Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How do overall ESG scores (Environmental, Social, Governance) and specific operational ESG metrics (e.g., CO2 emissions, energy use, board size, injury rate) influence firms' stock excess returns within the global industrial and manufacturing sector?

- RQ2: Do firms categorized by distinct ESG risk levels (High, Medium, compared to Low) exhibit significantly different stock excess returns within the global industrial and manufacturing sector?

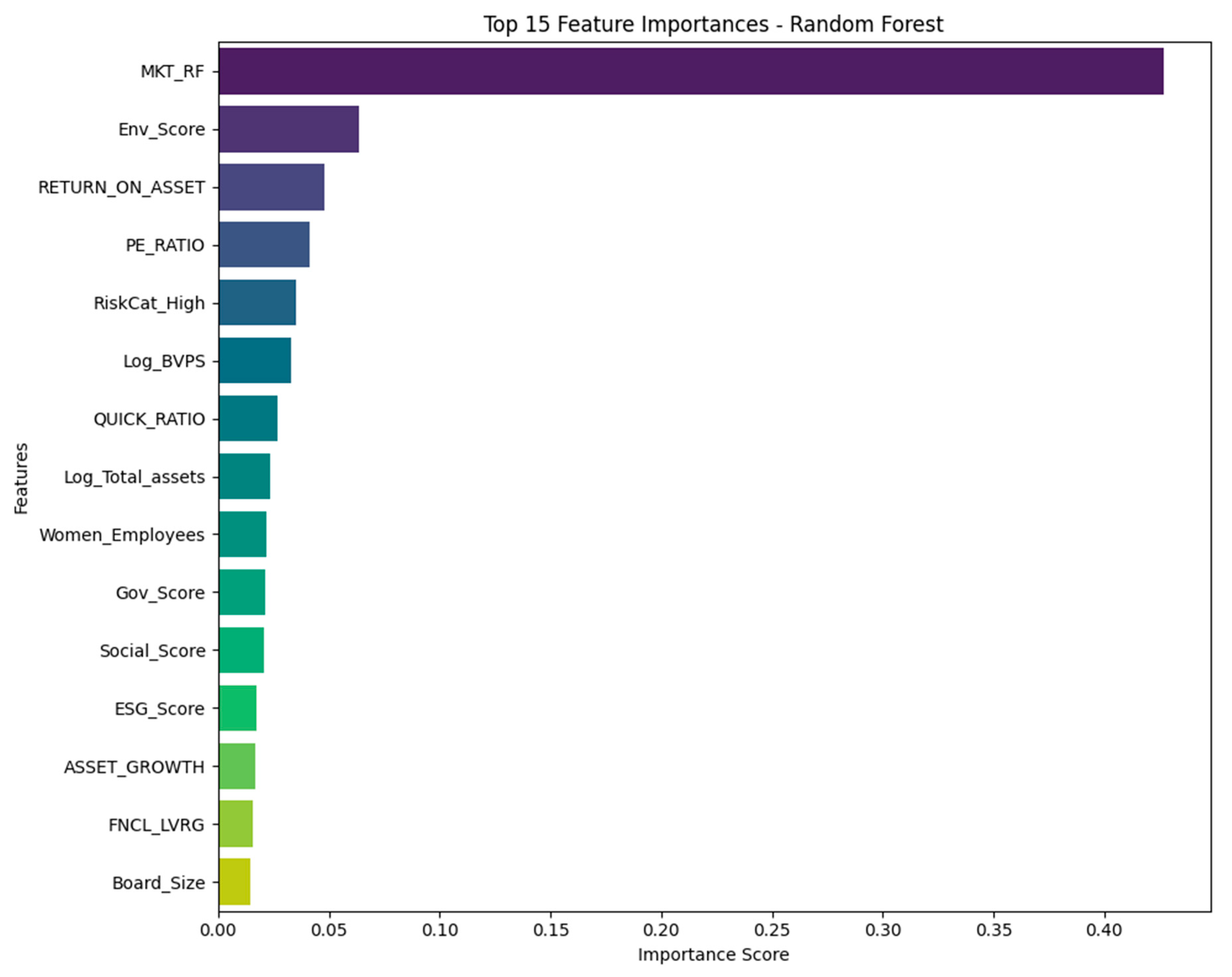

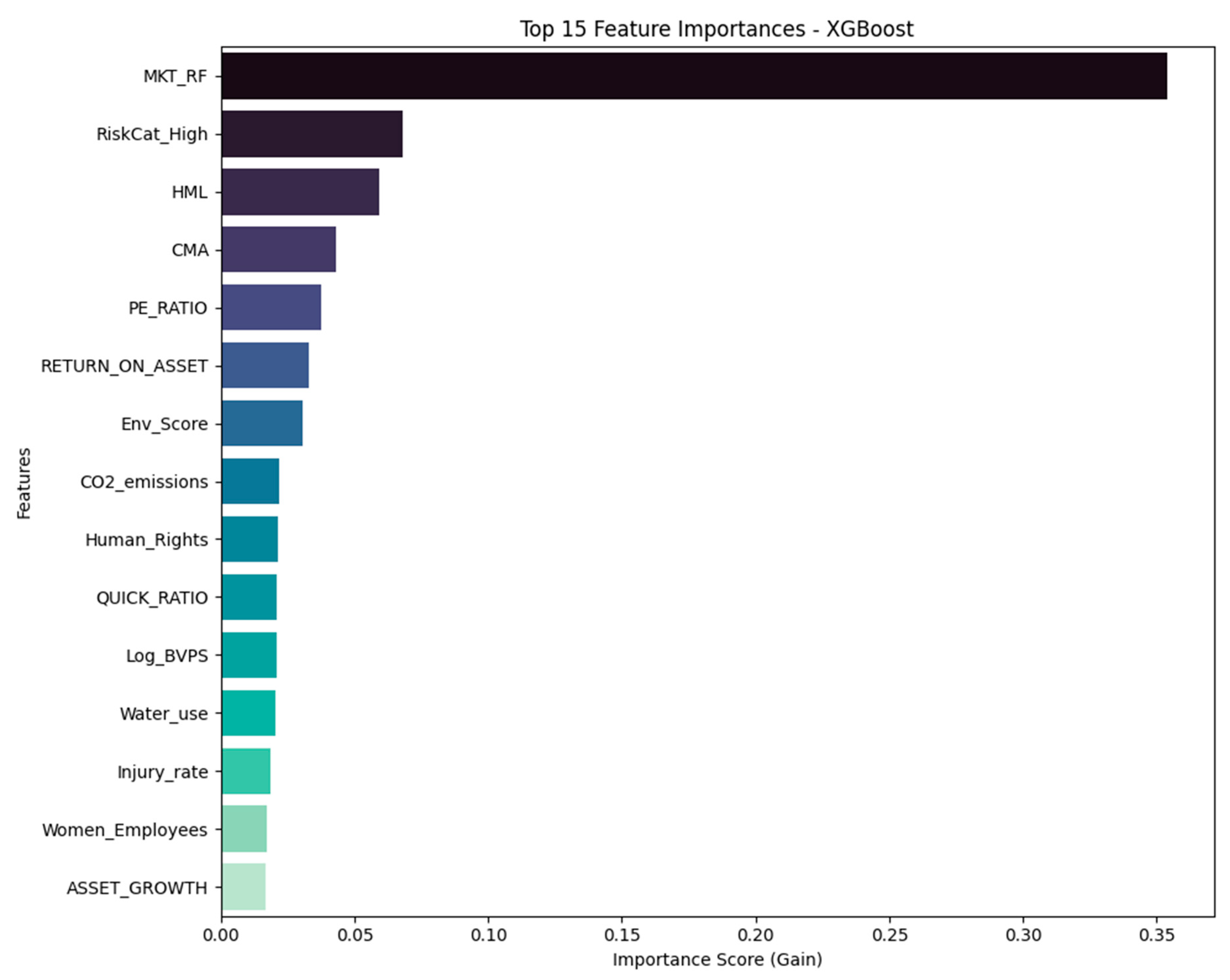

- RQ3: Using machine learning approaches (Random Forest and XGBoost), what are the most influential ESG characteristics and market factors in predicting firms' stock excess returns within the global industrial and manufacturing sector?

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks for ESG and Corporate Financial Performance (CFP)

2.2. Literature Review

2.2.1. Overview of ESG and Financial Performance (EFP) Research in Global Context

2.2.2. Current Trends and Innovations in the Global Manufacturing and Industrials Sector (2025) and Their ESG/Financial Implications

2.2.3. ESG, Financial Performance, and Risk Ratings in the Global Manufacturing Context

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Sources and Collection

- Their common usage in prior empirical ESG-financial performance (EFP) literature facilitates comparability of findings with existing research. Data availability and consistency across a global sample, given the challenges of international ESG data collection.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

3.4. Panel Regression and Machine Learning Models

3.5. Model Specification Tests

4. Results

4.1. Data Characteristics and Model Specification Diagnostics

4.2. Impact of Overall ESG Scores and Operational Metrics on Excess Returns (Fixed Effects Panel Models)

4.3. Influence of ESG Risk Categories on Excess Returns (Random Effects Panel Model)

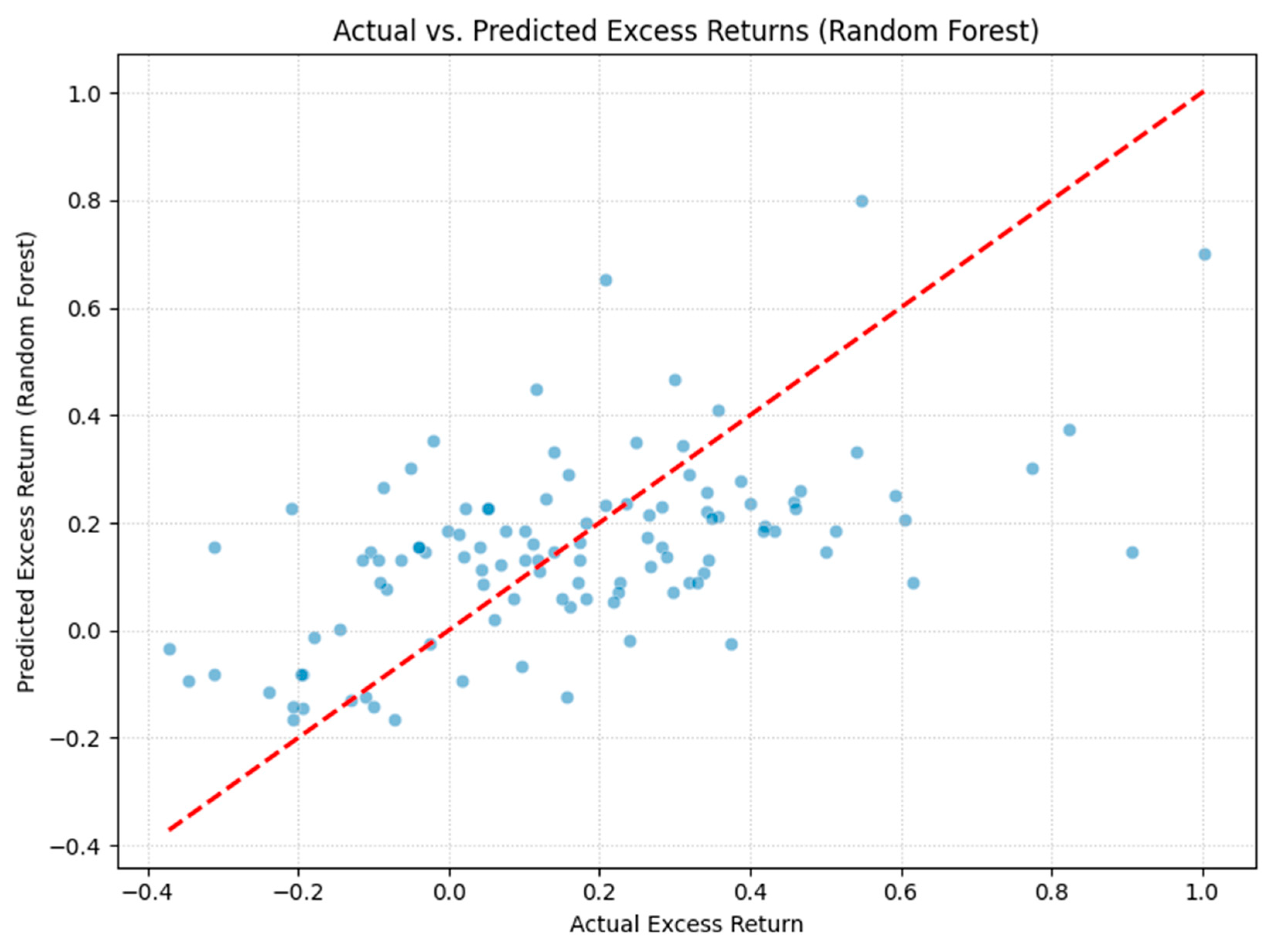

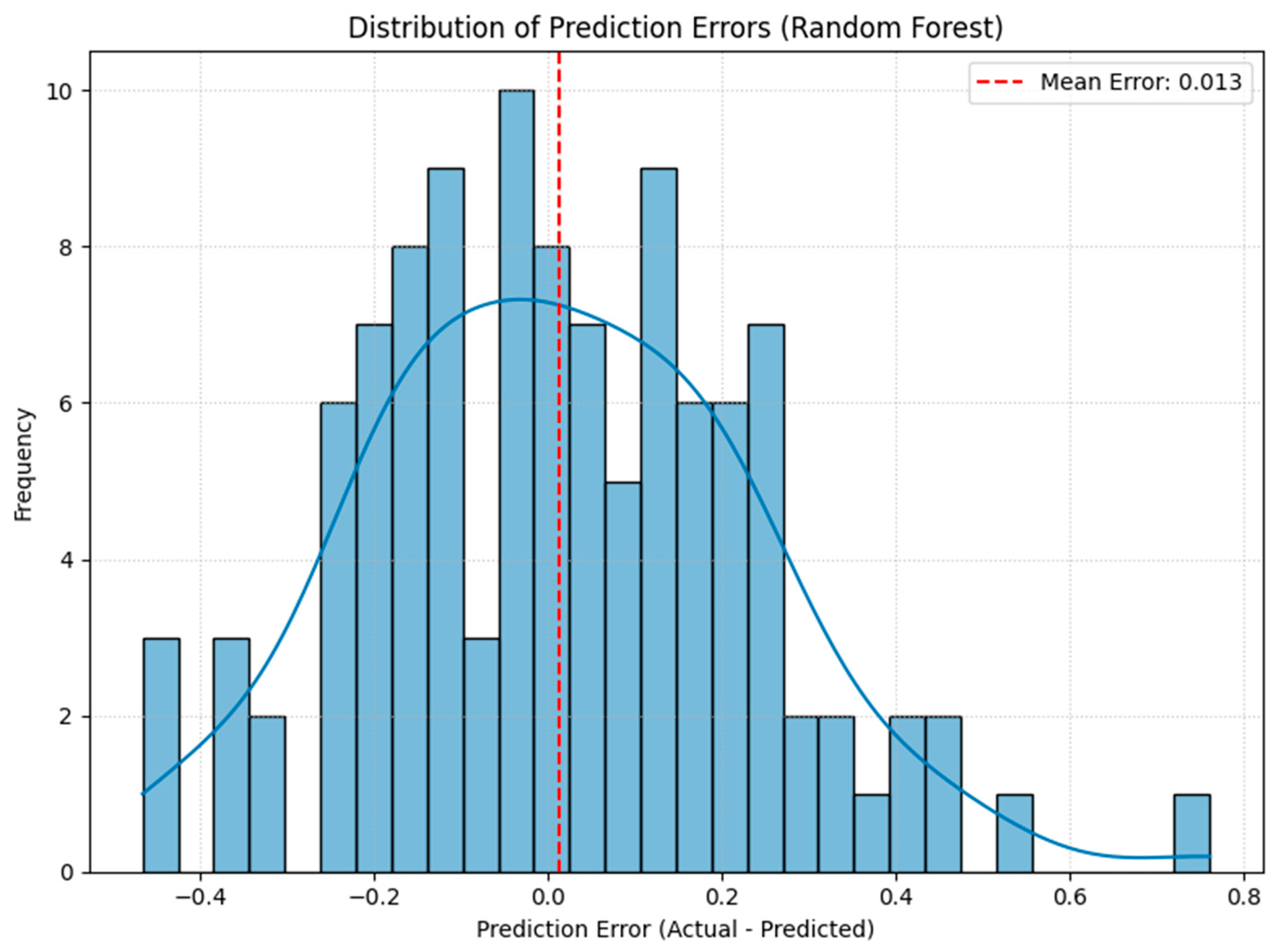

4.4. Machine Learning Model Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results: Research Questions and Global Manufacturing Trends

5.2. Comparison with Literature and Knowledge Contribution

5.3. Theoretical Implications

5.4. Practical Implications for the Global Industrial and Manufacturing Sector

5.5. Limitations of the Study

5.6. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

7. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| CFP | Corporate Financial Performance |

| CMA | Conservative Minus Aggressive (Fama-French Factor) |

| CPS | Cyber-Physical Systems |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FE | Fixed Effects (Panel Model) |

| HML | High Minus Low (Fama-French Factor) |

| HRC | Human-Robot Collaboration |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MES | Manufacturing Execution Systems |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| PdM | Predictive Maintenance |

| PE | Price-to-Earnings (Ratio) |

| R2 | R-squared (Coefficient of Determination) |

| RE | Random Effects (Panel Model) |

| RF | Random Forest (Machine Learning Model) |

| RMW | Robust Minus Weak (Fama-French Factor) |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| RPA | Robotic Process Automation |

| SMB | Small Minus Big (Fama-French Factor) |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| WML | Winners Minus Losers (Momentum Factor) |

| XGB | XGBoost (Machine Learning Model) |

| XR | eXtended Reality |

References

- Wang, M.; Yin, S.; Lian, S. Collaborative elicitation process for sustainable manufacturing: A novel evolution model of green technology innovation path selection of manufacturing enterprises under environmental regulation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomakpo, H.E. ESG Risk Ratings and Stock Performance in Electric Vehicle Manufacturing: A Panel Regression Analysis Using the Fama-French Five-Factor Model. J. Insurance. Bank. Finance. 2025, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg, L.P. Bloomberg Professional Services: Sustainable Finance Solutions. https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/solutions/sustainable-finance/.

- Refinitiv (LSEG). ESG Data. https://www.lseg.com/en/data-analytics/financial-data/company-data/esg-data.

- Gallala, A.; Kumar, A.A.; Hichri, B.; Plapper, P. Digital Twin for Human–Robot Interactions by Means of Industry 4.0 Enabling Technologies. Sensors 2022, 22, 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, K.M.; Mewada, B.G.; Kaur, S.; Khan, A.; Al-Qahtani, M.M.; Qureshi, M.R.N.M. Investigating industry 4.0 technologies in logistics 4.0 usage towards sustainable manufacturing supply chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faheem, M.; Butt, R.A. Big datasets of optical-wireless cyber-physical systems for optimizing manufacturing services in the internet of things-enabled industry 4.0. Data Brief 2022, 42, 108026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Alwis, A.M.L.; De Silva, N.; Samaranayake, P. Industry 4.0-enabled sustainable manufacturing: Current practices, barriers and strategies. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024, 31, 2061–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaithan, A.M.; Alshammakhi, Y.; Mohammed, A.; Mazher, K.M. Integrated Impact of Circular Economy, Industry 4.0, and Lean Manufacturing on Sustainability Performance of Manufacturing Firms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegethoff, T.; Santa, R.; Bucheli, J.M.; Cabrera, B.; Scavarda, A. Navigating Industry 4.0: Leveraging additive technologies for competitive advantage in Colombian aerospace and manufacturing industries. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, T.S.; Xiong, G.; Shen, Z.; Leng, J.; Fang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lodhi, E.; Wang, F.Y. 3D printing in materials manufacturing industry: A realm of Industry 4.0. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelli, C.; Viviani, J.L. Financial performance of socially responsible investing (SRI): What have we learned? A meta-analysis. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it Pay to Be Good? A Meta-Analysis and Redirection of Research on the Relationship between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Johl, S.K. Driving forces for industry 4.0 readiness, sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy capabilities: Does firm size matter? J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 34, 838–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Wong, K.Y.; Butt, S.I. Status of sustainable manufacturing practices: Literature review and trends of triple bottom-line-based sustainability assessment methodologies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43068–43095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wan, Y. Analysis of the factors influencing the sustainable development of the manufacturing industry under the wave of Industry 4.0. Int. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, A.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, M. A Framework to Overcome Blockchain Enabled Sustainable Manufacturing Issues through Circular Economy and Industry 4.0 Measures. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2022, 7, 764–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A. Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. A Survey of Corporate Governance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 737–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hernandez, I.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Lim, S. Teleoperator-Robot-Human Interaction in Manufacturing: Perspectives from Industry, Robot Manufacturers, and Researchers. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 2024, 12, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emma-Ikata, D.; Doyle-Kent, M. Industry 5.0 Readiness–“Optimization of the Relationship between Humans and Robots in Manufacturing Companies in Southeast of Ireland”. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Matin, A.; Islam, R.; Wang, X.; Huo, H.; Xu, G. AIoT for sustainable manufacturing: Overview, challenges, and opportunities. Internet Things 2023, 24, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansare, R.; Yadav, G. Repurposing production operations during COVID-19 pandemic by integrating Industry 4.0 and reconfigurable manufacturing practices: An emerging economy perspective. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 1270–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Wang, X. Human-robot collaboration assembly line balancing considering cross-station tasks and the carbon emissions. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2024, 19, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Khatun, F.; Jahan, I.; Devnath, R.; Bhuiyan, A.A. Cobotics: The Evolving Roles and Prospects of Next-Generation Collaborative Robots in Industry 5.0. J. Robot. 2024, 2024, 2918089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S. IoT and Edge Computing for Smart Manufacturing: Architecture and Future Trends. Int. J. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2024, 13, 26504–26522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.H. Evaluation: Methods for Studying Programs and Policies, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J. Does it Really Pay to Be Green? An Empirical Study of Firm Environmental and Financial Performance. J. Ind. Ecol. 2001, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 1993, 33, 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. A five-factor asset pricing model. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 116, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Financial Outperformance. University of Oxford Working Paper, 2015.

- Sims, C.A. Macroeconomics and Reality. Econometrica 1980, 48, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K.; Otten, R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1751–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. On the foundations of corporate social responsibility. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 853–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from China. Harv. Bus. Sch. Account. Manag. Unit Work. Pap. 2017, No. 11-100. [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Song, X.; Liang, Y. Corporate sustainability performance, stock returns, and ESG indicators: Fresh insights from EU member states. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 87680–87691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 5446–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamisu, M.S.; Paluri, R.A. Emerging trends of environmental social and governance (ESG) disclosure research. Clean. Prod. Letters 2024, 7, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.; Akbar, M.; Yu, X.; Hussain, A.; Svobodová, L. Environmental, social, and governance performance as an influencing factor of financial sustainability: Evidence from the global high-tech sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 4746–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kwok, C.C.Y.; Mishra, D.R. Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 2388–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.; Rutqvist, J. Waste to Wealth: The Circular Economy Advantage; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WBCSD. The Cement Sustainability Initiative: Progress report. World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. https://www.worldcement.com/europe-cis/19062012/cement_csi_wbcsd_report_2012_sustainability_progress/.

- Tian, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Song, X.; Han, J.; Wang, J. Energy Prediction Models and Distributed Analysis of the Grinding Process of Sustainable Manufacturing. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Business Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadekar, R.; Sarkar, B.; Gadekar, A. Model development for assessing inhibitors impacting Industry 4.0 implementation in Indian manufacturing industries: An integrated ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024, 15, 646–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H.A. A Cyber-Physical Systems architecture for Industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Manuf. Letters 2015, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakholia, R.; Suárez-Cetrulo, A.L.; Singh, M.; Carbajo, R.S. Advancing Manufacturing Through Artificial Intelligence: Current Landscape, Perspectives, Best Practices, Challenges, and Future Direction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 131621–131637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chaw, J.K.; Goh, K.M.; Ting, T.T.; Sahrani, S.; Ahmad, M.N.; Kadir, R.A.; Ang, M.C. Systematic Literature Review on Visual Analytics of Predictive Maintenance in the Manufacturing Industry. Sensors 2022, 22, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J.; Lukodono, R.P. Learning performance and physiological feedback-based evaluation for human–robot collaboration. Appl. Ergon. 2025, 124, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shao, H.; Deng, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Comprehensive Survey of the Landscape of Digital Twin Technologies and Their Diverse Applications. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 138, 125–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybalskii, I.; Kruusamäe, K.; Singh, A.K.; Schlund, S. An Augmented Reality Interface for Safer Human-Robot Interaction in Manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaj, O.; Jamshidi, M.; Hassas, P.; Mašek, B.; Štadler, C.; Svoboda, J. Digital Twinning of a Magnetic Forging Holder to Enhance Productivity for Industry 4.0 and Metaverse. Processes 2023, 11, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, A.; Dion, J.L.; Peyret, N.; Renaud, F. Digital twin with augmented state extended Kalman filters for forecasting electric power consumption of industrial production systems. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, P.M.T.; Nurraihan, F. The effectiveness of digital twins in reducing downtime in the manufacturing industry: A literature analysis. Int. J. Mech. Comput. Manuf. Res. 2025, 13, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Manufacturing Industry: A Sustainability Perspective On Cloud And Edge Computing. J. Survey Fish. Sci. 2023, 10, 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, K.; Dec, G.; Stadnicka, D. Possible Applications of Edge Computing in the Manufacturing Industry—Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, Y. HAR2bot: A human-centered augmented reality robot programming method with the awareness of cognitive load. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 1985–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, H.; Askar, S.; Kakamin, A.; Nayla, F. Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Human-Robot Cooperation in the Context of Industry 4.0. Appl. Comput. Sci. 2024, 20, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, E.M.; Nenna, F.; Zanardi, D.; Buodo, G.; Mingardi, M.; Sarlo, M.; Gamberini, L. Understanding workers’ psychological states and physiological responses during human–robot collaboration. Int. J. Human-Computer Studies 2025, 200, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, M.A.; Abdullah, A.H.; Din, G.M.; Faisal, M.; Mudassar, M.; Yasir, A.B. Smart Manufacturing System Using LLM for Human-Robot Collaboration: Applications and Challenges. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2025, 3, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedzielski, B.; Buła, P.; Yang, M. Hyperautomation as a vital optimization tool in organizations: Cognitive approach with the use of Euler circles. J. Electron. Bus. Digit. Econ. 2024, 3, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nick, G.; Zeleny, K.; Kovács, T.; Járvás, T.; Pocsarovszky, K.; Kő, A. Artificial intelligence enriched industry 4.0 readiness in manufacturing: The extended CCMS2.0e maturity model. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2024, 12, 2357683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinthamu, N.; Ashish, A.; Mathiyalagan, P.; Deepa, B.R.; Kannadhasan, S.; Suganya, M. Data Mining Techniques for Predictive Maintenance in Manufacturing Industries a Comprehensive Review. ITM Web Conf., 76 (2025) 05012. [CrossRef]

- Gadekar, R.; Sarkar, B.; Gadekar, A. Key performance indicator based dynamic decision-making framework for sustainable Industry 4.0 implementation risks evaluation: Reference to the Indian manufacturing industries. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 318, 189–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibulski, L.; Schmidt, J.; Aigner, W. Reflections on Visualization Research Projects in the Manufacturing Industry. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2022, 42, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wei, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, K. Edge computing-based proactive control method for industrial product manufacturing quality prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Antonelli, D.; Simeone, A.; Bao, N. Intelligent robot assistants for the integration of neurodiverse operators in manufacturing industry. Procedia CIRP 2024, 126, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.; Cao, H.L.; Imrith, E.; Roshandel, N.; Firouzipouyaei, H.; Burkiewicz, A.; Amighi, M.; Menet, S.; Sisavath, D.W.; Paolillo, A.; et al. Sensor-Enabled Safety Systems for Human–Robot Collaboration: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. IT in manufacturing: Industry 4.0 and beyond. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2025, 15, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, L.A.; Cohen, A.; Ferrell, A. What Matters in Corporate Governance? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 783–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermack, D. Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. J. Financial Economics 1996, 40, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriandani, R.; Winarno, W.A. ESG and firm performance: The role of digitalization. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Investasi 2023, 24, 993–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ti, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, H.H. Blessing or Curse? The Impact of the Penetration of Industrial Robots on Green Sustainable Transformation in Chinese High-Energy-Consuming Industries. Energies 2025, 18, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.M. Does real earnings management affect a firm's environmental, social, and governance (ESG), financial performance, and total value? A moderated mediation analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 28239–28268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhcfr. [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren, S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.A. Estimating Standard Errors in Finance Panel Data Sets: Comparing Approaches. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 435–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.A. Macroeconomics and Reality. Econometrica 1980, 48, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juškaitė, L.; Tamošiūnienė, R. Cryptocurrencies investing trends in the context of Environmental, Social and Governance. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1429, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Statistic | P-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-test (Entity FE vs Pooled) | 0.68 | 0.935 | FE not sig or N/A |

| Hausman (Informal) | Comparison | FE: -0.004, RE: -0.002 | If F-test sig, FE preferred |

| Breusch-Pagan (Entity FE resids) | 4.5 | 0.876 | Homoskedasticity |

| IV_Tested | Model_Type | Coefficient | P-Value | N_Obs | Significant_5pct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board_Size | FE_TwoWay | 0.0018 | 0.0019 | 438 | TRUE |

| Injury_rate | FE_TwoWay | -0.0077 | 0.1593 | 438 | FALSE |

| Water_recycle | FE_TwoWay | 0 | 0.2977 | 438 | FALSE |

| Env_Score | FE_TwoWay | -0.0014 | 0.3362 | 438 | FALSE |

| Turnover_empl | FE_TwoWay | -0.0048 | 0.3417 | 438 | FALSE |

| Women_Employees | FE_TwoWay | -0.003 | 0.3971 | 438 | FALSE |

| ESG_Score | FE_TwoWay | -0.0018 | 0.4101 | 438 | FALSE |

| Social_Score | FE_TwoWay | -0.0013 | 0.4791 | 438 | FALSE |

| Water_use | FE_TwoWay | 0 | 0.6804 | 438 | FALSE |

| CO2_emissions | FE_TwoWay | 0 | 0.6862 | 438 | FALSE |

| Energy_use | FE_TwoWay | 0 | 0.7146 | 438 | FALSE |

| Gov_Score | FE_TwoWay | 0.0003 | 0.7275 | 438 | FALSE |

| Variable | Parameter | Std. Err. | T-stat | P-value | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| const | 0.016 | 0.2514 | 0.0636 | 0.9493 | -0.4781 | 0.5101 |

| MKT_RF | 1.4243 | 0.1284 | 11.095 | 0 | 1.172 | 1.6767 |

| SMB | 0.3261 | 0.2387 | 1.366 | 0.1727 | -0.1432 | 0.7954 |

| HML | -0.4709 | 0.2926 | -1.6097 | 0.1082 | -1.046 | 0.1041 |

| RMW | -0.4898 | 0.3797 | -1.2898 | 0.1978 | -1.2362 | 0.2566 |

| CMA | 1.3336 | 0.4765 | 2.7985 | 0.0054 | 0.3969 | 2.2703 |

| WML | -0.271 | 0.1231 | -2.2006 | 0.0283 | -0.513 | -0.0289 |

| Log_Market_cap | 0.0694 | 0.0214 | 3.2394 | 0.0013 | 0.0273 | 0.1115 |

| Log_Total_assets | -0.0718 | 0.0198 | -3.6177 | 0.0003 | -0.1108 | -0.0328 |

| FNCL_LVRG | 1.068E-06 | 0.0001 | 0.0102 | 0.9919 | -0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| RETURN_ON_ASSET | 0.0024 | 0.0045 | 0.5327 | 0.5945 | -0.0065 | 0.0113 |

| PE_RATIO | 0.0013 | 0.001 | 1.2698 | 0.2049 | -0.0007 | 0.0032 |

| ASSET_GROWTH | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 1.6504 | 0.0996 | -8.66E-05 | 0.001 |

| Log_BVPS | -0.0064 | 0.016 | -0.3997 | 0.6896 | -0.0379 | 0.0251 |

| QUICK_RATIO | 0.0046 | 0.0161 | 0.2844 | 0.7762 | -0.0271 | 0.0363 |

| RiskCat_High | 0.045 | 0.0253 | 1.7771 | 0.0763 | -0.0048 | 0.0948 |

| RiskCat_Medium | 0.007 | 0.0224 | 0.3132 | 0.7543 | -0.0371 | 0.0511 |

| Model | MSE | R2 |

| Random Forest | 0.0487 | 0.3005 |

| XGBoost | 0.0499 | 0.2835 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).