1. Introduction

Human civilisation, ecosystems, and life depend on water. However, because of the innate intricacy and variability of hydrological processes, knowing and controlling water resources presents a great obstacle. These processes are affected by a range of interacting physical, chemical, and biological elements across various scales, from rainfall production and infiltration to streamflow dynamics and groundwater movement. Although traditional hydrological models are very useful, they sometimes depend on simplified assumptions or empirical correlations that may not completely capture the system's real behaviour or the widespread uncertainties inside measured data (Dembélé et al., 2020; Van Stan II & Simmons, 2024).

Over the last few decades, entropy has become a strong conceptual basis for measuring and interpreting disorder, uncertainty, and information content in complicated systems—including those seen in hydrology. Starting in thermodynamics with Rudolf Clausius and developed into information theory by Claude Shannon, entropy offers a global measurement of the unpredictability or randomness of a system (Mageed, 2024a; Mageed 2024b; Mageed & Zhang, 2023). From regionalization and network design to flood forecasting and water quality assessment, hydrology uses it over several fields (Mageed & Zhang, 2022; Koutsoyiannis & Montanari, 2022).

Although it is becoming increasingly well-known, entropy modelling in hydrology has its shortcomings and open questions. Difficulties with data needs, physical interpretation, computing intensity, and incorporation with other modelling approaches remain. This paper seeks to systematically answer these issues first by presenting a brief overview of established entropy applications, then by analyzing the existing open problems and challenges, finally by imagining the path of next-generation entropic hydrology. Through highlighting these important areas, this work hopes to inspire new research directions and speed up the integration of entropy concepts into mainstream hydrological science.

2. Theoretical Foundations of Entropy in Hydrology

Two main interpretations of entropy—thermodynamic entropy and informational entropy—find major applications in hydrology. Though different in their roots, they both provide insightful observations about the behaviour of hydrological systems.

2.1. Thermodynamic Entropy in Hydrology

According to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, thermodynamic entropy holds that the entropy of an isolated system tends over time to rise, therefore indicating more or dispersion of energy. This usually refers in hydrological situations to processes including energy dissipation, evaporation, and water movement along a gradient. Some scientists have investigated the idea of maximal entropy generation (MEP) as a guiding compass, implying that natural systems develop towards states that maximize the rate of entropy production (Li & Izumida 2023; Jaime Gómez-Hernández et al., 2020). This view offers a physical foundation for interpreting hydrological events including river network development or energy flux distribution. For example, soil hydrological processes generate entropy, therefore offering a thermodynamic framework for their mathematical representation (Schroers et al., 2022).

2.2. Informational Entropy (Shannon Entropy)

The widespread application of entropy in hydrology comes from Claude Shannon's information theory (Mageed, 2023b). Shannon entropy,

, quantifies the average uncertainty associated with a random variable X with a probability mass function

where the logarithm has a base

, (often 2 for bits, e for nats). A higher entropy value means greater uncertainty or spreads in the distribution of the variable.

Among key information theoretic ideas drawn from Shannon entropy are:

Joint Entropy assesses the unpredictability of two or more randomly occurring variables taken together.

Conditional entropy measures the unpredictability of given that is known.

Measures the amount of information one random variable contains about another. It estimates the lowering of uncertainty about one variable when the other is given.

Distinguishing cause from effect, transfer entropy is an extension of mutual information that measures the directed transfer of information between two time series (Mageed, 2024c; Moraffah et al., 2021).

These criteria offer strong instruments for studying dependencies, redundancies, and information streams inside sophisticated hydrological datasets and models (Koutsoyiannis, & Montanari, 2022; Eibeck et al., 2024).

2.3. Principle of Maximum Entropy (PME)

Jaynes developed the Principle of Maximum Entropy (PME) in 1957 to show that when constraints are known about a situation the maximum entropy distribution best represents the available or missing information. Hydrology researchers find the principle most valuable for situations when data limitations exist because they can create unbiased probability distributions through known information (Sreeparvathy & Srinivas, 2020; Sharma et al., 2023). The principle of maximum entropy serves as a basis for determining channel velocities and predicting uncertain hydrological distributions and planning network optimization in various studies (Farajpanah et al., 2024; Prajapati et al., 2024).

3. Applications of Entropy in Hydrology

Entropy modelling has proven itself useful in several aspects of hydrology and water resource management.

3.1. Hydrological Network Design and Evaluation

Technology's development has changed our means of living, working, and communicating. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and blockchain among other advances are changing businesses and providing fresh chances. Businesses hence must change to remain competitive. Companies wanting to flourish in the present market must embrace digital transformation rather than just an option.

3.2. Rainfall-Runoff Modelling and Forecasting

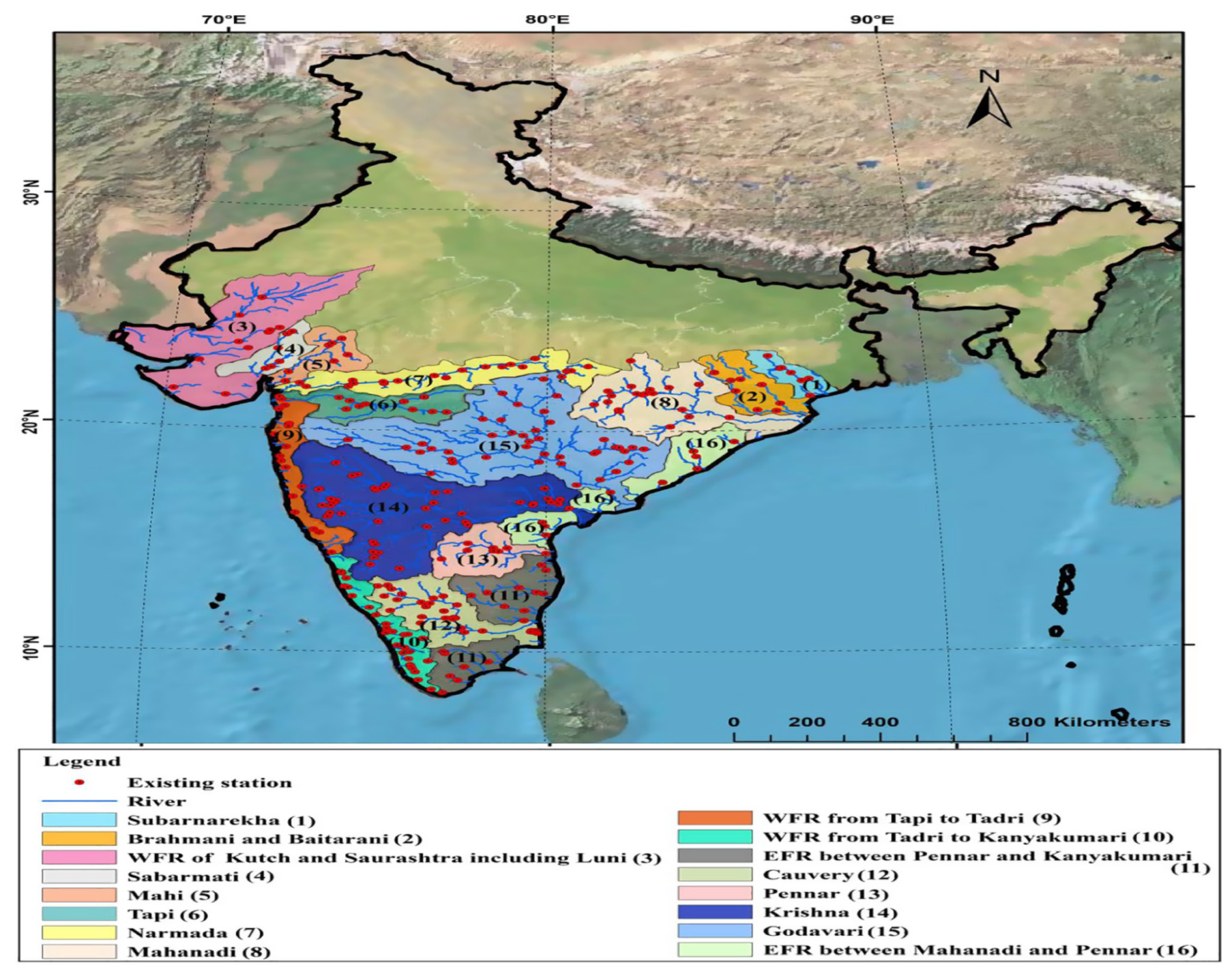

To improve streamflow prediction and rainfall-runoff modelling, entropy concepts are becoming more and more employed. Even with scarce data, maximum entropy principles can be used to create physically plausible probability distributions for hydrological variables (Sreeparvathy & Srinivas, 2020). The 16 river basins in the Indian peninsula, which make up roughly 52% of the nation's total land area and are home to more than half of its population, make up the case study area. A highly skewed distribution of water resources results from the region's characteristic monsoon climate, which is situated south of the Vindhya and Satpura mountain ranges (

Figure 1) and features significant geographical and temporal fluctuation in rainfall and temperature.

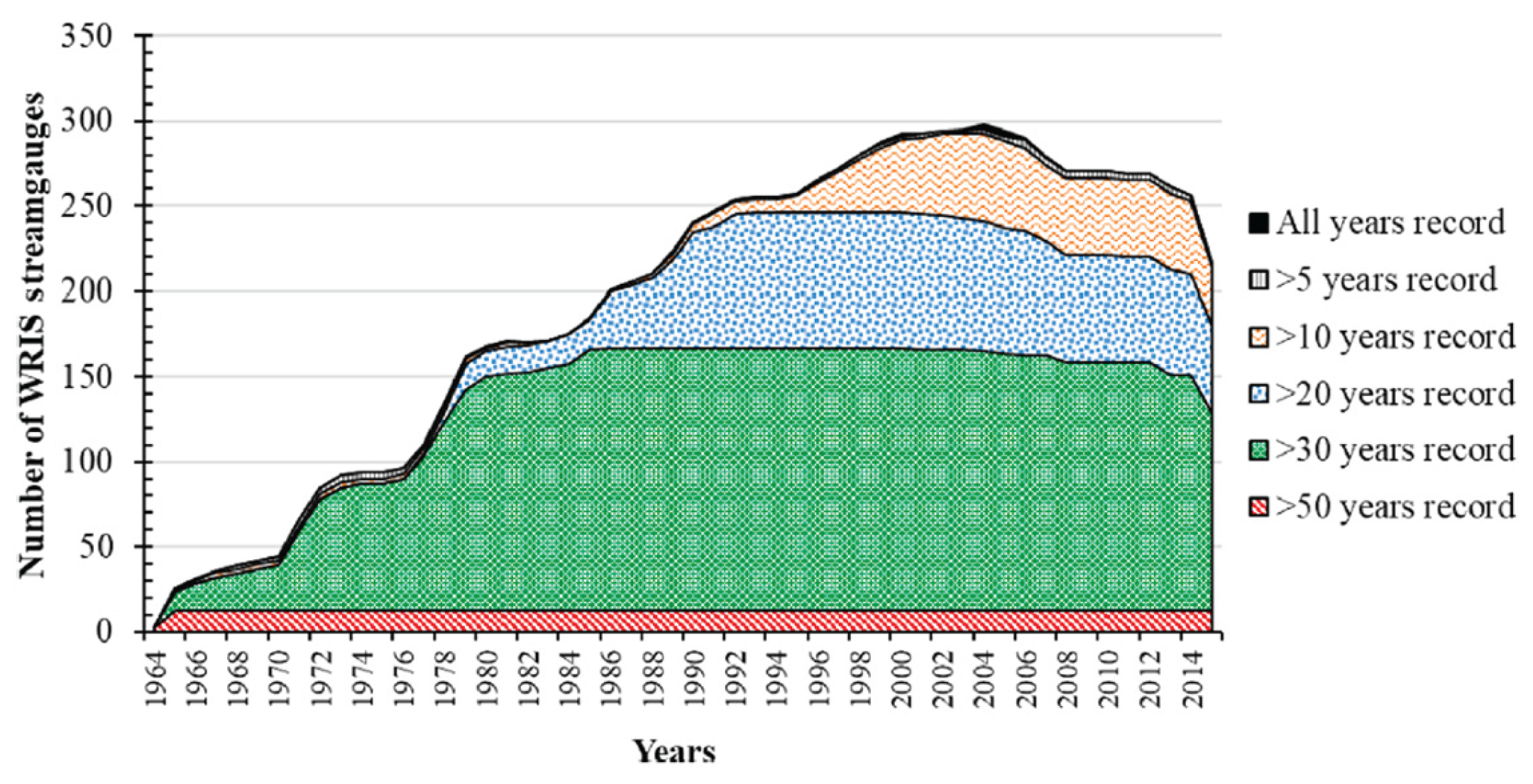

The full scenario of temporal record is visualized by

Figure 2 (c.f., Sreeparvathy & Srinivas, 2020)

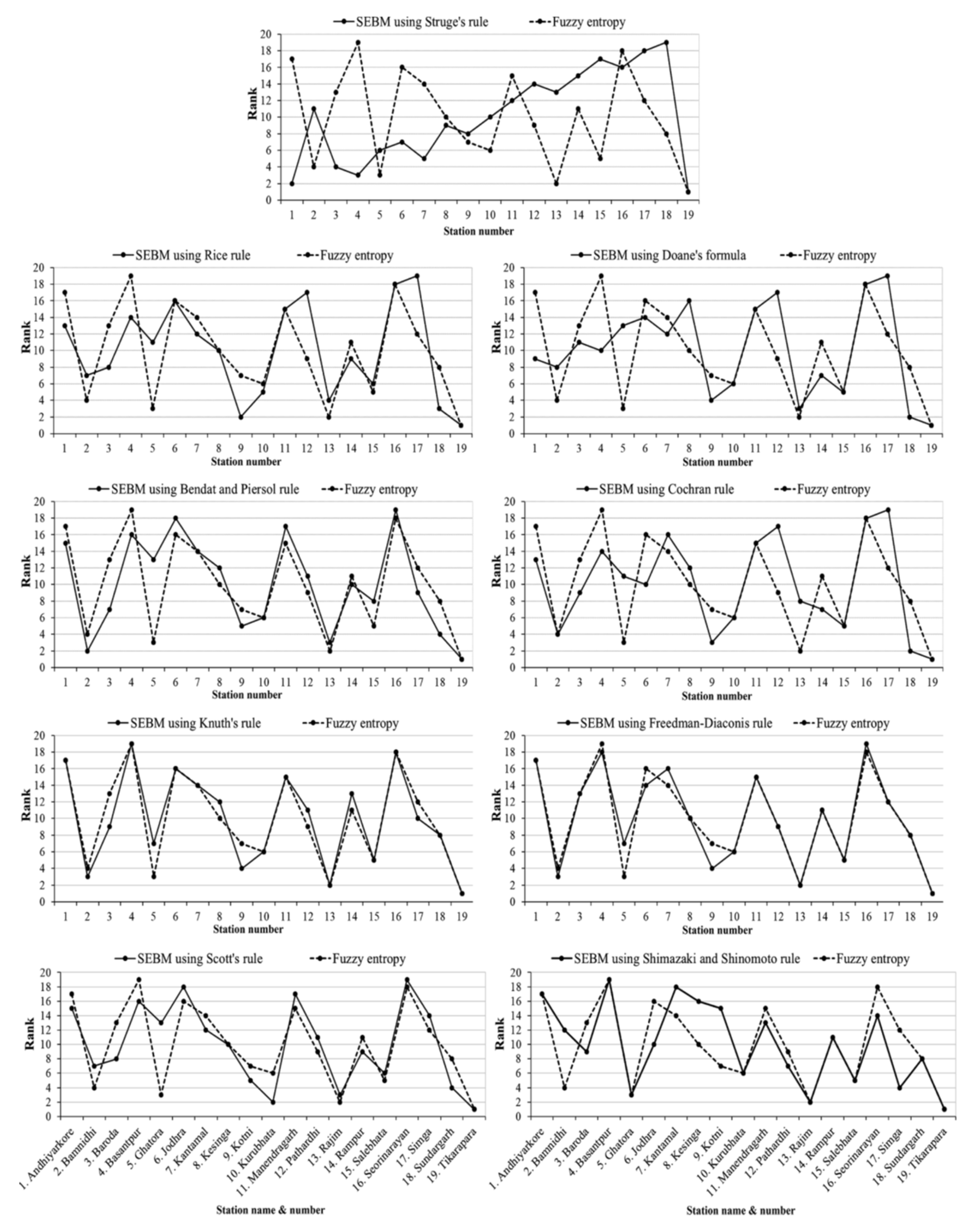

The generated data was compared by using fuzzy and Shannon entropy-based approach), and portrayed by

Figure 3 (Sreeparvathy & Srinivas, 2020).

Information-theoretic measures such mutual information and transfer entropy can assess the predictive capability of models, quantify the information transfer from inputs (e.g., rainfall, temperature) to outputs (streamflow), and detect significant constraints inside hydrological processes (Hermosilla-Albala et al., 2024; Jeung et al., 2024). Additionally used for streamflow prediction, particularly for identifying periodic and seasonal variations in time series data is entropy spectral analysis (Farajpanah et al., 2024; Saha et al., 2022).

3.3. Water Quality and Environmental Systems

Entropy has been used to examine the complexity and information content of data on water quality. Changes in entropy can denote changes in environmental health or the existence of pollution (Cui et al., 2024). Entropy can be used to design ideal water quality monitoring networks, pinpoint essential sampling sites, and evaluate the spatio-temporal variance of pollutants (Shi et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2024). The idea of water utility, a measure of water's usefulness, can also be related to entropy, suggesting that the degradation of water quality corresponds to an increase in entropy (Dehkordi et al., 2025).

3.4. Drought and Flood Analysis

Entropy offers strong instruments for describing spatio-temporal fluctuation and finding uniform zones in research on floods and droughts. Entropy, for instance, can be employed to assess drought intensity and length, therefore supporting regionalization initiatives for improved drought management (Pei et al., 2023; Ju et al., 2023). Similarly, in flood frequency analysis, entropy ideas can obtain flood probability distributions, therefore accounting for maximum uncertainty based on observed data (Tahroudi et al., 2023).

3.5. Regionalization and Parameter Estimation

Regionalization methods are especially vital when data is limited in unmeasured basins. By helping to pinpoint hydrological resemblance among catchments, entropy-based techniques enable the transfer of information or model parameters from gauged to ungauged areas (Guo et al., 2023). By designing objective functions maximizing the common information between observed and predicted variables, the Principle of Maximum Entropy can also be used in hydrological model calibration—possibly resulting in more robust parameter estimates and better uncertainty quantification (Pizarro et al., 2025).

4. Open Problems and Challenges in Entropic Hydrology

Although entropy modelling holds great promise for applications, there are several major open challenges and difficulties preventing its widespread adoption and more development in hydrology.

4.1. Physical Meaning and Interpretation of Entropy

One of the major difficulties is the obvious and steady physical interpretation of informational entropy in hydrological settings. Although entropy is a strong mathematical gauge of uncertainty, its clear translation into physical hydrological processes is not always easy (Koutsoyiannis et al., 2023). Is high entropy always indicative of disorder, or might it represent a complex, self-organizing system? One still-active area of study is the reconciliation of informational entropy with thermodynamic entropy, particularly in non-equilibrium hydrological systems (Jaime Gómez-Hernández et al., 2020). The findings obtained from entropy analysis could find it difficult to be entirely accepted among process-oriented hydrologists unless a more concrete physical foundation is established.

4.2. Data Requirements and Discretization Issues

Data discretization—which can greatly affect the final entropy values (Mageed, 2024e)—is often needed for entropy computations, especially for continuous variables. The selection of bin size or data partitioning technique can produce artifacts and biases, therefore difficult comparisons between several investigations or datasets. Although some discretization-invariant measures have been suggested (Santos et al., 2024), a commonly accepted and robust method of dealing with continuous hydrological data in entropy computations is still lacking. Reliable entropy estimation further calls for high-resolution and long-term hydrological data, therefore limiting their use in data-poor areas or for historical studies (Dembélé et al., 2020).

4.3. Computational Complexity and Scalability

Calculating multivariate and dynamic entropy measures for large, multi-dimensional hydrological datasets can be computationally intensive (Yan et al., 2025). Efficient algorithms and computational frameworks are needed as hydrological models and datasets increase in complexity and size (e.g., high-resolution remote sensing data, large ensembles of climate model outputs) to enable entropy analysis in practical, real-world applications. Additionally need to be considered are the difficulties of applying entropy computations to distributed hydrological models (Yaseen, 2023).

4.4. Selection of Entropy Measures and Constraints

There are several kinds of entropy (Shannon, Rényi, Tsallis, permutation entropy) with unique properties and sensitivities to data features (Mageed, 2024d; Mageed & Bhat, 2022; Amigó et al., 2023). Often there are no clear instructions on how to choose the suitable constraints for maximum entropy applications and on which entropy measure is most suited for a particular hydrological issue (Sreeparvathy & Srinivas, 2020). Choosing these policies and restrictions is subjective, which could produce varied opinions and perhaps conflicting outcomes.

4.5. Integration with Process-Based and Machine Learning Models

Though entropy presents a strong perspective for data analysis, its smooth incorporation with existing process-based hydrological models and developing machine learning (ML) approaches remains an ongoing difficulty. Hybrid modelling methods, which combine physics-based constraints with data-driven ones, are promising but call for careful consideration of how entropy could help to enable this synergy (Kim et al., 2023; Pizarro et al., 2025). How might entropy be used to inform model architecture, decrease model uncertainty, or enhance the interpretability of 'black-box' ML models? Some research shows that although ML models have great predictive performance, including physics-based limitations—even with entropy-based assessments—might be counterproductive if not well planned (Álvarez Chaves et al., 2025).

4.6. Addressing Non-Stationarity and Non-Linearity

Strong non-linear dynamics characterize hydrological systems naturally non-stationary (Kumari et al., 2021). Many traditional entropy models suppose stationarity, therefore restricting their utility to actual hydrological time series. For entropic hydrology to advance, it is imperative to create strong entropy measures that can properly capture time-varying information content, identify changes in system behaviour, and quantify non-linear dependencies (Koutsoyiannis et al., 2023; Pourmorad et al., 2024).

5. Next-Generation Entropic Hydrology: Future Directions

The above-mentioned difficulties provide rich ground for future investigation, hence clearing the path for a more strong, insightful, and generally applicable "next-generation" entropic hydrology.

5.1. Dynamic and Multi-Scale Entropy Analysis

Beyond stationary entropy statistics, future research will concentrate on multi-scale entropy, which studies information at various temporal and spatial resolutions (Yu et al., 2024; Santos et al., 2024), and dynamic entropy, which measures changes in information content across time. This will help one to better grasp how hydrological complexity develops, how data travels across scales (e.g., from catchment to regional or daily to annual), and how dominant processes change under different conditions (Koutsoyiannis et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023). Such methods might help locate key thresholds or tipping points in hydrology systems.

5.2. Entropy-Informed Machine Learning and AI Integration

The potential for entropy and machine learning (ML) working together is enormous. According to (Jeung et al., 2024), entropy can be a useful method for feature selection, which reduces dimensionality and increases model performance by identifying the most informative hydrological variables for machine learning models.

Model Evaluation and Uncertainty Quantification: Evaluate ML model performance using information-theoretic metrics that go beyond conventional error metrics to gauge how effectively models represent the underlying information structure (Pizarro et al., 2025). Readability of Black-Box Models: Utilise transfer entropy to gain insight into the causal links that intricate machine learning models learn, which will help you better understand how these models make decisions when hydrological forecasting (Tillman et al., 2022).

Data Augmentation and Anomaly Detection: Leverage entropy to identify data points with high information content for targeted data collection or detect anomalous behaviour in hydrological time series (Reichstein et al., 2019).

More physically consistent and understandable hydrological forecasts may result from hybrid models that incorporate regularisation terms or entropy-based limitations into machine learning frameworks.

5.3. Advanced Information-Theoretic Metrics and Network Analysis

Investigating sophisticated information-theoretic measures beyond the traditional Shannon entropy will be essential. Among these are:

Complex Network Theory: Using network analysis techniques, in which information flow (measured by transfer entropy) represents links and hydrological elements (such as sub-basins and monitoring stations) are nodes. This can show how hydrological systems are connected, hierarchical, and vulnerable (Ruddell et al ., 2023; Baumas & Bizic, 2023).

Information Bottleneck Method: A method for finding important drivers in complicated hydrological systems that compresses pertinent information from one variable while maintaining as much information as possible about another (Hu et al., 2024). Higher-order dependencies in hydrological systems can be revealed by measures that quantify the overall statistical reliance among several variables, such as multi-information and total correlation (Huang et al., 2023).

5.4. Bridging Informational and Thermodynamic Entropy

In hydrology, explicitly bridging the gap between informational and thermodynamic entropy is a crucial future direction. To do this, frameworks that can quantitatively link information flow and uncertainty metrics to mass mobility, physical energy dissipation, and irreversible processes within catchments must be developed (Jaime Gómez-Hernández et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2023). By combining statistical and physical concepts, this could offer a more comprehensive knowledge of hydrological dynamics.

5.5. Entropy in Climate Change Impact Assessment and Adaptation

In hydrological regimes, entropy modelling can be extremely important as climate change brings hitherto unheard-of non-stationarity and uncertainty. • Quantify Changes in Hydrological Complexity: Evaluate how climate change affects the complexity and information content of hydrological processes (e.g., increased unpredictability of extreme occurrences) (Allan et al., 2020).

Assess Adaptation methods: Under unpredictable conditions, evaluate the resilience and robustness of water management methods using entropy to find solutions that minimise vulnerability or maximise information gain (Volpi et al., 2024).

Bias correction and downscaling: Use maximum entropy principles to bias correct hydrological predictions or probabilistically downscale climate model outputs, producing believable future hydrological scenarios with quantifiable uncertainty (Chen et al., 2021).

5.6. Operationalization and User-Friendly Tools

More user-friendly software programs, standardised procedures, and strong application guidelines are required for entropy modelling to become a common tool in hydrological practice. To enable hydrologists and water resource managers to use entropy principles in their work, it will be crucial to provide open-source tools and educational materials.

6. Conclusions

For measuring complexity, information richness, and uncertainty in hydrological systems, entropy modelling provides a strong and adaptable framework. Its uses range from enhancing forecasting precision and streamlining monitoring networks to comprehending hydrological complexity and guiding the management of water resources. A logical foundation for deriving probability distributions from sparse data is provided by the Principle of Maximum Entropy, while information-theoretic metrics such as transfer entropy and mutual information shed light on causal links and dependencies.

There are still a lot of unresolved issues and obstacles, though. These include resolving data discretisation sensitivities, controlling computational complexity, elucidating the physical meaning of informational entropy, and creating precise rules for choosing suitable entropy measures and limitations. Furthermore, it takes careful thought and creative solutions to integrate entropy with both the mainstream process-based models and the emerging discipline of machine learning.

The future of entropic hydrology, often known as "next-generation entropic hydrology," is set to overcome these difficulties. Key directions include the development of dynamic and multi-scale entropy analyses, the deep integration of entropy with AI and machine learning for improved prediction and interpretability, the investigation of advanced information-theoretic metrics and network analysis, and a more explicit link between informational and thermodynamic entropy. As hydrological systems continue to encounter enormous stresses from climate change and human activity, careful application of entropy principles will be critical for building more robust, adaptive, and scientifically informed water resource management techniques. Entropy modelling can transform from a specialised field of study to a vital hydrological science foundation by adopting these developments, offering priceless insights into the complex dance of water on Earth.

References

- Allan, R.P.; Barlow, M.; Byrne, M.P.; Cherchi, A.; Douville, H.; Fowler, H.J.; Gan, T.Y.; Pendergrass, A.G.; Rosenfeld, D.; Swann, A.L.; Wilcox, L.J. Advances in understanding large-scale responses of the water cycle to climate change. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2020, 1472(1), 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez Chaves, M.; Acuña Espinoza, E.; Ehret, U.; Guthke, A. When physics gets in the way: an entropy-based evaluation of conceptual constraints in hybrid hydrological models. EGUsphere 2025, 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Amigó, J.M.; Rosso, O.A. Ordinal methods: Concepts, applications, new developments, and challenges—In memory of Karsten Keller (1961–2022). Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2023, 33(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumas, C.; Bizic, M. Did you say marine snow? Zooming into different types of organic matter particles and their importance in the open ocean carbon cycle. EarthArXiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Arsenault, R.; Brissette, F.P.; Zhang, S. Climate change impact studies: Should we bias correct climate model outputs or post-process impact model outputs? Water Resources Research 2021, 57(5), e2020WR028638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, C.; Dong, S. Application research on China’s logistics network structure: An overview. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2024, 27(8), 1277–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, M.F.; Hatefi, S.M.; Tamošaitienė, J. An Integrated Fuzzy Shannon Entropy and Fuzzy ARAS Model Using Risk Indicators for Water Resources Management Under Uncertainty. Sustainability 2025, 17(11), 5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, M.; Hrachowitz, M.; Savenije, H.H.; Mariéthoz, G.; Schaefli, B. Improving the predictive skill of a distributed hydrological model by calibration on spatial patterns with multiple satellite data sets. Water resources research 2020, 56(1), e2019WR026085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibeck, A., Shaocong, Z., Mei Qi, L., & Kraft, M. (2024). Research data supporting" A Simple and Efficient Approach to Unsupervised Instance Matching and its Application to Linked Data of Power Plants".

- Farajpanah, H.; Adib, A.; Lotfirad, M.; Esmaeili-Gisavandani, H.; Riyahi, M.M.; Zaerpour, A. A novel application of waveform matching algorithm for improving monthly runoff forecasting using wavelet–ML models. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2024, 26(7), 1771–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Han, H.; Nones, M.; Xu, W.; Liu, S. Information Entropy Theory-Based Optimizing of Gauge Networks for Hydrological Modelling—A Case Study in the Loess Plateau, China. In International School of Hydraulics; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023; pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hermosilla-Albala, N.; Silva, F.E.; Cuadros-Espinoza, S.; Fontsere, C.; Valenzuela-Seba, A.; Pawar, H.; Gut, M.; Kelley, J.L.; Ruibal-Puertas, S.; Alentorn-Moron, P.; Faella, A. Whole genomes of Amazonian uakari monkeys reveal complex connectivity and fast differentiation driven by high environmental dynamism. Communications Biology 2024, 7(1), 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lou, Z.; Yan, X.; Ye, Y. A survey on information bottleneck. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Shao, J.; Guo, W.; Li, W.; Zhu, J.; Fang, D. Hybrid machine learning-enabled multi-information fusion for indirect measurement of tool flank wear in milling. Measurement 2023, 206, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime Gómez-Hernández, J.; Chen, Z.; Zanini, A. Tracking back the source of contamination. In Book of Abstracts; Interpore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung, M.; Her, Y.; Baek, S.S.; Yoon, K. Sensitivity of hydrological machine learning prediction accuracy to information quantity and quality. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions 2024, 2024, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Singh, V.P.; Xu, P.; Zhang, A.; Wu, J.; Ma, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. An entropy and copula-based framework for streamflow prediction and spatio-temporal identification of drought. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2023, 37(6), 2187–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Garcia, M.; Black, T.A.; Johnson, M.S. Assessing the complementary role of surface flux equilibrium (SFE) theory and maximum entropy production (MEP) principle in the estimation of actual evapotranspiration. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 2023, 15(7), e2022MS003224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Montanari, A. Bluecat: A local uncertainty estimator for deterministic simulations and predictions. Water Resources Research 2022, 58(1), e2021WR031215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Iliopoulou, T.; Koukouvinos, A.; Malamos, N.; Mamassis, N.; Dimitriadis, P.; Tepetidis, N.; Markantonis, D. In search of climate crisis in Greece using hydrological data: 404 not found. Water 2023, 15(9), 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Srivastava, A.; Sahoo, B.; Raghuwanshi, N.S.; Bretreger, D. Identification of suitable hydrological models for streamflow assessment in the Kangsabati River Basin, India, by using different model selection scores. Natural Resources Research 2021, 30(6), 4187–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Izumida, Y. Thermodynamic efficiency of atmospheric motion governed by the Lorenz system. Physical Review E 2023, 108(4), 044201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A.; Bhat, A.H. Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. math 2022, 16(5), 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A.; Zhang, Q. An introductory survey of entropy applications to information theory, queuing theory, engineering, computer science, and statistical mechanics. In 2022 27th international conference on automation and computing (ICAC); IEEE, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A.; Zhang, Q. Formalism of the Rényian maximum entropy (RMF) of the stable M/G/1 queue with geometric mean (GeoM) and shifted geometric mean (SGeoM) constraints with potential geom applications to wireless sensor networks (WSNs). Electronic journal of computer science and information technology 2023, 9(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. Cosistency axioms of choice for Ismail’s entropy formalism (IEF) Combined with information-theoretic (IT) applications to advance 6G networks. European journal of technique (ejt) 2023, 13(2), 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. Entropy-based feature selection with applications to industrial internet of things (IoT) and breast cancer prediction. Big Data and Computing Visions 2024a, 4(3), 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. Entropic imprints on bioinformatics. Big Data and Computing Visions 2024b, 4(4), 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. Entropic Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Transfer. Adv Mach Lear Art Inte 2024c, 5(2), 01–08. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. On the Rényi Entropy Functional, Tsallis Distributions and Lévy Stable Distributions with Entropic Applications to Machine Learning. Soft Computing Fusion with Applications 2024d, 1(2), 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mageed, I.A. Towards An Info-Geometric Theory Of The Analysis Of Non-Time Dependent Queueing Systems. Risk Assessment and Management Decisions 2024e, 1(1), 154–197. [Google Scholar]

- Moraffah, R.; Sheth, P.; Karami, M.; Bhattacharya, A.; Wang, Q.; Tahir, A.; Raglin, A.; Liu, H. Causal inference for time series analysis: Problems, methods and evaluation. Knowledge and Information Systems 2021, 63, 3041–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Hao, L.; Fu, Q.; Ren, Y.; Li, T. Study on agricultural drought risk assessment based on information entropy and a cluster projection pursuit model. Water Resources Management 2023, 37(2), 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, A.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; Montanari, A. Combining uncertainty quantification and entropy-inspired concepts into a single objective function for rainfall-runoff model calibration. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions 2025, 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pourmorad, S.; Kabolizade, M.; Dimuccio, L.A. Artificial Intelligence Advancements for Accurate Groundwater Level Modelling: An Updated Synthesis and Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(16), 7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.; Roshni, T.; Berndtsson, R. Entropy based approach for precipitation monitoring network in Bihar, India. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2024, 51, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, F. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566(7743), 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddell, B.L., Clark, M., Driscoll, J.M., Gochis, D., Gupta, H., Huntzinger, D., Kirchner, J.W., Larsen, L., Loescher, H.W., Luo, Y., & Maxwell, R. (2023). Calling for a National Model Benchmarking Facility.

- Saha, S.; Sarkar, D.; Mondal, P. Efficiency exploration of frequency ratio, entropy and weights of evidence-information value models in flood vulnerability assessment: a study of Raiganj subdivision, Eastern India. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2022, 36(6), 1721–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L., Satolo, L.F., Oyarzabal, R., Escobar-Silva, E., Diniz, M., Negri, R., Lima, G., Stephany, S., Soares, J., Duque, J., & Saraiva-Filho, F. (2024). Machine Learning-based Hydrological Models for Flash Floods: A Systematic Literature Review.

- Schroers, S.; Eiff, O.; Kleidon, A.; Scherer, U.; Wienhöfer, J.; Zehe, E. Morphological controls on surface runoff: an interpretation of steady-state energy patterns, maximum power states and dissipation regimes within a thermodynamic framework. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2022, 26(12), 3125–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, H.; Kumar, B. One-dimensional velocity distribution in seepage bed open channels using Tsallis entropy. ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part A: Civil Engineering 2023, 9(4), 04023030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Han, J.; Yang, X. Water richness evaluation of coal roof aquifers based on the game theory combination weighting method and the topsis model. Mine Water and the Environment 2024, 43(4), 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeparvathy, V.; Srinivas, V.V. A fuzzy entropy approach for design of hydrometric monitoring networks. Journal of Hydrology 2020, 586, 124797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xue, Q.; Xing, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, F. Remote Sensing Image Interpretation for Coastal Zones: A Review. Remote Sensing 2024, 16(24), 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahroudi, M.N., Ramezani, Y., De Michele, C., & Mirabbasi, R. (2023). Development of the entropy theory for wind speed monitoring by using copula-based approach.

- Tillman, F.D.; Day, N.K.; Miller, M.P.; Miller, O.L.; Rumsey, C.A.; Wise, D.R.; Longley, P.C.; McDonnell, M.C. A review of current capabilities and science gaps in water supply data, modeling, and trends for water availability assessments in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Water 2022, 14(23), 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stan, J.T., II; Simmons, J. Plato’s Wonder and Hydrology. In Hydrology and Its Discontents: Contemplations on the Innate Paradoxes of Water Research; Springer International Publishing; Cham, 2024; pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Verykokou, S.; Ioannidis, C. Image Matching: A Comprehensive Overview of Conventional and Learning-Based Methods. Encyclopedia 2025, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, E., Grimaldi, S., Aghakouchak, A., Castellarin, A., Chebana, F., Papalexiou, S.M., Aksoy, H., Bárdossy, A., & Ragno, E. (2024). The legacy of STAHY.

- Yan, D.; Wang, Y.; Qin, D.; Zhang, J. Hydrological geography: Theoretical framework, research progress, and future development directions. Geographical Research Bulletin 2025, 4, 186–224. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, Z.M. A new benchmark on machine learning methodologies for hydrological processes modelling: A comprehensive review for limitations and future research directions. Knowledge-Based Engineering and Sciences 2023, 4(3), 65–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, W.; Yang, B.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Fu, G. Periodic distribution entropy: unveiling the complexity of physiological time series through multidimensional dynamics. Information Fusion 2024, 108, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).