1. Introduction

Alien plant invasions are a significant ecological issue, causing substantial alterations in species composition, community structure, and ecosystem function [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Understanding the drivers of alien plant invasions is crucial not only for theoretical advancements but also for providing scientific basis for predicting distribution of invasive species and developing their effective control strategies [

6]. Anthropogenic atmospheric nitrogen (N) deposition is a serious global environmental issue [

7,

8], and has been demonstrated to facilitate plant invasions and exacerbate ecological damage [

9,

10,

11,

12]. For example, Lei et al. (2012) found that the noxious invasive plant

Eupatorium adenophorum responded more strongly to N addition than its native congeners [

10]. However, most related studies have focused on the effects of soil N levels, and the effects of N forms has received comparatively less attention [

13,

14]. Investigating how varying N forms affect alien plant invasions will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying the invasions.

The ratio of nitrate (NO

3-) to ammonium (NH

4+) N in soil varies with environments, and is always influenced by global change. NH

4+ is the dominant N form in infertile, oxygen-limited, or acidic soils [

15,

16], while NO

3- in fertile, well-aerated, or alkaline soils [

17,

18]. The N forms in atmospheric deposition also fluctuates, and the proportion of nitrate increases gradually [

19,

20]. Human disturbances, particularly through agricultural practices, can enhance the activity of soil nitrifying bacteria, promoting nitrification and thus increasing soil NO

3- content [

15,

16,

18,

21,

22]. For instance, Guo & Jia (2014) found that soil nitrification rates are higher in frequently disturbed agro-ecosystems than in forest ecosystems, which are positively correlated with soil pH and NO

3- levels [

23]. Furthermore, excessive use of N fertilizer can also cause NO

3- (more mobile than NH

4+) to enter non-agro ecosystems via runoff, elevating soil NO

3- availability and NO

3- / NH

4+ ratio [

24]. Disturbed habitats are more susceptible to plant invasions than undisturbed or minimally disturbed habitats [

25], which is often attributed to disturbance-driven increase in soil nutrient availability [

26]. Besides the increased soil N availability, the disturbance-altered soil N forms may also contribute to alien plant invasions.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that plant species differ in their capacity to utilize soil NO

3- and NH

4+ [

13,

27,

28], and often exhibit preference for a specific N form [

14,

16,

29]. For instance, several invasive plants, including

Bidens pilosa,

Flaveria bidentis,

Ipomoea cairica,

Mikania micrantha,

Wedelia trilobata, and

Xanthium strumarium all have been shown to prefer NO

3- [

14,

20,

30]. However,

W. trilobata is also found to prefer NH

4+ under certain environmental conditions [

15]. This discrepancy in N form preference may possibly be associated with the differences in experimental conditions such as soil N availability.

Solidago canadensis also shows a context-dependent N form preference: preference for NH

4+ in farmlands and abandoned fields, but preference for NO

3- in roadsides. These results indicate that plant N form preference is influenced by numerous factors, including soil inorganic N pool and NO

3- / NH

4+ ratio [

32]. In addition, interspecific competition can also alter soil nutrient dynamics, and thus affect plant N form preference [

33]. These findings suggest that global change-driven alteriations in soil N forms and availability may affect future invasion potential and geographic spread of invasive alien plants. Consequently, studying the differential responses of invasive and native plants to different N forms is crucial not only for revealing invasion mechanisms but also for developing effective management strategies for invasive plants in the context of global change.

In this study, three noxious invasive alien plants

Ambrosia trifida,

Bidens frondosa, and

Xanthium strumarium, which are common in disturbed habitats in China [

25], were compared with their phylogenetically related native plants

Siegesbeckia glabrescens,

B. biternata, and

X. sibiricum, respectively in a common garden. First, we determined the differences in responses of growth, biomass allocation, and photosynthesis to NH

4+ versus NO

3- addition between each invasive and its related native species grown in both mixed and monoculture. Second, we assessed interspecific difference in N form preference using the

15N isotope labeling technique. We hypothesize that (1) N addition increases growth more greatly for all invaders compared with their respective related natives; (2) the extent to which the invaders prefer NO

3- over NH

4+ are greater than that for their related natives, and addition of nitrate relative to ammonium N more greatly promotes growth of the invaders, increasing their growth advantages and thus facilitating their invasions; (3) the above-mentioned phenomena are more pronounced in mixed culture than in monoculture. Testing these hypotheses may provide valuable insights for understanding the evolution of invasiveness of alien plants and the underlying mechanisms in the context of global change such as atmospheric N deposition and agricultural non-point source pollution.

2. Results

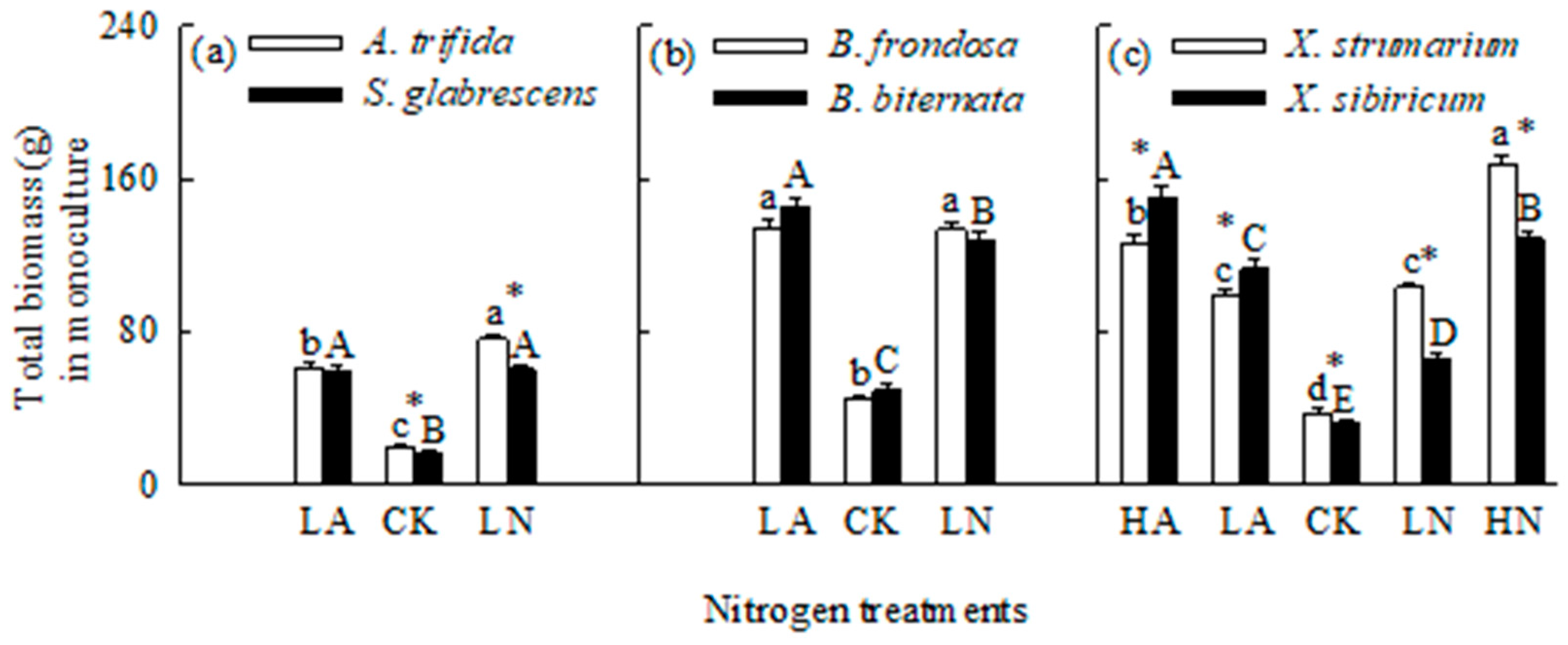

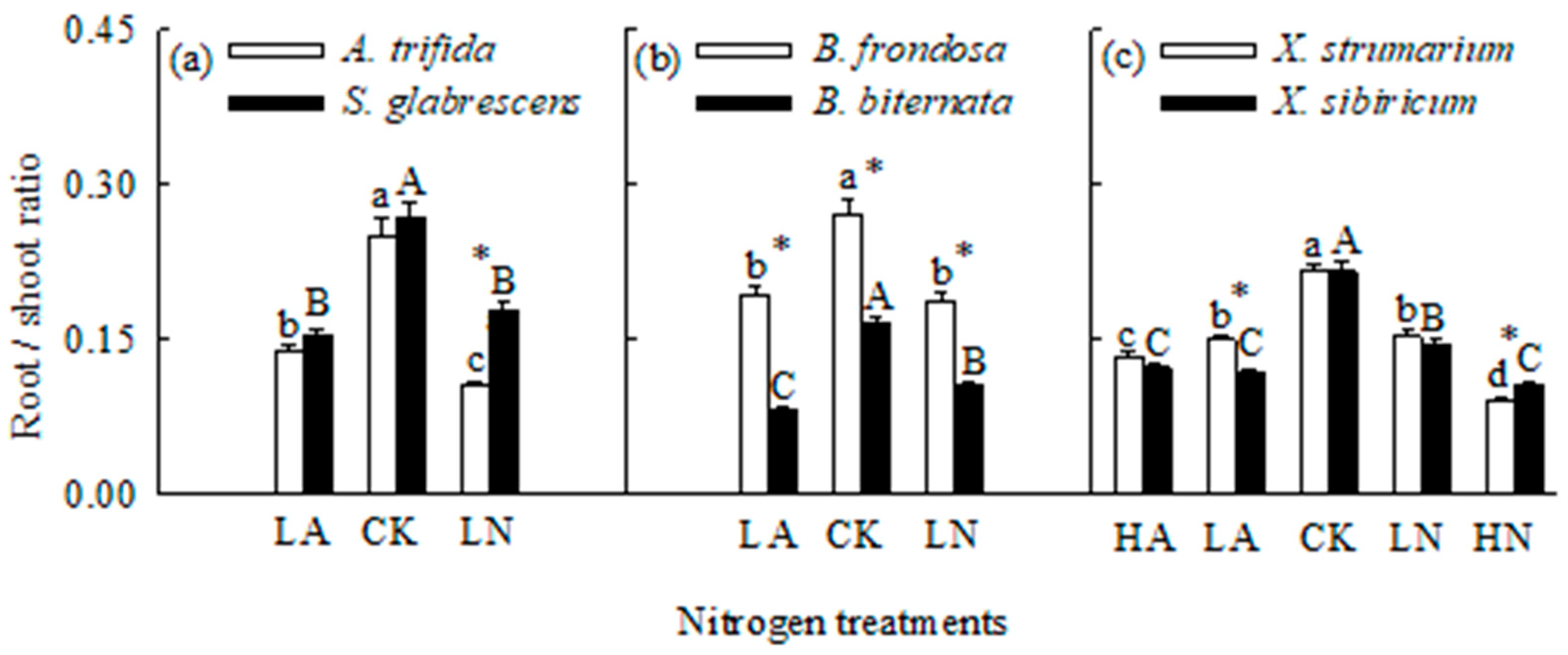

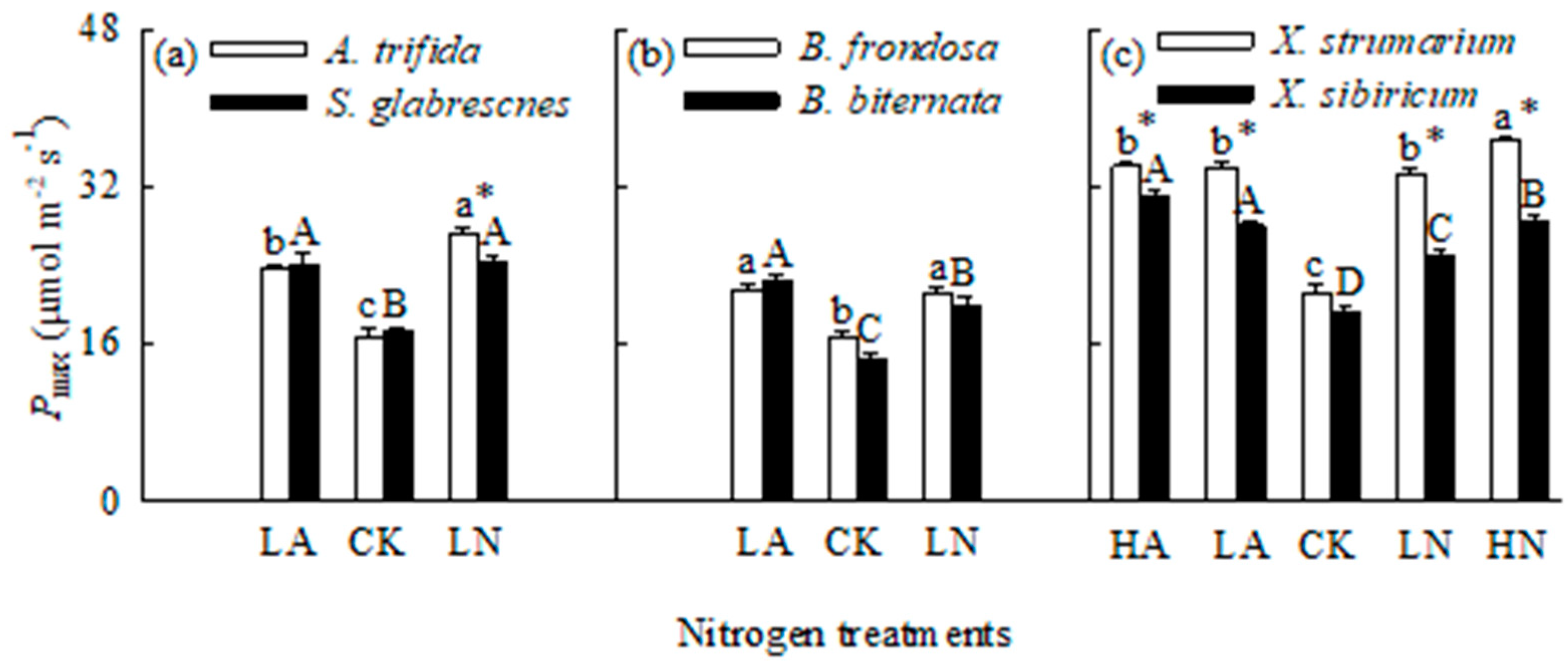

2.1. Total Biomass, Root to Shoot Ratio and Photosynthesis in Monoculture

When grown in monoculture, N addition significantly increased total biomass and

Pmax, but decreased root to shoot ratio for all six species (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). For the invasive plants

A.

trifida and

X.

strumarium (except

X.

strumarium under low N treatments), the increases in total biomass and

Pmax, and the decrease in root to shoot ratio were significantly greater under nitrate relative to ammonium treatment (

Figure 1a, c;

Figure 2a, c;

Figure 3a, c). However, the native plants

B.

biternata and

X.

sibiricum showed greater responses to addition of ammonium relative to nitrate (

Figure 1b, c;

Figure 2b, c;

Figure 3b, c). For

B.

frondosa (invasive) and

S.

glabrescens (native), N forms had no significant effects on these traits (

Figure 1a, b;

Figure 2a, b;

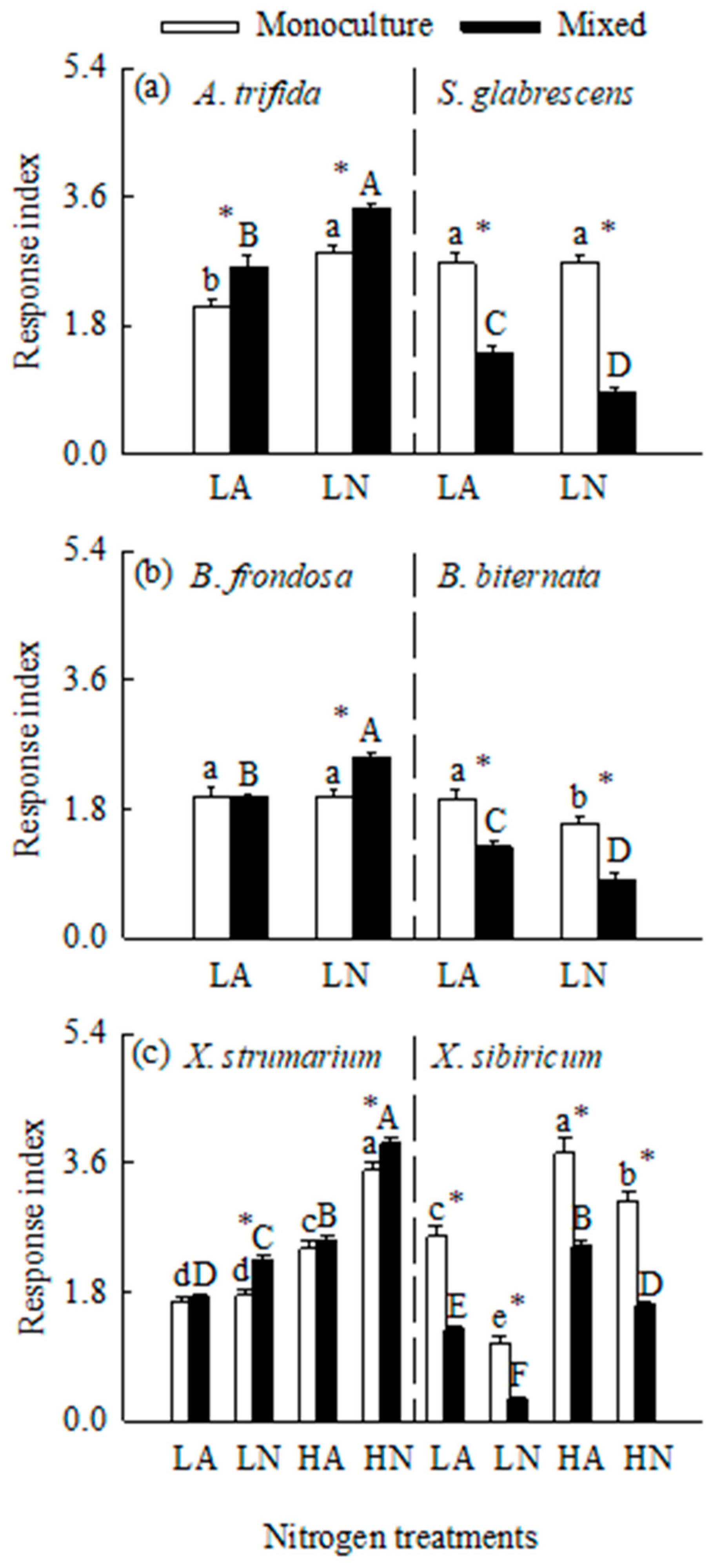

Figure 3a, b). Consistently,

A.

trifida and

X.

strumarium (except

X.

strumarium at low N levels) exhibited stronger responses to nitrate addition compared with ammonium addition,

B.

biternata and

X.

sibiricum to ammonium addition; and

B.

frondosa and

S.

glabrescens showed similarly responses to different N forms (

Figure 4).

The invasive plant

A.

trifida had significantly higher total biomass (also in control treatment) and

Pmax, but lower root to shoot ratio than

S.

glabrescens when grown in nitrate addition treatment, but not in ammonium addition treatment (

Figure 1a,

Figure 2a and

Figure 3a). For total biomass and

Pmax,

B.

frondosa and

B. biternate were similar in all N treatments, while root to shoot ratio was lower for the invader (

Figure 1b,

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b). Total biomass was significantly higher for

X.

strumarium than

X. sibiricum when grown in control and nitrate addition treatments, but lower in ammonium addition treatment (

Figure 1c). This invader had higher

Pmax in all N treatments (not significant in control;

Figure 3c). Root to shoot ratios were not significantly different between

X.

strumarium and

X. sibiricum in most conditions (

Figure 2c).

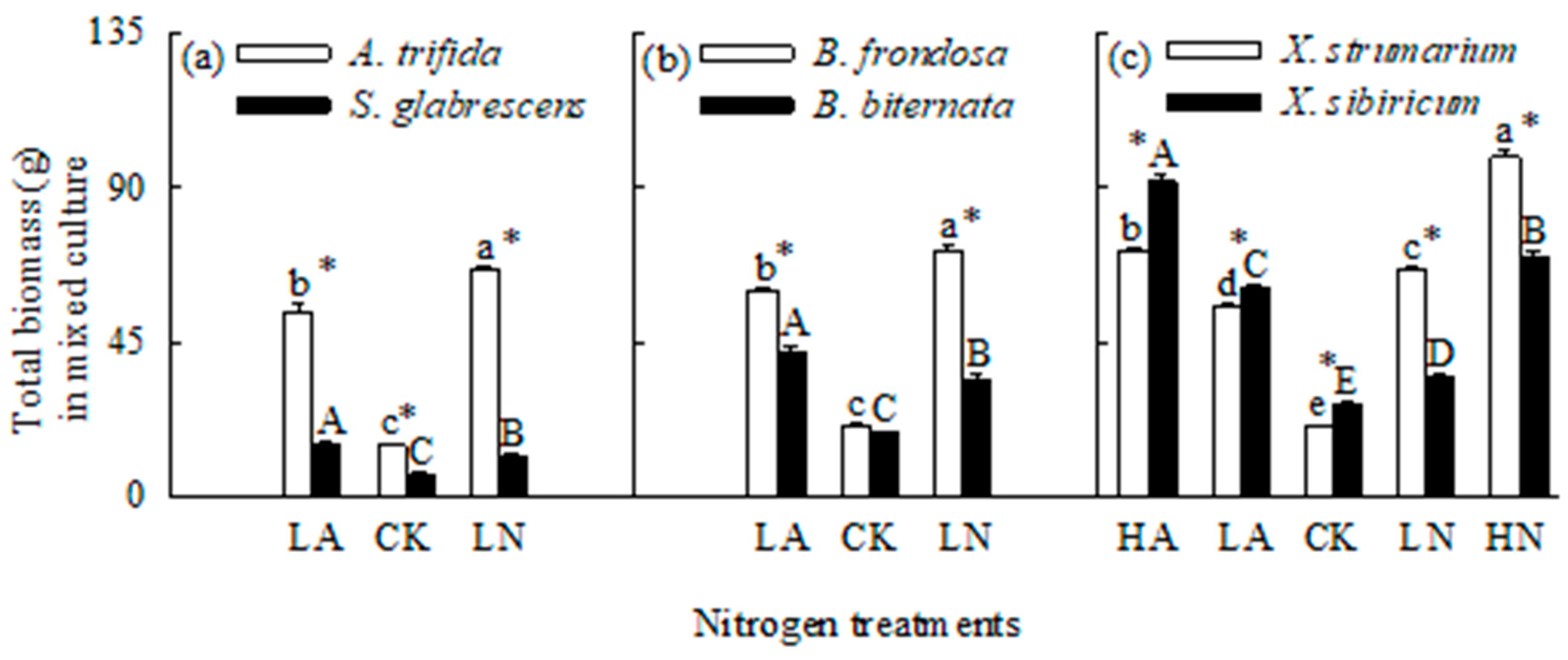

2.2. Total Biomass in Mixed Culture

Interspecific competition greatly decreased total biomass for all six species (

Figure 1 and

Figure 5). N addition also increased total biomass for all six species when grown in mixed culture (

Figure 5). Total biomass was significantly higher for all three invasive plants, but lower for all three natives in nitrate compared to ammonium treatments. Consistently, the invasives responded more greatly to nitrate relative to ammonium addition, while the natives more greatly to ammonium addition (

Figure 4). These results were not consistent with those for

B.

frondosa and

S.

glabrescens grown in monoculture. In addition, competition significantly decreased biomass responses to N addition of both forms for all three natives, while increased biomass response to N addition for

A.

Trifida,

B. frondasa (in nitrate addition) and

X.

strumarium (in nitrate addition) (

Figure 4).

In all N treatments, the invasive plants

A.

Trifida and

B. frondasa (except in control) had significantly higher total biomass than their related natives, respectively, especially under nitrate addition treatments (

Figure 5a, b). For

X.

strumarium compared with its native congener, total biomass was significantly higher in nitrate addition treatment, but lower in ammonium and control treatments (

Figure 5c).

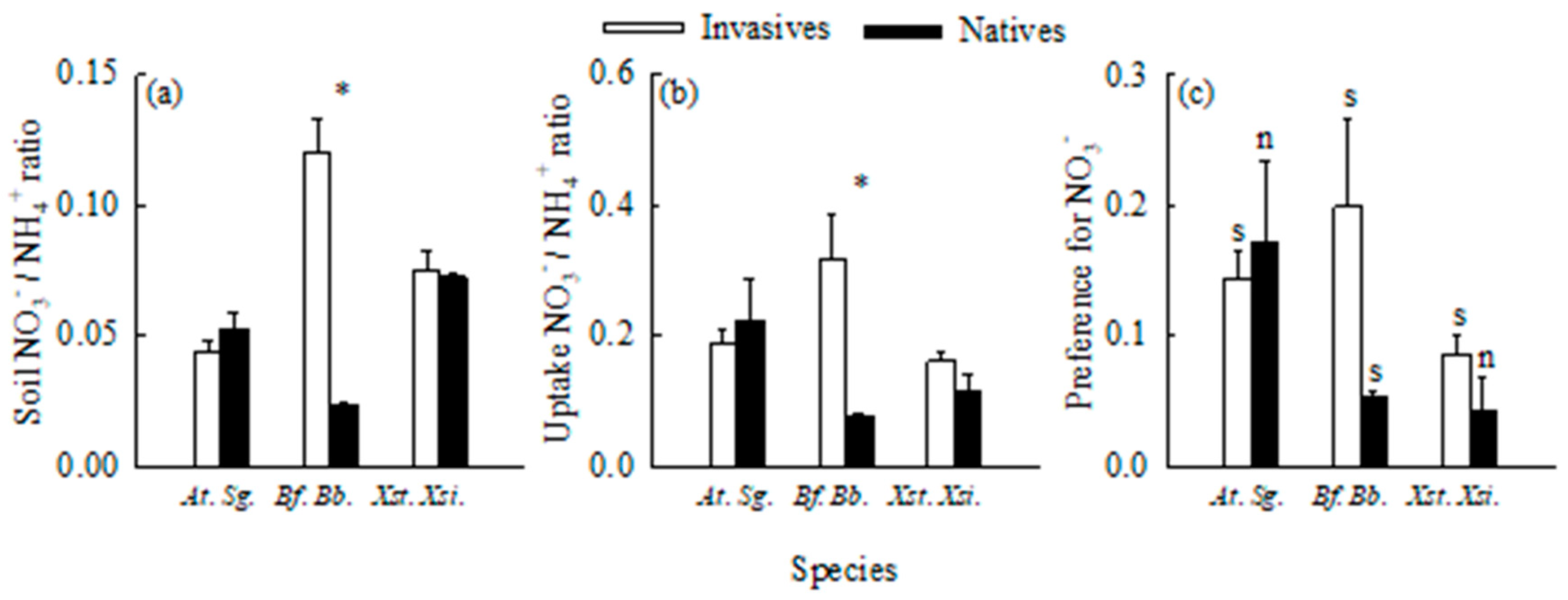

2.3. Uptake of Different Forms of N

Ammonium-N was the dominant soil N form for all six species (

Figure 6a). The ratios of soil nitrate-N to ammonium-N varied between 0.0237 (

B. biternata) and 0.1204 (

B. frondosa), with a mean of 0.0647. Consistently, ammonium-N was the main N form absorbed by all six plants (

Figure 6b). The uptake ratios of nitrate-N to ammonium-N varied from 0.0763 (

B. biternata) to 0.3195 (

B. frondosa), with a mean of 0.1803. However, nitrate-N was the N form preferred by the six species, although the preference was not significant by

X. sibiricum and

S. glabrescens (

Figure 6c).

3. Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, N addition significantly increased total biomass for the invasive plants Ambrosia trifida, Bidens frondosa, and Xanthium strumarium, as well as their related natives. Similar results were also found in numerous references [10,34-38]. However, our study further revealed that the effects of N addition were influenced by both N forms (nitrate vs. ammonium) and planting patterns (mixed vs. monoculture). This underscores the intricate interplay between soil nitrogen dynamics and plant community structure, where soil N forms and availability, along with planting patterns, interact to shape the growth responses of invasive and native species under different environmental conditions.

3.1. Effects of Competition on Responses to N Addition for Invasive Versus Native Plants

As hypothesized, interspecific competition increased growth advantages for all three invasive species over their respective related natives in most cases. For example, competition either initiated (start from scratch; in two cases) or further increased (in three cases) growth advantages for the invasive plants

A. trifida and

B. frondosa over their respective related natives under all N treatments. Competition also led to further increases in growth advantage for the invasive plant

X. strumarium over its native congener under nitrate addition treatments. These results align with the findings that invasive species tend to outperform natives in competitive environments due to their higher N uptake rates and use efficiencies [

32,

39,

40]. When grown in competition, the invasive species may absorb most of the N added (and other nutrients), leaving less for their respective related natives, and thus exacerbating their growth advantage. Consistently, all invaders responded more greatly to N addition when grown in mixed versus monoculture, while the opposite was true for all natives. Our findings further showed that invasive species can more effectively exploit soil available N, particularly in mixed-culture conditions, giving a possible explanation for the stronger growth advantage of the invaders over their related natives when grown in mixed culture compared with monoculture.

Invasive species can enhance nutrient uptakes by increasing colonization rates of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) when grown in competition compared with monoculture [

41,

42]. For example, Sun et al. (2022) found that seven invasive plants showed significantly higher AMF colonization rates when grown in mixed versus monoculture, while their co-occurring natives did not [

42]. Similar results were also found for

X.

strumarium and

X. sibiricum by our group (data not shown), possibly due to root exudates from

X. sibiricum (especially loliolide). Furthermore, we also found through a meta-analysis of published data that invasive relative to native plants have significantly higher AMF colonization rates when grown in interspecific competition (based on 270 comparison), but not when grown in monoculture (based on 327 comparisons; data to be published). The increased AMF colonization rates for invasive species grown in competition may contribute to their enhanced nutrient uptakes, and therefore to their increased growth advantages.

3.2. Effects of Competition on Responses to Different N Forms for Invasive Versus Native Plants

As expectation, interspecific competition also influenced growth responses to different N forms for the invasive and native species. When grown in competition, all invaders responded more greatly to nitrate relative to ammonium N addition (preferring nitrate), while the opposite was true for all natives (preferring ammonium). When grown in monoculture, however, the invasive plant

B. frondosa and the native plant

Siegesbeckia glabrescens no longer showed N form preference as they responded similarly to nitrate versus ammonium. Notably, the preferred N form (nitrate) for the six species was not consistent with the form that they absorbed mostly (ammonium). Furthermore, N form preference (responses to different N forms) for the six studied species grown in mixed culture was also not completely consistent with the results from our

15N labeling experiment (conducted in monoculture). Similarly, the effects of competition on N form preference were also found for the invasive plant

Microstegium vimineum, which preferred nitrate in monoculture but did not show a clear preference for either nitrogen form in mixed culture [

13].

The observed discrepancy in N form preference between mixed and monoculture conditions could be attributed to competition-induced changes in soil N availability and the ratio of nitrate-N to ammonium-N, which have been demonstrated to affect plant N form preference [

32,

38]. In mixed cultures, interspecific competition may likely reduce soil N availability and the proportion of nitrate-N, as the invaders preferentially absorb nitrate. In addition, competition-induced changes in AMF colonization may also contribute to the differential responses to different N forms for the invasive and native species. Competition can influence AMF colonization for both invasive (see the previous paragraph) and native [

43] species. It has been recognized that AMF differs in their ability to acquire different N forms [

44].

Interestingly, for the six studied species N form preference based on our 15N labeling experiment (in monoculture) was also not entirely consistent with the results from our N addition experiment. The discrepancy between the two experimental approaches may be associated with the different methods used. The 15N labeling experiment directly measures N uptake, providing direct insights into plants’ preference for N forms, while the N addition experiment assesses the overall growth responses, which are influenced by competition and other environmental factors. Our results highlight the complexity of N form preference in plants, as they are modulated not only by soil N forms and availability but also by interspecific competition.

3.3. Effects of N Forms on Alien Plant Invasions

As expectation, N forms significantly influenced the differences in growth and its responses to N addition between the three invasive species and their respective related natives. Growth advantages were higher for the invaders over their related natives under nitrate relative to ammonium N addition when grown in mixed culture, indicating that habitats with higher nitrate-N availability or proportions are more vulnerable to invasive plants. Consistently, invasive plants are frequently occurred in disturbed habitats such as roadsides, riversides, wastelands, farmlands, and secondary forests [

25], where soil nitrification rates are generally high, leading to increased soil nitrate availability [

18,

22]. These findings underscore that global change, for example atmospheric N deposition, human disturbance on natural ecosystems, and agricultural non-point source pollution, may exacerbate alien plant invasions by altering soil N dynamics.

For the invasive plant

X. strumarium, preference for nitrate over ammonium was also found in other studies with controlled experiments [

11,

20,

45]. This invader may also prefer nitrate in the field, as judged by its higher pH and net nitrification rates in rhizosphere soils compared with its native congener. It is well known that invasive plants with a preference for nitrate can increase soil pH, enhancing nitrification [

15,

46,

47]. For

X. strumarium, the ability to absorb and assimilate nitrate-N relative to ammonium-N is higher, while the opposite is true for

X. sibiricum [

11,

20,

45]. The invader is more susceptible to ammonium toxicity than

X. sibiricum, also inhibiting its growth under high ammonium levels [

45]. In addition, the invader had higher photosynthesis and a lower root to shoot ratio under nitrate relative to ammonium N addition, contributing to its higher total biomass. These results all indicate that the invader is more likely to invade habitats with high nitrate-N. More interestingly,

X. strumarium can release choline into soil, increasing soil nitrification, nitrate content, and thus facilitating invasiveness (unpublished data).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experiment I: Responses to N Forms and Levels

Study site and species

This study was conducted at a common garden in the experimental base (41° 50′ N, 123° 34′ E; 59 m asl) of Shenyang Agricultural University located in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, northeast China. This site has a temperate continental monsoon climate, with a hot, moist summers and cold, dry winters. The mean annual temperature is 8.1 oC, and the mean annual precipitation is 721.9 mm, with most rainfall occurring in July and August.

This study focused on three invasive annual herbaceous species from Asteraceae:

Xanthium strumarium L.

, Ambrosia trifida L., and

Bidens frondosa Buch.-Ham. ex Hook.f.. These species, native to North America, have become notorious invaders in China, causing severe environmental and socio-economic problems.

Xanthium strumarium was first found in Beijing in 1991,

A. trifida in Liaoning in 1949, and

B. frondosa in Jiangsu in 1926 [

25]. In northeast China,

X. strumarium and

B. frondosa were first documented in Liaoning in 2007 and Heilongjiang in 1950, respectively. Today, these invasive species are widespread across many provinces in China, particularly in disturbed habitats [

25]. To better understand their invasive mechanisms, we compared these species with their phylogenetically related natives, as related species share more similar life history and functional traits [

10,

48]. Specifically,

X. strumarium and

B. frondasa were compared with

X.

sibiricum Patrin ex Widder and

B.

biternata L., respectively.

Ambrosia trifida has no native congeners in China, and were compared with

Sigesbeckia glabrescens M., a native forb from the same tribe (Trib. Heliantheae Cass). All three natives often co-occur with their invasive relatives in Liaoning, northeast China.

Seeds of each species were collected from more than ten individuals (spaced > 20 m apart) in a disturbed habitat near the Hunhe River (41° 49′ N, 123° 34′ E; 28 m asl) in Fushun, Liaoning Province. The seeds were stored at 4 oC until used.

Seed germination and seedling transplant

In mid-April, full and healthy seeds of each species were soaked separately in distilled water for 30 min, and then placed in petri dishes with wet filter papers for germination. Germination was conducted in growth chambers with 25 / 22

oC (day / night) and 108 μmol m

-2 s

-1 light intensity (12/12 h photoperiod). For

X.

strumarium and

X.

sibiricum, only the lower seeds were used due to their larger size and shorter dormancy time compared with the upper seeds [

49,

50]. Before germination, the seeds had been stratified in wet sand at 4

oC for two months.

After germination, the seeds were transferred into seedling trays filled with a substrate mixture of forest topsoil (0-10 cm) and medium-grained sand (7:3 ratio), and grown in a greenhouse. Similarly-sized seedlings (≈ 10 cm tall) for each invasive-native species pair were transplanted into pots (30 cm in diameter). Two planting methods were applied for each species pair: monoculture (one seedling per pot) and mixed culture (one invasive and one native seedling per pot, spaced 5 cm). For the substrate, the contents of organic matter, total N, total phosphorus, total potassium, available N, available phosphorus, and available potassium 5.57 mg g-1, 0.31 mg g-1, 0.57 mg g-1, 13.6 mg g-1, 20.99 μg g-1, 5.99 μg g-1, and 55.69 μg g-1, respectively.

Nitrogen treatments

One week after transplantation, seedlings of

X.

strumarium and

X.

sibiricum were subjected to five treatments, and 12 replicates per treatment: control (no N addition), low ammonium (40 mmol NH

4H

2PO

4 and 40 mmol KH

2PO

4 per pot), high ammonium (80 mmol NH

4H

2PO

4 and 80 mmol KH

2PO

4), low nitrate (40 mmol KNO

3 and 80 mmol H

3PO

4), and high nitrate (80 mmol KNO

3 and 160 mmol H

3PO

4). The nutrients were evenly added in four times, at intervals of 10 days. Seedlings from the other two species pairs were treated with only three treatments: control, low ammonium, and low nitrate, without high ammonium and high nitrate treatments. To inhibit potential transformation of ammonium to nitrate, 0.8 mmol thiourea was added to each pot [

51].

Measurements

About 50 d after seedling transplantation, light-saturated photosynthetic rate (Pmax) was measured for each species grown in monoculture using a Li-6400 Portable Photosynthesis Meter (Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). Light intensity on leaf surface, relative humidity in leaf chamber, CO2 concentration in reference chamber, and leaf temperature were controlled at 1500 μmol m-2 s-1, 50%, 380 μmol mol-1, and 25 oC, respectively. Then, six individuals per species per N and competition treatment were randomly chosen and harvested. Each individual was separated into shoots and roots, dried at 60 oC for 72 h, and weighed. Total biomass was calculated as the sum of root and shoot biomass; root to shoot ratio was determined as the ratio between root and shoot biomass; the response index to N addition was calculated as the relative change in total biomass: (total biomass under N addition – mean total biomass under control) / mean total biomass under control.

4.2. Experiment II: Uptake of Different Forms of N

The seedlings were prepared using a similar method as described in Experiment I. However, smaller pots (15 cm in diameter), less substrate (1.5 kg), and only monoculture (one seedling per pot) were used. In total, 180 pots were prepared (6 species × 30 replicates). The pots for each species pair were randomly arranged in a block within the common garden, spaced 60 cm, while blocks for different species pairs were spaced 2 m. The pots were watered daily and weeded when necessary.

Four-five days after seedling transplantation, when the plants grew at vigorous vegetative stage, the

15N isotope labeling method was used to quantify plant uptake of ammonium-N and nitrate-N. Nine individuals of each species with similar size were selected for three treatments:

15N-ammonium labeling [(

15NH

4)

2SO

4],

15N-nitrate labeling (K

15NO

3), and control (distilled water), with three replicates for each treatment. Around each seedling (

r = 3.0 cm), 45 mL of 4.76 mmol N L

-1 labeling solution (

15N > 99%) or distilled water was injected into the soil (0-10 cm), based on preliminary experiments. For details, refer to Guan et al. (2023) [

32]. This method ensured even dispersion of the injected solution within the pots, and the content of the

15N added was 2.1 μg g

-1 dry soil.

Shoots and roots of the labeled and control plants were collected after two hours of

15N labeling. The roots were immersed into 0.5 mmol L

-1 CaCl

2 solution for 30 min to remove the

15N adhered to root surface [

38], and then rinsed twice with deionized water. The shoots and roots from the same plant were dried at 60

oC for 72 h, and weighed. Both parts were mixed, ground into powder, and analyzed for total N content and

15N atom% excess with an elemental analysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (Flash 2000HT + Delta V Advantage, Thermo, Germany).

For each species, rhizosphere soil from each control individual was collected using the method described by Zhao et al. (2020), and sieved through a 2 mm mesh [

5]. Soil ammonium and nitrate were extracted with 2 mol L

-1 KCl, and quantified using an Automated Chemistry Analyzer (AA3, Seal, Germany). For each labeled individual of each species. rhizosphere soil content of the N with a specific form was calculated as the sum of the mean value of the measured contents for the control individuals and the amount of

15N added into soil (2.1 μg g

-1). The ratios of nitrate-N to ammonium-N were also calculated.

For each labeled individual, the uptake of the labeled

15N from a specific form (

15NH

4+ or

15NO

3-) was calculated using their

15N atom% excess (APE), total biomass (shoots and roots), and total N contents. The actual N uptake (including both ¹⁴N and ¹⁵N) was calculated for each labeled individual based on the uptake of the labeled ¹⁵N and the ratio of the labeled ¹⁵N to N naturally occurring in soil. This method assumes that

14N /

15N isotope fractionation is negligible when plants are exposed to a low concentration of labeled N [

32]. The uptake rate of each N form was then determined using the amount of N absorbed by each labeled individual, its root biomass, and labeling duration (2 h). Finally, the preference in N form uptake were calculated for the labeled plants. For details, refer to Guan et al. (2023) and Sun et al. (2025) [

32,

38].

4.3. Statistical Analyses

One-way ANOVA was used to test the difference in each variable among N treatments for each species, and that among each invasive and its related native species under different N treatments in the same planting pattern (mixed or monoculture). Independent samples t-test was applied to compare the difference between each invasive and its related native species under each N treatment, the difference between mixed and monoculture for each invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment, and that between preference for nitrate and zero for each species (P < 0.05 indicates significant preference for nitrate). Data were transformed when necessary to meet the requirements of ANOVA. All analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

5. Conclusion

Our results show that N forms significantly affect invasions of alien plant species besides soil N availability, and the effects of soil N availability are further shaped by N forms and planting patterns (mixed versus monoculture), with mixed-culture experiments proving a more comprehensive understanding of alien plant invasions. When grown in competition with their respective related native species, the invasive plants A. trifida, B. frondosa, and X. strumarium responded more positively to addition of nitrate relative to ammonium N, while the natives more strongly to ammonium-N, indicating that the invaders prefer nitrate, while the natives prefer ammonium. Growth advantages of the invaders over their related natives were greater under addition of nitrate relative to ammonium N, indicating that nitrate-rich habitats may be more vulnerable to the invaders. Our results indicate that global change-driven alterations in soil N forms may facilitate alien plant invasions, highlighting the importance of considering soil N forms when studying effects of global change such as atmospheric N deposition and human disturbance on invasions of introduced species. Our study also underscores the importance of considering interspecific interactions when studying invasion mechanisms and impacts in the context of global change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F.; methodology, Y.F. and B.Q.; software, J.S., M.L., and M.G.; data curation, W.F., K.H., and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.F., K.H., S.S., and F.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.F., J.S., and M.G.; and all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2604500), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32471753, 32171666 and 31971557).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Analysis and Testing Center of Shenyang Agricultural University for assistance for chemical measurements, the handling editor and the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on an early version of this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Vilà:, M.; Espinar, J.L.; Hejda, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Jarošík, V.; Maron, J.L. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: a meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Jarošík, V.; Hulme, P.E.; Pergl, J.; Hejda, M.; Schaffner, U. A global assessment of invasive plant impacts on resident species, communities and ecosystems: the interaction of impact measures, invading species’ traits and environment. Global Change Biol. 2012, 18, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.L.; Feng, Y.L.; Zhang, L.K.; Callaway, R.M.; Valiente-Banuet, A.; Luo, D.Q.; Liao, Z.L.; Lei, Y.B.; Barclay, G.F.; Silva-Pereyra, C. Integrating novel chemical weapons and evolutionarily increased competitive ability in success of a tropical invader. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.F.; Liu, M.C.; Iram, A.; Feng, Y.L. Effects of the invasive plant Xanthium strumarium on diversity of native weed species: A competitive analysis approach in North and Northeast China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Liu, M.C.; Feng, Y.L.; Wang, D.; Feng, W.W.; Clay, K.; Durden, L.A.; Lu, X.R.; Wang, S.; Wei, X.L.; Kong, D.L. Release from below- and aboveground natural enemies contributes to invasion success of a temperate invader. Plant Soil, 2020; 452, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- van Wilgen, B.W.; Richardson, D.M. Challenges and trade-offs in the management of invasive alien trees. Biol. Invasions 2014, 16, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.J.; Dise, N.B.; Stevens, C.J.; Gowing, D.J.; Partners, B.N. Impact of nitrogen deposition at the species level. P. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013, 110, 984–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storkey, J.; Macdonald, A.J.; Poulton, P.R.; Scott, T.; Köhler, I.H.; Schnyder, H.; Goulding, T.W.K.; Crawley, J.M. Grassland biodiversity bounces back from long-term nitrogen addition. Nature 2015, 528, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.M.; Montesinos, D.; Thelen, G.C.; Callaway, R.M. Growth and competitive effects of Centaurea stoebe populations in response to simulated nitrogen deposition. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.B.; Wang, W.B.; Feng, Y.L.; Zheng, Y.L. Synergistic interactions of CO2 enrichment and nitrogen deposition promote growth and ecophysiological advantages of invading Eupatorium adenophorum in Southwest China. Planta 2012, 236, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, S.T.; Li, J.Z.; Feng, Y.L. Molecular bases for the stronger plastic response to high nitrate in the invasive plant Xanthium strumarium compared with its native congener. Planta 2023, 258, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.N.; Liu, L.L.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, T. Nitrogen deposition enhances the competitive advantage of invasive plant species over common native species through improved resource acquisition and absorption. Ecol. Process 2024, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R.; Flory, S.L.; Phillips, R.P. Positive feedbacks to growth of an invasive grass through alteration of nitrogen cycling. Oecologia 2012, 170, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, C.H.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, X.W.; Liu, H.M.; Wang, H.; Yang, D.L. Response of an invasive plant, Flaveria bidentis, to nitrogen addition: a test of form-preference uptake. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 3365–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.B.; Wang, J.; Müller, C.; Cai, Z.C. Ecological and practical significances of crop species preferential N uptake matching with soil N dynamics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016; 103, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Konaré, S.; Boudsocq, S.; Gignoux, J.; Lata, J.C.; Raynaud, X.; Barot, S. Effects of mineral nitrogen partitioning on tree-grass coexistence in West African savannas. Ecosystems 2019, 22, 1676–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.X.; He, N.P.; Wang, Q.F.; Yuan, G.F.; Wen, D.; Yu, G.R.; Jia, Y.L. The composition, spatial patterns, and influencing factors of atmospheric wet nitrogen deposition in Chinese terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.B.; Muller, C.; Cai, Z.C. Soil gross nitrogen transformations along a secondary succession transect in the north subtropical forest ecosystem of Southwest China. Geoderma, 2016, 280, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W.X.; Tang, A.H.; Shen, J.L.; Cui, Z.L.; Vitousek, P.; Erisman, W.J.; Goulding, K.; Christie, P.; Fangmeier, A.; Zhang, F.S. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 2013, 494, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.J.; Gao, Y.M.; Feng, W.W.; Liu, M.C.; Qu, B.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.L. Stronger ability to absorb nitrate and associated transporters in the invasive plant Xanthium strumarium compared with its native congener. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 198, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon-Firestone, S.; Reynolds, H.L.; Phillips, R.P.; Flory, S.L.; Yannarell, A. The role of ammonium oxidizing communities in mediating effects of an invasive plant on soil nitrification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; He, T.G.; Chen, H.; Wang, K.L.; Li, D.J. Dynamics of soil gross nitrogen transformations during post-agricultural succession in a subtropical karst region. Geoderma 2019, 341, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.Y.; Jia, Z.J. Meta-analysis of soil nitrification activity in ecosystems typical of China. Acta Pedologica Sinica 2014, 51, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.W.; Sung, Y.; Chen, B.C.; Lai, H.Y. Effects of nitrogen fertilizers on the growth and nitrate content of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He. 2014, 11, 4427–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.L. Invasive Plants in Northeast China (Beijing: Science Publication House). 2020.

- Davis, M.; Grime, J.P.; Thompson, K. Fluctuating resources in plant communities: a general theory of invisibility. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Macko, S.A. Constrained preferences in nitrogen uptake across plant species and environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.C.; Lei, Y.B.; Tan, Y.H.; Sun, X.C.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.Q.; Liu, X.Y. Plant nitrogen and phosphorus utilization under invasive pressure in a montane ecosystem of tropical China. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, I.W.; Miller, A.E.; Bowman, W.; Suding, K.N. Niche complementarity due to plasticity in resource use: Plant partitioning of chemical N forms. Ecology 2010, 91, 3252–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.B.; Chen, B.M. Considering the preferences for nitrogen forms by invasive plants: A case study from a hydroponic culture experiment. Weed Res. 2019, 59, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Gu, Y.R.; Tian, X.S.; Li, W.H. Responses of the invasive plant Wedelia trilobata to NH4+-N and NO3−-N. Journal of South China Normal University (Natural Science Edition) 2015, 47, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, M.; Pan, X.C.; Sun, J.K.; Chen, J.X.; Kong, D.L.; Feng, Y.L. Nitrogen acquisition strategy and its effects on invasiveness of a subtropical invasive plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1243849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, J.Z.; Liu, M.; Yan, Z.Q.; Xu, X.L.; Kuzyakov, Y. Invasive plant competitivity is mediated by nitrogen use strategies and rhizosphere microbiome. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.L.; Lei, Y.B.; Wang, R.F.; Callaway, R.M.; Valiente-Banuet, A.; Inderjit; Li, Y.P.; Zheng, Y.L. Evolutionary tradeoffs for nitrogen allocation to photosynthesis versus cell walls in an invasive plant. P. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009, 106, 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.L.; Li, Y.P.; Wang, R.F.; Callaway, R.M.; Valiente-Banuet, A.; Inderjit. A quicker return energy-use strategy by populations of a subtropical invader in the non-native range: a potential mechanism for the evolution of increased competitive ability. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.Y.; Zhang, R.; Barclay, G.F.; Feng, Y.L. Differences in competitive ability between plants from nonnative and native populations of a tropical invader relates to adaptive responses in abiotic and biotic environments. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, R.M.; Zheng, Y.L.; Valiente-Banuet, A.; Callaway, R.M.; Barclay, G.F.; Pereyra, C.S.; Feng, Y.L. The evolution of increased competitive ability, innate competitive advantages, and novel biochemical weapons act in concert for a tropical invader. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.K.; Liu, M.C.; Chen, J.X.; Qu, B.; Gao, Y.; Geng, L.; Zheng, L.; Feng, Y.L. Higher nitrogen uptake contributes to growth advantage of the invasive Solanum rostratum over two co-occurring natives at different nitrogen forms and concentrations. Plants 2025, 14, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Kong, D.L.; Lu, X.R.; Feng, W.W.; Liu, M.C.; Feng, Y.L. Lesser leaf herbivore damage and structural defenses and greater nutrient concentrations for invasive alien plants: evidence from 47 pairs of invasive and non-invasive plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 137829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Dong, T.F.; Feng, W.W.; Qu, B.; Kong, D.L.; van Kleunen, M.; Feng, Y.L. Leaf trait differences between 97 pairs of invasive and native plants across China: effects of identities of both the invasive and native species. Neobiota 2022, 71, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.J.; Li, Q.; Yerger, E.H.; Chen, X.; Shi, Q.; Wan, F.H. AM fungi facilitate the competitive growth of two invasive plant species, Ambrosia artemisiifolia and Bidens pilosa. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.S.; Yang, X.P.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Ding, P.C.; Song, X.E. Stronger mutualistic interactions with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi help Asteraceae invaders outcompete the phylogenetically related natives. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Q.; Guo, X.C.; Lu, X.Y.; Liu, M.C.; Zang, H.Y.; Feng, Y.L.; Kong, D. L, A review on the effects of invasive plants on mycorrhizal fungi of native plants and their underlying mechanisms. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2020, 44, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.M.; Chen, J.X.; Feng, W.W.; Zhang, C.; Huang, K.; Guan, M.; Sun, J.K.; Liu, M.C.; Feng, Y.L. Plant strategies for nitrogen acquisition and their effects on exotic plant invasions. Biodiv. Sci. 2021, 29, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.S.; Wang, W.B.; Feng, Y.L. Differences and related physiological mechanisms in effects of ammonium on the invasive plant Xanthium strumarium and its native congener X. sibiricum. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 999748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.Y.; Gerendás, J.; Härdter, R.; Sattelmacher, B. Effect of nitrogen form and root-zone pH on growth and nitrogen uptake of tea (Camellia sinensis) plants. Ann. Bot. 2007, 99, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. Ecological significance and complexity of N-source preference in plants. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Y.; Lv, Y.N.; Liu, X.Y.; Wang, L. Ecological effects of atmospheric nitrogen deposition on soil enzyme activity. J. Forestry Res. 2013, 24, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbert, E. Ecological consequences and ontogeny of seed heteromorphism. Perspect. Plant Ecol. 2002, 5, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Liu, X.J.; Mao, R.Z.; An, P.; Qiao, H.L.; Huang, W.; Li, Z.L. Advances in plant seed dimorphism (or polymorphism) research. Acta Ecol. Sinica 2006, 26, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Amberger, A. Research on dicyandiamide as a nitrification inhibitor and future outlook. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan. 1989, 20, 1933–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Total biomass for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and native (closed bars) species grown singly under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species, respectively (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 1.

Total biomass for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and native (closed bars) species grown singly under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species, respectively (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 2.

Root to shoot ratios for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and native (closed bars) species grown singly under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 2.

Root to shoot ratios for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and native (closed bars) species grown singly under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 3.

Maximum net photosynthetic rates for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and related native (closed bars) species grown singly under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 3.

Maximum net photosynthetic rates for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and related native (closed bars) species grown singly under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 4.

Response indices to different N forms and levels for the three pairs of invasive and related native species grown under different N forms and levels under the conditions without (open bars) and with (closed bars) competition. LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among invasive and its related native species grown in different N treatments under the conditions without and with competition, respectively (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between mixed and monoculture for invasive (left) and its related native (right) species grown under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 4.

Response indices to different N forms and levels for the three pairs of invasive and related native species grown under different N forms and levels under the conditions without (open bars) and with (closed bars) competition. LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among invasive and its related native species grown in different N treatments under the conditions without and with competition, respectively (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between mixed and monoculture for invasive (left) and its related native (right) species grown under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 5.

Total biomass for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and related native (closed bars) species grown in mixed under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species, respectively (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 5.

Total biomass for the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and related native (closed bars) species grown in mixed under different N forms and levels. CK, control; LA, low ammonium-N addition; LN, low nitrate-N addition; HA, high ammonium-N addition; HN, high nitrate-N addition. Mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower- and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among N treatments for invasive and its related native species, respectively (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA); * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species under the same N treatment (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test).

Figure 6.

The ratios of nitrate-N to ammonium-N in soils (a), the ratios of nitrate-N to ammonium-N absorbed by roots (b), and preference indices for nitrate-N (c) in the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and related native (closed bars) plant species. At., Ambrosia trifida; Sg., Sigesbeckia glabrescens; Bf., Bidens frondosa; Bt., B. biternata; Xst., Xanthium strumarium; Xsi., X. sibiricum. Mean ± SE (n = 5 for panel a; n = 3 for panels b and c). * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test); s and n in panel c indicate significant and non-significant difference from zero (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test), respectively.

Figure 6.

The ratios of nitrate-N to ammonium-N in soils (a), the ratios of nitrate-N to ammonium-N absorbed by roots (b), and preference indices for nitrate-N (c) in the three pairs of invasive (open bars) and related native (closed bars) plant species. At., Ambrosia trifida; Sg., Sigesbeckia glabrescens; Bf., Bidens frondosa; Bt., B. biternata; Xst., Xanthium strumarium; Xsi., X. sibiricum. Mean ± SE (n = 5 for panel a; n = 3 for panels b and c). * indicates significant difference between invasive and its related native species (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test); s and n in panel c indicate significant and non-significant difference from zero (P < 0.05; independent samples t-test), respectively.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).