Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

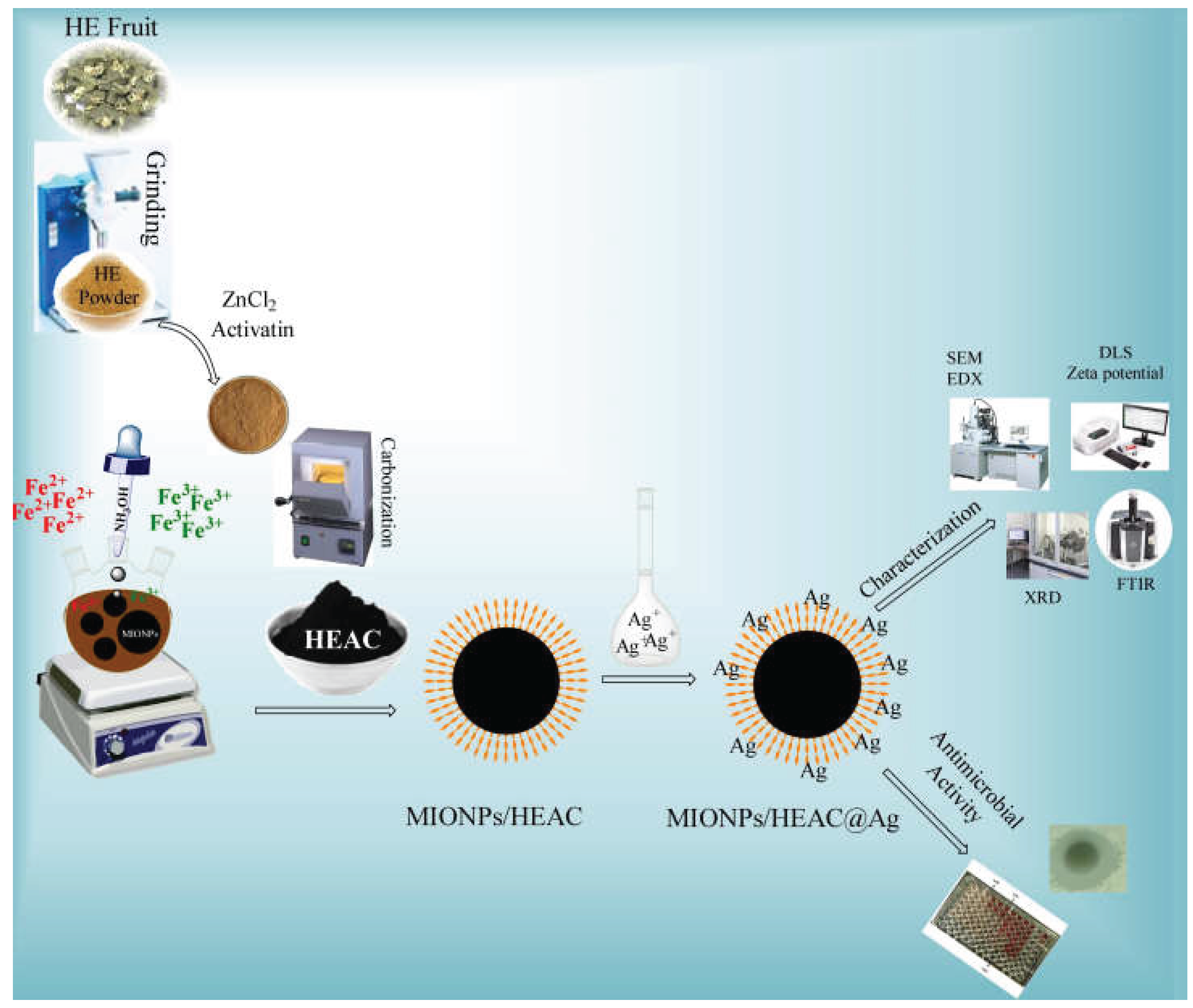

2.2. Synthesis of HEAC

2.3. Synthesis of MIONPs/HEAC

2.4. Synthesis of MIONPs/HEAC@Ag

2.5. Nanoparticles characterization

2.6. Analysis of antibacterial effect of MIONPs/HEAC and MIONPs/HEAC@Ag

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterization

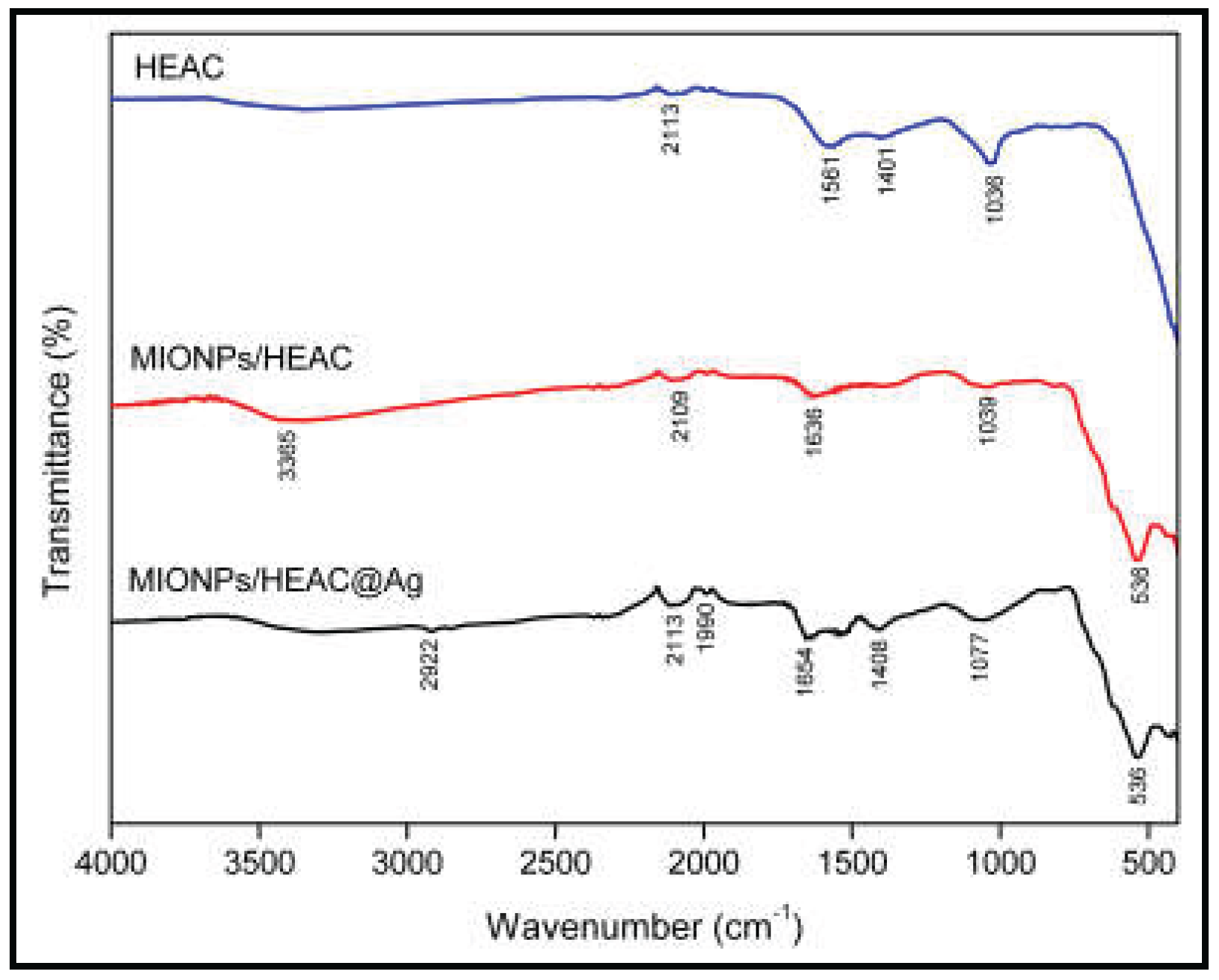

3.1.1. FTIR Analysis

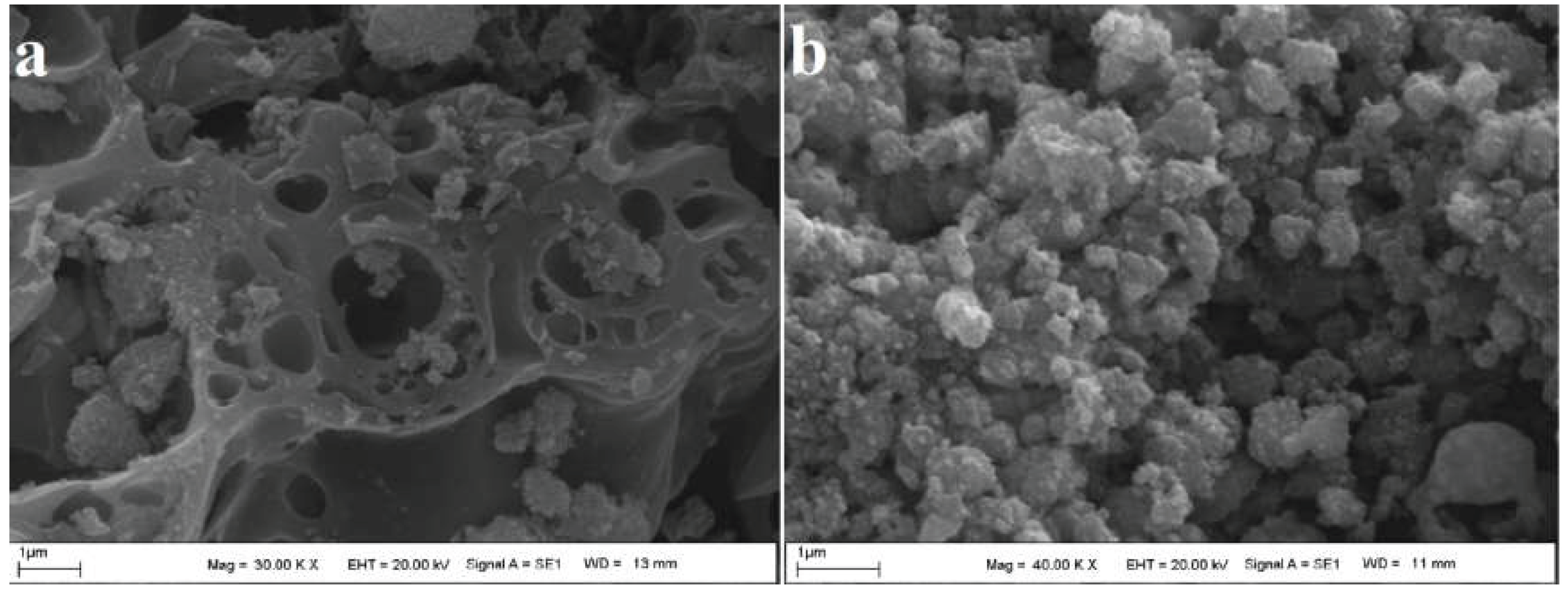

3.1.2. SEM Analysis

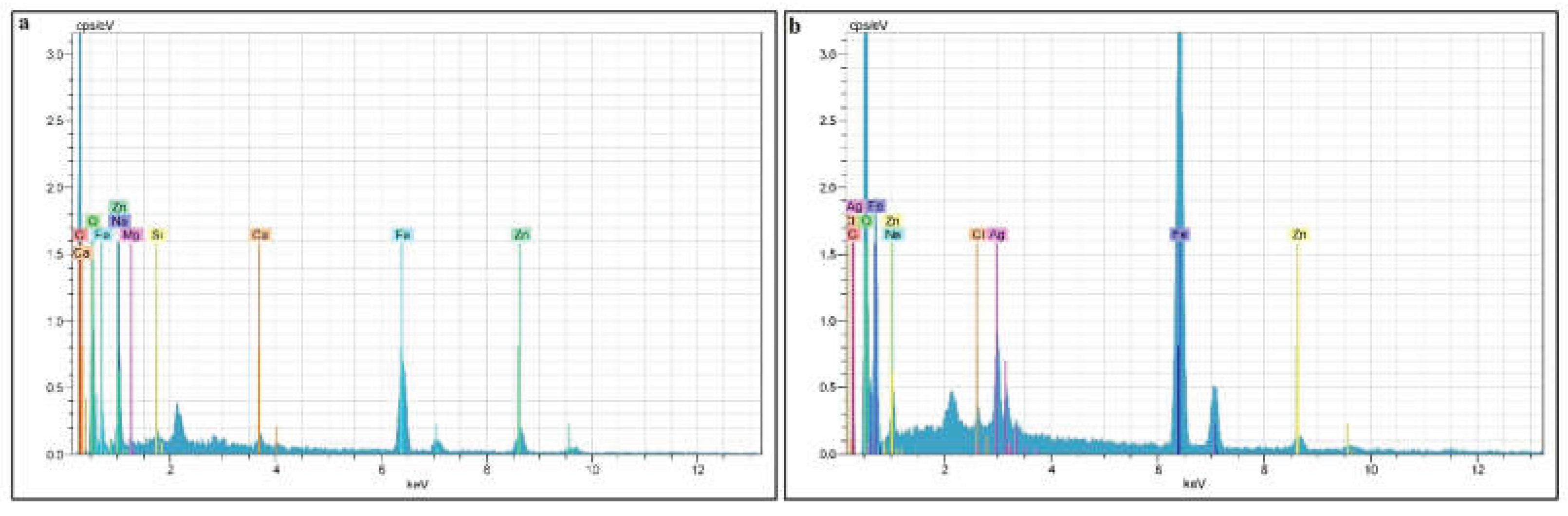

3.2.3. EDX Analysis

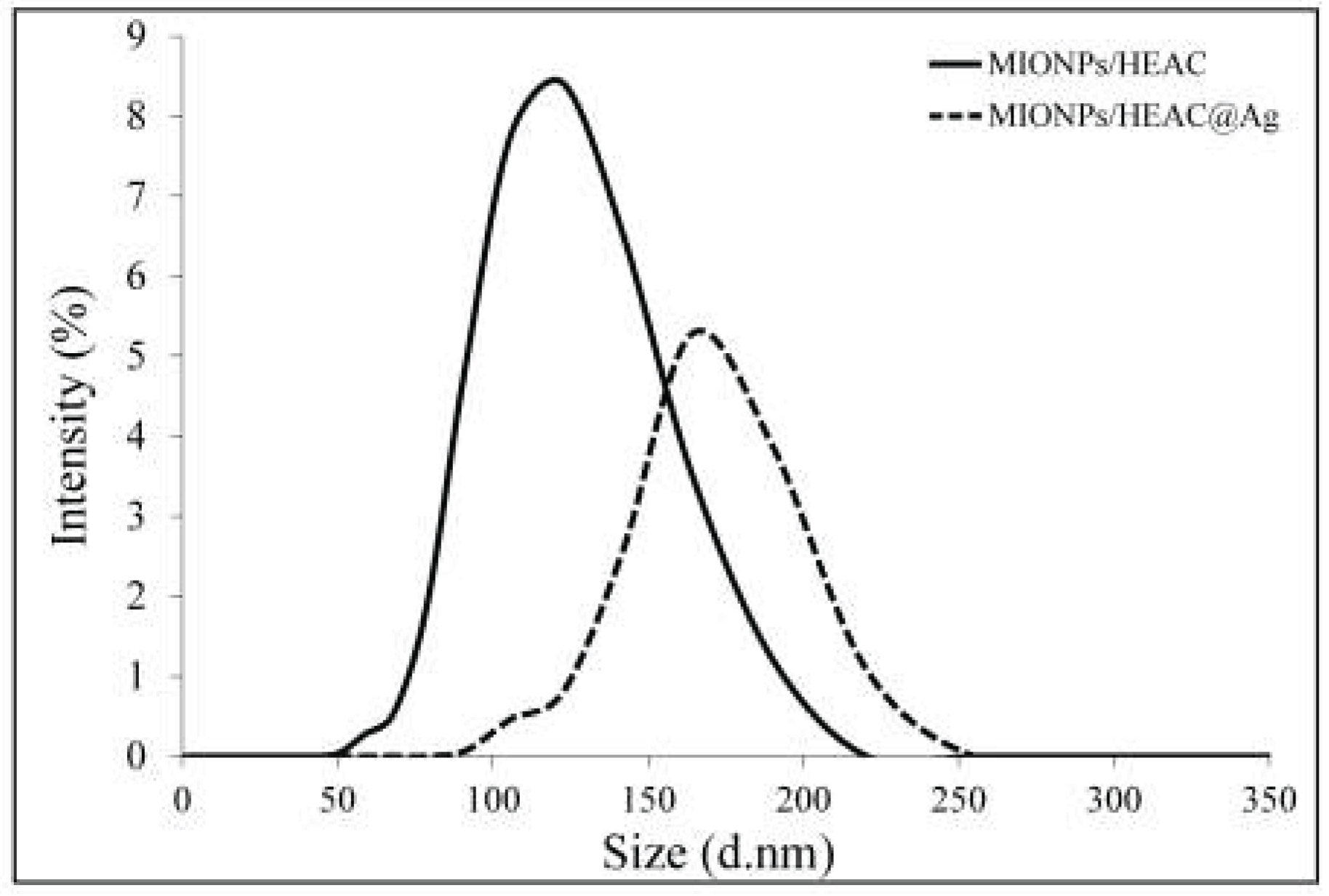

3.2.4. DLS Analysis

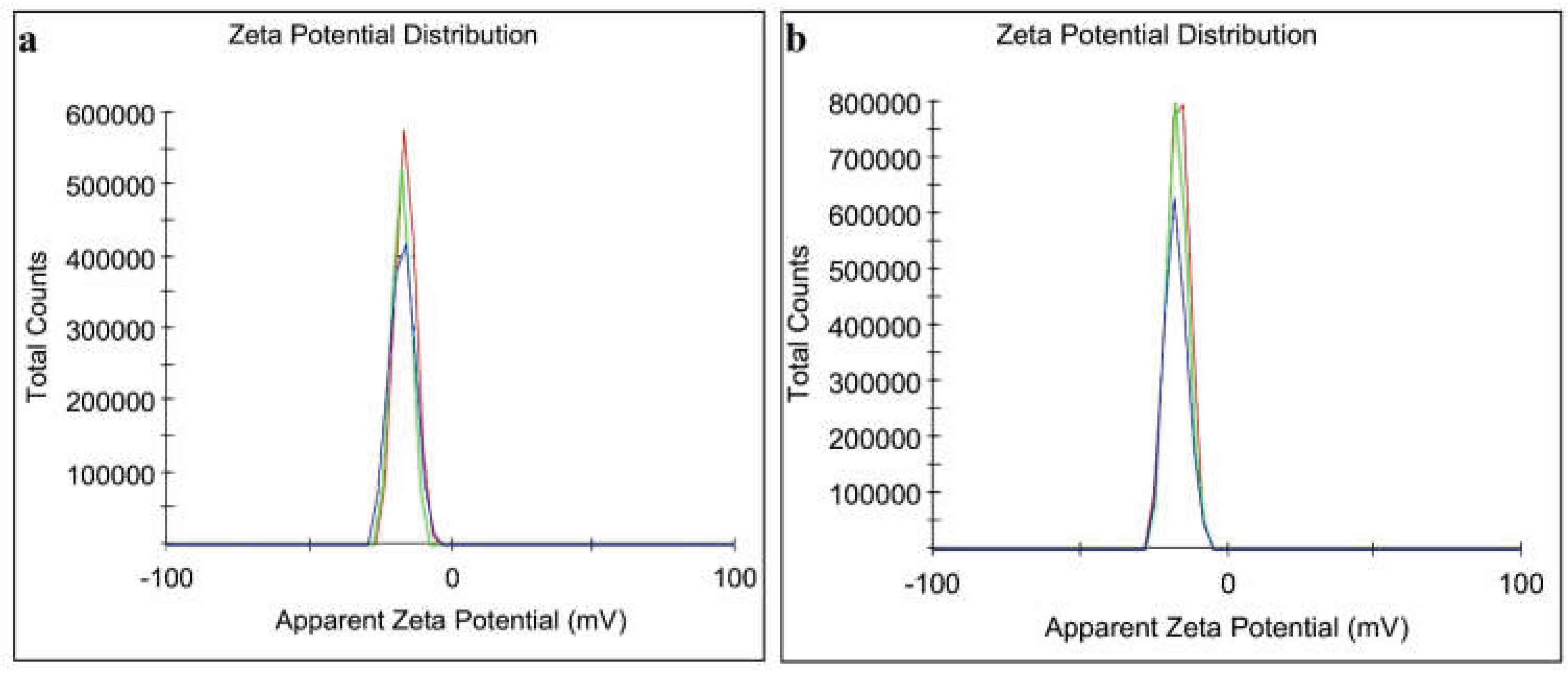

3.2.5. Zeta Potential Analysis

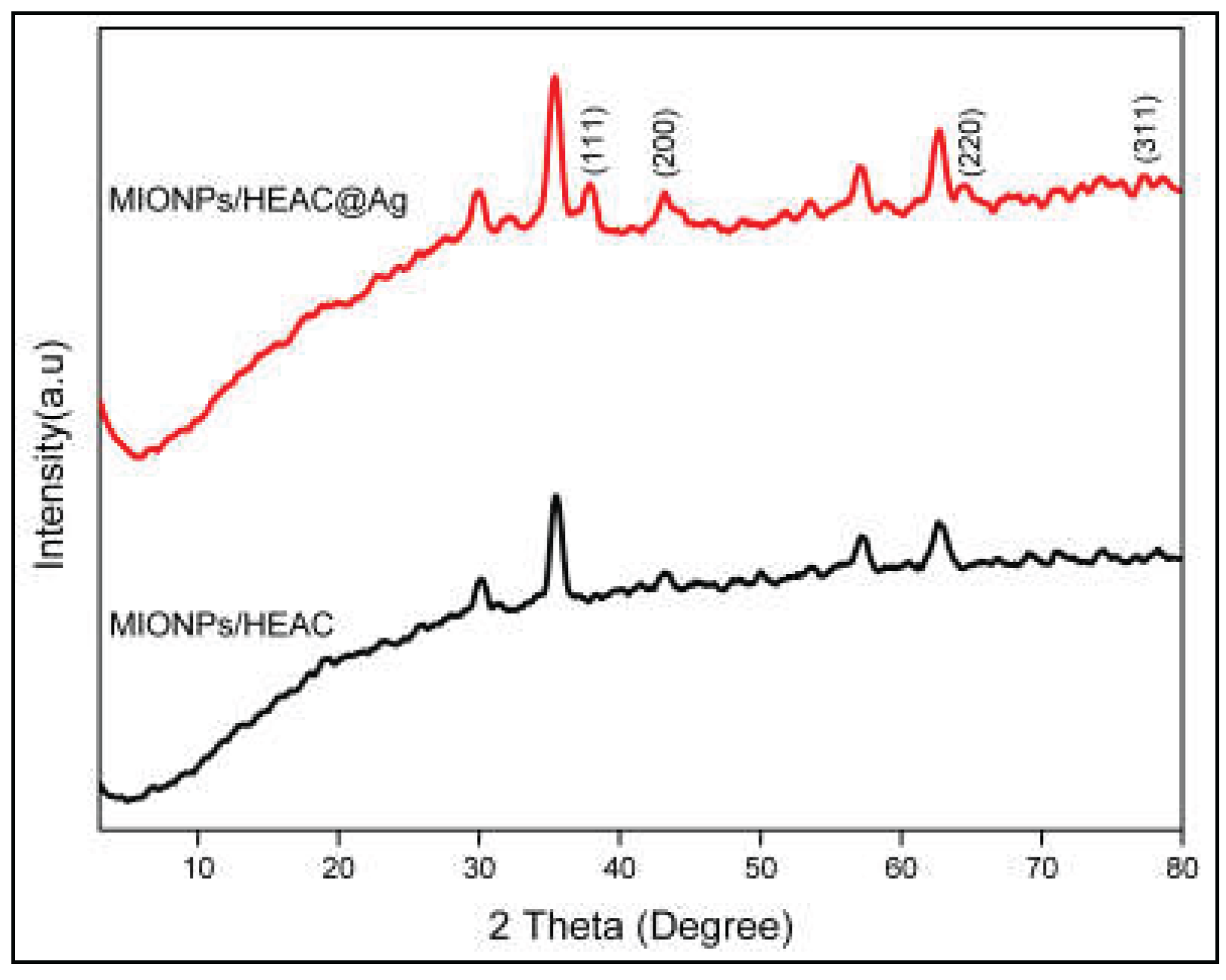

3.2.6. XRD Analysis

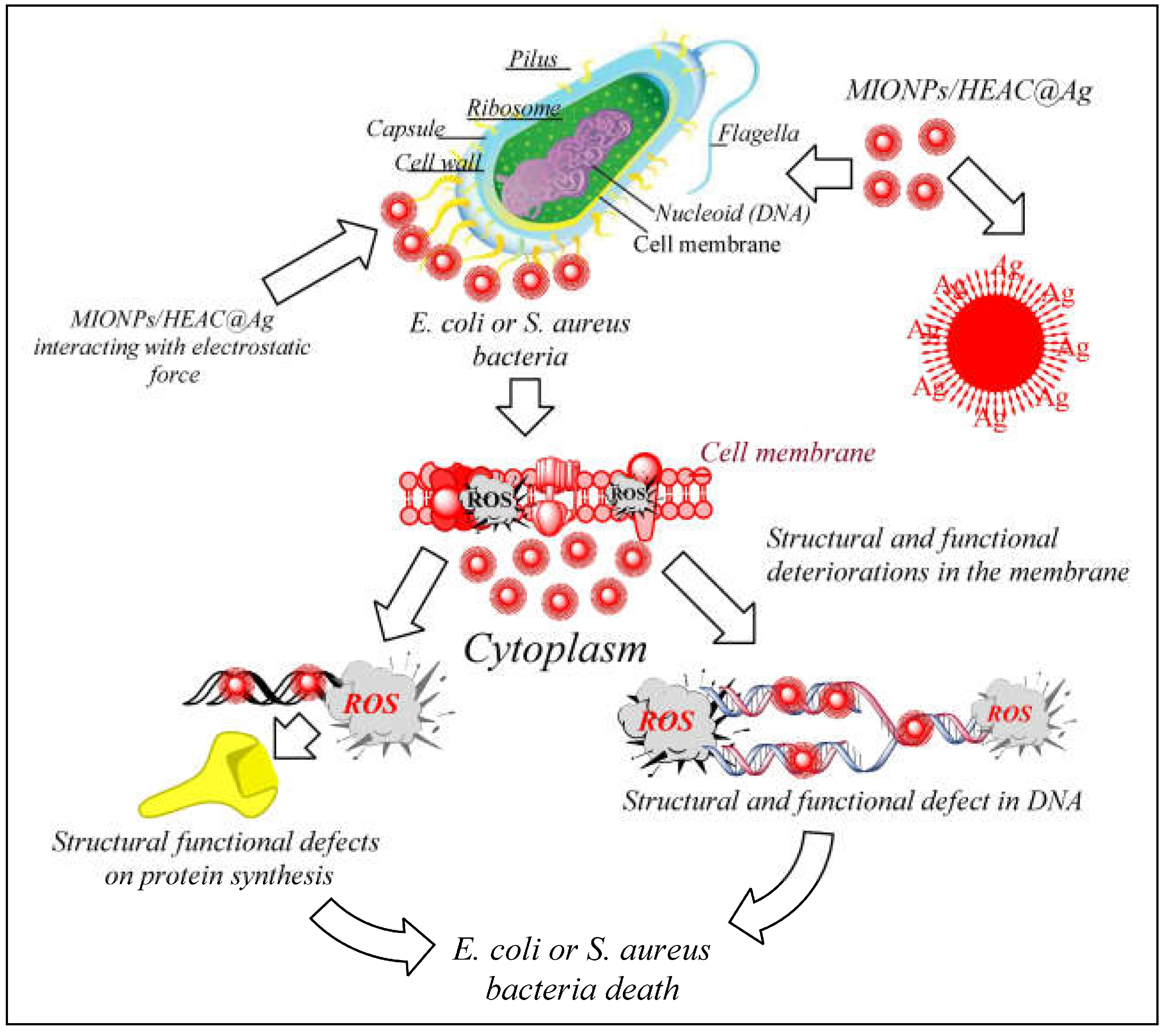

3.2. Antibacterial properties of MIONPs/HEAC and MIONPs/HEAC@Ag

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Das, A.; Sengupta, P.; Chatterjee, S.; Khanam, J.; Mondal, P.K.; Romero, E.L.; Ghosal, K. Development and Evaluation of Magnetite Loaded Alginate Beads Based Nanocomposite for Enhanced Targeted Analgesic Drug Delivery. Magnetochemistry, 2025, 11(2), 14. [CrossRef]

- Attar, S.R.; Sapkal, A.C.; Bagade, C.S.; Ghanwat, V. B.; Kamble, S.B. Biogenic CuO NPs for synthesis of coumarin derivatives in hydrotropic aqueous medium. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2023, 49(7), 2989-3004. [CrossRef]

- Adeeyo, A.O.; Alabi, M.A.; Oyetade, J.A.; Nkambule, T.T.; Mamba, B.B.; Oladipo, A.O.; Msagati, T.A. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Advances in Synthesis, Sensing, and Theragnostic Applications. Magnetochemistry, 2025, 11(2), 9.

- Fadeel, B. Nanomaterial characterization: Understanding nano-bio interactions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 633, 45-51. [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Fakhrullin, R. Nanoarchitectonics in Materials Science: Method for Everything in Materials Science. Materials 2023, 16(19), 6367. [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, S.M.; Arafa, I.M.; Abu-Zreg, S.M.; Al-Gharaibeh, M.M.; Hammouri, H.M.; Tarazi, Y.H.; Darmani, H. Synergistic effect of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with medicinal plant extracts against resistant bacterial strains. Magnetochemistry, 2024, 10(7), 49. [CrossRef]

- De, A.; Singh, N.B.; Guin, M.; Barthwal, S. Water purification by green synthesized nanomaterials. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2023, 24(1), 101-117. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Abdala, A. Silver nanoparticle-based nanocomposites for combating infectious pathogens: Recent advances and future prospects. Nanomater. 2021, 11(3), 581. [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.J.; Pratibha, S.; Rawat, J.M.; Venugopal, D.; Sahu, P.; Gowda, A.; Jaremko, M. Recent advances in green synthesis, characterization, and applications of bioactive metallic nanoparticles. Pharm. 2022, 15(4), 455. [CrossRef]

- Alburae, N.; Alshamrani, R.; Mohammed, A.E. Bioactive silver nanoparticles fabricated using Lasiurus scindicus and Panicum turgidum seed extracts: Anticancer and antibacterial efficiency. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 4162.

- Lobato-Peralta, D.R.; Duque-Brito,E.; Ayala-Cortés, A.; Arias,D.M.; Longoria,A.; Cuentas-Gallegos, A.K.; Okoye, P.U.: Advances in activated carbon modification, surface heteroatom configuration, reactor strategies, and regeneration methods for enhanced wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9(4), 105626. [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Fan, Y.; Li, D.; Jia, X.; Zhao, S. Preparation of Magnetic Nano-Catalyst Containing Schiff Base Unit and Its Application in the Chemical Fixation of CO2 into Cyclic Carbonates. Magnetochemistry, 2024, 10(5), 33. [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Y.; Öziç, C.; Ertaş, E.; Baran, A.; Rosic, G.; Selakovic, D.; Eftekhari, A. Activated carbon-coated iron oxide magnetic nanocomposite (IONPs@CtAC) loaded with morin hydrate for drug-delivery applications. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1477724. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.M.; Xu, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.Y.; Tu, Z.C. Structural properties, bioactivities, and applications of polysaccharides from Okra [Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench]: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68(48) 14091-14103.

- Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Alshammari, E.; Adnan, M.; Alcantara, J.C.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Eltoum, N.E.; Ashraf, S.A. Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) as a potential dietary medicine with nutraceutical importance for sustainable health applications. Molecules 2021, 26(3), 696. [CrossRef]

- Deen, G.R.; Hannan, F.A.; Henari, F.; Akhtar, S. Effects of different parts of the okra plant (Abelmoschus esculentus) on the phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles: evaluation of synthesis conditions, nonlinear optical and antibacterial properties. Nanomater. 2022, 12(23), 4174.

- Agregán, R.; Pateiro, M.; Bohrer, B.M.; Shariati, M.A.; Nawaz, A.; Gohari, G.; Lorenzo, J.M. Biological activity and development of functional foods fortified with okra (Abelmoschus esculentus). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63(23), 6018-6033. [CrossRef]

- Öziç, C.; Ertaş, E.; Baran, M.F.; Baran, A.; Ahmadian, E.; Eftekhari, A.; Yıldıztekin, M. Synthesis and characterization of activated carbon-supported magnetic nanocomposite (MNPs-OLAC) obtained from okra leaves as a nanocarrier for targeted delivery of morin hydrate. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1482130. [CrossRef]

- Baran, A.; Ertaş, E.; Baran, M.F.; Eftekhari, A.; Gunes, Z.; Keskin, C.; Khalilov, R. Green-Synthesized characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial applications of CtAC/MNPs-Ag nanocomposites. Pharm. 2024, 17(6), 772. [CrossRef]

- Deivayanai, V.C.; Karishma, S.; Thamarai, P.; Saravanan, A.; Yaashikaa, P.R. Artificial neural network modeling of dye adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics with magnetic nanoparticle-activated carbon from Allium cepa peels. Chem. Pap. 2025, 79, 1775-1796. [CrossRef]

- Chishti, A.N.; Guo, F.; Aftab, A.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Diao, G. Synthesis of silver doped Fe3O4/C nanoparticles and its catalytic activities for the degradation and reduction of methylene blue and 4-nitrophenol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 149070.

- Atunwa, B.T.; Dada, A.O.; Inyinbor, A.A.; Pal, U. Synthesis, physiochemical and spectroscopic characterization of Palm kernel shell activated carbon doped AgNPs (PKSAC@AgNPs) for adsorption of chloroquine pharma-ceutical waste. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 65, 3538-3546. [CrossRef]

- Moazzen, M.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Shariatifar, N.; Ahmadloo, M.; Eş, I.; Baghani,A.N.; Khaniki,G.J. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified with iron oxide and silver nanoparticles (MWCNT-Fe3O4/Ag) as a novel adsorbent for determining PAEs in carbonated soft drinks using magnetic SPE-GC/MS method. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12(4), 476-488. [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, R.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.: Adsorption of crystal violet dye using activated carbon of lemon wood and activated carbon/Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposite from aqueous solutions: a kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic study. Molecules 2021, 26(8), 2241.

- Lee, H.; Park, J.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, B.J.; An, K.H.; Kim, S.C.; Jung, S.C.: Preparation and characterization of silver-iron bimetallic nanoparticles on activated carbon using plasma in liquid process. Nanomat. 2021, 11(12), 3385. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, W.; Jie, F.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, K.; Liu, H.: The selective adsorption performance and mechanism of multiwall magnetic carbon nanotubes for heavy metals in wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16878. [CrossRef]

- Sepahvand, S.; Farhadi, S. Fullerene-modified magnetic silver phosphate (Ag3PO4/Fe3O4/C60) nanocomposites: Hydrothermal synthesis, charac- terization and study of photocatalytic, catalytic and antibacterial activities. RSC Adv. 2018, 8(18), 10124-10140.

- Arain, M.B.; Yilmaz, E.; Hoda, N.; Kazi, T.G.; Soylak, M. Magnetic solid-phase extraction of quercetin on magnetic-activated carbon cloth (MACC). J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2019, 16, 1365-1372. [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.P.; Singh, R.D.; Koli, P.B.; Patil, K.T.; Jagdale, B.S.; Tipare, A.R.; Kim, G.D. Antibacterial potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Madhuca Longifolia flower extract as a green resource. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 121, 184-189. [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Wang, C.; Hou, T.; Guan, P.; Qiao, Y.; Guo, L.; Wu, H. Lasting tracking and rapid discrimination of live gram-positive bacteria by peptidoglycan-targeting carbon quantum dots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13(1), 1277-1287. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, T.D.; Antunes, J.C.; Padrão, J.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Zille, A.; Amorim, M.T.P.; Felgueiras, H.P. Activity of specialized biomolecules against gram- positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9(6), 314. [CrossRef]

- Alav, I.; Kobylka, J.; Kuth, M.S.; Pos, K.M.; Picard, M.; Blair, J.M.; Bavro, V.N.: Structure, assembly, and function of tripartite efflux and type 1 secretion systems in gram-negative bacteria. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121(9), 5479-5596. [CrossRef]

- Tural, B.; Ertaş, E.; Batıbay, H.; Tural, S. The Impact of Pistacia khinjuk plant gender on silver nanoparticle synthesis: Are extracts of root obtained from female plants preferentially used? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 746, 151257. [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, O.O.; Ojemaye, M.O.; Okoh, A.I.: Antibacterial activity of metallic nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant pathogens isolated from environmental samples: nanoparticles/antibiotic combination therapy and cytotoxicity study. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5(10), 4814-4826. [CrossRef]

- Tural, B.; Ertaş, E.; Batıbay, H.; Tural, S. Comparative Study on Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis Using Male and Female Pistacia Khinjuk Leaf Extracts: Enhanced Efficacy of Female Leaf Extracts. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9(30), e202402117. [CrossRef]

- Castrillon, E.D.C.; Correa, S.; Ávila-Torres, Y.P. Impact of Magnetic Field on ROS Generation in Cu-g-C3N4 Against E. coli Disinfection Process. Magnetochemistry, 2025, 11(4), 28.

| Microorganism | Dilution Method (µg/mL) | Disc Method Zone of Inhibition (mm) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic | MIONPs/HEAC | MIONPs/HEAC@Ag | Control Disc | |||

| Deionized water | MIONPs/HEAC | MIONPs/HEAC@Ag | ||||

| E. coli | 2.0 | 96 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.50 |

| S. aureus | 1.0 | 48 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).