1. Introduction

Despite much emphasis on construction safety, the reduction in accident rates has plateaued in recent years. This condition exists all over the world, including Hong Kong. Errors and violations are two major forms of human failure [

1]. Their key is intention: violations refer to people not following the rules intentionally whereas errors are not intentional [

2]. The concept of violations attracted much attention after the occurrence of the Chernobyl nuclear plant disaster that resulted from human actions and deliberate deviations from written rules and instructions (violations) rather than errors of judgement [

3]. Violations are more specifically related to safety rules and procedures since safety violations occur because rules exist [

4]. In contrast, safety compliance is explained as general safety behaviour in Hayes et al. [

5].

The factors affecting safety violations have been investigated to understand why violations happen. However, the causes of safety violations are inconclusive from the literature as there is still little consensus on what variables cause violations [

6]. The complexity of reality is depicted well by the concept of “socio-technical systems” based on the interactive influences of work relations and technological factors [

7]. Despite this complexity, some studies have attempted to categorise the factors affecting safety violations more systematically, and the factors range from micro (individual), meso (group) and macro (organisational) (e.g., [

5,

6,

8]).

Safety violations are much less obvious than other risk behaviours and the effects are also more complex and still far from well-established in previous studies. Their effects are unclear for the following reasons: (1) there is not a well-established link with unwanted outcomes, (2) violations do not always lead to unwanted outcomes; and (3) not all violations are wrong [

6]. Some studies have applied the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) for explaining different violation behaviours such as road violations [

9,

10,

11] and drinking problems [

12,

13].

1.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

Social psychologists originally developed the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) to predict and explain human behaviour in specific contexts [

14]. The TPB was extended from the TRA, which assumes people have full volitional control over behaviour by including control beliefs and perceived behavioural control [

15]. According to the TPB [

14], intention is the most proximal predictor of human behaviour which refers to the willingness of people to perform a specific behaviour. Intention is affected by three cognitive determinants (attitude, norms and perceived behaviour control). Attitude can be understood as the value of that behaviour. Norms refer to how closely others think about that behaviour (subjective norms) and whether they would engage in it (descriptive norms). The original TPB only includes subjective norms. Some recent studies, such as Fugas, Silva and Meliá [

16], examine both aspects of norms of coworkers and supervisors separately. Perceived behavioural control refers to people’s perceived ability to perform. Haslam et al. [

17] illustrate that workers do not always have complete volitional control of their safety behaviours as there are interactions among work teams, workplace, materials, and equipment. The TPB has been widely adopted in various research fields in recent years, such as the studies related to the construction industry, e.g., an integrated training approach to first aid [

18]. Although the TPB has been well examined, it has not been adapted to provide a lens for explaining safety violations for Hong Kong construction workers.

1.2. Perceived Quality of Safety Rules and Procedures

Also, rules are not always good and applied well in every context [

19]. Cox and Cheyne [

20] suggest that safety level is affected by the extent to which workers perceive safety rules and procedures. Perceived quality of safety rules and procedures refers to how workers think about the safety rules and procedures, i.e., whether the objectives are clear and the applications are appropriate.

1.3. High Reliability Organising (HRO)

Harvey et al. [

21] advocate that construction organisations can become more resilient by incorporating employee-level with respect to the “Adaptive” age of safety. The study aligns with the HRO perspective analysed by Xu et al. [

22] that construction companies should look into current weaknesses of safety training while improving and developing a mindful safety culture to become high-reliability organisations. HRO refers to the organisation’s ability to anticipate and control unexpected safety events [

23]. There are five principles of HRO. The first three principles, i.e., preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify and sensitivity to operations, can be categorised as the principles of anticipation, which focuses on the prevention of disruptive unexpected events, whereas mindful attention shifts to practices of containment, i.e., commitment to resilience and deference to expertise when unexpected events continue to develop [

23]. The HRO was originated to explain other high-risk industries. Harvey et al. [

24] discuss barriers and opportunities of applying HRO and resilience engineering in construction and urge such application under the current adaptive safety age. Therefore, The HRO concept can be viewed as the distal, organisational-level factor affecting safety violations of Hong Kong construction workers.

This research aims to fill the existing research gaps. Due to the limited number of studies on safety violations among construction workers in Hong Kong, this research aims to provide insight into the current phenomenon of safety violations. Examining the causes of safety violations would therefore be the first research objective. In addition to examining the research framework, another research objective is to explore the dynamics of safety violations and construction workers in Hong Kong in depth. Workers’ open views need to be understood to achieve this objective. By adopting a mixed-methods strategy, the findings substantiate the adaptation of the TPB in this context, which examines different levels of factors affecting construction workers’ safety violations, ranging from micro to meso and macro factors. The significance of intention, perceived behavioural control, attitude, and HRO was identified. The interview also revealed the workforce dynamics, current safety training weaknesses, institutional issues, and some unique phenomena in the Hong Kong construction industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Model

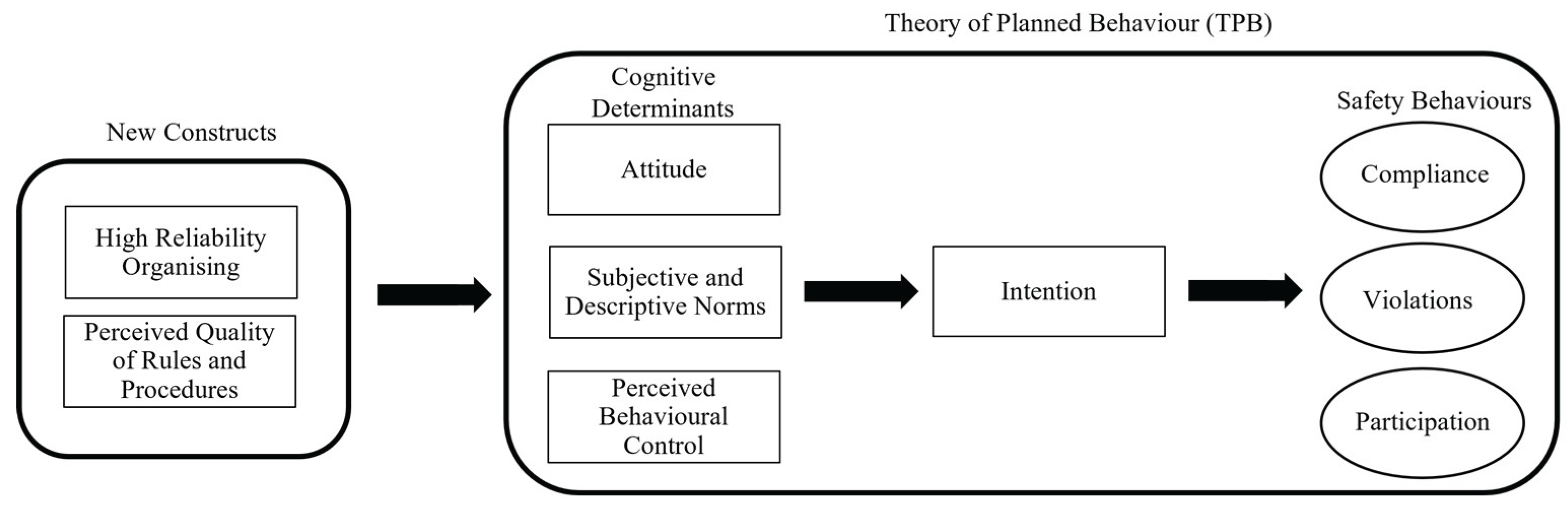

This study uses socio-technical system thinking to discuss the root causes of the current condition from micro to macro levels. Based on the literature review, it is reasonable to suggest that after considering the unique context and careful interpretation of the findings, the TPB can be developed as a clear framework for understanding safety violations of Hong Kong construction workers. The original TPB has been adapted by incorporating (1) descriptive norms with subjective norms, (2) perceived quality of safety rules and procedures, and (3) HRO in the research model. This study also examines safety compliance and safety participation. The research model and the hypotheses developed are shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1 respectively.

2.2. Mixed Methods Strategy

The research problem determines the choice of a research design [

25]. A mixed methods strategy, consisting of quantitative and qualitative inquiry strategies, was adopted to achieve the research objectives. For instance, Alper and Karsh [

6] recommend using multiple methods for understanding safety violations since it is simple to count them but difficult to analyse their causes via observations. For the quantitative approach, the hypotheses were developed based on the adapted TPB model and then tested through a questionnaire survey. Statistical analysis was used to examine the relationships of the variables in the research model and provide generalised findings.

After completing the questionnaire survey, interviews were conducted to obtain the benefit of the qualitative strategy. The qualitative approach helps consider all possible variables, their degree of influence, and the combination effects of those variables [

26], understand complex issues, explain linkages in theories and models [

27]. Rhodes [

28] also urges using a qualitative strategy for questioning and complementing dominant scientific constructions in the study of risk behaviour. The interviews disclose the construction workers’ views openly. The interview results aid interpretation of the questionnaire results and provide a rich context for understanding the current phenomenon of safety violations of Hong Kong construction workers.

2.3. Data Collection Method

The questionnaire survey took 20-30 minutes to complete. The measurement items adopted the seven-point Likert style as Ajzen [

29] and Francis et al. [

30] suggest it for the TPB questionnaires, and most TPB studies adopt this scale. The variables’ measures were adapted from the existing literature to fit the context of the Hong Kong construction industry. 23 nos. of the pilot survey were conducted, and several minor changes were made.

Table 2 summarises the measures of variables. Demographic variables were developed from Barrientos-Gutierrez et al. [

31], which include gender, age, race, education, religiosity, marital status, living with children, job nature, working level, and working location. Different construction companies were invited to participate in the main survey. Questionnaires were distributed to the respondents for completion at the training centres. Random sampling was adopted to obtain the data. A total of 795 questionnaires were received, with 365 valid and complete responses for analysing the safety violations of the construction workers in Hong Kong.

After analysing the quantitative results, 37 semi-structured interviews were conducted, each lasting 20-30 minutes. Several open-ended questions were asked during the interviews, allowing respondents to express their views on relevant issues and ideas freely. The respondents were first invited to introduce themselves, including their trade, work experience, and how they work with others. Options were provided for them to facilitate brainstorming and guide them with a framework for sharing their opinions on safety performance: (a) elder workers are better; (b) young workers are better; (c) not much difference; and (d) unable to tell. They were then asked to comment on the questionnaire results. After the respondents were encouraged to speak out, the researcher invited them to elaborate further on their opinions, provide reasons with examples.

The focus is on several major awareness perspectives that have been raised in recent years. First, the issue of an aging workforce highlights the importance of investigating various aspects of workers, including their types, work styles, and why they work in such a way. Second, the current nature and methods of safety promotion, and what factors affect safety compliance, could be meaningful for understanding the problems of violations. All quotes were translated as the workers stated them in non-standard English. NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software, was used to conduct content analysis for the interview scripts.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results and Analysis

Major respondents of the questionnaire survey worked for main contractors (49.3%) and subcontractors (40.9%). Most (94.6%) worked at construction sites, and only 5.4% worked in offices, including site offices. 93.9% of the respondents were male, and only 6.1% were female. Over half of them (54.0%) were within the age group of 25-34 and 35-44, whereas about one-third (35.5%) were within the age group of 45-54 and 55 and over, representing elder construction practitioners. The remaining respondents (10.5%) were in the youngest age group of 18-24. The education levels of the respondents were mainly secondary school level (53.9%) and above secondary school level (26.2%). More than two-thirds of them (69.0%) were married, and 64.8% lived with their children. Chinese (84.3%) was the main race, followed by Nepalese (12.4%), and they constituted the major proportion (95.7%).

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to calculate reliability and conduct factor analysis. Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) was used to carry out Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were assessed. Reliability is the level that the questionnaire produces stable and consistent results where validity refers to how well the questionnaire measures what is purported to measure [

35]. All the items reflected acceptable reliability that their Cronbach’s alpha is higher than the cut-off value of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978, as cited in [

36], pp. 709) with the exception of the alpha value of safety participation (SP) was 0.689 so SP was excluded from further analyses. Factor analysis helps understand the structure of a set of variables [

36]. Principal components analysis (PCA) was adopted for each construct in this study to reduce a large set of variables to a smaller set [

37].

SEM was then carried out, and there are two components within a model: the measurement model prescribes which measured variables are indicators of a latent variable (factor), whereas the structural model defines the relationship among latent variables [

38]. Although SEM can anlayse direct and indirect relationships among latent and observed variables simultaneously [

39], Anderson and Gerbing [

40] advocate a two-step approach to model testing. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), model fit, and convergent validity of each construct were analysed first. The model fit, and discriminant validity of the overall measurement model were then analysed. After that, the structural model was tested. In terms of model fit, global fit measures are used to assess if the theoretical model adequately fits the sample data. Model modification is required for individual constructs if the model cannot achieve the acceptable fitness indices [

39]. First, the items were removed to improve the model fit if the standard estimate of the items was less than the required 0.50 level. Second, the modification indices (MI) for the covariances were referred to covary error terms that are part of the same factor, and the largest modification indices were addressed first [

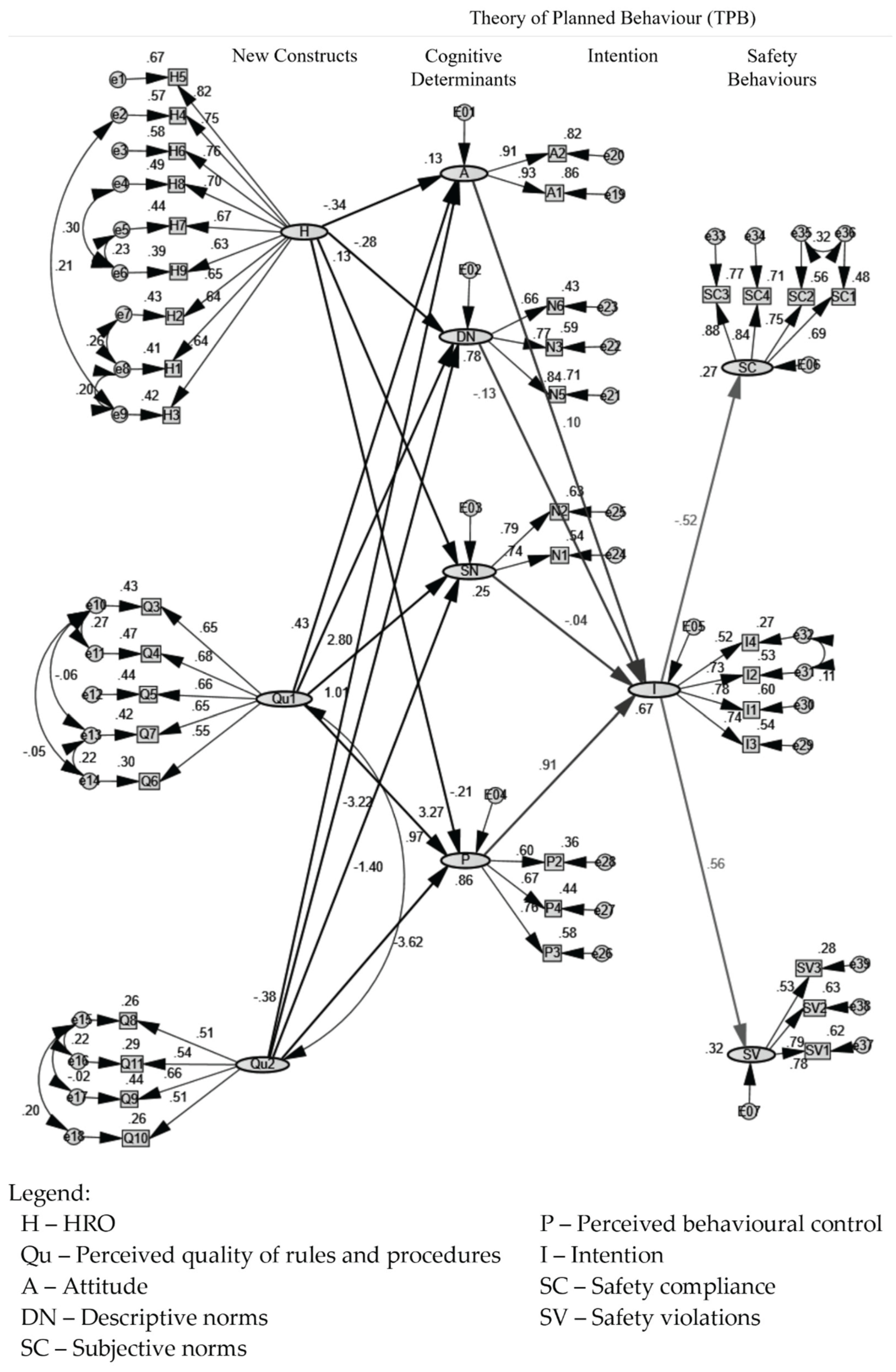

41]. Similar to the measurement model, the fitness of the structural model needed to be examined first. The modified structural model fitness indices were: Chi-square/df=2.687 <3, p-value = 0.000, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI)=.819, Comparative Fit Index (CFI)=.836, RMSEA (Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation)=.068. The χ2/degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) showed acceptable fit, and TLI, CFI, and RMSEA achieved marginal fit, so the construct was not modified further.

Figure 2 shows the results of standardised estimates and model fit indices for the modified structural model.

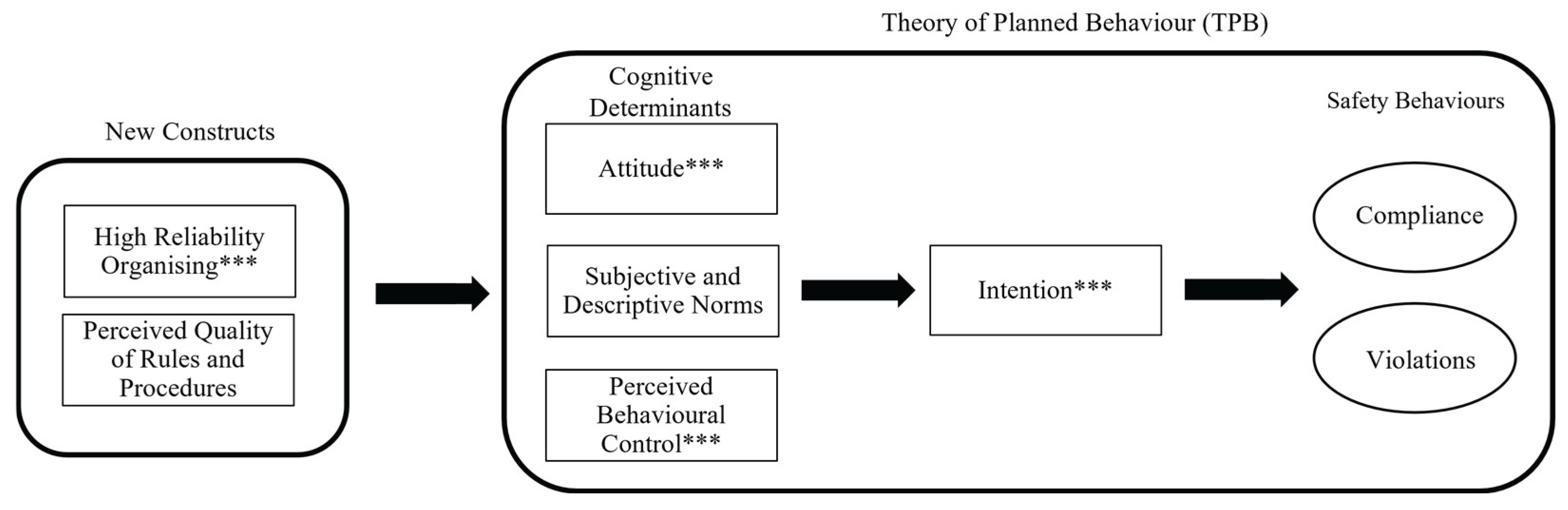

Table 3 summarises the results of the tested hypotheses, and

Figure 3 highlights the significant results of the questionnaire survey.

3.2. Qualitative Results and Analysis

In Hong Kong, people describe older workers with more experience as Sih-Fus (師傅). However, there are no well-established definitions for Sih-Fus (師傅). It is just a generic term, and people tend to use working experience for classification. In order to establish a rapport with the respondents, workers who have been working for more than ten years were called Sih-Fus (師傅)through the interviews. Those Sih-Fus (師傅) generally accepted this title, and young workers also did not have any adverse comments on this classification. The interviews revealed deep insight into Sih-Fus (師傅) and young workers’ self-perceived safety performance. The distinctive features of Sih-Fus (師傅) and young workers can be described in terms of ability and adaptability. Interestingly, the weaknesses of Sih-Fus (師傅) can be considered as the strengths of young workers. For instance, Sih-Fus (師傅) have more experience, so they are more able to spot the dangers at sites, whereas Sih-Fus (師傅) might also be over-confident in their own ability.

Young workers think that Sih-Fus (師傅) deserve respect for being a “master” for young workers since they have better workmanship and much experience in safety and all aspects of their work. However, most Sih-Fus (師傅) do not acknowledge such responsibility. In reality, they focus on productivity. Their low safety engagement in training young workers may be explained by their perceived age similarity with others [

42]. Sih-Fus (師傅) may not develop a close relationship with young workers easily due to their generation gap. This phenomenon may result from the daily wage system and high mobility of Hong Kong construction industry workers.

Regarding who is important in promoting safety, a number of workers recognised the importance of all stakeholders, including themselves. Some middle managers suggested that the management of construction companies has started to recognise the importance of safety engagement. Although managers and supervisors expect changes in workers’ attitudes, they do not engage effectively in promoting the desired changes [

43]. In addition, there is low safety engagement of construction workers. The findings can be explained by the top-down approach suggested by Rasmussen [

44] that the construction industry comprises multiple levels. Regarding policy establishment, the rules and procedures are set by the top level, i.e., the head office. Lower levels then execute the rules and procedures. Sih-Fus of subcontractors usually are the “followers” of those rules and procedures. There are no bottom-up mechanisms for reflecting their views and communicating their difficulties with upper levels. Eventually, they have little communication about safety with their coworkers and supervisors. Most of them think that they only have to comply with the rules and procedures. The interviewees also recognised that more safety training opportunities should be provided at construction sites to address safety issues. The current training content also does not consider the uniqueness of every work trade and dynamic changes at sites.

The finding of perceived behavioural control being the most significant factor affecting construction workers’ intention on safety compliance was reinforced by the interviews that over half of the respondents highlighted work progress and working environment as the key factors affecting safety compliance. Sih-Fus (師傅) believed that they had sufficient safety knowledge and knew how to work safely. However, they were too pressurized to complete the work quickly, so they sometimes decided to work without following the safety rules and procedures. The working environment can also be interpreted as an element of perceived behavioural control. First, it relates to the physical working environment in which sufficient space is required to carry out the safety measures. Second, the safety standard varies among different main contractors. The standard would be higher for government jobs. Third, monitoring levels affect safety compliance.

Attitude also significantly affected the intention, but its effect was much weaker. Nevertheless, over one-third of the respondents reaffirmed this finding. When compared to the term “attitude”, “self-awareness” was much more frequently mentioned by many respondents. Self-awareness reflects the concept of mindfulness in HRO. Mindfulness refers to HRO having “a mental orientation and a rich awareness of discriminatory detail, i.e., when people act, they are aware of context, of ways in that details differ, and of deviations from their expectations” [

23] (pp. 88 and 32).

Surprisingly, some of them admitted that they have low safety awareness. They would be more aware of safety if they and other workers had accidents before or were afraid of being punished. Frontline workers generally have lower safety awareness. They may only concentrate on their own task. For instance, the workers who wash site vehicles may ignore lifting work. Self-awareness depends on workers’ perception of whether safety or “earning money” is important. The relevant importance of their own lives may be related to their personality. Using personal protective equipment as an example, workers are the ones who choose to use it or not. It may be difficult to ensure that they use it. If workers have high safety awareness, they would review the environment and work only if it is safe. In their opinions, their self-awareness is affected by other factors, such as the mindset of “catch up on progress”, inspection (punishment) and monetary reward.

Some Sih-Fus (師傅) and young workers suggested that self-awareness, which refers to safety and communication awareness, is more important than norms since safety compliance depends on whether you are willing to get injured yourself. Nevertheless, some respondents suggested that norms is still important. Norms represent the overall atmosphere in the working environment and it is created by people working there. The respondents’ feedback indicated that Sih-Fus (師傅) may be a bad model for young workers. For instance, young workers may listen to their instructions during work. If Sih-Fus (師傅) ask them to cut corners to catch up on the progress, they may simply ignore the safety rules.

In line with the research model, the quality of safety rules and procedures was explained by several respondents as a meso factor. The objectives of the safety rules and procedures seem unclear to some Sih-Fus (師傅). Both Sih-Fus (師傅) and young workers shared their difficulties in complying with different sets of safety rules established by different main contractors and clients. The intention in safety compliance is adversely affected by inconsistent safety standard of construction companies. The inconsistent safety standard would adversely affect the construction workers’ self-awareness in return.

Respondents also shared a number of macro factors affecting construction workers’ safety compliance. They are institutional contributors that include (1) subcontracting and salary system; and (2) competitive tendering. These macro factors may not directly affect safety compliance but negatively impact meso and micro factors aforesaid. The high mobility resulting from adopting the subcontracting system adversely affects the grasp of safety knowledge and incentives to teach young workers. In addition to the daily rate, the Cau-Ga (炒家) system commonly exists in plastering, tiling and scaffolding. The nature is similar to the subcontracting system but on a smaller scale. Subcontractors further “subcontract” part of the works, such as by floor or area, to Cau-Gas (炒家), which are comprised of gangs of experienced Sih-Fus (師傅). Interestingly, those Sih-Fus (師傅) are usually daily workers. At the same time, they complete those urgent tasks for an extra bonus. This type of incentive is used for projects with tight schedules. Consequently, Cau-Gas (炒家) would focus more on productivity, so they seldom interact with inexperienced workers. The high popularity of Cau-Gas (炒家) in construction projects also reaffirms the reality that site progress is always the top priority. The respondents also suggested that all stakeholders, including government, developers, main contractors, subcontractors, and workers, should be involved in construction safety from the outset, from the procurement method (competitive tendering) to safety culture in the industry.

4. Discussion

In the research model, H1a and H1b were confirmed. Mediocre coefficients were found which supported the stipulation in the TPB that intention is the most proximal predictor of human behaviours. Construction workers would be the key to safety as they have control over their safety behaviours. Although previous studies have different views on the human role in accident causation, the finding substantiates the importance of workers themselves for safety compliance and violations and highlights human factors.

There are three proximal factors and two distal factors affecting workers’ intention of safety violations in this adapted TPB model. The factors affecting workers’ safety compliance range from micro, meso to macro factors [

45]. The three proximal factors can be viewed as micro factors, whereas the two distal factors can be viewed as meso factors. They might result from the institutional contributors pinpointed by the interviewees that can be viewed as macro factors. The underlying institutional issues composing the current phenomenon of Hong Kong construction workers’ safety violations can be explained in terms of the “socio-technical systems” view. Considering the definition by Noy et al. [

7] in this context, the workers’ safety compliance is shaped by the interactive influences of work relations (socio subsystem) and technology (technical subsystem). Therefore, the research model provides a framework for examining safety violations, but the existence of other possible factors and their interactions should also be considered.

Among the three cognitive determinants in the TPB, perceived behavioural control was found to be the strongest factor affecting intention. H4 was confirmed to support the development of the TPB from the TRA with perceived behavioural control incorporated. Behaviours are not always under people’s complete control, i.e., safety violations in this research. In terms of ability, it refers to the workers’ own workmanship and experience, i.e., how the workers can complete the work with/without complying with safety rules and procedures. The workers’ perceived ability would also be affected by the external influence.

Regarding attitude, H2 was confirmed but the effect of attitude was much weaker than perceived behavioural control. Attitude refers to how workers value safety, i.e., whether they would place safety over other concerns, such as site progress. Many interviewees referred to attitude as self-awareness. Workers who are more aware of safety during work would be more willing to comply with safety rules and procedures. Self-awareness of individual workers reflects how well construction companies apply the concept of mindfulness in HRO.

The original TPB only examines the subjective norms on intention and recent studies further develop the theory by including descriptive norms. H3 was refuted as insignificant negative impacts of both subjective and descriptive norms on intention were found. On one hand, the findings may be explained by the identity level discussed in Choi and Lee [

46]. When the workers do not identify with the reference group, i.e., their coworkers and supervisors, group norms do not influence their safety behaviours. On the other hand, their self-awareness (own attitude) would be more important than coworkers and supervisors’ behaviour and pressure from them. Norms may indirectly affect intention via perceived behavioural control and attitude. Since the behaviours and pressure on safety violations may not be obvious, the mindset of “catch up on progress” may be accumulated and instilled in the workers’ mind from their coworkers and supervisors’ daily behaviours and social pressure.

H6a and H6c were confirmed. HRO affects the perceived behavioural control and attitude significantly. The result sheds light on the importance of HRO since it originates in the proximal factors that consequently affect the intention of safety compliance. High reliability organisations refer to construction companies that are able to maintain their sites at low accident rates. To achieve such a target, construction companies need to demonstrate the five principles of anticipation and containment of unexpected events. The findings align with the proposition in Rowlinson et al. [

47] that the maturity of organisations is one of the aspects where new initiatives need to be developed in the Hong Kong construction industry. H6b was refuted. Nevertheless, a significant negative impact was found in HRO on descriptive norms. This may be explained by the rationale of HRO that it does not refer to strict safety compliance but requires a sense of reflectiveness for ongoing improvement on safety rules and procedures.

Instead of strict compliance, HROs can be viewed as “Model 2” of safety rules management that blame culture should not be maintained for safety violations and a translation process and adaption to any situation is required [

48]. Heedfulness of the surrounding environment is important for managing uncontrollable risk in HROs and such heedfulness may cause violations of safety rules [

49]. As suggested by Gudela and Weichbrodt [

50], in addition to a mindful culture, construction companies should carefully assess their safety rules and procedures since they affect the stability and flexibility of organisational processes for being HROs successfully. In Hong Kong, there are prescriptive and performance-based safety legislation that contractors need to comply with and employ proactive safety management approaches to satisfy different stakeholders’ requirements simultaneously [

51]. The dichotomy does not fit well for HRO.

Regarding perceived quality of safety rules and procedures, H5 was refuted. Factor Q2 and Q1 have contradictory results; only the former showed a significant impact as hypothesised. Although it did not demonstrate consistent results, the interviewees’ responses provided some insights regarding the current condition. Safety rules and procedures may be adequate for professional management, but they are not for workers due to the subcontracting system. The rules’ level should be applied according to users’ circumstances and capabilities [

48]. However, the head office of construction companies establishes the safety guidelines, rules and procedures and then site offices are requested to implement them in Hong Kong. The workers are usually not engaged in safety management.

In addition to improving current safety trainings that adopt classroom and traditional paper-based examination, the interviews support the proposition of Shen et al. [

52] that workers, in particular Sih-Fus (師傅), who are more likely to be influenced by entrenched working habits, should be repeatedly reminded about safety on the job even construction companies with a positive safety climate. Weaknesses in safety management should also be addressed. For instance, using retrospective data, e.g., accident rate, for assessing safety performance is passive. An active approach, such as behavioural monitoring of workers’ actions for providing immediate feedback, would be desirable. The interventions will be effective only if the safety management system is well-developed [

43].

5. Conclusions

This research has thoroughly explored workers’ current context and safety violations in the Hong Kong construction industry. The distinctive characteristics of Sih-Fus (師傅) and Cau-Gas (炒家) were identified from the interviews, and they further intensify the issue of safety violations. This research substantiates the use of the TPB in this context, which examines different levels of factors affecting construction workers’ safety violations, ranging from micro, meso, and macro factors. In particular, this study has innovatively applied the HRO measurement instrument to Hong Kong construction organisations. This study applied socio-technical system thinking. Construction workers’ safety violations and compliance are affected by their network of work relationships and the work process and techniques [

7]. The interviewees highlighted the institutional contributions that explain the poor performance at the work face level and the weakness of management in not being mindful of these issues.

It should be acknowledged that every research has its own limitations. For the quantitative results of this research, safety compliance and violations were self-reported by the construction workers. To relieve the social desirability issue that may exist in their responses, anonymity and confidentiality were emphasised and clearly explained to the respondents. For the qualitative results, the researcher may have bias during organising and analysing the data, so the qualitative data analysis computer software NVivo was used to conduct the content analysis more systematically.

Due to the complex dimensionality of safety violations, an ethnographic study is suggested to observe and explore construction workers’ social interactions and behaviours during their daily work. The other factors identified from the interviews and the outcomes of safety behaviours, such as injury rate, absenteeism, etc. can be further incorporated into the research model to provide a comprehensive insight into the safety behaviours. When more time is allowed, a longitudinal study can be conducted to examine the changes in safety behaviours and the factors’ impact over time. The interviewees strongly emphasised the issue of the workers’ low safety engagement. The construct of safety engagement can also be examined to reveal different perspectives of safety behaviours in future research.

Although the research focuses on construction workers, all stakeholders should be responsible for the workers’ safety behaviours. This is the essence of HRO that the whole construction organisation should be mindful. Safety compliance of Hong Kong construction workers should be viewed as an institutional issue and consists of numerous interactions as a whole so all stakeholders should get involved. It should be acknowledged that recurring problems exist throughout the whole system. Safety engagement is an essential next step for safety management in the Hong Kong construction industry.

Policy-makers can develop relevant interventions based on the relationships established in the findings: workers’ perceived behavioural control and attitude affect their intention, which in turn improves their safety compliance. Perceived behavioural control can be explained from different perspectives. In addition to construction workers’ own perceived ability, the interviewees highlighted the impact of external influences (work progress and working environment) on perceived behavioural control. All stakeholders have their responsibilities for improving work progress and working environment. For example, clients and consultants should establish a reasonable construction period and minimise late design changes during the construction stage to alleviate the pressure on work progress. Meanwhile, main contractors should provide adequate working space and have effective project planning and resourcing to ensure smooth project execution.

Training should be tailor-made and provided for the construction workers to tally with distinctive features exhibited by Sih-Fus (師傅) and by young workers. For example, the training for young workers can be more focused on enhancing their capability, i.e., the rationale and significance of the safety rules and procedures, whereas Sih-Fus (師傅) should be reminded about the potential risks and the importance of self-awareness emphasised. Existing habits of Sih-Fus (師傅) should be changed and new habits (i.e., good practice) should be developed in the long term since habits represent Sih-Fus’ (師傅) beliefs of what behaviours are correct.

The institutional contributors reveal the reality that the government, developers, consultants, main contractors and subcontractors should collaborate. For instance, the government can provide subsidies to subcontractors for providing training opportunities and subsidise the income of their workers attending training courses. Although the research focuses on construction workers, all the stakeholders involved should have a role in the workers’ safety behaviours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C.T.; methodology, W.C.T.; validity tests, W.C.T.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C.T.; writing—reviewing and editing, S.A.M.; supervision, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Hong Kong Human Research Ethics Committee, Reference number: EA1609017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are unavailable for access and unsuitable for posting due to confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any support which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AMOS |

Analysis of a Moment Structures |

| CFI |

Comparative Fit Index |

| CMIN/DF |

χ2/degrees of freedom |

| HRO |

High Reliability Organising |

| MI |

Modification Indices |

| PCA |

Principal Components Analysis |

| RMSEA |

Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modelling |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package of the Social Sciences |

| TLI |

Tucker-Lewis Index |

| TPB |

Theory of Planned Behaviour |

| TRA |

Theory of Reasoned Action |

References

- Reason, J. (1990). Human error. Cambridge University Press.

- Hudson, P. T., Verschuur, W. L. G., Parker, D., Lawton, R., & van der Graaf, G. (1998). Bending the rules: Managing violation in the workplace. Research Gate. http://www.eimicrosites.org/heartsandminds/userfiles/file/MRB/MRB%20PDF%20bending%20the%20rules.pdf.

- Reason, J. (1988, June). Errors and violations: The lessons of Chernobyl [Paper Presentation]. The Human Factors and Power Plants, 1988 IEEE Fourth Conference. Monterey, CA. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, R. (1998). Not working to rule: Understanding procedural violations at work. Safety Science, 28(2), 77-95. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B. E., Perander, J., Smecko, T., & Trask, J. (1998). Measuring perceptions of workplace safety: Development and validation of the work safety scale. Journal of Safety Research, 29(3), 145-161. [CrossRef]

- Alper, S. J., & Karsh, B. T. (2009). A systematic review of safety violations in industry. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 41(4), 739-754. [CrossRef]

- Noy, Y. I., Hettinger, L. J., Dainoff, M. J., Carayon, P., Leveson, N. G., Robertson, M. M., & Courtney, T. K. (2015). Editorial: Emerging issues in sociotechnical systems thinking and workplace safety. Ergonomics, 58(4), 543-547. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D. A., Jacobs, R., & Landy, F. (1995). High-reliability process industries: Individual, micro, and macro organizational influences on safety performance. Journal of Safety Research, 26(3), 131-149. [CrossRef]

- Parker, D., Manstead, A. S., Stradling, S. G., & Reason, J. T. (1992). Determinants of intention to commit driving violations. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 24(2), 117-131. [CrossRef]

- Free, R. (1994). The role of procedural violations in railway accidents [Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Manchester]. http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.519412.

- Dı́az, E. M. (2002). Theory of planned behavior and pedestrians’ intentions to violate traffic regulations. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 5(3), 169-175. [CrossRef]

- Marcoux, B. C., & Shope, J. T. (1997). Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to adolescent use and misuse of alcohol. Health Education Research, 12(3), 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Huchting, K., Lac, A., & LaBrie, J. W. (2008). An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to sorority alcohol consumption. Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 538–551. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. [CrossRef]

- Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S., & Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Fugas, C. S., Silva, S. A., & Meliá, J. L. (2012). Another look at safety climate and safety behavior: Deepening the cognitive and social mediator mechanisms. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 45, 468-477. [CrossRef]

- Haslam, R. A., Hide, S. A., Gibb, A. G., Gyi, D. E., Pavitt, T., Atkinson, S., & Duff, A. R. (2005). Contributing factors in construction accidents. Applied Ergonomics, 36(4), 401-415. [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H. (2004). First aid and preventive safety training: The case for an integrated approach. In S. Rowlinson (Ed.), Construction Safety Management Systems (pp. 305-323). Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. (2008). The human contribution: unsafe acts, accidents and heroic recoveries. Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Cox, S., & Cheyne, A. J. (2000). Assessing safety culture in offshore environments. Safety Science, 34, 111-129. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, E. J., Waterson, P., & Dainty, A. R. J. (2016). Towards an alternative approach to safety in construction. In P. Waterson, E. M. Hubbard, & R. Sims (Eds.), Contemporary Ergonomics and Human Factors 2016 (pp. 20-24). Taylor and Francis.

- Xu, J., Duryan, M., & Smyth, H. (2021). Digitalisation for Occupational Health and Safety in Construction: A Path to High Reliability Organising?. Proceedings of the CIB W099 & W123 Annual International Conference. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10134169/3/Xu_W099TG59_2021_paper_22.pdf.

- Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Harvey, E. J., Waterson, P., & Dainty, A. R. J. (2019). Applying HRO and resilience engineering to construction: Barriers and opportunities. Safety Science, 117, 523-533. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

- Malone, E. K., & Issa, R. R. (2012). Work-life balance and organizational commitment of women in the US construction industry. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education & Practice, 139(2), 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Rhodes, T. (1997). Risk theory in epidemic times: Sex, drugs and the social organisation of ‘risk behaviour’. Sociology of Health & Illness, 19(2), 208-227. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2015). Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. University of Massachusetts Amherst. http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf.

- Francis, J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A. E., Grimshaw, J. M., Foy, R., Kaner, E. F. S., Smith, L. & Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour: A manual for health services researchers. Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne. http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/1735.

- Barrientos-Gutierrez, T., Gimeno, D., Mangione, T. W., Harrist, R. B., & Amick, B. C. (2007). Drinking social norms and drinking behaviours: A multilevel analysis of 137 workgroups in 16 worksites. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 64(9), 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2006.031765. [CrossRef]

- Health and Safety Executive. (1995). Improving compliance with safety procedures – Reducing industrial violations. http://www.hse.gov.uk/humanfactors/topics/improvecompliance.pdf.

- Fogarty, G. J., & Shaw, A. (2010). Safety climate and the Theory of Planned Behavior: Towards the prediction of unsafe behavior. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(5), 1455-1459. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. A., & Hu, X. (2013). How leaders differentially motivate safety compliance and safety participation: The role of monitoring, inspiring, and learning. Safety Science, 60, 196-202. [CrossRef]

- Phelan, C., & Wren, J. (2016). Exploring reliability in academic assessment. https://chfasoa.uni.edu/reliabilityandvalidity.htm.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Dancey, C. P., & Reidy, J. (2011). Statistics without maths for psychology (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Field, A. (2000). Structural Equation Modelling. http://www.statisticshell.com/docs/sem.pdf.

- Crockett, S. A. (2012). A five-step guide to conducting SEM analysis in counseling research. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 3(1), 30-47. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423. [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J. (2018). Confirmatory factor analysis. http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/index.php?title=Confirmatory_Factor_Analysis.

- Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2007). Engaging the aging workforce: The relationship between perceived age similarity, satisfaction with coworkers, and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1542–1556. [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, S. (2018, June 25-27). Worker engagement on construction sites – Time for a new Look [Paper Presentation]. The 16th Engineering Project Organization Conference, Brijuni, Croatia.

- Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Safety Science, 27(2-3), 183-213. [CrossRef]

- Campbell Institute. (2014). Risk perception: Theories, strategies, and next steps. http://www.nsc.org/CambpellInstituteandAwardDocuments/WP-Risk%20Preception.pdf.

- Choi, B., & Lee, S. (2016). How social norms influence construction workers’ safety behavior: A social identity perspective. In J. L. Perdomo-Rivera, A. Gonzáles-Quevedo, C. L. del Puerto, F. Maldonado-Fortunet, & O. I. Molina-Bas (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2016 Construction Research Congress (pp. 2851-2860). American Society of Civil Engineers. [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, S., Yip, B., & Poon, S. W. (2008). Safety initiative effectiveness in Hong Kong: One size does not fit all. Construction Industry Institute, Hong Kong. [CrossRef]

- Hale, A. R., Borys, D., & Else, D. (2012). Management of safety rules and procedures – A review of the literature. Institution of Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.iosh.co.uk/~/media/Documents/Books%20and%20resources/Published%20research/Management_of_safety_rules_and_procedures_Literature_review.ashx.

- Iszatt-White, M. (2007). Catching them at it: An ethnography of rule violation. Ethnography, 8(4), 445-465. [CrossRef]

- Gudela, G., & Weichbrodt, J. (2013). Why regulators should stay away from safety culture and stick to rules instead. In C. Bieder & M. Bourrier (Eds.), Trapping into safety rules: How desirable or avoidable is proceduralization? (pp. 225-240). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Ju, C., & Rowlinson, S. (2014). Institutional determinants of construction safety management strategies of contractors in Hong Kong. Construction Management and Economics, 32(7-8), 725-736. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Ju, C., Koh, T. Y., Rowlinson, S., & Bridge, A. J. (2017). The impact of transformational leadership on safety climate and individual safety behavior on construction sites. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(1), 45. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).