1. Introduction

The Amazon River basin is the largest river system in the world and one of the most vital ecosystems on the planet. It supports an extraordinarily diverse range of flora and fauna and is critical in regulating the global climate. However, the region faces escalating environmental challenges, including water pollution and declining water quality resulting from urbanization, industrial activities, and deforestation. Moreover, according to data from WWF-Brazil and the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) [WWF-Brazil and ACTO, 2023], mercury contamination in Amazonian rivers has shown an alarming increase, reaching approximately 150 tons per year, posing a serious environmental threat. Illegal activities, particularly gold mining, are key contributors to this contamination, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive water quality monitoring and effective conservation strategies.

Numerous international initiatives have emerged in recent decades in response to global environmental crises. Among the most notable was the 2015 United Nations Assembly, where representatives from 193 countries established the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with targets set for 2015 to 2030. Among these goals, “Clean Water and Sanitation” is directly aligned with the objectives of this article [United Nations, 2023].

Despite the Amazon region’s critical role in maintaining global ecological balance, there is a noticeable lack of scientific literature focused on water quality monitoring in this area. This gap is particularly concerning considering the increasing anthropogenic pressures such as deforestation, agriculture, and illegal mining. A deeper understanding of water quality dynamics in the Amazon is essential for informed environmental management and the development of targeted conservation strategies. Since these river systems are essential for sustaining biodiversity and supporting local communities, advancing research efforts in water quality monitoring is paramount and ongoing.

Monitoring and managing water quality in such a complex and dynamic environment pose significant challenges. Currently, the predominant techniques used in the region rely on collecting water samples for later laboratory analysis. While effective, this method is costly and labor-intensive, limiting the frequency and scalability of monitoring activities.

To address this challenge, the main goal of this article is to review Internet of Things (IoT) system architectures capable of enabling real-time water quality monitoring while identifying system requirements compatible with the unique environmental and infrastructural conditions of the Amazon basin.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 outlines the research methodology used in this work.

Section 3 discusses system requirements for rainforest environments.

Section 4 focuses on data acquisition in the context of water monitoring.

Section 5 presents considerations related to connectivity and edge processing.

Section 6 analyzes the findings about the research questions. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the study and offers suggestions for future research directions.

2. Research Methodology

Water quality monitoring systems have become a significant research field in recent years. Systematic literature reviews (SLR) conducted by [Zulkifli et al., 2022] and [Velayudhan et al., 2022] explore these systems in depth. Their work used the search string (“water quality” OR “water monitoring”) AND (“IoT” OR “Internet of Things”), resulting in a total of 134 relevant papers, which serve as the foundation for this study.

To expand on their findings, we replicated the same search string using the Engineering Village database [Engineering Village, 2025], filtering results to include only papers published between 2022 and 2023. This extended search aimed to explore the design of water quality monitoring systems by addressing the following research questions:

- i).

What are the main physical parameters in water quality monitoring?

- ii).

Which IoT platforms are most commonly applied?

- iii).

How can appropriate connectivity be selected for remote sensor networks in rainforest environments?

- iv).

How is the collected data delivered to applications?

- v).

Are the proposed architectures compatible with the Amazon rainforest context?

Although the initial search returned several valuable studies on IoT-based water systems, none directly addressed the unique requirements of rainforest environments. Even Haider

et al. [2022], who studied a tropical lake, did not focus on such conditions. To fill this gap, we performed an additional search using the terms (“Amazon” OR “rainforest”) AND (“network” OR “system requirements”).

Section 3 reviews the system requirements for IoT implementations in the Amazon rainforest, organizing them into functional and non-functional categories.

3. System Requirements for Rainforest Environment

Designing an IoT system for water quality monitoring in the Amazon rainforest is challenging due to its unique and demanding conditions. Researchers must give careful attention to system requirements across the following areas:

- -

Environmental resilience: The rainforest’s unpredictable weather and limited resources demand robust solutions, such as weatherproof enclosures and corrosion-resistant materials [Naskar et al., 2025].

- -

Data acquisition: Sensor selection must align with the specific monitoring parameters. Researchers should use biocompatible and wildlife-friendly sensors to measure temperature, humidity, soil moisture, and biological activity, minimizing environmental impact [Cama et al., 2013].

- -

Power consumption: Effective power management involves innovative solutions such as solar panels and wind turbines, supported by energy harvesting technologies like thermoelectric systems for overcast days and hydrokinetic turbines [Matos et al., 2011].

- -

Connectivity: Low-power, long-range communication protocols like LoRa and Sigfox help overcome the connectivity challenges posed by dense vegetation, while satellite communication provides coverage for more remote areas [Moreira et al., 2025].

- -

Edge processing: Edge computing allows on-site data pre-processing and filtering, reducing bandwidth consumption and server load [Hasan and Idrees, 2024]. Data security requires secure transmission protocols and encryption to protect sensitive environmental information [Moreira et al., 2025].

- -

Maintainability and scalability: Remote monitoring and management capabilities are essential for performance checks, data quality assessments, and quick troubleshooting. Features like remote firmware updates and configuration changes reduce the need for physical access. A modular design supports easy expansion and adaptation, whether to meet evolving research needs or to address unforeseen environmental challenges [Gandolfi, 2023].

- -

Data analytics: Cloud-based platforms handle advanced processing, analysis, and visualization, enabling insights and expanding the applicability of the collected data [Naskar et al., 2025; Gupta and Sharma, 2023].

- -

Sustainability: Sustainability serves as a guiding principle. Energy-efficient hardware and software help minimize environmental impact, while responsible end-of-life strategies and recycled materials reinforce the system’s eco-friendly design [Furtado et al., 2022].

By thoroughly addressing these system requirements, developers can build robust and sustainable IoT systems that help uncover the rainforest’s complexities. These requirements are categorized into functional and non-functional types, as shown in

Table 1.

Functional requirements outline specific tasks and features, while non-functional ones define how the system should perform, focusing on usability, performance, security, and reliability. A deeper investigation into the first functional requirement may provide a strong starting point for future work, particularly in developing a proof-of-concept node device capable of implementing a water quality monitoring network in the Amazon River.

4. Data Acquisition

Focusing monitoring efforts on the waters adjacent to the Marauiá and Madeira Rivers allows for greater centralization. However, significant logistical challenges persist. The region’s dense forests and vast distances between areas with internet access pose substantial obstacles. Additionally, potential human interference must be considered, as these regions are also known for illegal mining practices, contributing to the abnormal increase in mercury levels in the water. Once our system detects and registers these mining sites, data collection points may attract unwanted attention from individuals involved in such illicit activities. This study analyzed mercury levels, temperature, turbidity, and pH. Below, we present the rationale behind each selected variable.

4.1. Mercury Levels

Monitoring mercury levels in water is essential for assessing water quality and safeguarding human health and aquatic ecosystems. Mercury is a highly dangerous environmental contaminant, particularly hazardous in regions where indigenous communities rely heavily on fishing as a primary food source. It can enter water systems through various pathways, including industrial activity, mining [WWF-Brazil and ACTO, 2023], agriculture, and even natural rock erosion [Silva et al., 2023].

Elevated mercury levels in water demand immediate corrective action to reduce human exposure and protect aquatic biodiversity. This urgent, ongoing issue requires proactive intervention rather than future planning. As highlighted by G1 News and a survey by Fiocruz [Nacional, 2020], the threat is already present. In December 2020, around 200 indigenous individuals were tested, all showing detectable levels of mercury in their hair samples. Consumption of mercury-contaminated fish poses serious health risks, including nervous system damage, neurological disorders, developmental delays in children, and organ damage [Silva et al., 2023]. Monitoring mercury concentrations is critical for protecting local communities and identifying fishing zones that may need restrictions or specific regulations. Furthermore, mercury is toxic to many aquatic organisms—including fish, invertebrates, and microorganisms—and can lead to population decline and biodiversity loss. As mercury accumulates through the aquatic food chain, top predators, such as large fish, become especially vulnerable.

Tracking mercury levels enables the identification of contaminated areas and informs the implementation of preventive measures. These include regulatory actions to reduce industrial emissions of mercury and educational campaigns to inform local populations about the dangers of consuming contaminated fish. Moreover, ongoing monitoring helps evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions and pinpoint regions needing further action. Therefore, monitoring this variable is fundamental to identifying, preventing, and mitigating the harmful impacts of mercury contamination. Our systematic analysis draws upon studies regularly conducted by institutions focused on environmental data collection and mercury monitoring, such as the National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA), WWF-Brazil, and the State University of Amazonas (UEA). Their findings show a significant rise in mercury contamination in mining-affected areas, with concentrations surpassing the thresholds set by environmental regulations [IBAMA, 2023; WWF-Brazil and ACTO, 2023; Amazonas Atual, 2023].

In response to these findings, continuous monitoring initiatives are underway, accompanied by awareness campaigns and support programs for local communities. The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) [IBAMA, 2023] and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) [WWF-Brazil and ACTO, 2023] play essential roles in mercury monitoring and enforcement. Additionally, research projects are actively developing and implementing remediation technologies to reduce mercury presence in aquatic environments [IBAMA, 2023; WWF-Brazil and ACTO, 2023].

It is important to highlight the gap in coordination between Brazil’s federal and state governments regarding mercury regulation. This lack of integration has resulted in the absence of a unified national pollutant monitoring system. One pioneering initiative that emerged to address this void was PROMER. This program aimed to establish a National and Permanent Network for Monitoring Mercury Levels in the Legal Amazon and the Pantanal. PROMER seeks to clarify the biogeochemical cycle of mercury in aquatic ecosystems within these biomes, consolidating the monitoring of a toxic metal in two regions of strategic national importance [PROMER/UNIDO, 2018].

4.2. Temperature Monitoring

Water temperature is a highly sensitive indicator, offering valuable insights into climatic and seasonal variations in the Amazon region. Among the variables considered in this study, it may serve as one of the most accurate indicators [Jáquez et al., 2023]. Monitoring changes in water temperature not only reveals local environmental conditions but also aids in assessing their effects on the hydrological characteristics of rivers, such as rainfall patterns, droughts or floods.

Water temperature is intrinsically linked to several aquatic ecosystem components and local biodiversity. Temperature fluctuations serve as clear indicators of ongoing climate change in the region. Consequently, water temperature directly influences evaporation and condensation processes, affecting rainfall distribution and water availability.

Significant temperature variations can trigger extreme weather events, such as prolonged droughts or intense flooding, severely impacting the livelihoods of riverine communities and the biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems.

One proposed method for sensor deployment involves attaching sensors to community vessels, leveraging the high frequency of boat traffic in the Amazon River region. This approach enables data collection from multiple river locations using a single sensor.

Changes in water temperature also have a direct impact on aquatic biodiversity. Elevated temperatures tend to reduce the concentration of dissolved oxygen in water [Jebaraj et al., 2022], creating less favourable conditions for the survival of aquatic organisms. These conditions affect fish, insects, and microorganisms, which play essential roles in maintaining the aquatic food web.

Furthermore, temperature shifts influence the solubility of substances in water, including minerals and nutrients. This directly affects the availability of nutrients to aquatic plants, ultimately influencing primary production and the broader food chain. Temperature variations also affect reproductive behaviour in aquatic species. Many species depend on specific temperature ranges to initiate reproductive cycles; therefore, such changes may disrupt reproductive timing and success, potentially affecting biodiversity and ecosystem dynamics.

Maintaining accurate records of river temperature in the Amazon is essential for evaluating ecosystem health and identifying changes driven by natural causes or human activities, such as deforestation. Continuous monitoring provides vital information for conserving aquatic biodiversity, sustainably managing water resources, and developing climate adaptation strategies. In summary, monitoring water temperature in Amazonian rivers is fundamental to understanding climate change and its implications for aquatic ecosystems. It is a critical tool for informed decision-making and implementing conservation measures to preserve the region’s sustainability and rich biodiversity.

To measure temperature levels, we propose using the SKU: DFR0198 sensor. This sensor supports integration with similar devices through a centralized command system and features a wide measurement range from -55°C to 125°C [Jáquez et al., 2023], accommodating the diverse environmental conditions of Amazonian rivers. It also offers high accuracy, maintaining ±0.5°C within the range of -10°C to +85°C. The sensor ensures consistent and optimal performance when operating with voltages between 3.0V and 5.5V. Its digital output minimizes signal degradation over long distances.

The sensor utilizes a 1-wire interface, requiring only one digital pin for communication. A 4.7K Ohm resistor is recommended for optimal performance between the power supply and the signal pin. A terminal sensor adapter is also advised to ensure a stable and secure connection. The sensor is housed in a stainless steel tube, measuring 6 mm in diameter and 35 mm in length.

4.3. Turbity Monitoring

The analysis of water turbidity goes beyond simply indicating water clarity or transparency [Jáquez et al., 2023]. Abnormal turbidity levels can signal various environmental issues and significantly impact aquatic ecosystems and human well-being. As a reliable indicator of water quality, elevated turbidity often reflects the presence of sediments, pollutants, and suspended particles. Accurately and consistently measuring turbidity provides valuable data for environmental agencies and regulatory bodies, enabling timely corrective actions to mitigate water pollution before it causes serious ecological and public health damage. Moreover, high turbidity levels reduce light penetration into water bodies, directly affecting photosynthesis and primary production. This process is fundamental for aquatic plants to generate oxygen and energy, supporting ecological balance.

Excessive turbidity can also harm aquatic life by disrupting species’ life cycles and decreasing food availability within the aquatic food chain. Turbidity compromises river navigability in regions with dense river networks, such as the Amazon. Elevated sediment concentrations make navigation hazardous, affecting transportation, access to remote communities, and the regional economy. Therefore, continuous turbidity monitoring ensures safe river navigation, connectivity, and reliable delivery of essential resources.

Additionally, water turbidity monitoring is vital for ensuring safe drinking water. Suspended particles can harbor pathogens and degrade water quality, impacting both taste and safety. Thus, turbidity surveillance plays a protective role in public health and helps ensure access to clean, safe water.

In summary, turbidity monitoring serves multiple purposes, from evaluating water quality and protecting biodiversity to ensuring navigational safety and safe water supply.

Investing in turbidity monitoring technologies and practices is essential for promoting sustainable water resource management and providing a healthier, more resilient future for communities and the environment.

We propose using the SEN0189 sensor [Rahu et al., 2022] to assess water clarity or turbidity resulting from suspended particles. This device emits light into the water and measures its scattering and absorption as it interacts with particles.

Turbidity is measured in Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU). In pure water (i.e., NTU < 0.5), the sensor should output approximately ”4.1 ± 0.3V” when operating between 10°C and 50°C [DFRobot, 2025].

Turbidity sensors are crucial for monitoring water quality, offering data on sediments, suspended solids, and pollutants. The SEN0189 sensor operates at 5 V DC, with a maximum current draw of 40 mA, a response time of less than 500 ms, and a minimum resistance of 100 mΩ.

It features two output methods: analogue (0–4.5 V) and digital, with an adjustable high/low threshold via a potentiometer.

Its operational temperature range is 5°C to 90°C, and its storage temperature range is –10°C to 90°C.

Interface description:

4.4. pH Monitoring

Measuring pH presents unique challenges due to its neutral reference value of 7 [Jebaraj et al., 2022]. However, monitoring pH levels in the waters of the Amazon basin provides crucial insights into water acidity or alkalinity, reflecting various environmental and ecological dynamics. Variations in pH can stem from human activities, such as the discharge of industrial and agricultural waste and natural processes like the decomposition of organic matter. Continuous pH monitoring enables early detection of water quality changes, vital for preserving aquatic ecosystems.

The pH level directly influences the survival and reproductive capacity of aquatic organisms. Many species thrive within narrow pH ranges; abrupt deviations can compromise their health and disrupt life cycles. Acidification, for instance, can reduce biodiversity and destabilize the river ecosystem’s dynamics.

Additionally, pH affects the solubility of minerals and nutrients in water, impacting their availability for aquatic flora. These effects ripple through the food chain, influencing primary production and the sustainability of resources that support riverside communities. Monitoring this parameter enables the identification of environmental changes caused by either natural events or human interference. Consistent pH monitoring also supports the detection of vulnerable areas and is fundamental for guiding conservation measures and environmental policies that preserve river integrity and water resource quality.

Hence, pH measurement in Amazonian river systems is critical for safeguarding biodiversity and promoting sustainable use of natural resources, supporting environmental health and long-term ecological balance.

To carry out pH assessments, the SEN0161 analogue pH sensor is a viable solution [Bogdan et al., 2023]. This sensor measures ion concentration in water with high accuracy. Depending on the technology used—glass electrodes or solid-state mechanisms—pH sensors offer precise measurements crucial in water quality analysis. Since pH influences biological processes, chemical reactions, and ecosystem balance, sensors are widely used in drinking water monitoring, aquaculture, wastewater treatment, and industrial operations where maintaining specific pH levels is essential [Rahu et al., 2022].

The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14: values below 7 indicate acidity, values above 7 indicate alkalinity, and a value of 7 represents a neutral solution under standard thermodynamic conditions.

The SEN0161 sensor operates at 5.00 V and supports a wide pH measurement range from 0 to 14. It functions efficiently within temperatures from 0°C to 60°C. Its accuracy is ±0.1 pH at 25°C, with a fast response time of one minute or less.

This sensor offers reliable performance and flexible integration into various systems and is equipped with a BNC connector for stable signal transmission and a 3-foot PH2.0 interface cable. These features make it a dependable and precise option for multiple applications, ensuring consistent and effective water quality assessments across diverse conditions.

These characteristics make the pH sensor a reliable and accurate choice for various applications, ensuring consistent and efficient results in diverse conditions.

5. Connectivity & Edge Processing

One of the core features of Internet of Things (IoT) systems is their ability to establish interconnectivity in the field. The appropriate communication technology must be selected based on the specific environmental conditions in which the system operates. A systematic literature review by Camargo et al. [2023] on water monitoring systems revealed that 56% of the analyzed studies employed Wi-Fi, particularly in confined environments or over short distances. This was followed by mobile networks (GPRS, GSM, 3G, and 4G), used in 17.6% of the cases, and Low Power Wide Area Networks (LPWAN) technologies such as LoRa and NB-IoT, adopted in 16.1% of the works for long-distance applications.

Regarding node platforms, Arduino and its combinations (e.g., Arduino with ESP or Raspberry Pi) are among the most widely used due to their compatibility with sensor communication protocols like I2C and SPI, as well as the ready availability of modular shields that expand their capabilities by adding connectivity features such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, LoRa, and Zigbee. Interestingly, exclusive use of ESP-based boards was reported in only 10% of the studies.

The Amazon rainforest presents a challenging scenario for wireless communication technologies due to its dense vegetation, high humidity, and frequent rainfall. Wireless networks operating at high frequencies, such as Wi-Fi, often require numerous nodes and tend to cover only limited areas due to significant signal attenuation and degradation [Haider et al., 2022; Bogdan et al., 2023].

The following sections discuss recent works that explore the application of various communication technologies and node platforms adapted to environmental conditions for effective water parameter monitoring.

5.1. Urban Systems

Some water monitoring and management systems are built for areas with internet coverage. They use Wi-Fi as an internet access point or cellular connectivity, such as Bluetooth, to integrate their IoT devices with a remote database and develop their applications to access the stored data. One of these systems is a water management system for palm trees [Canlas et al., 2022], located in a country in the Middle East with a dry environment, which requires precise irrigation management. This work presents a NodeMCU platform with a Wi-Fi module with sensors collecting information from humidity, temperature and soil moisture levels and sending it to an Apache web server in the cloud. An Android mobile application developed in PHP can access data from the Apache database using MySQL and provide a dashboard to monitor the system and control a relay to activate sprinklers.

Another work used the cellular Bluetooth communicating with Arduino to bypass the absence of internet connection [Bogdan et al., 2023]. This water monitoring system collects data from pH, dissolved solids, temperature and turbidity sensors using an Arduino board platform to process and send to an Android cellphone application. After the system admin collects data from Arduino, they can send it to a remote database when they can access the internet. A user application provides real-time access to data in the database through a dashboard. These systems assume an urbanised environment or near an access point to the Internet, and they are easily integrated with many frameworks for design, development, validation, and verification. Nevertheless, they do not fit well for a network in the rainforest environment, where cellular coverage and Internet access points, wired or not, are out of question. Yet, it is interesting to know how application layers from these systems work and what kind of processing they are doing with the data collected.

5.2. WiLD Networks

In 2007, researchers from Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú and Spanish-America Health Link started a Wi-Fi over Long Distance (WiLD) network project to support telemedicine programs [Rey-Moreno et al., 2011]. In 2013, Espinoza et al. [2013] proposed a VoIP communication service using this infrastructure. This project infrastructure was placed on the margins of the Napo River, Peru, in the middle of the Amazon rainforest. At that time, it counted 17 repeat stations along 445 km from the capital of the Loreto state to the border with Ecuador.

This network consists of two radio links. The Backbone radio links used towers with a line of sight, ranging from 45 m to 90 m above the ground, to provide communication from 25 km to 50 km between stations. The Access radio links allowed end-user stations to access the network within a 2 km radius. Each backbone radio link is equipped with a wireless router, an embedded x86 system, a 400 MHz CPU, 128 MB RAM, and a high-power IEEE 802.11g wireless card with 26 dBm and 24 dBi directive antennas. A custom Linux based system runs on this to execute the wireless card drivers and the decentralised VoIP server Asterisk.

A more recent work by Mickelson et al. [2017] discusses the downside of using Wi-Fi due to the line-of-sight requirement against the up to 40 m forest canopy in the Amazon forest. A good alternative would be to use the television white space (TVWS). This signal takes advantage of the remaining television broadcast frequency and can penetrate dense materials, which is especially useful in dense forests. However, it has a significantly smaller throughput when compared with WiLD; while TVWS provide speeds up to 25 Mbps, WiLD could reach up to 200 Mbps. TVWS has a significant amount of noise due to its long use in the past, and equipment is not easy to acquire because of the small number of distributors worldwide.

Despite Peru’s WiLD Networks not being designed for remote sensors, it brings important elements to implement a network with cities located in rainforests. Communities along the Napo River did not have physical communication trunks connecting the villages, depending on government subsidised satellite phones in main villages. The decentralised topology was a nice approach to prevent all nodes from disconnecting if the signal fades or even goes down. Also, choose higher frequencies as Wi-Fi increased efforts with infrastructure building towers and using directive antennas to mitigate attenuation by leaves and rain over long distances. The usage of a Linux-based system was justified by the VoIP service provided. All this shall stand to design a network for water quality monitoring on the Amazon River in Brazil.

5.3. Heterogeneous Networks

Sometimes, using just one type of connectivity is not enough to overcome environmental barriers. In those cases, a heterogeneous network would be applied. Heterogeneous networks combine different connectivity systems to exploit the best features from each one.

Haider et al. [2022] proposes an LPWAN IoT water quality monitoring system to monitor Chini Lake in Malaysia, which has a harsh tropical environment. Their system consists of gathering data from sensors and distributing it over the lake surface using a Smart Utility Network (SUN) wireless technology based on IEEE 802.15.4g standard physical layer, which operates in 920 MHz frequency, is sustainable to distances up to 1 km, and has a low power consumption.

Also, SUN is compatible with either mesh or tree topology. Each sensor is connected to a SUN device, constituting the network nodes.

Subsequently, measured data is relayed in a multihop manner from each node to a personal area network (PAN) coordinator with a LoRa interface that acts as a SUN/LoRa gateway from a heterogeneous network. LoRa operates with star topology, which requires a direct connection between the gateway and the end nodes, which is not ideal for nodes. However, it can transmit over several kilometres in an open area compared to the SUN. Therefore, LoRa was selected as the wireless communication between the PAN coordinator and the LoRa gateway in an air balloon with a LoRa/Wi-Fi interface.

The balloon is placed near the central station and lifted above 50 m. Wi-Fi devices have a larger bandwidth than previous communication technologies. Still, they have a short area coverage, even in an open area, so a highly directional antenna may be used to relay data to the central station.

Heterogeneous networks fit very well in the rainforest environment by combining very distributed wireless technology with strong resistance to obstacles and lower throughput over long distances, such as SUN and LoRa, with gateways with higher bandwidth short-distance Wi-Fi.

6. Data Analytics

The application layer is fundamental in managing, analyzing, and visualizing data within IoT-based monitoring systems. A comprehensive literature review by Patel et al. [2023] highlights various strategies adopted for this layer in IoT and industrial contexts. These include diverse data storage platforms, processing algorithms, and visualization models. This heterogeneity demonstrates the breadth of state-of-the-art solutions with distinct advantages and constraints.

Given the logistical challenges of conducting in situ data collection in the Amazon basin, we propose a remote sensing approach for water quality monitoring. Remote sensing offers a range of methodologies that vary depending on the type of water body and the specific parameters to be monitored.

While most water quality parameters can be assessed using standard procedures, as noted in [Abdulwahid, 2020], these methods often increase project costs and complexity due to the high variability of aquatic environments. Therefore, this study focuses on surface water monitoring, targeting key parameters such as mercury concentration, temperature, turbidity, and pH.

To evaluate the feasibility and reliability of different prediction approaches, we compiled a table (

Table 2) summarizing key studies in the field. This includes the algorithms applied, water quality parameters considered, and evaluation metrics used across diverse applications.

Water quality prediction has been approached through various methodologies in the literature. Bhardwaj et al. [2022] examined turbidity forecasting using Random Forest, XGBoost, Naive Bayes, and Passive-Aggressive algorithms.

Their model inputs included turbidity, pH, temperature, and water flow, evaluated using precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy metrics.

In another study, Kouadri et al. [2021] conducted a comparative analysis of eight machine learning algorithms for Water Quality Index (WQI) prediction, using a dataset characterized

by irregularities. The input features encompassed a broad range of physical and chemical indicators, including TDS, CE (electrical conductivity), T°C (temperature), pH,

Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, and various anions and pollution markers. The models were evaluated using R, MAE, RMSE, RAE, and RRSE.

Shah et al. [2021] explored the prediction of total dissolved solids (TDS) and electrical conductivity (EC) using GEP, ANN, MLR, and MNLR models. Their evaluation employed metrics such as NSE, R2, MAE, RMSE, and k-fold cross-validation to assess model robustness.

Focusing on long-term forecasting, Peng [2022] introduced a Transformer-based model named TLT, targeting parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, NH+4 -N, and COD.

Evaluation metrics included MSE and MAE, offering insights into the model’s predictive reliability.

Uddin et al. [2022] proposed an enhanced framework for coastal water quality prediction, integrating XGBoost, linear interpolation, and various aggregation techniques. Their models analyzed parameters such as salinity, temperature, pH, transparency, dissolved oxygen, BOD, nitrogen, phosphorus, and chlorophyll-a, using R2 and RMSE to assess performance.

In a follow-up study, Uddin et al. [2022] focused on classifying water quality into categorical classes using KNN, XGBoost, SVM, and Naive Bayes. This model relied on ten indicators: temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, BOD, transparency, chlorophyll-a, and DIN. Evaluation criteria included accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score.

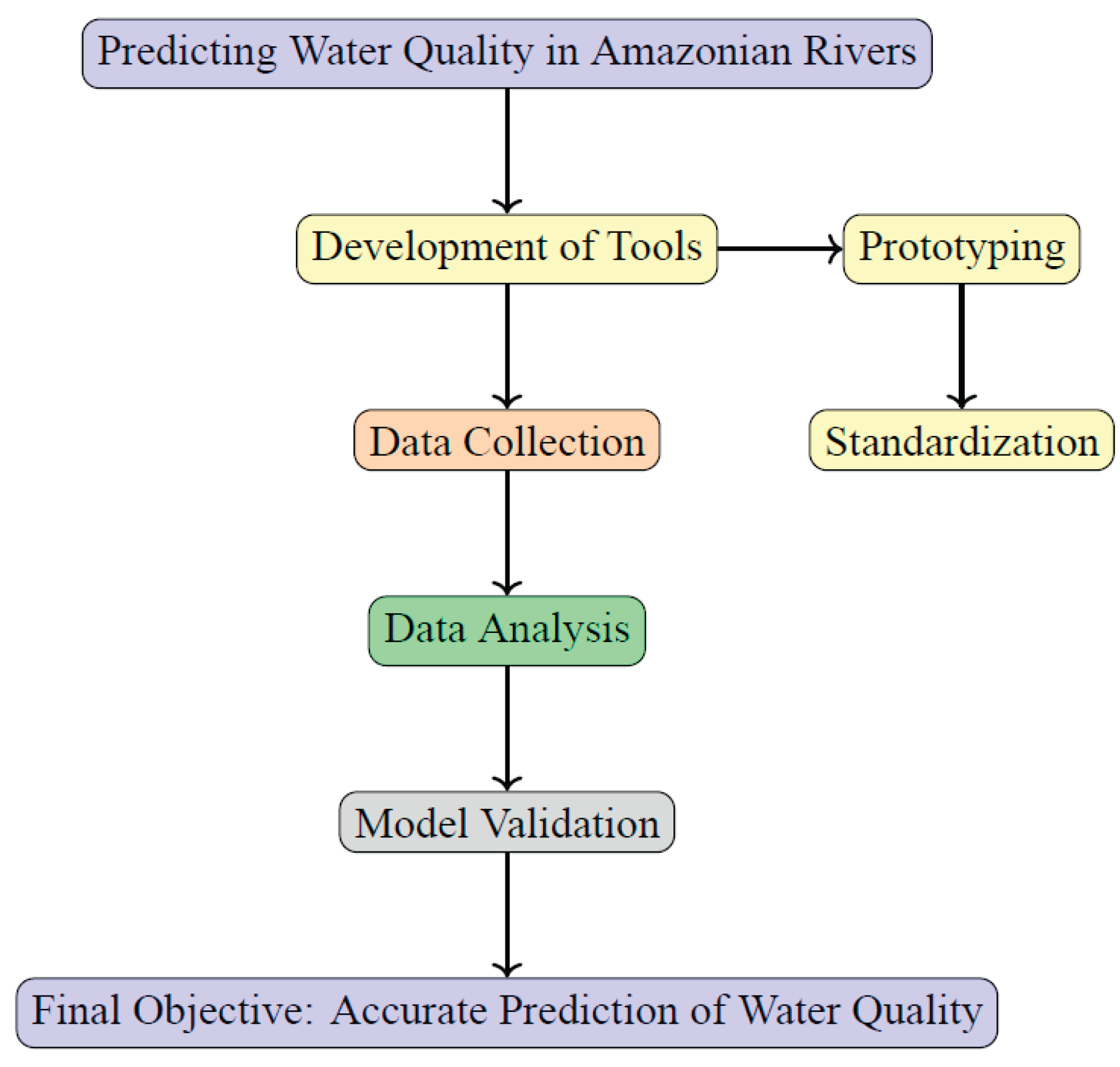

In conclusion, although machine learning applications for water quality prediction have shown considerable potential, the field remains under active development. The next step involves designing and prototyping a specialized tool for Amazonian river monitoring. This prototype will standardize data collection and sampling procedures, enabling evaluation and comparison of prediction techniques using established performance metrics. Ultimately, the goal is to identify and validate the most effective and scalable model for accurate water quality forecasting across the diverse and dynamic ecosystems of the Amazon.

To achieve this, it is necessary to follow the workflow presented in the

Figure 1 below to obtain a specialized tool for monitoring the Amazonian rivers.

7. Conclusion

This research presents a comprehensive set of functional requirements for an IoT-based system tailored to water quality monitoring in the Amazon. These requirements address the region’s unique environmental and infrastructural challenges, tailored for effective water quality monitoring in the intricate network of Amazon’s rivers. The unique environmental challenges posed by the Amazon Basin necessitate a sophisticated and resilient system that can provide real-time data, facilitate informed decision-making, and contribute to the sustainable management of this vital ecosystem.

The amalgamation of sensor technologies, data analytics, and communication protocols within requirements addresses the specific demands of the Amazon rainforest. By deploying a network of IoT devices strategically positioned across the basin, we can harness the power of real-time data acquisition to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamic water quality parameters. The envisioned system monitors temperature, turbidity, pH and mercury levels, enabling the detection of anomalies in water flow patterns. This holistic approach ensures that an IoT architecture can adapt to the evolving environmental landscape of the Amazon Basin.

Furthermore, integrating cloud computing and machine learning algorithms enhances the system’s ability to analyze vast datasets, identify patterns, and predict potential water quality issues. This predictive capability is essential for early intervention and timely responses to prevent or mitigate the impact of pollution events, safeguarding both human populations and the diverse aquatic ecosystems that rely on the Amazon’s rivers.

While IoT systems offer a robust framework for water quality monitoring, we acknowledge the importance of ongoing collaboration with local communities, governmental agencies, and environmental organizations. This collaborative effort is crucial for the proposed system’s successful implementation and long-term sustainability.

In conclusion, an IoT System Architecture for Water Quality Monitoring in the Amazon rainforest represents a significant step toward balancing human activities and preserving one of the world’s most vital ecosystems. Through continuous refinement, adaptation, and collaboration, we envision this architecture contributing to a holistic approach to water management that ensures the long-term health and resilience of the Amazon Basin. Thus, the next steps we intend to take are to design and validate an effective and scalable model for predicting water quality in Amazonian ecosystems.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in every stage of the work and contributed equally to its completion.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES-PROEX) – Finance Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data and materials are available and can be provided upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Professor Dr.-Eng. Edjair Mota, from the Postgraduate Program in Computer Science (PPGI) and the IoT Laboratory for Sustainability at the Federal University of Amazonas, for his invaluable guidance and contributions throughout the development of this work. We also extend our thanks to the Eldorado Research Institute for providing essential support and infrastructure, which were crucial to the successful completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abdulwahid, A. H. (2020). Iot based water quality monitoring system for rural areas. In 2020 9th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Application (ICRERA). [CrossRef]

- Amazonas Atual (2023). Uea pesquisa identifica níveis altos de mercúrio em peixes do rio madeira. Amazonas Atual.

- Bhardwaj, A., Dagar, V., Khan, M. O., Aggarwal, A., Alvarado, R., Kumar, M., and Irfan, M. (2022). Smart iot and machine learning-based framework for water quality assessment and device component monitoring. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R., Paliuc, C., M., C.-V., Nimara, S., and Barmayoun, D. (2023). Low-cost internet-of-things water-quality monitoring system for rural areas. Sensors, page 3919. Retrieved January 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cama, A., Montoya, F. G., Gómez, J., De La Cruz, J. L., and Manzano-Agugliaro, F. (2013). Integration of communication technologies in sensor networks to monitor the amazon environment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59:32–42. [CrossRef]

- Camargo, E. T. d., Spanhol, F. A., Slongo, J. S., Silva, M. V. R. d., Pazinato, J., Lobo, A. V. d. L., Coutinho, F. R., Pfrimer, F. W. D., Lindino, C. A., Oyamada, M., and Martins, L. D. (2023). Low-cost water quality sensors for iot: A systematic review. Sensors. Retrieved 30 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Canlas, F. Q., Falahi, M. A., and Nair, S. (2022). Iot based date palm water management system using case-based reasoning and linear regression for trend analysis. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 13(2):549–555.

- DFRobot (2025). Wiki dfrobot, n.d. web. Accessed: 2025-03-13.

-

Engineering Village Engineering village, n.d. web, 2025; Accessed. Engineering Village (2025). Engineering village, n.d. web. Accessed: 2025-03-13.

- Espinoza, D., Mickelson, A., Leventhal, J., Ritter, C., Quispe, R., and Liñan, L. (2013). A voip enabled cooperative network for agricultural commerce in amazon peru. 2013 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), pages 343–348. [CrossRef]

- Furtado, W. V., Júnior, O. A. V., de Oliveira Veras, A. A., de Sá, P. H. C. G., and and, A. M. A. (2022). Low-cost automation for artificial drying of cocoa beans: A case study in the amazon. Drying Technology, 40(1):42–49. [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, S. (2023). Off-grid energy system optimization for a remote community in the brazilian amazon rainforest. Accessed: 2025-04-28.

- Gupta, U. and Sharma, R. (2023). A study of cloud-based solution for data analytics. In Sharma, R., Jeon, G., and Zhang, Y., editors, Data Analytics for Internet of Things Infrastructure, Internet of Things. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Haider, A. H., Nordin, R., Singh, M. J., Haniz, A., Ishizu, K., Matsumura, T., Kojima, F., and Ramli, N. (2022). Low-altitude-platform-based airborne iot network (lap-ain) for water quality monitoring in harsh tropical environment. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B. T. and Idrees, A. K. (2024). Edge Computing for IoT, pages 1–20. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham. [CrossRef]

- IBAMA (2023). Ibama lança projeto rede de monitoramento ambiental no território indígena yanomami e alto amazonas.

- Jebaraj, B. S., Sankaran, V., and Sivasankaran, S. (2022). Online investigation for irrigation water quality parameters of gummidipoondi lake, thiruvallur, tamil nadu, india. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13201-021-01511-4. Retrieved November 2023.

- Jáquez, B., Daniel, A., Herrera, A., T., M., Celestino, M., Elizabeth, A., Ramírez, N., Efraín, and Martínez Cruz, D. A. (2023). Extension of lora coverage and integration of an unsupervised anomaly detection algorithm in an iot water quality monitoring system. mdpi. Retrieved November 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kouadri, S., Elbeltagi, A., and Islam, A. e. a. (2021). Performance of machine learning methods in predicting water quality index based on irregular data set: application on illizi region (algerian southeast). Appl Water Sci. [CrossRef]

- Matos, F. B., Camacho, J. R., Rodrigues, P., and Guimarães, S. C. (2011). A research on the use of energy resources in the amazon. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(6):3196–3206. [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, A., Kenyon, R. W., Miller, B., Fiehn, H. U. B., Hinkle, M., Costa, S., Bollen, N., and Dizon, C. (2017). University of colorado at boulder wildnet testbed. https:// ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8239268. Retrieved December 2017.

- Moreira, D., Santos, G., Yanai, A. E., Souza, P. B. d., Melo, P.V. F. d., and Mota, E. (2025). Lorabb: An algorithm for pa rameter selection in lora-based communication for the amazon rainforest. Sensors, 25(4).

- Nacional, J. (2020). Pesquisa da fiocruz revela contaminação por mercúrio em terra indígena do pará. https://g1.globo.com/jornalnacional/noticia/2020/12/07/pesquisa-da-fiocruz-revelacontaminacao-por-mercurio-em-terra-indigena-dopara.ghtml. Retrieved November 2023.

- Naskar, J., Jha, A. K., Singh, T. N., and Aeron, S. (2025). Climate change and soil resilience: A critical appraisal on innovative techniques for sustainable ground improvement and ecosystem protection. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste, 29(4). [CrossRef]

- Patel, A., Kethavath, A., N.L.Kushwaha, Naorem, A., Jagadale, M., K.R., S., and P.S., R. (2023). Review of artificial intelligence and internet of things technologies in land and water management research during 1991–2021: A bibliometric analysis. ScienceDirect.

- Peng, L. e. a. (2022). Tlt: Recurrent fine-tuning transfer learning for water quality long-term prediction. Water Research. [CrossRef]

- PROMER/UNIDO, P. (2018). Mercúrio na Bacia do Rio Tapajós: Diagnóstico da Contaminação e Propostas de Ações de Remediação. CETEM.

- Rahu, M. A., Chandio, A. F., Aurangzeb, K., Karim, S., Alhussein, M., and Anwar, M. S. (2022). Toward design of internet of things and machine learning-enabled frameworks for analysis and prediction of water quality. IEEE Access. Retrieved 14 September 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rey-Moreno, C., Bebea-Gonzalez, I., Foche-Perez, I., Quispe-Tacas, R., Liñán Benitez, L., and Simo-Reigadas, J. (2011). A telemedicine wifi network optimized for long distances in the amazonian jungle of peru. In Proceedings of the 3rd Extreme Conference on Communication: The Amazon Expedition, ExtremeCom ’11, New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M. I., Javed, M. F., and Abunama, T. (2021). Proposed formulation of surface water quality and modelling using gene expression, machine learning, and regression techniques. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28:13202–13220. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M. C. d., Oliveira, R. A. A. d., Vasconcellos, A. C. S. d., Rebouças, B. H., Pinto, B. D., Lima, M. d. O., Jesus, I. M. d., Machado, D. E., Hacon, S. S., Basta, P. C., and Perini, J. A. (2023). Chronic mercury exposure and gstp1 polymorphism in munduruku indigenous from brazilian amazon. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Retrieved November 2023. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. G., Nash, S., Rahman, A., and Olbert, A. I.(2022). A comprehensive method for improvement of water quality index (wqi) models for coastal water quality assessment. Science of The Total Environment. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. G., Nash, S., Rahman, A., and Olbert, A. I. (2023). Performance analysis of the water quality index model for predicting water state using machine learning techniques. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 169:808–828. Retrieved January 2023. [CrossRef]

- United Nations (2023). Sustainable development goals. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

- Velayudhan, N. K., Pradeep, P., Rao, S. N., Ramesh, M. V., and Devidas, A. R. (2022). Iot-enabled water distribution systems—a comparative technological review. IEEE Access. Retrieved September 2022. [CrossRef]

-

WWF-Brazil and ACTO (2023). Amazon has more than 4,000 illegal mining sites, shows acto study with wwf-brazil, November 2023; WWF-Brazil and ACTO (2023). Amazon has more than 4,000 illegal mining sites, shows acto study with wwf-brazil. Retrieved November 2023.

- Zulkifli, C. Z., Garfan, S., Talal, M., Alamoodi, A., Alamleh, A., Ahmaro, I. Y. Y., Sulaiman, S., Ibrahim, A. B., Zaidan, B. B., Ismail, A. R., Albahri, O. S., Albahri, A. S., Soon, C. F., Harun, N. H., and Chiang, H. H. (2022). Iot-based water monitoring systems: A systematic review. mdpi. Retrieved November 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).