1. Introduction

The number of single-person households has steadily increased across both developed and developing countries, marking a significant demographic shift with widespread social psychological, and behavioral implications. According to the OECD (2022), single living has become increasingly common in nations such as Japan, the United States, Germany, and Nordic countries. The underlying causes of this trend are multifaceted, including increased life expectancy, urbanization, women's economic independence, delayed marriage, lower fertility rates, and the growing emphasis on individualism and self-actualization (Esteve et al., 2020; Golubev, 2023; Gurko, 2024). While this lifestyle trend may signal autonomy for some, it can also lead to reduced social contact and support, both of which are critical behavioral factors influencing mental health.

This global trend has raised growing concern about the mental health of individuals living alone. Numerous studies have identified that people who live alone are more vulnerable to mental health challenges, particularly depression, due to diminished social interaction and support (Chou et al., 2006; Stahl et al., 2017). Depression, as a behavioral health outcome, often develops and persists within broader socioeconomic and environmental contexts. Depression, one of the most prevalent mental disorders worldwide, is a leading cause of disability and reduced quality of life. In particular, socioeconomic deprivation—defined as cumulative disadvantages across domains such as income, housing, healthcare, and social participation—has been widely recognized as a structural contributor to mental health disparities (Cermakova et al., 2020; Polak et al., 2022). While the specific manifestations of deprivation may vary by country, its psychological consequences—such as chronic stress, hopelessness, and social exclusion.

Importantly, the behavioral manifestations of depression, such as withdrawal, emotional dysregulation, and diminished motivation, are shaped by one's social environment and life-stage circumstances. This is especially relevant for single-person households, where socioeconomic vulnerability may hinder access to coping resources. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these vulnerabilities, disproportionately affecting those living alone through social isolation and reduced access to formal and informal support networks (Dong et al., 2023; McElroy et al., 2023).

Although existing studies have investigated the link between deprivation and depression, many have focused on specific subgroups defined by age or gender, often using cross-sectional designs (Heo et al., 2010; Polak et al., 2022; Seo, 2015). As single-person households continue to grow in number and diversity, especially across all age groups, it is essential to examine how the experience of deprivation affects depressive symptom trajectories over time. Moreover, given the varying life circumstances and motivations for living alone at different life stages—ranging from economic independence in young adulthood to widowhood in later life—there is a need for life-course-oriented analyses.

Although this study utilizes South Korean data, its analytic framework—integrating latent growth modeling and multidimensional deprivation within a life-course perspective—provides insights that are transferable to other countries where single-person households are rapidly increasing. As countries worldwide grapple with similar demographic and psychosocial challenges, the findings of this study may inform targeted mental health interventions for single-living populations beyond the Korean context.

Current Study

This study examines longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms among single-person households, spanning both the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods. Recognizing the heterogeneity within this population, the study investigates how various domains of socioeconomic deprivation influence the trajectories of depressive symptoms across different stages of adulthood—namely, young adulthood, middle adulthood, and old age. By adopting a life-course perspective, this research aims to provide empirical evidence that can inform age-specific policies and targeted interventions to address depression among single-person households.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study used data from the nationally representative Korea Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS), conducted annually since 2006. This survey is jointly managed by the Korean Institute of Social and Health Affairs and the Social Welfare Research Institute of Seoul National University. KOWEPS provides an extensive array of data on families and individuals, encompassing areas such as social service requirements, healthcare utilization, economic and demographic characteristics, income sources, and subjective assessments of emotional and behavioral health. Initial sampling employed a probability-based selection of 7,072 households from 30,000, yielding responses from 14,463 individuals. For this research, data from waves 13 (2018) to 18 (2023) were utilized, focusing on variables consistently measured using standardized tools. The analysis specifically targeted single-person households, restricted to individuals aged 20 years and older. The final analysis focused on 2,094 single-person households to reflect the distinct characteristics of this demographic.

2.2. Measures

This secondary analysis utilized validated Korean versions of instruments used in prior research.

Depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 11-item CESD-11, a validated scale for depressive symptoms in the general population (Radloff, 1977). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = always), and higher scores in each domain indicate greater levels of depression. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha at the six time points ranged from 0.900 to 0.916.

Socioeconomic deprivation. This study categorized socioeconomic deprivation into six domains: basic living area, housing area, social security area, employment/economic area, social area, and health/medical area. The score obtained by adding up the values of each item in the deprivation area (0 = not deprived, 1 = deprived) as shown in

Table 1 was used for analysis. A higher total score for each area means more deprivation experience.

Control variable. Based on previous research, age, gender (0=female, 1=male) education level (0 = less than high school, 1 = over college) and average monthly income were used as control variables that affect the relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic deprivation items.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic deprivation items.

| Domain |

Question |

| Basic living area |

An experience of running out of food due to financial difficulties but not having money to buy more |

| An experience of not being able to afford food due to financial difficulties, which made it impossible to have a balanced diet |

| An experience of failing to pay utility bills on time |

| An experience of having electricity, phone, or water services cut off due to unpaid taxes. |

| Housing area |

An experience of moving out due to being unable to pay rent or having rent overdue for more than two months |

| An experience of being unable to use heating during winter due to a lack of money |

| Whether the residence is located above ground level |

| Whether it is a durable permanent structure with main structural components made of materials that are resistant to heat, fire, thermal radiation, and moisture |

| Whether it is equipped with proper soundproofing, ventilation, lighting, and heating facilities |

| Whether it is unsuitable for living due to noise, vibrations, odors, or air pollution |

| Whether it is safe from natural disasters such as tsunamis, floods, landslides, and cliff collapses |

| Whether the kitchen, bathroom, and bathing facilities can be used exclusively |

| Social security area |

Whether enrolled in a public pension plan |

| Whether enrolled in health insurance |

Employment/Economic

area |

Whether engaged in economic activity |

| Whether total living expenses exceed the minimum cost of living |

| Whether there is experience working in a hazardous environment |

| Social area |

Whether satisfied with family relationships |

| Whether satisfied with social relationships |

| Health/Medical area |

An experience of being unable to visit a hospital due to a lack of money |

| Subjective health status |

2.3. Data Analysis

Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) was conducted using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation in AMOS 23 (Bollen & Curran, 2006). The analysis followed a two-stage approach. First, the unique developmental trajectory of depressive symptoms over time among single-person households was examined. Second, the influence of socioeconomic deprivation factors on this trajectory was assessed. Socioeconomic deprivation factors measured at wave 13 were included as exogenous variables in the model. Model fit was assessed using standard indices: χ², TLI, CFI, and RMSEA.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics and key variables. Most single-person households were aged 65 or older, female, had lower middle school education, and reported an annual disposable income below 1,999 thousand won.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic and key variables (N = 2,094).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic and key variables (N = 2,094).

| Variable |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Age |

Aged 20–44 years |

234 |

11.2 |

| Aged 45–64 years |

321 |

15.3 |

| Over aged 65 years |

1,539 |

73.5 |

| Education |

middle school or lower |

1,515 |

72.3 |

| High school or higher |

579 |

27.7 |

| Sex |

Male |

521 |

24.9 |

| Female |

1,573 |

75.1 |

| Income |

less than 999

thousand won |

842 |

40.2 |

1000 to less than 1999

thousand won |

754 |

36.0 |

2000 to less than 2999

thousand won |

251 |

12.0 |

3000 to less than 3999

thousand won |

128 |

6.1 |

| Over 4000 thousand won |

119 |

5.6 |

| Variable |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

| Wave 1 depressive symptoms |

0 |

32 |

5.81 |

5.51 |

1.18 |

1.32 |

| Wave 2 depressive symptoms |

0 |

32 |

5.82 |

5.53 |

1.15 |

1.01 |

| Wave 3 depressive symptoms |

0 |

31 |

5.91 |

5.73 |

1.16 |

0.96 |

| Wave 4 depressive symptoms |

0 |

33 |

6.23 |

5.77 |

1.15 |

1.23 |

| Wave 5 depressive symptoms |

0 |

32 |

6.51 |

5.75 |

1.04 |

0.73 |

| Wave 6 depressive symptoms |

0 |

28 |

5.94 |

5.57 |

1.20 |

1.15 |

| Basic living area |

0 |

4 |

0.13 |

0.43 |

3.65 |

4.35 |

| Housing area |

0 |

8 |

0.58 |

0.18 |

2.48 |

2.22 |

| Social security area |

0 |

2 |

1.45 |

0.62 |

-0.68 |

-0.51 |

| Employment/Economic area |

0 |

3 |

0.67 |

0.49 |

-0.49 |

-1.19 |

| Social area |

0 |

2 |

0.14 |

0.39 |

2.73 |

3.10 |

| Health/Medical area |

0 |

2 |

0.38 |

0.49 |

0.69 |

-1.11 |

3.2. Unconditional Model of Depressive Symptoms in Single-Person Households

An unconditional six-year model was estimated before incorporating predictors. The linear growth model fit the data better than the no-growth model, as indicated by χ² = 189.959 (p < .001), TLI = .947, CFI = .947, and RMSEA = .062 (

Table 3).

The estimated mean intercept for depressive symptoms was 5.934 (SE = .110), with significant variance (15.866, SE = .801; p < .001), indicating considerable individual differences in baseline symptom levels. For the linear slope of depressive symptoms, the mean (SE) was .130 (.029), with a variance of .416 (.052), both statistically significant. This suggests a meaningful average increase in depressive symptoms over time, as well as significant variability in the rate of change among individuals. Specifically, the estimated mean level of depressive symptoms at wave 1 was 5.934, with an annual increase of .130.

A significant negative covariance between the intercept and slope (

Table 4) suggests that individuals with higher initial depressive symptoms experienced a slower progression over time compared to those with lower baseline levels.

3.3. The Socioeconomic Deprivation and Depressive Symptoms Trajectory

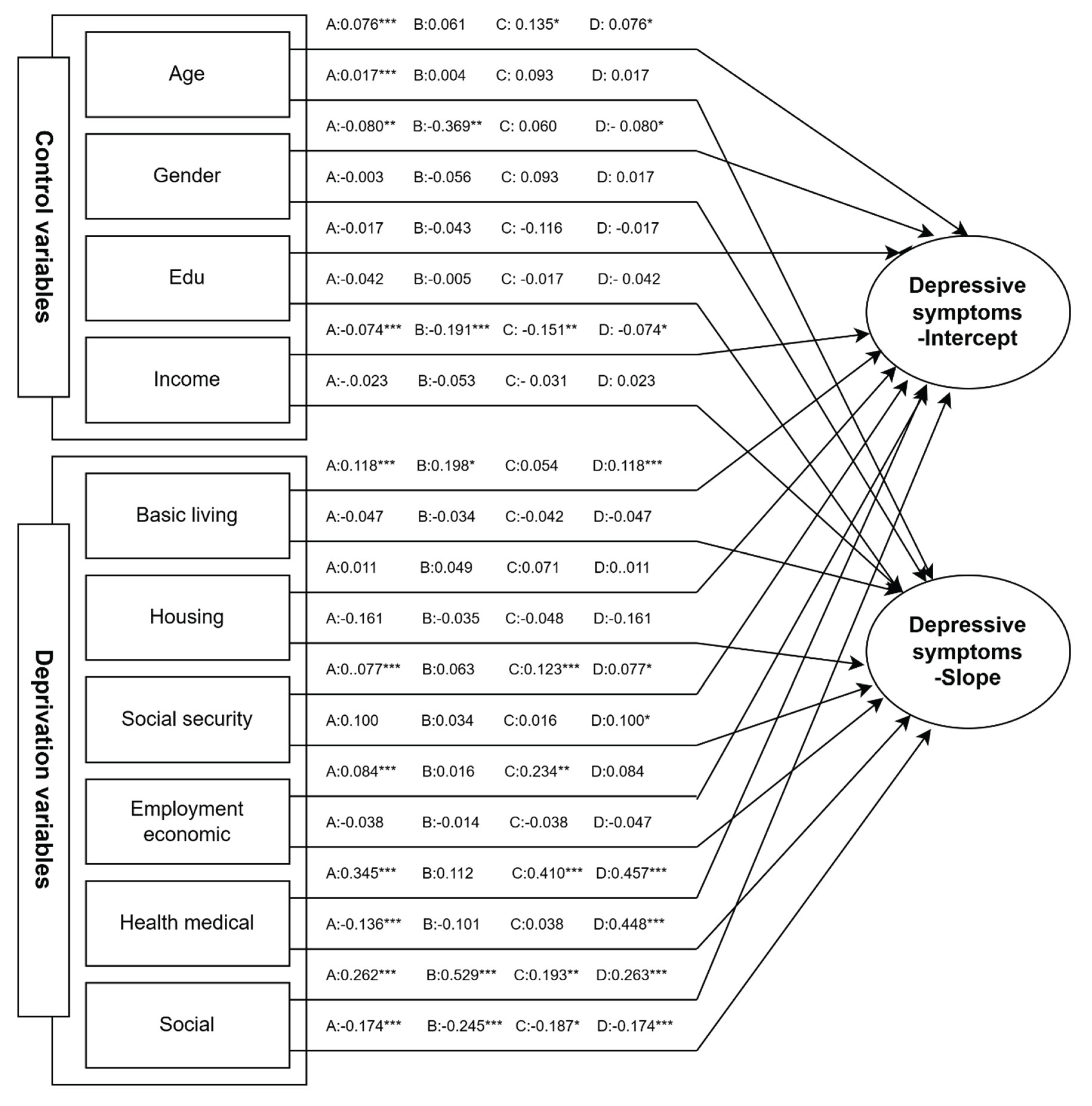

The conditional model incorporating socioeconomic deprivation as time-invariant covariates demonstrated improved model fit compared to the unconditional model. The model exhibited good fit indices (χ² = 287.173, p < .001; TLI = .940; CFI = .973; RMSEA = .042), indicating strong explanatory power. Standardized estimates are presented in

Figure 1.

All socioeconomic deprivation domains—except for housing—were significantly associated with the trajectories of depressive symptoms. Additionally, age, gender, and income were significant control variables. Deprivation in the basic living (β = .118, p < .001), social security (β = .102, p < .01), and employment/economic (β = .064, p < .05) domains significantly predicted only the intercept of depressive symptoms. This suggests that individuals experiencing higher deprivation in these areas reported greater initial levels of depressive symptoms. In contrast, social and health/medical deprivation significantly influenced both the intercept and slope of depressive symptoms (social: β = .092, p < .01; β = .034, p < .05; health: β = .110, p < .001; β = .034, p < .05). Notably, social deprivation had a strong effect on both the intercept (β = .262, p < .001) and the slope (β = −.174, p < .001), indicating that individuals with higher social deprivation had higher initial depressive symptoms, but a slower increase over time.

Among the control variables, age (β = .076, p < .05) and gender (β = −.080, p < .001) significantly predicted the intercept, with older individuals and females exhibiting higher initial levels of depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

LGM’s predictors of single-person households’ depressive symptoms. Note. A: all single-person households, B: young adulthood, C: middle adulthood, D: old age.

Figure 1.

LGM’s predictors of single-person households’ depressive symptoms. Note. A: all single-person households, B: young adulthood, C: middle adulthood, D: old age.

3.4. Multiple Group Comparison

A multiple-group latent growth modeling analysis was conducted to examine whether the effects of socioeconomic deprivation on the developmental trajectory of depressive symptoms differed across life stages—young adulthood, middle adulthood, and old age.

Figure 1 summarizes the results by age group.

Among young adults, deprivation in the basic living domain significantly influenced the intercept of depressive symptoms, indicating that greater deprivation was associated with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms. Notably, social deprivation significantly predicted both the intercept and the slope of depressive symptoms. Individuals with higher social deprivation experienced greater initial depressive symptoms but a slower increase in symptoms over time compared to those with lower social deprivation. Among the control variables, income and gender were significant: lower income and being female were associated with higher initial depressive symptom levels.

For middle-aged single-person households, deprivation in the health/medical, employment/economic, and social security domains significantly predicted the intercept only, indicating that individuals with higher levels of deprivation reported higher initial levels of depressive symptoms. Social deprivation again significantly influenced both the intercept and the slope. As with young adults, those with greater social deprivation showed higher initial symptoms but a less steep increase over time. Among control variables, age and income significantly predicted initial levels of depressive symptoms; older age and lower income were associated with higher initial depressive symptoms.

Among older adults, deprivation in the health/medical, social security, and social domains significantly influenced both the intercept and slope of depressive symptoms. This indicates that older individuals with greater deprivation had higher baseline symptoms and a slower rate of increase. Interestingly, housing deprivation significantly affected only the slope, suggesting that those in more deprived housing environments experienced a slower increase in depressive symptoms over time. In contrast, deprivation in the employment/economic and basic living domains significantly predicted only the intercept. Control variables such as income, gender, and age were all significant predictors of the initial level of depressive symptoms; older age, female gender, and lower income were associated with higher initial symptom levels.

Taken together, these findings indicate that the impact of socioeconomic deprivation on depressive symptom trajectories varies by life stage. However, social deprivation consistently emerged as the only predictor influencing both the intercept and slope across all age groups. For young adults, basic living deprivation significantly affected the intercept only. For middle-aged adults, health/medical, employment/economic, and social security deprivation emerged as additional predictors of initial symptom levels. In older adults, health/medical and social security deprivation significantly influenced both the initial levels and changes in depressive symptoms over time. Furthermore, housing deprivation was uniquely significant among older adults, influencing the rate of change in depressive symptoms—a pattern not observed in other age groups.

4. Discussion

This study examined the developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms among single-person households and assessed how different domains of socioeconomic deprivation influence these trajectories across the life course. The results revealed a steady increase in depressive symptoms over time, with distinct patterns of influence depending on the age group— highlighting how life-stage-specific vulnerabilities contribute to behavioral health disparities.

First, the continued escalation of symptoms—both before and after the COVID-19 pandemic—confirms that solo-living adults constitute a behaviorally at-risk group due to heightened exposure to social isolation and reduced informal support (Heo & Kim, 2023; Jeong, Ryu, & Woo, 2024). This reinforces the idea that depression, in this context, is not only a clinical condition but also a socially driven behavioral outcome.

Second, social deprivation emerged as the most robust and consistent predictor of depressive symptoms across all age groups. Individuals with unsatisfactory family and social relationships showed both higher baseline symptoms and more rapid increases over time. From a behavioral science lens, the absence of reinforcement mechanisms—such as empathy, belonging, and mutual interaction—erodes emotional regulation and resilience. Accordingly, interventions should promote social connectivity tailored to life stage: community programs for younger adults, social role restoration for the middle-aged, and structured public care engagement for older individuals.

Third, among young adults, basic living deprivation—such as food or utility insecurity—was a key driver of initial depressive symptoms. This finding aligns with research on the financial precarity of young single-person households (Ko, 2017). Lower income and male gender further compounded risk, underscoring the need for targeted subsidies and support systems that alleviate early economic stressors.

Fourth, in middle adulthood, multiple deprivation domains—including social, health, economic, and social security—were associated with both baseline and trajectory outcomes. This reflects cumulative life stressors such as job instability, physical decline, and inadequate retirement preparation. Interventions at this stage should emphasize structural safeguards: employment support, accessible healthcare, and flexible mental health service delivery.

Fifth, among older adults, health/medical and social security deprivation were strong predictors of both initial levels and progression of symptoms. Persistent increases suggest heightened sensitivity to chronic illness, rising medical costs, and reduced financial independence. Policy initiatives should focus on home-based care, financial assistance for medical needs, and supportive aging-in-place services.

Notably, housing deprivation was especially relevant for older adults, influencing the slope of depressive symptoms. Unsafe or inadequate housing conditions (e.g., poor insulation, limited accessibility) can compound isolation and hinder recovery. Enhancing housing quality and expanding age-appropriate public housing options should be central to mental health strategies for older populations.

Importantly, behavioral science-based interventions—such as nudging (e.g., automated check-in prompts), digital self-monitoring tools, and community reinforcement programs—have been effective in reducing depressive symptoms and enhancing social engagement in vulnerable populations (Firth et al., 2017; Milkman et al., 2021). Integrating these approaches into mental health policy can improve early detection and tailored care, especially when adapted by age and digital access.

Collectively, these findings support a behavioral model in which depressive symptoms serve as markers of structural and social stress, rather than solely psychological dysfunction. They emphasize the need to address upstream determinants—social support, economic stability, and environmental quality—to improve long-term mental health trajectories among adults living alone across the life span.

Limitation

This study has several limitations. First, this study relied on secondary data (KOWEPS), which limited the scope and precision of available covariates. Second, the model did not incorporate time-varying covariates, which may have influenced symptom changes over time. Future studies should adopt dynamic models with refined measures to improve causal interpretation. Third, as this study relied solely on South Korean data, its generalizability may be limited. Nonetheless, given the global rise of single-person households, future cross-national studies are warranted to explore cultural differences in depressive symptom trajectories. Lastly, the life-course behavioral model proposed here may offer a comparative framework for examining depression in countries undergoing rapid demographic aging and increasing solo living. It bridges behavioral science and social policy, offering a platform for future international application.

5. Conclusions

As single-person households continue to rise globally, the findings of this study offer important insights for international mental health policy, particularly in the context of demographic aging and growing social inequality. This study provides empirical evidence that depressive symptoms among solo-living adults are shaped by diverse domains of socioeconomic deprivation, with clearly differentiated patterns by age group across the life course.

By conceptualizing depressive symptoms as behavioral indicators of structural stress, this research underscores the need to adopt a life-course approach in both research and interventions. Notably, social deprivation consistently affected both baseline levels and trajectories of depressive symptoms, reaffirming the vital role of social relationships. Other deprivation domains—such as basic living, medical, economic, and social security—showed differentiated effects across age groups, supporting the need for tailored, age-sensitive strategies.

These results reinforce the understanding that depression among single-person households is not merely a psychological issue but a structural concern, deeply rooted in social and environmental contexts. Accordingly, mental health policies should integrate behavioral science frameworks that address broader social determinants, including housing stability, income security, and service access.

Future interventions should apply behavioral techniques—such as nudging, digital self-monitoring, and community reinforcement—to enhance early detection, foster engagement, and tailor support throughout the life course. By embedding these tools into a comprehensive behavioral policy framework, practitioners and policymakers can more effectively reduce depression risks and promote well-being among solo-living populations.

References

- Bollen, K. A., & Curran, P. J. (2006). Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. Wiley.

- Cermakova, P., Andrýsková, L., Brázdil, M., & Mareckova, K. (2020). Socioeconomic deprivation in early life and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adulthood: Mediating role of hippocampal connectivity. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K. C.-K., & Chou, K. L. (2019). Poverty, deprivation, and depressive symptoms among older adults in Hong Kong. Aging & Mental Health, 23(1), 22–29. [CrossRef]

- Chou, K. L., Ho, A. H., & Chi, I. (2006). Living alone and depression in Chinese older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 10(6), 583–591. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-X., Li, D., Miao, Y., Zhang, T., Wu, Y., & Pan, C. (2023). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 333, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Eggert, L., Schröder, J., & Lotzin, A. (2023). Living alone is related to depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Esteve, A., Reher, D., Treviño, R., Zueras, P., & Turu, A. (2020). Living alone over the life course: Cross-national variations on an emerging issue. Population and Development Review, 46(1), 169–189. [CrossRef]

- Firth, J., Torous, J., Nicholas, J., Carney, R., Pratap, A., Rosenbaum, S., & Sarris, J. (2017). The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Golubev, O. V. (2023). Understanding living alone among the young- and middle-aged in China (1990–2010): A gender perspective. The History of the Family, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D. J., Peters, T. J., Kammerling, R. M., & Brooks, J. (1995). Relation between parasuicide, suicide, psychiatric admissions, and socioeconomic deprivation. BMJ, 311(6999), 226–230. [CrossRef]

- Gurko, T. A. (2024). Trends and social reasons of living alone. Sociology of the Family, 5, 113–127. [CrossRef]

- Heo, J. H., Cho, Y. T., & Kwon, S. M. (2010). The effects of socioeconomic deprivations on health. Health and Social Welfare Review, 44(2), 93–120.

- Holmgren, J. L., Carlson, J. A., Gallo, L. C., Doede, A. L., Jankowska, M. M., Sallis, J. F., Perreira, K. M., Andersson, L., Talavera, G. A., Castañeda, S. F., Garcia, M. L., & Allison, M. A. (2021). Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and depression symptoms in adults from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). American Journal of Community Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Im, Y. J., & Park, M. H. (2018). The effect of socioeconomic deprivation on depression of middle-aged single-person households. Social Science Research Review Kyungsung University, 34(1), 187–206.

- Jung, K. H., Lim, J. S., Kim, H. Y., Nam, S. H., Lee, Y. K., Lee, J. H., Jung, E. J., & Jin, M. J. (2012). Policy implications of changes in family structure: Focused on the increase of single person households in Korea. KISA.

- Kim, H., & Shin, J. (2024). Effects of socioeconomic deprivation in single-person households on depression: The moderating effect of age. Journal of Korean Family Resource Management Association, 28(3), 29–40. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., You, J. W., & Song, I. H. (2015). Socioeconomic deprivation on depressive mood: Analysis of the moderating effect of age. Health and Social Welfare Review, 35(3), 42–70.

- Ko, A. R., Jeong, K. H., & Shin, B. K. (2018). Deprivations on depression of middle-aged single-person household: A focus on the comparison between single-person and multi-person households. Korean Journal of Family Social Work, 59, 55–90.

- Lee, W., & Im, R. (2014). Study for the relationship between perceptions of inequality and deprivation in Korea: Focusing on the mediating role of depression. Health and Social Welfare Review, 34(4), 93–122. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. W. (2016). A longitudinal study on the interaction between deprivation, depression, and conflict among the Korean low-income household. Paper presented at The Korean Welfare Panel Convention, 25–32.

- McElroy, E., Herrett, E., Patel, K. K., Piehlmaier, D., Di Gessa, G., Huggins, C. F., Green, M. J., Kwong, A. S. F., Thompson, E. J., Zhu, J., Mansfield, K. E., Silverwood, R. J., Mansfield, R., Maddock, J., Mathur, R., Costello, R., Matthews, A., Tazare, J., Henderson, A. D., … Patalay, P. (2023). Living alone and mental health: Parallel analyses in UK longitudinal population surveys and electronic health records prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Mental Health, 26. [CrossRef]

- Milkman, K. L., Patel, M. S., Gandhi, L., Graci, H. N., Gromet, D. M., Ho, H., Kay, J. S., Lee, T. W., Akinola, M., Beshears, J., Bogard, J. E., Buttenheim, A. M., Chabris, C. F., Chapman, G. B., Duckworth, A. L., Goldstein, N. J., Goren, A., Halpern, S. D., Hare, T. A.,... Volpp, K. G. (2021). A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s appointment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(20), e2101165118. [CrossRef]

- Moisio, P. (2004). A latent class application to the multidimensional measurement of poverty. Quality and Quantity, 38, 703–717. [CrossRef]

- Ostler, K., Thompson, C., Kinmonth, A. L., Peveler, R. C., Stevens, L., & Stevens, A. (2001). Influence of socio-economic deprivation on the prevalence and outcome of depression in primary care. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178 (1), 12–17. [CrossRef]

- Polak, M., Nowicki, G., Naylor, K., Piekarski, R., & Ślusarska, B. (2022). The prevalence of depression symptoms and their socioeconomic and health predictors in a local community with a high deprivation: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11797. [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y. S. (2015). The effect of socio-economic deprivation on depression according to the age of the elderly. Journal of the Korean Gerontological Society, 35(1), 99–117.

- Sohn, Y. J. (2018). A study on the influence of socio-economic deprivation on depression: Focusing on latent growth modeling analysis. Journal of the Korean Data Analysis Society, 20(6), 3227–3238.

- Stahl, S. T., Beach, S. R., Musa, D., & Schulz, R. (2017). Living alone and depression: The modifying role of the perceived neighborhood environment. Aging & Mental Health, 21(10), 1065–1071. [CrossRef]

- Swigost, A. (2017). Approaches towards social deprivation: Reviewing measurement methods. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series, 38, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Treiber, L. A., Emerson, C., & Shackleford, J. (2024). COVID for one: Identifying obstacles to self-management of COVID-19 for single adults. Journal of Patient Experience, 11. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. University of California Press.

- Yeo, E. (2020). The effect of material deprivation on depression: Focused on effect by life cycle and area of deprivation. Health and Social Welfare Review, 40(2), 60–84. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).