1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance has become a pressing global health issue due to the widespread misuse and overuse of antibiotics [

1]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria and fungi are increasingly difficult to treat and pose significant threats to human, animal, and environmental health [

2]. This escalating crisis demands the development of novel antimicrobial strategies and sensitive detection systems to identify infections and reduce reliance on conventional antibiotics [

3].

One area of growing interest is the application of nanotechnology to combat AMR and improve bioanalytical sensing. Nanotechnology, which entails the manipulation of materials at the nanoscale (1–100 nm), provides a flexible foundation for creating functional materials with unique chemical, optical, and electronic properties [

4]. Due to their increased surface area relative to their volume, nanoparticles (NPs) demonstrate greater reactivity and multiple functions in comparison to their larger counterparts [

5]. In particular, nanocomposites (NCs) formed by integrating two or more nanomaterials such as metal oxides with carbon-based structures, demonstrate synergistic effects that enhance their biological and electrochemical performance [

3,

5].

Among these, carbon dots (CDs) have become a promising category of carbon-based nanomaterials because of their straightforward synthesis, low toxicity, biocompatibility, and excellent electron transfer capability [

6]. Nitrogen-doped carbon dots (NCDs), prepared from nitrogen-rich precursors such as urea, exhibit improved conductivity and enriched surface functionality, which enhance their interaction with biological analytes [

7]. When incorporated into metal oxide matrices like copper oxide (CuO), these NCDs can form hybrid nanocomposites with improved antimicrobial and electrochemical properties [

8]. CuO is particularly attractive due to its redox activity, environmental friendliness, and capacity to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contribute to microbial inhibition [

9].

Ascorbic acid is vital for human health as a key antioxidant, involved in the synthesis of collagen, the absorption of iron, and the functioning of the immune system [

10]. It is commonly added to food, beverages, medicines, and cosmetics [

11,

12]. Both deficiency and overconsumption of AA are associated with health complications, thus necessitating the accurate detection of AA in biological and food samples [

13]. The creation of sensors that are both sensitive and selective for the detection of AA is thus of great importance, particularly when combined with multifunctional nanomaterials capable of simultaneous antimicrobial action [

14,

15].

Although nanostructures based on NCDs and Ag-NCDs have been previously studied, the synthesis and application of CuO-NCD nanocomposites for dual use in AA detection and antimicrobial activity remain underexplored [

16]. From this study, we synthesized CuO-NCD NCs using a straightforward pyrolysis–precipitation method and characterized their structural, optical, and morphological properties. We further evaluated their electrochemical response to AA and antibacterial efficacy against

Staphylococcus aureus. The synthesized CuO-NCDs demonstrated high sensitivity, rapid response, and effective microbial inhibition, offering a promising platform for multifunctional biomedical and sensing applications [

17,

18].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

The following chemicals were employed: citric acid (C₆H₈O₇, ~99%), urea (CH₄N₂O), copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O, ~99%, UNI-CHEM), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, India), ascorbic acid (C₆H₈O₆, ~99), monobasic potassium phosphate (KH₂PO₄), dibasic potassium phosphate (K₂HPO₄), uric acid (C₅H₄N₄O₃), potassium chloride (KCl), ethanol (CH₃CH₂OH, ~99%), acetic acid (CH₃COOH), chitosan (C₅₆H₁₀₃N₉O₃₉), and hydrochloric acid (HCl, ~99%).

2.2. Instrumentation

Electrochemical assessments were performed utilizing a voltammetric analyzer (Epsilon EC-Ver 1.40.67, Bioanalytical System, USA) arranged in a standard three-electrode configuration: an unmodified or modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) serving as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire functioning as the counter electrode. UV-Vis spectra were collected with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (JENWAY 6705). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using a DR AWELL XRD-700 diffractometer. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements were performed with a PerkinElmer spectrometer. The structure of the samples was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JCM-6000Plus).

2.3. Synthesis CuO Nanoparticles (CuO NPs)

CuO NPs were synthesized by using a modified precipitation technique [

19,

20]. Briefly, 2.4 g (0.1 M) of Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. Separately, 0.1 M NaOH was prepared, and the pH level was adjusted to reach 9. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 2 h, filtered and subsequently washed using distilled water and ethanol. The resultant precipitate was then dried at a temperature of 60 °C for 4 h.

2.4. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nano-dots (NCDs)

NCDs were prepared by a modified pyrolysis method [

21,

22]. A mixture of 1.0 g of citric acid and 0.5 g of urea was dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water and then heated in a microwave oven at 200 °C for a duration of 20 min. The solid product was dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water, then filtered and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min to eliminate larger particles.

2.5. Synthesis of CuO-NCD Nanocomposites (NCs)

CuO-NCD NCs were synthesized following a literature method with modifications [

23]. CuO NPs (400 mg) were spread out in 50 mL of distilled water and subjected to sonication for 30 min. Subsequently, 5 mL of NCD solution was incorporated and mixed for 6 h. The product was collected by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 40 min), cleaned with ethanol, and dried at 80 °C for 2 h.

2.6. Electrochemical Procedure

2.6.1. Preparation of Supporting Electrolyte

A phosphate buffer solution (PBS) with a concentration of 0.1 M and a pH range of 2 to 8 was created by mixing 6.8 g of KH₂PO₄ and 8.7 g of K₂HPO₄ in distilled water. To achieve the desired pH, adjustments were made using 1 M HCl or NaOH.

2.6.2. Preparation of Standard Solutions

A 1 mM stock solution of ascorbic acid (AA) was prepared in 0.1 M PBS. Working solutions of varying concentrations were obtained by serial dilution.

2.6.3. Preparation of Electrodes

The GCE was polished using 0.3 µm alumina slurry, washed, sonicated in distilled water, and air-dried. For modification of literature [

24], 0.027 g of each nanomaterial (NCD, CuO, CuO-NCD) was mixed into a combination of 40 mL of ethanol, 10 mL of acetic acid, 0.1 g chitosan and 50 mL distilled water and sonicated for 1 h. Subsequently, 5 µL of each suspension was drop-cast onto the GCE and dried at room temperature for 24 h [

25].

2.7. Optimization of Experimental Parameters

The pH effect on AA detection was studied in PBS (pH 2–8) employing cyclic voltammetry (CV) at a scanning rate of 100 mV·s⁻¹. The pH that produced the highest oxidation peak current was chosen for additional examination.

2.8. Interference Study

Selectivity was evaluated by testing common interfering species (1 mM citric acid, uric acid, and KCl) in 1 mM AA solutions. Changes in oxidation current were analyzed as per the literature protocol.

2.9. Real Sample Analysis

Orange juice and vitamin C tablet samples were used to assess practical performance. Orange juice was obtained by pressing and centrifuging fresh fruits. Vitamin C tablets were powdered, and 0.02 g was dissolved in 100 mL PBS. A 5 µL aliquot was further diluted in 5 mL PBS for CV analysis. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The recovery percentage was determined using the subsequent Equation (1):

2.10. Antimicrobial Activity Test

Antibacterial and antifungal tests were conducted at the Department of Biology, Jimma University. Mueller–Hinton agar was used to culture

Salmonella typhi,

Bacillus cereus,

Staphylococcus aureus, and

Escherichia coli. Discs (6 mm) soaked in nanomaterial solutions (12–200 mg/mL in DMSO) were placed on inoculated plates. Gentamicin and clotrimazole served as positive controls for the purpose of assessing antibacterial and antifungal properties, respectively. Plates were maintained at 37 °C for 24 h for bacteria and at 27 °C for 48 h for fungi [

26].

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dots (NCDs)

NCDs were produced through a straightforward microwave-assisted technique utilizing urea and citric acid as the sources of carbon and nitrogen, respectively. A mixture of urea and citric acid was exposed to microwave irradiation at 700 W. The solution turned dark brown upon heating, showing the creation of carbon dots, as documented in existing research [

27].

3.2. Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles (CuO NPs) and CuO-NCD Nanocomposites (NCs)

CuO NPs were prepared by dissolving Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O in distilled water, succeeded by the incorporation of NaOH, which changed the solution from blue to deep blue suggesting the formation of a copper complex [

28]. Upon heating, a black precipitate formed, indicating the formation of CuO NPs.

For CuO-NCD NCs, NCDs were added during the synthesis process. The functional groups in NCDs acted as agents for capping and reduction, preventing agglomeration and promoting the formation of stable nanocomposites. The incorporation of NCDs into CuO nanoparticles was confirmed utilizing various characterization techniques including UV–Vis spectroscopy, FTIR, XRD, and SEM [

29].

3.3. UV–Vis Absorption and Band Gap Determination

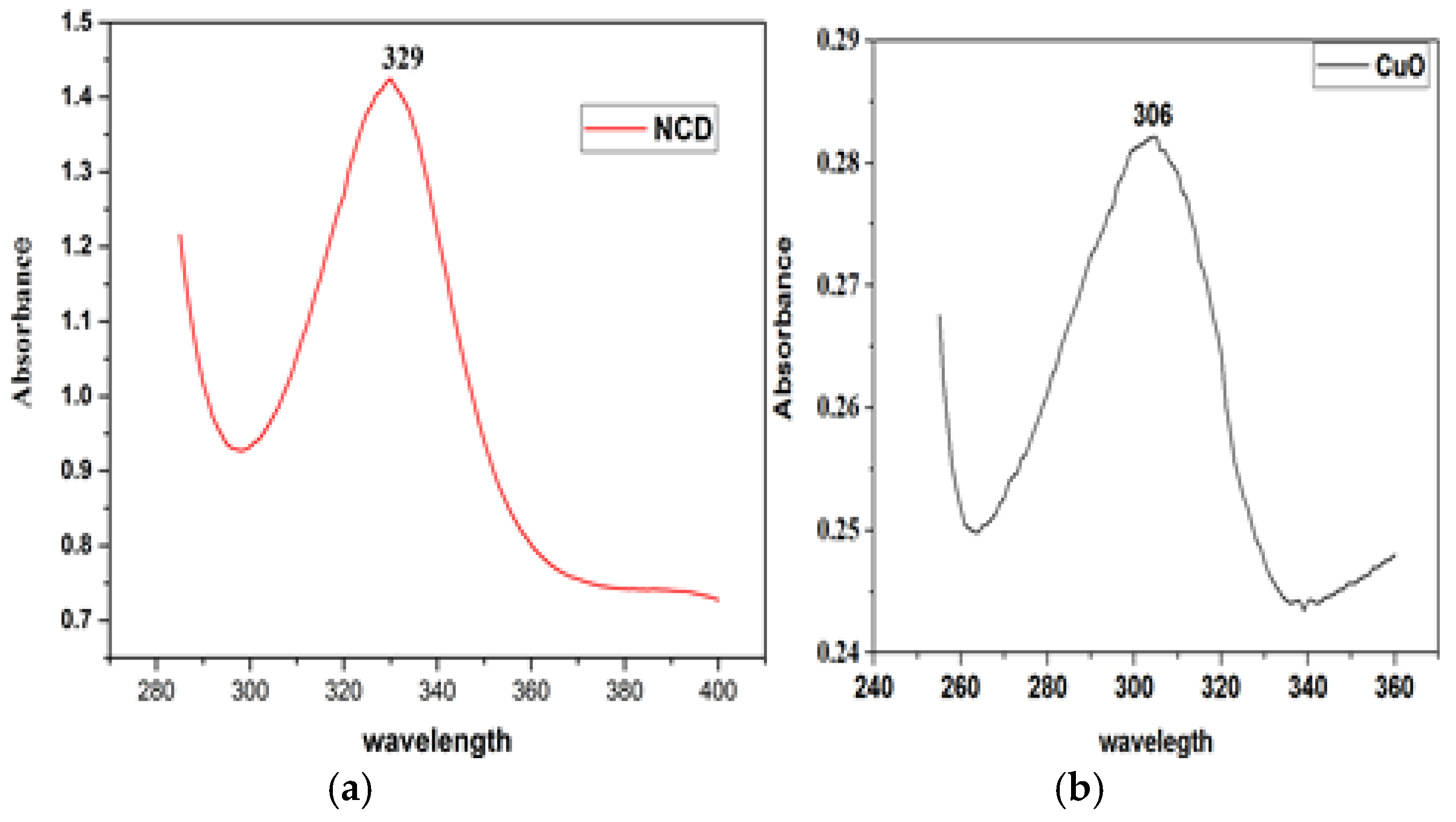

The optical properties of CuO NPs, NCDs, and CuO-NCD NCs were investigated using UV–Vis spectroscopy (

Figure 1). CuO NPs a distinct absorption peak at 306 nm (

Figure 1b), while NCDs show a strong absorption peak at 329 nm (

Figure 1a), attributed to the π–π transition of C=C bonds. The CuO-NCD NCs showed a redshifted absorption peak at 370 nm, indicating successful interaction between CuO and NCDs (

Figure 1c).

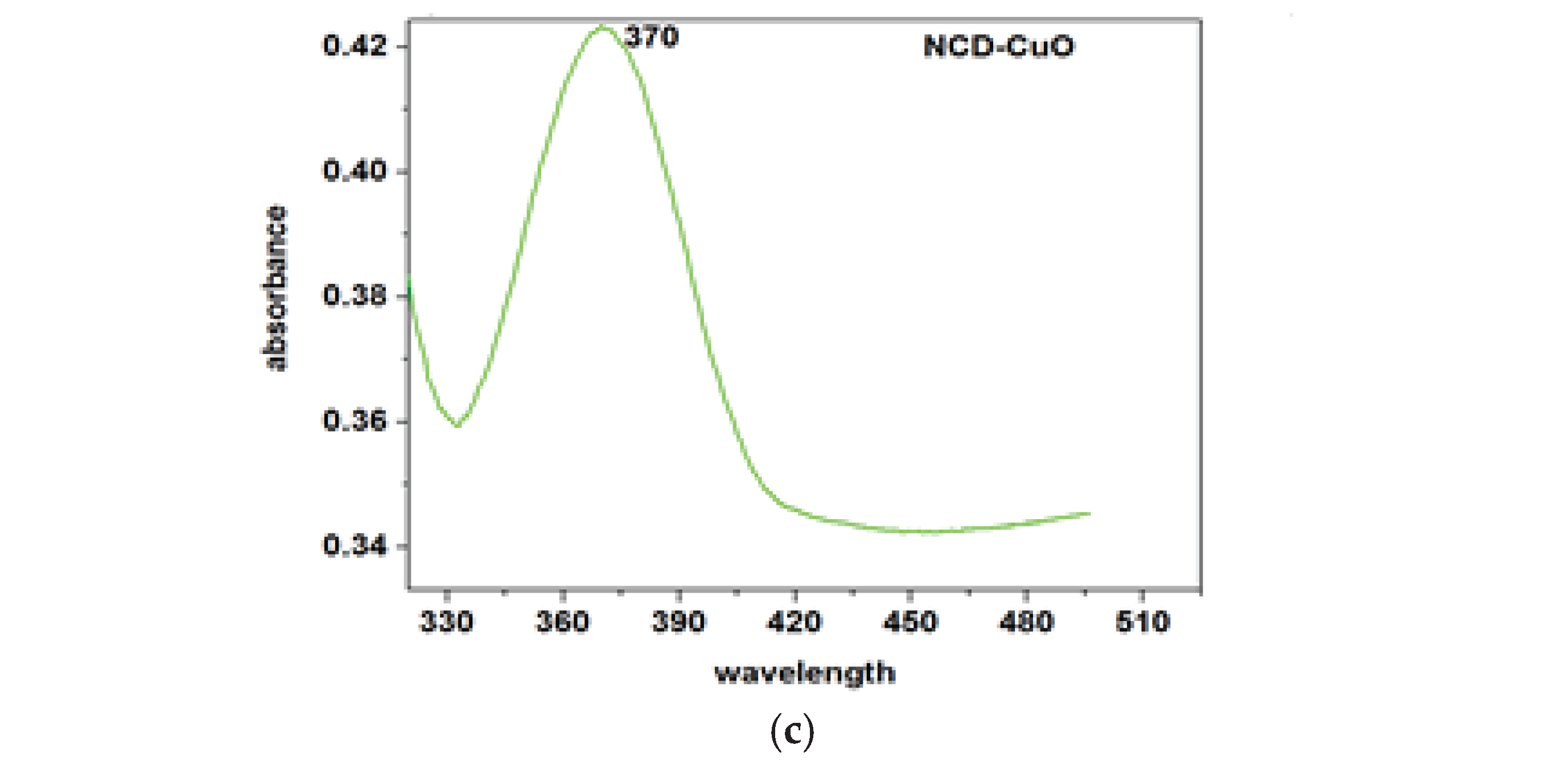

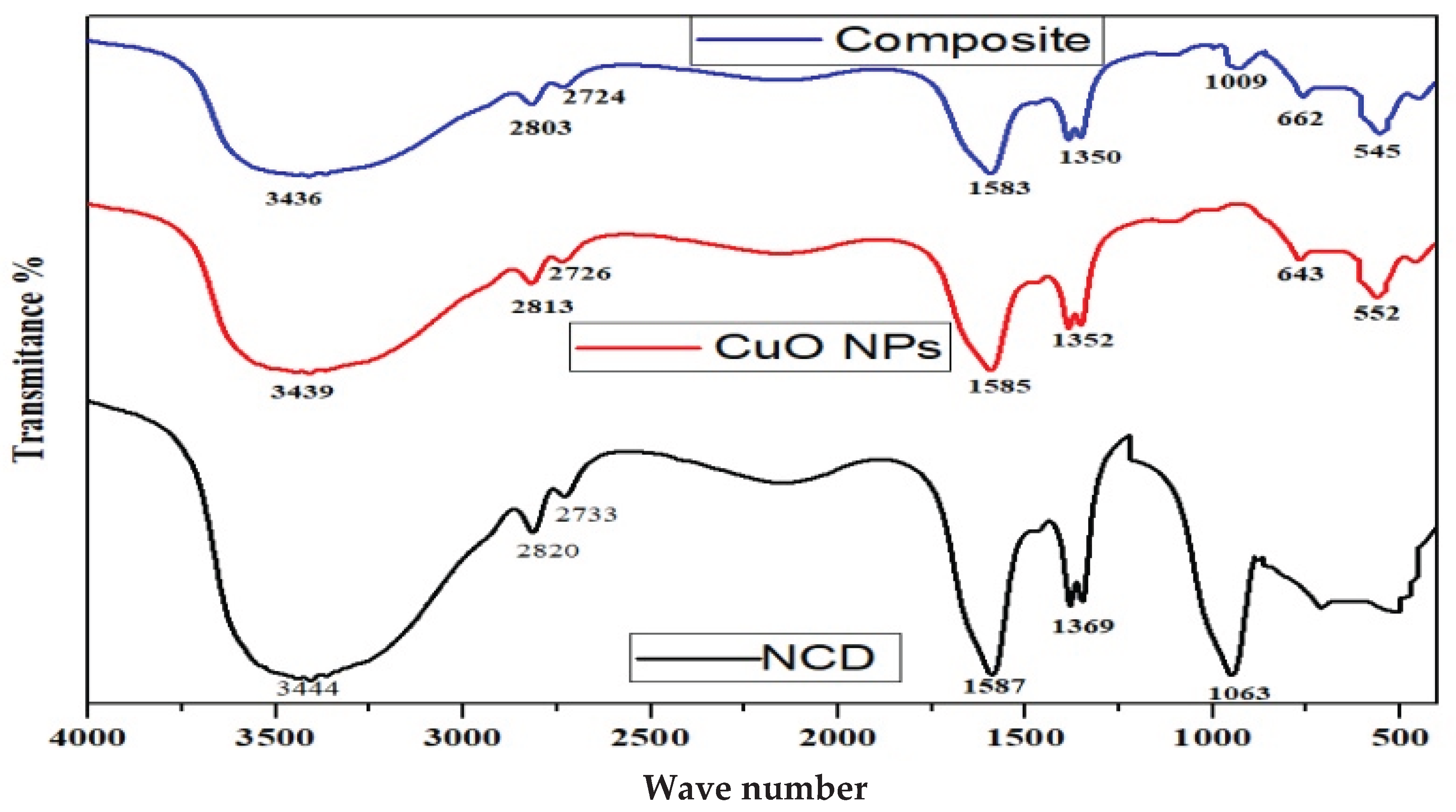

The energies of the band gaps were determined through the use of Tauc plots (

Figure 2). CuO NPs showed a band gap of 3.05 eV (

Figure 2a) and CuO-NCD NCs 2.6 eV (

Figure 2b). The decreased band gap of CuO-NCD NCs suggests strong interfacial electronic interactions, which enhance electron–hole pair separation, making them suitable for electrochemical sensing applications.

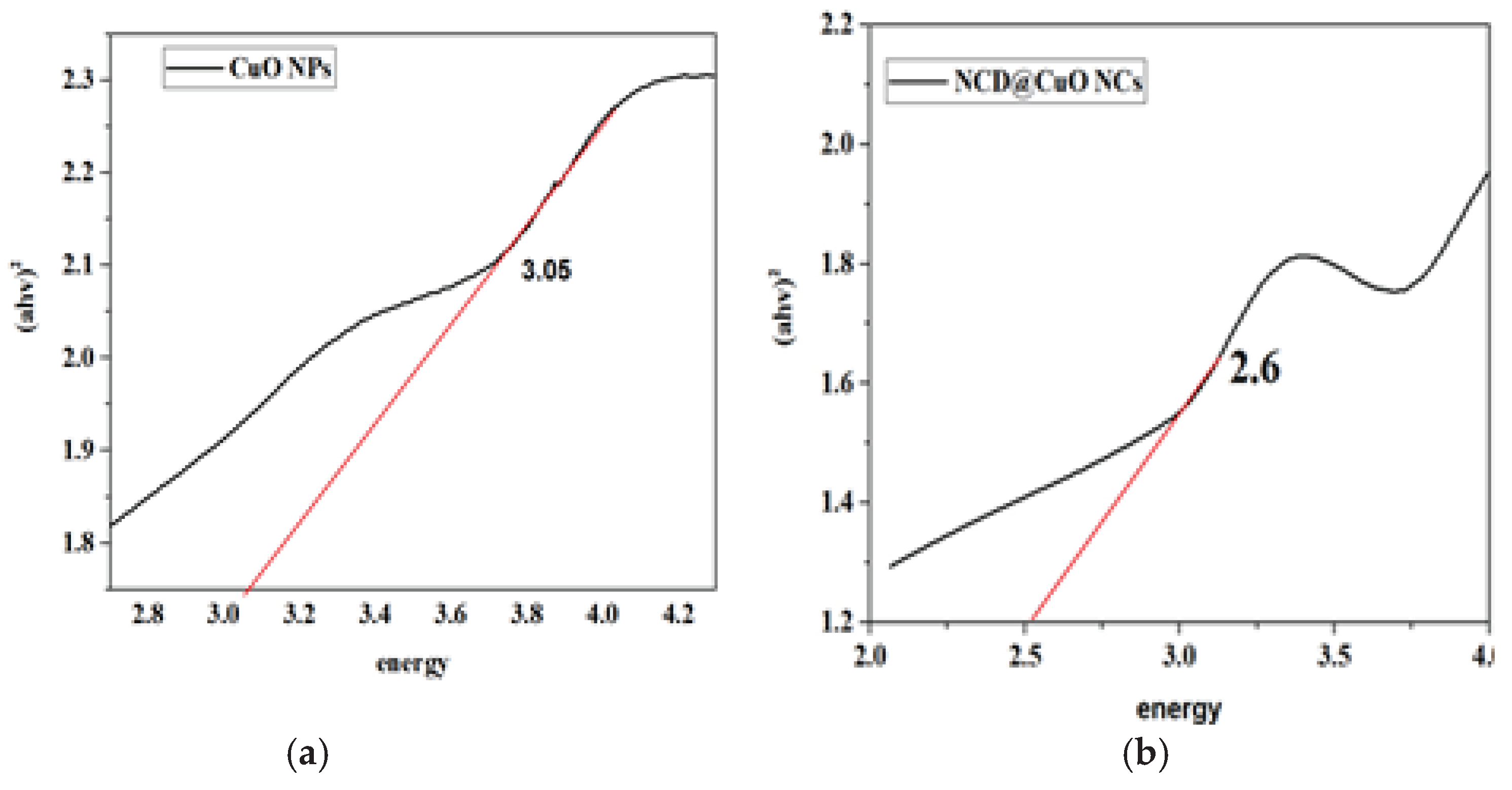

3.4. FTIR Spectral Analysis

Figure 3 presents the FT-IR spectra of the nanomaterials (NMs) recorded between 4000–400 cm⁻¹. Broad bands at 3200–3500 cm⁻¹ are attributed to N–H and O–H stretching vibrations, likely due to hydrogen bonding and adsorbed water on NPs and NCs. In CuO-NCD NCs, the N–H/O–H peak shifted from 3444 to 3436 cm⁻¹ with decreased intensity, suggesting interaction between NCDs and CuO NPs, reduced electron density, and formation of CuO-NCD NCs. Functional groups in NCDs originate mainly from urea and citric acid. A sharp peak at 1063 cm⁻¹ indicates the existence of C–C structures, while the peak at 552 cm⁻¹ corresponds to Cu–O stretching, consistent with the literature. Peaks between 500–700 cm⁻¹ represent CuO NPs and CuO-NCD NCs vibrations, also aligning with reported data.

3.4. XRD Analysis

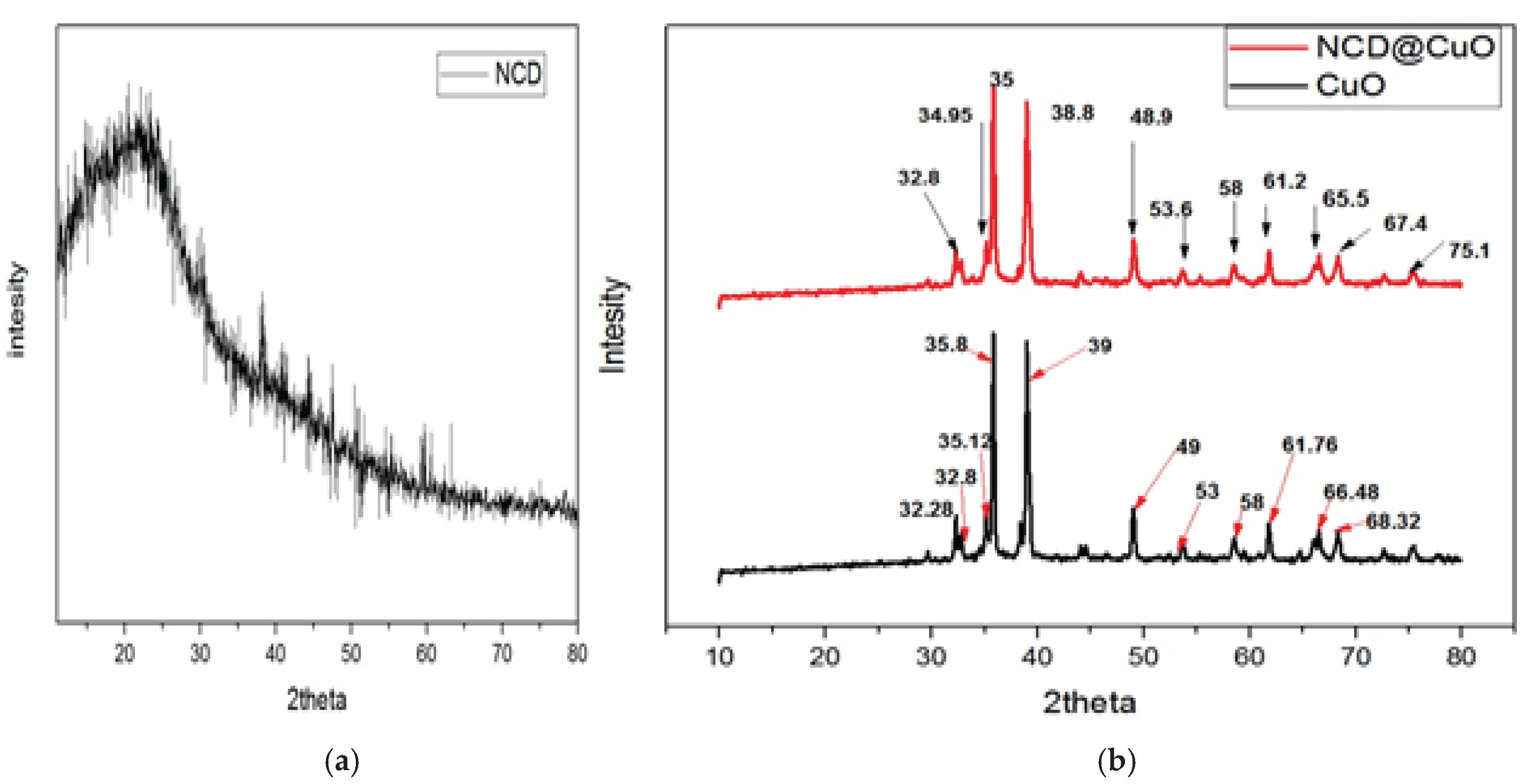

XRD patterns (

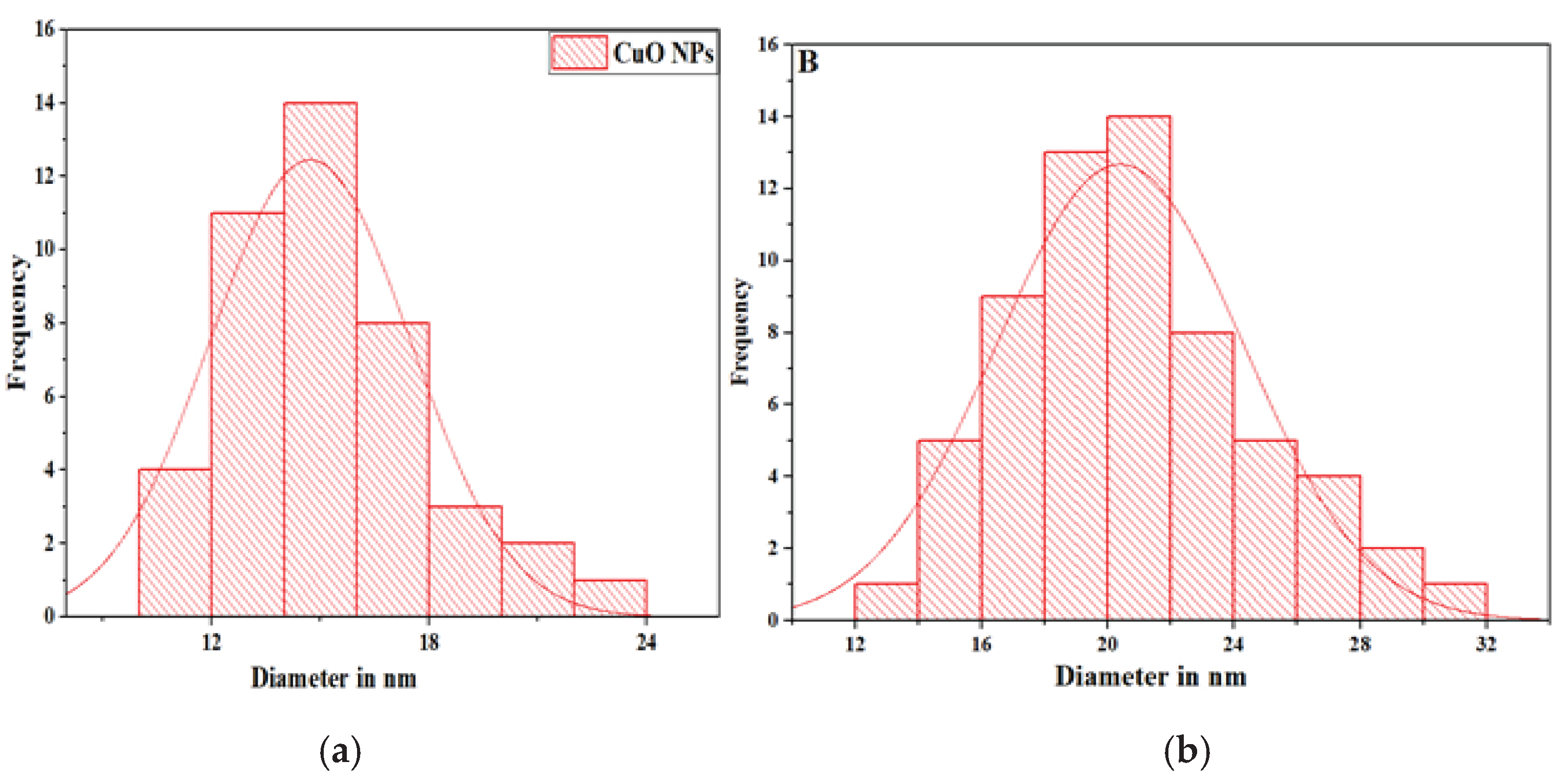

Figure 4) confirmed the crystalline nature of CuO and the amorphous nature of NCDs. CuO NPs displayed distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 32.28, 32.8, 35.12, 35.8, 39, 49.04, 53.68, 58.55, 61.76, 66.48, and 68.32°, related to (110), (111), (200), (202), (020), (202), (113), (310), (220), (311), and (222) of monoclinic CuO (JCPDS PDF file No. 89-5895). The CuO-NCD NCs showed similar peaks with slight broadening and reduced intensity, attributed to the amorphous NCD matrix. Crystallite sizes were calculated using the Debye–Scherrer Equation (2), which yielded 20 nm for CuO NPs and 23 nm for CuO-NCD NCs, indicating a reduced grain size due to NCD embedding.

3.5. SEM Analysis

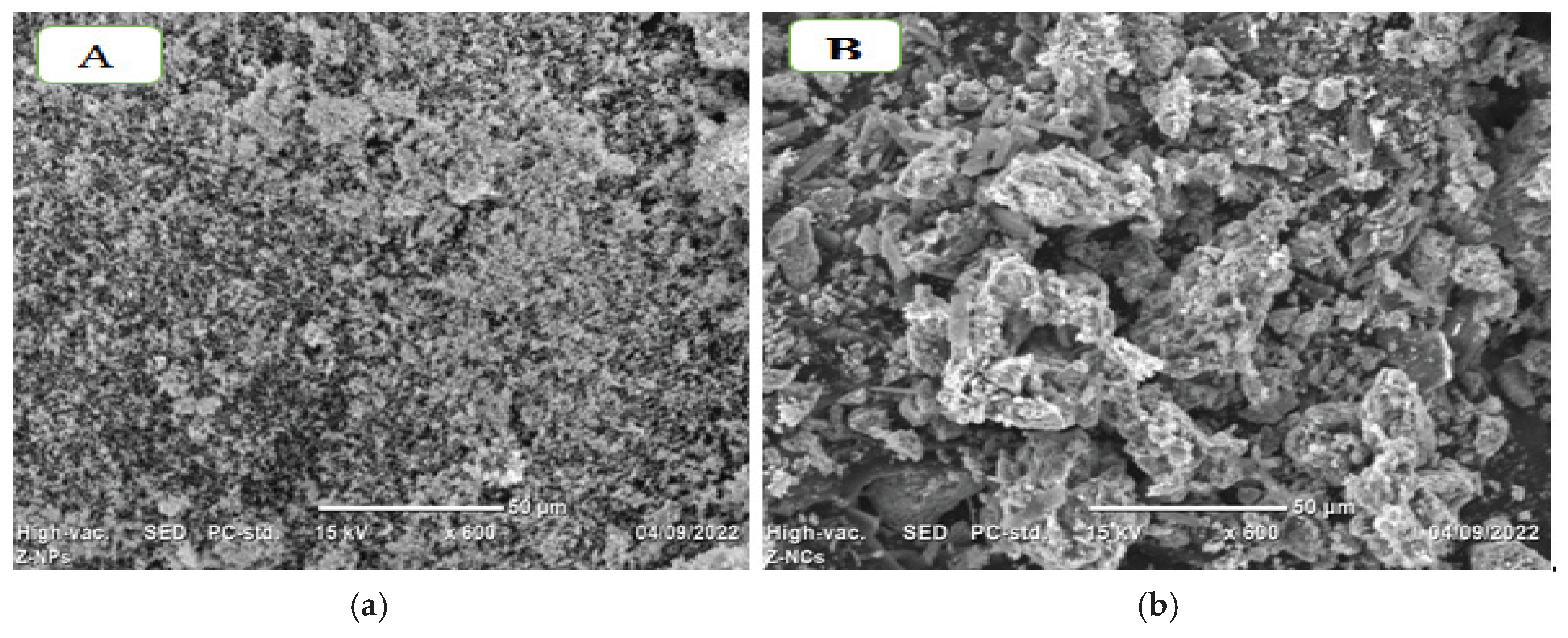

SEM images (

Figure 5) revealed spherical morphologies for CuO and CuO-NCDs. CuO NPs appeared agglomerated, while CuO-NCDs exhibited uniform, spherical nanocomposites (

Figure 5b). CuO-NCD NCs exhibited a heterogeneous mixture of rod-like and spherical particles, indicating morphological alteration resulting from the interaction with NCD. This structural change enhances electrochemical surface area and conductivity. The histogram (

Figure 6) illustrates that the average particle size distribution pattern of CuO NPs was smaller than that of CuO-NCD NCs.

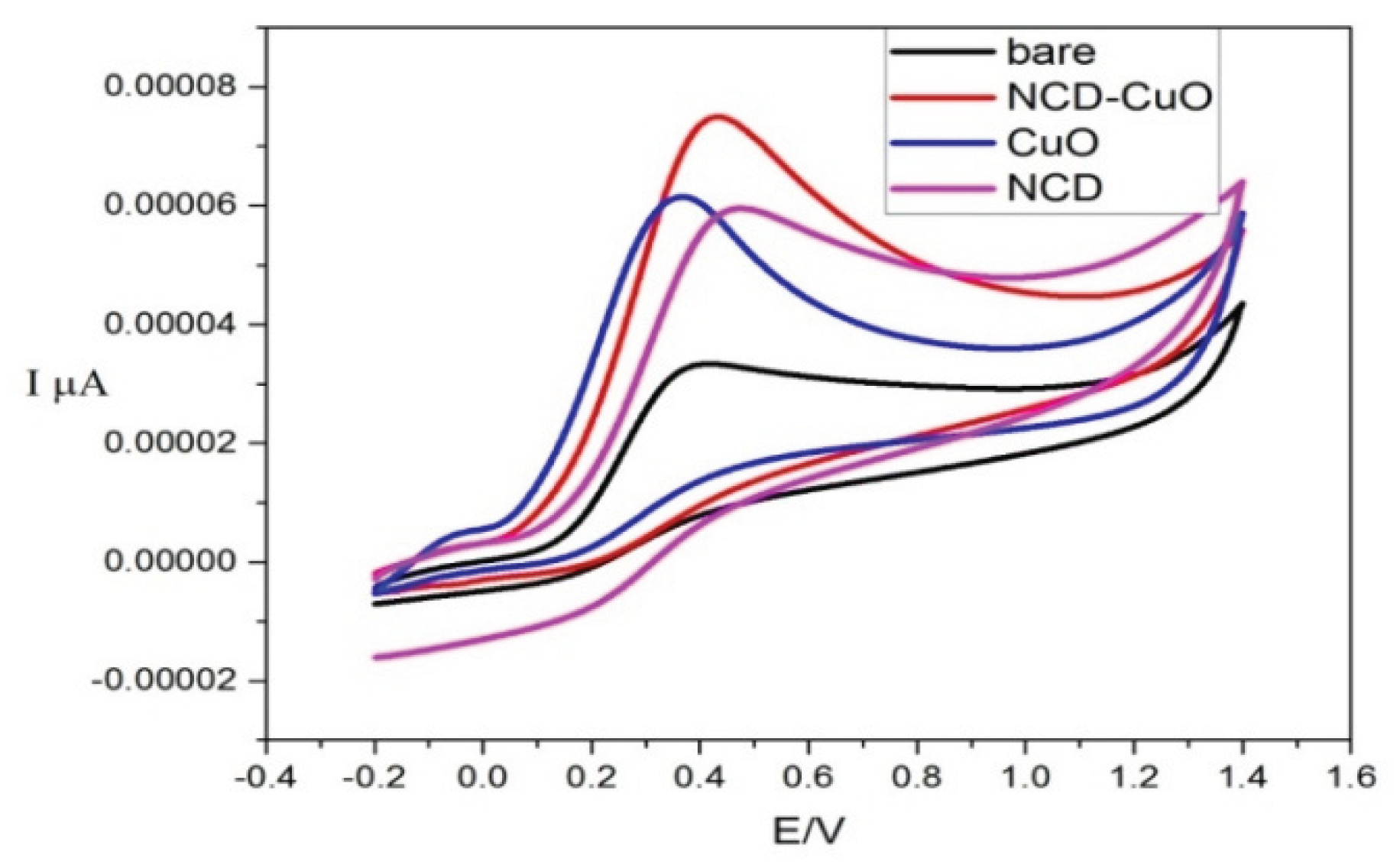

3.6. Electrochemical Characterization

Figure 7 presents the cyclic voltammetric responses for the electrochemical oxidation of 1 mM ascorbic acid at the bare electrode, NCD, CuO, and CuO-NCD. A significant increase in the anodic peak current was observed at the NCD, CuO, and CuO-NCD-modified electrodes in comparison to the bare electrode. The CuO-NCD nanocomposite exhibited the highest anodic peak current among all tested materials.

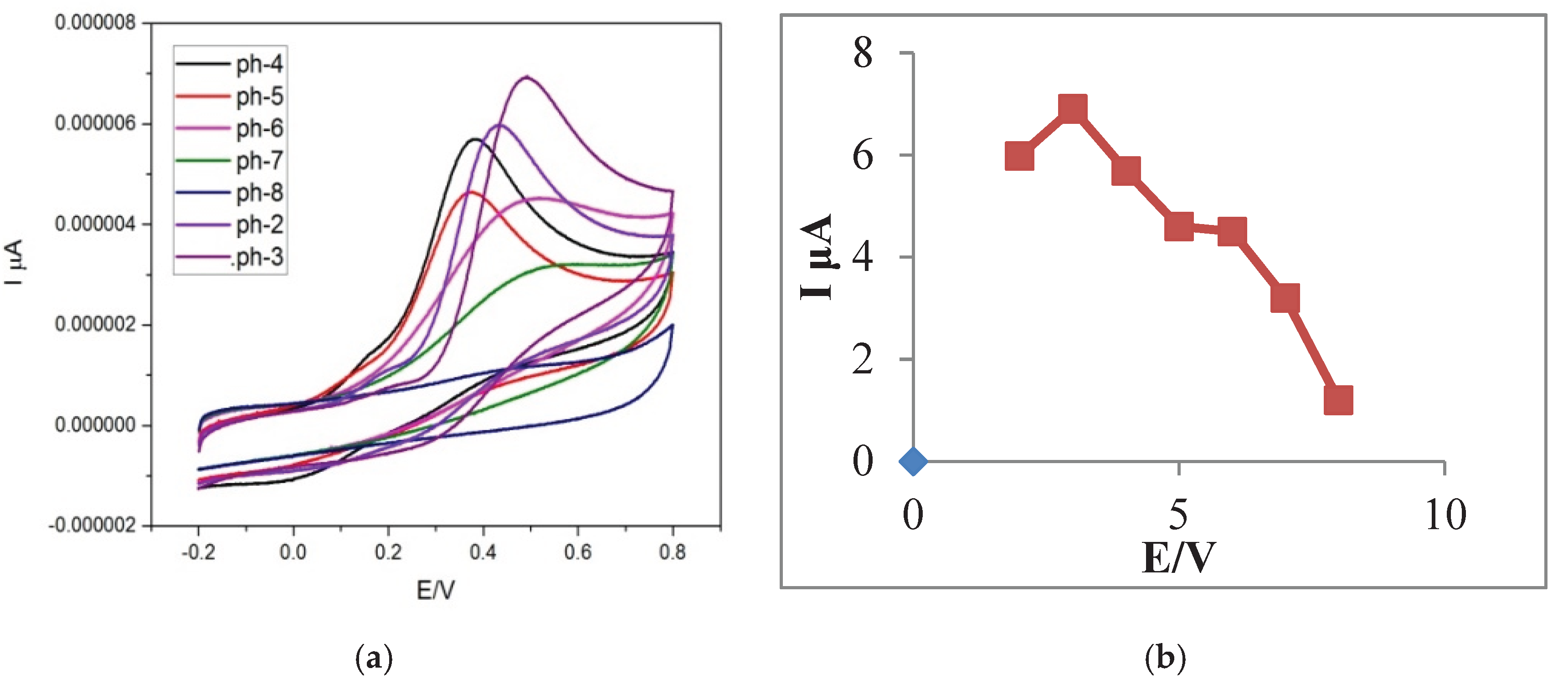

3.7. Effect of pH

At various pH values, distinct currents and potentials were measured. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the peak current for ascorbic acid (AA) showed a significant increase as the pH rose from 2.0 to 3.0, followed by a decrease from pH 3.0 to 8.0. The peak current reached its maximum at a pH of 3.0, indicating it as the optimal condition for sensitive and reliable detection of AA.

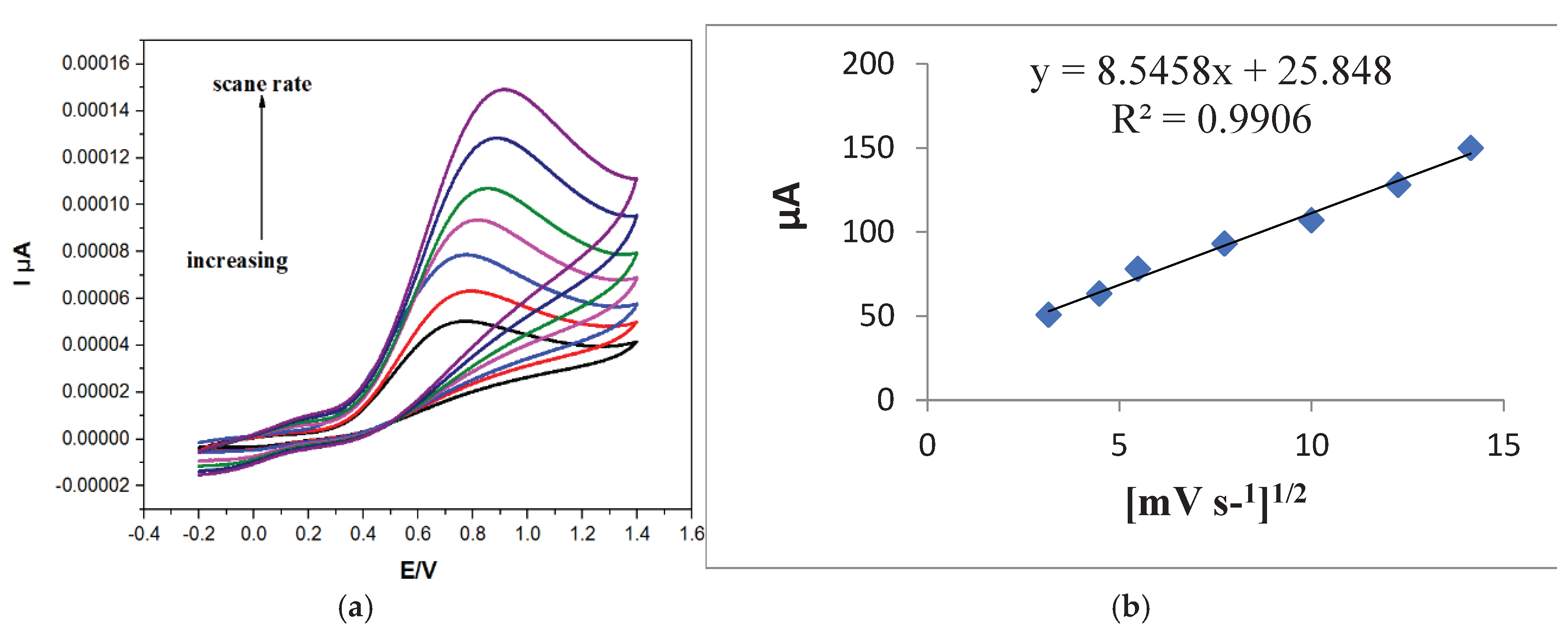

3.8. Effect of Scan Rate

Figure 9a displays the cyclic voltammetry of AA at scan rates ranging from 10 to 200 mV·s⁻¹ (

Figure 9a). The oxidation peak current increased with scan rate, and a shift toward more positive potential was observed A linear correlation was observed between the square root of the scan rate and the oxidation peak current, with a correlation coefficient of R² = 0.9906 (

Figure 9b), indicating diffusion-controlled electrochemical behavior [

30].

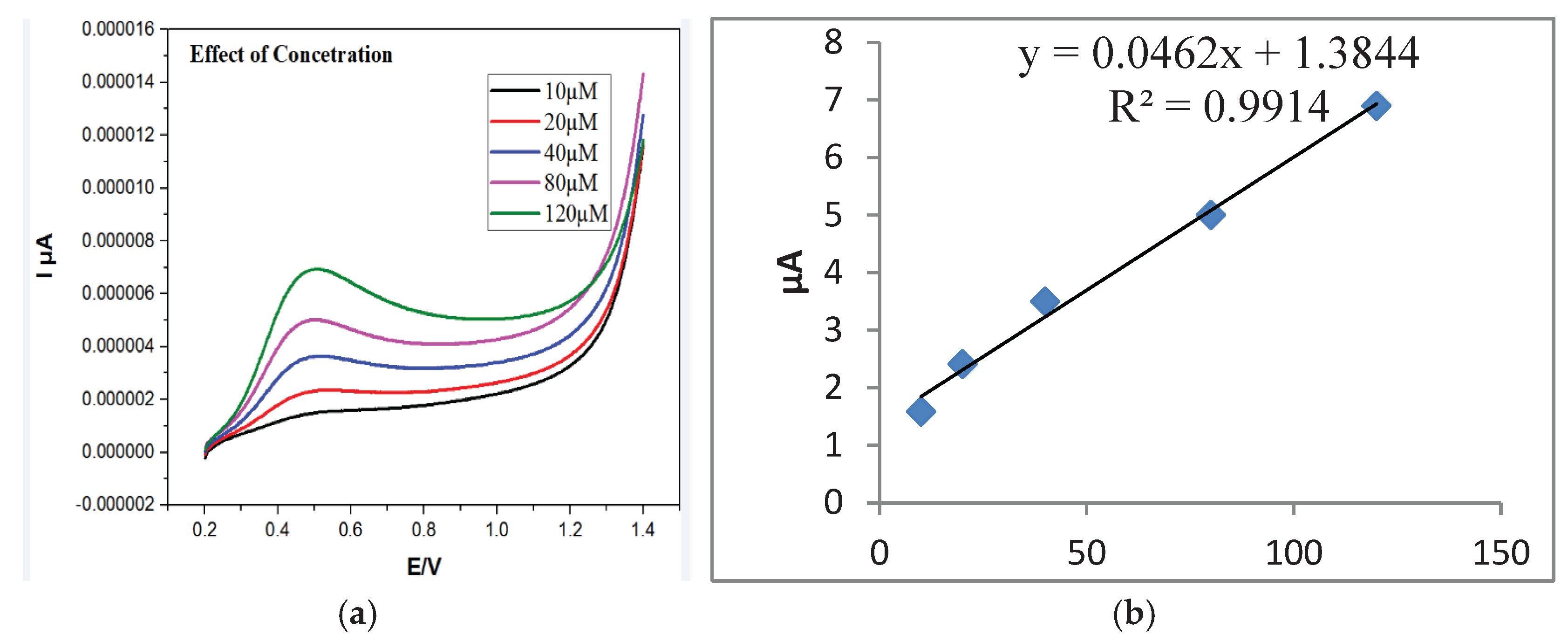

3.9. Effect of Concentration

As illustrated in

Figure 10a, raising the level of AA from 5 to 120 µM resulted in a corresponding increase in peak current. The calibration plot followed the linear regression equation y = 0.0462x + 1.3844, with R² = 0.9914 (

Figure 10b), and a detection limit of 2.56 µM was calculated.

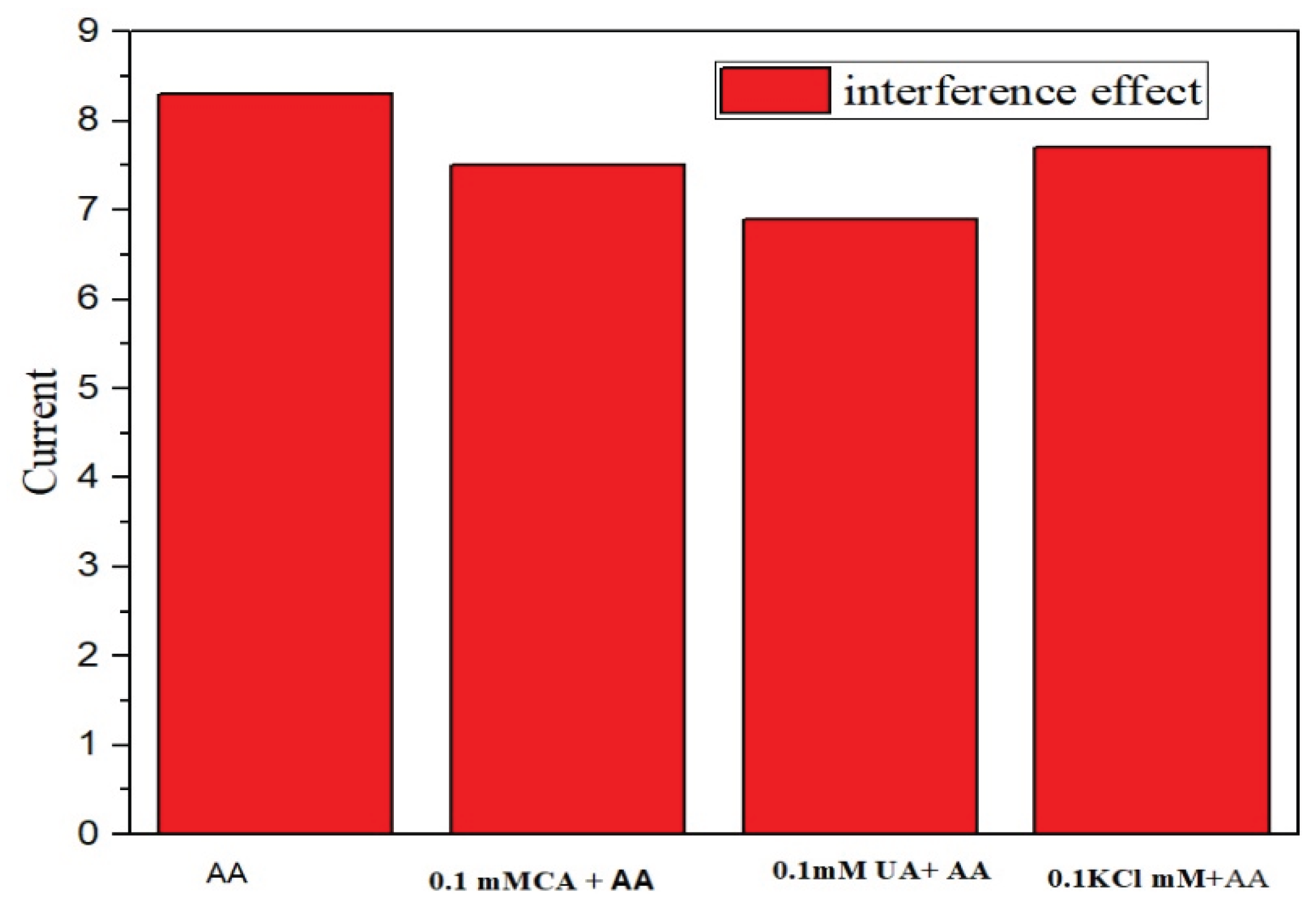

3.10. Interference Effect

The influence of common interferents such as uric acid, citric acid, and potassium chloride on AA detection was tested, as shown in

Figure 11. The addition of 1 mM AA significantly affected the current response, while the presence of interferents showed negligible impact, confirming high selectivity.

3.11. Stability of CuO-NCD NC Sensor

Stability testing over nine days showed that the sensor retained 71.4%, 62.5%, and 50.6% of its initial current response after 3, 6, and 9 days, respectively, when stored at room temperature.

3.12. Real Sample Analysis

The sensor was used to detect AA in vitamin C tablets and orange juice using the standard addition method. Recovery rates ranged from 92.99% to 109.45%, as shown in

Table 1, indicating satisfactory accuracy and reliability.

3.13. Antibacterial Activity

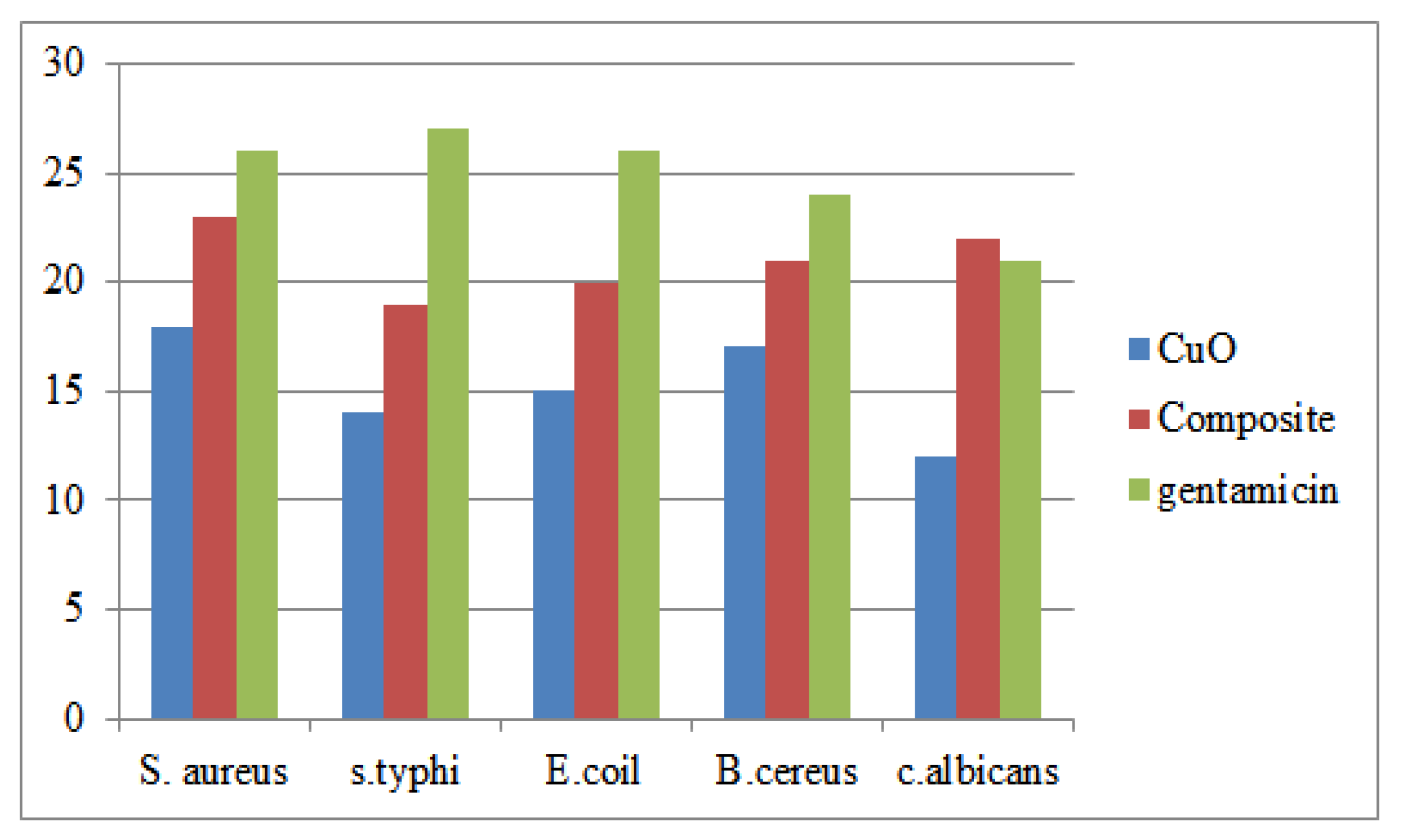

The antibacterial properties of NCD, CuO NPs, and CuO-NCD NCs were evaluated against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria using the disk diffusion method (

Figure 12). CuO and CuO-NCD exhibited increasing inhibition zones with increasing concentration (12–200 mg/mL), while NCD showed minimal activity.

4. Discussion

The effective synthesis of CuO nanoparticles (CuO NPs), nitrogen-doped carbon dots (NCDs), and CuO-NCD nanocomposites (NCs) was confirmed using a range of characterization techniques. Each provided complementary insights into the structural, optical, and electrochemical properties of the synthesized nanomaterials.

UV-Vis spectral analysis (

Figure 1a–c) confirmed the distinct optical absorption behaviors of the individual and composite nanomaterials. NCDs exhibited an absorption peak at 329 nm, attributed to

n–π⁎ transitions, while CuO NPs showed a peak at 306 nm, in line with previously reported literature [

31]. The CuO-NCD NCs revealed a red-shifted peak at 370 nm, confirming successful composite formation [

32]. This shift is likely due to interactions between CuO NPs and the functional groups that contain oxygen on the surface of the NCDs [

33]. Moreover, the narrow and sharp nature of the peaks indicates the presence of smaller nanoparticles with good dispersion and minimal aggregation [

34]. The band gap analysis (

Figure 2) further supported the nanocomposite formation. CuO NPs had a calculated band gap of 3.05 eV, which exceeds that of bulk CuO (1.5 eV), indicating the quantum confinement effect in nanoscale structures [

35]. In contrast, CuO-NCD NCs exhibited a lower band gap of 2.6 eV, attributed to an increased particle size and the formation of the nanocomposite structure [

36]. This red-shift in the absorption edge confirms the synergistic effect between CuO and NCDs, which may enhance photocatalytic and electrochemical performance [

37].

FT-IR analysis (

Figure 3) provided molecular-level evidence of nanocomposite formation. The broad absorption bands between 3200–3500 cm⁻¹ correspond to the O–H and N–H stretching vibrations, indicative of surface hydroxyl and amine groups. A shift from 3444 to 3436 cm⁻¹ and a decrease in peak intensity in CuO-NCD NCs compared to NCDs suggested successful interaction between CuO NPs and NCDs, likely through hydrogen bonding and coordination. The appearance of peaks at 552 cm⁻¹ and in the 500–700 cm⁻¹ region confirm Cu–O bonding and the presence of CuO, consistent with previous reports [

38].

XRD analysis (

Figure 4) demonstrated that CuO NPs exhibited clear crystalline peaks corresponding to monoclinic CuO with no evidence of impurity phases. CuO-NCD NCs retained similar diffraction patterns, suggesting that the addition of NCDs did not disrupt the crystalline nature of CuO. However, peak intensity reduction in the nanocomposite indicates partial masking of CuO by the carbon matrix [

39]. The crystallite sizes of CuO NPs and CuO-NCD NCs were estimated to be 20 nm and 23 nm, respectively using the Debye-Scherrer equation.

SEM analysis (

Figure 5) revealed morphological differences between CuO NPs and CuO-NCD NCs. CuO NPs displayed uniformly distributed particles, whereas the nanocomposites showed mixed rod-like and spherical structures [

40]. The increase in average particle size in CuO-NCD NCs is consistent with the band gap reduction and indicates successful integration of NCDs into the CuO matrix.

Finally, electrochemical studies (

Figure 7) showed that CuO-NCD NCs exhibited enhanced electrochemical activity for the oxidation of ascorbic acid (AA), evidenced by a significant increase in anodic peak current compared to bare and individual-modified electrodes. This enhancement is attributed to improved electron transfer kinetics due to the synergistic interaction between CuO and NCDs, resulting in increased surface area and conductivity [

41]. The observed peak potential shift of AA oxidation toward negative values that correspond with rising pH levels indicate the involvement of protons in the oxidation process at the CuO-NCD surface [

42]. The decrease in peak current at higher pH is likely due to reduced catalytic activity in alkaline conditions, possibly caused by fewer available protons and catalytic sites [

43].

The linearity between the oxidation peak current and the square root of the scan rate suggests that the electro-oxidation of AA on the CuO-NCD-modified electrode is a diffusion-controlled irreversible process [

44]. This behavior aligns with electrochemical theory and supports the efficient electrocatalytic capability of the CuO-NCD nanocomposite. The strong linearity and low detection limit confirm the high sensitivity of the CuO-NCD/GCE sensor toward AA detection. The reproducible response across concentrations demonstrates good sensor stability and potential for quantitative applications [

45].

The minimal change in the oxidation current in the presence of interferents indicates that the sensor maintains strong selectivity for AA. This is essential for real-sample analysis where multiple electroactive species may coexist [

46]. The sensor exhibits moderate stability over time. The gradual decline in current response may be due to surface fouling or partial degradation of the active material, but performance remains acceptable for short- to medium-term applications. The high recovery rates confirm the practical applicability of the CuO-NCD sensor in real sample matrices. The sensor effectively detects AA in complex samples without significant interference from other substances.

The enhanced antimicrobial activity of CuO and CuO-NCD NCs compared to NCD alone is attributed to their ability to generate reactive oxygen species and interact with bacterial membranes [

47]. Gram-positive bacteria were more susceptible due to differences in cell wall composition. The results suggest the effectiveness of CuO-NCD NCs as antimicrobial agents, consistent with literature findings [

48].

5. Conclusions

In this study, nitrogen-doped carbon dots (NCDs) and copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) were effectively synthesized from citric acid, urea, and copper nitrate using pyrolysis and precipitation methods, respectively. The synthesized nanomaterials were characterized for their structural and morphological properties using UV-Vis, FT-IR, XRD, and SEM analysis techniques. UV-Vis spectroscopy indicated a red shift in the absorption peak for the CuO-NCDNCs compared to individual components, with calculated band gap energies of 3.05 eV for CuO NPs and 2.6 eV for CuO-NCD NCs. FT-IR analysis confirmed the presence of functional groups responsible for surface capping and stabilization, while XRD patterns indicated the crystalline nature and nanoscale dimensions of both NPs and NCs. SEM images showed spherical and rod-like morphologies, with an increase in particle size for the NCs.

Electrochemical studies demonstrated enhanced performance of the CuO-NCD-modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) toward the detection of ascorbic acid (AA). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) results indicated that the nanocomposite-modified electrode exhibited a higher effective surface area and rate constant compared to other modified electrodes. Under optimized conditions (pH 3, applied potential +0.4 V), the sensor showcased a linear detection range of 5–120 µM for AA with a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.56 µM. The sensor also demonstrated selectivity toward AA when common interfering substances were present and retained 71% of its initial response after 9 days, indicating moderate stability.

Furthermore, the CuO-NCD NCs exhibited strong antimicrobial effectiveness against various bacterial and fungal species, with particularly significant inhibition observed at higher concentrations. The results indicated that the synthesized CuO-NCD NCs possess promising electrochemical and antimicrobial properties, making them potential candidates for biosensor applications and antimicrobial agents.

Author Contributions

Z.H.R. (Zerfu Haile Robi) was involved in experimental work and methodology design, G.G.M. (Guta Gonfa Muleta) and D.J.N. (Dhugassa Jabesa Nemera) contributed to supervision of the experiment. T.E.G. (Tekileab Engida Gebremichael) contributed to data analysis and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kilari, V.B.; Oroszi, T. The Misuse of Antibiotics and the Rise of Bacterial Resistance: A Global Concern. Pharmacology & Pharmacy 2024, 15, 508–523. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, T.M.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Khusro, A.; Zidan, B.R.M.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K.; Ripon, M.K.H.; Gajdacs, M.; Sahibzada, M.U.K.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. J Infect Public Health 2021, 14, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, P. Antibiotic resistance and a dire need for novel and innovative therapies: The impending crisis. Syncytia 2023, 1, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N.; Jha, D.; Roy, I.; Kumar, P.; Gaurav, S.S.; Marimuthu, K.; Ng, O.T.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Verma, N.K.; Gautam, H.K. Nanobiotics against antimicrobial resistance: harnessing the power of nanoscale materials and technologies. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, K.; Tamrakar, R.K.; Thomas, S.; Kumar, M. Surface functionalized nanoparticles: a boon to biomedical science. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2023, 380, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ragib, A.; Al Amin, A.; Alanazi, Y.M.; Kormoker, T.; Uddin, M.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Barai, H.R. Multifunctional carbon dots in nanomaterial surface modification: a descriptive review. Carbon Research 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Baul, A.; Amar, A.; Wadhwa, R.; Kumar, S.; Varma, R.S. Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Pathways to Photoluminescent Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs). Nanomaterials (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Malik, S.; Ali, N.; Khan, A.; Bilal, M.; Rasool, K. Covalent and Non-covalent Functionalized Nanomaterials for Environmental Restoration. Top Curr Chem (Cham) 2022, 380, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreslassie, Y.T.; Gebremeskel, F.G. Green and cost-effective biofabrication of copper oxide nanoparticles: Exploring antimicrobial and anticancer applications. Biotechnol Rep (Amst) 2024, 41, e00828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, A.; Moldoveanu, E.-T.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Vitamin C: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role in Health, Disease Prevention, and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Riaz, S.; Khalid, W.; Fatima, M.; Mubeen, U.; Babar, Q.; Manzoor, M.F.; Zubair Khalid, M.; Madilo, F.K. Potential of ascorbic acid in human health against different diseases: an updated narrative review. International Journal of Food Properties 2024, 27, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.L.; Bragança, V.A.; Pacheco, L.V.; Ota, S.S.; Aguiar, C.P.; Borges, R.S. Essential features for antioxidant capacity of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). Journal of molecular modeling 2022, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Catchpole, A.; Day, M.P.; Hill, S.; Martin, N.; Patriarca, M. Atomic spectrometry update: review of advances in the analysis of clinical and biological materials, foods and beverages. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2020, 35, 426–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inobeme, A.; Natarajan, A.; Pradhan, S.; Adetunji, C.O.; Ajai, A.I.; Inobeme, J.; Tsado, M.J.; Jacob, J.O.; Pandey, S.S.; Singh, K.R. Chemical Sensor Technologies for Sustainable Development: Recent Advances, Classification, and Environmental Monitoring. Advanced Sensor Research 2024, 3, 2400066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Salwan, S.; Kumar, P.; Bansal, N.; Kumar, B. Electroanalysis Advances in Pharmaceutical Sciences: Applications and Challenges Ahead. Analytica 2025, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malode, S.J.; Ali Alshehri, M.; Shetti, N.P. Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Sensors for the Detection of Pharmaceutical Drugs. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G.; Palanisamy, B.; Chackaravarthy, G.; Chelliah, C.K.; Rajivgandhi, G.; Quero, F.; Natesan, M. Diagnosis of Physical Stimuli Response Enhances the Anti-Quorum Sensing Agents in Controlling Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Nanoscience and Nanotechnology for Smart Prevention, Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Fundamentals to Applications 2024, 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Ji, C.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Y. Advances and Future Trends in Nanozyme-Based SERS Sensors for Food Safety, Environmental and Biomedical Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, T.; Jamal, M.; Gulshan, F. Opto-structural properties and photocatalytic activities of CuO NPs synthesized by modified sol-gel and Co-precipitation methods: A comparative study. Results in Materials 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraddha, S.; Dhanashri, P.; Nishita, J.; Jayant, P.; Vidya, S.T.; Rabinder, H. Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles by Chemical Precipitation Method for the Determination of Antibacterial Efficacy against Streptococcus Sp. And Staphylococcus Sp. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2019, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chang, H.; Wang, Q. Pyrolysis temperature effect on compositions of basic nitrogen species in Huadian shale oil using positive-ion ESI FT-ICR MS and GC-NCD. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2021, 153, 104980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.; Ali, Z.; Qadir, A.; Farooq, M.U.; Shuaib, A.; Zahra, A.; Shahzady, T.; Hussain, H. Synthesis of CuO-NPS by simple wet chemical method using various dicarboxylic acid salts as precursors: Spectral characterization and in-vitro biological evaluation. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Ethiopia 2020, 34, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Haponiuk, J.T.; Thomas, S.; Gopi, S. Natural carbon-based quantum dots and their applications in drug delivery: A review. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 132, 110834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, C.; Niu, Q.; Cao, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Lu, W. Ni–Fe hybrid nanocubes: an efficient electrocatalyst for non-enzymatic glucose sensing with a wide detection range. New Journal of Chemistry 2019, 43, 11135–11140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Li, X.; Yates, M.Z. Nonenzymatic Glucose Sensor Using Bimetallic Catalysts. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, F.; Samaei, M.R.; Manoochehri, Z.; Jalili, M.; Yazdani, E. The effect of incubation temperature and growth media on index microbial fungi of indoor air in a hospital building in Shiraz, Iran. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 31, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.A.; Aparna, R.; Aswathy, B.; Nebu, J.; Aswathy, A.; George, S. Understanding the citric Acid–Urea Co–Directed microwave assisted synthesis and ferric ion modulation of fluorescent nitrogen doped carbon dots: a turn on assay for ascorbic acid. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvozdenko, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Blinov, A.; Golik, A.; Nagdalian, A.; Maglakelidze, D.; Statsenko, E.; Pirogov, M.; Blinova, A.; Sizonenko, M. Synthesis of CuO nanoparticles stabilized with gelatin for potential use in food packaging applications. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.H.; Ejaz, U.; Vithanage, M.; Bolan, N.; Siddique, K.H. Synthesis, characterization, and advanced sustainable applications of copper oxide nanoparticles: a review. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2024, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaya, T.; Bommy, B. Design and fabrication of rGO supported cobalt ferrite hybrid sensor for ultrasensitive detection of testosterone. Ionics 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M. CuO as efficient photo catalyst for photocatalytic decoloration of wastewater containing Azo dyes. Water Practice & Technology 2021, 16, 1078–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, P.A. Visible Light: Data communications and applications; IOP Publishing: 2020.

- Aaga, G.F.; Anshebo, S.T. Green synthesis of highly efficient and stable copper oxide nanoparticles using an aqueous seed extract of Moringa stenopetala for sunlight-assisted catalytic degradation of Congo red and alizarin red s. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejaswi, T.S.; Devi, P.S. Biogenesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles using Marine Bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa: In vitro Antimicrobial and Photocatalytic Activities. Journal of Pure & Applied Microbiology 2025, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, L.; Dwivedi, V.K.; Dara, H.K.; Chakradhary, V.K.; Ithineni, S.; Prabhudessai, A.G.; Nehar, S. Core/Shell-Like Magnetic Structure and Optical Properties in CuO Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Route. ACS Sustainable Resource Management 2024, 1, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, A.B.G.; Mostafa, A.M.; Alkallas, F.H.; Elsharkawy, W.; Al-Ahmadi, A.N.; Ahmed, H.A.; Nafee, S.S.; Pashameah, R.A.; Mwafy, E.A. Effect of CuO nanoparticles on the optical, structural, and electrical properties in the PMMA/PVDF nanocomposite. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, T.; Cargnello, M.; Gordon, T.R.; Zhang, S.; Yun, H.; Lee, J.D.; Woo, H.Y.; Oh, S.J.; Kagan, C.R.; Fornasiero, P. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from substoichiometric colloidal WO3–x nanowires. ACS Energy Letters 2018, 3, 1904–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyalo, S.; Etefa, H.F.; Dejene, F.B. “Enhancing structural and optical properties of CuO thin films through gallium doping: A pathway to enhanced photoluminescence and predict for solar cells applications”. Chemical Physics Impact 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-P.; Chan, Y.-B.; Aminuzzaman, M.; Shahinuzzaman, M.; Djearamane, S.; Thiagarajah, K.; Leong, S.-Y.; Wong, L.-S.; Tey, L.-H. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles from Durian (Durio zibethinus) Husk for Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, A.A.; Abdelfattah, N.A.; Salem, S.S.; Awad, M.F.; Fouda, A. Efficacy assessment of biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) on stored grain insects and their impacts on morphological and physiological traits of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plant. Biology 2021, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, E.; Vellaisamy, K.; Ganesan, V.; Narayanan, V.; Saleh, N.i.; Thambusamy, S. Dual applications of cobalt-oxide-grafted carbon quantum dot nanocomposite for two electrode asymmetric supercapacitors and photocatalytic behavior. ACS omega 2024, 9, 14101–14117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liao, F.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. The advanced multi-functional carbon dots in photoelectrochemistry based energy conversion. International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing 2022, 4, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markunas, B.; Yim, T.; Snyder, J. pH-Mediated Solution-Phase Proton Transfer Drives Enhanced Electrochemical Hydrogenation of Phenol in Alkaline Electrolyte. ACS Catal 2024, 14, 16936–16946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hareesha, N.; Manjunatha, J. Electro-oxidation of formoterol fumarate on the surface of novel poly (thiazole yellow-G) layered multi-walled carbon nanotube paste electrode. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, J.; Faisal, M.; Algethami, J.S.; Alsaiari, M.A.; Alsareii, S.A.; Harraz, F.A. Low overpotential amperometric sensor using Yb2O3. CuO@ rGO nanocomposite for sensitive detection of ascorbic acid in real samples. Biosensors 2023, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, E.; Yang, T.; Wang, H.; Hou, X. Ti 3 C 2 T x (MXene)/Pt nanoparticle electrode for the accurate detection of DA coexisting with AA and UA. Dalton Transactions 2022, 51, 4549–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Burmistrov, D.E.; Fomina, P.A.; Validov, S.Z.; Kozlov, V.A. Antibacterial Properties of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 11563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracino, E.; Cirillo, V.; Marrese, M.; Guarino, V.; Benfenati, V.; Zamboni, R.; Ambrosio, L. Structural and functional properties of astrocytes on PCL based electrospun fibres. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021, 118, 111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).