Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Background

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dimensions and Challenges of Smart Governance

2.2. Sustainable Development Goals and Smart Governance

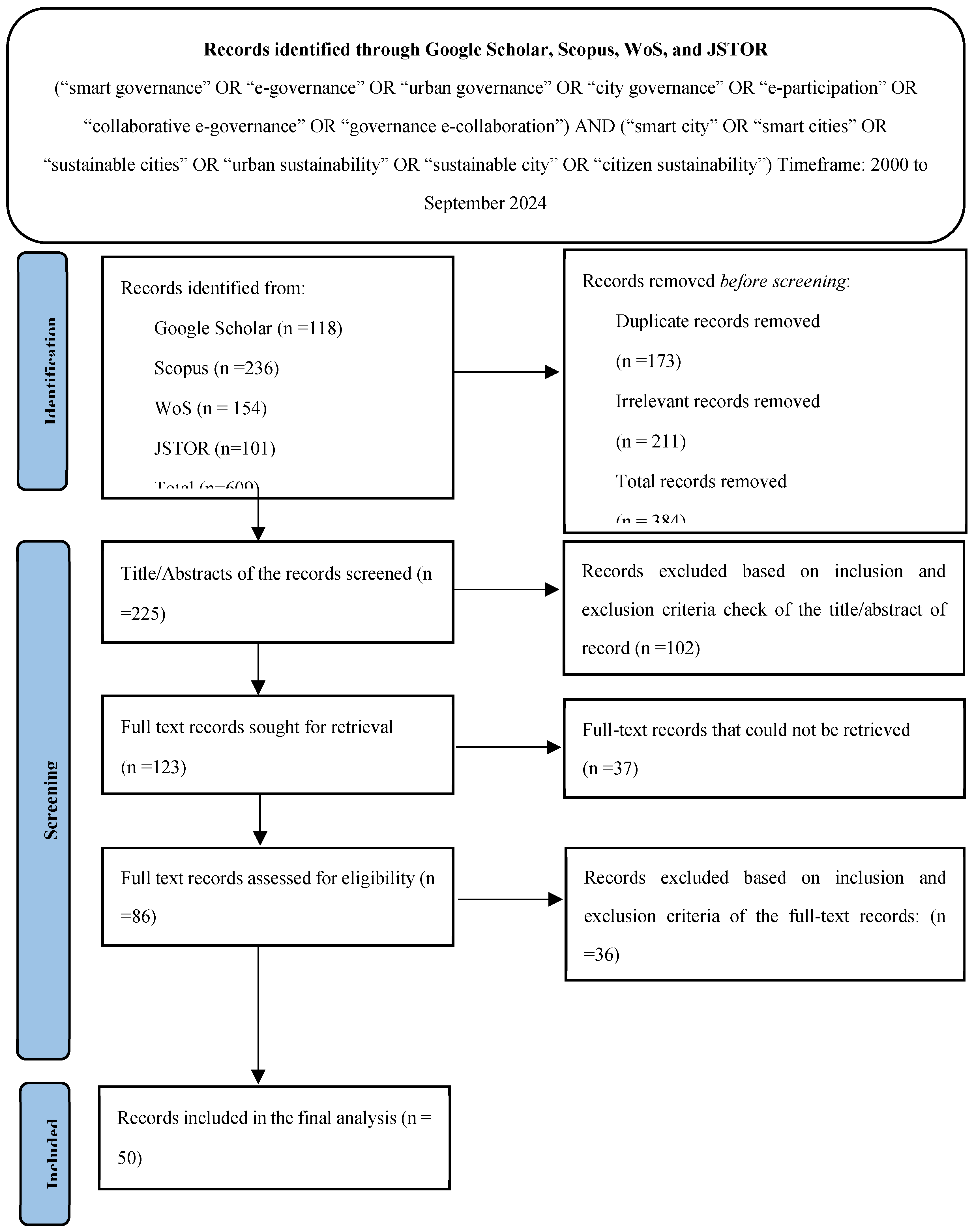

3. Research Design

3.1. Article Selection Process

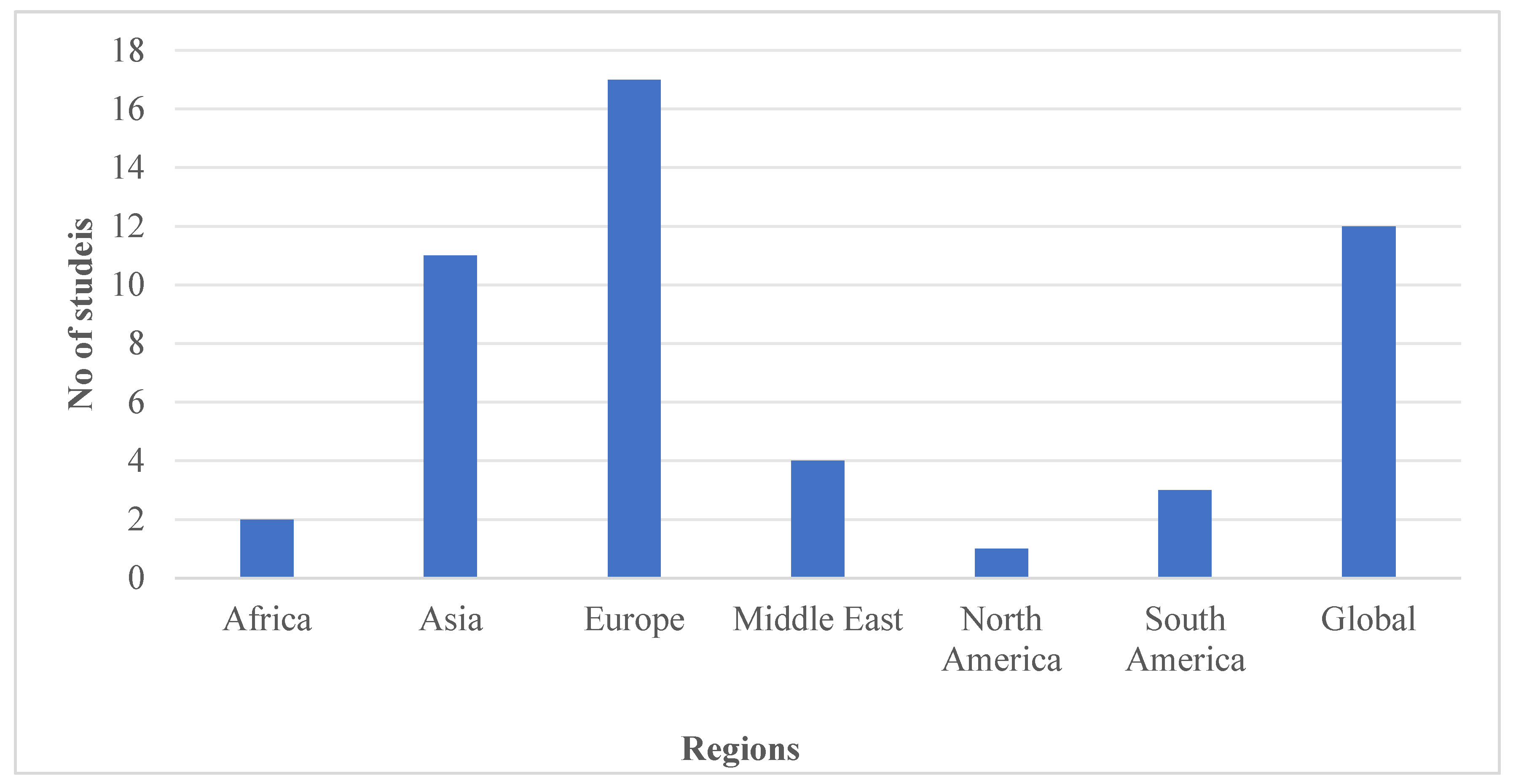

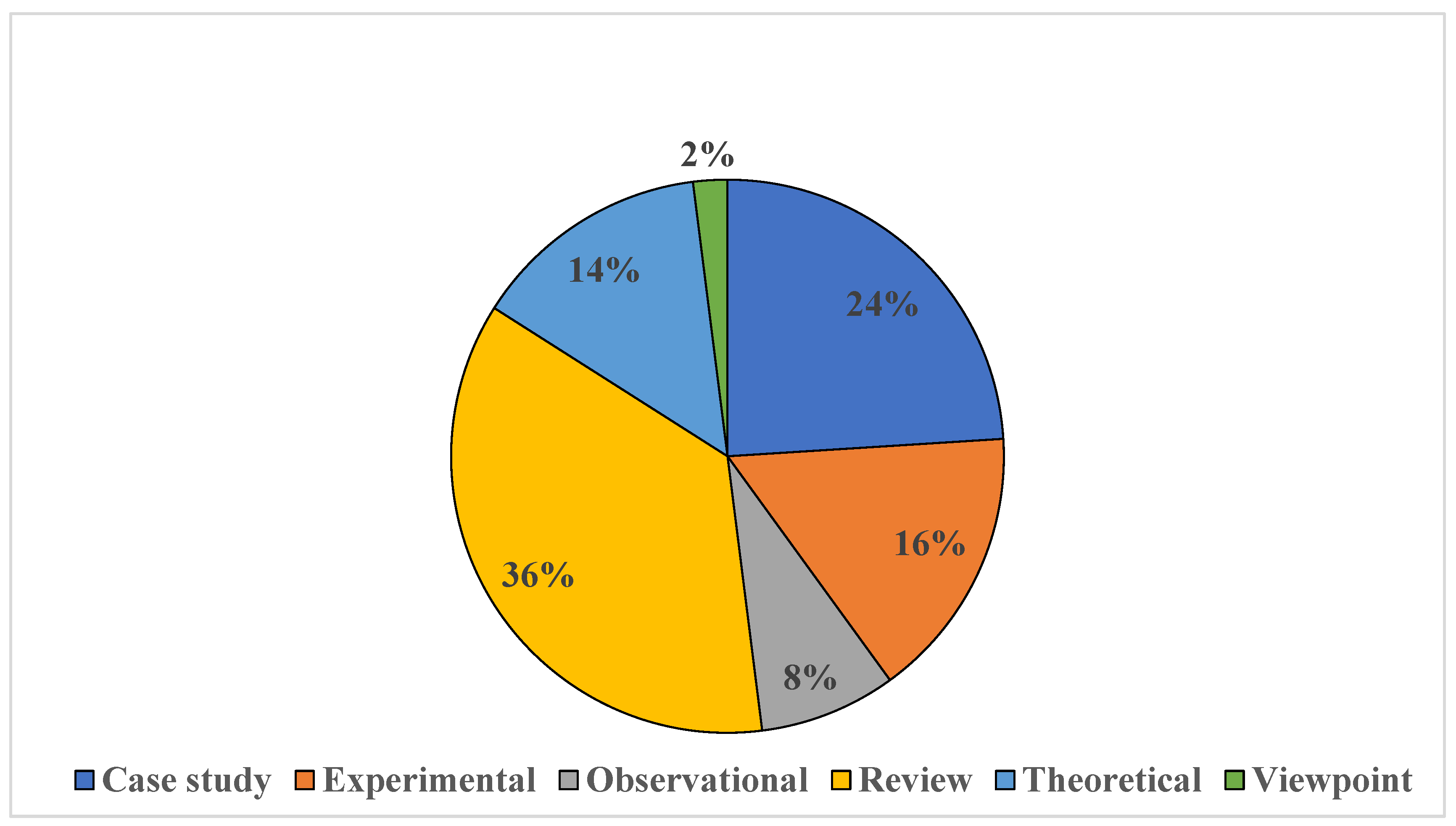

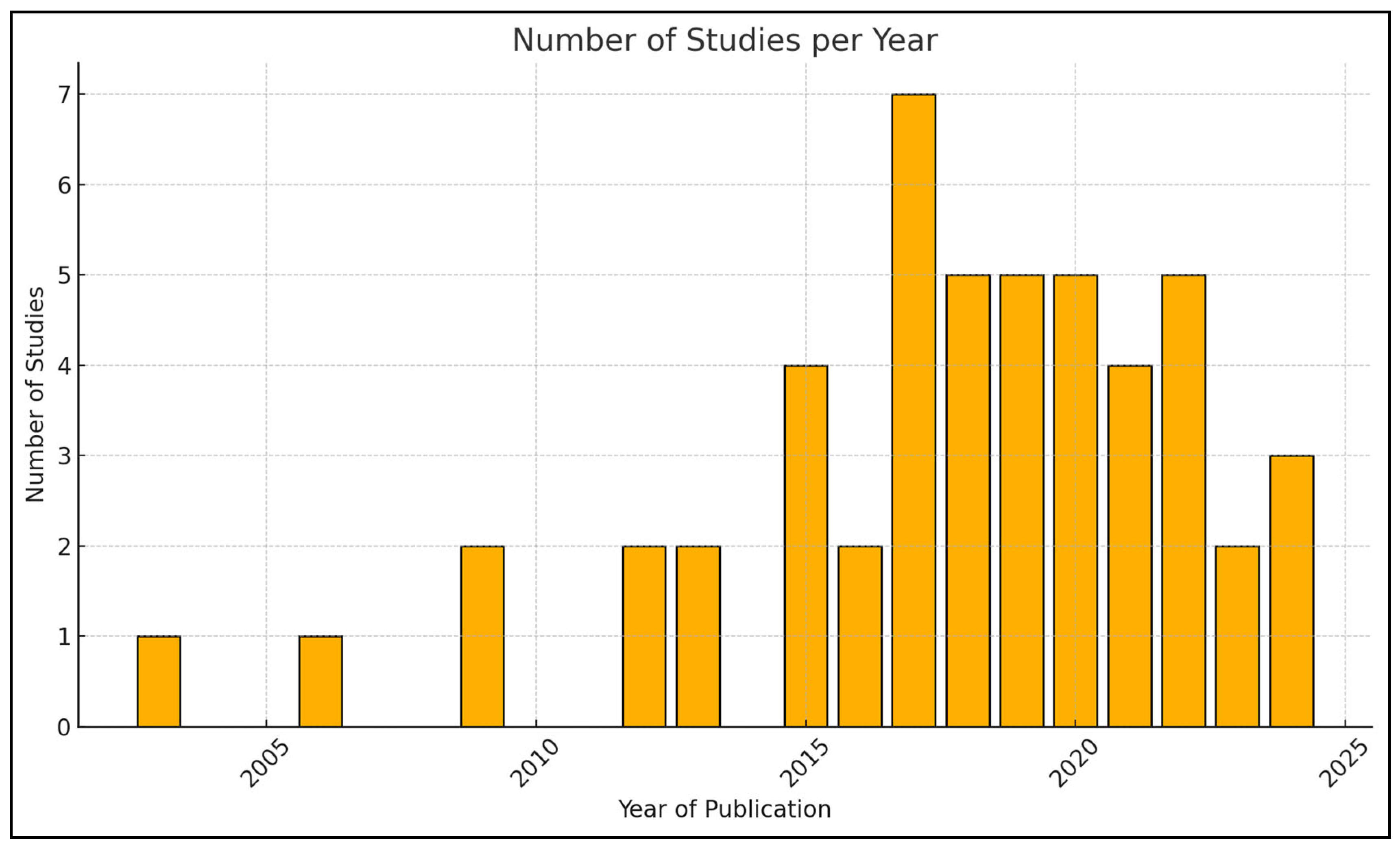

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. General Observations

| Study | Type | Year | Region |

| (Aguilera et al., 2021) | Review | 2021 | Global |

| (Ahvenniemi et al., 2017) | Observational | 2017 | Europe |

| (Akmentina, 2023a) | Theoretical | 2022 | Europe |

| (Allam et al., 2022) | Observational | 2022 | Middle East |

| (Alonso, 2009a) | Case Study | 2009 | Europe |

| (Angelidou et al., 2018) | Case Study | 2017 | Europe |

| (Baud et al., 2021) | Experimental | 2020 | Global |

| (Benites and Simoes, 2021a) | Case Study | 2021 | South America |

| (Bibri and Krogstie, 2019) | Review | 2019 | Europe |

| (Biermann et al., 2012) | Review | 2012 | Global |

| (Bowen et al., 2017) | Experimental | 2017 | Global |

| (Castelnovo et al., 2016a) | Case Study | 2015 | Europe |

| (Clune and Zehnder, 2018) | Theoretical | 2018 | North America |

| (Colding et al., 2020) | Review | 2018 | Europe |

| (Connor, 2006) | Viewpoint | 2006 | Europe |

| (Das, 2024) | Theoretical | 2024 | Asia |

| (Estevez and Janowski, 2013) | Review | 2013 | South America |

| (Ferreira and Ritta Coelho, 2022) | Case Study | 2022 | South America |

| (Fu and Zhang, 2017) | Experimental | 2017 | Asia |

| (Grossi and Welinder, 2024b) | Review | 2023 | Global |

| (Haarstad and Wathne, 2019) | Case Study | 2019 | Europe |

| (Haarstad, 2017) | Theoretical | 2016 | Europe |

| (He et al., 2017) | Observational | 2017 | Asia |

| (He et al., 2022) | Experimental | 2022 | Asia |

| (Herdiyanti et al., 2019) | Review | 2019 | Asia |

| (Huovila et al., 2019) | Review | 2019 | Europe |

| (Ibrahim et al., 2018) | Case Study | 2017 | Middle East |

| (Lange et al., 2013) | Review | 2013 | Europe |

| (Lim and Yigitcanlar, 2022) | Experimental | 2022 | Global |

| (Martin et al., 2019) | Review | 2018 | Global |

| (Meuleman and Niestroy, 2015a) | Theoretical | 2015 | Europe |

| (Mooij, 2003) | Observational | 2003 | Asia |

| (Mutiara et al., 2018) | Review | 2018 | Asia |

| (Nasrawi et al., 2016) | Theoretical | 2016 | Global |

| (Ochara, 2012) | Case Study | 2012 | Africa |

| (Palacin et al., 2021) | Experimental | 2021 | Europe |

| (Paskaleva, 2009) | Review | 2009 | Europe |

| (Patterson et al., 2017) | Experimental | 2017 | Middle East |

| (Rahman et al., 2023) | Case Study | 2023 | Asia |

| (Rochet and Belemlih, 2020a) | Review | 2020 | Europe |

| (Tewari, 2020) | Review | 2020 | Asia |

| (Toli and Murtagh, 2020) | Review | 2020 | Global |

| (Turnheim et al., 2015) | Case Study | 2015 | Europe |

| (Yahia et al., 2021) | Experimental | 2021 | Middle East |

| (Yigitcanlar and Kamruzzaman, 2018) | Theoretical | 2018 | Global |

| (Zachary and Jared, 2015) | Review | 2015 | Africa |

| (Da Cruz et al., 2019) | Review | 2019 | Global |

| (Jiang, 2021) | Review | 2020 | Global |

| (Zhu et al., 2024) | Case Study | 2024 | Asia |

| (Kato and Takizawa, 2024) | Case Study | 2024 | Asia |

4.2. Smart Governance Frameworks in Practice

4.3. Smart Governance Challenges and Barriers

4.4. Smart Governance Best Practices

4.5. Techno-Centric and Human-Centric Governance Models

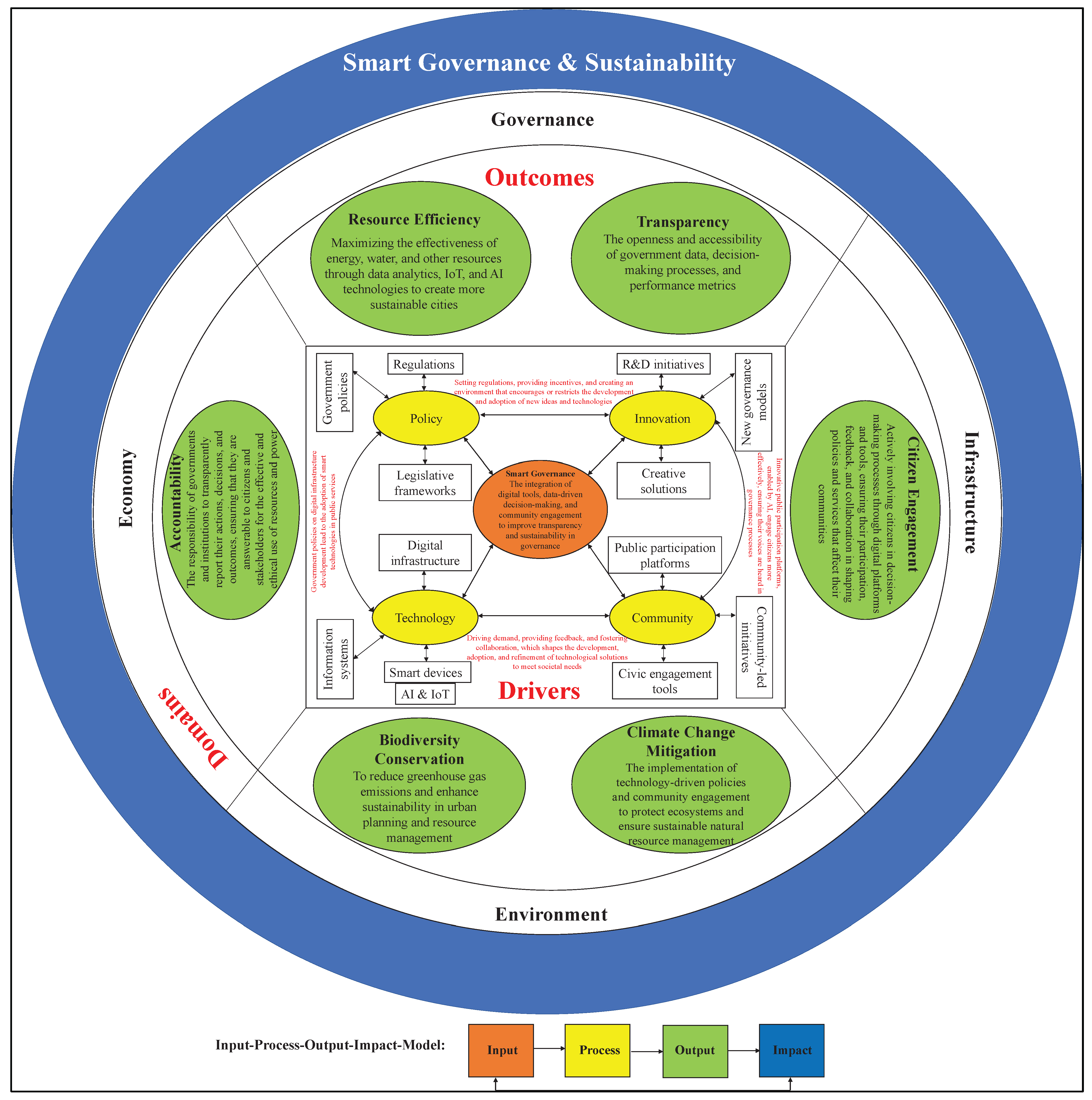

4.6. Towards a Multidimensional Framework

5. Findings and Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Title | Journal | Aim | Challenge | Critique |

| (Aguilera et al., 2021) | “The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research” | “Journal of Management” | Analyze how corporate governance influences environmental sustainability. | Lack of consistent and comparable metrics for measuring corporate sustainability efforts. | The paper offers a broad review but lacks actionable strategies for corporations to integrate sustainability effectively. |

| (Ahvenniemi et al., 2017) | “What Are the Differences Between Sustainable and Smart Cities?” | “Cities” | Compare sustainable and smart city paradigms. | Lack of standardized frameworks for assessing smart cities’ sustainability. | The study lacks practical case studies, assumes technology neutrality, overlooks integration complexities, provides limited focus on social sustainability, and treats paradigms as static rather than evolving. |

| (Lita Akmentina, 2023) | “E-participation and engagement in urban planning: experiences from the Baltic cities” | “Urban Research & Practice” | Examining on how e-participation functions in Baltic cities’ urban planning procedures. | Engaging citizens in meaningful participation remains a significant barrier. | The study highlights successful cases but fails to address the lack of digital infrastructure in less developed regions |

| (Allam et al., 2022) | “Emerging Trends and Knowledge Structures of Smart Urban Governance” |

“Sustainability” | Discuss the technological advancements in smart governance for urban sustainability. | Technological adoption barriers and resistance from legacy systems. | fails to adequately examine how citizens’ involvement and local governments contribute to the adoption of new technologies. |

| (A. I. Alonso, 2009) | “E-Participation and Local Governance: A Case Study” | “Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management” | Examine the impact of digital tools on citizen participation in local governance. | Low engagement of citizens despite digital tools. | Emphasizes the role of socio-economic factors but underplays the technological limitations of e-participation tools |

| (Angelidou et al., 2018) | “Enhancing sustainable urban development through smart city applications” | “Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management” | Explore how smart city applications contribute to sustainable urban development. | Implementing smart city technologies requires large-scale investment and skilled labor. | Focuses primarily on technological solutions but does not sufficiently address socio-economic issues that may hinder implementation. |

| (Baud et al., 2021) | “The urban governance configuration: A conceptual framework for understanding complexity and enhancing transitions to greater sustainability in cities” |

“Geography Compass” | Framework for conceptual analysis and comparison of urban governance arrangements and their dynamics in relation to sustainability transitions. | Various governance configurations within and between cities; how complex decision-making is combined in a specific time and space to produce decisions and outcomes based on a variety of knowledge; and how urban governance could change to more sustainable, inclusive forms of urban development. | In a complex world, this framework makes it possible to integrate key elements (discourses, actor networks, knowledge, and material processes) that influence urban development decisions and results in their social, economic, and environmental domains. |

| (Benites and Simoes, 2021a) | “Assessing Urban Sustainable Development Strategy: An Application of Smart City Sustainability Taxonomy” | “Ecological Indicators” | Develop a taxonomy for assessing smart city sustainability using ICT tools. | Inconsistent data quality and collection methods across cities. | The proposed taxonomy lacks flexibility for adaptation to diverse city structures and governance models. |

| (Bibri and Krogstie, 2019) | “Generating a vision for smart sustainable cities of the future: a scholarly backcasting approach” | “European Journal of Futures Research” | Create a backcasting model for smart, sustainable cities of the future. | Integrating long-term goals with immediate urban policy demands presents challenges. | The backcasting approach is innovative, but practical examples are limited, raising concerns about the scalability of the proposed vision. |

| (Biermann et al., 2012) | “Transforming governance and institutions for global sustainability: key insights from the Earth System Governance” |

“Envirnomental Sustainablilty” | Examine governance challenges in addressing global environmental change. | Overlapping international and national governance systems. | The paper offers innovative frameworks but lacks practical solutions for integrating multiple governance systems. |

| (Bowen et al., 2017) | “Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: towards addressing three key governance challenges— collective action, trade-offs, and accountability” |

“Envirnomental Sustainablilty” | Identify three significant governance issues that are essential to achieving the SDGs: (i) fostering collective action by establishing inclusive decision-making forums for stakeholders from various sectors and scales; (ii) focusing on equity, justice, and fairness while making difficult trade-offs; and (iii) making sure that there are systems in place to hold societal actors accountable for their actions, investments, decisions, and results. | One of the biggest challenges facing sustainability science, civil society, and government is achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to minimize ecological harm, eliminate inequality, and provide resilient lifestyles | The significance of the connections among these three governance challenges is emphasized, along with each of these challenges’ potential solutions. |

| (Castelnovo et al., 2016a) | “Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making” |

“Social Science Computer Review” | Investigate the need for flexible governance models in smart cities. | Balancing technological progress with citizen engagement. | While insightful, the paper does not adequately address how smaller cities with fewer resources can implement these models effectively. |

| (Clune and Zehnder, 2018) | “The Three Pillars of Sustainability Framework: Approaches for Laws and Governance” | “Journal of Environmental Protection” | Analyze the role of governance in shaping sustainability laws and frameworks. | Resistance from stakeholders to adopt sustainability-focused laws. | The paper critiques existing legal frameworks but fails to propose a unified global approach to sustainability governance. |

| (Colding et al., 2020) | “The Smart City Model: A New Panacea for Urban Sustainability or Unmanageable Complexity?” | Urban Analytics and City Science | Explore whether smart cities genuinely lead to sustainability or create unmanageable complexity. | Lack of proper theories to address the complexity of smart city systems. | The paper questions the sustainability of smart cities, but does not propose solutions for managing the growing complexity and potential energy costs. |

| (Connor, 2006) | “The “Four Spheres” Framework for Sustainability” | “Ecological Complexity” | Propose a “Four Spheres” framework integrating economic, social, environmental, and political spheres. | The challenge of balancing economic activity with environmental and social goals. | Provides a thorough conceptual framework but lacks empirical evidence on the effectiveness of applying this framework in real-world governance. |

| (Da Cruz et al., 2019) | “New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities” | “Journal of Urban Affairs” | To review contemporary themes and priorities in urban governance, highlighting governance networks and institutional structures. | Challenges include navigating complex and often conflicting urban policies, diverse stakeholder interests, and institutional reforms. | The study emphasizes the need for empirical backing in understanding urban governance while also acknowledging the limitations of purely technocratic approaches. |

| (Das, 2024) | “Exploring the Symbiotic Relationship between Digital Transformation, Infrastructure, Service Delivery, and Governance for Smart Sustainable Cities” |

“Smart Cities Journal” | Discuss the role of technology in transforming urban governance towards sustainability. | Barriers to technology adoption in legacy governance systems. | The paper fails to fully account for socio-political challenges that hinder the adoption of smart technologies in urban governance. |

| (Estevez and Janowski, 2013) | “Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development—Conceptual framework and state of research” | “Government Information Quarterly” | Explore the role of electronic governance (e-governance) in promoting sustainable development. | Challenges in integrating e-governance solutions across diverse governance frameworks. | The framework is well-defined but requires real-world application to validate its efficacy in diverse urban contexts |

| (Ferreira and Ritta Coelho, 2022) | “Factors of Engagement in E-Participation in a Smart City” | “ICEGOV 2022 Conference” | Investigate the factors that contribute to citizen participation in e-Governance platforms. | Low engagement rates due to cultural and technological barriers. | The study provides good insights but does not suggest actionable solutions to overcome cultural barriers that hinder e-participation |

| (Fu and Zhang, 2017) | “Trajectory of urban sustainability concepts: A 35-year bibliometric analysis” | “Cities” | Review the evolution of urban sustainability concepts over 35 years using bibliometric methods. | Many sustainability concepts are abstract and difficult to implement. | The paper provides an excellent historical review but lacks forward-looking perspectives on the future of urban sustainability initiatives |

| (Grossi and Welinder, 2024b) | “Smart cities at the intersection of public governance paradigms for sustainability” | “Urban Cities” | Investigate how smart city governance intersects with public governance paradigms for sustainability. | Balancing technological innovations with governance models remains a significant challenge. | The paper introduces a novel framework but does not fully explore how this can be practically implemented in lower-income or less technologically advanced cities |

| (Haarstad and Wathne, 2019) | “Are smart city projects catalyzing energy sustainability?” | “Energy Policy” | Examine the links among smart cities and energy sustainability. | Measuring energy efficiency in smart city initiatives is difficult due to a lack of standardized metrics. | The paper emphasizes the potential of smart city initiatives but highlights that energy savings are not adequately measured or quantified. |

| (Haarstad, 2017) | “Constructing the sustainable city: examining the role of sustainability in the ‘smart city’ discourse” | “Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning” | Examine how sustainability is framed within smart city initiatives, with a focus on European cities. | The concept of ‘smart cities’ remains vague and often driven by corporate interests. | The paper offers a critical perspective but could expand on actionable recommendations for policymakers to ensure sustainability plays a central role in smart city agendas |

| (He et al., 2017) | “E-participation for environmental sustainability in transitional urban China” |

“Sustainability Science” | Analyze how ICT can unlock the full potential of e-governance strategies. | Limited access to ICT infrastructure in developing countries. | While the analysis is comprehensive, the paper does not sufficiently address long-term sustainability of ICT projects in less developed regions. |

| (He et al., 2022) | “Legal Governance in the Cities of China: Problems, Solutions, and Models to Support Smart Governance” | “Sustainability” | Explore legal governance issues and propose solutions to support China’s smart city governance. | Legal frameworks often lag behind technological advancements in smart city contexts. | The article provides useful insights but fails to address the broader international implications of China’s governance model (Martin et al., 2018). |

| (Herdiyanti et al., 2019) | “Smart City Program in Indonesia” | “Procedia Computer Science” | Compare seven smart city standards and evaluate their applicability in Indonesian cities. | Customizing global standards to local contexts remains a major challenge. | The study presents valuable comparative insights, but lacks practical guidance on localizing smart city standards (Martin et al., 2018). |

| (Huovila et al., 2019) | “Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for smart sustainable cities” | “Cities” | Analyze and compare indicators used to assess smart sustainable cities across urban contexts. | Ensuring consistency in data collection across different cities remains difficult. | The paper highlights the need for a flexible framework that allows for adaptation to different urban environments |

| (Ibrahim et al., 2018) | “Smart Sustainable Cities Roadmap: Readiness for Transformation towards Urban Sustainability” | “Sustainable Cities & Society” | Propose a roadmap for city planners and decision-makers for transforming traditional cities into SSCs. | Readiness for change in cities is often underestimated, leading to implementation failures. | The roadmap is useful for guiding city transformations, but the study lacks empirical validation through case studies |

| (Lange et al., 2013) | “Smart urban governance in the ‘smart’ era: Why is it urgently needed?” | “Cities” | To analyze the characteristics and urgency of smart urban governance, providing a framework for understanding how smart governance can be implemented effectively. | Challenges include integrating technology with urban planning, addressing technocratic governance issues, and achieving citizen engagement. | While the study effectively highlights the importance of context-based smart urban governance, it could benefit from practical examples or case studies for real-world application |

| (Lim and Yigitcanlar, 2022) | “Urban transformation and population decline in old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area” | “Cities” | To study the nonlinear relationship between population decline and urban transformation in old New Towns using XGBoost analysis. | Challenges include addressing the aging population, land use changes, and the effectiveness of urban planning strategies. | While the study provides valuable insights into the transformation process, it could consider more policy-oriented solutions to address identified issues. |

| (Martin et al., 2019) | “Governing Towards Sustainability—Optimizing Models of Governance” | “Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning” | Explore governance models that optimize sustainability transitions in urban contexts. | Conflict between short-term political cycles and long-term sustainability goals. | The study offers a comprehensive review but does not provide actionable solutions for overcoming political inertia |

| (Meuleman and Niestroy, 2015a) | “Participatory Governance of Smart Cities: Insights from Penang and Puchong” | Smart Cities Journal | Examine how citizen participation can improve smart city governance in Penang and Puchong, Malaysia. | Engaging marginalized communities remains a significant barrier. | The article offers valuable insights but fails to address issues of accessibility and inclusivity in citizen participation strategies |

| (Mooij, 2003) | “Smart-sustainability: A new urban fix?” | “Sustainable Cities & Society” | Explore the potential of smart-sustainability as a fix for urban economic, environmental, and social issues. | The smart-sustainability concept is often driven by corporate interests, limiting its transformative potential. | The paper critiques the over-reliance on technological solutions and advocates for a more balanced approach to sustainability and governance |

| (Mutiara et al., 2018) | “Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work” | “Sustainability” | Develop a metagovernance framework for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in cities. | Achieving consensus among diverse stakeholders is often difficult. | The metagovernance framework is promising but lacks concrete examples of successful implementation in complex urban environments |

| (Nasrawi et al., 2016) | “SMART GOVERNANCE? Politics in the Policy Process in Andhra Pradesh, India” | “Smart Governance” | Investigate the role of politics in the implementation of smart governance in Andhra Pradesh. | Lack of transparency and high levels of political interference in governance structures. | The study effectively analyzes political barriers but lacks specific recommendations on how to overcome them. |

| (Ochara, 2012) | “Smart Governance for Smart City” | “IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science” | Examine the current status of smart governance in Indonesian cities. | A lack of transparency and limited public participation in local governance structures. | The paper provides a strong analysis of e-governance but lacks empirical data on actual improvements in public service delivery |

| (Palacin et al., 2021) | “Smartness of Smart Sustainable Cities: a Multidimensional Dynamic Process Fostering Sustainable Development” | “Fifth International Conference on Smart Cities, Systems, Devices” | Develop a multidimensional model to assess the smartness of sustainable cities. | Defining and standardizing “smartness” as a measurable concept remains a challenge. | The paper proposes a novel model but lacks real-world case studies to validate its effectiveness |

| (Paskaleva, 2009) | “Grassroots Community Participation as a Key to e-Governance Sustainability in Africa” | “The African Journal of Information and Communication” | Explore how grassroots community participation enhances the sustainability of e-governance initiatives. | Limited technological infrastructure and digital literacy in African communities. | The study emphasizes community participation but underplays the technological challenges faced in rural areas |

| (Patterson et al., 2017) | “Reframing E-participation for Sustainable Development” | “ICEGOV” | Investigate the role of e-participation in achieving sustainable urban development. | Engaging marginalized communities in e-participation platforms remains difficult. | The paper highlights the potential of e-participation but lacks concrete examples of successful implementation in marginalized communities |

| (Rahman et al., 2023) | “Enabling the Smart City: The Progress of City e-Governance in Europe” | “International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development” | Analyze how e-governance can improve decision-making and citizen engagement in European cities. | E-governance adoption varies significantly across different European cities, limiting overall progress. | The paper provides comprehensive insights but lacks detailed case studies on cities with advanced e-governance |

| (Rochet and Belemlih, 2020a) | “Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability” | “Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions” | Explore how governance can facilitate transitions toward sustainability, particularly in urban settings. | Aligning political agendas with long-term sustainability goals is challenging. | The study provides a thorough theoretical framework but lacks real-world policy recommendations |

| (Lange et al., 2013) | “From E-Governance to Smart Governance: Policy Lessons for the UAE” | “Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance” | Provide policy recommendations for transitioning from e-governance to smart governance in the UAE. | Limited integration of technology across different government sectors remains a key challenge. | The paper provides insightful policy suggestions but does not explore potential cultural barriers to adoption |

| (Lim and Yigitcanlar, 2022) | “Social Emergence, Cornerstone of Smart City Governance as a Complex Citizen-Centric System” | “Handbook of Smart Cities” | Explore how social emergence plays a key role in smart city governance models. | Balancing technological advancement with citizen participation remains difficult. | The article presents a well-rounded framework but lacks empirical evidence on the real-world impacts of social emergence on governance |

| (Tewari, 2020) | “Towards FoT (Fog-of-Things) enabled Architecture in Governance: Transforming e-Governance to Smart Governance” |

“International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM)” | Propose a FoT-based architecture for transforming e-Governance to smart governance. | High latency and security issues in IoT-based e-Governance. | The solution is promising but requires more real-world testing to address scalability and security concerns. |

| (Toli and Murtagh, 2020) | “The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City Definitions” | “Frontiers in Built Environment” | To review existing smart city definitions, focusing on their sustainability dimensions and propose an updated definition | The lack of a consistent, universally accepted definition of “smart city” across literature | The review is thorough but lacks empirical case studies to test the proposed definition’s effectiveness in practice. |

| (Turnheim et al., 2015) | “Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges” | “Global Climate change” | To create an integrated systems model that addresses the complexities of sustainability transitions | Managing the complexity of multiple systems within environmental and social transitions | The model is comprehensive but may be too complex to apply in practical policymaking without significant adaptation |

| (Yahia et al., 2021) | “Collaborative networks of informatics for smart governance” | “Journal of Information Technology Research” | To explore how collaborative networks of informatics can be leveraged for effective governance in smart cities | The challenge of integrating diverse informatics systems across multiple governance levels | The study provides valuable insights but lacks a clear roadmap for real-world implementation of these collaborative networks |

| (Yigitcanlar and Kamruzzaman, 2018) | “Does smart city policy lead to sustainability of cities?” | “Land use policy” | To investigate the policies that support smart cities and their role in promoting urban sustainability | Difficulty in translating policy into effective on-the-ground sustainability improvements | The paper presents a strong policy analysis but lacks examples of successful implementation in varied urban contexts |

| (Zachary and Jared, 2015) | “Characterizing E-participation Levels in E-governance” | “International Journal of Scientific Research and Technology” | To analyze the role of ICT in enhancing citizen participation in e-governance and assess e-participation levels | Balancing the accessibility of ICT with equitable citizen participation | While the study highlights important factors in e-governance, it doesn’t address how to overcome the digital divide that may limit participation. |

| (Zhu et al., 2024) | “How different can smart cities be? A typology of smart cities in China” | “Cities” | To examine and classify the diverse characteristics of smart cities in China, using a comprehensive framework. | Addressing the varied nature of smart city development and differences in regional contexts within China. | The study provides an in-depth classification but might benefit from broader comparisons with global smart cities to understand China’s unique positioning. |

| Study | City | Governance Model | Key Technologies | Impact on Sustainability | Citizen Engagement |

| (Pieterse, 2019) | Johannesburg | Urban governance and spatial transformation ambitions | Digital platforms, GIS | Focuses on reducing urban fragmentation and supporting sustainable development | Grassroots-level public participation, local councils (baraza and indaba) |

| (Chia, 2016) | Singapore | Smart Nation Initiative | AI, IoT, Blockchain | Improved service delivery, enhanced urban mobility, sustainable urban planning | Public engagement via digital platforms |

| (Sarv and Soe, 2021) | Tallinn, Estonia | Unified Smart City Model | e-Government platforms, AI | Increased efficiency in public service delivery | Public participation through e-governance portals |

| (Hao et al., 2022) | Kenya | Enhancing Public Participation in Governance | ICT, AI | Strengthened public engagement, enhanced decision-making and transparency | Grassroots participation, digital services for marginalized communities |

| (Weil et al., 2023) | Tampere, Finland | Smart Tampere | AI, IoT, Urban Analytics | Enhanced public services, urban planning, and sustainable infrastructure | Participation via digital platforms, promoting inclusivity |

| (Simonofski et al., 2021) | Mexico City | Smart City Initiatives | Digital Platforms, AI | Enhanced business processes, simplified public services | Active engagement through e-platforms |

| (Bibri et al., 2023) | Egypt | Smart City Implementation Framework | AI, IoT | Improved urban management, sustainable resource use | Public consultation and digital participation in decision-making |

| (Vatsa and Chhaparwal, 2021) | Estonia | E-Government and participatory governance | Digital Platforms, Blockchain | Transparency in public services, enhanced citizen-government interactions | High levels of digital participation |

| (Skoric et al., 2016) | Boston, USA | Community Plant | ICT, Social Media | Increased civic engagement and more responsive local government | ICT tools expanded citizen participation tenfold |

| (Yigitcanlar and Bulu, 2015) | Istanbul, Turkey | Knowledge-based urban development | Digital Platforms, AI, Urban Analytics | Increased competitiveness and sustainable economic development | Community involvement through digital platforms |

| Study | City | Governance Model | Key Features | Advantages | Challenges | Approach |

| (Chia, 2016) | Singapore | Smart Nation | AI, IoT, big data analytics | High efficiency, real-time decision-making | Risks citizen disengagement, digital divide | Technocentric |

| (Vatsa and Chhaparwal, 2021) | Estonia | E-Government | Blockchain, e-participation platforms | Increased transparency, digital efficiency | Access for marginalized populations | Technocentric |

| (Aragón et al., 2017) | Barcelona | Decidim (Participatory) | E-participation, community-driven policies | High citizen engagement, inclusive decision-making | Slower decision-making, reliance on consultation | Human-Centric |

| (Corburn et al., 2020) | Medellin | City for Life | Community involvement, grassroots participation | Social cohesion, reduction in crime, inclusivity | Resource-intensive, slower response times | Human-Centric |

| (Herath and Mittal, 2022) | Shanghai | Smart City AI Integration | AI, facial recognition, IoT | Optimized urban management, public safety | Privacy concerns, reduced human oversight | Technocentric |

| (Ylipulli and Luusua, 2020) | Helsinki | Citizen-Centric Smart City | AI-driven services with public feedback mechanisms | Balances technology with public needs | Ensuring equal access to digital platforms | Balanced |

| (Huh et al., 2024) | Songdo | Technological Infrastructure Focus | IoT, big data, automated systems | Fully integrated infrastructure, optimized services | Limited citizen participation, corporate-driven | Technocentric |

| (Griffiths and Sovacool, 2020) | Masdar | Sustainable Tech-Centric Governance | IoT, energy-efficient technologies | Environmentally sustainable, energy-efficient | Top-down approach, limited public engagement | Technocentric |

| (Putra and van der Knaap, 2019) | Amsterdam | Smart City Framework | IoT, data platforms, urban dashboards | Efficient mobility, smart infrastructure | Integrating citizen feedback with technological systems | Balanced |

| (Almalki et al., 2023) | Copenhagen | Collaborative Smart City | IoT, smart sensors, green energy systems | Low emissions, energy-efficient public services | Scaling community-driven initiatives | Balanced |

| (Kumar et al., 2024) | Seoul | AI and IoT-Driven Governance | IoT, big data, AI-powered decision-making | Enhanced urban management, public service efficiency | Privacy concerns, limited community input | Technocentric |

| (Hovik and Giannoumis, 2022) | Bogotá | Participatory Urban Governance | Grassroots mobilization, ICT, public engagement | Empowered communities, participatory decision-making | Slower decision-making, resource-intensive | Human-Centric |

| Study | Title | Journal | Framework | Outcome |

| (Aguilera et al., 2021) | “The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research” | “Journal of Management” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Identifies research gaps in governance roles for sustainability, proposing solutions for comprehensive frameworks and future studies |

| (Ahvenniemi et al., 2017) | “What Are the Differences Between Sustainable and Smart Cities?” | “Cities” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Smart city frameworks emphasize technology, while sustainable frameworks focus more on environmental aspects. Suggests merging both models |

| (Akmentina, 2023a) | “E-participation and engagement in urban planning: experiences from the Baltic cities” | “Urban Research & Practice” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Highlights how ICT tools improve transparency and public engagement but notes challenges in meaningful citizen involvement |

| (Allam et al., 2022) | “Emerging Trends and Knowledge Structures of Smart Urban Governance” |

“Sustainability” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Shows increasing focus on citizen participation and technology adoption in urban governance, identifying future research directions |

| (Alonso, 2009a) | “E-Participation and Local Governance: A Case Study” | “Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Demonstrates both potential and limitations of e-participation; points to political marketing risks outweighing real participation |

| (Angelidou et al., 2018) | “Enhancing sustainable urban development through smart city applications” | “Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Identifies fragmentation in smart city approaches and recommends policy improvements to promote sustainable urban growth |

| (Baud et al., 2021) | “The urban governance configuration: A conceptual framework for understanding complexity and enhancing transitions to greater sustainability in cities” |

“Geography Compass” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Offers insights into improving urban governance through more inclusive and sustainable strategies, focusing on knowledge management |

| (Benites and Simoes, 2021a) | “Assessing Urban Sustainable Development Strategy: An Application of Smart City Sustainability Taxonomy” | “Ecological Indicators” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Identifies a shift towards economic-focused smart city solutions, recommending broader inclusion of social and environmental indicators |

| (Bibri and Krogstie, 2019) | “Generating a vision for smart sustainable cities of the future: a scholarly backcasting approach” | “European Journal of Futures Research” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Proposes strategic pathways to combine technology with sustainability, addressing long-term urban challenges and smart city evolution |

| (Biermann et al., 2012) | “Transforming governance and institutions for global sustainability: key insights from the Earth System Governance” |

“Envirnomental Sustainablilty” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Advocates for transformative global governance to address sustainability challenges, emphasizing institutional reform |

| (Bowen et al., 2017) | “Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: towards addressing three key governance challenges— collective action, trade-offs, and accountability” |

“Envirnomental Sustainablilty” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Highlights governance challenges in SDG implementation and suggests solutions to overcome institutional barriers |

| (Castelnovo et al., 2016a) | “Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making” |

Social Science Computer Review | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Promotes citizen engagement and participatory governance as essential for evaluating smart city policies’ impact |

| (Clune and Zehnder, 2018) | “The Three Pillars of Sustainability Framework: Approaches for Laws and Governance” | “Journal of Environmental Protection” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Emphasizes the importance of integrated approaches for successful sustainability efforts across various domains |

| (Colding et al., 2020) | “The Smart City Model: A New Panacea for Urban Sustainability or Unmanageable Complexity?” | Urban Analytics and City Science | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Warns about the risks of excessive urban complexity and energy consumption, suggesting thoughtful ICT integration |

| (Connor, 2006) | “The “Four Spheres” Framework for Sustainability” | “Ecological Complexity” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Provides a governance model emphasizing interconnected systems to achieve sustainability through balanced decision-making |

| (Da Cruz et al., 2019) | “New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities” | “Journal of Urban Affairs” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Identifies governance challenges such as fiscal autonomy, political engagement, and citizen participation |

| (Das, 2024) | “Exploring the Symbiotic Relationship between Digital Transformation, Infrastructure, Service Delivery, and Governance for Smart Sustainable Cities” |

“Smart Cities Journal” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Emphasizes the need for synchronized governance and infrastructure to achieve smart and sustainable cities |

| (Estevez and Janowski, 2013) | “Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development—Conceptual framework and state of research” | “Government Information Quarterly” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Highlights the role of ICT in facilitating sustainable development through better governance practices |

| (Ferreira and Ritta Coelho, 2022) | “Factors of Engagement in E-Participation in a Smart City” | “ICEGOV 2022 Conference” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Identifies challenges in maintaining citizen engagement through ICT platforms and offers suggestions for improvement |

| (Fu and Zhang, 2017) | “Trajectory of urban sustainability concepts: A 35-year bibliometric analysis” | “Cities” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Shows how concepts like smart cities and sustainable cities overlap and evolve, promoting integrated frameworks for urban sustainability |

| (Grossi and Welinder, 2024b) | “Smart cities at the intersection of public governance paradigms for sustainability” | “Urban Cities” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Demonstrates how smart city governance can achieve social, economic, and environmental sustainability outcomes |

| (Haarstad and Wathne, 2019) | “Are smart city projects catalyzing energy sustainability?” | “Energy Policy” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Smart city projects increase ambition for energy sustainability but face challenges in accountability |

| (Haarstad, 2017) | “Constructing the sustainable city: examining the role of sustainability in the ‘smart city’ discourse” | “Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Highlights the weak focus on sustainability within smart city strategies, driven by economic priorities |

| (He et al., 2017) | “E-participation for environmental sustainability in transitional urban China” |

“Sustainability Science” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Emphasizes the role of ICTs in empowering public engagement but notes barriers to participation in China |

| (He et al., 2022) | “Legal Governance in the Cities of China: Problems, Solutions, and Models to Support Smart Governance” | “Sustainability” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Identifies challenges in data governance, recommending improved legal frameworks to support smart city development |

| (Herdiyanti et al., 2019) | “Smart City Program in Indonesia” | “Procedia Computer Science” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Provides insights into challenges of implementing smart city initiatives in Indonesia without standardized frameworks |

| (Huovila et al., 2019) | “Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for smart sustainable cities” | “Cities” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Offers practical recommendations for selecting appropriate indicators based on urban sustainability goals |

| (Ibrahim et al., 2018) | “Smart Sustainable Cities Roadmap: Readiness for Transformation towards Urban Sustainability” | “Sustainable Cities & Society” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Proposes phases to assess city readiness for change, considering local challenges and opportunities |

| (Lange et al., 2013) | “Smart urban governance in the ‘smart’ era: Why is it urgently needed?” | “Cities” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Advocates for a shift from technology-driven to demand-pulled governance, focusing on urban issues |

| (Lim and Yigitcanlar, 2022) | “Urban transformation and population decline in old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area” | “Cities” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Highlights the shift in New Towns from child-centric to elderly-centric urban structure |

| (Martin et al., 2019) | “Governing Towards Sustainability—Optimizing Models of Governance” | “Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Suggests multi-dimensional governance focusing on politics, policy, and polity aspects |

| (Meuleman and Niestroy, 2015a) | “Participatory Governance of Smart Cities: Insights from Penang and Puchong” | Smart Cities Journal | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Identifies political and institutional challenges in achieving effective participatory governance in Malaysia |

| (Mooij, 2003) | “Smart-sustainability: A new urban fix?” | “Sustainable Cities & Society” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Critiques smart-sustainability initiatives as amplifying ecological modernization without true transformation |

| (Mutiara et al., 2018) | “Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work” | “Sustainability” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Recommends situationally appropriate governance to enhance SDG implementation efforts |

| (Nasrawi et al., 2016) | “SMART GOVERNANCE? Politics in the Policy Process in Andhra Pradesh, India” | “Smart Governance” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Highlights contradictions in governance reform and policy implementation in Andhra Pradesh |

| (Ochara, 2012) | “Smart Governance for Smart City” | “IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Evaluates the effectiveness of e-governance and public information disclosure laws in Indonesia |

| (Palacin et al., 2021) | “Smartness of Smart Sustainable Cities: a Multidimensional Dynamic Process Fostering Sustainable Development” | “Fifth International Conference on Smart Cities, Systems, Devices” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between smartness and sustainable development goals |

| (Paskaleva, 2009) | “Grassroots Community Participation as a Key to e-Governance Sustainability in Africa” | “The African Journal of Information and Communication” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Emphasizes the need for community involvement in e-governance to reduce digital divides |

| (Patterson et al., 2017) | “Reframing E-participation for Sustainable Development” | “ICEGOV” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Demonstrates how e-participation supports sustainable development and aligns with the 2030 Agenda |

| (Rahman et al., 2023) | “Enabling the Smart City: The Progress of City e-Governance in Europe” | “International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Highlights the need for integrated e-services and partnerships to support smart governance |

| (Rochet and Belemlih, 2020a) | “Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability” | “Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Identifies challenges in sustainability transitions and emphasizes the importance of political alignment |

| (Lange et al., 2013) | “From E-Governance to Smart Governance: Policy Lessons for the UAE” | “Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance” | Governance and Policy Frameworks | Analyzes the UAE’s success and challenges in adopting smart governance practices, with policy recommendations for improvement |

| (Lim and Yigitcanlar, 2022) | “Social Emergence, Cornerstone of Smart City Governance as a Complex Citizen-Centric System” | “Handbook of Smart Cities” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Highlights how bottom-up dynamics drive smart governance, using Barcelona and Medellin as case studies |

| (Tewari, 2020) | “Towards FoT (Fog-of-Things) enabled Architecture in Governance: Transforming e-Governance to Smart Governance” |

“International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM)” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Proposes a decentralized architecture for smart governance to enhance efficiency and real-time decision-making |

| (Toli and Murtagh, 2020) | “The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City Definitions” | “Frontiers in Built Environment” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Identifies inconsistencies in smart city definitions and suggests aligning them with sustainability goals |

| (Turnheim et al., 2015) | “Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges” | “Global Climate change” | Conceptual and Development-Oriented Frameworks | Offers a holistic approach to evaluate sustainability transitions and overcome governance challenges |

| (Yahia et al., 2021) | “Collaborative networks of informatics for smart governance” | “Journal of Information Technology Research” | Analytical and Comparative Frameworks | Identifies organizational structures promoting robust and sustainable collaboration among stakeholders |

| (Yigitcanlar and Kamruzzaman, 2018) | “Does smart city policy lead to sustainability of cities?” | “Land use policy” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Reveals that the link between smart cities and reduced CO2 emissions is not linear, recommending better policy alignment |

| (Zachary and Jared, 2015) | “Characterizing E-participation Levels in E-governance” | “International Journal of Scientific Research and Technology” | E-Participation and Citizen-Centric Governance Frameworks | Highlights gaps in citizen engagement and offers recommendations to improve transparency and accountability |

| (Zhu et al., 2024) | “How different can smart cities be? A typology of smart cities in China” | “Cities” | Smart Cities and Sustainability Frameworks | Provides a typology identifying five distinct types of smart cities based on governance and technological approaches |

References

- Aguilera, Ruth V, Aragón-Correa, J Alberto, Marano, Valentina, & Tashman, Peter A. (2021). The corporate governance of environmental sustainability: A review and proposal for more integrated research. Journal of Management, 47(6), 1468-1497. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Imran, Zhang, Yulan, Jeon, Gwanggil, Lin, Wenmin, Khosravi, Mohammad R, & Qi, Lianyong. (2022). A blockchain-and artificial intelligence-enabled smart IoT framework for sustainable city. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 37(9), 6493-6507. [CrossRef]

- Ahvenniemi, Hannele, Huovila, Aapo, Pinto-Seppä, Isabel, & Airaksinen, Miimu. (2017). What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? Cities, 60, 234-245. [CrossRef]

- Akmentina, L. (2023). E-participation and engagement in urban planning: Experiences from the Baltic cities. Urban Research & Practice, 16(3), 624-657. [CrossRef]

- Akmentina, Lita. (2023). E-participation and engagement in urban planning: experiences from the Baltic cities. Urban Research & Practice, 16(4), 624-657. [CrossRef]

- Al-Raeei, Marwan. (2024). The smart future for sustainable development: Artificial intelligence solutions for sustainable urbanization. Sustainable Development. [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, Mohammed, Mohammadian, Masoud, & Talukder, Majharul. (2020). Smart government systems adoption: the case of Saudi Arabia. International Review of Business Research Papers, 16(1), 16-33.

- Allam, Zaheer, & Dhunny, Zaynah A. (2019). On big data, artificial intelligence and smart cities. Cities, 89, 80-91. [CrossRef]

- Allam, Zaheer, Sharifi, Ayyoob, Bibri, Simon Elias, & Chabaud, Didier. (2022). Emerging trends and knowledge structures of smart urban governance. Sustainability, 14(9), 5275. [CrossRef]

- Almalki, Faris A., Alsamhi, S., Sahal, Radhya, Hassan, Jahan, Hawbani, Ammar, Rajput, N.,... Breslin, John. (2023). Green IoT for Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Smart Cities: Future Directions and Opportunities. Mobile Networks and Applications, 28(1), 178-202. [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A. I. (2025). Building Urban Resilience Through Smart City Planning: A Systematic Literature Review. Smart Cities, 8(1), 22. [CrossRef]

- Alomari, Mohammad Abdulhamid N. (2018). Applying Good Governance Practices in the Middle East in the Case of Environmental Protection: A Saudi Arabian Case Study. University of Leeds.

- Alonso, Angel Iglesias. (2009). E-participation and local governance: A case study. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 4(3 (12), 49-62.

- Alonso, J. (2009). E-participation and local governance: A case study. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 4(2), 37-45.

- Angelidou, Margarita, Psaltoglou, Artemis, Komninos, Nicos, Kakderi, Christina, Tsarchopoulos, Panagiotis, & Panori, Anastasia. (2018). Enhancing sustainable urban development through smart city applications. Journal of science and technology policy management, 9(2), 146-169. [CrossRef]

- Aragón, Pablo, Kaltenbrunner, Andreas, Calleja-López, Antonio, Pereira, Andrés, Monterde, Arnau, Barandiaran, Xabier E, & Gómez, Vicenç. (2017). Deliberative platform design: The case study of the online discussions in Decidim Barcelona. Paper presented at the Social Informatics: 9th International Conference, SocInfo 2017, Oxford, UK, September 13-15, 2017, Proceedings, Part II 9.

- Baud, Isa, Jameson, Shazade, Peyroux, Elisabeth, & Scott, Dianne. (2021). The urban governance configuration: A conceptual framework for understanding complexity and enhancing transitions to greater sustainability in cities. Geography Compass, 15(5), e12562. [CrossRef]

- Benites, Ana Jane, & Simoes, Andre Felipe. (2021). Assessing the urban sustainable development strategy: An application of a smart city services sustainability taxonomy. Ecological Indicators, 127, 107734. [CrossRef]

- Benites, L., & Simoes, M. (2021). Assessing urban sustainable development strategy: An application of smart city sustainability taxonomy. Ecological Indicators, 120, 106871. [CrossRef]

- Bibri, Simon Elias, Alexandre, Alahi, Sharifi, Ayyoob, & Krogstie, John. (2023). Environmentally sustainable smart cities and their converging AI, IoT, and big data technologies and solutions: an integrated approach to an extensive literature review. Energy Informatics, 6(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Bibri, Simon Elias, & Krogstie, John. (2019). Generating a vision for smart sustainable cities of the future: a scholarly backcasting approach. European Journal of Futures Research, 7(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Biermann, Frank, Abbott, Kenneth, Andresen, Steinar, Bäckstrand, Karin, Bernstein, Steven, Betsill, Michele M,... Folke, Carl. (2012). Transforming governance and institutions for global sustainability: key insights from the Earth System Governance Project. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(1), 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Bouzguenda, Islam, Alalouch, Chaham, & Fava, Nadia. (2019). Towards smart sustainable cities: A review of the role digital citizen participation could play in advancing social sustainability. Sustainable cities and society, 50, 101627. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K. (2017). Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: Towards addressing three key governance challenges. Environmental Sustainability, 26, 90-96. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Kathryn J, Cradock-Henry, Nicholas A, Koch, Florian, Patterson, James, Häyhä, Tiina, Vogt, Jess, & Barbi, Fabiana. (2017). Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: towards addressing three key governance challenges—collective action, trade-offs, and accountability. Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 26, 90-96. [CrossRef]

- Calder, Kent E. (2016). Singapore: Smart city, smart state: Brookings Institution Press.

- Castelnovo, W., Misuraca, G., & Savoldelli, A. (2016). Smart cities governance: The need for a holistic approach to assessing urban participatory policymaking. Social Science Computer Review, 34(6), 724-739. [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, Walter, Misuraca, Gianluca, & Savoldelli, Alberto. (2016). Smart cities governance: The need for a holistic approach to assessing urban participatory policy making. Social Science Computer Review, 34(6), 724-739. [CrossRef]

- Chia, Eng Seng. (2016). Singapore’s smart nation program—Enablers and challenges. Paper presented at the 2016 11th System of Systems Engineering Conference (SoSE). [CrossRef]

- Clune, William Henry, & Zehnder, Alexander JB. (2018). The three pillars of sustainability framework: approaches for laws and governance. Journal of Environmental Protection, 9(3), 211-240. [CrossRef]

- Colding, Johan, Colding, Magnus, & Barthel, Stephan. (2020). The smart city model: A new panacea for urban sustainability or unmanageable complexity? Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 47(1), 179-187. [CrossRef]

- Connor, Martin. (2006). The “Four Spheres” framework for sustainability. Ecological complexity, 3(4), 285-292. [CrossRef]

- Corburn, Jason, Asari, Marisa Ruiz, Pérez Jamarillo, Jorge, & Gaviria, Aníbal. (2020). The transformation of Medellin into a ‘City for Life:’ insights for healthy cities. Cities & Health, 4(1), 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, Nuno F, Rode, Philipp, & McQuarrie, Michael. (2019). New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Das, Dillip Kumar. (2024). Exploring the Symbiotic Relationship between Digital Transformation, Infrastructure, Service Delivery, and Governance for Smart Sustainable Cities. Smart Cities, 7(2), 806-835. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Jianwei, Huang, Sibo, Wang, Liuan, Deng, Wenhao, & Yang, Tianan. (2022). Conceptual Framework for Smart Health: A Multi-Dimensional Model Using IPO Logic to Link Drivers and Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16742. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Tianhu, Zhang, Keren, & Shen, Zuo-Jun. (2021). A systematic review of a digital twin city: A new pattern of urban governance toward smart cities. Journal of Management Science and Engineering, 6(2), 125-134. [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, Jacobus A. (2006). Sustainable development—historical roots of the concept. Environmental sciences, 3(2), 83-96. [CrossRef]

- Estevez, Elsa, & Janowski, Tomasz. (2013). Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development—Conceptual framework and state of research. Government information quarterly, 30, S94-S109. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, Karen V. (2019). Critically reviewing literature: A tutorial for new researchers. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 27(3), 187-196. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Andrea Cristina Lima, & Ritta Coelho, Taiane. (2022). Factors of engagement in e-Participation in a smart city. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance.

- Ferrer, Ana Luiza Carvalho, Thomé, Antônio Márcio Tavares, & Scavarda, Annibal José. (2018). Sustainable urban infrastructure: A review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 128, 360-372. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, Karin. (2019). Development of a citizen-centric e-government model for effective service delivery in Namibia. Namibia University of Science and Technology.

- Fu, Yang, & Zhang, Xiaoling. (2017). Trajectory of urban sustainability concepts: A 35-year bibliometric analysis. Cities, 60, 113-123. [CrossRef]

- Glass, Lisa-Maria, & Newig, Jens. (2019). Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth System Governance, 2, 100031. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Steven, & Sovacool, Benjamin K. (2020). Rethinking the future low-carbon city: Carbon neutrality, green design, and sustainability tensions in the making of Masdar City. Energy Research & Social Science, 62, 101368. [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G., & Welinder, A. (2024). Smart cities at the intersection of public governance paradigms for sustainability. Urban Cities, 12(1), 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Grossi, Giuseppe, & Welinder, Olga. (2024). Smart cities at the intersection of public governance paradigms for sustainability. Urban Studies, 00420980241227807. [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, Håvard. (2017). Constructing the sustainable city: Examining the role of sustainability in the ‘smart city’discourse. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(4), 423-437. [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, Håvard, & Wathne, Marikken W. (2019). Are smart city projects catalyzing urban energy sustainability? Energy policy, 129, 918-925. [CrossRef]

- Habitat, UN. (2018). Tracking Progress Towards Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements. SDG 11 Synthesis Report-High Level Political Forum 2018.

- Hao, Chen, Nyaranga, Maurice Simiyu, & Hongo, Duncan O. (2022). Enhancing Public Participation in Governance for Sustainable Development: Evidence From Bungoma County, Kenya. Sage Open, 12(1), 21582440221088855. [CrossRef]

- He, Guizhen, Boas, Ingrid, Mol, Arthur PJ, & Lu, Yonglong. (2017). E-participation for environmental sustainability in transitional urban China. Sustainability Science, 12(2), 187-202. [CrossRef]

- He, Wei, Li, Wanqiang, & Deng, Peidong. (2022). Legal governance in the smart cities of china: Functions, problems, and solutions. Sustainability, 14(15), 9738. [CrossRef]

- Herath, H., & Mittal, Mamta. (2022). Adoption of artificial intelligence in smart cities: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(1), 100076. [CrossRef]

- Herdiyanti, Anisah, Hapsari, Palupi Sekar, & Susanto, Tony Dwi. (2019). Modelling the smart governance performance to support smart city program in Indonesia. Procedia Computer Science, 161, 367-377. [CrossRef]

- Hovik, Sissel, & Giannoumis, G. Anthony. (2022). Linkages Between Citizen Participation, Digital Technology, and Urban Development. In S. Hovik, G. A. Giannoumis, K. Reichborn-Kjennerud, J. M. Ruano, I. McShane & S. Legard (Eds.), Citizen Participation in the Information Society: Comparing Participatory Channels in Urban Development (pp. 1-23). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Howarth, Candice, & Robinson, Elizabeth J. Z. (2024). Effective climate action must integrate climate adaptation and mitigation. Nature Climate Change, 14(4), 300-301. [CrossRef]

- Huh, Jeongwha, Sonn, Jung Won, Zhao, Yang, & Yang, Seongwon. (2024). Who built Songdo, the “world’s first smart city?” questioning technology firms’ ability to lead smart city development. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Huovila, Aapo, Bosch, Peter, & Airaksinen, Miimu. (2019). Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for Smart sustainable cities: What indicators and standards to use and when? Cities, 89, 141-153. [CrossRef]

- Husovich, Michael Edward, Zadro, Ruzica, Zoller-Neuner, Lora Lee, Vangheel, Griet, Anyangwe, Odette, Ryan, Diane Puglia, & Rygiel-Zbikowska, Beata. (2019). Process Management Framework: Guidance to Successful Implementation of Processes in Clinical Development. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 53(1), 25-35. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Maysoun, El-Zaart, Ali, & Adams, Carl. (2018). Smart sustainable cities roadmap: Readiness for transformation towards urban sustainability. Sustainable cities and society, 37, 530-540. [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md Nurul, Hossain, Md Aiub, Islam, Md Khairul, & Aziz, Md Tarik Been. (2023). E-Governance Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Public Service Delivery and Citizen Engagement. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Jäntti, Anni, Paananen, Henna, Kork, Anna-Aurora, & Kurkela, Kaisa. (2023). Towards Interactive Governance: Embedding Citizen Participation in Local Government. Administration & Society, 55(8), 1529-1554. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Huaxiong. (2021). Smart urban governance in the ‘smart’era: Why is it urgently needed? Cities, 111, 103004. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Huaxiong, Geertman, Stan, & Witte, Patrick. (2022). Smart urban governance: an alternative to technocratic “smartness”. GeoJournal, 87(3), 1639-1655. [CrossRef]

- Judge, Malik Ali, Khan, Asif, Manzoor, Awais, & Khattak, Hasan Ali. (2022). Overview of smart grid implementation: Frameworks, impact, performance and challenges. Journal of Energy Storage, 49, 104056. [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S.M. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. EBSE Tech-nical Report; Software Engineering Group, School of Computer Science and Mathematics, Keele University and Department of Computer Science, University of Durham: Durham, UK, 2007.

- Kaiser, ZRM Abdullah. (2024). Smart governance for smart cities and nations. Journal of Economy and Technology, 2, 216-234. [CrossRef]

- Kalja, Ahto, Põld, Janari, Robal, Tarmo, & Vallner, Uuno. (2011). Modernization of the e-government in Estonia. Paper presented at the 2011 Proceedings of PICMET’11: Technology Management in the Energy Smart World (PICMET).

- Kamel Boulos, Maged N, Tsouros, Agis D, & Holopainen, Arto. (2015). ‘Social, innovative and smart cities are happy and resilient’: insights from the WHO EURO 2014 International Healthy Cities Conference (Vol. 14, pp. 1-9): Springer. [CrossRef]

- Kandt, Jens, & Batty, Michael. (2021). Smart cities, big data and urban policy: Towards urban analytics for the long run. Cities, 109, 102992. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Haruka, & Takizawa, Atsushi. (2024). Urban transformation and population decline in old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area. Cities, 149, 104991. [CrossRef]

- Komninos, Nicos. (2013). Intelligent cities: innovation, knowledge systems and digital spaces: Routledge.

- Kumar, Sachin, Verma, Ajit Kumar, & Mirza, Amna. (2024). Artificial Intelligence-Driven Governance Systems: Smart Cities and Smart Governance. In S. Kumar, A. Verma & A. Mirza (Eds.), Digital Transformation, Artificial Intelligence and Society: Opportunities and Challenges (pp. 73-90). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Lange, Philipp, Driessen, Peter P, Sauer, Alexandra, Bornemann, Basil, & Burger, Paul. (2013). Governing towards sustainability—conceptualizing modes of governance. Journal of environmental policy & planning, 15(3), 403-425. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jung-Hoon, & Hancock, Marguerite Gong. (2012). Toward a framework for smart cities: A comparison of Seoul, San Francisco and Amsterdam. Research Paper, Yonsei University and Stanford University.

- Lee, Y., & Li, J. Y. Q. (2021). The role of communication transparency and organizational trust in publics’ perceptions, attitudes and social distancing behaviour: A case study of the COVID-19 outbreak: Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2021 Dec;29(4):368-84. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S., Malek, J., Yussoff, M., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2021). Understanding and acceptance of smart city policies: Practitioners’ perspectives on the Malaysian smart city framework. Sustainability, 13(17), 9559. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2022). Participatory governance of smart cities: Insights from e-participation of Putrajaya and Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Smart Cities, 5(1), 71-89. [CrossRef]

- Lovan, W Robert, Murray, Michael, & Shaffer, Ron. (2017). Participatory governance: planning, conflict mediation and public decision-making in civil society: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Margetts, Helen, & Naumann, Andre. (2017). Government as a platform: What can Estonia show the world. Research paper, University of Oxford.

- Martin, Christopher, Evans, James, Karvonen, Andrew, Paskaleva, Krassimira, Yang, Dujuan, & Linjordet, Trond. (2019). Smart-sustainability: A new urban fix? Sustainable cities and society, 45, 640-648. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A., & Bolívar, M. (2016). Governing the smart city: a review of the literature on smart urban governance. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(2), 392-408. [CrossRef]

- Mensah, Justice. (2019). Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent social sciences, 5(1), 1653531. [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L., & Niestroy, I. (2015). Participatory governance of smart cities: Insights from Penang and Puchong. Smart Cities Journal, 2(4), 285-302.

- Meuleman, Louis, & Niestroy, Ingeborg. (2015). Common but differentiated governance: A metagovernance approach to make the SDGs work. Sustainability, 7(9), 12295-12321. [CrossRef]

- Mooij, Jos. (2003). Smart Governance?: Politics in the Policy Process in Andhra Pradesh, India (Vol. 228): Overseas Development Institute London.

- Müller, A Paula Rodriguez. (2022). Citizens engagement in policy making: Insights from an e-participation platform in Leuven, Belgium Engaging Citizens in Policy Making (pp. 180-195): Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mumtaz, Muhammad Hamza, & Abidin, Zain U. (2024). ICT For sustainability in smart cities: a case study of NEOM.

- Mutiara, Dewi, Yuniarti, Siti, & Pratama, Bambang. (2018). Smart governance for smart city. Paper presented at the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. [CrossRef]

- Nasrawi, Sukaina, Adams, Carl, & El-Zaart, Ali. (2016). Smartness of smart sustainable cities: A multidimensional dynamic process fostering sustainable development. Paper presented at the Proc. of the 5th International Conference on Smart Cities, Systems, Devices and Technologies (SMART 2016).

- Noori, Negar, de Jong, Martin, Janssen, Marijn, Schraven, Daan, & Hoppe, Thomas. (2021). Input-Output Modeling for Smart City Development. Journal of Urban Technology, 28(1-2), 71-92. [CrossRef]

- Ochara, Nixon Muganda. (2012). Grassroots community participation as a key to e-governance sustainability in Africa: Section I: Themes and approaches to inform e-strategies. The African Journal of Information and Communication, 2012(12), 26-47.

- Okamura, Keisuke. (2019). Interdisciplinarity revisited: evidence for research impact and dynamism. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 141. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [CrossRef]

- Palacin, Victoria, Zundel, Angelica, Aquaro, Vincenzo, & Kwok, Wai Min. (2021). Reframing e-participation for sustainable development. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance. [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, Krassimira Antonova. (2009). Enabling the smart city: The progress of city e-governance in Europe. International Journal of Innovation and regional development, 1(4), 405-422. [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, Krassimira, Evans, James, Martin, Christopher, Linjordet, Trond, Yang, Dujuan, & Karvonen, Andrew. (2017). Data governance in the sustainable smart city. Paper presented at the Informatics. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J. (2017). Reframing e-participation for sustainable development. ICEGOV, 85(2), 214-230.

- Patterson, James, Schulz, Karsten, Vervoort, Joost, Van Der Hel, Sandra, Widerberg, Oscar, Adler, Carolina,... Barau, Aliyu. (2017). Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 24, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Gabriela Viale, Parycek, Peter, Falco, Enzo, & Kleinhans, Reinout. (2018). Smart governance in the context of smart cities: A literature review. Information Polity, 23(2), 143-162. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, Edgar. (2019). Urban governance and spatial transformation ambitions in Johannesburg. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(1), 20-38. [CrossRef]

- Przeybilovicz, Erico, & Cunha, Maria Alexandra. (2024). Governing in the digital age: The emergence of dynamic smart urban governance modes. Government Information Quarterly, 41(1), 101907. [CrossRef]

- Purvis, Ben, Mao, Yong, & Robinson, Darren. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability science, 14, 681-695. [CrossRef]

- Putra, Zulfikar Dinar Wahidayat, & van der Knaap, Wim. (2019). 6 - A smart city needs more than just technology: Amsterdam’s Energy Atlas project. In L. Anthopoulos (Ed.), Smart City Emergence (pp. 129-147): Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Mohammad Habibur, Albaloshi, Sultan Ahmed, & Sarker, Abu Elias. (2023). From e-governance to smart governance: policy lessons for the UAE Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance (pp. 5075-5087): Springer. [CrossRef]

- Regona, M., Yigitcanlar, T., Hon, C., & Teo, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence and sustainable development goals: Systematic literature review of the construction industry. Sustainable Cities and Society, 105499. [CrossRef]

- Rheingold, Howard. (2008). Using participatory media and public voice to encourage civic engagement: MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative. [CrossRef]

- Repette, P., Sabatini-Marques, J., Yigitcanlar, T., Sell, D., & Costa, E. (2021). The evolution of city-as-a-platform: Smart urban development governance with collective knowledge-based platform urbanism. Land, 10(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, Alessandra. (2017). Governance, Local Communities, and Citizens Participation. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance (pp. 1-14). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Rochet, Claude, & Belemlih, Amine. (2020). Social emergence, cornerstone of smart city governance as a complex citizen-centric system. Handbook of smart cities, 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Rochet, M., & Belemlih, S. (2020). Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 34, 125-136.

- Rotta, M., Sell, D., Pacheco, R., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2019). Digital commons and citizen coproduction in smart cities: Assessment of Brazilian municipal e-government platforms. Energies, 12(14), 2813. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, Md Nazirul Islam, Wu, Min, & Hossin, Md Altab. (2018). Smart governance through bigdata: Digital transformation of public agencies. Paper presented at the 2018 international conference on artificial intelligence and big data (ICAIBD). [CrossRef]

- Sarv, Lill, & Soe, Ralf-Martin. (2021). Transition towards Smart City: The Case of Tallinn. Sustainability, 13(8), 4143. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, Ayyoob, Allam, Zaheer, Bibri, Simon Elias, & Khavarian-Garmsir, Amir Reza. (2024). Smart cities and sustainable development goals (SDGs): A systematic literature review of co-benefits and trade-offs. Cities, 146, 104659. [CrossRef]

- Simonofski, Anthony, Hertoghe, Emile, Steegmans, Michiel, Snoeck, Monique, & Wautelet, Yves. (2021). Engaging citizens in the smart city through participation platforms: A framework for public servants and developers. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106901. [CrossRef]

- Skoric, Marko M, Zhu, Qinfeng, Goh, Debbie, & Pang, Natalie. (2016). Social media and citizen engagement: A meta-analytic review. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1817-1839. [CrossRef]

- Snow, Charles C, Håkonsson, Dorthe Døjbak, & Obel, Børge. (2016). A smart city is a collaborative community: Lessons from smart Aarhus. California Management Review, 59(1), 92-108. [CrossRef]

- Soergel, Bjoern, Kriegler, Elmar, Weindl, Isabelle, Rauner, Sebastian, Dirnaichner, Alois, Ruhe, Constantin,... Popp, Alexander. (2021). A sustainable development pathway for climate action within the UN 2030 Agenda. Nature Climate Change, 11(8), 656-664. [CrossRef]

- Song, Kai, Chen, Yue, Duan, Yongbiao, & Zheng, Ye. (2023). Urban governance: A review of intellectual structure and topic evolution. Urban Governance. [CrossRef]

- Tewari, N & Datt, G. (2020). Towards FoT (fog-of-Things) enabled architecture in governance: Transforming E-Governance to smart governance. Paper presented at the 2020 international conference on intelligent engineering and management (ICIEM). [CrossRef]

- Toli, Angeliki Maria, & Murtagh, Niamh. (2020). The concept of sustainability in smart city definitions. Frontiers in Built Environment, 6, 77. [CrossRef]

- Toots, Anu. (2020). Take-up of municipality e-services: Some findings from citizens’ survey in Tallinn: Retrieved.

- Tomor, Z., Albert, M., Ank, M., & and Geertman, S. (2019). Smart Governance For Sustainable Cities: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Urban Technology, 26(4), 3-27. [CrossRef]

- Turnheim, Bruno, Berkhout, Frans, Geels, Frank, Hof, Andries, McMeekin, Andy, Nykvist, Björn, & van Vuuren, Detlef. (2015). Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges. Global environmental change, 35, 239-253. [CrossRef]

- Underdal, Arild. (2010). Complexity and challenges of long-term environmental governance. Global Environmental Change, 20(3), 386-393. [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, Kristof, Beunen, Raoul, Verweij, Stefan, Evans, Joshua, & Gruezmacher, Monica. (2022). Policy Learning and Adaptation in governance; a Co-evolutionary Perspective. Administration & Society, 54(7), 1226-1254. [CrossRef]

- Vatsa, V. R., & Chhaparwal, P. (2021, 3-3 July 2021). Estonia’s e-governance and digital public service delivery solutions. Paper presented at the 2021 Fourth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Technologies (CCICT). [CrossRef]

- Viale Pereira, Gabriela, Cunha, Maria Alexandra, Lampoltshammer, Thomas J, Parycek, Peter, & Testa, Maurício Gregianin. (2017). Increasing collaboration and participation in smart city governance: A cross-case analysis of smart city initiatives. Information Technology for Development, 23(3), 526-553. [CrossRef]

- Voss, Eckhard, & Rego, Raquel. (2019). Digitalization and public services: A labour perspective.

- Weil, Charlotte, Bibri, Simon Elias, Longchamp, Régis, Golay, François, & Alahi, Alexandre. (2023). Urban Digital Twin Challenges: A Systematic Review and Perspectives for Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 99, 104862. [CrossRef]

- Yahia, Nesrine Ben, Eljaoued, Wissem, Saoud, Narjès Bellamine Ben, & Colomo-Palacios, Ricardo. (2021). Towards sustainable collaborative networks for smart cities co-governance. International journal of information management, 56, 102037. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, Tan, & Bulu, Melih. (2015). Dubaization of Istanbul: Insights from the Knowledge-Based Urban Development Journey of an Emerging Local Economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(1), 89-107. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, Tan, & Kamruzzaman, Md. (2018). Does smart city policy lead to sustainability of cities? Land Use Policy, 73, 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, Tan, Kamruzzaman, Md, Buys, Laurie, Ioppolo, Giuseppe, Sabatini-Marques, Jamile, da Costa, Eduardo Moreira, & Yun, JinHyo Joseph. (2018). Understanding ‘smart cities’: Intertwining development drivers with desired outcomes in a multidimensional framework. Cities, 81, 145-160. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T., Degirmenci, K., Butler, L., & Desouza, K. C. (2022). What are the key factors affecting smart city transformation readiness? Evidence from Australian cities. Cities, 120, 103434. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T., Li, R., Beeramoole, P., & Paz, A. (2023a). Artificial intelligence in local government services: Public perceptions from Australia and Hong Kong. Government Information Quarterly, 40(3), 101833. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T., Agdas, D., & Degirmenci, K. (2023b). Artificial intelligence in local governments: perceptions of city managers on prospects, constraints and choices. Ai & Society, 38(3), 1135-1150. [CrossRef]

- Ylipulli, Johanna, & Luusua, Aale. (2020). Smart cities with a Nordic twist? Public sector digitalization in Finnish data-rich cities. Telematics and Informatics, 55, 101457. [CrossRef]

- Zachary, Omariba Bosire, & Jared, Okebiro Omari. (2015). Characterising E-participation Levels in E-governance. International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology, 2(1), 157-166.

- Zhu, Jialong, Gianoli, Alberto, Noori, Negar, de Jong, Martin, & Edelenbos, Jurian. (2024). How different can smart cities be? A typology of smart cities in China. Cities, 149, 104992. [CrossRef]