Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

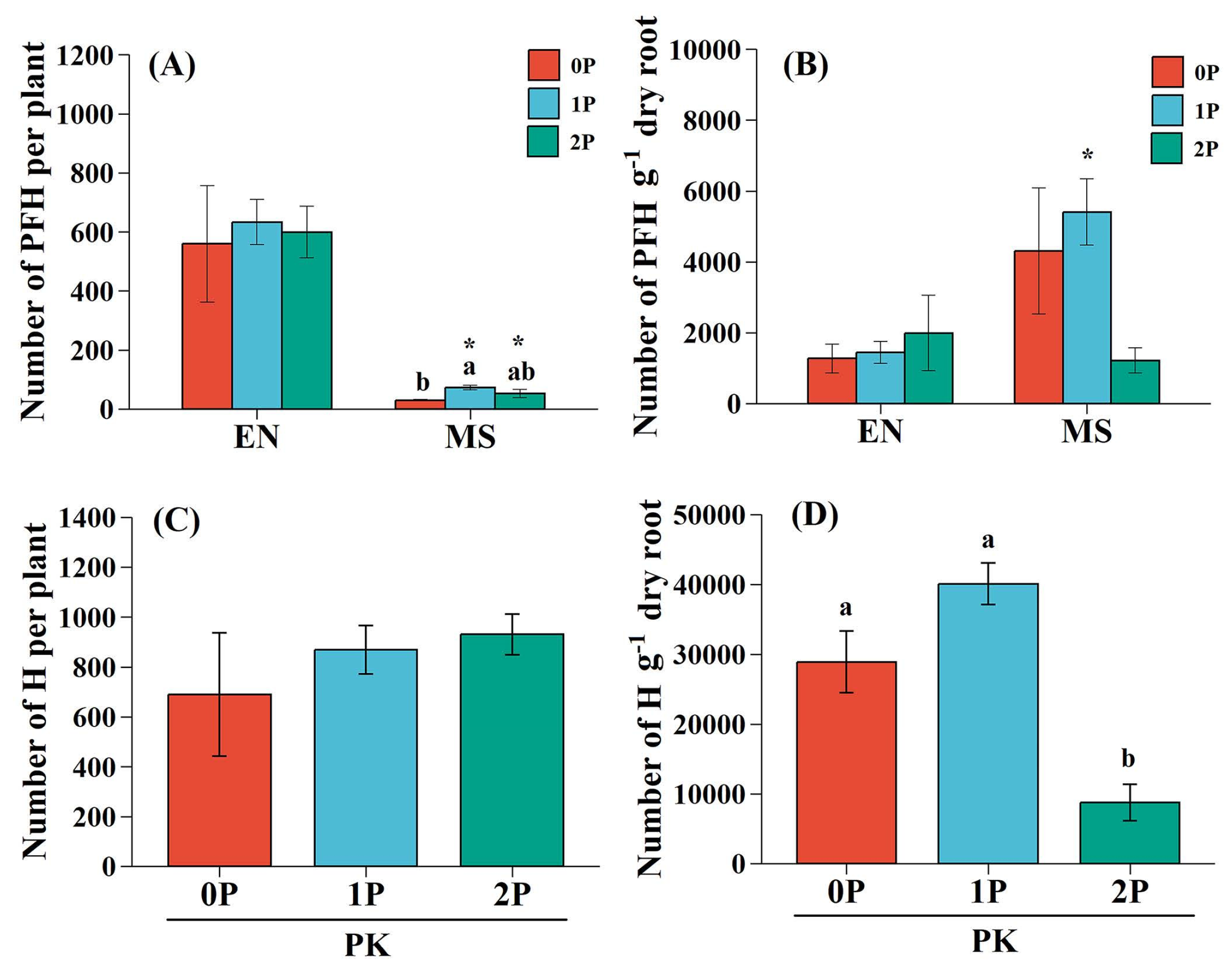

2.1. Haustorium Formation of the Hemiparasite

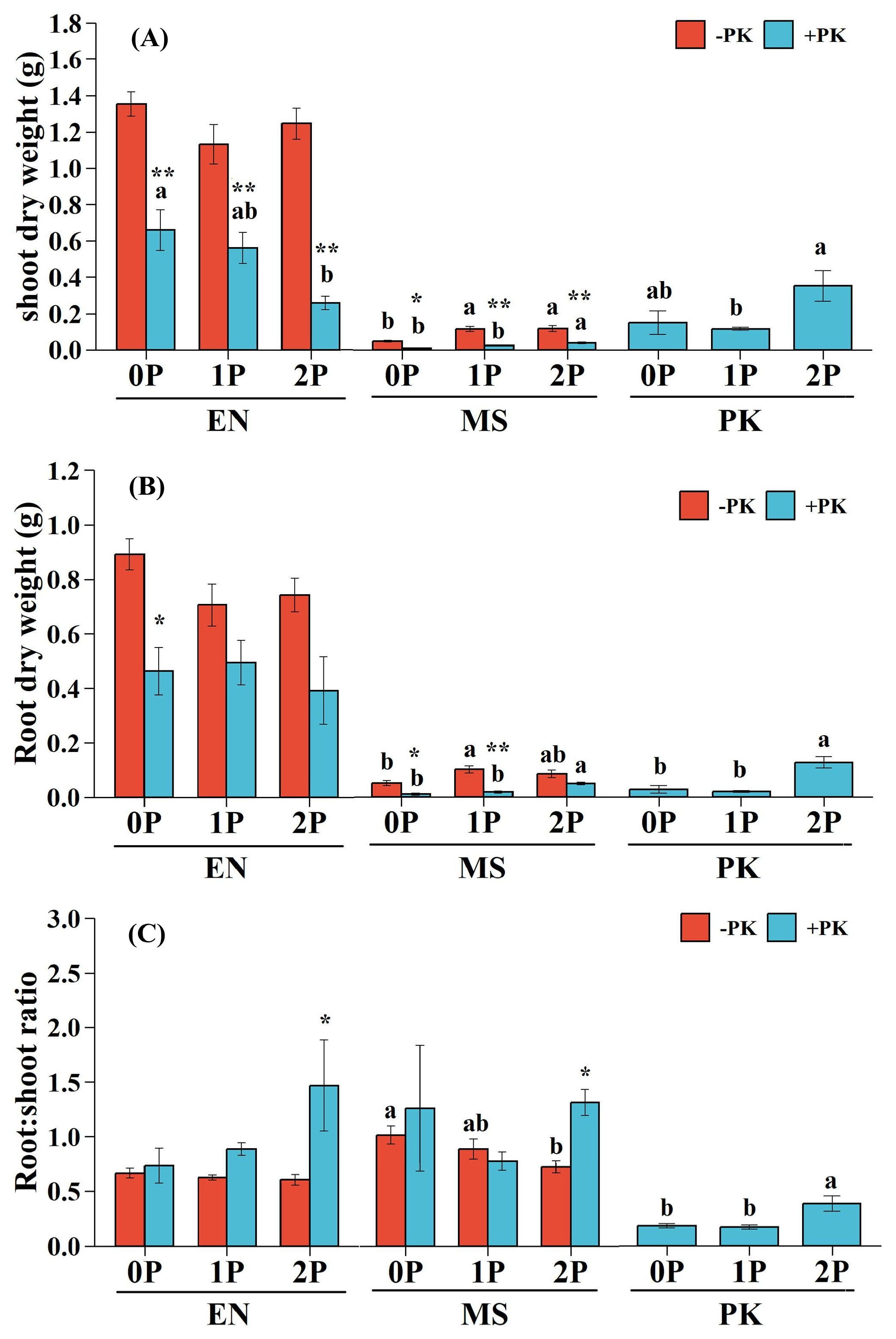

2.2. Growth Performance and Biomass Allocation of Hosts and the Hemiparasite

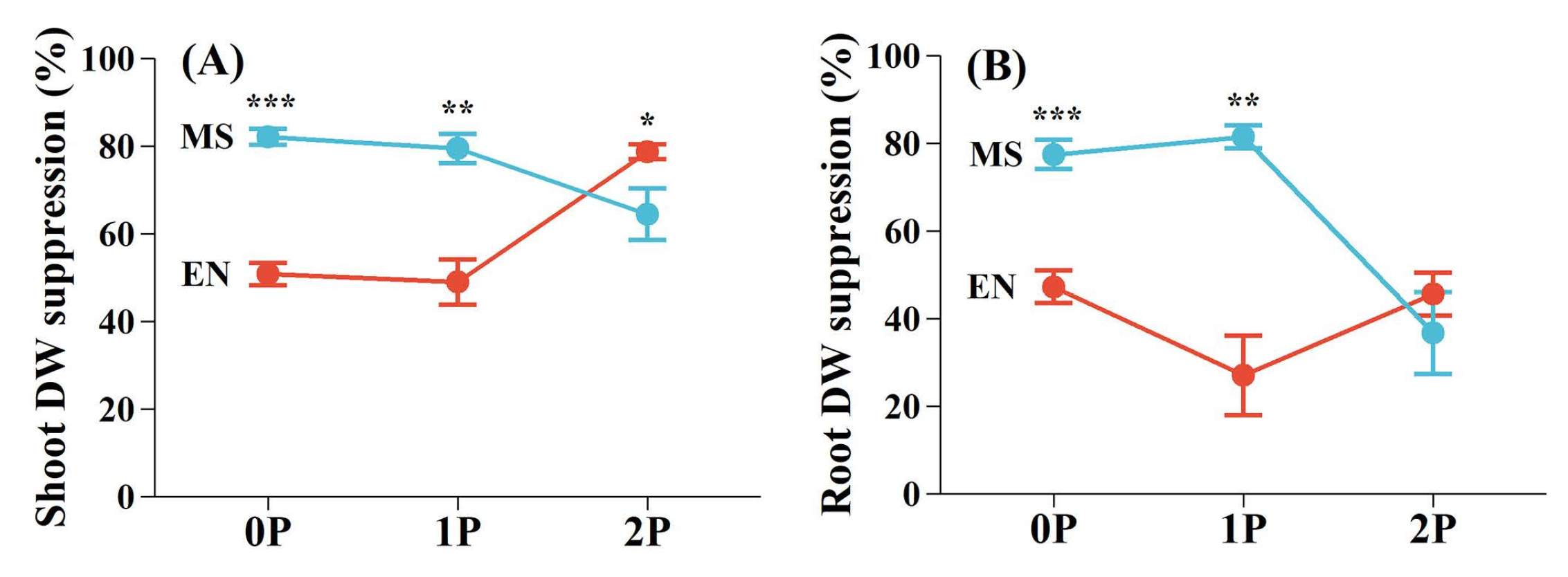

2.3. Host Suppression by P. kansuensis

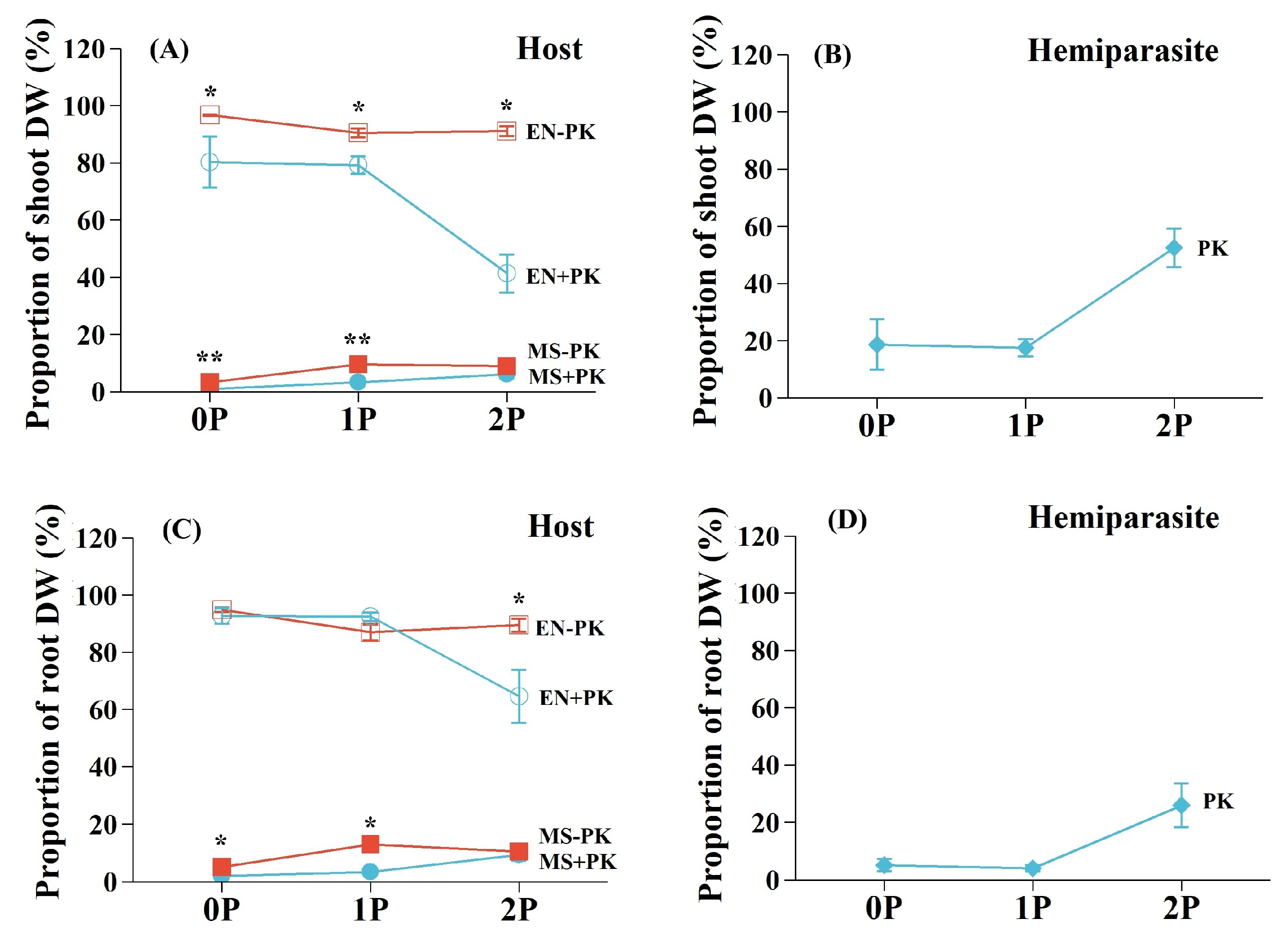

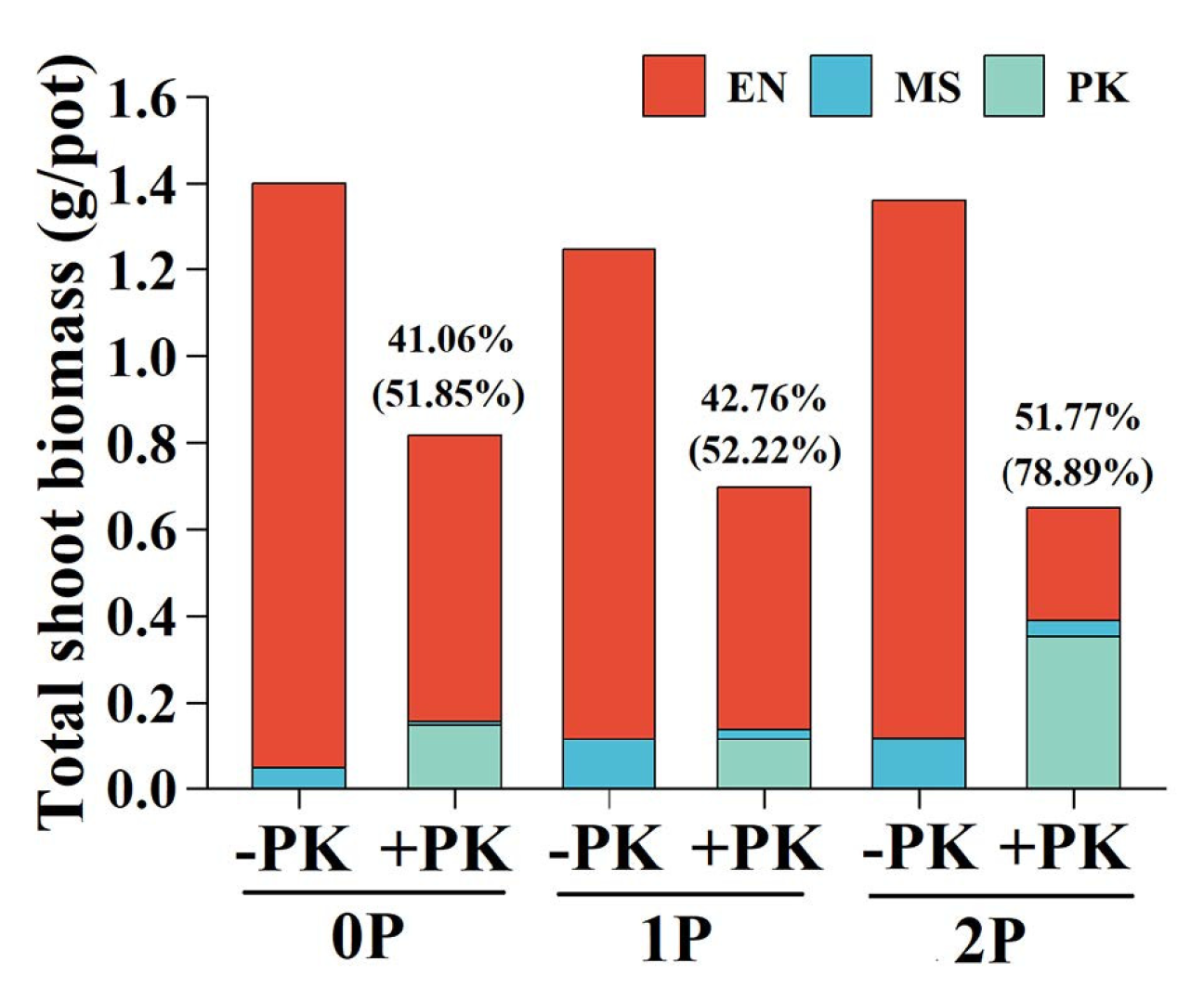

2.4. Biomass Proportions of Host and Hemiparasite per Pot

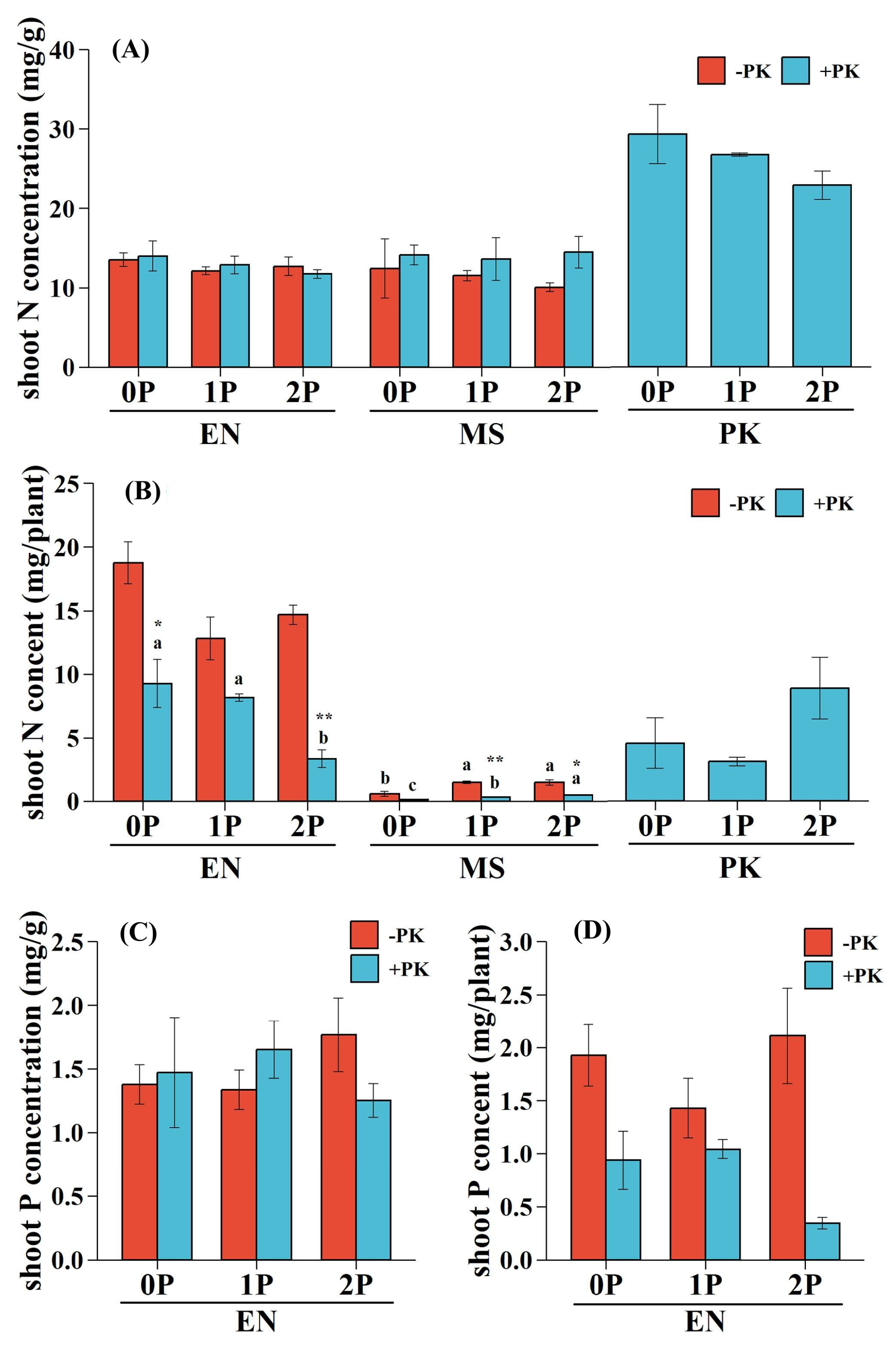

2.5. Shoot N and P Status of Hosts and Hemiparasite

3. Discussion

3.1. P Affected Host Selectivity of Root Hemiparasitic Plants Between Grass and Legume

3.2. Potential Mechanisms of P Affect Host Selectivity in Root Hemiparasitic Plants

3.3. Impact of Soil P Availability on Growth Performance of Hemiparasites

3.4. Implications for Management of Parasitic Plants

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Plant Materials

4.3. Planting and Growth Conditions

4.4. Harvest and Sampling

4.5. Measurement of Shoot N and P Concentrations

4.6. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Těšitel, J. Functional biology of parasitic plants: a review. Plant Ecol. Evol. 2016, 149, 5-20. [CrossRef]

- Westwood, J.H.; Yoder, J.I.; Timko, M.P.; dePamphilis, C.W. The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Irving, L.J.; Cameron, D.D. You are what you eat: interactions between root parasitic plants and their hosts. Adv. Bot. Res. 2009, 50, 87-138. [CrossRef]

- Matthies, D. Parasitic and competitive interactions between the hemiparasites Rhinanthus serotinus and Odontites rubra and their host Medicago sativa. J. Ecol. 1995, 83, 245-251.

- Press, M.C.; Phoenix, G.K. Impacts of parasitic plants on natural communities. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 737-751. [CrossRef]

- Fibich, P.; Leps, J.; Chytry, M.; Tesitel, J. Root hemiparasitic plants are associated with high diversity in temperate grasslands. J. Veg. Sci. 2017, 28, 184-191. [CrossRef]

- Těšitel, J.; Li, A.-R.; Knotkova, K.; McLellan, R.; Bandaranayake, P.C.G.; Watson, D.M. The bright side of parasitic plants: what are they good for? Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1309-1324. [CrossRef]

- Sandner, T.M.; Schoppan, L.; Matthies, D. Seedlings of a hemiparasite recognize legumes, but do not distinguish good from poor host species. Folia Geobot. 2022, 57, 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Matthies, D. Interactions between the root hemiparasite Melampyrum arvense and mixtures of host plants: Heterotrophic benefit and parasite-mediated competition. Oikos 1996, 75, 118-124. [CrossRef]

- Cechin, I.; Press, M.C. Nitrogen relations of the sorghum-Striga hermonthica host-parasite association: germination, attachment and early growth. New Phytol. 1993, 124, 681-687. [CrossRef]

- Rowntree, J.K.; Craig, H. The contrasting roles of host species diversity and parasite population genetic diversity in the infection dynamics of a keystone parasitic plant. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 23-33. [CrossRef]

- Westbury, D.B.; Dunnett, N.P. The promotion of grassland forb abundance: A chemical or biological solution? Basic Appl. Ecol. 2008, 9, 653-662. [CrossRef]

- Ameloot, E.; Verheyen, K.; Hermy, M. Meta-analysis of standing crop reduction by Rhinanthus spp. and its effect on vegetation structure. Folia Geobot. 2005, 40, 289-310. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.P.; Phoenix, G.K.; Childs, D.Z.; Press, M.C.; Smith, S.W.; Pilkington, M.G.; Cameron, D.D. Parasitic plant litter input: a novel indirect mechanism influencing plant community structure. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 222-231. [CrossRef]

- Ameloot, E.; Verlinden, G.; Boeckx, P.; Verheyen, K.; Hermy, M. Impact of hemiparasitic Rhinanthus angustifolius and R.minor on nitrogen availability in grasslands. Plant Soil 2008, 311, 255-268. [CrossRef]

- Matthies, D. Interactions between a root hemiparasite and 27 different hosts: growth, biomass allocation and plant architecture. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017, 24, 118-137. [CrossRef]

- Chaudron, C.; Mazalova, M.; Kuras, T.; Malenovsky, I.; Mladek, J. Introducing ecosystem engineers for grassland biodiversity conservation: A review of the effects of hemiparasitic Rhinanthus species on plant and animal communities at multiple trophic levels. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2021, 52. [CrossRef]

- Irving, L.J.; Kim, D.; Schwier, N.; Vaughan, J.K.E.; Ong, G.; Hama, T. Host nutrient supply affects the interaction between the hemiparasite Phtheirospermum japonicum and its host Medicago sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 162, 125-132. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jeschke, W.D.; Hartung, W.; Cameron, D.D. Interactions between Rhinanthus minor and its hosts: a review of water, mineral nutrient and hormone flows and exchanges in the hemiparasitic association. Folia Geobot. 2010, 45, 369-385. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.R.; Li, Y.J.; Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A.; Guan, K.Y. Nutrient requirements differ in two Pedicularis species in the absence of a host plant: implication for driving forces in the evolution of host preference of root hemiparasitic plants. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 1099-1106. [CrossRef]

- Těšitel, J.; Těšitelová, T.; Fisher, J.P.; Lepš, J.; Cameron, D.D. Integrating ecology and physiology of root-hemiparasitic interaction: interactive effects of abiotic resources shape the interplay between parasitism and autotrophy. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 350-360. [CrossRef]

- Cirocco, R.M.; Facelli, E.; Delean, S.; Facelli, J.M. Does phosphorus influence performance of a native hemiparasite and its impact on a native legume? Physiol. Plantarum 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cirocco, R.M.; Watling, J.R.; Facelli, J.M. The combined effects of water and nitrogen on the relationship between a native hemiparasite and its invasive host. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1728-1739. [CrossRef]

- Korell, L.; Sandner, T.M.; Matthies, D.; Ludewig, K. Effects of drought and N level on the interactions of the root hemiparasite Rhinanthus alectorolophus with a combination of three host species. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 84-92. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jeschke, W.D.; Hartung, W. Solute flows from Hordeum vulgare to the hemiparasite Rhinanthus minor and the influence of infection on host and parasite nutrient relations. Funct. Plant Biol. 2004, 31, 633-643. [CrossRef]

- Seel, W.E.; Parsons, A.N.; Press, M.C. Do inorganic solutes limit growth of the facultative hemiparasite Rhinanthus minor L in the absence of a host. New Phytol. 1993, 124, 283-289. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bi, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Struik, P.C.; Jing, J. Positive legacy effects of grass-legume mixture leys on phosphorus uptake and yield of maize weaken over the growing season. Field Crop Res. 2024, 314. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.G.; Tao, H.Y.; Li, W.B.; Zhou, R.; Gui, Y.W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, W.; Wang, B.Z.; Mei, F.J.; et al. Phosphorus availability mediates plant-plant interaction and field productivity in maize-grass pea intercropping system: field experiment and its global validation. Agric. Syst. 2023, 205. [CrossRef]

- Tawaraya, K.; Horie, R.; Shinano, T.; Wagatsuma, T.; Saito, K.; Oikawa, A. Metabolite profiling of soybean root exudates under phosphorus deficiency. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 60, 679-694. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Lambers, H.; Vance, C.P.; Shen, J.; Cheng, L. Flavonoids are involved in phosphorus-deficiency-induced cluster-root formation in white lupin. Ann. Bot. 2022, 129, 101-112. [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, K.; Yoneyama, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Sekimoto, H. Phosphorus deficiency in red clover promotes exudation of orobanchol, the signal for mycorrhizal symbionts and germination stimulant for root parasites. Planta 2007, 225, 1031-1038. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Cui, S.; White, A.R.F.; Nelson, D.C.; Yoshida, S.; Shirasu, K. Strigolactones are chemoattractants for host tropism in Orobanchaceae parasitic plants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.L.; Kuss, P.; Li, W.J.; Yang, M.Q.; Guan, K.Y.; Li, A.R. Identity and distribution of weedy Pedicularis kansuensis Maxim. (Orobanchaceae) in Tianshan Mountains of Xinjiang: morphological, anatomical and molecular evidence. J. Arid Land 2016, 8, 453-461. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.J.; Sui, X.L.; Kuss, P.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, A.R.; Guan, K.Y. Long-Distance Dispersal after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) led to the disjunctive distribution of Pedicularis kansuensis (Orobanchaceae) between the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and Tianshan Region. Plos One 2016, 11, e0165700. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Taxipulati, T.; Gong, Y.M.; Sui, X.L.; Wang, X.Z.; Parent, S.E.; Hu, Y.K.; Guan, K.Y.; Li, A.R. N-P fertilization inhibits growth of root hemiparasite Pedicularis kansuensis in natural grassland. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2088. [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.S.; Suetsugu, K.; Wang, H.S.; Yao, X.; Liu, L.; Ou, J.; Li, C.J. Effects of the hemiparasitic plant Pedicularis kansuensis on plant community structure in a degraded grassland. Ecol. Res. 2015, 30, 507-515. [CrossRef]

- Tesitel, J.; Mladek, J.; Hornik, J.; Tesitelova, T.; Adamec, V.; Tichy, L. Suppressing competitive dominants and community restoration with native parasitic plants using the hemiparasitic Rhinanthus alectorolophus and the dominant grass Calamagrostis epigejos. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1487-1495. [CrossRef]

- Těšitel, J.; Mladek, J.; Fajmon, K.; Blazek, P.; Mudrak, O. Reversing expansion of Calamagrostis epigejos in a grassland biodiversity hotspot: hemiparasitic Rhinanthus major does a better job than increased mowing intensity. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2018, 21, 104-112. [CrossRef]

- Sandner, T.M.; Matthies, D. Multiple choice: hemiparasite performance in multi-species mixtures. Oikos 2018, 127, 1291-1303. [CrossRef]

- Goyet, V.; Wada, S.; Cui, S.; Wakatake, T.; Shirasu, K.; Montiel, G.; Simier, P.; Yoshida, S. Haustorium inducing factors for parasitic Orobanchaceae. Front. plant sci. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, H.K.; Wang, J.P.; Chen, Z.J.; Luo, L.J.; Liu, G.D.; Liu, P.D. Metabolic alterations provide insights into Stylosanthes roots responding to phosphorus deficiency. Bmc. Plant Biol. 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Malusà, E.; Russo, M.; Mozzetti, C.; Belligno, A. Modification of secondary metabolism and flavonoid biosynthesis under phosphate deficiency in bean roots. J. Plant Nutr. 2006, 29, 245-258. [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.H.; Zhang, M.K.; Liang, C.Y.; Cai, L.Y.; Tian, J. Integration of metabolome and transcriptome analyses highlights soybean roots responding to phosphorus deficiency by modulating phosphorylated metabolite processes. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2019, 139, 697-706. [CrossRef]

- Dakora, F.D.; Phillips, D.A. Root exudates as mediators of mineral acquisition in low-nutrient environments. Plant Soil 2002, 245, 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Borowicz, V.A.; Armstrong, J.E. Resource limitation and the role of a hemiparasite on a restored prairie. Oecologia 2012, 169, 783-792. [CrossRef]

- Hautier, Y.; Hector, A.; Vojtech, E.; Purves, D.; Turnbull, L.A. Modelling the growth of parasitic plants. J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 857-866. [CrossRef]

- Těšitel, J.; Fibich, P.; de Bello, F.; Chytry, M.; Leps, J. Habitats and ecological niches of root-hemiparasitic plants: an assessment based on a large database of vegetation plots. Preslia 2015, 87, 87-108.

- Fibich, P.; Leps, J.; Berec, L. Modelling the population dynamics of root hemiparasitic plants along a productivity gradient. Folia Geobot. 2010, 45, 425-442. [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.L.; Zhang, T.; Tian, Y.T.; Xue, R.J.; Li, A.R. A neglected alliance in battles against parasitic plants: arbuscular mycorrhizal and rhizobial symbioses alleviate damage to a legume host by root hemiparasitic Pedicularis species. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 470-481. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, E.J. Sand and water culture methods used in the study of plant nutrition; Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux: Farnham Royal, UK, 1966; pp. 547.

- Li, A.R.; Guan, K.Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi may serve as another nutrient strategy for some hemiparasitic species of Pedicularis (Orobanchaceae). Mycorrhiza 2008, 18, 429-436. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.R.; Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A.; Guan, K.Y. Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi suppresses initiation of haustoria in the root hemiparasite Pedicularis tricolor. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 1075-1080. [CrossRef]

- Wickham H., François R., Henry L., Müller K., Vaughan D. dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. R package version 1.1.4 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr. (accessed on 31 Oct. 2024).

- Lenth R. emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.10.6 2024. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans. (accessed on 12 Dec. 2024).

- Bates D., Maechler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67: 1-48. [CrossRef]

- Fox J., Weisberg S. An R companion to applied regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA. 2019.

- Kassambara A. gpubr: ‘ggplot2’ based publication ready plots. R package version 0.6.0 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr.(accessed on 31 Oct. 2024).

- Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag, USA, 2016.

| Shoot dry weight | Root dry weight | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN | MS† | Total | EN | MS† | Total | ||||||||

| df | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | |

| P | 2,19 | 6.81** | 0.42 | 32.02*** | 0.77 | 3.20 | 0.25 | 1.91 | 0.17 | 12.49*** | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.09 |

| Pa | 1, 19 | 121.47*** | 0.86 | 176.11*** | 0.90 | 83.74*** | 0.82 | 24.06*** | 0.56 | 65.27*** | 0.90 | 25.40*** | 0.57 |

| P*Pa | 2,19 | 3.32 | 0.26 | 3.16 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.08 | 6.80** | 0.25 | 0.81 | 0.08 |

| N concentration | P concentration | N content | P content | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN | MS | EN | MS | EN | MS† | EN | MS | ||||||||

| df | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | F | ηP2 | |||

| P | 2, 12 | 1.091 | 0.15 | 0.117 | 0.02 | 0.063 | 0.01 | -- | 7.717** | 0.56 | 30.153*** | 0.83 | 0.358 | 0.06 | -- |

| Pa | 1, 12 | 0.010 | 0.00 | 2.484 | 0.17 | 0.028 | 0.00 | -- | 63.166** | 0.84 | 101.813*** | 0.89 | 21.840** | 0.65 | -- |

| P*Pa | 2, 12 | 0.334 | 0.05 | 0.239 | 0.04 | 1.440 | 0.19 | -- | 3.479 | 0.37 | 1.057 | 0.15 | 3.169 | 0.35 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).