1. Introduction

Entropy, one of the fundamental concepts in physics, plays a pivotal role in the study of complex climate systems. In its thermodynamic formulation, it describes the degree of disorder and energy dissipation [

1,

2,

3] while in Shannon’s information theory, it serves as a quantitative measure of uncertainty and complexity in data such as temperature and precipitation time series [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Contemporary research suggests a significant relationship between physical and informational entropy, opening new avenues for the quantitative assessment of climate variability [

7,

8].

The Earth’s climate system operates as an open, far-from-equilibrium system in which temperature and pressure gradients drive atmospheric and oceanic circulations [

1,

9,

10]. These processes lead to the transport of heat and moisture and to the production of entropy

—through energy dissipation, phase transitions, and diffusion [

11]. Shannon entropy enables the evaluation of the system’s unpredictability, and its spatiotemporal analysis makes it possible to identify regions particularly susceptible to extreme weather phenomena [

12,

13,

14].

In this study, we analyze spatial fields and entropy fluxes computed from monthly temperature and precipitation data, employing the formalism of gradients and divergence [

1,

2,

15]. This approach allows us to capture the directional transport of climate information and to identify local structures of order and chaos that remain undetectable through conventional statistical methods [

11,

14,

16]. The spatial variability of entropy gradients reflects dominant directions of climate variability flow and may indicate external influences such as the impact of the Atlantic Ocean or continentality gradients [

17,

18,

19].

The correlation of entropy flux patterns with large-scale atmospheric indices (such as the NAO and AO) enables the linking of local variability patterns with global-scale phenomena [

20,

21,

22]. Regions with elevated entropy relative to their surroundings act as variability generators, whereas areas with low divergence may function as stabilizers of the system, sensitive to external disturbances. Such spatial differentiation enables the identification of entropy sources, sinks, and informational gaps

—elements crucial for climate monitoring and forecasting [

10,

12,

23].

Classical analytical methods often fail to capture the nonlinear and stochastic aspects of atmospheric dynamics, particularly in Europe, where oceanic, continental, and Arctic influences converge [

24,

25]. The integration of information theory with phase space analysis, copula-based modeling, and vector analysis offers a refined framework for identifying these complex interactions [

26,

27,

28]. The present study, grounded in prior work on thermodynamic entropy, chaotic dynamics, and copula theory, proposes a new methodological framework adapted to the climatic conditions of Europe [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The use of copula functions to model asymmetric dependencies between temperature and precipitation, along with the analysis of climate information transport, constitutes an innovative contribution to the development of tools for interpreting and forecasting climate variability [

28,

33].

2. Data Preparation for Analysis

The analysis presented in this study is based on high-quality gridded data published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA [

34,

35,

36]. The study area spans approximately 5,570 km × 4,050 km, covering latitudes from −10° to 40° and longitudes from 35° to 72°. For the purposes of this research, a uniform spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° was applied consistently across all computations. The dataset comprises monthly mean temperatures and total monthly precipitation for the period 1901

–2010 [

34,

37]. For each grid cell, individual time series of temperature and precipitation were extracted and served as the basis for subsequent analyses grounded in informational entropy.

The NOAA data were utilized at their original resolution, without re-interpolation or grid rescaling. A major reason for selecting this dataset was its temporal and spatial homogeneity. Both temperature and precipitation fields were developed using standardized interpolation algorithms and quality control procedures, applied consistently by the same institution. This ensures a high level of data integrity and facilitates comparability across regions and time periods.

To ensure the reliability of long-term trend analyses, NOAA datasets are routinely verified and homogenized. This includes statistical identification of anomalies, data gaps, and inconsistencies, as well as cross-validation with ground-based observations and satellite products [

35,

36,

38,

39]. As a result, the NOAA dataset provides a stable and trustworthy foundation for detecting climate variability signals associated with entropy flow, as well as for analyzing the spatial directions of climate information transport.

3. Methodology

This study investigates the relationships between the structure of informational entropy and extreme weather phenomena, with a particular focus on maximum temperatures and minimum precipitation totals [

40,

41]. The approach is based on the analysis of monthly entropy values and their spatial gradients (entropy potential) across a grid covering the European domain [

2,

12,

21,

42]. For each grid point, monthly values of informational entropy were calculated, derived from the joint distributions of atmospheric variables

—namely temperature and precipitation [

18,

43]. Additionally, for each month, the spatial gradient of entropy was computed and interpreted as a vectorial entropy potential, with its magnitude (|∇Entropy|) serving as a proxy for local atmospheric variability and instability. The direction and rate of change in uncertainty across space are defined by the entropy gradient vector (∇Entropy) [

44,

45].

The primary objective of the analysis was to determine whether statistically significant relationships exist between entropy levels and their spatial dynamics, on one hand, and extreme values of maximum/minimum temperature and precipitation, on the other, at the same geographic locations. Three types of relationships were examined: (1) between the entropy value (Entropy) and weather extremes, (2) between the entropy potential (|∇Entropy|) and extremes, and (3) between the temporal derivative of entropy and extremes [

41,

44].

The first approach tested whether higher uncertainty levels (greater entropy) at a given location correspond with increased risk of high temperatures or drought. A positive correlation between entropy and maximum temperature would suggest that regions with higher variability are more prone to experiencing extreme heat events. Conversely, a negative correlation between entropy and minimum precipitation totals would imply that higher uncertainty favors the occurrence of severe droughts [

24,

46,

47].

The second approach focused on the analysis of the entropy gradient, interpreted as the rate and direction of spatial entropy changes. The magnitude of the gradient vector (|∇Entropy|), or entropy potential, was used to identify regions of pronounced spatial instability that may serve as initiation zones for extreme events. The analysis thus examined whether sharp spatial variations in entropy are linked to the occurrence of extreme temperature and precipitation values [

44,

48,

49].

All correlations were computed using two variants: temporal and seasonal–spatial. In the temporal analysis, for each grid point, the Spearman correlation was calculated between the 12-month entropy or entropy gradient series and the corresponding monthly values of weather extremes. The resulting correlation coefficient indicated the strength and direction of the relationship between monthly entropy fluctuations and variations in extreme weather events.

A high positive temporal correlation signified that months with elevated entropy potential coincided with months of extreme conditions (e.g., heatwaves), while a high negative correlation indicated an inverse relationship

—i.e., that increased local instability was associated with lower extreme values, such as droughts. In the seasonal

–spatial variant, spatial correlations were examined within each month separately. Spearman correlations were computed between the spatial distribution of entropy (or entropy gradients) and the spatial distribution of weather extremes for a given month [

50,

51]. This analysis addressed whether, during a given season, areas with higher entropy potential also exhibited a greater risk of extreme weather. These spatial correlations provided insight into the general seasonal

–spatial structure of the relationship between climate variability and extremes [

52].

To enhance the reliability of the results, the bootstrap method was applied. Repeated random sampling with replacement (1,000 iterations) yielded distributions of correlation coefficients and allowed for the assessment of their statistical significance. Based on these distributions, mean Spearman correlation values at a 5% significance level were computed, enabling an evaluation of the robustness of the findings [

12,

53,

54].

The results were presented as spatial maps, including distributions of entropy, trends in entropy and entropy potential, temporal and seasonal–spatial correlation maps, and visualizations of entropy gradient streamlines. The streamlines indicated trajectories along which uncertainty propagates spatially—offering potential prognostic value. Particularly promising were the findings from the entropy gradient analysis, which pointed to the existence of spatial mechanisms that may initiate extreme weather events. Strong local entropy gradients may signal that the atmospheric system is approaching bifurcation thresholds that lead to more chaotic states.

4. Distribution Fitting

The methodology presented in this study is based on bivariate copula functions, which offer a coherent and statistically justified approach to modeling dependencies between random variables with arbitrary marginal distributions. This framework allows for the decoupling of marginal modeling from dependency structure modeling, thereby enhancing both flexibility and interpretability of the results.

The analytical process begins with the estimation of marginal distribution parameters using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method. MLE ensures estimator efficiency and consistency under standard regularity conditions. For each candidate marginal distribution, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is applied to objectively select the best-fitting model, balancing model complexity against data fit [

6,

55].

The selected marginal distributions are subsequently transformed into the uniform space using their respective cumulative distribution functions (CDFs), a standard step in constructing copula functions. Next, the parameters of the selected copula families (e.g., Clayton, Gumbel, Frank, Gaussian, Student-t) are estimated, also using the MLE method [

31,

56,

57]. This step enables a full characterization of the dependence structure, independently of the marginal distributions.

Among the fitted copulas, the one that best reproduces the observed dependencies in the data is selected, again using the AIC. This ensures the entire process is grounded in comparable and statistically robust measures of goodness-of-fit, eliminating arbitrariness in the choice of both margins and dependency structures. Such a methodology adheres to the standards of modern probabilistic modeling, integrating marginal and joint characteristics, and proves particularly useful in meteorological, hydrological, and financial applications.

Importantly, given a sufficiently large sample size and careful selection of candidate marginal and copula functions, this procedure enables not only the accurate description of dependencies but also the prediction of extreme events and the assessment of joint risks associated with their co-occurrence. The framework thus constitutes a coherent and calibratable approach for constructing bivariate probabilistic models with strong statistical foundations.

4.1. Marginal Distributions

The modeling of Shannon entropy in this study

relies on temperature and precipitation data. For each spatial grid cell,

marginal distributions were analyzed separately for monthly mean temperatures

and monthly total precipitation values.

The following distributions were considered as candidates for marginal fitting (see

Table 1) [

57]:

Each of these distributions was fitted using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation method, supplemented by ADT tests, and the optimal model selection was based on AIC values. This selection process accommodates local climatic variability and the differing characteristics of temperature and precipitation across various regions of Europe.

Table 1.

Analyzed distribution forms for temperature and precipitation variables [

57].

Table 1.

Analyzed distribution forms for temperature and precipitation variables [

57].

| Distribution Name |

Mathematical Form |

Distribution Parameters |

No eq.. |

| Generalized Extreme Value |

for >0 and |

-- location parameter, scale parameter and shape parameter |

(1) |

| Normal |

|

x –random variable, standard deviation, and mean |

(2) |

| Lognormal |

for |

x –random variable and distribution parameters |

(3) |

| Weibull |

|

- random variable, standard deviation, and mean |

(4) |

| Gamma |

|

- random variable, distribution parameters, and the Gamma function |

(5) |

| Extreme Value |

|

-- location parameter, scale parameter |

(6) |

| Nakagami |

for |

– shape parameter, scale parameter |

(7) |

4.2. Bivariate Copula Functions

Due to their flexibility in coupling arbitrary marginal distributions within multivariate probability structures and their favorable computational properties, copula theory was employed in this study [

58,

59,

60]. The selection of a specific copula function

—analogous to the procedure for choosing marginal distributions

—was based on a predefined set of bivariate copulas: Gaussian, Clayton, Frank, and Gumbel (

Table 2), with the final choice determined using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [

33,

60,

61,

62]. The Gaussian copula assumes symmetric dependence between variables, which renders it suboptimal for modeling the frequently observed asymmetric and nonlinear relationships between precipitation and temperature under European climatic conditions. In contrast, the Clayton copula captures strong dependencies in the lower tail of the distribution, which is particularly relevant for analyzing phenomena such as droughts

—that is, the simultaneous occurrence of extremely low precipitation and high temperatures.

Alternative copula functions, such as the Gumbel copula (favoring upper-tail dependence) or the Frank copula (appropriate for moderate, symmetric correlation), exhibit lower suitability for the analyzed data due to their inability to capture the asymmetric dependency structures characteristic of extreme events. The selected set of copula functions was well-suited to the empirical characteristics of the temperature and precipitation data, allowing for precise modeling of their joint variability, including cases of extreme co-occurrence.

5. Shannon Entropy as a Measure of Climate Information

Shannon entropy, though originally derived from information theory, is widely applied in environmental and climate data analyses as a nonparametric measure of uncertainty, disorder, and variability in probability distributions. In climatological literature, informational entropy has been successfully used to analyze seasonal and spatial climate variability, as well as to detect shifts in weather regimes. In the present approach, emphasis is placed on the empirical evaluation of entropy’s evolution across time and space as an indicator of local climate instability—without requiring reference to an external or idealized distribution [

63]. Defining such a “reference” distribution can be challenging, if not impossible, in the context of complex and nonlinear atmospheric processes. Under conditions of high meteorological variability and spatial heterogeneity, adopting an arbitrary reference distribution may lead to ambiguous or misleading interpretations.

For this reason, a self-contained approach based on empirical entropy was adopted. It enables tracking the degree of order in weather data without relying on additional model assumptions, thereby enhancing the method’s universality and robustness against errors arising from incorrect distributional specifications. In informational terms, an increase in Shannon entropy reflects a higher level of randomness and complexity in the distribution of climate variables, which directly translates into reduced predictability of weather conditions and, potentially, greater vulnerability of the system to extreme events. Thus, the use of entropy as an indicator for analyzing climate variability aligns with the growing interest in nonparametric measures of uncertainty that allow for the assessment of irregularities and risk within a dynamically changing climate system.

Shannon entropy quantifies the uncertainty associated with predicting the value of a random variable [

5,

27,

64]. It is calculated from the estimated probability distribution, and the accuracy of this estimate directly influences the reliability of the entropy computation. An improperly selected or poorly fitted distribution may result in erroneous entropy values, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about the underlying climate structure.

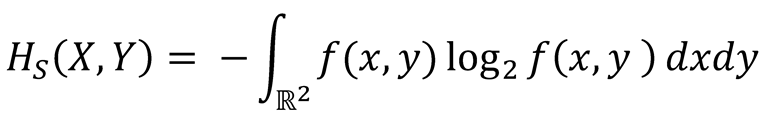

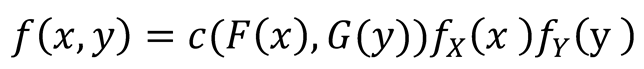

The formula for Shannon entropy of a continuous bivariate random variable

, with joint probability density function

, is defined as [

26,

65,

66]:

Here, is the joint PDF of the bivariate distribution derived from the copula and marginals. Marginal PDFs and . Copula density , which is derived from the zbioru postaci różnych copula.

The formula for the joint PDF becomes:

Use the definition:

to estimate the entropy as the negative mean of the log joint PDF.

In discussing units of Shannon entropy for

continuous distributions, the results are typically expressed in units of

information—nats (when

natural logarithms are used) or bits

(when base-2 logarithms are used). The choice of unit depends on analytical

conventions and the logarithmic system employed [12].

To preempt known criticisms and limitations

associated with the use of Shannon entropy, this study was designed with

methodological rigor. Measures implemented included:

standardization of measurement units across the

entire dataset,

consistent estimation of marginal distribution

parameters using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method,

and uniform discretization procedures for all input

data.

The selection of both marginal distributions and

copula functions was guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), allowing

for an objective assessment of model fit under consistent modeling assumptions.

These methodological safeguards ensured the integrity of the entire procedure,

aligning it with the rigorous standards required in climate data

analysis—particularly in the context of studying extreme weather events and

their relationship to informational measures of uncertainty, such as entropy.

6. Entropy Fluxes as a Tool for Spatiotemporal Analysis of Climate Variability

In the analysis of extreme weather phenomena—such

as heatwaves, droughts, or flash floods—information-theoretic metrics,

particularly informational entropy, are increasingly being employed [45,67]. The proposed approach extends classical

entropy analysis by incorporating field-based aspects: spatial gradients,

divergence, and the associated entropy flux [68].

The introduction of operators known from continuum physics (such as ) enables a mathematical representation of

informational flows between adjacent cells of the analytical grid [69]. This serves as a foundation for detecting

sources and sinks of climate variability. In particular, extreme events may be

preceded by changes in the informational structure of the atmospheric system,

whose spatiotemporal patterns can be captured through the analysis of entropy

fluxes [15,70].

Informational entropy is not a classical energy

function but rather a measure of informational disorder—making its diffusion

conceptually different from classical heat diffusion. The interpretation of

“information flux” as the spatial derivative of entropy is metaphorical yet

statistically valid, provided it is understood as a representation of

statistical structure, rather than a literal physical energy transfer. It is

essential to emphasize that in the context of “climate information,” the term

refers to the statistical structure of weather variability, not to concrete

datasets [71].

This study presents a framework based on the

spatiotemporal analysis of informational entropy distributions aimed at

understanding the dynamics of extreme climate events. Each geographic grid cell

(with a resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°) is assumed to hold a value of entropy , calculated from meteorological variables

describing local conditions. This entropy can be interpreted as a measure of

uncertainty or complexity of the climatic regime at a given location and time.

The spatial gradient vector of entropy, , indicates the direction and intensity of uncertainty change

across space, while its orientation reveals the direction in which structural

changes in information propagate.

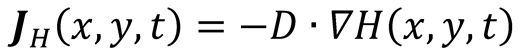

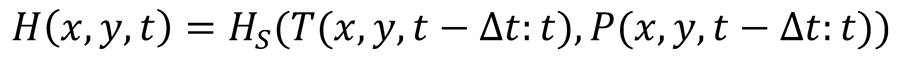

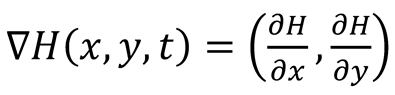

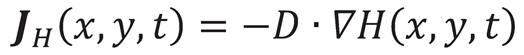

The entropy flux is then defined as:

representing a hypothetical flow of climate information between neighboring cells, analogous to diffusion mechanisms in physics. The divergence of this flux,

allows the identification of areas that act as sources or sinks of variability, which can be critical in detecting spatial dynamic regimes. This formalism is grounded in classical field theory and employs well-established mathematical tools of vector calculus (gradient, divergence, Laplacian). Applying this methodology to meteorological data enables the identification of regions with elevated instability, which may serve as precursors to extreme weather events.

In particular, the temporal derivative of entropy,

, serves as an indicator of local atmospheric system dynamics, where sharp increases may signal impending destabilization, such as intense precipitation or heatwaves. This approach effectively integrates classical concepts of information with climate process analysis and introduces a novel dimension to the detection and prediction of environmental hazards [

44].

6.1. The Informational Entropy Field

For the informational entropy function derived from the bivariate distribution of temperature and precipitation variables at a given spatial point , the time-window-based estimate can be expressed as:

For each grid cell with geographical coordinates at time , the concept of the spatial entropy gradient vector is introduced as:

where denote partial spatial derivatives of entropy along the west–east and south–north axes, respectively. This gradient reflects both the direction and intensity of local informational complexity changes in space. The entropy flux vector is defined analogously to classical diffusion:

where is the entropy diffusion coefficient, which may be treated either as a fixed empirical constant or as a function of local environmental conditions.

Further analysis relies on the divergence operator; sources and sinks of entropy in space are identified via the divergence of the entropy flux vector:

When , positive divergence values indicate areas (grid cells) acting as sources of information, or generators of variability.

When ,, negative divergence values indicate absorbers of variability, associated with relative atmospheric stability.

6.2. Relationship with Weather Extremes

Climatic extremes can be analyzed through the lens of local entropy stability. Stability is quantified by examining temporal changes in entropy:

Persistently low entropy values with weak spatial gradients suggest a stable weather regime—a potential predictor of droughts or heatwaves. Conversely, a sharp increase in the entropy time derivative signals regime destabilization, serving as a predictor of floods or severe storms.

The concept of entropy flux offers a novel perspective on climatic processes as a dynamic system of information exchange between neighboring regions. Areas with strong positive divergence may indicate localized instabilities conducive to extreme events—such as the initiation of convective storms or surface overheating under weak circulation conditions. In contrast, regions with negative divergence may correspond to stabilizing zones, for example, persistent high-pressure systems that sustain stable weather conditions.

This spatial differentiation enhances understanding of which regions act as sources or sinks of variability over a given period, with direct implications for risk assessment of extreme weather events.

Beyond spatial aspects, the

temporal derivative of entropy provides insight into the

stability of local weather regimes. An increase in this derivative can be interpreted as a signal of

destabilization and growing

unpredictability of the system—conditions that often precede the onset of climatic extremes. The combined assessment of spatial entropy gradients and the temporal evolution of entropy and its derivatives delivers a

more comprehensive picture of atmospheric system dynamics [

72]

.

7. Statistical Tests Used

To assess trends in Shannon entropy for both precipitation and temperature, the bootstrap resampling technique was employed to generate multiple statistical realizations and to estimate stable entropy values. For each iteration, a separate estimation of the marginal distribution parameters was performed, followed by the construction of a joint distribution using copula functions.

The characteristics and patterns of entropy trends were analyzed using the Mann

–Kendall test (MKT), a nonparametric statistical test widely used in climate change studies [

73,

74]. Trends were evaluated at a 5% significance level. In addition, the Pettitt test (PCPT) was applied to detect changepoints in the time series of entropy. This test was also conducted at a 5% significance level.

If a changepoint was confirmed at this level of significance, the time series was divided into subsequences, each of which was then reanalyzed for trends using the Mann

–Kendall test. In cases where no changepoint was detected, the test was applied to the entire sequence [

50,

53,

75].

To quantify the strength of the trend, a nonparametric slope estimator proposed by Sen and extended by Hirsch was used, which calculates the median of pairwise changes over time [

76,

77,

78]. This approach allowed not only for detecting the presence of a trend but also for determining its direction and magnitude.

Marginal distributions describing temperature and precipitation for each analyzed sequence were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method, assessed with the Anderson–Darling test (ADT), and the optimal model was selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

In this study, the Pettitt test was specifically applied to identify changepoints in the time series of Shannon entropy derived from monthly precipitation totals and average monthly temperatures. PCPT, based on a test statistic compared against a critical value, allowed for determining whether the null hypothesis of no abrupt change could be rejected [

75]. This method is widely used in climatological and hydrological analyses due to its robustness in detecting structural changes in environmental time series [

12].

8. Results of the Analyses and Discussion

To accurately assess trends in informational entropy for precipitation and temperature, the bootstrap resampling method was employed to generate multiple realizations of Shannon entropy. The entropy calculations were based on the bivariate joint probability distribution of temperature and precipitation (

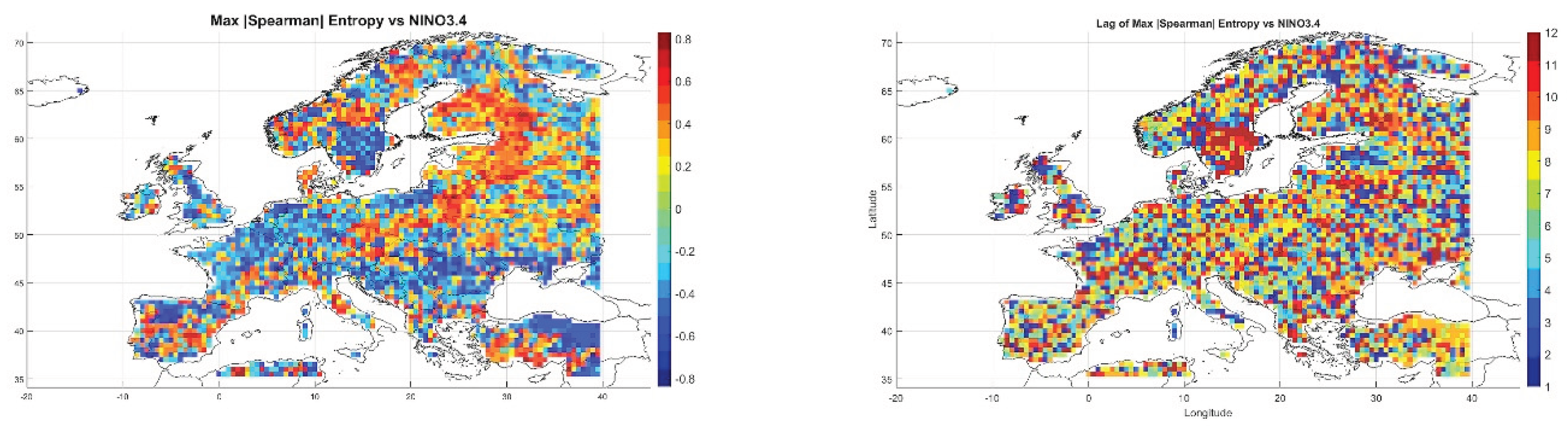

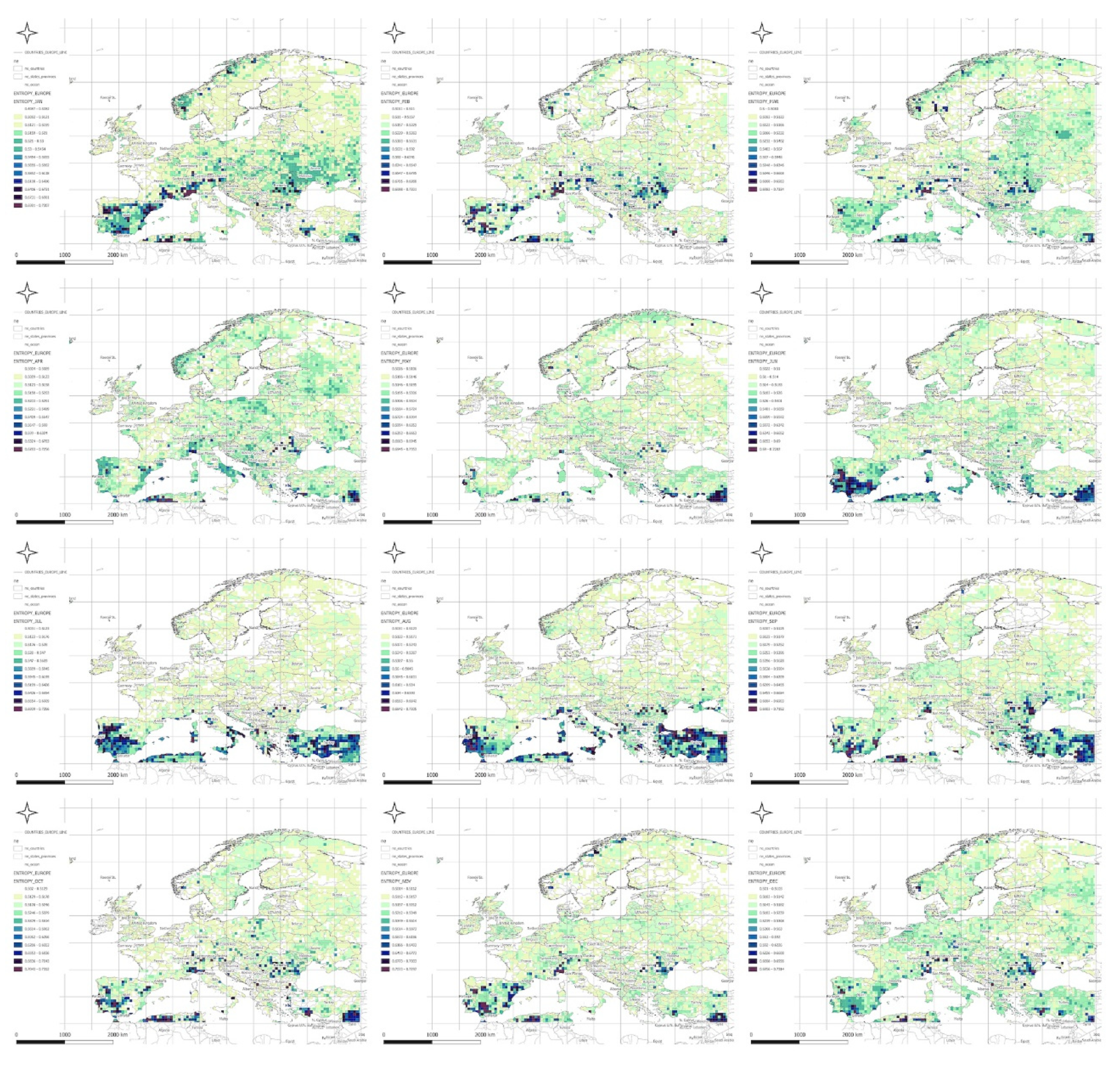

Figure 1).

From the resulting time series of entropy values, seasonal trends were computed, and their statistical significance was evaluated using the Mann–Kendall test (MKT) at a 5% significance level. Additionally, to detect potential changepoints in the trend trajectories, the Pettitt test (PCPT) was applied, also at a 5% significance level.

If the presence of a changepoint was confirmed, each newly segmented subsequence was analyzed separately for trends using the MKT. If no changepoint was identified, the trend was assessed over the entire sequence.

The results were presented graphically, providing a clearer and more precise visualization of changes in entropy values and the evolution of their trends. For comparative purposes, the Shannon entropy values were normalized to the range (0, 1). The original entropy range—computed via integration from the joint bivariate probability distribution based on a sample size of 70 (T, P) pairs—spanned from 0 to 12.259 bits. This normalization allowed for consistent interpretation of spatial and temporal patterns of variability.

The meteorological entropy analysis, conducted separately for each calendar month, was based on long-term data from 1901 to 2010. This allowed for the averaging of seasonal patterns of weather variability across Europe. Calculations for each of the 40 analyzed years were based on 70-year seasonal time series: for the year 1971, the period 1901–1970 was used; for 1972, the period 1902–1971; and so on, up to 2010, for which data from 1941–2010 were used.

Each of the 12 panels in the graphical analysis corresponds to a calendar month, from January (top left) to December (bottom right). The color scale reflects the magnitude of entropy: from the lowest values (light yellow – low weather variability) to the highest (dark purple – high variability).

In January, low entropy values dominate across Northern Europe, indicating stable and predictable winter conditions. Elevated entropy values appear locally in the south—particularly over the Iberian Peninsula, southern France, and the Mediterranean regions—where precipitation variability is higher.

In February and March, similar patterns persist, although the zone of increased entropy gradually shifts toward Central Europe. April shows growing spatial differentiation, particularly over the Alps, the Balkans, and Southeastern Europe. In May, a general decline in entropy is observed, reflecting the typical springtime stabilization of the atmosphere.

Entropy peaks in June and July, especially across Southeastern Europe—including the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, and Northern Africa—likely linked to intensified convective storm activity and localized precipitation events. In August, high entropy zones shift northward, covering parts of southern Germany, Poland, and Ukraine.

In September, variability moderates in Western Europe, while remaining elevated in continental regions. October brings a further decline in entropy over Northern and Central Europe, though high values persist in the Mediterranean basin. In November, entropy decreases across most regions, remaining moderate only in Southeastern Europe. December, like January, is marked by low entropy across nearly all of Europe, associated with dominant, stable winter synoptic patterns.

The observed spatial patterns of entropy reveal a pronounced seasonal rhythm: minimal variability during winter and peak variability during summer, especially in the southern and southeastern parts of the continent. High entropy in the warmer months reflects the intensification of convective processes and increased atmospheric instability.

Mountainous regions—such as the Alps and Carpathians—exhibit elevated entropy values throughout much of the year, indicative of complex orographic conditions and local microcirculations. In contrast, the Mediterranean coasts show high variability particularly in autumn and winter, associated with episodic Mediterranean cyclones. Scandinavia and Northeastern Europe display the lowest entropy values for most of the year, confirming their stable and strongly seasonal climatic character.

9. Trend and Seasonal Variability of Shannon Entropy in the Context of Climate Change

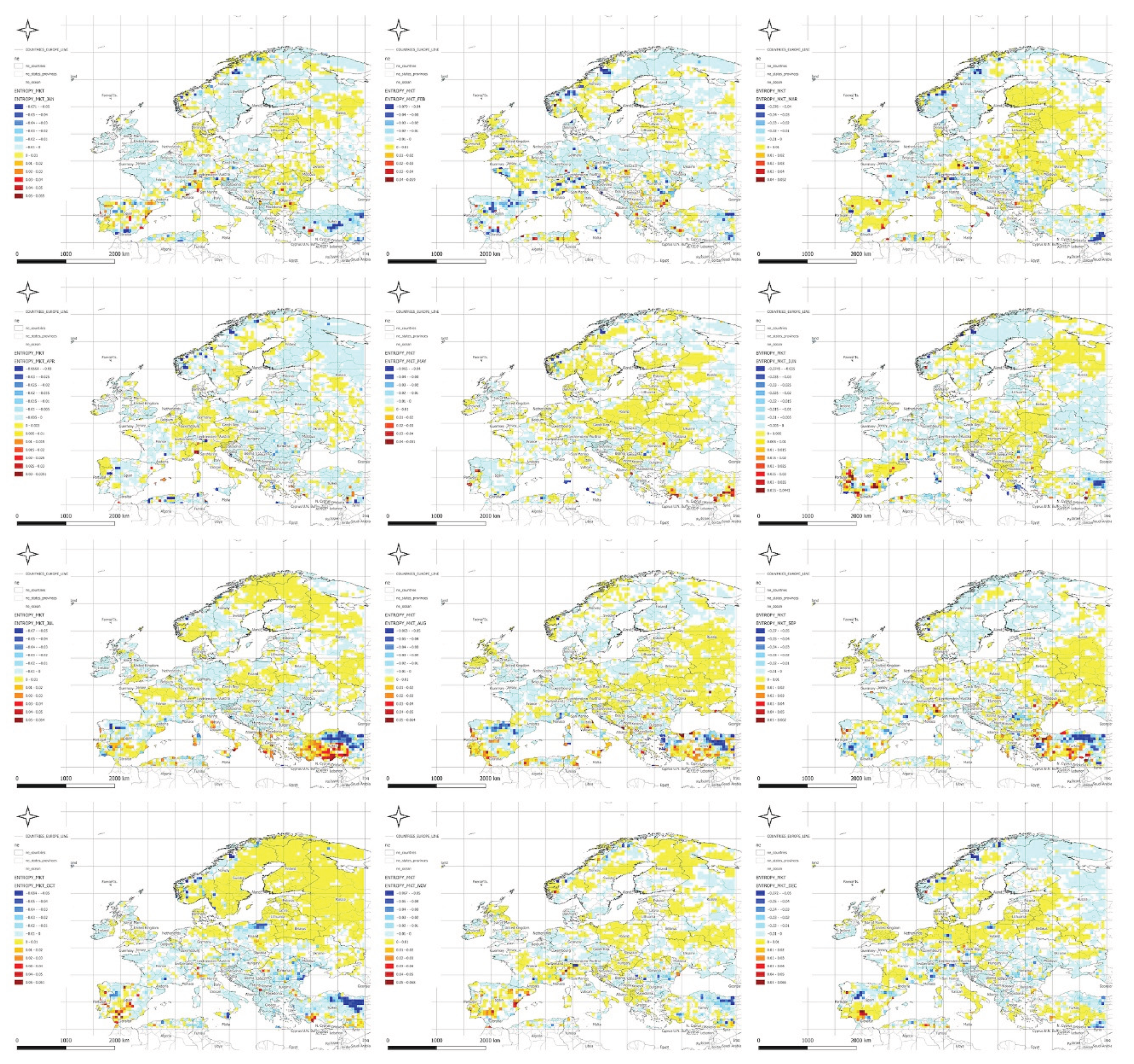

The spatial distribution of meteorological entropy trends, calculated separately for each calendar month, is presented in

Figure 2. Each of the 12 panels corresponds to a specific month. The color scheme illustrates the direction and magnitude of entropy trends—shades of red and orange indicate statistically significant increasing trends, while shades of blue denote decreasing trends. The statistical significance of the results was assessed using the Mann–Kendall test at a 5% significance level.

In January, positive trends (yellows and light oranges) dominate, particularly across Central Europe and Scandinavia, which may indicate increasing variability in winter weather conditions. February displays a greater number of negative trends in Southeastern Europe and the Alpine region, possibly reflecting a stabilization of local winter climates.

In March, distinctly positive trends appear in Germany, Poland, Scandinavia, and northern France, suggesting a rise in weather variability during the early spring period. April presents a more spatially scattered trend pattern, though positive values still prevail across Central and Eastern Europe.

May exhibits particularly strong positive trends in the Black Sea basin, the Balkans, and western Russia. June shows widespread positive trends across most of Europe, indicating a rise in atmospheric instability associated with the onset of summer.

In July and August, positive trends dominate Northern and Central Europe, while the southern parts of the continent show more areas with no statistically significant changes. September reveals decreasing entropy trends in Spain, Portugal, and southern France, while positive trends persist in the northern parts of the continent.

In October, entropy increases are especially prominent in Eastern Europe, including the Baltic states and western Russia. November brings marked positive trends in Central and Eastern Europe, along with localized decreasing trends in the western regions. In December, strong positive trends dominate across Northern Europe, with additional increases observed locally in the Alpine and Balkan regions.

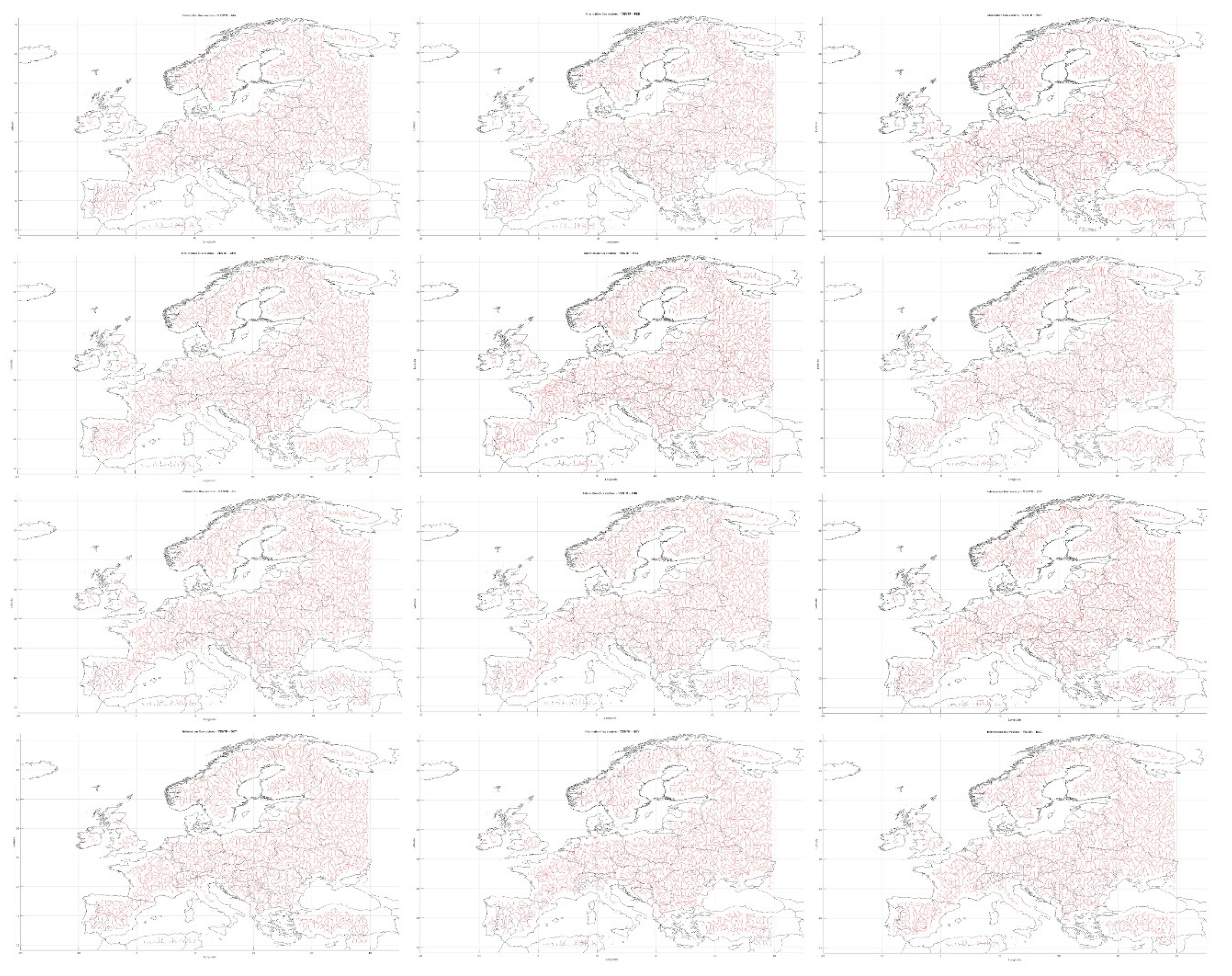

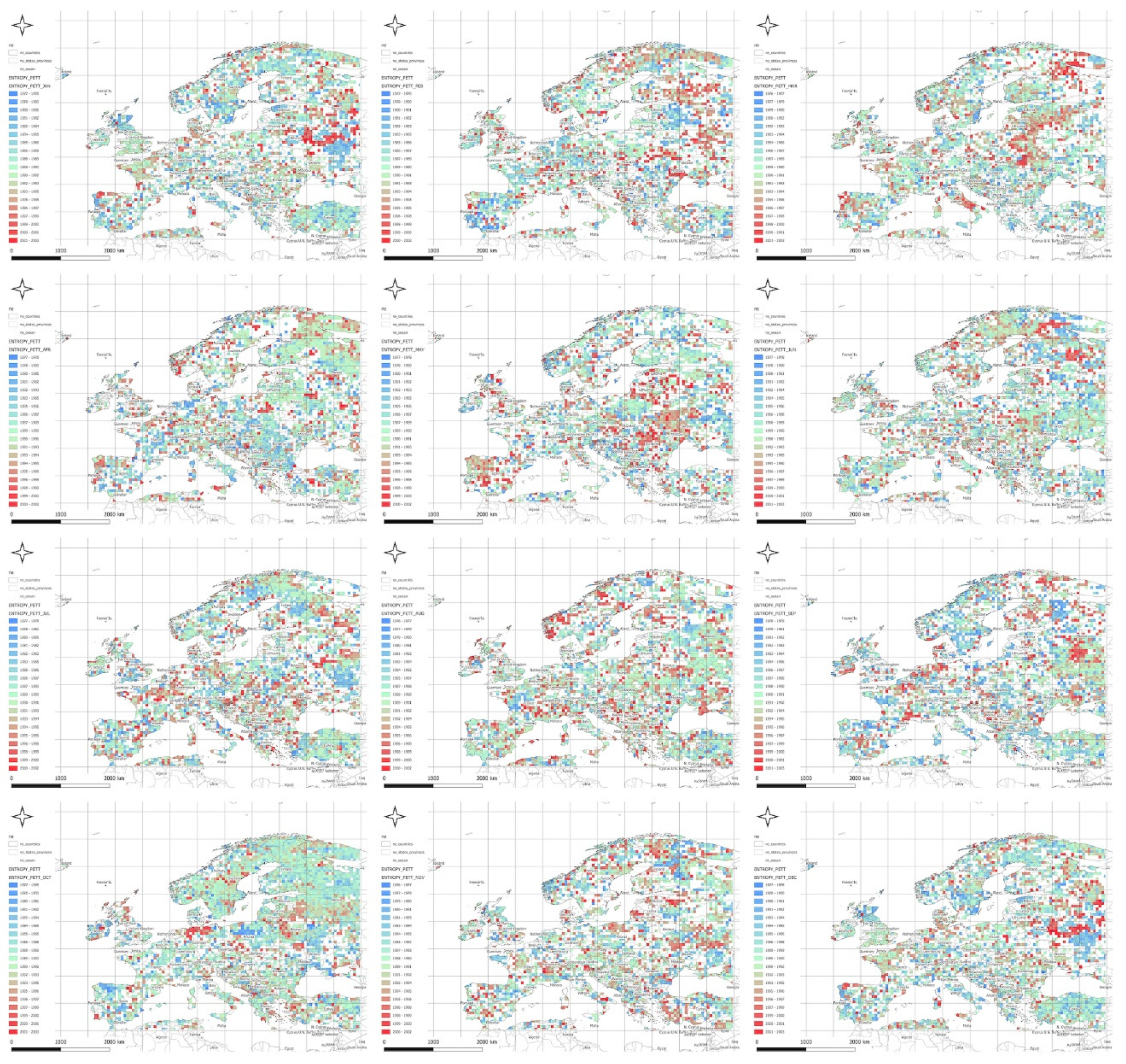

Figure 3 presents the spatial distribution of the year in which a statistically significant change in meteorological entropy trend occurred, as determined using the Pettitt Change Point Test (PCPT) at the 5% significance level. Each of the twelve panels corresponds to a calendar month, from January (top left) to December (bottom right). The colors on the maps indicate the year in which the change point was detected—ranging from 1971 (dark blue) to 2010 (red)—while white areas represent grid cells where no statistically significant trend change was observed.

In January, the majority of change points occur after 1990, particularly across Central and Northern Europe. February displays a more dispersed pattern, with many change points falling between 1980 and 1995, especially in the Balkans and Southwestern Europe. In March, trend changes tend to occur earlier—often in the 1970s—predominantly over the Alpine region, Germany, and France. April exhibits a concentration of change points around 1990, especially across Central and Eastern Europe.

In May and June, red and orange hues dominate, indicating that the entropy trend changes tend to occur near the end of the analysis period (1995–2010). July and August display more spatially and temporally heterogeneous distributions of change points, suggesting that localized processes may be influencing entropy during the summer season.

In September, relatively early change points are observed, particularly in Northern Scandinavia and parts of Western Europe. October and November are characterized by a dense clustering of change points in Central and Northern Europe, primarily during the 1985–2000 period. December shows a prevalence of late-occurring changes, concentrated mostly in Southeastern Europe.

Mountain regions, such as the Alps and Carpathians, frequently exhibit earlier occurrences of change points, which may reflect a heightened sensitivity of entropy to shifting climatic conditions in orographically complex areas. In contrast, the absence of detected change points in regions such as Northern Scandinavia or Southern Spain suggests a relative stability of entropy trends in those areas.

The identified change point patterns also exhibit a seasonal character: during winter months, changes are more likely to occur in the final two decades of the study period, whereas during spring and autumn, the majority of change points cluster in the 1980s and 1990s.

10. Temporal Spearman Correlations

In this study, we analyze the spatial flows of informational entropy, computed from climate data on a grid with a resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. The adopted approach enables the identification of subtle, directional patterns of climate variability that often remain undetected when using conventional statistical methods.

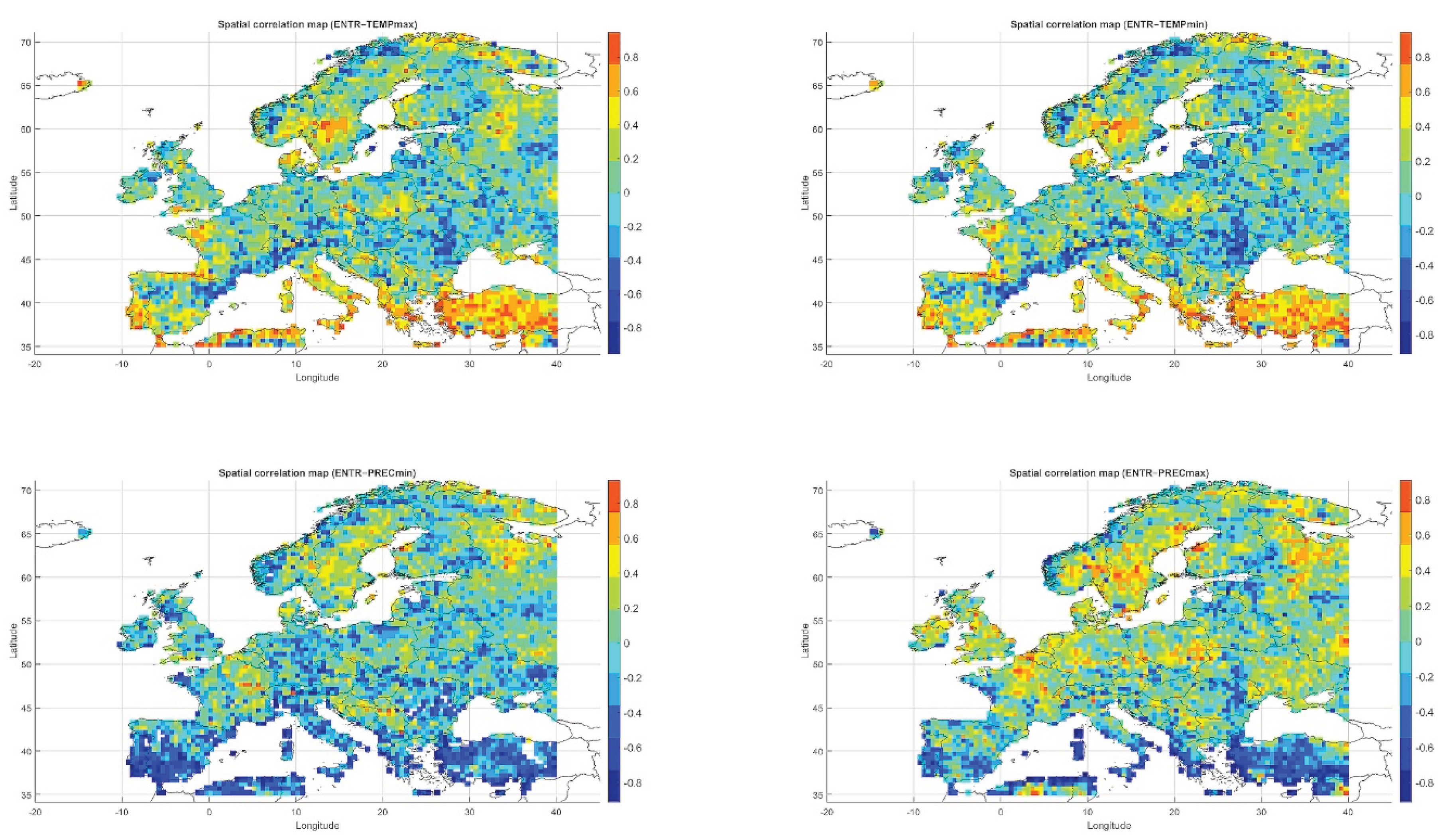

Below, we present correlation maps between meteorological entropy and selected climate parameters. The color scale on the right side of each map indicates the strength and direction of the correlation: warm colors (yellow, orange, red) represent positive correlations, while cool colors (various shades of blue) correspond to negative correlations.

10.1. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy and Monthly Maximum Temperature

The Spearman correlation map between informational entropy and monthly maximum temperature (

Figure 4) reveals clear spatial variability in their relationship. In Southern Europe—particularly over the Iberian and Apennine Peninsulas, Greece, and Turkey—strong positive correlations dominate, locally exceeding 0.6. This suggests that increased atmospheric irregularity is associated with the occurrence of extremely high temperatures, which is typical of the Mediterranean climate regime.

In Central and Northern Europe (Germany, Poland, the Baltic States), correlations are weak or near zero, possibly reflecting the dominance of other climatic drivers. Scandinavia and the North Sea region also show positive correlations, although more limited in extent. Mountain regions (the Alps, Carpathians, and Pyrenees) display strong local contrasts, likely influenced by orographic effects. A patchwork of correlations is observed in Eastern Europe (Ukraine, Russia), indicating the absence of a unified mechanism. In parts of France and Italy, notable negative correlations appear, suggesting that higher entropy may coincide with lower maximum temperatures.

Overall, the spatial pattern indicates that the relationship between entropy and extreme temperatures is particularly pronounced in regions characterized by high seasonality and thermal instability.

10.2. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy and Monthly Minimum Temperature

The correlation pattern with minimum temperature (

Figure 4) differs significantly from that observed for

. In Southeastern Europe (Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, and the Black Sea coast), strong negative correlations dominate, implying that higher entropy may be associated with nighttime cooling and an increased risk of low

values.

In Central Europe, correlations are more variable—often close to zero, occasionally negative. In Scandinavia and northern Russia, weak positive correlations prevail, which may reflect a buffering effect of atmospheric variability on temperature drops. Mountain regions (Alps, Carpathians) exhibit strong local contrasts, likely due to microscale processes and topographic complexity. Neutral relationships dominate in Western Europe (France, Germany), while the Iberian Peninsula displays considerable heterogeneity, with both positive and negative values.

The relationship between entropy and is especially relevant in the context of frost risk and agricultural impacts. In arid and mountainous regions, strong negative correlations suggest the need for localized microclimatic analyses.

10.3. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy and Monthly Maximum Precipitation

The map of entropy correlations with monthly maximum precipitation totals (

Figure 4) reveals a predominance of positive correlations across Central and Northern Europe (Germany, Poland, the Baltic States, Scandinavia). This indicates that higher entropy may be linked to increased risk of high-precipitation months, often associated with cold fronts and cyclonic activity.

In Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece), negative correlations prevail, suggesting that in these regions, increased atmospheric variability does not correspond to greater monthly precipitation maxima—likely due to the influence of summer dry seasonality. Mountain areas (Alps, Pyrenees) display a diverse range of correlation values, reflecting local effects such as orographic lifting and convective storms. Western Europe (France, the British Isles) shows localized positive correlations.

In many temperate regions, correlations exceed +0.4, indicating the potential of entropy as an indicator for extreme precipitation risk.

10.4. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy and Monthly Minimum Precipitation

Correlations between entropy and monthly minimum precipitation totals (

Figure 4) reveal a distinct north–south contrast. In Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey), strong negative correlations dominate, indicating a link between high entropy and increased drought risk. In Western and Central Europe, correlations are generally weak or neutral.

In Scandinavia and the British Isles, weak positive correlations prevail, suggesting that atmospheric variability does not directly translate into dry months in these regions. Areas around the Black Sea exhibit negative correlations, likely due to strong precipitation seasonality and local circulation patterns.

In mountainous regions (Alps, Carpathians, Pyrenees), as well as in Southern Spain and Sicily, strong local negative correlations appear, indicating that entropy may be a reliable indicator of monthly drought risk. Urban areas (e.g., London, Paris, Berlin) do not exhibit significant anomalies.

10.5. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy Gradient and Monthly Maximum Temperature

The Spearman correlation map between the entropy gradient and monthly maximum temperature (

Figure 5) reveals strong regional contrasts. In Southeastern Europe (Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans), dominant strong positive correlations (>0.6) indicate a link between local variability changes and susceptibility to heatwaves. In these regions, the entropy gradient may reflect growing thermal instability.

In Central and Western Europe, correlations are predominantly negative or near zero, suggesting the stabilizing effect of a temperate climate. The Alps and southern Germany exhibit strong negative correlations, potentially indicating that increases in entropy gradients are associated with reductions in temperature extremes.

In Scandinavia (Norway and Sweden), positive correlations are observed, possibly reflecting the high sensitivity of the boreal climate. The Benelux countries, France, and the British Isles show values close to zero, while localized positive correlations appear in Italy, Ukraine, and Romania—regions that may serve as transitional zones between maritime and continental climatic influences.

Topography emerges as a significant factor: in mountainous areas, entropy gradients often display an inverse relationship with temperature compared to lowland regions.

10.6. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy Gradient and Monthly Minimum Temperature

The correlation map between the entropy gradient and minimum temperature (

Figure 5) reveals strongly negative values in Southeastern Europe—particularly Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans—reaching below –0.6. This suggests that increasing variability may be associated with intensified cold nights, likely due to inversions or radiative cooling effects.

In Western Europe, correlations are near zero, while in the Alps and Carpathians, localized positive values appear—likely influenced by terrain features and local atmospheric dynamics. Scandinavia exhibits moderate positive correlations, which may indicate the dampening of cold extremes under increased instability.

In the Adriatic region, the entropy gradient shows strong negative correlations with TminT_{\text{min}}Tmin, possibly driven by advective cooling. In Central Europe (Poland, Germany, Czechia), a mosaic pattern emerges, likely due to seasonal shifts in the influence of precipitation and snow cover.

The entropy gradient may serve as an indicator of frost risk, though the relationship is not uniform and requires seasonal analysis—particularly in winter months.

10.7. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy Gradient and Monthly Minimum Precipitation

The analysis of the entropy gradient’s correlation with minimum monthly precipitation (

Figure 5) reveals a predominance of negative relationships in Southern Europe—especially in Spain, southern France, Greece, Italy, and Turkey. Values below –0.4 suggest a connection between increasing spatial variability and the risk of drought conditions.

In Central Europe (Poland, Czechia, Germany), correlations are weak or neutral. In Scandinavia and the North Sea region, positive correlations are more common, suggesting greater precipitation stability despite increased entropy gradients.

Localized positive correlations are observed in the Alps and Carpathians, while positive values dominate in Eastern Europe (Ukraine, Russia), indicating a more continental-type response of precipitation to spatial variability.

Overall, the entropy gradient appears useful in detecting regions vulnerable to drought, particularly in the Mediterranean basin.

10.8. Spatial Relationship Between Entropy Gradient and Monthly Maximum Precipitation

Correlations between the entropy gradient and monthly maximum precipitation (

Figure 5) are generally positive across temperate regions—especially in Germany, Poland, the Baltic States, and Western Russia—ranging from 0.2 to 0.6. This suggests that spatial instability is associated with the intensification of extreme precipitation episodes.

Scandinavia (Norway and Sweden) also shows positive correlations. In Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece), correlations are mostly negative or neutral, likely due to strong seasonality and limited spatial variability during dry periods.

Urban areas (e.g., London, Paris, Berlin) and mountain regions (e.g., the Alps) exhibit moderate positive relationships. The entropy gradient thus emerges as a sensitive indicator of spatial rainfall dispersion, potentially valuable for assessing flash flood risk.

11. Seasonal–Spatial Spearman Correlations

11.1. Analytical Approach

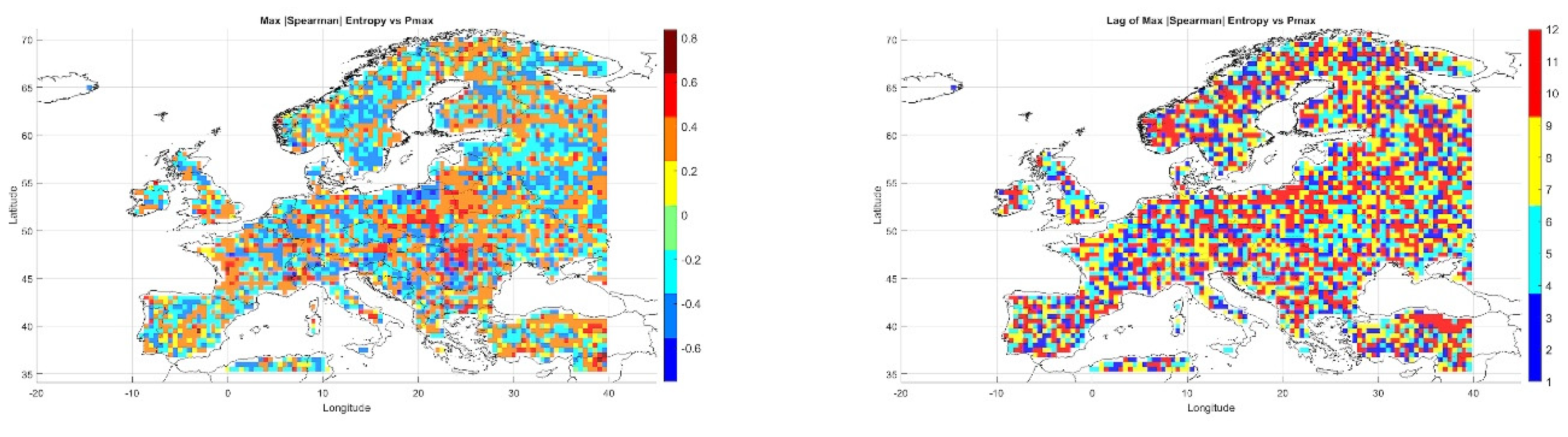

A spatial-seasonal analysis was performed on the maximum absolute values of Spearman rank correlations between meteorological entropy (incorporating monthly temperature and precipitation) and extreme climate parameters. Time lags from 1 to 12 months were considered to evaluate the predictive potential of entropy in anticipating climate changes.

11.2. Entropy and Monthly Minimum Temperature

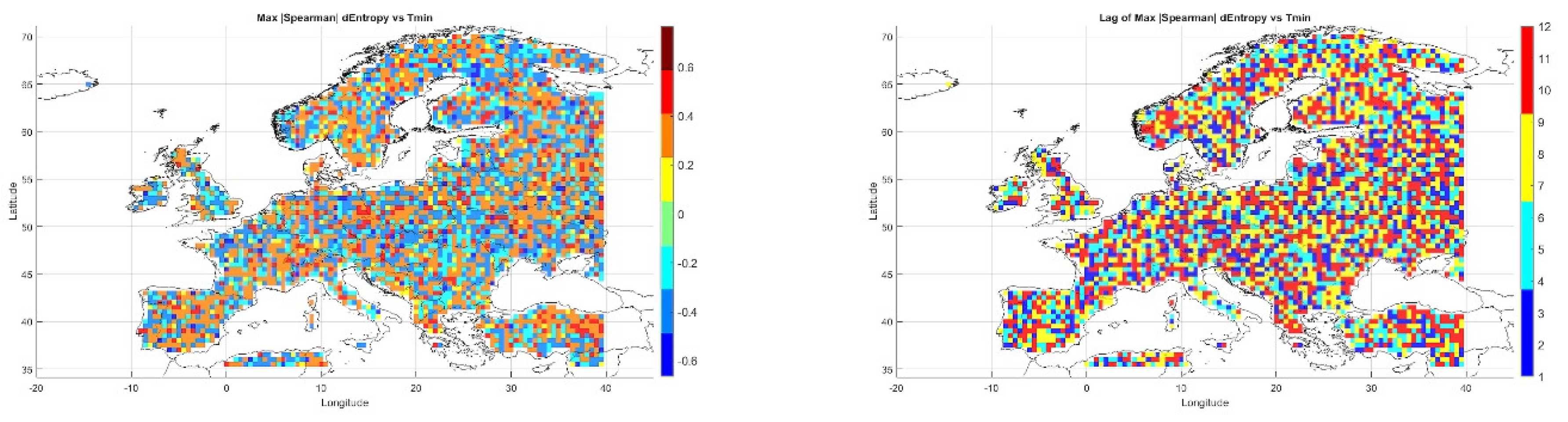

Figure 6 presents maps of maximum absolute correlations (left panel) and the corresponding time lags (right panel). In Central-Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, positive correlations dominate (ranging from 0.4 to 0.6), suggesting that increases in entropy precede declines in

. In contrast, negative correlations are observed in Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece), indicating the inverse relationship.

The most frequent lag values fall between 6 and 10 months, pointing to the seasonal nature of the observed interactions. In higher latitudes (above 60°N), correlations remain positive, with shorter lags (3–5 months), reflecting the more immediate response of boreal climates. The spatial consistency of 6–9 month lags across Central-Eastern Europe may indicate the presence of a semiannual climatic memory mechanism.

11.3. Entropy and Monthly Maximum Temperature

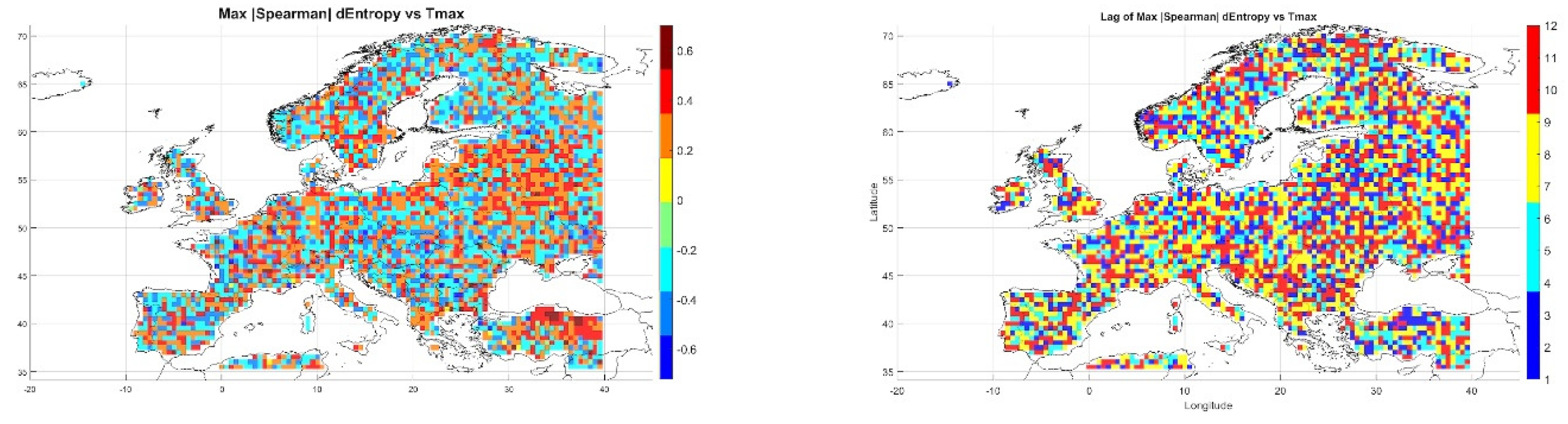

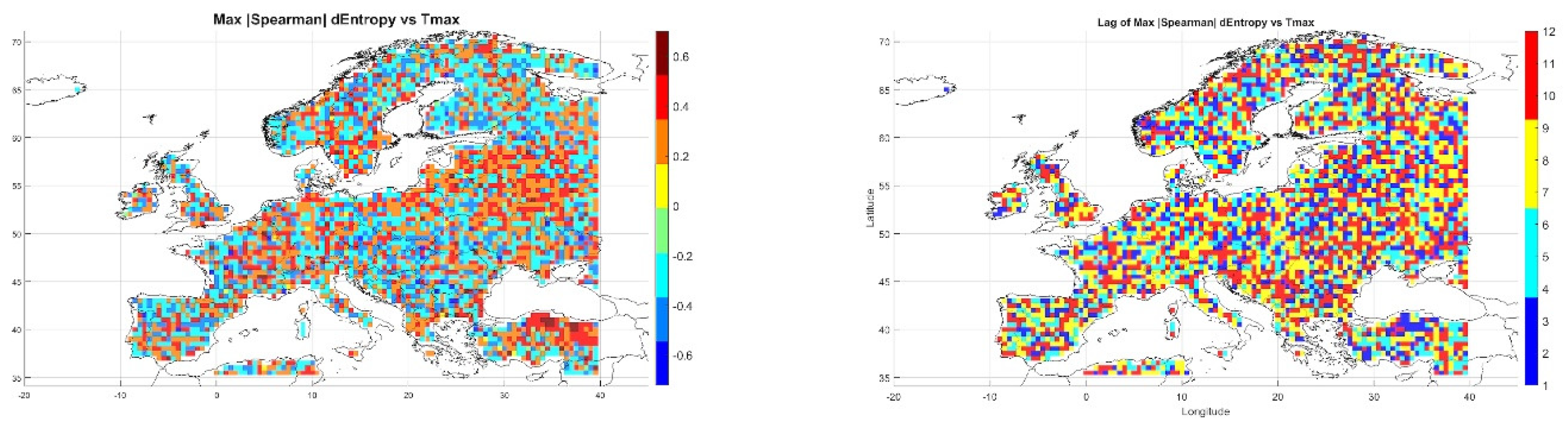

Figure 7 presents an analogous analysis for

. Strong positive correlations (>0.4) are observed in Central-Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, suggesting that entropy is a reliable indicator for forecasting episodes of elevated temperatures. In Southern Europe, negative correlations dominate, possibly reflecting local damping mechanisms.

The strongest associations occur with time lags of 6–9 months. Western Europe shows greater spatial variability and generally weaker correlations, likely due to oceanic influence and seasonal instability. The similarity in lags between and points to the seasonal consistency of the system’s response. However, regional differences in correlation strength and direction highlight the need for localized modeling approaches for maximum temperatures.

11.4. Entropy and Monthly Minimum Precipitation

Figure 8 illustrates the spatial distribution of correlations and time lags between entropy and

. Positive correlations (>0.4) prevail across Central and Northeastern Europe, indicating that entropy anomalies precede periods of reduced rainfall. In Southern Europe (Spain, Greece, Turkey), negative correlations (down to –0.6) dominate, suggesting distinct climatic dynamics in these regions.

The strongest correlations occur at lags of 6–10 months, while in Southern Europe the lags are shorter (<4 months). Eastern Europe exhibits a high degree of lag regularity, potentially indicating a stable climatic rhythm. In countries such as Poland, Ukraine, and Finland, entropy may serve as a strong predictor of drought conditions. Variability in mountainous areas may be influenced by orographic effects.

11.5. Entropy and Monthly Maximum Precipitation

Figure 9 presents the relationship between entropy and monthly precipitation maxima. Positive correlations (>0.4) dominate across Central and Eastern Europe, with local maxima up to 0.8 observed in southern Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic—where increased entropy precedes intense precipitation events.

The strongest correlations are found at 6–9 month lags, with several regions also showing peaks at 12 months, suggesting the existence of annual precipitation cycles. In the Mediterranean basin, correlations are weaker or even negative, likely due to seasonal dryness and irregular atmospheric dynamics. High correlations in mountainous regions (Alps, Carpathians) suggest that topography significantly modulates the precipitation response to entropy variability.

11.6. Summary

Meteorological entropy shows strong delayed

associations with extreme values of temperature and precipitation. The highest

positive correlations are observed in Central Europe, Scandinavia, and parts of

Eastern Europe. The most common time lags are in the 6–9 month range,

indicating a seasonal translation of entropy variability into climate

parameters. Topography and local factors (e.g., oceanic climate, seasonal

circulation) significantly influence the strength and direction of these

relationships. Entropy may function as an early proxy for predicting , offering potential applications in climate

modeling and early warning systems for extreme weather events.

11.7. Temporal Derivative of Entropy and Minimum Temperature

Figure 10

displays the maximum absolute Spearman correlations between the temporal

derivative of entropy and monthly minimum temperature, along with the

corresponding time lag. The left panel shows the correlation strength, and the

right panel shows the lag (in months) at which the correlation peaks.

High positive correlations (up to 0.6) are observed

in Central and Eastern Europe (Poland, Germany, Ukraine, western Russia),

suggesting a strong seasonal link between entropy change and Scandinavia also exhibits significant positive

correlations, confirming the responsiveness of colder climates to systemic

variability.

In mountainous regions (Alps, Carpathians),

correlations are more variable, likely due to orographic influences. In

Southern Europe (Greece, southern Italy), negative correlations are present,

probably associated with distinct thermal regimes. Most common lags range from

5 to 9 months, indicating a seasonal nature in response to entropy changes. In some areas, a lag

of 12 months is observed, suggesting annual cycles in climatic response.

Shorter lags (2–4 months) in Southern Europe may indicate quicker responses to

atmospheric anomalies.

Figure 10.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation

at the 5% significance level.

Figure 10.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation

at the 5% significance level.

11.8. Temporal Derivative of Entropy and Maximum Temperature

Figure 11

shows the correlation between the temporal derivative of entropy (dEntropy) and

monthly maximum temperature (TmaxT_{\text{max}}Tmax), with time lags

included.

Positive correlations (0.2–0.6) dominate in Central

and Eastern Europe (Poland, Czechia, Germany, western Russia), indicating a

relationship between rapid changes in atmospheric variability and extreme

temperatures. In Greece, Turkey, and the Balkans, correlations reach up to

0.65, likely due to heatwaves and Mediterranean convective circulation.

In Western Europe (France, the UK), correlations

are weaker and more scattered—likely influenced by oceanic climate. Mountainous

and coastal areas show greater correlation variability, reflecting local

topographic and hydrological conditions.

Most common lags range from 6 to 9 months,

particularly in Central Europe. Longer lags (10–12 months) in the Baltic States

and Finland may indicate a cumulative thermal response. Shorter lags occur

mainly in coastal regions.

Figure 11.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

Figure 11.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

11.9. Temporal Derivative of Entropy and Monthly Minimum Precipitation

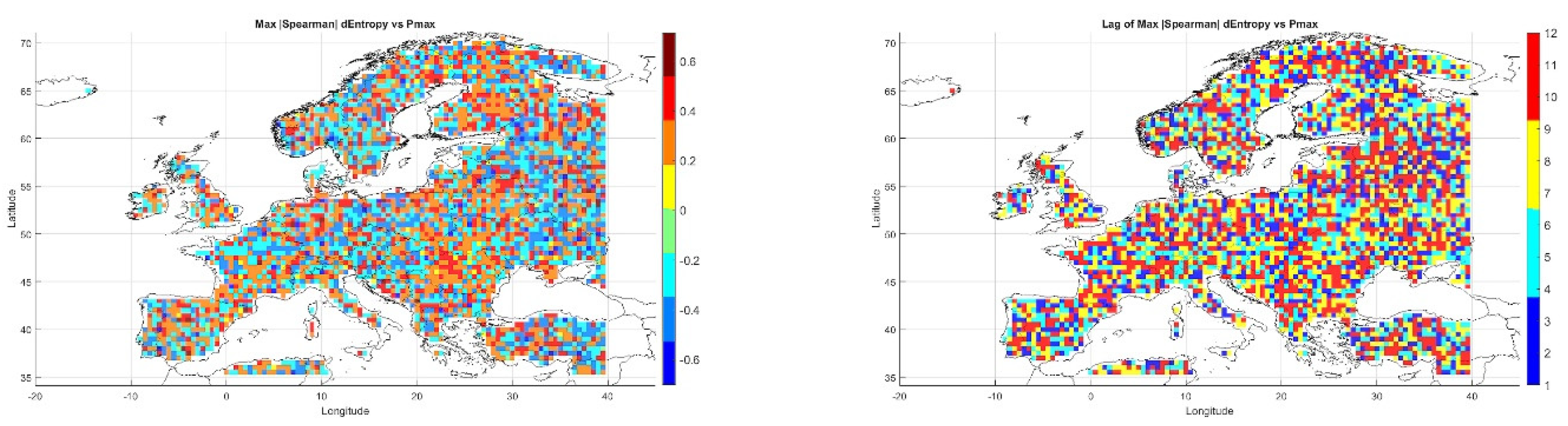

Figure 12

presents the spatial distribution of maximum correlations between dEntropy and

monthly minimum precipitation sums.

Positive correlations (0.4–0.6) dominate in Central

and Eastern Europe (Poland, Germany, Ukraine, Belarus), suggesting that rising

climate system variability may precede periods of rainfall deficit. Western

Europe and Scandinavia show weaker correlations, possibly due to higher weather

variability and oceanic influence.

Southern Europe displays more spatially

heterogeneous correlations. Most common lag values range from 6 to 10 months,

though in parts of southern and western Europe, lags are shorter (2–5 months).

This suggests regional differences in climate sensitivity to entropy changes.

Lag analysis indicates that dEntropy could serve as

a useful early-warning indicator for seasonal drought conditions.

Figure 12.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

Figure 12.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

11.10. Temporal Derivative of Entropy and Monthly Maximum Precipitation

Figure 13

illustrates the correlations between the temporal derivative of entropy and

maximum monthly precipitation totals.

The strongest positive correlations (up to 0.6)

occur in Central-Eastern Europe (Poland, Czechia, Ukraine, Romania), indicating

that dEntropy may be an effective predictor of intense rainfall episodes.

Western Europe and Scandinavia show significantly weaker correlations.

Southern Europe (Spain, Greece, Italy) exhibits

mixed relationships—both positive and negative—highlighting greater regional

complexity. High correlations in the Carpathians, Alps, and Balkans likely

reflect local orographic effects promoting convection.

Most frequent lag values fall between 6 and 10

months. In Southern Europe, shorter lags (2–5 months) dominate, possibly due to

faster atmospheric responses. The high spatial coherence of lag patterns

suggests the presence of shared circulation mechanisms.

Figure 13.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

Figure 13.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

12. Entropy Relationships with Climate Indices

Informational entropy, calculated from

meteorological variables (temperature and precipitation), is increasingly

applied as an indicator for analyzing the variability and non-stationarity of

climate systems—both at regional and global scales. Particularly noteworthy is

its potential to reflect the influence of processes such as global warming

(e.g., GISTEMP index) and oceanic oscillations (e.g., ENSO – El Niño Southern

Oscillation).

Due to its sensitivity to changes in atmospheric

dynamical structure, entropy may complement classical circulation indices by

providing additional insight into the underlying mechanisms of weather systems.

The presence of strong positive correlations across Eastern and Northern Europe

suggests that entropy may serve as an indirect proxy for sea surface

temperature (SST) anomalies, while negative correlations in regions such as the

Mediterranean may indicate local hydrological anomalies or differing modes of

climate response.

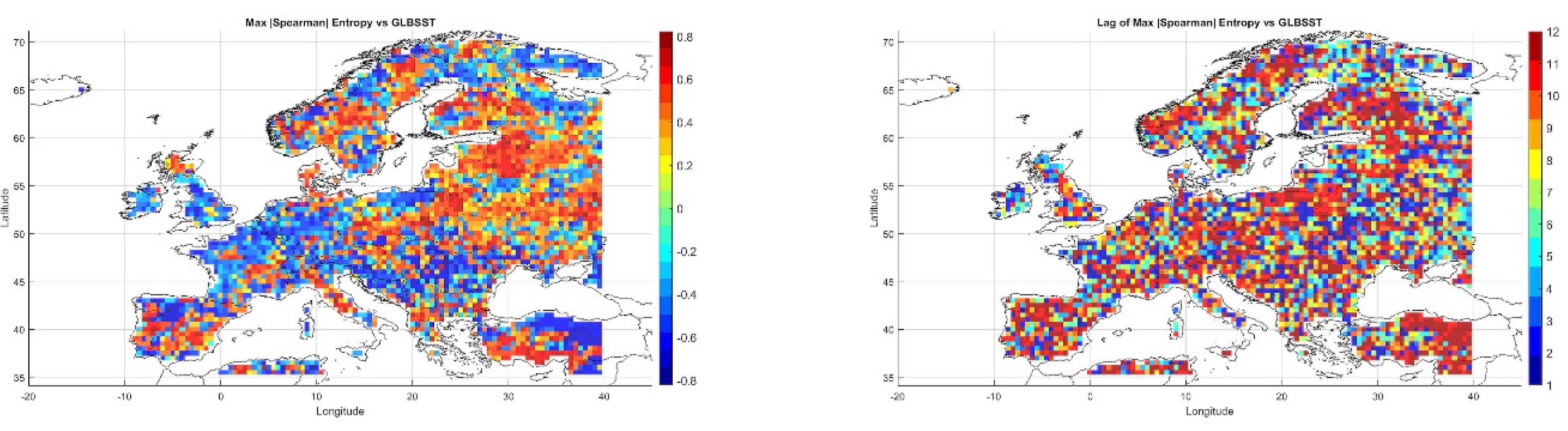

12.1. Entropy and GLBSST (GISTEMP)

Figure 14

presents the maximum absolute values of Spearman correlations between

informational entropy derived from meteorological fields and the global sea

surface temperature index GLBSST (GISTEMP), along with the corresponding time

lags.

The left panel shows that positive correlations

dominate across Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe, reaching values above

0.6 in some areas. This suggests a strong influence of global SST fluctuations

on continental climate variability.

In Southern Europe—particularly in Turkey and

northern Africa—correlations are predominantly negative, which may reflect a

distinct mechanism for GLBSST signal transmission within the Mediterranean

climate regime.

The right panel displays the spatial distribution

of time lags, which most frequently range from 9 to 12 months. This is

consistent with established mechanisms of energy transfer between ocean and

atmosphere. The homogeneity of lag times across Central and Eastern Europe

contrasts with greater variability in the south, highlighting the potential

role of local topographic conditions in modulating atmospheric response.

Figure 14.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

Figure 14.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

12.2. Entropy and ENSO (NINO3.4)

Figure 15

illustrates the relationships between meteorological entropy and the ENSO index

NINO3.4, including the time lags at which the correlations are strongest. High

positive correlations (exceeding 0.6) are observed across Scandinavia, Russia,

and Central Europe, confirming the influence of ENSO on climate variability in

these regions despite their considerable distance from the tropics.

In Southern Europe—including the Mediterranean

basin, Turkey, and the Iberian Peninsula—negative correlations dominate,

suggesting an inverse ENSO effect in the warm, arid climates of the southern

continent.

The distribution of time lags shows that the

strongest correlations typically occur with lags of 8–12 months in Eastern and

Northern Europe, indicating a long-term, indirect ENSO influence via

atmospheric circulation mechanisms. In contrast, Western and Southern Europe

exhibit shorter lags (4–6 months), suggesting a faster atmospheric response.

Figure 15.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

Figure 15.

Maximum absolute Spearman correlation at the 5% significance level.

Figure 16.

Shannon entropy fluxes for temperature and precipitation across Europe.

Figure 16.

Shannon entropy fluxes for temperature and precipitation across Europe.

Figure 17.

Spatial–temporal components of informational entropy in the climate-scale analysis over Europe.

Figure 17.

Spatial–temporal components of informational entropy in the climate-scale analysis over Europe.

12.3. Summary

Meteorological entropy shows statistically

significant relationships with global climate indices, both in terms of

strength and spatiotemporal structure. Both GISTEMP and ENSO influence weather

variability in Europe with notable time lags, making entropy a potentially

valuable prognostic indicator—especially in early warning systems for climate

anomalies. The observed regional differences in correlation magnitude and lag

length underscore the need for local calibration and integration of entropy

into seasonal forecasting models alongside established climate indices.

13. Entropy Fluxes – Localization of Entropy Sources and Sinks

Informational entropy fluxes and their associated

sources and sinks are closely linked to prevailing atmospheric circulation

types over Europe.

Western circulation patterns (types W, SW) favor

west-to-east entropy transport, reflecting the activity of Atlantic

low-pressure systems. Anticyclonic blocking events (e.g., NE patterns,

continental regimes) are associated with the formation of “entropy holes”—areas

of reduced weather variability, particularly over Central and Eastern Europe.

Southern circulation (S, SE) is linked to local entropy sources over the

Mediterranean and Balkans, driven by convection and the influx of moist,

unstable air masses.

Elevated spatial entropy often accompanies the

passage of atmospheric fronts, especially under strong thermal gradients.

13.1. Sources and Sinks of Entropy

Regions exhibiting locally elevated entropy can be

interpreted as generators of climatic

variability, often located in dynamic transitional zones such

as:

The Iberian Peninsula,

The Balkans,

Scandinavia.

In contrast, entropy sinks—areas where entropy is lower than the surrounding

environment—tend to exhibit greater atmospheric stability and are more

susceptible to external disturbances. Analyzing these structures facilitates

the identification of initiation points and propagation pathways of extreme

weather events.

13.2. Entropy Streamlines

Figure 16

presents monthly vector fields of informational entropy fluxes, calculated from

the spatial gradient of normalized entropy fields. The streamlines illustrate

the direction and relative intensity of climate information flow on a

mesoscale.

Seasonal flow patterns include:

Winter

(January–February): Dominated by organized flows from the north

and northeast, especially over Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, associated with

continental air masses and stable pressure systems.

Spring

(March–April): Increasing local variability and more

diversified flow structures reflect the transitional nature of the season.

Summer

(July–August): Characterized by short, meandering entropy

streams, indicating enhanced local turbulence. In Southern Europe, more

organized westward flows appear, linked to land–ocean thermal gradients.

Autumn

(September–November): Flows begin to reorganize toward

wintertime patterns. May shows intensification over the Balkans, while

September highlights increased activity over Western Europe.

13.3. Sources and Convergences – Spatial Organization

Strong entropy sources and sinks—identified as

divergences and convergences of entropy streamlines—frequently appear

seasonally over Central Europe, suggesting its role as a nodal region for the transmission of climate signals.

These structures are essential for understanding the regional spread of weather

disturbances.

13.4. Links to Teleconnections and Orography

Spatial patterns of entropy fluxes demonstrate

correlations with global teleconnection indices:

Both NAO and ENSO appear to modulate the direction and intensity of

atmospheric information transport.

Months such as March

and November exhibit highly directional flows, indicating the

dominance of specific circulation mechanisms.

In other months, more chaotic flows prevail—typical

of local diffusion and convective dynamics.

Topography plays

a crucial role in shaping these structures. The Alps, Carpathians, and Scandinavian Mountains

often act as barriers to the propagation of

climate information, influencing the configuration and behavior

of entropy fluxes across the continent.

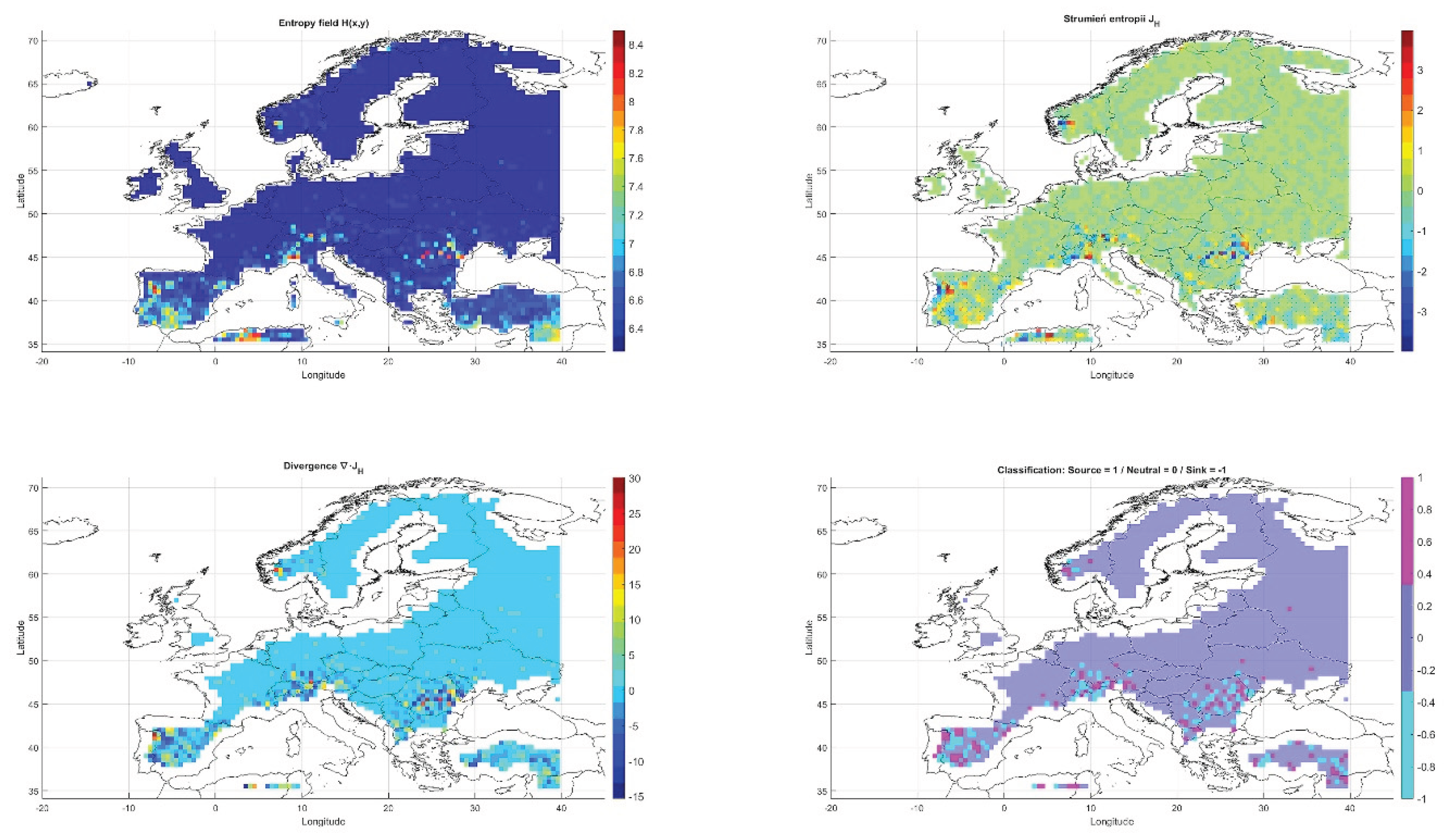

The maps in Figure

17 illustrate the key components of spatial-temporal analysis of

informational entropy at the climatic scale across Europe. The top-left panel

presents the entropy field , representing the local complexity of weather

variability as measured by Shannon entropy, calculated from the joint

distributions of temperature and precipitation. The highest entropy

values—indicating the greatest unpredictability of the weather regime—are

observed over the Mediterranean Basin and southern Balkans, suggesting

significant seasonal instability in these regions. In contrast, Northern and

Central Europe display lower , values, pointing to higher predictability of

climatic patterns, likely associated with the dominance of stable baric

systems.

The top-right panel shows the entropy flux (a vector field of information transfer), computed

as the negative gradient of the field. Areas with strong values, particularly over the Pyrenees, Alps, and

Carpathians, indicate substantial climatic information transfer between

adjacent grid cells—likely resulting from orographic influences and localized

atmospheric circulation.

The bottom-left panel depicts the divergence , identifying source regions (positive values) and

sink regions (negative values) of entropy. Notably high positive divergence

appears over southern France, Switzerland, and parts of Italy, suggesting these

as localized centers of weather variability generation. Conversely, negative

divergence values over Hungary and Romania designate these areas as entropy

sinks—absorbing external climatic signals.

To delineate neutral, source, and sink regions,

threshold values were defined based on the 5th and 95th percentiles of : the lower threshold (sink) at –3.464, and the

upper threshold (source) at 3.646. The classification shown in the bottom-right

panel assigns each grid cell to one of three categories: source (1), neutral

(0), or sink (–1). A clear dominance of the neutral state is observed,

consistent with expectations for most regions experiencing relatively

homogeneous and stable weather conditions. The notable concentration of sources

in mountainous regions emphasizes the role of topography in generating local

entropy.

The spatial analysis of the informational entropy

field reveals structured variability across Europe at the continental scale.

High entropy values cluster over southern and eastern Europe, highlighting

areas of elevated disorder and potential atmospheric instability. The entropy

field displays a clear directional structure, indicating paths of fluctuation

propagation. Entropy fluxes reveal the dominant spatial pathways of weather

information transport, strongly aligned with prevailing circulation trajectories.

A predominant west-to-east and south-to-central continental flux is observed,

reflecting the combined influence of oceanic air masses and convective activity

in southern regions. Local clustering of streamlines points to so-called

“information nodes”—regions with high potential for information exchange.

The divergence field captures zones of information

accumulation and dissipation, offering crucial insight into identifying

climatic instability sources and sinks. Areas with positive divergence are

interpreted as sources—regions initiating climate variability—while negative

divergence denotes zones that suppress instability (entropy sinks). A clear

seasonal signature of sources and sinks is also evident, which may be of

prognostic significance. Source regions often precede the emergence of

extremes, whereas sink zones may act as buffers against atmospheric

disturbances. Spatial classification also facilitates the identification of

transitional zones where local dynamics can undergo rapid shifts.

The persistent occurrence of entropy sources in

southeastern Europe may indicate a heightened climatic sensitivity to external

drivers such as ENSO. The spatial coherence of entropy fluxes and divergence

fields supports the validity of the applied mathematical formalism. This

methodological framework enables not only the visualization of the static field

of weather complexity but also the quantitative capture of the directions and

centers of atmospheric information transmission.

14. Coincidence of Extreme Weather Events with Selected Features of Informational Entropy Transport

Extreme weather phenomena—such as heatwaves,

droughts, and convective storms—demonstrate significant relationships with the

spatial and temporal characteristics of informational entropy transport.

Several key features play a critical role in this dynamic:

Entropy sinks – regions of negative

divergence in the entropy flux field ), where information streamlines converge. These

areas are frequently associated with persistent anticyclonic blocks,

atmospheric stagnation, and the occurrence of droughts or heatwaves. In such

zones, the climate system exhibits a reduced capacity for further dynamical

evolution.

Entropy sources – areas of positive

divergence (), where information fluxes diverge radially

outward. These are often dynamic convective zones conducive to the generation

of intense thunderstorms, convective precipitation, and hailstorms. Notable

source regions include the Balkans, the Alps, the Caucasus, and the eastern

Mediterranean.

Entropy fronts – regions marked by strong

spatial gradients ) and discontinuities in the entropy field. These

structures typically emerge along frontal zones, at the boundaries between air

masses, and over mountainous terrain. They frequently act as initiators of

severe weather events, such as downpours and convective storms.

Seasonal Analysis Findings:

In summer, localized entropy sources (e.g., over

the Balkans or Mediterranean coasts) often precede the onset of storms and

intense rainfall events.

In winter, entropy sinks across Central Europe and

Scandinavia correlate with cold spells and dry periods.

In mountainous regions (such as the Alps or

Carpathians), the presence of so-called “entropy holes” may favor the

development of closed convective storm systems.

Areas characterized by high entropy gradients

(e.g., Scandinavia, Russia) often temporally precede episodes of winter weather

extremes.

14.1. Influence of Atmospheric Circulation Patterns and Baric Systems

Western and southern circulation regimes (W, SW, S)

tend to favor the emergence of entropy sources and intensify information

fluxes. In contrast, continental high-pressure systems (NE types, anticyclones)

contribute to the closure of entropy streamlines, leading to the formation of

sinks and an elevated risk of weather stagnation.

Sudden increases in temporal entropy values may indicate seasonal transitions—such as the

shift to a wet summer or dry autumn. These inflection points often precede the

occurrence of extreme events and are consistent with trend detection

methodologies (Mann–Kendall and Pettitt tests).

14.2. Relationships with Global Indices

The occurrence of entropy sources, sinks, and

fronts is linked to broader systemic signals, including:

ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) –

particularly during El Niño phases, an increase in entropy source activity is

observed over southern Europe, accompanied by intensified extreme

precipitation.

GISTEMP (Global Sea Surface Temperature Index)

– correlates with entropy anomalies, especially in the Mediterranean and

Eastern European regions.

14.3. Prognostic Significance

This analysis confirms that the spatial structure

of informational entropy can serve as an early indicator of forthcoming weather

extremes. Entropy values and their derivatives ) tend to lead the temporal peaks of extreme

temperatures () and precipitation ().

Locations exhibiting strong gradients, convergence

zones, and divergence structures in entropy fluxes form a predictive framework

that can be applied in:

The characteristics of entropy transport—such as

sinks, sources, discontinuities, and temporal spikes—are closely tied to the

manifestation of extreme weather events across Europe. Entropy streamlines

reflect the dynamical organization of atmospheric systems and may serve as

functional prognostic indicators. The integration of informational entropy into

climatology opens new avenues for diagnosing weather instability and for

adaptive climate risk management strategies.

15. Comparative Analysis of Correlations

15.1. Between and with Climatic Variables

Table 3

presents a comparative overview of the spatially distributed, maximum temporal

Spearman correlations between measures of entropy () and its spatial gradient with four key meteorological variables: maximum

temperature, minimum temperature, maximum precipitation, and minimum

precipitation. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for distribution conformity

unambiguously indicates that the correlation distributions deviate

significantly from normality (p < 10⁻¹¹).

This suggests that the information transfer between entropy and climatic

extremes is inherently nonlinear and exhibits strong spatial heterogeneity.

A comparison of the distributions of and its gradient reveals statistically significant

discrepancies, confirming that the flow of information between the two is

complex and non-uniform across space. The analysis of the number of significant

correlations (|ρ| > 0.40) shows that ENTR exhibits more

positive associations with and (exceeding 930 grid points) than with

precipitation metrics. This implies that extreme temperatures are more strongly

related to general atmospheric instability levels. In contrast, for

precipitation—especially —negative correlations dominate, indicating that

low entropy (representing more ordered conditions) is often linked to drought

scenarios.

The entropy gradient (), reflecting the spatial dynamics of variability,

shows fewer positive correlations across all variables, though the number of

negative correlations for (695) and (513) remains high. This supports the

interpretation that rapid shifts in atmospheric instability are particularly

associated with extreme precipitation events, highlighting the prognostic

utility of in this context.

The consistency in the signs of correlations

between and is relatively low—approximately 45% for all

variables—which suggests that the two metrics capture distinct mechanisms

underlying extreme events. The mean values of positive correlations for are highest for temperature variables (around

0.33) and lowest for (0.240), implying that elevated entropy values

tend to promote thermal extremes more than hydrological ones. Conversely, the

most pronounced negative correlations for are also linked to (–0.298), reinforcing the hypothesis that lower

entropy favors highly ordered, dry atmospheric states.

The entropy gradient generally shows stronger

negative correlations than positive ones, with mean values for and surpassing –0.3. This emphasizes the sensitivity

of precipitation variables to short-term dynamic fluctuations in atmospheric

structure. Differences in standard deviations across variables further indicate

that temperature correlations are more dispersed, whereas those for are more concentrated around strong negative

values.

From the perspective of information transfer, appears to better reflect long-term atmospheric