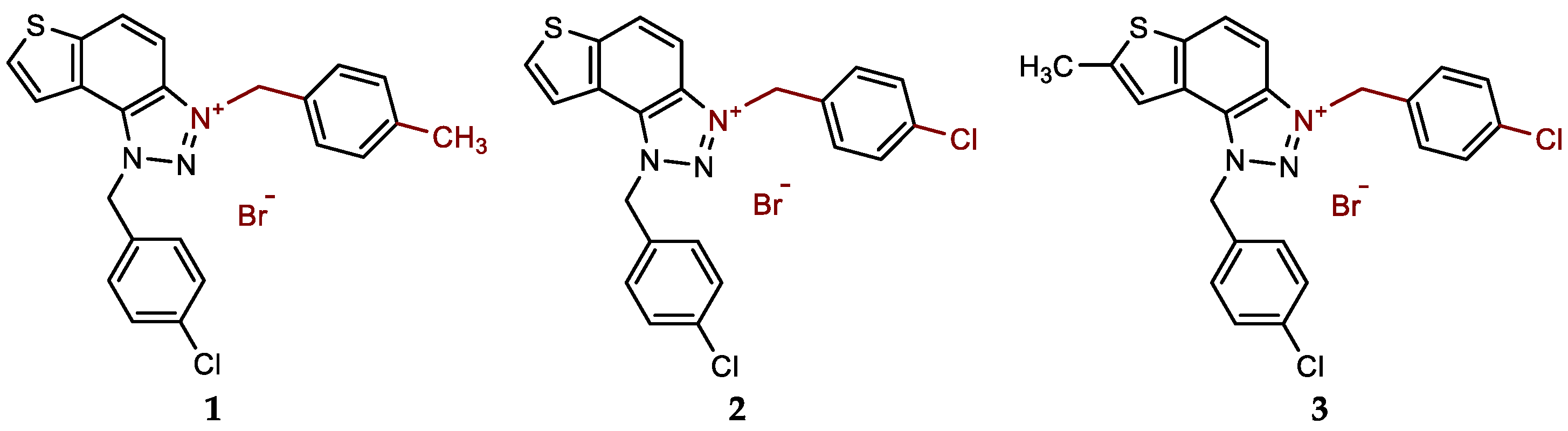

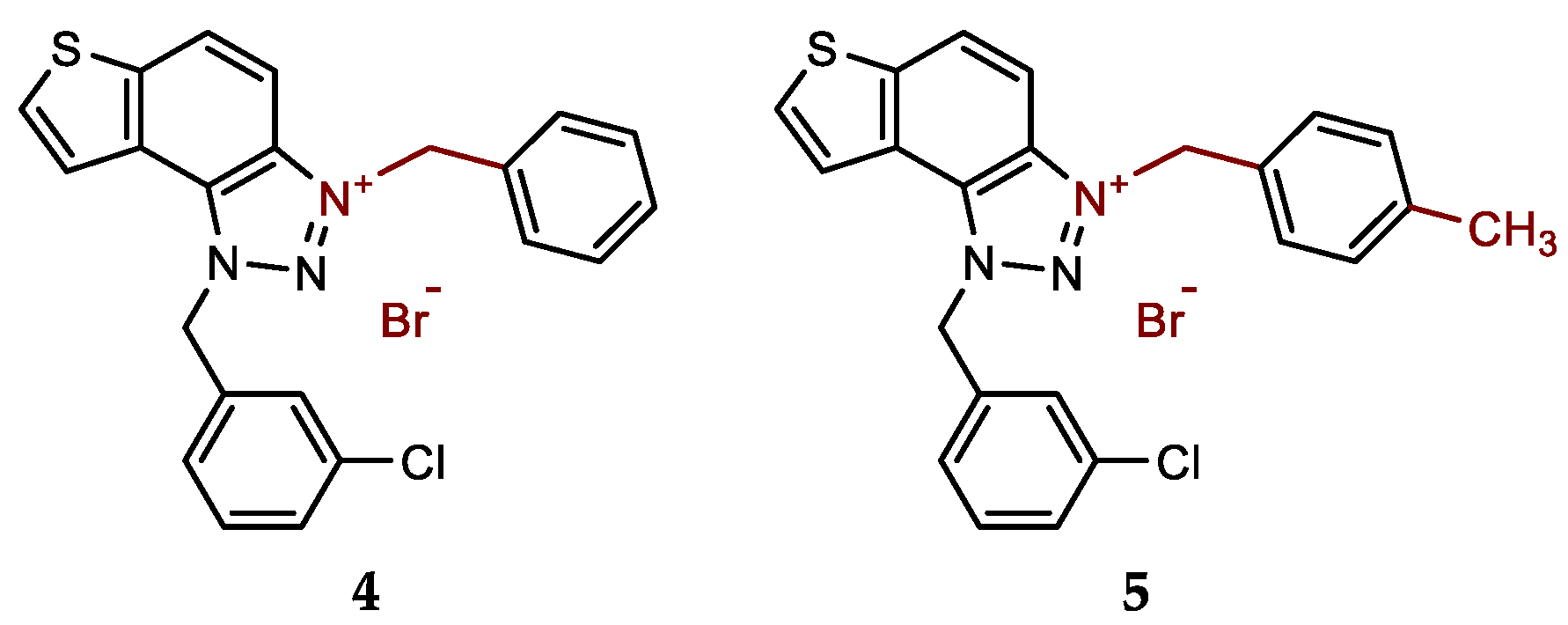

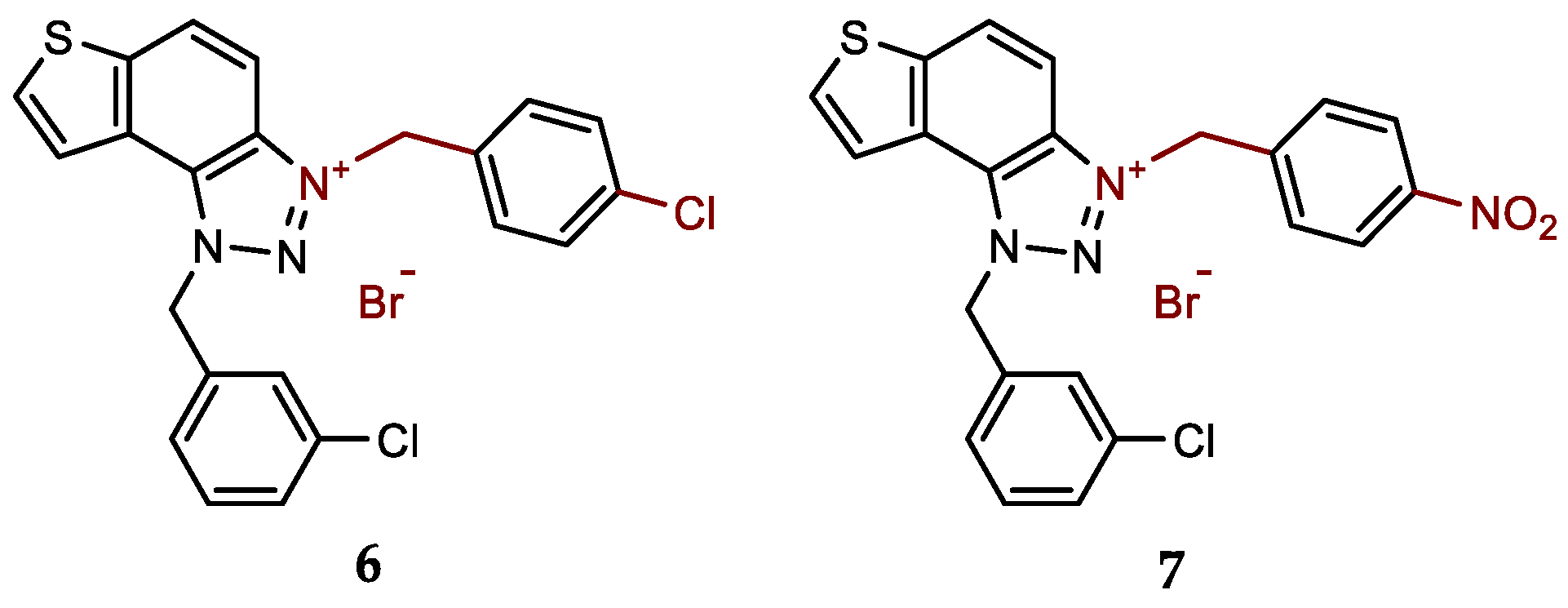

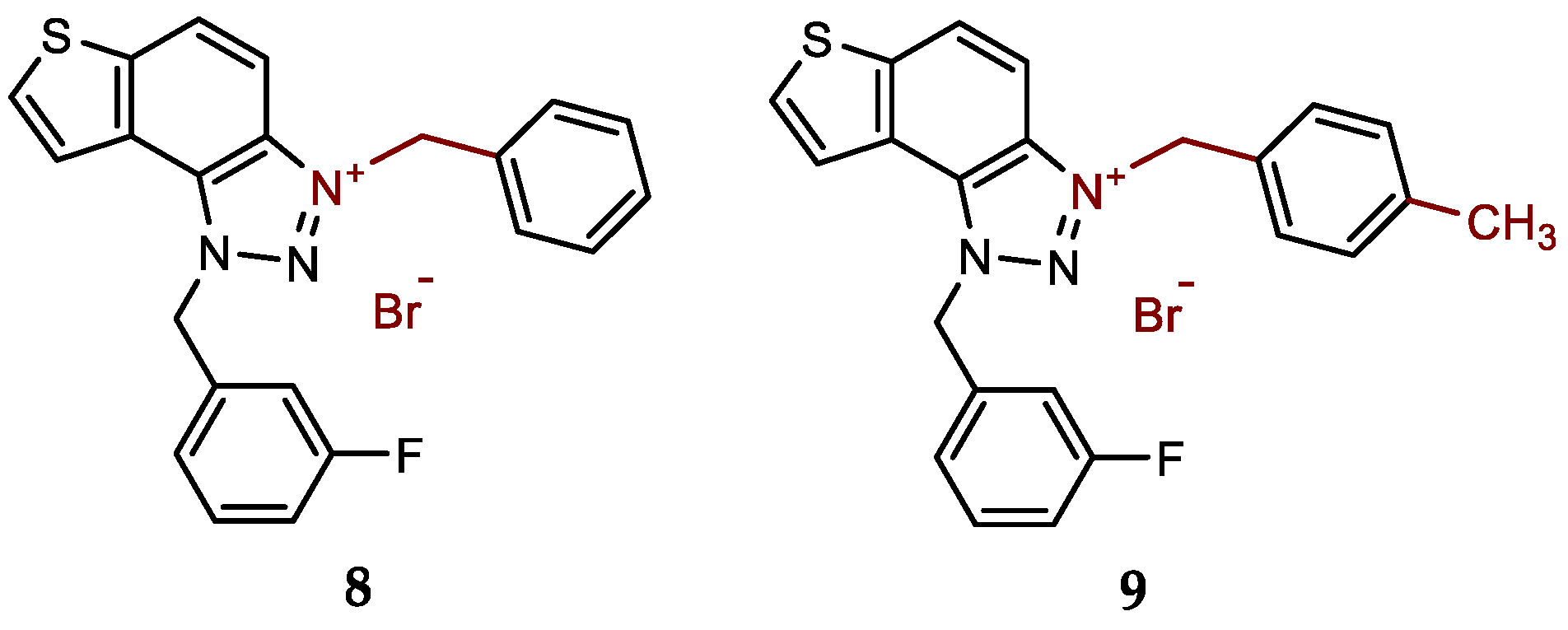

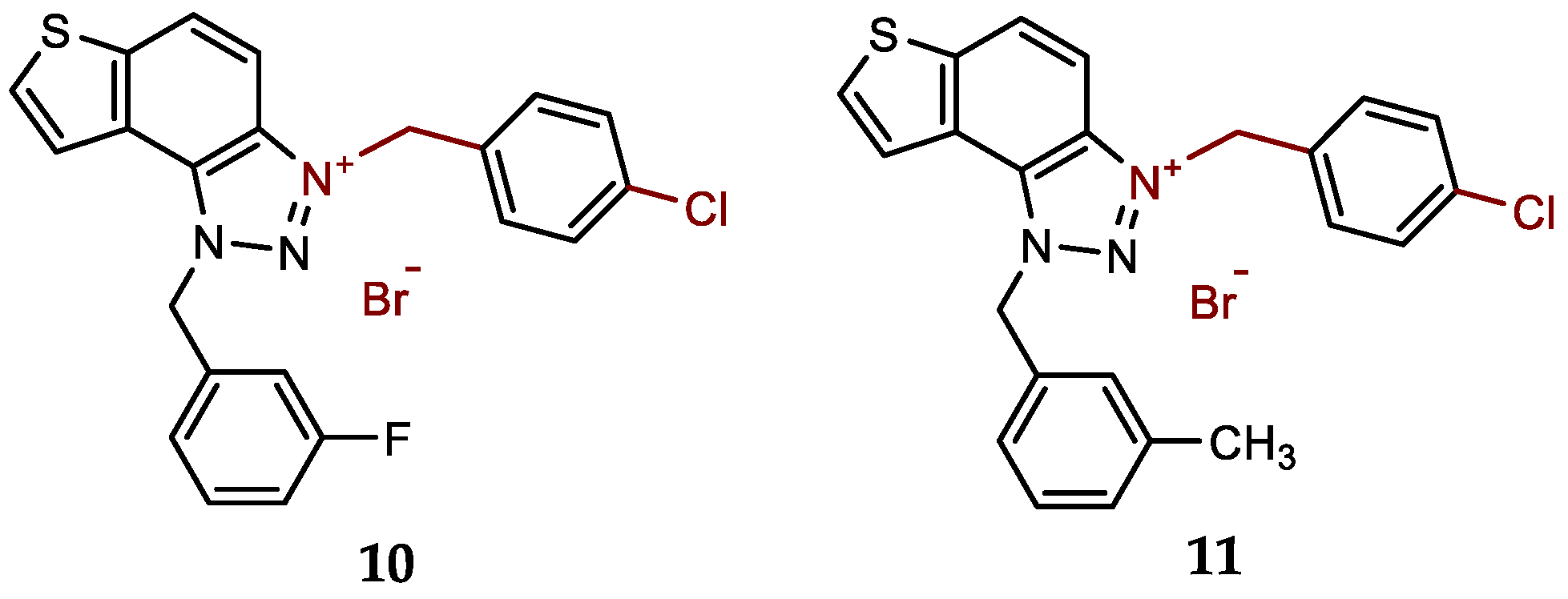

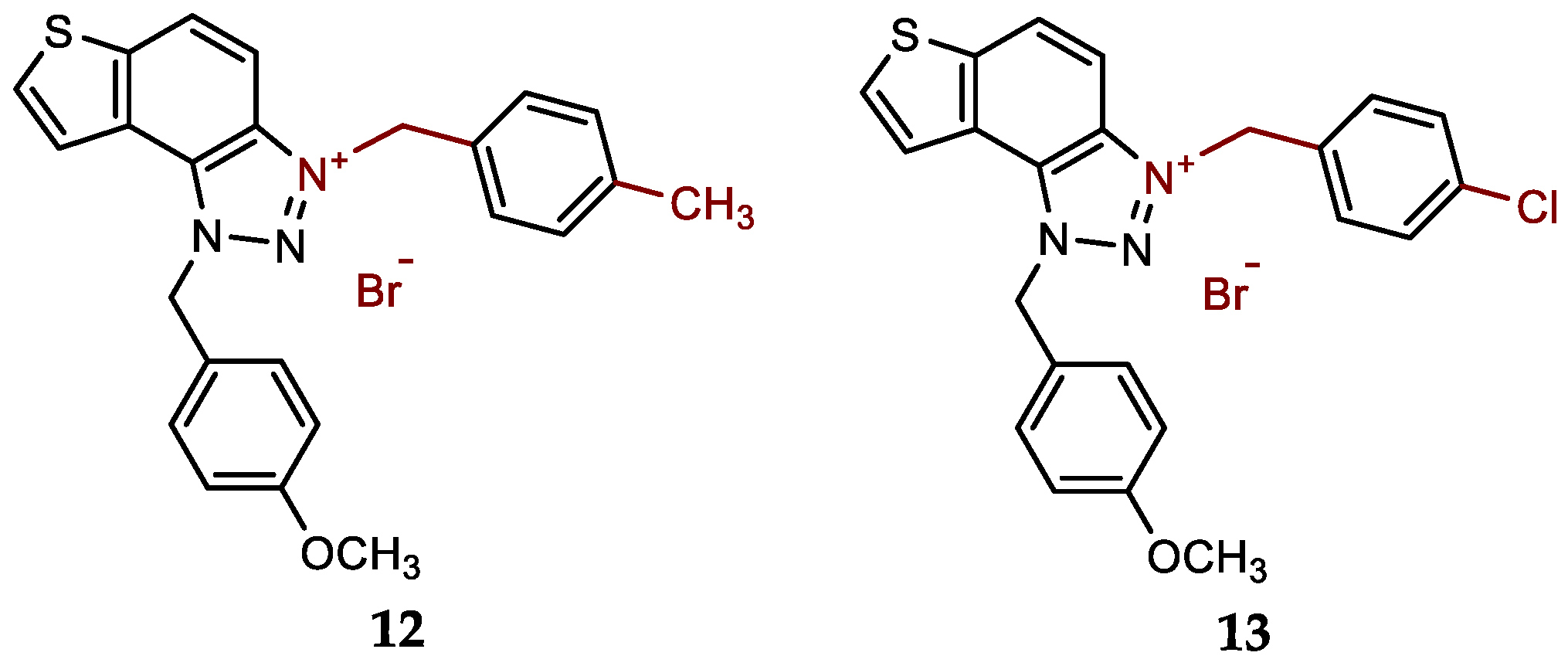

Figure 2, isolated yields 27–96%).

New charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole salts

1–

15 were fully spectroscopically characterized (See Materials and Methods and

Supplementary Materials). In the

1H NMR spectra of triazole salts

1–

15, a new signal of the second methylene group on the charged triazole nitrogen is visible between 6.1 and 6.4 ppm, undoubtedly confirming the formation of the target structures (

Figure 3).

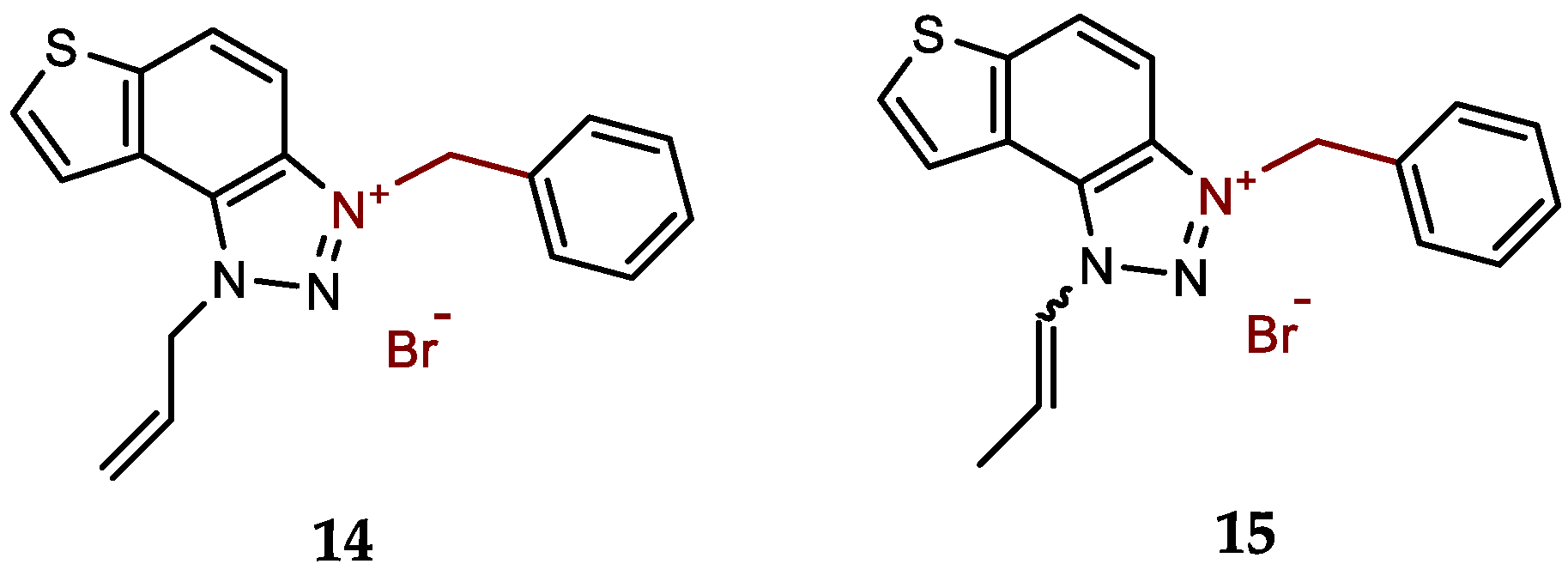

3.2. Cholinesterase Inhibition Activity of Triazole Salts 1-15

To evaluate the biological potency of newly synthesized thienobenzo-triazole salts 1‒15 as inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), a modified Ellman’s method [

24] was employed. The compounds were tested over a broad concentration range, depending on their solubility, and their inhibitory activities were compared to those of the commercially available drug donepezil. The IC

50 values and Selectivity index for triazolium salts

1‒

3 and

5‒

15 are presented in

Table 1 (the obtained amount of triazole salt

4 was not enough for cholinesterase inhibition activity testing). As expected, based on our previous findings [

19,

21], the tested triazole salts exhibited inhibition of both enzymes, AChE and BChE. Most of the tested compounds showed more potent inhibition of BChE. However, enzyme selectivity varies and depends on the specific molecular structure (

Table 1).

Among the tested compounds, derivative

14, featuring the allyl and benzyl substituents at the triazole ring, stands out as the most potent and selective inhibitor toward BChE. The presence of the allyl group favors inhibitory activity, as we previously found that among the non-charged thienobenzo-triazoles, the derivative with the allyl substituent was the most potent BChE inhibitor [

22,

23]. The introduction of a charge on the triazole ring via the benzyl substituent enhances the inhibition of both enzymes. The achieved IC

50 value for BChE falls in nanomolar range at 98.0 nM better than for the standard donepezil (IC

50 for BChE 4.25 μM), while achieved IC

50 value for inhibition of AChE is 2.13 μM, that is much weaker than for the standard donepezil (IC

50 for AChE 23.0 nM) (

Table 1). Derivative

15, with the propenyl substituent instead of the allyl, is also an excellent BChE inhibitor, with an IC

50 value in the nanomolar range at 732.0 nM. In contrast, the IC

50 for AChE is the same as for 14, at 3.62 μM.

The remaining tested compounds (

1‒

3 and

5‒

13) contain two monosubstituted benzyl groups (with ‒Cl, ‒F, ‒OCH

3, ‒NO

2, or ‒CH

3), attached to the triazole ring, while only derivative

3 possesses a methyl substituent on the thiophene ring. Among these derivatives, compound

9 with a methyl group at the

para-position of one benzyl ring and fluorine at the

meta-position of another benzyl ring exhibited the most potent dual inhibitory activity, with IC

50 values of 363.0 nM for BChE and 4.80 μM for AChE. The next most potent inhibitors were derivatives

6 and

11 (

Table 1), while the remaining ones fit a very good range of inhibitory activity toward BChE and good to moderate activity toward AChE. Overall, it is found that herein synthesized charged thienobenzo-triazoles were shown to be strong inhibitors of both enzymes, with activity and selectivity depending on the type of substitution, electron-withdrawing or -donating effect, and position of substituents on rings.

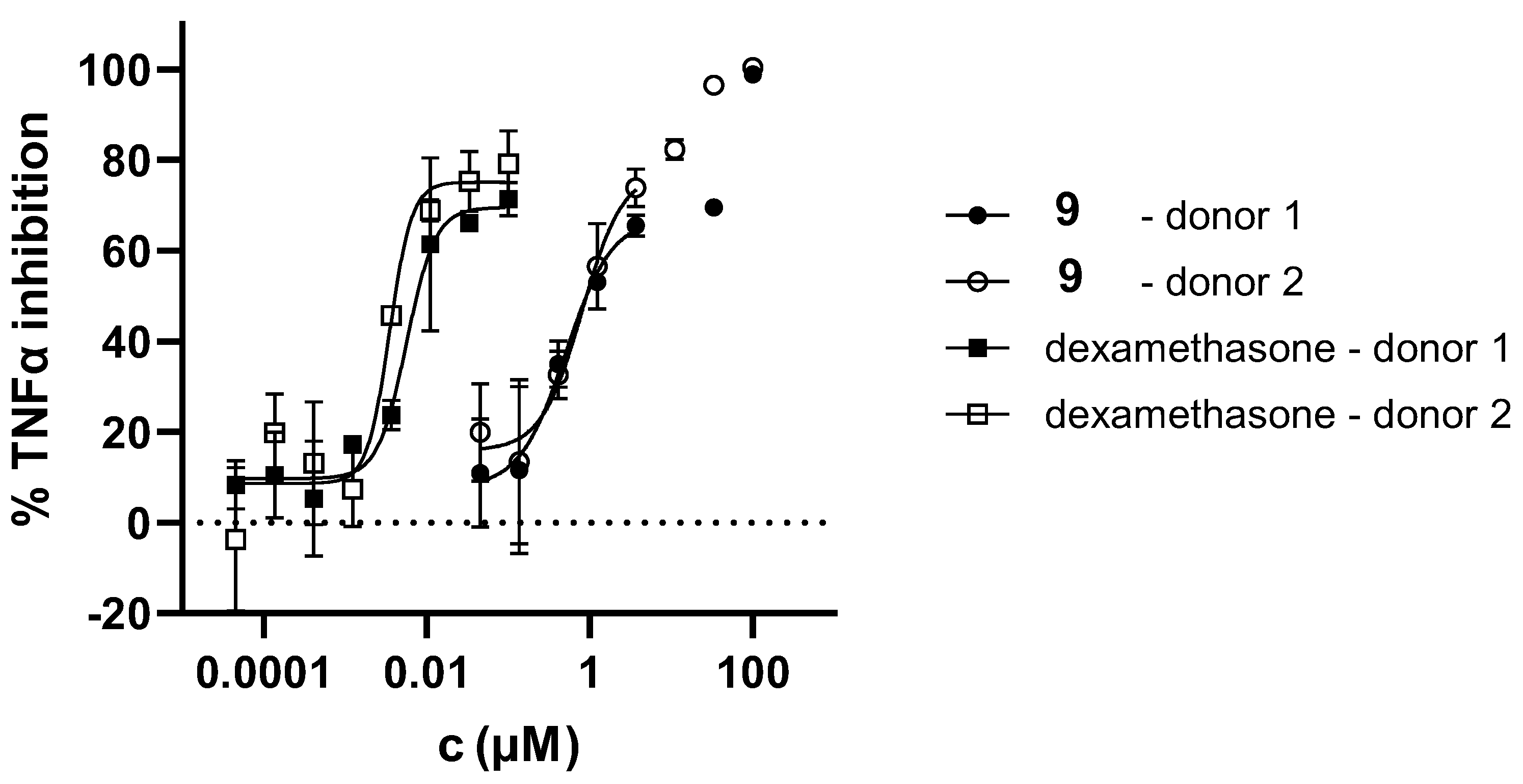

3.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Triazole Salts 1‒15

To evaluate the potential anti-inflammatory activity of the compounds, the effect of the compounds on LPS-stimulated TNF-α production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was tested. Triazole salt

9 inhibited LPS-stimulated TNF-α production with an IC

50 of 0.66 µM (

Figure 4). The compound affected cell viability at the three highest concentrations tested. However, at lower concentrations, inhibition of TNF-α production was achieved without reducing the number of cells. On the other hand, compounds

1,

2,

4,

5,

8,

10–13 reduced cell viability, but at concentrations that did not reduce cell number, compounds did not inhibit TNF-α production (data not shown). Compounds

3,

6, and

7 did not inhibit TNF-α production at any of the tested concentrations. In line with previously obtained results, the control compound, dexamethasone, inhibited LPS-stimulated TNF-α production with an IC

50 value of 4.6 nM (

Figure 4). It is important to be mentioned, that among derivatives

1‒

3 and

5‒

13 which contain two monosubstituted benzyl groups attached to the triazole ring, again compound

9 exhibited the most potent dual inhibitory activity, with IC

50 values of 363.0 nM for BChE and 4.80 μM for AChE (

Table 1).

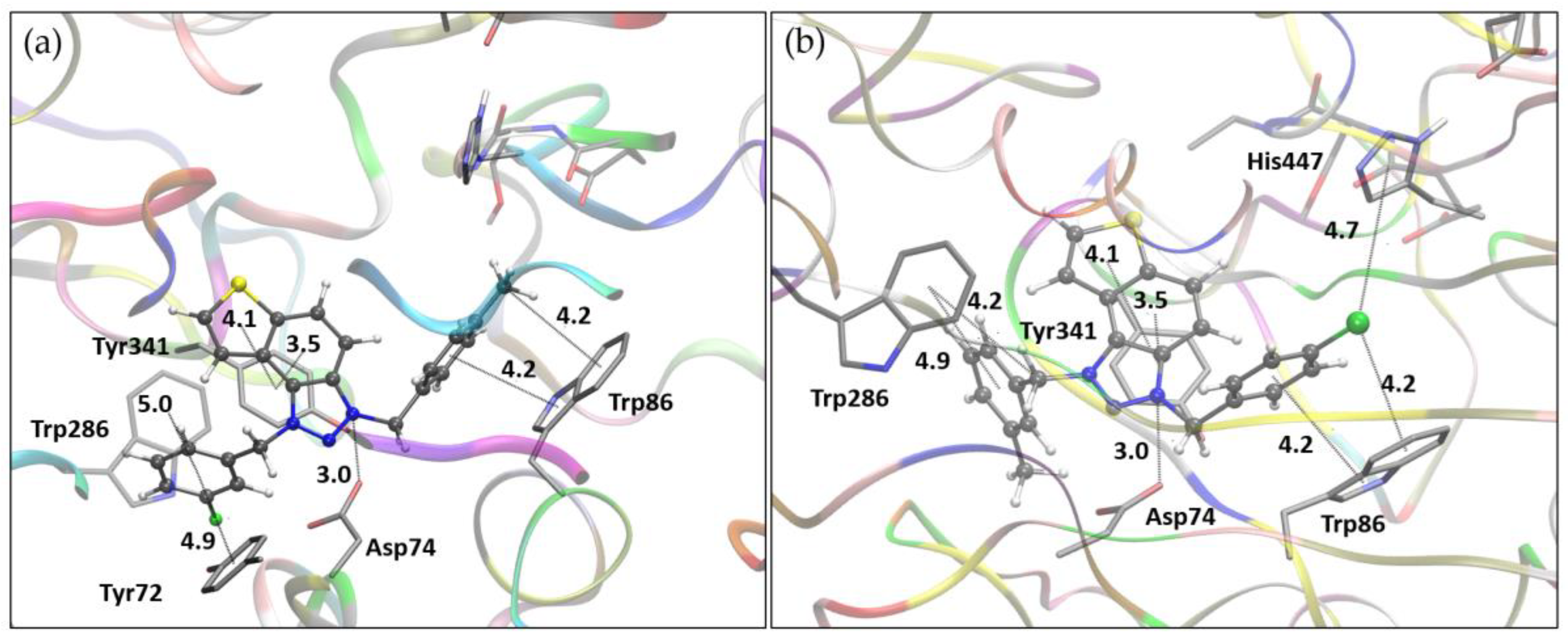

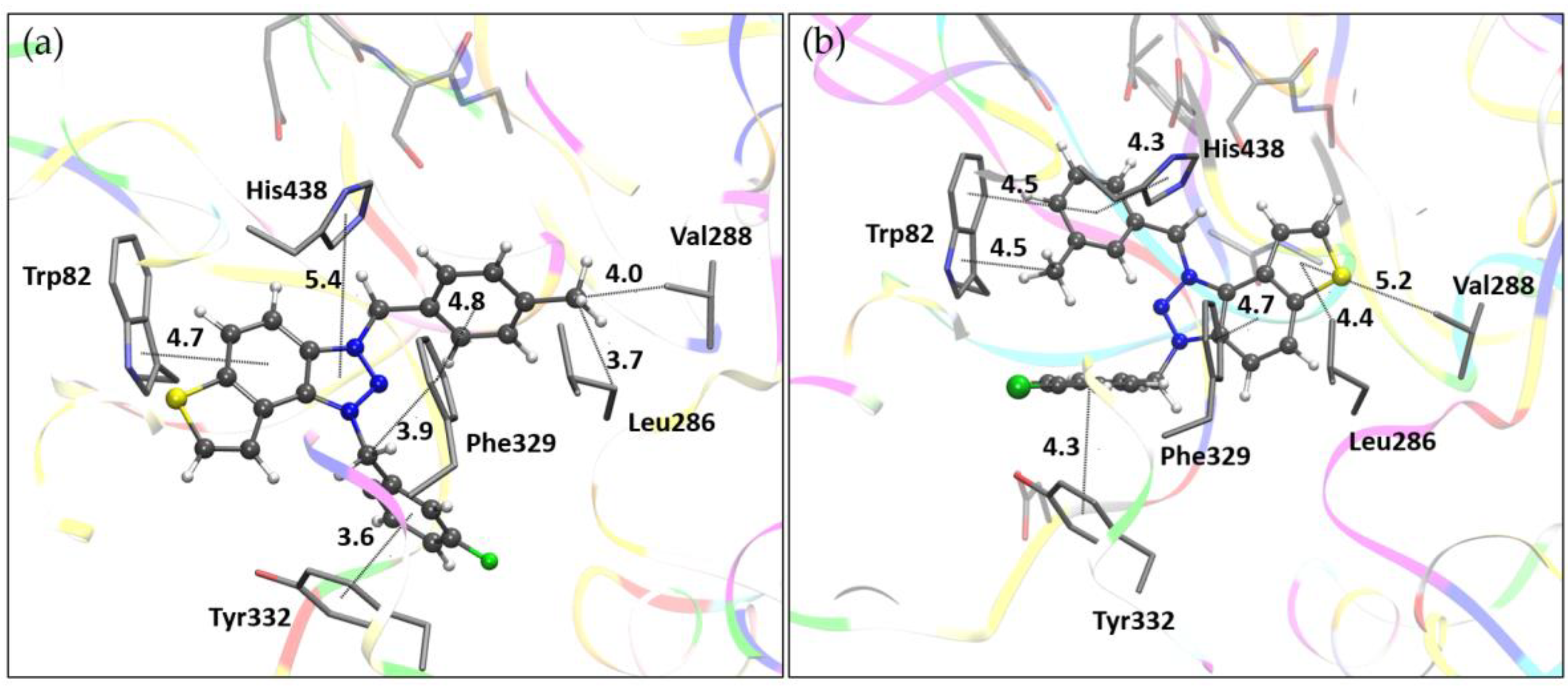

3.4. Molecular Docking of Bioactive Triazole Salts 9 and 11

The inhibitory activity results presented in

Table 1 show that, among the tested compounds (

1‒

3 and

5‒

13) that contain two monosubstituted benzyl groups, salts

9 and

11 demonstrate notable activity against both cholinesterases. Although not the most potent inhibitors identified, they were selected for molecular docking due to their synthetic accessibility and suitability for further analysis. Docking was performed to elucidate the structures of the non-covalent complexes they form with cholinesterases.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the complexes of salts

9 and

11 with AChE reveal that both ligands adopt a similar orientation within the enzyme's active site. The triazolium ring is positioned toward residue Asp74 in the peripheral anionic site (PAS) due to electrostatic attraction, while the thienobenzo fragment engages in π-π stacking with Tyr341.

In the case of salt 9, this orientation allows the meta-fluorobenzyl group attached to the triazole ring to engage in π-π interactions with Trp286 and Tyr72, both of which are located within the PAS. Simultaneously, the para-methylbenzyl substituent on the opposite side of the triazole ring forms π-π stacking and alkyl-π interactions with Trp86, a residue belonging to the anionic subsite of the active site. For salt 11, which contains a para-chlorinated benzyl on the triazole ring, π-π stacking with Trp86 is similarly noted. Additionally, the chlorine at the para position interacts to stabilize dispersion with Trp86 and His447, with interatomic distances of approximately 4.2 Å to the centroid of the phenyl ring of tryptophan and 4.7 Å to the centroid of the imidazole ring of histidine.

The binding modes of salts

9 and

11 with BChE are illustrated in

Figure 6. Unlike their orientation in AChE, the ligands take on distinct conformations within the BChE active site. For salt

9, the thienobenzo core engages in π-π stacking with Trp82, situated in the anionic site, while the triazole ring is oriented toward His438 in the catalytic site. The para-methylbenzyl substituent interacts with Phe329, with the methyl group directed toward the acyl pocket, comprised of residues Leu286 and Val288. The second substituent, a meta-fluorobenzyl group linked by a flexible –CH₂– spacer, participates in parallel π-π stacking with Tyr332. In the case of salt

11, the thienobenzo fragment is positioned near the acyl pocket and also interacts with Phe329. This orientation enables the

para-chlorobenzyl group attached to the triazolium ring to form π-π stacking interactions with Tyr332, while the second substituent, a

meta-methylbenzyl group, engages in π-π interactions with Trp82.

3.5. Genotoxicity of Triazole Salts 1‒15

Two complementary (Q)SAR models are used that make predictions of biological activity based on structural components [

31]. In-silico results are important during the early stages of drug development. The commonly used software is the Lhasa M7 package because it uses complementary models, and predictions are reviewed one more time by an expert. All compounds planned for synthesis were tested for in-silico mutagenicity during the synthesis phase (

Table 2). The results have shown that compounds

5,

7,

12, and

13 are all positive for mutagenicity potential. As these results are in silico, all compounds were synthesized, although they have not yet been tested for biological activity. Compounds

9 and

11 have shown great potential for biological activity (see above), and as they are negative, they can be pursued further as lead molecules.

Both compounds demonstrate limited central nervous system (CNS) permeability (

Table 3), as indicated by their negative log PS values (−0.910 for compound

9 and −0.888 for compound

11), which suggests a poorer ability to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) to reach CNS tissues. However, their log BB values (0.883 and 0.81, respectively) are relatively high, implying some extent of BBB penetration. This apparent discrepancy may reflect differences in the modeling approaches or compound interactions at the BBB. Despite being P-glycoprotein substrates, which potentially limits their CNS exposure via efflux mechanisms, the moderate log BB values suggest that both compounds may still achieve moderate CNS access. Overall, both compounds exhibit non-CNS penetration potential, with compound 9 showing a slightly higher theoretical ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that the newly synthesized charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole derivatives possess strong inhibitory activity against both acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), with a clear tendency toward higher potency and selectivity for BChE. This makes them promising candidates for the treatment of disorders where peripheral cholinesterase inhibition is desired, such as myasthenia gravis or post-surgical reversal of neuromuscular blockade. The introduction of a permanent positive charge on the triazole ring proved to be a critical structural modification, significantly enhancing enzyme binding affinity, especially for BChE. Among all tested compounds, derivative 14 stood out with sub-micromolar inhibition of both enzymes and excellent selectivity. At the same time, compound 9 demonstrated not only potent dual inhibition but also substantial anti-inflammatory activity in a TNF-α suppression assay.

These dual-functional properties suggest that certain charged triazole derivatives could serve as multifunctional drug candidates, combining cholinesterase inhibition with immunomodulatory effects, which is particularly relevant in the context of neurodegenerative diseases that feature both cholinergic deficits and chronic inflammation, such as Alzheimer's disease. Furthermore, molecular docking studies provided structural insights into ligand-enzyme interactions, supporting the observed biological data and confirming stable and specific binding to key residues in the active sites of AChE and BChE. In addition to biological evaluation, in silico ADME-Tox profiling for selected lead compounds revealed favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles, including acceptable solubility, moderate permeability, non-mutagenicity, and predictable metabolic behavior. These properties, combined with synthetic accessibility and chemical stability, enhance the potential of these molecules for further development in preclinical studies. In conclusion, this work establishes a valuable platform for the design of novel, charged heterocyclic compounds with dual therapeutic actions. The promising in vitro and in silico profiles of derivatives 9 and 14, in particular, underscore the importance of structural charge modulation in optimizing cholinesterase inhibitors with peripheral selectivity and added therapeutic benefits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of new charged triazole salts 1–15 (Figures S1-S30); Mass spectra and HRMS analyses of new charged triazole salts 1–15 (Figures S31-S43); Cartesian coordinates of ligands 9 and 11 docked into the active site of AChE; Cartesian coordinates of ligands 9 and 11 docked into the active site of BChE; Free energies of binding, the number of conformational clusters, and distribution of conformations obtained by molecular docking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.O. and I.S.; methodology, A.J., A.Rat., A.Ras., D.B., M.B. and I.Š.; formal analysis, Z.L. and S.R.; investigation, P.P., D.S., A.Ras. and A.J.; resources, M.B., I.O., D.B., I.Š. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J., M.B., I.O., D.B., I.Š. and I.S.; writing—review and editing, D.B. and I.S; supervision, I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the University of Zagreb for short-term scientific support for 2024 under the title Synthesis and Biological Activity of New Heteropolycycle Systems. We thank the University of Zagreb (Croatia) Computing Centre (SRCE) for granting computational time on the Supercomputer Supek.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Masson, P.; Lockridge, O. Butyrylcholinesterase for protection from organophosphorus poisons: Catalytic complexities and therapeutic promises. British Journal of Pharmacology 2010, 2010 160, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colović, M.B.; Krstić, D.Z.; Lazarević-Pašti, T.D.; Bondžić, A.M.; Vasić, V.M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Pharmacology and toxicology. Current Neuropharmacology 2013, 11, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Singh, B. A review on cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2013, 36, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talesa, V.N. Acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Drug Targets 2001, 2, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greig, N.H.; Utsuki, T.; Yu, Q.S.; Holloway, H.W. A new therapeutic target in Alzheimer's disease treatment: Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 12, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam, M.M.; Guillozet, A.; Shaw, P.; Levey, A. Acetylcholinesterase knockouts establish centrality of cholinergic networks. Annals of Neurology 2002, 52, 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, R.M.; Potkin, S.G.; Enz, A. Galantamine: A novel cholinergic modulator. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2017, 16, 1487–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, A.A.; Kadam, P.; Sharma, H. Clinical application of neostigmine and its peripheral selectivity. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia 2022, 66, 738–745. [Google Scholar]

- Silman, I.; Sussman, J.L. Acetylcholinesterase: 'Classical' and 'non-classical' functions and pharmacology. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2005, 5, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Anticholinesterase agents. In Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 12th ed.; Katzung B.G., Ed.; McGraw-Hill, New York, USA, 2011; pp. 123–134.

- Younus, M. , & Raza, S. (2023). Blood-brain barrier permeability of cholinergic drugs: Prodrug strategies. Drug Development Research, 84. [CrossRef]

- Bajgar, J.; Kuca, K.; Fusek, J.; Jun, D. Pharmacology and toxicology of cholinesterase reactivators: Influence of molecular charge. Neurotoxicity Research 2020, 38, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, M.; Nguyen, L.; Bergeron, R. Cholinesterase inhibitors: Clinical applications and molecular mechanisms. Journal of Neurochemistry 2021, 158, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, Z.; Song, L. Peripheral-targeted cholinesterase inhibitors: A safer path. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 678233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L. Advances in peripheral-selective cholinesterase inhibitors: From chemistry to clinical implications. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 29, 2050–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kaur, R.; Virdi, R. Strategies to optimize CNS delivery of cholinesterase inhibitors. Pharmaceutical Research 2022, 39, 1975–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, B.L.; Driscol, J.; Glennon, R.A. Drugs with anticholinergic properties: Functional roles and side effects. Pharmacological Reviews 2002, 54, 364–385. [Google Scholar]

- Krátký, M.; Vinšová, J.; Buchta, V.; Stolaříková, J. Quaternary ammonium-based cholinesterase inhibitors: Synthesis and biological evaluation. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2016, 26, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Mlakić, M.; Sviben, M.; Ratković, A.; Raspudić, A.; Barić, D.; Šagud, I.; Lasić, Z.; Odak, I.; Škorić, I. Efficient Access to New Thienobenzo-1,2,3-Triazolium Salts as Preferred Dual Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratković, A.; Mlakić, M.; Dehaen, W.; Opsomer, T.; Barić, D.; Škorić, I. Synthesis and photochemistry of novel 1,2,3-triazole di-heterostilbenes. An experimental and computational study. Spectrochimica acta. Part A, Molecular and biomolecular spectroscopy 2021, 261, 120056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakić, M.; Barić, D.; Ratković, A.; Šagud, I.; Čipor, I.; Piantanida, I.; Odak, I.; Škorić, I. New Charged Cholinesterase Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis, and Characterization. Molecules 2024, 29, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakić, M.; Odak, I.; Faraho, I.; Talić, S.; Bosnar, M.; Lasić, K.; Barić, D.; Škorić, I. New naphtho/thienobenzo-triazoles with interconnected anti-inflammatory and cholinesterase inhibitory activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 241, 114616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakić, M.; Selec, I.; Ćaleta, I.; Odak, I.; Barić, D.; Ratković, A.; Molčanov, K.; Škorić, I. New Thienobenzo/Naphtho-Triazoles as Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis and Computational Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtnex, K.D.; Andres, V.; Featherstone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcho-linesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlakić, M.; Faraho, I.; Odak, I.; Kovačević, B.; Raspudić, A.; Šagud, I.; Bosnar, M.; Škorić, I.; Barić, D. Cholinesterase Inhibitory and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Naphtho- and Thienobenzo-Triazole Photoproducts: Experimental and Computational Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDock-Tools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.; Rudolph, M.; Burshteyn, F.; Cassidy, M.; Gary, E.; Love, J.; Height, J.; Franklin, M. Crystal Structure of Recombinant Human Acetylcholinesterase in Complex with Donepezil. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10282–10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolet, Y.; Lockridge, O.; Masson, P.; Fontecilla-Camps, J.C.; Nachon, F. Crystal Structure of Human Butyrylcholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 41141–41147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lou, Ch.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Zh.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. AdmetSAR 2.0: web-service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselgren, C.; Bercu, J.; Cayley, A.; Cross, K.; Glowienke, S.; Kruhlak, N.; Muster, W.; Nicolette, J.; Vijayaraj Reddy, M.; Saiakhov, R.; Dobo, K. Management of Pharmaceutical ICH M7 (Q)SAR Predictions – The Impact of Model Updates. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 118, 104807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Structures of uncharged thienobenzo-triazoles

I with preferred inhibition of BChE and their charged triazole salts

II as dual cholinesterase inhibitors [

19].

Figure 1.

Structures of uncharged thienobenzo-triazoles

I with preferred inhibition of BChE and their charged triazole salts

II as dual cholinesterase inhibitors [

19].

Scheme 1.

Synthetic steps to charged triazole benzyl salts 1–15.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic steps to charged triazole benzyl salts 1–15.

Figure 2.

Structures of new charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole salts 1–15 and their isolated yields in brackets).

Figure 2.

Structures of new charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole salts 1–15 and their isolated yields in brackets).

Figure 3.

Parts of the 1H NMR spectra of charged triazole salts a) 9, b) 11, and c) 1.

Figure 3.

Parts of the 1H NMR spectra of charged triazole salts a) 9, b) 11, and c) 1.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNFα production in PBMCs from 2 donors for charged triazole bromide salt 9.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNFα production in PBMCs from 2 donors for charged triazole bromide salt 9.

Figure 5.

(a) The structure of triazole salt 9 docked into the active site of AChE. (b) Structure of triazole salt 11 docked into the active site of AChE. Ligands are presented using a ball-and-stick model, distances given in angstroms.

Figure 5.

(a) The structure of triazole salt 9 docked into the active site of AChE. (b) Structure of triazole salt 11 docked into the active site of AChE. Ligands are presented using a ball-and-stick model, distances given in angstroms.

Figure 6.

(a) The structure of triazole salt 9 docked into the active site of BChE. (b) Structure of triazole salt 11 docked into the active site of BChE. Ligands are presented using a ball-and-stick model, distances given in angstroms.

Figure 6.

(a) The structure of triazole salt 9 docked into the active site of BChE. (b) Structure of triazole salt 11 docked into the active site of BChE. Ligands are presented using a ball-and-stick model, distances given in angstroms.

Table 1.

Calculated IC50 values for the inhibition of AChE and BChE by the charged triazole salts 1‒3 and 5‒15.

Table 1.

Calculated IC50 values for the inhibition of AChE and BChE by the charged triazole salts 1‒3 and 5‒15.

| Compound |

AChE

IC50 / μM |

BChE

IC50 / μM |

Selectivity index |

| 1 |

12.74 ± 1.85 |

2.55 ± 0.58 |

5.0 |

| 2 |

10.71 ± 1.46 |

4.99 ± 1.10 |

2.1 |

| 3 |

8.89 ± 3.26 |

7.60 ± 0.82 |

1.2 |

| 5 |

55.62 ± 2.36 |

8.13 ± 0.83 |

6.8 |

| 6 |

12.90 ± 0.87 |

0.96 ± 0.14 |

13.4 |

| 7 |

11.42 ± 0.39 |

10.03 ± 1.64 |

1.1 |

| 8 |

22.23 ± 2.83 |

4.52 ± 0.17 |

4.9 |

| 9 |

4.80 ± 0.71 |

0.363 ± 0.038 |

13.2 |

| 10 |

9.96 ± 0.42 |

2.45 ± 0.43 |

4.1 |

| 11 |

6.23 ± 0.58 |

1.11 ± 0.77 |

5.6 |

| 12 |

11.81 ± 2.15 |

3.98 ± 1.25 |

3.0 |

| 13 |

7.40 ± 0.94 |

4.05 ± 1.05 |

1.8 |

| 14 |

2.13 ± 0.13 |

0.098 ± 0.018 |

21.7 |

| 15 |

3.62 ± 0.42 |

0.732 ± 0.137 |

4.9 |

| Donepezil |

0.023 ±0.004 |

4.25 ±0.09 |

0.005 |

Table 2.

The mutagenic potential of new charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole salts 1–15 through Lhasa M7 evaluation (green square—negative, red square—positive, white square—no data available); grey highlight—negative, orange highlight—positive, white—strongly negative.

Table 3.

In silico analysis of additional ADME(T) indicators—absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity—in the human body for new charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole salts 9 and 11.

Table 3.

In silico analysis of additional ADME(T) indicators—absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity—in the human body for new charged thienobenzo-1,2,3-triazole salts 9 and 11.

| Property |

Model Name |

9 |

11 |

Unit |

| Absorption |

Water solubility |

-5.103 |

-5.31 |

log mol/L |

| Caco2 |

0.814 |

0.812 |

log Papp in 10−6 cm/s |

| Intestinal absorption |

100 |

100 |

% Absorbed |

| Skin permeability |

-2.732 |

-2.732 |

log Kp |

| P−glycoprotein substrate |

Yes |

Yes |

|

| P−glycoprotein I inhibitor |

No |

No |

|

| P−glycoprotein II inhibitor |

Yes |

Yes |

|

| Distribution |

VDss (human) |

-0.333 |

-0.186 |

log L/kg |

| Fraction unbound |

0.299 |

0.289 |

Fu |

| BBB permeability |

0.883 |

0.81 |

log BB |

| CNS permeability |

-0.91 |

-0.888 |

log PS |

| Metabolism |

CYP2D6 substrate |

No |

No |

|

| CYP3A4 substrate |

Yes |

Yes |

|

| CYP1A2 inhibitor |

Yes |

Yes |

|

| CYP2C19 inhibitor |

Yes |

No |

|

| CYP2C9 inhibitor |

No |

No |

|

| CYP2D6 inhibitor |

Yes |

Yes |

|

| CYP3A4 inhibitor |

No |

No |

|

| Excretion |

Total clearance |

0.215 |

1.231 |

log ml/min/kg |

| Renal OCT2 substrate |

No |

No |

Yes/No |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).