1. Introduction

Multidimensional representations have long been central to machine learning and neural network theory for managing complex data structures, yet their relevance to biological cognition has only recently begun to receive focused attention (Eckmann and Tlusty, 2021; Mobbs 2024). Although cognition unfolds within a world constrained by three spatial dimensions and one temporal dimension, emerging developments in topological and geometrical methods suggest that cognitive systems may operate within, or derive significant advantages from, representational frameworks extending beyond the conventional 3D structure plus time (Tozzi 2019; Johnson et al., 2020; Elmer et al., 2023). To provide a few examples, low-dimensional manifolds have been extracted from neural population activity to enable interpretable representations of high-dimensional computations across tasks (Langdon et al., 2023; Gosztolai et al., 2025). Spontaneous and task-related cortical activity was found to be inherently high-dimensional, with behavioral and sensory information represented across orthogonal subspaces (Stringer et al., 2019, 2021). Still, EEG spectral attractors revealed a low-dimensional geometric core underlying resting-state brain dynamics, with alpha and aperiodic bands interacting through cross-parameter geometric coupling (Pourdavood and Jacob, 2023). Orthogonal coding dimensions in vagal sensory neurons were identified, revealing a combinatorial and multidimensional interoceptive architecture (Zhao et al., 2022). In the domain of working memory, high-dimensional population codes were shown to arise from reciprocal communication and feedback between distributed cortical areas (Voitov and Mrsic-Flogel, 2022). Similarly, a four-dimensional convolutional recurrent neural network has been able to integrate frequency, spatial and temporal information from EEG signals, significantly enhancing emotion recognition (Shen et al., 2020).

Overall, these studies underscore the central role of multidimensionality in modelling cognition, revealing how complex patterns of neural activity, behaviour and language may arise from dynamic interactions within high-dimensional representational spaces.

We explore here the idea that some brain computations may be more accurately understood as operations embedded within higher-dimensional spaces. Specifically, we examine a class of topologically based models that simulate synthetic four spatial dimensions using controlled oscillatory patterns in two-dimensional lattice-like systems. Inspired by quantum-adjacent constructs like topological charge pumps and phase-dependent oscillatory systems, these non-quantum models can capture features of higher-dimensional dynamics. We aim to investigate how higher-dimensional computational frameworks intersect with established neural mechanisms, pinpoint their potential correlates within low-dimensional neural substrates and design experimental approaches to test their plausibility as models of cognitive function.

2. Theoretical Background: Simulating 4D Dynamics in 2D Oscillatory Systems

We outline here the theoretical pillars to support our suggestion that cognitive processes can be embedded in, or benefit from, higher-dimensional computational frameworks. Traditional cognitive and neural models typically operate within three spatial dimensions, occasionally extending to include time or abstract “feature spaces” as additional dimensions. Yet, computational neuroscience is increasingly embracing higher-dimensional models to more accurately neural population activity, suggesting that the brain may structure information in ways that go beyond physical spatial constraints. Understanding cognition within this expanded dimensional framework necessitates the integration of perspectives from neuroscience, dynamical systems theory and computational modelling. Although advanced techniques like principal component analysis, manifold learning and dynamical systems approaches have uncovered low-dimensional trajectories within high-dimensional neural data, these remail just statistical tools designed for analytical purposes (Klumpp et al., 2018; Shinn, 2023; O'Dell et al., 2023; Chellini et al., 2024; Hope et al., 2024). Our model seeks to bridge high-dimensional structure with physical computation, focusing on oscillatory and spatially organized systems as biologically plausible substrates.

Topological lattices and high-dimensional dynamics in quantum systems. In condensed matter physics and photonics, the concept of multidimensional traces arises from the idea that lower-dimensional physical substrates in 2D or 3D can exhibit physical responses governed by the topological properties of a theoretical 4D space. A prominent example is the topological charge pump realized in quantum 2D lattices, where deliberate modulation of oscillatory parameters like phase shifts and coupling strengths induces behaviour consistent with that of four-dimensional systems (Lohse et al., 2018). These effects are linked to the physics of the two-dimensional quantum Hall effect, in which electrons subjected to a strong magnetic field exhibit quantized Hall conductance governed by topological invariants known as Chern numbers (Ge et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2020; Li et al. 2023). Theoretical 4D extensions predict that analogous phenomena characterized by a second Chern number may generate nonlinear responses like topological pumping and protected edge-state propagation (Zilberberg et al., 2018). These lattices are composed of arrays of nodes, each functioning as an oscillatory unit encoding local signals. The interactions among these nodes are governed by interference patterns generated by overlapping oscillatory fields. When two orthogonal waves with differing frequencies and wavelengths interact, they form a superlattice, i.e., a periodic structure encoding information across spatial scales. Overlapping waveforms with distinct phase, frequency and direction may produce emergent patterns not explicitly hardwired into the system, but arising from constructive and destructive interference.

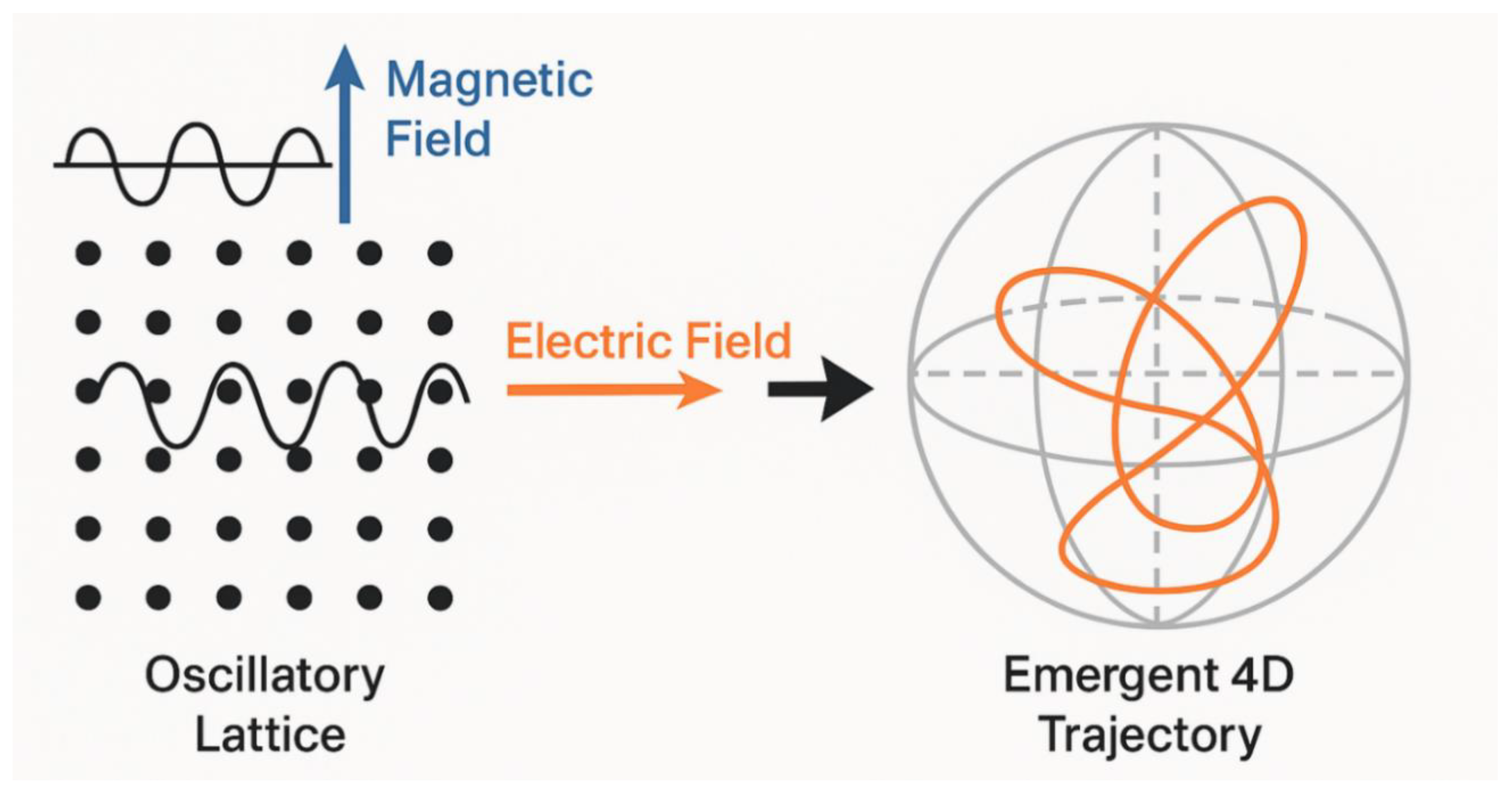

Introducing a third wave or modulating the phase of an existing wave across the lattice alters the interference patterns and produces curved, helical trajectories extending beyond the native two-dimensional geometry. These trajectories can be mapped onto higher-dimensional phase spaces, effectively simulating synthetic dimensional expansion (

Figure 1). Though true physical 4D space remains experimentally inaccessible, these synthetic dimensions enable experimental platforms like ultracold atomic systems and photonic lattices to explore higher-dimensional topological physics. Dimensionality does not represent an intrinsic property of physical space but rather emerges from the interactions among variables such as phase, frequency and spatial configuration across the lattice, effectively simulating movement through a higher-dimensional space.

Overall, by precisely controlling oscillatory inputs, particularly phase, amplitude and angular orientation along orthogonal axes in the 2D array, it becomes possible to generate paths within a four-dimensional parameter space. In the sequel, we suggest that these engineered models may provide not only a proof of concept for synthetic dimensionality, but also a theoretical bridge to understanding how biological neural architectures might exploit similar principles to support high-dimensional cognitive computation.

Extending the framework to non-quantum, biological computation. The topological effects described above are not exclusive to quantum systems, as similar phenomena can also emerge in classical systems that support wave propagation and structured interference patterns (Price et al., 2015; Ozawa et al., 2019). By coupling oscillatory parameters across space and phase, these classical systems can effectively encode additional synthetic dimensions via edge-state propagation, quantized transport or nonlinear transitions (Yuan et al., 2018). For instance, photonic crystals can use light waves to simulate topological band structures (Lu et al., 2014), while mechanical metamaterials can replicate corner modes through engineered lattice geometries (Huber, 2016). Similarly, electric circuit networks have been shown to simulate synthetic dimensions via frequency modulation and circuit topology (Imhof et al., 2018). A particularly illustrative example is offered by Wang et al. (2023), who employed resonant pillars with spatially varying coupling to simulate an extra synthetic dimension and achieve topological pumping of elastic surface waves. Their model draws an analogy between classical wave dynamics and electron behaviour in magnetic fields, demonstrating robust, disorder-resistant propagation which is a hallmark of higher-dimensional topological systems.

The same principles governing synthetic dimensions in physical systems may be conceptually extended to model complex information processing in biological neural systems (Tozzi et al., 2021). Just as topological systems encode additional dimensions without enlarging physical space, the brain may, without added anatomical complexity, achieve higher-dimensional computation through rhythmic activity and phase interactions across neural populations.

In sum, treating neural tissue as a dynamic medium for phase-dependent oscillatory activity provides a framework for understanding how synthetic dimensions could emerge within the central nervous system. The remainder of this review examines mathematical frameworks, candidate brain structures and dynamic mechanisms consistent with higher-dimensional simulation and outlines potential experimental approaches for their investigation.

3. Mathematical Formalism for Synthetic High-Dimensionality

This section outlines a simplified mathematical framework for our approach to higher-dimensional neural activity. It focuses on the theoretical configuration of a two-dimensional oscillatory system as a substrate for simulating four-dimensional computation.

Lattice construction and geometric formalism. Let

denote

a two-dimensional spatial lattice abstracted as a discrete manifold embedded in

a Euclidean plane. The lattice comprises nodes indexed by

, where

and

denotes the number of units along each axis. Each node represents a spatial location capable of sustaining oscillatory activity. Define a scalar field

, where

describes the instantaneous state of the oscillatory unit at site

and time

.

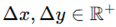

Continuous spatial embedding can be imposed by associating each index pair

with a spatial position vector

, where

,

and

denote the lattice spacing

constants along the respective dimensions. This yields a spatially indexed

field

over a discretized, regular domain. The topology is flat, with periodic or fixed boundary conditions applicable depending on further dynamical considerations.

This formulation defines the geometric substrate upon which temporal dynamics are introduced, enabling analytical treatment of oscillatory field properties across spatial configurations.

Temporal oscillation and local harmonic dynamics. Each node is associated with a temporal signal modeled as a harmonic oscillator. Define the local temporal signal as:

,

where

denotes the amplitude,

the angular frequency and

the phase offset. The set

and

may be constant across the lattice or vary systematically to encode gradients, localized perturbations or wavefront propagation. Time t is treated as a continuous variable and the oscillators are considered decoupled at this stage, evolving independently.

In more generalized models, amplitude and frequency may be treated as functions of spatial location and time, and , allowing modulation by external inputs or internal feedback mechanisms.

This layer of temporal modeling establishes a field of time-varying signals across the lattice, enabling future interaction terms to produce emergent multidimensional patterns.

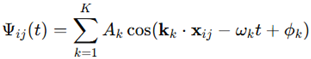

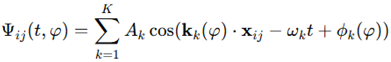

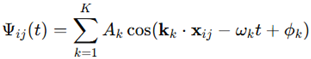

Superposition and interference structures. To introduce structured dynamics capable of emulating higher-dimensional behavior, oscillatory inputs are modeled as superpositions of multiple standing waves across the lattice domain. Consider the aggregate signal at point as:

,

where

is the number of wave components,

their amplitudes,

their angular frequencies,

phase offsets and

are wave vectors defining

propagation direction and spatial frequency. Each term represents a planar wave

propagating through the lattice, contributing to the overall spatiotemporal

dynamics of the system. The interference among these components yields a

superlattice, i.e., a spatially and temporally modulated structure with regions

of constructive and destructive interference.

Wave vectors can be orthogonal, aligned or angled depending on the desired interference pattern. Particularly, if two or more waves display incommensurate wavelengths or non-parallel directions, the resulting interference can form quasi-periodic structures with no translational symmetry, mimicking higher-dimensional topologies.

This formulation provides a flexible mechanism for generating non-quantum, multidimensional patterns through the composition of linear oscillatory components.

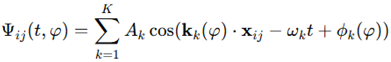

Phase modulation as synthetic dimensionality. Synthetic

dimensionality is introduced by allowing the parameters of wave components to

vary in time or as a function of lattice coordinates. Specifically, one

introduces a pump parameter

which modulates either the

phase or spatial frequency of the propagating waves. For example, a

phase-modulated topological pump may be defined as:

,

where kk(φ) and ϕk (φ) are smooth functions of the pump parameter. The parameter may itself vary slowly with time, e.g., , causing the system to traverse a closed trajectory in its parameter space. This modulation introduces a geometric phase, potentially leading to nonlinear or even quantized responses that emerge orthogonally to the direction of modulation. These pump cycles emulate motion through an abstract fourth spatial dimension, with interference patterns encoding projection-dependent distortions and dynamic transitions within high-dimensional feature space.

The formalism of phase modulation expands the system’s descriptive space and provides the mathematical route to synthetic dimensionality without invoking actual four-dimensional physical geometry.

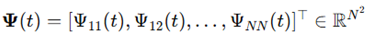

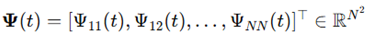

Geometric characterization via embedding and trajectory analysis. To assess the dimensional properties of the evolving field , one may represent its global configuration as a trajectory in a high-dimensional state space. Define a configuration vector at time t as:

.

This vector evolves continuously over time and may trace a path

. If the temporal evolution

exhibits low-dimensional structure, this trajectory lies on a manifold

of dimension

. Dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) or diffusion maps can be used to characterize the manifold M, yielding eigenvalues

corresponding to dominant modes of variance.

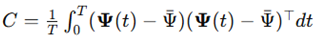

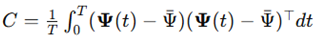

Given a covariance matrix

, the eigenvalue spectrum

quantifies the system’s effective embedding dimensionality. A steep decay

suggests a low-dimensional manifold, while a flat spectrum implies higher-dimensional complexity.

This trajectory-based analysis enables rigorous identification of synthetic dimensionality from the field’s global evolution.

Overall, this section has presented a formal mathematical framework for understanding how a two-dimensional lattice of oscillatory signals can simulate behavior consistent with four-dimensional computational dynamics.

4. Neural Correlates of Higher-Dimensional Computation

If brain dynamics can simulate higher-dimensional computations through phase-based oscillatory systems as proposed above, it becomes crucial to identify plausible neurobiological substrates embedded within the brain’s inherently low-dimensional physical architecture. In the following paragraphs, we explore a range of empirical and theoretical findings suggesting that core aspects of cognition, especially those requiring flexible integration, may unfold within a higher-dimensional computational space achieved by the coordinated dynamics of neural oscillations.

Oscillations on a 2D lattice. Our first requirement is a lattice-like structure within the central nervous system capable of supporting oscillations oriented along distinct spatial axes. The cortex, often conceptualized as a folded sheet, may provide a plausible spatial substrate for the propagation of these oscillatory waves. This perspective is supported by the occurrence of large-scale spatiotemporal cortical patterns like traveling waves, rotating motifs and spatially organized phase fields, particularly in sensory and motor areas, where these patterns can span tens of millimetres and dynamically reconfigure in response to changing cognitive contexts (Foldes et al., 2021; von Wegner et al., 2021; Myrov et al., 2024). In line with this framework, Clusella et al. (2023) explored how complex spatiotemporal oscillations emerge from transverse instabilities in large-scale brain network models. Using a system of 90 interconnected regions with structure derived from tractography data, the authors identified conditions under which synchronized states lose stability and produce high-dimensional patterns and traveling waves. This model may also apply to cerebellar computations in line with vector-based null space theory. Specifically, Purkinje cell activity has been shown to influence behaviour only when aligned with a potent movement vector, while components orthogonal to that direction cancel out through mutual interference (Fakharian et al., 2025). Additionally, hippocampal neurons, particularly those in the medial entorhinal cortex, exhibit orthogonal spatial organization that supports the integration of spatial navigation and memory processes (Sasaki et al., 2015). Together, these findings point to the presence of direction-sensitive interactions embedded within distinct types of biological neural lattices.

Simulating dynamics in higher-dimensional spaces. A further requirement is that the nervous lattice must be capable of representing or simulating dynamics that unfold in higher-dimensional spaces. We hypothesize that the cortex actively generates or simulates high-dimensional computations through mechanisms like phase alignment, phase competition or spatial interference. Indeed, a growing body of research advocates that spatial interference patterns in brain oscillations may serve as computational mechanisms. Effenberger et al. (2025) showed that recurrent networks composed of harmonic oscillators generating interference patterns significantly outperform non-oscillatory models in terms of learning efficiency and robustness. This suggests that wave-based interference can encode spatial and temporal relationships among stimulus features. Similarly, Burgess (2008) developed an oscillatory interference model for grid cells, wherein phase differences among velocity-controlled oscillators encode spatial positions through interference, providing a potential model of high-dimensional spatial coding. Esmaeilpour et al. (2021) investigated the use of temporal interference as a method for non-invasive deep brain stimulation, demonstrating that selective modulation of gamma oscillations can be achieved using amplitude-modulated kilohertz electric fields.

Cross-frequency coupling stands for another compelling mechanism potentially underlying synthetic high-dimensionality. Well-documented interactions between frequencies, such as theta-gamma coupling, support information transfer and flexible signal routing in neural networks (Brooks et al., 2020; Rustamov et al., 2022; Ursino and Pirazzini, 2024). It has been shown that selective attention in visual tasks elicits frequency-specific activity across multiple brain regions, with interference-like modulation in the alpha and theta bands reflecting underlying cognitive control processes (Son et al., 2023). In both the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, low-frequency oscillations (e.g., theta) have been found to modulate the amplitude or phase of higher-frequency rhythms (e.g., gamma), shaping temporal coordination across networks (Tamura et al., 2017). Cross-frequency interactions can induce phase shifts in low-frequency rhythms, which in turn modulate the amplitude or timing of higher-frequency components. Overall, Beste et al. (2023) proposed a theoretical framework that systematizes the role of oscillations in cognitive control, arguing that cross-frequency interactions could represent multidimensional functional states. This dynamic modulation may effectively reposition the nervous activity within a higher-dimensional phase space, where phase-shifted oscillations govern the routing of neural information flow.

High-dimensional population coding. Another key requirement is that the phase space trajectories of neural population activity must be capable of encoding more degrees of freedom than the physical space in which the system is embedded. This idea is supported by findings in neural population coding which show that large-scale, coordinated cortical activity often cannot be reduced to low-dimensional representations without sacrificing essential informational content (Montijn et al., 2016; Kristensen et al., 2024; Posani et al., 2024). Neural trajectories during working memory tasks have been shown to traverse low-dimensional, nonlinear attractors interpretable as compressed higher-dimensional paths (Singh and Eliasmith 2006; Murray et al. 2016; Cueva et al. 2020). Klukas et al. (2020) developed a model in which grid cells flexibly encoded high-dimensional variables by combining low-dimensional modules through mixed modular coding. Still, Nieh et al. (2021) argued that hippocampal representations of physical and abstract learned variables resided within low-dimensional manifolds consistent across animals. Experimental and modelling evidence supports the idea that computations are embedded in the geometry of population trajectories, often constrained to manifolds of low intrinsic dimensionality despite being embedded in high-dimensional neural space (Gallego et al. 2017; Jazayeri and Ostojic 2021). Voitov and Mrsic-Flogel (2022) demonstrated that working memory is maintained through high-dimensional representations distributed across reciprocally connected cortical areas, supporting the view that cognitive states emerge from coordinated, non-local population dynamics rather than from low-dimensional trajectories alone.

Altogether, cognitive operations may emerge from structured patterns of activity evolving along low-dimensional manifolds embedded within the brain’s high-dimensional neural space.

Context-sensitive cognitive processes. Synaptic transitions can be driven solely by phase perturbations without requiring changes in synaptic connectivity (Kwag and Paulsen 2009). In line with this hypothesis, higher-dimensional signals may be modulated by external inputs or internal rhythms, enabling flexible functional shifts without structural rewiring. Recent experimental findings support this perspective, showing that the same neural ensemble can switch between distinct functions such as memory recall and error correction through modulation of internal state alone (Jazayeri and Ostojic 2021). This flexibility suggests that cortical dynamics may unfold within a high-dimensional latent space shaped by contextual phase variables.

This framework naturally extends to sensory integration across visual, auditory and somatosensory cortices, where object features like shape, orientation and motion are encoded through population coding and hierarchical processing. In the ventral visual stream, early areas like V1 represent basic features while downstream regions such as V4 and IT integrate these into abstract representations of object identity (Roth and Rust 2019). This hierarchical feature synthesis mirrors the “shape injection” and multistage encoding mechanisms described by our lattice model (Lohse et al. 2018).

As neural trajectories evolve within this high-dimensional space, they may encode complex information such as geometric transformations or feature conjunctions that exceed the representational limits of three-dimensional frameworks. In neural terms, this reflects the brain’s ability to bind multiple sensory features, e.g., shape, orientation and texture, into coherent percepts through distributed oscillatory activity (Balta and Akyürek 2024). The dynamic coordination of oscillations across neural regions may thus provide a mechanism for generating higher-dimensional representations from simpler components. This could help explain perceptual and cognitive phenomena that are difficult to model using conventional low-dimensional approaches. For instance, perceptual stability during ambiguous or multistable stimuli, like binocular rivalry, may involve transitions across nonlinear manifolds requiring higher-dimensional embedding (Furstenau 2003; Murthy 2018). Similarly, cognitive control signals that adjust task rules or initiate strategy shifts may function as modulators of synthetic dimensions, allowing the brain to access new computational states without altering structural connectivity.

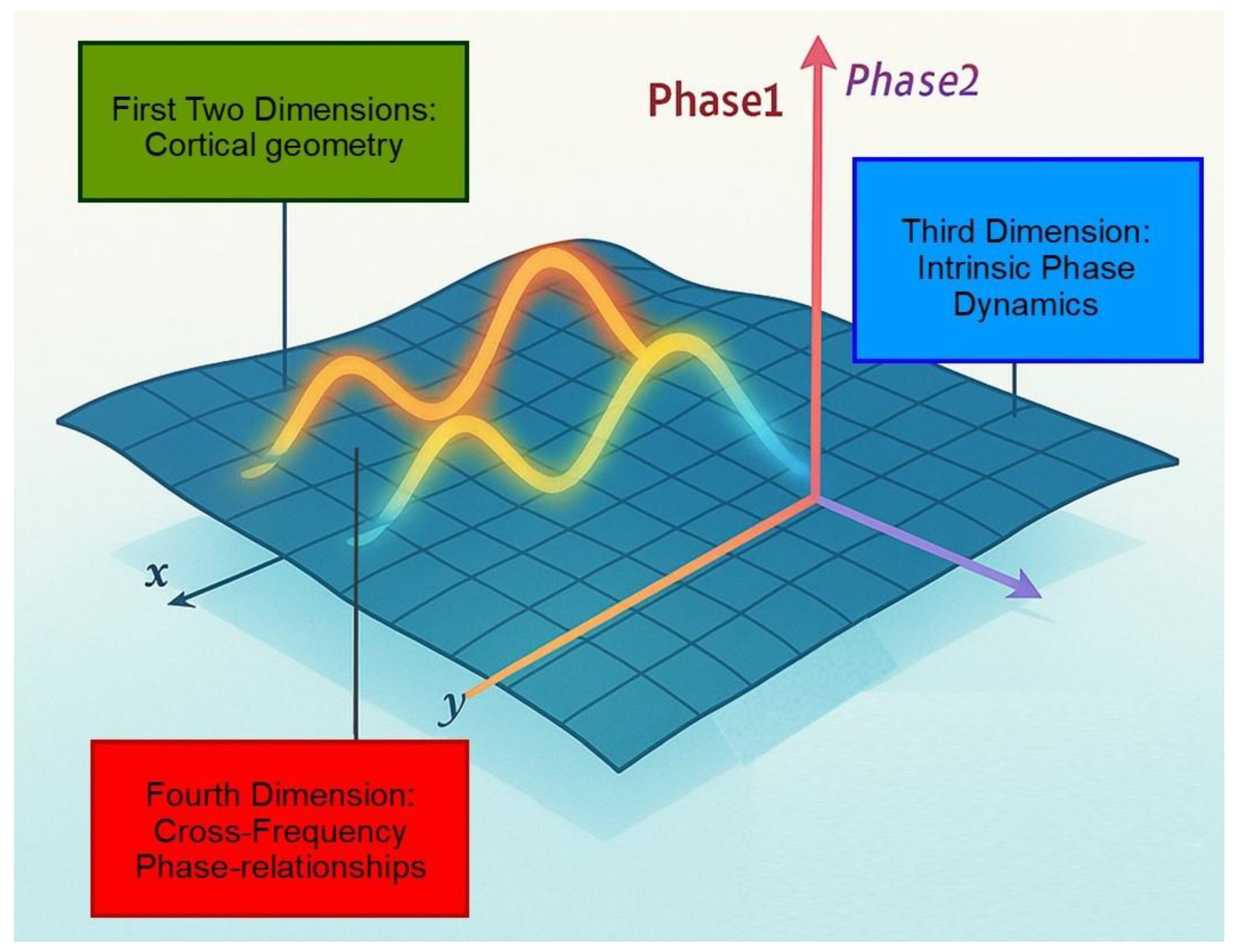

Example: A 2D cortical sheet performing 4D phase-space computations. We present a theoretical example of how high-dimensional computation might be implemented within the cortical milieu at a middle-grained resolution, i.e., beyond the scale of individual neurons but finer than large-scale brain regions. The anatomical substrate is the cerebral cortex, i.e., a highly folded sheet composed of spatially organized neuronal columns. This biological lattice may support traveling waves, oscillatory interference patterns and large-scale phase coupling across its surface.

First two dimensions: the x–y coordinates of the cortical sheet define a two-dimensional spatial domain over which phase-locked oscillations (e.g., alpha or theta traveling waves) propagate.

Third dimension: intrinsic oscillatory phase dynamics like phase-amplitude coupling allow slow rhythms (e.g., theta) to modulate the amplitude or timing of faster rhythms (e.g., gamma), encoding temporal trajectories of computation.

Fourth dimension: cross-frequency phase relationships across spatially distinct cortical regions encode abstract, non-spatial variables such as task rules, contextual signals or memory bindings. These relationships evolve dynamically over time, reflecting internal cognitive states.

that enables dynamic information binding and routing across large-scale cortical networks.

Functional implications:

Our model navigates a four-dimensional phase space defined by space , enabling it to:

Represent multiple overlapping cognitive variables simultaneously.

Bind content across modalities, including memory, attention and perception.

Transition smoothly between distinct representational states without requiring structural rewiring.

Extend dynamic computations across large cortical territories, linking distant regions through coherent phase relationships.

This model explains how the cortex can use its spatial architecture and oscillatory dynamics to carry out functionally high-dimensional computations within a physically three-dimensional structure.

Taken together, evidence from cortical architecture, oscillatory dynamics, cross-frequency coupling and population-level coding converges on a view of the brain as a low-dimensional physical substrate supporting high-dimensional computation. This suggests that the cortex may compute not solely through synaptic interactions, but also through wavefronts that dynamically shape the geometry of neural activity. In this framework, the neural code is no longer defined just by static, pointwise firing rates, but also by evolving phase trajectories, where information is distributed across synthetic dimensions formed by interference patterns.

5. Comparative Perspectives

The idea that the brain performs computations within topologically structured, synthetic higher-dimensional spaces invites comparison with other leading theories of cognition and consciousness. This chapter explores how our framework aligns with, or diverges from, classical neural models and recent integrative theories.

Classical and neural network models. Traditional neural network models, both feedforward and recurrent, operate in high-dimensional vector spaces where units update their activations based on weighted connections. However, they typically treat spatial structure as incidental or abstract. For example, in multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks, spatial information is introduced only through input formatting or weight sharing, while internal representations remain disconnected from any explicit topological or phase-based geometry (Vakalopoulou et al. 2023; Halužan Vasle and Moškon 2024; Lin et al. 2024). Still, the Hopfield network stores patterns as attractor states in an energy landscape. While it can retrieve stored patterns from partial inputs through deterministic convergence, it lacks spatial and temporal structure beyond its static connectivity matrix, not reflecting the rhythmic or context-sensitive dynamics of the cortical activity (Alonso and Krichmar 2024; Wang and Wyble 2024). Similarly, reservoir computing and echo state networks introduce temporal processing through recurrent feedback, but they abstract away from the biophysical mechanisms of spatial signal propagation observed in the brain (Lymburn et al. 2019; Tanaka et al. 2019; Aceituno et al. 2020). Although these architectures have powered major advances in learning, classification and memory retrieval, they fall short in modeling the fine-grained temporal dynamics, the phase alignment across brain regions and the flexibility of neural representations under changing task demands.

In contrast, our model treats space, time and phase as core computational substrates. Rather than relying solely on static connections, it employs structured oscillatory systems in which units or regions interact through phase-coupled dynamics. This allows for the simulation of higher-dimensional computation without altering the underlying anatomical wiring. The same substrate can support multiple, context-sensitive computational states, unlike classical networks that must reconfigure weights or activate separate modules to switch tasks.

Our model differs from both classical vector-based systems and static neural graphs. It evolves through dynamic wave interactions, producing emergent behaviors that are computationally powerful yet energetically efficient. Compared to quantum computing frameworks, which also aim to expand representational capacity through multidimensional spaces, our model is entirely non-quantum. It avoids the theoretical fragility and hardware challenges associated with quantum coherence and entanglement, making it more biologically grounded and practically viable without relying on speculative mechanisms.

In summary, while classical and artificial neural networks excel in constrained tasks, our framework provides an alternative to capture the flexibility of neural computation without increasing anatomical complexity or relying on arbitrary modularization.

Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and Global Workspace Theory (GWT). Our model shares conceptual ground with both IIT and GNWT, yet it also offers key distinctions. IIT proposes that consciousness arises from the generation of highly integrated and differentiated information quantified by the measure of information Φ (Mallatt et al., 2021; Mediano et al., 2022). IIT conceptually aligns with our framework in several ways. The emergent behaviour of a 2D oscillatory lattice simulating 4D dynamics suggests non-trivial integration that may support high Φ values. Moreover, our modulation of phase relationships across distributed nodes grants a plausible physical substrate for the unified, irreducible informational structures described by IIT.

GNWT views consciousness as the result of information becoming globally available through a workspace that broadcasts selected content across the brain, involving coordinated activity among distant cortical and subcortical regions, often synchronized by oscillatory dynamics (Mashour et al., 2020; Farisco and Changeux, 2023). Our model complements GNWT by proposing phase modulation as a gating mechanism that regulates access to global information flow and by capturing nonlinear transitions where local signals become globally distributed. Additionally, our synthetic dimensionality provides a flexible computational scaffold for integrating and routing the diverse information streams described by GNWT.

Recent groundbreaking findings by Ferrante et al. (2025) provide empirical support for our multidimensional framework while challenging core assumptions of both IIT and GNWT. Notably, the absence of sustained posterior synchronization and the limited evidence for prefrontal “ignition” contradict central predictions of both models. Instead, Ferrante et al. demonstrate that the conscious content does not arise from fixed anatomical hubs, but rather emerges from distributed, temporally coordinated activity across cortical regions. Specifically, content-specific synchronization is reported between early visual and frontal areas along with duration-sensitive responses in the occipital and lateral temporal cortices, supporting the view of consciousness as a process unfolding across neural manifolds within a high-dimensional computational space.

These observations suggest that conscious access may depend more on functional topologies and dynamic state transitions than on static integration or global broadcasting. This interpretation supports our view that consciousness arises from phase-aligned, population-level geometries that enable high-dimensional operations within a physically low-dimensional neural substrate.

In sum, rather than replacing existing cognitive theories, our model may function as a complementary computational infrastructure underlying them. It provides a biophysically plausible mechanism for generating high-dimensional states, a means of reconciling local processing with global integration through phase-driven lattice dynamics and an explanation for how content-specific operations can emerge from oscillatory interference.

6. Bridging Theory and Data: Experimental Predictions and Opportunities

Our theoretical framework suggests specific, testable predictions about brain function. These predictions span electrophysiological, behavioral and computational domains and can be evaluated using currently available experimental techniques.

Signatures of higher-dimensional embedding in brain dynamics. A central prediction is that specific patterns of brain activity, particularly those elicited during complex perceptual or cognitive tasks, will display signatures indicative of nonlinear dynamics in higher-dimensional state spaces. These signatures may include curved or twisted trajectories in reconstructed phase space that cannot be fully explained by conventional three-dimensional projections, as well as abrupt transitions between attractor states during processes like perceptual switching, decision-making or memory retrieval. The emergence of closed manifolds, topological loops or toroidal structures in neural population dynamics would further suggest that cognitive processes are embedded in high-dimensional topologies.

Testing these predictions requires analytical approaches capable of capturing both the geometric configuration and topological structure of neural activity patterns. Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis, t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection provide powerful tools for extracting low-dimensional trajectories from high-dimensional neural datasets (Carracedo-Reboredo et al., 2021; Parmar et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2022; Alalayah et al., 2023; Dogra et al., 2023; Mitchell-Heggs et al., 2023; Zhu and Wang, 2024). These methods facilitate the visualization of how large neural populations co-evolve over time, revealing features such as attractor-like dynamics, task-dependent manifolds and transitions between cognitive states. However, while these approaches effectively capture geometric relationships inside the data, they may overlook deeper topological features, like loops, voids or branching structures, that potentially represent functionally relevant relationships.

Among these, persistent homology is particularly powerful, as it enables the quantification of cycles, holes and voids within neural activity space across multiple spatial and temporal scales. These topological invariants stand for robust, scale-independent descriptors serving as stable markers of specific cognitive states or transitions. Empirical testing of our theoretical predictions can be also pursued by constructing state-space reconstructions from multichannel neural recordings, including electroencephalography, magnetoencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging. By embedding time-series data into higher-dimensional representations, researchers can reconstruct the trajectory of brain states as they evolve in time, possibly uncovering non-Euclidean geometries indicative of underlying cognitive processes.

Still, these analyses can be enriched through the application of graph-theoretic metrics and dynamic models of functional connectivity to assess how the coordination between brain regions changes over time. Also, perturbation-based techniques like controlled modulation of phase or amplitude in specific frequency bands may allow for causal testing of how brain networks reconfigure in response to targeted disruptions.

Phase modulation treated as a control variable. If the brain leverages oscillatory phase relationships to produce transitions across higher-dimensional cognitive spaces, then externally modulating these phase dynamics could provide a direct means of influencing cognitive states. Phase may not be merely a byproduct of neural activity but may function as an active control variable capable of gating information flow, reorganizing network topology and shifting the system between functional regimes.

One promising avenue for testing this hypothesis involves transcranial alternating current stimulation, which can entrain neural oscillations at specific frequency bands. By targeting phase relationships rather than simply amplitude, researchers could investigate how deliberate shifts in phase alignment across cortical regions alter cognitive outcomes. We predict that phase-synchronized stimulation in theta or alpha bands might enhance memory encoding or attentional control, while desynchronization could impair task performance or induce perceptual ambiguity.

Additionally, closed-loop neurostimulation provides a powerful method for testing the role of phase dynamics in real time. By continuously monitoring ongoing neural activity and adaptively adjusting stimulation parameters to modulate features such as theta-gamma coupling or cross-frequency phase coherence, researchers could probe the causal relationships between phase interactions and behaviour. These interventions could be timed to coincide with critical cognitive events like decision boundaries, perceptual transitions or moments of memory retrieval, thereby enabling direct investigation of how dynamic phase relationships shape cognitive processing. Behaviorally, these manipulations could be expected to influence a range of phenomena, from bistable perception to reaction times and error rates in decision-making tasks.

Efficiency through dimensional compression. Our framework predicts that high-dimensional representations may allow the brain to encode richer information content without increasing its anatomical footprint. By leveraging higher-order oscillatory dynamics, the brain could compress complex cognitive content into compact, efficient codes. This implies that localized cortical regions, rather than expanding in size or recruiting additional neurons, can represent a greater number of features, categories or task-relevant variables within fixed anatomical constraints.

Specifically, cortical areas exhibiting complex phase relationships or elevated cross-frequency coupling (CFC) are predicted to have enhanced encoding capacity. A small cortical patch with strong theta-gamma coupling, for example, may simultaneously represent multiple stimulus dimensions, categories or decision variables. We suggest that the temporal structuring provided by nested oscillations might allow overlapping representations to coexist with minimal interference. Furthermore, under conditions that promote phase synchrony across distributed regions, neural systems might achieve more coherent and efficient information integration, supporting improved classification accuracy and faster task performance.

These predictions can be tested using high-resolution neural data and decoding analyses. High-density EEG and electrocorticography provide the temporal and spatial granularity needed to assess how information encoding varies with phase complexity (Vakani and Nair 2019; Li et al. 2022; Castelnovo et al. 2022; Branco et al. 2023; Meiser et al. 2024). Researchers could compare multifeature classification accuracy under different oscillatory regimes or examine how variations in CFC relate to representational dimensionality. Task-based fMRI could further assess how the informational richness of cortical activity changes with increasing task complexity and phase coordination.

Oscillatory correlates of cognitive transitions. Our multidimensional framework predicts that transitions between cognitive states like perceptual shifts, working memory updates or task-switching, are driven by rapid nonlinear reorganization of oscillatory phase relationships across neural networks (Fingelkurts and Fingelkurts, 2022). Coordinated phase realignments may reflect topological reconfigurations within a high-dimensional cognitive space where functional connectivity is temporarily reshaped.

These phenomena can be empirically investigated using magnetoencephalography and other time-resolved neural recording techniques. For instance, time-frequency analyses during bistable perception tasks such as ambiguous figure interpretation might reveal the timing and frequency-specific shifts associated with perceptual transitions. Similarly, tasks involving attentional reorienting or rule switching could be used to assess cross-regional phase-locking patterns, examining how distant cortical areas temporarily align during moments of cognitive reconfiguration. Sudden redirection or bifurcation in neural activity’s trajectories would support our model’s prediction that cognitive transitions are governed by topological realignment rather than local, incremental changes.

In summary, our framework may provide an empirically accessible bridge between abstract higher-dimensional computation and measurable neural dynamics. The use of topological, oscillatory and phase-based mechanisms opens a range of possibilities for experimental neuroscience to test whether the brain truly simulates aspects of 4D computation.

7. Conclusions

We explored a model in which a 4D computation is simulated through oscillatory dynamics distributed across 2D neural substrates. This approach aligns with the concept of synthetic dimensions in physics, where systems confined to lower-dimensional structures exhibit emergent higher-dimensional behaviour via interference and temporal coordination. Drawing inspiration from topological charge pumps and phase-modulated lattice systems in physics, we examined how comparable mechanisms might be implemented in the neural tissue. By aligning the behaviour of these synthetic systems with established neurophysiological features like cortical oscillations and cross-frequency coupling, we suggest that aspects of cognition may unfold within topologically rich spaces extending beyond conventional 3D interpretations. In contrast to models focusing solely on connectivity, our framework emphasizes spatial interference and phase geometry as functional dimensions of neural computation. Further, our model introduces specific candidate mechanisms, namely, phase-modulated lattice dynamics. In this view, the neural code cannot be fully captured by spike trains or static firing rate distributions alone; instead, it must be interpreted through geometric and dynamical descriptors such as curvature and rotation number. In both quantum and classical systems, it is topological invariance, rather than quantumness, that underlies these effects without requiring increases in the system’s physical dimensionality.

From an experimental perspective, several testable hypotheses emerge: a) cross-frequency phase modulation enables higher-dimensional embedding of neural states; b) cortical regions exhibit attractor transitions consistent with 4D topologies; c) phase-structured stimuli can modulate perceptual outcomes by exploiting synthetic dimensionality.

Our model carries several limitations. First, it has yet to be validated by direct experimental evidence. No known cortical system has been shown to explicitly simulate a fourth spatial dimension and the interpretation of phase modulation as a proxy for higher-dimensional projection remains speculative. Our framework is inherently abstract: although it proposes plausible neural correlates, it does not yet provide a fully quantitative model amenable to detailed simulation or accurate neurophysiological testing. Moreover, the model’s reliance on oscillatory interference as a primary mechanism may oversimplify the assortment of neuronal dynamics that embraces complex interplay between excitatory and inhibitory populations, neuromodulatory influences and stochastic fluctuations. While phase relationships can modulate computation, many other factors must be taken into account, including synaptic plasticity, firing variability and network heterogeneity. Furthermore, our framework draws on topological constructs such as synthetic manifolds, phase curvature and multidimensional trajectories that are challenging to measure in empirical neural data. Current recording and analysis techniques may lack the spatial or temporal resolution necessary to fully resolve these issues, raising questions about the tractability of experimental validation. Finally, our model does not provide explicit predictions about learning, development or adaptation, nor does it incorporate task-dependent plasticity or long-range developmental constraints. As such, our approach should be seen as a hypothesis-generating framework rather than a fully realized computational model.

Despite these limitations, our framework provides ground for generating novel hypotheses and guiding new lines of investigation. One promising avenue lies in cognitive modeling, particularly in domains involving complex integration over time and space like perception, multisensory integration, working memory and episodic encoding. By incorporating phase-based dynamics and high-dimensional representations, our approach may provide new explanatory tools for understanding how the brain flexibly binds information across modalities and contexts. Still, our model has potential implications for neuromorphic computing, where brain-inspired physical architectures could benefit from phase-based logic, spatial interference and synthetic dimensionality. Artificial systems might exploit dynamic phase relations to reconfigure computational states without requiring structural rewiring, mirroring the flexibility observed in biological systems. Moreover, our framework resonates with developments in artificial intelligence, particularly in deep learning and manifold learning, where models routinely operate in high-dimensional spaces to encode complex patterns and support generalization. Drawing parallels between cortical dynamics and machine learning architectures could lead to cross-fertilization between neuroscience and AI, inspiring biologically informed evaluation metrics. Overall, our framework invites dialogue with theoretical physics, dynamical systems theory, AI and topological data analysis, opening an interdisciplinary path toward a more integrated research agenda.

In addressing the central question, i.e., whether cognition might exploit topological structures to simulate higher-dimensional computation, we conclude that our model is both theoretically plausible and biologically grounded. Our main contribution lies in the model’s capacity to reinterpret cortical oscillations not merely as signals but as the medium through which multidimensional information processing occurs. As a final remark, we emphasize that our model does not require the brain to literally exist or operate in four spatial dimensions. Rather, through phase relationships and dynamic interference across a 2D cortical substrate, the brain may behave as if it were computing in a higher-dimensional space. This reframing of computation invites researchers to look beyond anatomical complexity toward emergent spatial and topological dynamics.

Ethics approval and consent to participate. This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication. The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials. All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests. The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Funding. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions. The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process. During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Aceituno, P. V., G. Yan, and Y. Y. Liu. "Tailoring Echo State Networks for Optimal Learning." iScience 23, no. 9 (August 6, 2020): 101440. [CrossRef]

- Alalayah, Khalid M., Emad M. Senan, Hamada F. Atlam, Islam A. Ahmed, and Hani S. A. Shatnawi.“Effective Early Detection of Epileptic Seizures through EEG Signals Using Classification Algorithms Based on t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding and K-Means.” Diagnostics (Basel) 13, no. 11 (June 3, 2023): 1957. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, N., and J. L. Krichmar. "A Sparse Quantized Hopfield Network for Online-Continual Memory." Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (May 2, 2024): 3722. [CrossRef]

- Balta, Gülşen, and Elkan G. Akyürek. “The Effect of Object Perception on Event Integration and Segregation.” Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 86 (2024): 2424–2437. [CrossRef]

- Beste, Christian, Alexander Münchau, and Christian Frings. 2023. “Towards a Systematization of Brain Oscillatory Activity in Actions.” Communications Biology 6, no. 137. [CrossRef]

- Branco, M. P., S. H. Geukes, E. J. Aarnoutse, N. F. Ramsey, and M. J. Vansteensel. “Nine Decades of Electrocorticography: A Comparison between Epidural and Subdural Recordings.” European Journal of Neuroscience 57, no. 8 (April 2023): 1260–88. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Heather, Michelle S. Goodman, Christopher R. Bowie, Reza Zomorrodi, Daniel M. Blumberger, et al. “Theta–Gamma Coupling and Ordering Information: A Stable Brain–Behavior Relationship across Cognitive Tasks and Clinical Conditions.” Neuropsychopharmacology 45 (2020): 2038–2047. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Neil. 2008. “Grid Cells and Theta as Oscillatory Interference: Theory and Predictions.” Hippocampus 18 (12): 1157–74. [CrossRef]

- Caputi, Lucia, Anastasiia Pidnebesna, and Jaroslav Hlinka.“Promises and Pitfalls of Topological Data Analysis for Brain Connectivity Analysis.” NeuroImage 238 (September 2021): 118245. [CrossRef]

- Carracedo-Reboredo, Patricia, José Liñares-Blanco, Natalia Rodríguez-Fernández, Francisco Cedrón, Francisco J. Novoa, et al. “A Review on Machine Learning Approaches and Trends in Drug Discovery.” Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 19 (August 12, 2021): 4538–58. [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, A., J. Amacker, M. Maiolo, N. Amato, M. Pereno, S. Riccardi, A. Danani, S. Ulzega, and M. Manconi. “High-Density EEG Power Topography and Connectivity during Confusional Arousal.” Cortex 155 (October 2022): 62–74. [CrossRef]

- Chellini, A., K. Salmaso, M. Di Domenico, N. Gerbi, L. Grillo, M. Donati, and M. Iosa. “Embodimetrics: A Principal Component Analysis Study of the Combined Assessment of Cardiac, Cognitive and Mobility Parameters.” Sensors 24, no. 6 (2024): 1898. [CrossRef]

- Clusella, Pau, Gustavo Deco, Morten L. Kringelbach, Giulio Ruffini, and Jordi Garcia-Ojalvo. “Complex Spatiotemporal Oscillations Emerge from Transverse Instabilities in Large-Scale Brain Networks.” PLOS Computational Biology, April 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cueva, Christopher J., Alex Saez, Encarni Marcos, Stefano Fusi, et al. 2020. “Low-Dimensional Dynamics for Working Memory and Time Encoding.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (37): 23021–23032. [CrossRef]

- Das, Sandip, Divya V. Anand, and Moo K. Chung. “Topological Data Analysis of Human Brain Networks through Order Statistics.” PLoS ONE 18, no. 3 (March 13, 2023): e0276419. [CrossRef]

- Dogra, Saurabh, Xin Wang, Ankur Gupta, Janusz Veraart, Koji Ishida, Deqiang Qiu, and Siroos Dehkharghani.“Acetazolamide-Augmented BOLD MRI to Assess Whole-Brain Cerebrovascular Reactivity in Chronic Steno-Occlusive Disease Using Principal Component Analysis.” Radiology 307, no. 3 (May 2023): e221473. [CrossRef]

- Duman, Ahmet N., and Ali E. Tatar. “Topological Data Analysis for Revealing Dynamic Brain Reconfiguration in MEG Data.” PeerJ 11 (July 20, 2023): e15721. [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, Jean-Pierre, and Tsvi Tlusty. “Dimensional Reduction in Complex Living Systems: Where, Why, and How.” BioEssays 43, no. 9 (2021): e2100062. [CrossRef]

- Effenberger, Felix, Pedro Carvalho, Igor Dubinin, and Wolf Singer. 2025. “The Functional Role of Oscillatory Dynamics in Neocortical Circuits: A Computational Perspective.” PNAS 122 (4): e2412830122. [CrossRef]

- Elmer, Stefan, Ira Kurthen, Martin Meyer, and Nathalie Giroud. “A Multidimensional Characterization of the Neurocognitive Architecture Underlying Age-Related Temporal Speech Processing.” NeuroImage 278 (2023): 120285. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpour, Zeinab, Greg Kronberg, Davide Reato, Lucas C. Parra, and Marom Bikson. 2021. “Temporal Interference Stimulation Targets Deep Brain Regions by Modulating Neural Oscillations.” Brain Stimulation 14 (1): 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Fakharian, Mohammad Amin, Alden M. Shoup, Paul Hage, Hisham Y. Elseweifi, and Reza Shadmehr. 2025. “A Vector Calculus for Neural Computation in the Cerebellum.” Science 388 (6749): 869–875. [CrossRef]

- Farisco, Michele, and Jean-Pierre Changeux. “About the Compatibility Between the Perturbational Complexity Index and the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory of Consciousness.” Neuroscience of Consciousness 2023, no. 1 (June 19, 2023): niad016. [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, Oscar, Urszula Gorska-Klimowska, Simon Henin, Rony Hirschhorn, Aya Khalaf, Alex Lepauvre, Ling Liu, et al. “Adversarial Testing of Global Neuronal Workspace and Integrated Information Theories of Consciousness.” Nature (2025). [CrossRef]

- Fingelkurts, Alexander A., and Andrew A. Fingelkurts. "Quantitative Electroencephalogram (qEEG) as a Natural and Non-Invasive Window into Living Brain and Mind in the Functional Continuum of Healthy and Pathological Conditions." Applied Sciences 12, no. 19 (2022): 9560. [CrossRef]

- Foldes, Stephen T., Santosh Chandrasekaran, Joseph Camerone, James Lowe, Richard Ramdeo, John Ebersole, and Chad E. Bouton. “Case Study: Mapping Evoked Fields in Primary Motor and Sensory Areas via Magnetoencephalography in Tetraplegia.” Frontiers in Neurology 12 (2021): 739693. [CrossRef]

- Furstenau, Norbert. “A Nonlinear Dynamics Model of Binocular Rivalry and Cognitive Multistability.” In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC’03): System Security and Assurance, 8–8 October 2003. IEEE, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Gallego, Juan A., Marc G. Perich, Lee E. Miller, and Sara A. Solla. 2017. “Neural Manifolds for the Control of Movement.” Neuron 94 (5): 978–984. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J., Y. Liu, J. Li, H. Li, T. Luo, Y. Wu, Y. Xu, and J. Wang. “High-Chern-Number and High-Temperature Quantum Hall Effect without Landau Levels.” National Science Review 7, no. 8 (August 2020): 1280–87. [CrossRef]

- Gosztolai, Adam, Robert L. Peach, Alexis Arnaudon, Mauricio Barahona, and Pierre Vandergheynst. “MARBLE: Interpretable Representations of Neural Population Dynamics Using Geometric Deep Learning.” Nature Methods 22 (2025): 612–620.

- Halužan Vasle, A., and M. Moškon. "Synthetic Biological Neural Networks: From Current Implementations to Future Perspectives." Biosystems 237 (March 2024): 105164. [CrossRef]

- Hope, T. M. H., A. Halai, J. Crinion, P. Castelli, C. J. Price, and H. Bowman. “Principal Component Analysis-Based Latent-Space Dimensionality Under-Estimation, with Uncorrelated Latent Variables.” Brain 147, no. 2 (2024): e14–e16. [CrossRef]

- Huber, Sebastian D. 2016. "Topological Mechanics." Nature Physics 12, no. 7: 621–623. [CrossRef]

- Imhof, Stephan, Christian Berger, Florian Bayer, Johannes Brehm, Laurens W. Molenkamp, Tobias Kiessling, and Ronny Thomale. 2018. "Topolectrical-Circuit Realization of Topological Corner Modes." Nature Physics 14, no. 9: 925–929. [CrossRef]

- Jazayeri, Mehrdad, and Srdjan Ostojic. 2021. “Interpreting Neural Computations by Examining Intrinsic and Embedding Dimensionality of Neural Activity.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 70: 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, James K., Songyuan Geng, Maximilian W. Hoffman, Hillel Adesnik, and Ralf Wessel. “Precision Multidimensional Neural Population Code Recovered from Single Intracellular Recordings.” Scientific Reports 10 (2020): Article 15997. [CrossRef]

- Klukas, Mirko, Marcus Lewis, and Ila Fiete. “Efficient and Flexible Representation of Higher-Dimensional Cognitive Variables with Grid Cells.” PLOS Computational Biology 16, no. 4 (2020): e1007796. [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, H., R. Bhaumik, K. L. Kinney, and J. M. Fitzgerald. “Principal Component Analysis and Neural Predictors of Emotion Regulation.” Behavioural Brain Research 338 (2018): 128–133. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, Sofie S., Kaan Kesgin, and Henrik Jörntell. “High-Dimensional Cortical Signals Reveal Rich Bimodal and Working Memory-like Representations among S1 Neuron Populations.” Communications Biology 7 (2024): Article 1043. [CrossRef]

- Kwag, Jeehyun, and Ole Paulsen. 2009. “The Timing of External Input Controls the Sign of Plasticity at Local Synapses.” Nature Neuroscience 12 (11): 1419–1421. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2400.PubMed Central.

- Langdon, Christopher, Mikhail Genkin, and Tatiana A. Engel. “A Unifying Perspective on Neural Manifolds and Circuits for Cognition.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 24 (2023): 363–377.

- Li, Y., A. Fogarty, B. Razavi, P. M. Ardestani, J. Falco-Walter, K. Werbaneth, K. Graber, K. Meador, and R. S. Fisher. “Impact of High-Density EEG in Presurgical Evaluation for Refractory Epilepsy Patients.” Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 219 (August 2022): 107336. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., X. Li, W. Ji, P. Li, S. Yan, and C. Zhang. “Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect with a High and Tunable Chern Number in Monolayer NdN₂.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 25, no. 27 (July 12, 2023): 18275–83. [CrossRef]

- Lin, R., Z. Zhou, S. You, R. Rao, and C. J. Kuo. "Geometrical Interpretation and Design of Multilayer Perceptrons." IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 35, no. 2 (February 2024): 2545–2559. [CrossRef]

- Lymburn, T., A. Khor, T. Stemler, D. C. Corrêa, M. Small, and T. Jüngling. "Consistency in Echo-State Networks." Chaos 29, no. 2 (February 2019): 023118. [CrossRef]

- Lohse M, Schweizer C, Price HM, Zilberberg O, Bloch I. 2018. Exploring 4D quantum Hall physics with a 2D topological charge pump. Nature 553, 55–58. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Ling, John D. Joannopoulos, and Marin Soljačić. 2014. "Topological Photonics." Nature Photonics 8, no. 11: 821–829. [CrossRef]

- Mallatt, Jon, Lincoln Taiz, Andreas Draguhn, Michael R. Blatt, and David G. Robinson. “Integrated Information Theory Does Not Make Plant Consciousness More Convincing.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 564 (July 30, 2021): 166–69. [CrossRef]

- Mashour, George A., Pieter Roelfsema, Jean-Pierre Changeux, and Stanislas Dehaene.“Conscious Processing and the Global Neuronal Workspace Hypothesis.” Neuron 105, no. 5 (March 4, 2020): 776–98. [CrossRef]

- Mediano, Pedro A. M., Fernando E. Rosas, David Bor, Anil K. Seth, and Adam B. Barrett.“The Strength of Weak Integrated Information Theory.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 26, no. 8 (August 2022): 646–55. [CrossRef]

- Meiser, A., A. Lena Knoll, and M. G. Bleichner. “High-Density Ear-EEG for Understanding Ear-Centered EEG.” Journal of Neural Engineering 21, no. 1 (January 9, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mitchell-Heggs, Richard, Sébastien Prado, Guilherme P. Gava, Michael A. Go, and Simon R. Schultz. “Neural Manifold Analysis of Brain Circuit Dynamics in Health and Disease.” Journal of Computational Neuroscience 51, no. 1 (February 2023): 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Myrov, Vladislav, Felix Siebenhühner, Joonas J. Juvonen, Gabriele Arnulfo, Satu Palva, and J. Matias Palva. “Rhythmicity of Neuronal Oscillations Delineates Their Cortical and Spectral Architecture.” Communications Biology 7 (2024): Article 405. [CrossRef]

- Mobbs, Anthony E. D., and Simon Boag. “A Social Science Trust Taxonomy with Emergent Vectors and Symmetry.” Frontiers in Psychology 15 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Montijn, Jorrit S., Guido T. Meijer, Carien S. Lansink, and Cyriel M.A. Pennartz. “Population-Level Neural Codes Are Robust to Single-Neuron Variability from a Multidimensional Coding Perspective.” Cell Reports 16, no. 9 (2016): 2486–2498. [CrossRef]

- Murray, John D., Alberto Bernacchia, Nicholas A. Roy, and Xiao-Jing Wang. 2016. “Stable Population Coding for Working Memory Coexists with Heterogeneous Neural Dynamics in Prefrontal Cortex.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (2): 394–399. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, Yashaswini. Nonlinear Dynamics of Binocular Rivalry: A Comparative Study. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.10005, 2018. https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.10005.

- Nieh, Edward H., et al. “Geometry of Abstract Learned Knowledge in the Hippocampus.” Nature 595 (2021): 80–84.

- Xu, Xinyu, Nicolas Drougard, and Raphaël N. Roy.“Does Topological Data Analysis Work for EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces?” Journal of Neural Engineering 22, no. 3 (May 29, 2025). [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, R. S., A. Higgins-Chen, D. Gupta, M. K. Chen, M. Naganawa, T. Toyonaga, Y. Lu et al. “Principal Component Analysis of Synaptic Density Measured with [(11)C]UCB-J PET in Early Alzheimer's Disease.” NeuroImage: Clinical 39 (2023): 103457. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Tomoki, Hannah M. Price, Alberto Amo, Nathan Goldman, Mohammad Hafezi, Ling Lu, Mikael C. Rechtsman, David Schuster, Jonathan Simon, Oded Zilberberg, and Iacopo Carusotto. 2019. "Topological Photonics." Reviews of Modern Physics 91, no. 1: 015006. [CrossRef]

- Parmar, Harshit, Brent Nutter, Robert Long, Sameer Antani, and Saugata Mitra.“Visualizing Temporal Brain-State Changes for fMRI Using t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding.” Journal of Medical Imaging (Bellingham) 8, no. 4 (July 2021): 046001. [CrossRef]

- Posani, Lorenzo, Shuqi Wang, Samuel P. Muscinelli, Liam Paninski, and Stefano Fusi. “Rarely Categorical, Always High-Dimensional: How the Neural Code Changes along the Cortical Hierarchy.” bioRxiv [Preprint], February 13, 2025. Originally published November 17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pourdavood, Parham, and Michael S. Jacob. “EEG Spectral Attractors Identify a Geometric Core of Resting Brain Activity.” bioRxiv (2023). [CrossRef]

- Price, Hannah M., Oded Zilberberg, Tomoki Ozawa, Iacopo Carusotto, and Nathan Goldman. 2015. "Four-Dimensional Quantum Hall Effect with Ultracold Atoms." Physical Review Letters 115, no. 19: 195303. [CrossRef]

- Roth, Noam, and Nicole C. Rust. “The Integration of Visual and Target Signals in V4 and IT during Visual Object Search.” Journal of Neurophysiology 122, no. 6 (December 1, 2019): 2522–2540. [CrossRef]

- Rustamov, Nabi, Joseph Humphries, Alexandre Carter, and Eric C. Leuthardt. “Theta-Gamma Coupling as a Cortical Biomarker of Brain-Computer Interface-Mediated Motor Recovery in Chronic Stroke.” Brain Communications 4, no. 3 (2022): fcac136. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T., S. Leutgeb, and J. K. Leutgeb. “Spatial and Memory Circuits in the Medial Entorhinal Cortex.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 32 (June 2015): 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Fangyao, et al. “EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using 4D Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network.” Cognitive Neurodynamics 14 (2020): 815–828.

- Shinn, Maxwell. “Phantom Oscillations in Principal Component Analysis.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 48 (2023): e2311420120. [CrossRef]

- Singh, Ray, and Chris Eliasmith. 2006. “Higher-Dimensional Neurons Explain the Tuning and Dynamics of Working Memory Cells.” Journal of Neuroscience 26 (14): 3667–3678. [CrossRef]

- Son, Jake J., Yasra Arif, Mikki Schantell, Madelyn P. Willett, Hallie J. Johnson, Hannah J. Okelberry, Christine M. Embury, and Tony W. Wilson. 2023. “Oscillatory Dynamics Serving Visual Selective Attention During a Simon Task.” Brain Communications 5 (3): fcad131. [CrossRef]

- Stringer, Carsen, et al. “High-Dimensional Geometry of Population Responses in Visual Cortex.” Nature 571 (2019): 361–365.

- Stringer, Carsen, et al. “Spontaneous Behaviors Drive Multidimensional, Brainwide Activity.” Science 364, no. 6437 (2019): eaav7893.

- Tamura, Makoto, Timothy J. Spellman, Andrew M. Rosen, Joseph A. Gogos, and Joshua A. Gordon. “Hippocampal–Prefrontal Theta–Gamma Coupling during Performance of a Spatial Working Memory Task.” Nature Communications 8 (2017): Article 2182. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, G., T. Yamane, J. B. Héroux, R. Nakane, N. Kanazawa, S. Takeda, H. Numata, D. Nakano, and A. Hirose. "Recent Advances in Physical Reservoir Computing: A Review." Neural Networks 115 (July 2019): 100–123. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi A. 2019. The multidimensional brain. Physics of Life Reviews, 31: 86-103. doi. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi A, Ahmad MZ, Peters JF. 2021. Neural computing in four spatial dimensions. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 15:349-357. [CrossRef]

- Ursino, Mauro, and Gabriele Pirazzini. “Theta–Gamma Coupling as a Ubiquitous Brain Mechanism: Implications for Memory, Attention, Dreaming, Imagination, and Consciousness.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 59 (2024): 101433. [CrossRef]

- Vakalopoulou, M., S. Christodoulidis, N. Burgos, O. Colliot, and V. Lepetit. "Deep Learning: Basics and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)." In Machine Learning for Brain Disorders, edited by O. Colliot. New York, NY: Humana, 2023. Chapter 3. PMID: 37988533.

- Vakani, R., and D. R. Nair. “Electrocorticography and Functional Mapping.” In Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 160, 313–27. Elsevier, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Voitov, Ivan, and Thomas D. Mrsic-Flogel. “Cortical Feedback Loops Bind Distributed Representations of Working Memory.” Nature 608 (2022): 381–389.

- von Wegner, F., S. Bauer, F. Rosenow, J. Triesch, and H. Laufs. “EEG Microstate Periodicity Explained by Rotating Phase Patterns of Resting-State Alpha Oscillations.” NeuroImage 224 (2021): 117372. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Luqi, Qian Lin, and Shanhui Fan. 2018. "Synthetic Dimension in Photonics." Optica 5, no. 11: 1396–1405. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shaoyun, Zhou Hu, Qian Wu, Hui Chen, Emil Prodan, Rui Zhu, and Guoliang Huang. “Smart Patterning for Topological Pumping of Elastic Surface Waves.” Science Advances 9, no. 30 (2023): eadh4310. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Z., and B. Wyble. "Hopfield and Hinton's Neural Network Revolution and the Future of AI." Patterns (New York) 5, no. 11 (November 8, 2024): 101094. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Qiancheng, et al. “A Multidimensional Coding Architecture of the Vagal Interoceptive System.” Nature 603 (2022): 878–884.

- Zhan, Xiaotian, Yuzhe Liu, Nicholas J. Cecchi, Olivier Gevaert, Michael M. Zeineh, Gerald A. Grant, and David B. Camarillo.“Finding the Spatial Co-Variation of Brain Deformation with Principal Component Analysis.” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 69, no. 10 (October 2022): 3205–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. F., R. Zhang, R. Mei, L. J. Zhou, H. Yi, Y. Q. Zhang, J. Yu, R. Xiao, K. Wang, N. Samarth, M. H. W. Chan, C. X. Liu, and C. Z. Chang. “Tuning the Chern Number in Quantum Anomalous Hall Insulators.” Nature 588, no. 7838 (December 2020): 419–23. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Yushan, and Yujie Wang.“Brain Fiber Structure Estimation Based on Principal Component Analysis and RINLM Filter.” Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 62, no. 3 (March 2024): 751–71. [CrossRef]

- Zilberberg O, Huang S, Guglielmon J, Wang M, Chen KP, et al. 2018. Photonic topological boundary pumping as a probe of 4D quantum Hall physics. Nature. 2018 Jan 3;553(7686):59-62. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

denote

a two-dimensional spatial lattice abstracted as a discrete manifold embedded in

a Euclidean plane. The lattice comprises nodes indexed by

denote

a two-dimensional spatial lattice abstracted as a discrete manifold embedded in

a Euclidean plane. The lattice comprises nodes indexed by  , where and denotes the number of units along each axis. Each node represents a spatial location capable of sustaining oscillatory activity. Define a scalar field , where describes the instantaneous state of the oscillatory unit at site and time .

, where and denotes the number of units along each axis. Each node represents a spatial location capable of sustaining oscillatory activity. Define a scalar field , where describes the instantaneous state of the oscillatory unit at site and time . denote the lattice spacing

constants along the respective dimensions. This yields a spatially indexed

field over a discretized, regular domain. The topology is flat, with periodic or fixed boundary conditions applicable depending on further dynamical considerations.

denote the lattice spacing

constants along the respective dimensions. This yields a spatially indexed

field over a discretized, regular domain. The topology is flat, with periodic or fixed boundary conditions applicable depending on further dynamical considerations. denotes the amplitude,

denotes the amplitude,  the angular frequency and the phase offset. The set and may be constant across the lattice or vary systematically to encode gradients, localized perturbations or wavefront propagation. Time t is treated as a continuous variable and the oscillators are considered decoupled at this stage, evolving independently.

the angular frequency and the phase offset. The set and may be constant across the lattice or vary systematically to encode gradients, localized perturbations or wavefront propagation. Time t is treated as a continuous variable and the oscillators are considered decoupled at this stage, evolving independently. ,

, are wave vectors defining

propagation direction and spatial frequency. Each term represents a planar wave

propagating through the lattice, contributing to the overall spatiotemporal

dynamics of the system. The interference among these components yields a

superlattice, i.e., a spatially and temporally modulated structure with regions

of constructive and destructive interference.

are wave vectors defining

propagation direction and spatial frequency. Each term represents a planar wave

propagating through the lattice, contributing to the overall spatiotemporal

dynamics of the system. The interference among these components yields a

superlattice, i.e., a spatially and temporally modulated structure with regions

of constructive and destructive interference. which modulates either the

phase or spatial frequency of the propagating waves. For example, a

phase-modulated topological pump may be defined as:

which modulates either the

phase or spatial frequency of the propagating waves. For example, a

phase-modulated topological pump may be defined as: ,

, .

. . If the temporal evolution

exhibits low-dimensional structure, this trajectory lies on a manifold

. If the temporal evolution

exhibits low-dimensional structure, this trajectory lies on a manifold  of dimension . Dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) or diffusion maps can be used to characterize the manifold M, yielding eigenvalues corresponding to dominant modes of variance.

of dimension . Dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) or diffusion maps can be used to characterize the manifold M, yielding eigenvalues corresponding to dominant modes of variance. , the eigenvalue spectrum quantifies the system’s effective embedding dimensionality. A steep decay suggests a low-dimensional manifold, while a flat spectrum implies higher-dimensional complexity.

, the eigenvalue spectrum quantifies the system’s effective embedding dimensionality. A steep decay suggests a low-dimensional manifold, while a flat spectrum implies higher-dimensional complexity.