Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. SEL Impact on Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being

1.2. SEL in Higher Education

SEL in Different Higher Education Fields

1.3. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social and Emotional Competence

2.2.2. Satisfaction with Affective Relationships

2.2.3. Personal Well-Being

2.2.4. Academic Well-Being

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Data Collection

2.3.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Diagnosis

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

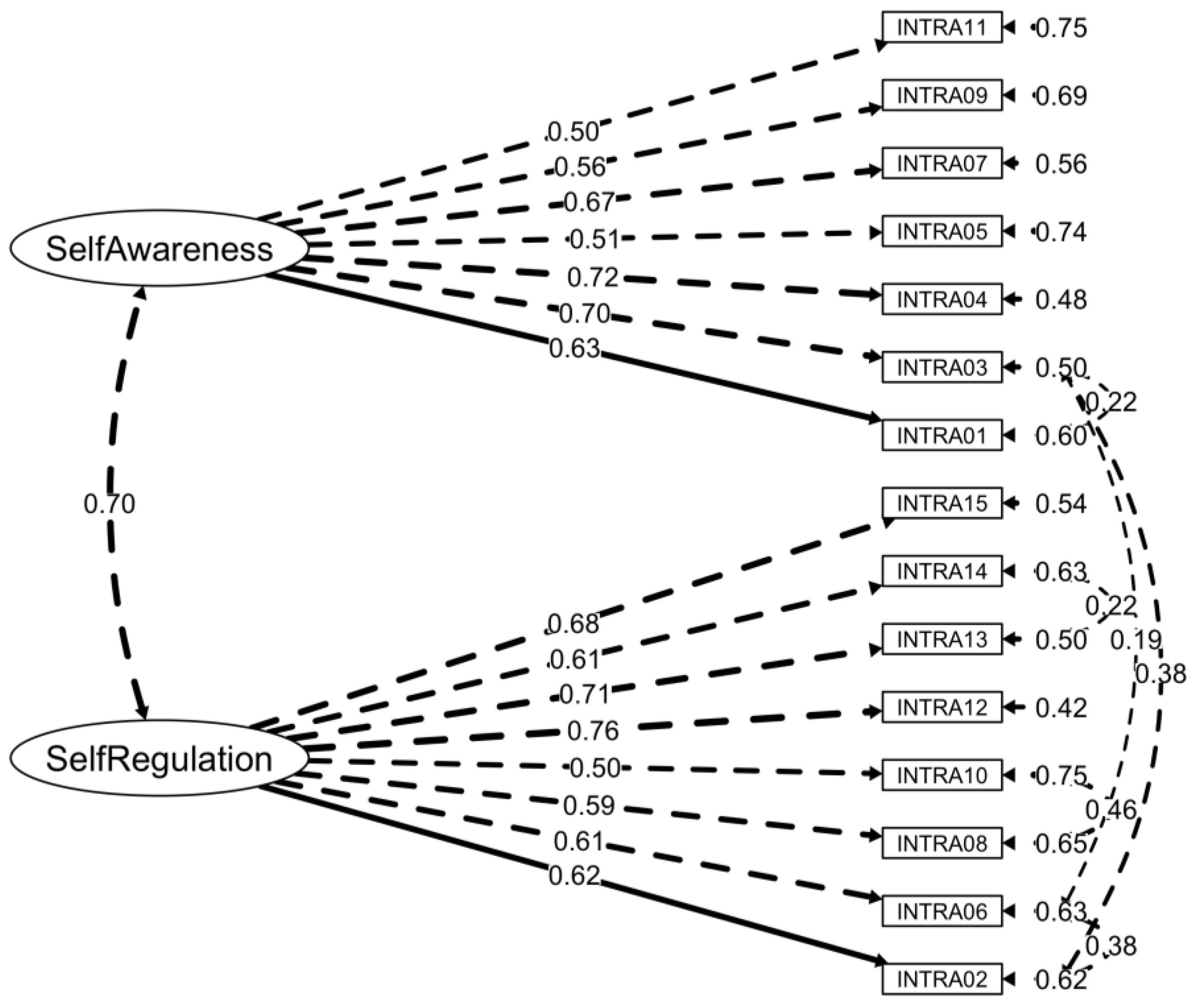

3.2.1. Intrapersonal Competence Questionnaire

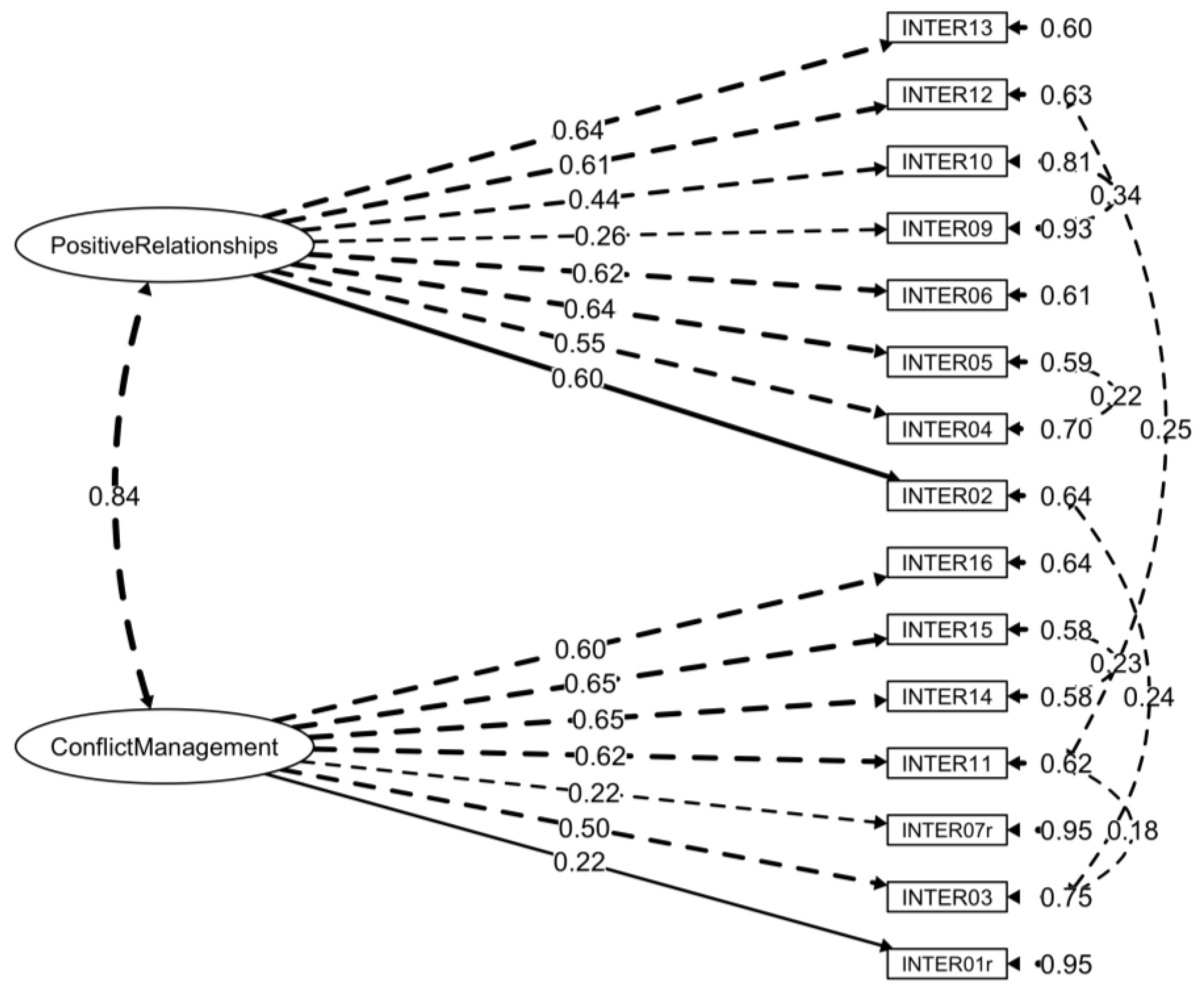

3.2.2. Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire

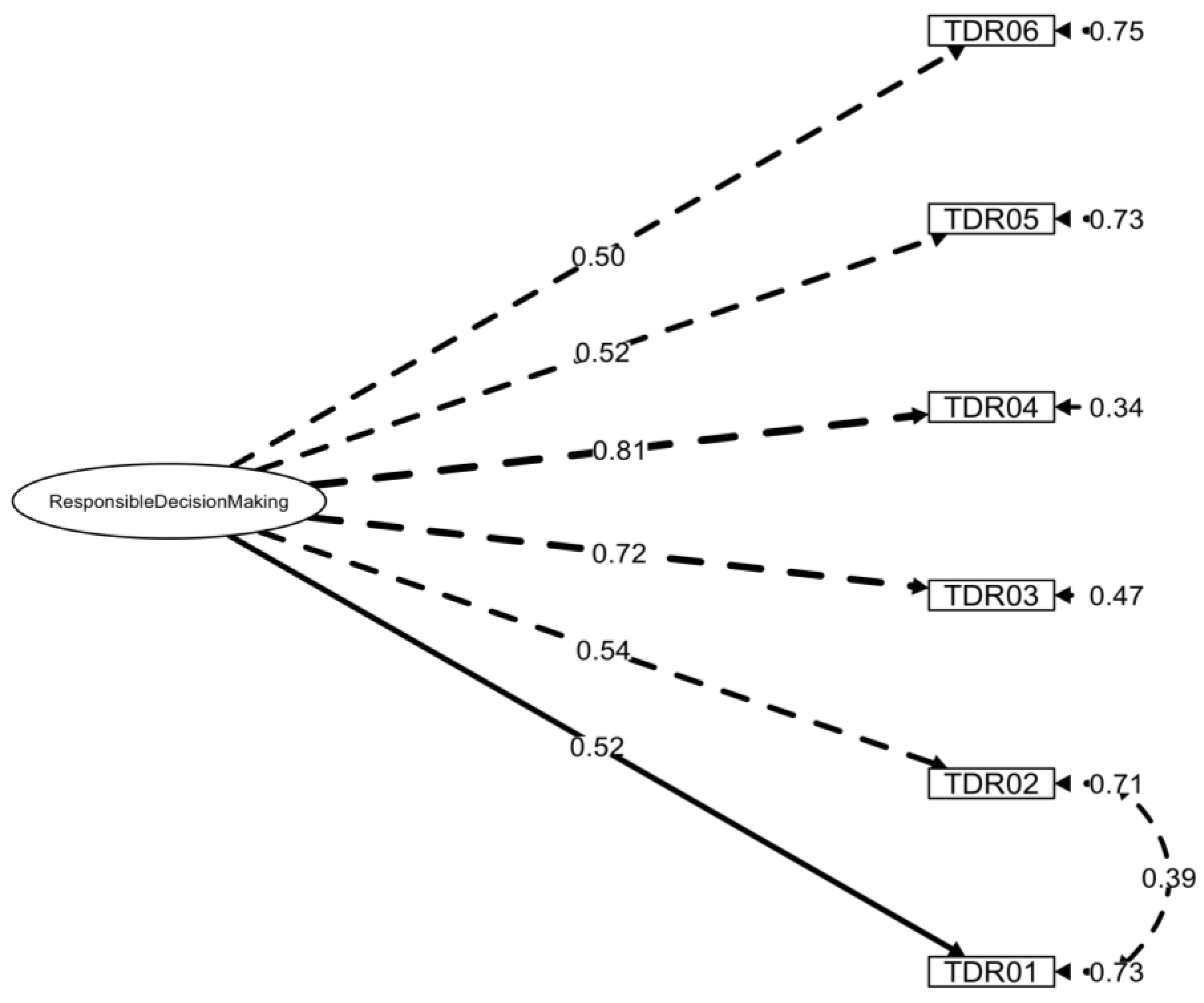

3.2.3. Responsible Decision-Making Competence Questionnaire

3.3. Factorial Invariance Analysis

| Overall Fit Indices | Comparative Fit Indices | ||||||

| Invariance models | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Model comparison |

ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

| Intrapersonal Competence Questionnaire | |||||||

| Gender groups | |||||||

| Configural | 580.85 (166) | .92 | .90 | .06 | _ | _ | _ |

| Metric | 595.35 (179) | .92 | .90 | .07 | Configural | .000 | .003 |

| Scalar | 668.98 (192) | .90 | .89 | .07 | Metric | .014 | .003 |

| Scalar_partial1 | 620.05 (191) | .90 | .89 | .07 | Metric | .009 | .001 |

| Residual | 708.68 (208) | .90 | .90 | .07 | Scalar_partial | .003 | .002 |

| Academic field groups | |||||||

| Configural | 567.33 (166) | .92 | .90 | .06 | _ | _ | _ |

| Metric | 577.77 (179) | .92 | .91 | .07 | Configural | .001 | .003 |

| Scalar | 621.40 (192) | .92 | .91 | .06 | Metric | .007 | .000 |

| Residual | 709.95 (207) | .90 | .90 | .06 | Scalar | .017 | .003 |

| Residual_partial2 | 675.94 (205) | .90 | .90 | .07 | Scalar | .010 | .001 |

| Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire | |||||||

| Gender groups | |||||||

| Configural | 498.13 (166) | .90 | .89 | .06 | _ | _ | _ |

| Metric | 508.47 (179) | .90 | .89 | .06 | Configural | .001 | .003 |

| Scalar | 577.20 (192) | .88 | .86 | .07 | Metric | .019 | .003 |

| Scalar_partial3 | 544.91 (191) | .90 | .89 | .06 | Metric | .008 | .000 |

| Residual | 580.76 (205) | .86 | .86 | .07 | Scalar_partial | .007 | .000 |

| Academic field groups | |||||||

| Configural | 445.57 (166) | .91 | .89 | .08 | _ | _ | _ |

| Metric | 461.95 (179) | .91 | .90 | .07 | Configural | .001 | .002 |

| Scalar | 494.20 (192) | .91 | .90 | .07 | Metric | .007 | .000 |

| Residual | 553.06 (207) | .89 | .89 | .07 | Scalar | .015 | .002 |

| Residual_partial4 | 534.19 (206) | .89 | .89 | .07 | Scalar | .009 | .000 |

| Responsible Decision-Making Competence Questionnaire | |||||||

| Gender groups | |||||||

| Configural | 51.71 (16) | .97 | .95 | .06 | _ | _ | _ |

| Metric | 65.93 (21) | .97 | .95 | .07 | Configural | .008 | .002 |

| Scalar | 82.73 (26) | .97 | .96 | .05 | Metric | .010 | .001 |

| Residual | 100.16 (32) | .96 | .96 | .06 | Scalar | .010 | .001 |

| Academic field groups | |||||||

| Configural | 50.91 (16) | .98 | .96 | .07 | _ | _ | _ |

| Metric | 56.08 (21) | .98 | .97 | .06 | Configural | .000 | .010 |

| Scalar | 65.55 (26) | .97 | .97 | .06 | Metric | .004 | .003 |

| Residual | 76.04 (32) | .97 | .97 | .05 | Scalar | .004 | .003 |

3.4. Reliability, Discriminant and Criterion Validity and Correlation Analysis

| Variables | M(SD) | Ω [95% CI] | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

| 1. Self-awareness | 7.36 (1.34) | .81 [.79, .83] | _ | ||||

| 2. Self-regulation | 6.41 (1.56) | .84 [.83, .87] | .60** | _ | |||

| 3. Conflict management | 7.18 (1.19) | .73 [.69, .75] | .41** | .41** | _ | ||

| 4. Positive relationship | 7.04 (1.36) | .77 [.76, .80] | .56** | .51** | .58** | _ | |

| 5. Responsible decision making | 7.17 (1.38) | .78 [.76, .81] | .54** | .60** | .53** | .64** | _ |

| Variables | Age | Gender | Academic field | KMSS |

| 1. Self-awareness | .13* | -.04 | -.08 | .12* |

| 2. Self-regulation | .27** | -.03 | -.07 | .19* |

| 3. Conflict management | .05 | -.03 | -.07 | .10 |

| 4. Positive relationship | .18* | .05 | -.09 | .14* |

| 5. Responsible decision making | .11 | -.03 | -.06 | .20** |

| Variables | Personal well-being | Academic well-being | ||||

| Emotional | Psychological | Social | Vigor | Dedication | Absorption | |

| 1. Self-awareness | .27** | .43** | .20** | .28** | .27** | .22** |

| 2. Self-regulation | .54** | .67** | .45** | .58** | .53** | .56** |

| 3. Conflict management | .31** | .40** | .28** | .30** | .32** | .34** |

| 4. Positive relationship | .34** | .48** | .33** | .33** | .37** | .33** |

| 5. Responsible decision making | .33** | .46** | .32** | .30** | .40** | .38** |

3.5. Group Differences

3.6. Regression Analysis

3.6.1. Personal Well-Being

3.6.2. Academic Well-Being

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Study Impact

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criteria |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criteria |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DGES | Directorate General for Higher Education |

| HASS-H | Humanities, Arts, Social Sciences, and Health |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SEC | Social and Emotional Competence |

| SECAB-A(S) | Social and Emotional Competence Assessment Battery for Adults – Students Survey |

| SEL | Social and Emotional Learning |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

References

- Addis, M.E.; Mahalik, J.R. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist 2003, 58, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajao, H.; Yeaman, A.; Pappas, J. (2023). Social Emotional Learning in STEM Higher Education: In R. Rahimi & D. Liston (Eds.), Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design (pp. 173–190). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, N.; Vieira-Santos, S.; Roberto, M.S.; Francisco, R.; Pedro, M.F.; Ribeiro, M.-T. Portuguese Version of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale: Preliminary Psychometric Properties. Marriage & Family Review 2021, 57, 647–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. (2009). Amos 18 user’s guide. SPSS Inc.

- Arnett, J.J. (2018). Conceptual Foundations of Emerging Adulthood. In J. L. Murray & J. J. Arnett (Eds.), Emerging Adulthood and Higher Education (1st ed., pp. 11–24). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Aust, F.; Diedenhofen, B.; Ullrich, S.; Musch, J. Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behavior Research Methods 2013, 45, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.B.; Tang, C.S.; Kennedy, G. (2022). Teaching for quality learning at university (Fifth edition). Open University Press, McGraw Hill.

- Blackburn, H. The Status of Women in STEM in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature 2007–2017. Science & Technology Libraries 2017, 36, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural Equations with Latent Variables (1st ed.). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with Amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (Third edition). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Cameron, R.B.; Rideout, C.A. ‘It’s been a challenge finding new ways to learn’: First-year students’ perceptions of adapting to learning in a university environment. Studies in Higher Education 2022, 47, 668–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.; Blank, L.; Cantrell, A.; Baxter, S.; Blackmore, C.; Dixon, J.; Goyder, E. Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J.R.; Castro-López, A.; Bernardo, A.B.; Almeida, L.S. The Dropout of First-Year STEM Students: Is It Worth Looking beyond Academic Achievement? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefai, C.; Bartolo, P.A.; Cavioni, V.; Downes, P. (2018). Strengthening Social and Emotional Education as a core curricular area across the EU: A review of the international evidence. NESET II report. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/664439.

- Cipriano, C.; Strambler, M.J.; Naples, L.H.; Ha, C.; Kirk, M.; Wood, M.; Sehgal, K.; Zieher, A.K.; Eveleigh, A.; McCarthy, M.; Funaro, M.; Ponnock, A.; Chow, J.C.; Durlak, J. The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: A contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Development 2023, 94, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (0 ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Conley, C.S. (2015). SEL in higher education. In Joseph A. Durlak, Celene E. Domitrovich, R.P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (1st ed., pp. 197–212). The Guilford Press.

- Costa, R.C. The place of the humanities in today’s knowledge society. Palgrave Communications 2019, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, R.; Peters, G.-J.Y. Scale quality: Alpha is an inadequate estimate and factor-analytic evidence is needed first of all. Health Psychology Review 2017, 11, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewitt, J.; Capistrant, B.; Kohli, N.; Rosser, B.R.S.; Mitteldorf, D.; Merengwa, E.; West, W. Addressing Participant Validity in a Small Internet Health Survey (The Restore Study): Protocol and Recommendations for Survey Response Validation. JMIR Research Protocols 2018, 7, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez, M.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; Parra, Á. Why are undergraduate emerging adults anxious and avoidant in their romantic relationships? The role of family relationships. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0224159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Taxer, J.L.; Eskreis-Winkler, L.; Galla, B.M.; Gross, J.J. Self-Control and Academic Achievement. Annual Review of Psychology 2019, 70, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Weissberg, R.P.; Gullotta, T.P. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice. The Guilford Press.

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Development 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymnicki, A.; Sambolt, M.; Kidron, Y. (2013). Improving College and Career Readiness by Incorporating Social and Emotional Learning. College and Career Readiness and Success Center. American Institutes for Research.

- EDUSTAT (2025). Distribuição dos estudantes do ensino superior. Fundação Belmiro de Azevedo. https://www.edustat.pt/indicador?id=41.

- Elias, M.J.; Zins, J.E.; Weissberg, R.P.; Greenberg, M.T.; Haynes, N.M.; Kessler, R.; Schwab-Stone, M.E.; Shriver, T.P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Erikson, E.H. The Problem of Ego Identity. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 1956, 4, 56–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2019). Key competences for lifelong learning. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/569540.

- Fein, E.C.; Skinner, N.; Machin, M.A. Work Intensification, Work–Life Interference, Stress, and Well-Being in Australian Workers. International Studies of Management & Organization 2017, 47, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraco, T.; Meneghetti, C. Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skills: Age and Gender Differences at 12 to 19 Years Old. Journal of Intelligence 2023, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Hamid, A. Mental health literacy in non-western countries: A review of the recent literature. Mental Health Review Journal 2014, 19, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Jones, T.R.; Landrosh, N.V.; Abraham, S.P.; Gillum, D.R. College Students’ Perceptions of Stress and Coping Mechanisms. Journal of Education and Development 2019, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.R.; Fish, M.C. Gender Differences in Stress and Coping in First-Year College Students. Journal of College Orientation, Transition, and Retention 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczynski, P.; Sims-Schouten, W. Evaluating mental health literacy amongst US college students: A cross sectional study. Journal of American College Health 2024, 72, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgülü, E.; Uğurlu, K. An Investigation into the Relationship between Learners’ Emotional Intelligence and Willingness to Communicate in terms of gender in the Turkish EFL Classroom. İZÜ Eğitim Dergisi 2022, 4, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Franklin, J.; Langford, P. THE SELF-REFLECTION AND INSIGHT SCALE: A NEW MEASURE OF PRIVATE SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 2002, 30, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, P.T.M.; Hall, N.C. Social Support and Motivation in STEM Degree Students: Gender Differences in Relations with Burnout and Academic Success. Interdisciplinary Education and Psychology 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Kim, E.J.; Reeve, J. Longitudinal test of self-determination theory’s motivation mediation model in a naturally occurring classroom context. Journal of Educational Psychology 2012, 104, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, S.; Sayad, A.; Taheri, M.; Aerab Sheibani, K. (2019). A Gender Difference in Emotional Intelligence and Self-Regulation Learning Strategies: Is it true? Novelty in Biomedicine, 7, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Wissing, M.; Potgieter, J.P.; Temane, M.; Kruger, A.; Van Rooy, S. Evaluation of the mental health continuum–short form (MHC–SF) in setswana-speaking South Africans. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2008, 15, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistner, K.; Sparck, E.M.; Liu, A.; Whang Sayson, H.; Levis-Fitzgerald, M.; Arnold, W. Academic and Professional Preparedness: Outcomes of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 2021, 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Fourth edition). The Guilford Press.

- Kurman, J. Self-Regulation Strategies in Achievement Settings: Culture and Gender Differences. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2001, 32, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.B. Controlling social desirability bias. International Journal of Market Research 2019, 61, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, T.; Battista, A.D.; Játiva, X.; Sharma, S.; Li, R.; Grayling, S. (2025). Future of Jobs Report 2025. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-ofjobs-report-2025/.

- Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Wagner, B.; Beck, K.; Eisenberg, D. Major Differences: Variations in Undergraduate and Graduate Student Mental Health and Treatment Utilization Across Academic Disciplines. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 2016, 30, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.; Kuron, L. Generational differences in the workplace: A review of the evidence and directions for future research: GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCES IN THE WORKPLACE. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2014, 35 (Suppl. 1), S139–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.L.; Weissberg, R.P.; Greenberg, M.T.; Dusenbury, L.; Jagers, R.J.; Niemi, K.; Schlinger, M.; Schlund, J.; Shriver, T.P.; VanAusdal, K.; Yoder, N. Systemic social and emotional learning: Promoting educational success for all preschool to high school students. American Psychologist 2021, 76, 1128–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, J.E. (1993). The Ego Identity Status Approach to Ego Identity. In J. E. Marcia, A.S. Waterman, D.R. Matteson, S.L. Archer, & J. L. Orlofsky, Ego Identity (pp. 3–21). Springer New York. [CrossRef]

- Masliyenko, T.; Reis, C.S. (2025). Motivation Differences Between STEM/HASS Students Regarding Career and Academic Achievements. In C. F. De Sousa Reis, M. Fodor-Garai, & O. Titrek (Eds.), Proceeding of the 10th International Conference on Lifelong Education and Leadership for ALL (ICLEL 2024) (Vol. 34, pp. 250–273). Atlantis Press International BV. [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.P.; André, R.S.; Cherpe, S.; Rodrigues, D.; Figueira, C.; Pinto, A.M. Estudo Psicométrico preliminar da Mental Health Continuum – Short Form – for youth numa amostra de adolescentes portugueses. Psychologica 2010, 53, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.S.; Ponitz, C.C.; Morrison, F.J. Early gender differences in self-regulation and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology 2009, 101, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, V.; Kraiger, K. Can emotional intelligence be trained? A meta-analytical investigation. Human Resource Management Review 2019, 29, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, S.; Baron, P. The impact of employability on Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences degrees in Australia. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 2023, 22, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLafferty, M.; Brown, N.; Brady, J.; McLaughlin, J.; McHugh, R.; Ward, C.; McBride, L.; Bjourson, A.J.; O’Neill, S.M.; Walsh, C.P.; Murray, E.K. Variations in psychological disorders, suicidality, and help-seeking behaviour among college students from different academic disciplines. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0279618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menard, S. (2002). Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Moshagen, M.; Bader, M. semPower: General power analysis for structural equation models. Behavior Research Methods 2024, 56, 2901–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, M.T.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Montañés Rodríguez, J.; Latorre Postigo, J.M. ¿Es la inteligencia emocional una cuestión de género? Socialización de las competencias emocionales en hombres y mujeres y sus implicaciones. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology 2008, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (2021). Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)) [OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)]. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2024). Nurturing Social and Emotional Learning Across the Globe: Findings from the OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills 2023. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Cardoso, A.; Martins, M.O.; Roberto, M.S.; Veiga-Simão, A.M.; Marques-Pinto, A. Bridging the gap in teacher SEL training: Designing and piloting an online SEL intervention with and for teachers. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy 2025, 5, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Roberto, M.S.; Veiga-Simão, A.M.; Marques-Pinto, A. Effects of the A+ intervention on elementary-school teachers’ social and emotional competence and occupational health. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 957249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Roberto, M.S.; Veiga-Simão, A.M.; Marques-Pinto, A. Development of the Social and Emotional Competence Assessment Battery for Adults. Assessment 2023, 30, 1848–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraza, L.; Chen, R. Examining Motivator Factors of STEM Undergraduate Persistence through Two-Factor Theory. The Journal of Higher Education 2022, 93, 532–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, G.; Capone, V.; Caso, D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Mental Health Continuum–Short Form (MHC–SF) as a Measure of Well-Being in the Italian Context. Social Indicators Research 2015, 121, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras, J.; Vidal-Arenas, V.; Falcó, R.; Moreno-Amador, B.; Marzo, J.; Keyes, C. Validation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) for Multidimensional Assessment of Subjective Well-Being in Spanish Adolescents. Psicothema 2022, 2, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PORDATA (2024). Alunos inscritos no ensino superior por sexo, ciclo de estudos e área de educação e formação. Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. https://www.pordata.pt/pt/estatisticas/educacao/ensino-superior/alunos-inscritos-no-ensino-superior-por-sexo-ciclo-de-estudos?_gl=1*p70b0t*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTczMTYyMzcuMTc0Njg4MjE5Mw..*_ga_HL9EXBCVBZ*czE3NDY4ODIxOTMkbzEkZzEkdDE3NDY4ODIyMTkkajAkbDAkaDA.

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review 2017, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version R 4.2.0) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project. org/.

- Reis, H.T.; Sheldon, K.M.; Gable, S.L.; Roscoe, J.; Ryan, R.M. Daily Well-Being: The Role of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2000, 26, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

- Salavera, C.; Usán, P.; Jarie, L. Emotional intelligence and social skills on self-efficacy in Secondary Education students. Are there gender differences? Journal of Adolescence 2017, 60, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M. STEM, STEM Education, STEM Mania. Technology Teacher 2009, 68, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M. Burnout and Attention Failure in STEM: The Role of Self-Control and the Buffer of Mindfulness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024, 21, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. (2004). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Preliminary Manual. https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/Test%20Manuals/Test_manual_UWES_English.pdf.

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and Engagement in University Students: A Cross-National Study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, W.R.; Scanlon, E.D.; Crow, C.L.; Green, D.M.; Buckler, D.L. Characteristics of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale in a Sample of 79 Married Couples. Psychological Reports 1983, 53, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, E.; Hunter, A.-B. (Eds.). (2019). Talking about Leaving Revisited: Persistence, Relocation, and Loss in Undergraduate STEM Education. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Simsek, O.F. Self-absorption paradox is not a paradox: Illuminating the dark side of self-reflection. International Journal of Psychology 2014, 48, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.E.M.; Baumgartner, H. Assessing Measurement Invariance in Cross-National Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research 1998, 25, 78–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steponavičius, M.; Gress-Wright, C.; Linzarini, A. (2023). Social and emotional skills (SES): Latest evidence on teachability and impact on life outcomes (OECD Education Working Papers No. 304; OECD Education Working Papers, Vol. 304). [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T.L. (2018). College Students’ Sense of Belonging (2nd ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Ter Hoeven, C.L.; Toniolo-Barrios, M. (2021). Staying in the loop: Is constant connectivity to work good or bad for work performance? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 128, 103589. [CrossRef]

- Tolan, P.; Ross, K.; Arkin, N.; Godine, N.; Clark, E. Toward an integrated approach to positive development: Implications for intervention. Applied Developmental Science 2016, 20, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetsky, K.M.; Purdie-Greenaway, V.; Cook, J.E.; Curley, J.P.; Cohen, G.L. A psychological intervention strengthens students’ peer social networks and promotes persistence in STEM. Science Advances 2020, 6, eaba9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A.C.S.; Magnan, E.D.S.; Pacico, J.C.; Hutz, C.S.; Schaufeli, W.B. Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Psico-USF 2015, 20, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissberg, R.P.; Durlak, J.A.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Gullotta, T.P. (2015). Social and emotional learning: Past, present and future. In Joseph A. Durlak, Celene E. Domitrovich, Roger P. Weissberg, & Thomas P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (1st ed., pp. 3–19). The Guilford Press.

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO report on health behaviours of 11–15-year-olds in Europe reveals more adolescents are reporting mental health concerns. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/19-05-2020-who-report-on-health-behaviours-of-11-15-year-olds-in-europe-reveals-more-adolescents-are-reporting-mental-health-concerns.

- Zhang, N.; Ren, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, K. Gender differences in the relationship between medical students’ emotional intelligence and stress coping: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable |

National reference (N = 428.206) |

Total sample (N = 735) |

|||

| % | % | M | SD | ||

| Age | NA | 22.88 | 7.30 | ||

| ≤ 18 years | 20.0 | 12.2 | |||

| 19-24 years | 62.9 | 71.1 | |||

| 25-29 years | 13.8 | 7.5 | |||

| 30+ years | 10.6 | 9.2 | |||

| Gender (Female) | 53.7 | 62.8 | |||

| Nationality (Portuguese) | 82.7 | 92.8 | |||

| Level of study | |||||

| Undergraduate | 61.9 | 68.7 | |||

| Master | 27.2 | 28.2 | |||

| PhD | 5.8 | 2.6 | |||

| Other | 4.9 | 0.5 | |||

| Education and training fields1 | |||||

| Education | 3.8 | 3.0 | |||

| Agriculture, forestry, fisheries and veterinary sciences | 2.3 | 5.2 | |||

| Arts and humanities | 10.2 | 2.2 | |||

| Natural sciences, mathematics and statistics | 5.7 | 28.1 | |||

| Social sciences, journalism and information | 11.2 | 14.4 | |||

| Engineering, manufacturing and construction | 19.8 | 35.4 | |||

| Business sciences, administration and law | 21.9 | 2.7 | |||

| Health and social protection | 15.7 | 6.4 | |||

| Services | 5.8 | 1.2 | |||

| Information and communication technologies (ICTs) | 3.4 | 1.4 | |||

| Geral and non-specific | 0.1 | 0.3 | |||

| NUT II of study2 | |||||

| North | 33.6 | 9.6 | |||

| Center | 20.5 | 16.1 | |||

| Lisbon Metropolitan Area | 37.3 | 65.4 | |||

| Alentejo | 4.4 | 4.2 | |||

| Algarve | 2.5 | 2.5 | |||

| Autonomous Regions (Azores and Madeira) | 1.58 | 2.2 | |||

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | 90% CI | AIC | BIC | dfχ2 | Model comparison | |

| CFA for the re-specified models of the Intrapersonal Competence Questionnaire (15 items and modification indices) | ||||||||||||

| Model A | 552.42*** | 84 | 6.57 | .85 | .82 | .07 | .10 | [.09, .11] | 44055.85 | 44221.45 | _ | _ |

| Model B | 333.20*** | 83 | 4.01 | .92 | .90 | .06 | .06 | [.06, .07] | 43758.43 | 43928.63 | 1, 157.92*** | Model A |

| Model C | 329.19*** | 82 | 4.01 | .92 | .90 | .06 | .08 | [.07, .09] | 43760.43 | 43935.23 | 1, 0.11 | Model B |

| CFA for the re-specified models of the Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire (16 items and modification indices) | ||||||||||||

| Model A | 366.48*** | 98 | 3.74 | .82 | .86 | .05 | .07 | [.06, .08] | 48089.13 | 48263.93 | _ | _ |

| Model B | 272.84*** | 83 | 3.29 | .92 | .90 | .05 | .06 | [.05, .07] | 45066.76 | 45236.95 | 15, 90.51*** | Model A |

| Model C | 269.56*** | 82 | 3.29 | .92 | .89 | .05 | .06 | [.06, .07] | 45068.76 | 45243.55 | 1, -0.001 | Model B |

| CFA for the re-specified models of the Responsible Decision-Making Competence Questionnaire (6 items and modification indices) | ||||||||||||

| Model A | 24.92*** | 8 | 3.12 | .98 | .96 | .03 | .05 | [.03, .07] | 17261.08 | 17320.88 | _ | _ |

| Variable | Gender | Group differences | ||||

|

Female (n = 461) |

Male (n = 265) |

|||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | Statistic | p | 95% CI | d | |

| Perceived SEC | ||||||

| Self-awareness | 7.40 (1.28) | 7.26 (1.46) | 1.334 | .182 | [-0.07, 0.34] | .10 |

| Self-regulation | 6.31 (1.51) | 6.59 (1.63) | -2.314 | .021 | [-0.51, -0.04] | -.18 |

| Conflict management | 7.23 (1.17) | 7.07 (1.23) | 1.753 | .080 | [-0.02, 0.34] | .14 |

| Positive relationship | 7.07 (1.29) | 6.93 (1.50) | 1.332 | .183 | [-0.07, 0.35] | .10 |

| Responsible Decision Making | 7.18 (1.33) | 7.12 (1.49) | 0.548 | .584 | [-0.15, 0.27] | .04 |

| Variable | Academic field | Group differences | ||||||

|

STEM (n = 513) |

HASS-H (n = 219) |

|||||||

| % | M (SD) | % | M (SD) | Statistic | p | 95% CI | d | |

| Age | 21.83 (5.77) | 25.23 (9.49) | 5.093a | < .001 | [2.26, 5.12] | .48 | ||

| Gender (Female) | 54.0 | 83.4 | .284 | < .001 | ||||

| Perceived SEC | ||||||||

| Self-awareness | 7.28 (1.33) | 7.57 (1.36) | 2.632a | .004 | [0.07, 0.51] | .21 | ||

| Self-regulation | 6.34 (1.59) | 6.58 (1.52) | 1.911a | .028 | [-0.01, 0.51] | .16 | ||

| Conflict management | 7.17 (1.21) | 7.19 (1.17) | 0.210a | .417 | [-0.17, 0.22] | -.01 | ||

| Positive relationship | 7.02 (1.37) | 7.07 (1.36) | 0.395a | .346 | [-0.18, 0.27] | .03 | ||

| Responsible Decision Making | 7.19 (1.39) | 7.16 (1.38) | -0.223a | .412 | [-0.25, 0.20] | -.03 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).