1. Introduction

Despite growing evidence supporting the efficacy of LSD-assisted psychotherapy in treating major depressive disorder (MDD) [

1,

2,

3], reliable biomarkers of psychopharmacological or treatment response are not yet fully identified [

4]. LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), a classical serotonergic psychedelic, exerts its acute psychoactive effects primarily through partial agonism at the 5-HT₂A receptor, initiating a cascade of neurotransmitter and neuropeptide release [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The neuropeptide oxytocin, for instance, is released within this cascade and could be a potential psychopharmacological biomarker for LSD-assisted psychotherapy in MDD due to its implication in social bonding, stress modulation, and most importantly, flexibility [

9,

10,

11]. Indeed, theoretical models suggest that flexibility is a major mechanism underlying mood improvement following psychedelic treatment [

12,

13,

14].

The identification of robust biomarkers is crucial in psychopharmacological research, offering objective measures to understand drug action and predict therapeutic outcomes. Biomarkers, broadly defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in their Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) resource as ‘a defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention, including therapeutic interventions’ [FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group, 2016; [

15]], encompass a diverse range of measurable indicators. Among these, pharmacodynamic biomarkers and predictive biomarkers are particularly essential in the context of novel drug development and therapeutic optimization [

15,

16]. Pharmacodynamic biomarkers reflect the biological effects of a drug, providing insights into its mechanism of action, target engagement, and dose-response relationships. These can include changes in receptor occupancy, alterations in neurochemical levels, or specific physiological responses. A predictive biomarker is characterized by its ability to identify individuals or patient subgroups who are most likely to experience a specific effect, whether favorable or unfavorable, in response to a particular medical product or intervention. It is important to note that a single biomarker may, in certain contexts, serve both pharmacodynamic and predictive roles, providing comprehensive insights into drug efficacy and patient stratification [

15,

16]. For a biomarker to be valuable in research, it must be reproducible. Furthermore, the feasibility of biomarker measurement is a critical consideration in clinical research; ideally, biomarkers should be assessed through accessible and minimally invasive procedures, such as blood, urine, or saliva sampling, to facilitate repeated measurements and enhance patient comfort and compliance [

15,

16].

Within this framework, in healthy volunteers, plasma oxytocin concentrations consistently rise 90–180 minutes after oral LSD administration, subsequently declining after the peak [

5,

6,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Studies in rodents, conducted over two decades ago, demonstrated that the selective 5-HT₂A agonist (±)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI) produces a comparable oxytocin increase, which is blocked by the 5-HT₂A antagonist ritanserin [

21,

22]. Interestingly, in humans, the antagonist ketanserin attenuates LSD’s subjective effects [

5]. Despite these convergent findings, oxytocin reactivity during psychedelic treatment was not yet characterized in psychiatric populations. Furthermore, salivary oxytocin, a convenient and non-invasive measurement method, was not yet assessed during LSD administration.

Here, we report pilot data on salivary oxytocin dynamics during a single LSD-assisted psychotherapy session in patients with treatment-resistant MDD, conducted under compassionate-use approval from the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. Our primary objective was to characterize salivary oxytocin reactivity across the acute pharmacodynamic window of a single LSD session. We also explored concurrent ratings of subjective drug intensity.

2. Materials and Methods

Design and Setting

This single-center, observational pilot study was integrated into the routine clinical care at the Psychedelic Program of the Division of Addictology, Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), Switzerland. The study protocol was approved by the regional ethics committee (BASEC No.2024-01122) and prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov the 15th of August 2024 (NCT06557239). All procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Patients were invited to participate in this research after they had obtained individual compassionate-use authorization for LSD-assisted psychotherapy from the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (OFSP). The research protocol, which primarily involved additional salivary sample collection, did not alter the standard clinical routine. All participants provided written informed consent prior to any study procedures. Data collection for this pilot study occurred between September 2024 and February 2025.

Participants

Participants were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: Major Depressive disorder according to the DSM-5 [

23], with criteria of treatment resistance (two or more failed antidepressant treatments of different classes),aged between 18 and 55 years, old, were receiving their first or second LSD treatment with a dose between 100 ug or 150 ug. There were no restriction related to ongoing antidepressant medication, menstrual cycle phase or hormonal contraception use, due to the pilot nature of the study. Exclusion criteria which are part of the routine protocol were as follow: current psychotic or bipolar disorder, imminent suicide risk, severe cardiovascular, hepatic or neurological disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, systemic corticosteroid use.

Twelve participants (5 females, 7 males), aged between 25 and 55 years old (Mean: 43.9, SD: 8.79), signed informed consent and agreed to comply with the protocol. However, we initially had problems with salivary sampling of two participants (1 male and 1 female, for who we did not have enough saliva in more than one time-point, impeding the analysis of reactivity). Our instructions and sampling procedures were adapted and repeated measurements could be analyzed for the 10 other participants. Missing data were considered at random and were treated within the Linear mixed model as described below.

Procedures

The standard clinical procedure for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy in our unit involves an initial screening session, during which a detailed clinical history is collected and eligibility for the program is checked. This comprehensive assessment typically includes a review of medical and psychiatric comorbidities, a thorough medication history, and an evaluation of any contraindications for psychedelic treatment. During this session, the rationale for LSD-assisted psychotherapy, potential risks and benefits, and the overall treatment trajectory are discussed in detail with the patient. Following this, an application is sent to the federal office of public health to obtain approval for the compassionate use of psychedelics to treat depression. This rigorous approval process ensures regulatory oversight and patient safety for the use of non-approved compounds. Once this approval is obtained, patients have a preparation appointment typically held 1 to 3 weeks before the day of the scheduled treatment. During this meeting, patients are invited to participate in the current research protocol. If a patient declines participation, their clinical treatment proceeds as originally planned without inclusion in the research. For those who consent to participate, beyond the standard clinical preparation for LSD-assisted psychotherapy, additional details regarding the salivary sampling procedure are explained.

The treatment is scheduled for 9:00 AM, and patients are required to be present beforehand to finalize preparation details. Upon arrival, patients undergo a brief medical check, including vital signs assessment, to ensure their well-being before drug administration. Any last-minute questions or concerns are addressed. At 9:00 AM, they receive their LSD treatment orally (in solution) and rest in a quiet room under the supervision of trained psychiatric nurses. The setting is designed to be therapeutic and supportive within a sober medical environment. Nurses maintain continuous presence, monitoring the patient’s physiological and psychological state throughout the acute drug effects. Specific safety protocols are in place to manage any unexpected or challenging experiences. The first saliva measure was taken before LSD administration, and subsequent samples were collected following the timeline described below. Although not part of the current research protocol’s primary objectives, it is important to note that patients receive clinical follow-up the day after LSD administration and again one month later. These follow-up appointments collect valuable clinical information that could be utilized in future studies assessing longitudinal treatment outcomes.

Salivary Oxytocin

Saliva samples were collected using Salivette® synthetic swabs (Sarstedt, Germany) at four distinct time-points on the day of LSD administration: Pre-LSD (−10 min before taking the substance, representing baseline), then 60min, 90min and 180 min post-LSD. Patients were carefully instructed to chew the Salivette swab for at least one minute, or longer if they perceived that the swab was not sufficiently saturated with saliva, as adequate sample volume and saturation are critical for reliable oxytocin quantification and to ensure the reproducibility of analyses. The choice of salivary oxytocin measurement was based on its non-invasive nature, which enhances patient comfort and facilitates repeated sampling within a clinical setting, making it particularly suitable for vulnerable populations and acute drug administration protocols. Samples were temporarily stored at -20

0C , then centrifuged and stored at −80 °C. Aliquots were subsequently shipped on dry ice to RIAgnosis (Germany) where oxytocin concentrations (expressed in pg/ml) were quantified by radioimmunoassay (RIA). The specific assay procedures are consistent with those described in previous studies, including a study led by our group [

24,

25]. Thus, Each 300 µl saliva sample underwent evaporation (Eppendorf Concentrator, Germany). Following evaporation, 50 µl of assay buffer was introduced, along with 50 µl of oxytocin-specific antibody (raised in rabbits). The detection limit for this radioimmunoassay (RIA) ranged from 0.1 to 0.5 pg/sample. Assay precision was confirmed by intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation consistently below 10%. To minimize batch effects, all saliva samples were assayed concurrently.

Subjective Measures

At each salivary oxytocin collection time-point after LSD intake (60, 90 and 180 min post-LSD), participants provided momentary ratings of subjective drug intensity ranging between 0 (none) and 10 (maximal intensity).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 28. A linear mixed model (LMM) was employed to investigate the effect of time on oxytocin levels. Oxytocin levels were designated as the dependent variable. Time, a categorical variable with four levels (Pre-LSD, 60min post-LSD, 90min post-LSD, and 180min post-LSD), was included as a fixed effect. To account for the repeated measures nature of the data and individual variability, participant-specific random intercepts were included in the model, with participant ID as the subject grouping variable. An Autoregressive First-Order (AR1) covariance structure was specified for the within-subject repeated measures of oxytocin. The model was estimated using Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML). A Friedman ANOVA was employed to assess differences in the perceived intensity of psychedelic effects across three repeated measurements (60min post-LSD, 90min post-LSD, and 180min post-LSD). This non-parametric test was chosen due to the ordinal nature of the perceived intensity scale (0-10) and to account for the repeated measures design

3. Results

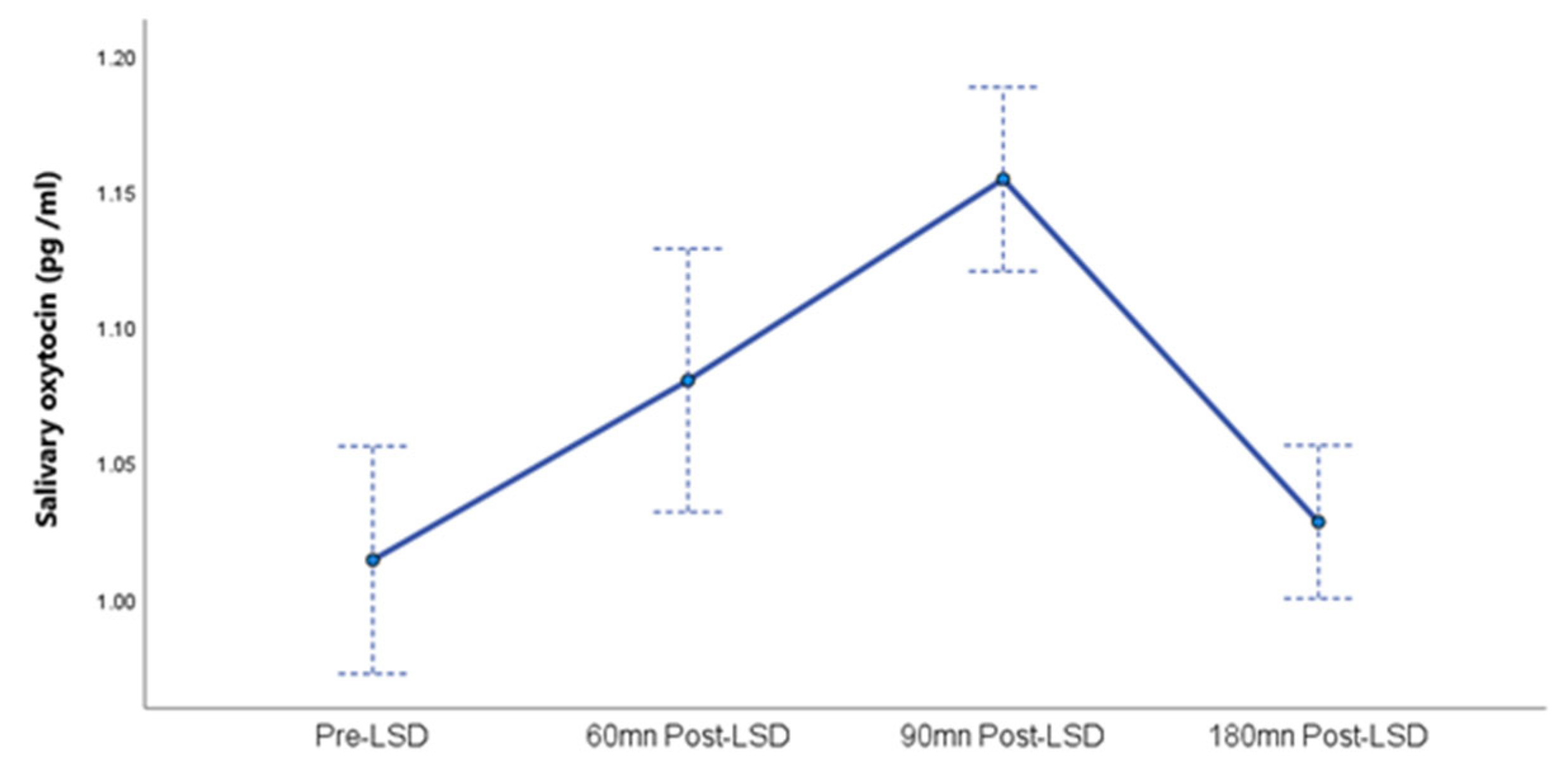

A linear mixed model analysis revealed a significant main effect of time on oxytocin levels, F (3, 19.8) = 14.9, p < 0.001. This indicates that oxytocin levels changed significantly across the four measurement points (Pre-LSD, 60min post-LSD, 90min post-LSD, and 180min post-LSD). The estimated marginal means for oxytocin levels and standard errors at each time point are presented in

Figure 1.

Regarding the random effects, the estimated variance for participant-specific random intercepts was 0.004 (SE = 0.01). The test of this variance component against zero was not significant (Z = 0.40, p = 0.690), suggesting no detectable significant individual differences in participants’ overall oxytocin levels in this pilot study. The 95% confidence interval for the random intercept variance was [~0.000, 0.587], with the lower bound indicating a boundary solution where the estimated variance is effectively zero.

The estimated AR1 parameter for the within-subject covariance structure was 0.009 (SE = 0.011, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.097]). This parameter was also not significantly different from zero (Z = 0.81, p = 0.418), suggesting no significant autocorrelation between oxytocin levels at adjacent time points within individuals in this sample.

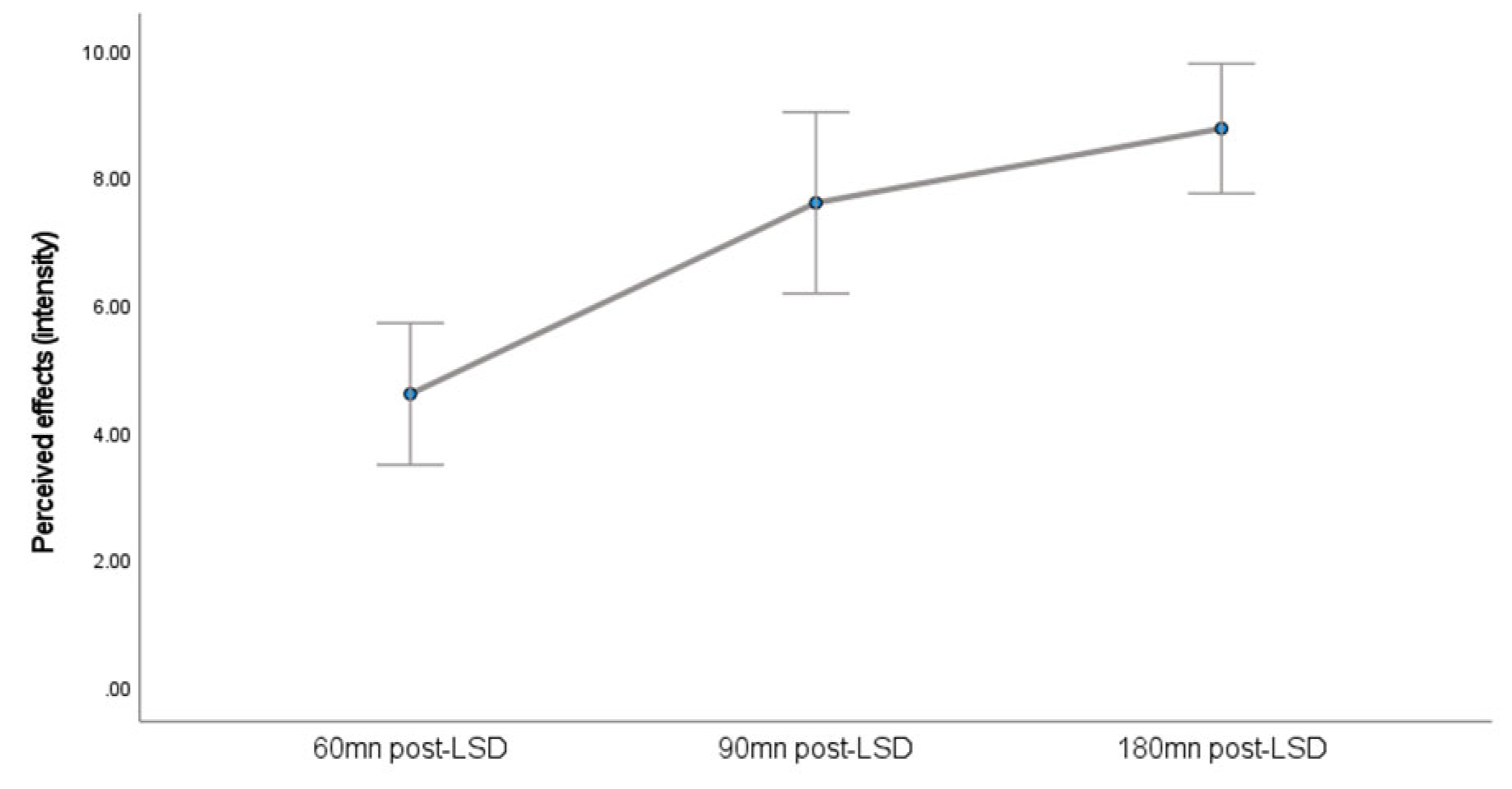

A Friedman ANOVA indicated a statistically significant effect of time on the perceived intensity of psychedelic effects (

Figure 2), χ 2 (2, N = 12) = 21.273, p<.001. This suggests that the perceived intensity of effects varied significantly across the three measurement points (60, 90, and 180 minutes).

4. Discussion

This pilot study presents, to our knowledge, the first characterization of salivary oxytocin dynamics following acute LSD administration in patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). It demonstrates that a non-invasive salivary sampling approach yields temporal information on oxytocin release comparable to that obtained via plasma sampling in earlier investigations. Further, we observed a significant modulation of salivary oxytocin levels over time (with a peak 90 minutes post-LSD intake), paralleling the acute subjective intensity of effects. This finding aligns with previous observations in healthy participants [

5,

17,

26] and is consistent with rodent evidence suggesting 5-HT2A-mediated oxytocin release [

21]. While MDMA is more widely recognized for potent oxytocin release and distinct empathogenic properties [

18,

20], the shared capacity of these compounds to induce oxytocin release, albeit to differing extents, points to potentially convergent neuroendocrine circuits.

The findings of this study contribute preliminary evidence supporting the consideration of oxytocin as a pharmacodynamic biomarker in the context of LSD-assisted psychotherapy for MDD. The observed modulation of salivary oxytocin levels as a function of acute LSD administration, which is consistent with previously reported patterns in both human plasma [

5,

6,

17,

18,

19,

20] and preclinical models [

21,

22], suggests that oxytocin reactivity serves as an indicator of the drug’s acute biological effects. This reproducible observation, obtained through a minimally invasive sampling method, underscores oxytocin’s potential utility for objectively assessing drug engagement and elucidating mechanistic insights. While the current pilot design and sample size preclude definitive conclusions regarding oxytocin’s role as a predictive biomarker, this study establishes the feasibility of characterizing oxytocin dynamics in MDD patients following LSD. Moving forward, larger, adequately powered clinical trials are warranted to conduct the complex correlational analyses necessary to determine if specific oxytocin profiles (e.g., baseline levels or acute changes) correlate with subsequent clinical improvements, such as reductions in depressive symptoms or enhanced mental flexibility, thereby informing patient stratification and personalized treatment approaches.

Despite these initial observations, the interpretation and generalizability of the findings are subject to several methodological limitations inherent to a pilot study design. The open-label nature of the investigation, the heterogeneous medication status of participants, and the absence of a placebo or active control condition constrain the generalizability of the results. Regarding female participants, we did not control for menstrual cycle phase, hormonal contraception use, or menopausal status at this stage, though we acknowledge the critical importance of these variables. Given the well-established influence of sex hormones on the oxytocin system and its associated physiological responses [

27], accounting for these factors is crucial for robust oxytocin research, particularly when investigating potential sex-specific effects or treatment outcomes in larger cohorts. Furthermore, consistent with the study’s integration within a habitual clinical routine, participants continued their prescribed antidepressant medication. As there are currently no recommendations to discontinue antidepressant medications that do not primarily act on 5-HT2A receptors during LSD-assisted psychotherapy, patients maintained their ongoing treatment according to the standard clinical. However, the potential for chronic antidepressant administration to influence endogenous oxytocin secretion or reactivity warrants careful consideration (e.g [

28]). Future investigations should therefore account for the impact of different classes of antidepressant medication on oxytocin dynamics. Finally, this study did not include longitudinal oxytocin follow-up and was not powered to directly assess the relationship between oxytocin release and long-term treatment response (e.g., reduction of depressive symptoms) or changes in mental flexibility. Therefore, larger, rigorously controlled trials are essential to replicate these preliminary findings and to elucidate mechanistic links between oxytocin dynamics and clinically meaningful outcomes.

In conclusion, this pilot study provides insights into the salivary oxytocin dynamics following LSD administration in patients with MDD, underscoring oxytocin’s potential as a pharmacodynamic biomarker. While acknowledging the study’s preliminary nature and limitations, these findings establish the foundation for future, larger-scale investigations aimed at clarifying the mechanistic role of oxytocin in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and its potential utility as a predictive biomarker for treatment outcomes in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TAB; methodology, TAB, LC; formal analysis, TAB; investigation, LC, SA, CA, CM, AB, LF resources, GT, LP, DZ; data curation, TAB, AB; writing—original draft preparation, TAB; project administration, TAB; funding acquisition, TAB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Geneva University Hospitals, grant number PRD 5-2021-II, to TAB. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics Committee (Commission Cantonale d’Ethique de la Recherche (CCER) de Genève)for studies involving humans (BASEC No.2024-01122, the 22nd of July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The final version of the informed consent was approved by the ethics committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Geyer, M.A., A Brief Historical Overview of Psychedelic Research. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging, 2024. 9(5): p. 464-471. [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, P.S., et al., Past, Present, and Future of Psychedelics: A Psychedelic Medicine Roundtable Discussion. Psychedelic Med (New Rochelle), 2023. 1(1): p. 2-11.

- Maia, L.O., Y. Beaussant, and A.C.M. Garcia, The Therapeutic Potential of Psychedelic-assisted Therapies for Symptom Control in Patients Diagnosed With Serious Illness: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2022. 63(6): p. e725-e738. [CrossRef]

- Vollenweider, F.X. and K.H. Preller, Psychedelic drugs: neurobiology and potential for treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2020. 21(11): p. 611-624.

- Holze, F., et al., Role of the 5-HT(2A) Receptor in Acute Effects of LSD on Empathy and Circulating Oxytocin. Front Pharmacol, 2021. 12: p. 711255. [CrossRef]

- Holze, F., et al., Serotonergic Psychedelics - a Comparative review Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Binding Profile of Serotonergic Psychedelics. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging, 2024.

- Liechti, M.E., Modern Clinical Research on LSD. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2017. 42(11): p. 2114-2127. [CrossRef]

- Liechti, M.E., P.C. Dolder, and Y. Schmid, Alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences after acute LSD in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2017. 234(9-10): p. 1499-1510.

- Chini, B., et al., Learning about oxytocin: pharmacologic and behavioral issues. Biol Psychiatry, 2014. 76(5): p. 360-6. [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K., M. Baas, and N.C. Boot, Oxytocin enables novelty seeking and creative performance through upregulated approach: evidence and avenues for future research. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci, 2015. 6(5): p. 409-17.

- Quintana, D.S. and A.J. Guastella, An Allostatic Theory of Oxytocin. Trends Cogn Sci, 2020. 24(7): p. 515-528.

- Johansen, L., et al., How psychedelic-assisted therapy works for depression: expert views and practical implications from an exploratory Delphi study. Front Psychiatry, 2023. 14: p. 1265910. [CrossRef]

- Kocarova, R., J. Horacek, and R. Carhart-Harris, Does Psychedelic Therapy Have a Transdiagnostic Action and Prophylactic Potential? Front Psychiatry, 2021. 12: p. 661233.

- Magaraggia, I., Z. Kuiperes, and R. Schreiber, Improving cognitive functioning in major depressive disorder with psychedelics: A dimensional approach. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 2021. 183: p. 107467. [CrossRef]

- Califf, R.M., Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2018. 243(3): p. 213-221.

- Garcia-Gutierrez, M.S., et al., Biomarkers in Psychiatry: Concept, Definition, Types and Relevance to the Clinical Reality. Front Psychiatry, 2020. 11: p. 432.

- Holze, F., et al., Direct comparison of the acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2022. 47(6): p. 1180-1187. [CrossRef]

- Holze, F., et al., Distinct acute effects of LSD, MDMA, and D-amphetamine in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2020. 45(3): p. 462-471.

- Ley, L., et al., Comparative acute effects of mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide, and psilocybin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study in healthy participants. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2023. 48(11): p. 1659-1667. [CrossRef]

- Straumann, I., et al., Acute effects of MDMA and LSD co-administration in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy participants. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2023. 48(13): p. 1840-1848. [CrossRef]

- Bagdy, G. and K.T. Kalogeras, Stimulation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2/5-HT1C receptors induce oxytocin release in the male rat. Brain Res, 1993. 611(2): p. 330-2.

- Levy, A.D., et al., Repeated cocaine modifies the neuroendocrine responses to the 5-HT1C/5-HT2 receptor agonist DOI. Eur J Pharmacol, 1992. 221(1): p. 121-7.

-

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). 2013.

- Aboulafia-Brakha, T., et al., Hypomodulation of salivary oxytocin in patients with borderline personality disorder: A naturalistic and experimental pilot study. Psychiatry Research Communications, 2023. 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, A., et al., Adolescent oxytocin response to stress and its behavioral and endocrine correlates. Horm Behav, 2018. 105: p. 157-165.

- Schmid, Y., et al., Acute Effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Subjects. Biol Psychiatry, 2015. 78(8): p. 544-53. [CrossRef]

- Quintana, D.S., et al., The interplay of oxytocin and sex hormones. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2024. 163: p. 105765.

- Galbally, M., et al., The relationship between oxytocin blood concentrations and antidepressants over pregnancy and the postpartum. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2021. 109: p. 110218. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).