1. Introduction

The 26S proteasome is a large, ATP-dependent proteolytic machine complex responsible for degrading ubiquitinated proteins in eukaryotic cells. It plays a critical role in maintaining cellular protein homeostasis by selectively removing misfolded, damaged, or regulatory proteins tagged with ubiquitin [

1]. The 26S proteasome consists of a 20S catalytic core particle and one or two 19S regulatory particles that recognize and unfold ubiquitinated substrates [

2,

3]. This tightly regulated degradation process is essential for numerous cellular functions, including protein homeostasis, DNA synthesis, transcription, translation, cell cycle control, signal transduction, and stress responses [

4]. The 26S proteasome is a multicatalytic proteinase complex with a highly ordered structure composed of 2 complexes, a 20S core and a 19S regulator. The 20S core is composed of 4 rings of 28 non-identical subunits; 2 rings are composed of 7 alpha subunits and 2 rings are composed of 7 beta subunits. The 19S regulator is composed of a base, which contains 6 ATPase subunits and 2 non-ATPase subunits, and a lid, which contains up to 10 non-ATPase subunits. Proteasomes are distributed throughout eukaryotic cells at a high concentration and cleave peptides in an ATP/ubiquitin-dependent process in a non-lysosomal pathway. An essential function of a modified proteasome, the immunoproteasome, is the processing of class I MHC peptides.

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing have facilitated the identification of novel candidate genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Among these, neurodevelopmental proteasomopathies have emerged as a complex group of syndromes caused by defects in genes related to key proteasome systems, such as the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) and the previously mentioned 26S proteasome [

5,

6]. These syndromes are typically characterized by delayed psychomotor development, behavioral abnormalities, facial dysmorphisms, and multisystemic anomalies.

Proteasome 26S Subunit, ATPase 5 (

PSMC5) emerges a potential candidate for these kinds of disease. Despite it hasn’t a MIM phenotype number associating it with a specific phenotype, it was previously associated with neurodevelopmental disorders [

7]. This gene encodes the proteasome regulatory subunit 8, pivotal for the formation of the 19S core subunit. PSMC5 is an ATPase that belongs to the AAA (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) family, known for their non proteolytic chaperone-like functions [

8,

9]. In addition to participation in proteasome functions, this subunit may participate in transcriptional regulation since it has been shown to interact with the thyroid hormone receptor and retinoid X receptor-alpha.

In addition to its role in proteasome-mediated protein degradation, this subunit may also be involved in transcriptional regulation, as it has been shown to interact with both the thyroid hormone receptor and retinoid X receptor-alpha [

10]. As documented, intracerebroventricular administration of shRNA PSMC5 in mice showed neuroprotective effects. In fact, PSMC5 was identified as potential therapeutic target for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases involving neuroinflammation-associated cognitive deficits and motor impairments induced by microglial activation [

11].

In this study, whole exome sequencing (WES) identified a de novo variant, c.959C>G (p.Pro320Arg), in the PSMC5 gene in a patient presenting with global developmental delay and mild intellectual disability. We propose this variant as a potential mutational hotspot, as it has previously been identified in six individuals with clinical features similar to those observed in our patient. This study aims to strengthen the association between PSMC5 and neurodevelopmental disorders, corroborating evidence reported in previous research.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Report

The patient is female second-born child, delivered at term following a pregnancy complicated by the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis at the fifth month of gestation. The condition was treated with levothyroxine (Eutirox). Delivery was unremarkable (eutocic). Psychomotor development was delayed. Previous genetic investigations performed at other centers included conventional karyotyping, array-CGH, and methylation testing for Angelman Syndrome (AS), all of which returned normal results.

In 2015, the patient was hospitalized at Oasi IRCCS Research Institute and was discharged with a diagnosis of mixed specific developmental disorder. In 2023, she was readmitted for follow-up and further diagnostic investigations due to emerging behavioral disturbances.

Phenotypic evaluation revealed a body weight of 49 kg and a height of 154 cm. The patient exhibited muscular hypotonia and distinct facial dysmorphisms, including a small mouth, slightly down slanting palpebral fissures, and a nasal tip mildly turned downward. Additional clinical findings included a pilonidal sinus, valgus knees, and bilateral flat-valgus pronated feet. A thyroid goiter was also noted on physical examination. Thyroid ultrasound revealed a significantly enlarged left lobe with a hypoechoic and heterogeneous appearance, resembling a pseudo nodular pattern. The liver appears within normal limits, with regular contours and preserved echotexture. The gallbladder is in its normal position, with regular walls and no echogenic images suggestive of lithiasis within its lumen. The intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tracts, as well as the portal vein, show normal appearance. The pancreas is normal in size and morphology, with preserved echotexture. The spleen is within normal limits, with regular contours. The kidneys are in their usual position, with normal shape and volume, appropriate parenchymal representation, and a normal cortico-medullary ratio, with no evidence of lithiasis. The urinary bladder shows regular wall thickness.

Over the past year, oppositional behavior, mood swings, and episodes of aggression have been reported (e.g., throwing objects, punching doors, and occasionally showing physical aggression towards her mother, siblings, and grandmother). These behavioral issues are not observed in the school environment or other social contexts.

Limited willingness to engage in interaction, with frequent avoidance and withdrawal behaviors (e.g., covering her face, turning away, becoming mute), as well as oppositional traits. At discharge, she received a diagnosis of syndrome of global developmental delay with mild intellectual disability.

2.2. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

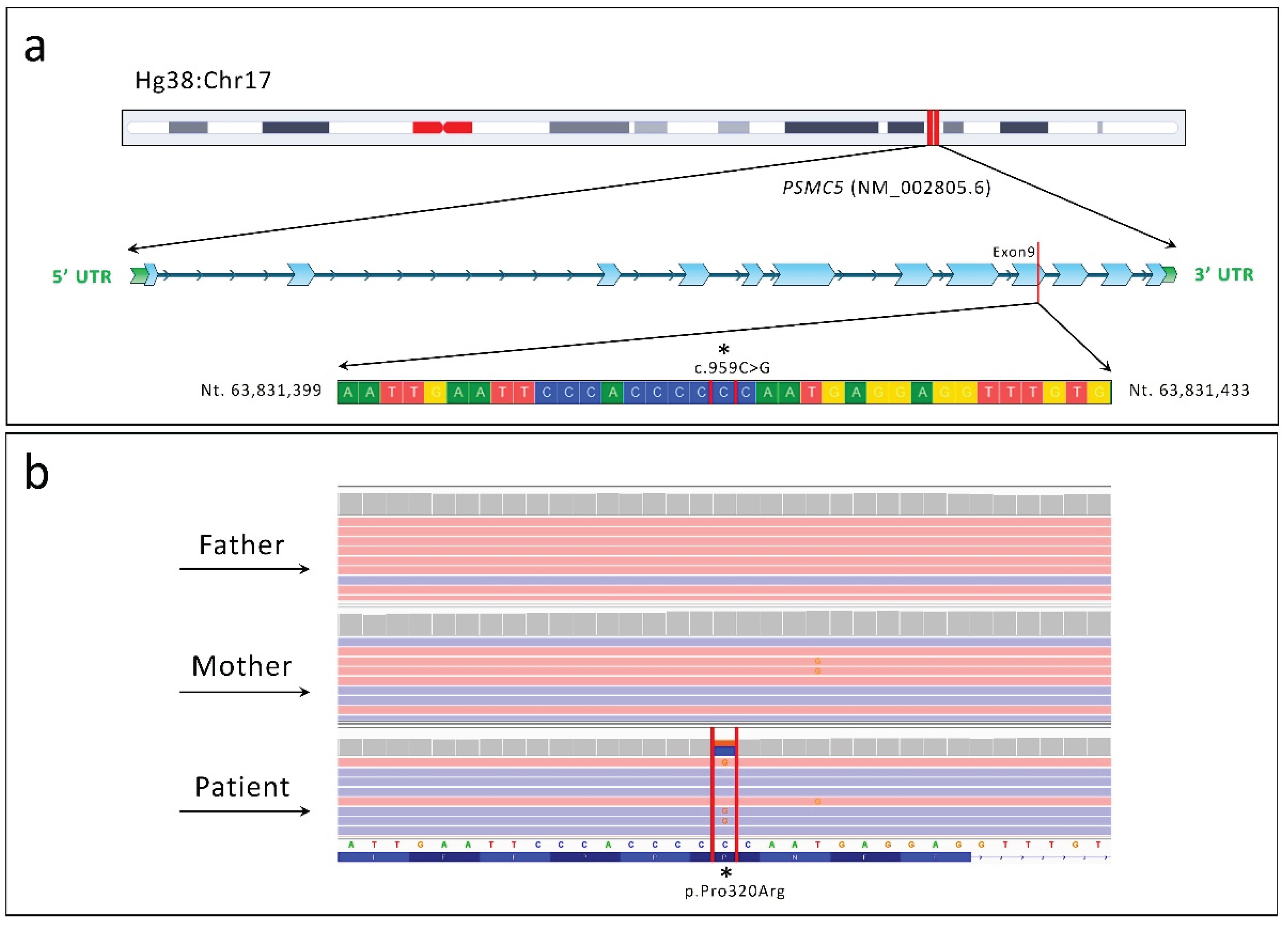

WES analysis identified the de novo variant c.959C>G p.Pro320Arg within the

PSMC5 (NM_002805.6) gene (

Figure 1).

The DOMINO tool indicated a very high probability of autosomal dominant (AD) transmission, with a score of 0.981 (where 0 indicates autosomal recessive and 1 indicates autosomal dominant inheritance). Variant was confirmed by the conventional Sanger sequencing.

According to the ACMG criteria, the variant was classified as pathogenic. PhyloP conservation score was of 7.905, indicating a strong conservation of the mutated nucleotide. Furthermore, multiple in-silico algorithms classified the genetic variant as pathogenic strong (

Table 1).

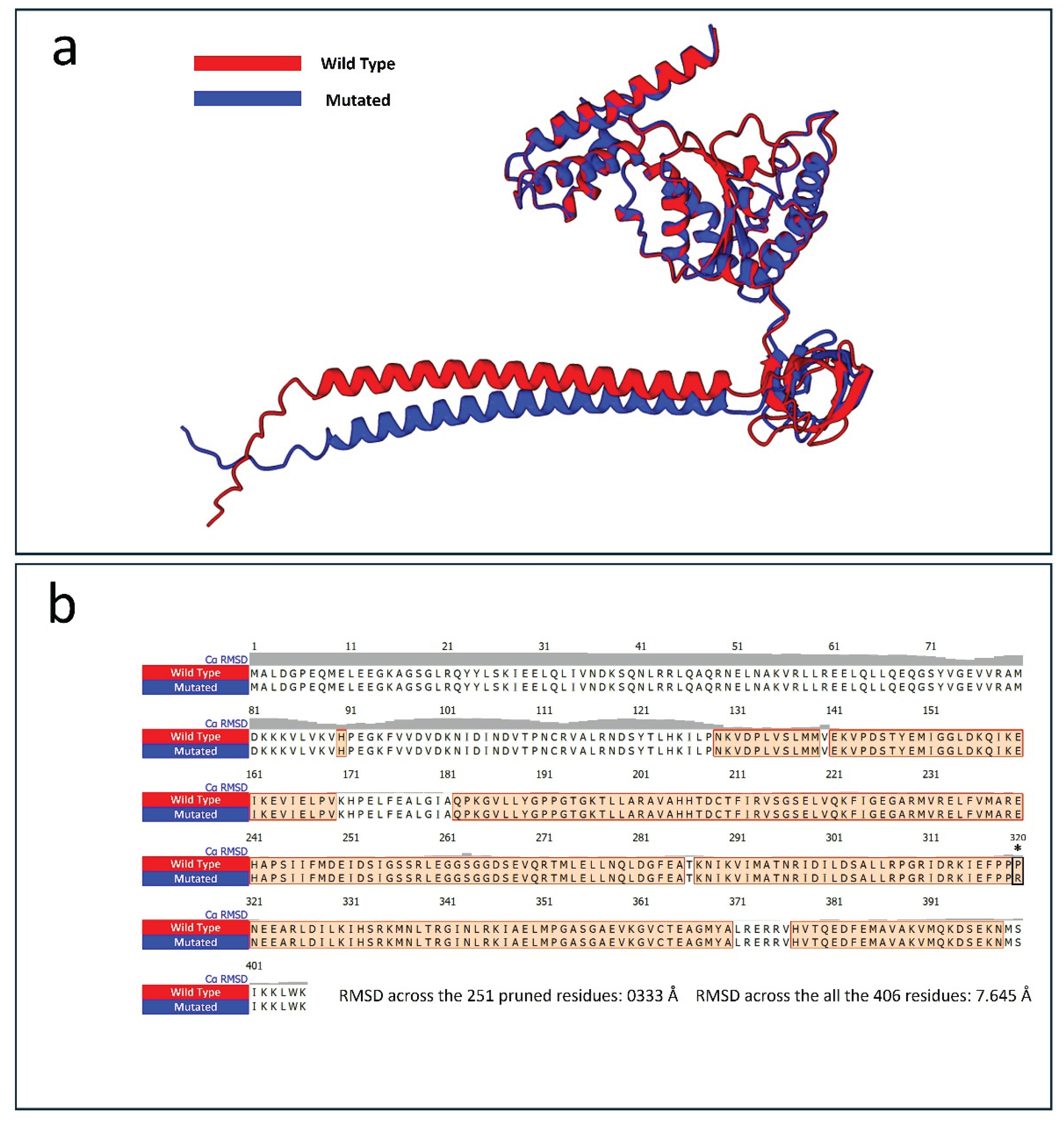

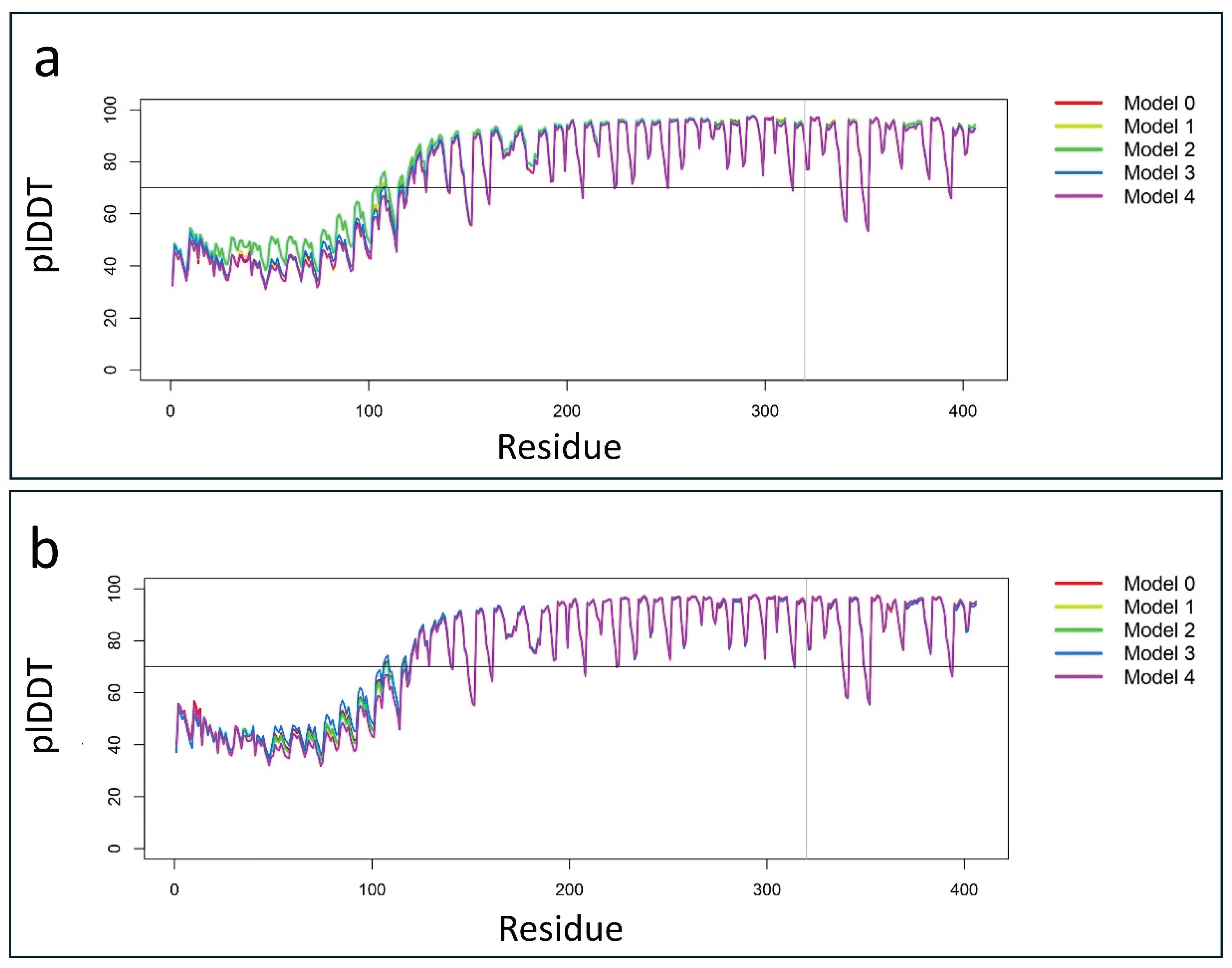

2.3. Protein Structural Prediction

Protein structure prediction analysis using the AlphaFold 3 algorithm was performed, selecting the best model based on the highest predicted Local Distance Difference Test (plDDT) score. The comparison between the wild-type and mutated PSMC5 structures revealed notable differences. Protein alignment showed that 251 out of 406 residues were aligned with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.333 Å, indicating a close structural similarity in that region (

Figure 2).

However, when considering all 406 residues, the RMSD increased to 7.645 Å, reflecting overall structural deviation. Despite the apparent similarity from the aligned region, alterations were observed in the hydrogen bond patterns and overall organization of the mutated protein compared to the wild type. The total number of hydrogen bonds observed in the selected model was 339 for the wild-type PSMC5, compared to 337 in the mutated protein.

Table 2 lists the unique 23 hydrogen bonds present only in the wild type protein and absent in the mutated p.Pro320Arg.

As predicted, the mutated PSMC5 protein exhibited a total of 21 hydrogen bonds that were not present in the wild-type structure. These unique interactions are listed in

Table 3.

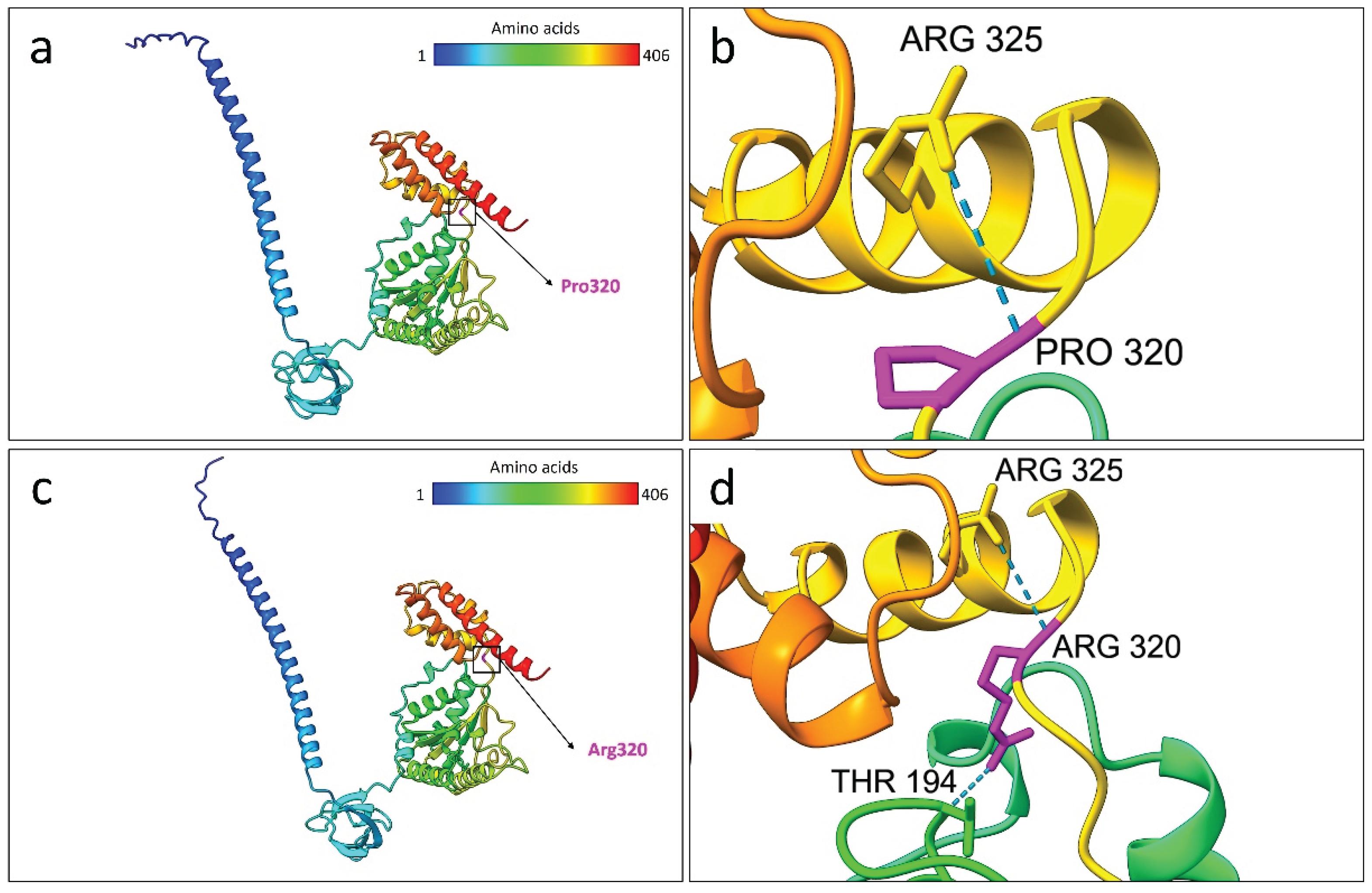

As predicted by the structural prediction analysis, the wild type residue Pro320 formed a hydrogen bond interaction with Arg325. On the other hand, the mutated Arg320 formed an additional bond with Thr194. This bonding differences in the AlphaFold3 models are depicted in

Figure 3.

3. Discussion

In this study we report an individual presenting with global developmental delay and mild intellectual disability. WES identified the de novo genetic variant c.959C>G p.Pro320Arg in PSMC5 gene. NGS analysis did not reveal pathogenic variants in known genes associated with the patient’s phenotype. Additionally, conventional karyotyping, array-CGH, and methylation testing for Angelman Syndrome (AS) yielded normal results. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other genetic variants not detected by WES may have contributed to the patient’s clinical presentation.

As reported by DOMINO tool, PSMC5 shows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Currently, there are no MIM phenotype number associating

PSMC5 with a specific phenotype. It is worth noting that the PSMC5 Foundation (

https://psmc5.org/) was established to support research into diseases with neurodevelopmental features associated with the PSMC5 gene. The foundation was created thanks to the efforts of three families, with the aim of advancing scientific studies related to PSMC5-related neurodevelopmental disorders.

The variant was recently annotated in the ClinVar database by the OMIM submitter as a variant of uncertain significance (ID: VCV003899901.1; Submission date: 25 May 2025). Notably, in ClinVar database, a total of 38 PSMC5-related entries are currently reported, excluding our own submission. Among these, 23 are single nucleotide variants (SNVs), of which 19 are classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), most without a specified associated phenotype. One of these SNVs, the p.Met80Val variant (VCV003377264.1), has been described in association with a neurodevelopmental disorder, while four variants are classified as benign. Additionally, two small deletions are listed, both classified as VUS; notably, the p.Lys393del variant (VCV003600378.1) has been linked to a “PSMC5-related neurodevelopmental disorder”. The remaining 13 entries correspond to copy number variants (CNVs), for which pathogenicity classifications and associated phenotypes are largely undefined.

To date, this variant has not been reported in either the gnomAD or dbSNP databases. Notably, the same p.Pro320Arg variant reported in this study was also identified in six individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders [

12]. Two of these cases are documented in the DECIPHER database as de novo variants in patients with IDs 306096 and 307251. Patient 306096 presented with delayed speech and language development, joint hypermobility, and motor delay. Patient 307251 exhibited abnormalities of the proximal phalanx of the thumb, deeply set eyes, global developmental delay, a prominent forehead, a thin vermilion border, a wide mouth, and a broad nose. The phenotypic comparison between the individual examined in this study and those previously reported is presented in the

Table S1, adapted from a previous study [

12]. Based on these previously reported patients in the DECIPHER database, the

PSMC5 gene was recently included in the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Gene database (Q1 2025 Release Notes) with a score of 3, indicating relatively weak but emerging evidence for its association with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

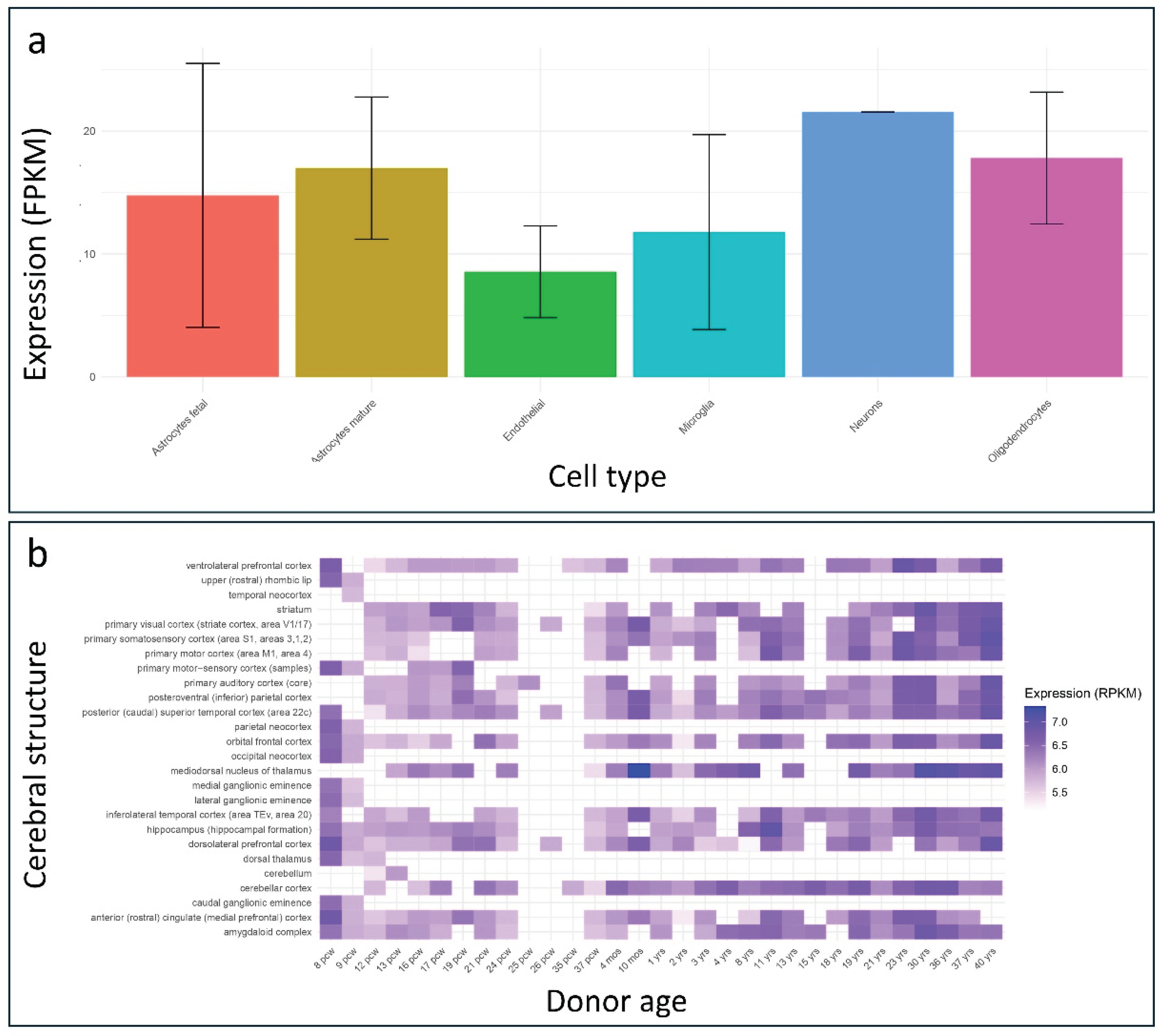

According to the BrainRNA-Seq database, the

PSMC5 gene is highly expressed in the human brain, with particularly elevated expression in neurons (

Figure 4a).

Complementary data from the BrainSpan developmental transcriptomic database indicate that

PSMC5 maintains high expression levels across various cerebral structures throughout development and adulthood (

Figure 4b). Notably, the highest expression levels were observed in the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus at 10 months, 36 years, and 40 years of age. This brain region has been consistently implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders and is known to play a critical role in cognitive functioning [

13,

14].

The mutation is located at residue 320, within the 186–406 amino acid region of PSMC5, which has been described in mice as mediating the interaction with PRPF19 [

15]. PRPF19 is a subunit of the spliceosome complex, involved in the mRNA splicing process. It exhibits identical protein binding and ubiquitin ligase activities. Importantly, PRPF19 and other spliceosome components have been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders [

16]. This variant has been proposed as a potential mutational hotspot—a hypothesis with which we concur. Functional in vitro studies investigating both PSMC5 insufficiency and the Pro320Arg mutation revealed that they impair proteasome activity and trigger apoptosis. Specifically, the Pro320Arg mutation disrupts proteasome function by altering the interaction between the 19S regulatory particle and the 20S core particle, as demonstrated by in vitro assays [

12].

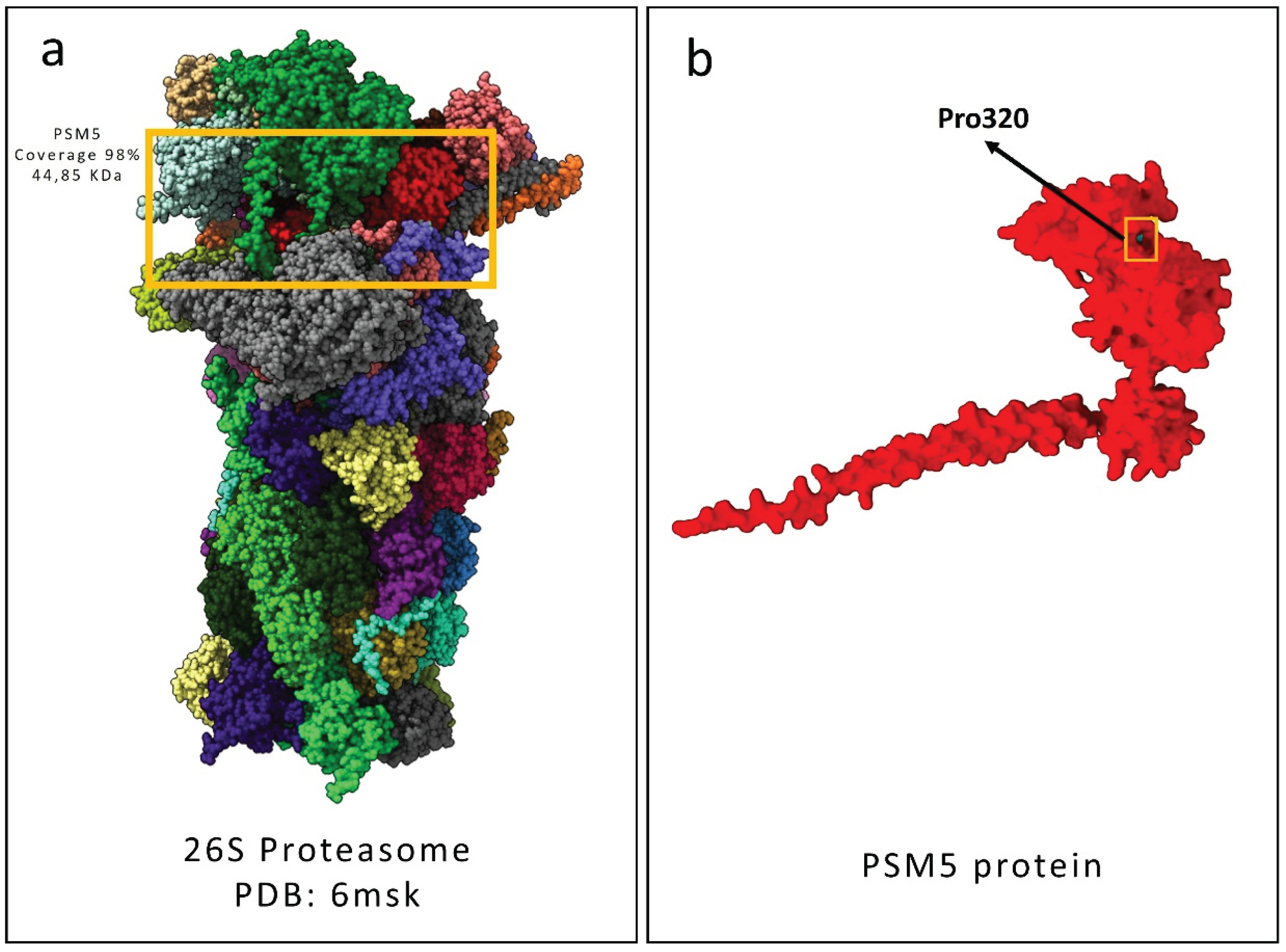

According to the Complex Portal entry for the 26S proteasome complex (ID: CPX-5993), six curated structural models of this protein machinery are available. For our analysis, we selected the structure with PDB ID: 6msk (DOI: 10.2210/pdb6msk/pdb), which provides high-resolution structural information and the highest coverage. However, it is important to note that the Complex Portal does not explicitly specify the amino acid residues of PSMC5 involved in interactions with other proteasome subunits.

Figure 5 shows the 26S PBD 6msk model compared with our best predicted model of PSMC5 generated using AlphaFold3.

A potential limitation of this study lies in the difficulty of accurately predicting the structural and functional consequences of the Pro320Arg mutation within the PSMC5 protein on the entire 26S proteasome complex. In fact, it would be highly interesting to perform a structural prediction of the entire 26S proteasome complex using AlphaFold-Multimer, including the PSMC5 protein carrying the variant identified in our study. However, due to the large number of polypeptide subunits that make up the 26S proteasome (over 10,000 amino acids in total), such an analysis would require significant computational resources, both in terms of processing power and RAM capacity. For this reason, we plan to postpone this analysis to a later stage, with the aim of estimating the mutation’s potential impact on the folding and architecture of the full proteasome complex. An alternative approach could involve the modelling of selected subcomplexes that include the mutated PSMC5 protein; however, this strategy may not provide a reliable estimation of the global structural impact. We anticipate that future advances in more powerful and cost-effective predictive algorithms, as well as greater access to high-performance computing infrastructures, will help overcome these current limitations.

It is also important to highlight that the patient examined in this study presented with thyroid abnormalities. As detailed in the clinical documentation, a thyroid ultrasound revealed a significantly enlarged left lobe with a hypoechoic and heterogeneous appearance, resembling a pseudonodular pattern. Additionally, the patient’s mother reported episodes of swallowing difficulty. Notably, both the mother and maternal grandmother have a history of thyroid disorders—thyroiditis and nodular goiter, respectively. We hypothesize that the de novo variant identified in the

PSMC5 gene may contribute to the development or worsening of thyroid abnormalities in the patient. This assumption is supported by previous findings indicating that the encoded protein subunit may be involved in transcriptional regulation, having been shown to interact with both the thyroid hormone receptor and retinoid X receptor-alpha [

10]. Further studies are warranted to explore this potential interaction and to clarify the role of PSMC5 in thyroid hormone secretion and metabolism. It is worth noting that thyroid abnormalities were not reported in the six previously described individuals carrying the same genetic variant. Nonetheless, variants in other genes encoding subunits of the 26S proteasome—such as

PSMA1,

PSMA3,

PSMD3, and

PSMD2—have been associated with thyroid dysfunction [

17].

This study aims to deepen the understanding of the PSMC5 gene by expanding the spectrum of associated phenotypes and highlighting its previously suggested potential as a therapeutic target. Although functional studies are essential to confirm the association of the PSMC5 gene and to validate the variant we identified as a potential mutational hotspot, we have submitted this variant to ClinVar (SUB15371434), classifying it as pathogenic and contributing to its first annotation with this classification in the database.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Libraries Preparation and WES Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes of the patient and both parents, following the previously described procedure [

18]. Library preparation for the trio analysis and exome capture was performed using the Agilent SureSelect V7 Kit (Santa Clara, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was carried out using the Illumina HiSeq 3000 platform (San Diego, CA, USA), achieving coverage of at least 20× for 97% of the targeted regions. Variant filtering was performed based on (i) presumed inheritance patterns—recessive, de novo, or X-linked—and (ii) a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 1%, referencing population databases including 1000 Genomes, ESP6500, ExAC, and GnomAD. The human reference genome assembly HG38 was used for variant alignment and analysis. All identified variants were subsequently validated by conventional Sanger sequencing, performed with the BigDye™ Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on the SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.2. Data Analysis

All the common variants, non-exonic polymorphisms, were excluded, keeping polymorphisms with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <1% in the following public databases: gnomAD Exomes v.3.1.2, 1000 Genome Project and Exome Sequencing Project (accessed on 10 September 2024). The pathogenic variants were searched on The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD Professional 2025.1,

https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/introduction.php, accessed on 23 May 2025). Franklin by QIAGEN for filtering and prioritizing the genetic variants from the vcf file. The identified variant was classified using the “American College of Medical Genetics” (ACMG) guidelines and criteria [

19]. Multiple in silico analysis was performed using the VarSome platform [

20]. BrainRNAseq database (

https://brainrnaseq.org/) (accessed on 23 May 2025) was used for obtaining the expression of

PSMC5 gene from different brain cells. Furthermore, BrainSpan database (

https://www.brainspan.org/) (accessed on 23 May 2025) was used for retrieving the data of transcriptomic data of cortical and subcortical structures across the full course of human brain development. Complex Portal (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/complexportal/home) (accessed on 23 May 2025) was used for studying the PSMC5 interactions within the proteasome 26 and for retrieving the accurate Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure of the P26 structure. Specifically, the structure considered was the 6msk structure (10.2210/pdb6msk/pdb). The structures of the wild type and mutated PSMC5 proteins were predicted using the AlphaFold3 server (

https://alphafoldserver.com/) (accessed on 23 May 2025). The “best model” with the highest plDDT value was selected across five models for each prediction (

Figure 6).

These structures were visualized and modeled using UCSF ChimeraX software version 1.8.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we identified the c.959C>G (p.Pro320Arg) variant in the PSMC5 gene in a patient diagnosed with global developmental delay and mild intellectual disability. This study aims to expand the spectrum of phenotypes associated with PSMC5 and with this specific genetic variant, which has already been described in six other individuals. We emphasize the need of functional studies to validate the impact of this variant on the human phenotype and on the structural and biological stability of the 26S proteasome complex, which is pivotal for numerous cellular processes. We believe that the findings of this study may support the inclusion of PSMC5 among the genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders with an associated MIM phenotype number. Although such studies are necessary to confirm the gene-disease association and to validate the identified variant as a potential mutational hotspot, we have already submitted this variant to ClinVar (SUB15371434), classifying it as pathogenic and contributing to its first annotation with this classification in the database.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Phenotypic comparison of the patient examined in this study, with those reported by Yu et al. 2024 (Case 1, 2, 3 and 4) in addition to those reported in DECIPHER database (306096 and 307251).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V., A.M., F.C. and S.T.; methodology, M.V., A.M., C.P., D.G., V.G., A.R. F.C. and S.T.; software, M.V., A.M., F.C. and S.T.; validation, M.V., A.M., D.G., F.C. and S.T., Y.Y.; investigation, M.V., A.M., D.G., V.G., S.S., C.F., F.C. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V., F.C. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, M.V., A.M., S.S., C.F., F.C. and S.T.; supervision, S.S., C.F., F.C. and S.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health “Ricerca Corrente 2017–2023” and 5xmille.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee “Comitato Etico IRCCS Sicilia-Oasi Maria SS”, Prot. CE/193, as of 5 April 2022, approval code: 2022/04/05/CE-IRCCS-OASI/52.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgements for this manuscript go to Eleonora Di Fatta for her valuable assistance in the translation, preparation and formatting of the text. Furthermore, we would like to sincerely thank Angelo Gloria, Valeria Chiavetta and Rosanna Galati Rando for their technical contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMG |

American college of medical genetics and genomics |

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorder |

| IGV |

Integrated genomics viewer |

| MAF |

Minor allele frequency |

| NGS |

Next generation sequencing |

| SFARI |

Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative |

| VUS |

Variant of uncertain significance |

References

- Bard, J.A.M.; Goodall, E.A.; Greene, E.R.; Jonsson, E.; Dong, K.C.; Martin, A. Structure and Function of the 26S Proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem 2018, 87, 697–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, M.; Zhao, X.; Sahara, K.; Ohte, Y.; Hirano, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Yashiroda, H.; Murata, S. Assembly Mechanisms of Specialized Core Particles of the Proteasome. Biomolecules 2014, 4, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, I.; Glickman, M.H. Proteasome in Action: Substrate Degradation by the 26S Proteasome. Biochem Soc Trans 2021, 49, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, L.; Paine, S.; Sheppard, P.W.; Mayer, R.J.; Roelofs, J. Assembly, Structure, and Function of the 26S Proteasome. Trends Cell Biol 2010, 20, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papendorf, J.J.; Ebstein, F.; Alehashemi, S.; Piotto, D.G.P.; Kozlova, A.; Terreri, M.T.; Shcherbina, A.; Rastegar, A.; Rodrigues, M.; Pereira, R.; et al. Identification of Eight Novel Proteasome Variants in Five Unrelated Cases of Proteasome-Associated Autoinflammatory Syndromes (PRAAS). Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuinat, S.; Bézieau, S.; Deb, W.; Mercier, S.; Vignard, V.; Isidor, B.; Küry, S.; Ebstein, F. Understanding Neurodevelopmental Proteasomopathies as New Rare Disease Entities: A Review of Current Concepts, Molecular Biomarkers, and Perspectives. Genes Dis 2024, 11, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küry, S.; Stanton, J.E.; van Woerden, G.; Hsieh, T.-C.; Rosenfelt, C.; Scott-Boyer, M.P.; Most, V.; Wang, T.; Papendorf, J.J.; de Konink, C.; et al. Unveiling the Crucial Neuronal Role of the Proteasomal ATPase Subunit Gene PSMC5 in Neurodevelopmental Proteasomopathies 2024.

- Galperin, E.; Jang, E.R.; Anderson, D.; Jang, H. The (AAA+) ATPases PSMC5 and VCP/P97 Control ERK1/2 Signals Transmitted through the Shoc2 Scaffolding Complex. The FASEB Journal 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.R.; Jang, H.; Shi, P.; Popa, G.; Jeoung, M.; Galperin, E. Spatial Control of Shoc2 Scaffold-Mediated ERK1/2 Signaling Requires Remodeling Activity of the ATPase PSMC5. J Cell Sci 2015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyle, J.; Tan, K.H.; Fisher, E.M.C. Localization of Genes Encoding Two Human One-Domain Members of the AAA Family: PSMC5 (the Thyroid Hormone Receptor-Interacting Protein, TRIP1) and PSMC3 (the Tat-Binding Protein, TBP1). Hum Genet 1997, 99, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, W.; Bao, K.; Zhou, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Lan, X.; Zhao, J.; Lu, D.; Xu, Y.; et al. PSMC5 Regulates Microglial Polarization and Activation in LPS-Induced Cognitive Deficits and Motor Impairments by Interacting with TLR4. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.-Q.; Carmichael, J.; Collins, G.A.; D’Agostino, M.D.; Lessard, M.; Firth, H. V; Harijan, P.; Fry, A.E.; Dean, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. PSMC5 Insufficiency and P320R Mutation Impair Proteasome Function. Hum Mol Genet 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, B.R.; Gao, W.-J. Development of Thalamocortical Connections between the Mediodorsal Thalamus and the Prefrontal Cortex and Its Implication in Cognition. Front Hum Neurosci 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouhaz, Z.; Fleming, H.; Mitchell, A.S. Cognitive Functions and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Involving the Prefrontal Cortex and Mediodorsal Thalamus. Front Neurosci 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sihn, C.-R.; Cho, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, T.R.; Kim, S.H. Mouse Homologue of Yeast Prp19 Interacts with Mouse SUG1, the Regulatory Subunit of 26S Proteasome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 356, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, Q.; Bayat, A.; Battig, M.R.; Zhou, Y.; Bosch, D.G.M.; van Haaften, G.; Granger, L.; Petersen, A.K.; Pérez-Jurado, L.A.; et al. Spliceosome Malfunction Causes Neurodevelopmental Disorders with Overlapping Features. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budny, B.; Szczepanek-Parulska, E.; Zemojtel, T.; Szaflarski, W.; Rydzanicz, M.; Wesoly, J.; Handschuh, L.; Wolinski, K.; Piatek, K.; Niedziela, M.; et al. Mutations in Proteasome-Related Genes Are Associated with Thyroid Hemiagenesis. Endocrine 2017, 56, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musumeci, A.; Vinci, M.; Treccarichi, S.; Greco, D.; Rizzo, B.; Gloria, A.; Federico, C.; Saccone, S.; Musumeci, S.A.; Calì, F. Potential Association of the CSMD1 Gene with Moderate Intellectual Disability, Anxiety Disorder, and Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Traits. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopanos, C.; Tsiolkas, V.; Kouris, A.; Chapple, C.E.; Albarca Aguilera, M.; Meyer, R.; Massouras, A. VarSome: The Human Genomic Variant Search Engine. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1978–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Chromosomal localization and next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis identifying the c.959C>G (p.Pro320Arg) variant in the PSMC5 gene (NM_002805.6). (a) Schematic representation of the chromosomal localization of the PSMC5 gene, highlighting the identified variant within exon 9. (b) Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) snapshot showing the heterozygous c.959C>G variant in the patient, absent in both healthy parents, confirming its de novo origin.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal localization and next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis identifying the c.959C>G (p.Pro320Arg) variant in the PSMC5 gene (NM_002805.6). (a) Schematic representation of the chromosomal localization of the PSMC5 gene, highlighting the identified variant within exon 9. (b) Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) snapshot showing the heterozygous c.959C>G variant in the patient, absent in both healthy parents, confirming its de novo origin.

Figure 2.

Protein structure alignment performed with the two best predicted model of both the wild-type (red) and the mutated Pro320Arg PSMC5 proteins (blue). (a) Graphical representation of the superimposed structure alignment carried out using the best AlphaFold3 models for both the wild type and the mutated Pro320Arg PSMC5. Superimposition was carried out using UCSF ChimeraX software version 1.8. (b) Depiction of the aligned amino acids resulted from the protein structure alignment. Root main standard deviation (RMSD) in indicated in the Figure and it was expressed in Angstroms (Å).

Figure 2.

Protein structure alignment performed with the two best predicted model of both the wild-type (red) and the mutated Pro320Arg PSMC5 proteins (blue). (a) Graphical representation of the superimposed structure alignment carried out using the best AlphaFold3 models for both the wild type and the mutated Pro320Arg PSMC5. Superimposition was carried out using UCSF ChimeraX software version 1.8. (b) Depiction of the aligned amino acids resulted from the protein structure alignment. Root main standard deviation (RMSD) in indicated in the Figure and it was expressed in Angstroms (Å).

Figure 3.

Structural comparison between the selected best models of the wild-type and Pro320Arg-mutated PSMC5 proteins based on AlphaFold3 predictions. (a) Predicted 3D model of the wild-type PSMC5 protein. The color gradient represents the amino acid sequence from N-terminus (blue) to C-terminus (red). The position of Pro320 is highlighted by both a black square and arrow. (b) Close-up view of the wild-type Pro320 residue (magenta), showing a hydrogen bond with Arg325. (c) Predicted 3D model of the Pro320Arg-mutated PSMC5 protein, colored from N-terminus (blue) to C-terminus (red). The mutated Arg320 residue is indicated by a black square and arrow. (d) Close-up view of Arg320 (magenta) in the mutant protein, forming two hydrogen bonds with Arg325 and Thr194. All the protein models were generated using the AlphaFold3 server and visualized using UCSF ChimeraX version 1.8.

Figure 3.

Structural comparison between the selected best models of the wild-type and Pro320Arg-mutated PSMC5 proteins based on AlphaFold3 predictions. (a) Predicted 3D model of the wild-type PSMC5 protein. The color gradient represents the amino acid sequence from N-terminus (blue) to C-terminus (red). The position of Pro320 is highlighted by both a black square and arrow. (b) Close-up view of the wild-type Pro320 residue (magenta), showing a hydrogen bond with Arg325. (c) Predicted 3D model of the Pro320Arg-mutated PSMC5 protein, colored from N-terminus (blue) to C-terminus (red). The mutated Arg320 residue is indicated by a black square and arrow. (d) Close-up view of Arg320 (magenta) in the mutant protein, forming two hydrogen bonds with Arg325 and Thr194. All the protein models were generated using the AlphaFold3 server and visualized using UCSF ChimeraX version 1.8.

Figure 4.

Brain expression of PSMC5 across human brain structures. (a) Barplot illustrating PSMC5 expression levels, measured in fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM), across various human brain cell types. Data were retrieved from the BrainRNA-Seq database. (b) Heatmap representing developmental expression patterns of PSMC5, measured in reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM), across multiple human brain regions at different developmental stages. Data were obtained from the BrainSpan database.

Figure 4.

Brain expression of PSMC5 across human brain structures. (a) Barplot illustrating PSMC5 expression levels, measured in fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM), across various human brain cell types. Data were retrieved from the BrainRNA-Seq database. (b) Heatmap representing developmental expression patterns of PSMC5, measured in reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM), across multiple human brain regions at different developmental stages. Data were obtained from the BrainSpan database.

Figure 5.

Structural depiction of the human 26S proteasome complex with a focus on the PSMC5 subunit. (a) Graphical representation of the 26S proteasome structure (PDB ID: 6MSK) deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with the PSMC5 subunit highlighted in red. (b) predicted wild-type PSMC5 protein structure generated using the AlphaFold3 server is shown. Wild type Pro320 is indicated by the both the yellow square and the black arrow.

Figure 5.

Structural depiction of the human 26S proteasome complex with a focus on the PSMC5 subunit. (a) Graphical representation of the 26S proteasome structure (PDB ID: 6MSK) deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with the PSMC5 subunit highlighted in red. (b) predicted wild-type PSMC5 protein structure generated using the AlphaFold3 server is shown. Wild type Pro320 is indicated by the both the yellow square and the black arrow.

Figure 6.

Line plots illustrate the variations in predicted local Distance Difference Test (plDDT) scores across the five AlphaFold3 models for both the wild-type and p.Pro320Arg-mutated PSMC5 proteins. (a) The plot shows plDDT values for the wild-type PSMC5 predictions, highlighting “Model 3” as the best-performing model, with an average plDDT score of 81.125. (b) Similarly, the plot displays plDDT variations for the mutated p.Pro320Arg PSMC5 protein, where “Model 3” also emerged as the best model, with an average plDDT score of 80.396.

Figure 6.

Line plots illustrate the variations in predicted local Distance Difference Test (plDDT) scores across the five AlphaFold3 models for both the wild-type and p.Pro320Arg-mutated PSMC5 proteins. (a) The plot shows plDDT values for the wild-type PSMC5 predictions, highlighting “Model 3” as the best-performing model, with an average plDDT score of 81.125. (b) Similarly, the plot displays plDDT variations for the mutated p.Pro320Arg PSMC5 protein, where “Model 3” also emerged as the best model, with an average plDDT score of 80.396.

Table 1.

Multiple in silico analysis for the variant de novo variant c.959C>G p.Pro320Arg in PSMC5 gene identified by Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) analysis.

Table 1.

Multiple in silico analysis for the variant de novo variant c.959C>G p.Pro320Arg in PSMC5 gene identified by Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) analysis.

| Tool |

Prediction |

Score |

| BayesDel addAF |

Pathogenic Strong |

0.468 |

| MetaRNN |

Pathogenic Strong |

0.977 |

| BayesDel noAF |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.434 |

| MetaSVM |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.928 |

| REVEL |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.917 |

| MetaLR |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.835 |

| AlphaMissense |

Pathogenic Strong |

0.996 |

| EIGEN |

Pathogenic Strong |

1.070 |

| EIGEN PC |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.965 |

| FATHMM-XF |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.963 |

| Mutation assessor |

Pathogenic Moderate |

4.180 |

| MutPred |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.858 |

| PrimateAI |

Pathogenic Moderate |

0.898 |

| PROVEAN |

Pathogenic Moderate |

-8.170 |

| FATHMM-MKL |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.992 |

| LIST-S2 |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.979 |

| LRT |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.000 |

| M-CAP |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.583 |

| SIFT |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.000 |

| SIFT4G |

Pathogenic Supporting |

0.000 |

| BLOSUM |

Uncertain |

-5.000 |

| DANN |

Uncertain |

0.998 |

| DEOGEN2 |

Uncertain |

0.788 |

| FATHMM |

Uncertain |

-1.650 |

| MutationTaster |

Pathogenic |

1.000 |

| MVP |

Uncertain |

0.896 |

Table 2.

List of the 23 hydrogen bonds identified in the best predicted wild-type PSMC5 model that are absent in the mutated p.Pro320Arg variant.

Table 2.

List of the 23 hydrogen bonds identified in the best predicted wild-type PSMC5 model that are absent in the mutated p.Pro320Arg variant.

| Donor residue |

Donor atom |

Acceptor residue |

Acceptor atom |

Distance (Å) |

| Gly17 |

N |

Gly14 |

O |

3.49 |

| Ser26 |

OG |

Gln22 |

O |

3.44 |

| Ser26 |

OG |

Tyr23 |

O |

2.78 |

| Gln40 |

N |

Asn36 |

O |

2.94 |

| Arg49 |

NE |

Asn50 |

OD1 |

3.51 |

| Glu68 |

N |

Leu65 |

O |

3.35 |

| Tyr72 |

OH |

Asn118 |

OD1 |

3.40 |

| Lys101 |

N |

Asp100 |

OD1 |

2.70 |

| Ser120 |

OG |

Asp119 |

OD1 |

3.09 |

| Tyr121 |

OH |

Glu92 |

OE2 |

3.21 |

| His171 |

ND1 |

Glu173 |

OE1 |

2.96 |

| Glu173 |

N |

Glu173 |

OE2 |

2.76 |

| Arg232 |

NE |

Ala228 |

O |

3.35 |

| Gly265 |

N |

Ser263 |

O |

2.78 |

| Ser267 |

OG |

Gly264 |

O |

2.92 |

| Arg297 |

NE |

Asp299 |

OD1 |

3.56 |

| Ser303 |

OG |

Asp302 |

OD1 |

3.56 |

| Leu306 |

N |

Ser303 |

O |

3.22 |

| Arg325 |

NH1 |

Pro320 |

O |

2.93 |

| Asn343 |

N |

Gln380 |

OE1 |

3.00 |

| Ser355 |

OG |

Glu358 |

OE1 |

2.89 |

| Ser400 |

OG |

Glu396 |

O |

2.94 |

| Lys403 |

N |

Met399 |

O |

3.16 |

Table 3.

List of the 21 hydrogen bonds identified in the best predicted p.Pro320Arg mutated PSMC5 model that are absent in the wild-type structure.

Table 3.

List of the 21 hydrogen bonds identified in the best predicted p.Pro320Arg mutated PSMC5 model that are absent in the wild-type structure.

| Donor residue |

Donor atom |

Acceptor residue |

Acceptor atom |

Distance (Å) |

| Glu13 |

N |

Leu11 |

O |

2.80 |

| Ser18 |

OG |

Lys15 |

O |

3.07 |

| Glu68 |

N |

Gln64 |

O |

3.22 |

| Asn106 |

N |

Asp104 |

OD1 |

3.06 |

| Asn118 |

ND2 |

Gln69 |

OE1 |

3.31 |

| Asn129 |

ND2 |

Glu240 |

OE1 |

2.65 |

| Asp132 |

N |

Glu233 |

OE2 |

3.35 |

| Ser136 |

OG |

Asp132 |

O |

3.45 |

| Val140 |

N |

Leu137 |

O |

3.52 |

| Arg201 |

NE |

Glu141 |

OE2 |

2.99 |

| His241 |

ND1 |

Met237 |

O |

3.06 |

| Asp266 |

N |

Ser263 |

O |

2.90 |

| Val269 |

N |

Gly265 |

O |

3.36 |

| Phe283 |

N |

Gln279 |

O |

3.28 |

| Arg320 |

NH2 |

Thr194 |

O |

2.19 |

| Ala324 |

N |

Asn321 |

OD1 |

2.82 |

| Arg325 |

NH1 |

Arg320 |

O |

2.81 |

| Arg375 |

NH1 |

His377 |

O |

2.92 |

| Asp394 |

N |

Val390 |

O |

3.43 |

| Ser395 |

OG |

Gln392 |

O |

2.68 |

| Ser400 |

OG |

Lys397 |

O |

2.81 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).