Introduction

Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy (INAD) constitutes a rare neurodegenerative disorder associated with

PLA2G6 gene mutation that exhibits a diverse spectrum of clinical presentation starting between six months and three years of age, characterized by progressive psychomotor regression, hypotonia and gradually worsening stiffness in all limbs. Some children never achieve walking milestones, or they lose this ability shortly after gaining it. Common accompanying symptoms include misalignment of the eyes (strabismus), involuntary eye movements (nystagmus), and damage to the optic nerve (optic atrophy). The disease progresses rapidly, leading to severe muscle stiffness, declining cognitive abilities, and worsening vision. Sadly, many affected children do not live past their first ten years [

1,

2,

3].

This condition classically arises due to pathogenic alterations in the DNA sequence of phospholipase A2 group VI gene (

PLA2G6), located on the chromosome 22q13.1 region, encoding a cytosolic Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 protein (iPLA2), crucial for cell membrane stability [

4,

5]. Diagnosis relies on clinical presentation, neurophysiological, neuroradiological, and biopsy findings. Advancements in DNA sequencing have facilitated efficient genetic confirmation [

6]. The diagnosis is confirmed through the identification of pathogenic variants within the

PLA2G6 gene via molecular genetic analysis.

PLA2G6 was identified as the causative gene in 2006, with over 150 reported cases, mostly classic INAD, and more than 200 pathogenic variants documented in the Human Gene Pathogenic Variant Database [

7,

8,

9]. Pakistan boasts a populace exceeding 240 million individuals. (

https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/PK). The robust cultural architecture and varying socioeconomical fabric of Pakistani society prompts it to the have the highest prevalence of consanguineous unions globally of approximately 70% [

10,

11].

The cases of INAD are underreported in Pakistan because of non-availability of genetic testing. In this study, we described the inheritance of a novel pathogenic variant in PLA2G6 associated with INAD in Pakistani kindred.

Results

1.1. Clinical Presentation

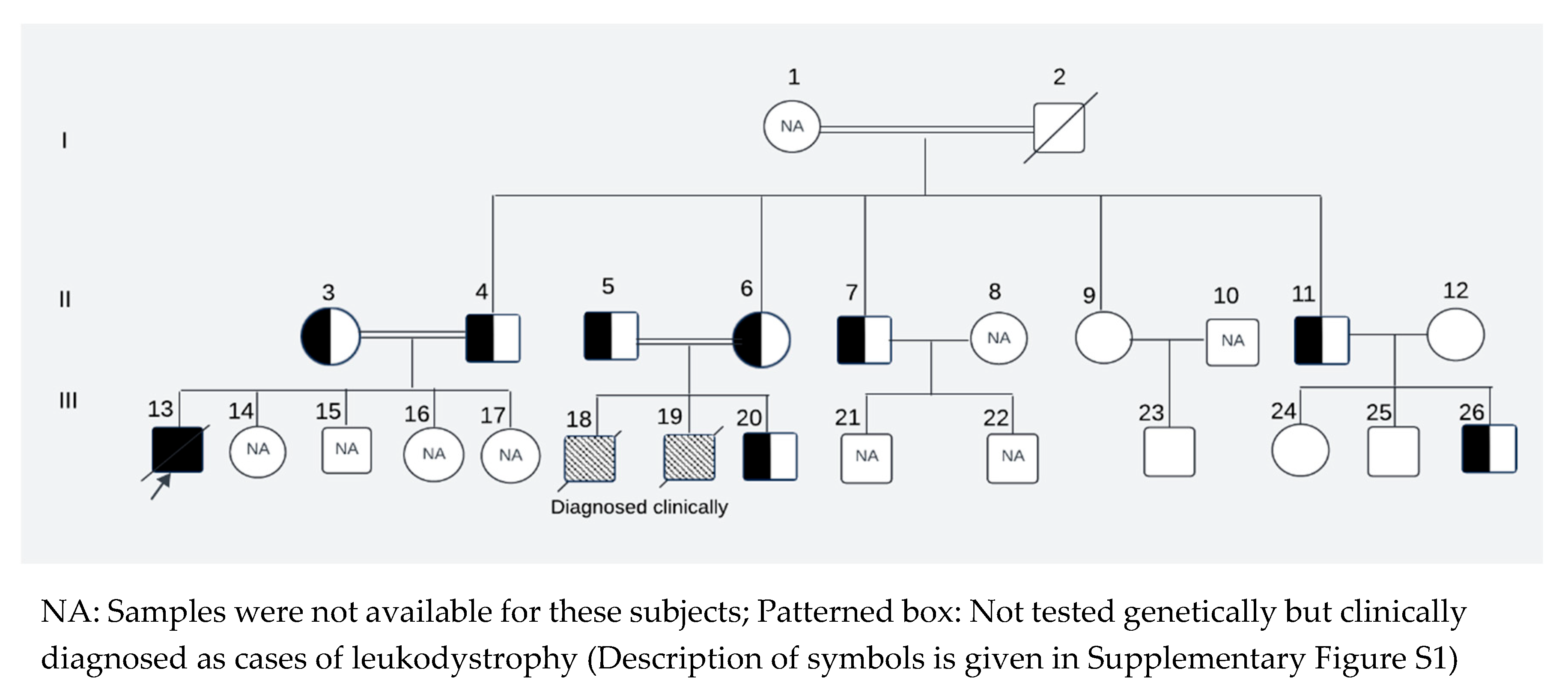

The perinatal histories of the subjects manifested unambiguous normalcy, characterized by unremarkable birth occurrences. All three affected children (III-13, III-18, III-19, Figure 5) were born at full term, with normal Apgar score and healthy birthweight. They exhibited typical developmental trajectories until reached the age of independent standing around 9-10 months of age. Notably, this milestone remained unattained, accompanied by subsequent regression of previously acquired developmental milestones. All three affected children (two siblings and their first cousin) displayed similar clinical presentations, including progressive muscle weakness, impaired motor skills preventing independent standing and walking, hypotonia/hyperreflexia initially, hypotonia at later stage, strabismus, nystagmus, and irritability. Tragically, all succumbed to death because of respiratory failure by the age of 9 years.

1.1. Genetic Analysis

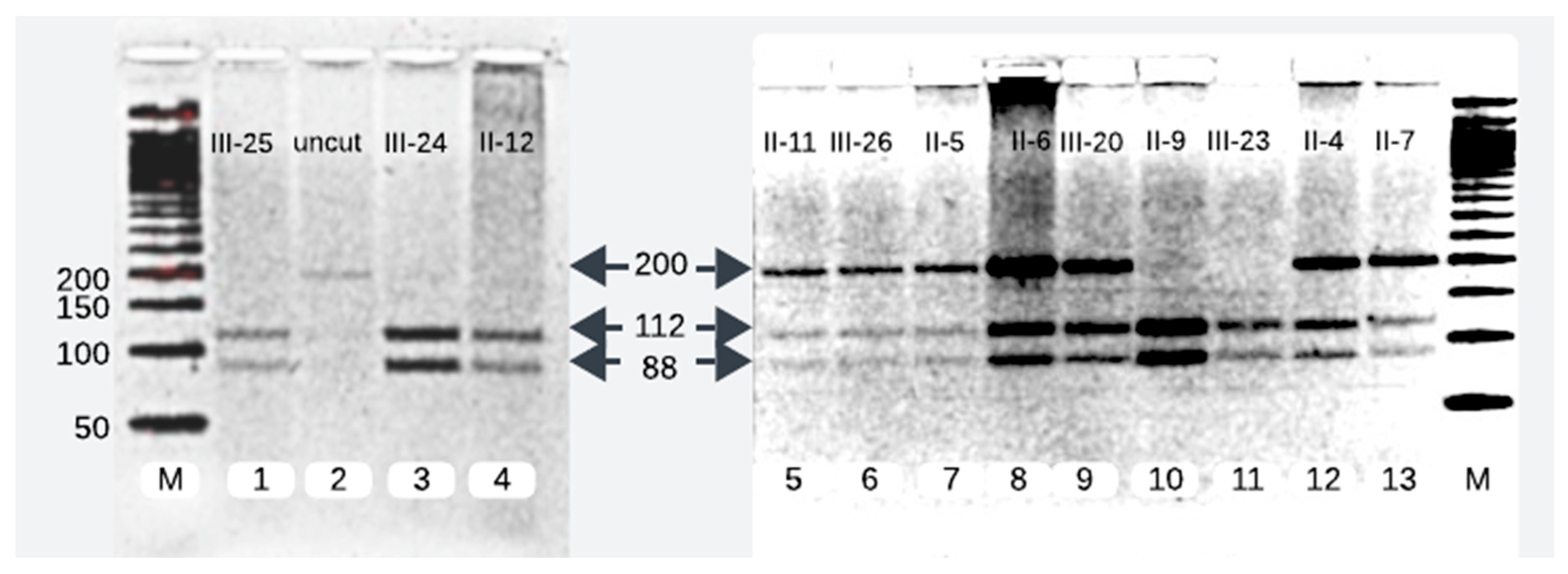

We successfully analyzed 12 samples of the affected family members. RFLP analysis of 7 of the 12 family members disclosed them as heterozygotes of the pathogenic variant (c.1097T>A). The pathogenic variant was characterized by a single band of 200 base pairs (bp), whereas the wild-type allele manifested as two separate bands of 112 bp and 88 bp. On gel electrophoresis, individuals carrying one mutant allele alongside one wild-type allele exhibited three distinct bands, whereas healthy subjects possessing two wild-type alleles displayed two bands (

Figure 1).

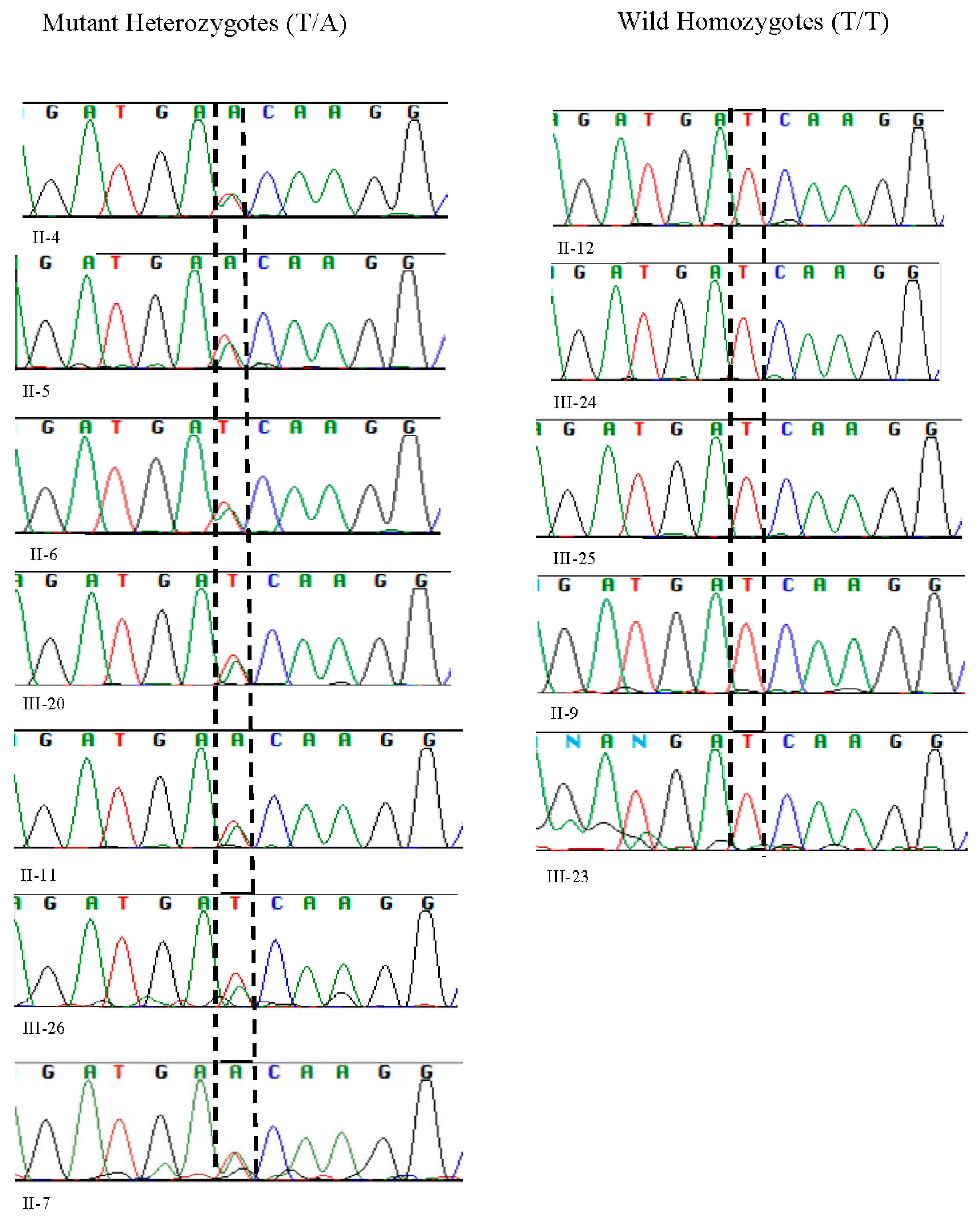

The sequencing results paralleled those obtained from RFLP analysis. Sanger sequencing revealed the presence of heterozygous alleles, with one allele being wild-type and the other mutant at position c.1097 T>A (Gene Bank accession number NM_003560.4 with T>A of ATC) (

Figure 2).

We reproduced the proband’s father (II-4) results and compared and matched his RFLP and sanger sequencing results with other heterozygotes of pathogenic variant (II-5, II-6, II-7, II-11, III-20, III-26) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

The Pakistani couple (II-5, II-6) seeking evaluation for INAD for their newborn child were heterozygous for pathogenic variant and so was their third child (III-20) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Among the five maternal siblings in generation II, including the mother of the presented child, four were identified as heterozygotes of pathogenic variant (II-4, II-6, II-7, II-11;

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Only one sister (II-9,

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) was homozygous for the wild-type allele. Despite carrying the mutant allele, all four siblings exhibited normal phenotypes and were free of any clinical manifestations of axonal dystrophy.

One maternal uncle and the mother (II-4 and II-6,

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) of the presented child, both of whom were heterozygous for pathogenic variant, entered consanguineous marriages with their first cousins who were also heterozygous for the pathogenic variant (II-3, and II-5;

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Notably, these two cousin marriages resulted in offsprings affected by INAD, indicating that the mutant allele had been inherited from both parents, which is consistent with autosomal recessive mode of transmission of this pathogenic variant. One maternal uncle of the presented child who was heterozygous for pathogenic variant (II-11), married a wild-type homozygous partner outside of the family, resulting in one offspring who is heterozygous for the pathogenic variant (III-26,

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This case underscores the impact of consanguinity on the inheritance of autosomal recessive conditions such as axonal dystrophy.

Discussion

We have characterized Pakistani kindred with a rare pathogenic variant in the PLA2G6 gene segregating with INAD with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. This pattern is characterized by a 25% risk of having an affected child in each pregnancy when both parents are heterozygous for the pathogenic variant and highlights the critical importance of genetic counseling for families with a history of autosomal recessive disorders in this part of the world where consanguineous marriages are common.

The uniform clinical presentation of INAD in the affected children within this family underscores the disorder's characteristic phenotype, which aligns with the clinical features described in other studies [

2,

12]. This consistency in symptomatology supports the notion of a recognizable and predictable clinical course for INAD, which can aid in early diagnosis.

The affected family's situation further illustrates the challenges faced in regions with limited access to genetic testing facilities. The tragic loss of three male children to INAD emphasizes the dire consequences of not having access to early genetic diagnosis and intervention. The fact that two children, despite being phenotypically healthy, were identified as heterozygous for pathogenic variant, highlights the potential for genetic screening to provide crucial information that can inform family planning and prevent future occurrences of the disorder by avoiding first-cousin marriages. Infantile Neuroaxonal Dystrophy is a very rare neurodegenerative disorder with no specific incidence data available for Pakistan. The absence of a patient registry for genetic diseases in Pakistan, including rare disorders like INAD, poses significant challenges for healthcare providers, researchers, and policymakers. The lack of comprehensive epidemiological data underscores the necessity for detailed research and data collection to understand the prevalence of such rare disorders in different regions in the country.

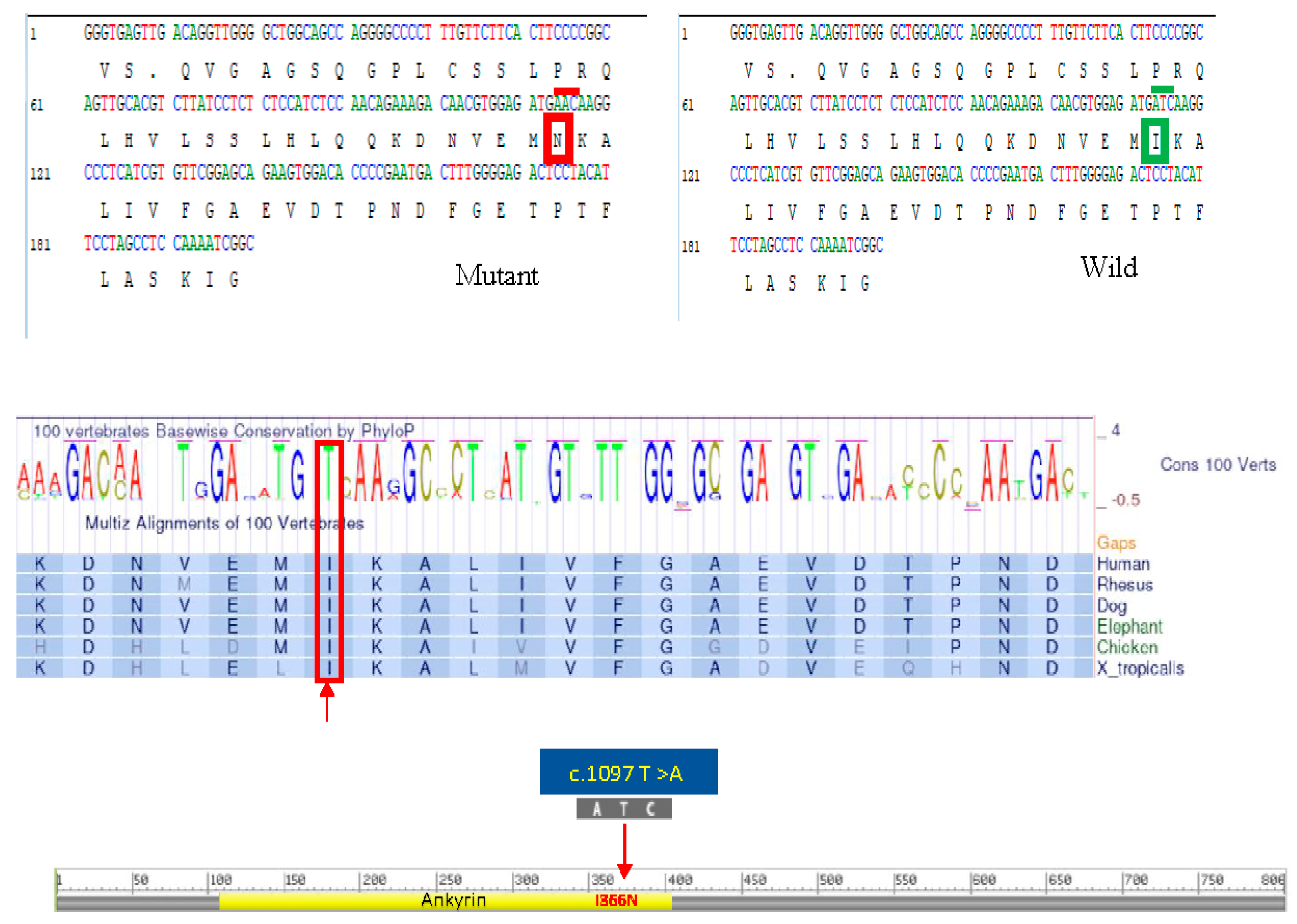

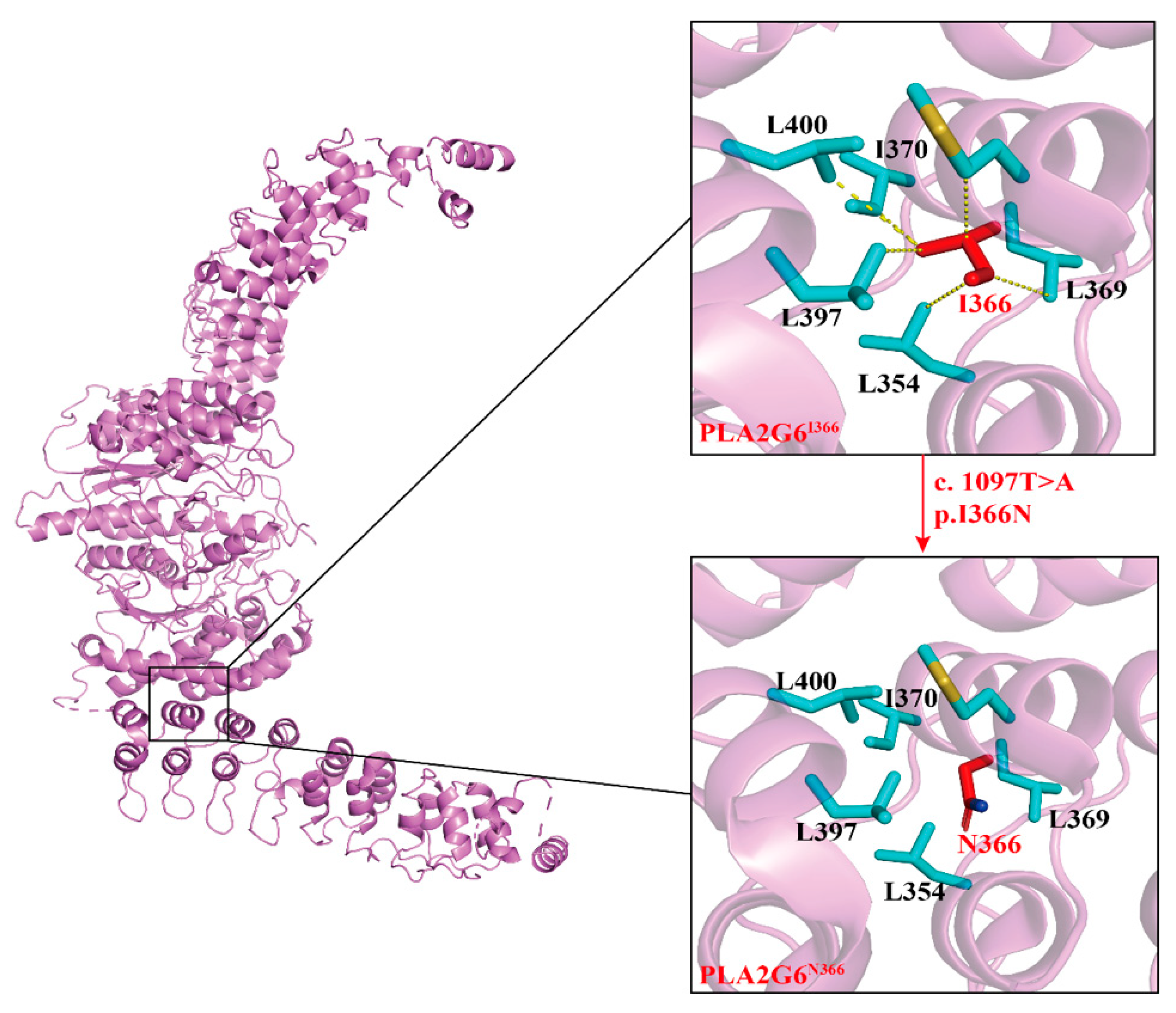

In our study, the single nucleotide substitution at c.1097 T>A produced a nonfunctional A2 phospholipase, an enzyme type that facilitates the liberation of fatty acids from phospholipids [

13,

14,

15]. The sequence of this enzyme is divided into three domains: an amino terminal, Ankyrin and catalytic domain [

16]. Ankyrins are present in a multitude of proteins and have evolved into an extremely precise structural framework for recognizing proteins [

17]. In various proteins, clusters of Ankyrins can align adjacent to each other, creating elongated linear formations. Within these formations, a hydrophobic core, comprising five conserved amino acids, maintains the cohesion of the helical repeats [

18]. While the specific amino acids may vary, the overall three-dimensional structure of the Ankyrin remains remarkably consistent [

19]. The altered hydrophobicity resulting from the Ile366Asn substitution may lead to misfolding or aggregation of the protein, impairing its function and contributing to cellular dysfunction. Isoleucine is highly conserved across species, the substitution of this amino acid with asparagine at codon 366 (Ile366Asn) in the

PLA2G6 gene can lead to detrimental effects. Dysregulated phospholipid metabolism can result in increased oxidative stress within neurons [

20,

21,

22]. Neuronal cells are highly susceptible to oxidative damage due to their high content of unsaturated fatty acids. Accumulation of oxidized phospholipids can lead to lipid peroxidation, generation of reactive oxygen species, and subsequent damage to cellular membranes, proteins, and DNA, ultimately contributing to neuronal dysfunction and death. Phospholipids are also critical for maintaining mitochondrial structure and function [

23]. Dysregulation of phospholipid metabolism may impair mitochondrial membrane integrity, disrupt electron transport chain activity, and compromise ATP production, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetic failure in neurons. Phospholipids also serve as precursors for signaling molecules involved in intracellular signaling pathways. Dysregulated phospholipid metabolism can disrupt the production of these signaling molecules, leading to aberrant cellular signaling and impaired neuronal function. This dysregulation may contribute to synaptic dysfunction, neurotransmitter imbalance, and altered neuronal excitability, ultimately leading to neurodegeneration [

24]. Cumulative damage resulting from disrupted phospholipid metabolism, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired neuronal signaling can ultimately lead to neuronal death. Neuronal loss contributes to the progressive neurodegeneration observed in affected individuals, resulting in the characteristic clinical features of the disorder, including movement abnormalities, cognitive decline, and neurologic dysfunction.

The identification of a novel mutation within this genetic region underscores the critical role of the PLA2G6 gene in natural neurological development. It also accentuates the significance of genetic screening for irreversible neurological disorders in families with a higher prevalence of cousin marriages, as commonly observed in Pakistani culture. Systematic genetic screening for known pathogenic variants facilitates early diagnosis and informed family planning decisions, potentially reducing the occurrence of genetic diseases in future generations. The identification of a novel pathogenic variant within the PLA2G6 gene broadened our comprehension of the genetic underpinnings of INAD. Furthermore, ongoing research into the molecular mechanisms governing INAD pathogenesis holds promise for identifying potential therapeutic targets conducive to intervention and treatment advancement.

Materials and Methods

1.1. Case Description

A Pakistani couple seeked medical advice at the Children’s hospital Multan, Pakistan for their newborn offspring (Presented Child: III-20;

Figure 5).

The couple (II-5, II-6;

Figure 5) had a cousin marriage and previously experienced the loss of two male children (III- 18, III-19;

Figure 5), both diagnosed having axonal dystrophy through clinical and neuroimaging evaluations. The family history revealed that a cousin (III-13,

Figure 5) of the presented child from his maternal line and living abroad also succumbed to a similar ailment. The cousin's parents (II-3 and II-4;

Figure 5) were also related by consanguinity. The medical records of this cousin, who, along with his parents, underwent genetic testing abroad, have been obtained. The records revealed that the cousin who later passed away was homozygous for the pathogenic variant at exon 8, position c.1097T>A of the

PLA2G6 gene and both of his parents were heterozygous for pathogenic variant. Since this variant had not been reported previously, it was considered of undetermined clinical significance and was not investigated further. To ascertain whether the newborn of the Pakistani couple had this condition and to assess whether this pathogenic variant was indeed the cause of INAD in the family, we reached out to all maternal uncles, aunts, their spouses, and children of the affected child. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

1.1. Clinical Data and Specimen Collection

The distribution of subjects by disease status, sample availability for genetic testing, and availability of genetic records is shown in

Supplementary Figure S1.

Of the 22 living members of the family showing in

Figure 5, we were able to collect saliva samples from 12 after obtaining written informed consent. Subject I-1 was too old and weak to give the sample. We couldn’t obtain consent for genetic testing from 8 subjects (II-8, II-10, III-14, III-15, III-16, III-17, III-21, III-22). The parents of the affected proband provided us with the genetic testing record of the affected proband (III-13) as well as their own genetic testing records (II-3, II-4), while only clinical records were available for affected deceased children who were residents of Pakistan (III-18 and III-19). Rest of the family members were inquired and clinically assessed by the physician.

1.1. Laboratory Testing

DNA extraction from saliva was performed using the prepIT.L2P; DNAgenoTeK kit. Primers (5’GCCGATTTTGGAGGCTAGG 3’; 5’ GGGTGAGTTGACAGGTTGG 3’) were designed to amplify the genomic region spanning from position 38129458 to 38129657 on the sense strand within exon 8 of the NM_003560.4 transcript, utilizing the genomic sequence of NC_000022.11 (Chromosome 22 Reference GRCh38.p14 Primary Assembly). The resultant 200 bp PCR product was confirmed through agarose gel for all samples. To discern the homozygous and heterozygous states at this locus, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was employed using the smart cut enzyme MboI (5’… GATC …3’; 3’…CTAG …5’). The sample of proband’s father (II-4) was used as a positive control as it had previously been sequenced for this pathogenic variant and identified as heterozygous for this pathogenic variant. The accuracy of the enzyme digestion outcomes was corroborated through Sanger sequencing and the sequencing results were analyzed using the sequencher software.

4.4. Bioinformatic Tools

4.4.1. Genomic Position and Protein Domain

4.4.2. Pathogenic Variant Annotation

4.4.3. Structural Modeling of the Pathogenic Variant

Structural modeling of the pathogenic variant was performed after deriving the basic structure from Protein Data Bank,

https://www.rcsb.org/) [

33]. The

PLA2G6 chain A structure was modeled on the crystal structure of

PLA2G6 (6AUN). The three-dimensional mutated structures on I366 residue were predicted by Swiss-model [

34] and the potential impact of the pathogenic variant was analyzed by PyMOL 2.5.4 (PyMOL Software, Inc., CA, USA). Hydrophobic interaction analysis was conducted with the measurement plugin. After obtaining the draft, Adobe Illustrator 2020CC was used for combining and annotating the images.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Table S1: Bioinformatic tools and their functional explanation. Supplementary Figure S1: Distribution of subjects by disease status, sample availability, and genetic testing. Supplementary Figure S2: Description of symbols used in pedigree.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Asma N.Cheema; Data curation: Asma N.Cheema; Formal analysis: Asma.N.Cheema, Ruyu.Shi, M. Ilyas Kamboh.; Funding acquisition: M.Ilyas Kamboh; Software: Asma N. Cheema, Ruyu Shi ; Supervision: M.Ilyas.Kamboh.; Writing original draft: Asma N.Cheema; Writing review and editing: all authors.

Funding

The study was supported by Research Development Funds by the University of Pittsburgh.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Board of University of Pittsburgh (STUDY23070032).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the family who volunteered to participate in this study. We acknowledge the services of two medical students, Umais Naveed Warraich from Rawalpindi Medical University, Pakistan and Shiza Naveed Warraich from Sahiwal Medical College, University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan to help us in samples collection and history taking of the family members.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, P.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, X.; Xiao, J. Follow-up study of 25 Chinese children with PLA 2G6-associated neurodegeneration. Eur j Neurol. 2013, 20, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuame, F.D.; Foskett, G.; Atwal, P.S.; Endemann, S.; Midei, M.; Milner, P.; Salih, M.A.; Hamad, M.; Al-Muhaizea, M.; Hashem, M.; Alkuraya, F.S. The natural history of infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwal, P.S.; Midei, M.; Adams, D.; Fay, A.; Heerinckx, F.; Milner, P. The infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy rating scale (INAD-RS). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth-Bencsik, R.; Balicza, P.; Varga, E.T.; Lengyel, A.; Rudas, G.; Gal, A.; Molnar, M.J. New insights of phospholipase A2 associated neurodegeneration phenotype based on the long-term follow-up of a large Hungarian family. Front Genet. 2021, 12, 628904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, D.; Dennis, E.A. Molecular basis of unique specificity and regulation of group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (PNPLA9) and its role in neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol & Therapeut 2023, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, T.; Lemire, G.; Kernohan, K.D.; Howley, H.E.; Adams, D.R.; Boycott, K.M. New diagnostic approaches for undiagnosed rare genetic diseases. Ann Rev Genom Hum G. 2020, 21, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Yuan, L.; Jankovic, J.; Deng, H. Phenotypic spectrum of neurodegeneration associated with pathogenic variants in the PLA2G6 gene (PLAN). Neurology. 2008, 70, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Luo, H.; Yuan, H.; Xie, K.; Yang, Y.; Huang, S.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y. PLA2G6 pathogenic variant underlies infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2006, 79, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Ling, C.; Du, K.; Li, R.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, W.; Jin, H. Novel PLA2G6 pathogenic variants in Chinese patients with pla2g6-associated neurodegeneration. Front Neurol. 2022, 13, 922528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Jafri, H.; Rashid, Y.; Ehsan, Y.; Bashir, S.; Ahmed, M. Cascade screening for beta-thalassemia in Pakistan: development, feasibility and acceptability of a decision support intervention for relatives. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022, 30, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, H.; Bertoli-Avella, A.M.; Skrahina, V.; Anjum, M.N.; Waheed, N.; Saeed, A.; Beetz, C.; Perez-Lopez, J.; Rocha, M.E.; Alawbathani, S.; Pereira, C. Genomic testing in 1019 individuals from 349 Pakistani families results in high diagnostic yield and clinical utility. NPJ Genom Med. 2020, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Luo, H.; Yuan, H.; Xie, K.; Yang, Y.; Huang, S.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y. Identification of a Novel Nonsense Pathogenic variant in PLA2G6 and Prenatal Diagnosis in a Chinese Family With Infantile Neuroaxonal Dystrophy. Front Neurol. 2022, 13, 904027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Nowatzke, W.; Ramanadham, S.; Turk, J. Human pancreatic islets express mRNA species encoding two distinct catalytically active isoforms of group VI phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) that arise from an exon-skipping mechanism of alternative splicing of the transcript from the iPLA2 gene on chromosome 22q13. 1. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 9607–9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A. Cellular regulation and proposed biological functions of group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in activated cells. Cell Signal. 2005, 17, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, C.C. Thematic Review Series: Phospholipases: Central Role in Lipid Signaling and Disease: Cytosolic phospholipase A2: physiological function and role in disease. J Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1386–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Ilies, M.A. The phospholipase A2 superfamily: structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and pathologic roles. Int J Molr Sci. 2023, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Zheng, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Song, Z.; Wang, J.; Deng, H.; Yuan, L. Identification of PLA2G6 variants in a Chinese patient with Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Neur Dis. 2023, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, B.; Parekh, N. Sequence and Structure-Based Analyses of Human Ankyrin Repeats. Molecules. 2022, 27, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Balbach, J. Folding and stability of ankyrin repeats control biological protein function. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malley, K.R.; Koroleva, O.; Miller, I.; Sanishvili, R.; Jenkins, C.M.; Gross, R.W.; Korolev, S. The structure of iPLA2β reveals dimeric active sites and suggests mechanisms of regulation and localization. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanadham, S.; Ali, T.; Ashley, J.W.; Bone, R.N.; Hancock, W.D.; Lei, X. Calcium-independent phospholipases A2 and their roles in biological processes and diseases. J Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1643–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.; Azcona, L.J.; Paisán-Ruiz, C. Pla2g6 deficiency in zebrafish leads to dopaminergic cell death, axonal degeneration, increased β-synuclein expression, and defects in brain functions and pathways. Mol Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 6734–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, K.J.; Castillo-Quan, J.I.; Bartolome, F.; Angelova, P.R.; Li, L.; Pope, S.; Cocheme, H.M.; Khan, S.; Asghari, S.; Bhatia, K.P.; Hardy, J. Loss of PLA2G6 leads to elevated mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Brain. 2015, 138, 1801–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, P.K.; Claesson, H.E.; Kennedy, B.P. Multiple splice variants of the human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 and their effect on enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 2699. [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Riley, G.R.; Jang, W.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Church, D.M.; ClinVar, D.M. Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nuclei Acids Res. 2014, 42, D980–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudmundsson, S.; Singer-Berk, M.; Watts, N.A.; Phu, W.; Goodrich, J.K.; Solomonson, M.; Genome Aggregation Database Consortium; Rehm, H.L.; MacArthur, D.G.; O'Donnell-Luria, A. Variant interpretation using population databases: Lessons from gnomAD. Hum Mutat. 2022, 43, 1012–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.L.; Kumar, P.; Hu, J.; Henikoff, S.; Schneider, G.; Ng, P.C. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, W452–W457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzhubei, I.A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V.E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature methods 2010, 7, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubach, M.; Maass, T.; Nazaretyan, L.; Röner, S.; Kircher, M. CADD v1. 7: using protein language models, regulatory CNNs and other nucleotide-level scores to improve genome-wide variant predictions. Nucleic Acids Res, 2024, 52, D1143–D1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, N.M.; Rothstein, J.H.; Pejaver, V.; Middha, S.; McDonnell, S.K.; Baheti, S.; Musolf, A.; Li, Q.; Holzinger, E.; Karyadi, D.; Cannon-Albright, L.A. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016, 99, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordai, H.; Torres, O.; Csepi, M.; Padányi, R.; Lukács, G.L.; Hegedűs, T. Analysis of AlphaMissense data in different protein groups and structural context. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Bittrich, S.; Chao, H.; Chen, L.; Craig, P.A.; Crichlow, G.V.; Dalenberg, K.; Duarte, J.M.; Dutta, S. RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB. org): delivery of experimentally-determined PDB structures alongside one million computed structure models of proteins from artificial intelligence/machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D488–D508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; Lepore, R. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).