Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Survey Site

2.1.2. Density Survey of Sphaerolecanium prunastri

2.1.3. Damage Ranking of Wild Apricot

2.1.4. The growth of Wild Apricots

2.1.5. Assessment of Flower Buds and Fruit Yield

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

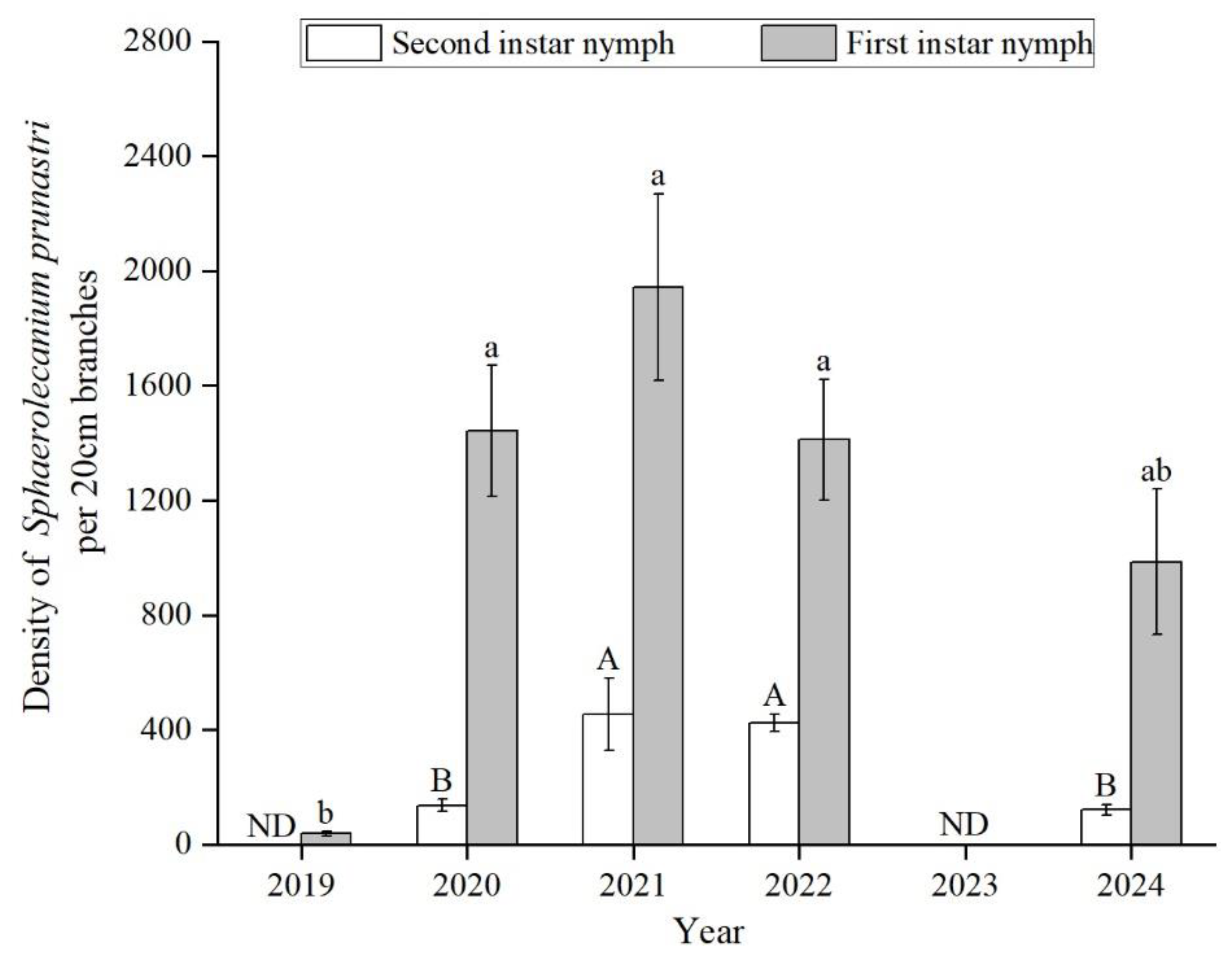

3.1. Population Dynamics of GS Nymph Over Years

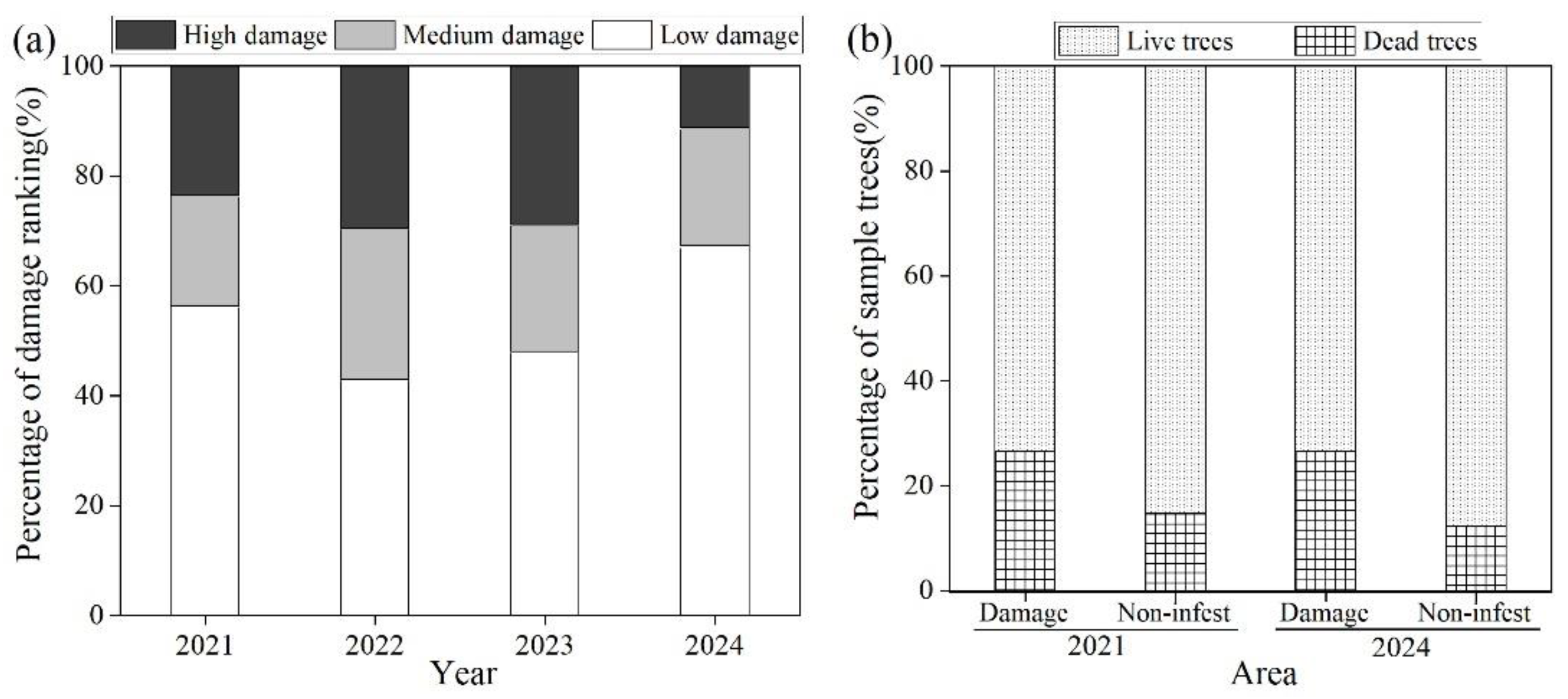

3.2. Damage Ranking of Wild Apricot

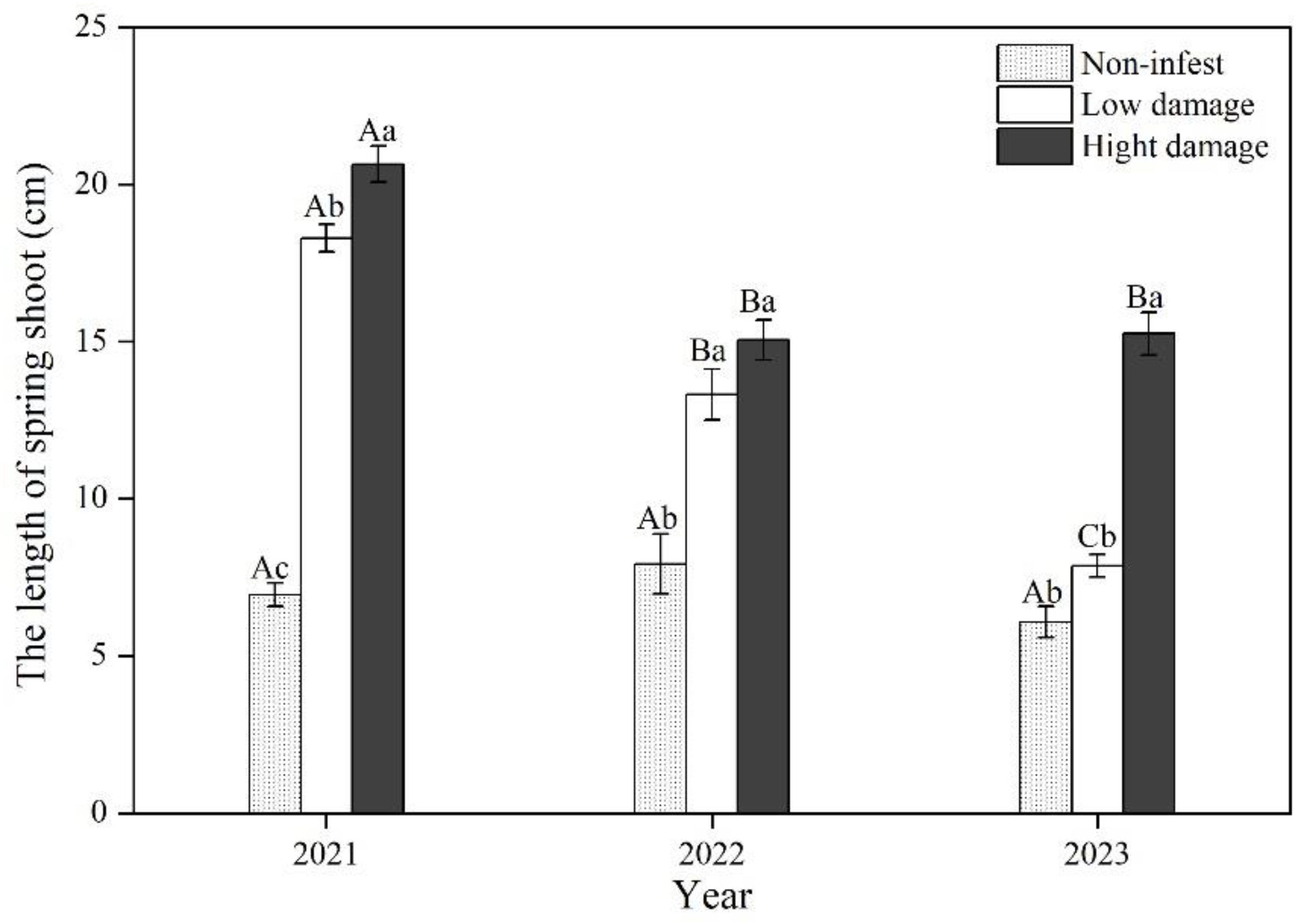

3.3. Length of Spring Shoots Among Damage Rankings

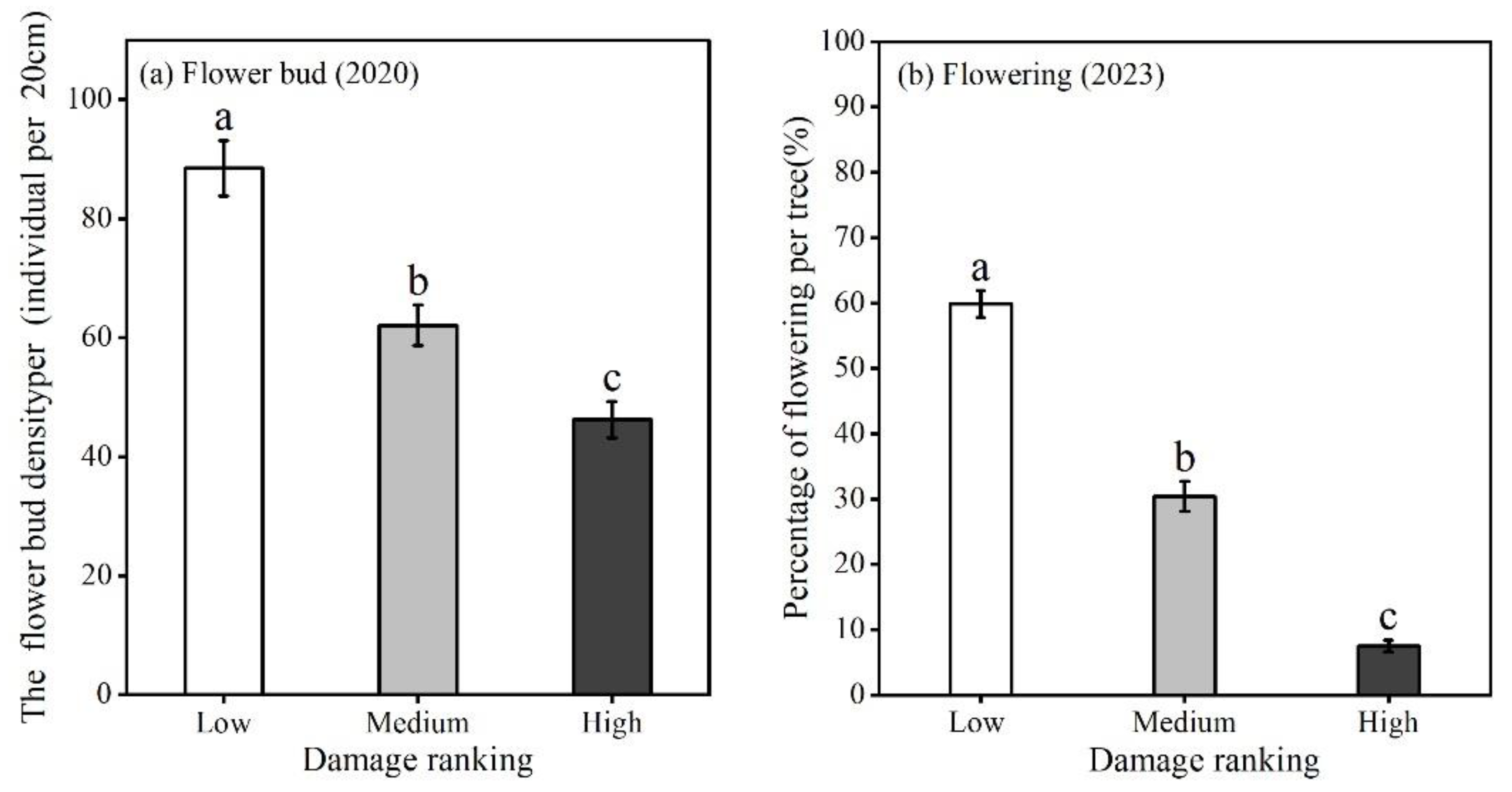

3.4. Flower Buds and Flowering

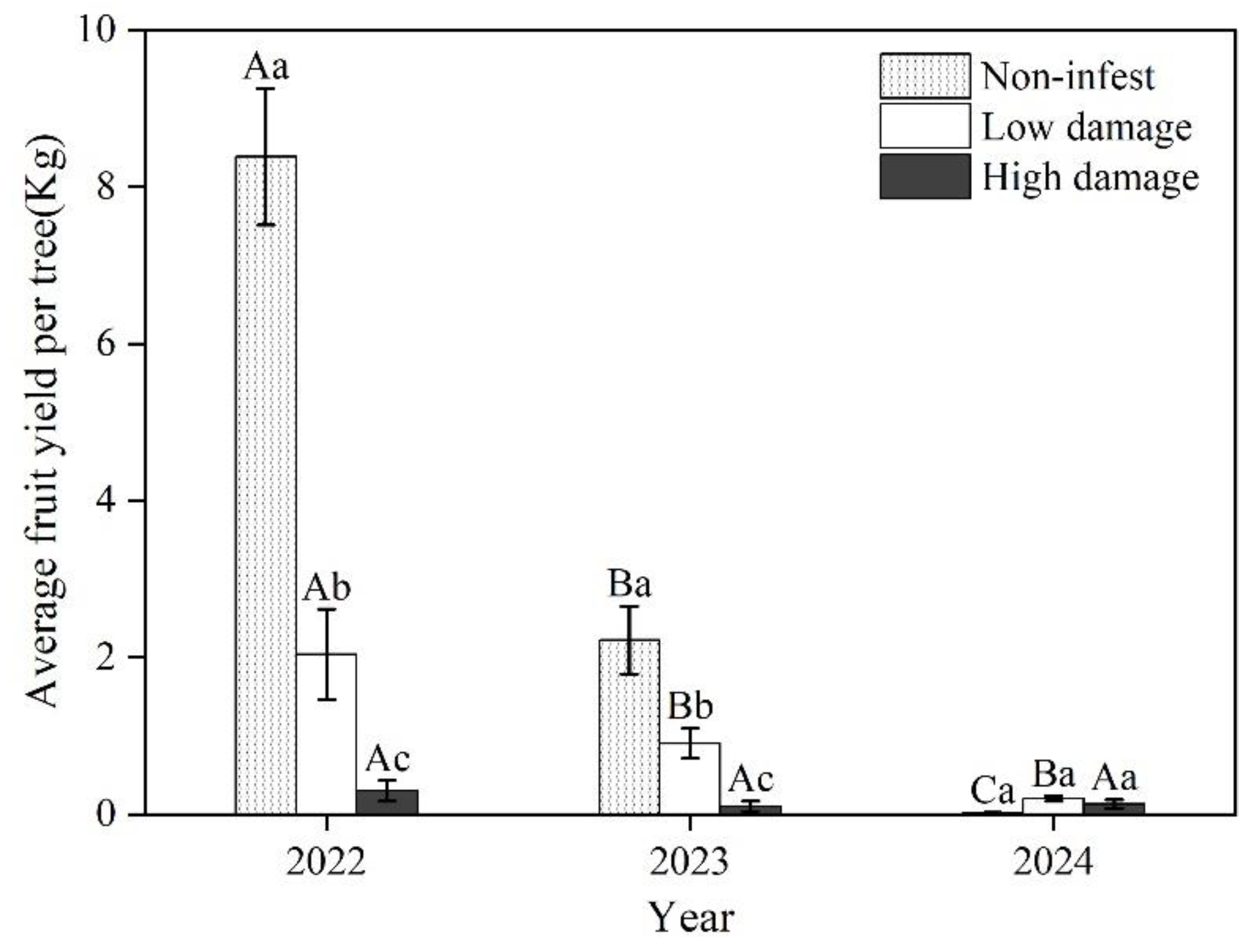

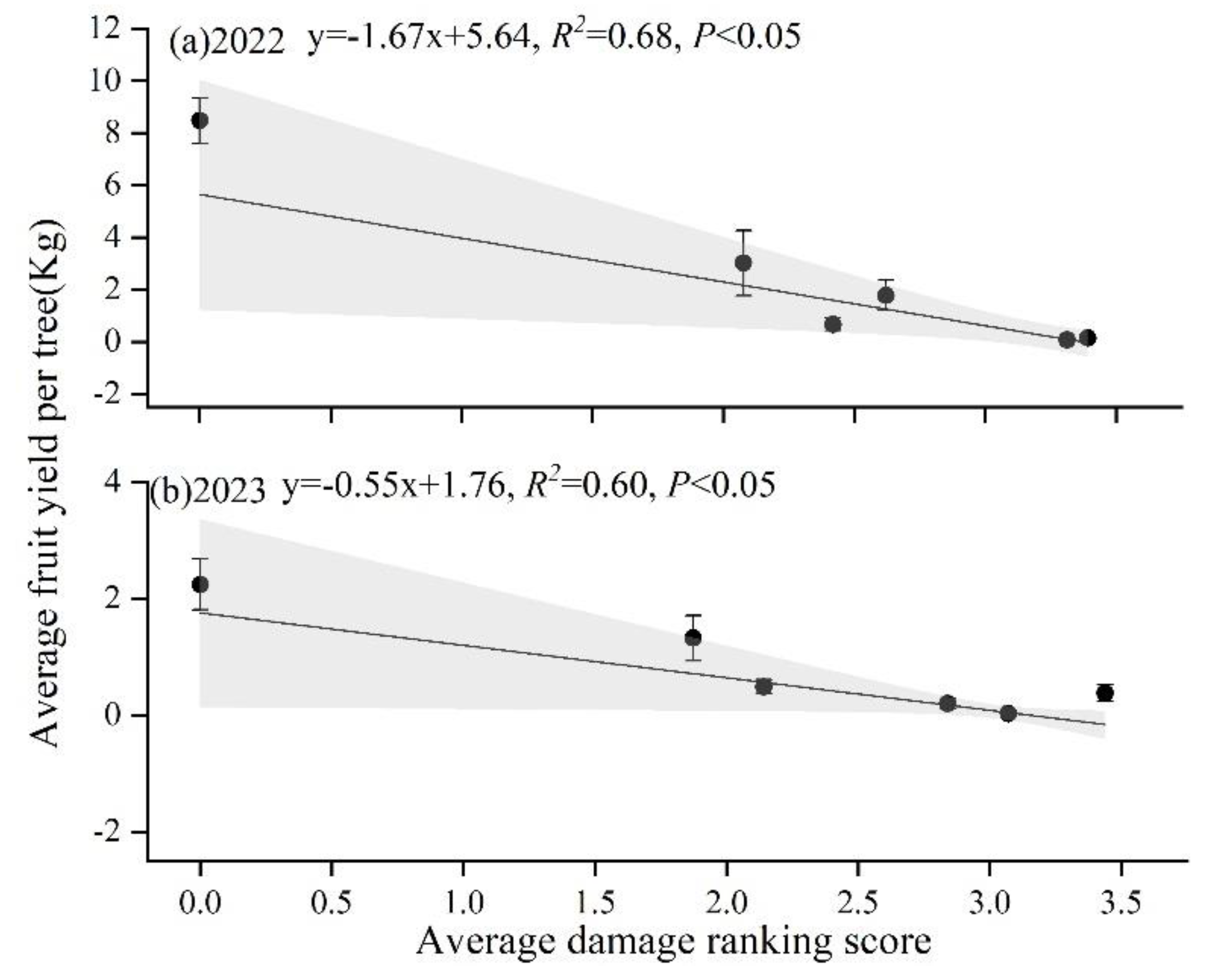

3.5. Fruit Yields Loss

4. Discussion

4.1. GS Population Development and Damage on the Wild Apricot Forest

4.2. The Effect of GS on the Growth of Wild Apricots

4.3. The Effect of GS on the Reproductive Capacity of Wild Apricots

4.4. Integrated Management Approach to GS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, D.; Miller, G.; Hodges, G.S.; Davidson, J.A. Introduced scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) of the United States and their impact on U.S. agriculture. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Washington, 2004, 107, pp.123–158. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, M.; Denno, B.; Miller, D.; Miller, G.; Ben-Dov, Y.; Hardy, N. ScaleNet: a literature-based model of scale insect biology and systematics. Database (Oxford). 2016, bav118, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Amouroux, P.; Crochard, D.; Germain, J.F.; Correa, M.; Ampuero, J.; Groussier, G.; Kreiter, P.; Malausa, T.; Zaviezo, T. Genetic diversity of armored scales (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) and soft scales (Hemiptera: Coccidae) in Chile. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumphy, C.; Hamilton, M.; Manco, B.N.; Green, P.; Sanchez, M.; Corcoran, M.; Salamanca, E. Toumeyella parvicornis (Hemiptera: Coccidae), causing severe decline of Pinus caribaea var. Bahamensis in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Fla. Entomol 2012, 95, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sora, N.; Contarini, M.; Rossini, L.; Turco, S.; Brugneti, F.; Metaliaj, R.; Vejsiu, I.; Peri, L.; Speranza, S. First report of Toumeyella parvicornis (Cockerell) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) in Albania and its potential spread in the coastal area of the Balkans. Bull. OEPP 2024, 54, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, R.; De Masi, L.; Migliozzi, A.; Calandrelli, M.M. Analysis of dieback in a coastal pinewood in Campania, Southern Italy, through High-Resolution Remote Sensing. Plants 2024, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Linghu, W.; Gao, G. Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Coccidae), a new pest in wild fruit forests, Xinjiang. Forest Research 2021, 34, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Çiftçi, Ü.; Bolu, H. First records of Coccomorpha (Hemiptera) species in Diyarbakır, Turkey. J Entomol Sci 2021, 56, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, I.; Japoshvili, G.; Demirozer, O. The chalcid parasitoid complex (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) associated with the globose scale (Sphaerolecanium prunastri Fonscolombe) (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) in Isparta Province, Turkey and some east European countries. J Plant Dis Prot 2003, 110, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülmez, M.; Ülgentürk, S.; Ulusoy, M. Soft scale (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha: Coccidae) species on fruit orchards of Diyarbakır and Elazığ provinces in TürkiyeDiyarbakır ve Elazığ illeri meyve bahçelerindeki Koşnil (Hemiptera:Coccomorpha: Coccidae) türleri. Turk. j. entomol 2023, 47, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgen, i.; Bolu, H. Determination of Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe, 1834) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) plum scale, the distribution, infestations and natural enemies in Malatya province in Turkey. Turk. j. entomol 2009, 33, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bulak, Y.; Yildirim, E. Evaluation of hosts and distribution of Hyalopterus pruni (Geoffroy, 1762) and Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe, 1834), which are pests of fruit trees in Iğdır. International conference on food, agriculture and animal sciences, Sivas,Turkey, 27-29 April 2023.

- Japoshvili, G.; Ay, R.; Karaca, I.; Gabroshvili, N.; Barjadze, S.; Chaladze, G. Studies on the parasitoid complex attacking the globose scale Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Fonscolombe) (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) on prunus species in Turkey. J. Kans. Entomol. Soc 2009, 81, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hai, Y.; Mohammat, A.; Tang, Z.; Fang, J. Community structure and conservation of wild fruit forests in the IIi Valley, Xinjiang. Arid Zone Res 2011, 28, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linghu, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, G. The effects of globose scale (Sphaerolecanium prunastri) infestation on the growth of wild apricot (Prunus armeniaca) trees. Forests 2023, 14, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Linghu, W.; Wang, Q.; Gao, G. Occurrence and harm of Sphaerolecanium prunastri in wild fruit forests in Xinjiang. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2022, 59, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, Y. Primary research on generative biological characteristics of wild apricot(Armeniaca vulgaris Lam.) in Xinjiang. Master, Xinjiang Agriculture University, Xinjiang, 2009.

- You, L.; Chen, G.; Liu, L.; Jie, G.; Liao, K. Dynamics and correlation analysis of growth and development of root system and above -ground part of Armeniaca vulgaris Lam. Xinyuan wild fruit forest. J. Xinjiang Agric. Univ. 2019, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Durovic, G.; Ülgentürk, S. Description of plum scale immatures stages (Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe) (Hemiptera: Coccidae). YYU J AGR SCI 2021, 31, 982–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Deng, B.; Ahmad, M.; Zalucki, M.P.; Gao, G.; Lu, Z. Harmonia axyridis (Boyer de Fonscolombe) (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) as a potential biological control agent of the invasive soft scale, Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe) (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) in native wild apricot forests. Egypt J Biol Pest Control 2024, 34, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirao, L.; Huang, L.; Zhao, W.; Yao, Y. A new species of the genus Coccophagus (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) associated with Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) from the Tianshan Mountains, Xinjiang. Entomotaxonomia 2022, 44, 228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, N.; ZHao, Q.; Hu, H. Research of parasitoids of Sphaerolecanium prunastri fonscolombe in the western Tianshan wild fruit forest. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2024, 61, 971–983. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Biology of Sphaerolecanium prunastri and its control by dominant natural enemy in the wild fruit forest in Yili Master, Xinjiang Agriculture University, Xinjiang, 2021.

- Park, Y.S.; Chung, Y.J. Hazard rating of pine trees from a forest insect pest using artificial neural networks. For. Ecol. Manag 2006, 222, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, A.A.; Çalışkan, O. Fruit set and yield of apricot cultivars under subtropical climate conditions of Hatay, Turkey. Agric. Sci. Technol 2014, 16, 863–872. [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino, A.; Lops, F.; Disciglio, G.; Lopriore, G. Effects of plant biostimulants on fruit set, growth, yield and fruit quality attributes of ‘Orange rubis’ apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) cultivar in two consecutive years. Sci. Hortic 2018, 239, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Gong, X.; Duan, C.; Zhang, C.; Chenyang, M.; Han, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, G. Water-and carbon-related physiological mechanisms underlying the decline of wild apricot trees in Ili, Xinjiang, China. Chin. J. Plant Ecol 2024, 48, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin, P. Mechanisms of tolerance to herbivore damage:what do we know? Evol. Ecol 2000, 14, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.V.; Sullivan, J.J. The impact of herbivory on plants in different resource conditions: a meta-analysis. Ecology 2001, 82, 2045–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.T.; Kruger, E.L.; Lindroth, R.L. Variation in tolerance to herbivory is mediated by differences in biomass allocation in aspen. Funct Ecol 2008, 22, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, E.L.; Lanta, V.; Kozlov, M.V. Effects of sap-feeding insect herbivores on growth and reproduction of woody plants: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Oecologia 2010, 163, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilley, B.; Davies, D.; Glass, T.; Bond, A.; Ryan, P. Severe impact of introduced scale insects on Island Trees threatens endemic finches at the Tristan da Cunha archipelago. Biol. Conserv 2020, 251, 108761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.C.; Whitham, T.G. Competition between gall aphids and natural plant sinks: plant architecture affects resistance to galling. Oecologia 1997, 109, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda-King, L.; Gómez, S.; Martin, J.L.; Orians, C.M.; Preisser, E.L. Tree responses to an invasive sap-feeding insect. Plant Ecol 2014, 215, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Guo, C.; Jiang, N.; Tang, Y.; Zhen, F.; Wang, J.; Liao, K.; Liu, L. Characteristics and spatial distribution pattern of natural regeneration young plants of Prunus armeniaca in Xinjiang, China. Chin. J. Plant Ecol 2023, 47, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linghu, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, G. Effects of pruning time and intensity on the population density of Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe) and growth of Armeniaca vulgaris Lamarck. Northern Horticulture 2021, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Yanlong, Z.; Xu, H.; Jashenko, R.; Dong, Z.; Zalucki, M.; Lu, Z. Pruning can recover the health of wild apple forests attacked by the wood borer Agrilus mali in central Eurasia. Entomol Gen 2024, 44, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| County | Survey site | Plot number | Latitude (N) | Longitude € | Altitude (m) | Height (m) | DBH (cm) | Wild apricot trees density (number /ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gong liu | Kuolesai | 1 | 43.234 | 82.811 | 1248.10 | 7.93±0.35 | 21.81±1.48 | 224 |

| 2 | 43.259 | 82.857 | 1343.23 | 7.28±0.40 | 13.57 ±1.68 | 248 | ||

| 3 | 43.248 | 82.697 | 1190.32 | 8.28±0.24 | 23.78±1.73 | 264 | ||

| Jinqikesai | 1 | 43.248 | 82.857 | 1321.14 | 7.79±0.37 | 22.2±2.52 | 288 | |

| 2 | 43.246 | 82.857 | 1343.23 | 7.94±0.43 | 21.96±1.5 | 240 | ||

| 3 | 43.248 | 82.858 | 1319.34 | 7.25±0.44 | 15.57±1.56 | 312 | ||

| Keersenbulake | 1 | 43.363 | 82.120 | 1252.33 | 6.30±0.41 | 18.26±1.36 | 264 | |

| 2 | 43.349 | 82.298 | 1237.30 | 8.31±0.51 | 17.50±1.71 | 232 | ||

| 3 | 43.349 | 82.299 | 1211.59 | 8.05±0.70 | 15.92±0.98 | 240 | ||

| Xiaomohuer | 1 | 43.178 | 82.733 | 1376.60 | 8.02±0.26 | 27.99±0.88 | 176 | |

| 2 | 43.141 | 82.442 | 1245.00 | 9.49±0.45 | 22.25±1.29 | 264 | ||

| 3 | 43.177 | 82.733 | 1356.96 | 6.33±0.57 | 27.52±1.35 | 152 | ||

| Xin yuan | Tuergeng | 1 | 43.561 | 83.482 | 1026.33 | 6.05±0.56 | 19.98±2.02 | 360 |

| 2 | 43.560 | 83.401 | 1110.72 | 6.24±0.61 | 26.6±3.37 | 288 | ||

| 3 | 43.539 | 83.485 | 1055.23 | 7.54±0.95 | 19.92±2.90 | 264 | ||

| Talede | 4 | 43.338 | 83.039 | 1165.06 | 6.77±0.51 | 20.94±1.37 | 240 | |

| Huo cheng | Xiaoxigou | 1 | 44.380 | 80.818 | 1084.52 | 5.72±0.47 | 27.17±1.74 | 208 |

| 2 | 44.429 | 80.832 | 1160.95 | 5.62±0.22 | 25.37±1.70 | 216 | ||

| 3 | 44.394 | 80.814 | 1051.36 | 6.39±0.22 | 18.57±1.25 | 232 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).