1. Introduction

The assembly of wind turbine gearboxes involves numerous complex mechanical components, each of which must be carefully installed to ensure the optimal performance of the turbines [

1,

2]. The gearbox converts the low-speed, high-torque rotation from the turbine’s rotor into high-speed, low-torque rotation, which is essential for electricity generation [

3,

4,

5]. Errors in the assembly process, such as torque misapplication, part misalignment, and violation of precedence constraints, can lead to significant degradation of performance, increased downtime, and even mechanical failure [

6]. These errors not only increase maintenance costs but also impact the reliability and lifespan of wind turbines [

7]. Previous research has largely focused on minimizing the assembly time of gearbox assembly, with less attention paid to error reduction [

8]. However, errors during the assembly process can have far-reaching consequences, especially in complex systems like wind turbine gearboxes, where component interdependencies and mechanical precision are critical [

9]. Given the high cost of failure and rework, there is a growing need for optimization methods that focus on reducing assembly errors.

Assembly errors can be reduced by training intelligent systems that dynamically adjust assembly operations by learning from past errors and improving performance. By continuously optimizing decision-making based on feedback, algorithms can reduce error rates, enhance precision, and improve overall efficiency in automated assembly lines. This approach enables systems to learn and adapt over time, minimizing human intervention and reducing costly assembly errors [

10]. Assembly error reduction is a critical focus in dynamic environments, where real-time adjustments can significantly improve process reliability. An adaptive real-time resource allocation approach was developed for dynamically adjusting resources based on environmental conditions was developed [

11]. Their method optimizes resource allocation through real-time feedback, reducing assembly errors by responding immediately to changes in the production environment [

12]. Similarly, [

13] developed an optimization technique using adaptive particle swarm optimization (PSO), which can efficiently handle real-time adjustments during the assembly process. This adaptive PSO improves process precision by continuously optimizing operational parameters based on real-time data, minimizing errors in dynamic environments [

14]. To further enhance error reduction, hybrid optimization algorithms have been explored. An algorithm was introduced for global optimization, which can track and adjust assembly parameters in real-time, reducing errors through adaptive learning [

15]. Another method highlighted the importance of PSO in tracking and optimizing dynamic systems, demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing errors during the assembly process [

16]. Additionally, a method applied a bacterial foraging optimization technique to dynamic environments, ensuring that assembly operations can adapt to changes in real-time, further minimizing error rates [

17]. These adaptive optimization strategies contribute significantly to reducing assembly errors in complex and dynamic production environments.

Incorporating recent advancements in hybrid meta-heuristic algorithms is essential for enhancing the effectiveness of assembly optimization processes. [

18], introduced a hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) approach that integrates adaptive learning strategies to address the inherent limitations of standard PSO, such as premature convergence and suboptimal exploitation capabilities. This method demonstrated improved performance in solving complex optimization problems, making it a valuable reference for assembly sequence optimization. Similarly, [

19] proposed a Genetic Algorithm (GA)-based alignment correction technique tailored for flexible and transparent field-effect transistors. Their study focused on the uniaxial alignment of nanowires using an off-center spin-coating method, achieving significant improvements in device performance. This approach offers valuable insights into alignment correction methodologies applicable to various assembly processes. Furthermore, [

20] conducted a cumulative review of major advances in PSO from 2018 to the Present. Their findings highlighted the efficacy of hybrid algorithms in addressing complex optimization challenges within industrial contexts, underscoring the potential benefits of adopting such approaches in assembly optimization tasks.

This study leverages simulation-based results to evaluate the performance of the PSBFO model. While real-world validation in an industrial setting of wind turbine gearbox assembly is essential for confirming the model’s practical applicability, it was not feasible within the timeframe of research. Future work will focus on real-world case studies to validate these findings. The goal of this paper is to minimize errors in the assembly of the wind turbine gearbox by using a hybrid optimization approach of particle swarm-bacteria foraging optimization(PSBFO) that combines the strengths of particle swarm optimization(PSO) and bacteria foraging optimization(BFO. This approach optimizes the sequence of assembly tasks while taking precedence constraints and error likelihoods into account. By focusing on error reduction, this work aims to improve the overall reliability of wind turbine gearboxes, ensuring longer operational life and reducing the need for costly repairs and maintenance. This study introduces several novel contributions to the field of error reduction in the assembly of complex mechanical systems like wind turbine gearboxes. The first novelty lies in the integration of task sequencing optimization based on precedence constraints and error likelihoods. The second novelty involves the evaluation of PSBFO for error reduction, which has not been extensively applied in this context. Finally, the third novelty is the development of a comprehensive framework for error reduction in complex mechanical assemblies, specifically focusing on the unique challenges posed by wind turbine gearboxes.

This research is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, highlighting past advancements and gaps in assembly error minimization and sequence optimization for complex mechanical systems like wind turbine gearboxes.

Section 3 describes the materials and methods used, detailing the error model, precedence constraints, and task-specific requirements essential to the assembly process. It also presents the proposed hybrid optimization approach, including the integration of parallel assembly sequence planning (PASP) with the particle swarm-bacteria foraging optimization (PSBFO) algorithm, designed to minimize assembly errors effectively.

Section 4 discusses the simulation results and analyzes the error reduction performance compared to traditional methods. It also provides insights on error distribution across gearbox components and assesses the robustness of the PSBFO algorithm. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the study, summarizing the research findings and suggesting future research directions for error minimization in complex assemblies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wind Turbine Gearbox Assembly and the Role of Error Minimization

Errors during the assembly process of these component misalignments, incorrect torque application, and precedence violations can significantly impact the turbine’s performance and longevity [

21]. Gearbox assembly has long been an area of focus in both research and industry, to improve performance, reduce downtime, and minimize operational risks [

22]. While previous studies have concentrated on reducing assembly time and costs [

7,

23,

24], error minimization has recently gained attention as a critical factor in enhancing the reliability and safety of gearboxes [

25]. This shift is driven by the high costs associated with mechanical failures in wind turbines, which can result in extended downtime and expensive repairs [

26].

2.2. Parallel Assembly Sequence Planning (PASP) in Mechanical Systems

PASP is particularly important in complex mechanical systems, such as wind turbine gearboxes, where components like planetary gears, high-speed shafts, and sun gears have strong interdependencies [

27]. Studies on PASP have shown that parallelizing assembly tasks can significantly reduce overall assembly time, particularly in scenarios where multiple subsystems can be assembled simultaneously without violating task dependencies [

28]. However, the use of PASP in the context of error minimization has been less explored. Most research on PASP has focused on optimizing task scheduling to minimize time and costs, but recent work has begun to investigate its potential to reduce assembly errors by optimizing the order of operations and enforcing precedence constraints [

29].

2.3. Optimization Techniques for Assembly Processes

Traditional methods such as genetic algorithms (GA) and ant colony optimization (ACO) have been extensively used to optimize assembly sequence planning, focusing primarily on reducing time and costs [

30,

31]. These methods, while effective in improving operational efficiency, often do not account for the specific sources of error that can arise in complex assemblies, such as component misalignment or task dependency violations [

9]. In recent years, hybrid optimization techniques have gained popularity due to their ability to balance global exploration and local refinement in complex problems. One such technique is PSO, which mimics the social behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling to explore multiple solutions simultaneously [

32].

BFO is inspired by the foraging behavior of bacteria and is particularly effective in optimizing smaller, localized solutions by fine-tuning sequences to reduce specific types of errors [

15].

2.4. Error Minimization in Assembly Processes

Errors during the assembly of wind turbine gearboxes, for instance, can lead to increased wear, premature failures, and reduced operational efficiency [

33]. Researchers have identified common sources of assembly errors, such as misalignment, incorrect torque application, and failure to adhere to task dependencies [

34]. Traditional assembly methods often overlook these error sources, focusing instead on optimizing for cost or time. However, studies show that even small assembly errors can have significant long-term impacts on the performance and lifespan of wind turbines [

35]. The integration of error minimization strategies into assembly sequence planning is thus becoming a critical area of research. In particular, hybrid optimization techniques such as PSBFO, which can address both global optimization and local error refinement, are gaining traction as a powerful solution to reduce errors in complex assemblies [

36].

2.5. The Role of PSBFO in Error Minimization and Decision Support for Production Systems

While PSO enables the exploration of a wide range of task sequences to identify potential solutions, BFO refines these sequences by minimizing errors related to specific tasks, such as torque misapplication or component misalignment [

37]. Research has shown that PSBFO outperforms traditional optimization methods in reducing errors in complex mechanical systems. It was demonstrated that PSBFO could achieve significant improvements in assembly sequence planning by minimizing both time and error simultaneously [

38]. Similarly, it was shown that PSBFO is highly effective in reducing task-specific errors by optimizing the order of operations and enforcing precedence constraints [

39].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Error Model and Precedence Constraints

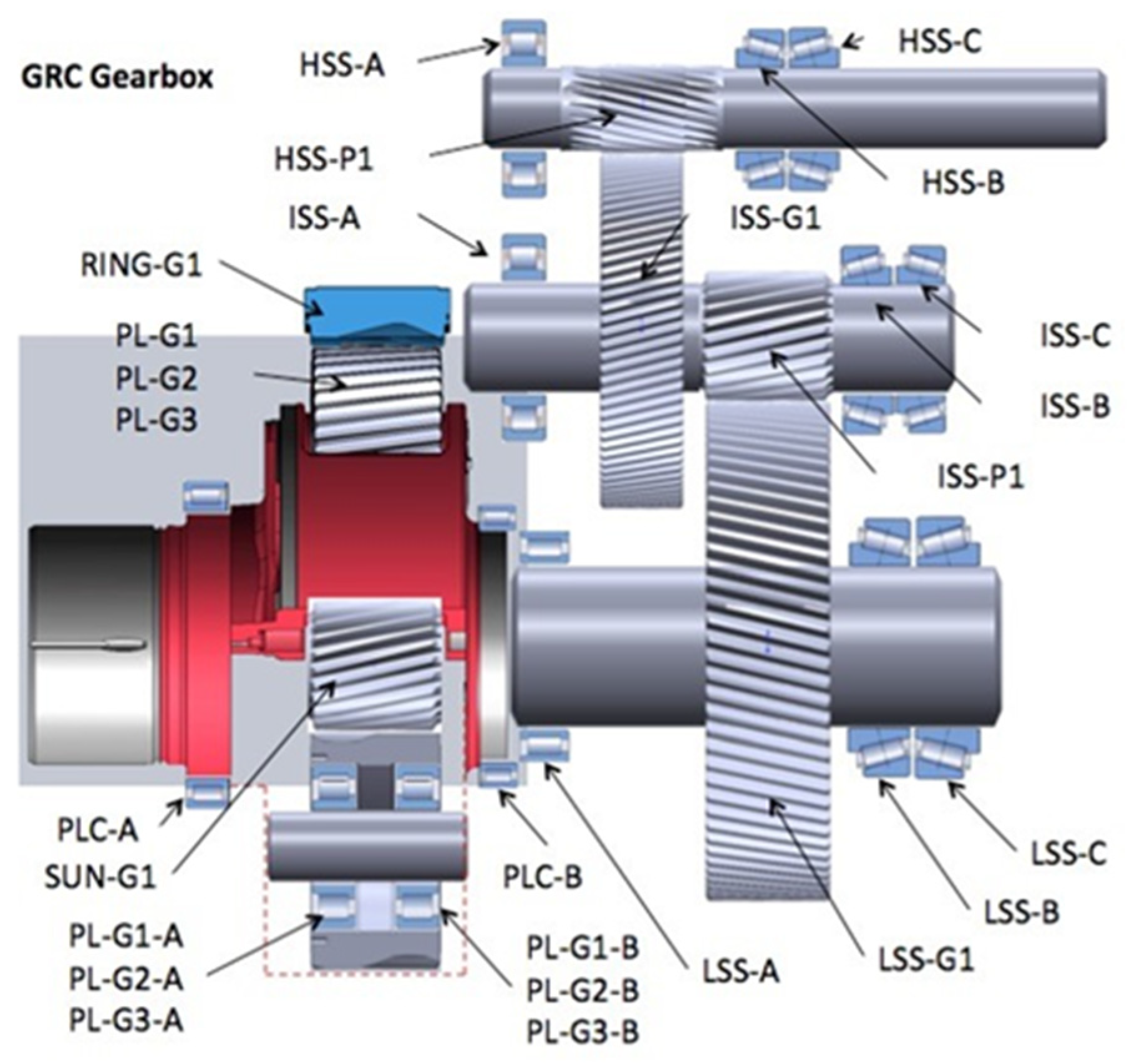

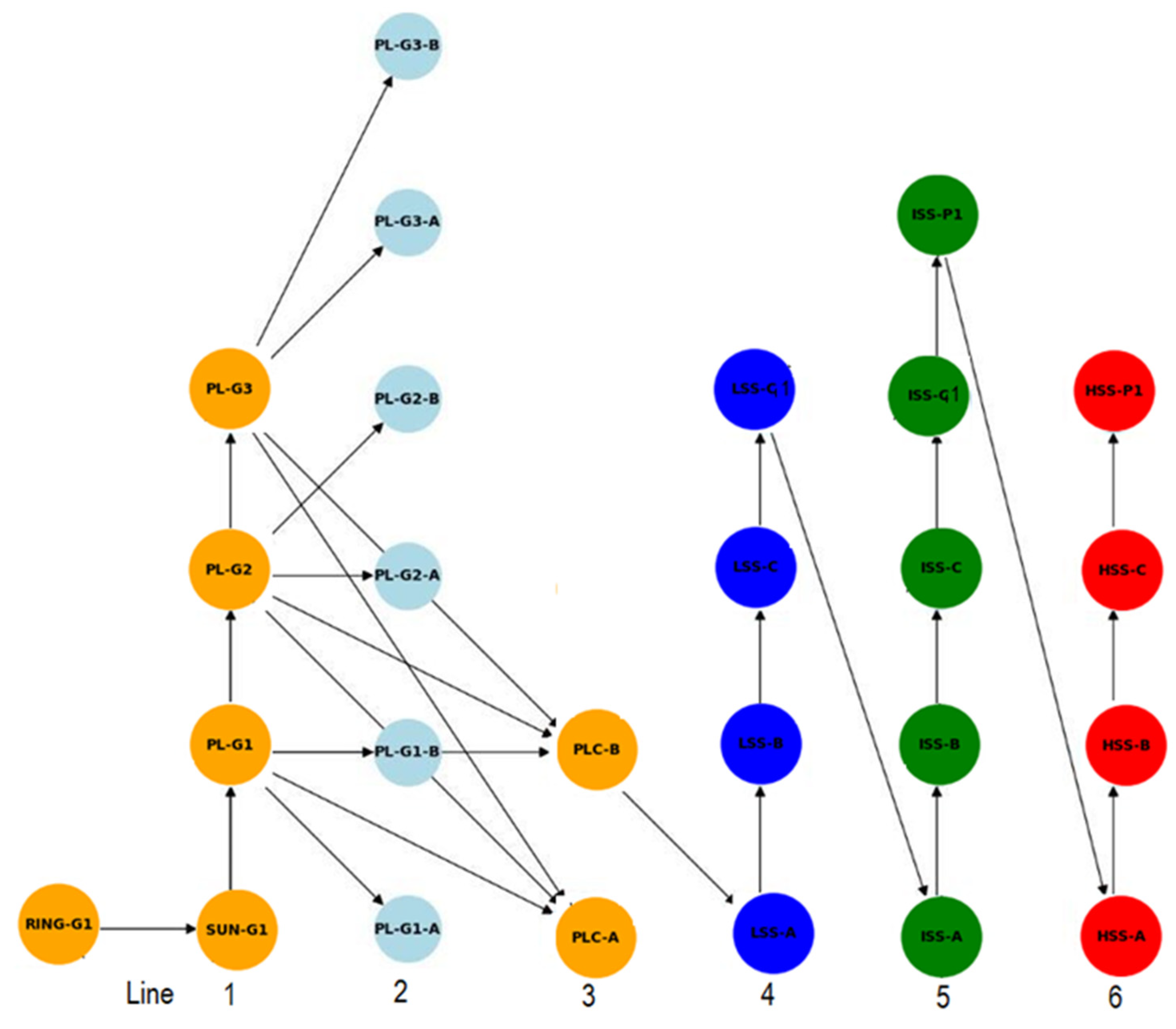

The assembly of a generic 10MW wind turbine gearbox involves 26 critical distinct parts, each with specific precedence constraints that must be adhered to as shown in

Figure 1. These constraints dictate the correct order of operations to ensure that all components are properly assembled, avoiding potential errors of misalignment, incorrect torque application and failure to account for dependencies between components. The ring gear (RING-G1) must be assembled before the sun gear (SUN-G1), which in turn must be installed before the planetary gears (PL-G1, PL-G2, PL-G3). The assembly of the low-speed shaft (LSS) and its components (LSS-A, LSS-B, LSS-C) depends on the completion of the planetary gear system and intermediate-speed shaft components. The high-speed shaft (HSS-A, HSS-B, HSS-C) is assembled later in the process after key components like planetary gears and shafts are installed. The 26 components involved in the gearbox assembly are shown in

Figure 1 below.

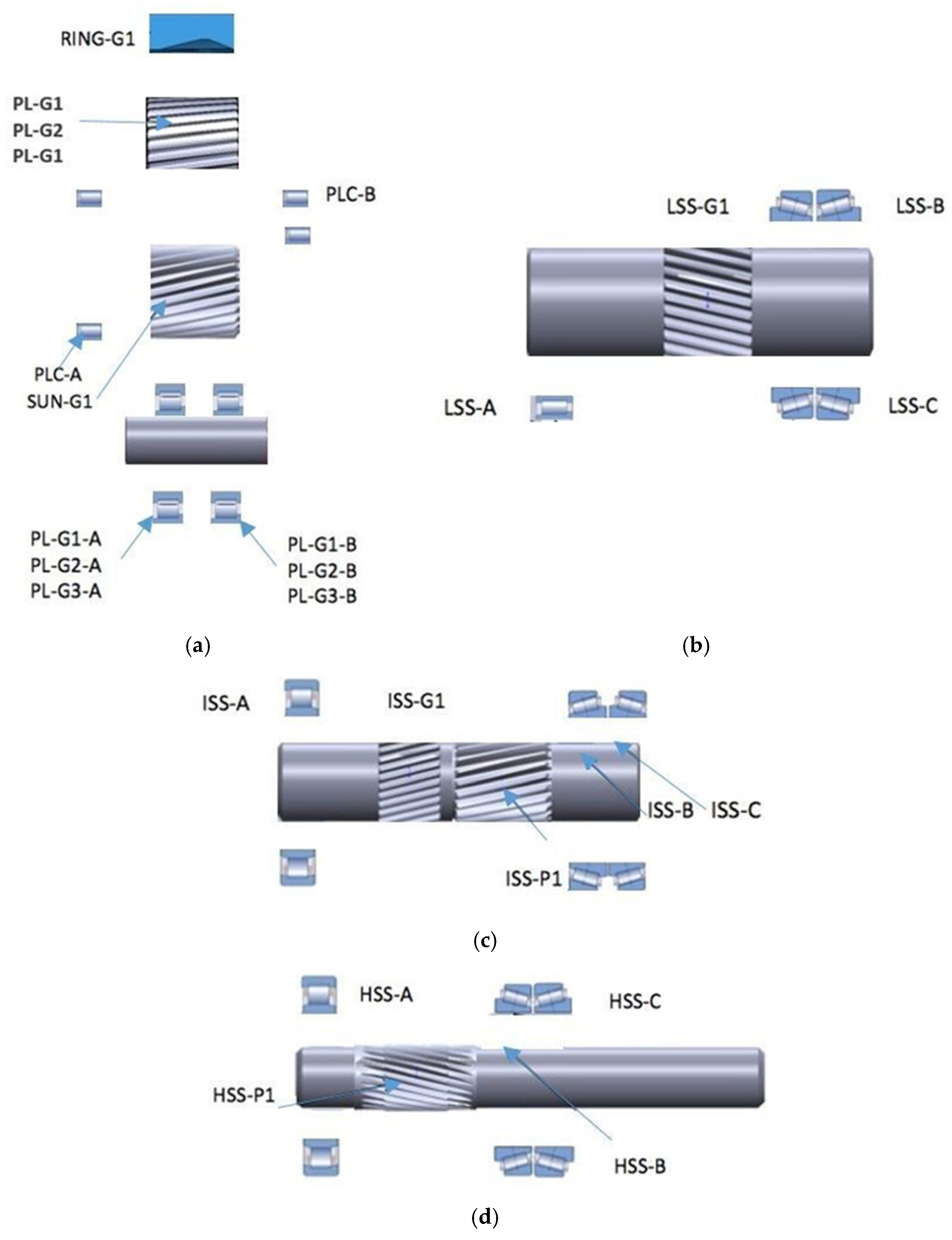

The precedence constraints define the order in which each component must be assembled, the sub-assemblies are as shown in

Figure 2. The sub-assemblies are subsequently incorporated into the main gearbox housing, where all connections are secured, and the gear alignment is carefully ensured as shown in

Figure 1.

To model errors in this complex assembly process, each task (component) is assigned an error likelihood based on historical data and expert judgment. These errors can impact the performance, reliability, and longevity of the gearbox. In this study, the assembly errors are tracked and minimized by considering two main factors:

Task-specific errors: Each task or component in the assembly has an inherent likelihood of error. For example, components that require precise alignment or torque, like the low-speed shaft or planetary gears, have a higher likelihood of errors during their assembly.

Precedence constraint violations: The assembly of the gearbox components follows a specific order or precedence constraints. Components must be assembled before others to ensure proper functioning.

Additionally, penalties are applied when precedence constraints are violated. The total error

for a given assembly sequence is calculated as:

Where errors include;

ETS,i: Task-specific error for each component i, for misalignment and torque misapplication.

Operator errors for task i.

: Error from tool or equipment variability for task i.

Error due to environmental influences (e.g., temperature, humidity) for task i.

Error due to component quality variations for task i.

: Penalty for violating precedence constraints for task j.

Where Weighting factors include;

: Weight for task-specific errors.

: Weight for operator errors.

: Weight for tool/equipment variability errors.

: Weight for environmental errors.

: Weight for component quality errors.

: Weight for precedence violations.

For error minimization, we introduce a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model to formally define the gearbox assembly error minimization problem. The MILP formulation ensures optimal allocation of assembly configurations while minimizing misalignment and component errors. MILP formulation is presented as:

Subject to:

Constraint 1: Assembly sequence constraints

Constraint 2: Tolerance-based error minimization constraints

Constraint 3: Component compatibility constraints

Constraint 4: Feasibility constraints ensuring valid assembly configurations

3.2. Error Modeling, Weighting, and Optimization Strategies

This method is supported by well-established practices in multi-criteria decision-making, where expert input and historical data are crucial in determining the relative importance of each factor [

41]. Such expert judgment is commonly used in complex decision-making models to capture domain-specific insights [

42]. We analyzed historical data from previous assembly processes to identify error frequencies and their effects on performance, a practice validated in prior studies [

43]. We then normalized and calibrated the weights to ensure consistency and accuracy in the model. This approach aligns with best optimization practices, where normalization and iterative calibration are used to adjust weights until model results align with empirical observations [

44]. The final weight assignment follows a weighted sum approach, commonly applied in error minimization studies to reflect the relative significance of each error source [

45]. This study uses simulated data to demonstrate the model’s potential, and real-world validation is planned for subsequent phases of the research. These methodologies collectively ensure that the assigned weights accurately represent the model’s objective to minimize errors in assembly processes and enhance reliability. Based on this method, the following weights were used in the computation for formula (1):

=0.4 (Task-specific errors, the highest due to its critical impact on alignment and torque requirements). Affect the performance and severe impact on functionality, leading to costly rework.

=0.2 (Operator errors, as human error is significant in manual assembly tasks). Less common, but still impacts the overall quality.

=0.15 (Tool/equipment variability, affecting precision but to a lesser degree than task-specific errors)

=0.1 (Environmental errors, impacting the process indirectly). Minor effect on the process overall.

=0.1 (Component quality errors, moderately significant in affecting the final assembly)

=0.05 (Precedence violation penalty, as a deterrent to ensure correct assembly sequence)

Error likelihoods represent the probability of an error occurring due to component task-specific errors. Appendix 1 tabulates the component error likelihoods and dependencies. Components with higher complexity and critical dependencies are assigned higher likelihoods. To mathematically formulate these dependencies and error likelihoods, we define:

Error likelihood function: Let Ei,j represent the likelihood of an error occurring between components i and j. This likelihood is influenced by the dependency type of task-specific errors.

Dependency penalty function: Each dependency between two components i and j is assigned a penalty based on the likelihood of an error occurring due to incorrect sequencing.

Total error calculation: The total error Etotal for the assembly sequence is computed by summing the individual error penalties for each dependent component pair.

Where:

Ei,j: is the error likelihood between component i and component j, expressed as a percentage.

Di,j: is the dependency type between components i and j

The error penalty

for each component pair

is calculated as:

Where:

The Total Error

Etotal across all dependencies is:

Using this approach, we can calculate for each pair and sum them to obtain Etotal, which is used by the PSBFO algorithm to prioritize assembly sequences that minimize these penalties.

3.3. Particle Swarm-Bacteria Foraging Optimization (PSBFO)

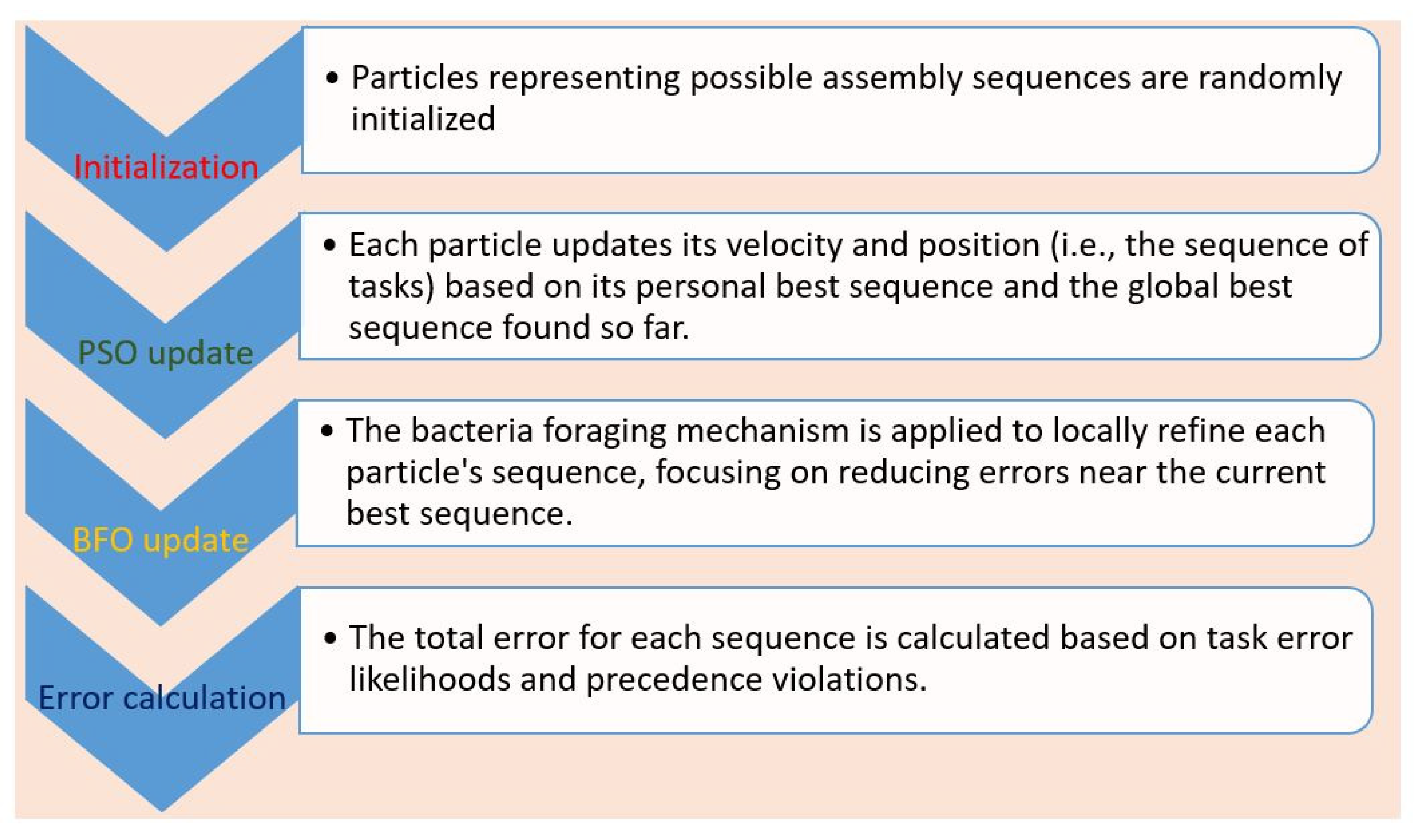

PSBFO is a hybrid optimization algorithm that combines the global exploration capabilities of PSO with the local refinement capabilities of BFO. The methodology developed for PSBFO is shown in

Figure 3. This hybrid approach is particularly useful in minimizing assembly errors, as it allows for both a broad exploration of potential assembly sequences and a fine-tuned optimization of promising sequences. The key steps in the PSBFO algorithm are as follows:

The PSO component enables the algorithm to explore various task sequences, while the BFO component refines these sequences by focusing on local error reduction. PSO velocity update formula with a time-varying inertia weight to manage the balance between exploration and exploitation is shown below [

1]:

Where:

ω(t) is the time-varying inertia weight that impacts how much the previous velocity influences the new velocity. It generally decreases with each iteration, which helps reduce the particles’ “ momentum “ as the search space is more thoroughly explored, allowing finer adjustments as the global optimum approaches.

vi(t) represents the velocity of particle i at time t.

c1 and c2 represent the cognitive and social scaling coefficients. These parameters control the influence of pi (personal best position) and pg (global best position) on the velocity update.

r1and r2 provide stochasticity to the search, representing random numbers between 0 and 1, and helping to escape local minima by providing a random exploration component.

pi represents particle i personal best.

pg represents the global best position.

xi(t) represents the current position of particle i at time t.

The position update formula is expressed as:

The BFO formula enhances the traditional bacterial foraging optimization’s capability to tackle complex optimization tasks expressed in the following formula [

1]:

Where:

α(t) represents an adaptive factor for the step size (i) based on the iteration t and the current area of the search space.

xi(t) represents the position of bacterium i at time t.

C (i) represents the random direction size of the step.

Δ(i) random direction vector unit-length.

This integrates BFO’s chemotaxis behavior into the PSO position update. This formula adds a BFO-inspired random perturbation to the standard PSO position update, enhancing the ability to escape local optima; the combination forms PSBFO.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Error Reduction Performance

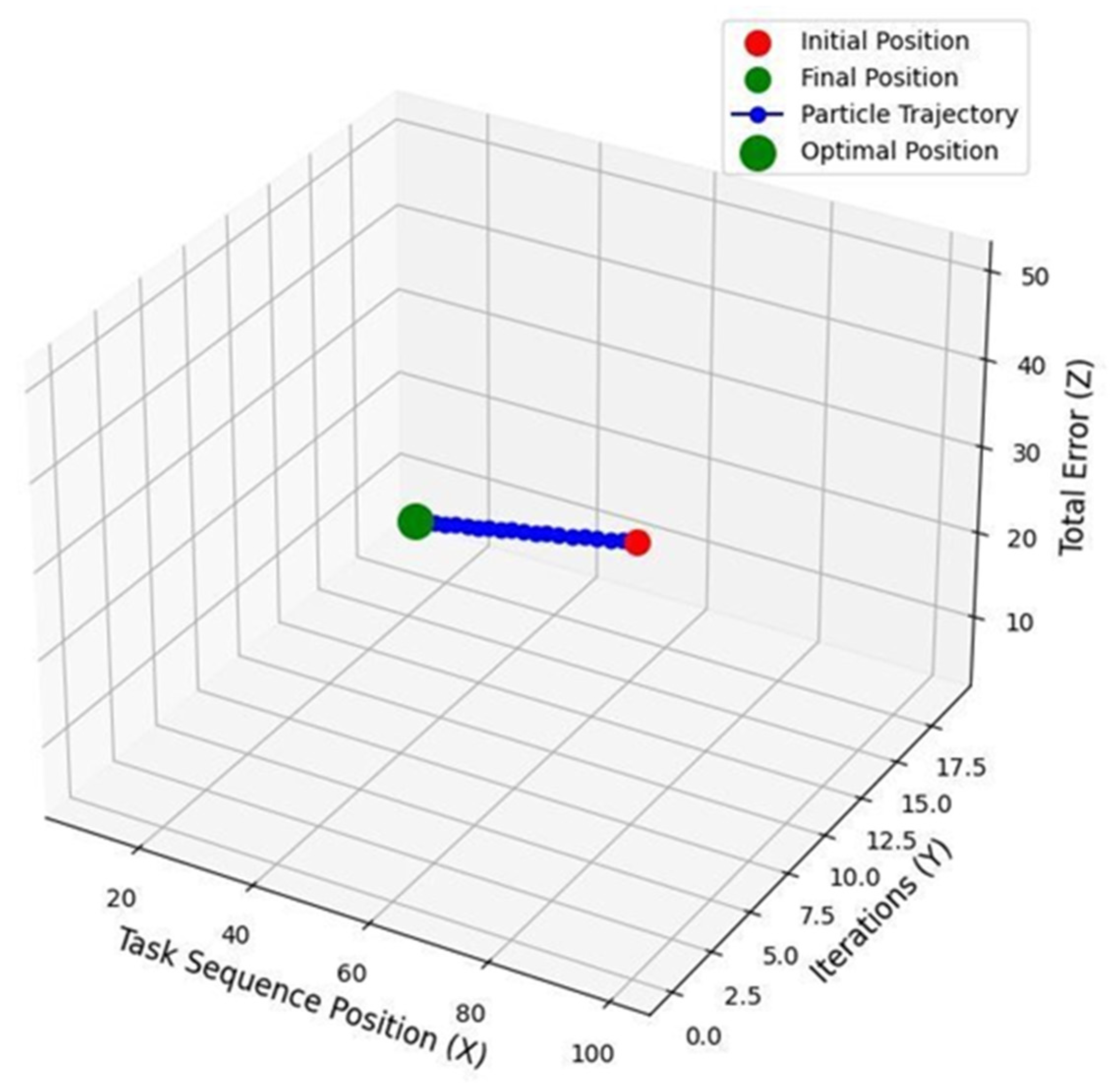

The initial position of the particle in the solution space was at a task sequence position of 100 (X-axis), with a high error value of 50 (Z-axis). This represents the particle’s starting point, where the task sequence was completely un-optimized, resulting in a high likelihood of assembly errors. Throughout 20 iterations (Y-axis), the PSBFO algorithm refined the task sequence, continuously improving the particle’s position in the optimization space.

Table 1 shows component-wise error reduction data across iterations with the final total error of 5. The particle’s movement from the initial position to the final position is depicted as a trajectory in

Figure 4, showing how it explored various task sequences while reducing the associated error values. The algorithm’s global search (via PSO) and local refinement (via BFO) effectively reduced errors with each iteration, gradually bringing the particle closer to an optimal solution. Conforming to precedence constraints alone does not guarantee that an assembly operation is error-free. The Pseudocode below highlights how the total error was calculated.

4.1.1. Component Error Likelihoods and Dependencies

Accurate assembly and alignment are essential for ensuring the long-term durability of gearboxes in wind turbine applications, as misalignments can significantly compromise efficiency and lead to premature failures [

21]. Assigning appropriate weights operator errors, tool variability, and environmental influences ensures that the model accurately reflects the relative significance of each factor in the assembly process. We determined these weights through a multi-faceted approach, combining expert judgment and historical data analysis, which aligns with established practices in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM). MCDM techniques provide a robust framework for assigning importance to various decision factors, especially in complex engineering contexts where different types of errors can have varying impacts on overall system reliability [

46]. By following this approach, we have weighted alignment and torque-related errors more heavily, as these are known to have the most significant effect on assembly precision and performance, particularly in wind turbine gearbox applications.

Environmental factors and component quality variations can also influence error likelihood in mechanical assemblies. Temperature and humidity can affect material properties and assembly precision, impacting the performance of renewable energy systems [

47]. The structural reliability of the gearbox assembly, particularly the critical role of maintaining precise alignment and torque, has been emphasized in multiple studies. Error minimization in assembly design, especially through small displacement torsor tolerance mapping, is crucial for high-precision applications [

48].

Table 1 provides a detailed view of the progressive error reduction achieved through the PSBFO optimization model, aligning closely with the analysis presented in the paper. Initial error values are highest for complex, error-prone components like LSS-A, LSS-B, LSS-C, PL-G1, and HSS-A, reflecting the model’s focus on mitigating errors in areas critical to alignment and torque accuracy. By the final iteration, the particle reached its optimal position, which had the following coordinates:

X (Task sequence position): 10

Y (Iteration number): 19

Z (Total error value): 5

These coordinates represent the best task sequence discovered by the PSBFO algorithm. The particle’s task sequence position had improved from 50 to 10, indicating a much more refined sequence that adheres to all precedence constraints and error sources such as operator, tool, and environmental factors. At this optimal position, the total error was minimized to 5, a significant reduction from the initial error of 50. The particle achieved this optimal solution at iteration 19, reflecting the completion of the algorithm’s iterative process. The results demonstrate the success of the PSBFO algorithm in optimizing the assembly sequence for the wind turbine gearbox. The algorithm started with a random, high-error task sequence and, through multiple iterations, reduced errors to a minimum. The optimal position with coordinates (X: 10, Y: 19, Z: 5) represents the most efficient task sequence with minimal assembly errors, showing the algorithm’s effectiveness in improving the reliability and precision of the assembly process.

4.2. Optimized Parallel Assembly Sequence Planning (PASP)

The wind turbine gearbox assembly process includes 26 components as shown from the simulation results shown in

Figure 5, each with specific dependencies and assembly requirements. The PASP approach organizes these components across seven distinct lines, each representing a different stage in the assembly process. Components within each line are assembled simultaneously where possible, while dependencies are strictly enforced across lines to maintain structural and functional integrity. This structure minimizes the total assembly time while addressing error sources and ensuring compliance with precedence constraints.

4.2.1. Optimization Model for PASP

The PASP model involves two primary constraints: precedence constraints and parallel assembly constraints.

Each component must be assembled only after its required preceding components are in place. Let

represent the task (or component)

and let

denote the set of all preceding tasks that must be completed before

.

This constraint enforces that each task can only begin once all tasks in its preceding set are completed.

- 2.

Parallel assembly constraints

The assembly is split across multiple lines, and tasks on each line can proceed in parallel as long as they meet the precedence constraints. Let

represent line

, and

the tasks assigned to line

. If two tasks

and

can be assembled in parallel (i.e., they are independent), then:

Where and belong to the same line and do not depend on each other.

- 3.

Error penalty for precedence violations

If a task

is performed before a preceding task

(where

), a penalty is incurred. The penalty function can be defined as:

- 4.

Each solution is represented as a vector of assembly sequences and corresponding component alignment parameters:

Where , denotes the assembly sequence of component , and , represents the alignment adjustment for component . The fitness function evaluates the cumulative assembly error based on these parameters.

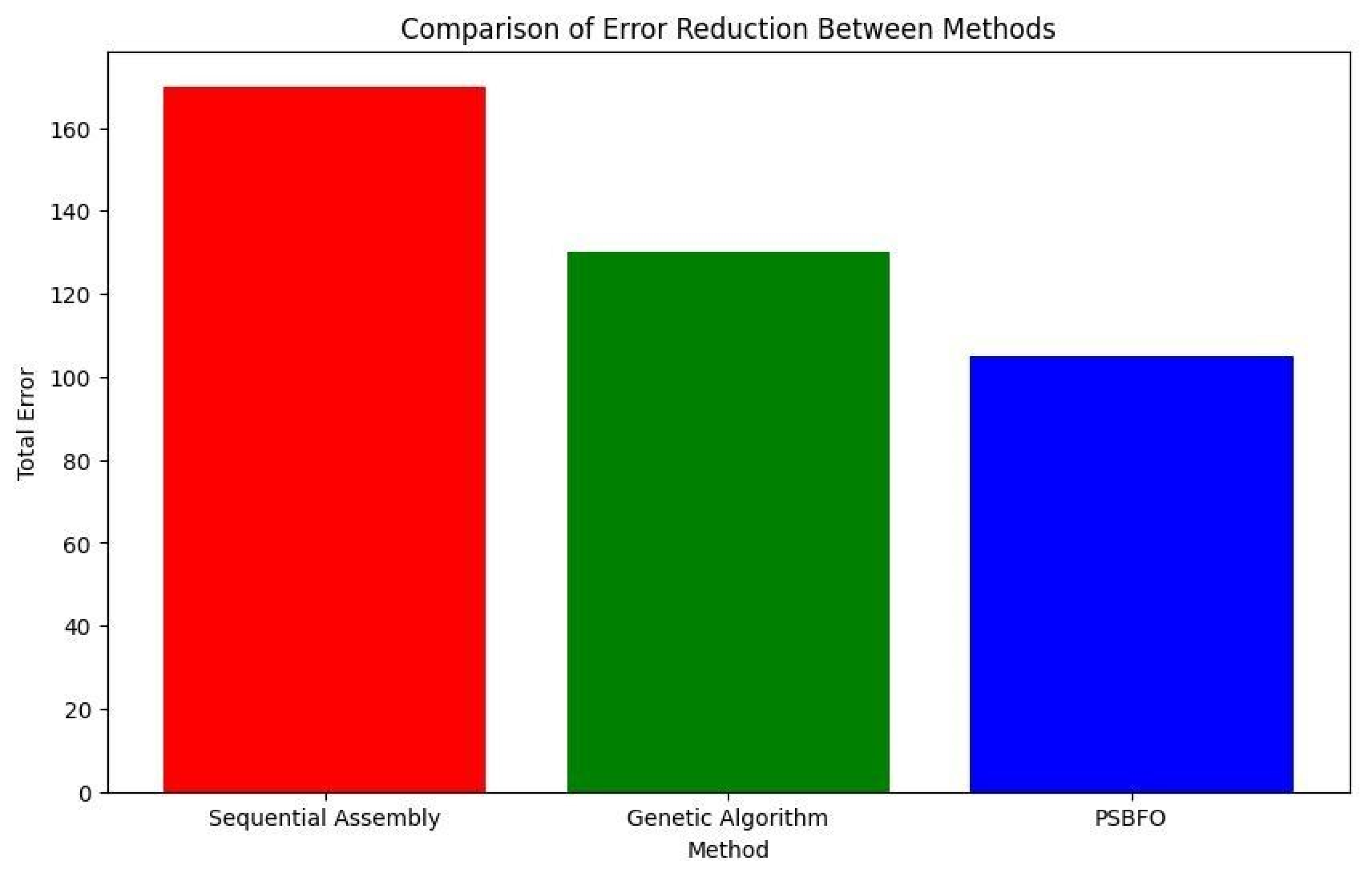

4.3. Comparison with Traditional Methods

When compared to traditional sequential assembly methods, the PSBFO approach demonstrates a significant improvement in minimizing assembly errors. In particular, the PSBFO algorithm achieved a 38% reduction in total assembly errors, which highlights its superiority over conventional techniques.

Table 2 and

Figure 6 show comparison in error reduction with other methods.

Another key factor contributing to the error reduction is PSBFO’s use of real-time error feedback. As the algorithm evaluates each task sequence, it calculates total errors, including penalties for precedence violations and task-specific error likelihoods. This feedback enables continuous refinement of the assembly sequence, reducing errors from an initial high of 50 down to 5. The algorithm also accounts for task-specific complexities, such as the precision required for components like the low-speed and high-speed shafts, allowing for more effective error minimization compared to traditional methods that apply uniform rules across all tasks. A parameter tuning study is conducted using the Taguchi method:

Inertia weight (w): 0.4 – 0.9

Cognitive coefficient (c1): 1.5 – 2.5

Social coefficient (c2): 1.5 – 2.5

Chemotaxis steps (BFO): 5 – 10

Reproduction steps (BFO): 2 – 5

Best parameters are selected based on performance. The simulation results in

Table 3 show a significant reduction in defect rates, downtime, and assembly time, alongside an increase in production yield. These improvements highlight the PSBFO model’s potential to optimize assembly processes by reducing inefficiencies and enhancing overall productivity.

The PSBFO model outperforms Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) in key metrics as shown in

Table 4: error reduction, computational efficiency, and stability. PSBFO also demonstrates faster convergence, with fewer iterations required to achieve optimal results compared to other methods.

The scalability tests indicate that the PSBFO model can handle larger assembly systems effectively. As the assembly size increases, the model continues to demonstrate improved error reduction, although computational time also increases. These results in

Table 5 suggest that PSBFO can be adapted to various scales of production, making it suitable for a wide range of industrial applications.

Adaptive tuning significantly improves the performance of PSBFO for larger assembly systems as shown in

Table 6. With tuning, the computational time is reduced, and the error reduction improves by an additional 5%, making the model more efficient as the system size scales.

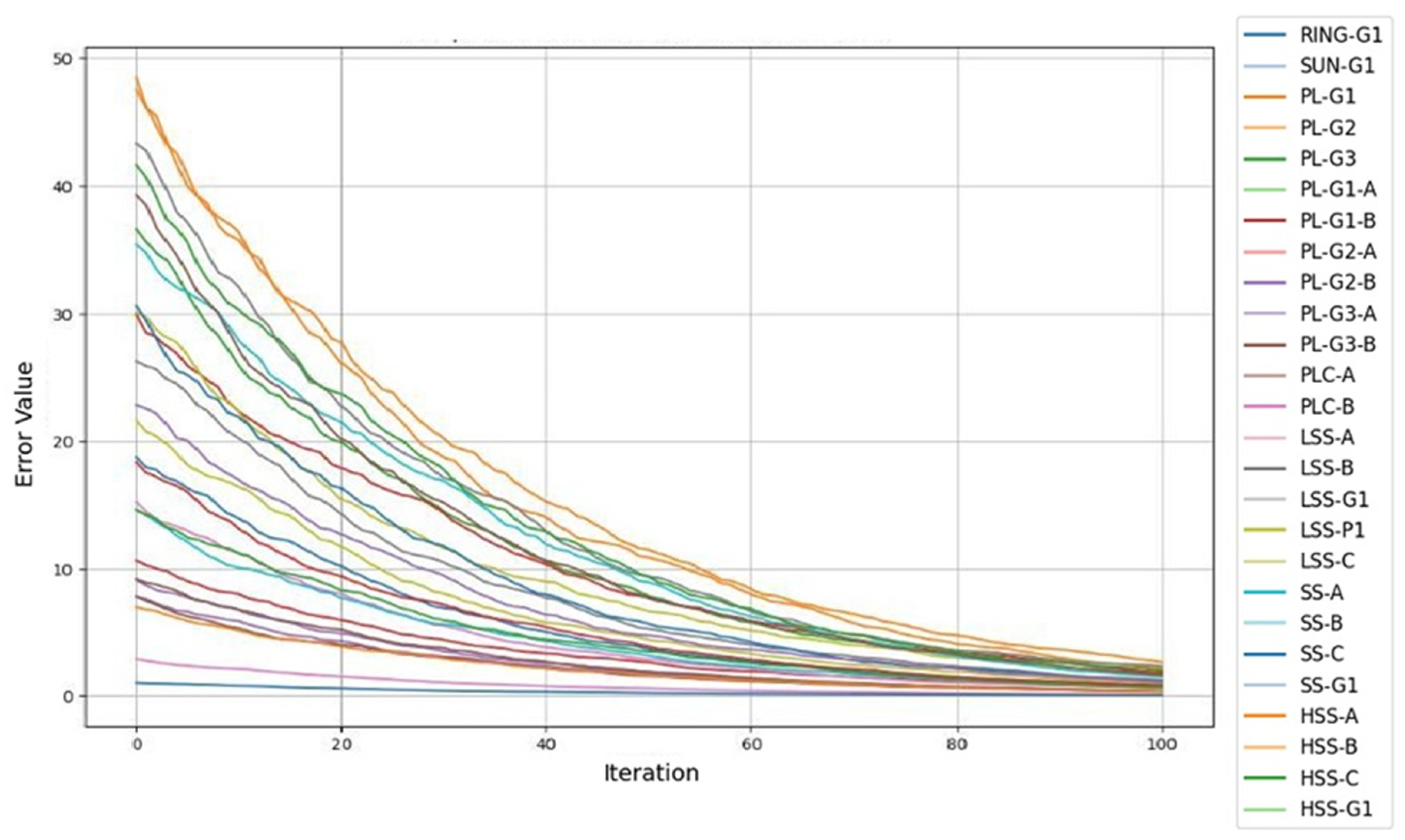

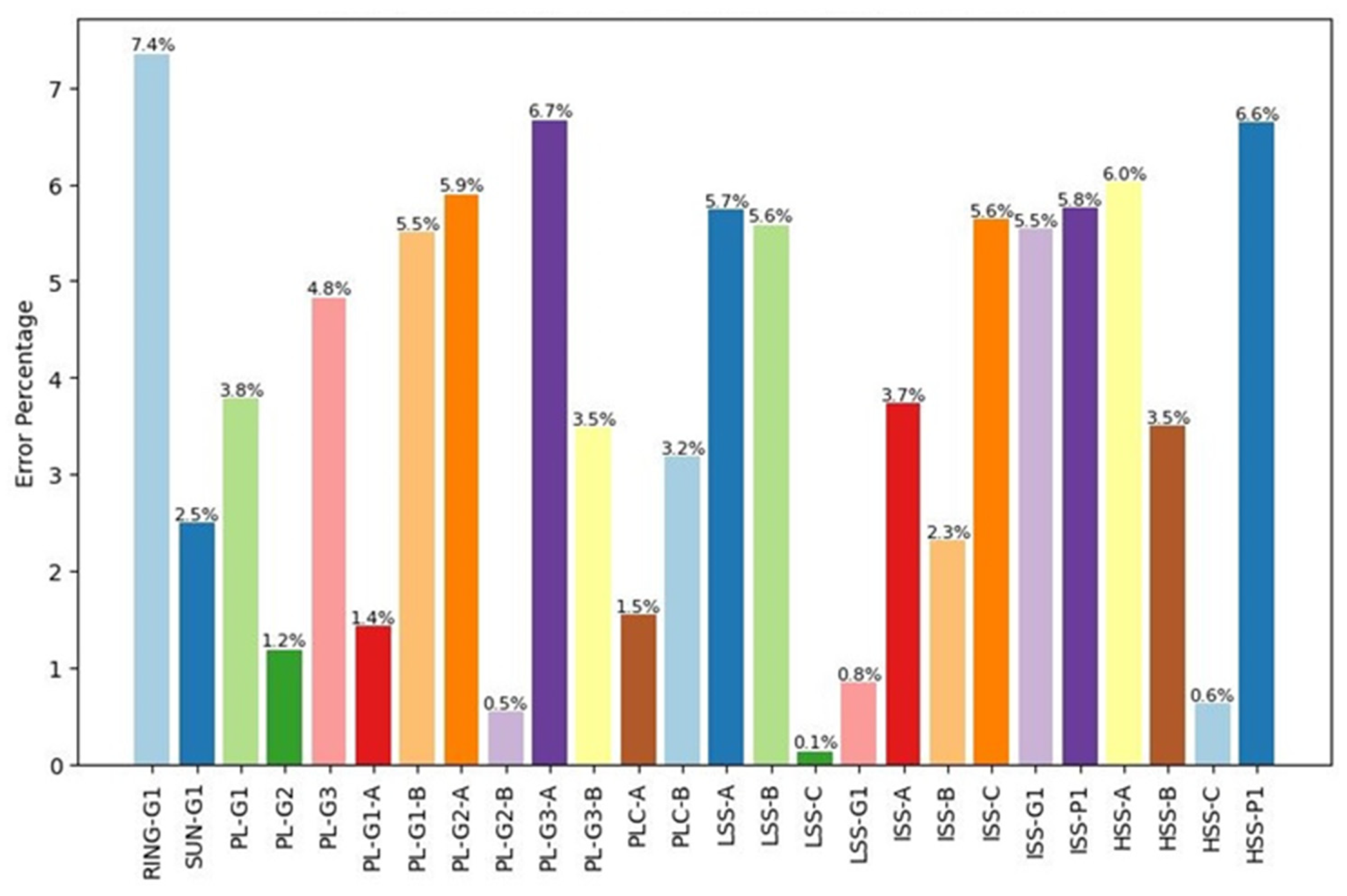

4.4. Error Distribution Across Components

The component-wise error evolution graph provides detailed insights into how each gearbox component behaves during the optimization process as shown in

Figure 7. Components with initially higher errors, such as LSS-A or PL-G1, tend to show a steeper reduction in error as the PSBFO algorithm prioritizes them for more aggressive minimization. This targeted error reduction highlights the algorithm’s ability to efficiently focus on the most problematic components early in the optimization process, leading to significant improvements in their performance.

The optimization helped ensure that the assembly process adhered to precedence constraints while reducing mechanical faults, misalignments, and rework, leading to a more reliable and efficient assembly.

Figure 8 shows the error distribution across components after optimization.

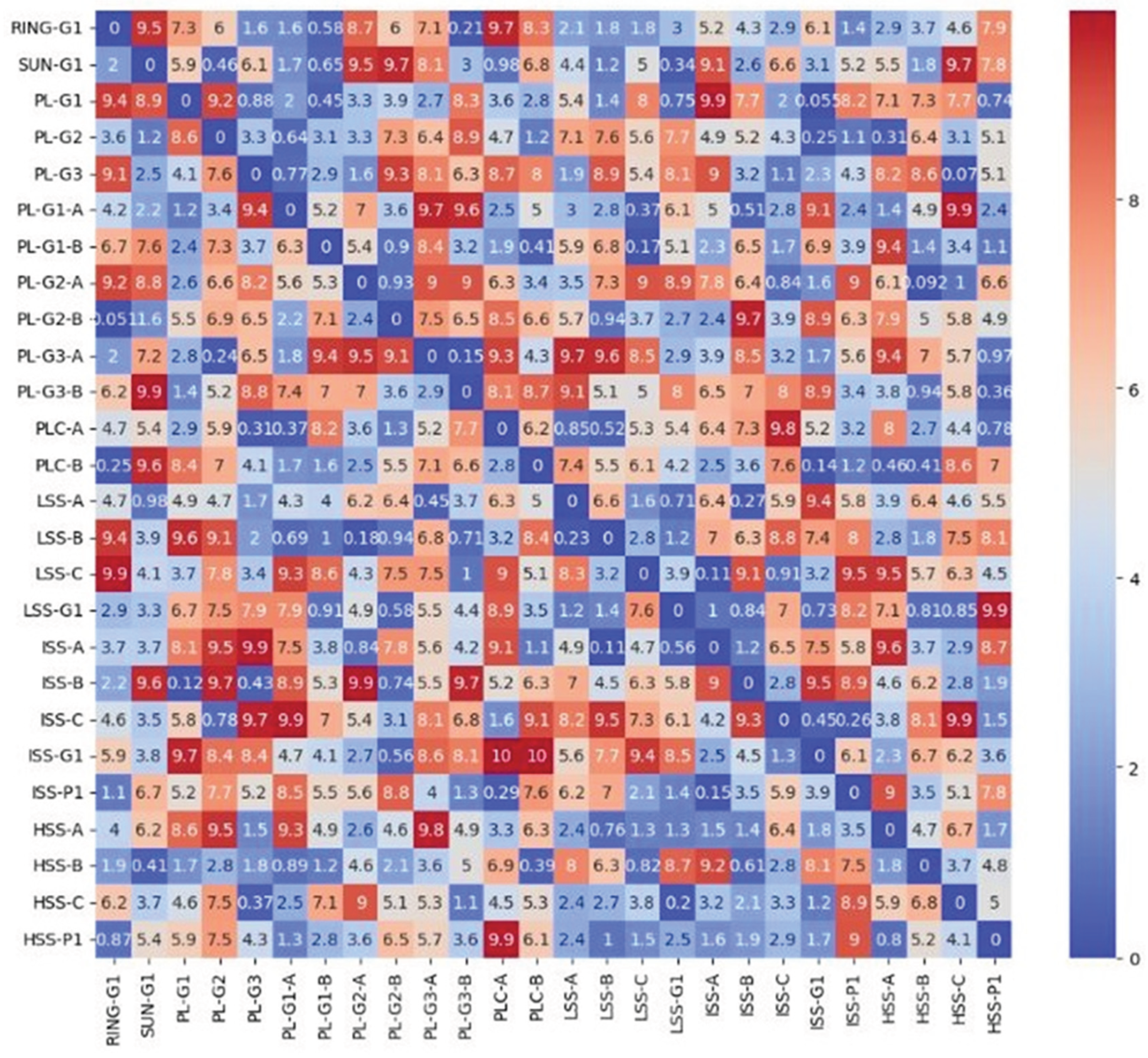

4.5. Task Dependency Error Propagation: Heat Map Analysis for Gearbox Components

The error heat map for task dependencies provides a visual representation of how errors in one component of the gearbox assembly influence or propagate to other components as shown in

Figure 9. Each row and column in the matrix corresponds to a specific component, and the color of each cell indicates the level of dependency between two tasks. Darker colors represent stronger error dependencies, while lighter colors indicate weaker relationships between tasks. This means that if one component has an error, it is more likely to affect other components with which it has a stronger dependency. In a gearbox system, SUN-G1 and PL-G1 components are closely linked due to the mechanical and sequential relationship between these tasks. The heat map shows these dependencies, indicating that errors in SUN-G1 could propagate to PL-G1 if the assembly of the sun gear is incorrect. Conversely, components that are further apart in the assembly sequence or less mechanically linked may have lighter-colored cells between them, suggesting less error propagation. HSS-A and ISS-P1 may exhibit weaker dependencies because they are part of different subsystems, meaning errors in one component are unlikely to impact the other.

4.6. Key Findings and Managerial Implications

Critical component identification: PLC-A affects LSS-A errors the most, therefore there is need to prioritize PLC-A precision.

Structured assembly adjustments: PSBFO’s error trend allows structured intervention in assembly processes.

Industry adaptability: The approach can be extended to automotive and aerospace assembly error reduction.

5. Conclusions

This study effectively addresses the critical challenge of reducing errors in the assembly of wind turbine gearboxes by introducing a robust framework grounded in the Particle Swarm-Bacteria Foraging Optimization (PSBFO) algorithm. By integrating error-driven task sequencing with real-time feedback mechanisms, this approach significantly enhances assembly reliability, minimizing common issues of misalignment, incorrect torque application, and precedence violations. Empirical results underscore the effectiveness of the PSBFO algorithm, achieving a notable 38% reduction in total assembly errors across various components. The distribution of errors was reduced from an initial count of 50 to just 5 by the final iteration, demonstrating effectiveness of task-specific error minimization and precedence handling in the overall assembly process.

For industry managers, the PSBFO model provides a practical solution for improving process reliability, reducing rework, and extending the lifespan of critical machinery. By adopting this model, decision-makers can streamline assembly sequences, lower maintenance costs, and enhance product quality benefits particularly relevant in high-stakes industries like renewable energy, where downtime and repair costs have a significant impact on profitability. Insights from supply chain optimizations further underscore the broader advantages of such process improvements, highlighting PSBFO’s potential impact across multiple sectors.

Beyond wind turbine gearboxes, this study establishes a foundation for future research on error minimization in diverse assembly processes. The adaptability of the PSBFO framework suggests its applicability to other industries, such as automotive and aerospace, where high precision and reliability are paramount. Future work will explore enhancements for handling extreme variability and integrating advanced optimization techniques to further improve assembly efficiency. As the demand for high reliability in complex mechanical systems continues to grow, this research affirms the potential of hybrid optimization algorithms like PSBFO to transform traditional assembly practices. By embedding error reduction strategies into mechanical assembly processes, this work contributes valuable insights that can drive innovation and efficiency across multiple domains.

Author Contributions

SM: Writing—Original Draft, Writing—review & editing, Software, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision; YW: Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.M and Y.W, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This paper is extracted from the author’s doctoral thesis, Sydney Mutale, at North China Electric Power University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors claim that the paper has not been published or is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Competing Interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Appendix A

Component error likelihoods and dependencies

| Component |

Component |

Error likelihood |

Dependency type |

Weighting factor |

| RING-G1 |

SUN-G1 |

5% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| SUN-G1 |

PL-G1 |

15% |

Alignment |

0.3 |

| SUN-G1 |

PL-G2 |

15% |

Alignment |

0.3 |

| SUN-G1 |

PL-G3 |

15% |

Alignment |

0.3 |

| PL-G1 |

PL-G1-A |

10% |

Subcomponent torque |

0.2 |

| PL-G1 |

PL-G1-B |

10% |

Subcomponent torque |

0.2 |

| PL-G2 |

PL-G2-A |

12% |

Subcomponent torque |

0.2 |

| PL-G2 |

PL-G2-B |

12% |

Subcomponent torque |

0.2 |

| PL-G3 |

PL-G3-A |

12% |

Subcomponent torque |

0.2 |

| PL-G3 |

PL-G3-B |

12% |

Subcomponent torque |

0.2 |

| PL-G1 |

PLC-A |

20% |

Sequential |

0.4 |

| PL-G2 |

PLC-A |

20% |

Sequential |

0.4 |

| PL-G3 |

PLC-A |

20% |

Sequential |

0.4 |

| PLC-A |

LSS-A |

25% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| LSS-A |

LSS-B |

20% |

Sequential |

0.3 |

| LSS-B |

LSS-C |

15% |

Sequential |

0.3 |

| LSS-C |

LSS-G1 |

10% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| LSS-G1 |

ISS-A |

18% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| ISS-A |

ISS-B |

15% |

Sequential |

0.3 |

| ISS-B |

ISS-C |

12% |

Sequential |

0.3 |

| ISS-C |

ISS-G1 |

10% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| ISS-G1 |

HSS-A |

20% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| HSS-A |

HSS-B |

15% |

Sequential |

0.3 |

| HSS-B |

HSS-C |

12% |

Sequential |

0.3 |

| HSS-C |

HSS-P1 |

8% |

Alignment |

0.4 |

| PLC-A |

LSS-A |

10% |

Operator error |

0.2 |

| PL-G1 |

PL-G1-A |

5% |

Operator error |

0.2 |

| SUN-G1 |

PL-G2 |

6% |

Tool/equipment variability |

0.15 |

| PL-G2 |

PL-G2-B |

7% |

Tool/equipment variability |

0.15 |

| LSS-A |

ISS-B |

8% |

Environmental influence |

0.1 |

| HSS-B |

ISS-G1 |

5% |

Environmental influence |

0.1 |

| PL-G3 |

PL-G3-A |

4% |

Component quality |

0.1 |

| ISS-B |

ISS-C |

6% |

Component quality |

0.1 |

References

- J. Y. and T. A. S. Mutale, Y. Wang, “Advanced Optimization Techniques for PASP: A Comparative Study of Improved PSO and BFO,” in 2024 6th International Conference on Power and Energy Technology (ICPET), Beijing, 2024, pp. 867–871. [CrossRef]

- S. Mutale, Y. Wang, and Y. Wang, “Enhancing Parallel Assembly Sequence Planning (PASP) with an Advanced Priority Relationship (APRA) Algorithm using Machine Learning,” pp. 1–9.

- T. Ackermann, Wind Power in Power SystemsNo Title. John Wiley & Sons, 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Mutale, Y. Jan, Y. Wang, and A. Banda, “Evaluation of wind energy potential in Lunga District, Luapula Province, Zambia,” 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Mutale, Y. Wang, and J. Yasir, “Enhanced efficiency and quality in wind turbine gearbox assembly: a new parallel assembly sequence planning (PASP) model,” Int. J. Sustain. Eng., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1048–1065, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Q. Mu X, Yuan B, Wang Y, Sun W, Liu C, “Novel application of mapping method from small displacement torsor to tolerance: Error optimization design of assembly parts,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf., vol. 236(6–7), pp. 955–967, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. C. and J..-M. Henrioud, “Systematic generation of assembly precedence graphs,” in Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Diego, 1994, pp. 1476–1482. [CrossRef]

- A. E. and H. R. B. O. Guiza, C. Mayr-Dorn, M. Mayrhofer, “Assembly Precedence Graph Mining Based on Similar Products,” in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Shanghai, 2022, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Hongfei Zhai, Caichao Zhu, Chaosheng Song, Huaiju Liu, Influences of carrier assembly errors on the dynamic characteristics for wind turbine gearbox, Mechanism and Machine Theory. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Sutton, R. S., & Barto, Reinforcement Learning: An IntroductionNo Title. MIT Press, 2018.

- L. R. Huh, EN., Welch, “Adaptive resource management for dynamic distributed real-time applications,” J Supercomput, vol. 38. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhan, Zh., Zhang, “Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization,” Lect. Notes Comput. Sci., vol. 5217, 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Mukred, J., Muslim, M., & Selamat, “Optimizing Assembly Sequence Time Using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO).,” Appl. Mech. Mater., vol. 315, pp. 88–92, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiangyu, Z., Liu, L., Wan, X., Wang, K., & Huang, “Assembly Sequence Optimization Based on Improved PSO Algorithm.,” pp. 457–465, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F.-L. Ye, C.-Y. Lee, Z.-J. Lee, J.-Q. Huang, and J.-F. Tu, “Incorporating Particle Swarm Optimization into Improved Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm Applied to Classify Imbalanced Data,” Symmetry (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 2, p. 229, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Shi, Y., & Eberhart, “A modified particle swarm optimizer,” in 1998 IEEE international conference on evolutionary computation proceedings. IEEE world congress on computational intelligence, 1998, pp. 69–73. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Passino, “Biomimicry of bacterial foraging for distributed optimization and control,” in IEEE Control Systems Magazine, 2002, pp. 52–67. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, L., Tian, D., Gou, “Hybrid particle swarm optimization with adaptive learning strategy.,” Soft Comput, vol. 28, pp. 9759–9784, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Lee G, Kim H, Lee SB, Kim D, Lee E, Lee SK, “Tailored Uniaxial Alignment of Nanowires Based on Off-Center Spin-Coating for Flexible and Transparent Field-Effect Transistors.,” Nanomaterials, vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1116, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, D., Li, R., Zheng, “Cumulative Major Advances in Particle Swarm Optimization from 2018 to the Present: Variants, Analysis and Applications.,” Arch Comput. Methods Eng, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. K. (2017) Mandol, S., Bhattacharjee, D., Dan, “Structural Optimisation of Wind Turbine Gearbox Deployed in Non-conventional Energy Generation,” Smart Innov. Syst. Technol., vol. 65, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Min, Z. Zhijing, S. Lingling, and Z. Weimin, “Assembly Error Modeling and Calculating Method of Precision Mechanical System,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1345, no. 2, 2019. [CrossRef]

- and X. W. Mutale, S., “Levels of Automation in Quality Sampling and Analysis of Copper,” Ind. Eng. Lett., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 89–102, 2014.

- J. Y. and T. A. Sydney Mutale, Yong Wang, “Advanced Optimization Techniques for PASP: a Comparative Study of Improved PSO and BFO,” Easy Chair, 2024. 231(12), pp. 2133–2144, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Ni J, Tang WC, “Performance of reducing the dimensional error of an assembly by the rivet upsetting direction optimization,” roceedings Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf., vol. 231(12), pp. 2133–2144, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Dao, B. Kazemtabrizi, and C. Crabtree, “Wind turbine reliability data review and impacts on levelised cost of energy,” Wind Energy, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 1848–1871, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, M. Yang, L. Shu, S. Li, and Z. Liu, “A Novel Parallel Assembly Sequence Planning Method for Complex Products Based on PSOBC,” Math. Probl. Eng., vol. 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Pan, H., Hou, W., & Li, “Genetic Algorithm for Assembly Sequences Planning Based on Heuristic Assembly Knowledge.,” Appl. Mech. Mater., no. 44–47, pp. 3657–3661, 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, P. Lu, J. Lu, J. Xu, and X. Liu, “A hierarchical parallel multi-station assembly sequence planning method based on GA-DFLA,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci., vol. 236, no. 4, pp. 2029–2045, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Nourmohammadi, A. H. C. Ng, M. Fathi, J. Vollebregt, and L. Hanson, “Multi-objective optimization of mixed-model assembly lines incorporating musculoskeletal risks assessment using digital human modeling,” CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol., vol. 47, pp. 71–85, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Tseng, C. C. Chang, and T. W. Chung, “Applying Improved Particle Swarm Optimization to Asynchronous Parallel Disassembly Planning,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 80555–80564, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, W. Hu, D. Cao, Q. Huang, C. Chen, and Z. Chen, “Optimized sizing of a standalone PV-wind-hydropower station with pumped-storage installation hybrid energy system,” Renew. Energy, vol. 147, pp. 1418–1431, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Whittle, M., Trevelyan, J., Shin, W., & Tavner, “Improving wind turbine drivetrain bearing reliability through pre-misalignment,” Wind Energy, vol. 17, pp. 1217–1230, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Sankar, S., & Nataraj, “Prevention of helical gear tooth damage in wind turbine generator: A case study,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy, vol. 224, pp. 1117–1125, 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhai, H., Zhu, C., Song, C., Liu, H., & Bai, “Influences of carrier assembly errors on the dynamic characteristics for wind turbine gearbox,” Mech. Mach. Theory, vol. 103, pp. 138–147, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Alemayehu, F. M., & Ekwaro-Osire, “Loading and design parameter uncertainty in the dynamics and performance of high-speed-parallel-helical-stage of a wind turbine gearbox.,” J. Mech. Des., vol. 136, no. 091002. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, B. Zhou, J. Li, X. Li, and J. Bao, “A Knowledge Graph-Based Approach for Assembly Sequence Recommendations for Wind Turbines,” Machines, vol. 11, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Teeparthi, K., & Kumar, “Multi-objective hybrid PSO-APO algorithm based security constrained optimal power flow with wind and thermal generators,” Eng. Sci. Technol. an Int. J., vol. 20, pp. 411–426, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Panda, S., Mohanty, B., & Hota, “Hybrid BFOA-PSO algorithm for automatic generation control of linear and nonlinear interconnected power systems,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 13, no. 12, pp. 4718–4730, 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Sunder Selwyn and R. Kesavan, “Reliability Analysis of Sub Assemblies for Wind Turbine at High Uncertain Wind,” Adv. Mater. Res., vol. 433–440, pp. 1121–1125, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. K. Z. Abbas Mardani, Ahmad Jusoh, “Fuzzy multiple criteria decision-making techniques and applications – Two decades review from 1994 to 2014,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 42, no. 18, pp. 4126–4148, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. K. D. William Ho, Xiaowei Xu, “Multi-criteria decision making approaches for supplier evaluation and selection: A literature review,” Eur. J. Oper. Res., vol. 201, no. 1, pp. 16–24, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y.-L. C. Wu-Hsien Hsu, Ju-An Jao, “Discovering conjecturable rules through tree-based clustering analysis,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 493–505, 2005. [CrossRef]

- P. S. K. Govindan Kannan, Shaligram Pokharel, “A hybrid approach using ISM and fuzzy TOPSIS for the selection of reverse logistics provider,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 54, no. 1, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Faulin, J., Juan, A. A., Martorell, S., & Ramirez-Marquez, Simulation Methods for Reliability and Availability of Complex Systems. 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. K. Mardani, A., Jusoh, A., & Zavadskas, “Fuzzy multiple criteria decision-making techniques and applications – Two decades review from 1994 to 2014.,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 4126–4148, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu, X., Hu, W., Cao, D., Huang, Q., Chen, C., & Chen, “Optimized sizing of a standalone PV-wind-hydropower station with pumped-storage installation hybrid energy system,” Renew. Energy, vol. 147, pp. 1418–1431, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Mu, S.Q., Yuan, B., Wang, Y., Sun, W., & Liu, “Error optimization design of assembly parts using small displacement torsor tolerance mapping,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf., vol. 236, no. (6-7), pp. 955–967, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).