1. Introduction

The follicle is the fundamental structural unit in female mammals for maintaining fertility. It is a functional complex composed of oocytes and granulosa cells (GCs). A series of key molecular signals regulate the activation of primordial follicles into primary follicles. Follicular development primarily involves the rapid growth of oocytes and the proliferation of GCs, progressing from a single layer (primary follicle) to two layers (secondary follicle) and then to multiple layers (preantral follicle). Subsequently, under the influence of hormones such as follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormones, the growing follicle develops fluid-filled cavities (antral follicle), while some GCs differentiate into cumulus cells, facilitating oocyte maturation [

1,

2,

3]. The development of mammalian follicles is a complex, multicellular, and highly coordinated biological process. At each stage, a certain number of follicles undergoes elimination and atresia, with only a limited number advancing to the next stage [

4,

5]. The selection of antral follicles is regulated by gonadotropins, whereas the development of growing follicles is influenced not only by genetic factors but also by the microenvironment maintained by GCs [

6,

7,

8].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) primarily include superoxides, peroxides, and free radicals derived from oxygen. These molecules are characterized by their small size and high chemical reactivity. ROS can be generated through various processes, including normal metabolism, exposure to toxic compounds, interactions with metal ions, and radiation [

9,

10]. Under normal physiological conditions, low levels of ROS play essential roles in cellular signal transduction, hormone secretion, and cell growth. However, excessive ROS levels can cause damage to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to intracellular protein denaturation, enzyme inactivation, lipid peroxidation, and DNA degradation, ultimately resulting in cell apoptosis [

11,

12,

13]. Research has shown that elevated ROS concentrations have a detrimental effect on follicular development. For instance, intraperitoneal administration of 12.5 mg/kg of the potent oxidizing agent 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA) in female mice significantly re-duces ovarian weight, the number of growing follicles, and mature oocytes, while markedly increasing the number of atretic follicles [

14]. Emerging evidence suggests that natural antioxidants hold promise for mitigating reproductive oxidative damage, yet few studies have explored the therapeutic potential of iridoid terpenoids in this context.

Natural antioxidants are abundant in various species of Chinese herbal medicine.

Swertiamarin, a secoiridoid glycoside, is extracted from the

Enicostemma genus, specifically from

Enicostemma littorale and

Enicostemma axillare, both of which belong to the

Gentianaceae family [

15,

16]. This compound has been documented to have therapeutic effects on various diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, and neuropathy [

17,

18]. For instance,

Swertiamarin has been shown to alleviate diabetic peripheral neuropathy in rat models by inhibiting the NOX/ROS/NLRP3 signaling pathway [

19]. In addition, it has demonstrated efficacy in reducing oleic acid-induced lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in hepatic steatosis [

20]. In rat models exposed to cigarette smoke,

Swertiamarin has been found to mitigate collagen deposition in the prostate, alleviate oxidative stress, and reduce local inflammation [

21]. Furthermore, it has exhibited protective effects against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury and inflammation, a benefit attributed to its antioxidant properties mediated through the NRF2/HO-1 signaling pathway [

22]. Notably, in insulin-resistant GCs from patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome,

Swertiamarin has been observed to enhance the secretion of estradiol and progesterone while upregulating the expression of genes associated with steroidogenesis, suggesting its potential role in follicular development [

23]. To test this hypothesis, we established a mouse model of 3-NPA-induced oxidative stress, which disrupts follicular development by inducing excessive ROS production. Our study aimed to investigate whether

Swertiamarin supplementation could alleviate 3-NPA-induced follicular abnormalities and elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms involving NRF2/HO-1 pathway activation. This research provides novel insights into the potential application of

Swertiamarin in promoting female reproductive health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Treatment and Sample Collection

All ICR mice utilized in this study were procured from Chengdu Dossy Experimental Animal Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China. Three-week-old female ICR mice, with body weights ranging from 10 g to 12 g, were maintained at a controlled temperature of 22-26°C under a 12 h light/dark cycle, with adequate food and water sources. To examine the effects of Swertiamarin on follicle development, the mice were randomly divided into several groups and received intraperitoneal injections of normal saline solution (Shengao, China), 3-NPA (Macklin, N814665, China), and different concentrations of Swertiamarin (YuanYe, S28017, China) based on their body weight. The groups were designated as follows: (1) Control group, treated with normal saline solution; (2) NPA group, receiving 12.5 mg/kg of 3-NPA; (3) NPA+LSE group, administered 12.5 mg/kg of 3-NPA in conjunction with 25 mg/kg of Swertiamarin; (4) NPA+MSE group, receiving 12.5 mg/kg of 3-NPA along with 50 mg/kg of Swertiamarin; and (5) NPA+HSE group, treated with 12.5 mg/kg of 3-NPA and 100 mg/kg of Swertiamarin. (6) LSE group, administered 25 mg/kg of Swertiamarin; (7) NPA+MSE group, receiving 50 mg/kg of Swertiamarin; and (8) NPA+HSE group, treated with 100 mg/kg of Swertiamarin. Both 3-NPA and Swertiamarin were pre-dissolved in normal saline solution. In the Control group, injections were conducted once daily at 10:00 AM for a duration of 28 days. In the remaining four groups, 3-NPA was administered via intraperitoneal injection to the mice once daily for seven consecutive days. From day 8 to day 28, 3-NPA and varying concentrations of Swertiamarin were administered once daily at 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM, respectively. The weights of the mice were recorded after the last injection. Peripheral blood was collected for detection of hormone levels and the mice were then euthanized. Both ovaries were isolated, weighed and treated differently according to the requirements of subsequent experiments. All experiments were conducted under the permit guidelines established by Southwest Minzu University, and all animal procedures were conducted according to the guiding principles of the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Southwest Minzu University Animal Care and Use (Approval code: SMU-202501019).

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

Mouse ovarian GCs (Biobw, bio-132564, China) were cultured in a commercial culture medium (Procell, CM-M050, China), which containing DMEM/F12, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics, EGF and insulin. GCs were passaged and cultured in cell culture plates. Upon reaching 60-80% confluence, the cells were treated with media containing different concentrations of 3-NPA (0, 5, 10, and 20 mM) or Swertiarexin (0, 10, 25, and 50 μg/mL). The cells were subsequently incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h before additional experiments were conducted.

2.3. Histological Analysis

Ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h before paraffin embedding, and 5 μm paraffin sections were attached to microscope slides for Hematoxylin-eosin staining following the instruction of a Hematoxylin-eosin kit (Solarbio, G1120, China). The staining results were observed and photographed using a ZEISS microscope (Zeiss, LSM800, Germany).

2.4. Superovulation and MⅡoocytes Collection

Each mouse (n=8 per group) was administered an intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU of Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin (PMSG) (Solarbio, P9970, China) on the 28th day to promote follicular development. Following a 48-hour interval, each mouse received an injection of 10 IU of human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) (SANMA, China). The cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were surgically extracted from the oviducts 12 h post-injection. The MⅡoocytes were collected after the removal of GCs, which was achieved by treating the COCs with 0.3% hyaluronidase (Solarbio, H8030, China) for a duration of 2 to 5 min.

2.5. Detection of Estrogen and Progesterone Levels

Each mouse (n=3 per group) was administered an intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU of PMSG. Following a 48-hour interval, each mouse received an injection of 10 IU of hCG. Blood samples were collected from the mice after the simultaneous estrus treatment, with a total volume of 1 mL obtained from each mouse. After standing at room temperature for 30 min, the sample was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was collected. Culture media containing GCs were collected after treatment with 3-NPA and Swertiamarin for 48 h and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant obtained from the experiment was collected for further analysis. The concentrations of estradiol and progesterone were quantified using two enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Meimian, MM-45704M1; MM-0546M1, China), in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. Each experimental procedure was conducted with three technical replicates and three biological replicates.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

Ovarian sections were deparaffinized and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The slides were then incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were observed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss, LSM800, Germany) after staining with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and hematoxylin (Solarbio, G1120, China). The antibodies utilized are listed in

Table S1.

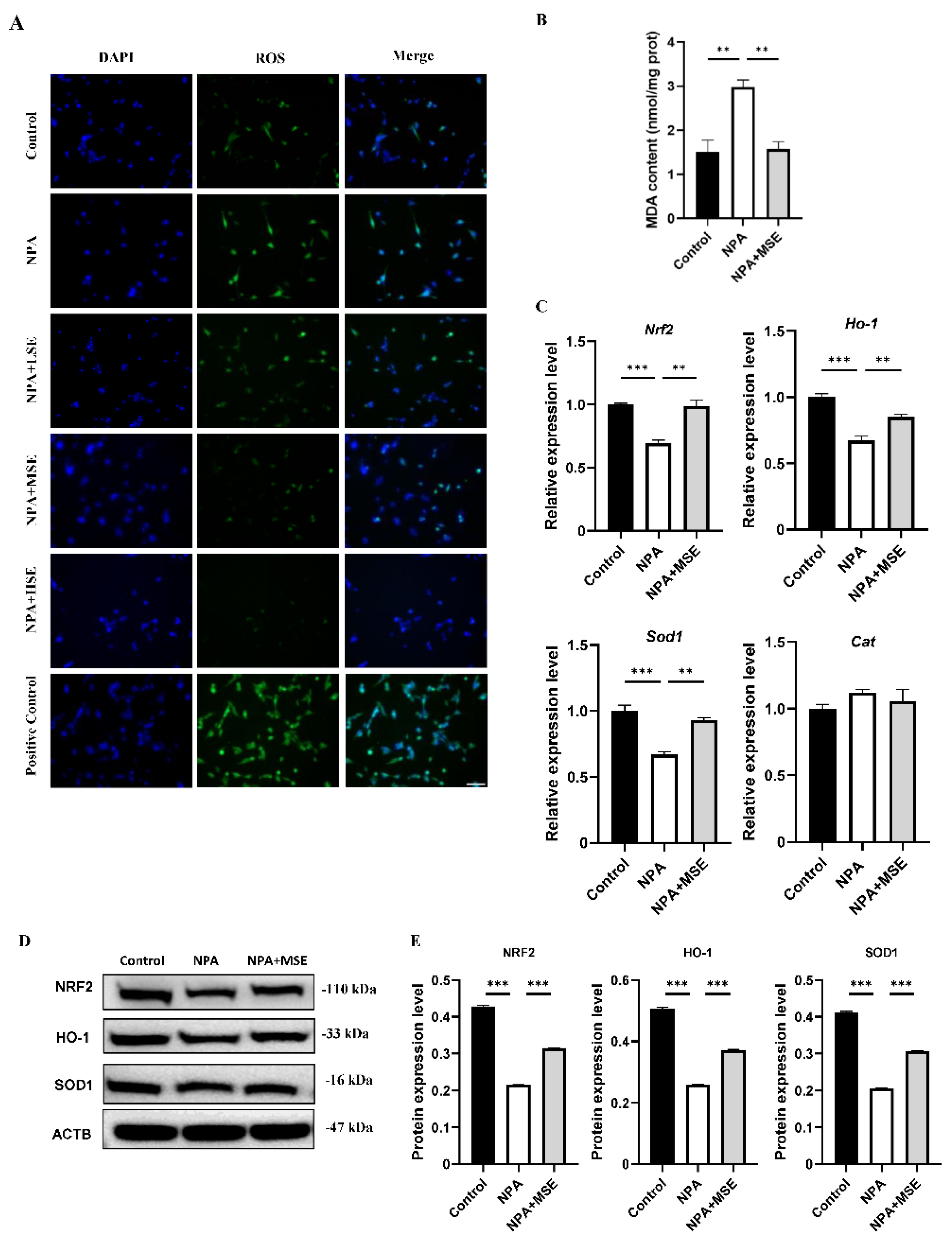

2.7. Measurement of ROS Levels

The levels of ROS in mice ovaries were assayed using the Tissue Reactive Oxygen Species Detection Kit (Biorab, HR8835, China). In brief, 1 mL of homogenization buffer was added for every 50 mg of tissue. The resulting mixtures were then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Subsequently, 190 μL of the supernatant was combined with 10 μL of the O13 probe. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the dark, after which the fluorescence intensity was measured using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Varioskan LUX 3020, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 510 nm and an emission wavelength of 610 nm. A total of 50 μL of the supernatant was extracted and diluted for protein quantification using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Solarbio, PC0020, China). The levels of ROS were expressed as fluorescence intensity per mg of protein.

For GCs, the levels of ROS were evaluated utilizing a Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Assay Kit (Beyotime, s0033s, China). In brief, cells were cultured in 24-well plates and incubated in medium containing 10 μM DCFH-DA probe at 37°C for 20 min. Cells that were treated with Rosup (diluted 1:1000 with DMEM) for a duration of 20 min and subsequently loaded with probes served as positive controls. Subsequently, the cells were stained with Hoechst (Beyotime, C1011, China), and fluorescence was observed using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, LSM800, Germany).

2.8. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase Mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay

TUNEL assay was conducted in accordance with the protocol of the One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (KeyGEN, KGA1406, China). Briefly, ovarian sections were deparaffinized and Proteinase K was applied dropwise to each slide, followed by being incubated at 37°C for 30 min. For GCs, the cell slides were immersed in 4% PFA and fixed for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 was added to the slides, allowing for permeation for 5 min at room temperature. A total of 50 µL of TdTase solution was administered to each slide, after which the sections were placed in a humidified chamber for 60 min at 37°C in the dark. Following this, 50 µL of Streptavidin-Fluorescein solution was added to each slide, and the slides were again placed in a humidified chamber for 30 min at 37°C in dark. The nuclei were subsequently re-stained with DAPI (Biosharp, BL105A, China), and the slides were washed with PBS before being sealed. Finally, the slides were photographed under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, LSM800, Germany).

2.9. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from ovaries and GCs in each group by TRIzol Reagent (Vazyme, R401, China). RNA purity was assessed with an ultraviolet-visible photometer (Shimadzu, Bio-Spec-nano, Japan). Briefly, 1 mL TRIzol Reagent and steel beads were added to the ovaries of each group, thoroughly ground in a High-throughput tissue grinder, and centrifuged with 12000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh centrifuge tube, followed by the addition of an equal volume of ice-cold isopropanol. Following a 10 min incubation at room temperature, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resultant RNA pellet was washed twice with 75% ethanol and subsequently dissolved in 30 μL of nuclease-free water. RNA purity and concentration were quantified using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (BioSpec-nano, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized with the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, R223, China) following the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCR was conducted using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q311-01, China) as previously described [

24].

Actb was set as the reference gene, and the fold change in gene expression was quantified using the comparative C

T method. The primers utilized are detailed in

Table S2.

2.10. Western Blotting

Proteins from ovaries and GCs were extracted using the RIPA Lysis Buffer (Servicebio, G2002, China), which contained 1% phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (Servicebio, G2008, China), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the mouse ovaries of each group were thoroughly ground into powder in mortars containing liquid nitrogen, and then the powder was transferred to a centrifuge tube containing RIPA lysis solution and lysed on ice for 40 min. Then, the centrifuge tubes were centrifuged with 12000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was taken to detect the concentration of protein. The protein concentration was quantified using the BCA Protein Quantification Kit (Oriscience, PD101, China), and a total of 20 μg of protein was loaded into each well. The samples were subjected to separation via 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 2 h and then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. A BeyoECL Star Kit (Beyotime, P0018S, China) was used to visualize the immunoreactive bands. Images were captured with an invitrogen iBright CL750 Imaging System (Thermo, USA). ACTB was served as a protein loading control. The antibodies utilized are listed in

Table S1.

2.11. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

GCs were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of approximately 1×104 cells per well. Subsequently, cell proliferation rate was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Kit (MCE, HY-K0301, China) following the manufacturer's instruction. CCK-8 utilizes a water-soluble tetrazolium salt, WST-8 ((2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium)), to evaluate cell proliferation. The optical density (OD) value at 450 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™, 1530-00183, USA). The cell viability was calculated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.12. Determination of MDA Content

Ovarian tissues were homogenized in an ice water bath and subsequently centrifuged at 8,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant. GCs were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 5×105 cells/mL. Following treatment with 3-NPA and different concentrations of Swertiamarin, the cells were collected and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was then removed, and a small volume of PBS was added to the cell pellet. The cells were then disrupted using an ultrasonic cell crusher (JY92-IIN, SCIENTZ, China) in an ice water bath. The MDA content was quantified using an MDA Content Assay Kit (Solarbio, BC0025, China) following the manufacturer's protocol.

2.13. EdU Staining

EdU staining on GCs with different treatment was conducted utilizing the BeyoClick™ EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 488 (Beyotime, C0071S, China) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, GCs were incubated with EdU (10 mM final concentration) solution at 37 ℃ for 2 h. Subsequently, the cells were fixed in 4% PFA and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 min. After being washed three times in wash buffer (PBS containing 3% BSA), click reaction solution was added and the cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min. The nuclei were then stained with 10 μg/mL Hoechst (Solarbio, C0031, China) and imaged using a ZEISS microscope (Zeiss, LSM800, Germany).

2.14. Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed using the one-way ANOVA (with Tukey's multiple comparison test as the post-hoc test). All data were expressed as mean ± standard error (Mean ± SEM).

4. Discussion

Excessive oxidative stress, both intracellularly and extracellularly, is a significant contributor to the abnormal development of ovarian follicles and the subsequent decline in female fertility capacity [

25,

26,

27].

Swertiamarin, a natural iridoid terpenoid compound, demonstrates a variety of beneficial properties, including anti-hyperlipidemic, anti-diabetic, and antioxidant effects. This study investigates the protective effects of

Swertiamarin on impaired follicular development induced by oxidative stress, thereby offering a novel strategy to solve reproductive damage induced by oxidative stress.

GCs are consistently involved in active proliferation and metabolic processes during follicular growth and exhibit heightened sensitivity to oxidative stress [

28,

29]. This sensitivity was evidenced by the suppression of secondary, preantral, and antral follicles following the administration of the oxidant 3-NPA in murine models. Subsequent supplementation with

Swertiamarin resulted in a significant enhancement in the development of growing follicles, as well as a marked improvement in the survival capacity of GCs, both

in vivo and

in vitro. Additionally, the expression levels of several genes specifically expressed by GCs that regulate follicular development were restored, suggesting that

Swertiamarin may alleviate the defective follicle development under oxidative stress by enhancing the viability of GCs. However, given the critical role of oocytes in follicle development, although

Swertiamarin does not significantly enhance the expression of

Gdf9 and

Bmp15, two oocyte-specific genes involved in follicular development in mice treated with 3-NPA, the potential effect of

Swertiamarin on the development and maturation of oocytes under conditions of oxidative stress warrants further investigation in subsequent studies.

Follicle development, progressing from secondary to preantral follicle stages, primarily depends on oocyte growth and GC proliferation. Estrogen and progesterone mainly regulate the maturation of antral follicles and ovulation [

30,

31,

32]. Here we found that

Swertiamarin and 3-NPA combined treatment significantly increased the number of antral follicles and mature oocytes in conditions of oxidative stress. However,

Swertiamarin did not exhibit a significant impact on the levels of estrogen and progesterone secreted by GCs under oxidative stress, both

in vivo and

in vitro. This finding suggests that the promoting effect of

Swertiamarin on the maturation of antral follicles and oocytes under oxidative stress is largely attributable to its facilitation of follicle development at earlier stages. Notably,

Swertiamarin has been reported to increase the secretion of estrogen and progesterone in GCs of patients with insulin-resistant poly cystic ovarian syndrome [

23], indicating that

Swertiamarin may exert inconsistent regulatory effects on steroid hormone synthesis in GCs under varying stress conditions.

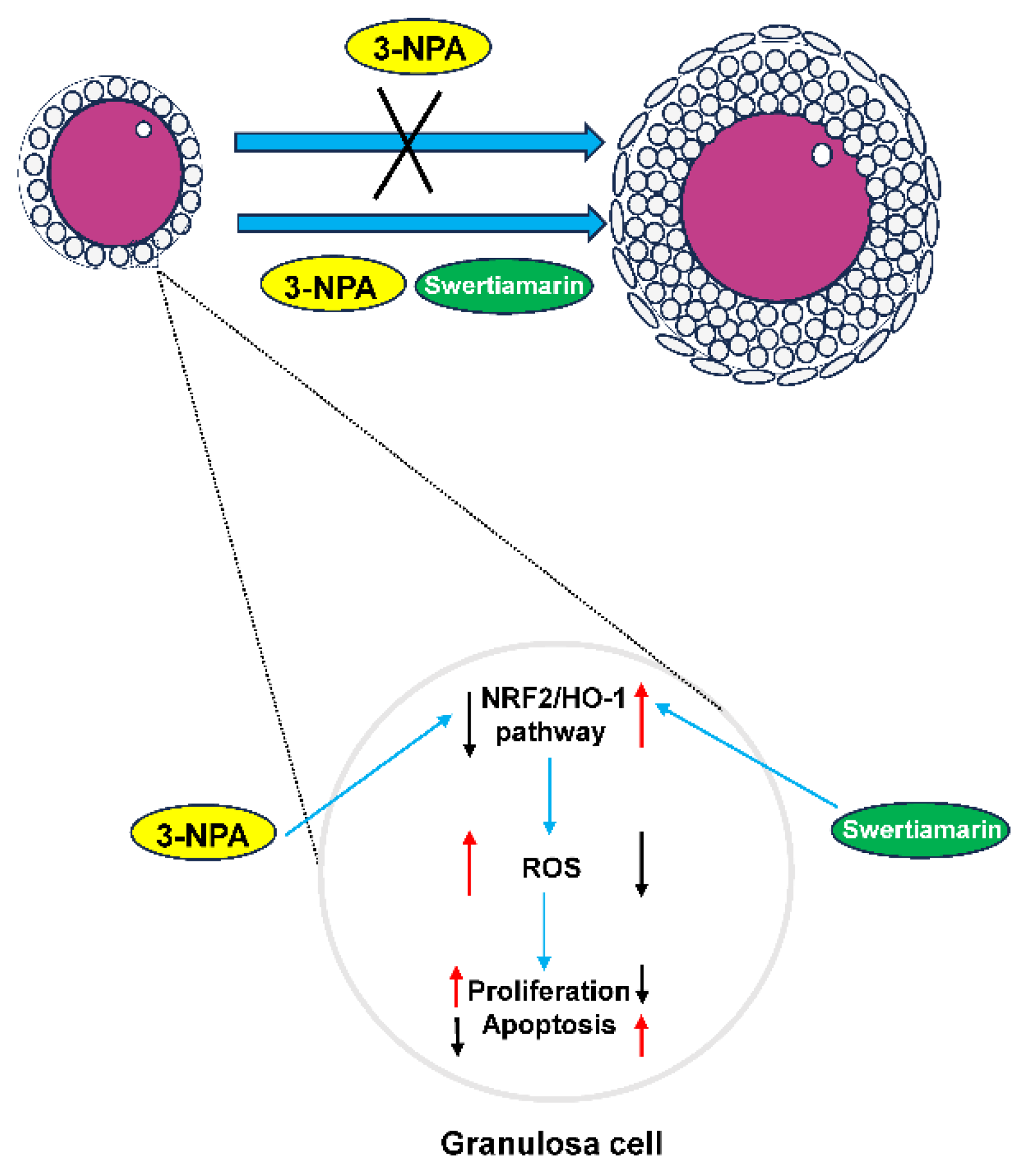

The NRF2/HO-1 signaling pathway is acknowledged as a vital antioxidant mechanism that protects ovarian GCs from oxidative stress. Existing evidence indicates that the activation of NRF2 significantly increases the levels and activities of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD and CAT, leads to a reduction in intracellular ROS production and GCs apoptosis [

33,

34]. As a natural antioxidant,

Swertiamarin has exhibited protective effects against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury and inflammation, attributed to its antioxidant properties via the NRF2/HO-1 pathway in rat models [

22]. In the present study, we demonstrate that

Swertiamarin effectively reduces oxidative stress and enhances the expression and activity of key components of the NRF2/HO-1 pathway, including NRF2, HO-1, SOD1, and CAT, in both ovaries and GCs. These findings provide evidence that

Swertiamarin alleviates oxidative stress in GCs, at least in part, by up-regulating the NRF2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

Author Contributions

Luoyu Mo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing–original draft. Gan Yang: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. Anjun Zhou: Methodology, Investigation. Dongju Liu: Formal analysis. Huai Zhang: Conceptualization. Fuyong Li: Methodology, Investigation. Ziqian Huang: Investigation, Validation. Dini Zhang: Validation. Xianrong Xiong: Investigation, Validation. Yan Xiong: Investigation, Validation. Honghong He: Formal analysis. Jian Li: Funding acquisition. Shi Yin: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing–original draft.