Submitted:

07 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

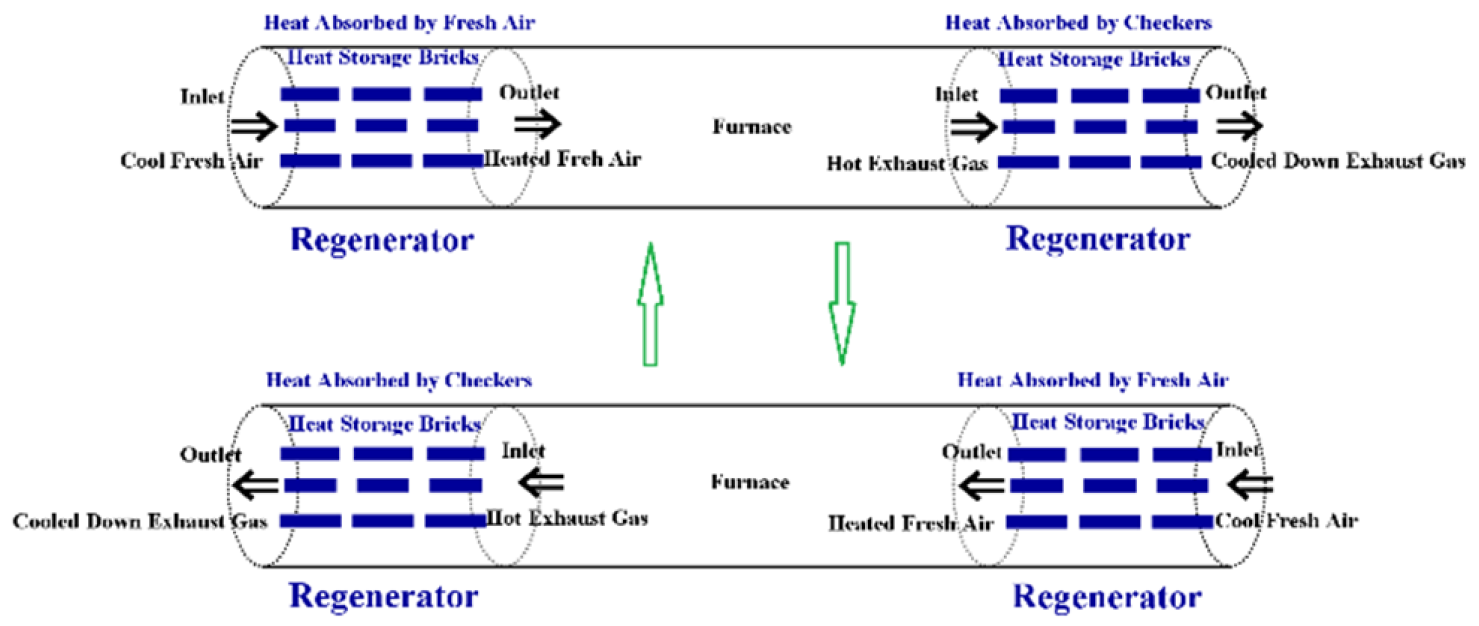

2. Materials and Methods

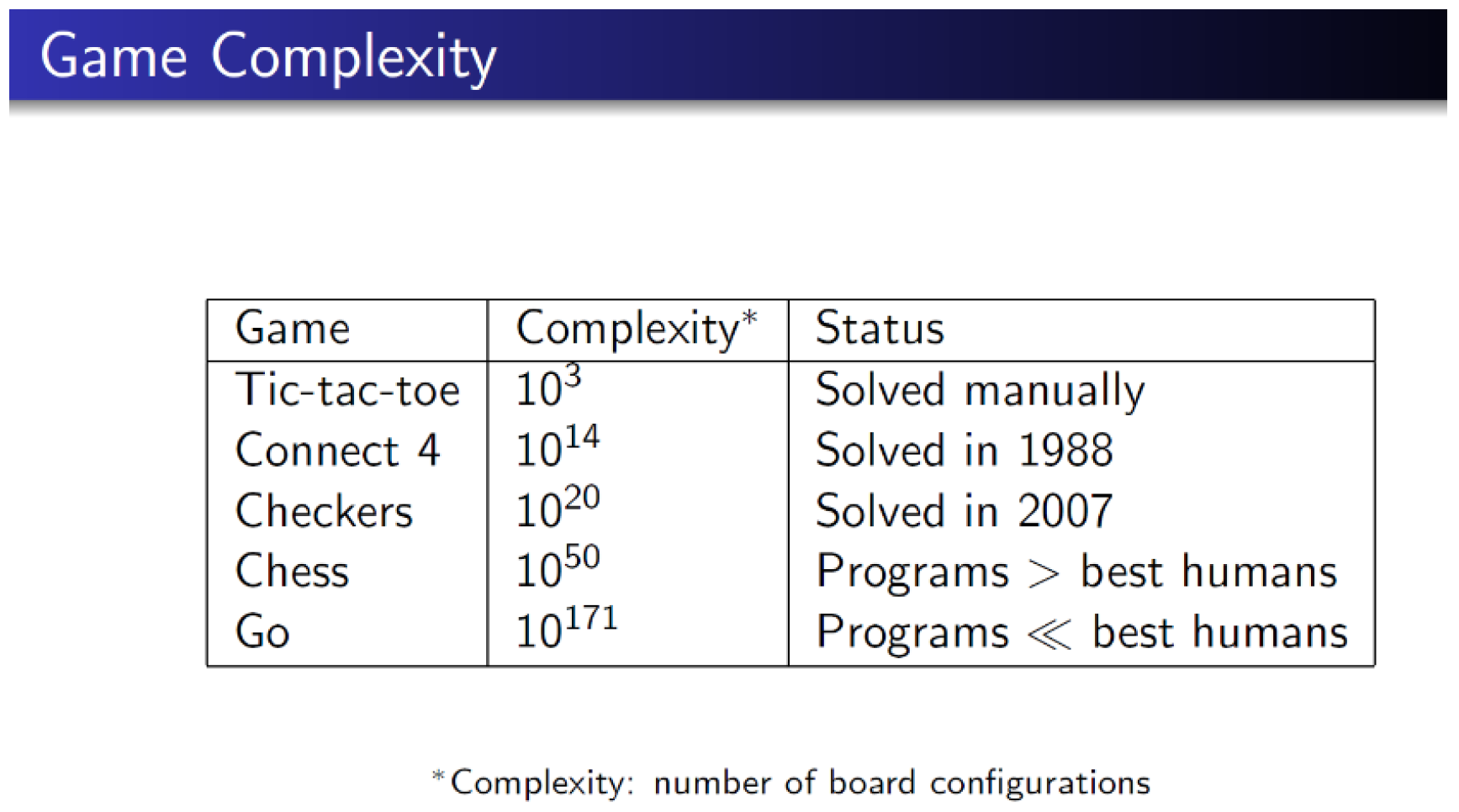

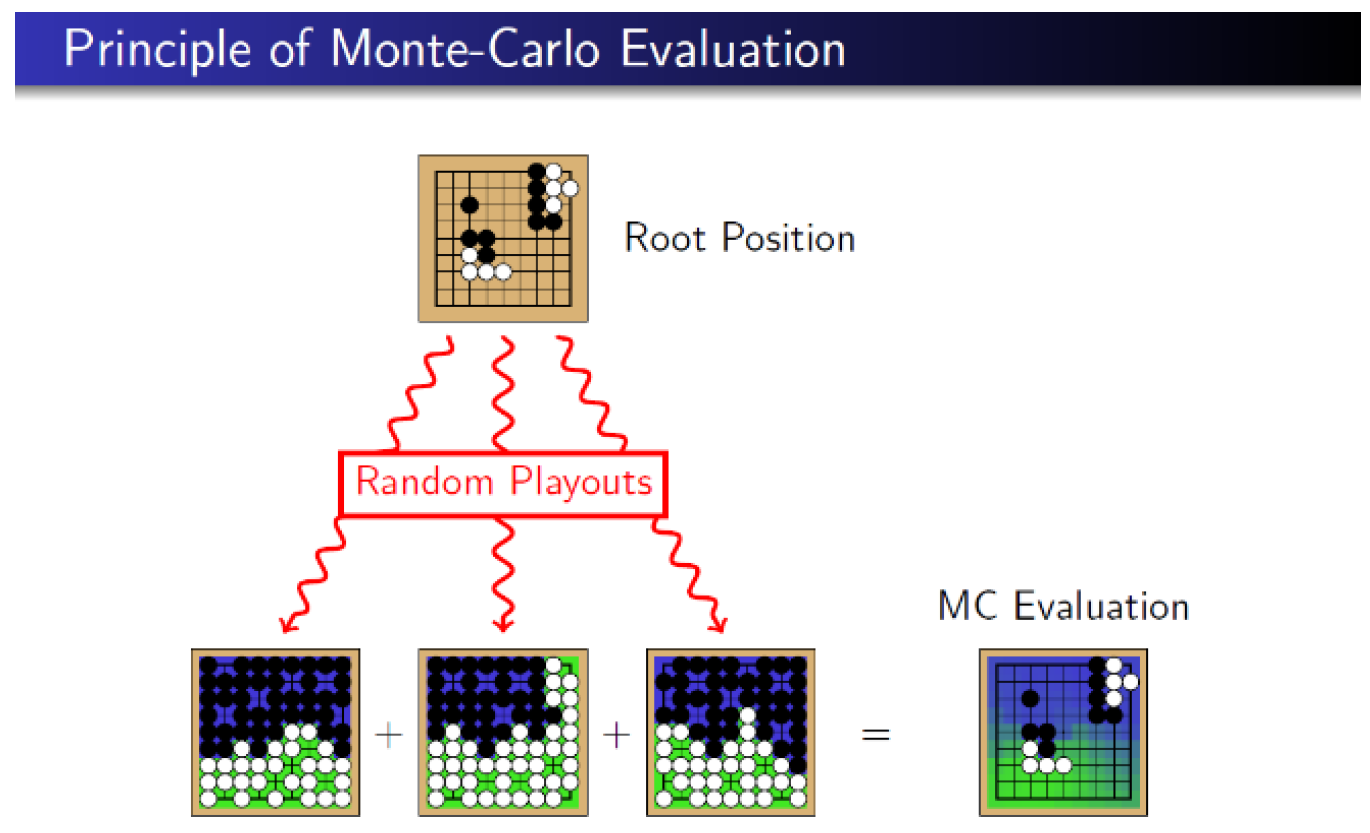

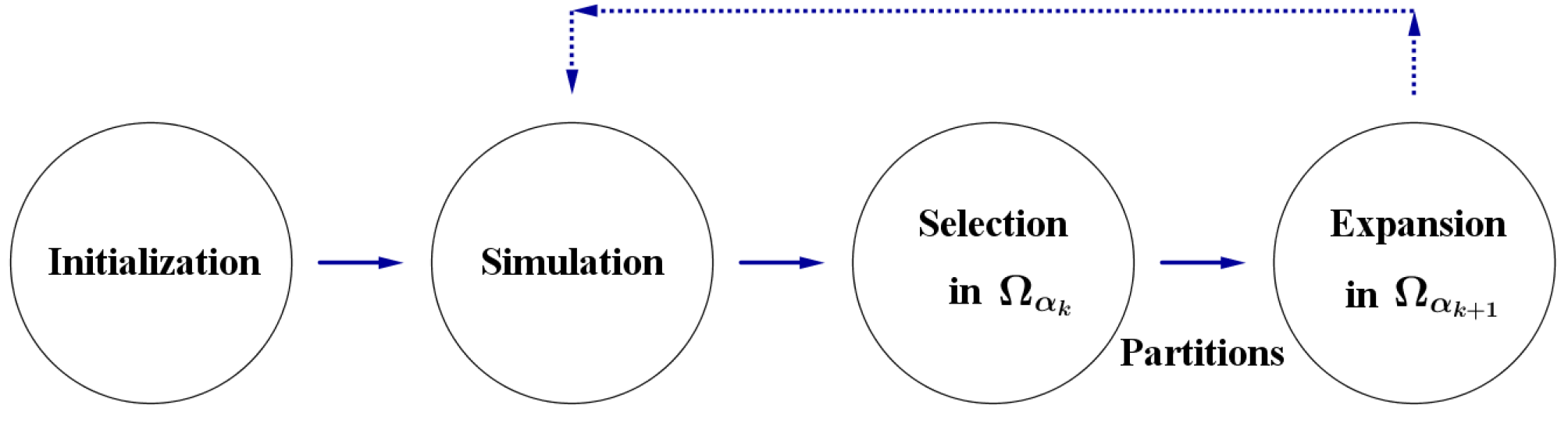

2.1. Tree Search by the Monte-Carlo Method

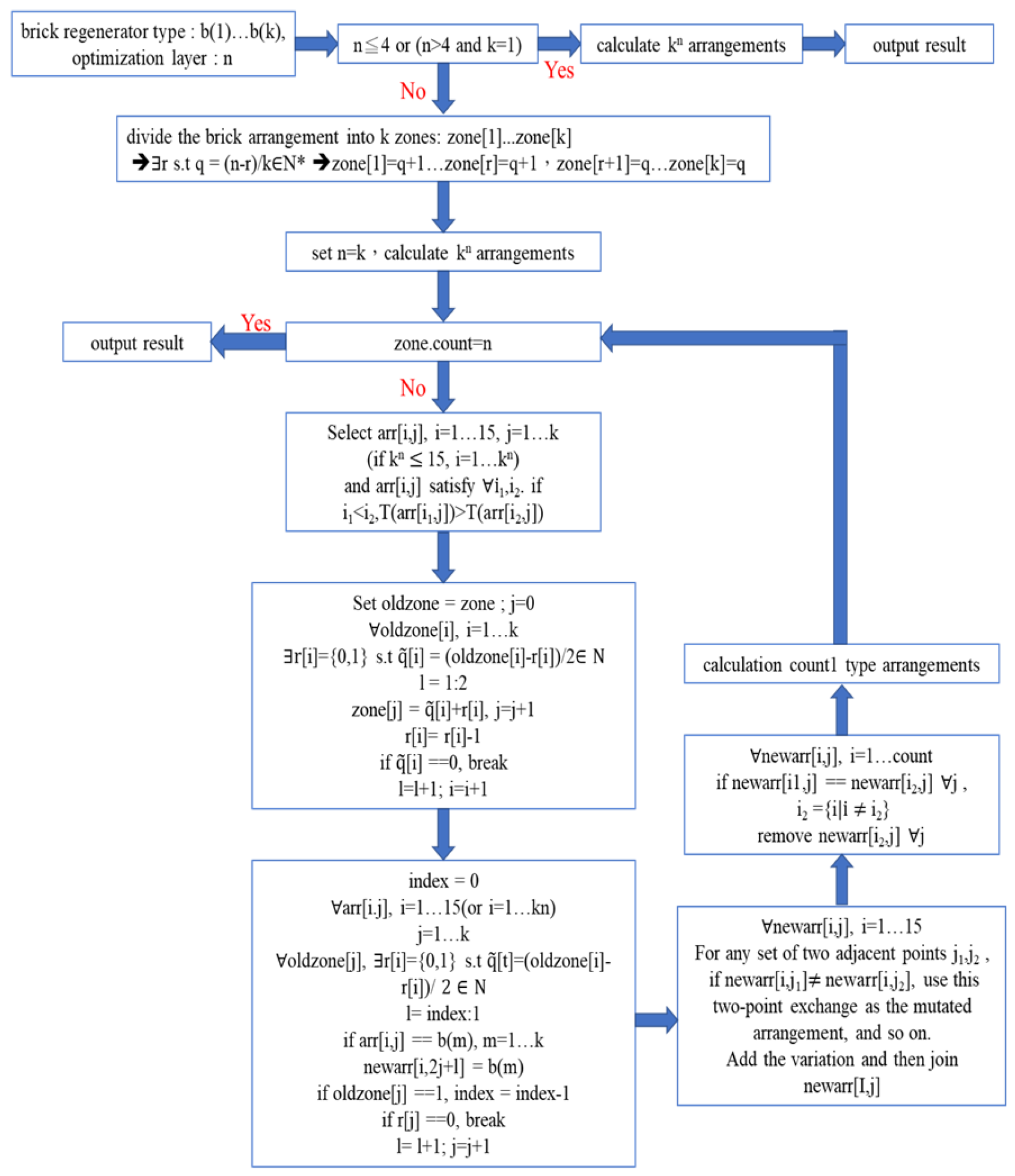

2.2. Our Simple Tree Search Method

2.3. The Expansion Operators

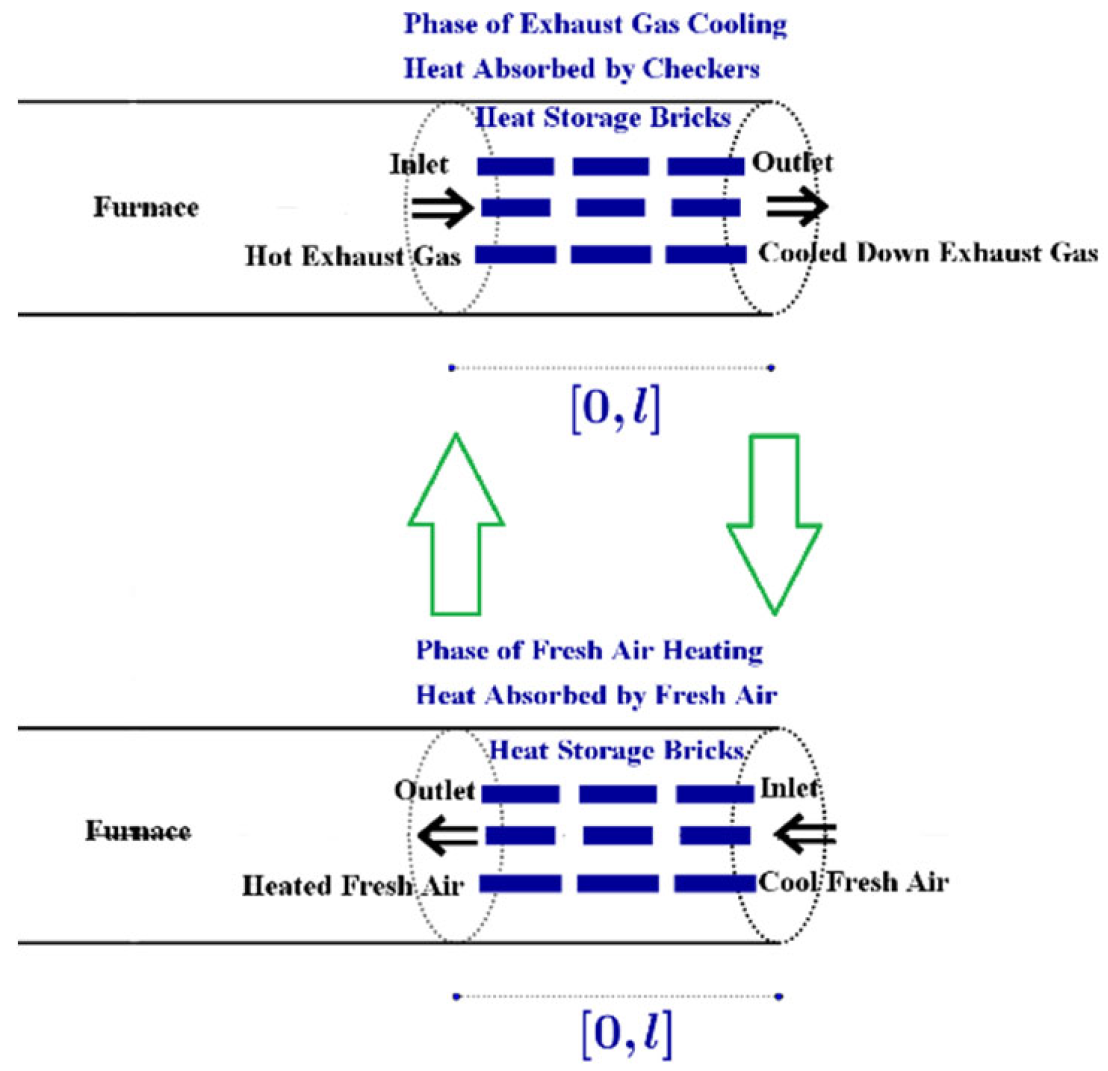

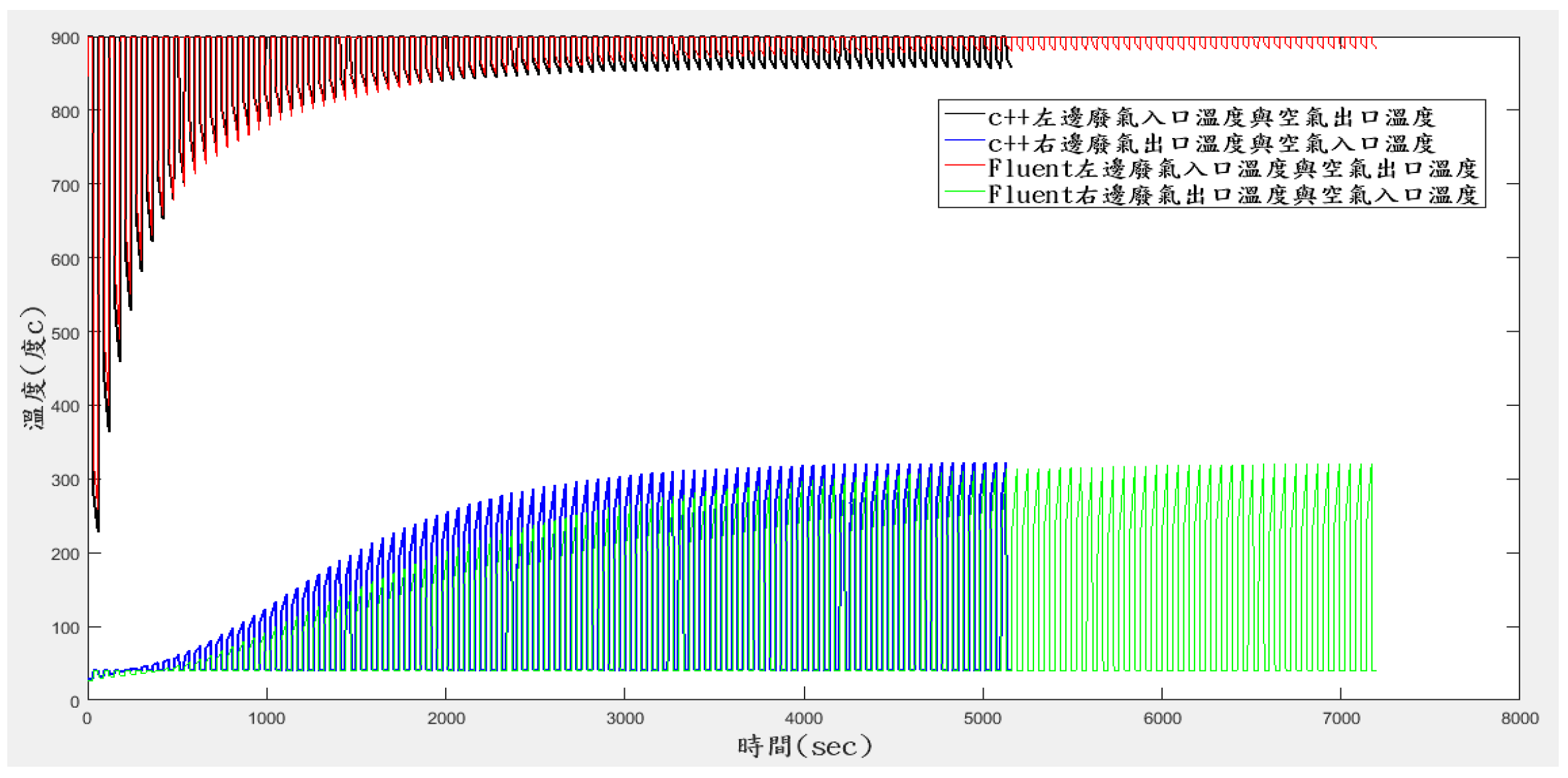

2.4. The Numerical Simulation Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- N. Metropolis, N.; Ulam, S. The Monte Carlo Method. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1949, 44, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrell, G. Mathematical Statistics: A Unified Introduction; Springer-Verlag, New-York, Inc., 1999.

- DeGroot, M; Schervish, M. Probability and Statistics; Pearson Education, Inc., 2012.

- Roe, B. Probability and Statistics in the Physical Sciences; Springer Nature, Switzerland AG, 2020.

- Ito, K.; McKean, H. P., Jr. Diffusion Processes and Their Sample Paths; Springer-Verlag, New York, 1965.

- Ito, K.; Watanabe, S. Transformation of Markov Processes by Multiplicative Functionals. J. Math. Kyoto Univ. 1965, 4, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F.; Scholes, M. The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities. Journal of Political Economy. 1973, 81, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, B. The Expected-Outcome Model of Two-Player Games; Technical Report, Department of Computer Science, Columbia University, 1987.

- Brügmann, B. Monte Carlo Go; Technical report, Department of Physics, Syracuse University, 1993.

- Coulom, R. Efficient Selectivity and Backup Operators in Monte Carlo Tree Search; International conference on computers and games,72-83, Springer, 2006.

- Kocsis,L.; Szepesvári, C. Bandit based Monte Carlo planning; Proceedings of the 17th European conference on machine learning, ECML’06, 282-293, Springer, Berlin, 2006.

- Chaslot, G.M.J.B.; Winands, M.H.M.; Uiterwijk, J.W.H.M.; van den Herik, H.J.; Bouzy, B. Progressive Strategies for Monte-Carlo Tree Search. New Mathematics and Natural Computation. 2008, 4, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazenave, T.; Jouandeau, N. On the parallelization of UCT; Computer Games Workshop, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 93-101, 2007.

- Cazenave, T.; Jouandeau, N. A parallel Monte-Carlo Tree Search algorithm; International conference 19 on computers and games, Springer, 72-80, 2008.

- Gelly, S.; Wang, Y. Exploration Exploitation in Go: UCT for Monte-Carlo Go; Neural Information 19, Processing Systems Conference on Line Trading of Exploration and Exploitation Workshop, Canada, 2006.

- Gelly, S.; Silver, D. Monte-Carlo Tree Search and Rapid Action Value Estimation in Computer Go. Artificial Intelligence. 2011, 175, 1856–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelly, S.; Kocsis, L.; Schoenauer, M.; Sebag, M.; Silver, D.; Szepesvári, C.; Teytaud, O. The Grand Challenge of Computer Go: Monte-Carlo Tree Search and Extensions. Communications of the ACM. 2012, 55, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Sutton, R. S.; Müller, M. Temporal-Difference Search in Computer Go. Machine Learning. 2012, 87, 183–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, G.; Driessens, K.; Ramon, J. Monte-Carlo Tree Search in Poker Using Expected Reward Distributions; Asian Conference on Machine Learning, Springer, 367-381, 2009.

- Robles. D.; Rohlfshagen, P.; Lucas, S. M. Learning Non-Random Moves for Playing Othello: Improving Monte-Carlo Tree Search; 2011 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG’11), IEEE, 305-312, 2011.

- Arneson, B.; Hayward, R. B.; Henderson, P. Monte-Carlo tree search in Hex. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games. 2010, 2, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winands, M. H.; Bjornsson, Y.; Saito, J. T. Monte-Carlo Tree Search in Lines of Action. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games. 2010, 2, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teytaud, F.; Teytaud, O. Creating an Upper-Confidence-Tree Program for Havannah; Advances in Computer Games, Springer, 65-74, 2010.

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C. J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; Dieleman, S.; Grewe, D.; Nham, J.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Sutskever, I.; Lillicrap, T.; Leach, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Graepel, T.; Hassabis, D. Mastering the Game of Go with Deep Neural Networks and Tree Search. Nature. 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science News Staff. From AI to protein folding: Our Breakthrough Runners-up; Science, 22 December 2016.

- Coulom, R. The Monte-Carlo Revolution in Go; Japanese-French Frontiers of Science Symposium, 2008. Available online: https://www.remi-coulom.fr/JFFoS/JFFoS.pdf.

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; Chen, Y.; Lillicrap, T.; Hui, F.; Sifre, L.; van den Driessche, G.; Thore, T.; Hassabis, D. Mastering the Game of Go without Human Knowledge. Nature. 2017, 550, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, D.; Hubert, T.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I. Lai, M.; Guez, A.; Lanctot, M.; Sifre, L.; Kumaran, D; Graepel, T.; Lillicrap, T.; Simonyan, K.; Hassabis, D. A General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm That Masters Chess, Shogi, and Go through Self-Play. Science. 2018, 362, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, L.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y. Learning the Game of Go by Scalable Network without Prior Knowledge of Komi. IEEE Transactions on Games. 2020, 12, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaina, R. D.; Perez-Liebana, D.; Lucas, S.M.; Sironi, C. F.; Winands, M. H. Self-Adaptive Rolling Horizon Evolutionary Algorithms for General Video Game Playing; 2020 IEEE Conference on Games, IEEE, 367–374, 2020.

- Gaina, R. D.; Devlin, S.; Lucas, S. M.; Perez, D. Rolling Horizon Evolutionary Algorithms for General Video Game Playing. IEEE Transactions on Games. 2021, 14, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segler, M. H.; Preuss, M.; Waller, M. P. Planning Chemical Syntheses with Deep Neural Networks and Symbolic AI. Nature. 2018, 555, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Soman, R. K.; Han, J.; Whyte, J. K. Addressing adjacency Constraints in Rectangular Floor Plans using Monte-Carlo Tree Search. Automation in Construction. 2020, 115, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucairol, M.; Georgiou, A.; Cazenave, T.; Prischi, F.; Pardo, O. E. DrugSynthMC: An Atom-Based Generation of Drug-like Molecules with Monte Carlo Search. Journal of Chemical Information and Modelling. 2024, 64, 7097–7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misono, N.; Hirosawa, T.; Sato, Y.; Matsumoto, H. Two-Step Monte Carlo Tree Search for Optimal Design of High-Frequency Toroidal Inductors in Power Electronics Circuits. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 2025, 61, 8400105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świechowski, M.; Godlewski, K.; Sawicki, B.; Mańdziuk, J. Monte Carlo Tree Search: a Review of Recent Modifications and Applications. Artificial Intelligence Review. 2023, 56, 2497–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaat, A. Deep Reinforcement Learning; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2022.

- Storn, R.; Price, K.V. Differential Evolution: A Practical Approach to Global Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hang, Q. Differential Evolution with Composite Trial Vector Generation Strategies and Control Parameters. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2011, 15, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, M.; Sallam, E.A.; Fahmy, M.M. An Enhanced Differential Evolution Optimization Algorithm; Proceedings of the 2014 Fourth International Conference on Digital Information and Communication Technology and its Applications (DICTAP), Bangkok, Thailand, 6–8 May 2014.

- Chen, T.-J.; Hong, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, J.-Y. Optimization on Linkage System for Vehicle Wipers by the Method of Differential Evolution. Applied Sciences. 2023, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelio, M.; Morrone, P. Numerical Evaluation of the Energetic Performances of Structured and Random Packed Beds in Regenerative Thermal Oxidizers. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2007, 27, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, P.; Díez, F.V.; Ordóñez, S. Reverse Flow Reactors as Sustainable Devices for Performing Exothermic Reactions: Applications and Engineering Aspects. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification. 2019, 135, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuntini, L.; Bertei, A.; Tortorelli, S.; Percivale, M.; Paoletti, E.; Nicolella, C.; Galletti, C. Coupled CFD and 1-D Dynamic Modeling for the Analysis of Industrial Regenerative Thermal Oxidizers. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification. 2020, 157, 108117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinehkafsh, M.T.; Sadrameli, S.M. Simulation of Fixed Bed Regenerative Heat Exchangers for Flue gas Heat Recovery. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2004, 24, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, M.; Fan, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, G. Study on Performance of the Ball Packed-Bed Regenerator: Experiments and Simulation. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2002, 22, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwa, R. Heat and Mass Transfer; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2020.

- Incropera, F. P.; DeWitt, D. P.; Bergman, T. L. Principles of Heat and Mass Transfer; John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

- Yu, Y.-L.; Chen, T.-J.; Chung, S.-C.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Hong, Y.-J. A Study on the Numerical Simulation for the Heat Trans-fer Process of Regenerative Heat Chamber with Heat Storage Brick; International Stirling Engine Conference, Tainan,Taiwan, 2018.

- Chung, S.-C.; Chen, T.-J.; Yu, Y.-L.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C. A Study on the Mathematical Model for the Heat Transfer Process of Regenerative Heat Chamber With Heat Storage; the 12th Pacific Symposium on Flow Visualization and Image Processing PSVIP12, Taiwan, 2019.

- Syu, W.-J. Numerical Simulation Analysis of High Temperature Heat Exchange Module; Master Thesis, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, 2017.

- Nield, D. A.; Bejan, A. Convection in Porous Media; Springer International Publishing AG, 2017.

| Cordierite | Mullite | |

| size | 150×150×100 | 150×150×100 |

| pore size | 4.9 | 3.0 |

| wall thickness | 1.04 | 0.70 |

| porosity | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| specific surface area | 501 | 853 |

| density | 2200 | 2500 |

| specific heat capacity | 1000 | 1200 |

| thermal conductivity | 2 | 2 |

| Mullite A | Mullite B | Mullite C | |

| size | 100×100×100 | 150×150×100 | 150×150×100 |

| pore size | 17 | 4 | 6 |

| wall thickness | 0.8 | 1.5 | 2 |

| porosity | 0.182 | 0.524 | 0.524 |

| specific surface area | 42.7 | 523.8 | 349.2 |

| density | 2200 | 2200 | 2200 |

| specific heat capacity | 836 | 836 | 836 |

| thermal conductivity | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Total horizontal length of stacking | 200 |

| Total vertical length of stacking | 300 |

| Natural gas flow | 17.65 |

| Air-fuel ratio | 15.9 |

| Inlet temperature of exhaust gas | 1050 (Experiment 1) 1150 (Experiment 2) |

| Inlet temperature of fresh air | 313 |

| Time of Phase Switch | 30 |

| Rank | Arrangements of checkers | Inlet temperature of exhaust gas (℃) | Outlet temperature of exhaust gas (℃) | Waste Heat Recovery Ratio (%) |

| 1 | 886.82 | 264.67 | 67.88 | |

| 2 | 886.28 | 286.82 | 65.82 | |

| 3 | 885.82 | 259.48 | 63.77 |

| Rank | Arrangements of checkers | Inlet temperature of exhaust gas (℃) | Outlet temperature of exhaust gas (℃) | Waste Heat Recovery Ratio (%) |

| 1 | 886.82 | 264.67 | 67.88 | |

| 9 | 885.14 | 284.35 | 61.72 | |

| 11 | 885.08 | 286.08 | 60.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).