Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

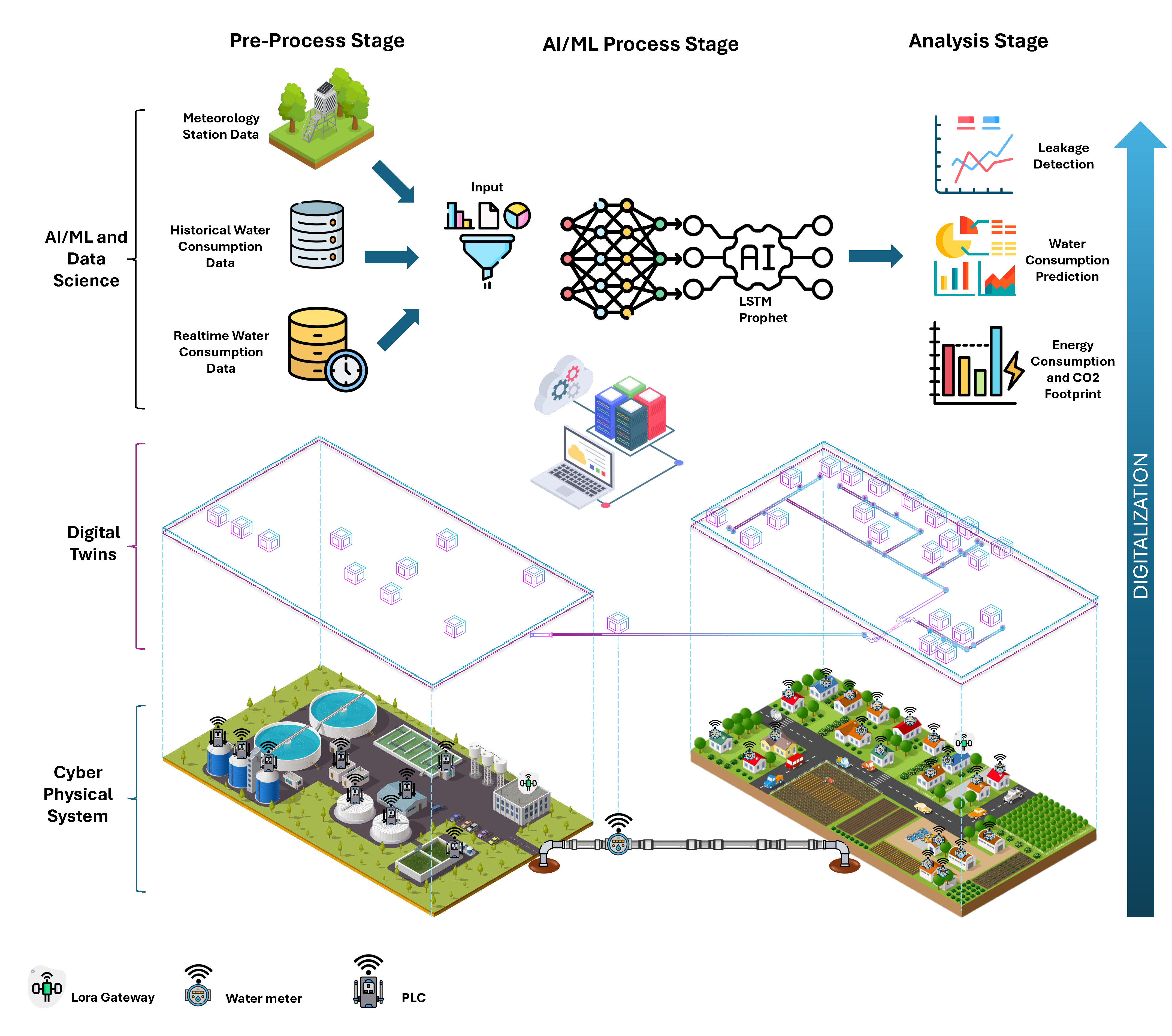

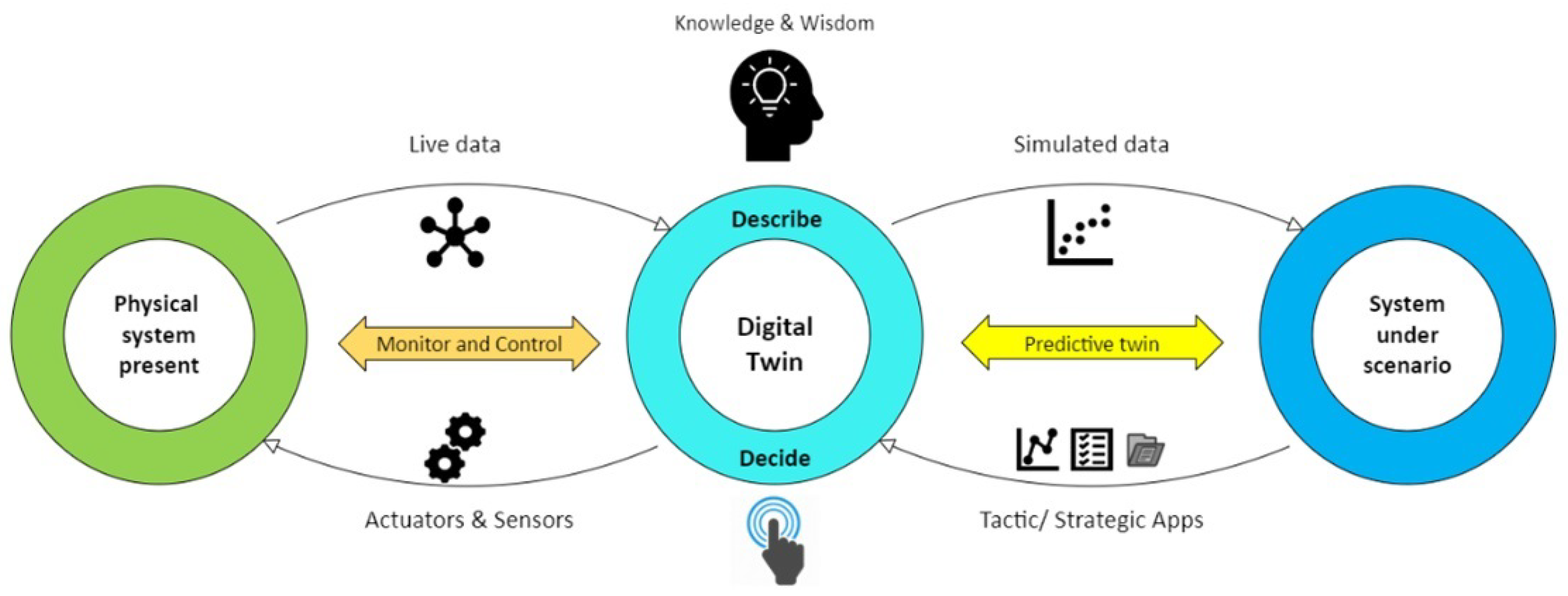

Digital Twins have emerged as a disruptive technology with great potential; they can enhance WDS by offering real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and optimization capabilities. This paper describes the development of a state-of-the-art DT platform for WDS, introducing advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things, Artificial Intelligence, and Machine Learning models. This paper provides insight into the architecture of the proposed platform-CAUCCES-that, informed by both historical and meteorological data, effectively deploys AI/ML models like LSTM networks, Prophet, LightGBM, and XGBoost in trying to predict water consumption patterns. Furthermore, we delve into how optimization in the maintenance of WDS can be achieved by formulating a Constraint Programming problem for scheduling, hence minimizing the operational cost efficiently with reduced environmental impacts. It also focuses on cybersecurity and protection to ensure the integrity and reliability of the DT platform. In this view, the system will contribute to improvements in decision-making capabilities, operational efficiency, and system reliability, with reassurance being drawn from the important role it can play toward sustainable management of water resources.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Objective and Main Contributions of the Paper

- The paper proposes an innovative platform based on DTs applied to a WDS, which would be transferred/tested in an SME from the sector in a rural environment. Even if the platform is focused on the water sector and WDS, it will easily be replicable for other sectors or other commercial interests.

- TIt is composed of the infrastructures of AI and ML and IoT for the realization of a digital transformation of traditional business models into digital business models. This inclusion in DT, together with IoT devices that allow the acquisition of data used in the predictions, would be of huge interest due to the possible application in similar contexts for prediction purposes.

- The platform integrates with advanced Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning models in water consumption prediction, hence providing more accurate demand forecasting and best resource management. Such predictive capability would help to achieve better decision-making in a water distribution system.

- It allows for maintenance scheduling, operator management of water distribution networks, realizes Digital Twins, and CP-based scheduling for optimization of maintenance activities. This ensures that operational efficiency is optimized, the occurrence of downtime is reduced, and service quality is improved through reliable management of the water distribution system.

- In fact, the cybersecurity threats that, as a consequence of the paradigm shift implied by the use of DT models connected to IoT devices, have been studied and considered. Another contribution of the paper deals with identifying the cybersecurity strategies that are implemented in accordance with the norm compliance ISO 27001. The implemented security strategies will doubtless be of great interest in similar projects.

- It has been tested in a real practical environment what was foreseen with the platform, functionalities, and possibilities that it provides. The proposed DT model, the use of an AI tool, and IoT device identification- including the identification of cybersecurity strategies easily replicable in similar settings and projects, constitute one of the basic contributions of this work.

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| AEMET | Agencia Estatal de Meteorología |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMI | Advanced Metering Infrastructure |

| AMR | Automated Meter Reading |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CADF | Combined Anomaly Detection Framework |

| CAUCCES | Control de Agua Urbana, Cantidad y Calidad Excelentes y Sostenibles |

| CP | Constraint Programming |

| CPS | Cyber-Physical Systems |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DMA | District Metered Area |

| DSS | Decision Support System |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| DWSs | Digital Water Services |

| ERD | Energy Recovery Device |

| EUI | Extended Unique Identifier |

| FDT | Functional Design Technology |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| HIP | Hydrologic Information Portal |

| HMI | Human-Machine Interface |

| HPP | High Pressure Pump |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LoRa | Long Range |

| LOS | Levels of Service |

| LSTM | Long-Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| PAT | Pumps as Turbines |

| PCC | Pearson Correlation Coefficients |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| PRV | Pressure Reduction Valves |

| QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| SSL | Secure Sockets Layer |

| SWaT | Secure Water Treatment |

| SWG | Smart Water Grid |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| VPN | Virtual Private Network |

| WDN | Water Distribution Network |

| WDS | Water Distribution System |

| WRRF | Water Resource Recovery Facility |

1.2. Article Structure

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Digital Transforming

- Real-time monitoring: Digital transformation will enhance real-time monitoring of the WDS; this will help in the early detection and timely response in case of system failure and leaks. For example, sensors that detect a leak in the system and send real-time alerts to maintenance personnel who can act immediately and reduce water wastage [18].

- Predictive maintenance: The process of digital transformation facilitates predictive maintenance, which serves to avert system failures and diminish maintenance expenses. For instance, machine learning algorithms can be developed using system data to anticipate maintenance requirements, thereby enabling maintenance personnel to organize repairs prior to the occurrence of system malfunctions [19].

- Simulation capabilities: Digital conversion can provide simulation capabilities that can help optimize system design and operation. For example, DTs can simulate system behavior under various operating conditions, allowing companies to optimize system design and identify potential problems before they occur [20].

- Data-driven decision making: Digital transformation can allow for better decision-making by availing data-driven insights as stated by [21]. For instance, system data can be analyzed for patterns and trends that may inform decisions related to system upgrades or improvements.

2.2. Current Challenges

- Integration with legacy systems: Integrating modern technology with the existing infrastructure is cumbersome and costly. In support of this process of digital transition, older WDS—which are very often incompatible with today’s IoT devices and sensors—may involve extensive upgrades [22].

- Data privacy and cybersecurity: Cybercriminals may be able to take advantage of more weaknesses as IoT devices and sensors proliferate, which might disrupt systems and expose data. For instance, a weakly secured sensor can give hackers access to compromised systems or pilfer confidential information [23].

- Proficient workforce: The management and upkeep of digital infrastructure require specialized knowledge. Utilities may face considerable challenges and must undertake substantial programmatic investments to equip their personnel with the necessary digital skills in regions lacking such expertise [24].

- Implementation costs: The initial costs of implementing digital transformation are often high, including investments in new technologies, infrastructure upgrades, and workforce training. These costs can be prohibitive for SMEs, limiting their ability to adopt advanced digital solutions and compete with larger entities [25].

- Escalating Cybersecurity Threats: As a consequence of digital transformation, a greater number of devices are being linked to the Internet, thereby augmenting the potential access points for cyberattacks. Assaults directed at critical infrastructure may lead to significant financial repercussions, harm to reputation, and even physical injury [26,27].

- Widening the digital divide: Digital transformation can exacerbate the digital gap by leaving behind people and communities who lack digital literacy or have restricted access to technology. This disparity impedes social and economic advancement and exacerbates existing inequalities [28].

- Labour Displacement: The digital transformation of WDS should align with corporate social responsibility, addressing challenges like labor displacement caused by automation and AI. Organizations can mitigate job losses by fostering trust, equitable resource distribution, and social value through stakeholder engagement by introducing training and re-skilling programs to help workers transition to new roles. Integrating DT frameworks in water management advances technical efficiency, ethical stewardship, and workforce adaptability [29].

- Privacy Issues: The significant collection and utilization of data have the potential to lead to privacy-related concerns. The implementation of digital technologies may be hindered by apprehensions regarding data security incidents or the handling of individual information, which could diminish public trust in these advancements [26,30].

2.3. DTs in Water Industry

2.3.1. DTs in Water Field: Enhancing Efficiency and Sustainability

3. Literature’s Review

3.1. Background Research

3.1.1. Early Conceptual Foundations

3.1.2. Expansion and Application in Various Water Systems

3.1.3. Developing Advanced Methodologies and Frameworks

3.1.4. Recent Developments and Future Directions

| No | Focus Area | Contributions/Goals | Methods | Case Studies/Apps | Outcomes |

| [46] 2019 | DTs in water treatment | Real-time optimization, sustainability | DTs, real-time data | North Carolina water treatment facility | 10% reduction in chemical usage, 2% water quality improvement |

| [32] 2020 | WDNs | Real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance | DTs, GIS, SCADA | Valencia, Spain | Improved operational efficiency, support for 1.6 million inhabitants |

| [47] 2020 | Smart water grids | Energy efficiency, leakage control | DTs, CPS, blockchain | Various implementations | Enhanced sustainability, resilience of urban water systems |

| [66] 2020 | Urban water cycles | Real-time control, subsystem interoperability | Cyber-physical systems, model predictive control | Barcelona, Badalona | Reduced combined sewer overflows, optimized water usage |

| [48] 2021 | Water infrastructure | Operational decision support | DTs, real-time data | Global Omnium, Aarhus Vand, DC water | Versatility and effectiveness in different contexts |

| [50] 2021 | Urban water systems | Real-time operational and control functionalities | Living and prototyping DTs | VCS Denmark | Improved system management, efficiency, resilience |

| [51] 2021 | Wastewater Management | Inter-organisational collaboration | Autonomous, limited company, central service organisation, standardisation | Finnish water utilities | Enhanced ICT development, predictive maintenance |

| [52] 2021 | Desalination plants | Membrane maintenance optimisation | DTs, decision support systems | Carlsbad desalination Plant | Reduced operational costs, enhanced membrane efficiency |

| [53] 2021 | Bio-manufacturing | Process efficiency, resource utilisation | DTs, real-time data integration | Ethanol fermentation process | Enhanced monitoring and control capabilities |

| [54] 2021 | Urban spaces and vehicles | Sustainable urban environments | DTs, sensing devices, edge computing, machine learning | Various urban applications | Improved urban planning and infrastructure |

| [7] 2022 | WDNs | Asset management, pressure control | DTs, established algorithms | Lisbon, Portugal | 28% water savings, reduced water and energy losses |

| [55] 2022 | Water infrastructure | Impact assessment of COVID-19 | DTs, AMI data, hydraulic modelling | Mid-sized utility serving 60,000 people | Altered water demand patterns, improved operational decision-making |

| [42] 2022 | WDSs | State estimation methodology | DTs, graph conventional networks | Two benchmark networks | High predictive accuracy, improved WDS monitoring |

| [10] 2022 | Smart water management | Water resource efficiency | DTs, multi-agent systems | Various implementations | Improved asset management, leak detection, system operation |

| [56] 2022 | Wastewater treatment plants | Process efficiency, resource recovery | DTs, AI, CPS | Various implementations | Reduced operational costs, enhanced system reliability |

| [57] 2023 | Potable water infrastructure | Real-time data collection, bench-marking | DTs, Levels of Service framework | Various implementations | Enhanced decision-making, operational efficiency |

| [58] 2023 | WDNs | Water loss reduction, system performance | Smart water grids, DTs | Gaula WDN, Madeira, Portugal | 80% water loss reduction, EUR 165,000 annual savings |

| [59] 2023 | Digital transformation | Digital solutions integration | DTs, real-time optimisation | Various case studies | Enhanced operational efficiency, resource management |

| [60] 2023 | Biomanufacturing | DT framework | DTs, human-machine interfaces | Ethanol fermentation | 20-33% productivity improvement |

| [63] 2023 | System operation and maintenance | Predictive maintenance, sustainability | DTs, historical and real-time data | Various implementations | Minimized maintenance costs, improved sustainability |

| [62] 2023 | WDNs | Digital transformation, AI integration | DTs, AI, machine learning, deep learning | QGIS software plugins | Improved planning, management, and design of WDNs |

| [64] 2024 | Water resource recovery | Real-time optimization, stakeholder involvement | DTs, hybrid frameworks | Changi water reclamation plant, Kolding WRRF | Significant operational efficiency improvements |

| [61] 2024 | Urban drainage models | Diagnosing uncertainties | DTs, hydrologic and hydraulic signatures | Odense, Denmark | Improved model accuracy, enhanced urban water management |

| [65] 2024 | WDSs | Optimal sensor placement | DTs, graph neural networks | Synthetic case study | High accuracy in pressure estimation, improved monitoring |

3.2. Gaps in Research

4. Proposed DTs Platform

4.1. CAUCCES Architecture

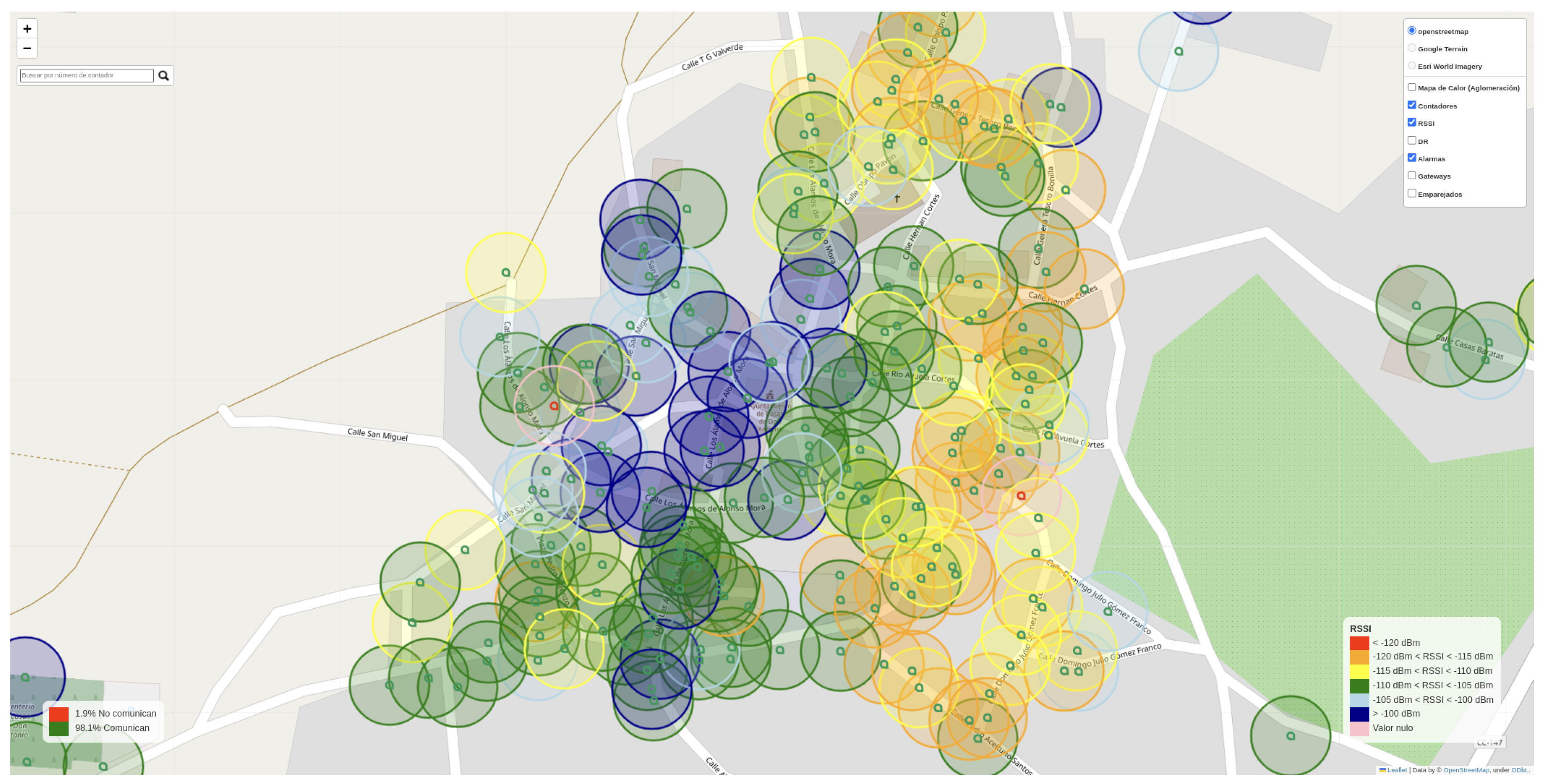

4.1.1. Cyber Physical System

- IoT Networks: These networks include IoT devices located throughout the WDS, including PLCs, meters, pumps, pipes, and gauges. Real-time data is collected at the various treatment, transmission, and distribution stages of water. The data collected becomes important in monitoring the performance of the system and determining inefficiencies or faults in the network. The deployment of IoT networks ensures extensive coverage of the entire water infrastructure with high-accuracy data capture.

- Communication: The communication layer is important for the lossless and timely delivery of data gathered by IoT devices to downstream systems. In our architecture, data from IoT devices connected via the LoRaWAN protocol are aggregated and then securely transmitted to cloud platforms for further processing; thus, this ensures that the system has strong and scalable data handling, maintaining the integrity and timeliness of critical information across the network.

4.1.2. DTs and System Integration Layer

- API and Data Management Layer: This layer is essential for data integration and management. It controls access, processing, and the exchange of data within the system in such a way as to provide a safe and orderly environment for the sharing of data through APIs. The platform provides access to the controlled data and functionality while allowing integration with other external systems; therefore, the collaboration between two or more platforms in operations becomes much more effective. The layer also ensures the system can handle large volumes of data efficiently, supporting scalability and compliance with regulations such as GDPR.

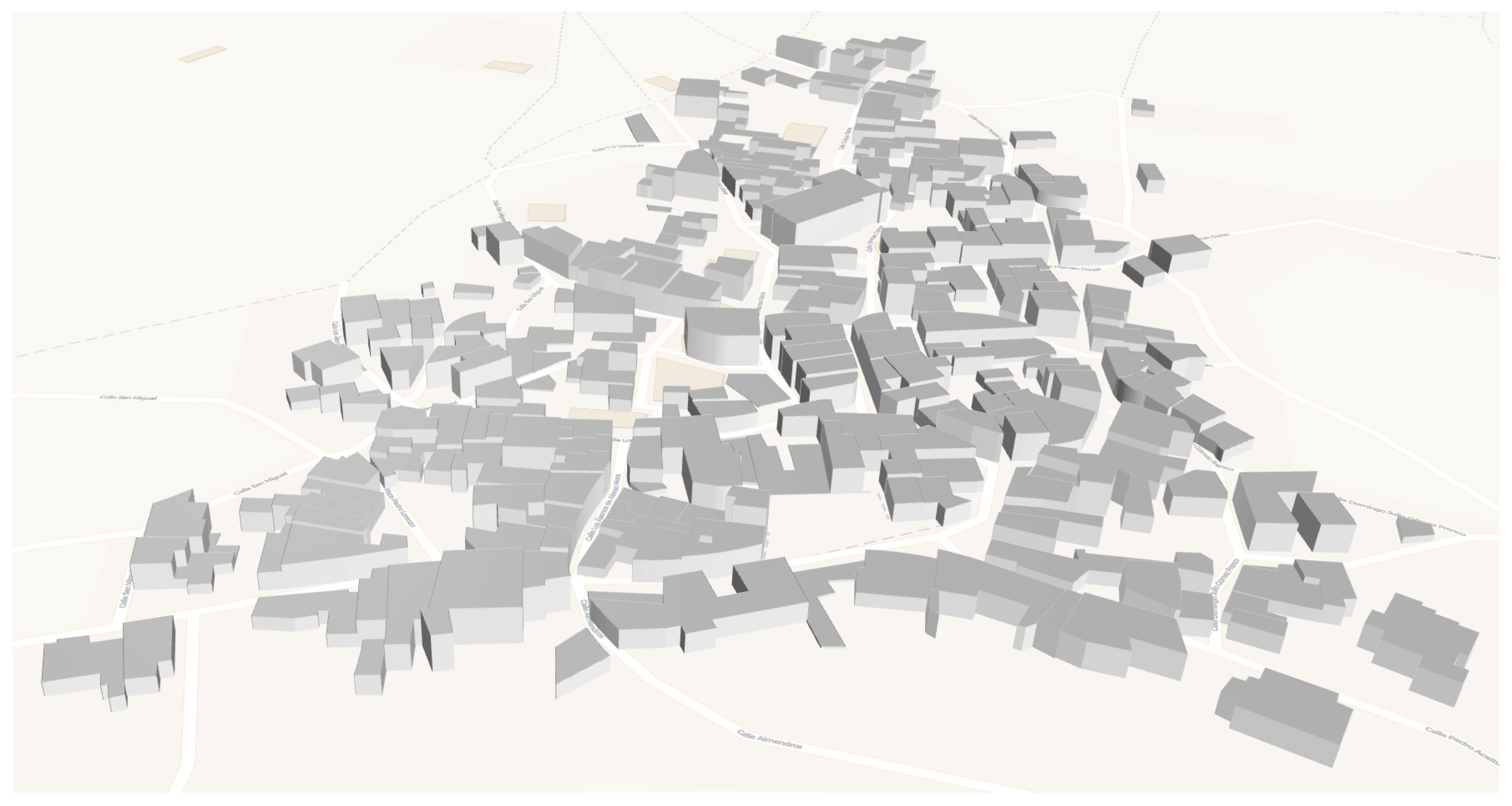

- Visual Representation in GIS: Although not a self-contained layer, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are truly part of the system architecture. GIS provides visual insight by displaying data and results of analyses on geographic maps, which significantly enhances spatial analysis. The platform supports both two-dimensional and three-dimensional mapping capabilities, as illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively, which are pivotal in visualizing and interpreting the geographic information, fundamental for both operational and strategic decision-making in the water management domain.

4.1.3. Processing and Analytics Layer

-

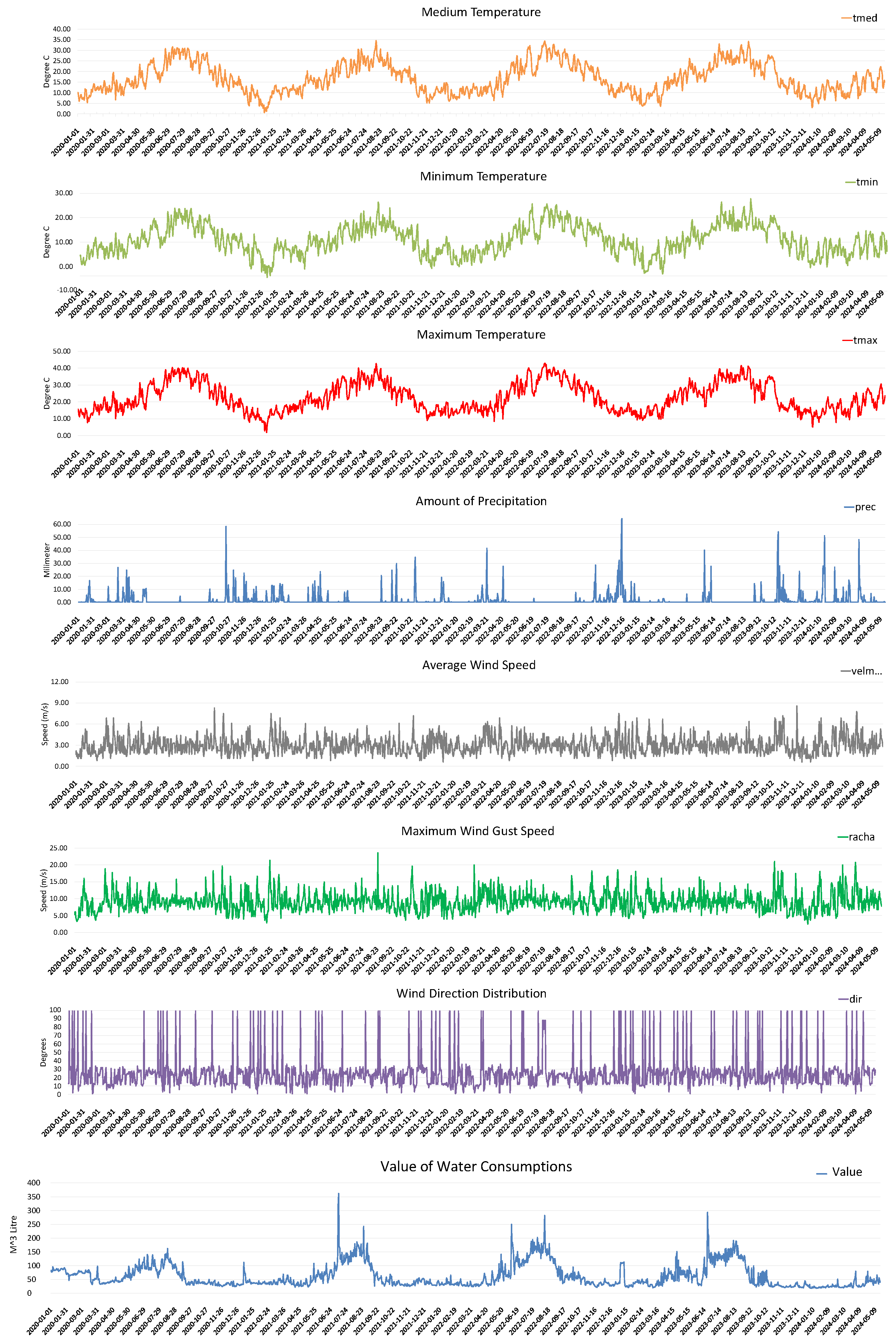

Input Data: This layer gathers diverse types of data essential for analysis:

- −

- Meteorological data is sourced via APIs from regional weather stations, providing crucial environmental context.

- −

- Historical data consists of daily and even hourly water consumption records for the village, stored in dedicated databases for trend analysis and forecasting.

- −

- Real-time data from meters, pumps, and PLC devices are continuously captured and stored in relevant databases, feeding into real-time monitoring and analysis models.

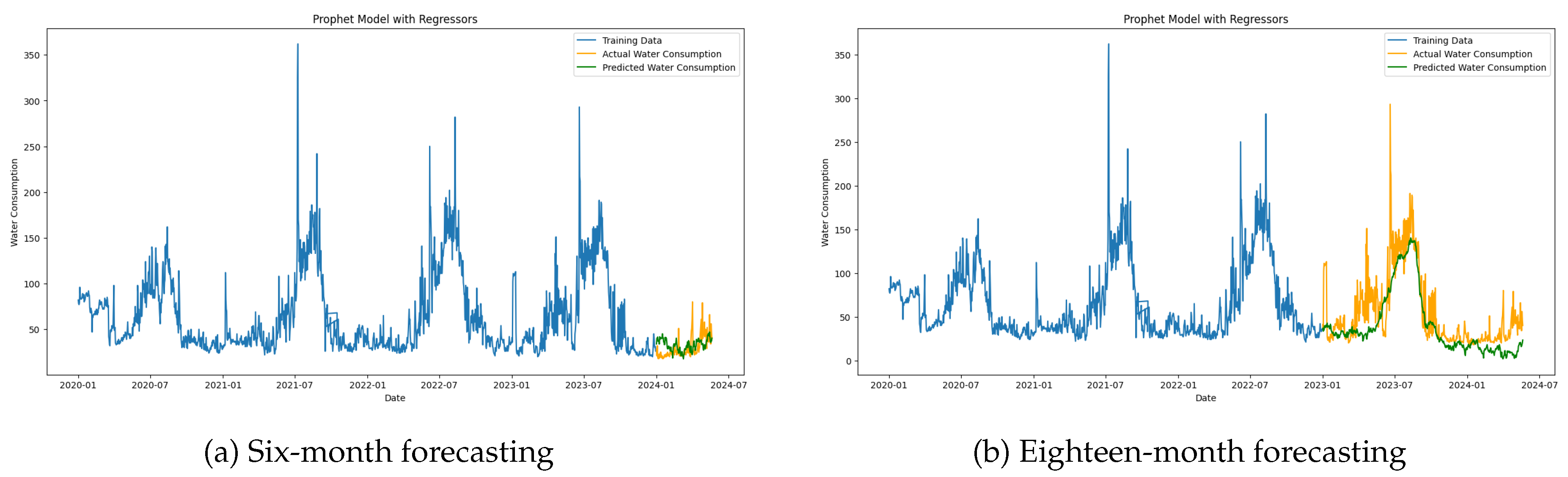

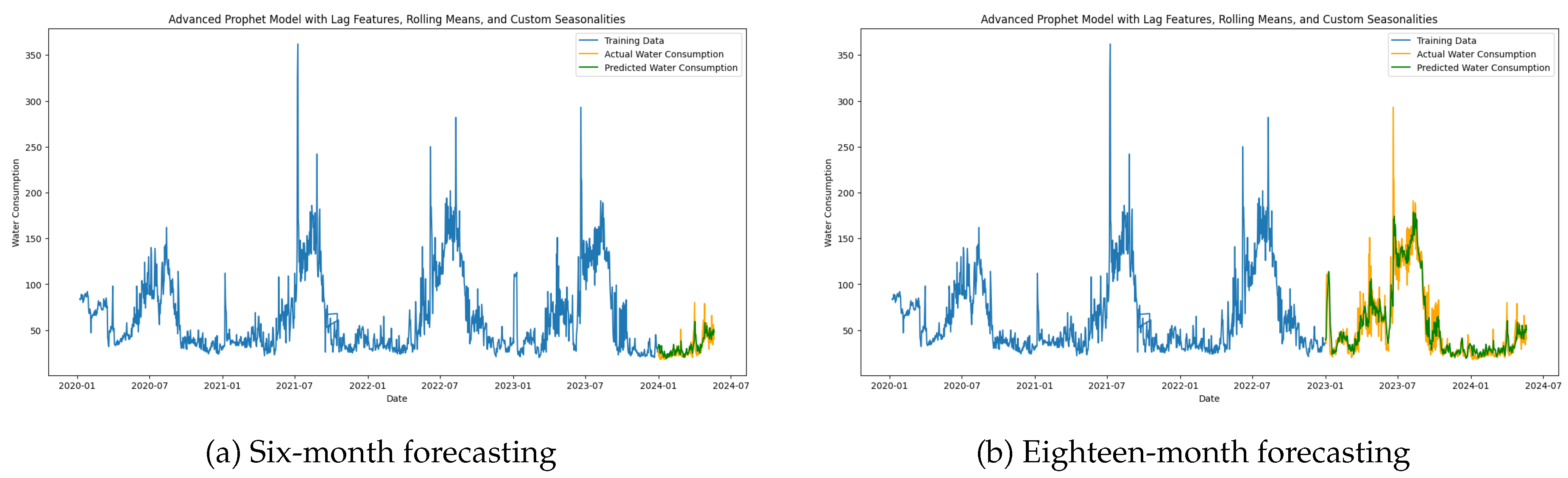

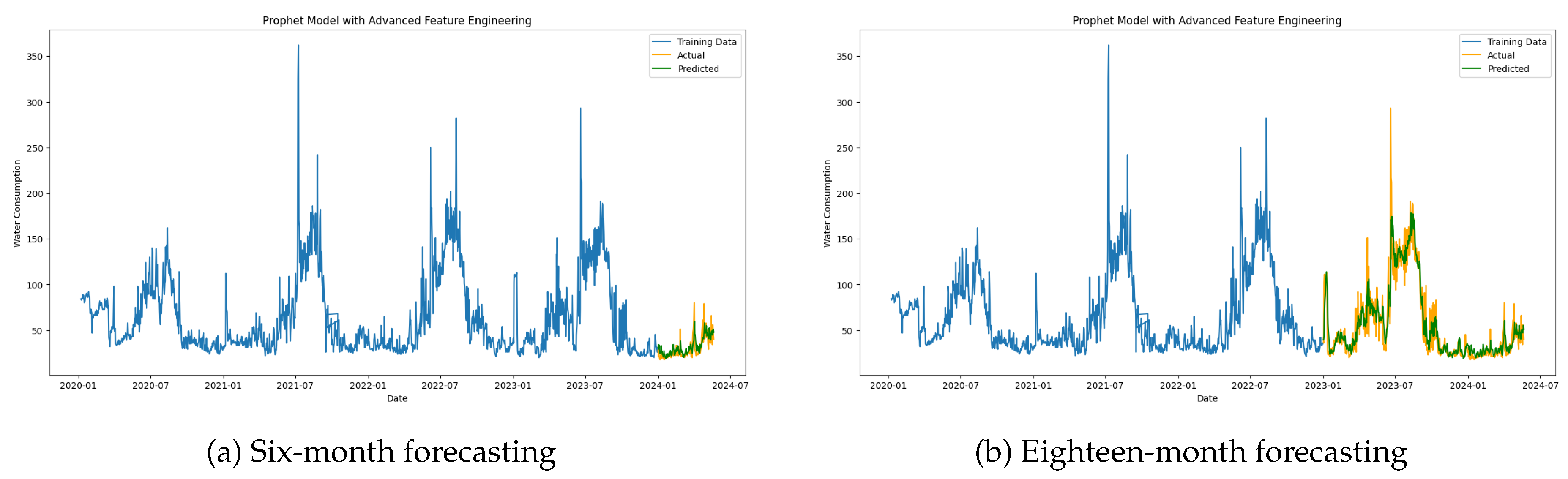

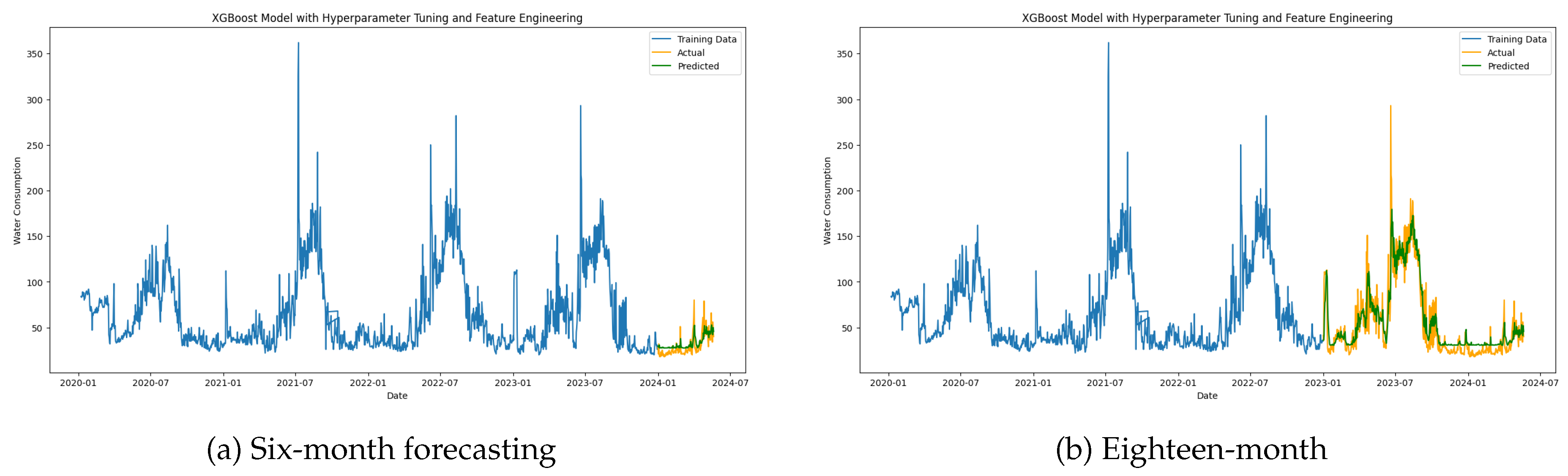

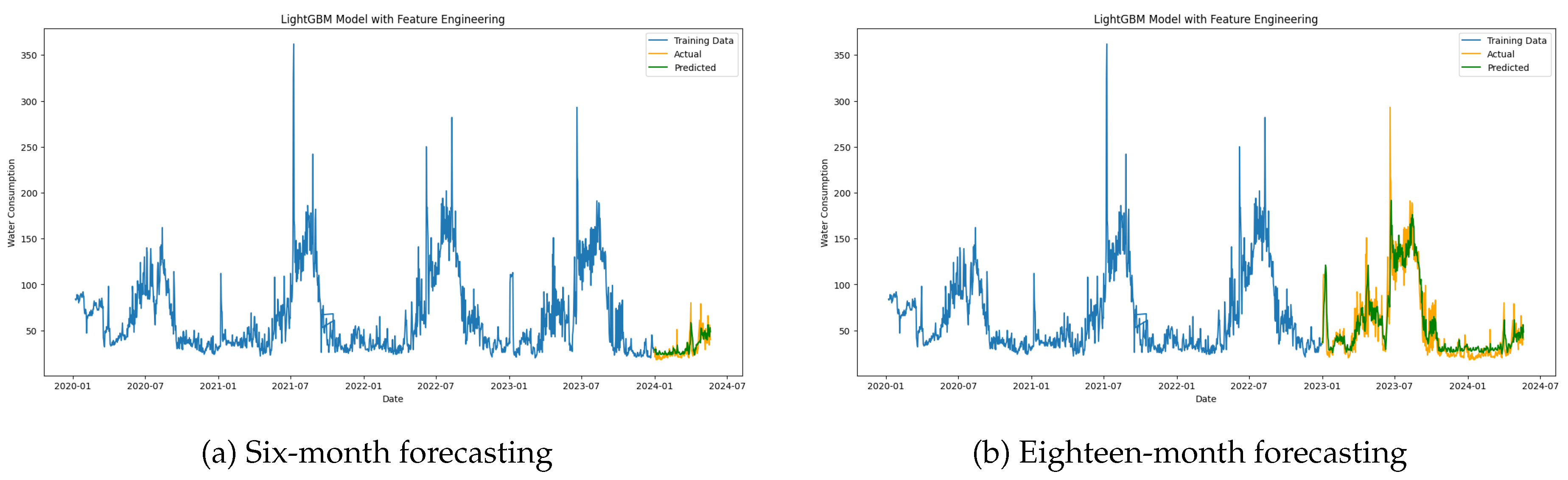

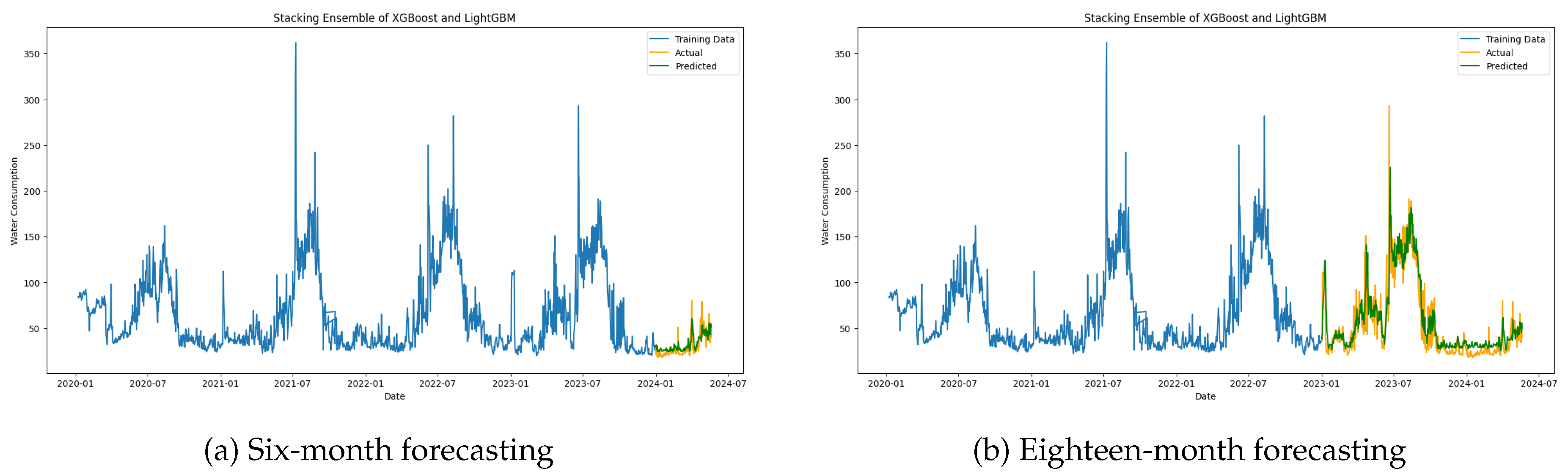

- Artificial Intelligence Models and Forecasting: A key component of this layer is the AI/ML process stage, where artificial intelligence and machine learning models analyze historical and real-time data. To forecast water consumption, we employed a combination of advanced models to forecast water consumptions, including LSTM, Prophet, LightGBM, and XGBoost. These models enable the system to perform extensive optimization and computational tasks, predict future water demand, detect network leaks, and calculate energy usage and carbon dioxide emissions. Integrating time series data allows for highly accurate forecasting and efficient resource management [68].

- Business Intelligence and Dashboard Tools: Processed data is presented visually through intuitive dashboards and detailed reports, providing users with real-time insights and historical data analysis. These tools empower decision-makers to make informed, data-driven choices, ensuring operational efficiency and long-term sustainability in water management.

5. Integrating AI/ML in Water Consumption Prediction

5.1. Data Aggregation and Pre-Processing

5.2. Meteorological Variables

5.3. LSTM Model

| Algorithm 1 LSTM for water consumption forecasting |

|

5.4. Prophet Model

- is the forecasted water consumption at time t,

- represents the growth trend component (linear or logistic),

- denotes the seasonal component modeled using Fourier series to capture annual and weekly patterns,

- accounts for holiday effects using indicator functions,

- is the maximum temperature on day t,

- quantifies the impact of temperature on water consumption,

- is the error term, assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero.

- represents all model parameters, including , trend, and seasonal components,

- is the actual water consumption,

- is the predicted water consumption based on parameters .

| Algorithm 2 Prophet for water consumption forecasting |

|

5.5. LightGBM Model with Feature Engineering

-

Objective Function: The model minimizes an objective function that combines a loss function with a regularization term to prevent overfitting:where:

- −

- is the actual water consumption at time i,

- −

- is the predicted water consumption,

- −

- is the loss function, typically MSE for regression tasks,

- −

- is the regularization term for the complexity of the trees T.

-

Feature Engineering: Various features were created to enhance the model’s predictive performance:

- −

- Lag Features: Previous water consumption and temperature values were included to capture temporal dependencies:where k is the lag period (e.g., 1 day, 7 days).

- −

- Rolling Means: Moving averages were computed to smooth out short-term fluctuations:where w is the window size (e.g., 7 days).

- −

- Temporal Indicators: Features such as day of the week and weekend indicators were added to capture weekly seasonal patterns:

- Data Normalization: Feature scaling was performed using standardization to ensure that all features contribute equally to the model training:where x represents the original feature value, is the mean, and is the standard deviation of the feature.

| Algorithm 3 LightGBM with Feature Engineering for Water Consumption Prediction |

|

5.6. XGBoost Model with Feature Engineering

| Algorithm 4 XGBoost with Hyperparameter Tuning and Feature Engineering |

|

5.7. Model Evaluation

6. Optimizing WDS Maintenance

-

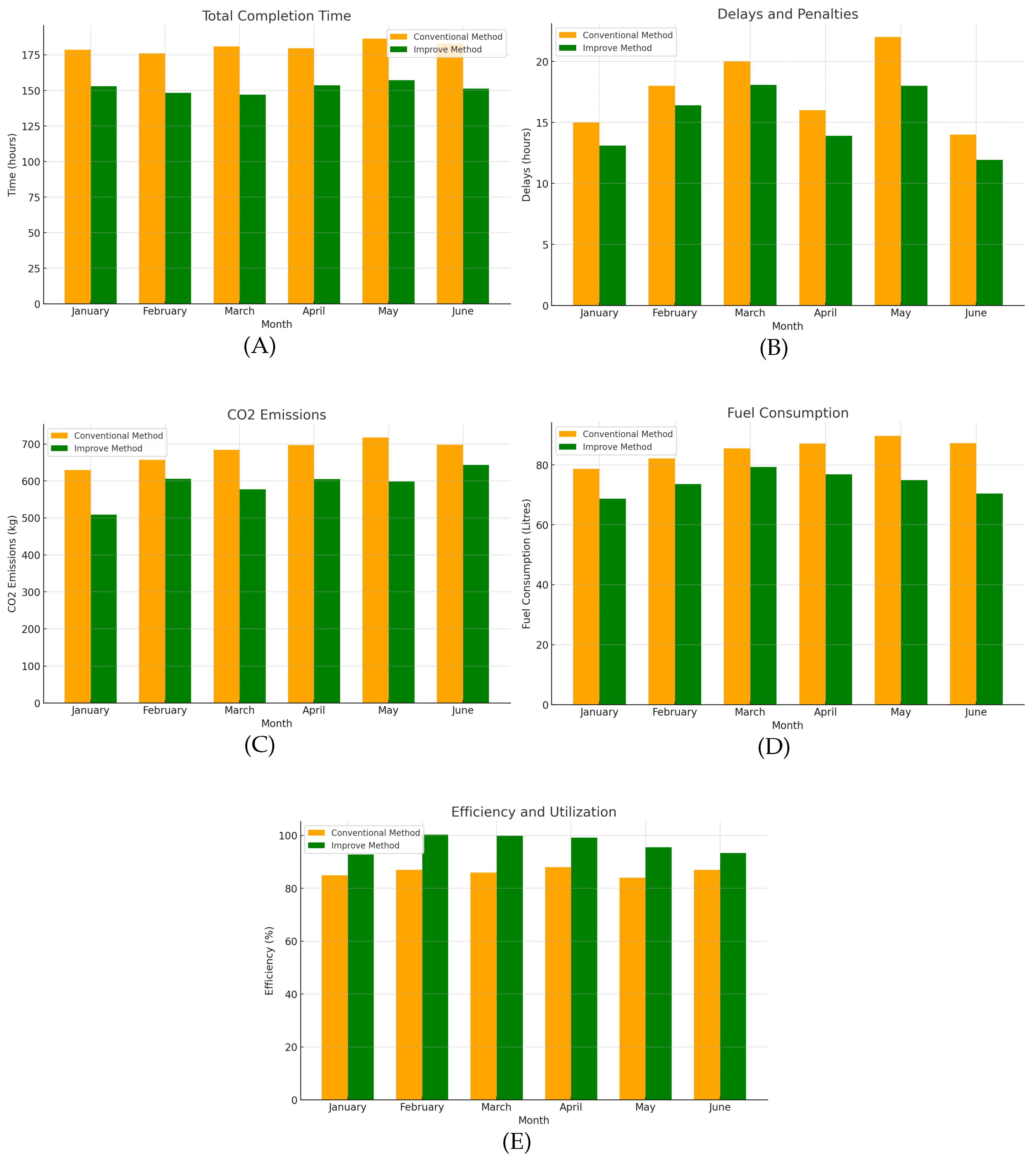

Mathematical ModelWe have adapted the model to be compatible with CP, focusing on deterministic parameters. Uncertainties in processing and travel times are handled using expected or conservative estimates. The model aims to optimize the objectives while satisfying all constraints.The objectives are to:

- −

- Minimize the total completion time ().

- −

- Minimize the total fuel consumption ().

- −

- Minimize the total CO2 emissions ().

- −

- Minimize the total delays and penalties ().

-

Sets and Indices

- −

- Let T be the set of all tasks indexed by i.

- −

- Let be the set of processing segments for task i due to preemption, indexed by k.

- −

- Let D be the set of task dependencies, where means task j depends on task i.

- Parameters

-

For each task :

- −

- : Deterministic processing time required for task i (in hours), based on expected or conservative estimates.

- −

- : Deterministic travel time from task i to task j (in hours), based on expected or conservative estimates.

- −

- : Fuel consumption for processing task i (in liters).

- −

- : CO2 emissions for processing task i (in kg).

- −

- : Location coordinates of task i.

- −

- : Priority level of task i (higher value indicates higher priority).

- −

- : Task’s release time (arrival time). For regular tasks, ; for emergency tasks, .

- −

- : Distance from task i to task j (in kilometers).

- −

- : Fuel efficiency of vehicle type v (in km per liter).

- −

- : Emission factor of vehicle type v (in kg CO2 per liter of fuel).

- −

- S: Start of the working day (e.g., 8:00 AM).

- −

- E: End of the working day (e.g., 3:00 PM).

- −

- : Vehicle type required for task i (e.g., Van, Small Truck).

- −

- MaxPreemptions: Maximum allowed number of preemptions per task.

-

Decision Variables

- −

-

Task Scheduling Variables: Variables that define when each task or task segment starts and ends.

- *

- : Scheduled start time of segment k of task i.

- *

- : Scheduled completion time of segment k of task i.

- *

- : Scheduled processing time of segment k of task i.

- *

- : Number of segments into which task i is divided due to preemption, where .

- −

-

Sequencing Variables: Binary variables that determine the order in which tasks are performed relative to each other.

- *

- : Binary variable; if task i is scheduled immediately before task j, 0 otherwise.

- −

-

Auxiliary Variables:

- *

- : Binary variable; if task i is preempted, 0 otherwise.

- *

- : Binary variable; if task j depends on task i, 0 otherwise.

- *

- : Binary variable indicating if segment k of task i is scheduled before segment l of task j.

-

Objective FunctionWhere:

- −

- are the weights for time, fuel consumption, CO2 emissions, and delays and penalties, respectively.

- −

- : Completion time of the last task segment.

- −

- : Total fuel consumption for processing and traveling.

- −

- : Total CO2 emissions for processing and traveling.

- −

- : Total delays for emergency tasks beyond their release times.

- Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emissions for Traveling

-

Constraints

- −

- Processing Time Constraints: Ensure that each task’s total scheduled processing time, including preempted segments, matches the required time.

- −

-

Segment Completion Constraints:For all segments k of task i:

- −

-

Precedence Constraints for Task Dependencies:If task j depends on task i (i.e., ):This ensures that task j cannot start before task i is completed.

- −

-

Travel Time Constraints:When task i is scheduled immediately before task j:

- −

-

Non-Overlap Constraints (Single-Machine Constraint):To prevent overlapping of processing times on the single machine, we include the following constraints for all tasks and their segments k and l:Where:

- *

- is the completion time of segment k of task i.

- *

- is the start time of segment k of task i.

- *

- is a binary variable defined as:

- *

- M is a sufficiently large positive constant.

- −

-

Work Hours Constraints:Ensure tasks are scheduled within working hours:

- −

-

Emergency Task Constraints:

- *

- Release Time Constraint:

- *

- Delay Penalties: Delays for emergency tasks are included in the objective function through as shown in Equation (21).

- −

- Limit on Preemptions:

- −

-

Sequencing Constraints:Ensure that each task is preceded and succeeded by at most one other task:

- −

-

Subtour Elimination Constraints (Miller-Tucker-Zemlin constraints):Introduce variables for each task i:

-

Performance MetricsIn addition to the objective function, we define the following performance metrics to evaluate the scheduling model:

- −

-

Total Delays and Penalties ():This represents the total delay beyond the release times for all tasks.

- −

- Efficiency and Utilization ():This represents the percentage of time spent on processing tasks relative to the total time from the start to the completion of all tasks.

| Algorithm 5 CP for Scheduling Problem |

|

7. Security Layer in DTs Platform

8. Conclusions

Declarations

- Funding: This project is carried out within the framework of the funds of the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, financed by the European Union (Next Generation). The publication is part of the Spanish Strategic Cybersecurity Project “Artificial Intelligence applied to Cybersecurity in Critical Water and Sanitation Infrastructures (***/**)” funded by Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad de España (INCIBE).

- Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

- Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

- Consent for publication: Not applicable.

- Data and code availability: All code and datasets used in this study are publicly available at https://github.com/Homaei/DigitalTwin-Water-ML.

- Materials availability: Not applicable.

- Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to the conception, design, drafting, and revision of the manuscript.

Appendix A Lemma and Proof of Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient

Appendix B Explanation of Non-Overlap Constraints

-

When :

-

When :

References

- Hu, Z.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Tan, D.; Shen, D. Review of model-based and data-driven approaches for leak detection and location in water distribution systems. Water Supply 2021, 21, 3282–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAYIOĞLU, M.A.; TURKER, U. Digital Transformation for Sustainable Future - Agriculture 4.0 : A review. Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Stevens, B.; Hazeleger, W. A digital twin of Earth for the green transition. Nature Climate Change 2021, 11, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, H.; Lade, M. Impact of Digital Transformation on Carbon Emissions Reductions in the Water Industry. In Lecture Notes in Energy; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp. 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M. Digital Transformation of the Agricultural Sector: Pathways, Drivers and Policy Implications. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 2020, 43, 1221–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Cumo, F.; Guidi, G.; Tomazzoli, C. Cyber-Physical Systems Improving Building Energy Management: Digital Twin and Artificial Intelligence. Energies 2021, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.B.; Giustolisi, O. Digital Transformation Paradigm for Asset Management in Water Distribution Networks. 2021 10th International Conference on ENERGY and ENVIRONMENT (CIEM). IEEE, 2021, pp. 760–765. [CrossRef]

- Jagani, S.; Deng, X.; Hong, P.C.; Mashhadi Nejad, N. Adopting sustainability business models for value creation and delivery: An empirical investigation of manufacturing firms. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2023, 35, 360–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yin, S.; Li, K.; Luo, H.; Kaynak, O. Industrial applications of digital twins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2021, 379, 20200360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zekri, S.; Jabeur, N.; Gharrad, H. Smart Water Management Using Intelligent Digital Twins. Computing and Informatics 2022, 41, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylianidis, C.; Osinga, S.; Athanasiadis, I.N. Introducing digital twins to agriculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 184, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C.; Ryan, G.; Bhandari, P.; Law, K.M.Y.; Gong, J.; Creighton, D. Digital Transformation in Water Organizations. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaker, T.; Ly, P.T.M.; Nguyen-Thanh, N.; Nguyen, H.T.H. Business model innovation through the application of the Internet-of-Things: A comparative analysis. Journal of Business Research 2021, 126, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivoto, D.G.; de Almeida, L.F.; da Rosa Righi, R.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Lugli, A.B.; Alberti, A.M. Cyber-physical systems architectures for industrial internet of things applications in Industry 4.0: A literature review. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 58, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, A.K.; Zo, H.; Chiravuri, A. Digital Transformation and Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcicki, K.; Biegańska, M.; Paliwoda, B.; Górna, J. Internet of Things in Industry: Research Profiling, Application, Challenges and Opportunities—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali Sepehr, M.; Mashhadi Nejad, N. Exploring Strategic National Research and Development Factors for Sustainable Adoption of Cellular Agriculture Technology. Proceedings of the 2024 Midwest Decision Sciences Institute Conference. Decision Sciences Institute, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Botín-Sanabria, D.M.; Mihaita, A.S.; Peimbert-García, R.E.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Ramírez-Mendoza, R.A.; de, J. Lozoya-Santos, J. Digital Twin Technology Challenges and Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futai, M.M.; Bittencourt, T.N.; Carvalho, H.; Ribeiro, D.M. Challenges in the application of digital transformation to inspection and maintenance of bridges. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2022, 18, 1581–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Fuenmayor, E.; Hinchy, E.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Digital Twin: Origin to Future. Applied System Innovation 2021, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, S.; Florian, E.; Zennaro, I.; Orrù, P.; Sgarbossa, F. A novel decision support system for managing predictive maintenance strategies based on machine learning approaches. Safety science 2022, 146, 105529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Prügl, R. Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research. Management Review Quarterly 2020, 71, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendhurwar, S.; Mishra, R. Integration of social and IoT technologies: Architectural framework for digital transformation and cyber security challenges. Enterprise Information Systems 2019, 15, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broo, D.G.; Schooling, J. Digital twins in infrastructure: Definitions, current practices, challenges and strategies. International Journal of Construction Management 2021, 23, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.; Fehér, P.; Kovacs, T.; Mitev, A.; Szabó, Z. Influencing factors of digital transformation: Management or IT is the driving force? International Journal of Innovation Science 2021, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaei, M.; Óscar, Mogollón-Gutiérrez.; Sancho, J.C.; Ávila, M.; Caro, A. A review of digital twins and their application in cybersecurity based on artificial intelligence. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Leading digital transformation: Three emerging approaches for managing the transition. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 2020, 40, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Castillo, A. Digital Transformation and the Public Sector Workforce:: An exploration and research agenda. 14th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance. ACM, 2021, ICEGOV 2021, pp. 471–475. [CrossRef]

- Callaway, S.; Mashhadi Nejad, N. Innovating Toward CSR: Creating Value by Empowering Employees, Customers, and Stockholders. SSRN Electronic Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadornil Renedo, D., Ed. The role of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Twin’s Cybersecurity. Editorial Universidad de Cantabria, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shahi, C.; Sinha, M. Digital transformation: Challenges faced by organizations and their potential solutions. International Journal of Innovation Science 2020, 13, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejos Fuertes, P.; Martínez Alzamora, F.; Hervás Carot, M.; Alonso Campos, J. Building and exploiting a Digital Twin for the management of drinking water distribution networks. Urban Water Journal 2020, 17, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, S.; Anderl, R. Digital twin – Proof of concept. Manufacturing Letters 2018, 15, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketzler, B.; Naserentin, V.; Latino, F.; Zangelidis, C.; Thuvander, L.; Logg, A. Digital Twins for Cities: A State of the Art Review. Built Environment 2020, 46, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L. Digital Twins of Smart Cities: Spatial Data Visualization Tools, Monitoring and Sensing Technologies, and Virtual Simulation Modeling. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 2022, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravid, B.Y.; Aharon-Gutman, M. The Social Digital Twin:The Social Turn in the Field of Smart Cities. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2022, p. 239980832211370. [CrossRef]

- Bariah, L.; Sari, H.; Debbah, M. Digital Twin-Empowered Smart Cities: A New Frontier of Wireless Networks. TechRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, H.J.; Schneider, R.; Koch, J.; Ondracek, M.; Troldborg, L.; Seidenfaden, I.K.; Kragh, S.J.; Bøgh, E.; Stisen, S. A New Digital Twin for Climate Change Adaptation, Water Management, and Disaster Risk Reduction (HIP Digital Twin). Water 2022, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, I. Application of Digital Transformation in the Water Desalination Industry to Develop Smart Desalination Plants. Master’s thesis, College of Engineering and Computing, University of South Carolina, 2021.

- Savić, D. Digital water developments and lessons learned from automation in the car and aircraft industries. Engineering 2022, 9, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.; Morani, M.C.; Carravetta, A.; Fecarrotta, O.; Adeyeye, K.; López-Jiménez, P.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, M. New Challenges towards Smart Systems’ Efficiency by Digital Twin in Water Distribution Networks. Water 2022, 14, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, C.A.; Zanfei, A.; Brentan, B.; Montalvo, I.; Izquierdo, J. A Digital Twin of a Water Distribution System by Using Graph Convolutional Networks for Pump Speed-Based State Estimation. Water 2022, 14, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Law, A.W.K.; Yang, C.; Tang, D. Combined Anomaly Detection Framework for Digital Twins of Water Treatment Facilities. Water 2022, 14, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarrán, J.C.; Ramírez, E.C.; Salazar, L.A.C.; Astudillo, Y.A.P. Digital Twin in Water Supply Systems to Industry 4.0: The Holonic Production Unit. In Service Oriented, Holonic and Multi-Agent Manufacturing Systems for Industry of the Future; Springer International Publishing, 2021; pp. 42–54. [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi Nejad, N.; Alvarado-Vargas, M.J.; Jalali Sepehr, M. Refining Literature Review Strategies: Analyzing Big Data Trends Across Journal Tiers. Academy of Management Proceedings 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curl, J.M.; Nading, T.; Hegger, K.; Barhoumi, A.; Smoczynski, M. Digital Twins: The Next Generation of Water Treatment Technology. Journal AWWA 2019, 111, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudicianni, C.; Herrera, M.; Nardo, A.d.; Adeyeye, K.; Ramos, H.M. Overview of Energy Management and Leakage Control Systems for Smart Water Grids and Digital Water. Modelling 2020, 1, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Pérez, B.; Johnson, B.; Wärff, C.; Lumley, D.; Torfs, E.; Nopens, I.; Townley, L. Digital Water-Operational digital twins in the urban water sector: case studies. International Water Association, London, UK, White paper 2021.

- Garrido-Baserba, M.; Corominas, L.; Cortés, U.; Rosso, D.; Poch, M. The Fourth-Revolution in the Water Sector Encounters the Digital Revolution. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, 54, 4698–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.N.; Borup, M.; Brink-Kjær, A.; Christiansen, L.E.; Mikkelsen, P.S. Living and Prototyping Digital Twins for Urban Water Systems: Towards Multi-Purpose Value Creation Using Models and Sensors. Water 2021, 13, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietala, H.; Rossi, P.M.; Annanperä, E.; Päivärinta, T. Modes of collaboration in digital transformation of municipal wastewater management. 29th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2021), Marrakech, Morocco (Virtual), June 14-16, 2021. Association for Information Systems, 2021, pp. 1470–1486.

- van Rooij, F.; Scarf, P.; Do, P. Planning the restoration of membranes in RO desalination using a digital twin. Desalination 2021, 519, 115214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udugama, I.A.; Lopez, P.C.; Gargalo, C.L.; Li, X.; Bayer, C.; Gernaey, K.V. Digital Twin in biomanufacturing: Challenges and opportunities towards its implementation. Systems Microbiology and Biomanufacturing 2021, 1, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botín-Sanabria, D.M.; Lozoya-Reyes, J.G.; Vargas-Maldonado, R.C.; Rodríguez-Hernández, K.L.; Ramírez-Mendoza, R.A.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J. Digital Twin for Urban Spaces: An Application. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 2021, pp. 2880–2891.

- Pesantez, J.E.; Alghamdi, F.; Sabu, S.; Mahinthakumar, G.; Berglund, E.Z. Using a digital twin to explore water infrastructure impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 77, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheri, A.N.; Mohamed, B.; Ntuli, F.; Nabadda, E.; Ngila, J.C. Sustainable circularity and intelligent data-driven operations and control of the wastewater treatment plant. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 2022, 126, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodanwala, T.C.; Ruparathna, R. A Levels of Service (LOS) Digital Twin for Potable Water Infrastructure Systems. Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering Annual Conference 2023. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023, pp. 15–37.

- Ramos, H.M.; Kuriqi, A.; Besharat, M.; Creaco, E.; Tasca, E.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; Pienika, R.; Iglesias-Rey, P. Smart Water Grids and Digital Twin for the Management of System Efficiency in Water Distribution Networks. Water 2023, 15, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grievson, O.; Holloway, T.; Johnson, B. A Strategic Digital Transformation for the Water Industry; IWA Publishing, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Jin, Y.; Sun, S.; Yuan, Z.; Butler, D. The role of deep learning in urban water management: A critical review. Water Research 2022, 223, 118973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.N.; Pedersen, J.W.; Borup, M.; Brink-Kjær, A.; Christiansen, L.E.; Mikkelsen, P.S. Using multi-event hydrologic and hydraulic signatures from water level sensors to diagnose locations of uncertainty in integrated urban drainage models used in living digital twins. Water Science and Technology 2022, 85, 1981–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gino Ciliberti, F.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.B.; David Ariza, A.; Vanessa Enriquez, L.; Giustolisi, O. From digital twin paradigm to digital water services. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.; Kuriqi, A.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; López-Jiménez, P.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, M. Are digital twins improving urban-water systems efficiency and sustainable development goals? Urban Water Journal 2023, p. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Torfs, E.; Nicolaï, N.; Daneshgar, S.; Copp, J.B.; Haimi, H.; Ikumi, D.; Johnson, B.; Plosz, B.B.; Snowling, S.; Townley, L.R.; Valverde-Pérez, B.; Vanrolleghem, P.A.; Vezzaro, L.; Nopens, I., The transition of WRRF models to digital twin applications. In Modelling for Water Resource Recovery; IWA Publishing, 2024; chapter 6, pp. 2840–2853. [CrossRef]

- Menapace, A.; Zanfei, A.; Herrera, M.; Brentan, B. Graph Neural Networks for Sensor Placement: A Proof of Concept towards a Digital Twin of Water Distribution Systems. Water 2024, 16, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Puig, V.; Cembrano, G. Real-Time Control of Urban Water Cycle under Cyber-Physical Systems Framework. Water 2020, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaei, M. Ambling, 2024. 04 Apr 2024.

- Khazrak, I. A Study on Corporate Carbon Footprint Using Panel Data Analysis. Master’s thesis, Bowling Green State University, OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, 2023. Committee: Yuhang Xu, Ph.D. (Committee Chair); Shuchismita Sarkar, Ph.D. (Committee Member); Sophie Song, Ph.D. (Committee Member).

- Agency, T.S.M. AEMET OpenData, 2024. Accessed: 04 Apr 2024.

- Niknam, A.; Zare, H.K.; Hosseininasab, H.; Mostafaeipour, A. Developing an LSTM model to forecast the monthly water consumption according to the effects of the climatic factors in Yazd, Iran. Journal of Engineering Research 2023, 11, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guikema, S.; Flage, R. Digital twins as a security risk? Risk Analysis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Law, A.W.K.; Yang, C. Real-Time Data-Processing Framework with Model Updating for Digital Twins of Water Treatment Facilities. Water 2022, 14, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Date | The date when the data was recorded (year-month-day format). |

| Tmed | Average air temperature in °C, calculated from daily max and min temps. |

| Prec | Total precipitation in millimeters accumulated during the day. |

| Tmin | Minimum air temperature in degrees Celsius recorded during the day. |

| Hourtmin | The time (hh:mm format) when the minimum air temperature was recorded. |

| Tmax | Maximum air temperature in degrees Celsius recorded during the day. |

| Houratmax | The time (hh:mm format) when the maximum air temperature was recorded. |

| Dir | Average wind direction, derived from 10-minute instantaneous recordings, in degrees. |

| Velmedia | Average wind speed, derived from 10-minute instantaneous recordings, in m/s. |

| Maxvel | Maximum wind speed in meters per second recorded during the day. |

| Hourracha | The time (hh:mm format) when the maximum wind speed was recorded. |

| Sun | Duration of sunshine in hours recorded during the day. |

| PresMax | Maximum atmospheric pressure in hectopascals recorded during the day. |

| HouraPresMax | The time (hh:mm format) when the maximum atmospheric pressure was recorded. |

| PresMin | Minimum atmospheric pressure in hectopascals recorded during the day. |

| HourPresMin | The time (hh:mm format) when the minimum atmospheric pressure was recorded. |

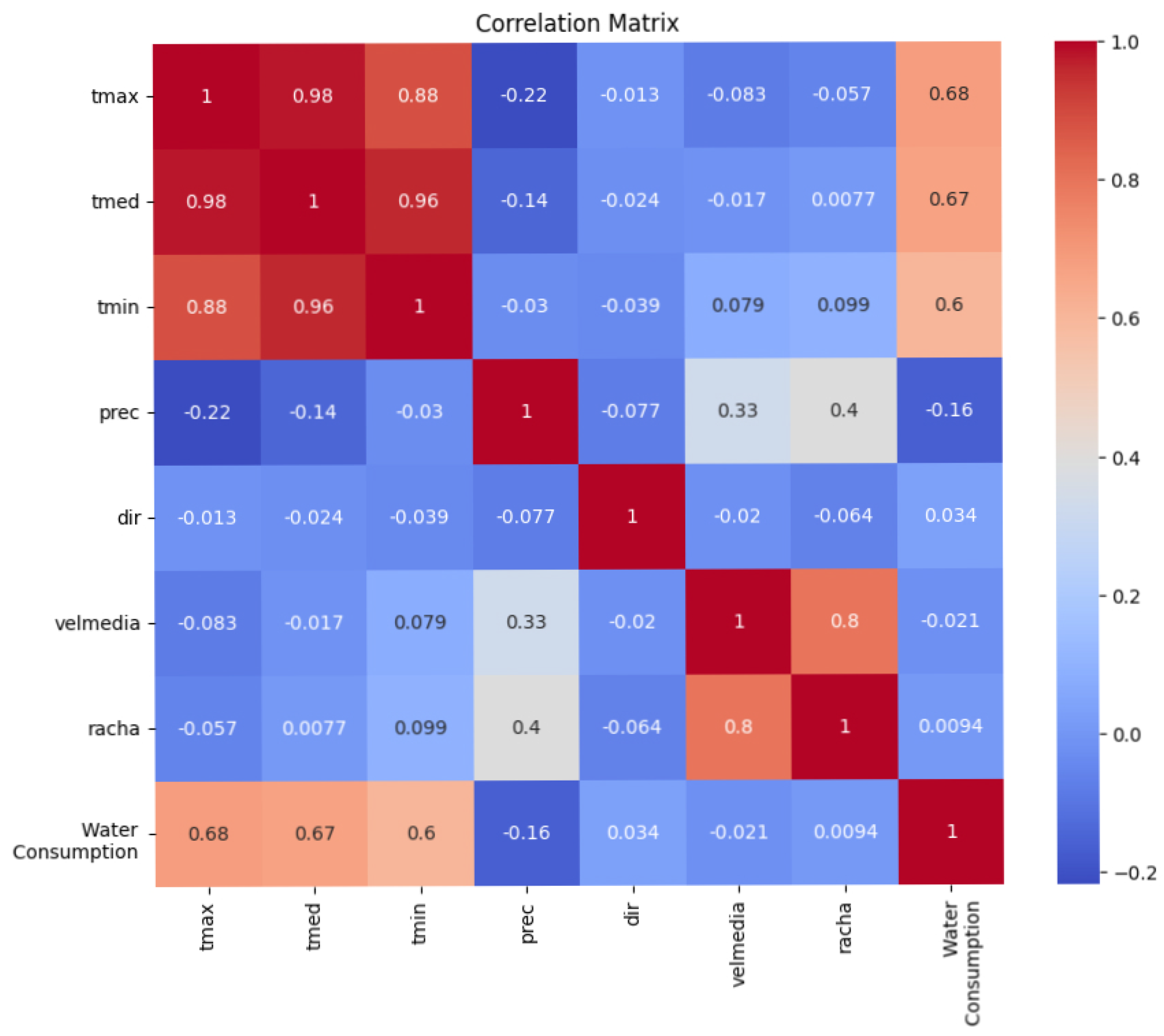

| Climatic Factor | tmax | tmed | tmin | prec | dir | velmedia | racha | Water Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tmax | 1.000 | 0.980 | 0.884 | -0.217 | -0.013 | -0.083 | -0.057 | 0.683 |

| tmed | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.959 | -0.144 | -0.024 | -0.017 | 0.008 | 0.669 |

| tmin | 0.884 | 0.959 | 1.000 | -0.030 | -0.039 | 0.079 | 0.099 | 0.604 |

| prec | -0.217 | -0.144 | -0.030 | 1.000 | -0.077 | 0.330 | 0.395 | -0.160 |

| dir | -0.013 | -0.024 | -0.039 | -0.077 | 1.000 | -0.020 | -0.064 | 0.034 |

| velmedia | -0.083 | -0.017 | 0.079 | 0.330 | -0.020 | 1.000 | 0.800 | -0.021 |

| racha | -0.057 | 0.008 | 0.099 | 0.395 | -0.064 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.009 |

| Water Cons | 0.683 | 0.669 | 0.604 | -0.160 | 0.034 | -0.021 | 0.009 | 1.000 |

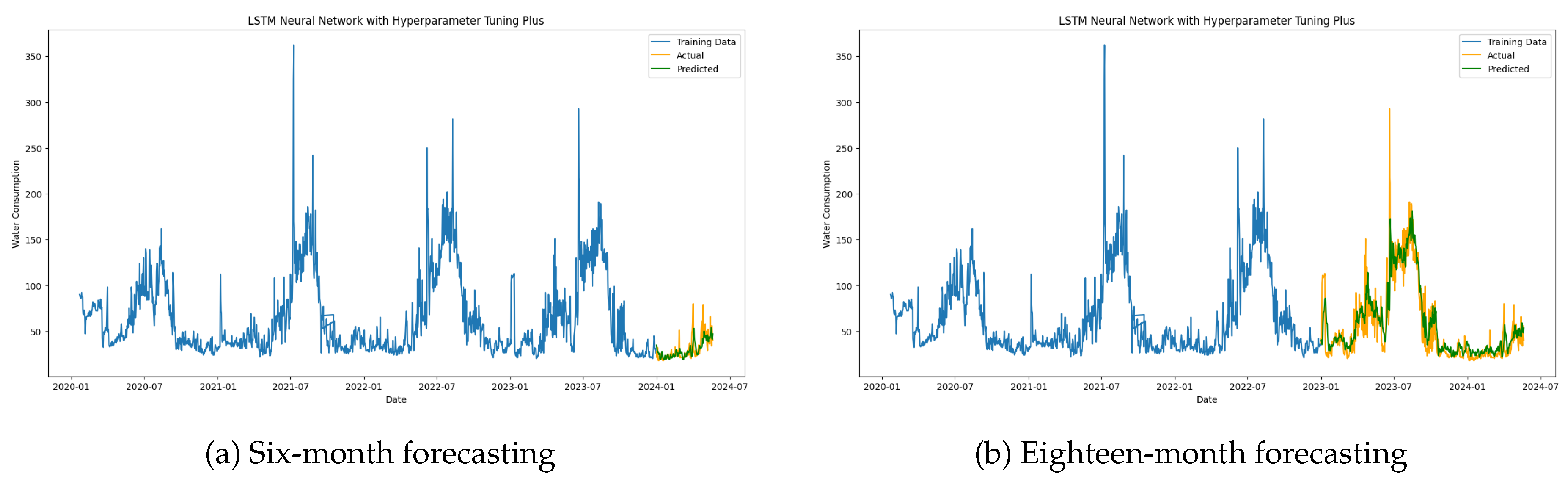

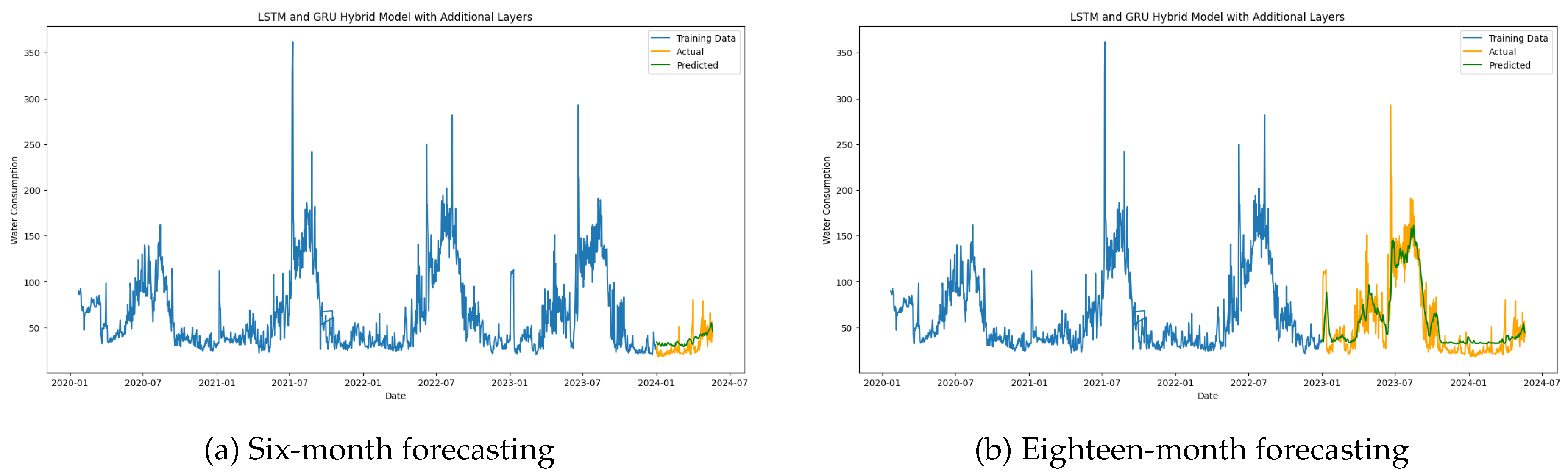

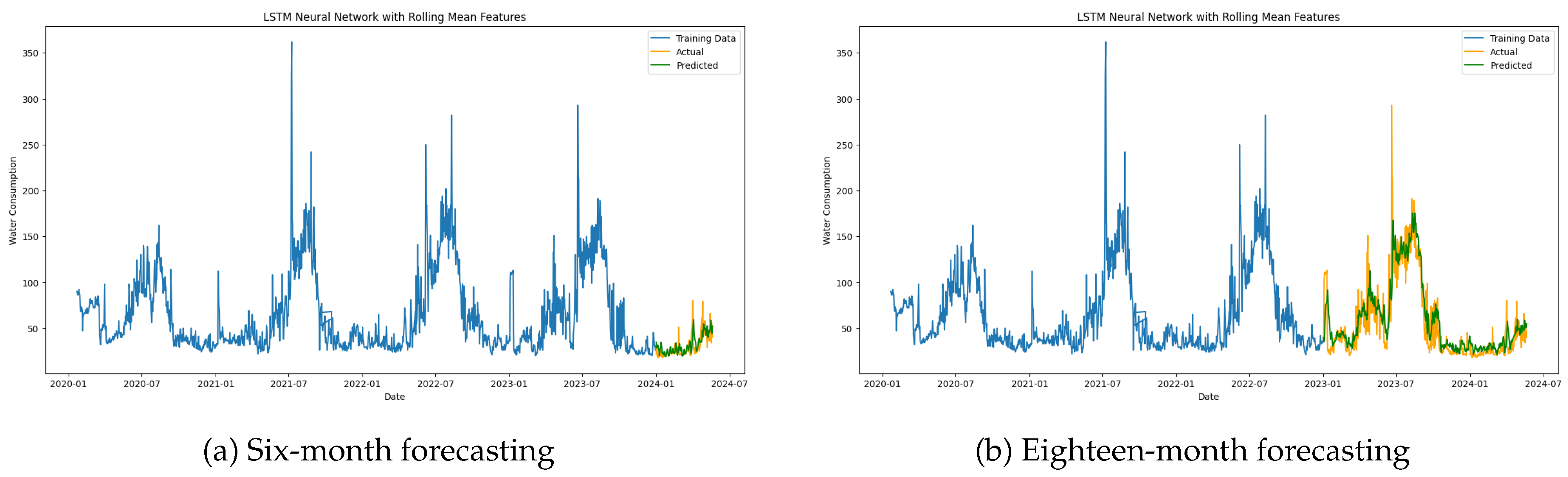

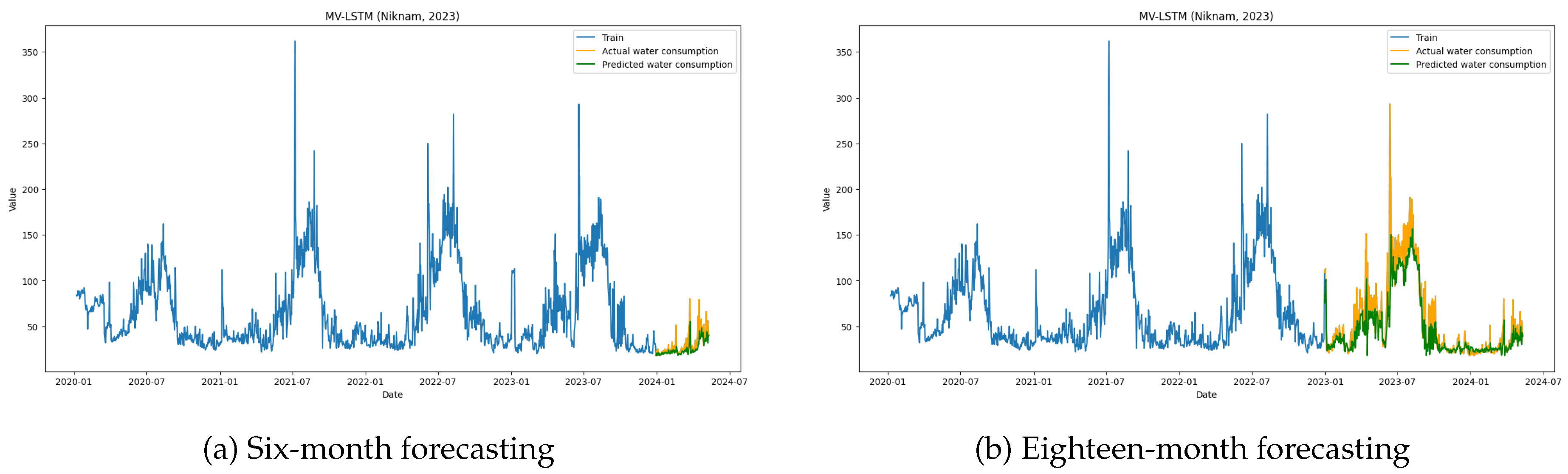

| 6 Months | 18 Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | MAE | RMSE | MAPE | MAE | RMSE | MAPE |

| Prophet Basic | 10.37 | 13.66 | 22.45% | 19.70 | 28.68 | 22.45% |

| Prophet + Seasonality | 12.39 | 14.91 | 22.45% | 24.25 | 35.02 | 22.45% |

| Advanced Prophet | 6.24 | 8.78 | 20.77% | 11.14 | 18.02 | 22.34% |

| Prophet Adv. Engineering | 5.76 | 8.31 | 18.61% | 10.07 | 15.02 | 20.12% |

| XGBoost | 7.02 | 8.74 | 24.93% | 12.34 | 18.50 | 27.49% |

| LightGBM | 5.90 | 8.25 | 19.64% | 11.77 | 18.31 | 24.98% |

| Stacking XGBoost + LightGBM | 6.57 | 8.70 | 22.45% | 12.48 | 18.94 | 27.62% |

| LSTM | 5.96 | 9.38 | 18.64% | 12.63 | 20.66 | 25.61% |

| LSTM + GRU Hybrid | 8.18 | 10.10 | 30.10% | 14.64 | 22.32 | 34.06% |

| LSTM Rolling Mean Features | 7.94 | 10.82 | 27.59% | 12.33 | 20.57 | 24.67% |

| MV-LSTM [70] | 5.91 | 10.03 | 15.48% | 12.30 | 22.53 | 19.30% |

| Dependency | Description |

|---|---|

| (1, 3) | Task 3 depends on Task 1 |

| (2, 4) | Task 4 depends on Task 2 |

| (5, 3) | Task 3 depends on Task 5 |

| Task i | (hrs) | (L) | (kg) | (lat, lon) | (hrs) | MaxPreemptions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 13.2 | (51.5074, -0.1278) | 2 | 0 | Van | 1 |

| 2 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 9.24 | (51.5155, -0.1410) | 3 | 0 | Van | 2 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 15.84 | (51.5237, -0.1585) | 1 | 2 | Small Truck | 1 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 6.6 | (51.5308, -0.1208) | 4 | 0 | Van | 1 |

| 5 | 3.0 | 7.5 | 19.8 | (51.4975, -0.1357) | 5 | 1 | Small Truck | 2 |

| From Task i | To Task j | (hrs) | (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 10 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.7 | 14 |

| 1 | 4 | 0.4 | 8 |

| 1 | 5 | 0.6 | 12 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.6 | 12 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.3 | 6 |

| 2 | 5 | 0.7 | 14 |

| 3 | 4 | 0.8 | 16 |

| 3 | 5 | 0.5 | 10 |

| 4 | 5 | 0.6 | 12 |

| Vehicle Type v | (km/L) | (kg CO2/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Van | 12 | 2.64 |

| Small Truck | 8 | 2.68 |

| From Task i | To Task j | Vehicle | (km) | (L) | (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Van | 10 | ||

| 1 | 3 | Small Truck | 14 | ||

| 1 | 4 | Van | 8 | ||

| 1 | 5 | Small Truck | 12 |

| Metric | Conventional Method | Proposed Model | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Completion Time () | 180.58 hours | 155.24 hours | 14% |

| Delays and Penalties () | 17.5 hours | 13.15 hours | 25% |

| CO2 Emissions () | 660.8 kg | 545.7 kg | 17% |

| Fuel Consumption () | 85.58 Litres | 71.98 Litres | 16% |

| Efficiency and Utilization () | 86.17% | 92.23% | 7% |

| Component | Cybersecurity Measure | Security Standard/Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cybersecurity for Smart Water Meters | ||

| Private Key Encryption | AES-128 encryption for data transmission, with private keys ensuring authorized decryption. | AES-128, LoRaWAN, NB-IoT |

| LoRaWAN and NB-IoT Compatibility | Supports secure, long-range data transmission suitable for rural areas. | LoRaWAN, NB-IoT |

| Data Logging and IP-68 Protection | IP-68 protection and internal datalogger for secure, resilient data storage. | IP-68, Data Integrity |

| Secure Data Transmission via Gateway and ChirpStack Platform | ||

| LoRaWAN Gateway | IP-67 gateway securely transmits encrypted data via MQTT to the cloud. | IP-67, MQTT, Data Integrity |

| ChirpStack Platform Security | ChirpStack manages devices with unique keys, MAC-based authentication, and data validation. | Device Authentication, MAC Address Validation |

| SSL/TLS Protocols | SSL/TLS secures all data transmission between services, ensuring encryption in transit. | SSL/TLS |

| Data Flow, Decryption, and Secure Transmission | ||

| Encrypted Data Transmission | Transmits data in AES-128 encrypted format via MQTT to cloud storage. | AES-128, MQTT, Data Encryption |

| Data Decryption | Decrypted and stored in main and backup databases for integrity and redundancy. | Data Integrity, Redundancy |

| Secure Access, API Integration, and Web Application Security | ||

| API Data Loading | Secure APIs (FastAPI, Django) with HTTPS prevent data interception. | HTTPS, API Security |

| Secure Login Platform | Two-step authentication secures access to platform data. | Two-Step Authentication |

| Password Encryption with Salting | Salting and hashing for secure password and sensitive data storage. | Salting, Hashing, Data Encryption |

| Database Security (PostgreSQL) | Access controls, encryption at rest, and regular audits protect database data. | Data Encryption, Access Control |

| Backup, Data Integrity, and ISO 27001 Compliance | ||

| Backup Protocols | Regular backups ensure data availability and integrity. | Data Backup, ISO 27001 |

| ISO 27001 Compliance | Aligns cybersecurity measures with ISO 27001 standards; regular audits verify compliance. | ISO 27001 |

| Data Privacy Compliance | GDPR-compliant protocols and audits for data privacy. | GDPR, Data Privacy |

| Real-Time Monitoring and Threat Detection | ||

| Zabbix Monitoring | Monitors network and infrastructure performance, detecting anomalies. | Real-Time Monitoring |

| Wazuh for Threat Detection | Detects intrusions and abnormal activity through log analysis. | Threat Detection, Log Analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).