1. Introduction

Medical education is a key component of the healthcare system, as it shapes the next generation of healthcare professionals. While medical education aims at producing well-trained physicians who provide high quality care to a heterogenous group of patients, research suggests that the medical school student population often lacks social diversity, possibly leading to a deficiency in multiplicity in the respective physician workforce as well as the distribution to a broader “socio-economic spectrum“ (Khan et al., 2020; Puddey et al., 2017; Shahriar et al., 2022).

It has been suggested that it is essential to bridge the gap between the social backgrounds of doctors and patients, as it affects not only the quality of healthcare provided but also the ability of physicians to properly understand and effectively address the healthcare needs of diverse patient populations (Jackson and Gracia, 2014; Patterson and Price, 2017). Moreover, social diversity in medical education is claimed to be a factor contributing “to the learning, well-being, and effectiveness” (Roberts, 2020) of medical students.

While the definition of social diversity encompasses a variety of factors such as ethnicity, religious beliefs, language, geographical origin, gender and sexual orientation (Oxford University Press, 2024), the socioeconomic background of students is a further component of social diversity influencing the overall academic outcome and drop-out rates of higher education students (Aina et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2020). Socioeconomic diversity itself involves factors such as income, parental education level, and financial resources.

With human medicine being a highly demanded university course, matching in a German medical program is an exceedingly competitive process (Zavlin et al., 2017).

After graduating German high-school, students receive an advanced high school diploma (Abitur) including a grade point average (A-level grade) based on their performance in 11th and 12th grade of school and their final school examinations. Achieving a high A-level grade is the main criterion for successful application and matching in one of the medical programs in Germany and in the past 20% of all spots were given to those applicants with the highest A-level grade (Zavlin et al., 2017). Moreover, 60 % of all applicants were distributed via the internal selection process of medical faculties mostly based on the A-level grade but also taking other criteria into account such as medical school specific tests, successful completion of an apprenticeship in a medical field (e.g., nursing), military service or volunteer work (Zavlin et al., 2017). In the past, the final 20 % of applicants were admitted by a waiting list, meaning that those who had waited the longest since high school graduation, without being enrolled in another university course, had the best chance at receiving a spot in medical school (Zavlin et al., 2017). In December 2017, the German Federal Constitutional Court stated that essential aspects of these proceedings were unconstitutional (BVerfG, 2017). Thereupon, beginning in the summer semester of 2020, the student selection criteria for matching in one of the German medical programs were reformed (Bundestag, 2019; Selch et al., 2021). The reformation included, among other changes, an increase in the applicant group solely reliant on the A-level grade from 20% to 30% and the new introduction of the additional aptitude 10% quota, a A-level grade independent quota replacing the former waiting list (Selch et al., 2021). This additional aptitude quota can, once again, include more mature students who have completed an apprenticeship or have some other kind of experience in the medical field such as nurses, medical technical assistants or paramedics.

Therefore, one can roughly divide the German student population into two cohorts: The group of mostly younger students who effectively apply for medical school right after graduating high school with a sufficiently good A-level grade and/or ability test scores, and the group of more mature students whose applications were successful due to their valued work experience in the medical field.

In the present study, the socioeconomic background of German first-year medical school students was surveyed accompanied by various psychological questionnaires on aspects typically associated with academic skills and performance as well as psychological well-being.

For mature students in medical school as well as higher education in general, it has been shown that their academic performance is similar to that of “normal-age students”, while the latter group was more prone to receiving undergraduate awards and postgraduate degrees, including specialized qualifications (Harth et al., 1990; Richardson, 1995). Mature students have been described to have a more intrinsic and altruistic motivation to study medicine, while younger students are more likely to be influenced by their family background and parental expectations (Harth et al., 1990; Richardson, 1994). Harth et al. (1990) also found that mature medical students experienced more stress for example due to financial difficulties, highlighting the demand of target-group orientated medical school curricula and supervision.

Apart from academic performance itself, various other associated psychological attributes were analyzed among the first-year medical student cohort. Financial anxiety for example has been linked to negative academic outcomes and mental health problems (Potter et al., 2020). For academic behavioral confidence, which can be influenced by both personal and contextual factors, a positive association with self-regulation, a deep learning approach as well as academic achievement has been described (de la Fuente et al., 2021, 2014; Nicholson et al., 2013). Socioeconomic background has also been defined as a variable moderating the relation between test anxiety and test performance (Putwain, 2008). With medicine being a demanding field of education, psychological stress shows a high prevalence in medical students (Waqas et al., 2015). Therefore, the ability to cope with academic stress, as a further possible predictor for academic performance (Struthers et al., 2000), was compared in a socioeconomic dependent manner.

For the characterization of the mature student group in comparison with the younger group, the A-level grade of their high-school diploma, their competence in natural science subjects necessary for preclinical studies as well as their self-assessment of previous clinical experience was surveyed. Moreover, the online competence of both groups was compared which is especially relevant in times of the recent COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing transition of solely face-to-face learning to hybrid study concepts with an increasing proportion of online education (Gellisch et al., 2022, 2023). Mature students are characterized by the completion of an apprenticeship prior to entering medical school. In order to evaluate the impact of a completed apprenticeship as a form of non-academic vocational training on the academic skills of mature students, additional questionnaires on their resilience were compared. The capability of resilience, which also includes the aspect of self-efficacy, is described as the dynamic ability to thrive amidst challenges (Howe et al., 2012). It is characterized as an important skill in clinical students and healthcare professionals and recommended to be promoted during medical education (Dunn et al., 2008; Howe et al., 2012). Moreover, resilience associates positively with academic performance (Abubakar et al., 2021). Previous research shows that life experiences often associated with mature students, such as work and caregiving, might enhance resilience levels (Chung et al., 2017). Additionally, worries about balancing studies and job as a possible concern of mature students, who often continue to work part time in their prior position during medical school, were surveyed and compared.

The aim of the present study was to analyze the sociodemographic constitution of German first year medical students focusing on differences between mature and younger students regarding their self-assessment of personal and professional skills postulated to be required for successful completion of university medical education. The results might contribute to an enhanced representation of the German medical student population, which allows for demand-oriented didactic concepts and superiorly convenient medical curricula.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims at exploring the impact of socioeconomic backgrounds and work experience on the academic performance, psychological well-being, and professional skills of first-year medical students in Germany. It also examines the effects of different pathways to medical school, including those for mature students with prior work experience in the medical field, on academic and professional competencies with a strict focus on study entry conditions.

The questionnaire designed for this aim as well as the performance assessment were completed in digital form, but in person, in order to ensure focused processing and to rule out the use of external assistance during the performance test.

At the core of the developed survey tool was the processing of the grouping variable, which divided the personal socio-economic status into the 5 categories ‘below-average’, ‘slightly below-average’, ‘average’, ‘slightly above-average’ and ‘above-average’. In developing a questionnaire that accurately reflects the research objectives, a selected panel of standardized scales was chosen. Each scale was chosen for its relevance and proven effectiveness in exploring the specific aspects of our research questions.

A more in-depth analysis of the aspect of socio-economic status was carried out by incorporating a German translation of the Financial Anxiety Scale (FAS), developed by Archuleta, Dale, and Spann (2013), to assess financial anxiety among the student participants. This particular scale serves as a valuable tool for comprehending the intricate interplay between student’s financial circumstances and their psychological well-being. It specifically delves into critical dimensions such as debt, financial contentment, and the manifestation of anxiety pertaining to financial matters (Archuleta, Dale, & Spann, 2013).

For the assessment of cognitive test anxiety, the study utilized the Cognitive Test Anxiety Scale (CTAS), as formulated by Cassady and Johnson (2002). This scale is recognized for its effectiveness in quantifying the degree of anxiety that students encounter in testing situations (Cassady & Johnson, 2002). Furthermore, the study incorporated a culturally and linguistically adapted German version of this scale (G-CTAS), meticulously developed and psychometrically evaluated by Stefan, Berchtold, and Angstwurm (2020), thereby ensuring its appropriateness for the German student cohort (Stefan, Berchtold, & Angstwurm, 2020).

A German translation of the Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC) Scale, developed by Sander and Sanders (2003), was employed to quantitatively evaluate the participants’ confidence in their academic abilities. This comprehensive instrument is specifically designed to assess the extent of a student’s self-assurance within academic settings (Sander & Sanders, 2003).

In addition, a German translation of the Resilience Questionnaire Scale (RQS), specifically the shortened version of the Nicholson McBride Resilience Questionnaire (NMRQ) and the Student Self Efficacy (SEE) Scale, conceived by Rowbotham and Schmitz (2013), were incorporated in this research design. The RQS is widely acknowledged for its utility in diverse research settings, providing valuable insights into how individuals manage and adapt to stress and challenges (NHS England & Wales, 2020). The SSE is instrumental in determining students’ perceived ability to successfully execute academic tasks, thereby offering insights into their intrinsic motivation and self-regulation capacities (Rowbotham & Schmitz, 2013).

Additionally, this study employed the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory, formulated by Conroy, Willow, and Metzler (2002), to ascertain the participants’ fear of experiencing failure. This multidimensional tool is vital in elucidating aspects of fear of failure, especially in high-pressure academic environments (Conroy, Willow, & Metzler, 2002). To enhance the scale’s relevance for the German-speaking demographic, a validated German adaptation by Henschel and Iffland (2021) was utilized, ensuring the scale’s contextual applicability (Henschel & Iffland, 2021).

Worries about balancing studies and a job, previous clinical experience, competence in natural science subjects as well as online competence were measured employing a visual analogue scale, to enable the collection of data that can be measured on both continuous and interval scales (Funke and Reips, 2008). Further grouping variables were integrated to identify whether the participants already had work experience or had completed an apprenticeship.

To assess the academic competencies of first-year medical students, particularly in areas pertinent to their upcoming studies, a specialized expert panel was convened. This panel was composed of distinguished members from the academic medical community, including a professor and an academic counselor specializing in anatomy, as well as two senior medical students in order to integrate the student perspective. The primary task of this panel was to formulate a set of science-related questions that would effectively evaluate the basic science knowledge of incoming medical students, with an emphasis on thematic areas crucial for their first-year studies, particularly in anatomy and physiology. To ensure the relevance and appropriateness of these questions, the panel adhered to two key criteria. Each question was designed to correspond with the general school curriculum. This approach was adopted to ensure that the assessment was grounded in the foundational knowledge that students are expected to have acquired prior to entering medical school. The content of the questions was carefully chosen to reflect the essential basic science knowledge that would be beneficial for students in their initial semester of medical studies. In total, the expert panel crafted nine questions that met these stringent criteria (see Appendix). These questions were then utilized as a key component of the performance assessment, providing valuable insights into the preparedness and foundational knowledge of the first-year medical student cohort.

The primary requirement for inclusion in the study was that participants must be duly enrolled as first-semester medical students at Ruhr University Bochum at the time of data collection. This criterion ensured that the study focused on individuals who were at the very outset of their medical education, providing a uniform baseline. In line with the study’s focus to explore social diversity in medical education, the recruitment strategy was designed to be as inclusive as possible. The study did not impose any age restrictions, ensuring representation from both younger students and mature students who might have entered medical school later in life. Notably, this approach resulted in the successful assessment of almost the entire cohort of first-year medical students for that academic year, thereby providing a comprehensive and representative overview of the group’s characteristics and experiences.

The stud

y’s participant pool comprised 336 first-semester medical students from Ruhr University Bochum, offering a diverse demographic snapshot. Among the participants, females constituted the majority, with 227 students (67.56%), while male students accounted for 107 individuals (31.85%). Additionally, 2 students (0.60%) identified as gender diverse. The average age of the participants was 20.40 years, with a standard deviation of 3.10 years. Notably, female students had an average age of 20.15 years (SD = 2.97), slightly younger than male students who averaged at 20.95 years (SD = 3.37). The gender diverse group had an average age of 19.50 years (SD = 0.71) (

Table 1). For more comprehensive characteristics of the cohort in terms of socioeconomic status, frequency of students whose parents did not go to university, frequency of students whose parents are physicians, frequency of students with working experience and frequency of students with completed apprenticeship please see

Table 1. This study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Professional School of Education at Ruhr University Bochum (Reference No. EPSE-2022–005, dated 10.10.2022). This approval ensured the ethical conduct of the research in accordance with international standards.

The study employed comprehensive statistical methods to analyze the collected data. For descriptive statistics, a range of measures was calculated to provide a detailed overview of the data characteristics. These included the Median, Mean, Standard Error of Mean, Standard Deviation, Interquartile Range (IQR), Variance, Skewness along with its Standard Error, Kurtosis, and the Standard Error of Kurtosis, as well as the Minimum and Maximum values.

To investigate differences between students who have either work experience or completed an apprenticeship and those who do not, Welch’s t-test was utilized for two-group comparisons, ensuring robustness even with unequal variances. For comparing more than two groups, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed, with an alpha level set at 0.05 and p-values adjusted according to the Bonferroni-Holm correction method to control for the risk of type I errors in multiple comparisons. Additionally, correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between different variables. Pearson’s r was calculated along with 95% confidence intervals to assess the strength and direction of these relationships. R statistical software was used for all statistical calculations (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

The analysis of the collected data commenced with a comprehensive descriptive evaluation of the various scales utilized in the study. This initial step involved a detailed examination of the participants’ responses, providing a foundational understanding of the data’s distribution and central tendencies. Subsequently, we performed analyses of variance (ANOVA) to investigate the potential influence of socioeconomic background on specific factors. This analysis aimed to discern whether variations in socioeconomic status were associated with differences in key study variables. Further, the participants were grouped based on their work experience and completion of apprenticeships. This categorization allowed for an in-depth exploration of the impact of practical work experience on the assessed factors, offering insights into how these experiences might shape academic and psychological outcomes. Finally, correlation analyses were conducted to uncover potential relationships between relevant constructs. These analyses aimed to identify significant correlations, providing a deeper understanding of how these variables interplay within the context of medical education.

In the initial analysis of our data, we conducted descriptive statistics for various scales, as shown in

Table 2. The measures included the Financial Anxiety Scale (FAS), Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC), German-Cognitive Test Anxiety Scale (CTAS), Fear of Shame and Embarrassment (FSE), Coping with Academic Stress (CAS), Resilience Questionnaire Scale (RQS), Student Self Efficacy (SSE), and others assessing factors such as Worries about Balancing Studies and a Job (WBSJ), Online Competence (OC), Clinical Experience (CE), Natural Sciences Competence (CNS), and A-level Grade (ALG). The median scores across these scales provided a central tendency of the dataset. The median for Performance was 3.000, with other notable medians including FAS at 1.143 and ABC at 6.958. The mean scores mirrored these tendencies, with Performance at 3.234, FAS at 1.321, and ABC at 6.934. The variability of responses was quantified through the standard deviation and interquartile range (IQR). For instance, the standard deviation for Performance was 2.207, indicating a moderate spread of scores around the mean. The IQR for the same scale was 3.250, highlighting the middle 50% range of scores. The dat

a’s distribution characteristics were further explored through measures of skewness and kurtosis. The skewness of the Performance scale was 0.425, suggesting a slight asymmetry in its distribution. The kurtosis value of -0.617 for this scale suggests a distribution that is somewhat flatter than that of a normal distribution. Finally, the ranges of the scales were considered, with the Performance scale ranging from a minimum of 0.000 to a maximum of 9.000. This broad range suggests a wide variation in student performance (

Table 2).

Subsequent to the descriptive analysis, Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) were conducted to examine the influence of socioeconomic status (SES) on various psychological and performance measures (

Table 3).

For the Financial Anxiety Scale (FAS), the ANOVA showed a significant effect of SES, F(4, 331) = 17.391, p < .001, with a notable effect size (η² = 0.174 and ω² = 0.163), suggesting that variations in SES are strongly associated with differences in financial anxiety among students.

In the context of Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC), the analysis yielded F(4, 331) = 4.323, p = 0.002, with a smaller yet significant effect size (η² = 0.050, ω² = 0.038). This indicates that SES also plays a role in influencing students’ confidence in their academic abilities.

For the German-Cognitive Test Anxiety Scale (CTAS), SES-related differences were again significant, F(4, 331) = 4.482, p = 0.002, with effect sizes of η² = 0.051 and ω² = 0.040. This finding suggests a notable association between socioeconomic background and cognitive test anxiety among the students.

Similarly, in assessing the influence of SES on Coping with Academic Stress (CAS), the results showed a significant effect, F(4, 331) = 5.837, p < .001, with η² = 0.066 and ω² = 0.054, indicating that SES significantly impacts how students cope with academic stress.

When examining Student Self Efficacy (SSE), the ANOVA indicated a significant effect of SES, F(4, 331) = 3.915, p = 0.004, with effect sizes of η² = 0.045 and ω² = 0.034. This highlights SES as a factor influencing students’ beliefs in their capabilities to execute academic tasks.

However, the influence of SES on the Resilience Questionnaire Scale (RQS) approached significance, F(4, 331) = 2.372, p = 0.052, with smaller effect sizes (η² = 0.028, ω² = 0.016), suggesting a potential but less pronounced impact of SES on resilience.

The analysis for Worries about Balancing Studies and a Job (WBSJ) yielded F(4, 331) = 2.106, p = 0.080, with η² = 0.025 and ω² = 0.013, indicating a marginal influence of SES on concerns about managing studies and employment.

For Fear of Shame and Embarrassment (FSE), and Performance (PERF), the results were not significant, with FSE showing F(4, 331) = 1.457, p = 0.215, and η² = 0.017, ω² = 0005, and PERF showing F(4, 331) = 1.067, p = 0.373, η² = 0.013, ω² = 0.0008. These findings suggest that SES does not significantly impact the fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment or the overall academic performance in this cohort.

The ANOVA results indicate that socioeconomic status plays a significant role in various aspects of student

s’ experiences, particularly in areas related to financial anxiety, academic confidence, test anxiety, and coping with academic stress. However, its impact on resilience, worries about balancing studies and a job, fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment, and academic performance appears to be less pronounced or not significant in this study group (

Figure 1).

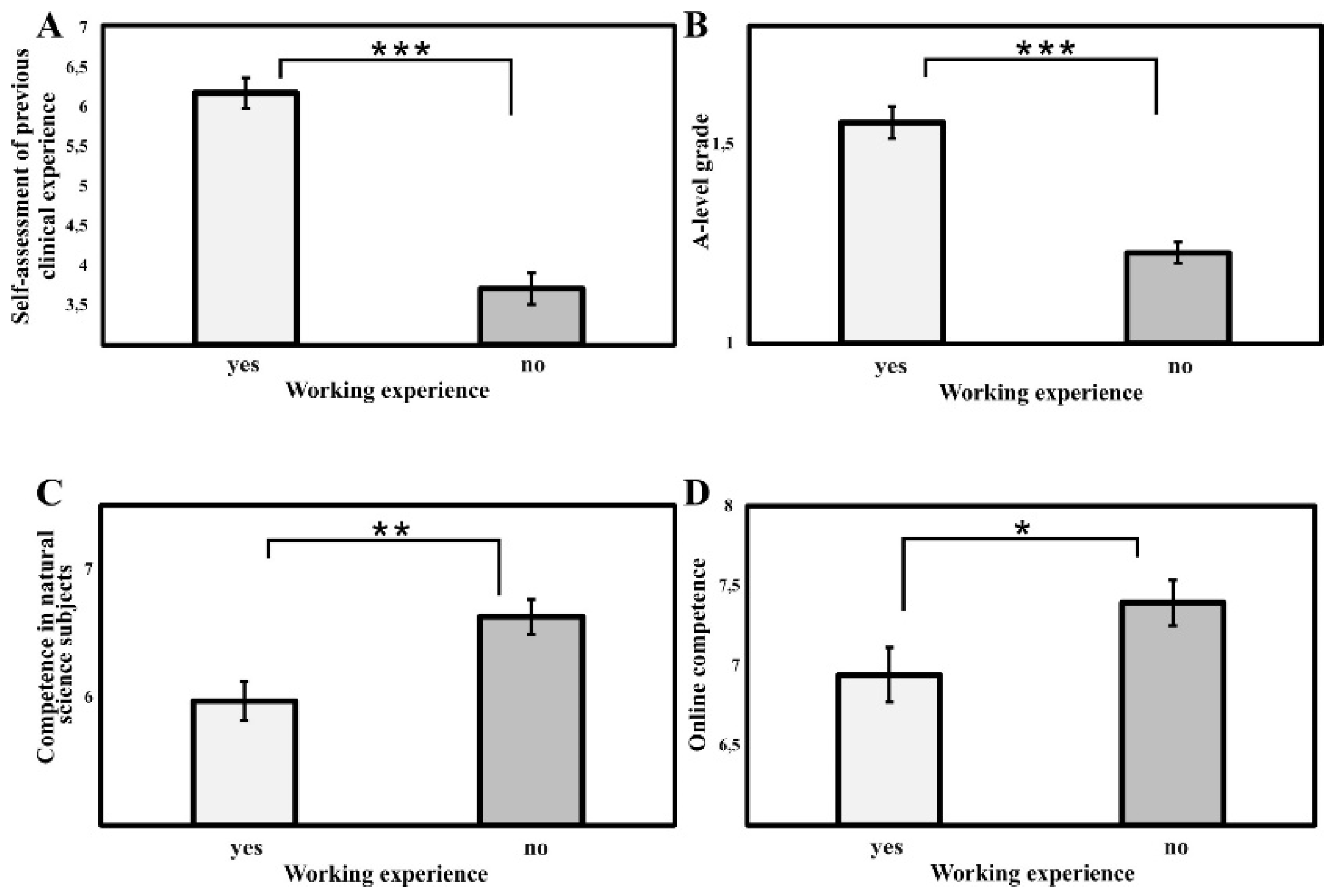

We further explored the differences between students with prior work experience and those without such experience. This comparison focused on self-assessment of previous clinical experience, A-level grade, competence in natural sciences subjects, and online competence.

Our analysis revealed significant differences in self-assessment of previous clinical experience, t(333.840) = 8.889, p < .001. Students with work experience reported higher levels of clinical experience compared to their counterparts without such background (

Figure 2A).

In terms of performance as measured by A-level grades, there was a significant difference between the two groups, t(279.459) = 6.690, p < .001. This result indicates that students who already gained work experience scored significantly lower in their A-level grade (

Figure 2B).

When assessing self-perceived competence in natural sciences subjects, the study found a significant difference, t(321.045) = -3.178, p = 0.002, demonstrating that students without prior work experience reported higher competence in natural sciences compared to those with work experience (

Figure 2C).

The analysis of online competence showed a significant difference, t(319.429) = -2.026, p = 0.044. Students without work experience demonstrated higher competence in online learning environments compared to those with work experience (

Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates the differences in key outcomes between students with and without prior working experience. The bar chart is divided into four parts, labeled A, B, C and D: self-assessment of previous clinical experience (A), A-level grade (B), competence in natural sciences subjects (C) and online competence (D). The height of each bar indicates the mean score for each group, with error bars representing the standard error. A-level grade was rated on a scale from 1.0 to 4.0, where 1.0 represents the highest achievable A-level grade. Significant differences between groups are marked with asterisks, where * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and *** denotes p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates the differences in key outcomes between students with and without prior working experience. The bar chart is divided into four parts, labeled A, B, C and D: self-assessment of previous clinical experience (A), A-level grade (B), competence in natural sciences subjects (C) and online competence (D). The height of each bar indicates the mean score for each group, with error bars representing the standard error. A-level grade was rated on a scale from 1.0 to 4.0, where 1.0 represents the highest achievable A-level grade. Significant differences between groups are marked with asterisks, where * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and *** denotes p < 0.001.

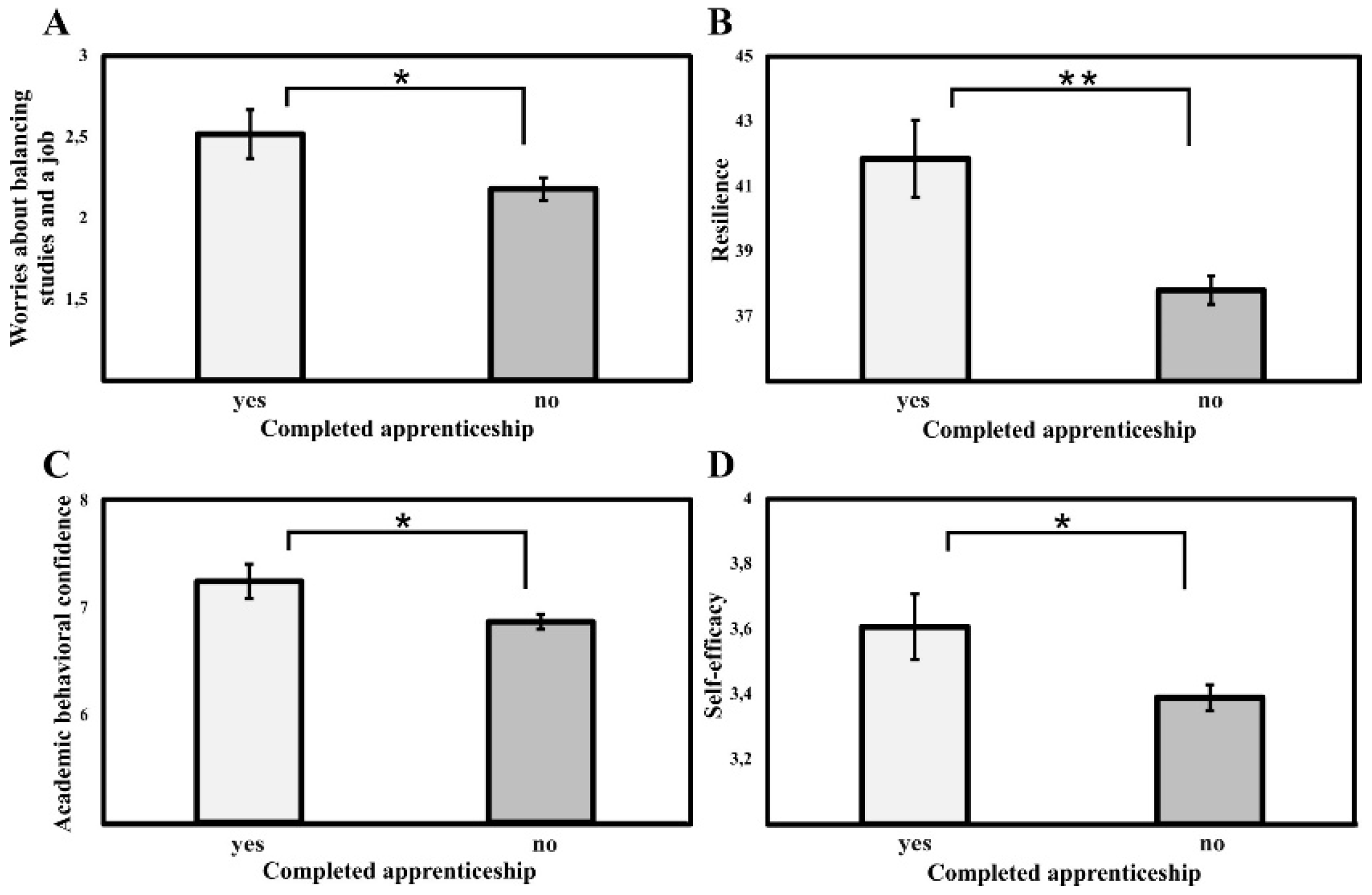

Deepening these analyses, we assessed the differences between students who had completed an apprenticeship prior to their medical studies and those who had not. The focus was on worries about balancing studies and a job, resilience as measured by the Resilience Questionnaire Scale (RQS), Academic Behavioral Confidence as measured by the Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC) Scale, and self-efficacy as measured by the Student Self Efficacy (SSE) Scale.

For worries about balancing studies and a job, the t-test showed a significant difference, t(73.490) = 2.097, p = 0.039. This suggests that students with a completed apprenticeship experienced greater concerns about managing their studies alongside a job compared to those without such experience (

Figure 3A).

In terms of resilience (RQS), there was a significant difference, t(68.134) = 3.158, p = 0.002. Students who had completed an apprenticeship demonstrated higher levels of resilience compared to their peers without apprenticeship experience (

Figure 3B).

Regarding Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC), the analysis revealed a significant difference, t(70.380) = 2.085, p = 0.041. This finding indicates that students with apprenticeship experience had higher academic confidence than those without such background (

Figure 3C).

In the aspect of self-efficacy (SSE), the results showed a significant difference, t(68.847) = 2.020, p = 0.047. This suggests that students with apprenticeship experience possessed a stronger belief in their capabilities to successfully execute academic tasks compared to their counterparts without an apprenticeship (

Figure 3D).

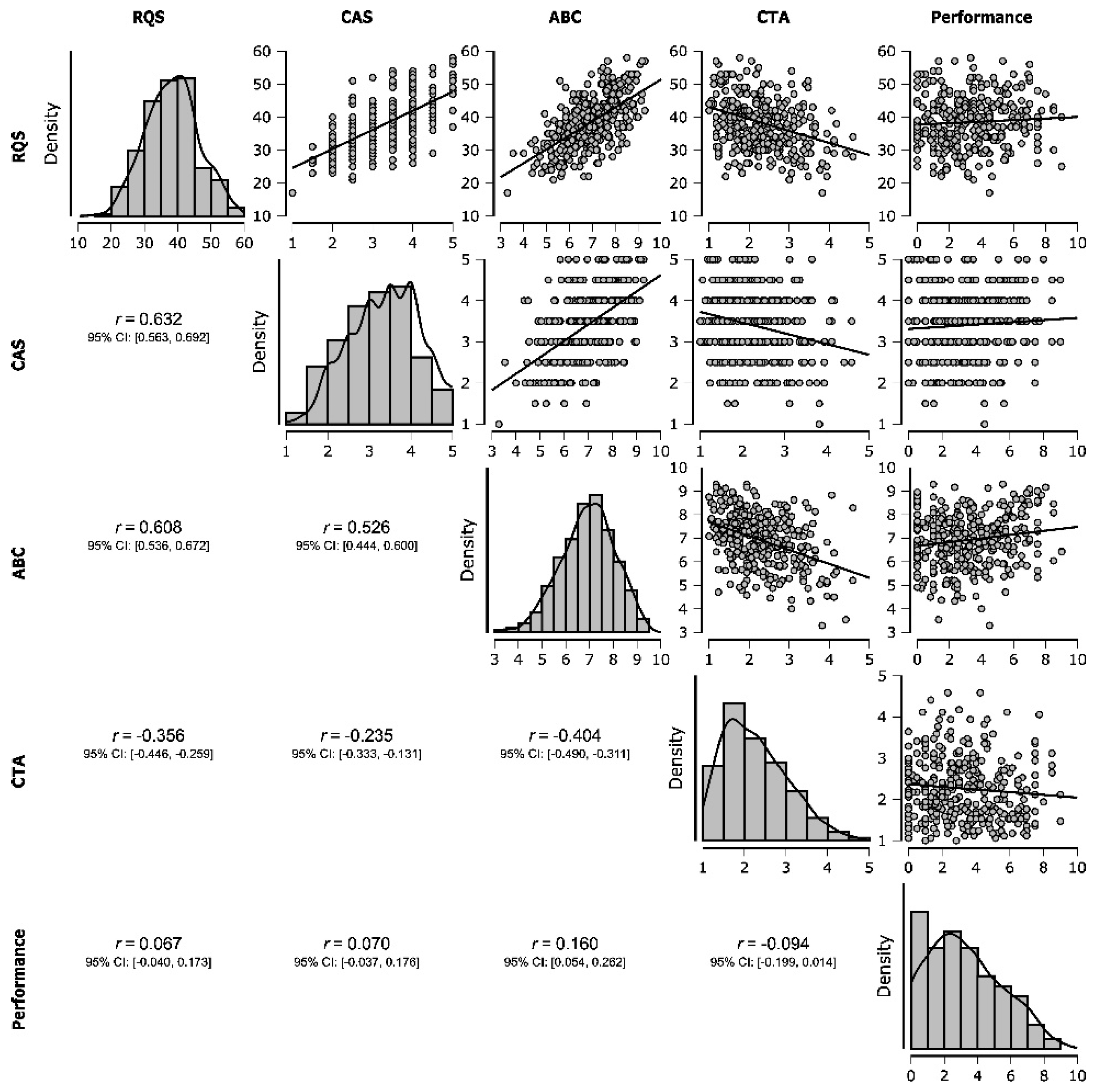

The study further investigated the relationships between key constructs: Resilience (RQS), Coping with Academic Stress (CAS), Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC), Cognitive Test Anxiety (CTA), and Performance, using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Pearso

n’s r) and associated p-values (

Figure 4).

A strong positive correlation was observed between Resilience (RQS) and Coping with Academic Stress (CAS), r = 0.632, p < .001, suggesting that higher resilience is associated with better coping strategies in academic stress situations. Additionally, a significant positive correlation was found between RQS and Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC), r = 0.608, p < .001, indicating that increased resilience is linked with higher confidence in academic abilities (

Figure 4).

Coping with Academic Stress (CAS) also showed a significant positive correlation with ABC, r = 0.526, p < .001, implying that students who are better at coping with academic stress tend to have higher academic confidence (

Figure 4).

Conversely, there were negative correlations observed with Cognitive Test Anxiety (CTA). Resilience (RQS) inversely correlated with CTA, r = -0.356, p < .001, suggesting that higher resilience is associated with lower cognitive test anxiety. Similarly, both CAS and ABC negatively correlated with CTA, r = -0.235 and r = -0.404 respectively, both p < .001, indicating that better coping mechanisms and higher academic confidence are associated with lower test anxiety (

Figure 4).

In terms of academic performance, the correlations were relatively weaker and less consistent. However, performance showed a significant positive correlation with ABC, r = 0.160, p = 0.003, suggesting a modest association between academic confidence and performance. However, correlations between Performance and other constructs like RQS, CAS, and CTA were not statistically significant, with r values of 0.067 (p = 0.220), 0.070 (p = 0.199), and -0.094 (p = 0.087) respectively (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This research project provides a comprehensive exploration of the impact of socioeconomic backgrounds and work experience on first-year medical students. The findings provide insightful revelations into how these factors influence various aspects of medical education, including academic performance, psychological well-being, and professional skills. An important aspect of this research project is the characterization of the study site – the city of Bochum, located in the central west of Germany. Bochum’s geographical and socio-cultural context played a significant role in shaping the findings of our study. Being a city with a diverse population and a rich industrial history, Bochum represents a setting that reflects the broader dynamics of urban centers in Germany. This diversity is crucial in understanding the backgrounds and experiences of the medical students enrolled at Ruhr University Bochum.

In line with this, our study’s descriptive analysis revealed significant diversity within the student cohort in terms of financial anxiety, academic confidence, and coping strategies for academic stress, among other factors. These variations underscore the complexity of the student experience in medical education, influenced by an array of social and personal factors. Notably, the socioeconomic status (SES) of students emerged as a significant determinant in several key areas, especially in financial anxiety and academic confidence, aligning with the existing literature that underscores the impact of SES on educational outcomes (Coleman et al., 1966; Reardon, 2013; Xu et al., 2021).

However, contrary to the significant correlation between socioeconomic status (SES) and academic achievement found in earlier studies, such as the landmark research by Coleman et al. (1966), our study did not observe a significant difference in performance based on SES among first-year medical students. Coleman’s comprehensive study, involving over 640,000 students across 4000 schools in the USA, had highlighted the dominant role of family SES in academic achievement, surpassing even the influence of schools. Reardon (2013) suggests that the strength of the SES-academic achievement relationship reflects educational equity: a higher correlation indicates a wider achievement gap between high-SES and low-SES students. The lack of significant differences in our study could imply that factors other than SES have become more relevant in the current educational context, possibly due to improvements in educational equity and access. This notion is supported by the work of Heyneman and Loxley (1983), who noted that the relationship between SES and academic achievement is not consistent and varies across different contexts. They highlighted that this relationship depends significantly on the socio-economic and cultural environment, suggesting that in certain contexts SES might not be as pivotal a determinant of academic performance as it once was. Additionally, the findings of Liu et al. (2020) and Soharwardi et al. (2020) hint at evolving dynamics in the influence of SES. Liu et al. (2020) reported a decreasing trend in the relationship between SES and academic achievement over the past decades. Simultaneously, Soharwardi et al. (2020) emphasized the role of maternal education and governmental support in enhancing student performance, suggesting that these factors might now be playing a more critical role.

However, it is crucial to consider factors that indirectly influence academic performance, particularly the significant effect of socioeconomic status (SES) on financial anxiety, as demonstrated in our study. This link is critical, given the substantial evidence suggesting that financial anxiety can adversely affect students’ mental health and educational outcomes. Financial stress correlates with increased mental health issues and disrupted sleep, factors that can impede academic success (Szkody et al. 2022). In line with these findings, Trombitas (2012) further notes that financial worries extend beyond monetary concerns, negatively impacting students’ academic performance. Echoing these findings, Xiao et al. (2017) observed trends of rising anxiety and depression among college students, correlating with financial stress. Further, financial stress can be linked to academic decisions, such as reduced course loads or dropout, and to poorer performance (Joo et al., 2008). Additionally, Potter et al. (2020) emphasize the heightened financial anxiety among first-generation students, suggesting that targeted financial counseling could alleviate some of these stressors. In light of our findings, it becomes imperative to heighten awareness about the relevance of financial anxiety in the context of academic performance, particularly as a step towards achieving more equal educational opportunities. The significant relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and financial anxiety observed in our study underscores the need for educational institutions to recognize and address the broader implications of financial stress on student well-being and learning outcomes.

It is common knowledge that academic behavioral confidence shows a positive correlation with academic performance (Checchi and Pravettoni, 2003), yet its influence is subject to variation across diverse contexts and individual characteristics. The interplay of self-confidence, the possibility of overconfidence (Erat et al., 2016), and personal expectations in determining academic success is rather complex, influenced by a multitude of factors. Academic behavioral confidence is also used as a relevant marker to predict the success of first-semester students in meeting the newly emerging demands of higher education (Sanders and Sander, 2007). This aligns with our findings, suggesting that students from higher SES backgrounds may have an advantage in adapting to the demands of higher education. In light of our findings, the relationship between SES and academic behavioral confidence becomes a crucial area for educational interventions. Efforts to equalize educational opportunities should consider not only the direct academic support for lower SES students but also strategies to build and correctly calibrate their academic confidence, ensuring that all students can optimally engage with and benefit from higher education.

The significant impact of socioeconomic status (SES) on cognitive test anxiety, as observed in our study where higher SES correlated with lower test anxiety, aligns with findings from recent research. Xu et al. (2021) highlight that higher SES is associated with factors like increased learning resources and academic self-efficacy, leading to lower test anxiety. This complements our results, suggesting that students from higher SES backgrounds enjoy advantages that alleviate anxiety during tests. Supporting this, it could be demonstrated that high test anxiety can lead to poorer academic achievement, a challenge more pronounced in lower SES students (Akanbi, 2013; Balogun et al., 2017). Further research in this field links first-generation student status, a proxy for lower SES, with increased financial anxiety, shaping academic experiences (Potter et al. 2020).

Contrary to our initial expectations, it was not the students with the lowest SES who reported the most challenges, but rather those who placed themselves in the mid-to-lower range of the SES spectrum. This pattern was particularly evident in areas such as academic behavioral confidence, cognitive test anxiety, and coping with academic stress. This finding suggests a more complex dynamic than a straightforward linear relationship between SES and these variables. Students in the mid-to-lower SES category may face unique pressures and challenges that are less prevalent among their peers with the lowest SES. For instance, these students might experience heightened expectations to succeed or may lack the same level of support systems or coping mechanisms available to those at either end of the SES spectrum. This could potentially explain their lower academic confidence, higher test anxiety, and reduced ability to cope with academic stress. Furthermore, this observation underscores the importance of considering the full spectrum of SES in educational and psychological research, rather than focusing solely on the extremes. It highlights that students with mid-to-lower SES face distinct challenges that require targeted support and intervention. This understanding is crucial for the development of nuanced educational policies and mental health services that cater to the diverse needs of the entire student body, particularly those who might fall into this overlooked and potentially vulnerable group.

In addition, our data reveal a complex picture of the impact of prior working experience on medical students’ competencies. While students with such experience show significantly higher self-perceived clinical experience, they also tend to have lower A-level grades, less competence in natural sciences, and weaker online skills. This finding aligns with Benor and Hobfoll (1981), who observed that medical students with diverse life experiences, such as military or science backgrounds, often demonstrate superior clinical performance. Further exploration revealed that medical students with pre-matriculation clinical experience outperformed their peers in crucial medical exams (Shah et al., 2018). Similarly, McKenzie & Mellis (2017) reported that practical experience prior to medical school enhances students’ preparedness for clinical practice. This can additionally be reinforced by findings which highlight the positive impacts of working as healthcare assistants on medical students’ understanding of clinical environments (Walker et al. 2017). These studies suggest that while prior work experience can lead to gaps in certain academic areas, it significantly enhances clinical skills and understanding, highlighting the value of practical experience in medical education. However, awareness should be created for the associated less developed skills, for example in the area of online competence, as this can be of particular relevance in the course of advancing digitalization in the academic sector.

Our findings that students with completed apprenticeships exhibit higher resilience, academic behavioral confidence, and self-efficacy, but also face greater challenges in balancing studies and work, resonate with existing literature on the value of practical experiences in education. Previous findings highlight the role of academic self-efficacy in fostering key student competencies, suggesting that hands-on experiences from apprenticeships could enhance these attributes (Dixon et al., 2020). It could be shown that there is a strong link between academic self-efficacy and resilience (Cassidy, 2015), a pattern observed in our study, where apprenticeship-experienced students displayed both traits robustly. Related research work emphasizes the impact of resilience on performance and well-being, mediated by self-efficacy (Etherton et al., 2020). Our data reflects this complex interaction, as apprenticeship students demonstrate significant resilience and self-efficacy, yet struggle with the added pressure of managing work alongside their studies.

The recent findings of Schröpel et al. (2024) both contrast with and complement our observations, suggesting a nuanced view of the impact of prior experiences on medical education. While they report that prior professional and academic qualifications do not translate to academic success, as measured by traditional examinations, our research indicates that such experiences enhance students’ resilience and academic confidence. This discrepancy highlights the complexity of assessing academic success, underscoring the potential of personal qualities and non-academic skills gained from prior experiences, which are not captured by conventional metrics but are crucial for navigating medical education.

The correlation analysis of our study, examining the relationships between Resilience (RQS), Coping with Academic Stress (CAS), Academic Behavioral Confidence (ABC), Cognitive Test Anxiety (CTA), and Performance, yields insights that align with and extend the findings of existing literature in the field of educational psychology. Significantly, we found a strong positive correlation between Resilience and Coping with Academic Stress, as well as between Resilience and Academic Behavioral Confidence. This indicates that higher resilience is associated with better coping abilities and greater confidence in academic settings, echoing the findings of Mulati & Purwandari (2022), who reported a negative correlation between resilience and academic stress. Our results reinforce the idea that resilience is a crucial factor in managing academic stress effectively. Further, our analysis revealed negative correlations between Resilience, Coping with Academic Stress, Academic Behavioral Confidence, and Cognitive Test Anxiety (CTA). Specifically, higher resilience and confidence were associated with lower CTA. This complements the work of Havnen et al. (2020), who found that resilience moderates the relationship between stress and anxiety. Our findings suggest that resilience not only helps in coping with academic stress but also plays a vital role in reducing test anxiety, a key factor impacting academic performance. Regarding performance, the correlations were weaker. There was a modest but significant positive correlation between Academic Behavioral Confidence and Performance (r = 0.160, p = 0.003), suggesting that confidence does contribute to academic achievement, albeit to a lesser extent. This is in line with Duty et al. (2016), who found a correlation between cognitive test anxiety and academic performance among nursing students, indicating that psychological factors, including confidence and anxiety, have important, albeit complex, roles in academic success. These correlations underscore the interconnectedness of resilience, stress coping, confidence, and anxiety in the academic context.

5. Conclusions

These results highlight the complexity of factors influencing medical students’ experiences and performance. Notably, the interplay of SES, prior work experience, and apprenticeships profoundly affects students’ academic behavioral confidence, resilience, and coping mechanisms, which are crucial for success in the demanding field of medicine. Future research should delve deeper into understanding how these factors interact over the course of medical education and their long-term impact on professional competencies and patient care. Particularly, investigating interventions that can mitigate the challenges faced by students from diverse backgrounds is essential. This could include developing support systems for students with lower SES, enhancing academic confidence among students without prior work experience, and providing resources to help mature students balancing their academic and work commitments more effectively. Furthermore, the diversity of the student body in medical schools presents a unique opportunity for the exchange of beneficial traits and experiences among students. Students with work experience or apprenticeships can share practical insights and resilience strategies, while those from varied SES backgrounds can offer diverse perspectives and relevant skill sets. Facilitating this exchange within the student community could enrich the learning environment, fostering a more supportive and collaborative atmosphere. In conclusion, our study underscores the need for a more holistic approach in medical education, considering the diverse backgrounds and experiences of students. By addressing the specific challenges and leveraging the unique strengths of students from all walks of life, medical schools can not only enhance the educational experience but also prepare a more competent, empathetic, and diverse healthcare workforce for the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and T.S.; methodology, M.G.; software, M.G.; validation, M.G., T.S., B.BS. and M.B.; formal analysis, M.G.; investigation, M.G.; resources, T.S. and B.BS.; data curation, M.G., T.S. B.BS. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.B., B.BS. and T.S..; visualization, M.G.; project administration, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Professional School of Education at Ruhr University Bochum (Reference No. EPSE-2022–005, dated 10.10.2022). This approval ensured the ethical conduct of the research in accordance with international standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are profoundly grateful to the participating students for their invaluable time and thoughtful feedback, which played a pivotal role in shaping the outcomes of our research. We further acknowledge the Institute of Anatomy at Ruhr University Bochum for their cooperation and support, which were key to the success of our study. The collaboration and contributions of all those involved were essential to this research, and we extend our deepest appreciation for their dedication. We also acknowledge that large language models were utilized strictly under the control and supervision of the authors, solely to enhance the readability and language of this work. All scientific content, analysis, and interpretations remain the original work of the authors. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abubakar, U., Mohd Azli, N.A.S., Hashim, I.A., Adlin Kamarudin, N.F., Abdul Latif, N.A.I., Mohamad Badaruddin, A.R., Zulkifli Razak, M., Zaidan, N.A., 2021. The relationship between academic resilience and academic performance among pharmacy students. Pharmacy Education 21, 705–712. [CrossRef]

- Aina, C., Baici, E., Casalone, G., Pastore, F., 2022. The determinants of university dropout: A review of the socio-economic literature. Socioecon Plann Sci 79, 101102. [CrossRef]

- Bundestag, 2019. Gesetz zu dem Staatsvertrag über die Hochschulzulassung und zur Änderung des Hochschulzulassungsgesetzes. Germany.

- BVerfG, 2017. Judgment of the First Senate of 19 December 2017 - 1 BvL 3/14 -, paras. 1-253. Germany.

- Chung, E., Turnbull, D., Chur-Hansen, A., 2017. Differences in resilience between ‘traditional’ and ‘non-traditional’ university students. Active Learning in Higher Education 18, 77–87. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J., Sander, P., Garzón-Umerenkova, A., Vera-Martínez, M.M., Fadda, S., Gaetha, M.L., 2021. Self-Regulation and Regulatory Teaching as Determinants of Academic Behavioral Confidence and Procrastination in Undergraduate Students. Front Psychol 12. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J., Zapata, L., Martínez-Vicente, J.M., Sander, P., Cardelle-Elawar, M., 2014. The role of personal self-regulation and regulatory teaching to predict motivational-affective variables, achievement, and satisfaction: a structural model. Front Psychol 6. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.B., Iglewicz, A., Moutier, C., 2008. A Conceptual Model of Medical Student Well-Being: Promoting Resilience and Preventing Burnout. Academic Psychiatry 32, 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Gellisch, M., Morosan-Puopolo, G., Wolf, O.T., Moser, D.A., Zaehres, H., Brand-Saberi, B., 2023. Interactive teaching enhances students’ physiological arousal during online learning. Ann Anat 247, 152050. [CrossRef]

- Gellisch, M., Wolf, O.T., Minkley, N., Kirchner, W.H., Brüne, M., Brand-Saberi, B., 2022. Decreased sympathetic cardiovascular influences and hormone-physiological changes in response to Covid-19-related adaptations under different learning environments. Anat Sci Educ 15, 811–826. [CrossRef]

- Harth, S.C., Biggs, J.S.G., Thong, Y.H., 1990. Mature-age entrants to medical school: a controlled study of sociodemographic characteristics, career choice and job satisfaction. Med Educ 24, 488–498. [CrossRef]

- Howe, A., Smajdor, A., Stöckl, A., 2012. Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training. Med Educ 46, 349–356. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.S., Gracia, J.N., 2014. Addressing Health and Health-Care Disparities: The Role of a Diverse Workforce and the Social Determinants of Health. Public Health Reports 129, 57–61. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R., Apramian, T., Kang, J.H., Gustafson, J., Sibbald, S., 2020. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of Canadian medical students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 20, 151. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, L., Putwain, D., Connors, L., Hornby-Atkinson, P., 2013. The key to successful achievement as an undergraduate student: confidence and realistic expectations? Studies in Higher Education 38, 285–298. [CrossRef]

- Oxford University Press, 2024. Oxford English Dictionary [WWW Document]. https://www.oed.com/.

- Patterson, R., Price, J., 2017. Widening participation in medicine: what, why and how? MedEdPublish 6, 184. [CrossRef]

- Potter, D., Jayne, D., Britt, S., 2020. Financial Anxiety Among College Students: The Role of Generational Status. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 31, 284–295. [CrossRef]

- Puddey, I.B., Playford, D.E., Mercer, A., 2017. Impact of medical student origins on the likelihood of ultimately practicing in areas of low vs high socio-economic status. BMC Med Educ 17, 1. [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D.W., 2008. Test anxiety and GCSE performance: the effect of gender and socio-economic background. Educ Psychol Pract 24, 319–334. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E., 1995. Mature students in higher education: II. An investigation of approaches to studying and academic performance. Studies in Higher Education 20, 5–17. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E., 1994. Mature students in higher education: I. A literature survey on approaches to studying. Studies in Higher Education 19, 309–325. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.W., 2020. Belonging, Respectful Inclusion, and Diversity in Medical Education. Academic Medicine 95, 661–664. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, C.F., Cascallar, E., Kyndt, E., 2020. Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educ Res Rev 29, 100305. [CrossRef]

- Schröpel, C., Festl-Wietek, T., Herrmann-Werner, A., Wittenberg, T., Schüttpelz-Brauns, K., Heinzmann, A., ... & Erschens, R. (2024). How professional and academic pre-qualifications relate to success in medical education: Results of a multicentre study in Germany. Plos one, 19(3), e0296982. [CrossRef]

- Selch, S., Pfisterer-Heise, S., Hampe, W., van der Bussche, H., 2021. On the attractiveness of working as a GP and rural doctor including admission pathways to medical school – results of a German nationwide online survey among medical students in their “Practical Year.” GMS Journal for Medical Education 38. [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, A.A., Puram, V. V., Miller, J.M., Sagi, V., Castañón-Gonzalez, L.A., Prasad, S., Crichlow, R., 2022. Socioeconomic Diversity of the Matriculating US Medical Student Body by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2017-2019. JAMA Netw Open 5, e222621. [CrossRef]

- Struthers, C.W., Perry, R.P., Menec, V.H., 2000. An Examination of the Relationship Among Academic Stress, Coping, Motivation, and Performance in College. Res High Educ 41, 581–592. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A., Khan, S., Sharif, W., Khalid, U., Ali, A., 2015. Association of academic stress with sleeping difficulties in medical students of a Pakistani medical school: a cross sectional survey. PeerJ 3, e840. [CrossRef]

- Zavlin, D., Jubbal, K.T., Noé, J.G., Gansbacher, B., 2017. A comparison of medical education in Germany and the United States: from applying to medical school to the beginnings of residency. Ger Med Sci 15, Doc15. [CrossRef]

- Funke F, Reips U-D. Why semantic differentials in Web-based research should be made from visual analogue scales and not from 5-point scales. Field Methods. 2012;24:310–327. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Xia, M., & Pang, W. (2021). Family socioeconomic status and Chinese high school students’ test anxiety: Serial mediating role of parental psychological control, learning resources, and student academic self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(5), 689-698.

- Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. L. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity (p.325). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Reardon, S. F. (2013). The widening income achievement gap. Educational leadership, 70(8), 10-16.

- Soharwardi, M. A., Fatima, A., Nazir, R., & Firdous, A. (2020). Impact of parental socioeconomic status on academic performance of students: A case study of Bahawalpur. Pakistan. J. Econ. Econ. Educ. Res, 21, 1-8.

- Liu, J., Peng, P., & Luo, L. (2020). The relation between family socioeconomic status and academic achievement in China: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 49-76. [CrossRef]

- Szkody, E., Hobaica, S., Owens, S., Boland, J., Washburn, J. J., & Bell, D. (2023). Financial stress and debt in clinical psychology doctoral students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 835-853. [CrossRef]

- Trombitas, K. (2012). Financial stress: An everyday reality for college students. Lincoln, NE: Inceptia.

- Xiao, H., Carney, D. M., Youn, S. J., Janis, R. A., Castonguay, L. G., Hayes, J. A., & Locke, B. D. (2017). Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychological services, 14(4), 407. [CrossRef]

- Joo, S. H., Durband, D. B., & Grable, J. (2008). The academic impact of financial stress on college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 10(3), 287-305. [CrossRef]

- Potter, D., Jayne, D., & Britt, S. (2020). Financial Anxiety Among College Students: The Role of Generational Status. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 31, 284 - 295. [CrossRef]

- Erat, S., Haluk, C., & Demirkol, K. (2016). Overconfidence in Classroom. Cadmo, 57-69. [CrossRef]

- Checchi, D., & Pravettoni, G. (2003). Self-esteem and educational attainment. Research Papers in Economics.

- Sanders, L., & Sander, P. (2007). Academic Behavioural Confidence: A comparison of medical and psychology students.

- Balogun, A. G., Balogun, S. K., & Onyencho, C. V. (2017). Test anxiety and academic performance among undergraduates: the moderating role of achievement motivation. The Spanish journal of psychology, 20, E14. [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, S. T. (2013). Comparisons of test anxiety level of senior secondary school students across gender, year of study, school type and parental educational background. IFE Psychologia: An International Journal, 21(1), 40-54.

- Potter, D., Jayne, D., & Britt, S. (2020). Financial Anxiety Among College Students: The Role of Generational Status. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 31, 284 - 295. [CrossRef]

- Benor, D., & Hobfoll, S. E. (1981). Prediction of clinical performance: the role of prior experience. Academic Medicine, 56(8), 653-8.

- Shah, R., Johnstone, C., Rappaport, D., Bilello, L. A., & Adamas-Rappaport, W. (2018). Pre-matriculation clinical experience positively correlates with Step 1 and Step 2 scores. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 707-711. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S., & Mellis, C. (2017). Practically prepared? Pre-intern student views following an education package. Advances in medical education and practice, 111-120. [CrossRef]

- Walker, B., Wallace, D., Mangera, Z., & Gill, D. (2017). Becoming ‘ward smart’medical students. The Clinical Teacher, 14(5), 336-339.

- Etherton, K., Steele-Johnson, D., Salvano, K., & Kovacs, N. (2020). Resilience effects on student performance and well-being: the role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. The Journal of General Psychology, 149, 279 - 298. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S. (2015). Resilience Building in Students: The Role of Academic Self-Efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, H., Hawe, E., & Hamilton, R. (2020). The case for using exemplars to develop academic self-efficacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45, 460 - 471. [CrossRef]

- Havnen, A., Anyan, F., Hjemdal, O., Solem, S., Riksfjord, M., & Hagen, K. (2020). Resilience Moderates Negative Outcome from Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Moderated-Mediation Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. [CrossRef]

- Mulati, Y., & Purwandari, E. (2022). The Role of Resilience in Coping with Academic Stress (A Meta-analysis Study). KnE Social Sciences, 169-181. [CrossRef]

- Duty, S., Christian, L., Loftus, J., & Zappi, V. (2016). Is Cognitive Test-Taking Anxiety Associated With Academic Performance Among Nursing Students?. Nurse Educator, 41, 70–74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).