Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Energy Audits in Urban Wastewater Systems

2.1. Energy Audit Guidelines

2.1.1. ASHRAE Procedure

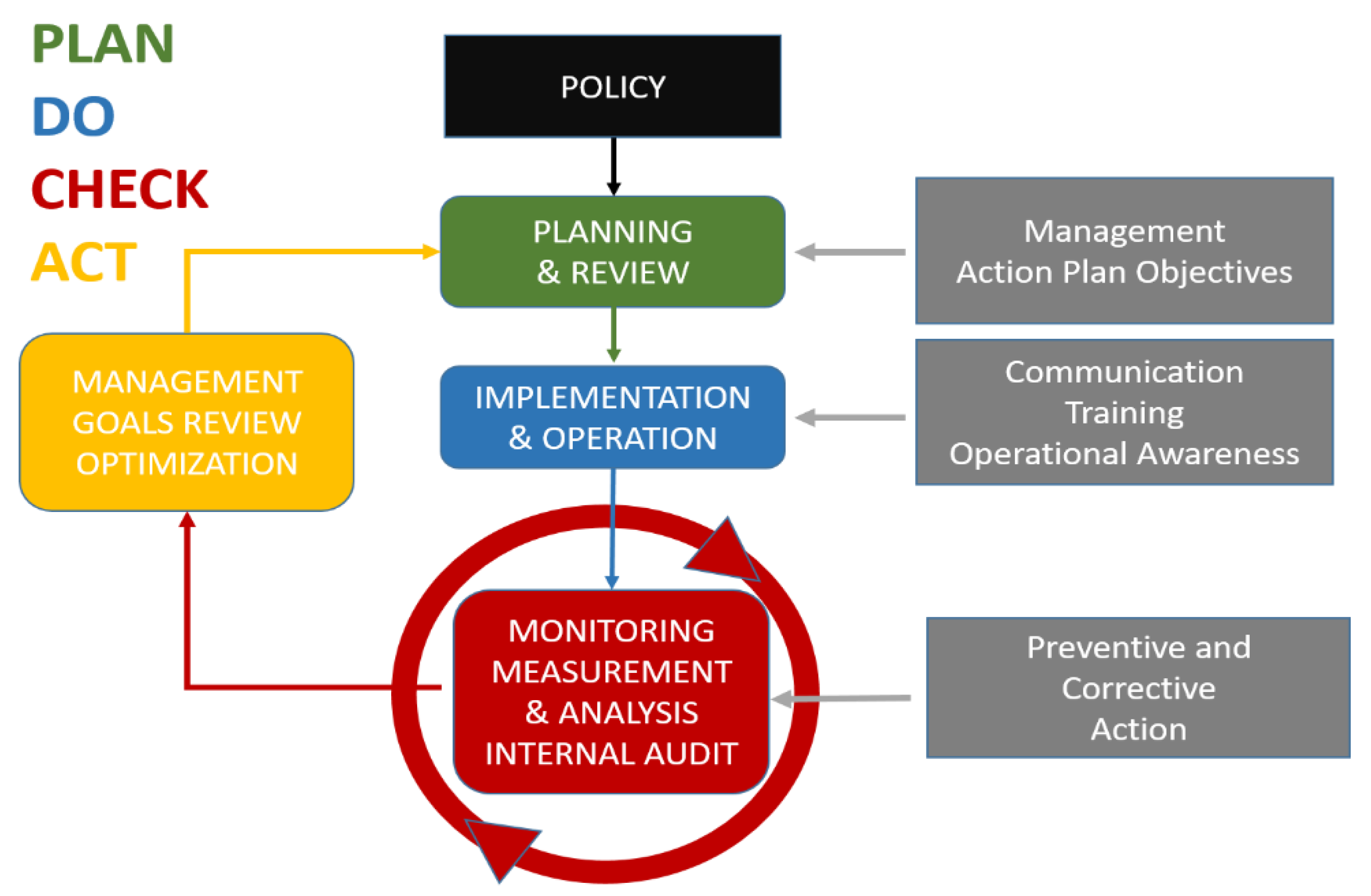

2.1.2. Energy Audits According to ISO 50001

2.2. Audit Requirements

3. WWTP Inefficiencies Causes and Possible Solutions

4. Renewable Energies Contribution to WWTP Energy Efficiency

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capodaglio, A.G.; Olsson, G. Energy Issues in Sustainable Urban Wastewater Management: Use, Demand Reduction and Recovery in the Urban Water Cycle. Sustainability 2020, 12, 266. [CrossRef]

- Mamais, D.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Dimopoulou, A.; Stasinakis, A.; Lekkas, T.D. Wastewater treatment process impact on energy savings and greenhouse gas emissions. Water Sci Technol 2015 71(2):303–308.

- Molinos-Senante, M.; Maziotis, A. Evaluation of energy efficiency of wastewater treatment plants: The influence of the technology and aging factors. Appl Energy 2022, 310, 118535. [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.L.; Williams, A.P.; Styles, D. Pitfalls in international benchmarking of energy intensity across wastewater treatment utilities. J Environ Manag 2021, 300, 113613.

- Lopes, T.A.S.; Queiroz, L.M.; Torres, E.A.; Kiperstok, A. Low complexity wastewater treatment process in developing countries: a LCA approach to evaluate environmental gains. Sci. Total Environ 2020, 720, 137593. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.J.; Rodrigues, E.; Gaspar, A.R.; Gomes, A. Energy performance factors in wastewater treatment plants: A review. J Clean Prod 2021, 322, 129107. [CrossRef]

- Petit-Boix, A.; Sanjuan-Delmás, D.; Chenel, S.; Marín D.; Gasol, C.M.; Farreny, R.; Villalba, G.; Suárez-Ojeda, M.E.; Gabarrell, X.; Josa, A.; Rieradevall, J. Assessing the Energetic and Environmental Impacts of the Operation and Maintenance of Spanish Sewer Networks from a Life-Cycle Perspective. Water Resour Manag 2015, 29, 2581–2597. [CrossRef]

- Gikas, P. Towards energy positive wastewater treatment plants. J Environ Manag 2017, 203, 621-629.

- Capodaglio, A.G. Energy use and decarbonisation of the water sector: a comprehensive review of issues, approaches, and technological options. Environ Technol Rev 2025, 14, 1, 40 - 68.

- EU. DIRECTIVE (EU) 2024/3019 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 27 November 2024 concerning urban wastewater treatment (recast). Official Journal of the European Union EN L series 12.12.2024.

- EU. Council Directive 91/271/EEC of 21 May 1991 concerning urban waste-water treatment. Official Journal of the European Union L 135. 30/05/1991.

- EU. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’). OJ L 243. 9.7.2021.

- Sun, J.; Liang, P.; Yan, X.; Zuo, K.; Xiao, K.; Xia, J.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wu, S.; Huang, X.; Qi, M.; Wen, X. Reducing process aeration energy consumption in MBRs. The MBR site. Avaiable online at https://www.thembrsite.com/features/reducing-process-aeration-energy-consumption-in-membrane-bioreactors#:~:text=1.-,Introduction,and%20scouring%20the%20membrane%20respectively.

- Capodaglio, A.G. Contaminants of emerging concern removal by high-energy oxidation-reduction processes: State of the art. Appl Sci 2019, 9, 211, 4562.

- EU. Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on energy efficiency and amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (recast). Official Journal of the European Union L 231/1, 13/09/2023.

- ASHRAE. Procedures for Commercial Building Energy Audits, 2nd Edition 2011. Peachtree Corners, Georgia, USA.

- Greenberg, E. Energy Audits for Water and Wastewater Treatment Plants and Pump Stations. Continuing Education and Development, Inc., Stony Point, NY 10980, 2013.

- Dwight, A.; Johnson, M. Looking Beyond the Process – Identifying Energy Conservation Opportunities at the Port Dalhousie WWTP. Proceedings WEFTEC 2015. Water Environment Federation. Alexandria, VA. [CrossRef]

- Phelan, T. Development of an auditing methodology for Irish wastewater treatment plants. Master of Engineering thesis, Dublin City University. 2016.

- ISO 50001:2018; Energy Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/69426.html.

- Esteves, F.; Carlos Cardoso, J.; Leitão, S.; Pires, E.J.S. Energy Audit in Wastewater Treatment Plant According to ISO 50001: Opportunities and Challenges for Improving Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2145. [CrossRef]

- Arabeyyat, O.S.; Ragha, L.A. The use of energy management ISO 50001 to increase the effectiveness of water treatment plants: An application study on the Zai water treatment plant. MethodsX, 2024, 12, 102661. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M. Ready or Not: Implementing DOE's 50001 Ready Program for Establishing an Energy Management System. Proceedings of the WEF Utility Management Conference. Water Environment Federation 2024. [CrossRef]

- Machnik-Slomka, J.; Pawlowska, E.; Klosok-Bazan, I.; Goňo, M. Evaluation of the Energy Management System in Water and Wastewater Utilities in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study. Energies 2024, 17, 5014. [CrossRef]

- Nakkasunchi, S.; Brandoni, S. Energy decarbonisation of wastewater treatment plants in Murcia- case study. J Environ Manag 2025, 387, 125874. [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.; Ivan, H.L.; Skvaril,J. A review of the state-of-the-art wastewater quality characterization and measurement technologies. Is the shift to real-time monitoring nowadays feasible? J Wat Proc Engin 2024, 60, 105061. [CrossRef]

- Yaroshenko, I.; Kirsanov, D.; Marjanovic, M.; Lieberzeit, P.A.; Korostynska, O.; Mason, A.; Frau, I.; Legin, A. Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring with Chemical Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 3432. [CrossRef]

- Viviano, G.; Valsecchi, S.; Polesello, S.; Capodaglio, A.; Tartari, G.; Salerno, F. Combined Use of Caffeine and Turbidity to Evaluate the Impact of CSOs on River Water Quality. Water Air Soil Poll 2017, 228, 91, 330.

- Capodaglio, A.G. In-stream detection of waterborne priority pollutants, and applications in drinking water contaminant warning systems. Water Sci Technol Water Supp 2017, 17, 3, 707 – 725.

- Żyłka, R.; Karolinczak, B.; Dąbrowski, W. Structure and indicators of electric energy consumption in dairy wastewater treatment plant. Sci Tot Environ 2021, 782, 146599. [CrossRef]

- Newhart, K.B.; Holloway, R.W.; Hering, A.S.; Cath, T.Y. Data-driven performance analyses of wastewater treatment plants: A review. Water Res 2019, 157, 498-513. [CrossRef]

- Sean, W.Y.; Chu, Y.Y.; Mallu, L.L.; Chen, J.G.; Liu, H.Y. Energy consumption analysis in wastewater treatment plants using simulation and SCADA system: Case study in northern Taiwan. J Clean Prod 2020, 276, 124248. [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G.; Callegari, A. Use, Potential, Needs, and Limits of AI in Wastewater Treatment Applications. Water 2025, 17, 170. [CrossRef]

- DOE. Energy Data Management Manual for the Wastewater Treatment Sector. U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Report DOE/EE1700, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2017.

- Lund, N.S.V.; Borup, M.; Madsen, H.; Mark, O.; Mikkelsen, P.S. CSO Reduction by Integrated Model Predictive Control of Stormwater Inflows: A Simulated Proof of Concept Using Linear Surrogate Models. Water Resour Res 2020, 56, 8, e2019WR026272.

- Shepherd, W.; Mounce, A.; Sailor, G.; Gaffney, J.; Shah, N.; Smith, N.; Cartwright, A.; Boxall, J. Cloud-Based Artificial Intelligence Analytics to Assess Combined Sewer Overflow Performance. I Water Resour Plann Manag 2023, 149, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, S.; Fenu, A.; Wambecq, T.; Weemaes, M.; Van Impe, J.; Willems, P. Energy optimization of the urban drainage system by integrated real-time control during wet and dry weather conditions. Urban Water J 2018, 15(4), 362–370. [CrossRef]

- Reifsnyder, S.; Cecconi, F.; Rosso, D. Dynamic load shifting for the abatement of GHG emissions, power demand, energy use, and costs in metropolitan hybrid wastewater treatment systems. Water Res 2021, 200, 117224.

- Zhou, Q.; Sun, H.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, J. Simultaneous biological removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from secondary effluent of wastewater treatment plants by advanced treatment: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 134054. [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G. Urban Wastewater Mining for Circular Resource Recovery: Approaches and Technology Analysis. Water 2023, 15(22), 3967.

- de Matos, B.; Salles, R.; Mendes, J.; Gouveia, J.R.; Baptista, A.J.; Moura, P. A Review of Energy and Sustainability KPI-Based Monitoring and Control Methodologies on WWTPs. Mathematics 2023, 11, 173. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.R.; Valladares, J.E.; Zanin, J.P.; Cooper, W.J.; Nickelson, M.G.; Kajdi, D.C.; Waite, T.D.; Kurucz, C.N. Figures-of-merit for advanced oxidation technologies: a comparison of homogeneous UV/H2O2, heterogeneous UV/TiO2 and electron beam processes. J Adv Oxid Technol 1998 3:174–181.

- Capodaglio, A.G. High-energy oxidation process: an efficient alternative for wastewater organic contaminants removal. Clean Technol Environ Pol 2017, 19, 8, 1995 – 2006.

- Keen, O.; Bolton, J.; Litter, M.; Bircher K.; Oppenländer, T. Standard reporting of Electrical Energy perOrder (EEO) for UV/H2O2 reactors (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl Chem 2018, 90, 9, 1487-1499. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.L.; Martins, R.; Dias, L.C. Efficiency benchmarking of wastewater service providers: An analysis based on the Portuguese case. J Environ Manag 2022, 321, 115914. [CrossRef]

- Kłosok-Bazan, I.; Rak, A.; Boguniewicz-Zabłocka, J.; Kuczuk, A.; Capodaglio, A.G. Evaluating Energy Efficiency Parameters of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in Terms of Management Strategies and Carbon Footprint Reduction: Insights from Three Polish Facilities. Energies 2024, 17, 5745. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.; Malluta, D.; Del Borghi, A.; Gagliano, E. A Critical Review on Methodologies for the Energy Benchmarking ofWastewater Treatment Plants. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1922. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, R.; Molinos-Senante, M.; Hernandez-Sancho, F.; Sala-Garrido, R. Analysing the efficiency of wastewater treatment plants: The problem of the definition of desirable outputs and its solution. J Clean Prod 2020, 267, 121989.

- Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Longo, S.; Hospido, A. Designing a robust index for WWTP energy efficiency: the ENERWATER water treatment energy index. Sci. Total Environ 2020, 713, 136642. [CrossRef]

- Wiréhn, L.; Danielsson, A.; Neset, T.S.S. Assessment of composite index methods for agricultural vulnerability to climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 156, 70-80, 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.03.020.

- Longo, S.; Chitnis, M.; Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Hospido, A. Transient and persistent energy efficiency in the wastewater sector based on economic foundations. Energy J. 2020, 41 (1), 233–253.

- Maziotis, A.; Sala-Garrido, R.; Mocholi-Arce, M.; Molinos-Senante, M. A comprehensive assessment of energy efficiency of wastewater treatment plants: an efficiency analysis tree approach. Sci. Total Environ 2023. 885, 163539.

- Molinos-Senante, M.; Maziotis, A. Influence of environmental variables on the energy efficiency of drinking water treatment plants. Sci Total Environ 2022, 833, 155246.

- Zhu, W.; Duan, C.; Chen, B. Energy efficiency assessment of wastewater treatment plants in China based on multiregional input–output analysis and data envelopment analysis. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122462.

- Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Chover, V.; Hernández-Sancho, F. Modelling the energy costs of the wastewater treatment process: The influence of the aging factor. Sci Total Environ 2018, 625, 363-372. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, T.; Deineko, E.; Hobus, I.; Kolisch, G.; Lübken, M.; Wichern, M. Effect of sewage sampling frequency on determination of design parameters for municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol 2020, 84, 284–292.

- Li, J.; Du, A.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; He, L; Gu, L.; Cheng, H.; He, Q. Analysis of factors influencing the energy efficiency in Chinese wastewater treatment plants through machine learning and SHapley Additive exPlanations. Sci Tot Environ 2024, 920, 171033. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Muttaqi, K.M.; Sutanto, D.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Ker, P.J.; Hannan, M.A. Control technologies of wastewater treatment plants: The state-of-the-art, current challenges, and future directions. Ren Sust Energy Rev 2023, 181, 113324. [CrossRef]

- Castellet, L.; Molinos-Senante, M. Efficiency assessment of wastewater treatment plants: a data envelopment analysis approach integrating technical, economic, and environmental issues. J. Environ. Manag 2016, 167, 160-166. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Rosa, M.J. Energy performance indicators of wastewater treatment: a field study with 17 Portuguese plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 72, 510-519. [CrossRef]

- Barnard, J.L.; Steichen, M.; Cambridge, D. Hydraulics in BNR plants. Proceedings WEFTEC 2004, New Orleans. Water Environment Federation. DOI10.2175/193864704784147241.

- Sgroi, M.; Snyder, S.A.; Roccaro, P. Comparison of AOPs at pilot scale: Energy costs for micro-pollutants oxidation, disinfection by-products formation and pathogens inactivation. Chemosphere 2021, 273, 128527. [CrossRef]

- Trojanowicz, M.; Bojanowska-Czajka, A.; Capodaglio, A.G. Can radiation chemistry supply a highly efficient AO(R)P process for organics removal from drinking and waste water? A review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 20187–20208. [CrossRef]

- Di Fraia, S.; Massarotti, N.; Vanoli, L. A novel energy assessment of urban wastewater treatment plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 163, 304-313. [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G.; Callegari, A. Energy and resources recovery from excess sewage sludge: A holistic analysis of opportunities and strategies. Resour Conserv Recyc Adv 2023, 19, 200184.

- Torregrossa, D.; Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Sancho, F. A data analysis approach to evaluate the impact of the capacity utilization on the energy consumption of wastewater treatment plants. Sust Cities Society 2019, 45, 307-313. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Chover, V.; Bellver-Domingo, A.; Hernández-Sancho, F. The influence of oversizing on maintenance cost in wastewater treatment plants. Proc Saf Environ Prot 2021, 147, 734-741. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Wolfram, M.; Anja, H. Factors affecting economies of scale in combined sewer systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62, 36–41.

- Capodaglio, A.G. Integrated, Decentralized Wastewater Management for Resource Recovery in Rural and Peri-Urban Areas. Resources 2017, 6, 22. [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Jeong, T.Y.; Lee, S. Application of jetventurimixer for developing low-energy-demand and highly efficient aeration process of wastewater treatment. Heliyon 2022, 8, 10e11096.

- Rosso, D.; Stenstrom, M.K., Garrido-Baserba, M. Aeration and mixing. In: Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Modelling and Design. 2nd Ed. Chen, G., van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Ekama G.A.; Brdjanovic D. (Eds). IWA Publishing, London 2023.

- Beder S. Technological paradigms: the case of sewerage engineering. Technol Stud. 1997;4(2):167–188.

- Capodaglio AG. Taking the water out of “wastewater”: an ineluctable oxymoron for urban water cycle sustainability. Water Environ Res. 2020, 92(12):2030–2040. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S. Comparative evaluation of vacuum sewer and gravity sewer systems. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag 2017, 8, 37–53. [CrossRef]

- Obradović, D.; Šperac, M.; Marenjak, S. Maintenance issues of the vacuum sewer system. Environ Engin 2019, 6(2):40-48. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Çanka Kılıç, F.; Öztürk, H.H. Energy Efficiency in Pumps. In: Energy Management and Energy Efficiency in Industry. Green Energy and Technology. Springer, Cham. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Badruzzaman, M.; Crane, T.; Hollifield, D.; Wilcoxson, D.; Jacangelo, J. G. Minimizing energy use and GHG emissions of lift stations utilizing real-time pump control strategies. Water Environ Res 2016, 88 (11), 1973–1984.

- Kato, H.; Fujimoto, H.; Yamashina, K. Operational Improvement of Main Pumps for Energy-Saving in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water 2019, 11, 2438.

- Zhang, D.; Dong, X.; Zeng, S.; Wang, X.; Gong, D., Mo, L. Wastewater reuse and energy saving require a more decentralized urban wastewater system? Evidence from multi-objective optimal design at the city scale. Water Res 2023, 235, 119923. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, D.; Restrepo, I.; Grueso-Casquete, S. Key criteria for considering decentralization in municipal wastewater management. Heliyon 2021, 7, 3e06375.

- Cecconet, D.; Callegari, A.; Capodaglio, A.G. UASB Performance and Perspectives in Urban Wastewater Treatment at Sub-Mesophilic Operating Temperature. Water 2022, 14(1), 115.

- Zeeman, G.; Kujawa, K.; de Mes, T.; Hernandez, L.; de Graaf, M.; Abu-Ghunmi, L.; Mels, A.; Meulman, B.; Temmink, H.; Buisman, C.; et al. Anaerobic treatment as a core technology for energy, nutrients and water recovery from source-separated domestic waste(water). Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 57, 1207–1212.

- Ahmad, H.A.; Ahmad, S.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z.; El-Baz, A.; Ni, S.Q. Energy-efficient and carbon neutral anammox-based nitrogen removal by coupling with nitrate reduction pathways: A review. Sci Total Environ 2023, 889, 164213. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Xiao, X.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, J. Evaluation of the economic and environmental benefits of partial nitritation anammox and partial denitrification anammox coupling preliminary treatment in mainstream wastewater treatment. Ren Sust Energy Rev 2023, 188, 113800. [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, J.; de Blois, M.; Persson, F.; Gustavsson, D.J.I.; Bengtsson, S.; van Erp, T.; Wilén, B.M. Case study of aerobic granular sludge and activated sludge—Energy usage, footprint, and nutrient removal. Water Environ Res 2023, 95, 8, e10914.

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Lei, Z.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, D.J. Energy and resource recovery from a future aerobic granular sludge wastewater treatment plant and benefit analysis. Cheml Engin J 2024, 487, 150558. [CrossRef]

- Strazzabosco, A.; Kenway, S.J.; Lant, P.A. Solar PV adoption in wastewater treatment plants: A review of practice in California. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109337.

- Lima, D.; Li, L.; Appleby, G. A Review of Renewable Energy Technologies in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs). Energies 2024, 17, 6084. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, R.R.; Kalidasan, B.; Laghari, I.A.; Samykano, M.; Kothari, R. Abusorrah, A.M.; Sharma, K. Tyagi, V.V. Utilization of solar energy for wastewater treatment: Challenges and progressive research trends. J Environ Manag, 2021, 297, 113300. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, W. Economic and ecological assessment of photovoltaic systems for wastewater treatment plants in China. Ren Energy 2022, 191, 852-867. [CrossRef]

- Boguniewicz-Zablocka, J.; Klosok-Bazan, I.; Capodaglio, A.G. Sustainable management of biological solids in small treatment plants: overview of strategies and reuse options for a solar drying facility in Poland. Environ Sci Poll Res 2021, 28, 19, 24680 – 24693. [CrossRef]

- AQUA. Jersey-Atlantic Wind Farm. Available at https://www.acua.com/Projects/Jersey-Atlantic-Wind-Farm.aspx (accessed 28/05/2025).

- Das, B.K.; Al-Abdeli, Y.M.; Kothapalli, G. Optimisation of stand-alone hybrid energy systems supplemented by combustion-based prime movers. Appl Energy 2017. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Safder, U.; Nguyen, X.Q.N.; Yoo, C.K. Multi-objective decision-making and optimal sizing of a hybrid renewable energy system to meet the dynamic energy demands of a wastewater treatment plant. Energy 2020, 191, 116570. [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Electricity storage and renewables: Costs and markets to 2030. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi 2017.

- Notton, G.; Nivet, M.L.; Voyant, C.; Paoli, C.; Darras, C.; Motte, F.; et al. Intermittent and stochastic character of renewable energy sources: Consequences, cost of intermittence and benefit of forecasting. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2018, 87, 96-105.

- Ceballos-Escalera, A.; Molognoni, D.; Bosch-Jimenez, P.; Shahparasti, M.; Bouchakour, S.; Luna, A.; Guisasola, A.; Borràs, E.; Della Pirriera, M. Bioelectrochemical systems for energy storage: A scaled-up power-to-gas approach. Appl Energy 2020, 260, 114138. [CrossRef]

- Novara, D.; Carravetta, A.; McNabola, A.; Ramos, H.M. Cost Model for Pumps as Turbines in Run-of-River and In-Pipe Microhydropower Applications. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2019, 145, 1–9.

- Mérida García, A.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A.; García Morillo, J.; McNabola, A. Energy Recovery Potential in Industrial and Municipal Wastewater Networks Using Micro-Hydropower in Spain. Water 2021, 13, 691. [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, C.; Samora, I.; Manso, P.; Rossi, L.; Heller, P.; Schleiss, A.J. Assessment of hydropower potential in wastewater systems and application to Switzerland. Ren Energy 2017, 113, 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Callegari A.; Boguniewicz-Zablocka, J.; Capodaglio, A.G. Energy recovery and efficiency improvement for an activated sludge, agro-food WWTP upgrade. Water Prac Technol 2018, 13, 4, 909 – 921.

- Hao, X.; Li, J.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Jiang, H.; Liu, R. Energy recovery from wastewater: Heat over organics. Water Res. 2019, 161, 74-77. [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, H.; Spriet, J.; Murali, M.K.; McNabola, A. Heat Recovery from Wastewater—A Review of Available Resource. Water 2021, 13, 1274. [CrossRef]

- Cecconet, D.; Raček J.; Callegari A.; Hlavínek, P. Energy recovery from wastewater: A study on heating and cooling of a multipurpose building with sewage-reclaimed heat energy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1, 116.

- Capodaglio, A.G. Developments and Issues in Renewable Ecofuels and Feedstocks. Energies 2024, 17(14), 3560.

- Myszograj, S.; Bocheński, D.; Mąkowski, M.; Płuciennik-Koropczuk, E. Biogas, Solar and Geothermal Energy—The Way to a Net-Zero Energy Wastewater Treatment Plant—A Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 6898. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Concentration [mg/L] | Minimum reduction [%} | ||

| Article 6(3) - applicable to WWTPs of agglomerates ≥ 1000 PE* (curremtly 2000) | ||||

| BOD5 | 25 | 70-90 (40^) | ||

| COD* | 125 | 75 | ||

| TSS | 35 | 90 | ||

| Article 7 – Applicable to WWTPs with PE capacity§ | ||||

| 10,000-150,000& | ≥150,000 | 10,000-150,000& | ≥150,000 | |

| Total N | 10 (15) | 8 (10) | 80 (70-80) | 80 (70-80) |

| Total P | 0.7 (2) | 0.5 (1) | 87.5 (80) | 80 (80) |

| Article 8 – Applicable to WWTPs with PE capacity ≥ 150,000 PE** | ||||

| Obligation of quaternary treatment (≥ 80%) removal for Amisulprid, Carbamazepine, Citalopram, Clarithromycin, Diclofenac, Hydrochlorothiazide, Metoprolol , Venlafaxine, Benzotriazole, Candesartan, Irbesartan, mixture of 4-Methylbenzotriazole and 5-methyl-benzotriazole. | ||||

| The energy audits referred to in Article 11 shall: | |

| (a) | be based on up-to-date, measured, traceable operational data on energy consumption and (for electricity) load profiles; |

| (b) | comprise a detailed review of the energy consumption profile of buildings or groups of buildings, industrial operations or installations, including transportation; |

| (c) | identify energy efficiency measures to decrease energy consumption; |

| (d) | identify the potential for cost-effective use or production of renewable energy; |

| (e) | build, whenever possible, on life-cycle cost analysis instead of simple payback periods in order to take account of long-term savings, residual values of long-term investments and discount rates; |

| (f) | be proportionate, and sufficiently representative to permit the drawing of a reliable picture of overall energy performance and the reliable identification of the most significant opportunities for improvement. |

| Energy audits shall allow detailed and validated calculations for the proposed measures so as to provide clear information on potential savings. Data used in energy audits shall be storable for historical analysis and tracking performance. | |

| Audit level | Description | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 – Walk-Through Survey | Analysis of previous energy bills and process data (typically up to 3 years), visit to the facility and interview with key decision makers, basic energy measurements. | Report outlining onsite energy use, an energy benchmark, and recommendations for low-cost or no cost energy efficiency improvements. The report will also list possible future energy saving capital projects |

| Level 2 – Energy Survey and Analysis | Builds on a Level 1 audit, including a detailed breakdown on energy use by process, more in-depth measurements, an electrical peak demand analysis, analysis of the savings generated by possible energy efficiency measures. Develops possible changes to control strategies; and lays out a plan for a Level 3 analysis which would require more intensive data collection. | Report similar to that of a Level 1 audit, but including a more detailed energy and cost analysis. |

| Level 3 – Detailed Analysis of Capital-Intensive Modifications | Focuses on further developing capital projects identified as part of the Level 2 audit. This audit requires more data collection as well as energy and process modeling to evaluate the benefits of a particular energy saving capital project, and will include detailed payback calculations. | Design plans for an engineering capital project. |

| Minimum information requirements for Level 1 |

Measurements for Level 2 | |

| Energy bills and process data for the last 3 years, any previous energy audits Agreements with energy providers Site drawings Flow diagrams Climate data Pump and blower curves Copy of the discharge permit Equipment information: Type; Location; Average Load Factor (%); Nameplate kW; Average Load (kW); Motor Efficiency; Estimated Energy Use (kWh/yr); Motor Full Load Amperage (FLA); Average Operating Current; Run-time (day, month, year); Estimated Annual Operating Costs; Dry Weather/Peak Dry Weather/Wet Weather/Emergency Operation (Y/N) |

Most process data may be available from the SCADA system, that should be recording (at least) flows, pressures, and the run time for major equipment. If not available from the SCADA system, use a data logger to record the startup sequence for blowers and major pumps. This provides important data to understand start-up loads that have a large impact on electricity demand charges. Verify pump operation: pump operating points, flow ranges, wet-well levels and maximum and minimum set points. Check actual pump/blower speed and flow versus the respective curve. The operating speed of any rotating equipment should be verified and compared to the one recorded in the SCADA system. Verify temperatures of motors and pump bearings: rotating equipment operating too hot is operating inefficiently, indicating incorrect operation or need for maintenance. All wastewater testing must have taken place in a certified laboratory or with calibrated automatic/proxy (e.g. photometric sensors) systems. Record temperatures of process areas as they not only affect workers’ health, but also equipment performance: temperatures too hot or too cold may be a reason for poorly operating equipment. |

|

| Challenge | Proposed solution | Predicted effect |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive primary intermediate pumping | Implementation of gravity bypass around the homogenization stage | Reduction of ≈50% in pumping energy consumption (250 MWh, or 3.1% of the total WWTP consumption). Investment recovered in 4 years. |

| Biological treatment turbines’ capacity, exceeding oxygen requirements. Unbalanced relationship between basin volumes and flow rates. |

Adjustment of dissolved oxygen set point. Use of fine bubble diffusion systems. Upgrading the servo-controlled gate at the aeration basin feed point. |

Estimated 7.5% reduction in energy consumption in this stage. Expected energy savings between 10-20%, investment recovered in 0.56 years. Negligible implementation costs amortized within a fiscal year. |

| Inefficient sludge recirculation pumping | Pumps replacement | Specific energy consumption reduction by 130-135%. Investment of ≈ 10,000.00 € for the new equipment would save 4475.00 €/y in electricity, allowing repayment in 2.5 years |

| Low efficiency sludge extraction unit | Pumps and piping replacement | Reduction in specific energy consumption between 80-85%, and projected flow rate increase of 60% with an investment of ≈ 10,000.00 €, returned in ≈ 3 years. |

| Biogas energy recovery potential limited by extended aeration AS | Alternative renewable energy production by exploiting geometric head of 14 m at the WWTP discharge point with a minihydropower plant. | Estimated power generation of 36 kW at the average flow of 0.3716 m3/s |

| Current technology |

Alternative technology | Pros | Cons | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sewage collection systems | ||||

| Gravity sewers |

Vacuum Sewers |

Vacuum sewers minimize water use, energy consumption and construction costs. Resulting sewage has higher organics and pollutants concentrations. | Require expert design and construction. | [74, 75] |

| Centrifugal sewage pumps | Smart,variable frequency drives pumps |

Increased pumping efficiency | Increased complexity of variable speed pump scheduling | [76] |

| Level controlled pumps |

Pumping optimization |

Real-time monitoring and modeling optimize pumping cycles. | Extensive network of flow and level sensors, and advanced modeling capabilities required | [77,78] |

| Centralized sewer mains | Decentralized systems |

Can increase water reuse, reduce system's capital cost and operational energy in the pipe network. The “optimal degree of centralization” depends on local consitions. | This approach contrast with current UWWMS paradigms. | [69, 79, 80] |

| Wastewater treatment | ||||

| Aerobic processes |

Anaerobic Processes (e.g. UASB) |

Anaerobic processes dramatically reduce energy consumption, and allow greater energy recovery in biogas form. | Perform optimally with high organic load wastes (e.g. vacuum sewers). Conventional sewage may yield limited biogas volumes in colder climate | [73, 81, 82] |

| Nitrification/ denitrification |

Anammox | Removes nitrogen more energy-efficiently than traditional nitrification/denitrification methods. | Slow process startup. | [83, 84] |

| Activated sludge, MBR | Aerobic granular sludge processes |

AGS processes (Nereda and others) require less operational energy than AS and MBR. May favor resources recovery from sluge. | Proprietary processes, may require long start-up times. | [85, 86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).