1. Introduction

Ctenocephalides felis (cat flea) is the most abundant and cosmopolitan flea species parasitizing cats, dogs and opportunistically other mammals including humans [

1]. The insect is an obligatory hematophagous ectoparasite feeding with the blood of the host [

2].

Cat fleas are not only the most common ectoparasites of companion animals worldwide but also an increasingly recognized reservoir and potential vector of bacterial pathogens of veterinary and human concern [

3,

4]. Their cosmopolitan distribution and broad host range (cats, dogs, wildlife and humans) create opportunities for cross-species transmission of infectious agents. Historically, the public-health focus on

C. felis centered on classical vector-borne agents such as

Rickettsia felis and

Bartonella henselae [

4]. More recent molecular surveys, however, have revealed a far richer flea-associated microbiome, including enteric, skin-associated and opportunistic bacteria [

5,

6].

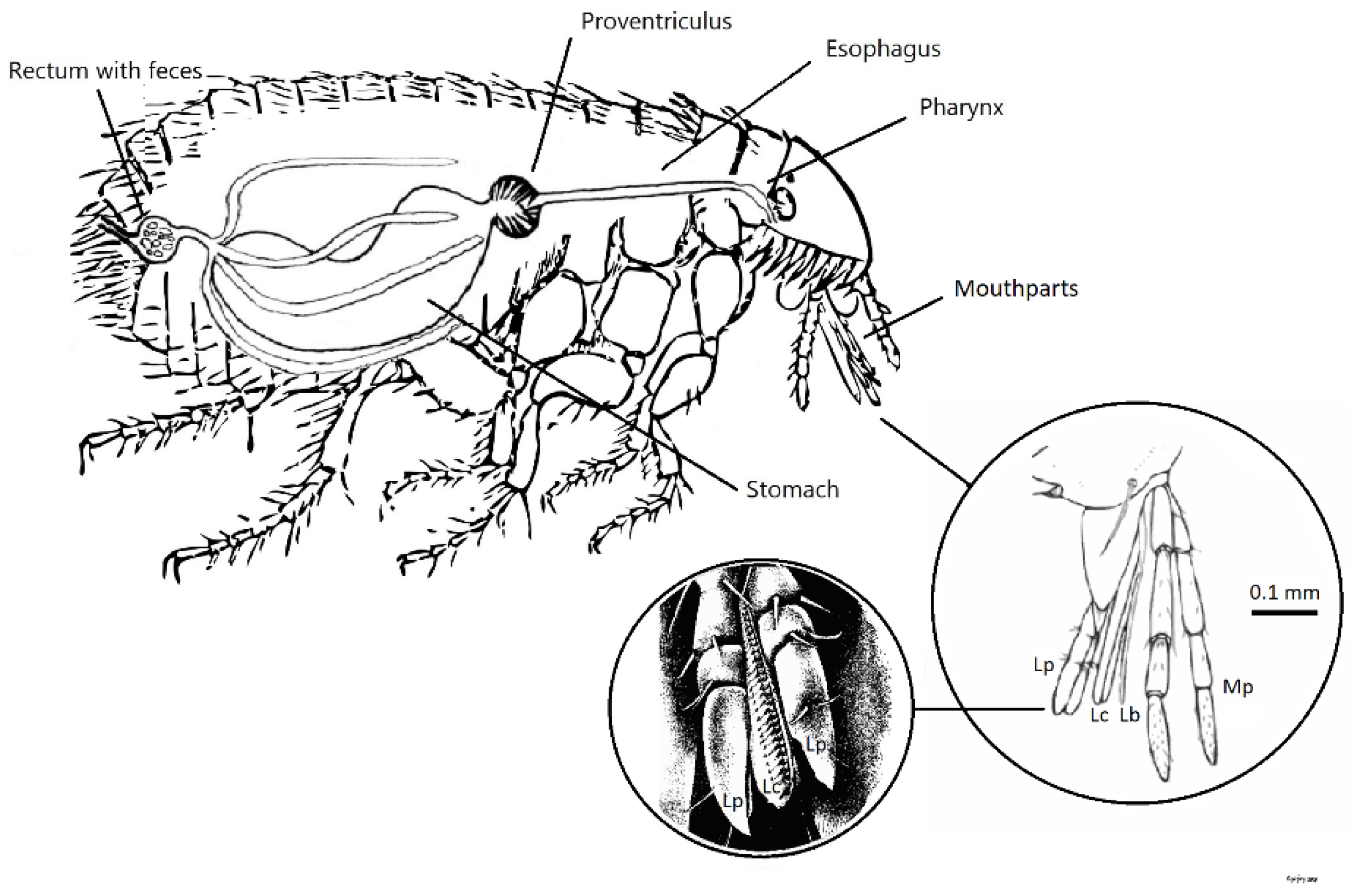

While most studies analyze whole insects, the head section is by far of particular interest. Head contains mouthparts, the anatomical interface that pierces human skin, ingests blood and injects saliva, therefore coming in direct contact with the dermis and bloodstream. Laciniae, a pair of hard saw-like cutting organs and epipharynx, a stubbing apparatus, are responsible for the perforation of the skin (Fig. 1). Together they form a dorsal food canal through which the flea sucks blood while the opposing surfaces of laciniae shape a separate ventral salivary canal that injects anticoagulant saliva into the wound [

7]. Despite this obvious relevance, systematic characterization of the bacterial communities found specifically in the flea head is scarce.

In this study, the bacterial flora of cat-flea heads is investigated for pathogenic species and the potential role of fleas to act as vectors of unconventional pathogens is discussed.

Figure 1.

Ctenocephalides felis schematic representation of mouthparts and digestive system. Lc: Laciniae, Lb: Labrum, Mp: Maxillary palps, Lp: Labial palps. Adapted from Dougas G. et al., Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6(1), 37; CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.

Ctenocephalides felis schematic representation of mouthparts and digestive system. Lc: Laciniae, Lb: Labrum, Mp: Maxillary palps, Lp: Labial palps. Adapted from Dougas G. et al., Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6(1), 37; CC BY 4.0.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

Fleas were collected from cats visiting local veterinary clinics in the region of Attica, Greece, along with animal-related data (sex, age, ownership status). The insects were preserved at room temperature for a maximum of 48 hours before dissection and DNA extraction. The genus and species of fleas were identified by standard anatomic keys [

7,

8] using stereo microscope under 10–40 X magnification (NIKON SMZ645, Nikon Instruments Inc., Surrey, UK).

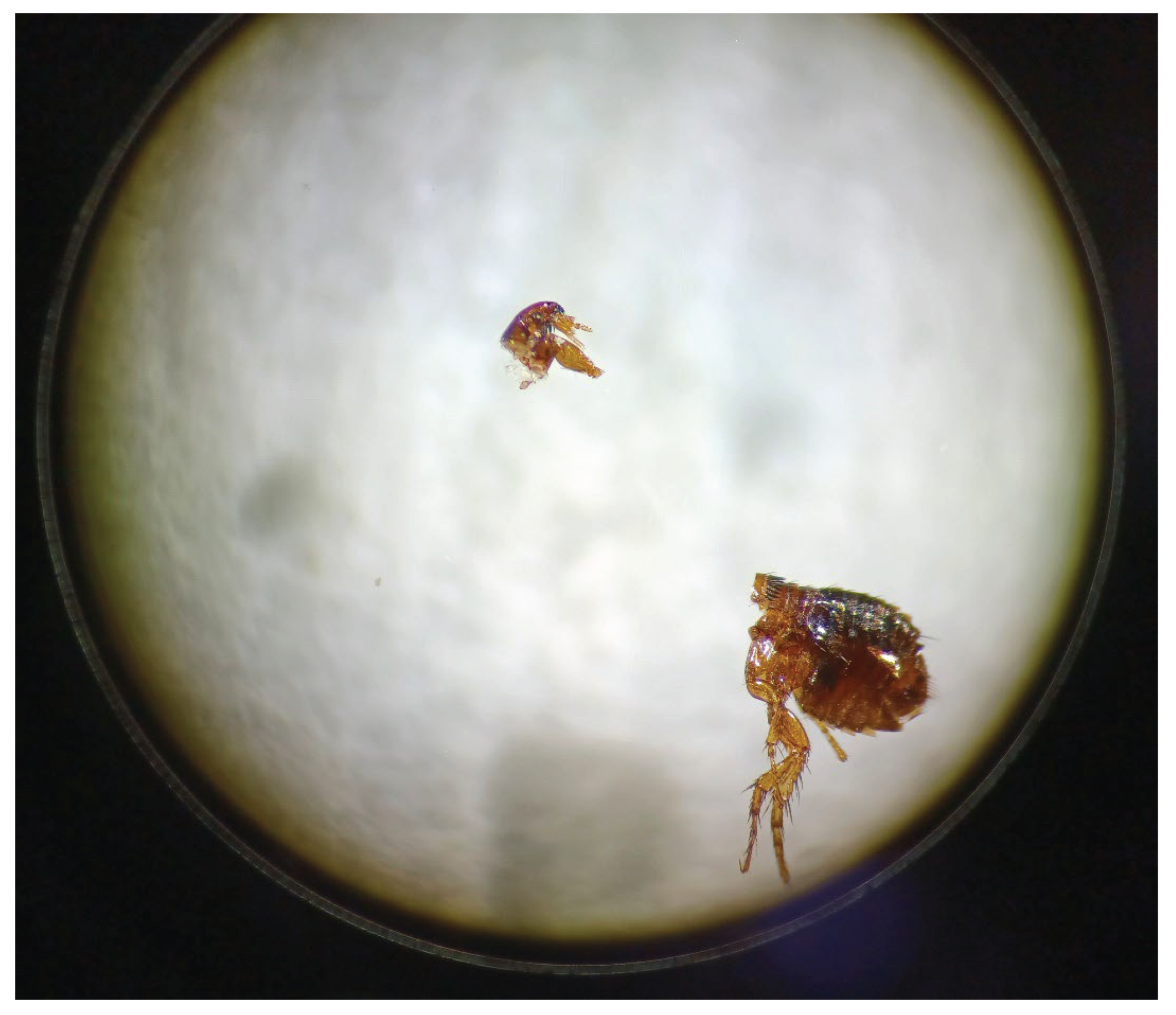

C. felis heads were separated with fine-tipped forceps and dissecting scalpel at 40 X magnification and pooled in groups by host-cat (flea-groups). (Fig. 2). The heads of each flea-group were thoroughly homogenized with a pestle and DNA was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All manipulations were performed under sterile conditions.

Figure 2.

Dissected head of a Ctenocephalides felis flea in stereo microscope (40 X magnification).

Figure 2.

Dissected head of a Ctenocephalides felis flea in stereo microscope (40 X magnification).

2.2. Molecular Investigation

DNA extracts were analyzed using a 16S metagenomics assay, employing the Ion 16S Metagenomics Kit on the PGM Ion Torrent platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sequencing data were processed with QIIME version 2, using the MicroSEQ v2013.1 and GreenGenes v13.5 16S rDNA reference databases for taxonomic classification. Only bacteria identified at species level were included in the analysis.

2.3. Clinical Relevance and Infection Dynamics

Pathogenic bacteria were those enlisted as infectious agents in the ICD-11 International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision [

9] or in the communicable diseases case definitions, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [

10]. The type of infection was categorized as blood stream infection (BSI) or skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) according to the ECDC case definitions and for those not covered by ECDC, according to available literature.

2.4. Assessment of Infection Potential

Flea-head microbiome was assessed for pathogens associated with bacteremia of unknown origin (BUO). According to ECDC, BUO (also called “primary” or “cryptogenic” bacteremia) is a primary BSI of unknown origin, not related to vascular-catheter infection with no identifiable source [

11]. The microbiome was cross examined with commonly cited BUO bacteria recovered from BSI when no infection source is obvious:

Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococci, β-haemolytic or Viridans-group Streptococci,

Enterococcus faecalis/faecium,

Escherichia coli,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Enterobacter cloacae complex,

Serratia marcescens,

Proteus mirabilis,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Acinetobacter baumannii,

Bacteroides fragilis group,

Clostridium perfringens,

Salmonella enterica,

Haemophilus influenzae [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

To further evaluate the potential role of fleas to transmission of BUO flea-head bacteria, the common epidemiological context of infection (hospital-acquired vs community-onset) was reviewed. Suspicion for flea implication further increased with community-dominant BUO agents, rather than with those cited as hospital-acquired.

3. Results

In total, 112 C. felis were collected from 30 cats. Host animals had a male-to-female ratio of 1.14:1, median age 18 months (IQR: 6-39), and were 87% stray. The examined fleas had a female-to-male ratio of 4.9:1. Flea-groups comprised a median of 3 insect heads per host cat (IQR: 2–4).

Molecular investigation of the flea-groups’ DNA extracts revealed 1578 bacterial species that belonged to 14 phyla, 168 families, and 511 genera. The bacterial species associated with human diseases were, in total, 119 (7.5%), corresponding to four phyla, 18 families, and 23 genera; of them, 83 (69.7%) were characterized as pathogenic according to ECDC, 28 (23.5%) according to ICD-11 whereas eight (6.7%) were classified as pathogens based on both sources. Among the identified pathogens, 74.8% were associated with both BSI and SSTI, 16.0% with BSI, and 9.2% with SSTI. Flea groups had a median of 3.5 (IQR: 1.25-6.00) pathogenic species and a minimum of one disease-related species per group. The standard flea-borne pathogens B. henselae and B. clarridgeiae were among the detected species. Pathogenic genera included Acinetobacter, Actinomyces, Aerococcus, Bacillus, Bartonella, Clostridium, Corynebacterium, Enterobacter, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Haemophilus, Micrococcus, Nocardia, Pasteurella, Propionibacterium, Proteus, Rickettsia, Salmonella, Serratia, Staphylococcus, Streptobacillus, Streptococcus and Streptomyces.

A detailed breakdown of the pathogenic bacteria detected in cat flea heads is presented in Table A1 (Appendix).

Of the 119 pathogenic species of flea-head microbiome, ten are well associated with BUO cases; three are community-dominant, four are both community-onset and hospital-acquired and three are solely associated with hospital infections (

Table 1). Most flea-groups (21; 70%) harbored at least one BUO species with a median of two species (IQR: 2.0, 3.0) per group.

Table 1.

The common epidemiological setting and clinical context of Bacteremia of Unknown Origin (BUO) associated with bacteria in the head section of Ctenocephalides felis (cat fleas).

Table 1.

The common epidemiological setting and clinical context of Bacteremia of Unknown Origin (BUO) associated with bacteria in the head section of Ctenocephalides felis (cat fleas).

| Genus species |

Common epidemiologic setting |

Typical clinical context |

| Acinetobacter baumannii |

Nosocomial-dominant |

Ventilator-associated pneumonia, ICU bacteraemia, wounds |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

Both |

CA & HA UTIs; endocarditis; line-related BSI |

| Enterococcus faecium |

Nosocomial-dominant |

VRE catheter- or line-associated BSI, post-op wound |

| Escherichia coli |

Both |

Uncomplicated CA-UTI; ESBL/VRE-unit BSIs |

| Haemophilus influenza |

Community-dominant |

CAP, COPD exacerbations, paediatric invasive disease |

| Proteus mirabilis |

Both |

CA pyelonephritis; crystalline CAUTI in long-term care |

| Salmonella enterica |

Community-dominant |

Food-borne enteritis, typhoid bacteraemia |

| Serratia marcescens |

Nosocomial-dominant |

NICU/ICU outbreaks, device & water-borne clusters |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

Both |

Skin/SSTI (CA); device/endovascular BSI (HA) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes |

Community-dominant |

Pharyngitis, cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis |

CA: Community-acquired

NICU / ICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit / Intensive Care Unit

HA: Hospital-acquired (nosocomial)

SSTI: Skin and Soft-Tissue Infection

UTI / CA-UTI / CAUTI: Urinary-tract infection / Community-acquired UTI / Catheter-associated UTI

CAP: Community-acquired Pneumonia

BSI: Blood-stream infection

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

VRE: Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus

Post-op: Post-operative

ESBL: Extended-spectrum β-lactamase |

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the head section of C. felis harbors a diverse array of bacterial species, including a substantial proportion classified as human pathogens under ICD-11 and ECDC definitions. Notably, nearly 75% of these pathogens were associated with both bloodstream and skin/soft tissue infections, underscoring the potential for clinically significant exposure via the flea's piercing mouthparts.

The identification of the classical flea-borne agents such as

Bartonella species supports existing literature [

3,

4] and confirms the validity of flea head sampling as a method for vector surveillance. Furthermore, the detection of

B. henselae and

B. clarridgeiae in flea heads—rather than in whole bodies or feces of fleas—represents a finding that could support hypotheses of mechanical or salivary transmission during feeding. While vector competence has not been established for these bacteria via flea bite, their presence in the anatomical structures of the head strengthens the argument for a transmission potential. The detection of the rodent-specific

B. grahamii in cat fleas agrees with previous reports [

21], supporting a wider vector range.

The detection, however, of a much broader panel of potential pathogens, including agents linked to Bacteremia of Unknown Origin, adds novel insight. Among the 119 pathogenic species identified, ten are widely cited in the literature as causative agents of BUO—bacteremia without a clear source of infection. The presence of these bacteria in flea heads may represent a hypothetical but plausible transmission mechanism, especially given their compatibility with a cutaneous or hematogenous route.

Of particular interest is the epidemiological context of these BUO-associated bacteria. While species such as

E. faecium,

S. marcescens, and

A. baumannii are primarily nosocomial pathogens [

22], others such as

Streptococcus pyogenes,

H. influenzae, and

S. enterica are more commonly associated with community-acquired infections [

23], making their presence in cat flea heads particularly relevant from a One Health perspective.

A major consideration is biofilm formation that facilitates bacterial perseverance under adverse conditions. Almost all species identified in this study, including BUO agents, have documented biofilm-forming capabilities [

24]. Only a few species, specifically

Rickettsia australis and

Streptobacillus moniliformis, are confirmed non-biofilm builders [

25]. Biofilm-forming bacteria may persist in the flea's mouthparts or salivary glands, increasing the transmission likelihood.

It is important to recognize the study's limitations. Detection of bacterial DNA does not equate to viable organisms or vector capacity. Moreover, contamination during sampling, particularly from the host's skin microbiota, cannot be entirely ruled out despite rigorous dissection protocols. Nevertheless, several of the species identified—such as

S. enterica,

H. influenzae, and

S. pyogenes—are not typical skin flora and may indicate bloodmeal-derived colonization [

23].

Our findings are consistent with previous observations that fleas harbor a complex microbiome [

5,

6]. However, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to comprehensively characterize the microbial flora of the flea head alone using high-throughput metagenomics, and to relate these findings specifically to BUO-associated pathogens.

Future studies should prioritize the isolation of viable bacteria from dissected mouthparts and salivary glands to assess transmission risk. Approaches combining culture-based techniques and metagenomic data with experimental infection models would allow for a more complete characterization of viable and infectious organisms.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the head microbiome of cat flea contains a wide range of human pathogens, including established and emerging species associated with bloodstream and skin or soft tissue infections. A subset of the identified bacteria are agents of community-onset bacteremias of unknown origin. While causality cannot be inferred from detection alone, the anatomical proximity to host entry sites, combined with the known pathophysiology of these bacteria, warrants further investigation into the role of cat fleas as potential vectors of non-classical pathogens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.; methodology, G.D. and J.P.; validation, J. P., S.B. and E.P; formal analysis, G.D.; investigation, S.B.; resources, J.P., S.B. and E.P; data curation, G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, J. P., S.B., E.P and A.T.; visualization, G.D.; supervision, J. P. and A.T.; project administration, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table 1.

Pathogenic bacterial species (n=119) identified in the heads of Ctenocephalides felis (cat fleas) collected from cats, organized in 30 flea-groups by host cat (n=30), according to ICD-11 classification of diseases and the communicable diseases classification (ECDC, 2018).

Table 1.

Pathogenic bacterial species (n=119) identified in the heads of Ctenocephalides felis (cat fleas) collected from cats, organized in 30 flea-groups by host cat (n=30), according to ICD-11 classification of diseases and the communicable diseases classification (ECDC, 2018).

| Genus |

species |

Number of flea-groups |

% |

Pathogenic by ICD-11 |

Pathogenic by ECDC (2018) |

| Acinetobacter |

baumannii |

15 |

50.0 |

Yes |

Yes |

| |

baylyi |

5 |

16.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

beijerinckii |

4 |

13.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

calcoaceticus |

8 |

26.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

guillouiae |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

gyllenbergii |

4 |

13.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

johnsonii |

23 |

76.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

junii |

15 |

50.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

lwoffii |

24 |

80.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

radioresistens |

5 |

16.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

schindleri |

15 |

50.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

soli |

5 |

16.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

towneri |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

ursingii |

13 |

43.3 |

No |

Yes |

| Actinomyces |

dentalis |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

graevenitzii |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

No |

| |

naeslundii |

16 |

53.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

odontolyticus |

6 |

20.0 |

Yes |

No |

| |

radingae |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

viscosus |

6 |

20.0 |

Yes |

No |

| Aerococcus |

urinaeequi |

10 |

33.3 |

No |

Yes |

| Bacillus |

acidiproducens |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

badius |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

cecembensis |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

cereus |

3 |

10.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

coagulans |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

decisifrondis |

9 |

30.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

eiseniae |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

firmus |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

funiculus |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

graminis |

6 |

20.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

humi |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

lentus |

4 |

13.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

nealsonii |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

niacini |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

taeanensis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

thermoamylovorans |

4 |

13.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

thermocopriae |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

thermolactis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

vietnamensis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

weihenstephanensis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| Bartonella |

clarridgeiae |

6 |

20.0 |

Yes |

No |

| |

grahamii |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

No |

| |

henselae |

3 |

10.0 |

Yes |

No |

| Clostridium |

perfringens |

11 |

36.7 |

Yes |

No |

| Corynebacterium |

accolens |

6 |

20.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

afermentans |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

ammoniagenes |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

amycolatum |

8 |

26.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

appendicis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

aquatimens |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

aquilae |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

aurimucosum |

3 |

10.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

auriscanis |

4 |

13.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

bovis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

callunae |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

coyleae |

15 |

50.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

deserti |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

doosanense |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

durum |

7 |

23.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

efficiens |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

flavescens |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

genitalium |

3 |

10.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

glucuronolyticum |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

glutamicum |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

halotolerans |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

jeikeium |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

kroppenstedtii |

11 |

36.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

maris |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

massiliense |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

mastitidis |

6 |

20.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

matruchotii |

5 |

16.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

minutissimum |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

mucifaciens |

14 |

46.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

mustelae |

3 |

10.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

pilbarense |

9 |

30.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

pyruviciproducens |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

resistens |

3 |

10.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

simulans |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

singulare |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

stationis |

4 |

13.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

suicordis |

5 |

16.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

terpenotabidum |

6 |

20.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

tuberculostearicum |

24 |

80.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

tuscaniense |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

ureicelerivorans |

17 |

56.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

variabile |

9 |

30.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

vitaeruminis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

xerosis |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| Enterobacter |

asburiae |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

hormaechei |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

kobei |

3 |

10.0 |

Yes |

No |

| Enterococcus |

faecalis |

9 |

30.0 |

Yes |

Yes |

| |

faecium |

6 |

20.0 |

Yes |

Yes |

| |

gallinarum |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

No |

| |

hirae |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

mundtii |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

No |

| Escherichia |

coli |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

Yes |

| Haemophilus |

influenzae |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

Yes |

| Micrococcus |

flavus |

3 |

10.0 |

No |

Yes |

| |

lylae |

12 |

40.0 |

No |

Yes |

| Nocardia |

takedensis |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

transvalensis |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

vinacea |

3 |

10.0 |

Yes |

No |

| Pasteurella |

canis |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| |

multocida |

11 |

36.7 |

Yes |

No |

| |

stomatis |

7 |

23.3 |

Yes |

No |

| Propionibacterium |

acidifaciens |

1 |

3.3 |

No |

Yes |

| |

acnes |

30 |

100.0 |

Yes |

Yes |

| |

granulosum |

17 |

56.7 |

No |

Yes |

| |

propionicum |

2 |

6.7 |

No |

Yes |

| Proteus |

mirabilis |

8 |

26.7 |

Yes |

No |

| Rickettsia |

australis |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| Salmonella |

enterica |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

Yes |

| Serratia |

marcescens |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

|

| Staphylococcus |

aureus |

2 |

6.7 |

Yes |

Yes |

| Streptobacillus |

moniliformis |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

| Streptococcus |

pyogenes |

4 |

13.3 |

Yes |

No |

| Streptomyces |

cacaoi |

1 |

3.3 |

Yes |

No |

References

- Moore, C. O.; André, M. R.; Šlapeta, J.; Breitschwerdt, E. B. Vector biology of the cat flea Ctenocephalides felis. Trends Parasitol. 2024, 40, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otranto, D. Arthropod-borne pathogens of dogs and cats: From pathways and times of transmission to disease control. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 251, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L. D.; Macaluso, K. R. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Grado, L. A.; Lopez Salazar, L. M.; Trinidad, L. A.; Cook, J. L.; Bechelli, J. Molecular detection of Rickettsia felis in fleas of companion animals in East Texas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 107, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, N.; Armstrong, P. M. Microbiota of arthropods: Diversity and complexity. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougas, G.; Tsakris, A.; Beleri, S.; Patsoula, E.; Linou, M.; Billinis, C.; Papaparaskevas, J. Molecular evidence of a broad range of pathogenic bacteria in Ctenocephalides spp.: Should we re-examine the role of fleas in the transmission of pathogens? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, R. E. The skeletal anatomy of fleas (Siphonaptera)

. Smithson. Misc. Collect. 1947, 104, 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, G. H. E.; Rothschild, M. An illustrated catalogue of the Rothschild Collection of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the British Museum (Natural History), Vol. 1, Tungidae and Pulicidae; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th rev.). WHO: Geneva, 2019.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. European Union case definitions for communicable diseases for reporting under Decision No 1082/2013/EU and Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/945. ECDC: Stockholm, 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018D0945 (accessed on 01 May 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Protocol for the surveillance of healthcare-associated infections and prevention indicators in European intensive care units (Version 2.3). ECDC: Stockholm, 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/protocol-surveillance-healthcare-associated-infections-and-prevention-indicators (accessed on 04 May 2025).

- Albert, M. J.; Bulach, D.; Alfouzan, W.; Uddin, M. F.; Shamsuzzaman, S. M.; et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella bloodstream infection in Kuwait: Clinical and microbiological characteristics. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, G.; Leung, C.; Cheong, J. W.; Franklin, R.; et al. Paediatric invasive Haemophilus influenzae in Queensland, Australia, 2002–2011: Young Indigenous children remain at highest risk. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Z.; Du, J.; Jiang, H. Rising drug resistance among Gram-negative pathogens in bloodstream infections: A multicentre study in Ulanhot, Inner Mongolia (2017–2021). Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e940686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D. R.; Labate, L.; Tutino, S.; Baldi, F.; Russo, C.; Robba, C.; Ball, L.; Dettori, S.; Marchese, A.; Dentone, C.; Magnasco, L.; Crea, F.; Willison, E.; Briano, F.; Battaglini, D.; … Bassetti, M. Enterococcal bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A case series. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C. L.; Anderson, M. T.; Mobley, H. L. T.; Bachman, M. A. Pathogenesis of Gram-negative bacteraemia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00234–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, F.; Geffers, C.; Behnke, M.; Gastmeier, P. ICU mortality following ICU-acquired primary bloodstream infections according to the type of pathogen: A prospective cohort study in 937 German ICUs (2006–2015). PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0194210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shargian, L.; Paul, M.; Nachshon, T.; Rahav, G.; et al. Outcomes of neutropenic haemato-oncological patients with viridans group streptococci bloodstream infection based on penicillin susceptibility. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Itoh, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Kurai, H. Clinical features of Clostridium bacteraemia in cancer patients: A case-series review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouggari, Y.; Lelubre, C.; Lali, S. E.; Cherifi, S. Epidemiology and outcome of anaerobic bacteraemia in a tertiary hospital. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 105, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Helps, C.; Tasker, S.; Newbury, H.; Wall, R. Pathogens in fleas collected from cats and dogs: distribution and prevalence in the UK. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner-Lastinger, L. M.; Abner, S.; Edwards, J. R.; Kallen, A. J.; Karlsson, M.; Magill, S. S.; … Dudeck, M. A. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with adult healthcare-associated infections: Summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2015–2017. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, L. J.; Lewis, D.; Griffiths, M. Community-acquired bloodstream infections: Epidemiology and clinical patterns. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S. A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R. C.; Gilbert, P. Comparative biofilm formation and dispersion among clinical pathogens. Microbiology 2022, 168, 001101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).