1. Introduction

Wind power is a clean and renewable energy source which is gradually gaining share in the total global supply of energy, while helping to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

1,

2]. In fact, the global installed wind power capacity will exceed 1 TW by the end of 2023 [

3]. Operation and maintenance (O&M) of wind energy expenses make up a large and possibly rising portion of the cost of energy (COE), particularly when it decreases because of lower initial costs and higher performance. O&M may be responsible for 15% ~ 20% of the COE of wind energy, while for offshore WTs the ratio is 25% ~ 35% [

3].

The gearbox is a complex and expensive component of a Wind Turbine (WT), which is responsible for converting the relatively slow rotations of a turbine blades into the high speeds needed to generate electricity. The dynamics of a WT gearbox can be affected by several factors including the wind speed changes, the rotor speed, the gear ratio, the stiffness of the components, lubrication of the gears, and the applied forces (including the meshing forces, the centrifugal forces, and the gyroscopic forces) which can lead to fatigue damage.

The main sources of failures of WT gearboxes and bearings encompass the fatigue, wear, misalignment, corrosion, vibrations and resonances in the drivetrain components, and harsh environments such as wind gusts, rain, snow, high temperatures, moisture, and dust. This leads to significant cost of maintenance due to the high cost of spare parts, the need for specialized technicians, the WT downtime costs, and insurance costs to cover possible failures. Furthermore, as wind turbines increase in size and capacity, gearbox failures are expected to continue being a problem for wind power plant operators unless it can be reproduced in the laboratory, computationally modelled, and compared with actual power plant results. In fact, WT gearboxes account for over 20% of WT downtimes, and they require replacement after only 6 to 8 years, far less time than the anticipated 25 years of WT lifespan [

4].

In this sense, the size and power of wind turbine gearboxes continue to grow, reaching up to 15 megawatts (MWs) and 3 m in diameter, respectively. Torque densities of 200 newton-meters per kilogram and speed-increasing ratios up to 200 are now possible with multistage gearboxes using four or more planet epicyclic systems [

5]. Modular gearboxes have been designed to further reduce costs through economies of scale. According to the IEC 61400-4 and American Gear Manufacturers Association (AGMA) 6006 gearbox design specifications, gearboxes must have a minimum of 20-year lifespan. Operation, maintenance (O&M) and monitoring activities are required for components that present a fatigue life less than the gearbox.

There are two main types of gearboxes used in WTs, planetary gearboxes, and parallel-shaft gearboxes. Planetary gearboxes are more compact than parallel-shaft gearboxes, but they are also more expensive. The gearbox comprises many elements including the rotating shafts, gears, and bearings that entail different failure modes and reliabilities. Different standards and technical specifications deal with materials, processing, manufacture, and gearbox reliability. The reliability calculation and safety factors consider gear tooth scuffing, flank fracture and surface durability (pitting), bending strength, rolling contact fatigue, and shaft fatigue fracture. Qualitative evaluations can be made of other bearing failures, such as surface-initiated fatigue (for instance, micropitting), corrosion, adhesive wear, electrical damage, and white-etching fractures [

6,

7].

Three broad categories are presented for gearbox dynamic modelling in terms of Degrees of Freedom (DOFs) which cover a stiff multibody model that is only torsional; a rigid multibody model that has three, four, or six DOFs; or a flexible multibody model [

8]. The effects of gear and shaft lateral movements are not considered by the purely torsional stiff multibody model since it only considers the torsional DOF. Planar motion or motion in three-dimensional space is considered by stiff multibody models with three, four, or six DOF. Due to its excellent computing efficiency and tolerable analytical accuracy, it is the most widely used analysis model. The flexibility of the gear shaft, gearbox housing, planet carrier, or ring gear is frequently considered by the flexible multibody model, so that it is the most realistic model to capture the dynamic features of the wind turbine drivetrain despite its lower computation efficiency.

Classical approaches such as analytic techniques and lumped-parameter methods are used for modeling gears and bearings due to its computational efficiency [

9]. For more in-depth studies of failure modes, powerful commercial multibody simulation software packages and finite element analysis have been coupled, e.g., [

5,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The increased accuracy of these techniques comes at the expense of an increased computational burden which in practice is only applicable to static simulations. To reduce the computational cost of the finite element method (FEM) in dynamic simulations, two strategies have recently been applied. The first strategy combines the FEM with semi-analytic results from classic contact theory to remove the need for highly refined finite element meshes in the contact zone [

15]. The second strategy decreases the number of degrees of freedom in the finite element models through model order reduction approaches that are designed expressly for dynamic contact problems [

16]. Additionally, the optimization of the WT drivetrain has also been investigated [

17,

18].

The use of plain bearings in the gearbox are gaining ground because of their advantages in terms of torque density and lifespan, which is only limited by wear [

19]. Additionally, the design and O&M of gearboxes strongly depends on surface engineering and lubrication [

20,

21,

22,

23].

To face these problems digital twins (DTs) and signal based and data-driven surrogate models have recently emerged in the wind energy industry, as they can be used for health monitoring and predictive maintenance of wind turbine gearboxes [

24,

27]. Furthermore, they can help in providing an optimized and compact design of the WT gearboxes. DTs represent one more step in the disruptive effect of the global digital transformation process [

28]. A DT is a virtual representation of a physical system that can used to simulate the dynamic behavior and fatigue life prediction of the physical system under a variety of operating conditions and to predict and improve its performance and reliability [

29]. DTs make use of the real-time data obtained from sensors instrumented in physical wind turbines to improve results or validate them [

30,

31].

On the one hand, to the virtual representation of the WT can be carried out by means of high-fidelity models, such as comprehensive finite element and multi-body simulation models. They can produce very precise estimations but are computationally very expensive to calibrate using data collected from the real wind turbine. On the other hand, low-fidelity techniques that make use of Reduced Order Models (ROM) are computationally inexpensive to adjust but lack performance [

32]. Consequently, to provide real-time simulations for predictive maintenance and monitoring purposes, wind turbine drivetrain modelling relies on efficient ROM, which presents a lower computational cost if compared with traditional approaches. ROM are built by assuming simplifications of the underlying physics phenomena and using data-driven surrogate models. Hence DTs combines physics-informed models (e.g., machine learning techniques, such as Physics-Informed Neural Networks, PINNs) and operational data obtained from Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems to provide data-driven surrogate models [

33]. SCADA system records critical WT parameters from a high-fidelity sensor network such as drivetrain vibrations, temperatures, oil quality, surface roughness, high-quality pictures of damaged gear teeth, etc. For that, machine learning or deep learning techniques, statistical models, and stochastic modelling approaches are frequently used to implement the physics-informed models, to process the gathered real data, to reduce the discrepancy between observed data and model projections, and to assess the uncertainty in predicting the remaining useful life (or time to failure) of a WT gearbox [

34].

This approach provides several advantages over traditional ones, such as the flexibility in adapting to complex non-linear systems. However, to that end physics-informed models must be compatible with the linear algebra commonly used in machine learning models [

32]. Furthermore, the accuracy and quality of the physics-based models are also critical to the efficacy of these approaches, since their main drawback is the level of fidelity. Likewise, the computational cost of data processing is still an issue in large-scale applications. As a result, DTs help to reduce the cost of wind energy and to improve the reliability of wind turbines, which has promoted their dissemination in the academic world and their applications in the engineering field [

35,

36,

37].

This paper goes a step further in the current literature by presenting and applying to different case studies a digital twin approach based on computationally efficient multi-objective optimization framework, which couples powerful commercial computer-aided design tools (CAD) and computer-aided engineering (CAE) software for fault diagnosis, health monitoring and diagnosis, analyzing variable operation conditions, uncertainty assessment and sensitivity analysis in operating parameters, optimal predictive maintenance, and efficiency improvement of wind turbine gearboxes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes digital twin-based approach of the WT gearbox.

Section 3 presents the different case studies, while

Section 4 discusses the results of the simulations.

Section 4 concludes the paper and discusses the future work.

2. Digital Twin-Based Approach of the WT Gearbox

The design of a WT gearboxes requires the use of complex optimization-simulation techniques that allow estimating the key parameters and the impact on their dynamic behavior and fatigue reliability. The methodology presents an efficient design and representation of a real-world WT gearboxes by posing a multi-objective optimization framework to come up with a good compromise between the design variables and including a wide range of advantages beyond traditional engineering methods. The developed DT leads to:

Optimized designs (more compact gearboxes while maintaining power density).

Enables an automated optimization by coupling powerful engineering tools from a single workflow and to evaluate thousands of designs.

Considers the kinematics and dynamics behavior of the multistage transmission in a wind turbine gearbox, together with the structural integrity analysis of the mechanical components.

Manage a broad spectrum of explanatory and response variables.

Considers the material properties and geometric characteristics of the WT gearbox.

Deal with different WT gearbox configurations (planetary gear and parallel shaft gear arrangements, multistage transmissions, gear ratios, straight and spiral teeth, etc.).

Able to incorporate real data from sensors and to conduct testing procedures, maintenance, and monitoring of WT gearboxes.

Includes cutting-edge data analysis to balance competing goals and derive the Pareto optimal front to obtain a deeper understanding of design options and make wise selections.

Easily extendable to the design of other parts of the WT drivetrain.

A high-fidelity prognostic platform that forecasts the remaining useful life of the WT gearbox.

Maximizes efficiency, improves fault detection, diagnosis, and reliability, thus reducing failures and O&M costs.

Allow to easily simulate the gearbox operation under different parameters, conditions, and configurations and estimate the fatigue life.

Allow to perform an uncertainty assessment of the critical variables.

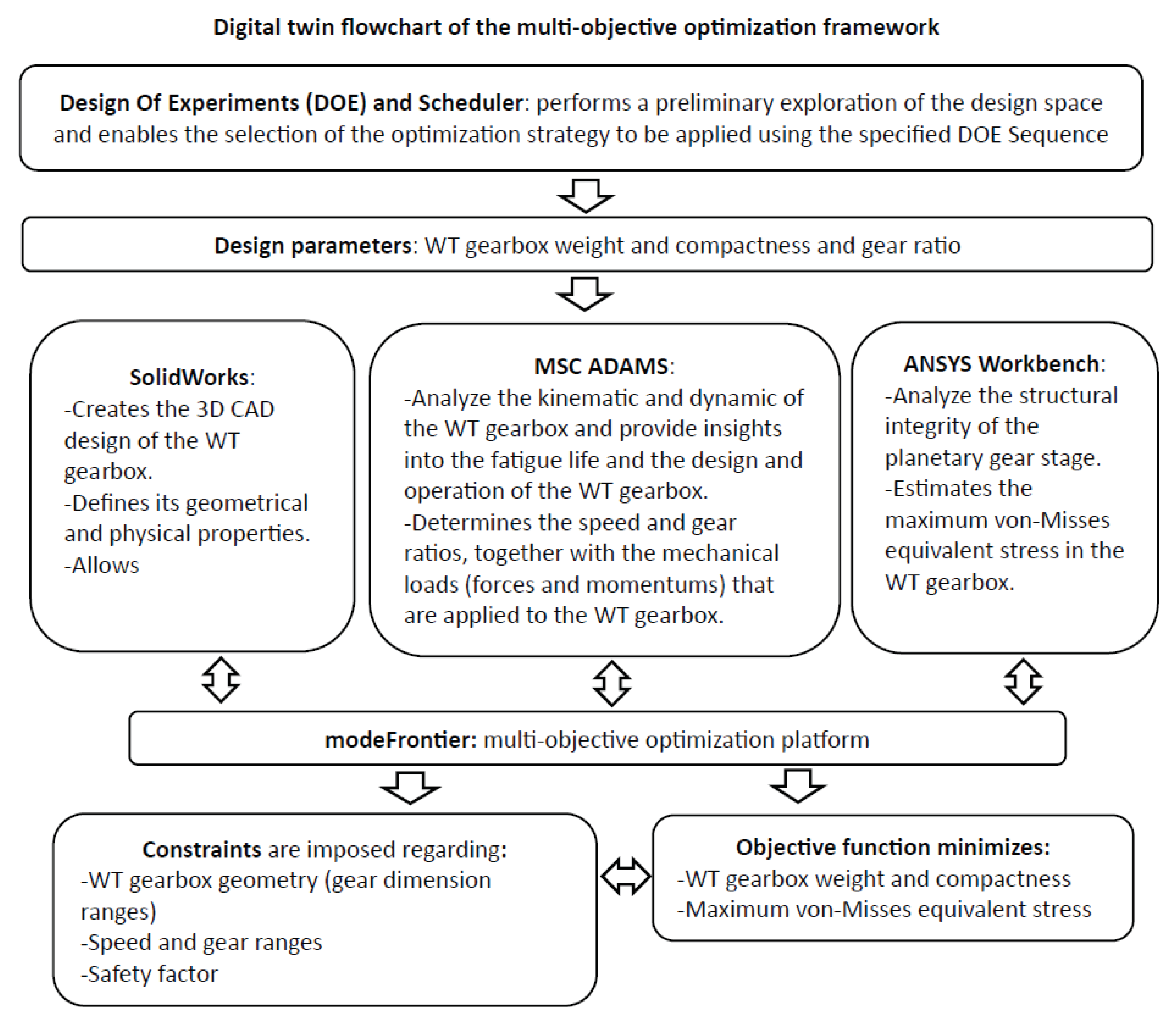

Figure 1 shows the flowchart diagram of the multi-objective optimization framework based on a digital twin approach. It illustrates the flow of information between the different powerful computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided engineering (CAE) commercial software. The digital twin representation enables accurate simulation of the behavior of the mechanical components of the gearbox and the associated multiphysics processes. The methodology comprises building a 3D CAD model of the WT gearbox in SolidWorks, including all the components and their relationships, that allow to optimize its weight (

W), volume (

V) and compactness (

C). Additionally, a multibody kinematic and dynamic analysis of the WT gearbox is performed through MSC ADAMS, which allow to analyze the fatigue life and provide insights into the design and operation of the systems. Then, an analysis of the structural integrity of the planetary gear stage is carried out using ANSYS Workbench, which is a general-purpose Finite Element Analysis (FEA) software, with the aim of minimizing the maximum stresses achieved. Eventually, the results are embedded in a multidisciplinary optimization design framework, using the tool modeFrontier, with the aim of obtaining the set of design variables that provides the optimal values. In this sense, MSC ADAMS is used to determine speed and gear ratios, together with the mechanical loads (forces and momentums) that are applied to the gearbox. Subsequently, using the geometry, material properties, and applied loads ANSYS estimates the maximum von-Mises equivalent stresses (SEQ) and strains achieved that satisfy the optimization problem constraints. This approach circumvents the problem of several multi-body simulation (MBS) models that only supports the export of linearized models (state-space representation), inadequate to represent the highly non-linear dynamics of drivetrains models [

32].

The framework allows to create a comprehensive and accurate model of a wind turbine gearbox from a single workflow and to automatically evaluate thousands of designs while balancing conflicting objectives to maximize efficiency, improve performance and reliability, and cut operational costs.

The selection of the objectives in the penalty function is based not only on the design requirements regarding the power and gear ratio of the wind turbine, but also to avoid an overparameterized optimization problem. Depending on the problem in hand, the multi-objective optimization framework using modeFrontier enables optimization using either local (usually gradient based), global (typically non-gradient based or evolutionary) techniques, or a combination of both. Additionally, a variety of strategies, including multi-strategy optimizers, heuristic optimizers, evolutionary algorithms, and gradient-based algorithms can be used. A thorough discussion of such strategies can be found in [

38].

Additionally, for the sake of conciseness the reader is referred to the specialized literature and the user documentation of the engineering tools used in this paper for a thorough explanation of the underlying theory of the multiphysics processes and the modelling implementation details. Note that methodology requires the design of the 3D mechanical components of the WT gearbox, the calculation of its kinematics and dynamics, and the estimation of stresses and deformations by means of the finite element method (FEM). Therefore, an in-depth explanation of such aspects is unattainable and out of the scope of this paper.

It is important to note that even though the modeFrontier platform has many benefits for the implementation of a multi-objective optimization problem, the reader should be aware that in order to use the platform effectively, advanced modelling skills for both the platform and the embedded engineering tools as well as knowledge of the underlying physical processes are necessary.

Then the presented methodology is in line with the development of clean technologies based on renewable energies for mitigation and adaptation to climate change [

39,

40,

41,

42].

3. Application of the Methodology to Different Case Studies

The planetary gear assembly consists of 3 primary components: a ring gear (the outer most gear), 3 planetary gears that are housed by a planetary carrier assembly (the middle gears), and a sun gear (the gear in the center of the gear set). The MSC Adams method that deals with the planetary gear uses geometry-based contact and supports shell-to-shell 3D geometry contact. It calculates true backlash based on actual working center distance and tooth thickness. It allows for consideration of out-of-plane motion with the gear pair. The parameters that define the geometry and the material of the planetary gear are presented in

Table 1. This study considers a homogeneous material for the gearbox based on structural steel with a density of 7850 kg/m

3, a Young’s modulus of 2.07E+05 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.29.

We have assumed a diameter of the rotor blades of 180 m, a wind speed of 4 m/s at start-up, 12 m/s at nominal wind speed, and 25 m/s at wind turbine shutdown. It is considered that the wind produces the maximum nominal power at a wind speed of 12 m/s, which depending on the rotor blade, corresponds to a rotor rotation speed of 14 rpm, while the generator rotation speed is of 1500 rpm. For all case studies, a gearbox with two stages, two planetaries has been considered (where the input is the planet carrier, the output is the sun, and the ring is fixed) (

Table 2). The target for the transmission ratio between the input and output (𝑖

T = i

1 · i

2) is around 107, with the transmission ratio for the first and second stages (i

1, and i

2, respectively) being around 10.35.

The design of the gearbox and the calculation of load capacity of helical gears have been carried out following the ISO 6336 standard of the International Organization for Standardization [

43].

The optimization procedure is intended to maximize the tooth fracture safety coefficient (

) rather than the gear contact safety coefficient (

) based on the ISO standard. This is because this failure tends to be catastrophic and does not generate warning signals before it occurs. In accordance with the standards, the pitch diameter (

) of each gear (e.g., sun, planet, or ring gear) is equal to the diameter of the shaft (

) supporting the gear plus a constant parameter (

), i.e.,:

where the parameter

, as defined in (Rubio et al., 2023), is equal to:

The parameter

must be adequate to provide the necessary torsional stiffness, while

takes into account the apparent gear modulus (

), the value of the depth of the keyway in the hub (

), and the tooth height [

44]. In this sense, the standard establishes that an iteration process must be carried out for gear dimensioning. For a certain material, a standard module for the gear must be chosen. Then the gear width (

b) is obtained for a specific contact safety coefficient. If

<

a solution with a higher modulus or a material for higher

/

ratio must be selected.

is the allowable bending stress by the material under the geometric and operating conditions of the gear for a given life and with a known level of confidence.

is the allowable contact stress by the material under the geometric, operating and lubrication conditions of the gear for a given life and with a known level of confidence. When a solution that satisfies X

F > X

H is achieved, if

a material with better characteristics must be selected and the iteration process resumed. Contrary, if

a material with worse characteristics must be selected and the iteration process resumed. Due to the use of simplified procedures to obtain safety coefficients, this method proposed by the standard should not be used in applications subject to extreme speed or load conditions.

Additionally, the tension at the base of the tooth (

) must fulfill that

, while the surface pressure on the tooth (

) must satisfy that

. Both tensions are corrected according to a series of coefficients that allow obtaining a better approximation to the real tension at the base of the tooth [

43].

Eventually, the calculation of the tooth fracture safety coefficient (X

F) by means of the developed optimization framework meets with the ISO standard, and it is imposed on the optimization problem through a constraint that establishes a X

F greater than a certain threshold according to each case study. Other constraints are imposed on the optimization procedure to comply with the standard and the real problem at hand, which are related to the definition of ranges of variation for the tooth width, standard module, number of teeth, and gear width (

Table 1). Additionally, the relationship between input and output shaft speeds also must fulfilled the Willis equation for planetary gears. Moreover, several geometrical conditions must be fulfilled for each stage to fulfill with the ISO standard [

9,

43], which encompass:

- The coaxiality condition entails that the number of teeth in the ring is two times the number of teeth of the planet plus the number of teeth of the sun, or in other words, that the diameter of the ring is two times the diameter of the planet plus the diameter of the sun:

- The mounting condition leads to the fact that the number of teeth of the sun plus the ring divided by the number of planets must be a positive integer number:

-The minimum number of teeth to avoid interference is obtained by means of:

-The contiguity condition:

Furthermore, to define the case studies real historical data are used to derive reasonable values for certain variables, such as the optimal rotor speed and the forces applied. We have focused on the first stage of the drivetrain as it is the most critical from the point of view of structural integrity and is subject to greater stress. Furthermore, we are performing a static analysis since the structural loads are higher for the starting moment in which the movement begins, and the inertia of the gearbox components must be overcome.

Finally, for all study cases, the aim is to design a gearbox with minimum weight (W) and volume (V), capable of transmitting the nominal power of the wind turbine (P) with a certain transmission ratio () and a maximum tooth fracture safety coefficient (XF).

The limitations of the present study involve the high computational cost of the high-fidelity models used. Moreover, when dealing with dynamics effects due to the complexity of the problem. Similarly, the developed multi-objective optimization framework has drawbacks in acquiring data and performing simulations in real-time. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is currently any digital twin development that solves all these problems satisfactorily. Therefore, the developed platform provides some novelty and presents a step forward in the current literature.

To circumvent these issues some simplifications are assumed in the present research, and in all case studies the developed DT only simulates the running state of the gearbox under the parameters and conditions provided in

Table 1, and no real-time data are used. Therefore, the methodology addresses the interaction between the physical WT and the high-fidelity virtual simulations for the digital twin optimization by making use of offline real historical datasets. The aim is to perform a predictive digital twin training to improve the detection, diagnosis, and monitoring of failures of WT gearboxes. As further research, the digital twin would make use of online real-time data to upgrade the prognostic of the WT gearboxes useful life or time to failure.

Therefore, the critical and complex communication network between the physical WT and the digital layer is beyond the scope of the present paper. For that purpose, there are different communication technologies both wired and wireless to provide secure, robust, and reliable real-time data [

45,

46].

4. Results and Discussion

The multi-objective optimization results for the different case studies are presented in

Table 3. This table shows the optimal explanatory and response variables from all feasible designs. It is worth noting that a total of 500 designs were evaluated for each case studies, in which only the feasible configurations fulfilling the ISO standard were selected. In these results, for all case studies, the minimum number of teeth to avoid interference, together with the coaxality, mounting, and contiguity equations (from 3 to 6) are fulfilled.

The proposed multi-objective optimization framework is intended to automatically find the optimal combination of the design variables using high-fidelity models and avoiding carrying out successive iterations of manual simulations. Results provide important conclusions regarding the optimal design of wind turbine gearboxes with the lowest volumes and weight and, therefore, the maximum compactness and power density compared to other designs of epicyclic trains.

For a specific set of mechanical properties of a material, there is a value in the Pareto optimal solution set of the multi-objective optimization problem that minimizes the weight (W), volume (V), compactness (C) and maximum stresses achieved (S) of the epicyclic train by acting on the value of the gear pitch diameter ), the value of the tooth width (), and the number of teeth of the gears (Z) of the epicyclic gearing. However, there is a trade-off between the competing design variables, since certain combinations of these variables favor the objective of increasing power density without compromising efficiency, while other combinations worsen it.

In this sense, very small values of lead to small gear and pitch diameter, and too large tooth width in order to withstand the stresses generated in the teeth. Then the strength properties of the material must be improved, otherwise the gear train may experience interference, excessive tooth width, unacceptably high epicyclic train mass, and low compactness. Additionally, the use of small pitch diameters with large modules results in fewer teeth, which causes interference. On the contrary, if the module is reduced the number of teeth increases, overcoming the problem of interference, but the tooth width becomes too large to ensure structural integrity. Therefore, the weight and volume of the gear train is not operational and higher values (and hence, values) must be used. As the value of increases, b decreases at larger pitch diameters; and therefore, lower weights and greater compactness of the planetary gear set are favored. However, the value of cannot be increased freely, since when increases, the volume of the epicyclic train increases as well. As a result, there is a value that minimizes the weight, volume, and compactness of the gears by acting on and values.

Other issues must be considered such as decreases as the value of increases, and that not all moduli are valid, either because they lead to interference or because is too large or small (i.e., > 2, or << ).

Moreover, the larger the , the greater the bending strength at the base of the tooth () and surface pressure on the tooth (). These values exceed the threshold leading to a failure for a given target of fracture and gear contact safety coefficients (e.g., and , respectively) and maximum allowable bending and contact stresses by the material (e.g., and , respectively). These results are in line with previous research of the same authors using analytical equations for the design of the gear train (Rubio et al., 2023).

Eventually, this reasoning supports the idea of the existence of a trade-off between the variables under consideration, which can be easily and automatically assessed using the proposed methodology. Furthermore, the methodology that allows the optimal design of the WT gearbox to support the existing loads with maximum density power, can also help to reduce mechanical failures, vibrations and increasing its fatigue life. This is because the selection of non-optimal designs (with greater masses, volumes, and stress levels) can lead to this type of anomalies over time.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has presented a digital twin-based approach for the multi-objective optimal design of wind turbine gearboxes. The developed optimization framework, utilizing a combination of CAD/CAE tools, enables high-fidelity virtual simulations and the integration of real historical datasets. The methodology allows minimizing the WT weight, volume, and maximum stresses and strains achieved without compromising efficiency. The optimization framework deals with gear ratios among stages, planetary gearset geometries and materials, together with the kinematics, dynamics, and the structural integrity of the WT gearbox. Moreover, it enables advanced data analysis for informed decision-making beyond traditional engineering methods.

This approach presents a promising avenue with the aim to enhance fault diagnosis, health monitoring, diagnosis, analyze variable operation conditions, uncertainty assessment and sensitivity analysis in operating parameters, optimize predictive maintenance, and improve the efficiency of wind turbine gearboxes. Then the methodology developed can serve as a Decision Support System (DSS) to mitigate downtimes and financial losses associated with wind turbine gearbox failures, ultimately enhancing reliability in wind energy.

The results of the case studies conducted demonstrate the usefulness of the developed DT for accurate modeling and simulation of the WT gearbox, thus allowing to optimize its design with the aim of maximizing the power density and compactness for enhanced performance and reliability; provide insights into its behavior under diverse operating conditions; and helping to the identification of potential failure modes in the gearbox.

Future research endeavors could focus on implementing a high-fidelity prognostic model to forecast the remaining useful life of gearboxes more accurately. Also to overcome certain limitations of the present work, including that the methodology should take into account dynamic aspects and conditions that change over time, such as variations in the rotation speed of the blades, as well as critical situations that are reached in the start/stop procedures of wind turbines. Additionally, exploring the integration of real-time data into the digital twin framework could further enhance predictive maintenance strategies and optimize the operational efficiency of wind turbine gearboxes. In this sense, the communication network between the physical wind turbine and the digital layer has not been dealt in the present paper, so that that the study may not provide a comprehensive overview of the entire digital twin ecosystem. Moreover, the high computational cost associated with the high-fidelity models may hinder the scalability and practical implementation of the digital twin framework in real-world wind turbine operations, especially in large-scale applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.-A.; methodology, C.L.-A. and F.R.; software, C.L.-A.; validation, C.L.-A. and F.R.; formal analysis, C.L.-A., C.D., D.G.-H.; investigation, C.L.-A. and F.R.; resources, C.L.-A., C.D., D.G.-H.; data curation, C.D., D.G.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.-A, F.R., C.D.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, C.D., F.R., D.G.-H.; supervision, C.L.-A.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Zeng, S.; Grima-Olmedo, J.; Grima-Olmedo, C. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) applied to Mechanical Engineering. Multidisciplinary Journal for Education, Social and Technological Sciences. 2022, 9, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Valero, F. Multi-objective optimization of costs and energy efficiency associated with autonomous industrial processes for sustainable growth. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021, 173, 121115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GWEC. Global wind report 2023. Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). 2023, Rue de Commerce 31, 1000 Brussels, Belgium.

- Dąbrowski, D.; Natarajan, A. Assessment of gearbox operational loads and reliability under high mean wind speeds. Energy Procedia. 2015, 80, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.R.; et al. Wind turbine drivetrains: state-of-the-art technologies and future development trends. Wind Energy Science. 2022, 7, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Fernandez, R.; Tobie, T.; Collazo, J. Increase wind gearbox power density by means of IGS (Improved Gear Surface). International Journal of Fatigue. 2022, 159, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savsani, V.; Rao, R.V.; Vakharia, D.P. Optimal weight design of a gear train using particle swarm optimization and simulated annealing algorithms. Mechanism and Machine Theory. 2010, 45, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wen, B.; Peng, Z.; Dong, X.; Qu, Y. Dynamic modeling and analysis of wind turbine drivetrain considering the effects of non-torque loads. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2020, 83, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Pedrosa, A.M. Analysis of the influence of calculation parameters on the design of the gearbox of a high-power wind turbine. Mathematics. 2023, 11, 4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.R.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. On long-term fatigue damage and reliability analysis of gears under wind loads in offshore wind turbine drivetrains. International Journal of Fatigue. 2014, 61, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.R.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. Development of a 5 MW reference gearbox for offshore wind turbines. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 1089–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Ma, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wen, B. An improved analytical method for calculating time-varying mesh stiffness of helical gears. Meccanica. 2018, 53, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Nejad, A.R.; Moan, T.; Gao, Z. Structural reliability analysis of contact fatigue design of gears in wind turbine drivetrains. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 2020, 65, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajal, K.S.; Kumarappan, P.A.; Kevin Arul, J.; Sri Vishakan, S.; Bhaskara Rao Lokavarapu. Analysis of epicyclic gears with composite material for a wind turbine gearbox. Materials Today Proceedings. 2022, 50, 5–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.; Vedmar, L. A dynamic model to determine vibrations in involute helical gears. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2003, 260, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszer, J.; Tamarozzi, T.; Desmet, W. A semi-analytic strategy for the system-level modelling of flexibly supported ball bearings. Meccanica. 2016, 51, 1503–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Zhu, C.; Hu, G. Design optimization of a wind turbine gear transmission based on fatigue reliability sensitivity. Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering. 2021, 16, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korta, J.A.; Mundo, D. Multi-objective micro-geometry optimization of gear tooth supported by response surface methodology. Mechanism and Machine Theory. 2017, 109, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Hansen, A. Focus areas in Vestas powertrain, in: Conference for Wind Power Drives 2021: Conference Proceedings.

- Sun, W.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X. Research on pre-controllable safety factors of a wind power gearbox transmission based on reliability optimisation design. Journal of Marine Engineering & Technology. 2012, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, N.; Lee, H. Tooth modification for optimizing gear contact of a wind-turbine gearbox. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science. 2015, 230, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanola, A.; Garg, H. Tribological challenges and advancements in wind turbine bearings: A review. Engineering Failure Analysis. 2020, 118, 1861–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.L.; Heuser, L.; Petersen, K.E. Prevention of “white etching cracks” in rolling bearings in Vestas wind turbines, in: Conference for Wind Power Drives 2021: Conference Proceedings.

- Moghadam, F.K.; Nejad, A.R. Online condition monitoring of floating wind turbines drivetrain by means of digital twin. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2022, 162, 108 087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwani, M.; Deshmukh, S.; Dhiman, H.S. Digital Twin framework for time to failure forecasting of wind turbine gearbox: a concept. 2022, Cornell University, https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.03513.

- Fahim, M.; Sharma, V.; Cao, T.-V.; Canberk, B.; Duong, T.Q. Machine learning-based digital twin for predictive modeling in wind turbines. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 14184–14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, E.-J.; Puig, V.; López-Estrada, F.R.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; Santos-Ruiz, I.; Osorio-Gordillo, G. Robust fault diagnosis of wind turbines based on MANFIS and zonotopic observers. Expert Systems with Applications. 2024, 235, 121095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Valero, F. Impact of digital transformation on the automotive industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021, 162, 120343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiangjun, Z.; Ming, Y.; Xianglong, Y.; Yifan, B.; Chen, F.; Yu, Z. Anomaly detection of wind turbine gearbox based on digital twin drive. In proceedings of 2020 IEEE 3rd Student Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (SCEMS). 2020, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, F.K.; de, S. Rebouças, G.F.; Nejad, A.R. Digital twin modelling for predictive maintenance of gearboxes in floating offshore wind turbine drivetrains. Forschung im Ingenieurwesen. 2021, 85, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, F.K.; Nejad, A.R. Theoretical and experimental study of wind turbine drivetrain fault diagnosis by using torsional vibrations and modal estimation. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2021, 116223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucesan, Y.A.; Viana, F.-A.C. Physics-informed digital twin for wind turbine main bearing fatigue: Quantifying uncertainty in grease degradation. Applied Soft Computing 149, Part A, 2023; 110921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlan, F.C.; Pedersen, E.; Nejad, A.R. Modelling of wind turbine gear stages for Digital Twin and real-time virtual sensing using bond graphs. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2022, 2265, 032–065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. S.; Nejad, A.R. On digital twin condition monitoring approach for drivetrains in marine applications, in: ASME 2019 38th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2019.

- Rubio, F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Zeng, S. Best practices and syllabus design and course planning applied to mechanical engineering subjects. Multidisciplinary Journal for Education, Social and Technological Sciences. 2022, 9, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Devece, C.; Zeng, S. Multiobjective optimization framework for designing a steering system considering structural features and full vehicle dynamics. Scientific Reports. 2023, 13, 19537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Zeng, S. Multiobjective optimization framework for designing a vehicle suspension system. A comparison of optimization algorithms. Advances in Engineering Software. 2023, 176, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Yang, X.-.S. Computational optimization, methods and algorithms Studies in computational intelligence. 2011, Volume 356, Springer, Berlin, Germany. ISBN 978-3-642-20858-4.

- Rubio, F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Valero, F.; Besa, A. Sustainability and optimization in the automotive sector for adaptation to government vehicle pollutant emission regulations. Journal of Business Research. 2020, 112, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Besa, J.B. Optimal allocation of energy sources in hydrogen production for sustainable deployment of electric vehicles. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2023, 188, 122290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Simón-Moya, V. Fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) applied to the adaptation of the automobile industry to meet the emission standards of climate change policies via the deployment of electric vehicles (EVs). Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021, 169, 120843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, F.; Llopis-Albert, C. Viability of using wind turbines for electricity generation on electric vehicles. Multidisciplinary Journal for Education, Social and Technological Sciences. 2019, 6, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 6336:2019: Calculation of load capacity of spur and helical gears. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- DIN 3990:1987; Calculation of Load Capacity of Cylindrical Gears. German Institute for Standardisation Registered Association: Berlin, Germany, 1987.

- Ambarita, E.E.; Karlsen, A.; Scibilia, F.; Hasan, A. Industry 4.0 Digital Twins in offshore wind farms. Wind Energy Science. 2023; Discuss. [preprint]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, B.; Wang, A.; Qian, Z. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine gearbox under limited labeled data through temporal predictive and similarity contrast learning embedded with self-attention mechanism. Expert Systems with Applications. 2024, 245, 123080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).