3.1. XPS Analysis

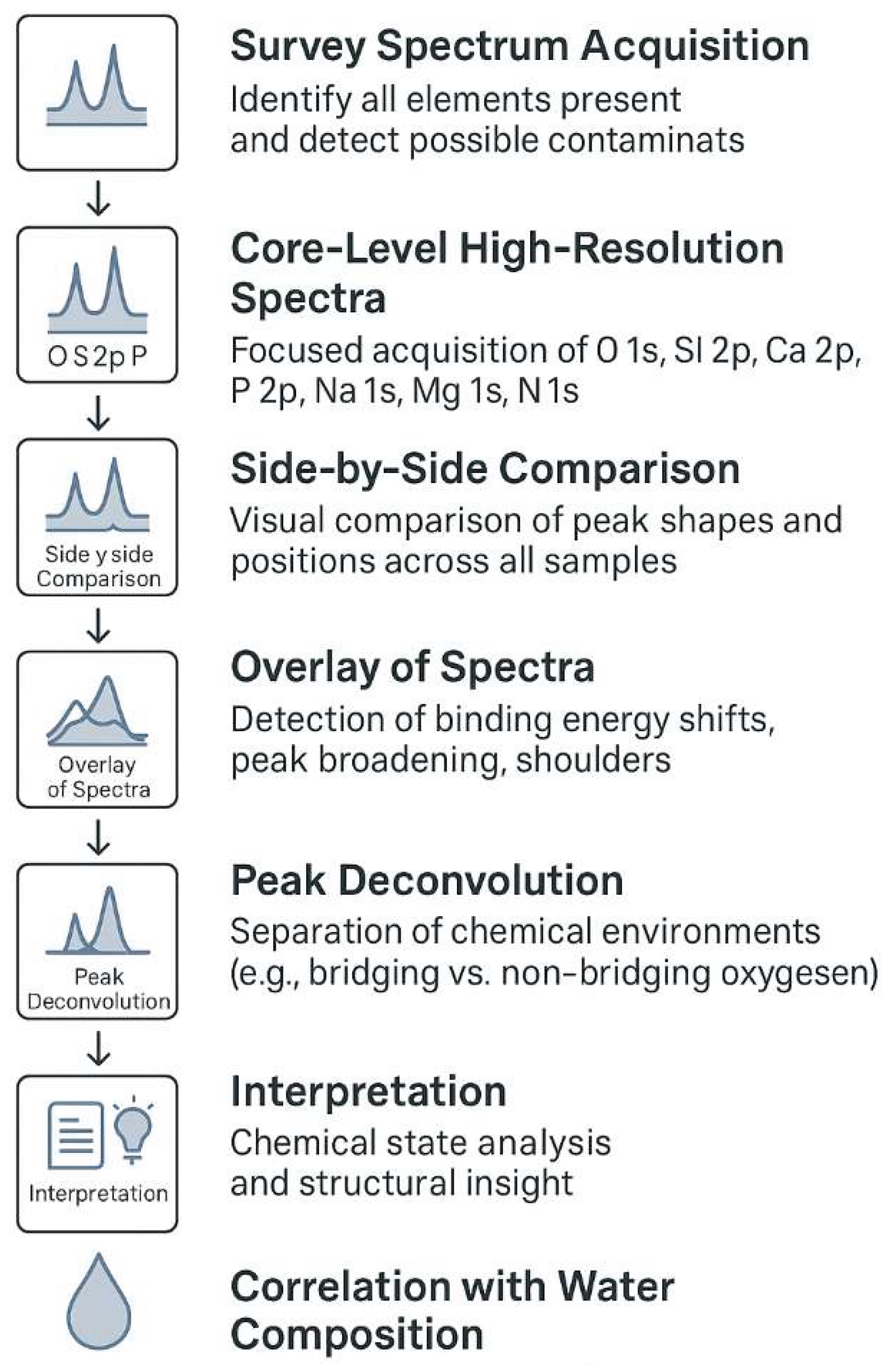

In order to interpret the surface chemistry of the synthesized glasses, XPS data were analyzed following a systematic workflow (

Figure 3) comprising two main stages. First, wide-range survey spectra were acquired to identify the elemental composition of each sample, detect any surface contaminants, and highlight differences related to the use of distinct water sources and synthesis conditions. This provided an overview of the chemical elements present on the surface and served as a baseline for deeper investigation. Second, high-resolution spectra of selected core levels — including O 1s, Si 2p, P 2p, Ca 2p, Na 1s, and, where applicable, Mg 1s — were collected and subsequently analyzed in detail. This included side-by-side comparison, spectral overlay, and deconvolution into individual chemical environments, allowing for the identification of shifts in binding energy, peak broadening, and changes in chemical state indicative of structural rearrangements or ion substitution. The results of this multi-step analysis are presented in the following sections and discussed in relation to the ionic profile and mineral complexity of the synthesis waters employed.

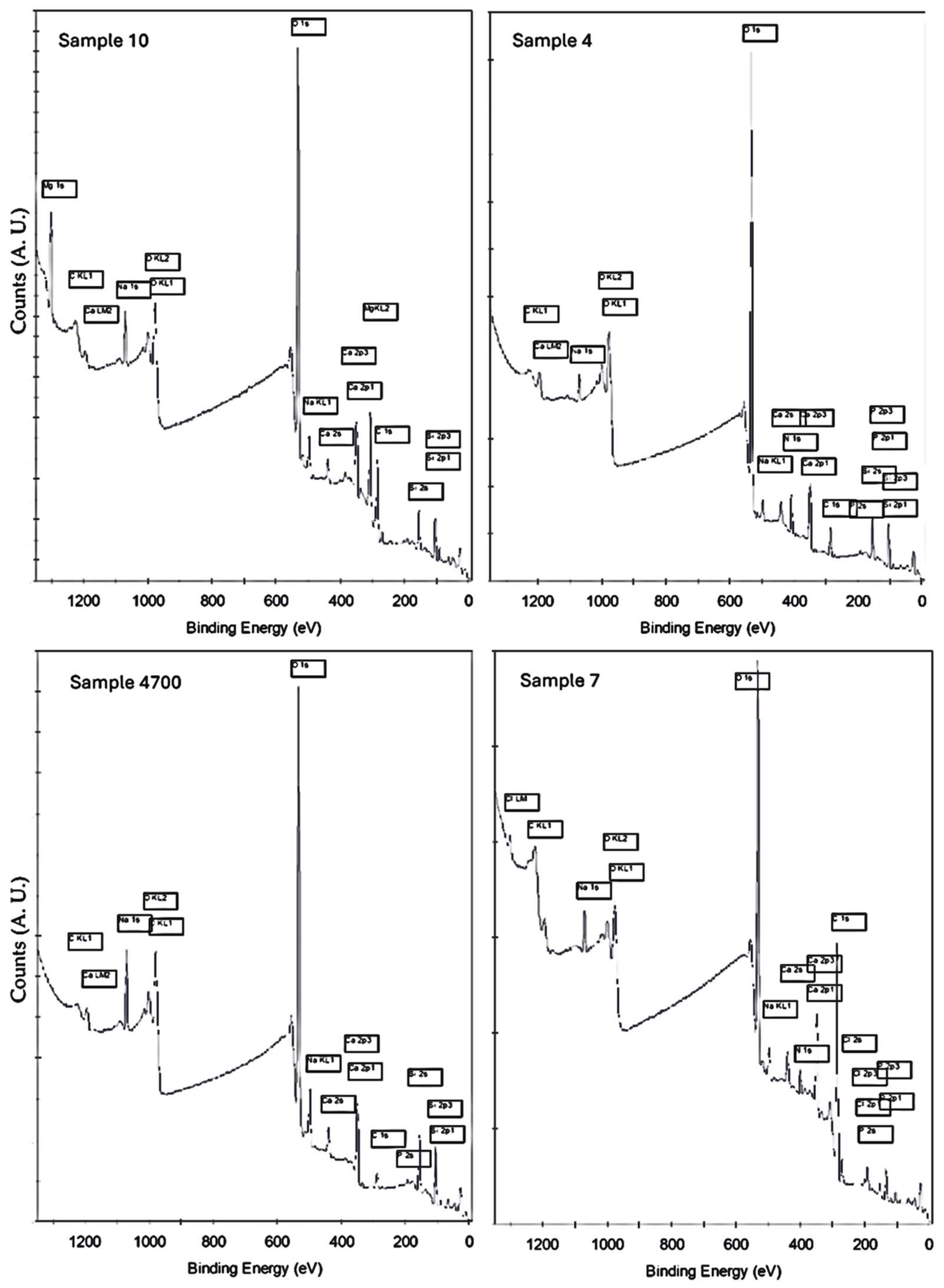

3.1.1. Survey

Survey XPS spectra of the sol-gel-derived bioactive glasses synthesized with different water sources reveal significant compositional and structural distinctions among the samples. All spectra show characteristic peaks of the main glass constituents—O 1s, Si 2p, P 2p, Ca 2p, and Na 1s—along with minor signals associated with synthesis reagents or trace elements introduced through the synthesis media. Variations in peak intensity, shape, symmetry, and full-width at half maximum (FWHM) reflect differences in both elemental distribution and the degree of local atomic ordering, network relaxation, and electronic environment [

24]. These spectral features provide insight into the effects of water composition and synthesis conditions on the surface chemistry and physical structure of the materials, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

In Sample 7, synthesized with deionized water (as a reference for the traditional 45S5 sol-gel glass), the survey spectrum presents the expected major peaks, including a strong O 1s signal at ~532.8 eV, narrow and intense Si 2p (~103.4 eV), a well-resolved Ca 2p doublet (~347.0 / 350.6 eV), and a symmetric P 2p at ~133.5 eV. A pronounced Na 1s peak at ~1072 eV further confirms good retention of this network modifier. In addition to these, Sample 7 uniquely exhibits two additional peaks in the low binding energy region: one near ~198 eV and another between ~155–165 eV. The former is attributed to Cl 2p, resulting from the HCl used to catalyze the sol-gel reaction. Its presence suggests incomplete removal of chloride species during drying or gelation. The second low-energy feature may stem from a Cl Auger satellite or minor sulfur species (e.g., S 2p), potentially introduced via reagent impurities or laboratory atmosphere [

25]. Most notably, Sample 7 shows a distinct N 1s signal at ~400 eV—absent or weak in the other samples—corresponding to surface-bound nitrate (NO₃⁻) from the sodium and calcium nitrate precursors [

26]. Since the synthesis used deionized water, lacking competing multivalent cations, electrostatic stabilization of these anions on the surface is enhanced, unlike in mineral water-based samples, where ionic exchange processes with cations like Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ may suppress nitrate adsorption. Together, these features confirm that even in a nominally “clean” system, reagent-derived anions can leave detectable surface residues.

Sample 4, synthesized with Água Prata, exhibits survey features closely resembling Sample 7, including strong O, Si, Ca, and P signals, but with slightly broadened Na 1s and O 1s peaks. This subtle broadening may be attributed to modifications in the local coordination environment or minor electronic redistribution induced by trace elements in the geothermal water. This suggests some ionic interaction from trace elements present in the geothermal water, but without major perturbation of the glass network.

Notably, no Cl or N peaks are observed, indicating more complete removal or displacement of these species. The absence of Mg-related peaks confirms the moderate ionic profile of Água Prata.

In Sample 4700—also synthesized with Água Prata but subjected to thermal treatment—the survey spectrum shows sharper and more intense Si 2p and Ca 2p peaks, consistent with increased network ordering and densification. The O 1s peak is more symmetric, indicating a greater fraction of bridging oxygens (BOs) [

22,

27]. These changes not only reflect improved structural ordering but also suggest a redistribution of bonding environments and local charge density. No residual Cl or N peaks are present, reinforcing the effect of both ionic balance in the water and heat-induced structural reorganization in reducing surface contamination.

In stark contrast, Sample 10—synthesized with highly mineralized Água Azeda and MgO addition—displays clear differences. A strong Mg 1s peak near ~1303 eV is exclusive to this sample, confirming magnesium incorporation. The Na 1s peak is strongly attenuated, likely due to ion exchange with Mg²⁺ and other multivalent cations (e.g., Fe³⁺, Zn²⁺) abundant in Água Azeda. The Ca 2p and P 2p peaks are both broadened and reduced in intensity, suggesting partial substitution or interference by competing cations. These spectral shifts also imply modification of the local electrostatic environment around core-level electrons and changes in bonding symmetry [

24].

The O 1s peak exhibits significant asymmetry, reflecting increased presence of non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) and disrupted silicate-phosphate network connectivity. Altogether, these features suggest that Sample 10 underwent physical reorganization of its short- and medium-range structure, with consequences for both chemical composition and electronic structure at the surface. These changes are typical of glasses undergoing modifier ion substitution [

28,

29], where foreign multivalent cations displace native Na⁺/Ca²⁺ species, leading to altered local environments.

The survey spectra strongly suggest that the synthesis water composition and thermal treatment influence the surface chemistry of the glasses. Deionized water tends to yield a compositionally cleaner surface, although enriched in Cl⁻ and NO₃⁻, likely stemming from precursor residues. Água Prata appears to introduce trace elements with potential benefits and, when combined with thermal treatment, enhances structural definition. Água Azeda, on the other hand, promotes marked structural changes, seemingly through extensive ion exchange involving magnesium, leading to a spectral signature with modifier depletion and increased network disorder.

3.1.2. O 1s Core-Level Analysis

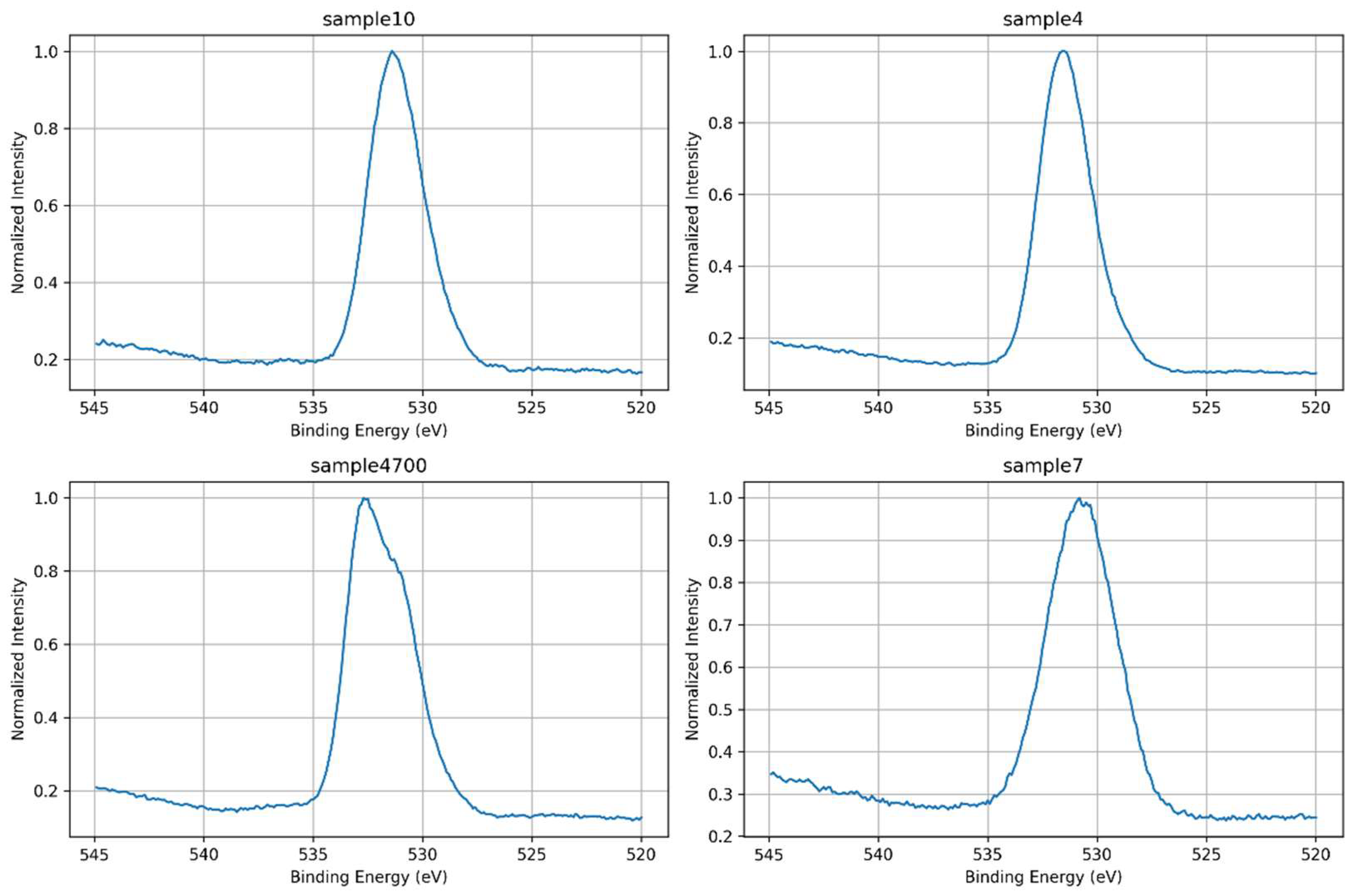

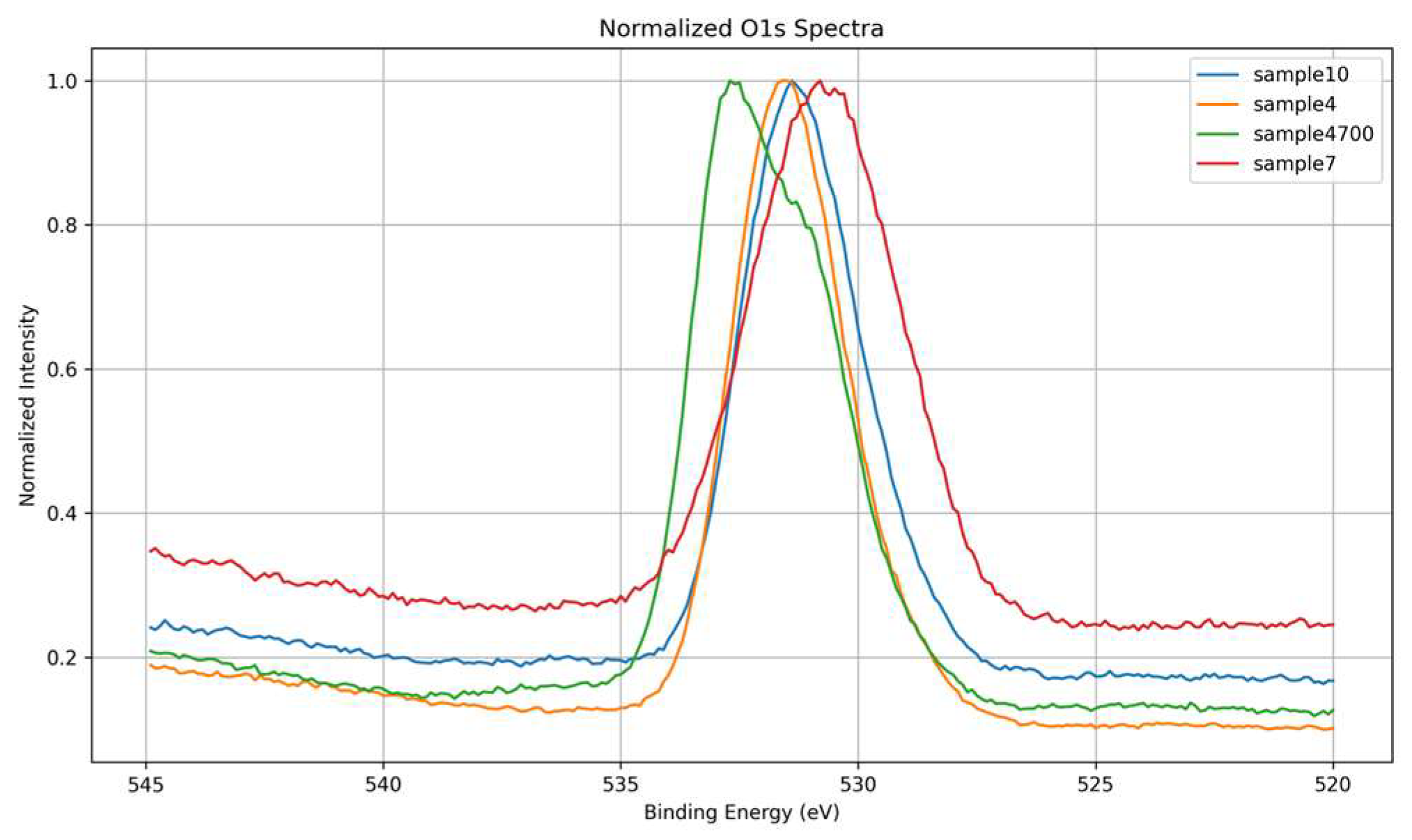

The O 1s core-level spectra of the four samples were carefully analyzed to investigate the chemical environment of oxygen atoms and assess the influence of water composition and thermal treatment on glass structure. As shown in

Figure 5, all samples display a dominant O 1s peak centered between ~531.0 and 532.8 eV, primarily reflecting contributions from bridging oxygens (BOs, e.g. Si–O–Si) and non-bridging oxygens (NBOs, such as Si–O⁻), associated with network modifiers like Na⁺, Ca²⁺, and Mg²⁺ [

22]. The overlaid spectra in

Figure 6 allow direct comparison of peak position, shape, and asymmetry.

Sample 7, synthesized with deionized water, serves as a reference since it shares the same base composition as Samples 4 and 4700. It exhibits the broadest and most symmetric O 1s peak, centered at the lowest binding energy among all samples. This shape suggests a relatively balanced distribution of BOs and NBOs, and a structurally homogeneous network with diffuse local disorder typical of sol-gel-derived glasses in the absence of ionic perturbation. Sample 4, synthesized with Água Prata, presents a narrower and slightly asymmetric peak with a mild shoulder at lower binding energies. Although compositionally equivalent to Sample 7, the difference in water source likely introduced ionic species (e.g., Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺) that mildly perturbed the network, increasing the fraction of NBOs and slightly altering the electronic environment. These cations replace native Na⁺ and Ca²⁺ network modifiers, increasing structural disorder and reactivity [

30]. Sample 4700, also synthesized with Água Prata but subjected to thermal treatment, displays a more pronounced left-side asymmetry, with a higher binding energy maximum. Instead of the expected narrowing due to densification, the appearance of a distinct shoulder at lower energies suggests persistent structural heterogeneity or the generation of new reactive oxygen environments. These may arise from partial network relaxation or residual reorganization processes post-heating. Finally, Sample 10, which differs from the others by replacing P₂O₅ with MgO in its composition and using Água Azeda, shows a peak shape similar to that of Sample 4. The O 1s envelope is slightly asymmetric toward lower binding energies, suggesting a moderate level of NBOs. The absence of phosphate simplifies the spectrum, while the presence of Mg²⁺ and waterborne ions may contribute to local structural variations, although not to the same extent as seen in thermally treated samples.

The observed variations in O 1s peak shape and width across samples reflect differences not only in network connectivity and modifier content but also in local bonding symmetry and electronic charge distribution. The position of the O 1s maximum shifts between samples, with Sample 4700 at the highest binding energy and Sample 7 at the lowest, indicating changes in the average oxygen bonding environment. The peak asymmetry, particularly in Samples 4 and 4700, reflects the degree of non-bridging oxygen formation and structural perturbation linked to both water composition and post-synthesis treatment. The spectra reveal how even subtle differences in synthesis conditions modulate the network structure, with mineral water-derived ions and thermal effects playing distinct roles in disrupting or modifying the silicate framework.

To further clarify the structural differences, the O 1s spectra were deconvoluted. This analysis resolves the total peak into components typically attributed to bridging oxygens (BO), non-bridging oxygens (NBO), and, in some cases, minor contributions from surface hydroxyls or adsorbed species.

The deconvoluted O 1s spectra, shown in

Figure 7 and summarized in

Table 2, reveal distinct differences in the relative contributions of bridging oxygens (Si–O–Si), non-bridging oxygens (Si–O⁻), and surface hydroxyl groups (Si–OH) across the samples, reflecting the impact of synthesis conditions and thermal treatment.

Sample 4, synthesized with Água Prata, displays a dominant Si–OH contribution (68.4%), accompanied by a relatively small fraction of Si–O⁻ (16.3%) and a minor Si–O–Si component (15.3%). This distribution suggests a highly disrupted silicate network, likely due to the presence of multivalent cations (e.g., Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺) introduced by the mineral water, which promote the formation of terminal –OH and NBOs at the expense of network connectivity. Upon thermal treatment (Sample 4700), this distribution changes dramatically: the Si–O–Si fraction becomes predominant (77%), with Si–OH reduced to 21% and Si–O⁻ nearly absent (2%). This shift reflects significant network densification and re-polymerization upon heating, as hydroxyl groups condense to form bridging linkages, decreasing reactivity and hydroxylation, and the glass matrix becomes more ordered.

In contrast, Sample 7, prepared with deionized water, exhibits a very high Si–OH content (75%) and a moderate amount of Si–O–Si (25%), characteristic of sol–gel glasses that remain hydrated and structurally open due to the absence of ionic modifiers.

Sample 10, with a distinct formulation (replacement of P₂O₅ by MgO) and synthesized using Água Azeda, shows a near balance between Si–OH (49.2%) and Si–O–Si (50.8%), suggesting moderate hydroxylation and structural polymerization. The lack of a distinct Si–O⁻ peak may result from a reduced presence of strong network modifiers or a different ion distribution associated with Água Azeda. The spectrum remains similar in shape to Sample 4, but the reduced hydroxyl signal and absence of NBOs indicate a more ordered network.

3.1.3. Si 2p Core-Level Analysis

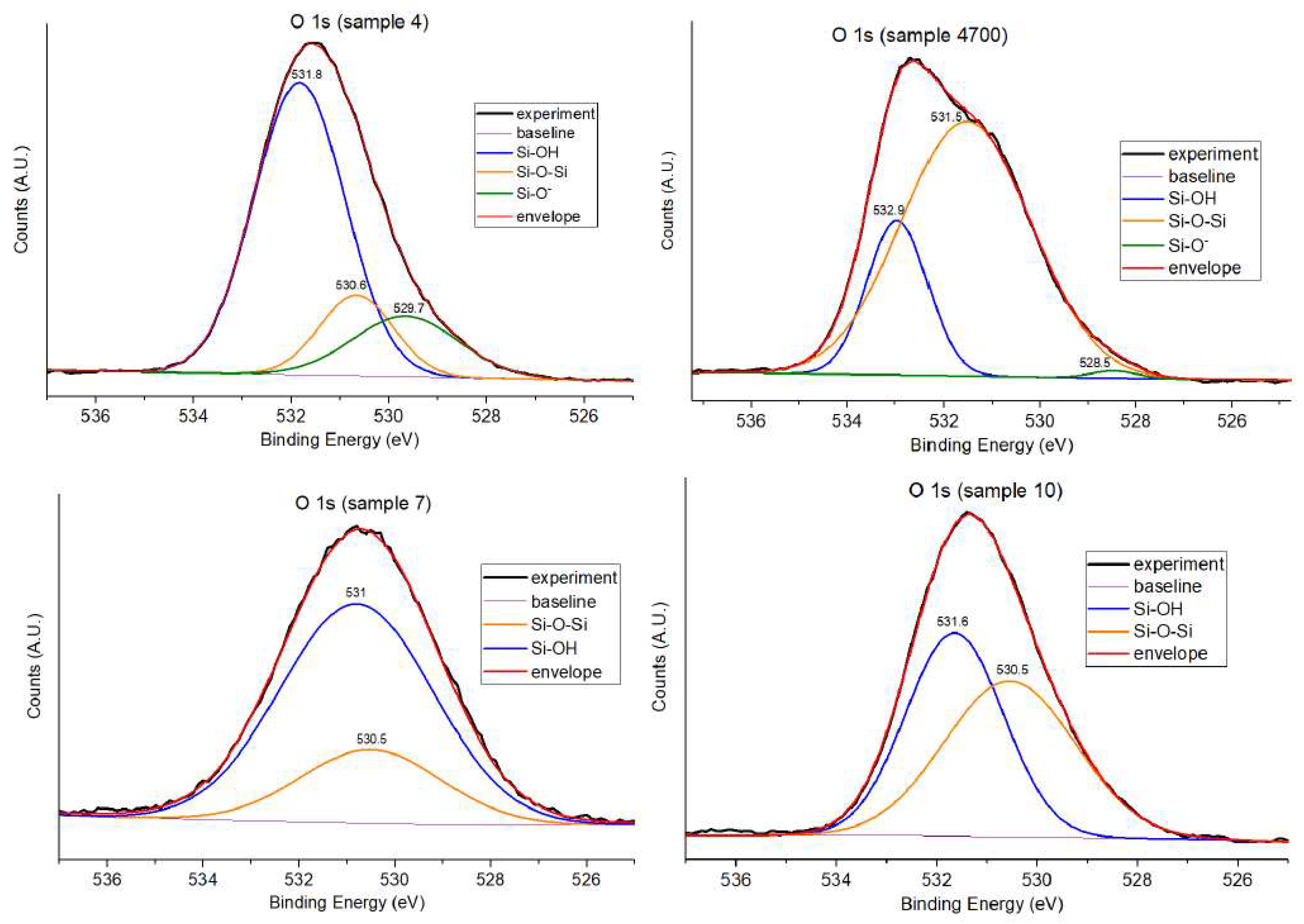

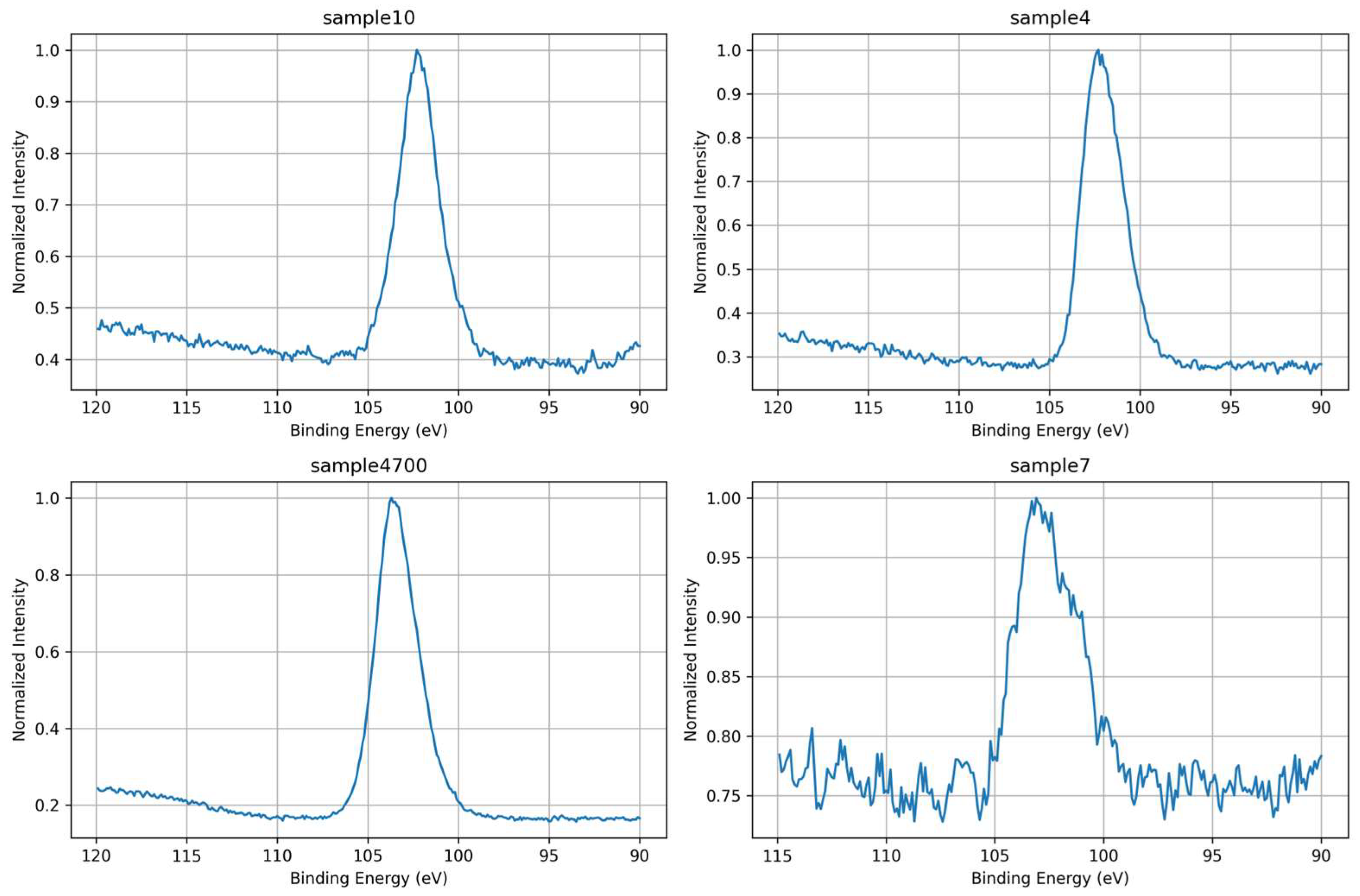

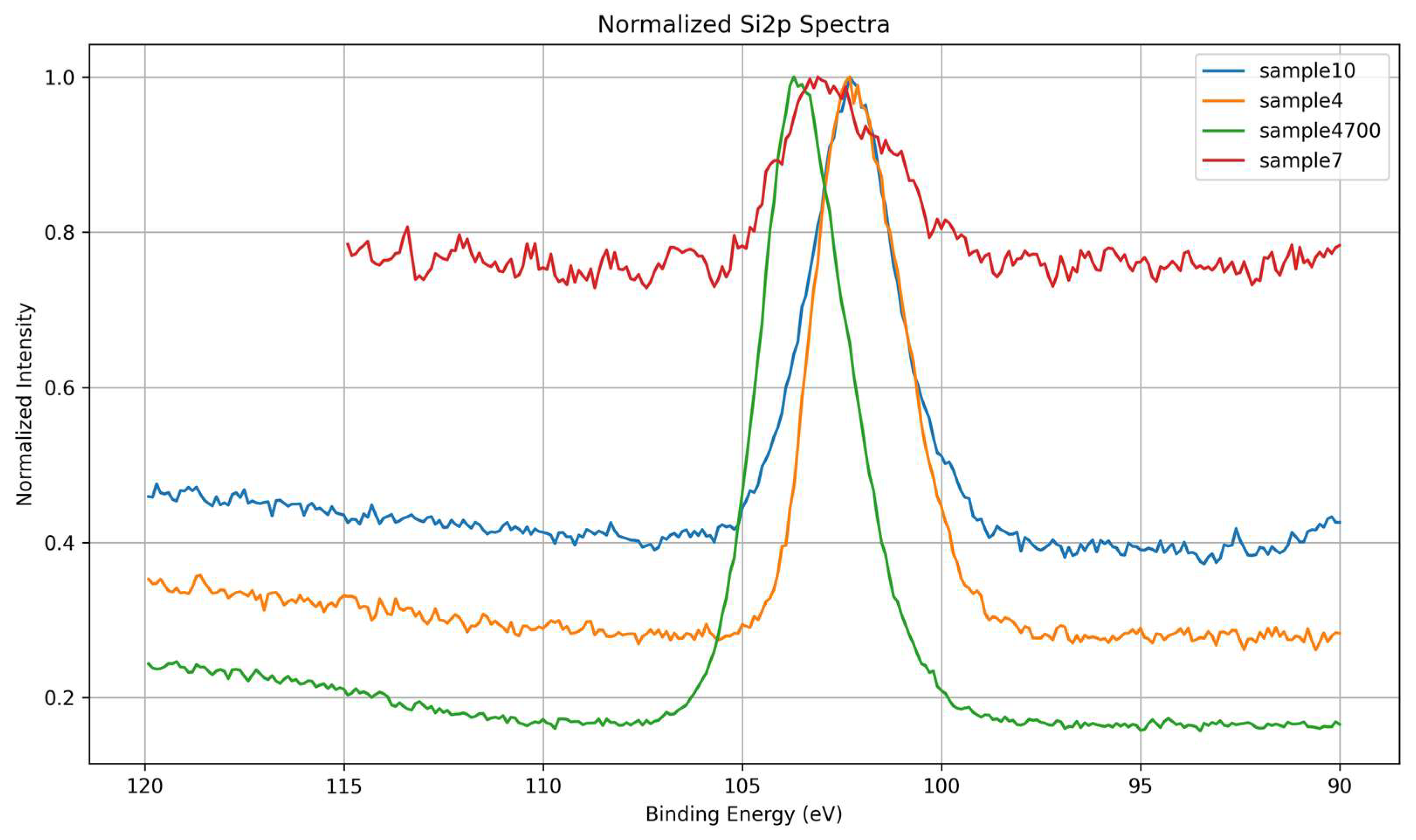

High-resolution Si 2p spectra were analyzed to assess the structural state of silicon within the glass network and its response to variations in synthesis conditions. As shown in

Figure 8, all samples exhibit a primary Si 2p peak centered near ~103.4 eV, characteristic of silicon in fully oxidized tetrahedral coordination (Si⁴⁺) within SiO₄ units. The overlaid spectra in

Figure 9 highlight differences in peak sharpness and subtle shifts in binding energy, reflecting variations in silicate network connectivity and local electronic environments.

Samples 4, 4700, and 10 exhibit narrow and well-defined Si 2p peaks, indicating relatively ordered silicon environments and a higher degree of network polymerization. These findings are consistent with their O 1s spectra, where a higher proportion of bridging oxygens (Si–O–Si) was observed, particularly in Samples 4700 and 10. This correlation supports the interpretation that enhanced structural coherence at the oxygen level translates into more resolved silicon environments.

Conversely, Sample 7, synthesized with deionized water, presents the broadest and least resolved Si 2p signal. This broadened profile suggests a more disordered network and a wider distribution of Si bonding geometries. Notably, this sample also displayed the highest proportion of surface hydroxyls (Si–OH) and a comparatively lower fraction of bridging oxygens in the O 1s deconvolution. These features point to a less cross-linked network with a greater number of terminal Si–O⁻ or Si–OH units, which contribute to the electronic inhomogeneity detected in the Si 2p signal.

Therefore, the Si 2p results complement and reinforce the O 1s analysis, collectively suggesting that synthesis conditions (such as ionic content of the water and post-synthesis heat treatment) not only affect oxygen speciation but also significantly modulate the silicon coordination environment and network order.

The observed spectral differences reveal a strong interplay between network connectivity (as indicated by BO/NBO ratios) and the electronic structure of silicon, as probed by the Si 2p core level.

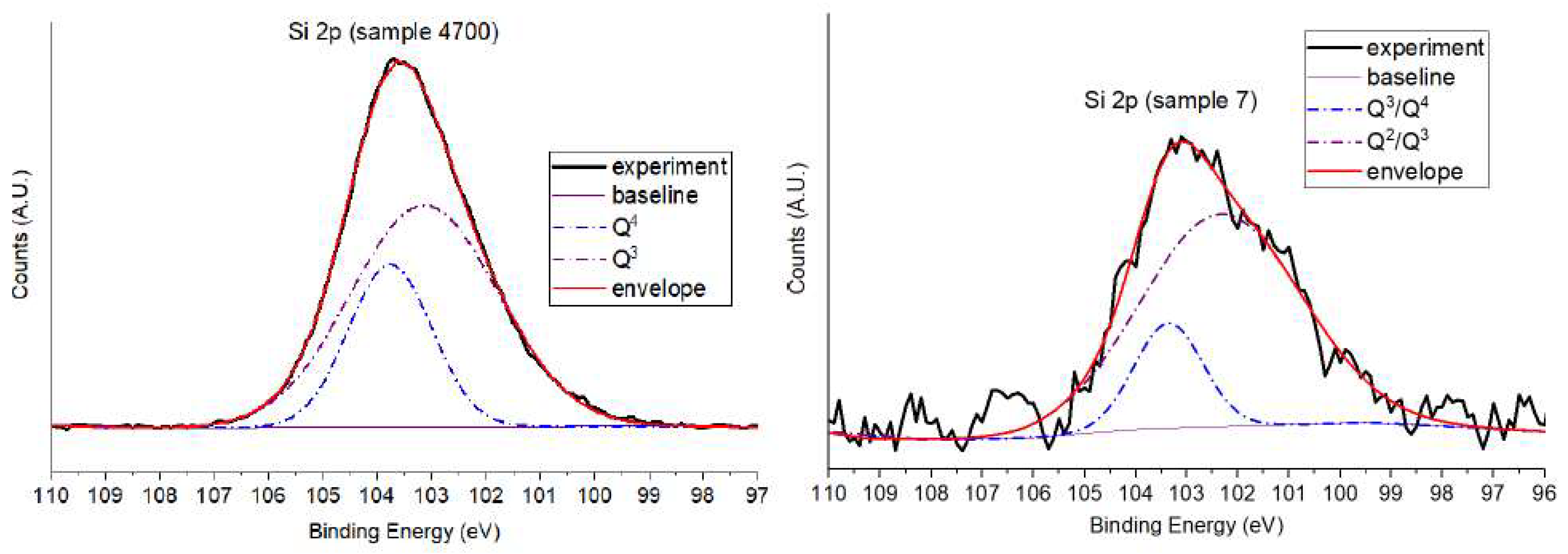

To gain deeper insight into the differences in silicon coordination and local disorder, the Si 2p spectra of Samples 7 and 4700 were deconvoluted. These two samples were chosen as structural extremes: Sample 7, representing a less condensed network with higher disorder, and Sample 4700, reflecting a more densified and ordered structure due to thermal treatment.

Figure 10 presents the deconvoluted Si 2p spectra of both samples.

The Si 2p spectrum of Sample 4700 displayed two distinct components at 103.1 eV (70.6%) and 103.7 eV (29.4%), attributed to Q³ and Q⁴ environments, respectively. These species are indicative of a highly polymerized silicate network, enriched in bridging oxygens (BOs) and exhibiting greater structural order. This assignment agrees with the reduced hydroxyl content previously observed in the O 1s spectrum and reflects the formation of densified silicate domains through thermal treatment [

22]. The presence of a significant high-BE Q⁴ component suggests extensive Si–O–Si crosslinking characteristic of fully connected silicate tetrahedra.

In contrast, Sample 7 exhibited two broader components centered at 102.4 eV (82.4%) and 103.3 eV (17.6%), corresponding to overlapping Q²/Q³ and Q³/Q⁴ species, respectively. These features indicate a less polymerized and more disordered network, rich in non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) and terminal silanol groups (Si–OH). This interpretation is consistent with the high fraction of Si–OH and NBOs detected in the O 1s spectra, confirming a loosely connected silicate structure. The lower binding energy component is mainly associated with Q² or Q³ environments, which are characteristic of open, low-connectivity silicate networks.

These assignments align with previous studies, where Si 2p components near ~102.4 eV and ~103.3 eV were linked to less polymerized Q²/Q³ units and intermediate Q³/Q⁴ transitions, respectively, in silicate systems undergoing structural reorganization [

22]. The comparison clearly illustrates a shift toward higher binding energy and polymerization from Sample 7 to Sample 4700, reflecting the increasing degree of network connectivity, dominated by bridging oxygens (BOs).

Peak assignments are based on the Qⁿ classification of silicate structural units, where:

These results highlight the strong correlation between silicon’s core-level electronic environment and the extent of silicate network polymerization. The progression from Q²/Q³-dominated spectra in Sample 7 to Q³/Q⁴-rich spectra in Sample 4700 highlights the significant structural reorganization induced by post-synthesis thermal treatment. Moreover, this analysis corroborates the trends observed in the O 1s data, offering complementary atomic-scale evidence of the evolving glass network structure. A summary of these findings is presented in

Table 3.

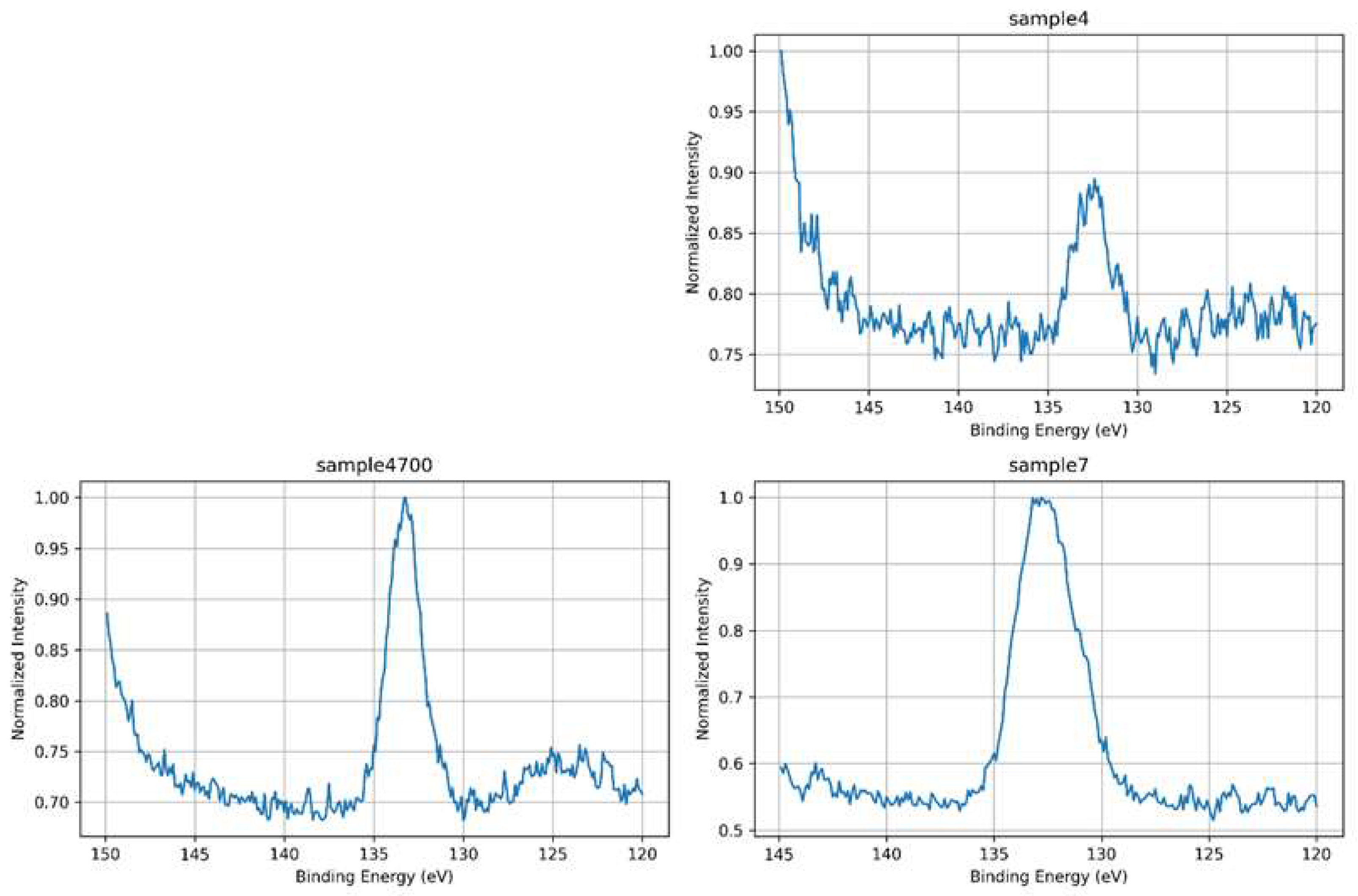

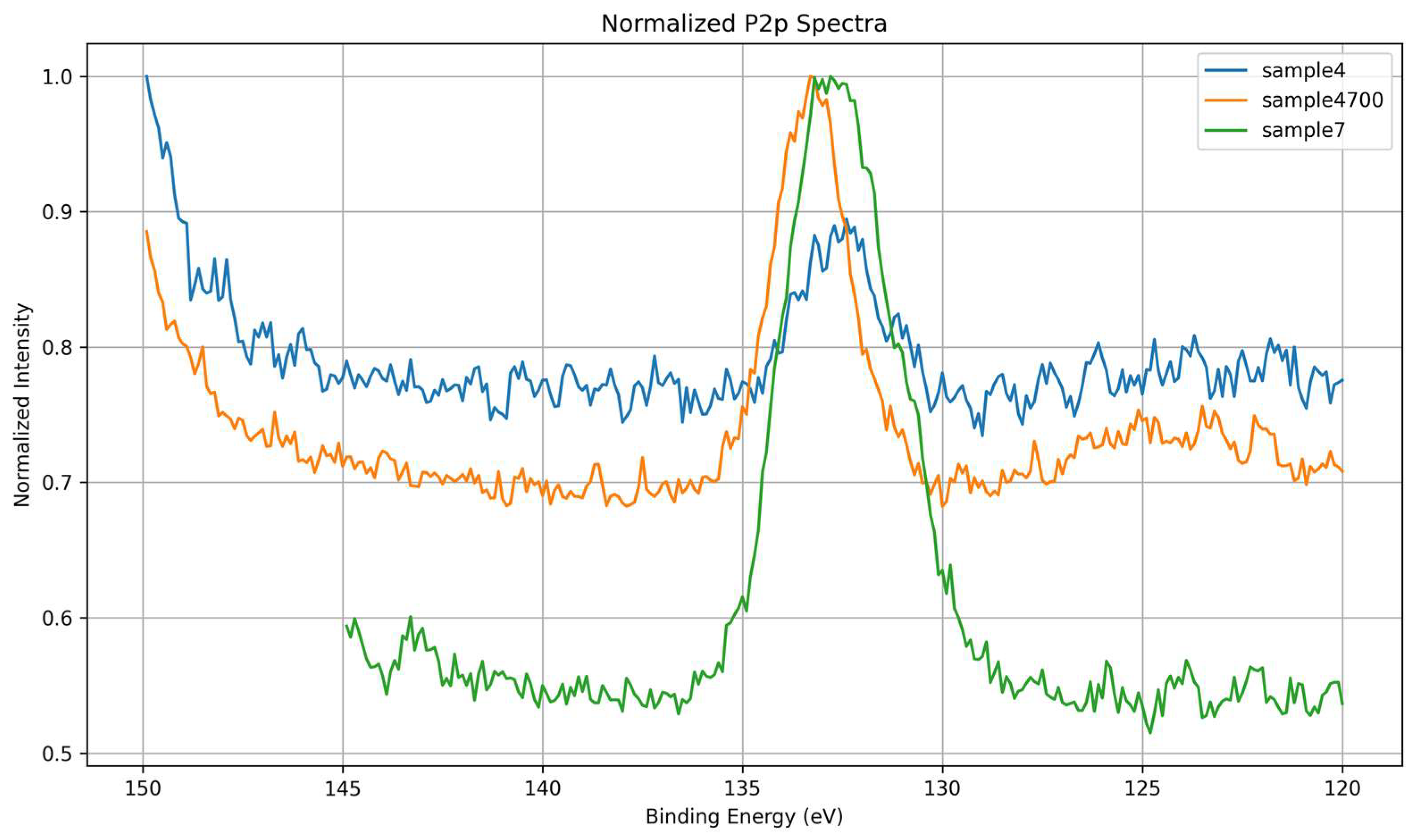

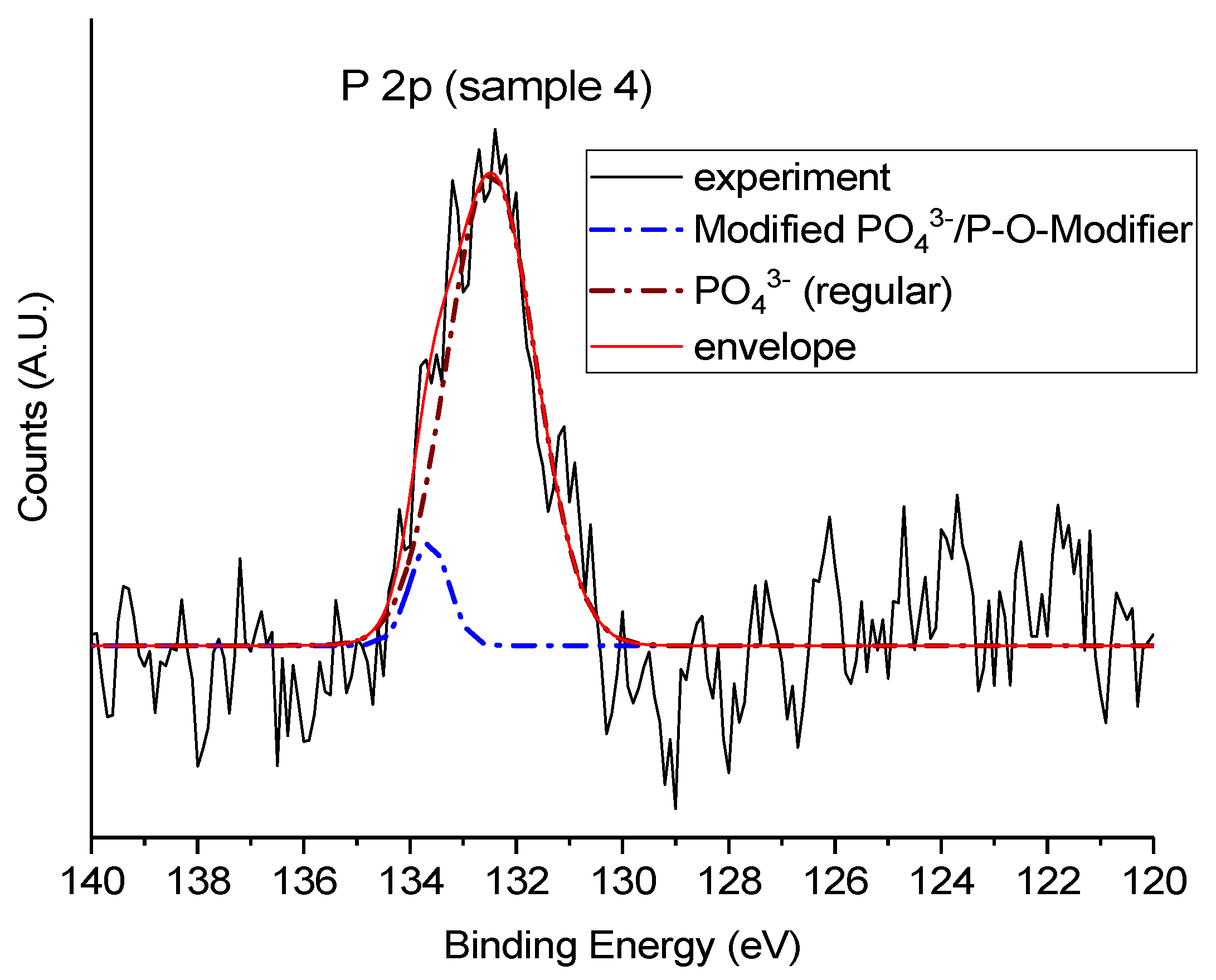

3.1.4. P 2p Core-Level Analysis

High-resolution P 2p spectra were examined to assess the local chemical environment of phosphorus within the silicate-phosphate network and to evaluate how synthesis conditions and thermal treatment influence phosphate incorporation. P 2p spectra were acquired only for phosphorus-containing samples; Sample 10 was excluded from this analysis due to its phosphate-free formulation. As shown in

Figure 11, all analyzed samples exhibit a P 2p envelope centered around ~133.5 eV, consistent with phosphorus in fully oxidized tetrahedral coordination (PO₄³⁻ units). The overlaid spectra in

Figure 12 reveal substantial differences in peak shape, width, and symmetry, which reflect variations in the phosphate environment and its interaction with the surrounding matrix.

Sample 7, synthesized with deionized water, displays the most intense P 2p peak among all samples, despite its relatively broad and symmetric profile. This suggests that phosphate groups are present in higher relative surface concentration but are embedded in a structurally under consolidated network. The absence of thermal treatment likely results in incomplete condensation and greater variability in local bonding geometries. While the chemical environment is clean and free of interfering multivalent cations, the local electrostatic environment remains less defined, as indicated by the broadened peak. This spectral profile reflects strong P–O bonding within PO₄³⁻ units distributed in electronically diverse coordination shells.

Sample 4, prepared using Água Prata, exhibits the lowest P 2p intensity and a broader, less defined envelope compared to Sample 4700. Although ions such as Sr²⁺ or Zn²⁺ may act as stabilizers, they can also introduce electrostatic heterogeneity through local charge imbalance or competition for coordination, thereby broadening the spectral response. The reduced signal may reflect a lower surface availability of phosphate species or a suppressed photoemission yield due to modifier interaction.

Sample 4700, synthesized with the same water but subjected to thermal treatment, shows an intermediate P 2p intensity but the narrowest and most symmetric peak of all samples. This spectral sharpening indicates enhanced phosphate network ordering and stabilization via heat-induced compaction and the removal of labile surface species. The reduced peak asymmetry and increased definition are consistent with improved local symmetry, decreased electrostatic fluctuations, and uniform bonding conditions around phosphorus atoms.

The evolution of the P 2p signal across these samples illustrates how both structural and electronic factors influence the spectroscopic response. Thermal treatment promotes phosphate consolidation and charge stabilization (Sample 4700), while the chemical complexity of the water source introduces ionic perturbations and electrostatic heterogeneity (Sample 4). The observed correlation between spectral broadening and local disorder, as well as peak sharpening with structural densification, underscores the dual role of the P 2p signal as both a chemical and physical probe of network integrity. These findings highlight how core-level line shapes can be used to infer local symmetry, charge distribution, and relaxation mechanisms in phosphate-bearing silicate glasses.

Given the pronounced asymmetry and broadening observed in the P 2p spectrum of Sample 4, a deconvolution was performed to resolve potential contributions from multiple phosphate environments. In contrast, the sharper and more symmetric peaks observed in Samples 7 and 4700 suggest a chemically homogeneous phosphorus environment, dominated by tetrahedral PO₄³⁻ units, and therefore did not warrant additional spectral fitting.

Figure 13 shows the deconvoluted P 2p spectrum of Sample 4, revealing two components centered at approximately 132.5 eV and 133.6 eV. The main peak at 132.5 eV (dominant in intensity) is attributed to fully oxidized phosphate units (PO₄³⁻), in line with the expected structure of silicate–phosphate glasses.

The minor component at 133.6 eV, though much less intense, indicates the presence of perturbed phosphate environments, likely resulting from the interaction with network-modifying cations such as Sr²⁺ and Zn²⁺ from the Água Prata synthesis medium. These ions can distort local charge distributions and alter the electronic environment of phosphate groups, thereby shifting the binding energy slightly higher.

This spectral profile aligns with previous XPS studies reporting that even a single apparent P 2p peak may consist of overlapping contributions from chemically distinct phosphate species. Bonding variations involving Si–O–P, O–P–O, or P–O–metal linkages (e.g., P–O–Na, P–O–Ca) may lead to subtle shifts that are not always resolvable without deconvolution [

31].

In this context, the dual-component spectrum of Sample 4 reflects a chemically heterogeneous phosphate environment, shaped by the ionic composition of the synthesis water. In contrast, Samples 7 and 4700 showed no such heterogeneity and were adequately modeled with a single PO₄³⁻ peak, consistent with a more uniform coordination state.

These two phosphate environments are summarized in

Table 4. The main peak at ~132.5 eV corresponds to fully oxidized, tetrahedrally coordinated PO₄³⁻ units, whereas the minor component at ~133.6 eV likely arises from phosphate groups interacting with network-modifying cations (e.g., Sr²⁺ or Zn²⁺), leading to a slight shift in binding energy due to local charge redistribution and coordination variability.

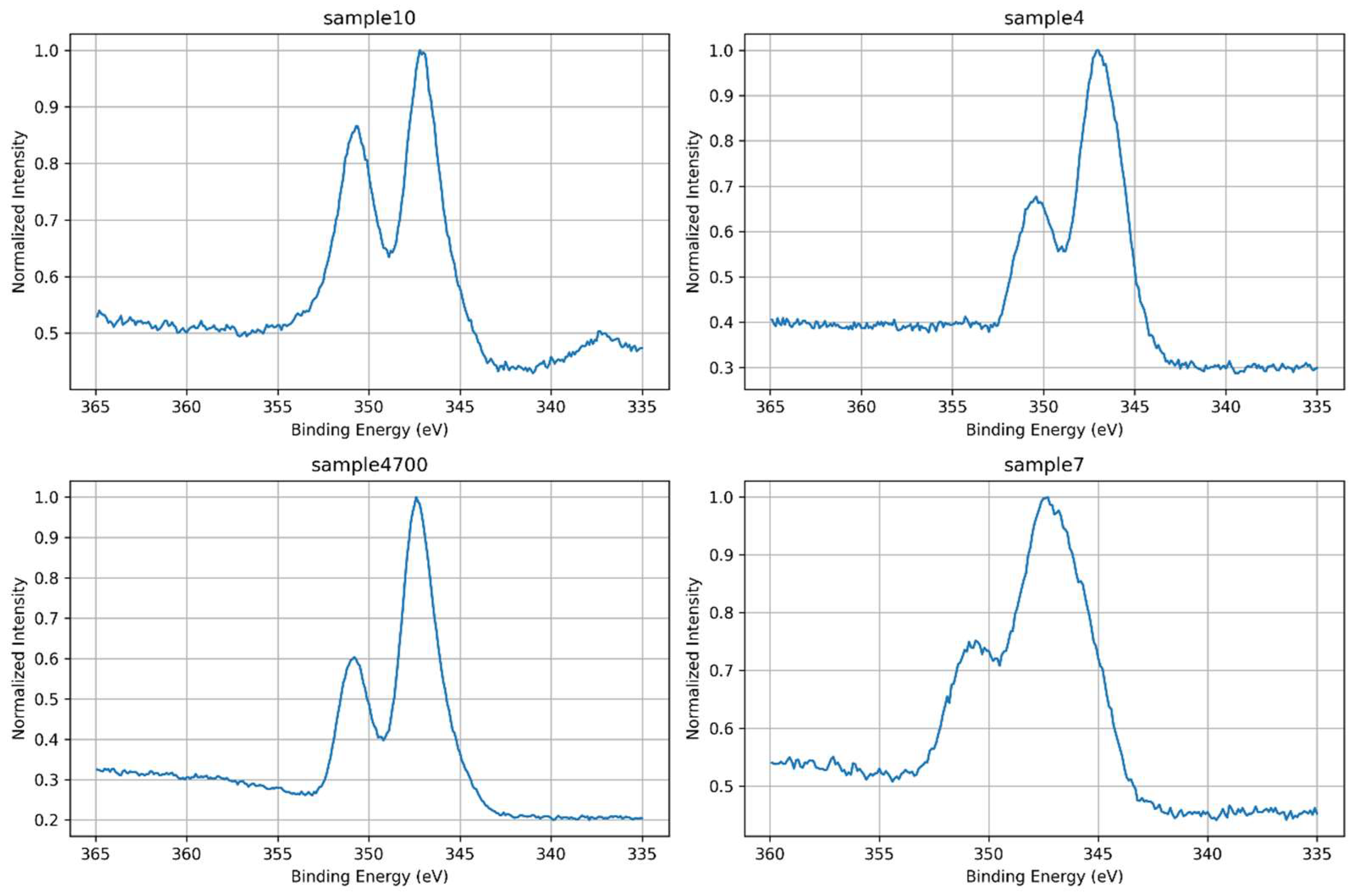

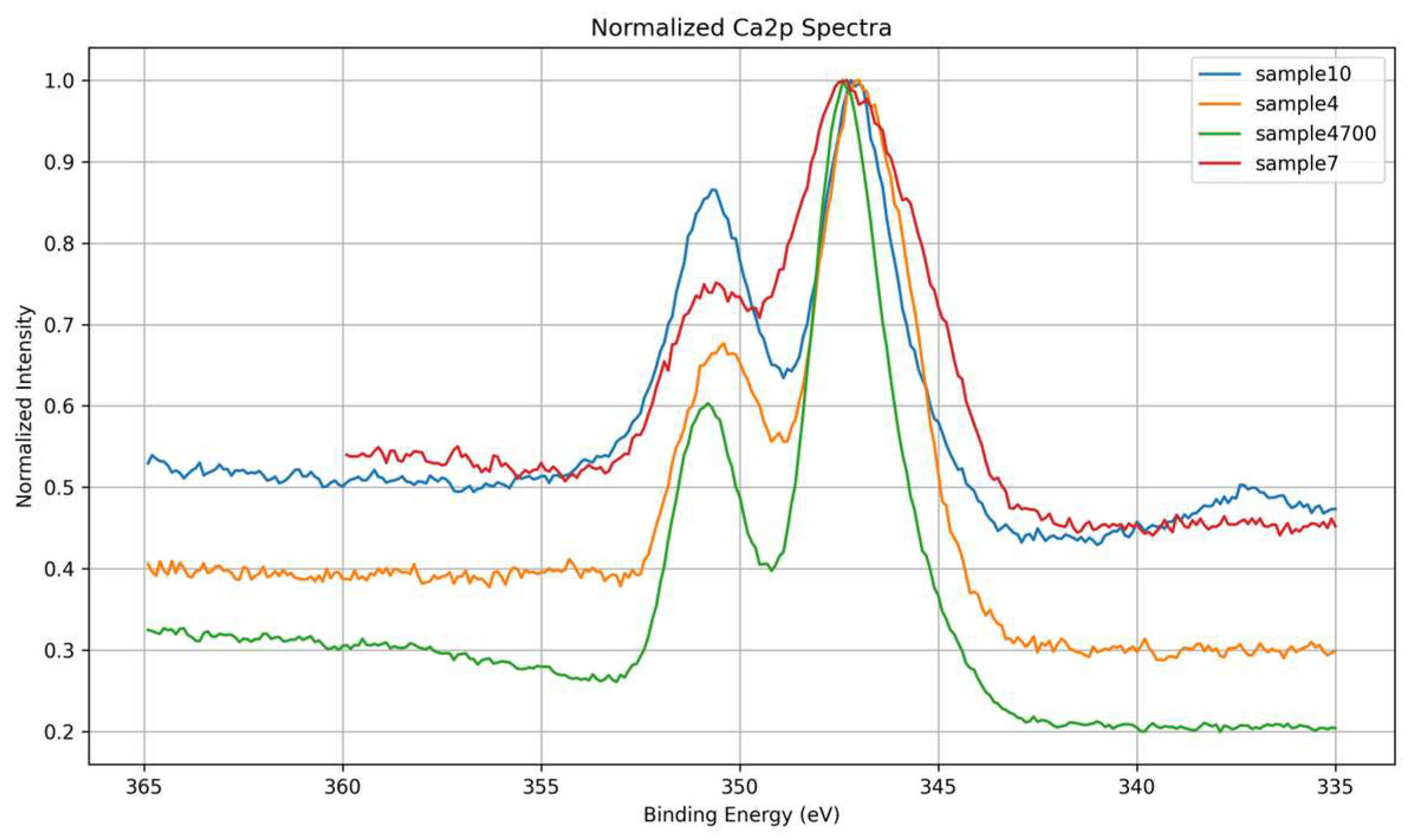

3.1.5. Ca 2p Core-Level Analysis

High-resolution Ca 2p spectra were analyzed to investigate the chemical environment and coordination states of calcium across the different glass compositions. All samples exhibit the characteristic spin–orbit doublet of Ca 2p₃/₂ and Ca 2p₁/₂, located near 347.2 eV and 350.7 eV, respectively, consistent with divalent calcium species. However, variations in peak width, intensity, and symmetry were observed among the samples, reflecting differences in local ordering, bonding environments, and the influence of synthesis conditions. These spectral variations are clearly illustrated in

Figure 14, which compares the high-resolution Ca 2p spectra across all samples.

Sample 4700, prepared with Água Prata and subjected to thermal treatment, displays the narrowest and most intense Ca 2p doublet, indicating a highly ordered coordination environment. The spectral sharpness suggests that thermal densification promotes network consolidation and electrostatic uniformity around Ca²⁺ ions, leading to enhanced photoemission definition.

Sample 4, also prepared with Água Prata but without thermal treatment, exhibits broader and less intense peaks. This intermediate behavior highlights the competing effects of ionic complexity in the synthesis medium and the absence of thermal consolidation, which limits structural organization and increases chemical heterogeneity.

Sample 10, synthesized with Água Azeda and no phosphate precursors, serves as a phosphate-free control. Its spectrum is sharper than those of Samples 4 and 7, and no signs of phosphate-associated components are present. This simpler spectral profile reflects a chemically uniform Ca–O–Si coordination environment and reinforces its role as a reference for silicate bonding without interference from phosphate species.

Sample 7, prepared using deionized water and phosphate precursors, displays the broadest and most asymmetric Ca 2p spectrum, indicating a highly disordered local environment and the coexistence of multiple calcium coordination states.

To better highlight differences in line shape and intensity,

Figure 15 shows the normalized Ca 2p spectra overlaid. The spectrum of Sample 4700 is notably the sharpest and most intense, consistent with high coordination order due to thermal treatment. In contrast, the broader and less defined profiles of Samples 7 and 10 reflect increased structural disorder and electrostatic heterogeneity.

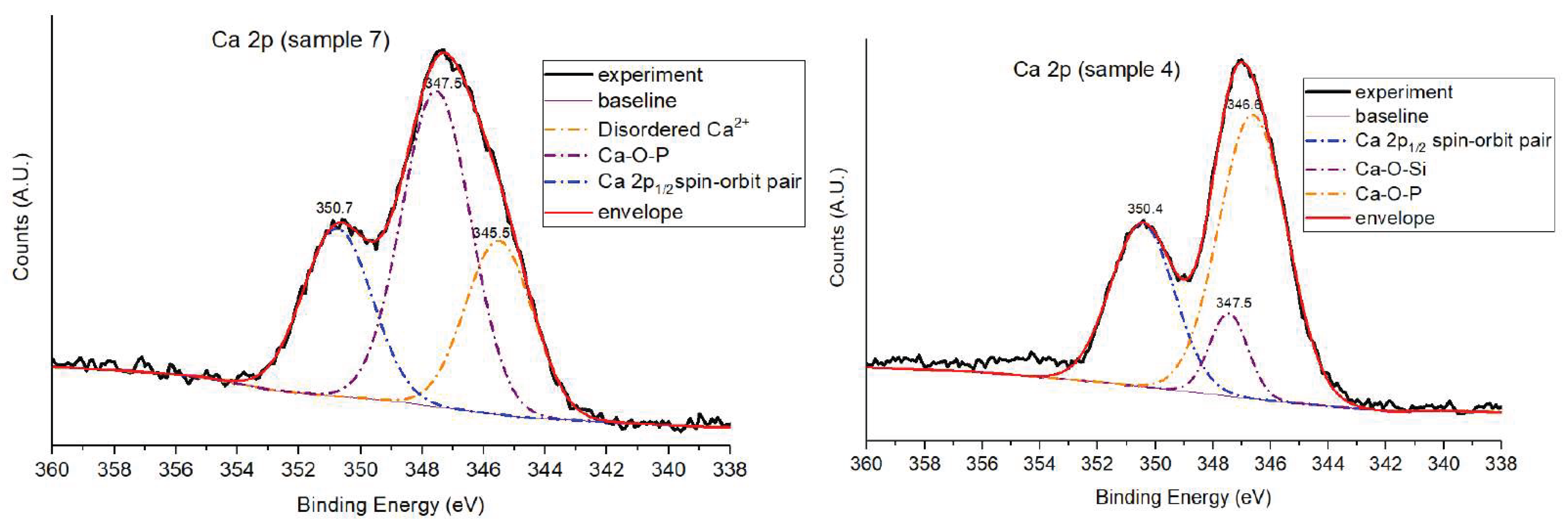

Given the pronounced broadening and asymmetry observed in the Ca 2p spectra of Samples 4 and 7, a deconvolution procedure was applied to resolve overlapping contributions from distinct calcium environments (

Figure 16). However, samples 4700 and 10 did not require deconvolution. The narrow, symmetric profiles observed in these samples suggest chemically uniform calcium coordination environments. In Sample 4700, thermal treatment stabilizes the network, while in Sample 10, the absence of phosphate simplifies the coordination to Ca–O–Si only.

Deconvolution of the Ca 2p spectra revealed the presence of three distinct components. In both samples, the primary Ca 2p₃/₂ signal appears at ~346.6–347.5 eV, assigned to calcium coordinated with phosphate groups (Ca–O–P), and is accompanied by its Ca 2p₁/₂ spin–orbit counterpart near 350.4–350.7 eV. However, Sample 7 exhibits a third, lower binding energy feature at 345.5 eV, absent in Sample 4, which is interpreted as calcium in a more weakly bound or hydrated environment—possibly related to surface Ca(OH)₂ or non-integrated Ca²⁺ species resulting from sol-gel processing in ultrapure water. In Sample 4, the Ca–O–P environment dominates (58.8%), with a smaller contribution (9.6%) assigned to calcium incorporated into the silicate network (Ca–O–Si). The absence of the low-BE component suggests a more stabilized coordination framework, likely supported by the presence of multivalent cations (e.g., Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺) from the mineral-rich synthesis medium, which may compete with calcium for phosphate binding and promote structural integration.

In contrast, Sample 7 shows a more heterogeneous calcium distribution, with substantial contributions from both Ca–O–P (48.3%) and the low-BE disordered component (25.9%), reflecting incomplete coordination and structural hydration. This behavior is typical of sol–gel glasses formed in the absence of ionic competition or post-synthetic stabilization.

The Ca–O–P environments identified here — representing calcium phosphate coordination reflect local bonding between Ca²⁺ and PO₄³⁻ groups in disordered, amorphous regions within the sol–gel matrix. These phosphate-rich domains are typical of glasses synthesized without thermal treatment, where limited condensation allows for nanoscale segregation or clustering of modifier cations around phosphate species.

In Sample 7, the exclusive detection of Ca–O–P environments (alongside the disordered species) reflect the chemically simple nature of the synthesis medium — ultrapure water without multivalent cations. Under these conditions, calcium displays strong affinity for phosphate groups, leading to preferential coordination as Ca–O–P clusters. The lack of Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺, or other modifiers prevents redistribution of Ca²⁺ into the silicate network. Moreover, the absence of thermal treatment limits network densification and inhibits calcium incorporation into silicate domains, which explains the absence of a distinct Ca–O–Si component in the deconvolution. The quantitative contributions of the different calcium environments in both samples are summarized in

Table 5.

This interpretation aligns with previous findings [

32], which show that although the Ca 2p doublet is typically the dominant spectral feature, deconvolution is often necessary to uncover underlying heterogeneity—such as surface carbonates, phosphate coordination, or partial network integration. These effects are particularly pronounced in low-temperature sol–gel systems, where limited thermal energy hinders the stabilization of well-defined coordination environments.

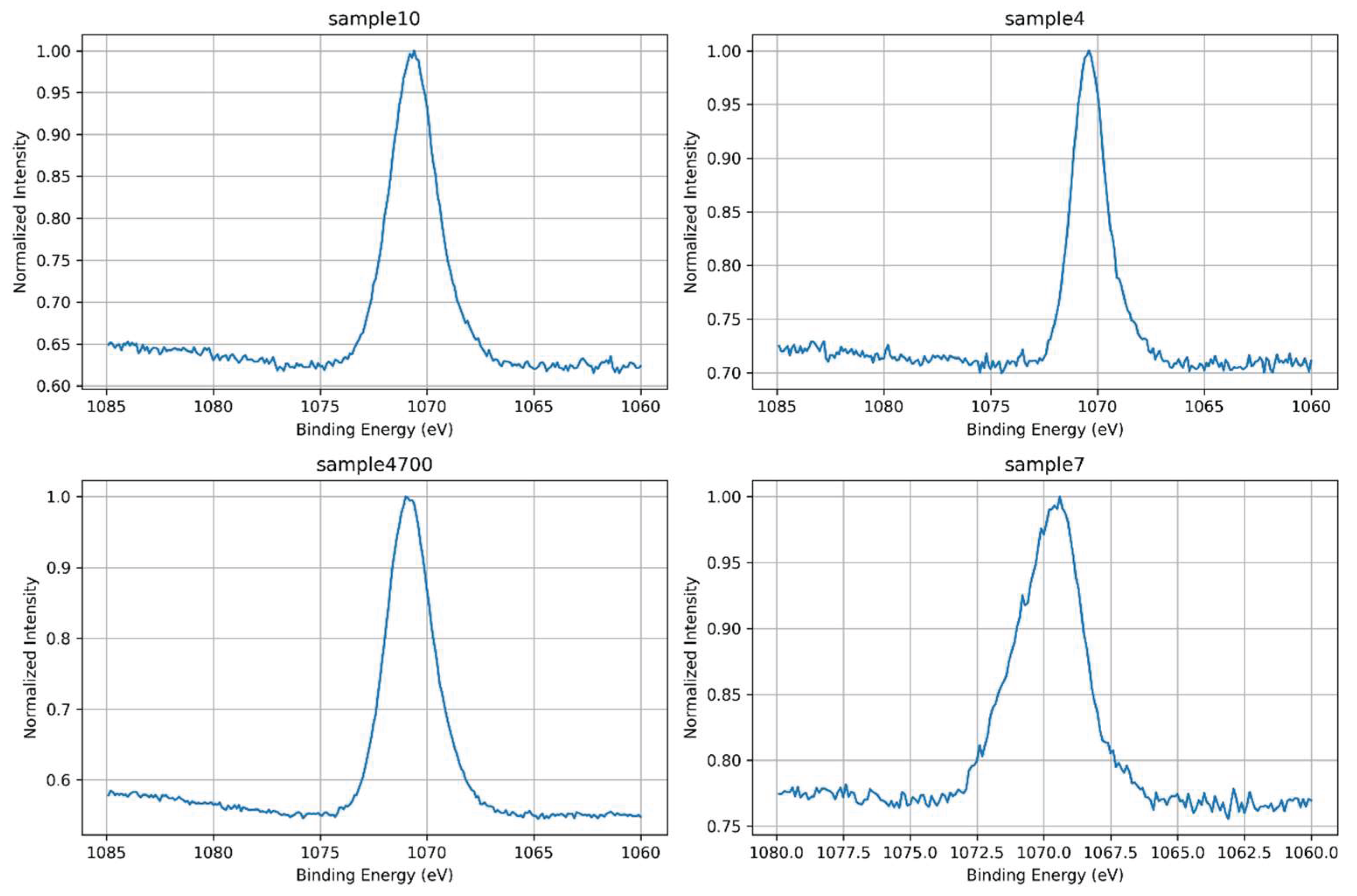

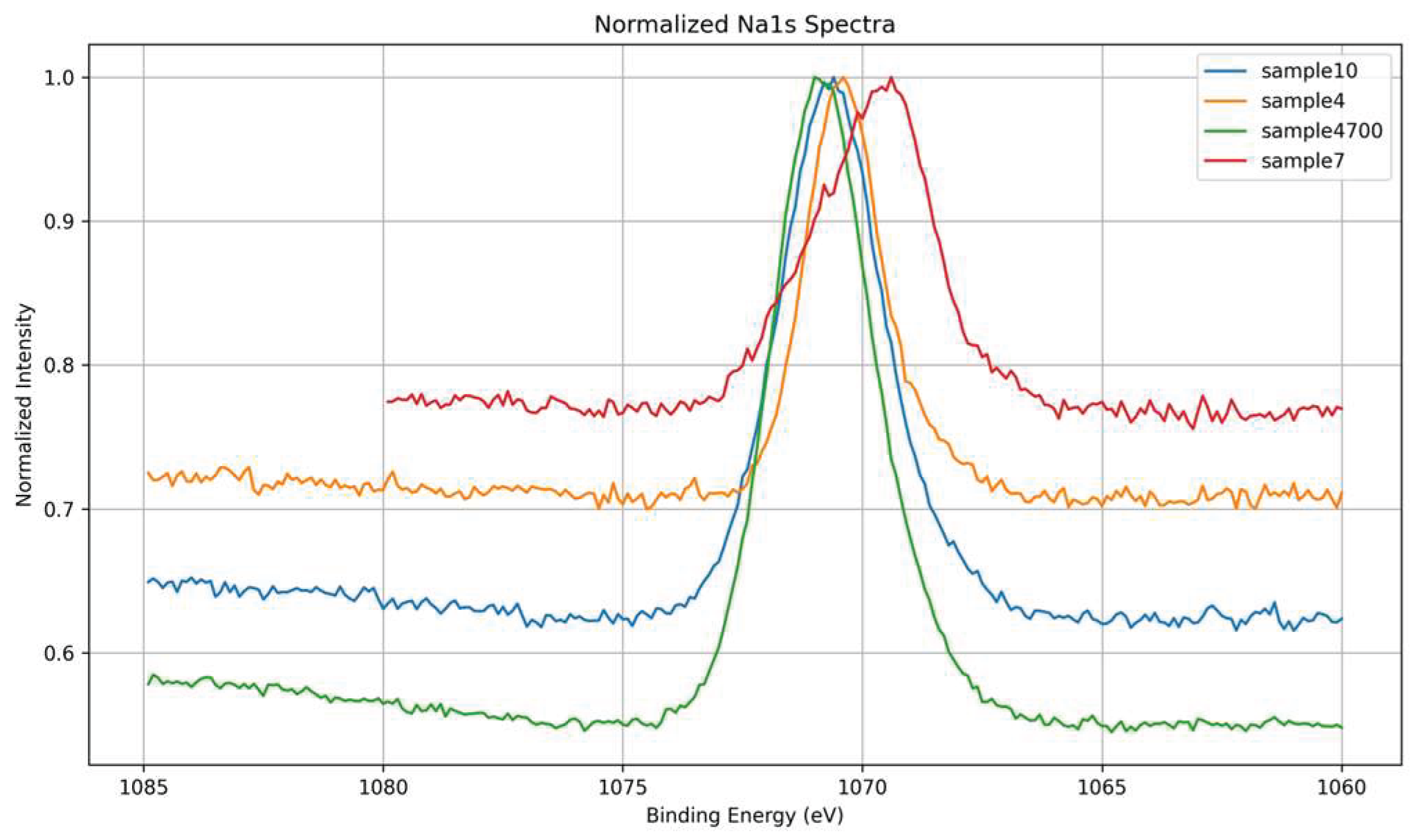

3.1.6. Na 1s Core-Level Analysis

The high-resolution Na 1s spectra provide insight into sodium incorporation, surface retention, and ionic dynamics in the glass matrices. As shown in

Figure 17, all samples display a Na 1s signal centered around ~1071.5 eV, characteristic of Na⁺ acting as a network modifier [

22].

The overlaid normalized spectra in

Figure 18 reveal significant differences in intensity and peak shape, reflecting both synthesis conditions and the ionic competition present during gel formation.

Sample 4700, synthesized with Água Prata and subjected to thermal treatment, exhibits the most intense Na 1s peak, indicating enhanced sodium retention near the surface. However, this peak is broader compared to Sample 4, suggesting increased local structural or electronic heterogeneity. This broadening likely results from thermal treatment inducing sodium redistribution into multiple coordination environments, possibly influenced by competing multivalent cations (e.g., Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺) present in the mineral-rich synthesis water. These factors lead to a wider distribution of Na–O bond characteristics, reflected in the broadened Na 1s peak.

Sample 4, synthesized under similar conditions but without thermal treatment, presents a narrower and less intense Na 1s peak. The narrower peak suggests a more uniform sodium environment, likely due to reduced ionic mobility and redistribution during gelation and drying. The lower peak intensity indicates less sodium retained at or near the surface, consistent with a less consolidated glass structure.

Sample 10, synthesized with Água Azeda, exhibits a moderately intense and asymmetric Na 1s signal. This suggests partial substitution or competitive interaction between Na⁺ and multivalent cations such as Mg²⁺ and possibly Fe³⁺ from the water. These ions may displace sodium from its typical modifier role or alter the surrounding oxygen coordination, disrupting charge balance and increasing variability in sodium’s local environment. The broader peak aligns with greater structural disorder and non-uniform electrostatic potential at Na⁺ sites, indicating increased heterogeneity.

Sample 7, synthesized with deionized water and no thermal treatment, exhibits the weakest and broadest Na 1s signal. Despite the chemical purity of the medium, the absence of thermal consolidation likely results in an open, under-condensed structure that allows Na⁺—a highly mobile species—to migrate away from the surface or reside in poorly coordinated, weakly bound environments. The reduced intensity and broad peak envelope reflect a low surface sodium density coupled with elevated electronic and structural disorder [

33].

These observations indicate that the Na 1s peak serves as a sensitive probe for sodium coordination and mobility in glass systems. Similar to findings by Barr (1990) in aluminosilicate glasses—where increasing the Si/Al ratio enhanced the ionicity of the Na–O bond and thereby increased Na⁺ exchangeability—it is plausible that comparable effects arise here due to multivalent cations introduced via mineral-rich waters. Ions such as Mg²⁺, Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺, or Fe³⁺ may act as competitive modifiers or local electrostatic disruptors, increasing Na–O bond polarization and enhancing sodium mobility or lowering binding energy. These effects are reflected in the observed peak asymmetry and broadening [

34].

Although some Na 1s peaks show asymmetry and broadening, no spectral deconvolution was performed. This choice is justified by the fact that Na⁺ typically exists in a single predominant chemical state in silicate glasses [

22] and does not produce multiple chemically distinct contributions within the Na 1s region. Instead, variations in peak shape are interpreted as indicators of local structural heterogeneity rather than distinct chemical states requiring deconvolution. Unlike elements such as Si or O—where distinct bonding environments can be resolved via peak fitting—the Na 1s signal is generally less informative when deconvoluted and may lead to misleading interpretations if over-analyzed [

35].

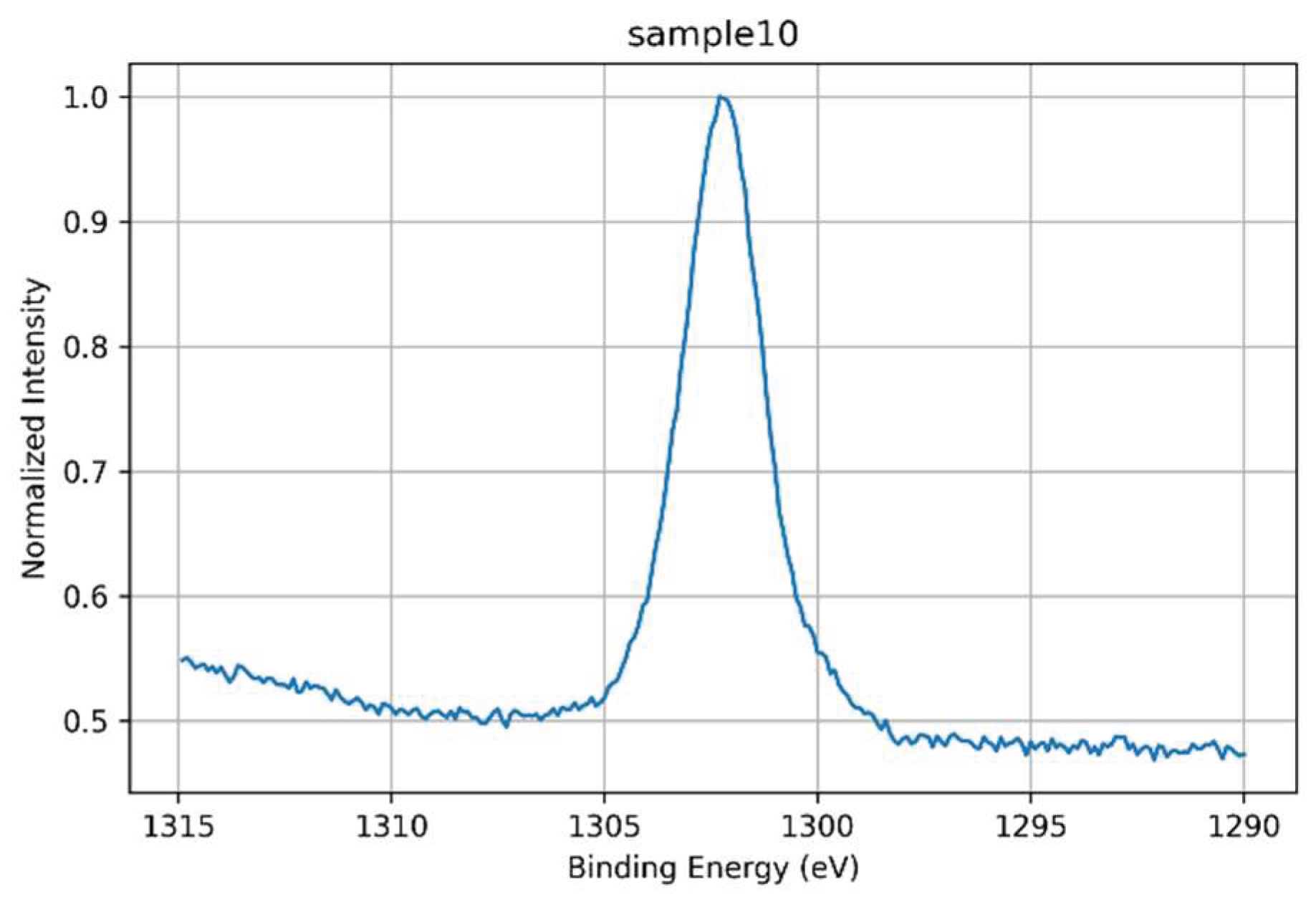

3.1.7. Mg 1s Core-Level Analysis

The high-resolution Mg 1s spectrum of Sample 10 is presented in

Figure 20. A single, well-defined peak centered at ~1302–1303 eV indicates that Mg²⁺ is present in a stable, fully oxidized state, incorporated uniformly into the glass matrix. The slight asymmetry towards lower binding energies may reflect minor variations in the local coordination environment, but no evidence of multiple chemical states or significant peak broadening was observed, and thus spectral deconvolution was not required. The spectral profile supports the interpretation that Mg²⁺ acts primarily as a network modifier or structural stabilizer within the glass. Indeed, it has been shown that Mg²⁺ can promote local network densification by occupying specific coordination environments and compensating for non-bridging oxygens, thereby enhancing the compactness and mechanical integrity of the silicate structure [

36]. In phosphate-free glass systems such as Sample 10, magnesium is expected to act primarily as a network modifier or structural stabilizer. Its presence may contribute to increased local packing density, altered cation ratios (e.g., Na⁺/Ca²⁺), and enhanced electrostatic balance within the silicate network. The localized occurrence of Mg in this composition reinforces its structural role in shaping the final properties of the glass.

3.1.8. Summary of Core-Level Trends

The high-resolution XPS analyses of the O 1s, Si 2p, P 2p, Ca 2p, and Na 1s core levels provide a comprehensive picture of the surface structure and local bonding environments across the synthesized bioactive glass compositions. Despite the amorphous nature of these materials, the electronic signatures reveal systematic chemical trends that reflect underlying physical principles governing atomic coordination and network formation.

One of the most striking observations lies in the evolution of the O 1s spectra, where the relative intensity of non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) decreases upon thermal treatment. This spectral narrowing and shift toward lower binding energies correspond to the condensation of hydroxyl-rich species into Si–O–Si bridges, as predicted by sol–gel polymerization kinetics. From a physical standpoint, this reflects a transition from higher energy, loosely bound surface states (with significant electron lone-pair contributions) toward more covalently bonded, lower-energy orbital overlaps. The resulting reduction in electronic disorder enhances the local dielectric environment and improves core-level resolution. In the Si 2p region, thermal consolidation and network modifier effects are equally evident. Shifts to lower binding energy and decreased FWHM values indicate a progressive enrichment in Q³ and Q⁴ units — a signature of increasing polymerization and three-dimensional network integrity. This reflects both the electrostatic stabilization of Si⁴⁺ centers by bridging oxygens and a reduction in final-state screening effects, as network compactness increases the average local electron density. The silicate network thus transitions from fragmented, NBO-rich chains to more interconnected units with greater structural coherence. The P 2p core-level signals show that phosphate species, though retained in the network, are highly sensitive to the presence of modifying cations. The deconvolution profiles suggest a dual population: regular tetrahedral PO₄³⁻ units and distorted phosphates influenced by interactions with cations such as Sr²⁺ and Zn²⁺. These interactions cause localized distortion and charge redistribution, leading to small chemical shifts in binding energy. From a quantum-mechanical perspective, this represents modulation of the local potential field around phosphorus centers, affecting the core-level relaxation energies.

In the Ca 2p spectra, both binding energy shifts and peak multiplicity are observed, which correlate directly with coordination diversity. The presence of Ca–O–P and Ca–O–Si environments, and in some cases surface-hydrated Ca species, reflects the sensitivity of calcium to local ionic competition and structural disorder. In untreated glasses, particularly those synthesized in deionized water, calcium remains loosely coordinated, forming clusters with phosphate due to electrostatic preference. In contrast, when trace elements are present in the synthesis medium, as with Água Prata, calcium is redistributed into the silicate network. These shifts are governed by differences in cation field strength and polarizability, which influence not only bond stability but also core-hole screening during photoemission, resulting in measurable variations in binding energy.

The Na 1s spectra further support the dynamic behavior of alkali modifiers. Sodium, with its low field strength and high mobility, exhibits consistent binding energies but variable intensity, likely due to partial leaching or exchange with divalent cations during gelation. This behavior aligns with its role as a charge compensator for non-bridging oxygens, which decrease upon thermal consolidation.

Altogether, these trends demonstrate that the local electronic structure of bioactive sol–gel glasses is not static but highly responsive to both the chemical complexity of the synthesis medium and post-synthetic thermal evolution. The observed shifts in core-level energies, changes in peak symmetry, and deconvolution patterns reflect a complex interplay of local coordination geometry, electronic relaxation dynamics, and ion-mediated structural reorganization. These effects are rooted in fundamental physical interactions, such as Coulombic attraction, orbital hybridization, and photoelectron screening, which govern the chemical state sensitivity of XPS.

This multi-level spectroscopic insight reveals that natural waters, far from being inert solvents, act as active structural agents that shape the glass network at the atomic scale, reinforcing the potential of environmentally integrated sol–gel routes for fine-tuning surface reactivity in bioactive glasses.

A condensed summary of the core-level observations and structural implications for selected samples is presented in

Table 6, integrating compositional and processing parameters with XPS-based interpretations.