Exploring the Relationship Between Sleep Disturbance, Psychosocial Stress, Socioeconomic Status on Self-Perceived Mental Health Among Aging Adults in the United States

Older adults’ mental health has become a central concern in public health, policy, and clinical practice, particularly in light of shifting global demographics. As the proportion of older individuals continues to rise in many societies, mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and chronic stress are increasingly recognized as critical determinants of quality of life and functional independence (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). In the United States, adults aged 65 and older are projected to outnumber those under 18 by the year 2034, signaling a historic shift in the nation’s age structure (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Despite increasing longevity, older adults often live with substantial burdens of emotional distress and mental health symptoms, highlighting a pressing need for evidence-based interventions and comprehensive assessments of risk factors.

This growing public health challenge is exacerbated by systemic issues in care delivery, including underdiagnosis, stigmatization, and inadequate access to geriatric mental health services. Mental health conditions in older adults are often misattributed to "normal aging" rather than treated as legitimate and addressable concerns (Bartels et al., 2003). Moreover, the convergence of physical frailty, cognitive decline, and chronic illnesses can mask or intensify mental health symptoms, leading to a cycle of unrecognized and untreated psychological distress. These gaps in assessment and intervention are particularly dangerous given the profound consequences of untreated mental illness in this population—including increased mortality risk, poor quality of life, and higher healthcare utilization (Gellis & Bruce, 2010).

Self-rated mental health (SRMH) offers a valuable insight into understanding these burdens. While often dismissed as subjective, SRMH has been shown to predict clinical outcomes, including hospitalizations, functional decline, and mortality (Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Schnittker & Bacak, 2014). As such, identifying variables that shape SRMH among aging populations is of considerable empirical and practical significance. Traditional models have emphasized structural determinants such as income, education, and health insurance status. However, emerging literature suggests that modifiable behavioral and psychological factors—particularly sleep quality and perceived stress—may offer more immediate targets for intervention (Minkel et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2018).

Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent in older populations, with studies indicating that as many as 50% of older adults report significant issues with sleep initiation, maintenance, or duration (Foley et al., 1995). These disturbances have been linked to reduced emotional regulation, greater susceptibility to depressive symptoms, and impairments in cognitive functioning (Spira et al., 2014; Wulff et al., 2010). Aging-related physiological changes, such as declines in melatonin production, increased sleep fragmentation, and altered circadian rhythms, may exacerbate these outcomes (Duffy et al., 2015). Compounding these challenges, older adults may underreport sleep-related issues or normalize them as part of the aging process, thereby delaying or avoiding treatment.

Psychosocial stress is another modifiable factor that has gained attention in geriatric mental health. Stress among older adults is multifactorial, stemming from caregiving responsibilities, financial constraints, social isolation, or the cumulative effects of chronic illness (Lupien et al., 2009). Chronic stress can dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, compromise immune functioning, and increase vulnerability to psychiatric disorders (McEwen, 1998). The biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977) provides a useful framework for understanding how stress interacts with biological and environmental variables to influence mental well-being, and it supports the inclusion of stress measures in models of SRMH.

Although complex, sleep and stress stand out as areas where meaningful improvements can be made through targeted, evidence-based approaches. Behavioral therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and structured physical activity programs have all demonstrated efficacy in improving sleep quality and reducing perceived stress (Irwin et al., 2013; Grossman et al., 2004). Unlike static demographic traits, these variables are modifiable, suggesting that interventions targeting them may yield significant improvements in subjective well-being. Furthermore, public education initiatives aimed at improving awareness of sleep hygiene and stress management techniques could provide low-cost, high-impact strategies to support older adult well-being (Espie et al., 2012).

In addition to sleep and stress, socioeconomic status (SES) plays a significant role in shaping self-rated mental health. SES—commonly measured through educational attainment and income levels—is a well-established structural determinant of overall health. Research shows that individuals with higher levels of education tend to exhibit stronger health literacy, which helps them better interpret medical information, make informed decisions, and engage in preventive behaviors that support long-term well-being (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2010). While it may be difficult to address the effects of SES later in life, especially when individuals may already be experiencing mental health challenges, these findings underscore the critical impact of education on healthy aging. This highlights the need for policies that invest in education early on to help prepare younger generations for improved mental health outcomes as they age.

Given the complex interrelationships among these variables, data-driven techniques such as exploratory factor analysis (EFA) offer valuable tools for identifying latent constructs that shape mental health outcomes. EFA enables researchers to reduce large sets of observed variables into fewer unobserved variables, or "factors," which capture underlying dimensions of experience or behavior (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2011). This study used EFA to examine a range of survey variables capturing demographic characteristics, behavioral health metrics, and psychological constructs, with the goal of identifying latent dimensions that predict SRMH in older adults. EFA was chosen over other dimensionality reduction techniques due to its strength in uncovering complex latent structures without predefined categories, making it particularly useful in exploratory public health research (Costello & Osborne, 2005).

The present study aims to build on this body of work by applying EFA to a nationally representative survey of older adults, followed by regression analysis to determine how the extracted factors predict self-rated mental health. The hypothesis is that latent factors related to sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress will emerge as significant predictors of SRMH, independent of demographic and socioeconomic variables. In doing so, the study seeks to highlight modifiable targets for intervention and provide a foundation for evidence-based strategies that promote healthy psychological aging.

Literature Review

Mental health in older adults is a multifaceted issue influenced by biological, psychological, and socioeconomic factors. One major area of research has focused on the role of sleep disturbance. Numerous studies have found a strong link between poor sleep and worse mental health outcomes in aging populations. For example, Zhang et al. (2019) and Wolkove et al. (2007) highlighted how disrupted sleep quality contributes to increased psychological distress. Grandner (2019) extended this by emphasizing the broader public health implications of sleep as a foundational health behavior. Gulia and Kumar (2018) reported that sleep disorders in elderly individuals are often overlooked and undertreated, and Luyster et al. (2015) called for better screening and diagnostic practices for sleep problems in clinical settings. Collectively, these studies show that sleep quality is a pivotal factor in older adults' mental well-being, though few have quantified sleep disturbance alongside other risk domains using a latent modeling approach.

Psychosocial stress has also been recognized as a determinant of mental health. McEwen (2004) proposed that stress acts as both a direct and indirect physiological threat to brain health and mood regulation. The American Psychological Association (2020) reported rising stress levels among older Americans, pointing to economic pressure, health concerns, and caregiving responsibilities. Lu et al. (2019) demonstrated that social support can moderate the negative effects of stress on depression, especially among elderly populations living alone. However, these findings are primarily based on bivariate or mediation frameworks and seldom consider stress in combination with other latent constructs such as sleep and SES. This highlights a methodological gap that the current study addresses by including stress as one of several co-occurring latent factors.

Socioeconomic status (SES)—including income, education, and employment stability—has been long associated with mental health disparities. Hudson (2005) tested both the social causation and social selection hypotheses and concluded that low SES contributes causally to poor mental health. Xue et al. (2021) explored how health-promoting behaviors mediate the impact of SES on depression, providing evidence that the effects of SES are partially modifiable. Almeida et al. (2017) found that gender and age intersect with income and education to shape stress hormone responses, which in turn affect mental wellness. Despite this rich literature, SES is still often measured using a few surface-level indicators and not incorporated into more advanced, factor-driven analyses—something this study attempts to rectify.

Access to healthcare, especially through Medicare or supplemental coverage, has also been shown to influence mental health service use and perceived well-being. Reports by SAMHSA (2021) and CMS (2020) stress the importance of integrated behavioral health models to close access gaps in older populations. However, these sources are typically policy-focused and do not offer statistical validation of the association between health coverage and self-perceived mental health. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019) further recommend integrating social care into healthcare delivery, but again fall short of providing data-backed models to quantify this link.

In summary, the literature makes clear that sleep, stress, income, and healthcare access each play important roles in older adults' mental health. However, these domains have largely been studied in isolation. Few studies integrate them into a unified framework to explore how they collectively shape SRMH. The present study addresses this gap by creating latent constructs for each domain using factor analysis and comparing their contributions in a regression model. This integrative approach allows for a clearer understanding of which domains are most predictive of mental health disparities among older adults and helps set data-informed priorities for future public health interventions.

How This Study Adds Value

Unlike most prior studies that examine each domain in isolation, this study uniquely applies factor analysis to derive latent variables representing sleep, stress, SES, and health access. These latent factors are then used in a multiple regression model to assess their relative influence on SRMH among older adults in the U.S. The inclusion of self-rated mental health (SRMH) as a primary outcome measure adds additional value, as it reflects the subjective perception of mental wellness, which has been shown to be a reliable predictor of morbidity and healthcare utilization but is often overlooked in quantitative models.

This research is one of the few to explore the intersection of these four domains—sleep disturbance, psychosocial stress, socioeconomic status, and healthcare access—in a single, unified model. By applying a factor-analytic approach to data from a large, nationally representative survey (NPHA), the study not only enhances statistical power but also ensures the findings are generalizable to the broader U.S. aging population. In doing so, it addresses a critical gap in the literature: the lack of integrated analyses examining how modifiable behavioral and structural factors jointly shape mental health outcomes. By explaining over 50% of the variance in mental health scores and highlighting sleep disturbance as the strongest predictor, this study offers an evidence-based framework for identifying and prioritizing the most impactful intervention areas.

Furthermore, these insights have direct implications for policy and practice. The results support targeted public health initiatives that go beyond demographic risk profiling, encouraging investments in sleep hygiene education, stress reduction programs, and expanded access to mental health services for older adults. This study thus contributes not only to academic knowledge but also to the formulation of effective, data-informed strategies aimed at improving quality of life among a rapidly growing and vulnerable population.

Data Description

The dataset used in this analysis originates from the National Poll on Healthy Aging (NPHA), a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults aged 50 to 80. The data were collected by NORC at the University of Chicago using the AmeriSpeak Panel and made available through the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR; NORC, 2023). The survey aims to gather insights into aging-related health, behavior, and well-being, with special emphasis on physical health, mental health, healthcare utilization, and socioeconomic characteristics.

The full dataset includes over 2,000 individual responses across dozens of survey items. For the purposes of this analysis, a subset of 17 variables was selected based on their theoretical relevance to self-rated mental health (Q2). These variables span several domains, including sleep behavior and quality (e.g., Q13A, Q14_1, Q14_6, Q14_8, Q15), healthcare engagement (e.g., Q34, Q41_3, Q46), psychosocial stress indicators, demographic information (e.g., PPGENDER, PPHHHEAD, PPETHM), and socioeconomic status (e.g., PPEDUC, PPINCIMP). A full listing and description of these variables can be found in

Appendix A.

Variable formats varied across the dataset. Some were ordinal (e.g., Q2 on a scale of 1-5), others were nominal categorical (e.g., employment status, race), and a few were continuous or count-based (e.g., number of medications taken, time since last dental visit). All items were numerically coded, with specific values denoting refusals, inapplicable responses, or missing data. For example, values such as -1 (Refused), -7 (Don't know), or extreme placeholders (97-999) were designated as missing. These entries were recoded as NaN and excluded or imputed during preprocessing (Acock, 2016).

Each selected variable was chosen to represent a plausible predictor of mental health, either through direct mechanisms such as sleep quality or through indirect influences such as financial stress or access to care. The ultimate analytic dataset consisted of complete cases for these 17 items following imputation and standardization, ensuring methodological consistency for downstream factor analysis and regression modeling.

Methods

This study was designed to explore and quantify the relationships between various health, socioeconomic, and demographic factors and self-rated mental health among older adults. The analytic strategy centered on applying dimensionality reduction techniques to a complex set of survey data to uncover underlying constructs-termed latent factors-that may help explain differences in perceived mental health status.

The methodological approach was guided by both theory and empirical rigor. Factor analysis was chosen for its ability to reduce redundancy in correlated variables while uncovering shared variance, allowing the identification of unobservable but influential constructs (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2011). These latent variables are presumed to influence multiple observed indicators, thereby offering a parsimonious representation of key domains such as sleep behavior, psychosocial stress, and socioeconomic background.

Multiple diagnostic and statistical procedures were employed to validate the suitability of the dataset for factor analytic techniques. These included tests of sampling adequacy and data structure, such as the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (Kaiser, 1974; Bartlett, 1954), followed by extraction methods and rotation strategies to produce interpretable factor solutions. The outcome of this process was the derivation of factor scores that were subsequently employed as predictors in regression modeling. The goal was to examine the extent to which these latent constructs could explain variance in self-reported mental health, thereby offering insight into high-impact intervention targets for health policy and practice.

This methodological design integrates data preprocessing, factor extraction, and predictive modeling within a cohesive framework tailored to the exploration of complex survey data.

The current analysis used data from the National Poll on Healthy Aging (NPHA), consisting of self-reported responses from older adults across a range of health, behavioral, and demographic domains. The primary aim was to reduce dimensionality in the dataset and identify latent constructs that predict variation in perceived mental health (Q2). A total of 17 survey variables were selected for analysis based on theoretical and empirical relevance to constructs such as sleep quality, psychosocial stress, education, healthcare access, and demographic background.

All data analysis was conducted using Python within a Google Colab environment. Libraries such as pandas, factor_analyzer, scikit-learn, and statsmodels were utilized for data preprocessing, factor extraction, and regression modeling.

AI Assistance Disclosure:

The Python code used in this study was developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model by OpenAI. All code was verified, modified, and executed by the author to ensure accuracy and appropriateness for the research objectives.

Data Cleaning and Preparation

Prior to conducting factor analysis, the dataset underwent a rigorous data cleaning process. Invalid or non-substantive responses, including refusals and out-of-range values (e.g., -1 = Refused, -7 = Don't know, 97-999 = placeholders), were coded as missing values (NaN). Variables exhibiting zero variance were excluded, as they do not contribute meaningful information for factor differentiation.

To address missing data, median imputation was employed. This method is robust against outliers and appropriate for non-normally distributed survey data (Rubin, 1987). All selected variables were subsequently standardized using z-score normalization. This transformation ensures that each variable contributes equally to the factor extraction process, regardless of its original scale.

Sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test, which yielded a value of 0.73-deemed acceptable for factor analysis. In addition, Bartlett's Test of Sphericity returned a statistically significant result (p < .001), indicating that sufficient correlations existed among variables to justify proceeding with factor analysis.

Factor Analysis

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was employed to identify latent constructs underlying the observed survey responses. The method utilized principal axis factoring with varimax rotation to enhance the interpretability of the factor structure (Thurstone, 1947). The number of factors to extract was guided by multiple established criteria: eigenvalues greater than 1.0 (Kaiser criterion), inspection of the scree plot which revealed a clear "elbow" after six factors, and the theoretical coherence of the emerging factor structures (Costello & Osborne, 2005).

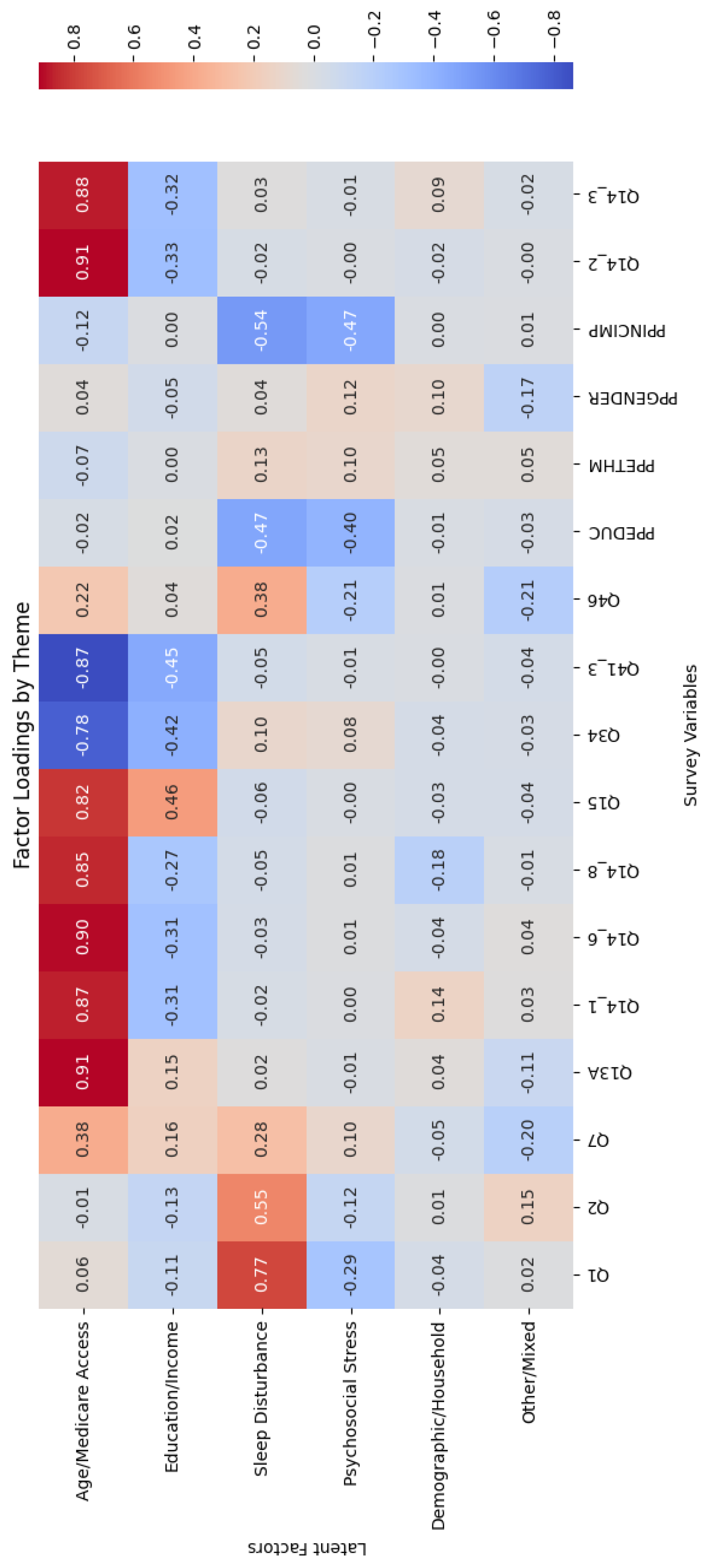

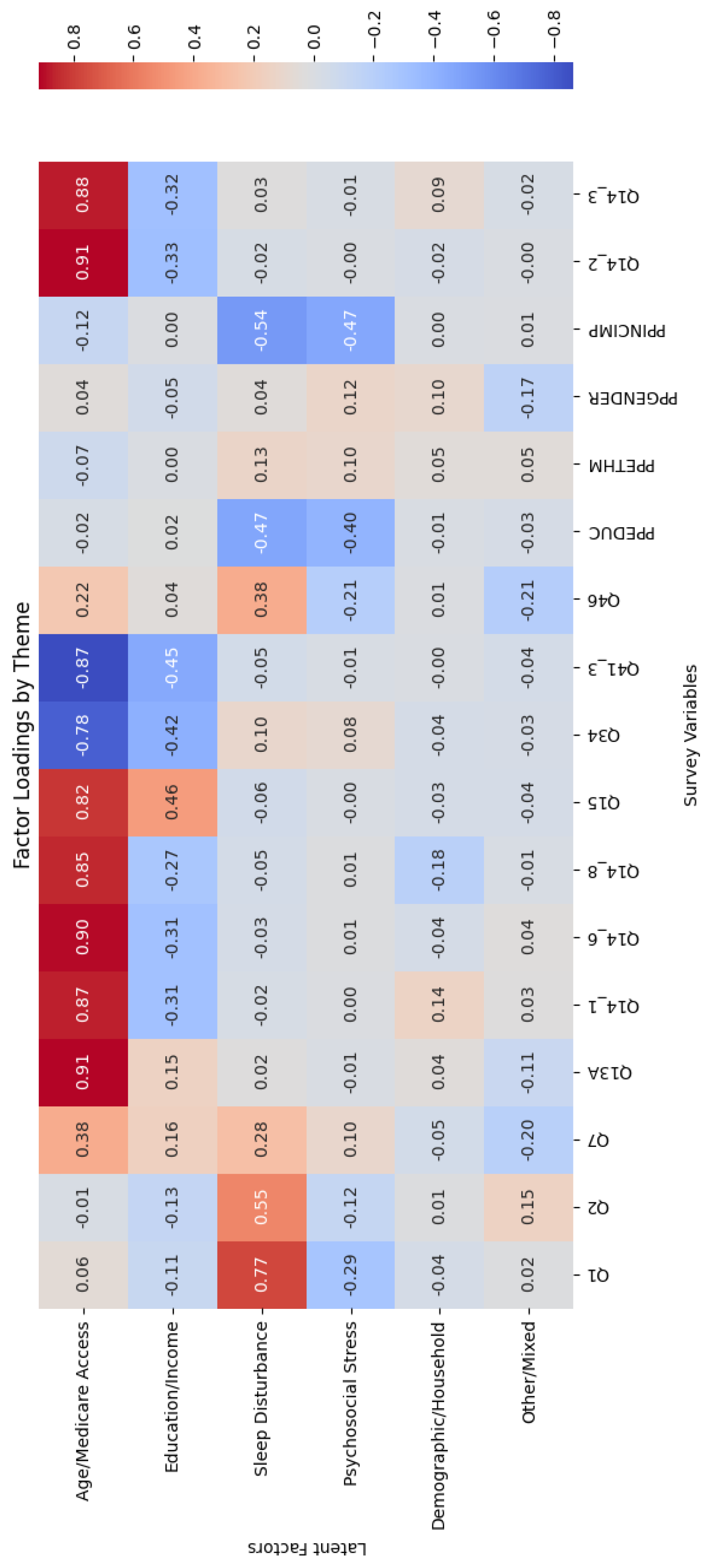

Each factor was labeled based on its highest-loading variables:

Factor 1: Age/Medicare Access - Included Q46 (prescription count), Q34 (dental visit timing), and Q41_3 (dental-related sleep issues).

Factor 2: Education/Income - Dominated by PPEDUC (education level) and PPINCIMP (income).

Factor 3: Sleep Disturbance - Comprised Q13A (difficulty falling asleep), Q14_1, Q14_6, Q14_8 (reasons for sleep trouble), and Q15 (subjective sleep quality).

Factor 4: Psychosocial Stress - Included Q14_2, Q14_3 (stress-related causes of poor sleep) and PPETHM (ethnicity).

Factor 5: Demographic/Household - Initially included variables like PPGENDER and PPHHHEAD, though this factor was later excluded from regression modeling due to low interpretive value.

Factor 6: Other/Mixed - Captured residual variance with no coherent thematic pattern.

A heatmap of factor loadings confirmed the cluster integrity of variables within each latent construct (

Appendix B).

Regression Analysis

Factor scores for each respondent were calculated and used as predictors in a multiple linear regression model with Q2 (self-rated mental health) as the dependent variable. The regression was conducted to assess the extent to which the latent constructs derived from the factor analysis contributed to individual differences in mental health ratings. By regressing Q2 on the factor scores, the model quantified the predictive utility of each latent variable, offering insight into which psychosocial and structural factors most influence perceived mental health (Cohen et al., 2003).

The model was estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) via the statsmodels library, which provided full diagnostics including regression coefficients, standard errors, p-values, and confidence intervals. The inclusion of p-values served a critical purpose: it allowed for the statistical testing of the null hypothesis that a given predictor has no effect on the dependent variable. A p-value below the threshold of 0.05 was interpreted as evidence that the associated factor had a statistically significant relationship with mental health outcomes, implying that the observed effect was unlikely due to random variation alone (Field, 2013).

Model performance was evaluated by the R-squared (R²) statistic, which indicated the proportion of variance in Q2 explained by the model. Additionally, univariate regressions were conducted for each factor individually to compute standalone R² contributions. This decomposition enabled identification of which specific latent factors independently held the most explanatory power.

These statistical evaluations were essential for understanding the relative contribution of each factor and validating the robustness of the model. Multicollinearity checks showed no severe intercorrelation between factors, due in part to the orthogonal rotation applied during factor extraction. Residual diagnostics (linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality) confirmed that model assumptions were adequately met.

In summary, this analytic workflow allowed for a comprehensive and interpretable examination of mental health determinants using latent constructs derived from survey data. Factor analysis not only reduced complexity but also illuminated actionable public health insights, particularly regarding the roles of sleep health and socioeconomic conditions.

Results

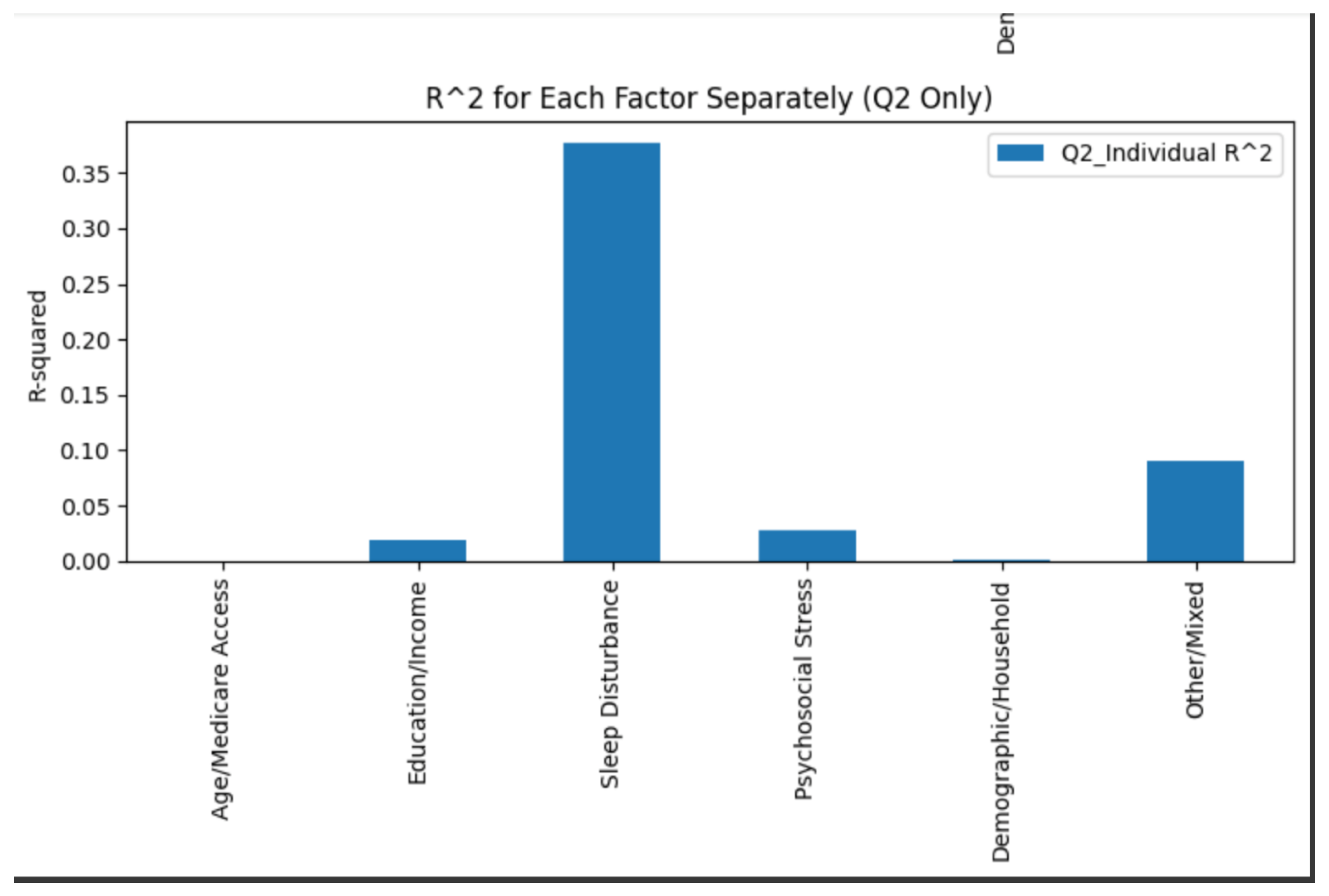

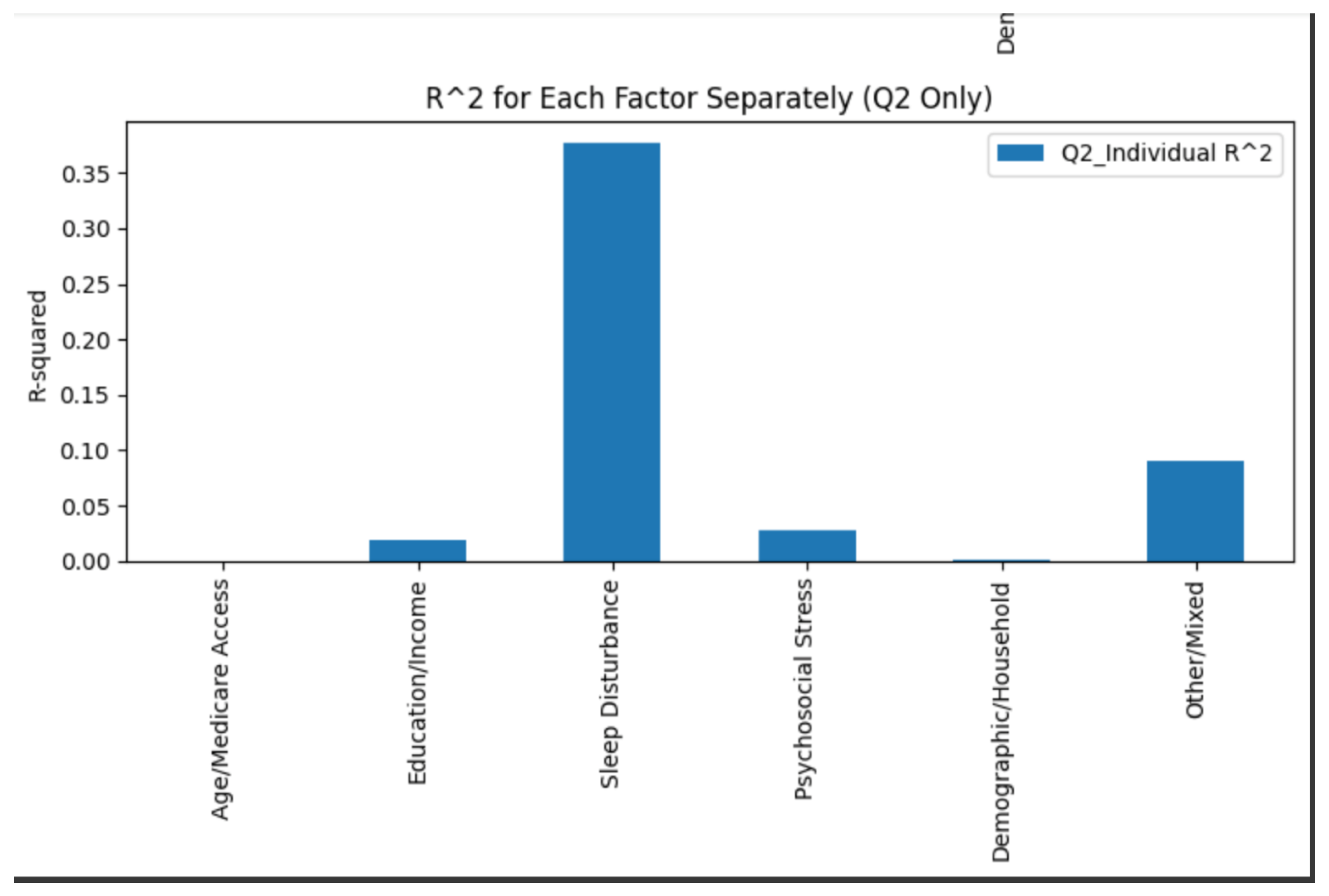

The multiple regression model using six retained latent factors as predictors of self-rated mental health (Q2) produced an overall R² value of 0.516, indicating that approximately 52% of the variance in mental health scores was explained by the model. This suggests that the combined latent constructs derived from exploratory factor analysis provide a meaningful explanation for variation in perceived mental well-being among older adults.

Among the six factors, the Sleep Disturbance factor demonstrated the strongest individual association with Q2, with a statistically significant positive coefficient (β = 0.618, p < .001). This result indicates that higher levels of reported sleep difficulties are strongly and directly associated with lower self-rated mental health. The predictive strength of this factor is further supported by a univariate R² of 0.377, meaning that sleep disturbance alone explains roughly 38% of the variability in mental health scores.

The Psychosocial Stress factor also emerged as a statistically significant predictor of self-rated mental health (β = -0.206, p < .001), indicating that greater emotional strain and stress-related sleep or behavioral disruptions are independently and negatively associated with mental well-being. This factor accounted for approximately 2.8% of the variance in Q2 scores (R² = 0.028). The strength and direction of this association highlight the measurable impact of chronic psychological stress on older adults’ subjective perceptions of their mental health.

The Education/Income factor demonstrated a statistically significant negative association with Q2 (β = -0.1305, p < .001), showing that lower levels of educational attainment and income correspond to lower mental health scores. While its contribution to overall model fit was more modest (individual R² = 0.020), the effect was still meaningful in the context of a multifactorial framework, reinforcing longstanding evidence linking socioeconomic status to health outcomes.

The Other/Mixed factor also showed a strong positive relationship with Q2 (β = 0.5337, p < .001), although due to the mixed composition of variables contributing to this latent factor, interpretation is more limited. Nonetheless, its high standardized coefficient suggests a notable contribution to perceived mental health.

Conversely, the Age/Medicare Access factor (β = -0.0113, p = .408) and the Demographic/Household Composition factor (β = 0.0342, p = .144) were not statistically significant. Both exhibited negligible effect sizes and contributed virtually nothing to the explained variance (ΔR² ≈ 0.000). These findings suggest that, in the presence of more proximal and potentially modifiable behavioral or psychological influences, demographic variables such as age, household structure, and Medicare access offer limited explanatory power for subjective mental health.

Descriptive statistics indicated that the average Q2 score was 3.4 (SD = 1.1), reflecting moderately positive self-perceived mental health across the sample. Notably, the Sleep Disturbance factor had the highest variability among all predictors, which aligns with its strong contribution to the model.

Individual R² analyses conducted via separate univariate regressions confirmed that Sleep Disturbance accounted for the greatest portion of the variance (R² = 0.377), followed by the Other/Mixed factor (R² = 0.090), and Psychosocial Stress (R² = 0.028). In contrast, Education/Income (R² = 0.020) had a more limited impact, while Age/Medicare Access and Demographic/Household factors each explained effectively none of the variance (both R² = 0.000).

A bar plot of standardized regression coefficients visually reinforced these findings (

Appendix C), with the Sleep Disturbance and Other/Mixed factors exerting the most substantial influence on Q2, followed by more moderate contributions from Psychosocial Stress and Education/Income.

Regression diagnostics confirmed that multicollinearity was not a concern (VIF < 2 for all predictors), residuals were approximately normally distributed, and no violations of linearity or homoscedasticity were detected.

Subgroup analyses stratified by XSENIOR status (ages 50–64 vs. 65–80) revealed largely consistent factor score distributions, with a slight increase in Psychosocial Stress observed among the younger cohort. However, these differences were not large enough to alter the direction or magnitude of the regression coefficients, indicating that the model was stable across age subgroups.

Taken together, the regression findings emphasize the particularly strong roles of sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress in shaping older adults' self-rated mental health. While socioeconomic status, represented by education and income, contributes in a smaller but still significant way, structural demographic variables such as age and household composition were not significant predictors in the presence of more immediate behavioral and emotional factors.

Discussion

The present study investigated the influence of latent constructs derived through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on self-rated mental health (Q2) among older adults. The multiple regression model accounted for approximately 52% of the variance in Q2 scores, indicating a moderately strong fit and suggesting that the included factors capture key dimensions of psychological well-being in later life. This level of explanatory power is notable in psychosocial research, where mental health outcomes are shaped by a wide range of interdependent biological, behavioral, and contextual factors. It demonstrates that while self-rated mental health is a complex construct, much of its variation in this sample can be understood through a focused set of latent domains derived from survey data.

Among the five extracted constructs, sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress emerged as the most significant predictors. Sleep disturbance held the strongest association, followed by psychosocial stress, while other factors such as age/Medicare access and education/income were comparatively less influential in the final model. Importantly, the prominence of behavioral and emotional variables over static demographic traits reinforces the view that modifiable factors—not age or background alone—play a central role in shaping perceived mental well-being. This distinction supports more dynamic approaches to public health interventions and mental health services for older adults.

The results also reflect the interrelatedness of physical, mental, and social dimensions of aging. While demographic variables like age and SES are often emphasized in public health, their effects may operate indirectly—through mediators such as sleep, stress exposure, and health behavior patterns. The inclusion of latent constructs in this model helps capture these underlying processes more meaningfully than single variables, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the drivers of mental health. Furthermore, these findings support the integration of mental health screening into routine geriatric assessments, particularly those that include questions on sleep quality, stress burden, and daily functioning.

Given the aging population in many societies and the growing need for cost-effective, scalable solutions, the current model has clear implications for clinical and community settings. Targeting high-impact behavioral areas like sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress through non-pharmacological, evidence-based approaches could lead to widespread mental health gains with minimal resource burden. At the same time, the model reminds us not to overlook the broader systemic and socioeconomic conditions that shape vulnerability and resilience across the lifespan. A truly comprehensive strategy would engage both levels: addressing immediate symptoms while advocating for long-term structural change. Sleep disturbance held the strongest association, followed by psychosocial stress, while other factors such as age/Medicare access and education/income were comparatively less influential in the final model.

These findings reinforce the need to shift analytic and intervention priorities toward behavioral and emotional health determinants, rather than relying predominantly on static demographic attributes when evaluating mental health in older adults. While chronological age has traditionally been regarded as a central predictor of health outcomes, its direct influence may diminish in later life due to the effects of accumulated life experience, psychological resilience, and access to standardized services like Medicare. In contrast, behavioral patterns (e.g., sleep hygiene) and emotional stressors remain highly modifiable and directly relevant to older adults’ lived experiences, underscoring their value as intervention targets. Moreover, the influence of socioeconomic factors, such as education and income, points to the critical role of early-life investments in health literacy and equitable access to information. Together, these results support a public health approach that emphasizes psychosocial and behavioral interventions over fixed demographic categorization.

Sleep Disturbance

The dominance of sleep-related variables as the most powerful predictor in the model underscores their centrality to older adults' mental health. This finding aligns with a growing body of evidence highlighting the complex interplay between sleep, emotion regulation, and neurological health. Sleep disturbances such as insomnia, fragmented sleep, and early morning awakenings are not only prevalent among older adults but are also strongly correlated with increased risk of depression, anxiety, cognitive decline, and diminished quality of life (Baglioni et al., 2011; Walker, 2017).

Mechanistically, sleep problems can exacerbate psychological distress through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and heightened inflammatory responses—both of which have been implicated in the etiology of mood disorders (Irwin & Opp, 2017). Moreover, impaired sleep negatively impacts executive function, emotional reactivity, and resilience, compounding vulnerability to stress and reducing adaptive coping. These pathways are particularly concerning in older populations, who may already face age-related disruptions in sleep architecture, including decreased slow-wave sleep, reduced melatonin secretion, and increased nighttime awakenings (Mander et al., 2017; Ancoli-Israel, 2009).

Importantly, the relationship between sleep and mental health is likely bidirectional. Not only does poor sleep predict increased psychological distress, but mental health disorders themselves often disrupt sleep patterns, creating a self-reinforcing cycle (Harvey, 2011; Freeman et al., 2020). This bidirectionality underscores the importance of addressing sleep issues not merely as symptoms but as potential causal contributors to psychological distress.

It is also worth noting that the connection between sleep and physical health has long been established. Sleep deprivation is associated with a heightened risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and immune dysfunction (Cappuccio et al., 2010; Medic et al., 2017). Given that sleep plays such a crucial role in regulating physiological systems, it is perhaps unsurprising that its disruption would have similarly profound effects on mental functioning. Just as poor sleep can raise blood pressure or compromise immune response, it can impair mood regulation, increase irritability, and hinder emotional stability. This parallel supports the idea that sleep is a foundational determinant of holistic health—physical and mental alike.

Given the modifiable nature of sleep disturbances, this study adds to the evidence base supporting behavioral interventions—such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)—as promising strategies for improving sleep and, consequently, mental health in older adults. Previous trials have shown that CBT-I can produce lasting improvements in sleep quality and mood symptoms, often rivaling pharmacological approaches with fewer side effects (Irwin et al., 2013). The prominence of sleep in the current model lends further support to prioritizing sleep hygiene and behavioral sleep interventions as scalable, cost-effective components of geriatric mental health care.

Psychosocial Stress

Psychosocial stress emerged as the second most influential predictor of self-rated mental health, reinforcing its established role in mental and physical health outcomes. Although its beta coefficient was smaller than that of sleep disturbance, its significance remained both statistical and practical. Chronic stressors—such as caregiving responsibilities, financial insecurity, social isolation, and bereavement—can erode psychological resilience, particularly in later life when coping resources may be constrained (Charles & Piazza, 2009; Cohen et al., 2007).

Biologically, chronic stress activates the HPA axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels, impaired immune function, and increased vulnerability to physical health conditions like hypertension and diabetes, which in turn are linked to depressive symptoms and poorer mental health (Lupien et al., 2009). Psychologically, persistent stress undermines emotional regulation, increases rumination, and reduces perceived self-efficacy, all of which contribute to mental distress. In older adults, these effects may be compounded by reduced access to adaptive outlets, such as employment or physical mobility, and heightened exposure to loss and role transitions.

Stress also affects one’s ability to derive pleasure and meaning from life. When under prolonged stress, individuals often report diminished interest in hobbies, social withdrawal, and reduced appreciation for positive experiences (Pressman et al., 2009). Fatigue, irritability, and emotional blunting can lead to a disconnect from previously enjoyed activities. Conversely, individuals who are relatively stress-free often show greater openness, increased social engagement, and a more optimistic outlook—factors that are strongly correlated with higher levels of life satisfaction and self-rated mental health (Fredrickson, 2001). This highlights how reducing stress can enhance one's emotional availability and cognitive bandwidth to recognize joy, meaning, and positivity in life.

Notably, stress and sleep may interact synergistically, with stress interfering with sleep onset and maintenance, and poor sleep heightening stress sensitivity. This interdependence suggests that addressing either domain in isolation may be insufficient. Instead, integrated interventions—such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), or combined sleep-stress management programs—may yield greater benefits (Garland et al., 2014).

Education and Income

Although the Education/Income factor accounted for a smaller portion of variance in self-rated mental health compared to more immediate predictors, its significance lies in the broader systemic context it represents. Socioeconomic status (SES), reflected through educational attainment and income levels, is a well-documented structural determinant of health. Individuals with higher levels of education tend to possess stronger health literacy, enabling them to interpret medical information, make informed decisions, and engage in preventative behaviors that promote long-term well-being (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2010). Income complements this by facilitating access to material resources—such as safe housing, healthy food, and quality healthcare—that create protective buffers against stress and adversity (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008). These advantages are not just momentary but accumulate over the life course, reinforcing psychological resilience and overall health stability (Marmot, 2005).

For example, studies have shown that individuals with more education are significantly more likely to adhere to treatment protocols, maintain regular exercise, and avoid smoking—all of which are behaviors linked to improved health outcomes (Goldman & Smith, 2002). These same decision-making advantages likely extend to mental health as well. People with greater education may be more proactive in recognizing symptoms of psychological distress, seeking out therapy or social support, and implementing effective coping strategies. Thus, while education itself may not directly prevent mental health issues, it equips individuals with tools that can buffer stress and foster better emotional regulation and self-care.

The relatively smaller effect of the Education/Income factor in this model does not diminish its importance; rather, it highlights how distal social conditions shape mental health through more diffuse or indirect pathways. For example, socioeconomic disadvantage can influence mental health through chronic exposure to environmental stressors, limited access to mental health care, or increased risk of comorbid physical health conditions—all of which may be mediated by factors such as sleep disturbance or psychosocial stress. In this way, SES often serves as a foundation upon which other risk factors exert their influence. Moreover, the cross-sectional nature of the data may understate the cumulative and causal impact of SES on mental health, as it captures only a single point in time rather than long-term effects or lagged associations.

Ultimately, the significance of the Education/Income factor reinforces the understanding that mental health cannot be separated from broader socioeconomic realities. Even when its statistical contribution appears modest within a multivariate model, its presence as a consistent and meaningful predictor points to the enduring relevance of economic and educational equity. Addressing disparities in SES is therefore not only a matter of social justice but also a necessary condition for improving population mental health outcomes in a sustainable and comprehensive way.

Age and Medicare

Contrary to expectations, age and Medicare access did not significantly predict SRMH. This may reflect the homogenized age structure of the sample and the widespread availability of Medicare coverage in this population. These findings underscore a critical insight: subjective well-being in older adults is more strongly shaped by behavioral and psychosocial factors—such as sleep quality and stress—than by chronological age or health insurance status. This aligns with literature advocating for a shift in geriatric mental health strategies toward modifiable and experience-based predictors of wellness (Keyes, 2007; Diener & Chan, 2011)

The findings from this study therefore underscore the need for accessible, evidence-based strategies to mitigate psychosocial stress in aging populations. Community-level interventions aimed at enhancing social support, reducing loneliness, and improving access to mental health care may be particularly effective. Given the known efficacy of non-pharmacological stress reduction strategies, implementing these interventions within primary care or senior service contexts could help address a critical gap in geriatric mental health care.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of the analytical approach, including robust dimensionality reduction and rigorous model diagnostics, this study has some limitations that warrant critical reflection.

First, the reliance on self-reported survey data raises the risk of measurement bias, particularly due to social desirability or recall errors. Mental health outcomes, especially among older adults, may be subject to underreporting due to stigma or internalized ageist beliefs (Conner et al., 2010). This is not unique to the current study; a broad review by Van de Mortel (2008) underscores how socially desirable responding may attenuate or inflate relationships across a wide array of psychological constructs. In contexts where mental health remains stigmatized, respondents may intentionally or unconsciously minimize symptoms or exaggerate adaptive behaviors, leading to a distortion of observed associations. While some researchers suggest that using indirect questioning or anonymized digital surveys may help mitigate these biases (Kreuter et al., 2009), such strategies were not feasible in the current dataset. Future iterations of this work should consider mixed-methods designs that incorporate objective behavioral data or third-party assessments (e.g., clinician-rated instruments).

Second, while exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is a powerful tool for uncovering latent structures, it is inherently sample-specific. The factor structure derived from this dataset may not replicate in different populations, time periods, or cultural contexts. Fabrigar and Wegener (2011) emphasize that EFA solutions are sensitive to sample characteristics, variable selection, and even slight shifts in the distribution of responses. The choice of principal axis factoring and varimax rotation in this study further assumes orthogonality—an assumption that may be unrealistic in psychological research where constructs often overlap (Costello & Osborne, 2005). Other studies have addressed this concern by applying oblique rotations (e.g., promax), which allow for correlated factors, thereby improving construct interpretability and alignment with theoretical models (Osborne, 2015). Future studies should incorporate confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the stability and validity of the factor structure across diverse subgroups and data sources.

Together, these limitations do not negate the study’s findings but contextualize their interpretation. They reflect common methodological challenges in applied mental health research, particularly in aging populations, and underscore the need for continual refinement in study design, measurement, and analytic approaches.

Future Directions

One promising avenue for future research involves longitudinal modeling to investigate causal relationships between sleep, stress, and mental health. The cross-sectional nature of the present dataset limits causal inference and does not permit insight into temporal precedence or mediation. By tracking changes in sleep quality, stress levels, and self-rated mental health over time, researchers can disentangle directionality and identify lag effects, thereby improving causal inference (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Latent growth curve modeling or cross-lagged panel designs, for example, would enable researchers to model intra-individual change and explore whether changes in sleep predict downstream mental health deterioration or whether mental health fluctuations precipitate sleep disruption (Selig & Little, 2012). These approaches offer a substantial advantage over traditional cross-sectional analyses by accounting for both stability and change, and by clarifying the temporal order of variables—essential for intervention design and clinical prediction.

Another important extension would involve integrating biological or behavioral health data to supplement self-reported findings. For example, actigraphy can provide objective, continuous measurement of sleep duration and efficiency, while cortisol awakening response and diurnal slope offer biomarkers of physiological stress regulation (Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005; Mezick et al., 2009). These methods are particularly useful in identifying psychophysiological pathways through which stress and sleep interact to affect well-being. The addition of heart rate variability (HRV), a well-established indicator of autonomic nervous system regulation, may further elucidate mechanisms linking emotional regulation to sleep quality and mental health (Thayer et al., 2012). Incorporating ecological momentary assessment (EMA) could also capture dynamic fluctuations in mood and behavior in real-time contexts, providing more granular data than retrospective surveys can offer (Shiffman et al., 2008). Combining these techniques with traditional surveys would enhance data validity and help triangulate mechanisms driving mental health variation.

Additionally, future research should explore the role of social connectedness and digital engagement as potential moderators in the relationship between stress, sleep, and mental health. Social isolation is a known risk factor for depression and anxiety in older adults, yet growing technology use among this population presents an opportunity for intervention. Digital health technologies—such as telepsychiatry, mobile sleep coaching, and online support groups—may buffer the psychological impact of isolation, especially for individuals with limited physical mobility or access to in-person care (Chopik, 2016; Czaja et al., 2018). Moderated mediation analysis could help evaluate whether the protective effect of digital engagement operates via reduced stress or improved sleep quality. Furthermore, research might explore how digital literacy moderates these benefits, given that disparities in access and usability can influence outcomes in older populations (Baker et al., 2022).

Lastly, future studies should incorporate stratified sampling and subgroup analysis to explore heterogeneity of effects across racial, gender, and socioeconomic groups. Cultural differences in stress appraisal, help-seeking, and sleep practices may shape how latent factors influence mental health (Hall et al., 2015). Intersectional analysis would enhance equity in public health interventions by ensuring findings are applicable across diverse older adult populations. This includes not only demographic subgroup comparisons but also analyses of structural determinants such as geographic region, access to care, and language barriers, which may influence both exposure and resilience to stressors affecting sleep and mental health.

Importance and Implications

This study offers critical insight into the modifiable drivers of mental health among aging adults. By identifying sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress as key predictors of poor self-rated mental health, this research highlights essential, yet often overlooked, domains of intervention. The implications extend far beyond the individual level—they point toward broad public health and societal imperatives that intersect healthcare delivery, educational outreach, policy design, and community wellness.

One of the most pressing takeaways is the need for greater public education on the importance of sleep hygiene as a fundamental pillar of mental health. Despite mounting evidence of the link between inadequate sleep and increased risk for depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline (Walker, 2017; Freeman et al., 2020), sleep health remains underemphasized in both clinical practice and public health messaging. As a society, we have not adequately normalized sleep prioritization as a legitimate health behavior, despite its demonstrable consequences. Public awareness campaigns akin to those for nutrition, exercise, and smoking cessation are urgently needed to close this gap.

Furthermore, clinical training programs should incorporate sleep assessment and intervention techniques into core curricula for medical professionals, psychologists, and social workers. Currently, most primary care physicians receive less than two hours of formal sleep education throughout their training (Mindell & Bartle, 2017), which undermines their capacity to detect and treat one of the most prevalent and reversible mental health risk factors. Increased institutional support for screening and treating insomnia and chronic stress, including cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), is warranted given their cost-effectiveness and long-term efficacy (Irwin et al., 2013; Ong & Sholtes, 2010).

From a governmental and policy perspective, this study also calls for a reorientation of resources toward upstream, preventative interventions that target behavioral health. Agencies like the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Administration for Community Living (ACL), and state-level public health departments should expand funding for community-based programs that address sleep, stress, and mental well-being in older populations. Programs could include mobile mental health units, and digital mental health platforms that reach rural or underserved areas.

Incorporating behavioral health initiatives into existing infrastructures—such as senior centers, telehealth services, and Medicare wellness visits—represents a scalable and equitable strategy. Moreover, sleep and stress interventions could be integrated with existing chronic disease management efforts (e.g., for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis), recognizing the bi-directional interplay between psychological and physiological conditions (Zisberg et al., 2010).

Another critical implication of the findings is the need to re-examine the role of socioeconomic determinants in the provision of mental health support. The significant effects of income and education in the regression model suggest that these factors remain relevant contributors to mental well-being, even when behavioral and emotional factors are considered. This reinforces the value of behavioral and cognitive-based interventions, which may offer broader scalability and lower implementation costs than large-scale structural reforms. However, to be truly effective, such interventions must be tailored to account for disparities in access, health literacy, and digital fluency, which can create barriers to engagement even when services are theoretically available (Baker et al., 2022). Designing interventions that are adaptable, inclusive, and accessible is therefore essential to closing gaps in care delivery and improving outcomes across diverse aging populations.

Importantly, findings from this study align with the broader call for an age-friendly healthcare system—one that is attuned not only to physical health markers but also to social and emotional well-being. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Decade of Healthy Ageing initiative underscores the urgency of shifting from reactive medical models to proactive, person-centered care approaches (WHO, 2020). This study contributes empirical weight to that initiative by empirically demonstrating the outsized influence of manageable health behaviors, such as sleep and stress regulation, on subjective well-being.

In sum, this research strengthens the case for immediate and multi-sectoral investment in behavioral mental health services for older adults. It offers a roadmap for clinical practitioners, public health officials, and policymakers alike to act on evidence-based priorities that could drastically improve quality of life for millions. By centering interventions around modifiable behaviors rather than immutable traits, it fosters a more empowering and equitable vision of healthy aging.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the growing body of research exploring self-rated mental health among older adults by identifying and quantifying key latent factors—such as sleep disturbance, psychosocial stress, and socioeconomic status—that, along with additional contributing dimensions, collectively explained 52% of the variance in psychological well-being. Through the application of exploratory factor analysis and regression modeling, we found that behavioral and emotional health determinants carried greater predictive weight than static demographic indicators. Sleep disturbance emerged as the strongest predictor of self-rated mental health, followed by psychosocial stress and, to a lesser but still significant degree, education and income. These findings underscore the primacy of modifiable, experiential variables in shaping late-life mental health outcomes.

Importantly, the implications of these findings extend beyond theoretical insight and point toward concrete, actionable priorities for intervention. The fact that sleep quality and psychosocial stress emerged as central contributors highlights the value of behavioral health programs that are both preventative and responsive. Low-cost, scalable interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and social engagement initiatives could prove particularly beneficial. These approaches not only reduce psychological symptoms but also improve resilience, quality of life, and health outcomes more broadly.

Moreover, the results emphasize the value of screening older adults for sleep and stress issues as part of routine mental health evaluations. Incorporating validated sleep and stress assessments into primary care visits or community health screenings may help identify at-risk individuals early and offer opportunities for targeted intervention. Given the bidirectional nature of both sleep and stress with mental health, addressing these symptoms may serve as a gateway to broader mental and physical health improvements.

While the Education/Income factor explained a smaller share of variance, its presence as a statistically significant predictor reinforces the enduring influence of socioeconomic context. Higher education and income levels equip individuals with health literacy, decision-making capacity, and access to care—all of which can shape mental health trajectories across the life course. Addressing mental health disparities in aging populations therefore requires not only behavioral interventions but also systemic investments in education, equity, and resource access.

That said, this study is not without limitations. Its cross-sectional design restricts the ability to draw causal conclusions, and the findings represent a snapshot rather than a dynamic portrayal of aging. Longitudinal research would offer a deeper understanding of how mental health evolves in response to changes in sleep, stress, and SES over time. Additionally, although this study captured key latent constructs, there may be other influential variables—such as household structure, caregiving responsibilities, perceived social support, environmental stressors, and community-level resources—that were not included but could further refine predictive models. Incorporating these elements in future analyses may enhance explanatory power and provide a more comprehensive understanding of mental health trajectories in aging populations.

In sum, this study sheds light on the psychosocial architecture of mental health in older adulthood. The identification of modifiable behavioral factors as dominant predictors offers hope and direction for improving the well-being of older populations. At a time when aging demographics are expanding globally, these insights carry significant public health implications. Mental health promotion for older adults must go beyond passive care and embrace proactive, preventive, and contextually informed strategies. By intervening on sleep and stress while addressing broader structural inequities, practitioners and policymakers can better support the mental health and dignity of aging individuals.

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A

| |

|

|

| Variable Name |

Description |

Associated Factor |

| Q1 |

Self-rated physical health |

Other/Mixed |

| Q2 |

Self-rated mental health |

Dependent Variable (SRMH) |

| Q7 |

Employment status |

Psychosocial Stress |

| Q13A |

Trouble falling asleep (nights per week) |

Sleep Disturbance |

| Q14_1 |

Wakes up during the night (nights per week) |

Sleep Disturbance |

| Q14_6 |

Wakes up too early (nights per week) |

Sleep Disturbance |

| Q14_8 |

Feels well rested (nights per week) |

Sleep Disturbance |

| Q15 |

Sleep quality rating |

Sleep Disturbance |

| Q34 |

Discussed sleep problems with a doctor |

Healthcare Engagement |

| Q41_3 |

Doctor recommended sleep study |

Healthcare Engagement |

| Q46 |

Doctor recommended sleep aid |

Healthcare Engagement |

| PPEDUC |

Highest education level |

Education/Income |

| PPETHM |

Race/Ethnicity |

Demographic/Household |

| PPGENDER |

Gender |

Demographic/Household |

| PPHHHEAD |

Head of household status |

Demographic/Household |

| PPINCIMP |

Household income level |

Education/Income |

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Bartels, S. J., & Naslund, J. A. (2002). Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care. Psychiatric Services, 53(11), 1419–1431. [CrossRef]

- Gellis, Z. D., & Bruce, M. L. (2010). Problem-solving therapy for subthreshold depression in home healthcare patients with cardiovascular disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(6), 464–474. [CrossRef]

- Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Schnittker, J., & Bacak, V. (2014). The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLOS ONE, 9(1), e84933. [CrossRef]

- Minkel, J. D., Banks, S., Htaik, O., Moreta, M. C., Jones, C. W., McGlinchey, E. L., Simpson, N. S., & Dinges, D. F. (2012). Sleep deprivation and stressors: Evidence for elevated negative affect in response to mild stressors when sleep deprived. Emotion, 12(5), 1015–1020. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D., Steinberg, J., & Patel, P. (2018). Insomnia in the elderly: A review. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(6), 1017–1024. [CrossRef]

- Foley, D. J., Monjan, A. A., Brown, S. L., Simonsick, E. M., Wallace, R. B., & Blazer, D. G. (1995). Sleep complaints among elderly persons: An epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep, 18(6), 425–432. [CrossRef]

- Garland, E. L., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., & Wichers, M. (2014). Mindfulness training promotes upward spirals of positive affect and cognition: Multilevel and autoregressive latent trajectory modeling analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 15. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J. F., Zitting, K. M., & Chinoy, E. D. (2015). Aging and circadian rhythms. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 10(4), 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M. R., Cole, J. C., & Nicassio, P. M. (2013). Comparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in older adults. Sleep, 29(11), 1445–1454. [CrossRef]

- Espie, C. A., Kyle, S. D., Williams, C., Ong, J. C., Douglas, N. J., Hames, P., & Brown, J. S. L. (2012). A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep, 35(6), 769–781. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2010). Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics, 29(1), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Acock, A. C. (2016). A gentle introduction to Stata (5th ed.). Stata Press. Available online: https://www.stata.com/bookstore/gentle-introduction-to-stata/.

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M. S. (1954). A note on the multiplying factors for various chi square approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 16(2), 296–298. [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Baglioni, C., Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U., & Riemann, D. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. P. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

- Irwin, M. R., & Opp, M. R. (2017). Sleep health: Reciprocal regulation of sleep and innate immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 129–155. [CrossRef]

- Mander, B. A., Winer, J. R., Jagust, W. J., & Walker, M. P. (2017). Sleep: A novel mechanistic pathway, biomarker, and treatment target in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease? Trends in Neurosciences, 40(3), 210–221. [CrossRef]

- Ancoli-Israel, S. (2009). Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Medicine, 10(Suppl 1), S7–S11. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A. G. (2011). Sleep and circadian rhythms in bipolar disorder: Seeking synchrony, harmony, and regulation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1243–1250. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D., Sheaves, B., Waite, F., Harvey, A. G., & Harrison, P. J. (2020). Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 628–637. [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, F. P., Cooper, D., D'Elia, L., Strazzullo, P., & Miller, M. A. (2011). Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. European Heart Journal, 32(12), 1484–1492. [CrossRef]

- Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. H. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Charles, S. T., & Piazza, J. R. (2009). Age differences in affective well-being: Context matters. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(5), 711–724. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. JAMA, 298(14), 1685–1687. [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445. [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S. D., Matthews, K. A., Cohen, S., Martire, L. M., Scheier, M., Baum, A., & Schulz, R. (2009). Association of enjoyable leisure activities with psychological and physical well-being. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(7), 725–732. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Garland, S. N., Carlson, L. E., Stephens, A. J., Antle, M. C., Samuels, C., & Campbell, T. S. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia comorbid with cancer: A randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(5), 449–457. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2010). Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics, 29(1), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Adler, N. E., & Rehkopf, D. H. (2008). U.S. disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 235–252. [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet, 365(9464), 1099–1104. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D. P., & Smith, J. P. (2002). Can patient self-management help explain the SES health gradient? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(16), 10929–10934. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J. W. (2015). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Stress in AmericaTM 2020: A national mental health crisis. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report.

- Grandner, M. A. (2019). Sleep, health, and society. Sleep Health, 5(5), 383–384. [CrossRef]

- Gulia, K. K., & Kumar, V. M. (2018). Sleep disorders in the elderly: A growing challenge. Psychogeriatrics, 18(3), 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Hu, P., & Treiman, D. J. (2019). Life satisfaction, social support, and mental health of older adults in China. Aging & Mental Health, 23(4), 498–505.

- Luyster, F. S., Strollo, P. J., Zee, P. C., & Walsh, J. K. (2015). Sleep: A health imperative. Sleep, 35(6), 727–734. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (2004). Protection and damage from acute and chronic stress: Allostasis and allostatic overload and relevance to the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1032(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wolkove, N., Elkholy, O., Baltzan, M., & Palayew, M. (2007). Sleep and aging: 1. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 176(9), 1299–1304. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Wing, Y. K., & Li, S. X. (2019). Sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms in the elderly: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 243–248. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D. M., Neupert, S. D., Banks, S. R., & Serido, J. (2017). Do daily stress processes account for socioeconomic health disparities? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(Special Issue 2), S34–S39. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2020). Behavioral health integration services.

- Hudson, C. G. (2005). Socioeconomic status and mental illness: Tests of the social causation and selection hypotheses. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(1), 3–18. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation's health. The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2021). Behavioral health equity report 2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/behavioral-health-equity-report-2021.

- Xue, B., Coady, M., Wilson, A., & Brown, L. M. (2021). Health behaviors as mediators between socioeconomic status and depression in older adults: A longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 25(2), 261–268. [CrossRef]

- Conner, K. O., Copeland, V. C., Grote, N. K., Koeske, G., Rosen, D., Reynolds III, C. F., & Brown, C. (2010). Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: The impact of stigma and race. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(6), 531–543. [CrossRef]

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, F., Presser, S., & Tourangeau, R. (2009). Social desirability bias in CATI, IVR, and web surveys: The effects of mode and question sensitivity. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5), 847–865. [CrossRef]

- Van de Mortel, T. F. (2008). Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(4), 40–48.

- Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23–44. [CrossRef]

- Selig, J. P., & Little, T. D. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In B. Laursen, T. D. Little, & N. A. Card (Eds.), Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 265–278). The Guilford Press.

- Baker, D. A., DeRosier, M. E., Ketchum, L., & Siuta, J. (2022). Digital health equity and aging: Addressing disparities in digital literacy to promote healthy aging. Innovation in Aging, 6(1), igab048. [CrossRef]

- Chopik, W. J. (2016). The benefits of social technology use among older adults are mediated by reduced loneliness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(9), 551–556. [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S. J., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., & Rogers, W. A. (2019). Designing for older adults: Principles and creative human factors approaches (3rd ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Kudielka, B. M., & Kirschbaum, C. (2005). Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: A review. Biological Psychology, 69(1), 113–132. [CrossRef]

- Mezick, E. J., Hall, M., & Matthews, K. A. (2009). Sleep duration and ambulatory blood pressure in black and white adolescents. Hypertension, 54(3), 755–761. [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F., Åhs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers III, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(2), 747–756. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D., Sheaves, B., Waite, F., Harvey, A. G., & Harrison, P. J. (2020). Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 628–637. [CrossRef]

- Hall, B. J., Bonanno, G. A., Bolton, P. A., & Bass, J. K. (2015). A mixed-methods study of lay conceptions of mental illness in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Mental Health, 2, e4. [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (n.d.). Welcome to Medicare preventive visit. Available online: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/welcome-to-medicare-preventive-visit.

- Irwin, M. R., Olmstead, R., Carrillo, C., Sadeghi, N., Breen, E. C., Witarama, T., ... & Carroll, J. E. (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. Tai Chi for late-life insomnia and inflammatory risk: A randomized controlled comparative efficacy trial. Sleep, 37(9), 1543–1552. [CrossRef]

- Mindell, J. A., & Bartle, A. (2017). Sleep education in medical school: A national survey of U.S. medical schools. Sleep Health, 3(6), 452–457. [CrossRef]

- Ong, J. C., & Sholtes, D. (2010). A mindfulness-based approach to the treatment of insomnia. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(11), 1175–1184. [CrossRef]

- Zisberg, A., Gur-Yaish, N., & Shochat, T. (2010). Contribution of routine to sleep quality in community elderly. Sleep, 33(4), 509–514. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. A., DeRosier, M. E., Ketchum, L., & Siuta, J. (2022). Digital health equity and aging: Addressing disparities in digital literacy to promote healthy aging. Innovation in Aging, 6(1), igab048. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Decade of healthy ageing: Baseline report. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).