Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Nitrogen Uptake Rates of Emergent Plants in Water with Different NH4+/NO3- Ratios

2.2. Nitrogen Assimilation Enzyme Activities of Emergent Plants in Water with Different NH4+/NO3- Ratios

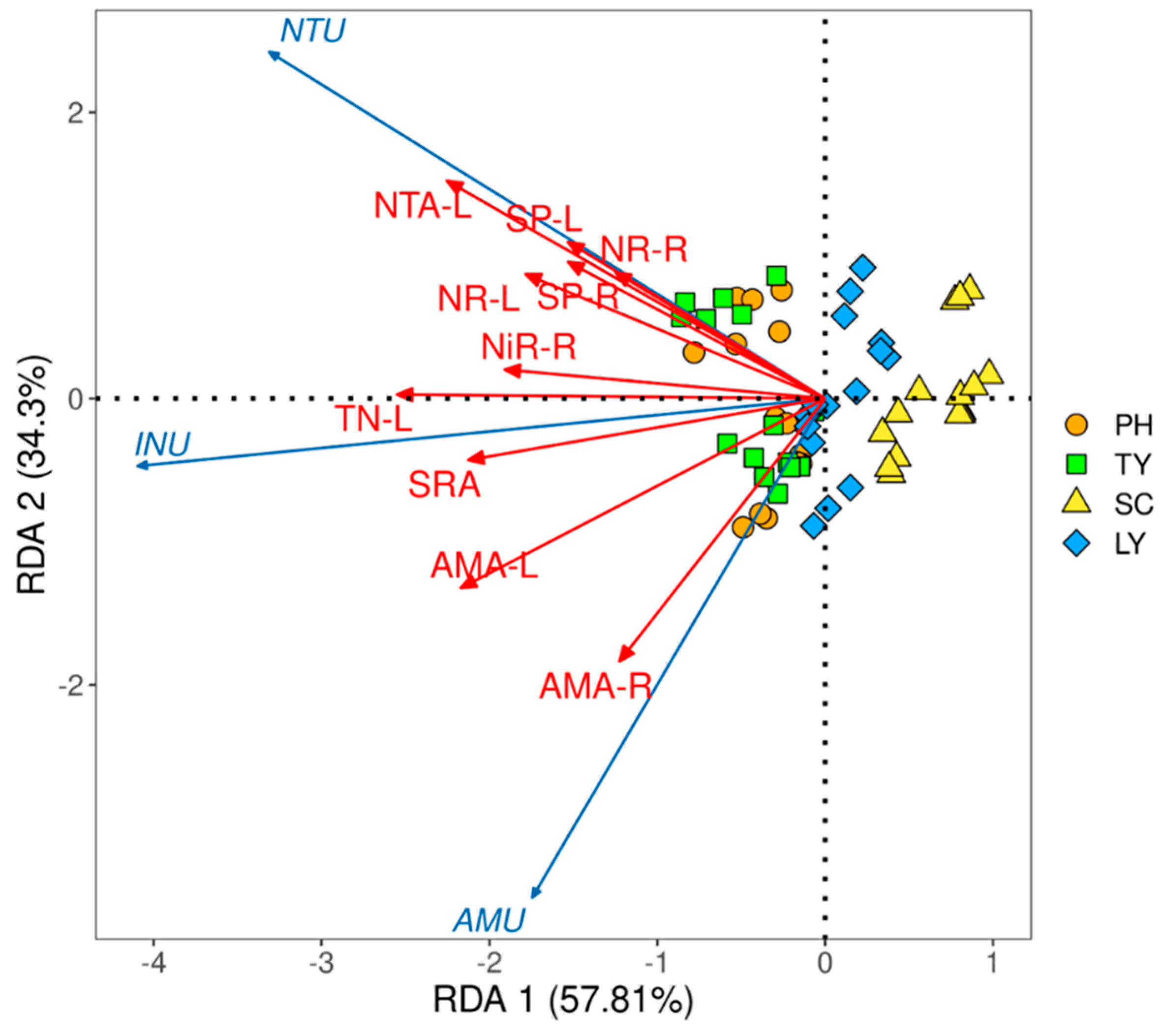

2.3. Influencing Factors on Nitrogen Uptake Rates of Different Emergent Plants

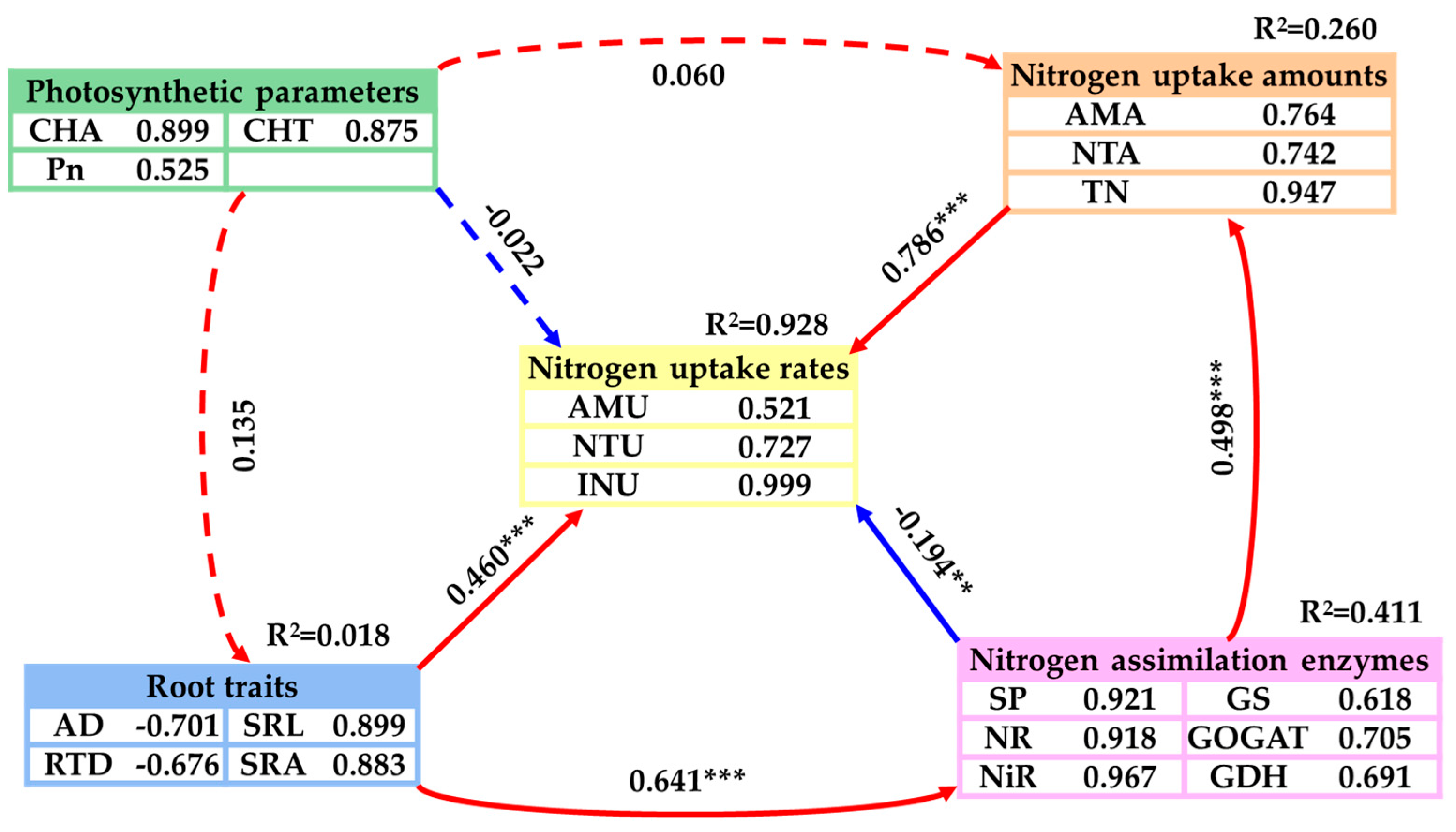

2.4. The Main Driving Factors of Nitrogen Uptake Rate of Emergent Plants

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Different Forms of Nitrogen on Nitrogen Uptake Rate of Emergent Plants

3.2. Effects of Different Forms of Nitrogen on Nitrogen Assimilation Enzyme Activity in Emergent Plants

3.3. Factors Influencing Nitrogen Uptake Rate of Different Emergent Plants

3.4. The Main Drivers of Nitrogen Uptake Rate in Emergent Plants

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Desig

4.2. Sampling and Measurements

4.3. Calculations of Various Indicators

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khanna, K.; Kohli, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Kour, J.; Devi, K.; Bhardwaj, T.; Dhiman, S.; Singh, A.D.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, A.; et al. Phytomicrobiome communications: novel implications for stress resistance in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 912701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Zang, S. Purification mechanism of emergent aquatic plants on polluted water: a review. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 375, 124198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Yang, R.; Cao, Q.; Dong, J.; Li, C.; Quan, Q.; Huang, M.; Liu, J. Differences of the microbial community structures and predicted metabolic potentials in the lake, river, and wetland sediments in dongping lake basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 19661–19677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Shi, W.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Hou, L.; Yang, H.; Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Yang, Q.; et al. Coordination of nitrogen uptake and assimilation favours the growth and competitiveness of moso bamboo over native tree species in high-NH4+ environments. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 266, 153508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheng, X.; Kong, X.; Jia, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals the negative response mechanism of peanut root morphology and nitrate assimilation to nitrogen deficiency. Plants 2023, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen assimilation in plants: current status and future prospects. J. Genet. Genomics 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, S.; Zhou, F.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L. Removal of ammonia nitrogen from black and odorous water by macrophytes based on laboratory microcosm experiments. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3173–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, S.; Robledo-Arratia, L.; Glowacka, K.; Gupta, M. Root NRT, NiR, AMT, GS, GOGAT and GDH expression levels reveal NO and ABA mediated drought tolerance in brassica juncea l. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao-jiao, G.; Hong-wei, Z.; Yan, J.; Bo-wen, H.; Zhuo-qian, W.; Zhao-jun, Q.; Feng-li, Y. Effect of salt stress on nitrogen assimilation of functional leaves and root system of rice in cold region. Journal of Northeast Agricultural University (English Edition). 2020, 27, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X.; Wang, X.; Pan, J.; Deng, W.; Li, Y. Role of nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase in NaCl tolerance in eelgrass (zostera marina l.). Ecological Chemistry and Engineering S 2022, 29, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Lin, J.; Dong, L.; Liu, C.; Tang, D.; Yan, L.; Chen, M.; Liu, S.; Liu, X. Overexpression of an NADP(h)-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase gene, TrGDH, from trichurus improves nitrogen assimilation, growth status and grain weight per plant in rice. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhu, K.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Qiao, Z.; Tan, P.; Peng, F. Ammonium-nitrate mixtures dominated by NH4+-N promote the growth of pecan (carya illinoinensis) through enhanced N uptake and assimilation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1186818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. Role of glutamine synthetase, glutamine and NH4+ in the regulation of NO2- uptake in the cyanobiont nostoc ANTH. J. Plant Physiol. 1993, 142, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yang, J.; Jeong, B.R. Growth, quality, and nitrogen assimilation in response to high ammonium or nitrate supply in cabbage (brassica campestris l.) And lettuce (lactuca sativa l.). Agronomy 2021, 11, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.A.; Slade, A.P.; Fox, G.G.; Phillips, R.; Ratcliffe, R.G.; Stewart, G.R. The role of glutamate dehydrogenase in plant nitrogen metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1991, 95, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wan, T.; Gong, Y.; Dai, C.; Ochieng, W.A.; Nasimiyu, A.T.; Li, W.; Liu, F. Glutamate dehydrogenase plays an important role in ammonium detoxification by submerged macrophytes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, R.L.; Gosselink, J.G. Global treatment wetlands. Wetlands 2001, 21, 648–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.R.; Wu, Y.; Hu, C.C.; Liu, X.Y. Elevated nitrate preference over ammonium in aquatic plants by nitrogen loadings in a city river. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2022, 127, e2021JG006614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Qin, X.; Ma, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Seasonal shifting in the absorption pattern of alpine species for NO3- and NH4+ on the tibetan plateau. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2019, 55, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Wang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, N. Differential uptake of nitrogen forms by two herbs in the gurbantunggut desert, central asia. Plant Biol. 2022, 24, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaban, W.; Rasmussen, J. Co-occurrence of organic and inorganic n influences asparagine uptake and amino acid profiles in white clover. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2021, 184, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Mu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, F.; Lixing, Y.; Mi, G. Interaction effect of nitrogen form and planting density on plant growth and nutrient uptake in maize seedlings. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Niu, S.; Jiang, H.; Luo, B.; Wang, Q.; Han, W.; Liu, Y.; Chang, J.; Ge, Y. Comparing the effects of plant diversity on the nitrogen removal and stability in floating and sand-based constructed wetlands under ammonium/nitrate ratio disturbance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 69354–69366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Lv, J.; Xie, J.; Gan, Y.; Coulter, J.A.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Nitrogen source affects the composition of metabolites in pepper (capsicum annuum l.) And regulates the synthesis of capsaicinoids through the GOGAT–GS pathway. Foods 2020, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Hou, B.; Song, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, W. Preferences of annual and ephemeral plants for inorganic n versus organic n at different growth stages in a temperate desert ecosystem. J. Arid Environ. 2024, 225, 105264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Li, J.; Yu, F.; Dong, Z.; Guo, H. Seasonal nitrogen uptake strategies in a temperate desert ecosystem depends on n form and plant species. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, J.; Liao, J.; Xu, X.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Peng, J.; Niu, S. Plant nitrogen uptake preference and drivers in natural ecosystems at the global scale. New Phytol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, F.Y. Preferences for different nitrogen forms in three dominant plants in a semi-arid grassland under different grazing intensities. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2022, 333, 107959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.; Liu, Y.; Lay-Pruitt, K.S.; Takahashi, H.; von Wirén, N. Auxin-mediated root branching is determined by the form of available nitrogen. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Shi, Y.; Ruan, J. Preferential assimilation of NH4+ over NO3- in tea plant associated with genes involved in nitrogen transportation, utilization and catechins biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2020, 291, 110369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Sheng, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, C.; Zhang, S. Effects of short-term n addition on fine root morphological features and nutrient stoichiometric characteristics of zanthoxylum bungeanum and medicago sativa seedlings in southwest china karst area. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jin, L.; Li, R.; Meng, X.; Jin, N.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lyu, J.; Yu, J. Effects of different forms and proportions of nitrogen on the growth, photosynthetic characteristics, and carbon and nitrogen metabolism in tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryal, K.; Maraseni, T.; Apan, A. How much do we know about trade-offs in ecosystem services? A systematic review of empirical research observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lei, Q.; Liang, X.; Lindsey, S.; Luo, J.; Pei, W.; Du, X.; Wu, S.; An, M.; Qiu, W.; et al. Optimization of the n footprint model and analysis of nitrogen pollution in irrigation areas: a case study of ningxia hui autonomous region, china. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 340, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumwimba, M.N.; Zhu, B.; Muyembe, D.K. Assessing the influence of different plant species in drainage ditches on mitigation of non-point source pollutants (n, p, and sediments) in the purple sichuan basin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Yan, T.; Lei, Q.; Zhang, T.; Fan, B.; Du, X.; Luo, J.; Lindsey, S.; Liu, H. Spatio-temporal variation of net anthropogenic nitrogen inputs (NANI) from 1991 to 2019 and its impacts analysis from parameters in northwest china. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 321, 115996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, X. A source-sink landscape approach to mitigation of agricultural non-point source pollution: validation and application. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 314, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, J.W.; Michael Smart, R. The nutritional ecology of cyperus esculentus, an emergent aquatic plant, grown on different sediments. Aquat. Bot. 1979, 6, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, E.; Mao, X. Distribution pattern simulation of multiple emergent plants in river riparian zones. River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lünsmann, V.; Kappelmeyer, U.; Taubert, A.; Nijenhuis, I.; von Bergen, M.; Heipieper, H.J.; Müller, J.A.; Jehmlich, N. Aerobic toluene degraders in the rhizosphere of a constructed wetland model show diurnal polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4126–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.; Pervez, A.; Khattak, B.N.; Ahmad, R. Constructed wetlands: perspectives of the oxygen released in the rhizosphere of macrophytes. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water 2017, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xu, X.; Wanek, W.; Sun, J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Tian, Y.; Cui, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. Nitrogen availability in soil controls uptake of different nitrogen forms by plants. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 1450–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Gilhooly, W.P.; Jacinthe, P. Nitrogen preference across generations under changing ammonium nitrate ratios. J. Plant Ecol. 2019, 12, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouk, G.; Crawford, N.M.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Tsay, Y. Nitrate signaling: adaptation to fluctuating environments. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 159, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Qiu, Y.; Chai, T.; Chu, C.; Hu, B. Nitrate confers rice adaptation to high ammonium by suppressing its uptake but promoting its assimilation. Mol. Plant. 2023, 16, 1871–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Jin, W.; Hu, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Lu, B.; Li, K.; He, X.; Tang, S. Stable isotope analyses of nitrogen source and preference for ammonium versus nitrate of riparian plants during the plant growing season in taihu lake basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 143029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Huang, B.; Qian, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liao, X.; Song, P.; Li, X. Effects of increased carbon supply on the growth, nitrogen metabolism and photosynthesis of vallisneria natans grown at different temperatures. Wetlands 2020, 40, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hu, Q.; Wei, Y.; Yin, H.; Sun, C.; Liu, G. Uptake kinetics of NH4+, NO3- and H2PO4- by Typha orientalis, Acorus calamus L., Lythrum salicaria L., Sagittaria trifolia L. and Alisma plantago-aquatica Linn. Sustainability 2021, 13, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Q.; Wu, J. Influence of sediment, plants, and microorganisms on nitrogen removal in farmland drainage ditches. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolaki, P.; Mouridsen, M.B.; Nielsen, E.; Olesen, A.; Jensen, S.M.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Baattrup-Pedersen, A.; Sorrell, B.K.; Riis, T. A comparison of nutrient uptake efficiency and growth rate between different macrophyte growth forms. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 274, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, H.M.; Robinson, B.H.; Dickinson, N.M. Plants for nitrogen management in riparian zones: a proposed trait-based framework to select effective species. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2019, 20, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hao, B.; You, Y.; Zou, C.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; Qin, H. Aquatic macrophytes mitigate the conflict between nitrogen removal and nitrous oxide emissions during tailwater treatments. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 370, 122671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xiang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Cheng, M. Stability of c:n:p stoichiometry in the plant–soil continuum along age classes in natural pinus tabuliformis carr. Forests of the eastern loess plateau, china. Forests 2023, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, L.A.; Terai, M.; Tokuchi, N. Nitrate reductase activities in plants from different ecological and taxonomic groups grown in japan. Ecol. Res. 2020, 35, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, H.; HUANG, L. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer application rate on nitrate reductase activity in maize. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2020, 18, 2879–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. Nitrate assimilation pathway in higher plants: critical role in nitrogen signalling and utilization. Plant Sci. Today 2020, 7, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Shen, T.; Xiong, Q.; Zhu, C.; Peng, X.; He, X.; Fu, J.; Ouyang, L.; Bian, J.; Hu, L.; et al. Combined proteomics, metabolomics and physiological analyses of rice growth and grain yield with heavy nitrogen application before and after drought. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, P.; Yue, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, Y. Transcriptomic dissection of allotetraploid rapeseed (brassica napus l.) In responses to nitrate and ammonium regimes and functional analysis ofBnaA2.gln1;4in arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022, 63, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Mas, I.; Rossi, M.T.; Gupta, K.J.; González-Murua, C.; Ratcliffe, R.G.; Estavillo, J.M.; González-Moro, M.B. Tomato roots exhibit in vivo glutamate dehydrogenase aminating capacity in response to excess ammonium supply. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 239, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cao, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K. Grafting enhances the photosynthesis and nitrogen absorption of tomato plants under low-nitrogen stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1714–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, T. Increased rice yield by improving the stay-green traits and related physiological metabolism under long-term warming in cool regions. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2024, 18, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Pou De Crescenzo, M.; Sen; Olivier; Hirel, B. Does lowering glutamine synthetase activity in nodules modify nitrogen metabolism and growth of lotus japonicus? Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 253–262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen use efficiency in crops: lessons from arabidopsis and rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2477–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lian, X. Overexpressed glutamine synthetase gene modifies nitrogen metabolism and abiotic stress responses in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.K.; Carrasco-G, F.E.; Carolina Lizana, X.; Calderini, D.F. Low seed rate in square planting arrangement has neutral or positive effect on grain yield and improves grain nitrogen and phosphorus uptake in wheat. Field Crops Res. 2022, 288, 108699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, X.; Chen, J.; Shang, S.; Zhu, M.; Liang, S.; Zang, Y. Comparative studies on the response of zostera marina leaves and roots to ammonium stress and effects on nitrogen metabolism. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 240, 105965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartigue, J.; Sherman, T.D. Response of enteromorpha sp. (Chlorophyceae) to a nitrate pulse: nitrate uptake, inorganic nitrogen storage and nitrate reductase activity. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 292, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Wu, Q. Physiological characteristics, lint yield, and nitrogen use efficiency of cotton under different nitrogen application rates and waterlogging durations. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 5594–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Beier, M.; Hayashi, M.; Ohmori, Y.; Yano, K.; Teramoto, S.; Kamiya, T.; Fujiwara, T. Growth and nitrate reductase activity are impaired in RiceOsnlp4 mutants supplied with nitrate. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y,; Xie, P.; Tan, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, S.; Qiao, F. A review of the influence of habitat on emergent macrophyte growth and its feedback mechanism. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2021, 40(8): 2610-2619. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liao, D.; Rengel, Z.; Shen, J. Soil–plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere: incremental amplification induced by localized fertilization. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Giehl, R.F.H.; Hartmann, A.; Estevez, J.M.; Bennett, M.J.; von Wirén, N. A spatially concerted epidermal auxin signaling framework steers the root hair foraging response under low nitrogen. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 3926–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Tanaka-Oda, A.; Masumoto, T.; Akatsuki, M.; Makita, N. Different relationships of fine root traits with root ammonium and nitrate uptake rates in conifer forests. J. For. Res. 2023, 28, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Gu, B.; Hong, J. Tracking uptake of submerged macrophytes (ceratophyllum demersum)—derived nitrogen by cattail (typha angustifolia) using nitrogen stable isotope enrichments. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 99, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Lee, Z.; Jeong, E.; Kim, S.; Seo, J.S.; Um, T.; Shim, J.S. Signaling pathways underlying nitrogen transport and metabolism in plants. BMB Rep. 2023, 56, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, Q.; Bai, H.; Zhu, C.; Tang, G.; Zhou, H.; Huang, J.; Song, X.; Wang, J. Interactive effects of aquatic nitrogen and plant biomass on nitrous oxide emission from constructed wetlands. Environ. Res. 2022, 213, 113716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSONE, Y.; TATENO, M. Nitrogen absorption by roots as a cause of interspecific variations in leaf nitrogen concentration and photosynthetic capacity. Funct. Ecol. 2005, 19, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Hu, B.; Li, Y.; Teng, A.; Zhong, F. The effects of polypropylene microplastics on the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from water by acorus calamus, iris tectorum and functional microorganisms. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Zhong, L.; Shen, T.; Cao, C.; He, H.; Chen, X. ITRAQ-based quantitative proteomic and physiological analysis of the response to n deficiency and the compensation effect in rice. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ding, J. Abiotic and biotic determinants of plant diversity in aquatic communities invaded by water hyacinth [eichhorniacrassipes (mart.) Solms]. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 555774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; He, R.; He, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhao, D. Niche-specific restructuring of bacterial communities associated with submerged macrophyte under ammonium stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0071723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Dijkstra, F.A.; Han, X.; Jiang, Y. Root nitrogen reallocation: what makes it matter? Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, R.; Cao, Q.; Quan, Q.; Sun, R.; Liu, J. Effects of emergent aquatic plants on nitrogen transformation processes and related microorganisms in a constructed wetland in northern china. Plant Soil 2019, 443, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Song, S.; Li, C. Effects of nitrogenous nutrition on growth and nitrogen assimilation enzymes of dinoflagellate akashiwo sanguinea. Harmful Algae 2015, 50, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Du, Q.; Li, J. Interactive effects of nitrate-ammonium ratios and temperatures on growth, photosynthesis, and nitrogen metabolism of tomato seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 214, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Sheng, Y.; Yang, S.; Han, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, Z.; Su, Y. Isolation and characterization of a high-affinity ammonium transporter ApAMT1;1 in alligatorweed. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 89, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gao, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, R. Ammonia stress on nitrogen metabolism in tolerant aquatic plant— myriophyllum aquaticum. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 143, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Huangfu, C.; Hui, D. Nitrogen uptake by two plants in response to plant competition as regulated by neighbor density. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 584370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, H. Interspecific competition for inorganic nitrogen between canopy trees and underlayer-planted young trees in subtropical pine plantations. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 494, 119331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Mean square | Df | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | 167945.969 | 3 | 305.340 | <0.001 |

| NH4+/NO3- | 9714.229 | 4 | 17.661 | <0.001 |

| Nitrogen form | 263812.486 | 1 | 479.633 | <0.001 |

| Species × NH4+/NO3- | 3482.750 | 12 | 6.332 | <0.001 |

| Species × Nitrogen form | 19500.487 | 3 | 35.453 | <0.001 |

| NH4+/NO3-×Nitrogen form | 174690.090 | 4 | 317.601 | <0.001 |

| Species×NH4+/NO3-×Nitrogen form | 13835.820 | 12 | 25.155 | <0.001 |

| Error | 550.030 | 80 |

| Number | NH4+/NO3- | NH4Cl (mg L-1) | NaNO3 (mg L-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9:1 | 13.5 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 7:3 | 10.5 | 4.5 |

| 3 | 5:5 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| 4 | 3:7 | 4.5 | 10.5 |

| 5 | 1:9 | 1.5 | 13.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).