Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

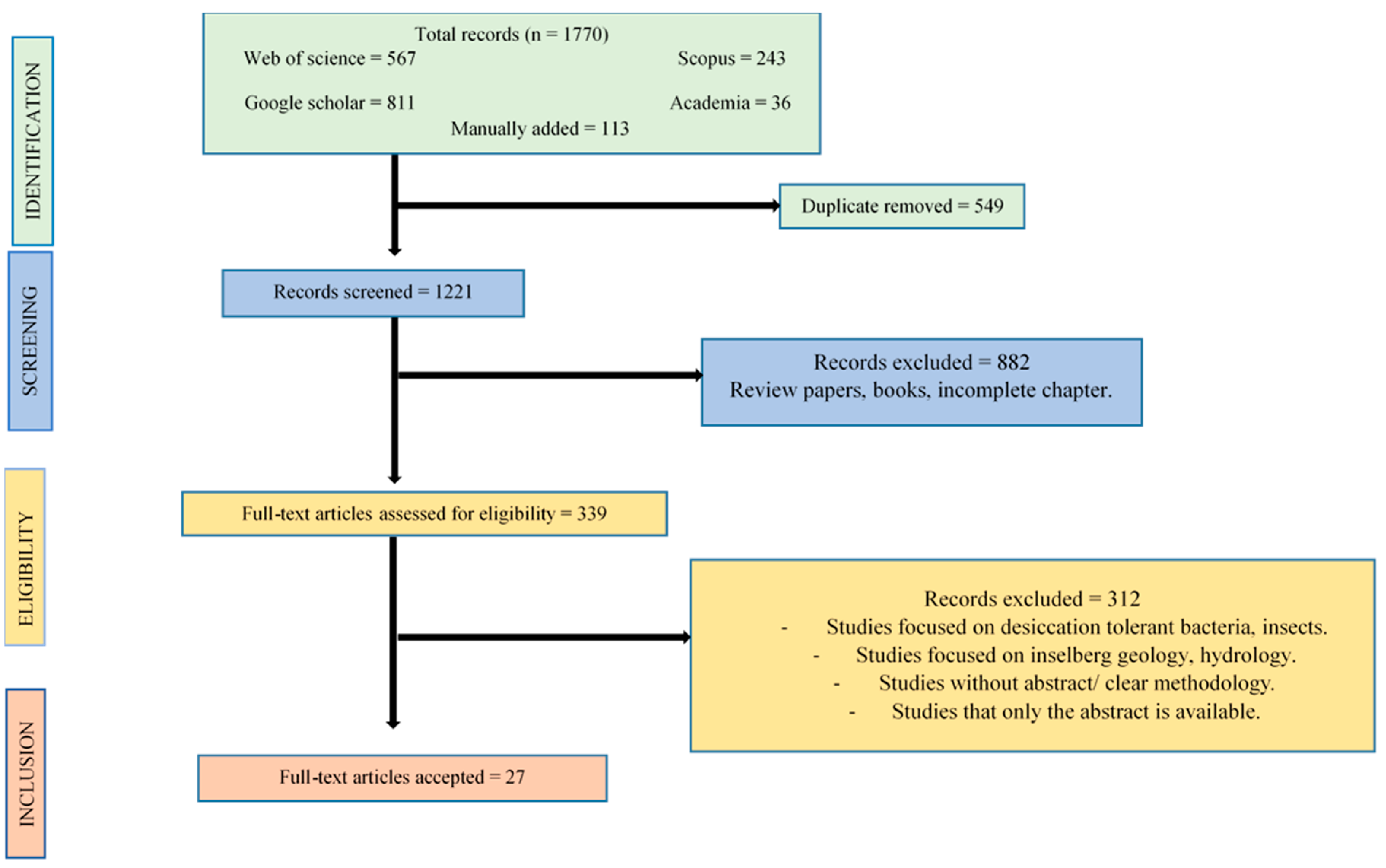

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

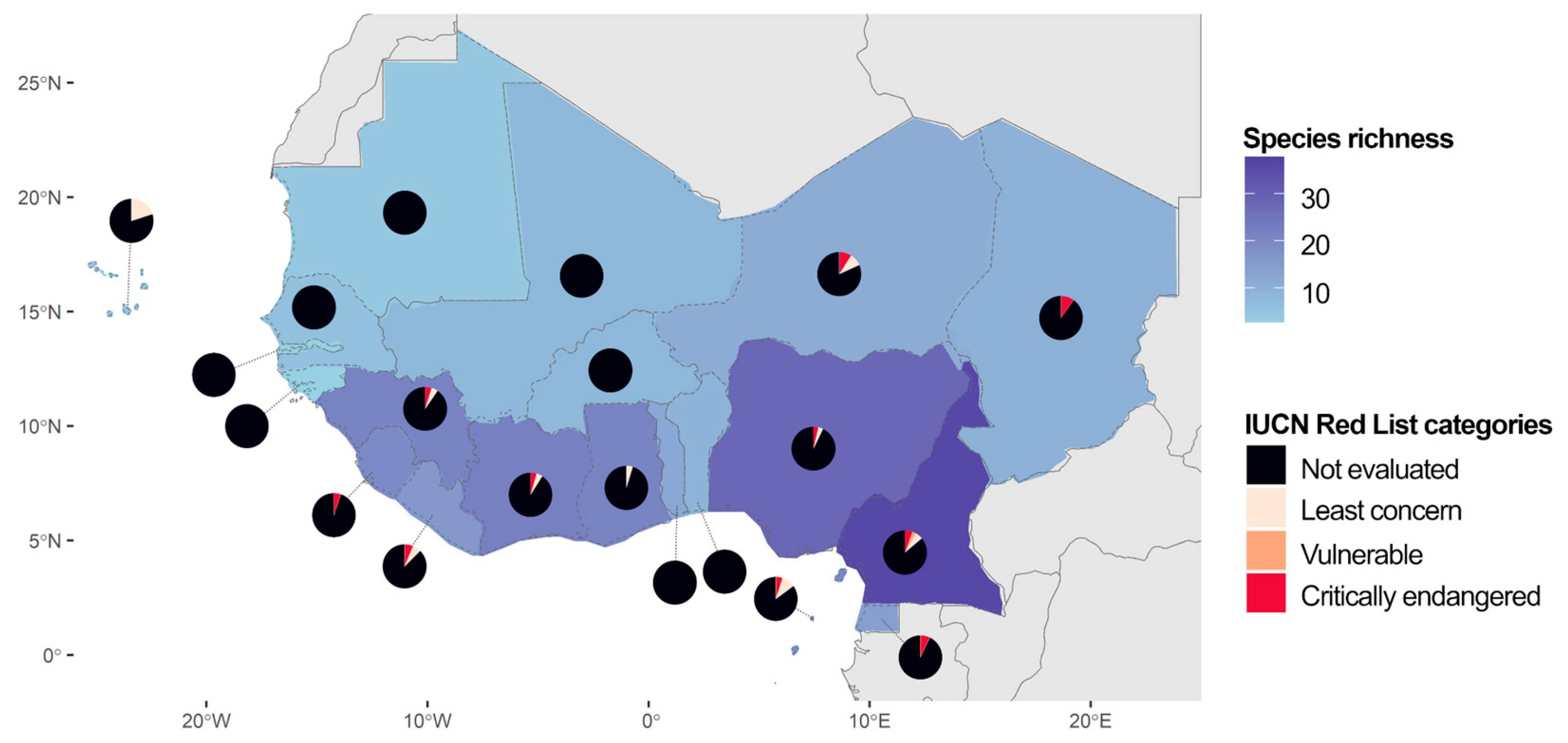

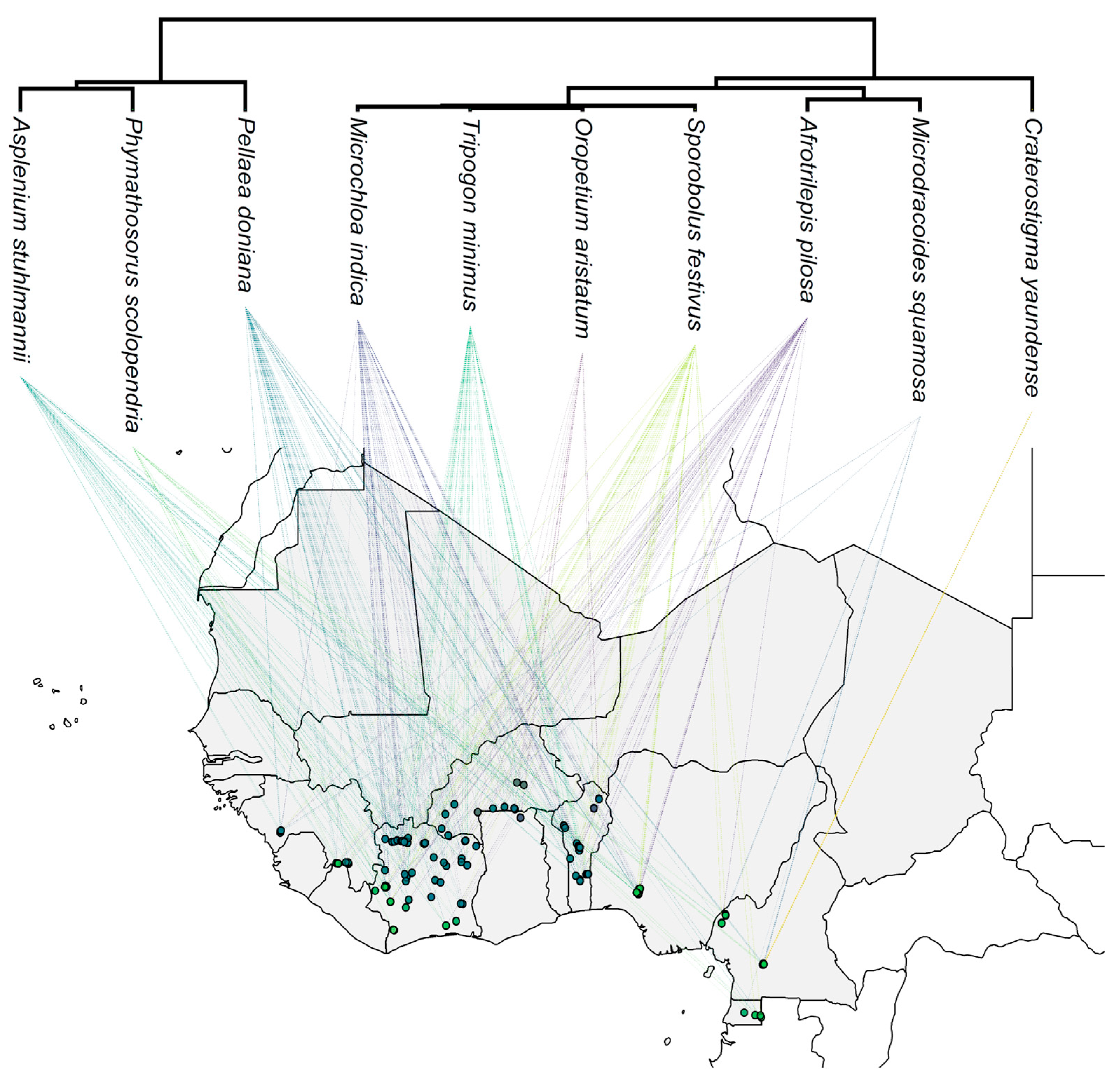

2.1. Diversity, Distribution, and Conservation of DT Plants in West Africa

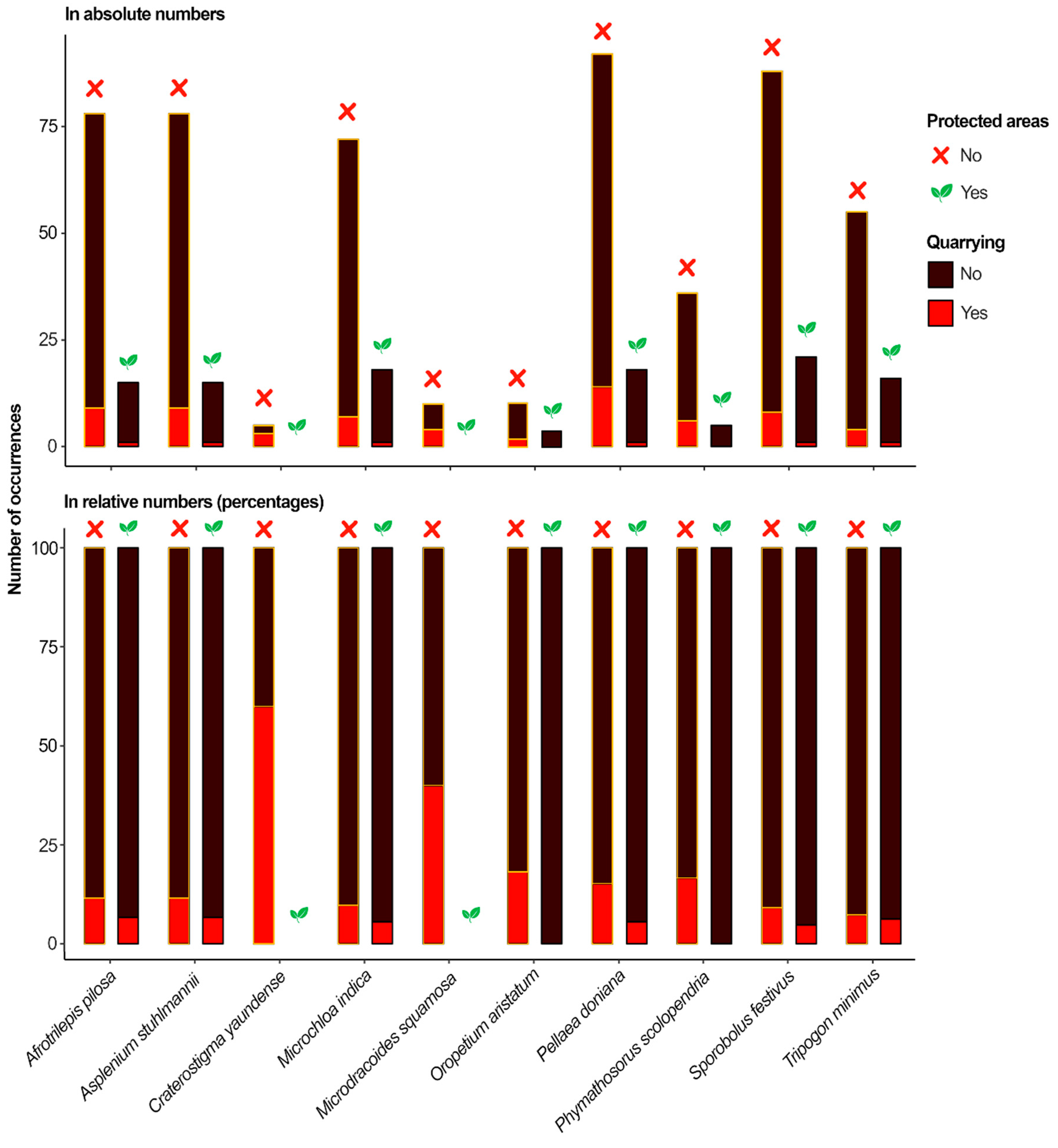

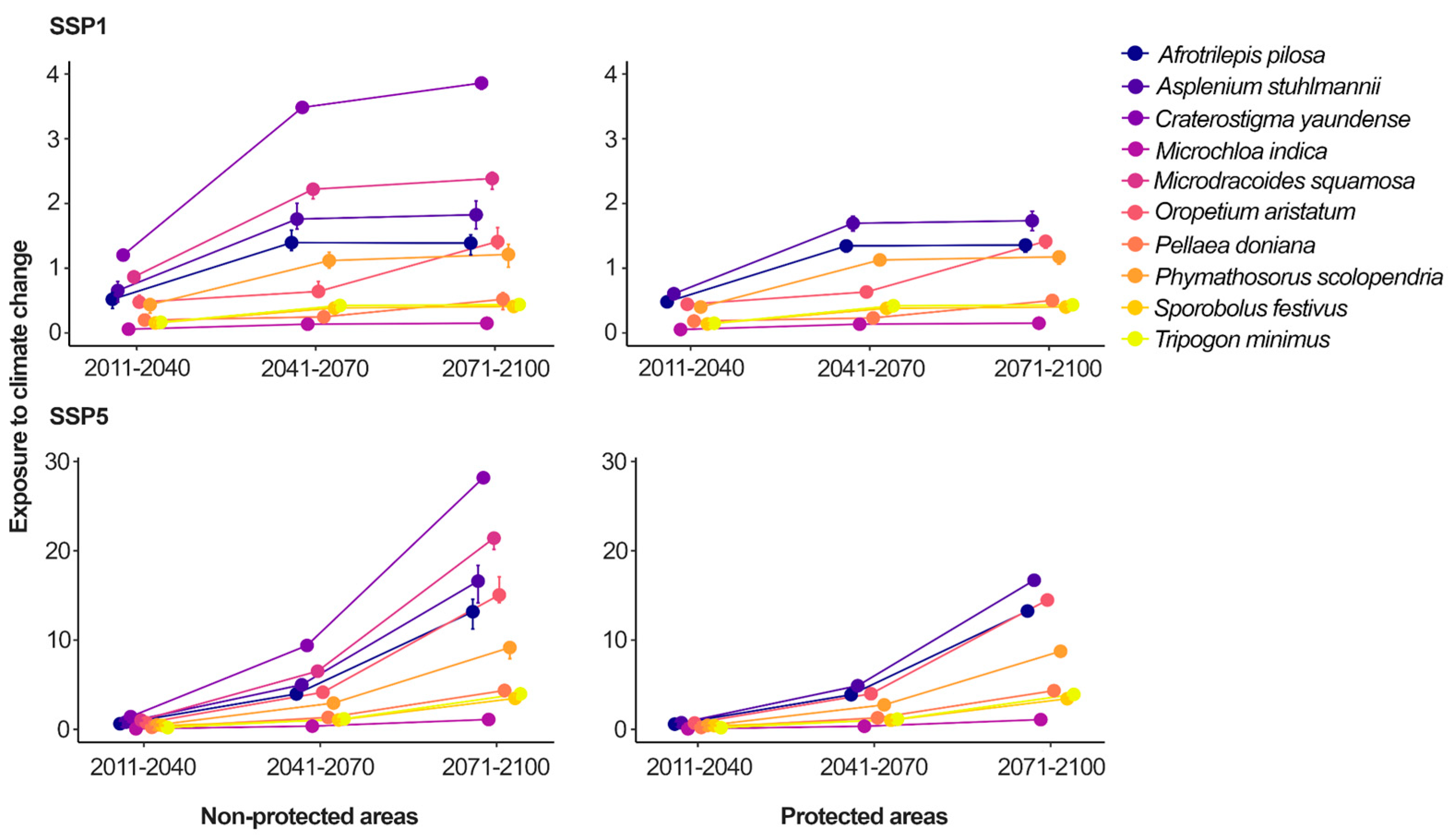

2.2. The Exposure of DT Plants to Anthropogenic Drivers of Biodiversity Loss and Their Protection on West African Inselbergs

3. Discussion

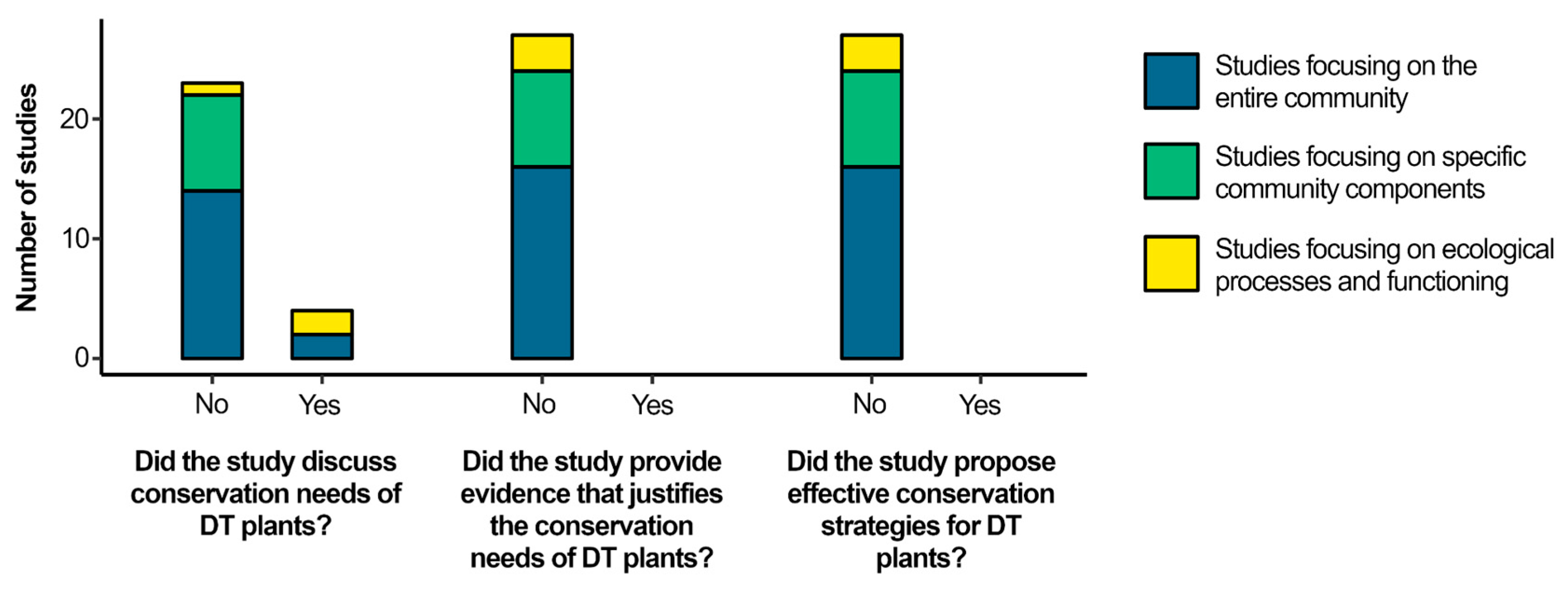

3.1. The Need of Studies Specifically Designed to Assess the Conservation of DT Plants

3.2. Protected Areas Are Not Similarly Effective in Face of Different Conservation Challenges

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Desiccation-Tolerant Vascular Plants in West Africa

4.3. Study Case to Evaluated the Exposure of DT Plants to Land Use Change and Climate Change

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Desiccation-tolerant |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| SSP | shared socioeconomic pathways |

Appendix A

| Species | GBIF (references) |

| Actiniopteris radiata | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.w7xj3c |

| Actiniopteris semiflabellata | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.u46p8v |

| Adiantum incisum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.m4pmmc |

| Afrotrilepis jaegeri | GBIF.org (28 May 2025) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7nukjh |

| Afrotrilepis pilosa | GBIF.org (18 February 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vmqcx8 |

| Allosorus coriacea | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5sremd |

| Arthropteris orientalis | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.yfu9nx |

| Asplenium aethiopicum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.hjqzcy |

| Asplenium friesiorum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.gen6n3 |

| Asplenium megalura | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.uweaw5 |

| Asplenium monanthes | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.6c9ztx |

| Asplenium sandersonii | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.k5hxv2 |

| Asplenium stuhlmannii | GBIF.org (18 February 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.2bncdt |

| Cheilanthes inaequalis | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.xba4pw |

| Coleochloa abyssinica | GBIF.org (28 May 2025) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.j3xsse |

| Coleochloa domensis | GBIF.org (28 May 2025) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.32hthf |

| Cosentinia vellea | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.dafh4z |

| Craterostigma plantagineum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.pnxv3a |

| Craterostigma yaundense | GBIF.org (18 February 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.huy7m8 |

| Crepidomanes chevalieri | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.we3am5 |

| Crepidomanes melanotrichum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.r2sdq5 |

| Didymoglossum erosum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.9avcdb |

| Elaphoglossum acrostichoides | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.698qkw |

| Heminiotis farinosa | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vzzhtk |

| Hymenophyllum capillare | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.wqpewp |

| Hymenophyllum hirsutum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.rr3cxv |

| Hymenophyllum kuhnii | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.f529nm |

| Hymenophyllum splendidum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7j4fhq |

| Loxogramme abyssinica | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.tdve7b |

| Melpomene flabelliformis | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.82wkxt |

| Microchloa indica | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.4pek7h |

| Microchloa kunthii | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.sym7kq |

| Microdracoides squamosa | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.6pwvgd |

| Oropetium aristatum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.uuvqb7 |

| Oropetium capense | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.r6247a |

| Pellaea dura | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.zsgpw2 |

| Phymatosorus scolopendria | GBIF.org (18 February 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vk237u |

| Platycerium stemaria | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ffzdam |

| Pleopeltis macrocarpa | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ekk9fu |

| Polyphlebium borbonicum | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.zvdfg9 |

| Selaginella njamnjamensis | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5uud4g |

| Sporobolus festivus | GBIF.org (18 February 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.m8h3dp |

| Sporobolus pellucidus | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7khsy2 |

| Sporobolus stapfianus | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.nx4pse |

| Tripogon major | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.pmnuqm |

| Tripogon multiflorus | GBIF.org (28 May 2025) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.9m6dnc |

| Tripogonella minima | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.gzfvm3 |

| Vittaria guineensis | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8ng3dd |

| Xerophyta schnizleinia | GBIF.org (22 March 2023) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.suyyuq |

| Bioclimatic variables |

| BIO1 – Annual Mean Temperature |

| BIO2 – Mean Diurnal Range (Mean of monthly (max temp - min temp)) |

| BIO3 – Isothermality (BIO2/BIO7) (×100) |

| BIO4 – Temperature Seasonality (standard deviation ×100) |

| BIO5 – Max Temperature of Warmest Month |

| BIO7 – Temperature Annual Range (BIO5-BIO6) |

| BIO8 – Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter |

| BIO12 – Annual Precipitation |

| BIO13 – Precipitation of Wettest Month |

| BIO14 – Precipitation of Driest Month |

| BIO15 – Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation) |

| BIO16 – Precipitation of Wettest Quarter |

| BIO17 – Precipitation of Driest Quarter |

| BIO18 – Precipitation of Warmest Quarter |

| BIO19 – Precipitation of Coldest Quarter |

| Packages | References |

| dplyr | Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D (2023). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.4, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr |

| forcats | Wickham H (2023). forcats: Tools for Working with Categorical Variables (Factors).R package version 1.0.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=forcats |

| ggplot2 | Wickham H (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. R package version 3.5.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2 |

| ggpubr | Kassambara A (2023). ggpubr: 'ggplot2' Based Publication Ready Plots. R package version 0.6.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr |

| mapdata | Brownrigg R, Minka TP, Deckmyn A (2023). mapdata: Extra Map Databases. R package version 2.3.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mapdata |

| maps | Becker RA, Wilks AR, Brownrigg R, Minka TP, Deckmyn A (2023). maps: Draw Geographical Maps. R package version 3.4.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maps |

| phytools | Revell LJ (2012). phytools: An R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 3(2), 217–223. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=phytools |

| rnaturalearth | South A (2017). rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth. R package version 0.1.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rnaturalearth |

| sf | Pebesma E (2018). Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R Journal, 10(1), 439–446. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sf |

| terra | Hijmans R (2023). terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R package version 1.7-65, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra> |

| V.PhyloMaker | Jin, Y & Qian, H. 2019. V.PhyloMaker: an R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Ecography. 42(8):1353–1359. doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04434 |

| viridis | Garnier S (2021). viridis: Default Color Maps from 'matplotlib'. R package version 0.6.4, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=viridis |

| References | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Categories |

| Gaff, D. F. (1986). Desiccation tolerant ‘resurrection’grasses from Kenya and West Africa. Oecologia, 70, 118-120. | No | No | No | II |

| Krieger, A., Porembski, S., & Barthlott, W. (2000). Vegetation of seasonal rock pools on inselbergs situated in the savanna zone of the Ivory Coast (West Africa). Flora, 195(3), 257-266. | No | No | No | II |

| Müller, J. V. (2007). Herbaceous vegetation of seasonally wet habitats on inselbergs and lateritic crusts in West and Central Africa. Folia Geobotanica, 42, 29-61. | No | No | No | II |

| Oumorou, M., & Lejoly, J. (2003). Écologie, flore et végétation de l'inselberg Sobakperou (Nord-Bénin). Acta botanica gallica, 150(1), 65-84. | No | No | No | I |

| Owoseye, J. A., & Sanford, W. W. (1972). An ecological study of Vellozia schnitzleinia, a drought-enduring plant of northern Nigeria. The Journal of Ecology, 807-817. | No | No | No | II |

| Parmentier, I. (2001). Premières études sur la diversité végétale des inselbergs de Guinée Équatoriale continentale. Systematics and Geography of Plants, 911-922. | No | No | No | I |

| Parmentier, I., & Hardy, O. J. (2009). The impact of ecological differentiation and dispersal limitation on species turnover and phylogenetic structure of inselberg's plant communities. Ecography, 32(4), 613-622. | No | No | No | I |

| Parmentier, I., Oumorou, M., Pauwels, L., & Lejoly, J. (2006). Comparison of the ecology and distribution of the Poaceae flora on inselbergs embedded in savannah (Benin) or in rain forest (Western Central Africa). Belgian Journal of Botany, 65-77. | No | No | No | II |

| Porembski, S. (2000). The invasibility of tropical granite outcrops ('inselbergs') by exotic weeds. Journal of the Royal society of Western Australia, 83, 131. | Yes | No | No | III |

| Porembski, S. (2007). Tropical inselbergs: habitat types, adaptive strategies and diversity patterns. Brazilian Journal of Botany, 30, 579-586. | Yes | No | No | I |

| Porembski, S., & Barthlott, W. (1996). Plant species diversity of West African inselbergs. In The Biodiversity of African Plants: Proceedings XIVth AETFAT Congress 22–27 August 1994, Wageningen, The Netherlands (pp. 180-187). Springer Netherlands. | No | No | No | I |

| Porembski, S., & Barthlott, W. (1997). Seasonal Dynamics of Plant Diversity on lnselbergs in the Ivory Coast (West Africa). Botanica Acta, 110(6), 466-472. | No | No | No | I |

| Porembski, S., & Watve, A. (2005). Remarks on the species composition of ephemeral flush communities on paleotropical rock outcrops. Phytocoenologia, 389-402. | No | No | No | II |

| Porembski, S., Barthlott, W., Dörrstock, S., & Biedinger, N. (1994). Vegetation of rock outcrops in Guinea: granite inselbergs, sandstone table mountains and ferricretes—remarks on species numbers and endemism. Flora, 189(4), 315-326. | Yes | No | No | I |

| Porembski, S., Becker, U., & Seine, R. (2000). Islands on islands: habitats on inselbergs. In Inselbergs: biotic diversity of isolated rock outcrops in tropical and temperate regions (pp. 49-67). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. | No | No | No | II |

| Porembski, S., Brown, G., & Barthlott, W. (1996). A species-poor tropical sedge community: Afrotrilepis pilosa mats on inselbergs in West Africa. Nordic Journal of Botany, 16(3), 239-245. | No | No | No | II |

| Porembski, S., Seine, R., & Barthlott, W. (1997). Inselberg vegetation and the biodiversity of granite outcrops. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 80, 193. | No | No | No | I |

| Porembski, S., Silveira, F. A., Fiedler, P. L., Watve, A., Rabarimanarivo, M., Kouame, F., & Hopper, S. D. (2016). Worldwide destruction of inselbergs and related rock outcrops threatens a unique ecosystem. Biodiversity and Conservation, 25, 2827-2830. | Yes | No | No | III |

| Porembski, S., Szarzynski, J., Mund, J. P., & Barthlott, W. (1996). Biodiversity and vegetation of small-sized inselbergs in a West African rain forest (Taı, Ivory Coast). Journal of Biogeography, 23(1), 47-55. | No | No | No | I |

| Richards, P. W. (1957). Ecological notes on West African vegetation: I. The plant communities of the Idanre hills, Nigeria. The Journal of Ecology, 563-577. | No | No | No | I |

| Seine, R., Porembski, S., & Barthlott, W. (1996). A neglected habitat of carnivorous plants: inselbergs. Feddes Repertorium, 106(5-8), 555-562. | No | No | No | II |

| Szarzynski, J. (2000). Xeric islands: environmental conditions on inselbergs. In Inselbergs: biotic diversity of isolated rock outcrops in tropical and temperate regions (pp. 37-48). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. | No | No | No | I |

| Tindano, E., Ganaba, S., Sambare, O., & Thiombiano, A. (2015). Sahelian inselberg vegetation in Burkina Faso. Bois & Forêts des Tropiques, 325(3), 21–33. | No | No | No | I |

| Tindano, E., Kaboré, G. E., Porembski, S., & Thiombiano, A. (2024). Plant communities on inselbergs in Burkina Faso. Heliyon, 10(1). | No | No | No | I |

| Tindano, E., Kadéba, A., Traoré, I. C. E., & Thiombiano, A. (2023). Effects of abiotic factors on the flora and vegetation of inselbergs in Burkina Faso. Environmental Advances, 12, 100378. | No | No | No | I |

| Tindano, E., Lankoandé, B., Porembski, S., & Thiombiano, A. (2023). Inselbergs: potential conservation areas for plant diversity in the face of anthropization. J. Phytol, 15, 70-79. | No | No | No | I |

| Tindano, E., Poremski, S., Koehler, J., & Thiombiano, A. (2021). Ecological and floristic characterization of inselberg habitats in Burkina Faso. Geo-Eco-Trop, 45(4), 573-588. | No | No | No | I |

| Inselbergs | Longitude | Latitude | Ap | As | Cy | Mi | Ms | Oa | Pd | Ps | Sf | Tm |

| Mt. Niangbo | -5.1775 | 8.8275 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mt. Korhogo | -5.650833 | 9.4525 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nambelegue | -5.675833 | 9.473889 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Near Korhogo | -5.615556 | 9.501111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Boundiali 1 | -6.494444 | 9.534167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Boundiali 2 | -6.626111 | 9.596667 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Boundiali 3 | -6.488056 | 9.493889 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Séguéla 1 | -6.544722 | 7.900278 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Séguéla 2 | -6.533333 | 7.9075 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Séguéla (road to Mankono) 1 | -6.638056 | 8.037222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Séguéla (road to Mankono) 2 | -6.640556 | 8.029444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Man (Cascade) | -7.628056 | 7.494722 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Danané | -8.131667 | 7.269444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Duékoué 1 | -7.365556 | 6.756389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Duékoué 2 | -7.376111 | 6.751111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Man (Dent de Man) | -7.541667 | 7.452222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mt. Niénokoué | -7.17 | 5.434444 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Rocher d’Issia | -6.581111 | 6.483333 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dabakala (Kadjeoule-Sourdi) | -4.546667 | 8.419444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nassian (Gbonkonou) | -3.500278 | 8.45 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Man (Cissus) | -7.575833 | 7.424167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tai-National Park | -7.209722 | 5.4625 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Duékoué (quarry) | -7.354167 | 6.754444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sénéma (south of Séguéla) | -6.58 | 7.7175 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Mankono | -6.271667 | 8.098333 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Bouaké | -5.112778 | 7.762222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| north of Boundiali | -6.466389 | 9.7275 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| region of Abengourou (near Aniassué) | -3.717778 | 6.655 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| region of Abengourou (near Atakro) | -3.810556 | 6.667778 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mt. Mafa | -4.043611 | 5.8525 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| near Foumbolo | -4.670833 | 8.586111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mt. Tonkoui | -7.643889 | 7.4425 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Comoé National Park, P 1 | -3.775 | 8.772222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| P 13, south of Kakpin | -3.777222 | 8.611389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Lolobo | -5.306667 | 6.969444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| west of Nassian | -3.4875 | 8.453611 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Brobo | -4.828611 | 7.662222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Bouna (ferricrete) | -3.038611 | 9.354167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Odienné | -7.625556 | 9.679167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Tiémé 1 | -7.281667 | 9.554444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Tiémé 2 | -7.253889 | 9.559444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Badandougou | -7.156944 | 9.570278 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Madinani 1 | -7.013333 | 9.629167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Madinani 2 | -6.813333 | 9.594444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Madinani 3 | -6.737778 | 9.595556 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Gbando 1 | -6.668333 | 9.556389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Gbando 2 | -6.659722 | 9.544167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| near Touba (sandstone outcrop) | -7.631111 | 8.228056 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Daloa 1 | -6.434722 | 6.829444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daloa 2 | -6.434167 | 6.849722 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sikensi 1 | -4.561667 | 5.645 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sikensi 3 | -4.5575 | 5.653611 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| near Tehini | -3.608056 | 9.595278 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Tehini (ferricrete) | -3.58 | 9.607778 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Tondoura (BF) | -4.773611 | 10.173889 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Mangodara (BF) | -4.441667 | 9.857222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Wayen (BF) | -0.983333 | 12.323611 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Zorgho (BF) | -0.632222 | 12.211111 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Léo (BF) | -2.193611 | 11.115833 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nazinga (BF) | -1.6075 | 11.178611 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Bobo-Dioulasso | -4.135278 | 11.303611 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Banfora (BF) sandstone | -4.595833 | 10.848889 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Reserve de Bontioli (BF) ferricrete | -2.955556 | 10.944167 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Po 1 | -1.123056 | 11.124722 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Po 2 | -1.084167 | 11.073611 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Soubakpérou (Benin) | 2.160278 | 9.144444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Savé (Benin) | 2.163056 | 9.144444 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Kandi 1 | 2.895556 | 11.130833 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Kandi 2 | 2.900278 | 11.108333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Goungoun (ferricrete) 1 | 3.154444 | 11.574167 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Goungoun (ferricrete) 2 | 3.150556 | 11.565 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Goungoun (ferricrete) 3 | 3.160278 | 11.543333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dassa 1 | 2.190833 | 7.782222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dassa 2 | 2.195278 | 7.753333 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dassa 3 | 2.202222 | 7.709722 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Savalou | 1.978333 | 7.965833 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Natitingou (sandstone) 1 | 1.369167 | 10.306389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Natitingou (sandstone) 2 | 1.395 | 10.301111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Natitingou (sandstone) | 1.444167 | 10.210833 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Biguina | 1.696667 | 8.764722 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Savè | 2.508056 | 8.036389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Savè 1 | 2.581944 | 8.04 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Savè 2 | 2.61 | 8.044722 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Gorobani: | 2.026389 | 9.4775 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Yebessi | 2.105278 | 9.346667 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Yebessi | 2.133056 | 9.326111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| near Kpéssou | 2.196111 | 9.296111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Kpéssou | 2.188611 | 9.285556 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Yaounde 1 | 11.393333 | 3.828056 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Yaounde 2 | 11.425556 | 3.830278 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Yaounde 3 | 11.434167 | 3.887778 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Yaounde 4 | 11.443056 | 3.827222 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Yaounde 5 | 11.466389 | 3.853056 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mamfe 1 | 9.322778 | 5.766111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mamfe 2 | 9.336944 | 5.758333 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Takamanda 1 | 9.513889 | 6.175833 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Takamanda 2 | 9.525833 | 6.111944 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Friguiagabe (sandstone outcrop) | -12.912778 | 9.976389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mt. Gangan (sandstone outcrop) 1 | -12.893056 | 10.055 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mt. Gangan (sandstone outcrop) 2 | -12.878611 | 10.078056 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Macenta | -9.460556 | 8.522222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| near Macenta | -9.491667 | 8.599167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| near Balizia | -9.605 | 8.601111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Guéckédou | -10.098611 | 8.557222 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| near Kolobingo | -10.017222 | 8.553611 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| near Técoulo | -9.984444 | 8.534167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tongo Hills 1 | -0.812778 | 10.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Tongo Hills 2 | -0.803611 | 10.688889 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Akure | 5.181944 | 7.216389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Near Akure 1 | 5.161389 | 7.343333 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Near Akure 2 | 5.171389 | 7.348611 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Near Akure 3 | 5.226389 | 7.374167 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Idanre 1 | 5.15 | 7.108889 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Idanre 2 | 5.144722 | 7.111389 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Idanre 3 | 5.133056 | 7.110833 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Idanre 4 | 5.105556 | 7.126667 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| near Idanre 1 | 5.034167 | 7.175278 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| near Idanre 2 | 5.0425 | 7.190278 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bicurga | 10.471111 | 1.583611 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Piedras Nzas 1 | 11.031944 | 1.456389 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Piedras Nzas 2 | 11.021667 | 1.463889 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dumu | 11.323611 | 1.368056 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| near Asoc | 11.276944 | 1.451111 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Species | Exposure | |||

| Quarrying | ||||

| A. pilosa | 10.75% (10 out of 93) | |||

| A. stuhlmannii | 10.75% (10 out of 93) | |||

| C. yaundense | 60% (3 out of 5) | |||

| M. indica | 8.89% (8 out of 90) | |||

| M. squamosa | 40% (4 out of 10) | |||

| O. aristatum | 13.33% (2 out of 15) | |||

| P. doniana | 13.64% (15 out of 110) | |||

| P. scolopendria | 14.63% (6 out of 41) | |||

| S. festivus | 8.26% (9 out of 109) | |||

| T. minimus | 7.04% (5 out of 71) | |||

| Climate change | 2011-2040 | 2041-2070 | 2071_2100 | |

| SSP1 | ||||

| A. pilosa | 0.51 (0.38 - 0.63) | 1.39 (1.25 - 1.59) | 1.38 (1.21 - 1.51) | |

| A. stuhlmannii | 0.65 (0.48 - 0.79) | 1.75 (1.58 - 2) | 1.81 (1.58 - 2.04) | |

| C. yaundense | 1.2 (1.17 - 1.22) | 3.48 (3.46 - 3.5) | 3.86 (3.76 - 3.91) | |

| M. indica | 0.06 (0.04 - 0.08) | 0.14 (0.12 - 0.15) | 0.15 (0.12 - 0.18) | |

| M. squamosa | 0.87 (0.77 - 0.91) | 2.22 (2.07 - 2.3) | 2.39 (2.22 - 2.48) | |

| O. aristatum | 0.47 (0.44 - 0.58) | 0.64 (0.59 - 0.8) | 1.41 (1.3 - 1.63) | |

| P. doniana | 0.2 (0.14 - 0.27) | 0.25 (0.19 - 0.3) | 0.52 (0.36 - 0.62) | |

| P. scolopendria | 0.43 (0.31 - 0.53) | 1.12 (1 - 1.25) | 1.21 (1.02 - 1.37) | |

| S. festivus | 0.15 (0.11 - 0.2) | 0.38 (0.35 - 0.43) | 0.41 (0.33 - 0.48) | |

| T. minimus | 0.16 (0.13 - 0.21) | 0.42 (0.39 - 0.48) | 0.44 (0.35 - 0.53) | |

| SSP5 | ||||

| A. pilosa | 0.62 (0.47 - 0.71) | 3.95 (3.47 - 4.27) | 13.19 (11.24 - 14.57) | |

| A. stuhlmannii | 0.78 (0.59 - 0.9) | 4.98 (4.34 - 5.37) | 16.62 (14.16 - 18.37) | |

| C. yaundense | 1.43 (1.42 - 1.43) | 9.39 (9.35 - 9.42) | 28.18 (28.07 - 28.41) | |

| M. indica | 0.06 (0.05 - 0.09) | 0.36 (0.28 - 0.42) | 1.1 (0.94 - 1.26) | |

| M. squamosa | 1.02 (0.95 - 1.08) | 6.52 (6.14 - 6.76) | 21.42 (20.15 - 21.84) | |

| O. aristatum | 0.74 (0.69 - 0.88) | 4.11 (3.87 - 4.84) | 14.9 (14.19 - 17.08) | |

| P. doniana | 0.23 (0.16 - 0.29) | 1.33 (0.94 - 1.52) | 4.35 (3.67 - 4.77) | |

| P. scolopendria | 0.49 (0.36 - 0.59) | 2.92 (2.55 - 3.22) | 9.11 (7.9 - 9.74) | |

| S. festivus | 0.44 (0.35 - 0.51) | 1.05 (0.83 - 1.18) | 3.46 (3.04 - 4.04) | |

| T. minimus | 0.2 (0.16 - 0.23) | 1.17 (0.93 - 1.33) | 3.96 (3.46 - 4.6) | |

| Species | Number of non-protected inselbergs | Number of protected inselbergs | |||||

| Without quarrying | With quarrying | Without quarrying | With quarrying | ||||

| A. pilosa | 69 (88%) | 9 (12%) | 14 (93%) | 1 (7%) | |||

| A. stuhlmannii | 69 (88%) | 9 (12%) | 14 (93%) | 1 (7%) | |||

| C. yaundense | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | - | - | |||

| M. indica | 65 (90%) | 7 (10%) | 17 (94%) | 1 (6%) | |||

| M. squamosa | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | - | - | |||

| O. aristatum | 9 (82%) | 2 (18%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| P. doniana | 78 (85%) | 14 (15%) | 17 (94%) | 1 (6%) | |||

| P. scolopendria | 30 (83%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| S. festivus | 80 (91%) | 8 (9%) | 20 (95%) | 1 (5%) | |||

| T. minimus | 51 (93%) | 4 (7%) | 15 (94%) | 1 (6%) | |||

| Species | Non-protected inselbergs | Protected inselbergs | ||||

| 2011-2040 | 2041-2070 | 2071_2100 | 2011-2041 | 2041-2071 | 2071_2101 | |

| SSP1 | ||||||

| A. pilosa | 0.52 (0.38 - 0.63) | 1.4 (1.27 - 1.59) | 1.39 (1.21 - 1.51) | 0.48 (0.44 - 0.55) | 1.34 (1.25 - 1.43) | 1.36 (1.25 - 1.42) |

| A. stuhlmannii | 0.66 (0.48 - 0.79) | 1.76 (1.61 - 2) | 1.83 (1.61 - 2.04) | 0.61 (0.56 - 0.69) | 1.69 (1.58 - 1.8) | 1.73 (1.58 - 1.88) |

| C. yaundense | 1.2 (1.17 - 1.22) | 3.48 (3.46 - 3.5) | 3.86 (3.76 - 3.91) | - | - | - |

| M. indica | 0.06 (0.04 - 0.08) | 0.14 (0.12 - 0.15) | 0.15 (0.12 - 0.18) | 0.05 (0.04 - 0.06) | 0.14 (0.13 - 0.14) | 0.15 (0.15 - 0.16) |

| M. squamosa | 0.87 (0.77 - 0.91) | 2.22 (2.07 - 2.3) | 2.39 (2.22 - 2.48) | - | - | - |

| O. aristatum | 0.48 (0.44 - 0.58) | 0.64 (0.59 - 0.8) | 1.41 (1.3 - 1.63) | 0.44 (0.44 - 0.44) | 0.63 (0.59 - 0.65) | 1.42 (1.31 - 1.45) |

| P. doniana | 0.2 (0.14 - 0.27) | 0.25 (0.19 - 0.3) | 0.52 (0.36 - 0.62) | 0.18 (0.16 - 0.2) | 0.23 (0.21 - 0.25) | 0.5 (0.47 - 0.56) |

| P. scolopendria | 0.44 (0.31 - 0.53) | 1.12 (1 - 1.25) | 1.21 (1.02 - 1.37) | 0.4 (0.39 - 0.41) | 1.13 (1.09 - 1.16) | 1.18 (1.06 - 1.22) |

| S. festivus | 0.15 (0.11 - 0.2) | 0.39 (0.35 - 0.43) | 0.41 (0.33 - 0.48) | 0.14 (0.12 - 0.16) | 0.38 (0.36 - 0.41) | 0.4 (0.38 - 0.44) |

| T. minimus | 0.17 (0.14 - 0.21) | 0.42 (0.39 - 0.48) | 0.44 (0.35 - 0.53) | 0.15 (0.13 - 0.17) | 0.42 (0.39 - 0.45) | 0.43 (0.41 - 0.46) |

| SSP5 | ||||||

| A. pilosa | 0.63 (0.47 - 0.71) | 3.97 (3.47 - 4.27) | 13.18 (11.24 - 14.57) | 0.59 (0.49 - 0.67) | 3.88 (3.59 - 4.1) | 13.25 (12.74 - 13.63) |

| A. stuhlmannii | 0.79 (0.59 - 0.9) | 5 (4.34 - 5.37) | 16.6 (14.16 - 18.37) | 0.74 (0.61 - 0.84) | 4.89 (4.52 - 5.16) | 16.7 (16.05 - 17.17) |

| C. yaundense | 1.43 (1.42 - 1.43) | 9.39 (9.35 - 9.42) | 28.18 (28.07 - 28.41) | - | - | - |

| M. indica | 0.07 (0.05 - 0.09) | 0.36 (0.28 - 0.42) | 1.11 (0.94 - 1.26) | 0.06 (0.06 - 0.07) | 0.35 (0.32 - 0.38) | 1.09 (1.03 - 1.15) |

| M. squamosa | 1.02 (0.95 - 1.08) | 6.52 (6.14 - 6.76) | 21.42 (20.15 - 21.84) | - | - | - |

| O. aristatum | 0.75 (0.69 - 0.88) | 4.15 (3.89 - 4.84) | 15.06 (14.19 - 17.08) | 0.71 (0.7 - 0.71) | 3.99 (3.87 - 4.02) | 14.48 (14.3 - 14.54) |

| P. doniana | 0.23 (0.16 - 0.29) | 1.34 (0.94 - 1.52) | 4.36 (3.67 - 4.77) | 0.22 (0.19 - 0.24) | 1.29 (1.18 - 1.36) | 4.34 (4.14 - 4.52) |

| P. scolopendria | 0.5 (0.36 - 0.59) | 2.95 (2.56 - 3.22) | 9.16 (7.9 - 9.74) | 0.45 (0.42 - 0.47) | 2.74 (2.55 - 2.88) | 8.75 (8.32 - 9.07) |

| S. festivus | 0.44 (0.35 - 0.51) | 1.06 (0.83 - 1.18) | 3.47 (3.04 - 4.04) | 0.42 (0.38 - 0.47) | 1.02 (0.94 - 1.08) | 3.43 (3.27 - 3.57) |

| T. minimus | 0.2 (0.16 - 0.23) | 1.18 (0.93 - 1.33) | 3.97 (3.46 - 4.6) | 0.19 (0.16 - 0.21) | 1.14 (1.06 - 1.22) | 3.92 (3.75 - 4.05) |

References

- Sinclair, A.R.E. The loss of biodiversity: The sixth great extinction. In Conserving Nature’s Diversity; Ashgate: Vermont, 2000; pp. 9–15.

- Bergès, L.; Roche, P.; Avon, C. Corridors écologiques et conservation de la biodiversité. Sci. Eaux Territ. 2010, 3, 34–39.

- Jaureguiberry, P.; Titeux, N.; Wiemers, M.; Bowler, D.E.; Coscieme, L.; Golden, A.S.; Guerra, C.A.; Jacob, U.; Takahashi, Y.; Settele, J.; et al. The direct drivers of recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9982. [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Marino, C.; Courchamp, F. Ranking threats to biodiversity and why it doesn’t matter. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Sharp, R.P.; Weil, C.; Bennett, E.M.; Pascual, U.; Arkema, K.K.; Brauman, K.A.; Bryant, B.P.; Guerry, A.D.; Haddad, N.M.; et al. Global modeling of nature’s contributions to people. Science 2019, 366, 255–258. [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Sanderson, E.W.; Magrach, A.; Allan, J.R.; Beher, J.; Jones, K.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Laurance, W.F.; Wood, P.; Fekete, B.M.; et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conser-vation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12558. [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. State of the Climate in Africa 2024; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [CrossRef]

- Marks, R.A.; Farrant, J.M.; McLetchie, D.N.; VanBuren, R. Unexplored dimensions of variability in vegetative desiccation tolerance. Am. J. Bot. 2021, 108, 346–358, . [CrossRef]

- Porembski, S.; Barthlott, W. Granitic and gneissic outcrops (inselbergs) as centers of diversity for desiccation-tolerant vascular plants. Plant Ecol. 2000, 151, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.C.D.; Farrant, J.M.; Oliver, M.J.; Ligterink, W.; Buitink, J.; Hilhorst, H.M. Key genes involved in desiccation tolerance and dormancy across life forms. Plant Sci. 2016, 251, 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Hilhorst, H.W.; Farrant, J.M. Plant desiccation tolerance: A survival strategy with exceptional prospects for climate-smart agriculture. Annu. Plant Rev. Online 2018, 327–354.

- Gaff, D.F. Protoplasmic tolerance of extreme water stress. In Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology; Springer: Berlin, 1981.

- Porembski, S.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Fiedler, P.L.; Watve, A.; Rabarimanarivo, M.; Kouame, F.; Hopper, S.D. Worldwide destruction of inselbergs and related rock outcrops threatens a unique ecosystem. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 25, 2827–2830. [CrossRef]

- Porembski, S. Tropical inselbergs: habitat types, adaptive strategies and diversity patterns. Braz. J. Bot. 2007, 30, 579–586. [CrossRef]

- Porembski, S. The invasibility of tropical granite outcrops (‘inselbergs’) by exotic weeds. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2000, 83, 131.

- Porembski, S.; Barthlott, W.; Dörrstock, S.; Biedinger, N. Vegetation of rock outcrops in Guinea: granite inselbergs, sandstone table mountains and ferricretes — remarks on species numbers and endemism. Flora 1994, 189, 315–326. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.P.; Jackson, S.T.; House, J.I.; Prentice, I.C.; Mace, G.M. Beyond Predictions: Biodiversity Conservation in a Changing Climate. Science 2011, 332, 53–58. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.J.; Tuba, Z.; Mishler, B.D. The evolution of vegetative desiccation tolerance in land plants. Plant Ecol. 2000, 151, 85–100. [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Dollo on Dollo's law: Irreversibility and the status of evolutionary laws. J. Hist. Biol. 1970, 3, 189–212. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, R. Biodiversity protection prioritisation: a 25-year review. Wildl. Res. 2013, 40, 108–116. [CrossRef]

- IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) West Africa Plant Red List Authority. Advancing Plant Conservation in West Africa through Red List Assessments. 2025. Available online: https://www.iucn.org (accessed April 2025).

- IUCN. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1, 2nd ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012.

- Zizka, A.; Andermann, T.; Silvestro, D. IUCNN – Deep learning approaches to approximate species’ extinction risk. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 227–241.

- Bachman, S.P.; Brown, M.J.M.; Leão, T.C.C.; Nic Lughadha, E.; Walker, B.E. Extinction risk predictions for the world's flowering plants to support their conservation. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 797–808. [CrossRef]

- Cazalis, V.; Di Marco, M.; Zizka, A.; Butchart, S.H.; González-Suárez, M.; Böhm, M.; Bachman, S.P.; Hoffmann, M.; Rosati, I.; De Leo, F.; et al. Accelerating and standardising IUCN Red List assessments with sRedList. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 298. [CrossRef]

- Tecco, P.A.; Díaz, S.; Cabido, M.; Urcelay, C. Functional traits of alien plants across contrasting climatic and land-use regimes. J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 17–27.

- Chesson, P. Mechanisms of Maintenance of Species Diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 343–366. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.A.; Chew, M.K.; Hobbs, R.J.; Lugo, A.E.; Ewel, J.J.; Vermeij, G.J.; Brown, J.H.; Rosenzweig, M.L.; Gardener, M.R.; Carroll, S.P.; et al. Don’t judge species on their origins. Nature 2011, 474, 153–154. [CrossRef]

- Moro, M.F.; Souza, V.C.; Oliveira-Filho, A.T.; Queiroz, L.P.; Fraga, C.N.; Rodal, M.J.N.; Araújo, F.S.; Martins, F.R. Alienígenas na sala: O que fazer com espécies exóticas em trabalhos de taxonomia, florística e fitossociologia? Acta Bot. Bras. 2012, 26, 991–999.

- Grime, J.P. Evidence for the Existence of Three Primary Strategies in Plants and Its Relevance to Ecological and Evolutionary Theory. Am. Nat. 1977, 111, 1169–1194. [CrossRef]

- de Paula, L.F.A.; Negreiros, D.; Azevedo, L.O.; Fernandes, R.L.; Stehmann, J.R.; Silveira, F.A.O. Functional ecology as a missing link for conservation of a resource-limited flora in the Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 2239–2253. [CrossRef]

- Kumschick, S.; Gaertner, M.; Vilà, M.; Essl, F.; Jeschke, J.M.; Pyšek, P.; Ricciardi, A.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Dick, J.T.A.; et al. Ecological Impacts of Alien Species: Quantification, Scope, Caveats, and Recommendations. BioScience 2015, 65, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Dehling, D.M.; Stouffer, D.B. Bringing the Eltonian niche into functional diversity. Oikos 2018, 127, 1711–1723. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.H. On the Relationship between Abundance and Distribution of Species. Am. Nat. 1984, 124, 255–279. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.N. Species extinction and the relationship between distribution and abundance. Nature 1998, 394, 272–274. [CrossRef]

- Violle, C.; Thuiller, W.; Mouquet, N.; Munoz, F.; Kraft, N.J.; Cadotte, M.W.; Livingstone, S.W.; Mouillot, D. Functional Rarity: The Ecology of Outliers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 356–367. [CrossRef]

- Zokov, E. First Insights into Alternative Functional Designs of Desiccation-Tolerant Plants’ Desiccation. Master’s Thesis, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany, 2024.

- Porembski, S.; Barthlott, W. Plant species diversity of West African inselbergs. In The Biodiversity of African Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, 1996; pp. 180–187.

- Smith, R.J.; Veríssimo, D.; Isaac, N.J.; Jones, K.E. Identifying Cinderella species: uncovering mammals with conservation flagship appeal. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 205–212. [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Flagships, umbrellas, and keystones: Is single-species management passé in the landscape era? Biol. Conserv. 1998, 83, 247–257.

- Moynes, E.; Bhathe, V.P.; Brennan, C.; Ellis, S.; Bennett, J.R.; Landsman, S.J. Flagship Species: Do They Help or Hurt Conservation?. Front. Young- Minds 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.H.; Burgess, N.D.; Rahbek, C. Flagship species, ecological complementarity and conserving the diversity of mammals and birds in sub-Saharan Africa. Anim. Conserv. 2000, 3, 249–260. [CrossRef]

- Mazel, F.; Pennell, M.W.; Cadotte, M.W.; Diaz, S.; Riva, G.V.D.; Grenyer, R.; Leprieur, F.; Mooers, A.O.; Mouillot, D.; Tucker, C.M.; et al. Prioritizing phylogenetic diversity captures functional diversity unreliably. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Balding, M.; Williams, K.J. Plant blindness and the implications for plant conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 1192–1199. [CrossRef]

- Caro, T.M.; O'DOherty, G. On the Use of Surrogate Species in Conservation Biology. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 805–814. [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, R.J. Focal Species: A Multi-Species Umbrella for Nature Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 1997, 11, 849–856. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.D.; Weiland, P.S. The use of surrogates in implementation of the federal Endangered Species Act—proposed fixes to a proposed rule. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2014, 4, 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, J.H. Range, population abundance and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1993, 8, 409–413.

- Flather, C.H.; Sieg, C.H. Species rarity: Definition, causes and classification. In Conservation of Rare or Little-Known Species; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2007; pp. 40–66.

- CBD. COP 10 Decisions: Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020. 2025. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop?id=12268 (accessed April 2025).

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN. Protected Planet Report 2024; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2024.

- Daru, B.H. Predicting undetected native vascular plant diversity at a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; zu Ermgassen, S.O.; Ferri-Yanez, F.; Navarro, L.M.; Rosa, I.M.; Teixeira, F.Z.; Liu, J. Unearthing the global impact of mining construction minerals on biodiversity. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.03.

- Timpte, M.; Marquard, E.; Paulsch, C. Analysis of the Strategic Plan 2011–2020 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). IBN: Regensburg, Germany, 2018.

- McIntyre, N.E.; Wiens, J.A. Interactions between Habitat Abundance and Configuration: Experimental Validation of Some Predictions from Percolation Theory. Oikos 1999, 86, 129. [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.G. Using landscape fragmentation thresholds to determine ecological process targets in systematic conservation plans. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 221, 257–260. [CrossRef]

- Keitt, T.; Urban, D.L.; Milne, B.T. Detecting Critical Scales in Fragmented Landscapes. Conserv. Ecol. 1997, 1. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, M.G.; Orme, C.D.L.; Suttle, K.B.; Mace, G.M. Separating sensitivity from exposure in assessing extinction risk from climate change. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6898. [CrossRef]

- Carriquí, M.; Fortesa, J.; Brodribb, T.J. A loss of stomata exposes a critical vulnerability to variable atmospheric humidity in ferns. Curr. Biol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fage, J.D.; McCaskie, T. Western Africa. In Encyclopedia Britannica; 2025. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/western-Africa (accessed 10 April 2025).

- Sinsin, B.; Kampmann, D.; Thiombiano, A.; Konaté, S. Atlas de la Biodiversité de l’Afrique de l’Ouest. Tome I: Benin; Cotonou & Frankfurt/Main, 2010.

- Mallon, D.P.; Hoffmann, M.; Grainger, M.J.; Hibert, F.; van Vliet, N.; McGowan, P.J.K. An IUCN situation analysis of terrestrial and freshwater fauna in West and Central Africa. IUCN Occas. Pap. 2015, 54.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. he PRISMA 2020 statement : an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Dalziel, J.M. Flora of West Tropical Africa; Crown Agents: London, UK, 1958; Volume 1.

- Adjanohoun, E. Végétation des savanes et des rochers découverts en Côte d’Ivoire Centrale. Mém. ORSTOM 1964, 7, 1–178.

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. 2025. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed 12 April 2025).

- IUCN. The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, version 2022. https://www.iucnredlist.org/. (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Rinnan, D.S.; Lawler, J. Climate-niche factor analysis: a spatial approach to quantifying species vulnerability to climate change. Ecography 2019, 42, 1494–1503. [CrossRef]

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 28 March 2019).

- Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B.; Hardy, C. Discourse and institutions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 635–652.

- Karger, D.N.; Lange, S.; Hari, C.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Conrad, O.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Frieler, K. CHELSA-W5E5: daily 1 km meteorological forcing data for climate impact studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2445–2464. [CrossRef]

- Wisz, M.S.; Hijmans, R.J.; Li, J.; Peterson, A.T.; Graham, C.H.; Guisan, A.; NCEAS Predicting Species Distributions Working Group. Effects of sample size on the performance of species distribution models. Divers. Distrib. 2008, 14, 763–773. [CrossRef]

- Barbet-Massin, M.; Jiguet, F.; Albert, C.H.; Thuiller, W. Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: How, where and how many? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 327–338.

- Jin, Y.; Qian, H. V.PhyloMaker: an R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Ecography 2019, 42, 1353–1359. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

| Distribution in West Africa | IUCN Red List categories | |||

| LYCOPHYTES | ||||

| SELAGINELLACEAE | ||||

| Selaginella njamnjamensis Hieron. | BEN, CMR, MLI, NGA | Not evaluated | ||

| PTERIDOPHYTES | ||||

| ASPLENIACEAE | ||||

| Asplenium aethiopicum (Burm.f.) Becherer | CIV, CMR, GGN, GIN, GNQ, LBR, NER, NGA, SLE, TCD | Vulnerable | ||

| Asplenium friesiorum C.Chr. | CMR, GGN, NGA | Not evaluated | ||

| Asplenium megalura Hieron. | CIV, CMR, GHA, GGN, GIN, LBR, SLE, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Asplenium monanthes L. | CMR, GGN | Least Concern | ||

| Asplenium sandersonii Hook. | CMR, GGN, GNQ, NGA | Not evaluated | ||

| Asplenium stuhlmannii Hieron. | CIV, CMR, GIN, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| DRYOPTERIDACEAE | ||||

| Elaphoglossum acrostichoides (Hook. & Grev.) Schelpe | CIV, CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, LBR | Least Concern | ||

| HYMENOPHYLLACEAE | ||||

| Crepidomanes chevalieri (Christ) Ebihara & Dubuisson | CIV, CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, LBR, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Crepidomanes melanotrichum (Schltdl.) J.P.Roux | CIV, CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, LBR, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Didymoglossum erosum (Willd.) Beentje | CIV, CMR, GHA, GIN, LBR, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Hymenophyllum capillare Desv. | CMR, GGN, GHA | Not evaluated | ||

| Hymenophyllum hirsutum (L.) Sw. | CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, GNQ, CIV, LBR | Not evaluated | ||

| Hymenophyllum kuhnii C.Chr. | CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, GNQ, LBR, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Hymenophyllum splendidum Bosch | CMR, GNQ | Not evaluated | ||

| Polyphlebium borbonicum (Bosch) Ebihara & Dubuisson | CIV, CMR, GGN, GNQ, GHA, GIN, LBR | Not evaluated | ||

| POLYPODIACEAE | ||||

| Loxogramme abyssinica (Baker) M.G.Price | CIV, CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, GNQ, LBR, NGA, SLE, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Melpomene flabelliformis (Poir.) A.R.Sm. & R.C.Moran | CMR, GGN | Not evaluated | ||

| Phymatosorus scolopendria (Burm.f.) Pic.Serm. | BEN, CIV, CMR, GGN, GNQ, GHA, GIN, LBR, NGA, SLE, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Platycerium stemaria (P.Beauv.) Desv. | BEN, CIV, CMR, GGN, GNQ, GHA, GIN, LBR, NGA, SEN, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Pleopeltis macrocarpa (Willd.) Kaulf. | CIV, CMR, GGN, GIN, LBR, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| PTERIDACEAE | ||||

| Actiniopteris radiata (Sw.) Link | CMR, CPV, MLI, NGA, TCD, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Actiniopteris semiflabellata Pic.Serm. | MRT | Not evaluated | ||

| Adiantum incisum Forssk. | CIV, CMR, CPV, GHA, NGA, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Cheilanthes coriacea Decne. | NER, TCD | Not evaluated | ||

| Cheilanthes inaequalis Mett. | CMR, GIN, NGA | Not evaluated | ||

| Cosentinia vellea (Aiton) Tod. | CPV | Least Concern | ||

| Hemionitis farinosa (Forssk.) Christenh. | CMR, GGN, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Pellaea doniana Hook. | GNQ | Not evaluated | ||

| Vittaria guineensis Desv. | CIV, CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, GNQ, LBR, NGA, SLE, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| TECTARIACEAE | ||||

| Arthropteris orientalis (J.F.Gmel.) Posth. | CIV, CMR, GGN, GHA, GIN, LBR, NGA, SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| ANGIOSPERMS | ||||

| CYPERACEAE | ||||

| Afrotrilepis jaegeri J.Raynal | SLE * | Not evaluated | ||

| Afrotrilepis pilosa (Boeckeler) J.Raynal | BEN, BFA, CIV, CMR, GHA, GIN, GNQ, LBR, MLI, NGA, SEN, SLE, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Coleochloa abyssinica (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Gilly | CMR, NGA | Not evaluated | ||

| Coleochloa domensis Muasya & D.A.Simpson | CMR * | Critically endangered | ||

| Microdracoides squamosa Hua | CMR, GIN, NGA, SLE * | Not evaluated | ||

| LINDERNIACEAE | ||||

| Craterostigma plantagineum Hochst. | BFA, NER, TCD | Not evaluated | ||

| Craterostigma yaundense (S.Moore) Eb.Fisch., Schäferh. & Kai Müll. | CMR * | Vulnerable | ||

| POACEAE | ||||

| Microchloa indica (L.f.) P.Beauv. | BEN, BFA, CIV, CMR, GHA, GIN, GNB, MLI, NER, NGA, SEN, SLE, TCD, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Microchloa kunthii Desv. | BEN, BFA, CIV, CMR, GHA, NGA, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Oropetium aristatum (Stapf) Pilg. | BEN, BFA, CIV, GHA, GMB, GNB, MLI, NER, SEN, TGO * | Not evaluated | ||

| Oropetium capense Stapf | MLI, MRT, NER, TCD | Not evaluated | ||

| Sporobolus festivus Hochst. ex A.Rich. | BEN, BFA, CIV, CMR, GHA, GIN, GMB, GNQ, MLI, MRT, NER, NGA, SEN, TCD, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| Sporobolus pellucidus Hochst. | BFA, NER, TCD | Not evaluated | ||

| Sporobolus stapfianus Gand. | NER, NGA | Least Concern | ||

| Tripogon major Hook.f. | SLE | Not evaluated | ||

| Tripogon multiflorus Miré & H.Gillet | CPV, NER, TCD | Not evaluated | ||

| Tripogonella minima (A.Rich.) P.M.Peterson & Romasch. | BEN, BFA, CIV, CMR, CPV, GHA, MLI, MRT, NER, NGA, SEN, TCD, TGO | Not evaluated | ||

| VELLOZIACEAE | ||||

| Xerophyta schnitzleinia (Hochst.) Baker | NGA, GNQ | Not evaluated | ||

| W-value/ t-value | p-value | |||

| Quarrying | 80 | 0.0004 | ||

| Climate change | ||||

| SSP1 | ||||

| 2011-2040 | 1.17 | 0.7809 | ||

| 2041-2070 | 1.04 | 0.9456 | ||

| 2071-2100 | 1.05 | 0.9297 | ||

| SSP5 | ||||

| 2011-2040 | 1.1 | 0.8592 | ||

| 2041-2070 | 1.03 | 0.9519 | ||

| 2071-2100 | 0.93 | 1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).