1. Introduction

In fishes, the skin is a compact, non-keratinized living organ that covers their entire external body surface, including the head, fins and even the eyes. It serves as the organism’s primary defence against harmful biological, chemical and physical factors, while simultaneously preserving water, solutes and nutrients within the organism [1,2,3]. Like other vertebrates, the skin of fishes exhibits a highly conserved structure, comprising the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis [3]. The epidermis, the outermost layer of fish skin, is composed of keratocytes and mucous cells that secrete a continuous, adherent mucus layer containing a diverse range of immune-related substances such as agglutinins, immunoglobulins, C-reactive proteins and other antimicrobial peptides [3,4,5]. Besides providing multifaceted protection against pathogens, the mucus layer also supports functions like respiration, microbiota maintenance and particle entrapment. In turn, keratocytes act as physical barriers against harmful environmental features, exhibiting phagocytic activity and containing high levels of peroxidase and other immune response factors [3,6,7]. The outer layer of dermis is comprised by loose connective tissue, housing blood vessels, nerve cells, chromatophores, iridophores and peripheral nerve cells. The inner dermis is composed of dense connective tissue of tightly packed collagen fibres and specialized structures such as scales, which together enhance the skin’s puncture resistance. The hypodermis is situated beneath the dermal layer and above the musculature. It is predominantly occupied by adipocytes and small number of vascular and neural tissues, chromatophores and leucophores [2,3].

The heightened vulnerability to injuries in aquatic habitats has led fishes to evolve faster and more efficient healing mechanisms compared to terrestrial vertebrates [3,8]. Consequently, the wound healing in fishes does not involve the initial blood-clot formation phase but it begins with rapid re-epithelialization by migrating keratocytes from surrounding undamaged tissue, followed by inflammation, granulation tissue formation and wound remodeling [3,9]. In fishes, prevention of the blood and other extracellular fluids loss after injury infliction is achieved through the initiation of vasoconstriction and fibrin aggregation forming clot-like structures. Available studies have revealed that this process is accompanied by up-regulation of genes involved in epidermal repair and hemostasis, like integrins, fibronectin and genes related to eicosanoid metabolism [3,10]. In general, the rate of wound healing in fish primarily depends on the species, as well as the type and size of the wound; however, water temperature, stress level, age and nutritional status are also important factors [3,11]. In thermophilic and temperate fish species, wound bed re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation became evident as early as 2 days post-wounding (dpw), and depending on wound type and size, the damaged skin can be completely regenerated within a month. In turn, the re-epithelialization and granulation tissue development in cold-water species typically commence later, often between 10 and 42 dpw, with the entire tissue regeneration process extending up to 100 dpw [3].

Typically, skin injuries in fish are categorized into mechanical and ulcers-like wounds. Mechanical skin injuries, such as abrasions and cuts are classified into: (1) superficial wounds, (2) partial-thickness wounds and (3) full-thickness (deep) wounds [3]. Superficial wounds keep the dermis unaffected, whereas partial-thickness wounds penetrate the both the epidermis and dermis. In turn, deep wounds cut through entire skin to subcutaneous adipose tissue or deeper [3]. In fishes, mechanical skin injuries frequently stem from inadequate husbandry practices, traumatic incidents during handling, de-lousing procedures, sudden panic episodes, adverse weather conditions and contacts with predators [3]. The ulcers-like wounds primarily arise from microbiological pathogenic activities and skin lesions associated with various dermatological diseases [3]. Superficial and partial-thickness skin wounds in fishes are known to heal the most rapidly, often within hours to days, primarily involving re-epithelialization, limited inflammation and the restoration of the epidermis, accompanied by the activation of mucous cells [3,5]. In deep wound, full healing cascade is activated, with a more intricate response, involving the regeneration of diverse cell types, tissues and structures alongside additional healing stages such as scale differentiation, extracellular matrix generation, skin basal plate matrix development and basal plate mineralization [3]. Moreover, the tissue clefts may hinder keratocyte migration, leading to significant delays in deep wound healing in fishes, usually taking weeks to months, depending on wound severity, the fish species and the environmental conditions [3,9,12].

Within the last decade, extensive research has been dedicated to investigate the skin wound healing processes in various fish species, with a specific emphasis on understanding principles and dynamics of skin wound healing, the role of skin mucus in humoral defence mechanisms and factors that may enhance of delay skin wound healing process. So far, at least 13 different fish species, including model one as zebrafish (Danio rerio), and fishes commercially farmed in aquaculture, like salmonids (Salmonidae), carps (Cyprinidae), breams (Sparidae) and catfishes (Siluriformes) have been studied (reviewed in [3]. Among salmonid fishes, research on skin wounds regeneration have primarily focused on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Maraena whitefish (Coregonus maraena) holds significant ecological and aquacultural importance in Europe. In the southern Baltic Sea region, the species enjoys a revered status as a cherished traditional culinary delicacy, often served in the form of fried or smoked dishes. Due to various human activities such as water pollution, damming and overfishing natural populations of whitefish are considered as endangered [18]. Consequently, maraena whitefish is currently being reared under aquaculture both for food production and as stocking material to enhance wild populations through fishery supplementation in open waters [19,20]. However, detailed information on the mechanisms and recovery timeline of skin injury healing in maraena whitefish remains scarce, which hinders efforts to optimize the species’ commercial aquaculture husbandry protocols.

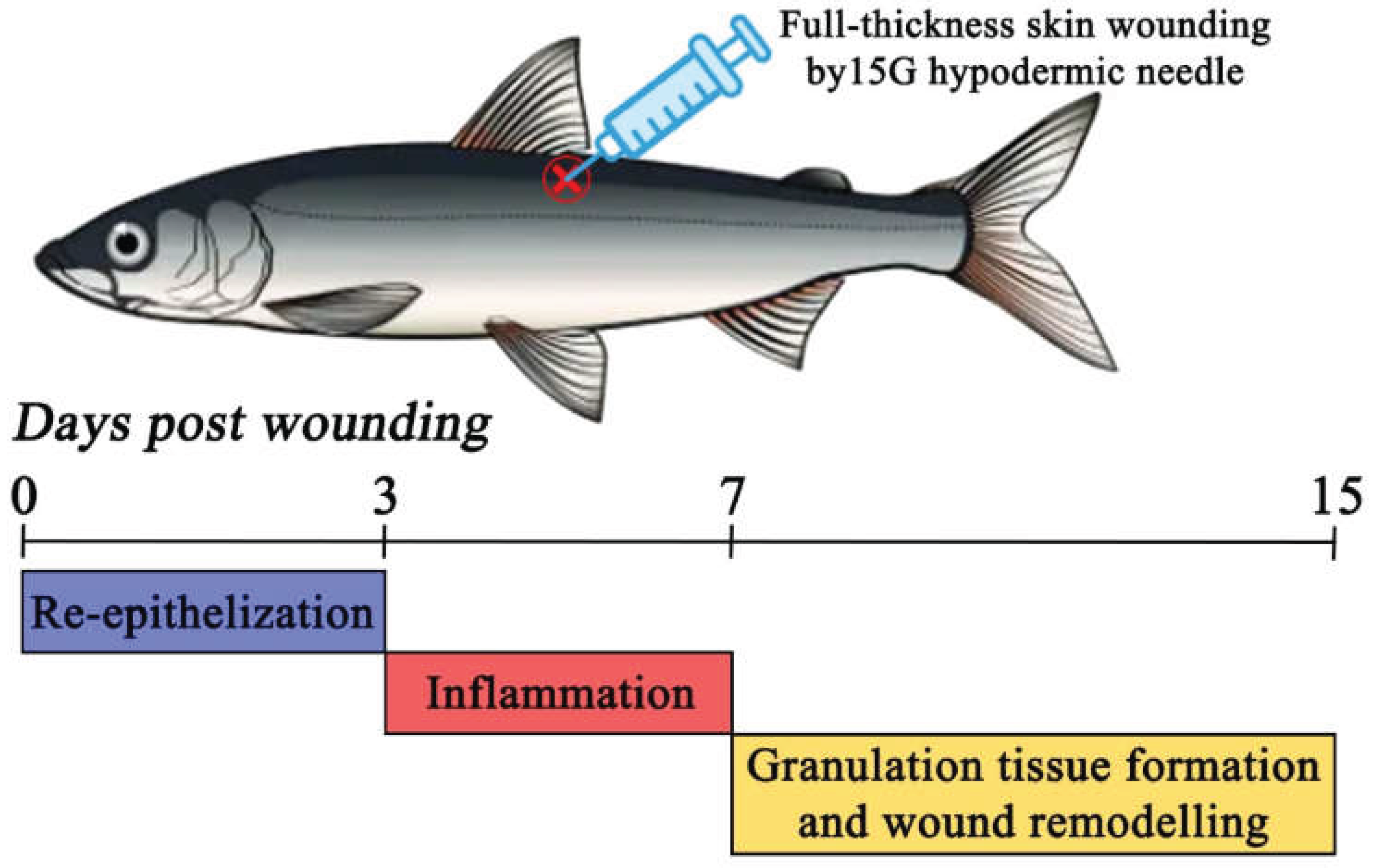

Therefore, the main objective of the current study was to characterize the healing process of full-thickness skin wounds on the dorsal flank of juvenile maraena whitefish specimens over a 15-day period, induced by puncturing with a 15G hypodermic needle. The conducted wounding procedure mimicked the standard practise of fish PIT tagging commonly performed in the aquaculture production of this species. The skin healing process in the species was studied through histological observations, as well as the analysis of selected gene expression involved in skin tissue regeneration process.

2. Results

2.1. Histological Analysis

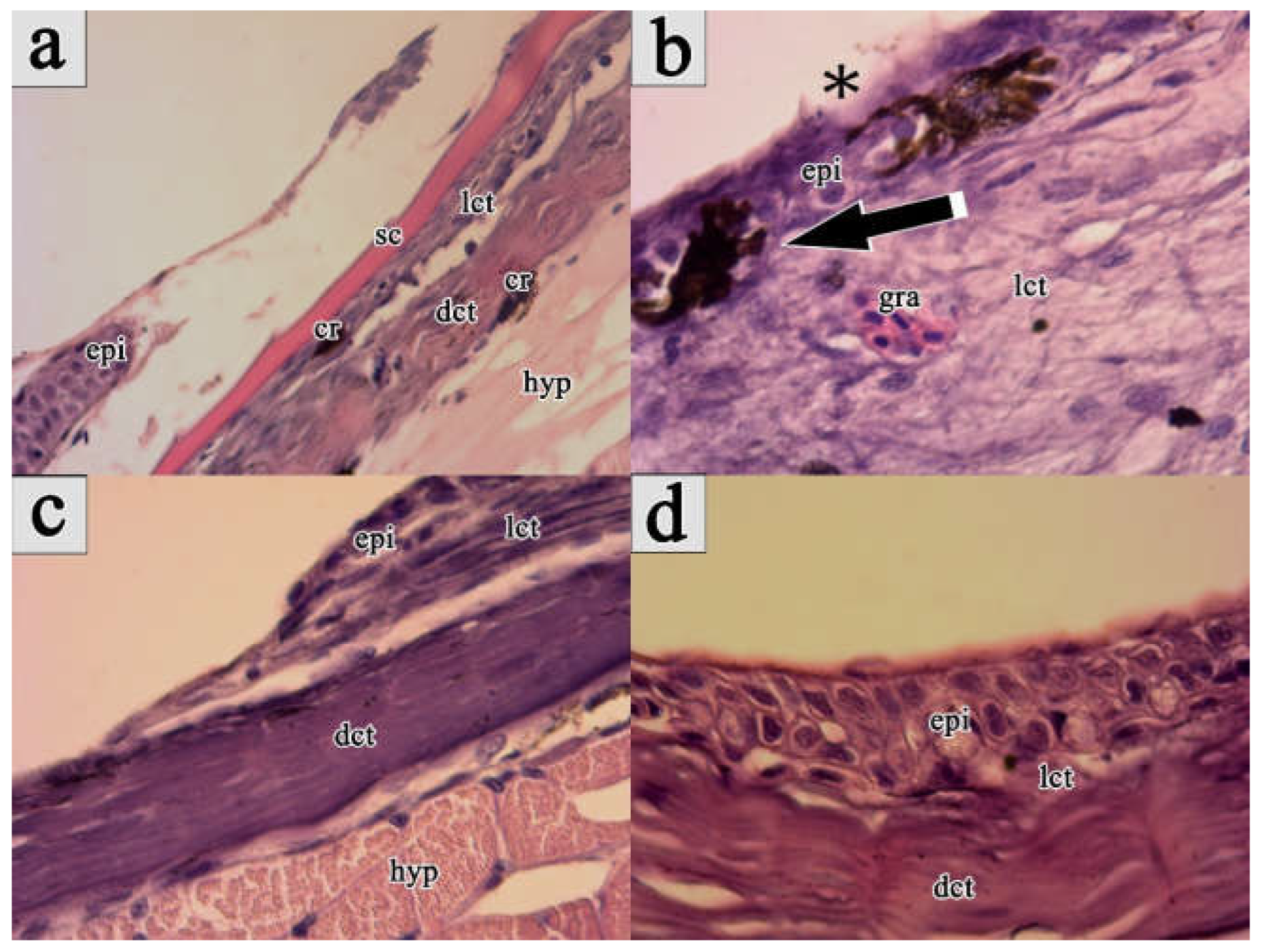

Full-thickness skin injury on the dorsal body part just below the dorsal fin was inflicted to each fish using a 15G hypodermic needle to histologically characterize the healing process of skin injury in the maraena whitefish. Performed mechanical wounding of skin in the examined fish resulted in breakdown of the continuity of epidermis and violation of dermis, along with bleeding without the formation of blood clots (

Figure 1a–d).

On the 1st post-wounding day, the wound site exhibited coverage by an amorphous exudate, with no apparent signs of regeneration. Instead, extensive loss of epidermal cells and haemorrhaging, along with the presence of migrating keratocytes at the wound margins were observed in the histological images. Mucous cells were additionally spotted alongside keratocytes at the migratory front. Pigmented bodies contributing to hyperpigmentation were also observed around the wound margins and remained present throughout the entire healing process (

Figure 1a).

On 3rd post-wounding day, the initial remodelling of damaged skin sites was observed. The wound bed was covered by a neo-epidermal layer with an organized appearance that lacked clear separation. At this stage of skin healing, the wound bed was predominantly characterized by damaged tissue fibers and infiltrating polymorph nucleated inflammatory cells, initiating acute inflammation. Many mucus cells, open to the extracellular space, were also spotted in the superficial layer of the epidermis, forming a thick mucus layer that covered the epithelial surface. Furthermore, intensive proliferation of keratocytes throughout the entire epidermal layer of the wound area was recorded. However, a lesser number of proliferating keratocytes were present at the wound margins. Enlarged melanophore cells were spotted in the epidermal layer of regenerating injury (

Figure 1b).

On 7th post-wounding day, the injuries exhibited partial contraction and were filled with granulation tissue. In the wound bed, both inflammation and tissue repair processes were prominent, accompanied by the presence of proliferating cells filling the area. The epidermal layer showed enhanced organization compared to the previous wound healing stage, with a clear separation from the wound bed and increased thickness in the wound center compared to the surrounding regions. At the wound margins, intensively proliferating cells were organized in an oval pattern across all samples. Newly formed collagen fibrils and myofibroblast-like cells with elongated phenotypes were also identified in the wound bed. Pigment cells, likely melanocytes, were observed infiltrating the fibrotic tissue, contributing to additional hyperpigmentation (

Figure 1c).

On 15th day of post-wounding, the wound site exhibited complete contraction, becoming indistinguishable from the undamaged skin tissue. All skin layers were completely regenerated, with the epidermis composed of a thick layer of keratocytes along with large mucous cells at the surface. The collagen fibres beneath the epidermis exhibited increased thickness and a more structured appearance compared to earlier stages of wound healing. Melanocytes were observed in two layers of the contracted wound, one beneath the epidermal layer and the other beneath the new collagenous tissue (

Figure 1d).

2.2. Gene Expression Analysis

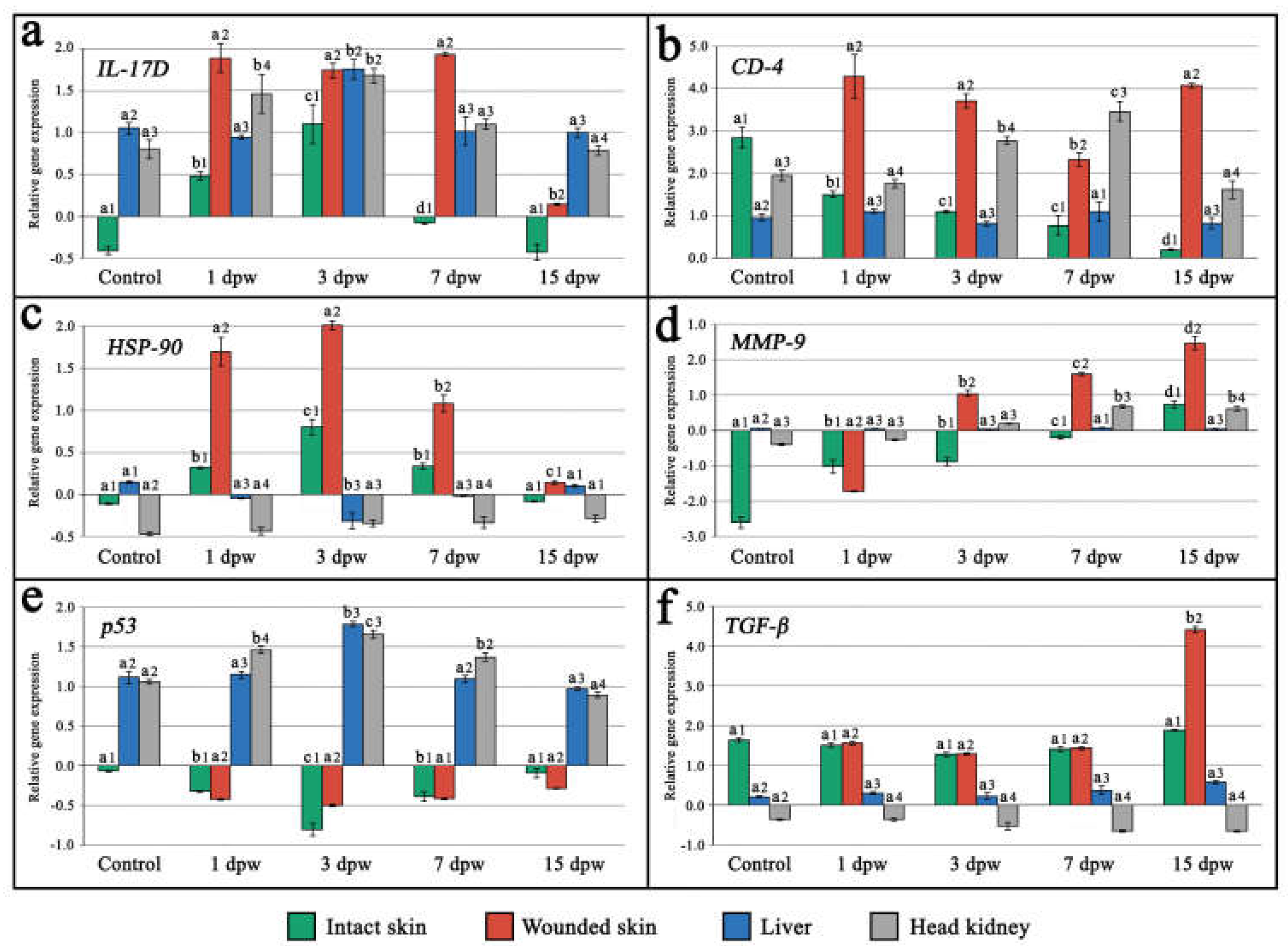

Overall, mRNA transcripts of all the investigated genes exhibited noticeable organ and tissue-specific patterns in the expression levels, reflecting a systemic response to a full-thickness skin injury in the examined maraena whitefish. Among all sampled tissues a significant upregulation in the transcription levels of the analyzed genes was mostly recorded within wounded skin tissues, apart from the

p53 protein (

p53) gene, which exhibited an opposite pattern (

Figure 2a–f).

A significant (

P<0.05) upregulation of

interleukin 17D gene (

IL-17D) expression was observed in all tissues and organs from fish subjected to skin injury between the 1st and 7th day post-wounding (dpw), with the most prominent increase in mRNA transcription levels detected within wounded skin tissue. The peak expression of the

IL-17D gene was detected on the 3rd dpw across all examined tissues, with comparable levels except from the intact skin, where expression was significantly lower (

P<0.05). Downregulation of

IL-17D gene expression to levels comparable to the control group was observed across all tissues on the 15th dpw (

Figure 2a).

In the case of

cluster of differentiation 4 (

CD-4) gene, a significant (

P<0.05) upregulation of mRNA transcription level was recorded in wounded skin tissue (on the 1st, 3rd and 15th dpw) and head kidney (on the 3rd and 7th dpw). In turn, a significant (

P<0.05) downregulation of

CD-4 gene expression in wounded skin and upregulation in the head kidney were observed on the 7th dpw. Compared to the control group, a significant (

P<0.05) downregulation in the expression of the

CD-4 gene was observed in the intact skin tissue of the wounded fish, showing a progressive decrease across all examined time points post-wounding. Lack of significant differences (

P>0.05) in mRNA transcription levels of the

CD-4 gene were detected in the liver (

Figure 2b).

A significant (

P<0.05) upregulation of

heat shock protein 90 (

HSP-90) gene expression was detected in both wounded and intact skin tissue between the 1st and 7th dpw, peaking on the 3rd dpw, followed by a subsequent downregulation on the 15th dpw to the levels observed in the control fish group. The recorded mRNA transcription levels of the

HSP-90 gene were significantly (

P<0.05) higher in the injured skin tissue when compared to the intact skin. In the liver of wounded fish, a consistent silencing of

HSP-90 gene expression was detected until the 3rd dpw, followed by subsequent upregulation on the 15th dpw to the levels observed in the control fish group. Insignificant differences (

P>0.05) in mRNA transcription levels of the

HSP-90 gene were observed in the spleen (

Figure 2c).

A steady but significant (

P<0.05) increase in mRNA transcription of

metalloproteinase-9 (

MMP-9) gene was recorded in all examined tissues across each time point post-wounding, except from the liver, where insignificant (

P>0.05) differences were observed. A peak in the expression level of the

MMP-9 gene across all examined tissues was observed on the 15th dpw, with the highest transcription level recorded in the injured skin tissue (

Figure 2d).

In the case of

p53 protein gene (

p53), a significant (

P<0.05) downregulation of mRNa transcription level was observed from the 1st to the 7th dpw in both wounded and intact skin tissues, reaching the lowest level on the 3rd dpw. Contrastingly, an essential (

P<0.05) upregulation of the

p53 gene was observed in the liver and spleen between the 1st and 7th dpw, attaining a peak on the 3rd dpw. Overall, mRNA transcription of the

p53 gene across all examined tissues returned to levels comparable to those observed in the control group on the 15th dpw (

Figure 2e).

Insignificant (

P>0.05) changes in the expression level of

the transforming growth factor-β (

TGF-β) gene were observed in all examined tissues, except for wounded skin, which displayed significant (

P<0.05) upregulation on the 15th dpw, reaching the highest level among all examined tissues and organs (

Figure 2f).

3. Discussion

In intensive aquaculture systems, fish commonly sustain skin injuries, such as lesions, scrapes or ulcers, not only due to natural disease processes but also because of mechanical trauma incidents that occurs under high stocking density conditions [21]. Once the skin barrier is breached, pathogens can easily invade organism, making the preservation of an intact epidermis vital for maintaining fish in good health and welfare in aquaculture settings [8,22]. Thus, to effectively implement strategies for preventing or treating both immediate and long-term skin damage, it is essential to understand the skin’s healing mechanisms and physiological responses in farmed fishes. In the present study, the healing process of full-thickness skin wound was investigated the in maraena whitefish by means of histological and gene expression analyses. The obtained results showed that complete regeneration following puncture with a 15G hypodermic needle required at least 15 days after injury infliction, with no clear distinction between early and late phases of healing. Moreover, the healing process of a skin in the examined species consisted of three main stages: (1) re-epithelization between 1st and 3rd day post wounding (dpw); (2) inflammation, between 3rd and at 7th dpw; as well as (3) granulation tissue formation and wound remodeling taking place between 7th and at least 15th dpw. In contrast, studies on Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout, using a 5–6 mm punch biopsy to create full-thickness wounds, have reported a clear distinction between early (1–14 dpw) and late (36–100 dpw) regeneration phases [12,16]. The results recorded in the current study align with previously reported dermal wound healing patterns in other fishes, with overall healing dynamics falling between those observed in thermophilic and cold-adapted species [3]. However, the observed wound healing dynamics and total recovery time in maraena whitefish may also be attributed to the nature of the inflicted wounds, as the technique used did not result in severe tissue loss in this study.

In fishes, re-epithelialization is crucial stage of tissue regeneration, as it establishes a protective barrier over the wound bed against pathogens and other harmful external factors [3]. In the present study, intensive re-epithelialization was noticed to occur between 1st and 3rd dpw in the examined maraena whitefish subjected to full-thickness skin wounding, mirroring responses previously reported in Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout [12,16].During re-epithelization in fishes, keratocyte cells collectively migrate as a sheet towards the wound area from all sides to cover the injury and the migration halts when the advancing cell fronts meet each other [3]. It is considered that the primary source of recruited keratocytes originates from the inter-scale pockets, underscoring their significance in the process of wound healing in fishes [9]. Through re-epithelization process keratocytes undergo structural changes, with superficial keratocytes flattening and developing microridges that enhance the epidermal surface for effective mucus retention, as well as gaseous and ionic exchange [23]. Similarly to Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout, the examined maraena whitefish individuals developed an amorphous exudate on the wound surface during regeneration, facilitating early keratocyte migration from adjacent epidermal layers [13,16]. Some authors hypothesized that coagulation-related genes, like antithrombin, urokinase and serpine1, might be involved in formation of this structure in fishes [16,24]. Additionally, the presence of mucous cells alongside migrating keratocytes at the wound borders was detected in the examined maraena whitefish, confirming the previous observations about ongoing differentiation of mucous cells during the wound re-epithelization in the Atlantic salmon [16]. Following the completion of the re-epithelization process in fishes, keratocyte proliferation occurs, leading to the formation and subsequent thickening of the neo-epidermis [11,16,26]. During this process, the newly formed neo-epidermis initially contains few mucous cells; however, as keratocytes proliferate, mucous cell numbers increase and appear apically in a bead-on-string arrangement [11,16]. Significant numbers of large mucous cells, open to the extracellular space, were also spotted in the examined maraena whitefish at 3rd dpw, likely indicating the initiation of an early innate immune defense protecting the neo-epidermis and wound bed against pathogens. As in other fish species, wounding of maraena whitefish also induced immediate hyperpigmentation with pigmented bodies and enlarged melanophores detected throughout all time points (especially at 3rd dpw) solely on wounded skin [3]. Considering the antioxidant properties of melanin and its role in safeguarding against environmental stressors (UV irradiation and oxidizing agents) and pathogens (especially through the synergistic antibacterial and antifungal properties of toxic intermediates generated during melanin biosynthesis), this pigmentation could serve as an initial mechanism to protect the wound surface [26,27,28].

Inflammatory response during injury healing is known to play important role in clearing the wound bed from damaged tissue and extracellular pathogens, as well as driving further repair process [3]. In fishes, the inflammatory response involves an initial influx of neutrophils and other leucocytes (B-cells and T-cells) to the wound site migrating from the head kidney followed by later arrival macrophages originating from blood-derived monocytes [12,16,24]. Acute inflammation in fishes is generally triggered by the activation of pro-inflammatory effectors such as chemokines and interleukins (especially, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, cox-2 and TNF), which guide leucocyte cells to infiltrate the wound area, along with the activation of proteases and other responders to cellular stress [3]. In the current study, histological and transcriptomic analyses revealed acute inflammation between 3rd and 7th dpw in the examined maraena whitefish. The recorded inflammation response in the examined species correlated with the significant upregulation of IL-17D, CD-4, p53, HSP-90 and MMP-9 genes that peaked on 3rd dpw, aligning with results previously reported in the Atlantic salmon [15,16]. Interleukin 17D, as other cytokines from family IL-17, plays an important in the initiation of inflammation response in fishes [29,30]. Thus, the recorded at 3 dpw multi tissue/organ upregulation peak in expression of IL-17D gene in the examined maraena whitefish seems to reflect whole-organism activation of inflammation. In turn, MMP-9 is a representative of proteases secreted by both keratocytes and macrophages, known to play a pivotal role in degrading extracellular matrices like laminins and fibrillar collagens, while also modulating inflammation by regulation the activity of cytokines and chemokines [12,14,31,32]. Moreover, the release of metalloproteinases eases the migration of keratocytes during re-epithelialization and initiates secreting growth factors from the wound matrix [33,34]. Multiple reports have indicated that under- and over-activity of metalloproteinases may disrupt the inflammatory response in fish, leading to a delay in the formation of repair tissue [15,35,36]. In the present study, a steady upregulation of MMP-9 gene was recorded at each time point post-wounding, indicating positive correlation with ongoing advancement of healing process in maraena whitefish. The heat shock protein 90 (HSP-90) represents a chaperon protein family synthesized in response to cellular stress that play an important role in the degradation of damaged cells and wound remodeling during the injury healing process in animals [37,38]. In experimentally wounded maraena whitefish, peak expression of the HSP-90 gene was detected at 3 dpw, confirming the onset of the acute inflammatory response. Interestingly, a significant upregulation p53 gene in wounded maraena whitefish under the current study was recorded only in the liver and head kidney at 3rd dpw. As the p53 protein plays a crucial role in defense against systemic autoimmunity by controlling the DNA repair process, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [39,40], its increased expression in the liver and head kidney may be necessary for the regulation of lymphocytic cell numbers and the removal of erroneous cells during the intensive production phase of inflammation in wound healing. The histology analysis also revealed that the inflammatory response in wounded maraena whitefish was accompanied by a surge of open mucous cells and increased melanin pigmentation across the wound surface, potentially serving as protective mechanisms against external harmful factors [3].

Granulation tissue formation, together with would remodeling, is the final phase of wound healing in animals and involves intensive growth of repair tissue from the wound borders that gradually covers and contracts the wound, replacing damaged area with new tissue [16,24,41]. During this stage of wound healing scale differentiation process is also observed, as pre-osteoblast bone cells proliferate from mesenchymal stem cells, followed by the deposition of a mineralized matrix [12,16,42]. The granulation tissue formation and pronounced wound remodeling was recorded in the examined maraena whitefish between the 7th and 15th dpw, representing an intermediate timing compared to zebrafish and Atlantic salmon, in which it forms at 2nd and 14th dpw, respectively [16,24]. The granulation tissue formation in the examined maraena whitefish was accompanied by an inflammatory response and intensive pigment cell infiltration into the fibrotic tissue, which is known to play a key role in initiation of dermal repair process through stimulation of fibroblast recruitment, as well as their further proliferation and growth [3]. In fishes, the repair tissue typically consists of connective tissue, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, inflammatory and immune cells, as well as small blood vessels. The granulation tissue also exhibits hyperpigmentation due to infiltration by melanocytes in fishes, which was also observed in the current study on maraena whitefish [3]. In the current study, inflammation response was recorded in experimentally injured maraena whitefish alongside granulation tissue formation. Numerous studies indicate that inflammation plays a crucial role in both fibroblast recruitment and granulation tissue formation in fishes, being essential for activation dermal repair through fibroblast proliferation and growth-stimulating signals factors from inflammatory cells [3]. Along the remodeling of injury, alterations in the type, quantity and organization of collagen also take place in fishes, contributing to wound scaring and an improvement in the tensile strength of the tissues [3,43]. Recent research on Atlantic salmon revealed that wound contraction during injury healing process is facilitated by the presence of distinct collagen fibers with three to four rope-like structures in granulation tissue, likely formed by fibroblast migration from the myocommata [16], which is the major connective tissue compartment in teleost fish muscle tissue. Myofibroblast-like cells were also observed within the formed granulation tissue in the examined maraena whitefish under the current study, supporting the hypothesis of their potential involvement in the wound contraction process in fishes [3]. Similarly to the recorded results in the current study, significant upregulation of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), along with several other genes involved in activation of collagen synthesis, fibril maturation and fibroblasts growth was reported in Atlantic salmon during the late wound healing phase [16]. Analyzed in the current study, TGF-β gene is involved in the regulation of fibroblasts and keratocytes movement to the wound site, acting as a growth factor for fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells [44]. Moreover, the mentioned gene regulates wound remodeling and scarring by activating cell proliferation at the lesion site, while dampening the ongoing inflammation [45,46,47]. In the present study, significant upregulation of TGF-β together with MMP-9 gene was recorded at 15th dpw despite histological signs of complete regeneration, suggesting that molecular processes associated with tissue remodeling are still active in the experimentally injured maraena whitefish.

The immune system is pivotal in preserving organism's physiological balance by detecting alterations from normal conditions and reacting to injuries, infections and other environmental stressors [47,48,49]. The adaptive immune response is particularly considered as essential factor supporting the wound healing process in fishes, where activated lymphocytes play a crucial role in initiation inflammation and fibrotic repair [4,50]. In the case of fish, immune responses encompass two main types: (1) humoral immunity, which involves antibody production by activated B cells in response to antigens and (2) cellular immunity, wherein activated cytotoxic T cells release cytokines and directly eliminate pathogens [51,52,53,54]. Significant upregulation of the CD-4, along with IL-17D gene in the injured skin tissue of maraena whitefish were observed in the present study from the 1st dpw and lasted till the last day of experiment, indicating pronounced activation strong innate and adaptive immune cellular responses, which is typical for fish experiencing skin damage during the early and late wound healing stages [3]. The CD-4 gene encodes a protein known as CD4, which is primarily expressed on the surface of CD4+ T cells (also known as helper T cells) that are a type of T lymphocyte [55]. The CD4+ T cells play a key role in immune functioning by aiding other immune cells like B cells and cytotoxic T cells, that directly kill pathogens and secrete cytokines that further drive the ongoing immune response, inflammation and tissue remodeling during the wound healing process [52,54,56,57]. Additionally, CD4+ T cells are known to play an important role as enhancer of the injury healing process driving collagen deposition in the wound [55]. The recorded activation of cellular immunity mediated by cytotoxic T cells within wounded tissue is most probably caused by the exposure of maraena whitefish tissues to an unsterile environment due to inflicted mechanical wounding. Beyond wounded tissue, significant upregulation of CD-4 gene mRNA transcription was additionally recorded on 3rd and 7th dpw in the head kidney of the examined species, which may relate to ongoing high rate of monocytopoiesis in this organ as usually occurs in teleost fishes during the activation of immune response [58]. The recorded slight downregulation of CD-4 gene at 7th dpw in the damaged skin might signify a transitional point between the innate and adaptive immune responses in the examined species.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics

The study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Polish ACT of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, Journal of Laws 2015, item 266. The protocol was approved by the Local Ethical Committee for Experiments on Animals in Olsztyn (no. 31/2013).

4.2. Fish Origin

The maraena whitefish specimens examined in this study were obtained from the Department of Sturgeon Fish Breeding, National Inland Fisheries Research Institute in Olsztyn, located in Pieczarki, Poland (54°6′49.01″N 21°47′50.07″E). To investigate the healing process of full-thickness skin wounds, fifty maraena whitefish specimens within the first year of life (mean body weight of 3.80 ± 0.27 g and length 8.10 ± 0.34 cm per individual) were used. The experiment was conducted at the Center of Aquaculture and Ecological Engineering, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland. For this purpose, the fish were placed in 100-liter tanks with a water flow rate of 10 liters per minute, operating within a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) and maintained for a six-week acclimation period to culture conditions. The average water temperature was 11.3 ± 0.2°C and the oxygenation level consistently exceeded 80%. The fish were fed with Aller Safir 1mm-XS-S (Aller Aqua, Poland) three to four times per day in amount of 1.0% fish biomass.

4.3. Experimental Setup and Sampling

Following the acclimation period and the health assessment, all fish were randomly stocked into five separate 50-liter tanks (ten fish per each). The fish from four tanks were experimentally injured with a skin puncture on the dorsal body just below the dorsal fin (experimental groups), while the fish from the last tank remained untouched (control group). A 15G hypodermic needle was used to create a full-thickness wound penetrating all skin layers, mimicking standard procedure of fish PIT tagging carried out in aquaculture production of the species. To minimize the risk of transferring pathogenic agents among the fish, separate needles were used for wounding. Anaesthetic agents were not used during skin wounding due to a lack of reliable information regarding their potential effects on the transcriptome in the examined fish. Following the skin puncture, each fish was photographed and and returned to its tank for observation up to 15 days post-wounding (dpw).

For transcriptome analyses, liver, head kidney, as well as skin samples from both wounded and intact sides were collected from five randomly selected fish per each experimental tank on the 1st, 3rd, 7th and 15th dpw. Moreover, samples from the untouched fish in control tank were collected at the beginning of experiment (day after acclimation period) and included the same tissues/organs. For this purpose, the selected fish were humanely sacrificed by cutting spiral cord before sampling. All the tissues collected were immediately placed into RNAlater™ solution (Life, USA), incubated at 4°C for 24 hours and finally stored at -24°C until RNA extraction and purification. Wounded skin was also dissected from the remaining five fish in each test tank for histological analysis and fixed in Bouin’s solution on the same days as the transcriptomic sampling. Prior to tissue collection, the fish were euthanized with an overdose of MS-222 (500 mg/L; Sigma, Brøndby, Denmark).

4.4. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from preserved in tissues RNAlater using TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), following manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue homogenization was carried out by MagNA Lyser (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Residual DNA in the extracted RNA samples was removed using recombinant DNase I enzyme (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland). RNA concentration and purity were checked with a NanoDrop 2000 photometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA) and RNA integrity was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The obtained RNA samples were immediately processed further.

The cDNA synthesis was carried out using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with isolated RNA templates of satisfactory quality. The reaction mixtures were prepared in a total volume of 20 µl, consisting of 1x reaction buffer (8 mM MgCl2), 2,5 µM anchored-oligo(dT)18 primers, 1 mM of dNTP mix, 20U RNA-se Inhibitor, 10U Reverse Transcriptase and 1 µg of RNA sample. The reverse transcription reactions were carried out on a Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The samples were incubated for 30 min at 55°C and terminated by heating at 85°C for 5 min. The obtained cDNA samples were diluted 1:10 in DEPC-treated water and used for further qPCR analysis.

The real-time PCR analysis was carried out using previously designed primers for six genes involved in immune response and inflammation (

interleukin 17D and

cluster of differentiation 4), cellular stress response and protein folding (

heat shock protein 90), as well as cell proliferation and tissue repair (

metalloproteinase-9,

p53 protein and

transforming growth factor-β) (

Table 1). In turn,

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit 6 (

eIF3S6) was chosen as the housekeeping gene due to its stable expression level across different tissues regardless of tissue damage and other external environmental conditions [32,59]. The qPCR was carried out separately for housekeeping and target genes by a LightCycler II 480 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using the SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The Real-Time reaction mixtures were prepared in a total volume of 10 µL, consisting of 1X SYBR Green I Master Mix, 150-500 nM of each primer and 1 µL of diluted cDNA template. The Real-Time PCRs were run in triplicates with the following thermal cycling conditions: an initial polymerase activation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s (denaturation), 56°C for 10 s (primer annealing) and 72°C for 15 s (elongation). Reaction efficiencies were estimated from the slopes of the standard curves made of 5-point, and 10-fold serial cDNA dilutions starting from 10 ng/L. The amplification efficiency for all primer pairs fell within the range of 90

–110%. Throughout each run, negative controls involving pure water and non-transcribed RNA were employed to control chemistry contamination and the potential influence of any remaining genomic DNA in the samples. The analysis of the melting curve (60

–95°C) at the end of each run concluded the protocol. Fluorescence data were collected after the elongation step and in 0.5°C steps on the melting curve. The relative expression levels of each analyzed target genes were calculated based on the difference between Ct values for reference and target genes using the formula 2

-ΔΔCt, according to methodology described by Pfaffl [60].

4.5. Histological Observations

Fixed in Bouin’s solution fragments of wounded skin tissue samples were dehydrated by the standard procedure of transferring through a series of alcohol solutions of increasing concentrations at 35°C (between 80%, 2×1 h and 95%, 2 ×1 h) up to 100 % alcohol (4 × 1 h). The dehydrated tissues were placed in xylene (2×1.5 h, at 35°C) and then embedded in the paraffin (3×1h, 58°C, three times), using tissue processor Leica TP 1020 (Leica Biosystems, USA). The fixed tissues were cut into slices between 4–6μm thick using a LEICA RM 2165 rotational microtome (LEICA Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The slices were stained using a routine hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining method [61]. The histological slides were analysed under an optical microscope (Axio Scope A1, Zeiss, Germany) equipped with the micro image computer analysis software AxioVs40 v 4.8 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany). The nomenclature of cellular structures and cell types in the analysed tissues was adapted according to Sveen et al. [3].

4.6. Statistical Analysis

The recorded values of relative quantification of examined target genes across sampled tissues were analyzed using Statistica software v.10.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA). Prior statistical test selection, data distribution normality and homogeneity of variance were tested by Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s test, respectively. ANOVA’s HSD Tukey post hoc test was used to determine significant differences (P<0.05) in the gene expression level between the experimental groups, tissues and time points of fish wounding.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides preliminary insights into the skin healing process in the maraena whitefish that holds significant ecological and aquacultural importance in Europe. The recorded results of histological observations together with gene expression analyses revealed that full-thickness skin wounding in the examined species not only triggers a dermal-specific response but also exerts a systemic influence on multiple organs and tissues. The complete regeneration following puncture with a 15G hypodermic needle in the examined species required at least 15 days, without a clearly demarcated transition between early and late phases of healing. Moreover, the healing process of a skin in the maraena whitefish consisted of three main stages, namely: (1) re-epithelization between 1st and 3rd day post wounding (dpw); (2) acute inflammation, between 3rd and at 7th dpw; as well as (3) granulation tissue formation and wound remodeling taking place between 7th and 15th dpw (

Figure 3). The recorded results parallel with the dermal wound healing observed in other fish species with overall time dynamics exhibiting intermediate between warm- and cold-water fish species. However, the observed wound healing dynamics and total recovery time in maraena whitefish may also be attributed to the nature of the inflicted wounds, as the technique used did not result in severe tissue loss in this study. Collectively, the recorded findings deepen our understanding of epidermal barrier restoration in maraena whitefish and provide a foundation for optimizing welfare-oriented husbandry practices, such as stocking densities, wound-care regimens, or immunomodulatory treatments to enhance skin integrity and disease resistance of the species in aquaculture settings. Future studies should explore how factors such as temperature, stocking density, and wound severity modulate the wound healing process described in this study, providing valuable insights for further optimization of the species’ aquaculture production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.-B., T.W.; methodology, D.F.-B., T.W., M.K., and T.L.; software, M.K., T.L., and A.W.; validation, M.K., and T.L.; investigation, T.W., M.K., and T.L., resources, D.F.-B., T.W., and A.W.; data curation, M.K., T.L., and T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., T.L., D.F.-B. and T.W.; writing—review and editing, M.K., T.L., D.F.-B., T.W., and A.W.; visualization, M.K, T.L., and T.W.; supervision, D.F.-B.; project administration, D.F.-B.; funding acquisition, D.F.-B., and T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UWM in Olsztyn, Poland Statutory Grant No: 11.610.015-110 and the UWM project number: GW/2014/19.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (decision No. 31/2013), and it was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Polish ACT of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, Journal of Laws 2015, item 266.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miroslaw Szczepkowski for providing maraena whitefish individuals for the current research. We also thank Elzbieta Ziomek for laboratory assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Esteban, M.A. An Overview of the Immunological Defenses in Fish Skin. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 853470. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, M.Á.; Cerezuela, R. Fish Mucosal Immunity: Skin. In Mucosal Health in Aquaculture; Academic Press: 2015; pp. 67–92.

- Sveen, L.; Karlsen, C.; Ytteborg, E. Mechanical Induced Wounds in Fish – A Review on Models and Healing Mechanisms. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2446–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, H.; Cuesta, A.; Meseguer, J.; Esteban, M.A. Characterization of the Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata L.) Immune Response under a Natural Lymphocystis Disease Virus Outbreak. J. Fish Dis. 2016, 39, 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Francisco, D.; Cordero, H.; Guardiola, F.A.; Cuesta, A.; Esteban, M.Á. Healing and Mucosal Immunity in the Skin of Experimentally Wounded Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata L). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 71, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, F.A.; Cuartero, M.; Collado-González, M.M.; Arizcún, M.; Diaz Banos, F.G.; Meseguer, J.; Esteban, M.A. Description and Comparative Study of Physico-Chemical Parameters of the Teleost Fish Skin Mucus. Biorheology 2015, 52, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado, J.; Fuentes-Almagro, C.A.; Guardiola, F.A.; Cuesta, A.; Esteban, M.Á.; Prieto-Álamo, M.J. Proteomic Profile of the Skin Mucus of Farmed Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata). J. Proteomics 2015, 120, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontenot, D.K.; Neiffer, D.L. Wound Management in Teleost Fish: Biology of the Healing Process, Evaluation, and Treatment. Vet. Clin. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2004, 7, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.; Metzger, M.; Knyphausen, P.; Ramezani, T.; Slanchev, K.; Kraus, C.; …; Hammerschmidt, M. Re-Epithelialization of Cutaneous Wounds in Adult Zebrafish Combines Mechanisms of Wound Closure in Embryonic and Adult Mammals. Development 2016, 143, 2077–2088.

- Sundin, L.; Nilsson, G.E. Acute Defense Mechanisms against Hemorrhage from Mechanical Gill Injury in Rainbow Trout. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1998, 275, R460–R465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.B.; Wahli, T.; McGurk, C.; Eriksen, T.B.; Obach, A.; Waagbø, R.; …; Tafalla, C. Effect of Temperature and Diet on Wound Healing in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 41, 1527–1543. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.G.; Andersen, E.W.; Ersbøll, B.K.; Nielsen, M.E. Muscle Wound Healing in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 48, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahli, T.; Verlhac, V.; Girling, P.; Gabaudan, J.; Aebischer, C. Influence of Dietary Vitamin C on the Wound Healing Process in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2003, 225, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnov, A.; Skugor, S.; Todorcevic, M.; Glover, K.A.; Nilsen, F. Gene Expression in Atlantic Salmon Skin in Response to Infection with the Parasitic Copepod Lepeophtheirus salmonis, Cortisol Implant, and Their Combination. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sveen, L.R.; Timmerhaus, G.; Krasnov, A.; Takle, H.; Stefansson, S.O.; Handeland, S.O.; Ytteborg, E. High Fish Density Delays Wound Healing in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveen, L.R.; Timmerhaus, G.; Krasnov, A.; Takle, H.; Handeland, S.; Ytteborg, E. Wound Healing in Post-Smolt Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugelvik, M.S.; Dalvin, S. The Effect of Different Intensities of the Ectoparasitic Salmon Lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) on Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar). J. Fish Dis. 2022, 45, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FishBase, 2025, 〈https://fishbase.mnhn.fr/summary/Thymallus-thymallus〉(accessed 18 May 2025).

- Fopp-Bayat, D.; Kaczmarczyk, D.; Szczepkowski, M. Genetic Characteristics of Polish Whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus maraena) Broodstocks—Recommendations for the Conservation Management. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 60, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochert, R.; Horn, T.; Luft, P. Maraena Whitefish (Coregonus maraena) Larvae Reveal Enhanced Growth during First Feeding with Live Artemia Nauplii. Fish. Aquat. Life 2017, 25, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M. Differential Diagnosis of Ulcerative Lesions in Fish. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109 (Suppl. 5), 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Noga, E.J. Skin Ulcers in Fish: Pfiesteria and Other Etiologies. Toxicol. Pathol. 2000, 28(6), 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilhac, A.; Sire, J.Y. Spreading, Proliferation, and Differentiation of the Epidermis after Wounding a Cichlid Fish, Hemichromis bimaculatus. Anat. Rec. 1999, 254(3), 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.; Slanchev, K.; Kraus, C.; Knyphausen, P.; Eming, S.; Hammerschmidt, M. Adult Zebrafish as a Model System for Cutaneous Wound-Healing Research. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133(6), 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.G. Wound healing in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and common carp (Cyprinus carpio): with a focus on gene expression and wound imaging. Doctoral dissertation Technical University of Denmark 2013.

- Nosanchuk, J.D.; Casadevall, A. Impact of Melanin on Microbial Virulence and Clinical Resistance to Antimicrobial Compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50(11), 3519–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczykowska, E. Stress Response System in the Fish Skin—Welfare Measures Revisited. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 436622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozdowska, M.; Sokołowska, E.; Pomianowski, K.; Kulczykowska, E. Melatonin and Cortisol as Components of the Cutaneous Stress Response System in Fish: Response to Oxidative Stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2022, 268, 111207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunimaladevi, I.; Savan, R.; Sakai, M. Identification, Cloning and Characterization of Interleukin-17 and Its Family from Zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006, 21(4), 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenaga, H.; Kono, T.; Sakai, M. Isolation of Seven IL-17 Family Genes from the Japanese Pufferfish Takifugu rubripes. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 28(5–6), 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Mano, N.; Rahman, M.H.; Hirose, H. MMP-9 Is Expressed during Wound Healing in Japanese Flounder Skin. Fish. Sci. 2006, 72, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skugor, S.; Glover, K.A.; Nilsen, F.; Krasnov, A. Local and Systemic Gene Expression Responses of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) to Infection with the Salmon Louse (Lepeophtheirus salmonis). BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.K.; Garcia, M.S.; Isseroff, R.R. Wound Re-Epithelialization: Modulating Keratinocyte Migration in Wound Healing. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12(3), 2849–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, M.; Jackson, C.J. Extracellular Matrix Reorganization during Wound Healing and Its Impact on Abnormal Scarring. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4(3), 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, M.J.; Han, Y.P.; Garcia, E.; Goldberg, M.; Yu, H.; Garner, W.L. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Delays Wound Healing in a Murine Wound Model. Surgery 2010, 147(2), 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landen, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from Inflammation to Proliferation: A Critical Step during Wound Healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krone, P.H.; Lele, Z.; Sass, J.B. Heat Shock Genes and the Heat Shock Response in Zebrafish Embryos. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997, 75(5), 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, G.K.; Thomas, P.T.; Forsyth, R.B.; Vijayan, M.M. Heat Shock Protein Expression in Fish. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1998, 8, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzuzan, P.; Woźny, M.; Ciesielski, S.; Łuczyński, M.K.; Góra, M.; Kuźmiński, H.; Dobosz, S. Microcystin-LR Induced Apoptosis and mRNA Expression of p53 and cdkn1a in Liver of Whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus L.). Toxicon 2009, 54(2), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.J.; Liu, P.; Wang, W. Characterization of the Tilapia p53 Gene and Its Role in Chemical-Induced Apoptosis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borena, B.M.; Martens, A.; Broeckx, S.Y.; Meyer, E.; Chiers, K.; Duchateau, L.; Spaas, J.H. Regenerative Skin Wound Healing in Mammals: State-of-the-Art on Growth Factor and Stem Cell Based Treatments. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 36(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sire, J.Y.; Allizard, F.; Babiar, O.; Bourguignon, J.; Quilhac, A. Scale Development in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Anat. 1997, 190(4), 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.S.; Ladwig, G.; Wysocki, A. Extracellular Matrix: Review of Its Roles in Acute and Chronic Wounds. World Wide Wounds 2005, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos, S.; Stojadinovic, O.; Golinko, M.S.; Brem, H.; Tomic-Canic, M. Growth Factors and Cytokines in Wound Healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008, 16(5), 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari, N.; Kawakami, A. Mature and Juvenile Tissue Models of Regeneration in Small Fish Species. Biol. Bull. 2011, 221(1), 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfe, K.J.; Grobbelaar, A.O. A Review of Fetal Scarless Healing. ISRN Dermatol. 2012, 2012, Article ID 698034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.G.; Nielsen, M.E. Expression of Immune System-Related Genes during Ontogeny in Experimentally Wounded Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) Larvae and Juveniles. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 42(2), 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.W.; Muir, I.F.K. The Role of Lymphocytes in Wound Healing. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1990, 43(6), 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.; Esteban, M.Á. Effect of Dietary Supplementation with Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae on Skin, Serum and Liver of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata L). J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97(3), 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Krieg, T.; Davidson, J.M. Inflammation in Wound Repair: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127(3), 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, S.K. The Innate Immune Response of Finfish–A Review of Current Knowledge. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007, 23(6), 1127–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Secombes, C.J. The Cytokine Networks of Adaptive Immunity in Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35(6), 1703–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, T.Y. Immunity to Betanodavirus Infections of Marine Fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 43(2), 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirbulescu, R.F.; Boehm, C.K.; Soon, E.; Wilks, M.Q.; Ilieş, I.; Yuan, H.; ... Poznansky, M.C. Mature B Cells Accelerate Wound Healing after Acute and Chronic Diabetic Skin Lesions. Wound Repair Regen. 2017, 25(5), 774–791.

- Efron, J.E.; Frankel, H.L.; Lazarou, S.A.; Wasserkrug, H.L.; Barbul, A. Wound Healing and T-Lymphocytes. J. Surg. Res. 1990, 48(5), 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, Y.; Yoshizaki, A.; Komura, K.; Shimizu, K.; Ogawa, F.; Hara, T.; ... Sato, S. CD19, a Response Regulator of B Lymphocytes, Regulates Wound Healing through Hyaluronan-Induced TLR4 Signaling. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175(2), 649–660. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ceballos-Francisco, D.; Guardiola, F.A.; Huang, D.; Esteban, M.Á. Skin Wound Healing in Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata L.) Fed Diets Supplemented with Arginine. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 104, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, A.F. The Evolution of Inflammatory Mediators. Mediators Inflamm. 1996, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, K.M.; Hinch, S.G.; Sierocinski, T.; Clark, T.D.; Eliason, E.J.; Donaldson, M.R.; ... Miller, K.M. Consequences of High Temperatures and Premature Mortality on the Transcriptome and Blood Physiology of Wild Adult Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Ecol. Evol. 2012, 2(7), 1747–1764.

- Pfaffl, M.W. A New Mathematical Model for Relative Quantification in Real-Time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29(9), e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawistowski, S. Histological Technique, Histology and the Principles of Histopathology; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).