Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Embodied Cognition: An Evolutionary and Free Energy Perspective

1.2. Neuronal Representations

2. Architectural Foundations of Embodied Cognition

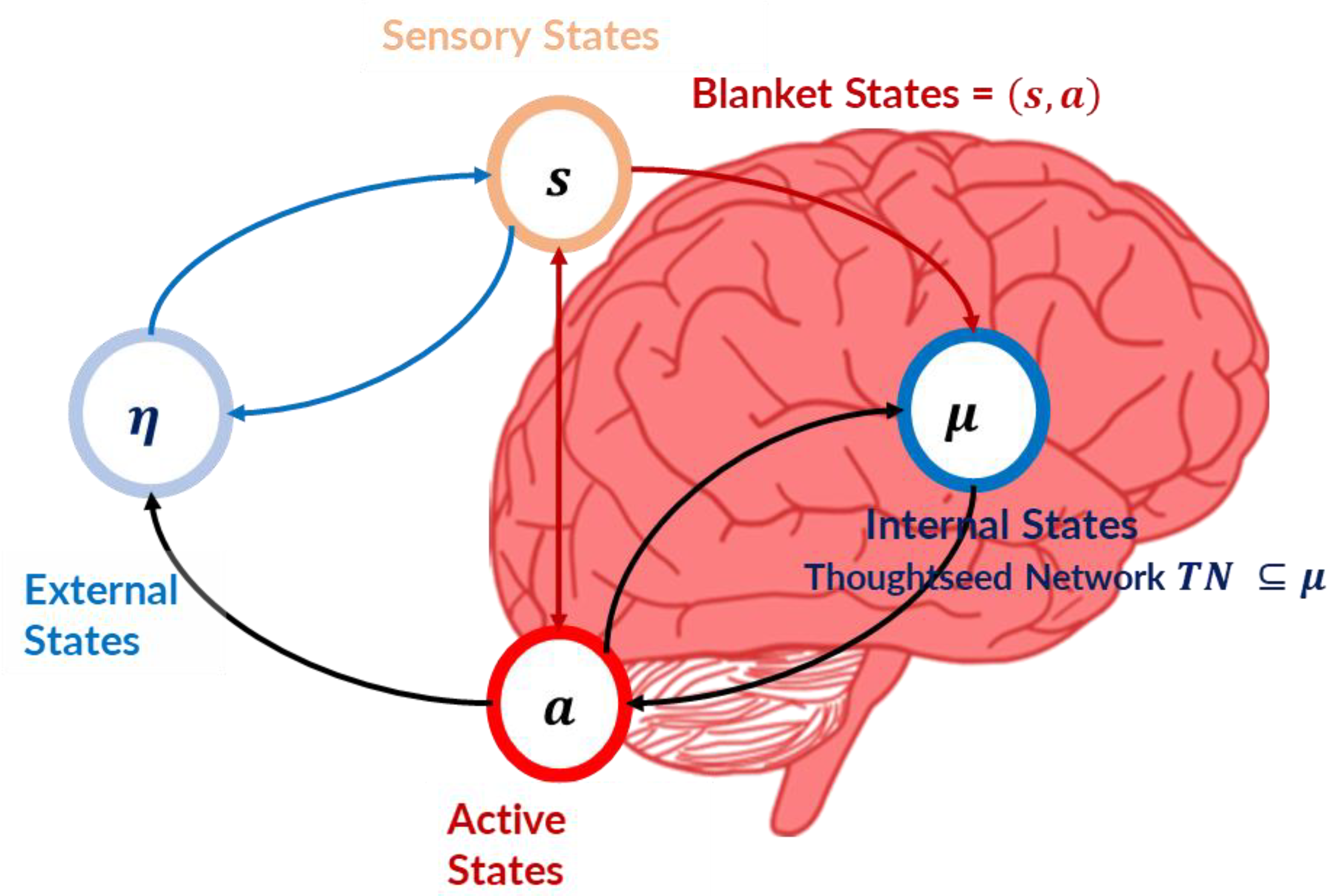

2.1. The Thoughtseed Hypothesis

| Concept | Symbol | Explanation |

| Neuronal Packet (NP) |  |

The fundamental unit of neuronal representation, a self-organizing ensemble of neurons that encodes a specific feature or aspect of the world. |

| Core Attractor |  |

The most probable and stable pattern of neural activity within a manifested NP, embodying its core functionality. |

| Subordinate Attractor |  |

Less dominant patterns of neural activity within an NP that may become active under specific conditions or in response to novel stimuli, offering flexibility and adaptability. |

| Encapsulated Knowledge Structure |  |

The structured knowledge content within a NP’s Markov Blanket, shaping its activity and contribution to KDs. |

| Superordinate Ensemble (SE) |  |

A higher-order organization emerging from the coordinated activity of multiple NPs, or even KDs, enabling the representation of more complex and abstract concepts. |

| Neuronal Packet Domain (NPD) |  |

A functional unit within the brain, comprised of interconnected SEs, specialized for specific cognitive processes or tasks. |

| Knowledge Domain (KD) |  |

A large-scale, organized structure within the brain’s internal model, representing interconnected networks of concepts, categories, and relationships that constitute a specific area of knowledge or expertise. |

| Thoughtseed |  |

A higher-order construct with agency, emerging from the coordinated activity of SEs across different KDs. It represents a unified and meaningful representation of a concept, idea, or percept and guides perception, action, and decision-making. |

| Thoughtseed Activation Level |  |

A measure of a thoughtseed’s prominence in the current cognitive landscape, calculated by weighing the probabilities that the brain’s state aligns with the thoughtseed’s dominant or subordinate attractor states. |

| Global Activation Threshold |  |

A global parameter, influenced by the consciousness state and arousal levels that determines the minimum activation level a thoughtseed must cross to enter the active thoughtseed pool. |

| Active Thoughtseed Pool |  |

The set of active thoughtseeds whose activation levels surpass the activation threshold at a given time. |

| Dominant Thoughtseed |  |

The thoughtseed within the active thoughtseed pool that has the highest activation level and is primarily shaping the content of consciousness at a given moment. |

| Thoughtseed Network |  |

The collection of interconnected thoughtseeds within the brain’s internal states, hypothesized to encode a generative model of the environment. |

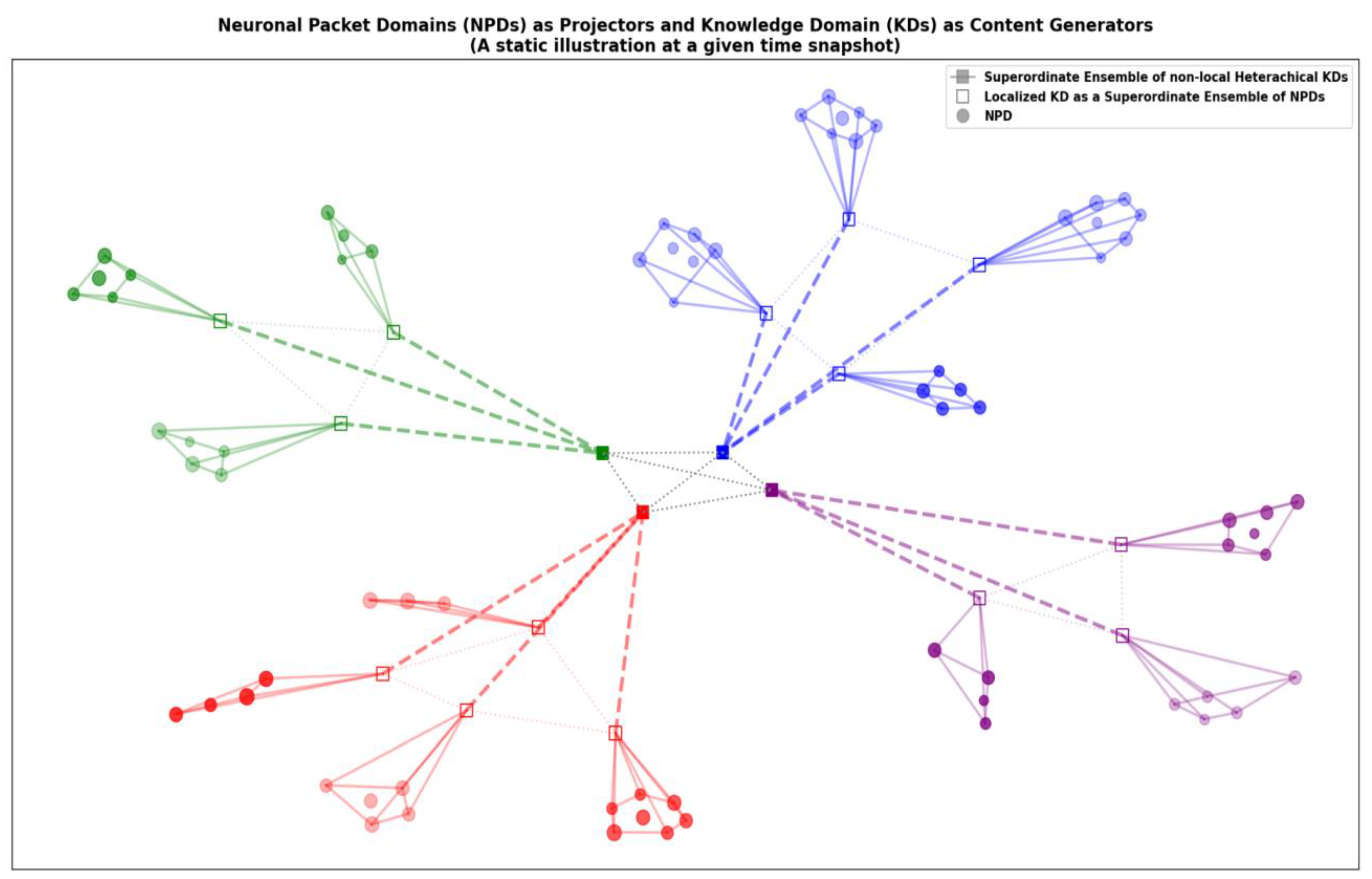

2.2. Neuronal Packet Domains

2.3. Neuronal Packets (NPs): The Fundamental Units of Neuronal Representation

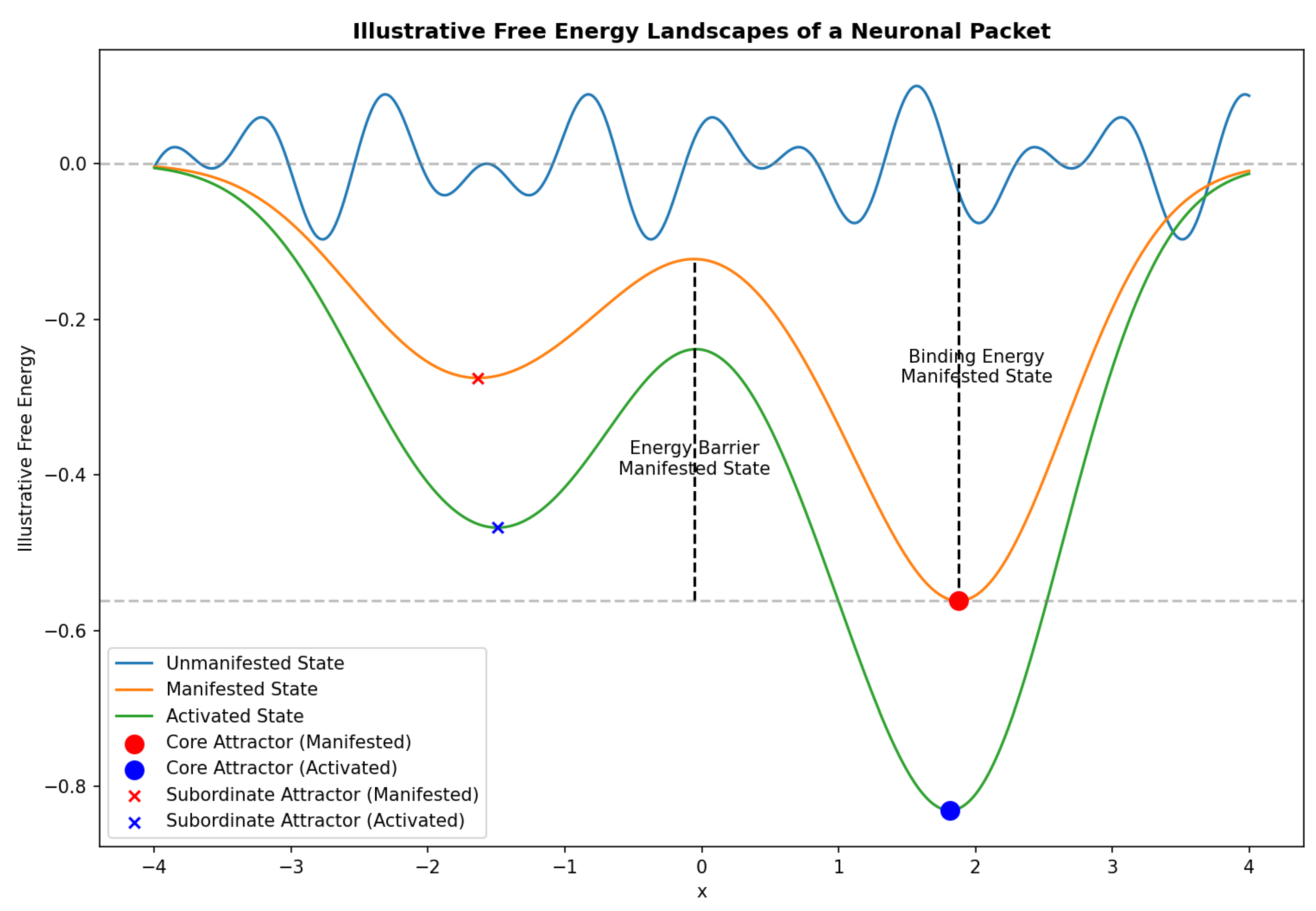

- Unmanifested State: Represents a potential configuration of neural activity with high prior probability under specific conditions, shaped by evolutionary priors. It can be viewed as a sparsely connected neural ensemble with low precision, corresponding to a shallow local minimum in the free energy landscape, indicating low stability and high potential for change.

- Manifested State: Emerges from the unmanifested state upon repeated exposure to relevant stimuli, leading to a phase transition [30] and the formation of a Markov Blanket stabilized by an energy barrier [30]. This Markov blanket structure may enable local computation and autonomy within the NP, while maintaining informational boundaries. It is characterized by increased coherence of neural activity, resulting in a stable state with a core attractor representing the most probable and stable pattern of neural activity [11,17]. This state embodies the NP’s core functionality with high certainty and can be interpreted as the mode of posterior distribution over the NP’s internal states given its Markov blanket [18]. This corresponds to a deeper local minimum in the free energy landscape, reflecting high stability and low surprise [51]. The depth of this global minimum can indicate the NP binding energy, reflecting the overall stability and resistance to changes in the core representation [30]. Subordinate attractors represent less dominant patterns of neural activity, which may become active under specific conditions or in response to novel stimuli [52]. They can be viewed as shallower local minima in the free energy landscape, separated from the core attractor by energy barriers. The existence of alternative attractors, along with the energy barriers that separate them, allows flexibility and adaptability in the NP response to changing inputs.

- Activated (or Spiking) State: A transient state characterized by heightened neural activity within the manifested NP ensemble triggered by specific inputs that resonate with the NP’s internal model. NP generates a response that may influence the behavior or cognition of a living system. This response can be interpreted as a consequence of the NP’s internal dynamics and its attempt to minimize free energy rather than deliberate or planned action. The active state can be seen as a temporary shift in the free energy landscape, where the core attractor becomes even more pronounced.

2.4. Knowledge Domains (KDs)

3. Thoughtseeds Network and Meta-Cognition

3.1. Formal Definition of a Thoughtseed

3.2. Key Characteristics of Thoughtseeds

- Sub-Agents: Thoughtseeds act as autonomous sub-agents within the cognitive system, engaging in active inference to generate predictions, influence actions, and update internal models based on sensory feedback [76]. This agency allows them to explore the environment and develop affordances.

- Pullback Attractor Dynamics: When active, thoughtseeds function as pullback attractors [11,77] by integrating information from multiple KDs to form coherent representations. This establishes a transient Markov blanket that maintains autonomy and computational independence. Each thoughtseed is associated with a core attractor, representing its most probable and stable pattern of neural activity, and may also have subordinate attractors, offering flexibility and adaptability.

- Goal-Directed Behavior: Thoughtseeds are inherently goal-directed and driven by the imperative to minimize Expected Free Energy (EFE ) [78]. They anticipate action consequences and select those that minimize EFE. The interaction between thoughtseeds and KDs results in affordances, or potential actions within the environment [79]. These affordances can be categorized as epistemic (opportunities for learning or exploration) or pragmatic (opportunities for goal fulfillment or exploitation) [80,81].

- Learning and adaptation: Thoughtseeds continuously engage in learning and adaptation through a process of Bayesian belief updating. Each thoughtseed possesses a generative model that predicts its future state and the content of consciousness it generates. As the thoughtseed interacts with the environment and receives sensory feedback, it updates its internal model and beliefs, thereby refining its predictions and contributing to more adaptive behavior [103]. This dynamic updating process enables thoughtseeds to maintain responsiveness to environmental changes and to continuously enhance their representation of the world.

3.2.1. Thoughtseed States

- Unmanifested: The thoughtseed exists as a potential configuration within the neural network, latent within interconnected knowledge domains, primed by prior experiences and learning. It is yet to actively influence cognition or behavior.

-

Manifested: The thoughtseed has emerged and is now part of the cognitive landscape, with the potential to influence thought and action. This state is further divided into the following substates:

- o

- Inactive: The thoughtseed is present but does not currently contribute to conscious experience. It resides in the background, with its core attractor and associated dynamics intact and potentially primed for activation.

- o

- Active: The thoughtseed is in the “active thoughtseed pool” and contributes to the content of consciousness, competing with other active thoughtseeds for dominance.

- o

- Dominant: The dominant thoughtseed is selected through an ongoing process of cumulative EFE minimization, in which thoughtseeds within the active thoughtseed pool compete in a winner-take-all dynamic. The thought seed that minimizes cumulative EFE over time gains dominance, enters the Global Workspace, and shapes the unitary conscious experience. This process ensures that the most relevant, predictive, and adaptive thoughtseed guides cognition and actions.

- o

- Dissipated: The thoughtseed has lost its influence and its core attractor has become significantly weakened or dissolved. It no longer contributes to the active thoughtseed pool and its constituent elements may be reabsorbed into the broader neural network or contribute to the formation of new thoughtseeds.

3.3. Thoughtseeds and the Global Workspace

3.3.1. Thoughtseeds as Information Processors

3.3.2. Competition for Dominance

3.3.3. The Unitary Nature of Conscious Experience

3.4. Meta-Cognition and Agency in Thoughtseed Dynamics

3.4.1. Meta-Cognitive Regulation of Thoughtseeds

3.4.2. Agency and Goal-Directed Thoughtseed Dynamics

3.4.3. Policies, Goals, and Affordances at the Agent Level

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. Towards a General Theory of Embodied Cognition

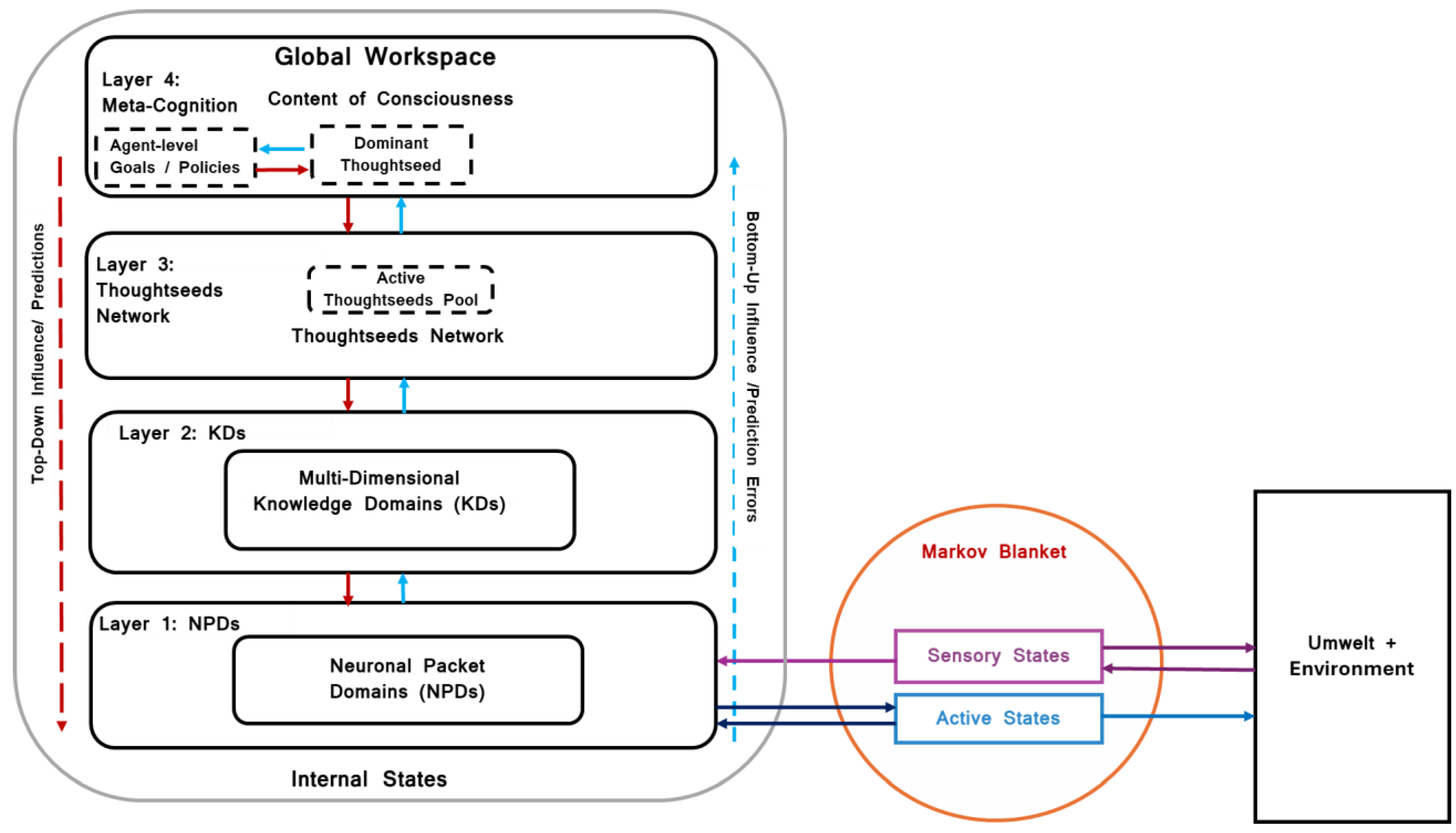

4.2. The Hierarchical Structure of the Thoughtseed Framework

- Neuronal Packet Domains (NPDs): NPDs form the foundation of the framework and consist of groups of neurons that process sensory input or generate potential actions. Within the GWT, these subsystems provide foundational and localized information processing. NPDs can be divided into domains responsible for sensory processing, motor planning, and internal state regulation, which contribute raw data to higher-order representations.

- Knowledge Domains (KDs): KDs represent large-scale networks that integrate knowledge, memories, and conceptual categories. They serve as structured repositories from which thoughtseeds are drawn. Within the GWT, KDs act as functional modules that hold specialized knowledge and are accessible to the global workspace when relevant. For example, recognizing a dog involves KDs related to visual processing, auditory associations (barking), and emotional contexts (companionship).

- Thoughtseeds Network: Thoughtseeds represent dynamic, self-organizing entities that emerge from the coordinated activity within and across KDs. In the GWT context, thoughtseeds represent potential candidates for entry into the global workspace, where they can shape conscious experiences and direct behavior. Each thoughtseed is a coherent pattern of neural activity associated with specific concepts, percepts, or possible actions. Thoughtseeds act as cognitive sub-agents, actively generating predictions and selecting actions to minimize free energy, and constantly updating based on sensory feedback.

- Meta-Cognition, Dominant Thoughtseed and Higher-Order Thoughtseeds: This level involves higher-order thoughtseeds that modulate attention and guide goal-directed behavior. Higher-order thoughtseeds reflect the agent’s global goals, influencing which lower-level thoughtseeds gain prominence in the global workspace. In terms of GWT, these higher-order constructs govern the selection of conscious content by modulating attentional precision and prioritizing relevant information. This helps shape global policies that determine the actions of the living system in a goal-oriented manner. The selection of a dominant thoughtseed can be seen as a discrete event, leading to a distinct shift in conscious content.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.4. Key Limitations

- Metastability of Thoughtseeds: Thoughtseed dynamics are inherently metastable with rapid transitions between states. This makes it difficult to isolate core attractors representing stable knowledge or behaviors, posing challenges in empirically capturing and measuring the dynamic properties of thoughtseeds [52,107,108,109].

- Mapping Distributed Neural Activity: Given the complexity of the brain’s distributed networks, linking specific patterns of neural activity to cognitive processes (e.g., thoughtseeds) is fraught with difficulty. Misinterpretation can arise without a clear framework that maps distributed signals to well-defined cognitive domains [110,111].

- Hierarchical Complexity: The nested Markov blanket structure of thoughtseeds introduces additional complexity in understanding how higher- and lower-order processes interact. This complicates the experimental design and analysis, especially when attempting to link abstract thought processes to neurobiological signatures [31,34].

- Vast Repertoire of Brain States: The extensive diversity of potential brain states and thoughtseed configurations presents a significant challenge for both empirical investigation and computational modeling. The isolation and characterization of specific thoughtseed dynamics within this vast repertoire necessitates meticulous experimental design and sophisticated analytical techniques [107,108,109,110,111]. This limitation underscores the need for focused research paradigms, such as the study of meditation or deep focus states, wherein the repertoire of brain states may be more constrained and specific thoughtseed trajectories can be more readily identified.

4.5. Future Directions

- Computational Modeling: Given the vast repertoire of potential brain states, developing a comprehensive computational model that captures the full spectrum of thoughtseed dynamics presents a significant challenge. Consequently, the analysis of thoughtseed dynamics is particularly suited to focused attention contexts, such as meditation or deeply focussed actions. These conditions, characterized by reduced mind-wandering and enhanced attentional precision, facilitate more precise observation of thoughtseed trajectories and their interactions. Simulating thoughtseed transitions as multi-dimensional trajectories could enable the generation of testable hypotheses regarding their neural correlates, facilitating comparisons with fMRI data, particularly in relation to neural assembly ignition [24]. By adopting the Leading Eigenvector Dynamics Analysis (LEiDA) and Probabilistic Metastable Substate (PMS) framework [112], thoughtseeds can be represented as dynamic trajectories in a multi-dimensional state space derived from neuroimaging data. This biologically grounded and empirically testable approach allows researchers to align hypothesized thoughtseeds—such as mind-wandering, breath focus, and meta-awareness—with specific neural patterns. Such alignment could provide critical insights into how meditation practices influence cognitive dynamics and conscious experience.

- Cognitive Development: Investigate how the thoughtseed framework can enhance our understanding of cognitive development across the lifespan, particularly in learning, memory, and complex skill acquisition. Early research could target specific domains, such as object permanence [113] or numerical cognition [114], to observe how thoughtseeds emerge and evolve in these processes. Additionally, the development of thoughtseeds may also be investigated in the context of the emergence of discrete symbols and language [115,116].

- Clinical Applications: Explore the thoughtseed framework’s potential in understanding and treating attention disorders by examining how disruptions in thoughtseed dynamics may contribute to specific clinical conditions. Additionally, investigate whether interventions targeting thoughtseed regulation can enhance cognitive function in these contexts.

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Institutional Review Board Statement

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Futuyma, D.J. Evolutionary Biology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 500–501. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J.M. A New Factor in Evolution. Am. Nat. 1896, 30, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species; John Murray, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J.L.; Larsen, C.S. The Nurture of Nature: Genetics, Epigenetics, and Environment in Human Biohistory. The American Historical Review 2014, 119, 1500–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.; Richerson, P.J. Culture and the Evolutionary Process; University of Chicago Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Laland, K.N.; Odling-Smee, J.; Feldman, M.W. Niche Construction, Biological Evolution, and Cultural Change. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2000, 23, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odling-Smee, F.J.; Laland, K.N.; Feldman, M.W. Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution; Princeton University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Noë, A. Action in Perception; MIT Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Ao, P. Free Energy, Value, and Attractors. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 2012, 937860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, E. What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell; Cambridge University Press, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolis, G.; Prigogine, I. Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems; Wiley, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Conant, R.C.; Ross Ashby, W.R. Every Good Regulator of a System Must Be a Model of That System. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1970, 1, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J. The Free Energy Principle: A Unified Approach to Biological Systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2010, 366, 2257–2268. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Kilner, J.; Frith, C. A Free Energy Formulation of Active Inference. Front. Comp. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, T.; Friston, K.J. Working Memory as Active Inference. Biol. Cybern. 2018, 112, 417–443. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Parr, T.; De Vries, P. The Graphical Brain: A Framework for Understanding Brain Function. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Heins, C.; Verbelen, T.; Da Costa, L.; Salvatori, T.; Markovic, D.; Tschantz, A.; Koudahl, M.; Buckley, C.; Parr, T. From Pixels to Planning: Scale-Free Active Inference. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, P.B.; Friston, K.J.; Ramstead, M.J.D.; Ploeger, A.; Hohwy, J. The Hierarchically Mechanistic Mind: An Evolutionary Systems Theory of the Human Brain, Cognition, and Behavior. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 19, 1319–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodor, J.A. The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology; MIT Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Josselyn, S.A.; Tonegawa, S. Memory Engrams: Recalling the past and Imagining the Future. Science 2020, 367, eaaw4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, D.O. The Organization of Behavior; Wiley & Sons, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene, S. Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts; Viking Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene, S.; Changeux, J.-P. Experimental and Theoretical Approaches to Conscious Processing. Neuron 2011, 70, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Sergent, C.; Changeux, J.-P. A Neuronal Network Model Linking Subjective Reports and Objective Physiological Data During Conscious Perception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 8520–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yufik, Y.M.; Friston, K. Life and Understanding: The Origins of ‘Understanding‘ in Self-Organizing Nervous Systems. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.R.; Razi, A.; Parr, T.; Kirchhoff, M.; Friston, K. On Markov Blankets and Hierarchical Self-Organisation. J. Theor. Biol. 2020, 486, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M.J.D.; Hesp, C.; Tschantz, A.; Smith, R.; Constant, A.; Friston, K. Neural and Phenotypic Representation Under the Free-Energy Principle. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufik, Y.M. The Understanding Capacity and Information Dynamics in the Human Brain. Entropy (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 21, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, M.; Parr, T.; Palacios, E.; Friston, K.; Kiverstein, J. The Markov Blankets of Life: Autonomy, Active Inference and the Free Energy Principle. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20170792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M.J.D.; Kirchhoff, M.D.; Friston, K.J. A Tale of Two Densities: Active Inference Is Enactive Inference. Adapt. Behav. 2020, 28, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramstead, M.J.; Albarracin, A.M.; Kiefer, A.; Klein, B.; Fields, C.; Friston, K.; Safron, A. The Inner Screen Model of Consciousness: Applying the Free Energy Principle Directly to the Study of Conscious Experience. Neurosci. Conscious. 2023, 2023, niac013. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.J.; Wiese, W.; Hobson, J.A. Sentience and the Origins of Consciousness: From Cartesian Duality to Markovian Monism. Entropy 2020, 22, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baars, B.J. the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind; Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Naccache, L. Towards a Cognitive Neuroscience of Consciousness: Basic Evidence and a Workspace Framework. Cognition 2001, 79, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, C.; Glazebrook, J.F.; Levin, M. Minimal physicalism as a scale-free substrate for cognition and consciousness. Neuroscience of Consciousness 2021, 2021, niab013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Uexküll, J. A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds. In. Semiotica; Springer, 1934; 89 (4), (5–80). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Da Costa, L.; Sakthivadivel, D.A.R.; Heins, C.; Pavliotis, G.A.; Ramstead, M.; Parr, T. Path Integrals, Particular Kinds, and Strange Things. Phys. Life Rev. 2023, 47, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. Complex Brain Networks: Graph Theoretical Analysis of Structural and Functional Systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O.; Betzel, R.F. Modular Brain Networks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, I.; Ramstead, M.J.D.; Convertino, L.; Bhat, A.; Friston, K.; Parr, T. Markov Blankets in the Brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 125, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.J.; Martin, K.A. A Functional Microcircuit for Cat Visual Cortex. J. Physiol. 1991, 440, 735–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountcastle, V.B. The Columnar Organization of the Neocortex. Brain 1997, 120, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quartz, S.R.; Sejnowski, T.J. The Neural Basis of Cognitive Development: A Constructivist Manifesto. Behav. Brain Sci. 1997, 20, 537–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, S. A Vision of the Brain; Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo, J.J.; Zoccolan, D.; Rust, N.C. How Does the Brain Solve Visual Object Recognition? Neuron 2012, 73, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markov, N.T.; Ercsey-Ravasz, M.M.; Ribeiro Gomes, A.R.; Lamy, C.; Magrou, L.; Vezoli, J.; Misery, P.; Falchier, A.; Quilodran, R.; Gariel, M.A.; Sallet, J.; Gamanut, R.; Huissoud, C.; Clavagnier, S.; Giroud, P.; Sappey-Marinier, D.; Barone, P.; Dehay, C.; Toroczkai, Z.; Knoblauch, K.; Van Essen, D.C.; Kennedy, H. A Weighted and Directed Interareal Connectivity Matrix for Macaque Cerebral Cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, G.M. Neural Darwinism: The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection; Basic Books, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Riesenhuber, M.; Poggio, T. Hierarchical Models of Object Recognition in Cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 1999, 2, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiebel, S.J.; Daunizeau, J.; Friston, K.J. A Hierarchy of Time-Scales and the Brain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, M.I.; Huerta, R.; Laurent, G. Neuroscience. Transient Dynamics for Neural Processing. Science 2008, 321, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarchik, A.N.; Serrano, N.P.; Jaimes-Reátegui, R. Brain Connectivity Hypergraphs. 2024 8th Scientific School Dynamics of Complex Networks and their Applications (DCNA), Kaliningrad, Russian Federation, 2024, pp. 190-193. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. Understanding Brain Networks and Brain Organization. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 400–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. Hierarchical Models in the Brain. PLOS Comp. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-López, G.; Zhou, C.S.; Kurths, J. Exploring Brain Function from Anatomical Connectivity. Front. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelke, E.S.; Kinzler, K.D. Core Knowledge. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattisapu, C.; Verbelen, T.; Pitliya, R.J.; Kiefer, A.B.; Albarracin, M. Free Energy in a Circumplex Model of Emotion. arXiv Preprint 2024, arXiv:2407.02474. [Google Scholar]

- Sladky, R.; Hahn, A.; Karl, I.L.; Geissberger, N.; Kranz, G.S.; Tik, M.; Kraus, C.; Pfabigan, D.M.; Gartus, A.; Lanzenberger, R.; Lamm, C. Dynamic Causal Modeling of the Prefrontal/Amygdala Network During Processing of Emotional Faces. Brain Connect. 2022, 12, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solms, M. The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness; Profile Books, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, W. Neuronal Synchrony: A Versatile Code for the Definition of Relations? Neuron 1999, 24, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.R.; Isomura, T.; Parr, T.; Friston, K. The Emergence of Synchrony in Networks of Mutually Inferring Neurons. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelfsema, P.R. Solving the Binding Problem: Assemblies Form When Neurons Enhance Their Firing Rate-They Don’t Need to Oscillate or Synchronize. Neuron 2023, 111, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K.J.; Kiebel, S.J. Predictive Coding Under the Free-Energy Principle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safron, A.; Çatal, O.; Verbelen, T. Generalized Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (G-SLAM) as Unification Framework for Natural and Artificial Intelligences: Towards Reverse Engineering the Hippocampal/Entorhinal System and Principles of High-Level Cognition. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 787659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, L.R.; Wixted, J.T.; Clark, R.E. Recognition Memory and the Medial Temporal Lobe: A New Perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenbaum, H. The Hippocampus and Its Role in Navigation and Memory: A Twenty-Five-Year Perspective. Neuron 2017, 95, 644–661. [Google Scholar]

- Stachenfeld, K.L.; Botvinick, M.M.; Gershman, S.J. The Hippocampus as a Predictive Map. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeDoux, J.E.; Brown, R. A Higher-Order Theory of Emotional Consciousness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E2016–E2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, E.A.; LeDoux, J.E. Contributions of the Amygdala to Emotion Processing: From Animal Models to Human Behavior. Neuron 2005, 48, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.K.; Cohen, J.D. An Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuster, J.M. The Prefrontal Cortex, 5th ed.; Academic Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ororbia, A.; Friston, K. Mortal Computation: A Foundation for Biomimetic Intelligence. arXiv Preprint 2023, arXiv:2311.09589. [Google Scholar]

- Mashour, G.A.; Roelfsema, P.; Changeux, J.-P.; Dehaene, S. Conscious Processing and the Global Neuronal Workspace Hypothesis. Neuron 2020, 105, 776–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; SenGupta, B.; Auletta, G. Cognitive Dynamics: From Attractors to Active Inference. Proc. IEEE 2014, 102, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.K. The Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: From Interoceptive Inference to Sensorimotor Contingencies. In Open MIND; Metzinger, T.K., Windt, J.M., Eds.; MIND Group, 2015; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Haken, H. Synergetics: An Introduction. Non-equilibrium Phase Transitions and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology (3rd Rev. enl. Ed.); Springer-Verlag, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, T.; Friston, K.J. Generalised Free Energy and Active Inference. Biol. Cybern. 2019, 113, (5–6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Theory of Affordances. Hilldale, USA 1977, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Frith, C. A Duet for One. Conscious. Cogn. 2015, 36, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. Affordance and Active Inference. In Affordances in Everyday Life: A Multidisciplinary Collection of Essays; Springer International Publishing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deco, G.; Ponce-Alvarez, A.; Mantini, D.; Romani, G.L.; Hagmann, P.; Corbetta, M. Resting-State Functional Connectivity Emerges from Structurally and Dynamically Shaped Slow Linear Fluctuations. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 11239–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deco, G.; Tononi, G.; Boly, M.; Kringelbach, M.L. Rethinking Segregation and Integration: Contributions of Whole-Brain Modelling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desimone, R.; Duncan, J. Neural Mechanisms of Selective Visual Attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1995, 18, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, H.; Friston, K.J. Attention, Uncertainty, and Free-Energy. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of Goal-Directed and Stimulus-Driven Attention in the Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzinger, T. Phenomenal Transparency and Cognitive Self-Reference. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2003, 2, 353–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandved-Smith, L.; Hesp, C.; Mattout, J.; Friston, K.; Lutz, A.; Ramstead, M.J.D. Towards a Computational Phenomenology of Mental Action: Modelling Meta-awareness and Attentional Control with Deep Parametric Active Inference. Neurosci. Conscious. 2021, 2021, niab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. Life as We Know It. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20130475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Rigoli, F.; Ognibene, D.; Mathys, C.; Fitzgerald, T.; Pezzulo, G. Active Inference and Epistemic Value. Cogn. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo, G.; Rigoli, F.; Friston, K. Active Inference, Homeostatic Regulation and the Origins of Consciousness. J. Conscious. Stud. 2013, 20, 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.J.; Fagerholm, E.D.; Zarghami, T.S.; Parr, T.; Hipólito, I.; Magrou, L.; Razi, A. Parcels and Particles: Markov Blankets in the Brain. Netw. Neurosci. 2021, 5, 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, D.J. Facing up to the Problem of Consciousness. J. Conscious. Stud. 1995, 2, 200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Yufik, Y.M. Understanding, Consciousness and Thermodynamics of Cognition. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2013, 55, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Friston, K.J. From Cognitivism to Autopoiesis: Towards a Computational Framework for the Embodied Mind. Synthese 2018, 195, 2459–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglia, L.; Wilson, R.A. Embodied Cognition. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2013, 4, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo, G.; D‘Amato, L.; Mannella, F.; Priorelli, M.; Van de Maele, T.; Stoianov, I.P.; Friston, K. Neural Representation in Active Inference: Using Generative Models to Interact With—And Understand—The Lived World. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1534, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind; Harvard University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, J. Supervenience, Consciousness and Scientific Practice. Presented at the International Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (IASSC) Conference, 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin-Kumar, A.; Doiron, B. Slow Dynamics and High Variability in Balanced Cortical Networks with Clustered Connections. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, J.; Ludwig, T. What Is a Mathematical Structure of Conscious Experience? Synthese 2024, 203, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscaglia, M.; Gastaldi, C.; Gerstner, W.; Quian Quiroga, R. A Dynamic Attractor Network Model of Memory Formation, Reinforcement and Forgetting. PLOS Comp. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, T.; Da Costa, L.; Heins, C.; Ramstead, M.J.D.; Friston, K.J. Memory and Markov Blankets. Entropy (Basel) 2021, 23, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G. Rhythms of the Brain; Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fries, P. Rhythms for Cognition: Communication Through Coherence. Neuron 2015, 88, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporns, O. Networks of the Brain; MIT Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tognoli, E.; Kelso, J.A.S. The Metastable Brain. Neuron 2014, 81, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L. Metastability and Coherence in Brain Dynamics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L. Hierarchy of Information Processing in the Brain: A Novel ‘Intrinsic Ignition’ Framework. Neuron 2017, 94, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deCharms, R.C.; Zador, A. Neural Representation and the Cortical Code. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000, 23, 613–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rué-Queralt, J.; Stevner, A.; Tagliazucchi, E.; Laufs, H.; Kringelbach, M.L.; Deco, G.; Atasoy, S. Decoding Brain States on the Intrinsic Manifold of Human Brain Dynamics Across Wakefulness and Sleep. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrichs, A.; Sanz Perl, Y.; Martínez-Molina, N.; Biarnes, C.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Fernández-Real, J.M.; Ramos, R.; Martí, R.; Pamplona, R.; Brugada, R.; Serena, J.; Ramió-Torrentà, L.; Coll-De-Tuero, G.; Gallart, L.; Barretina, J.; Vilanova, J.C.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Saba, L.; Pedraza, S.; Kringelbach, M.L.; Puig, J.; Deco, G. The Effect of External Stimulation on Functional Networks in the Aging Healthy Human Brain. Cereb. Cortex 2022, 33, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaget, J.; Cook, M.T. The Development of Object Concept; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Nieder, A. The Neuronal Code for Number. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Al Roumi, F.; Lakretz, Y.; Planton, S.; Sablé-Meyer, M. Symbols and mental programs: A hypothesis about human singularity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2022, 26, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S. How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better than Any Machine... for Now; Viking Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).