1. Introduction

Non-revenue water (NRW) refers to the volume of water that is distributed from the water plant but is not billed to customers, which is a major challenge for water bodies, especially in developing counties [

1]. NRW is the difference between the total volume of water supplied to a distribution water system (DWS) and the amount invoiced to consumers. It includes physical losses from leaks and infrastructure issues, commercial losses from meter errors and illegal usage, and unbilled approved firefighting and operating costs. [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. These losses cause financial deficits, higher operating costs and infrastructure degradation, which worsens water operations, water shortages, maintenance costs, and service reliability.[

8]

Effective NRW management requires the use of technological advancements, data-informed decision making, and predictive analytics to proactively reduce water losses. Conventional techniques such as manual leak detection and intermittent readings of the meter are inadequate. Contemporary optimization methods utilize advanced measuring infrastructure (AMI), remote leak detection, geographic information systems (GIS), machine learning, and digital twin modeling to improve monitoring, accuracy, and efficiency in water distribution.

Optimization is the process of improving a system, model or process to identify the best possible solution within specified constraints.[

9,

10,

11,

12]In the context of this study, Optimization refers to the process of reducing the volume of water produced but not billed by minimizing leaks, improving the accuracy of meters, and preventing unauthorized consumption, thus improving resource management and revenue collection.[

13][

14]. In 2025, Huang et al.[

13] used spatial clustering and parameter adjustments to optimize leak detection in the water distribution network.

This paper examines current developments in the mitigation of NRW, focusing on innovative optimization methodologies. It emphasizes the importance of smart meters, AI-powered analytics, and real-time monitoring to improve detection precision, minimize reaction durations, and optimize water distribution. It also highlights key areas for future research, highlighting the importance of artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and integrated approaches to water management.

This work was guided by the following research objectives:

To analyze the critical determinants affecting non revenue water (NRW) in the Water Distribution System (WDS).

To evaluate how emerging technologies can optimize the reduction of NRW.

To Identify future research directions for novel NRW optimization strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a review of the literature on the critical determinate influencing NRW, the role of emerging technologies, and future directional research to address NRW challenges.

Section 3 gives an overview on how the study was conducted,

Section 4 presents the results of the study and the analysis. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the article with final observations and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews recent publications on the critical determinants of Non-Revenue Water (NRW) and explores the role of emerging technologies in this context. Highlights the strengths and weaknesses of current research while also identifying future research directions to address the challenges of reducing NRW. ,

2.1. Critical Determinants Affecting NRW in Water Distribution s System (WDS)

Water distribution systems (WDS) face substantial issues due to Non-Revenue Water (NRW), adversely affecting operational efficiency and financial viability. This section highlights the critical determinate that influence NRW, highlighting technical and non technical issues that contribute to water loss.

In a case study of Malaysia’s non revenue water in 2021 [

15] the study employs a multiple linear regression model using data from 212 observations to identify critical parameters influencing NRW, such as the number of connections, the consumption volume and production levels, although the length of connections does not exhibit a significant effect.

case study of Kigali City (2024) [

16], attributes NRW to challenges related to planning, technology, and finance. Ineffective strategic planning and inadequate measurement hindered NRW management. The lack of qualified personnel and technical skills led to inefficiencies that required significant training. Financial constraints hindered investments in NRW reduction. However, enhanced strategic planning and capacity building resulted in 10-12% decrease in NRW.

In another case study conducted in 2024 in general Europe, China, Japan, South Korea and specifically in specific states Malaysia with respect to NRW systems [

17]. The study highlights various factors that influence NRW, underscoring its complexity. Aging infrastructure leads to leaks and operational inefficiencies, whereas socioeconomic factors affect water accessibility, especially for marginalized populations. NRW incurs financial losses for utilities, which limits infrastructure investments. In addition, climate change influences the supply and distribution of water, which requires comprehensive strategies to mitigate NRW. In 2024, Din et al.[

18] conducted a case study in South Korea that demonstrated determinate factors that affect NRW, such as leaks from aging infrastructure, inadequate maintenance, and theft of water through illegal connections. Inaccuracies in the measurement, due to outdated technology and errors in data entry, exacerbate the issue. Moreover, substandard data quality obstructs efficient NRW modeling. These variables highlight the complexity of NRW and the need for new integrated water management strategies.

The research by Işman et al.[

19] highlights key elements that contribute to NRW by evaluating the NRW ratio in water distribution systems. In another case study by Ababas et al. [

20] highlights several critical factors that contribute to NRW in Lahore, Pakistan: Erroneous data on water usage resulting from meter failures, actual losses of 45.4 exceed NRW estimates, increasing water demand, diminishing groundwater levels, increasing energy expenses and inadequate water tariffs.

Dimki et al. [

21] analyzed NRW in 37 water supply systems (WSS) in a case study of Serbia and Montenegro using various indices, including the percentage of NRW, the Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI), and the Technical Indicator of Real Losses (TIRL). Real and apparent losses were found to be significant in the region. After applying the IWA methodology, the study presented its findings, discussed the results, and provided general guidelines for reducing NRW in these water systems.

NgueyimNono et al. [

22] identified key factors that contribute to NRW in the Cameroon urban water system, which represented 53% of the total input volume. The main causes included passive leak control, illegal connections, aging pipes, poor pressure management, and inadequate water metering. To reduce NRW, the study recommends leak detection, pipe replacement, better pressure control, improved metering, and removal of illegal connections.

Elkharbot et al. [

1] in another case study in Egypt examined the length of the network, the number of customers, the pressure, the quantities of water supply, the number of leaks and the repair cost, but regression analysis showed that midnight flow (MNF), NRWb, leaks and repair cost were the most important factors affecting NRW. These operational and infrastructure difficulties have the greatest impact on the final NRW ratio of Egyptian water distribution systems. Aging infrastructure, illegal connections, inadequate metering, and high pressure variations that cause pipe breakdowns were the main drivers of Jordan’s non-revenue water (NRW)[

23].In a case study in Kenya [

5] Unaccounted losses were caused by lack of plans and policies, improper meters, and ineffective calculation of the water balance in Lodwar Water Supply, according to the report. NRW was worsened by pipeline leaks and illegal water theft. The lack of active leakage management, personnel knowledge and training, and consumer participation compounded the situation. The utility encountered inefficiencies without systematic management of the NRW, highlighting the need to create policies, upgrade infrastructure, improve metering, and promote awareness efforts to reduce water losses.

Huang et al. [

13] employed optimization techniques to improve leak detection in water distribution systems (WDS) by adjusting three key determinants. Localization Metrics Weight (LMW), Score Threshold (ST), and Indicator of Detection Priority (IDP). The research relied on spatiotemporal correlation in monitoring data and applied spatial clustering to improve accuracy. By optimizing these determinants, the study yielded efficiency, precision, and effectiveness of leak detection in a full-scale distribution network, reducing water loss, and improving system performance.

Table 1 highlights the critical determinates that influence the NRW observed in the analyzed research cases. Aging infrastructure, leaks, inadequate maintenance, and inability to detect leaks precisely. Technical complications, such ineffective leak detection, metering inaccuracies, and water meter malfunctions, can play a role. In addition, inadequate planning, financial limitations, theft, and illicit connections intensify water losses. Elevated NRW levels are worsened by climate change, groundwater depletion, and increasing water demand.

Further analysis of the research case under review and the proposed solution have not addressed the challenges of NRW, especially for developing counties. The next session explores the role of emerging technologies in NRW optimization strategies.

2.2. The Role of Emerging Technologies to NRW Optimization Strategies

This section explore the role of emerging technology in advanced metering infrastructure (AMI), Remote Leak Detection Technologies,Geographic Information Systems(GIS),Data Analytics and Machine Learning, and Digital Twin Modeling in optimizing NRW.

2.2.1. Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI)

Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI), also known as smart meters, employs automatic fault detection, self-healing capabilities, and bidirectional connectivity to facilitate two-way interactions with customers. The main objective is to collect real-time data for billing, load balancing, and demand response. Due to the presence of sensitive consumer information, it is imperative to maintain confidentiality and integrity to ensure privacy and grid stability. [

24]. AMI utilizes data collectors (DC) to collect, evaluate, and transfer utility usage data to meter data management systems (MDMS) for real-time pricing, billing, outage management, leak detection, demand forecasting, etc. [

25]. Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) facilitates bidirectional real-time communication via smart meters, improving efficiency and reliability for utilities and consumers. This system is susceptible to multiple security threats, such as data theft, misuse of usage reports, impersonation, illegal access, and fake data injection, which may compromise infrastructure and appropriate resources. [

25,

26]

Previous research attempted to solve the issue in AIM. [

24] Created Secure and Reliable AMI Protocol (SRAMI) which improves the data transfer of the AMI of smart grids by considering energy efficiency, geographical distance and bandwidth.It uses lightweight Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) to improve data integrity and privacy while conserving power. SRAMI improves Smart City security and efficiency by outperforming previous protocols in throughput, packet delivery ratio, energy economy, latency, and communication overhead. [

27] developne an intelligent water meters, an Advanced Network Infrastructure created a prediction algorithm. The algorithm cleaned time-series data using outlier detection for accurate predictions. Multifamily water use was predicted using four machine learning and deep learning models. The experimental results showed the efficiency and adaptability of the approach, proving its real-world efficacy.

In a recent case study of Bangladesh in 2025 [

28], smart water meters developed using IoT and machine learning to monitor, bill and conserve water. Mobile app allowed remote monitoring, real-time data transmission, and automated charging. Machine learning maintained solar and AC battery performance and prevented meter manipulation. Water losses, inefficiencies, and income reduction were addressed for flexible, sustainable water management. Lamb [

29] urges US utilities to adopt AMI widely for remote data collection and automation to improve efficiency. As millions of electric, gas, and water meters switch to AMI, utilities must prove their value to regulators. . However, Islam et al.[

25] highlight that the standard AMI is based on trusted third parties (TTP) for the management and authentication of cryptographic keys, which has many problems. This dependency creates a single point of failure and increases network overhead, making the system prone to cyberattacks and inefficiencies. Next, we examine remote leak detection technologies to address NRW. .

The following table summarizes the findings of the recent research reviewed.

2.2.2. Remote Leak Detection Technologies

Leakage in the water distribution system (WDS) results in significant annual water losses, while deteriorating infrastructure allows subterranean breaches to remain undetected for extended periods. Remote leak detection systems identify leaks in water distribution networks without the need for manual inspections. These systems employ sensors, data analytics, and artificial intelligence to quickly identify leaks, thus minimizing water loss and infrastructure damage. Jung et al.[

30] analyze geographically dispersed pressure response images for leak identification using a conventional neural network (CNN). Real-time water use and pressure data from the Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) were compared with twin digital projections (hydraulic model) to find leaks. The pressure sensors on the WDS allowed the model to distinguish normal and leaky conditions. The research evaluated the leak detection performance of the system in distribution-centric networks using recall, precision, and the F1 score. These technologies improve remote water leak detection, reducing water waste and maintenance expenses. Ali et al. [

31] used advanced leak detection and localization employing GIS and infrared technology. Data overlay and analysis on GIS layers identify real-time leaks in flow, pressure, and chlorine residuals. Chlorine analysis detects breaches for specific treatments when both flow and pressure decrease simultaneously. Research supports the use of infrared cameras for leak detection. In a study by Zhang et al. [

32] Leaks from the water distribution system were located using trained graphhs neural networks (GNW) with algorithms. An algorithm-informed GNN (AIGNN) was pre-trained to mimic the Ford-Fulkerson max-flow technique for more generalizable pressure estimates. An AIGNN reconstructs current pressures, while another predicts them from past data. Comparison of model outputs demonstrates leakage.The method outperforms typical GNNs in accuracy and out-of-distribution data generalization in experiments.

Bartkowska et al. [

33] Simulate leakage scenarios, two authentic network models, and hydraulic output data using hydraulic modeling and sensitivity analysis to evaluate a novel methodology. They identified leaks by correlation, Euclidean distance, and cosine similarity. Identification of leak candidates based on similarity and geographic categorization based on density revealed leak hotspots.This helps to detect leakage in remote areas where data and resources are limited.

In reviews of 47 papers by Islam et al. [

34] Analyze trends in machine learning techniques, the Internet of Things, and sensor technologies for leak detection. Vibration, acoustic, and flow sensors are widely utilized for their cost efficiency, but image processing and optical fiber sensors are becoming increasingly popular. Machine learning and threshold-based algorithms dominate detection, facilitated by WiFi, cellular IoT, and LoRa technologies for real-time monitoring.

According to Islam et al. [

34] These innovations improve early leak detection, reduce water loss, and increase infrastructure sustainability.However, [

25] emphasizes that conventional leak detection technologies frequently exhibit inaccurate localization and elevated false alarm rates, especially during transient occurrences. Traditional methods are inadequate for real-time data processing and lack the sophisticated signal processing and artificial intelligence skills required for the precise assessment and localization of leak magnitude. The research carried out in 2025 by Huang et al. [

13] used spatio-temporal correlation of monitoring data to locate leaks. To pinpoint leaks in a comprehensive water distribution network, the research refines three key determinants. Localization Metrics Weight (LMW), Score Threshold (ST), and Indicator of Detection Priority (IDP). However, the method has many flaws. It is sensitive to sensor noise and requires broad spatio-temporal high-quality data, making it prone to errors in complex water distribution systems. In dynamic operations , the approach demands precise determinant calibration, which is difficult to maintain. Zhang et al.[

32] revealed that the algorithm informed by graph neural networks (GNN) is limited. Although the algorithms improve accuracy and robustness within the training data distribution, they struggle to maintain performance when applied outside of it. This generalization gap restricts their effectiveness in real-world water distribution networks.[

35] successfully developed an early warning system using digital water meters installed on customer sites to monitor household water use at 15 minute intervals detected and localized leaks. However, The solution used data-based detection and model-based localization despite cellular data loss and GDPR consumer refusals.

The

table below summarizes the cases studied regarding the approach. The following section will explore the role of GIS in optimizing Non-Revenue Water (NRW).

2.2.3. Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

This section explores the critical role of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in addressing NRW challenges. GIS facilitates thorough mapping and analysis of water distribution systems, enabling utilities to pinpoint high-loss regions and improve maintenance approaches. GIS improves operational efficiency and financial sustainability by integrating real-time sensor data with prediction models to facilitate targeted interventions.

A case study in Tanzania, Zahor et al. [

36],GIS was used to map and quantify daily water consumption and NRW levels in the Sumbawanga Urban District. A geodatabase was developed using QGIS, Postgres, and PostGIS to improve maintenance and budgeting, proving that GIS-based monitoring is better than auditing. Real-time leak detection and pipeline optimization using GIS could minimize NRW and enhance water supply efficiency. Mirshafiei et al. [

37] A web-based GIS system optimizes valve closures during events to manage urban water leakage. Pipelines are isolated immediately using GIS web services, improving reaction time. The Web 2.0-based interactive spatial data management system was tested in the Tehran water network using C# and ArcGIS SDK, providing precision and practical viability.

In the same context,Ayad et al. [

38]An integrated methodology was established for the calibration of water pipe networks and the quantification of leaks through the amalgamation of field measurement and mathematical modeling. The model used evolutionary methods, such as genetic algorithms (GA) and shuffled complex evolution (SCE-UA), to detect leak outflows and malfunctioning meters. The network was calibrated using EPAnet by assessing physical losses and pipe roughness coefficients. This approach, employing floating-point representations and adaptive constraint management, demonstrated significant accuracy and efficiency in both theoretical (Hanoi) and practical (Faisal City) networks, integrating GIS for data input and visualization.

In a case study in Egypt Yehia et al.[

39], GIS integrated geographic data for leak detection, meter placement, and pipeline surveillance. This enabled mapping of the water distribution network, identification of high-loss areas, and visualization of illegal connections. GIS combined with billing systems and customer databases helps utilities track water use and distribute resources. GIS helps field operations reduce NRW through pressure control and timely repairs. Data discrepancies, lack of standards, and limited real-time capabilities hinder its deployment and efficacy.capability[

40,

41]

The

table below summarizes the cases studied regarding the approach. The following section will explore data analytics and machine learning in optimizing NRW.

2.2.4. Data Analytics and Machine Learning

Data Analytics and Machine Learning for NRW provide innovative solutions to address ongoing water loss issues in water distribution systems. This section analyses the progressive use of sophisticated analytical methodologies and predictive modeling to optimize reduction of Non-Revenue Water. Using historical data, sensor networks, and advanced algorithms, stakeholders can discern essential patterns and reasons that lead to water loss. The implementation of these strategies improves operational efficiency and facilitates strategic decision making for sustainable water management practices.

In the case study by Elkharbot et al. [

1] An artificial neural network (ANN) was used to analyze historical data from 92 Egyptian metered districts to address Non-Revenue Water (NRW). After eliminating outliers with Z-score standardization, statistical analysis identified significant characteristics such as night traffic and repair expenses. Four feedforward ANN models outperformed regression in predicting accuracy. Due to data availability, overfitting, and limited generalization to diverse network conditions, the model may not work well in different water distribution patterns.

Fares et al. [

42] The research employed acoustics, signal processing, and machine learning to identify leaks using ten real-time acoustic emission techniques on wireless noise recorders. Deep Learning and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) proficiently detected unlabeled leaks. Although acoustics and machine learning are proficient in leak identification, the study’s applicability is confined to Hong Kong’s water distribution system, and the quality of acoustic data influences model effectiveness. Real-time monitoring and machine learning-driven predictive analytics improve NRW management; yet, issues with data quality, computational complexity, and ethical considerations remain.

The use of data analytics and machine learning to address NRW has several drawbacks. Limited access to high-quality historical data can hinder model effectiveness and the risk of overfitting restricts the applicability of artificial neural networks to various distribution patterns.Data quality issues, including noise and errors, can lead to inaccurate conclusions, while the computational complexity of these methods often requires substantial resources. Ethical concerns about data protection and governance also hinder the implementation of data-driven solutions. The next section explores the adoption of digital twin modeling.

2.2.5. Digital Twin Modeling

Digital Twin (DT) is a real-time digital replica of a physical system that uses IoT, AI, and advanced simulations to revolutionize decision making and system optimization in industries, promising trans formative change[

43].This section covers Digital Twin Modeling and its transformative effect on water distribution management. Digital twins build dynamic virtual models of water networks utilizing real-time sensor data, IoT, and complex simulations to simulate operational behavior. This method improves system resilience and sustainability through proactive supervision, anticipatory maintenance, and better decision making [

44].

In a Singapore case study, Wu et al.[

44] introduced a framework for building high-fidelity digital twins (DT) for smart water grids. It shows how a digital thread, data-driven models, physics-based simulations, and visualization tools can improve the monitoring and management of the real-time water distribution network. DT models are trained and calibrated with sensor data to provide diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive information to improve decision making. The framework was shown to detect and localize anomaly events accurately and quickly, such as pipe bursts and illicit water use.

To address NRW in the Gaula Water Distribution Network in Madeira, Portugal, Ramos et al.[

45] established a Smart Water Grid (SWG) with a Digital Twin (DT). DT enables live monitoring of critical system determinants such as pressures, valve operations, and head loss factors, facilitating scenario analysis and network requalification. As a result, the approach achieved a significant reduction in real water losses - saving approximately 434,273 m3 (about 80% of losses) - and generated economic savings of around EUR 165k, with only 40% of the annual water volume needed to meet demand. Furthermore, the high value of the infrastructure leakage index of 21.15 underscores the substantial potential for further improvements in system efficiency.

Successful case study of Digital Twin (DT) for Valencia, Spain’s water distribution system. conejos et al. [

46] developed DTs for a water utility by establishing essential needs and using an ongoing process of learning and modifications to support daily operations in a 1.6 million-person metropolitan area. The viability and advantages of DTs in improving management and decision making in smart cities are demonstrated by this innovative endeavor.

According to Homaei et al.[

47], Digital Twin Modeling provides a cutting-edge platform for water distribution systems that uses IoT, AI and ML models to predict water consumption and optimize maintenance scheduling. However, according to Mihai et al. [

43] Digital Twins’ main drawbacks are data communication and accumulation complexity, insufficient training data for robust ML models, and high computational requirements for high-fidelity replicas.In addition, issues related to interoperability, standardization, and scalability remain critical obstacles to widespread industrial adoption. DTs also face substantial privacy and security concerns [

48].

The future of digital twins depends on integrating technologies such as IoT, AI, 3D models, next-generation mobile communications (5G/6G),Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR) distributed computing, transfer learning, and electronic sensors [

43].

Future research should focus on creating frameworks that address these deficiencies while optimizing sophisticated technology to successfully decrease Non-Revenue Water. The next section explores future directional research to solve the problem. challenge of reducing NRW.

Table 5.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Emerging Technologies

Table 5.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Emerging Technologies

| Technology |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

| Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) |

- Real-time data collection for timely billing and demand management. |

Vulnerable to cybersecurity threats (hacking, data breaches). |

| |

- Bidirectional communication enhances customer engagement. |

Dependence on third-party vendors can lead to vulnerabilities. |

| |

- Automatic fault detection improves system reliability. |

Signal interference can impact measuring accuracy in certain environments. |

| Remote Leak Detection Technologies |

- Fast detection of leaks reduces operational water loss. |

- Performance is sensitive to the quality and precision of sensors |

| |

- Enhances data-driven decision-making through analytics. |

High false positive rates can lead to unnecessary maintenance actions. |

| |

- Decreases maintenance costs by enabling early repairs. |

- Integration with existing systems can be technically challenging |

| Geographic Information Systems (GIS) |

- Advanced mapping for identifying high-loss regions. |

Reliance on accurate and current data can lead to flawed analyses if data is poor. |

| |

- Enhances planning and resource allocation efficiencies. |

Implementation costs can be high, especially for smaller utilities. |

| |

- Supports real-time data integration for predictive assessments. |

Requires significant training and expertise for effective usage. |

| |

|

Limited capacity for real-time processing without robust infrastructure in place. |

| Data Analytics and Machine Learning |

- Reveals insights and patterns for effective water management. |

- Access to quality historical data is often limited, affecting model training. |

| |

- Predictive capabilities improve response times to water system issues. |

- Overfitting may reduce the model’s effectiveness when applied to new data. |

| |

- Automates routine analyses, thereby increasing operational efficiency |

- High computational requirements can necessitate advanced hardware |

| |

|

Ethical considerations regarding data privacy can restrict usage and implementation. |

| Digital Twin Modeling |

- Provides a dynamic representation of water systems for enhanced monitoring. |

Complex to set up and maintain due to extensive data integration needs. |

| |

- Facilitates simulation and scenario planning to optimize performance. |

High computational demands may limit real-time monitoring capabilities. |

| |

- Combines data from multiple sources for comprehensive insights |

Effectiveness heavily depends on the fidelity and accuracy of input data. |

| |

|

Data privacy concerns arise when handling sensitive operational information. |

2.3. Future Research Directions for Novel NRW Optimization Strategies

This section examines future direction research that will address the optimization of NRW. Whether it be the introduction of Smart meters, AI-driven anomaly detection, and blockchain billing, the accuracy of the meter improves and prevents fraud in commercial losses. IoT-enabled hydrants, GIS monitoring, and automated tracking enhance accountability for authorized non billing water [

49] Examine the potential of Generative AI to improve resilience, efficiency, and decision-making in water distribution systems (WDS) to improve water bodies’ operations. The study emphasizes the strength of generative AI in processing massive datasets, finding patterns and providing information, but usability, accessibility, and training ability hinder adoption.Generational AI makes AI more accessible to water utilities by offering intuitive, natural language interactions with complex systems. The report explores AI applications such as missing data imputation, asset data processing, and water demand analysis, as well as obstacles such as responsible AI adoption, trust building, workflow integration, data protection, and security. Stresses collaboration for AI-driven water system research.

Figueiredo et al. [

50] presented the Water Wise System (W2S), a digital water solution that optimizes the urban water cycle in growing peri-urban areas, increasing water demand, and water shortages related to climate change. Blends IoT, SCADA, GIS, and EPANET with powerful Machine Learning and Deep Learning algorithms for real-time monitoring and decision support. Effective water supply network management and optimization of the water-energy nexus are the objectives of this integration. The study describes the architecture framework of W2S and its potential to transform smart city water management.

In 2022,Islam et al.[

25] introduced a blockchain-based AMI security framework that uses smart contracts and the implemented practical Byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT) algorithm within the Hyper ledger Fabric to eliminate third-party vulnerabilities. The results indicate improved efficiency and security against cyber threats, accompanied by reduced communication and time expenditures.

Another research by Krishnan et al. [

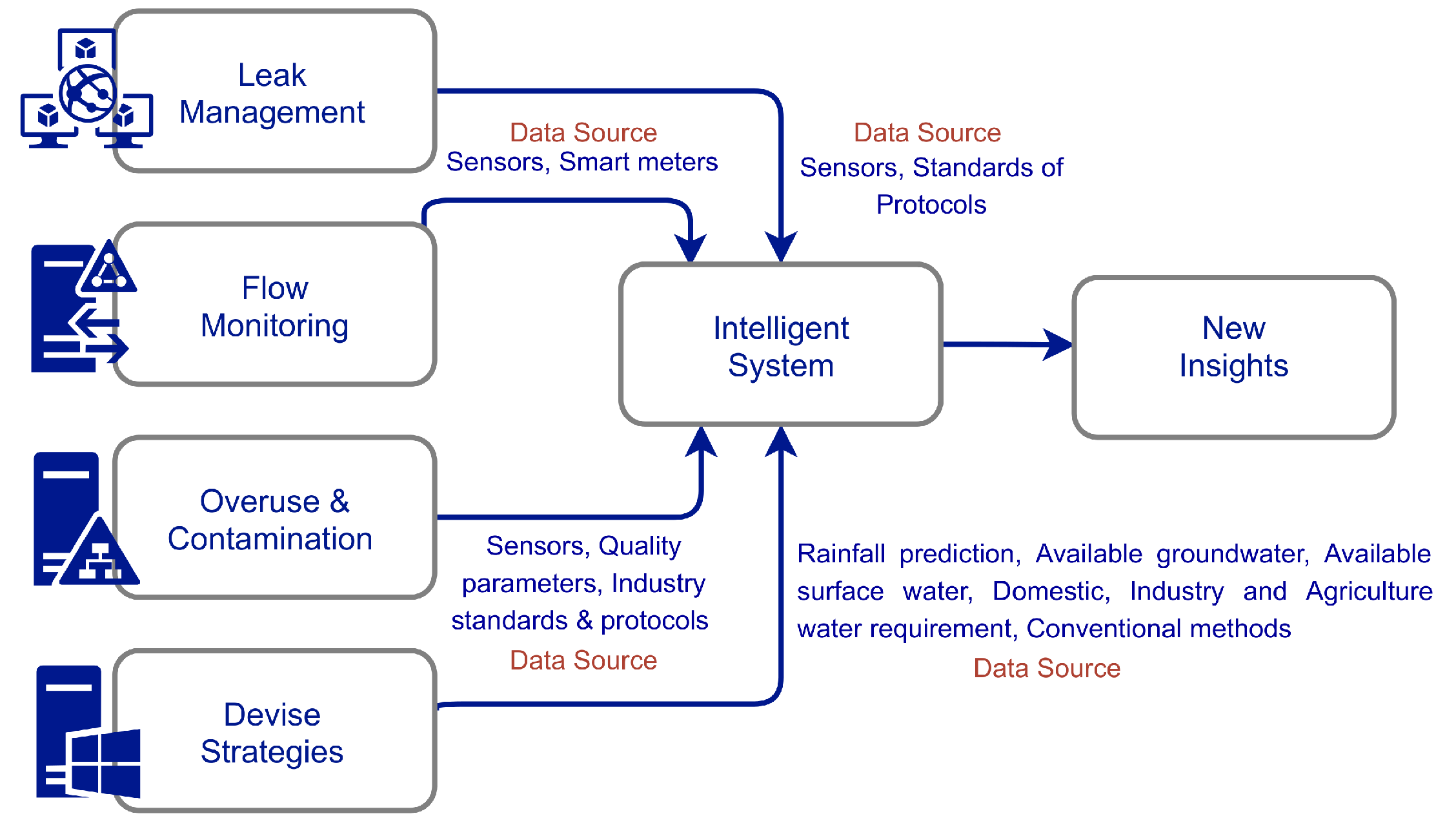

51] successfully developed intelligent systems for water management that aggregate data from various water management domains, such as leak detection, flow monitoring, contamination control, and strategic planning, to produce actionable insights. By gathering sensor input and applying relevant standards and protocols, the system allows real-time decision making, improved resource allocation, and improved water network efficiency.

Figure 1. Shows an advanced water management system that addresses non revenue water (NRW) through the integration of various data sources to improve decision making. Integrates leak control by employing sensors and smart meters for leak detection, with flow monitoring that guarantees real-time tracking via defined protocols. In addition, it tackles overuse and contamination by using high-quality sensors and adhering to industry standards to detect excessive use and potential contamination hazards. The system improves the formulation of the plan by evaluating rainfall forecasts, groundwater resources, and sectoral water requirements. Diverse data sources are integrated into an intelligent system that processes and analyzes them to produce new insights, facilitating predictive analytics and real-time monitoring. This method improves efficiency, minimizes water loss, and fosters sustainable water resource management.

3. Research Methodology

This study utilized a systematic literature review methodology to examine techniques for optimizing Non-Revenue Water (NRW). Data were collected through searches on the Internet in academic databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, PubMed, and the International Water Association. The review of the articles concentrated on recent research on NRW Optimization from 2019 to current in the reduction of non-revenue water (NRW), encompassing advanced metering infrastructure (AMI), remote leak detection, geographic information systems (GIS), data analysis, machine learning, and digital twin modeling. The chosen articles were rigorously evaluated for their techniques, results, strengths and weaknesses, and relevance to NRW management.

4. Results and Discussion

The study findings address research questions: What are the critical determinants affecting non-revenue water (NRW)? What is the role of emerging technologies in reducing NRW?, and what are the future research directions for optimization strategies?

This study highlights the major challenges presented by Non-Revenue Water (NRW) in water distribution systems (WDS), focusing on critical determinants, including aging infrastructure, illegal connections, metering errors, inadequate maintenance and socioeconomic influences. The findings suggest that NRW is a complex issue that requires integrated solutions that incorporate both technological and non-technical strategies.

Significant research from Malaysia, Egypt, and South Korea shows that the quality of infrastructure and operational conditions profoundly affect NRW levels due to leaks and illicit use. The deployment of sophisticated technology such as smart meters and Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) has demonstrated efficacy in augmenting real-time data acquisition, improving leak identification, and optimizing billing procedures. Furthermore, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) enabled precise interventions by delineating areas with significant losses.

Twin digital technologies augment system oversight, facilitating predictive maintenance and scenario analysis. Addressing NRW requires a comprehensive approach that combines measures of technological, regulatory, and community engagement. There is an urgent need for improved training for utility personnel and increased public awareness of water consumption.

Financial limitations in emerging nations impede essential infrastructure improvements, underscoring the need for priority support from politicians. Subsequent research should focus on pioneering alternatives, such as blockchain for secure invoicing and generative AI for instantaneous decision making. As climate change compounds water distribution issues, the implementation of sustainable practices will be essential to improve infrastructure resilience.

The study emphasizes the importance of collaborative and innovative solutions in the effective management of NRW, merging contemporary technologies with traditional practices to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and guarantee fair access to water resources.

5. Conclusions

The emphasis on advancing research in optimization strategies is essential to effectively address the ongoing challenges of reducing Non-Revenue Water (NRW) levels in water bodies worldwide. The determinate influencing the NRW need to be addressed using the advancement and integration of emerging technologies. The integration of IoT devices facilitates the acquisition of real-time sensor data, whereas sophisticated electronic sensors deliver accurate readings. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins facilitate predictive analytics and simulation of water networks, helping to identify concerns prior to their escalation. Three-dimensional modeling, augmented reality, and virtual reality augment visualization and training for maintenance teams, while next-generation mobile communications (5G/6G) expand connectivity throughout the network. Moreover, distributed and edge computing enhance data processing, while transfer learning and Big Data Analytics enable intricate pattern detection and informed decision-making. Blockchain facilitates secure and transparent data sharing, while GIS provides essential geographical analysis; collectively, these technologies constitute a holistic strategy to address the operational inefficiencies that impede effective NRW management.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| AHP |

Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| ECC |

Elliptic Curve Cryptography |

| PBFT |

Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| CHW |

Hazen-Williams coefficient |

| DT |

Digital Twins |

| EA |

Evolutionary Algorithms |

| EPAnet |

Environmental Protection Agency Network Evaluation Tool |

| NRW |

Non Revenue Water |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithms |

| GIS |

Geographic Information Systems |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| IWA |

International Water Association |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MDMS |

Meter Data Management Systems |

| WDS |

Water Distribution System |

| WSSs |

Water Supply Systems |

| TIRLs |

Technical Indicator of Real Losses |

| SCE-UA |

Shuffled Complex Evolution - University of Arizona |

| SRAMI |

secure and reliable AMI protocol |

| SM |

Smart Grid |

| ILI |

Infrastructure Leakage Index |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| W2S |

Water Wise System |

| SWG |

Smart Water Grid |

| SCADA |

Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition |

| PDR |

Packet Delivery Ratio |

| WSN |

Wireless Sensor Network |

References

- Elkharbotly, M.R.; Seddik, M.; Khalifa, A. Toward sustainable water: prediction of non-revenue water via artificial neural network and multiple linear regression modelling approach in Egypt. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2022, 13, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E. Beyond Leakage: Non-Revenue Water Loss and Economic Sustainability. Urban Science 2024, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, M.S. Non-Revenue Water: Methodological Comparative Assessment. Ph.D thesis, Khalifa University of Science, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.Y. Reducing Non-Revenue Water. International Journal of Applied Mathematics, Computational Science and Systems Engineering 2024, 6, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keya, A.M. Evaluation of Non-revenue Water Management: a Case Study of Lodwar Water Supply in Lodwar Municipality, Kenya. PhD thesis, University of Nairobi, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CHEA, E.N. ASSESSING NON-REVENUE WATER REDUCTION STRATEGIES BY WATER SERVICE PROVIDERS IN KENYA. PhD thesis, Pwani University, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mubvaruri, F.; Hoko, Z.; Mhizha, A.; Gumindoga, W. Investigating trends and components of non-revenue water for Glendale, Zimbabwe. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 2022, 126, 103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, W.S.D.; Ratnasooriya, A.H.R.; Abeykoon, H. Non-Revenue Water Reduction Strategies for an Urban Water Supply Scheme: A Case Study for Gampaha Water Supply Scheme. In Proceedings of the 2023 Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference (MERCon); 2023; pp. 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tole, K.; Moqa, R.; Zheng, J.; He, K. A simulated annealing approach for the circle bin packing problem with rectangular items. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 176, 109004. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Tole, K.; Ni, F.; Yuan, Y.; Liao, L. Adaptive large neighborhood search for solving the circle bin packing problem. Computers & Operations Research 2021, 127, 105140. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Tole, K.; Ni, F.; He, K.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, J. Adaptive simulated annealing with greedy search for the circle bin packing problem. Computers & Operations Research 2022, 144, 105826. [Google Scholar]

- Karema, M.; Mwakondo, F.; Tole, K.T. A Three-Phase Novel Angular Perturbation Technique for Metaheuristic-Based School Bus Routing Optimization, 2024.

- Huang, W.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhan, J.; Yang, H.; Li, X. Parameter Analysis and Optimization of a Leakage Localization Method Based on Spatial Clustering. Water (20734441) 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuEltayef, H.T.; AbuAlhin, K.S.; Alastal, K.M. Addressing non-revenue water as a global problem and its interlinkages with sustainable development goals. Water Practice & Technology 2023, 18, 3175–3202. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Malek, H.; Zakaria, M.H.; Zulkifli, M.L.; Roslan, N.F. Determinants of non-revenue water. Malaysian Journal of Computing (MJoC) 2021, 6, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, R.; Tsutsui, N.; Bahige, J.B.; Murakami, S. Cost-effective non-revenue water reduction: analysis through pilot activities in Kigali City, Rwanda. Water Practice & Technology 2024, 19, 4328–4337. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, W.A.N.W.; Din, R.; Na’in, N.M.; Farid, N.F.N.M. NON-REVENUE WATER: IDENTIFYING CHALLENGES AND ANTICIPATING FUTURE SOLUTIONS. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Environment Management 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, R.; Na’in, N.M.; Utama, S.; Hadi, M.; Almaliki, A.J.Q. Innovative Machine Learning Applications in Non-Revenue Water Management: Challenges and Future Solution. Semarak International Journal of Machine Learning 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şişman, E.; Kizilöz, B. Artificial neural network system analysis and Kriging methodology for estimation of non-revenue water ratio. Water supply 2020, 20, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Kazama, S.; Takizawa, S. Water Demand Estimation in Service Areas with Limited Numbers of Customer Meters—Case Study in Water and Sanitation Agency (WASA) Lahore, Pakistan. Water 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkić, D.; Babalj, M.; Kovac, D.; Papović, M. Non-Revenue Water in Water Supply Systems of Serbia and Montenegro. EWaS5 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nono, K.J.N.; Mvongo, V.D.; Defo, C. Assessment of non-revenue water in the urban water distribution system network in Cameroon (Central Africa). Water Supply 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qtaishat, K.S. Reducing non revenue water in Jordan using GIS. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2020); SPIE, 2020; Volume 11524, pp. 351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, P.D.; Shiyamala, S. Secure advance metering infrastructure protocol for smart grid power system enabled by the Internet of Things. Microprocessors and Microsystems 2022, 95, 104708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Rahman, M.S.; Mahmud, I.; Sifat, M.N.A.; Cho, Y.Z. A blockchain-enabled distributed advanced metering infrastructure secure communication (BC-AMI). Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokry, M.; Awad, A.I.; Abd-Ellah, M.K.; Khalaf, A.A. Systematic survey of advanced metering infrastructure security: Vulnerabilities, attacks, countermeasures, and future vision. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 136, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saganowski,.; Andrysiak, T. Prediction of Water Usage for Advanced Metering Infrastructure Network with Intelligent Water Meters. In Proceedings of the Computational Intelligence in Security for Information Systems Conference; Springer, 2023; pp. 122–131.

- Mahin, M.I.S.; Arefin, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Eva, A.J.; Hossain, I. A Conceptual Model for Smart Water Metering in Bangladesh: Transitioning from Traditional Systems To Digitalization. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M. Advanced Metering Infrastructure: Continued Evolution and Opportunities to Deliver Greater Value. Climate and Energy 2025, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.; Jung, D. Exploration of Deep Learning Leak Detection Model across Multiple Smart Water Distribution Systems: Detectable Leak Sizes with AMI Meters. Water Research X 2025, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hassani, R.; Ali, T.; Mortula, M.M.; Gawai, R. An integrated approach to leak detection in water distribution networks (WDNs) Using GIS and remote sensing. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fink, O. Algorithm-Informed Graph Neural Networks for Leakage Detection and Localization in Water Distribution Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.02797. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowska, I.; Łukasz, W.; Zajkowski, A.; Tuz, P. Comparative Analysis of Leak Detection Methods Using Hydraulic Modelling and Sensitivity Analysis in Rural and Urban–Rural Areas. Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Azam, S.; Shanmugam, B.; Mathur, D. A review on current technologies and future direction of water leakage detection in water distribution network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 107177–107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberascher, M.; Maussner, C.; Hinteregger, P.; Knapp, J.; Halm, A.; Kaiser, M.; Gruber, W.; Truppe, D.; Eggeling, E.; Sitzenfrei, R. Using digitalisation for a real-word implementation of an early warning system for water leakages. Water Practice & Technology 2025, 20, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zahor, Z.; Mromba, C. GIS-Integrated Approach for Non-Revenue Water Reduction in Sumbawanga Urban District, Tanzania. JOURNAL OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL ASSOCIATION OF TANZANIA 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiei, P.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Shakeri, M.; Choi, S.M. Geospatial Information System-Based Modeling Approach for Leakage Management in Urban Water Distribution Networks. Water 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, A.; Khalifa, A.; Fawy, M.E.; Moawad, A. An integrated approach for non-revenue water reduction in water distribution networks based on field activities, optimisation, and GIS applications. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2021, 12, 3509–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, A.F.N. Title of the article. Journal Name 2023, Volume Number, Page Range. [Google Scholar]

- Attah, R.U.; Gil-Ozoudeh, I.; Garba, B.; Iwuanyanwu, O. Leveraging geographic information systems and data analytics for enhanced public sector decision-making and urban planning. Magna Sci Adv Res Rev 2024, 12, 152–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.; Gasmalla, O.; Elmahal, A.; Ganawa, E. Distributed Geospatial Information Systems Challenges and Opportunities. Exploring Remote Sensing-Methods and Applications 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fares, A.; Tijani, I.; Rui, Z.; Zayed, T. Leak detection in real water distribution networks based on acoustic emission and machine learning. Environmental Technology 2023, 44, 3850–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Hung, D.V.; Davis, W.; Towakel, P.; Raza, M.; Karamanoglu, M.; Barn, B.; Shetve, D.; Prasad, R.V.; et al. Digital twins: A survey on enabling technologies, challenges, trends and future prospects. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2022, 24, 2255–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Chew, A.; Meng, X.; Cai, J.; Pok, J.; Kalfarisi, R.; Lai, K.C.; Hew, S.F.; Wong, J.J. High fidelity digital twin-based anomaly detection and localization for smart water grid operation management. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 91, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.; Kuriqi, A.; Besharat, M.; Creaco, E.; Tasca, E.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; Pienika, R.; Iglesias-Rey, P. Smart water grids and digital twin for the management of system efficiency in water distribution networks. Water 2023, 15, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejos Fuertes, P.; Martínez Alzamora, F.; Hervás Carot, M.; Alonso Campos, J. Building and exploiting a Digital Twin for the management of drinking water distribution networks. Urban Water Journal 2020, 17, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaei, M.; Di Bartolo, A.J.; Ávila, M.; Mogollón-Gutiérrez, Ó.; Caro, A. Digital Transformation in the Water Distribution System based on the Digital Twins Concept. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.06694. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zami, M.B.; Shaon, S.; Quy, V.K.; Nguyen, D.C. Digital Twin in Industries: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sela, L.; Sowby, R.B.; Salomons, E.; Housh, M. Making waves: The potential of generative AI in water utility operations. Water Research 2025, 272, 122935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, I.; Esteves, P.; Cabrita, P. Water wise–a digital water solution for smart cities and water management entities. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 181, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.R.; Nallakaruppan, M.; Chengoden, R.; Koppu, S.; Iyapparaja, M.; Sadhasivam, J.; Sethuraman, S. Smart water resource management using Artificial Intelligence—A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).