Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Livelihood of local people

Social and ritual values

Socio economic development

Medicinal value and traditional health care

2. Material and Methods

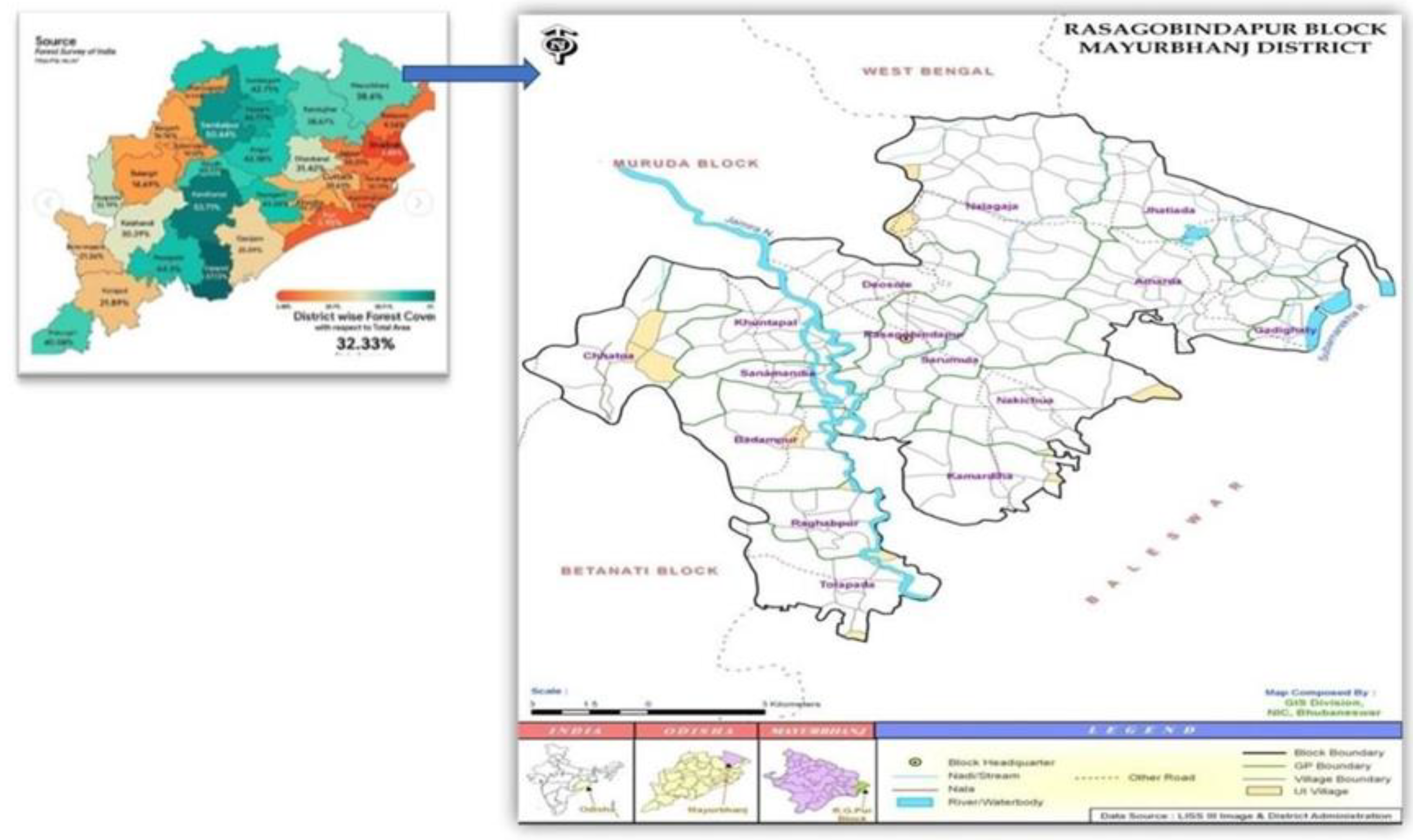

Study Area

Data collection

3. Results

Collection, processing and marketing of some major NTFPS

Sal leaf

Kendu leaves

Sal seed

Kochila seeds

Karanja seeds

Mahula flower

Kusuma seeds

Tentuli

Sabai grass

Bamboo

Cane

Marketing

Issues and Challenges for marketing of NTFPs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Aakruti, A. K., Swati, R. D., & Vilasrao, J. K. (2013). Overview of Indian medicinal tree: Bambusa bambos (Druce). Int. Res. J. Pharm, 4, 52-56.

- Adepoju AA, Sheu SA. Economic valuation of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) [online]; 2007. Available:https://mpra.ub.uni-Muenchen.de/2689/.

- Adepoju, A. A., & Salau, A. S. (2007). Economic valuation of non-timber forest products (NTFPs).

- Ahenkan, A., & Boon, E. (2011). Non-timber forest products (NTFPs): Clearing the confusion in semantics. Journal of Human Ecology, 33(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I., Kumar, D., & Patel, H. (2021). Computational investigation of phytochemicals from Withania somnifera (Indian ginseng/ashwagandha) as plausible inhibitors of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors. Journal of biomolecular structure and dynamics, 40(17), 7991-8003. [CrossRef]

- Al Rashid, M. H., Mandal, V., Mandal, S. C., & Amirthalingam, R. (2017). Diospyros melanoxylon roxb in cancer prevention: pharmacological screening, pharmacokinetics and clinical studies. International Journal of Pharmacognosy, 4(7): 217-223.

- Al-Snafi, A. E. (2017). Anticancer effects of Arabian medicinal plants (part 1)-A review. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy, 7(4), 63-102. [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A., & Gopi, S. (2017). Medicinal properties of Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.) Wight & Arn.: a review. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine, 7(1), 6578.

- Anwar, W.S., Abdel-maksoud, F.M., Sayed, A.M., Abdel-Rahman, A. M., Makboul, M.A., & Zaher, A. M. (2023). Potent hepatoprotective activity of common rattan (Calamus rotang L.) leaf extract and its molecular mechanism. BMC Complement Med Ther,23.

- Arote, S. R., & Yeole, P. G. (2010). Pongamia pinnata L: a comprehensive review. International Journal of PharmTech Research, 2(4), 2283-2290.

- Ashokkumar, K. (2015). Gloriosa superba (L.): a brief review of its phytochemical properties and pharmacology. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res, 7(6), 1190-3.

- Ayyanar, M., & Subash-Babu, P. (2012). Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels: A review of its phytochemical constituents and traditional uses. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine, 2(3), 240-246. [CrossRef]

- Bahorun, T., Neergheen, V.S., & Aruoma, O. I. (2005). Phytochemical constituents of Cassia fistula. African Journal of Biotechnology ,4 (13), 1530-1540. [CrossRef]

- Bahuguna, V. K. (2000). Forests in the economy of the rural poor: an estimation of the dependency level. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 29(3), 126-129.

- Baliga, M. S., Bhat, H. P., Joseph, N., & Fazal, F. (2011). Phytochemistry and medicinal uses of the bael fruit (Aegle marmelos Correa): A concise review. Food Research International, 44(7), 1768-1775. [CrossRef]

- Balkrishna, A., Chauhan, M., Dabas, A., & Arya, V. (2022). A Comprehensive Insight into the Phytochemical, Pharmacological Potential, and Traditional Medicinal Uses of Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Balraju, W., Dinesha, S., Patil, G., Pradhan, D., Arshad, A., & Tripathi, S. K. (2023). Socio- economic drivers for the collection of Tendu leaves, a case study from Katghora Forest Division, Chhattisgarh, India.

- Batiha, G. E. S., Akhtar, N., Alsayegh, A. A., Abusudah, W. F., Almohmadi, N. H., Shaheen, H. M., ... & De Waard, M. (2022). Bioactive compounds, pharmacological actions, and pharmacokinetics of genus Acacia. Molecules, 27(21), 7340. 21.

- Bhadoriya, S. S., Ganeshpurkar, A., Narwaria, J., Rai, G., & Jain, A. P. (2011). Tamarindus indica: Extent of explored potential. Pharmacognosy reviews, 5(9), 73.

- Bharathi, T. N., Girish, M., Girish, M. R., & Jayaram, M. S. (2022). An Economic Analysis of Production and Marketing of Tamarind in Srinivasapura Taluk of Kolar District, Karnataka. Mysore Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 56(4).

- Bhati, R., Singh, A., Saharan, V. A., Ram, V., & Bhandari, A. (2012). Strychnos nuxvomica seeds: Pharmacognostical standardization, extraction, and antidiabetic activity. Journal of Ayurveda and integrative medicine, 3(2), 80.

- Bhatia, H., Kaur, J., Nandi, S., Gurnani, V., Chowdhury, A., Reddy, P. H., ... & Rathi, B. (2013). A review on Schleichera oleosa: Pharmacological and environmental aspects. journal of pharmacy research, 6(1), 224-229. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P., & Hayat, S. F. (2004). Sustainable NTFP management for rural development: a case from Madhya Pradesh, India. International Forestry Review, 6(2), 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P., & Prasad, R. (2001). Integrated options for forest management in India. Victor, M. and Barash, A, 49-57.

- Bhattacharya, P., Prasad, R., Bhattacharyya, R., & Asokan, A. (2008). Towards certification of wild medicinal and aromatic plants in four Indian states. Unasylva, 59(230), 35- 44.

- Brintha, S., Rajesh, S., Renuka, R., Santhanakrishnan, V. P., & Gnanam, R. (2017). Phytochemical analysis and bioactivity prediction of compounds in methanolic extracts of Curculigo orchioides Gaertn. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 6(4), 192-197.

- Butt, S. Z., Hussain, S., Munawar, K. S., Tajammal, A., & Muazzam, M. A. (2021). Phytochemistry of Ziziphus Mauritiana; its nutritional and pharmaceutical potential. Scientific Inquiry and Review, 5(2), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B. M., & Luckert, M. K. (Eds.). (2002). Uncovering the hidden harvest: valuation methods for woodland and forest resources. Earthscan.

- Chahal, K. K., Bhardwaj, U., Kaushal, S., & Sandhu, A. K. (2015). Chemical composition and biological properties of Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty syn. Vetiveria zizanioides (L.) Nash-A Review.

- Chamariya, R., Raheja, R., Suvarna, V., & Bhandare, R. (2022). A critical review on phytopharmacology, spectral and computational analysis of phytoconstituents from Streblus asper Lour. Phytomedicine Plus, 2(1), 100177. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, P. K., Prajapati, R. K., & Dhurwe, R. K. (2018). Documentation of traditional collection methods of different NTFPs in Dhamtari forest area. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 7(1), 1531-1536.

- Charanraj, N., Venkateswararao, P., Vasudha, B., & Narender, B. (2019). Phytopharmacology of Chloroxylon swietenia: a review. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, 9(1), 273-278. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, K. V. S., Sharma, A. K., & Kumar, R. (2008). Non-timber forest products subsistence and commercial uses: trends and future demands. International Forestry Review, 10(2), 201-216. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Dai, X., Liu, Y., Yang, Y., Yuan, L., He, X., & Gong, G. (2022). Solanum nigrum Linn.: an insight into current research on traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 918071. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, K. (1993). The value of non-timber forest products: an estimation for tropical deciduous forests in India. Economic botany, 47, 251-257. [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, H. S., Swarnakar, G., & Jogpal, B. (2021). Medicinal properties of Ricinus communis: A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 12(7), 3632-3642.

- Dalvi, T. S., Kumbhar, U. J., & Shah, N. (2022). Madhuca longifolia: ethanobotanical, phytochemical studies, pharmacological aspects with future prospects. IJABS, 2, 1- 9.

- Das, D., & Sahoo, M. K. (2023). Fostering Sustainable Growth: Evaluating Financing Strategies for Tamarind Value Chains in Rayagada District of Odisha.

- Dash SR, Karjee PK, Patra B, Bal R, Kar A.2024. Chemical constituent, essential oil and biological activities of different species of lamiaceae and their effect on human health. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 27 (3): 5361-5370.

- Dattagupta, Shovan, and Abhik Gupta. “Traditional processing of non-timber forest products in Cachar, Assam, India.” (2014).

- Deep SK, Patra B, Baral A, Nayak Y, Pradhan SN (2022). Impact of global climate change on extremophilic diversity. Journal of east china university of science and technology. 65 (3): 842-853. [CrossRef]

- Deep SK, Patra B, Mohanta AK, Ekka RK, Sethi BK, Behera PK, Pradhan SN. 2023. Role of Critical contaminants in ground water of Kalahandi district of Odisha and their health risk assessment. Ann. For. Res. 66(1): 3963-3981.

- Deora, S. L., & Khadabadi, S.S. (2009). Screening of antistress properties of Chlophytum borivilianum tuber. Pharmacologyonline, 1,320-328.

- Dev, L. R., Anurag, M., & Rajiv, G. (2010). Oroxylum indicum: A review. Pharmacognosy Journal, 2(9), 304-310. [CrossRef]

- Dey, A., Kumar, H., & Das, S.(2022). Significance of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) to the Tribal Wealth of Ranchi District, Jharkhand. Eco. Env. & Cons. 28 (4). [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, A. K., Chopra, B., & Mittal, S. K. (2013). Martynia annua L.: a review on its ethnobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Journal of pharmacognosy and phytochemistry, 1(6), 135-140.

- Dransfield, J. (1982). Notes on rattans (Palmae: Lepidocaryoideae) occurring in Sabah, Borneo. Kew Bulletin, 783-815. [CrossRef]

- ElSohly, M. A., Radwan, M. M., Gul, W., Chandra, S., & Galal, A. (2017). Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Progress in the chemistry of organic natural products, 103, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Farzana, M. U. Z. N., & Al Tharique, I. (2014). A review of ethnomedicine, phytochemical and pharmacological activities of Acacia nilotica (Linn) willd. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 3(1), 84-90.

- Félix-Silva, J. Félix-Silva, J., Giordani, R. B., Silva-Jr, A. A. D., Zucolotto, S. M., & FernandesPedrosa, M. D. F. (2014). Jatropha gossypiifolia L.(Euphorbiaceae): a review of traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of this medicinal plant. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014.

- Gadgil, M. (2003). India’s Biological Diversity Act 2002: An act for the new millenium. [CrossRef]

- Gaire, B. P., & Subedi, L. (2014). Phytochemistry, pharmacology and medicinal properties of Phyllanthus emblica Linn. Chinese journal of integrative medicine, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Gauraha, A. K. (1992). Micro-economic analysis of a tribal village. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 47(3), 446-447.

- Ghosal, S. (2011). Importance of non-timber forest products in native household economy. Journal of Geography and Regional planning, 4(3), 159.

- Gochhi SK, Patra B, Dey SK. 2023.comparative study of bioactive components of betel leaf essential oil using GCMS analysis. Gradiva review journal. 9(9): 08-20.

- Greeshma, M., Manoj, G. S., & Murugan, K. (2017). Phytochemical analysis of leaves of teak (tectona grandis lf) by gc ms. Kongunadu Research Journal, 4(1), 75-78. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R., Wang, T., Zhou, G., Xu, M., Yu, X., Zhang, X., ... & Wang, Z. (2018). Botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicity of Strychnos nux-vomica L.: a review. The American journal of Chinese medicine, 46(01), 1-23.

- Gupta, A. K., Sharma, M. L., & Singh, L. (2017). Utilization pattern of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) among the tribal population of Chhattisgarh, India. International Journal of Bio-resource and Stress Management, 8(Apr, 2), 327-333. [CrossRef]

- Haldhar, R., Prasad, D., & Bhardwaj, N. (2019). Surface adsorption and corrosion resistance performance of Acacia concinna pod extract: An efficient inhibitor for mild steel in acidic environment. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 45(1), 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. A., & Quli, S. M. S. (2017). The role of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) in tribal economy of Jharkhand, India. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 6(10), 2184-2195. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. A., Quli, S. M. S., Sofi, P. A., Bhat, G. M., & Malik, A. R. (2015). Livelihood dependency of indigenous people on forest in Jharkhand, India. Vegetos, 28(3), 106- 118. [CrossRef]

- Jena, P. K., (2019). Economic Role of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) in the Livelihood of Scheduled Tribes in Similipal Area of Mayurbhanj District of Odisha. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 8(2), 01-09.

- Jerin, V. A. Jerin, V. A., Lazarus, T. P., Gopakumar, S., Durga, A. R., Nishan, M. A., & Gopinath, P. P. (2022). Role of Non-Timber Forest Products in Income Generation of the Tribal Population: A Review. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 40(11), 285-294. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. S., Agarwal, R. K., & Agarwal, A. (2013). Non-timber forest products as a source of livelihood option for forest dwellers: role of society, herbal industries and government agencies. Current Science, 104(4), 440-443.

- Johnson, T. S., Agarwal, R. K., & Agarwal, A. (2013). Non-timber forest products as a source of livelihood option for forest dwellers: role of society, herbal industries and government agencies. Current Science, 104(4), 440-443.

- Journal of Biosciences, 28(2), 145-147.

- Kala, C.P. 2011. Indigenous uses and sustainable harvesting of trees by local people in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve of India. Int. J. Med. Arom. Plants, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 153-161.

- Kandari, L. S., Gharai, A. K., Negi, T., & Phondani, P. C. (2012). Ethnobotanical Knowledge of Medicinal Plants among Tribal Communities in Orissa. India. J Forest Res Open Access, 1(104), 2.

- Kauser, A. S., Hasan, A., Parrey, S. A., Ahmad, W., & Ethnobotanical, P. (2016). Pharmacological Properties of Saraca asoca Bark: A Review. European J. Pharmaceut. Med. Res, 3, 274-279.

- Khemka A, Patra B, Pradhan SN (2020) Revisiting the migrants health and prosperity in Odisha: A sustainable perspective. Covid 19, Migration and sustainable development. ISBN 978-93-89224-65-8, Kunal book publishers and distributors. Editors: Sudhakar Patra, Kabita Kumari Sahu, Shakuntala Pratihary, Ambika Prasad Nanda.

- Kumar, V., & Van Staden, J. (2016). A review of Swertia chirayita (Gentianaceae) as a traditional medicinal plant. Frontiers in pharmacology, 6, 173604.

- Kumari, M., Radha, Kumar, M., Zhang, B., Amarowicz, R., Puri, S., ... & Lorenzo, J. M. (2022). Acacia catechu (Lf) Willd.: a review on bioactive compounds and their health promoting functionalities. Plants, 11(22), 3091.

- Kumari, S., Bhatt, V., Suresh, P. S., & Sharma, U. (2021). Cissampelos pareira L.: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 274, 113850.

- Mahanto R, Behera D, Patra B, Das S, Lakra K, Pradhan SN, Abbas A, Ali SK .2024. Plant based natural products in cancer therapeutics. Journal of drug Targeting. [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A. K., Albers, H. J., & Robinson, E. J. (2005). The impact of NTFP sales on rural households’ cash income in India’s dry deciduous forest. Environmental Management, 35(3), 258-265.

- Maikhuri, R. K., Nautiyal, S., Rao, K. S., & Saxena, K. G. (1998). Role of medicinal plants in the traditional health care system: a case study from Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve. Current Science, 152-157.

- Malhotra, K. C., Debal Deb, D. D., Dutta, M., Vasulu, T. S., Yadav, G., & Adhikari, M. (1993). The role of non-timber forest products in village economies of south-west Bengal.

- Mallik, R. M. (2000). Sustainable management of non-timber forest products in Orissa: Some issues and options. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 55(3), 384397.

- Mishra, M., Kotwal, P. C., & Prasad, C. (2009). Harvesting of medicinal plants in the forest of Central India and its impact on quality of raw materials: a case of Nagpur District, India. Ecoprint: An International Journal of Ecology, 16, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Modi, A., Mishra, V., Bhatt, A., Jain, A., Mansoori, M. H., Gurnany, E., & Kumar, V. (2016). Delonix regia: historic perspectives and modern phytochemical and pharmacological researches. Chinese journal of natural medicines, 14(1), 31-39.

- Mohanta AK, Patra B, Sahoo C (2022) Practice and Challenges for municipal solid waste management in Balasore district, Odisha. Chinese Journal of geotechnical Engineering. 44(11): 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta AK, Sahoo C, Jena R, Sahoo S, Bishoyi SK, Patra B, Dash SR, Pradhan B. 2024. Effect of inappropriate solid waste on microplastic contamination in Balasore district and its aquatic environment. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 120 (48), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta YK, Biswas K, Mishra AK, Patra B, Mishra B, Panda J, Avula SK, Varma RS, Panda BP, Nayak D.2024. Amelioration of gold nanoparticles mediated through Ocimum oil extracts induces reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial instability against MCF-7 breast carcinoma. Royal society of Chemistry. 14, 27816-27830. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta YK, Mishra AK, Nayak D, Patra B, Bratovcic A, Avula SK, Mohanta TK, Murugan K, Saravanan M (2022) Exploring dose dependent cytotoxicity profile of Gracilaria edulis mediated green synthesized silver nanoparticles against MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 3863138. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, AK, Patra B, Deep SK, Ali AKI, Pradhan SN, Sahoo C. (2022) Recent advancements in utilization of municipal solid waste for the invention of bioproducts: the framework for low income countries. Journal of east china university of science and technology. 65 (3): 422-465. [CrossRef]

- Moura, J. D. S., Sousa, R. P. E., Martins, L. H. D. S., Costa, C. E. F. D., Chisté, R. C., & Lopes, A. S. (2023). Thermal Degradation of Carotenoids from Jambu Leaves (Acmella oleracea) during Convective Drying. Foods, 12(7), 1452. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, I. K., Bhat, P. R., Ravindranath, N. H., & Sukumar, R. (2005). Financial valuation of non-timber forest product flows in Uttara Kannada district, Western Ghats, Karnataka. Current Science, 1573-1579.

- Murugesu, S., Selamat, J., & Perumal, V. (2021). Phytochemistry, pharmacological properties, and recent applications of Ficus benghalensis and Ficus religiosa. Plants, 10(12), 2749.

- Neha, B., Honey, J., Ranjan, B., & Mukesh, B. (2012). Pharmacognostical and preliminary phytochemical investigation of Acorus calamus linn. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 2(1), 39-42.

- Okhale, S. E., & EM, N. (2016). Abrus precatorius Linn (Fabaceae): phytochemistry, ethnomedicinal uses, ethnopharmacology and pharmacological activities. Int J Pharm Sci Res, 1, 37-43.

- Pande, V. C., Kurothe, R. S., Rao, B. K., Kumar, G., Parandiyal, A. K., Singh, A. K., & Kumar, A. (2012). Economic analysis of bamboo plantation in three major ravine systems of India §. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 25(1), 49-59.

- Pandey, A. K., Tripathi, Y. C., & Kumar, A. (2016). Non timber forest products (NTFPs) for sustained livelihood: Challenges and strategies. Research Journal of Forestry,10(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S., Meher, D., & Siri, P. (2019). Reliance and livelihood significance of nontimber forest products available in Odisha: A review. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 8(1), 2428-2432.

- Patra B, Gautam R, Priyadarsini E, Paulraj R, Pradhan SN, Muthupandian S, Meena R (2019). Piper betle: Augmented synthesis of gold nanoparticles and its invitro cytotoxicity assessment on HeLa and HEK293 cells. Journal of Cluster Science. 31:133-145. [CrossRef]

- Patra B & Dey SK (2016). A Review on Piper betle L. Journal of Medicinal plants Studies. 4(6): 185-192.

- Patra B (2015). Labanyagada: The Protected red sandal forest of Gajapati district, Odisha, India. International Journal of Herbal Medicine. 3(4): 35-40 [E-ISSN:2321-2187 P-ISSN:2394-0514]. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Behera SK, Biswal AK. 2025. Drug discovery from traditional phytotheraphy. Qeios. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Das MT, Pradhan SN, Dash SR, Bhuyan PP, Pradhan B. 2025. Ferrochrome pollution and its consequences on groundwater ecosystem and public health. Limnological Review. 25: 23. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Das N, Shamim MZ, Mohanta TK, Mishra B, Mohanta YK. (2023) Dietary natural polyphenols against bacterial and fungal infections: An emerging gravity in health care and food industry. Bioprospecting of tropical medicinal plants. Springer nature. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Deep S, Pradhan SN. (2021) Different Bioremediation Techniques for Management of Waste Water: An overview. Recent Advancements in Bioremediation of Metal Contaminants. IGI Global publishing house. ISBN13: 9781799848882, ISBN10: 1799848884, EISBN13: 9781799848899. https://www.igi-global.com/book/recent-advancements-bioremediation-metal-contaminants/244607(Taylor Francis group), Editors: Satarupa Dey, Biswaranjan Acharya. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Deep SK, Rosalin R, Pradhan SN (2022). Flavored food additives on leaves of piper betle L.: A human health perspective. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Dey SK & Das MT (2015). Forest management practices for conservation of Biodiversity: An Indian Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Biology. 5 (4): 93-98.

- Patra B, Gautam R, Das MT, Pradhan SN, Dash SR, Mohanta AK. 2024. Microplastics associated contaminants from disposable paper cups and their consequence on human health. Labmed Discovery. 1(2), 100029. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Meena R, Rosalin R, Singh M, Paulraj R, Ekka RK, Pradhan SN (2022). Untargeted metabolomics in piper betle leaf extracts to discriminate the cultivars of coastal odisha, India. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Pal R, Paulraj R, Pradhan SN, Meena R. (2020) Minerological composition and carbon content of soil and water amongst Betel vineyards of coastal Odisha, India. SN Applied Sciences. 2: 998.

- Patra B, Paulraj R, Muthupandian S, Meena R, Pradhan SN (2021). Modern Nanomaterials Extraction and Characterisation Techniques in plant samples and their biomedical potential. Handbook of Research on Nano-Strategies for Combatting Antimicrobial Resistance and Cancer. Pages 400, ISBN13: 9781799850496, ISBN10: 1799850498, EISBN13: 9781799850502. (Taylor Francis group). https://www.igi-global.com/book/nano-strategies-combatting-antimicrobial-resistance/244660IGI Global publishing house. Editors: Muthupandian Saravanan (Mekelle University, Ethiopia), Venkatraman Gopinath (University of Malaya, Malaysia) and Karthik Deekonda (Monash University, Malaysia). [CrossRef]

- Patra B, PP Mohanty, Biswal AK . 2025. Improved Seed Germination Technique for Prosopis Cineraria (L.) Druce: A Rare Sacred Plant of Hindus. Qeios, 2632-3834.

- Patra B, Pradhan SN (2018). A Study on Socio-economic aspects of Betel Vine Cultivation of Bhogarai area of Balasore District, Odisha. Journal of Experimental Science. 9: 13-17 [ISSN: 2218-1768]. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Pradhan SN (2023) Contamination of Honey: A Human Health Perspective. Health Risks of food additives – Recent developments and Trends in Food Sector (ISBN 978-1-83768-189-1) Intechopen Publishers.

- Patra B, Pradhan SN, Das MT & Dey SK (2018). Eco-physiological Evaluation of the Betel Vine Varieties Cultivated in Bhogarai area of Balasore District, Odisha, India for disease management and increasing crop yield. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research. 9(4): 25822-25828 [ISSN: 0976-3031]. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Pradhan SN, Paulraj R. (2024) Strategic Urban Air Quality Improvement: Perspectives on public health. Air quality and human health. Springer nature. In: Padhy, P.K., Niyogi, S., Patra, P.K., Hecker, M. (eds) Air Quality and Human Health. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Sahu A, Meena R, Pradhan SN (2021) Estimation of genetic diversity in piper betle L. Based on the analysis of morphological and molecular markers. Letters in Applied NonoBioScience. 10(2): 2240-2250.

- Patra B, Sahu D & Misra MK (2014). Ethno-medicobotanical studies of Mohana area of Gajapati district, Odisha. India. International Journal of Herbal Medicine.2(4): 40-45. (IF:2.6). [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, A., Sarkar, R., Sharma, A., Yadav, K. K., Kumar, A., Roy, P., Mazumder, A., Karmakar, S., & Sen, T. (2013). Pharmacological studies on Buchanania lanzan Spreng.- a focus on wound healing with particular reference to anti-biofilm properties. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine, 3(12), 967–974.

- Puri B. K. (2018). Editorial: The Potential Medicinal Uses of Cassia tora Linn Leaf and Seed Extracts. Reviews on recent clinical trials, 13(1), 3–4. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S., Mujahid, M. D., Siddiqui, M. A., Rahman, M. A., Arif, M., Eram, S., ... & Azeemuddin, M. D. (2018). Ethnobotanical uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Pterocarpus marsupium: a review. Pharmacognosy Journal, 10(6s). [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, K., Varakumar, P., Baliwada, A., & Byran, G. (2020). Activity of phytochemical constituents of Curcuma longa (turmeric) and Andrographis paniculata against coronavirus (COVID-19): an in silico approach. Future journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 6, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ram, P., Shukla, P. K., & Pratibhar, B. (1996). Leaves from the forest: a case study of Diospyros melanoxylon (tendu leaves) in Madhya Pradesh. Leaves from the forest: a case study of Diospyros melanoxylon (tendu leaves) in Madhya Pradesh.

- Rastogi, S., Kulshreshtha, D. K., & Rawat, A. K. S. (2006). Streblus asper Lour.(Shakhotaka): a review of its chemical, pharmacological and ethnomedicinal properties. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 3, 217-222.

- Ravi, A., & Oommen, P. S. (2012). Phytochemical characterization of Holigarna arnottiana Hook. F. J Pharm Res, 5(6), 3202-3203.

- Renuka, C. (2007). Status of rattan resources and uses in South Asia. Rattan: Current Research Issues And Prospects For Conservation And Sustainable Development Fao, 101.

- Rutuja, R. S., Shivsharan, U., & Shruti, A. M. (2015). Ficus religiosa (Peepal): A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Interantional Journal of Pharmaceutical and Chemical Sciences, 4, 360-370.

- Sahoo, M., Nayak, H., & Mohanty, T. L. (2019). Role of socio-economic variables and non- timber forest products on the livelihood dependency of forest fringe communities in Khordha forest division, Odisha. Odisha, e-planet17, 2, 127-133.

- Sahoo, S. R., Panda, N. K., Subudhi, S. N., & Das, H. K. (2020). Contribution of nontimber forest produces (NTFPs) in the socio-economic development of forest dwellers in Odisha. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 9(4S), 81-85.

- Saklani, S., Rawat, Y., Plygun, S., Shariati, M. A., Nigam, M., Maurya, V. K., ... & Mishra, A. P. (2019). Biological activity and preliminary phytochemical screening of Terminalia Alata Heyne Ex Roth. Journal of microbiology, biotechnology and food Sciences, 8(4), 1010-1015. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B., Gültekin-Özgüven, M., Kırkın, C., Özçelik, B., Morais-Braga, M. F. B., Carneiro, J. N. P., Bezerra, C. F., Silva, T. G. D., Coutinho, H. D. M., Amina, B., Armstrong, L., Selamoglu, Z., Sevindik, M., Yousaf, Z., Sharifi-Rad, J., Muddathir, A. M., Devkota, H. P., Martorell, M., Jugran, A. K., Martins, N., Cho, W. C. (2019). Anacardium Plants: Chemical,Nutritional Composition and Biotechnological Applications. Biomolecules, 9(9), 465. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. K., & Chatopadhyay, R. N. (2006). Sal leaves—The source of poor man’s income and employment. Journal of Non-Timber Forest Products, 13(1), 9-15.

- Sasi, S., Anjum, N., & Tripathi, Y. C. (2018). Ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of Flacourtia jangomas: a review. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S., KP, S. K., Das S, K., Nair J, H. (2021). Caesalpinia bonduc: A Ubiquitous yet Remarkable Tropical Plant Owing Various Promising Pharmacological and Medicinal Properties with Special References to the Seed. Medicinal & Aromatic Plants, 10(7), 394.

- Satpathy, S. K. (2018). Mahua Flowers and Seeds: A Livelihood strategy of tribal’s in Mayurbhanj district of Odisha, India. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, 23(6), 6-11.

- Sekar, C., Rai, R. V., & Ramasamy, C. (1996). Role of minor forest products in tribal economy of India: a case study. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 280-288.

- Selim, M. A., El-Askary, H. I., Sanad, O. A., Ahmed, M. N., & Sleem, A. A. (2006). Phytochemical and pharmacological study of pterospermum acerifolium Willd. growing in Egypt. Bull. Fac. Pharm, 44, 119-123.

- Semalty, M., Semalty, A., Badola, A., Joshi, G. P., & Rawat, M. S. M. (2010). Semecarpus anacardium Linn.: a review. Pharmacognosy reviews, 4(7), 88. [CrossRef]

- Shaanker, R. U., Ganeshaiah, K. N., Krishnan, S., Ramya, R., Meera, C., Aravind, N. A., & Reddy, B. C. (2004). Livelihood gains and ecological costs of non-timber forest product dependence: assessing the roles of dependence, ecological knowledge and market structure in three contrasting human and ecological settings in south India. Environmental Conservation, 31(3), 242-253. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. S., Shah, S. S., Iqbal, A., Ahmed, S., Khan, W. M., Hussain, S., & Li, Z. (2018). Report: Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activities of red silk cotton tree (Bombax ceiba L.). Pakistan journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 31(3), 947– 952.

- Shamsuddin, T., Alam, M. S., Junaid, M., Akter, R., Hosen, S. M., Ferdousy, S., & Mouri, N. J. (2021). Adhatoda vasica (Nees.): A review on its botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and toxicity. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry, 21(14), 1925-1964.

- Sharma, S., & Arora, S. (2015). Phytochemicals and pharmaceutical potential of Delonix regia (bojer ex Hook) Raf a review. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, 7(8), 17-29.

- Sheba, L. A., & Anuradha, V. (2019). An updated review on Couroupita guianensis Aubl: a sacred plant of India with myriad medicinal properties. Journal of Herbmed Pharmacology, 9(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Shravya, S., Vinod, B. N., & Sunil, C. (2017). Pharmacological and phytochemical studies of Alangium salvifolium Wang. – A review. Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, 55, 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, R. K., Upma, K. A., & Arora, S. (2010). Santalum album linn: a review on morphology, phytochemistry and pharmacological aspects. International Journal of PharmTech Research, 2(1), 914-919.

- Singh, L., kumar, A., Choudhary, A., & Singh, G. (2018). Asparagus racemosus: The plant with immense medicinal potential. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 7(3), 2199-2203.

- Singh, M. K., Khare, G., Iyer, S. K., Sharwan, G., & Tripathi, D. K. (2012). Clerodendrum serratum: A clinical approach. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, (Issue), 11-15.

- Sinha, S., Sharma, A., Reddy, P. H., Rathi, B., Prasad, N. V. S. R. K., & Vashishtha, A. (2013). Evaluation of phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of Holarrhena antidysenterica (Wall.): A comprehensive review. Journal of pharmacy research, 6(4), 488-492. [CrossRef]

- Sobeh, M., Mahmoud, M. F., Hasan, R. A., Abdelfattah, M. A., Osman, S., Rashid, H. O., & Wink, M. (2019). Chemical composition, antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities of methanol extracts from leaves of Terminalia bellirica and Terminalia sericea (Combretaceae). PeerJ, 7, e6322.

- Sonowal, C. J. (2007). Demographic transition of tribal people in forest villages of Assam. Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 5(1), 47-58. [CrossRef]

- Soren, P., & Naik, I. C. (2020). Role of tribal livelihood of non-timber forest product collected in similipal area of Mayurbhanj District of odisha. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(7), 4086-4096.

- Srinivasa Reddy, C., Sri Rama Murthy, K., & Ammani, K. (2022). Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Aromatic Medicinal Plant Commiphora caudata (Wight & Arn.) Engl. Natural Product Experiments in Drug Discovery, 109-120.

- Srinivasan, P., Kothai, R., & Arul, B. (2020). A Comprehensive review on Commiphora caudata (Wight &Arn). International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research (09752366), 12(4).

- Srivastav, S., Singh, P., Mishra, G., Jha, K. K., & Khosa, R. L. (2011). Achyranthes aspera- An important medicinal plant: A review. J Nat Prod Plant Resour, 1(1), 114.

- Srivastava, A. K., & Singh, V. K. (2017). Biological action of Piper nigrum-the king of spices. European Journal of biological research, 7(3), 223-233.

- Srivastava, K., Pandey, S. D., Patel, R. K., Sharma, D., & Nath, V. (2016). Insect Pest Management Practices in Litchi. Insect Pests Management of Fruit Crops.

- Ștefănescu, R., Tero-Vescan, A., Negroiu, A., Aurică, E., & Vari, C. E. (2020). A comprehensive review of the phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological properties of Tribulus terrestris L. Biomolecules, 10(5), 752.

- Sultan, M. T., Anwar, M. J., Imran, M., Khalil, I., Saeed, F., Neelum, S., ... & Al Jbawi, E. (2023). Phytochemical profile and pro-healthy properties of Terminalia chebula: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Food Properties, 26(1), 526-551. [CrossRef]

- Sushma, V., Pal, S. M., & Viney, C. (2017). GC-MS analysis of phytocomponents in the various extracts of Shorea robusta Gaertn F. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res, 9, 783-788. [CrossRef]

- Swain SK, Barik SK, Das MT, Pradhan SN, Deep SK, Dash SR, Jena R, Patra B. 2023. Multi scale structure and nutritional properties of different millet varieties and their potential health effects. Gradiva review journal. 9(8): 588-607.

- Taheri, Y., Herrera-Bravo, J., Huala, L., Salazar, L. A., Sharifi-Rad, J., Akram, M., ... & Cho, W. C. (2021). Cyperus spp.: a review on phytochemical composition, biological activity, and health-promoting effects. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2021.

- Talukdar, N. R., Choudhury, P., Barbhuiya, R. A., & Singh, B. (2021). Importance of non- timber forest products (NTFPs) in rural livelihood: A study in Patharia Hills Reserve Forest, northeast India. Trees, Forests and People, 3, 100042. [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, D., & Devkota, H. P. (2021). Eclipta prostrata (L.) L.(Asteraceae): ethnomedicinal uses, chemical constituents, and biological activities. Biomolecules, 11(11), 1738. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P., Jena, S., Sahu, K. P. (2019). Butea Monosperma: Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Acta Scientific Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3(4), 19-26.

- Tripathy R, Patra B. 2025. Streblus asper Lour: nature’s remedy for modern ailments. Preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Umar, M. I., Asmawi, M. Z. B., Sadikun, A., Altaf, R., & Iqbal, M. A. (2011). Phytochemistry and medicinal properties of Kaempferia galanga L.(Zingiberaceae) extracts. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol, 5(14), 1638-1647.

- Umar, N. M., Parumasivam, T., Aminu, N., & Toh, S. M. (2020). Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Curcuma aromatica Salisb (wild turmeric). Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, 10(10), 180-194.

- Upadhyay, A. K., Kumar, K., Kumar, A., & Mishra, H. S. (2010). Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Hook. f. and Thoms.(Guduchi)–validation of the Ayurvedic pharmacology through experimental and clinical studies. International journal of Ayurveda research, 1(2), 112.

- Verma A, Maurya A, Patra B, Gaharwar US, Paulraj R (2019). Extraction of polyaromatic hydrocarbons from the leachate of major landfill sites of Delhi. Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education. 16(6):1080-1083.

- Vyawahare, N., Pujari, R., Khsirsagar, A., Ingawale, D., Patil, M., & Kagathara, V. (2008). Phoenix dactylifera: An update of its indegenous uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. The Internet Journal of Pharmacology, 7(1), 1-9.

- Wagh, V. D., Wagh, K. V., Tandale, Y. N., & Salve, S. A. (2009). Phytochemical, pharmacological and phytopharmaceutics aspects of Sesbania grandiflora (Hadga): A review. Journal of Pharmacy Research, 2(5), 889-892.

- Warrier, R. R., Priya, S. M., & Kalaiselvi, R. (2021). Gmelina arborea–an indigenous timber species of India with high medicinal value: A review on its pharmacology, pharmacognosy and phytochemistry. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 267, 113593.

- Yadav, M., & Dugaya, D. (2013). Non-timber forest products certification in India: opportunities and challenges. Environment, development and sustainability, 15, 567-586. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M., Dugaya, D., & Basera, K. (2011). Opportunities and Challenges for NWFP certification in India. In International Conference on Non Wood Forest Produce for sustained livelihood during December (Vol. 1719, p. 2011).

- Yadav, R. K., Nandy, B. C., Maity, S., Sarkar, S., & Saha, S. (2015). Phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and clinical trial of Ficus racemosa. Pharmacognosy reviews, 9(17), 73. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S. K., Rai, S. N., & Singh, S. P. (2017). Mucuna pruriens reduces inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in Parkinsonian mice model. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, 80, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Yeasmin, L., Ali, M. N., Gantait, S., & Chakraborty, S. (2015). Bamboo: an overview on its genetic diversity and characterization. 3 Biotech, 5, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A. J., & Abdullahi, M. I. (2019). The phytochemical and pharmacological actions of Entada africana Guill. & Perr. Heliyon, 5(9). [CrossRef]

- Zanin, J. L., de Carvalho, B. A., Martineli, P. S., dos Santos, M. H., Lago, J. H., Sartorelli, P., Viegas, C., Jr, & Soares, M. G. (2012). The genus Caesalpinia L. (Caesalpiniaceae): phytochemical and pharmacological characteristics. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 17(7), 7887–7902. [CrossRef]

| Scientific Name & Family | Plant parts | Uses | QR code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abrus precatorius L. [FABACEAE] | Seed | Scratches and sores |  |

| Acacia auriculiformis A.Cunn. ex Benth. [FABACEAE] | Leaves seed stem | Skin diseases , headache and bloody dysentery. |  |

| Acacia concinna (Willd.) DC. [FABACEAE] | Fruit | For jaundice, fever, skin problems, piles, ascites. |  |

| Acacia catechu (L.)Willd., Oliv. [FABACEAE] | Bark | Cold and cough. |  |

|

Acacia nilotica (L.) Del. [FABACEAE] |

Bark | Diarrhea. |  |

| Acorus calamus L. [ACORACEAE] | Rhizome | Chest pain, colic, cramps, diarrhea, digestive disorders, |  |

| Acalypha indica L. [EUPHORBIACEAE] | Leaf | Digestion. |  |

| Achyranthus aspera L. [AMARANTHACEAE] | Stem | Asthma, bronchitis, and coughs. |  |

| Acmella oleraceae L. [ASTERACEAE] | Root | Inflammation, swelling. |  |

| Adhatoda vasica Nees [ACANTHACEAE] | Leaf | Coughs, sore throat, and other throat infections. |  |

|

Aegle marmelos (L.) Corr. [RUTACEAE] |

Fruit, leaf | Eczema, psoriasis, and skin infections |  |

|

Albizzia lebbeck (L.) Benth [MIMOSACEAE] |

Bark seed | Diarrhoea and piles. |  |

|

Alangium salviifolium (L.f.) Wangerin [CORNACEAE] |

Fruit | Eye disorders. |  |

|

Anacardium occidentale L. [ANACARDIACEAE] |

Fruit seed | Burning. |  |

|

Asperagus racemosus Willd. [LILIACEAE] |

Root stem | Reducing acidity. |  |

|

Bambusa bambos Druce [POACEAE] |

Culm leave root | Skin disease |  |

| Bambax ceiba L. [MALVACEAE] | Fruit, | Pillows, cushions, and mattresses. |  |

| Butea monosperma (Lam.)Taub. [FABACEAE] | Flower seed bark | Ulcer, inflammation, hepatic disorder, and eye diseases. |  |

| Buchanania lanzan Spreng. [ANACARDIACEAE] | Fruit seed | Used as edible fruits. |  |

| Caesalpinia bonduc (L.) Roxb. [FABACEAE] | Seed | Arthritis, rheumatism, and skin infections. |  |

| Cannabis sativa L. [CANNABACEAE] | Leaf root | Childbirth. |  |

| Calamus rotung L. [ARECACEAE] | Spine root | Root for fevers and as an antidote to snake venom. |  |

| Capparis zeylanica L. [CAPPARACEAE] | Root, Bark Leaves |

Snake bite |  |

| Cassia fistula L. [FABACEAE] | Root fruit | Throat disorders. |  |

| Cassia tora (L.)Urban [APIACEAE] | Seed | Itching. |  |

|

Chloraphylum borivilliamum Santapau & R.R.Fern. [ASPARAGACEAE] |

Root | Used in diarrhea, dysentery etc. |  |

|

Chloroxylon swietiana DC. [RUTACEAE] |

Leave | Leaves powder is used for indigestion. |  |

| Cissampelos pareira L. [MENISPERMACEAE] | Root Leaves |

Used in skin ailments, burns, eye trouble |  |

| Clerodendrum serratum (L.) Moon [LAMIACEAE] | Stem | Painkiller |  |

| Commiphora caudata (Wight&Arn.)Engl. [BURSERACEAE] | Latex root | Mouth ulcer |

|

|

Couroupita guianensis Aubl [LECYTHIDACEAE] |

Flower Bark |

Snakebite |  |

| Curcuma longa L. [ZINGIBERACEAE] | Rhizome | Skin disease |  |

|

Curcuma aromatica Salisb. [ZINGIBERACEAE] |

Rhizome | Immunity |  |

|

Curculigo orchiodes Gaertn. [HYPOXIDACEAE] |

Root | Deafness, cough, asthma, piles, diarrhoea |  |

| Cyperus esculentus L. [CYPERACEAE] | Root |

Dysentery, and excessive thirst. |  |

| Cyperus rotundus L. [CYPERACEAE] | Root |

Vomiting. Stomach problem. |  |

|

Delonix regia (Boj. Ex Hook.) Raf. [FABACEAE] |

Leaves | Scorpion bite |  |

|

Desmostachya bipinnata (L.) Stapf. [POACEAE] |

Leaves | Fever |  |

|

Diospyros melanoxylon Roxb. [EBENACEAE] |

Leaf, fruit | Loose motion. |  |

| Eclipta prostrata L. [ASTERACEAE] | Bark , leaf | Check bleeding |  |

| Entada rheedii Spreng. [FABACEAE] | Seed |

Fever |  |

|

Ficus benghalensis Linn. [MORACEAE] |

Bark | Weakness. |  |

| Ficus racemosa L. [MORACEAE] | Bark Leaves Fruit Root |

Wound and ulcers. |  |

| Ficus religiosa Linn. [MORACEAE] | Bark, fruit | Diarrhea, leucoderma. Asthma. |  |

| Flacourtia indica (Burm.f.) Merr. [SALICACEAE] | Fruit bark | Fever. |  |

| Gloriosa superba L. [COLCHICACEAE] | Leaves root tuber | Control pests |  |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. [LAMIACEAE] | Fruit | Fodder. |  |

| Holarrhena pubescens Wall. Ex G.Don [APOCYANACEAE] | Root |

Snake bite. |

|

| Holigarna arnottiana Wall. Ex Hook. F. [ANACARDIACEAE] | Bark Leaves |

Respiratory problems. |  |

| Jatropha gossypiifolia L. [EUPHORBIACEAE] | Seed fruit latex | Teeth problems |  |

| Justicia adhatoda L. [ACANTHACEAE] | Leaf | Cough and cold. |  |

| Kaempferia galanga L. [ZINGIBERACEAE] | Rhizome | Diabetes, hypertension, cough, asthma, joint fractures, rheumatism. |  |

| Limonia acidissima L. [RUTACEAE] | Fruit | Fruits. |  |

| Oroxylum indicum (L.) Benth. ex.Kurz [BIGNONIACEAE] | Bark seed | Ulcer |

|

| Madhuca longifolia (J.kanig)J.F.Macbr [SAPOTACEAE] | Seed, flower, Latex | Diarrhoea. |

|

| Martynia annua L. [MARTYNIACEAE] | Leaves fruit | Antidote to scorpion bites and stings. |  |

| Mucuna prurita (L.)DC. [FABACEAE] | Seed | Antidote for snakebite |  |

| Phyllanthus emblica L. [PHYLLANTHACEAE] | Fruit | Jaundice. |  |

|

Phoenix sylvestris (L.) Roxb. [ARECACEAE] |

Fruit leave | Thatching roof |  |

|

Pongania pinnata (L.)Pierre [FABACEAE] |

Seed, stem | Rheumatism. |

|

|

Petrospermum acerifilium (L.) Willd. [MALVACEAE] |

Flower | Diarrhea. |  |

| Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. [FABACEAE] | Bark leave | Gastrointestinal disorders. |  |

| Piper longum L. [PIPERACEAE] | Fruit root | Colds, asthma, arthritis, |

|

| Ricinus communis L. [EUPHORBIACEAE] | Seed | Abdominal disorders, arthritis, backache |  |

| Santalum album L. [SANTALACEAE] | Stem | Acne. |  |

| Schleichera oleosa (Lour.)Oken [SAPINDACEAE] | Fruit | Acne, itching, burns . |  |

| Solanum nigrum L. [SOLANACEAE] | Fruit leaf root | Cough. |  |

|

Sideroxylon tomentosum Roxb. [SAPOTACEAE] |

Bark | Diarrhea, and skin disease |  |

| Shorea robusta Roth [DIPTEROCARPACEAE] | Bark seed fruit latex | Diarrhea. |  |

| Semecarpus anacardium L.f. [ANACARDIACEAE] | Fruit Seed |

Eczema, dermatitis |

|

| Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Poiret [FABACEAE] | Bark | Stomach issue and scabies. |  |

| Streblus asper Lour. [MORACEAE] | Leaf, Root Stem |

Eczema. |  |

|

Strychnos nux vomica L. [LOGANIACEAE] |

Seed Leaves Root |

Cholera. |  |

|

Schrebrera swictenioides Roxb. [OLEACEAE] |

Bark fruit root | Wound healing. |  |

| Supindus emarginatus Vahl. [SAPINDACEAE] | Fruit bark | Snake bite, toothache, dysentery |  |

|

Swertia angustifoli Buchanan-Hamilton ex D. Don [GENTIANACEAE] |

Bark | Pneumonia, scabies, skin, snakebite, vaginal discharge. |  |

| Saraca asoca (Roxb.)Willd. [FABACEAE] | Flower Bark |

Bleeding. |  |

| Spondias pinnata (L.f.)Kurz [ANACARDIACEAE] | Fruit bark | Diarrhoea and dysentery |  |

| Sida acuta Burm.f. [MALVACEAE] | Root Leaves |

Fever, dysentery, skin diseases |

|

|

Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels. [MYRTACEAE] |

Fruit bark | Asthma, thirst, dysentery and ulcers. |  |

| Tamarindus indica L. [FABACEAE] | Fruit | Stomach pain, throat pain |

|

| Tinoepora cordifolia (Thumb.)Miers [MENISPERMACEAE] | Stem | Diarrhea, dysentery, bone fracture |  |

| Tectona grandis L.f. [LAMIACEAE] | Leaves | Wound healing. |  |

|

Terminalia alata Heyne ex Roth [COMBRETACEA] |

Leaves bark root | Snakebites, dysentery. |  |

| Terminalia chebula Retz. [COMBRETACEAE] | Fruit | Digestive agent |  |

|

Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.)Roxb. [COMBRETACEAE] |

Fruit | Diarrhea. |  |

|

Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.) Wight &Arn. [COMBRETACEAE] |

Bark | Skin diseases |  |

|

Tribulus terresfris L. [ZYGOPHYLLACEAE] |

Seed spine | Skin disease, Acne etc. |

|

|

Vitiveria zizanioides (L.)Nash [POACEAE] |

Root flower | Headache and diarrhoea. |  |

|

Withania somnifera (L.)Dunal [SOLANACEAE] |

Root | Piles, cough and fever. |  |

|

Zingibera officinale Roscoe. [ZINGIBERACEAE] |

Rhizome | Vomiting |

|

|

Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. [RHAMNACEAE] |

Fruit | Food. |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).