Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

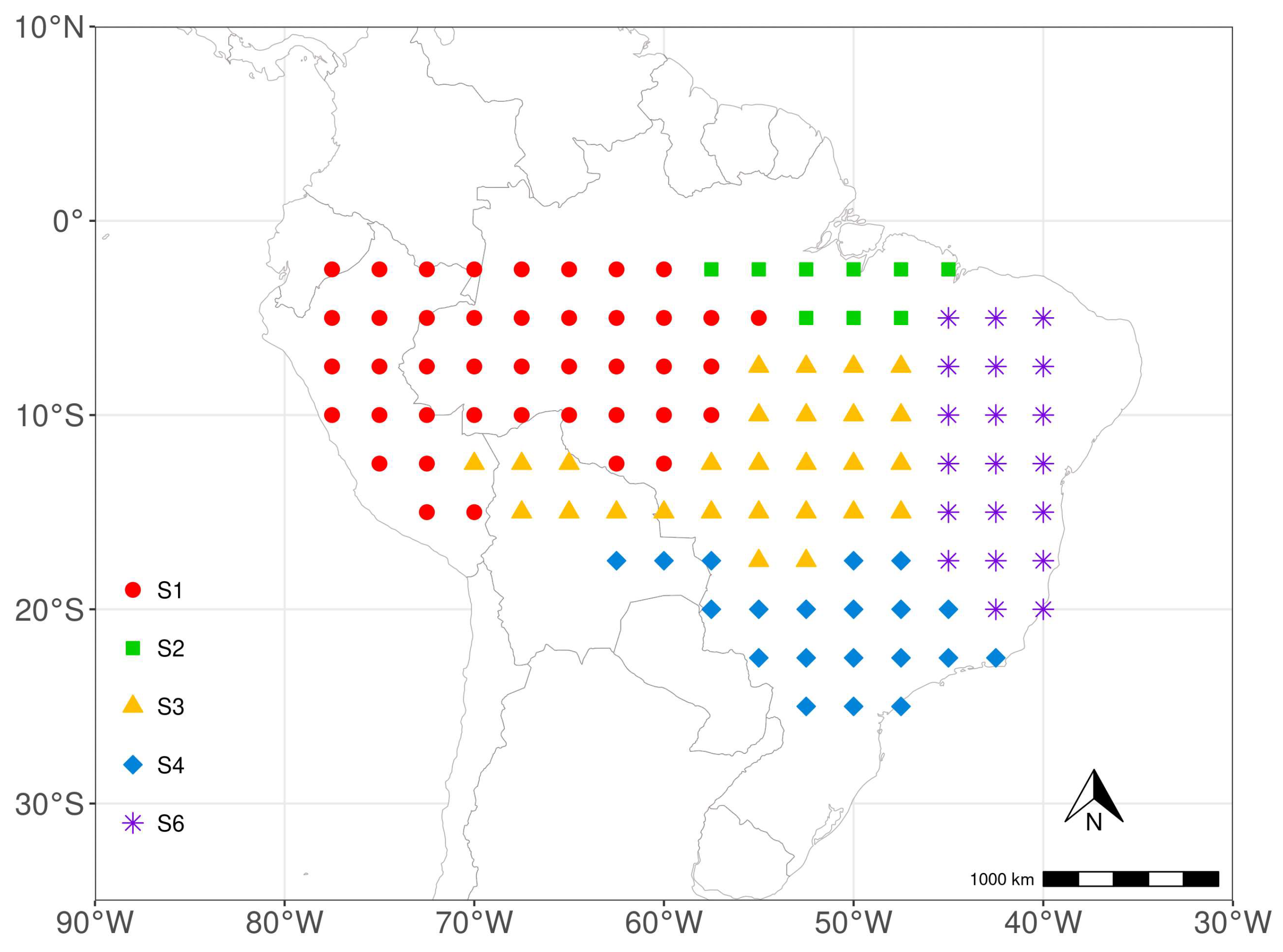

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

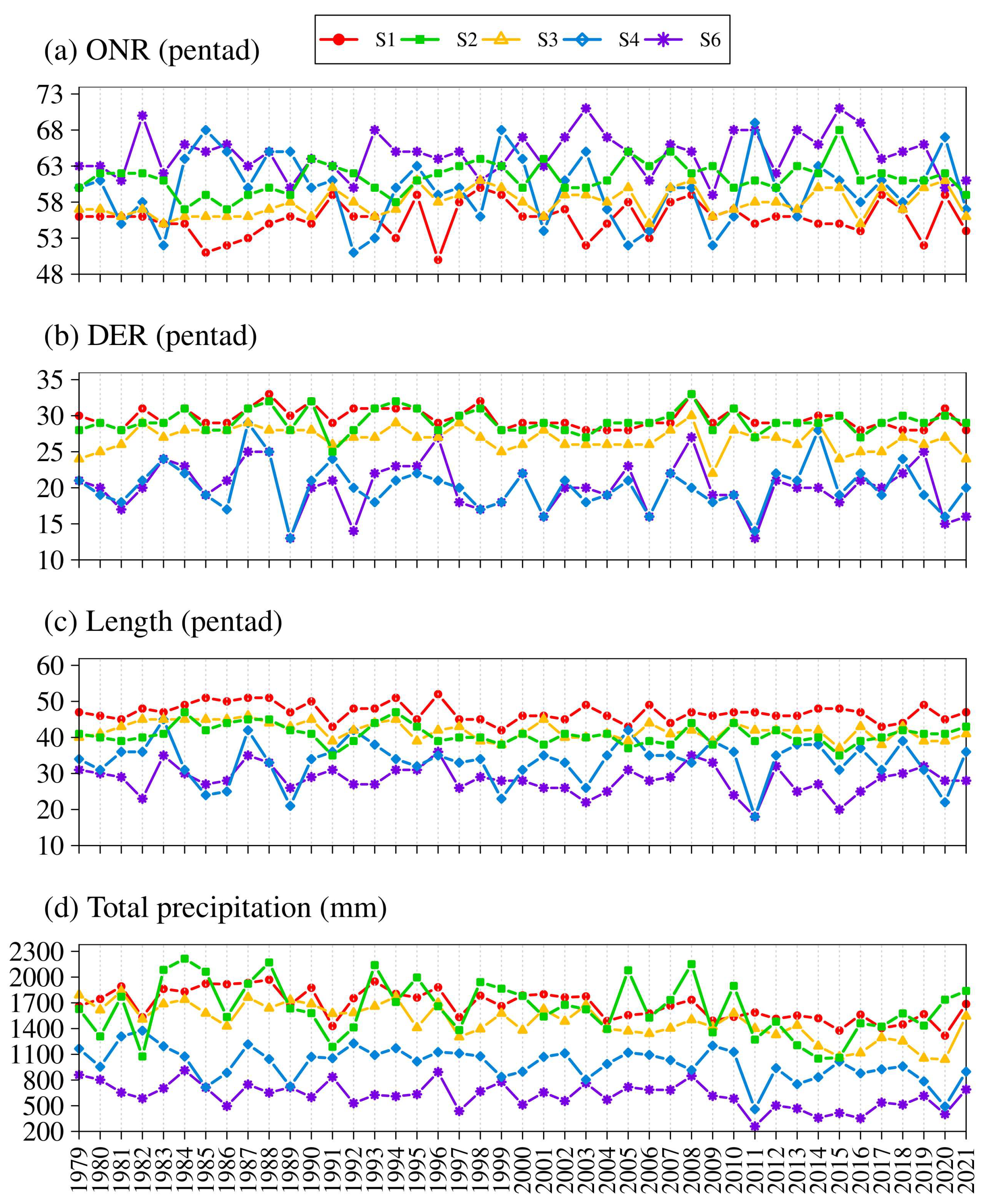

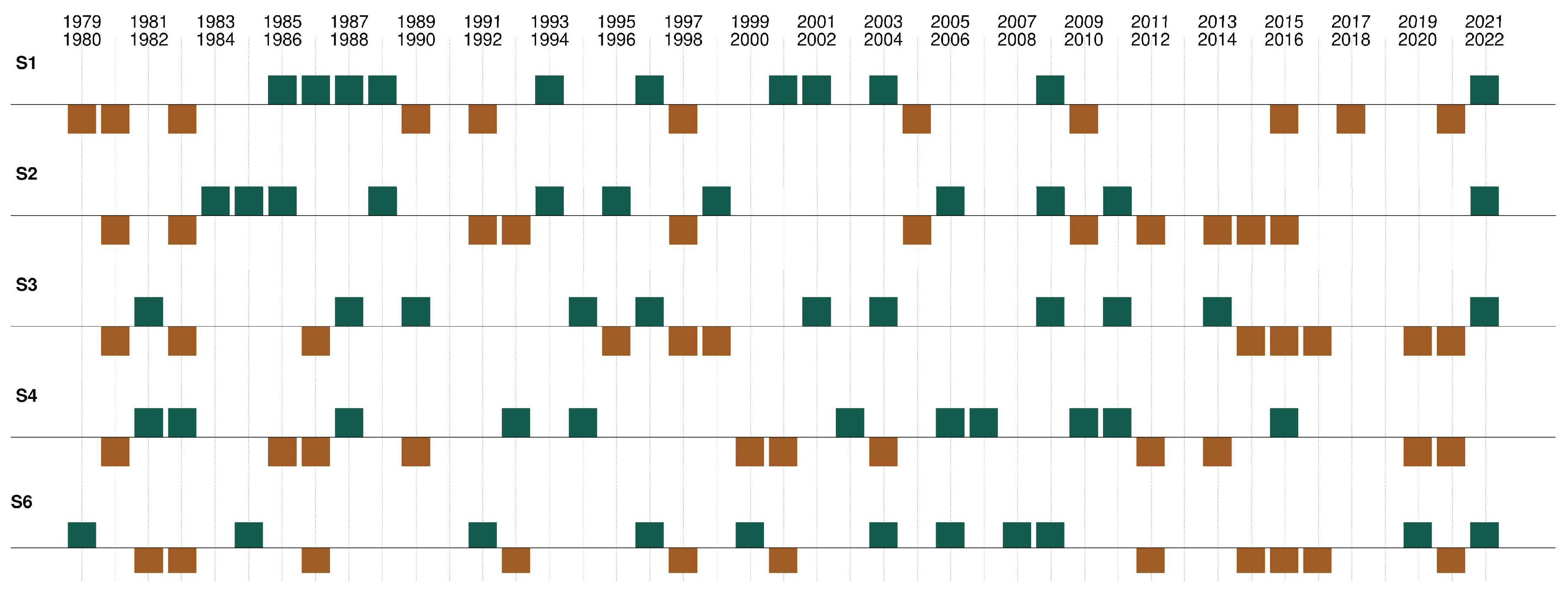

3.1. ONR, DER and Length of Rainy Seasons

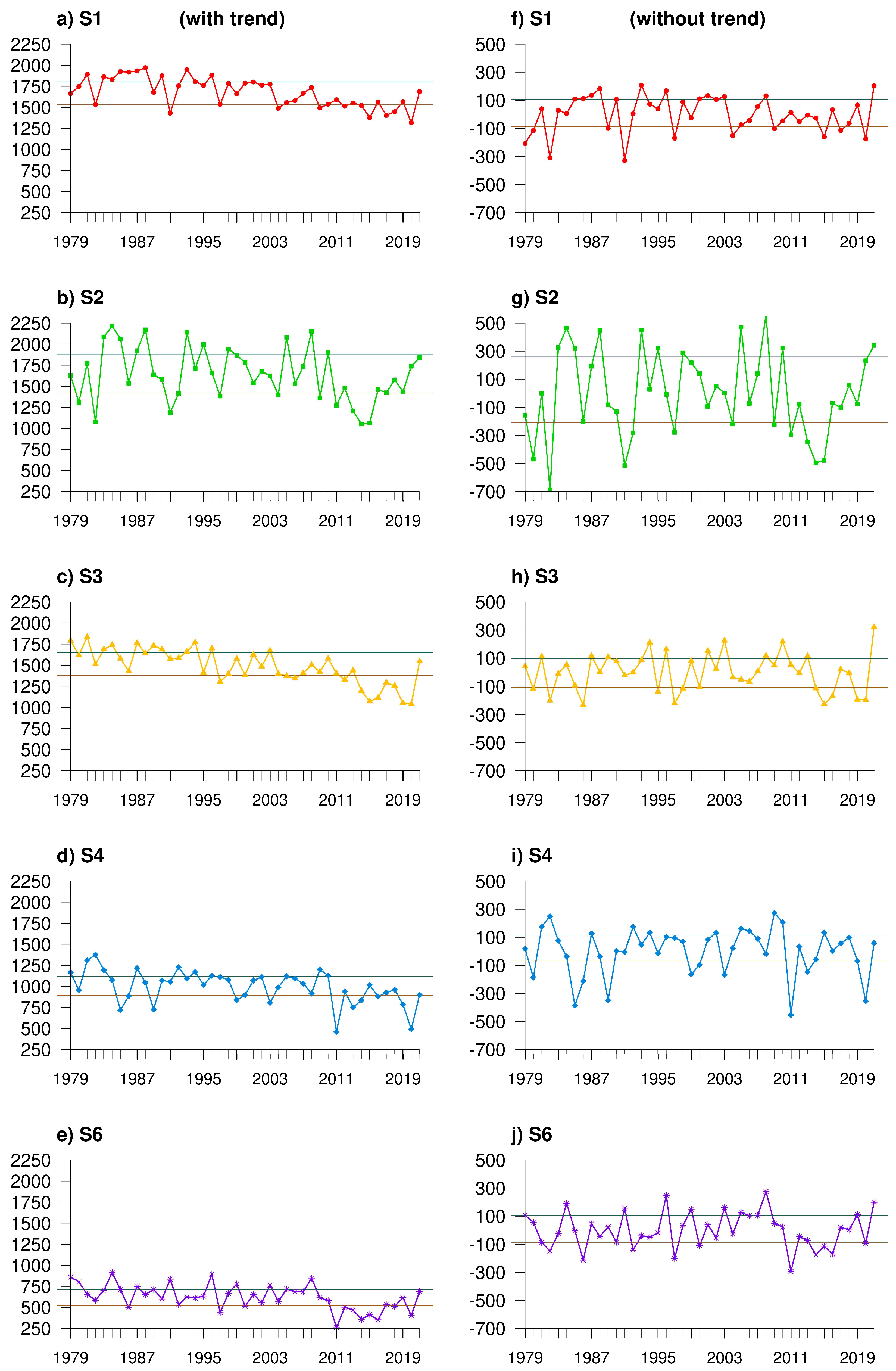

3.2. Accumulated Precipitation of the Rainy Seasons

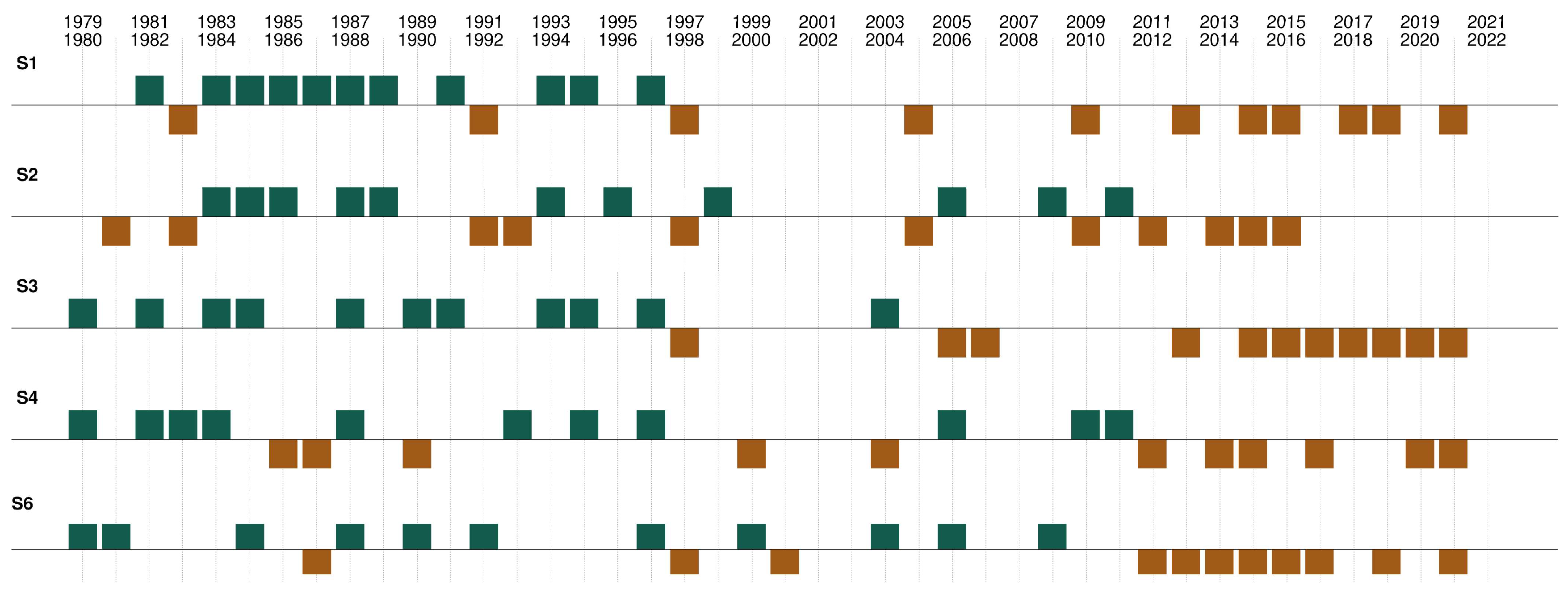

3.3. Accumulated Precipitation with No Linear Trend

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

- The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOLR | Antisymmetric Outgoing Longwave Radiation |

| DER | Demise of the Rainy Season |

| DJF | December, January and February |

| NAMS | North American Monsoon System |

| NTA | Northern Tropical America |

| OLR | Outgoing Longwave Radiation |

| ONR | Onset of the Rainy Season |

| SAMS | South American Monsoon System |

| WCB | Western Central Brazil |

References

- Marengo, J.A.; Nobre, C.A.; Tomasella, J.; Oyama, M.; Sampaio, G.; Camargo, H.; Alves, L.; Oliveira, R. The drought of Amazonia in 2005. J. Clim. 2008, 21, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.L.; Brando, P.M.; Phillips, O.L.; van der Heijden, G.M.; Nepstad, D. The 2010 Amazon drought. Science 2011, 331(6017), 554. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.A.S.; Cavalcanti, I.A.F.; Costa, S.M.S.; Freitas, S.R.; Ito, E.R.; Luz, G.; Santos, A.F.; Nobre, C.A.; Marengo, J.A.; Pezza, A.B. Climate diagnostics of three major drought events in the Amazon and illustrations of their seasonal precipitation predictions. Meteorol. Appl. 2012, 19, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Espinoza, J.C. Extreme seasonal droughts and floods in Amazonia: causes, trends and impacts. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastefanou, P.; Zang, C.S.; Angelov, Z.; Castro, A.A.; Jimenez, J.C.; Rezende, L.F.C.; Ruscica, R.C.; Sakschewski, B.; Sörensson, A.A.; Thonicke, K.; Vera, C.; Viovy, N.; Randow, C.V.; Rammig, A. Recent extreme drought events in the Amazon rainforest: Assessment of different precipitation and evapotranspiration datasets and drought indicators. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 3843–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.C.; Jimenez, J.C.; Marengo, J.A.; Schöngart, J.; Ronchail, J.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Ribeiro, J.V.M. The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Tomasella, J.; Soares, W.R.; Alves, L.M.; Nobre, C.A. Extreme climatic events in the Amazon basin: Climatological and hydrological context of recent floods. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 107, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Alves, L.M.; Soares, W.R.; Rodriguez, D.A. Two Contrasting Severe Seasonal Extremes in Tropical South America in 2012: Flood in Amazonia and Drought in Northeast Brazil. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 9137–9154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.C.; Ronchail, J.; Frappart, F.; Lavado, W.; Santini, W.; Guyot, J.L. The major floods in the Amazonas River and tributaries (Western Amazon Basin) during the 1970–2012 period: A focus on the 2012 flood. J. Hydrometeorol. 2013, 14, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.C.; Marengo, J.A.; Ronchail, J.; Carpio, J.M.; Flores, L.N.; Guyot, J.L. The extreme 2014 flood in south-western Amazon basin: the role of tropical-subtropical South Atlantic SST gradient. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 124007 (9 pp). [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.C.; Marengo, J.A.; Schöngart, J.; Jimenez, J.C. The new historical flood of 2021 in the Amazon River compared to major floods of the 21st century: atmospheric features in the context of the intensification of floods. Weather Clim. Extremes 2022, 35, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.A.S.; Oliveira, C.P.; Ambrizzi, T.; Reboita, M.S.; Carpenedo, C.B.; Campos, J.L.P.S.; Tomaziello, A.C.N.; Pampuch, L.A.; Custódio, M.S.; Dutra, L.M.M.; Rocha, R.P.; Rehbein, A. The 2014 southeast Brazil austral summer drought: regional scale mechanisms and teleconnections. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 46, 3737–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Seluchi, M.E.; Cunha, A.P.; Cuartas, L.A.; Gonçalves, D.; Sperling, V.B.; Ramos, A.M.; Dolif, G.; Saito, S.; Bender, F.; Lopes, T.R.; Alvalá, R.C.; Moraes, O.L. Heavy rainfall associated with floods in southeastern Brazil in November–December 2021. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 3617–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.B.; Cavalcanti, I.F.A.; Hada, K. Annual variation of rainfall over Brazil and water vapor characteristics over South America. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1996, 101, 26539–26551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Lau, K.M. Does a monsoon climate exist over South America? J. Clim. 1998, 11, 1020–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.; Liebmann, B.; Kousky, V.E.; Filizola, N.; Wainer, I. On the onset and end of the rainy season in the Brazilian Amazon Basin. J. Clim. 2001, 14, 833–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.A.; Kousky, V.E.; Ropelewski, C.F. The South America monsoon circulation and its relationship to rainfall over West-Central Brazil. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebmann, B.; Camargo, S.J.; Seth, A.; Marengo, J.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Allured, D.; Fu, R.; Vera, C.S. Onset and end of the rainy season in South America in Observations and the ECHAM 4.5 Atmospheric General Circulation Model. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 2037–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Kayano, M.T. Determination of the onset dates of the rainy season in central Amazon with equatorially antisymmetric outgoing longwave radiation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009, 97, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Kayano, M.T. Moisture and heat budgets associated with the South American monsoon system and the Atlantic ITCZ. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 2154–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Kayano, M.T. Some considerations on onset dates of the rainy season in Western-Central Brazil with antisymmetric outgoing longwave radiation relative to the equator. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Kayano, M.T. Multidecadal variability of moisture and heat budgets of the South American monsoon system. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 121, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Calheiros, A.J.P.; Kayano, M.T. Revised method to detect the onset and demise dates of the rainy season in the South American Monsoon areas. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 126, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.R.; Kayano, M.T.; Calheiros, A.J.P.; Andreoli, R.V.; Souza, R.A.F. Moisture and heat budgets of the South American monsoon system: climatological aspects. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 130, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.A.M.; Garcia, S.R.; Kayano, M.T.; Calheiros, A.J.P.; Andreoli, R.V. Onset and demise dates of the rainy season in the South American monsoon region: A cluster analysis result. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 1354–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade, U.A.; Garcia, S.R.; Torres, R.R. Tendência dos índices de extremos climáticos observados e projetados no Estado de Minas Gerais. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2017, 32, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.H.; Ambrizzi, T.; Liebmann, B. Extreme precipitation events and their relationship with ENSO and MJO phases over northern South America. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 2977–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, S.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Adams, D.K.; Castro, C.L.; Cavalcanti, I.F.A. Current and Future Variations of the Monsoons of the Americas in a Warming Climate. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2019, 5, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céron, W.L.; Kayano, M.T.; Andreoli, R.V.; Canchala, T.; Avila-Diaz, A.; Ribeiro, I.O.; Rojas, J.D.; Escobar-Carbonari, D.; Tapasco, J. New insights into trends of rainfall extremes in the Amazon basin through trend-empirical orthogonal function (1981–2021). Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 3955–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.C.; Marengo, J.A.; Lemes, M.R. Analysis of extreme rainfall and landslides in the metropolitan region of the Paraiba do Sul River Valley and North Coast of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 3927–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón, W.L.; Kayano, M.T.; Andreoli, R.V.; Avila-Diaz, A.; Ayes, I.; Freitas, E.D.; Martins, J.A.; Souza, R.A.F. Recent intensification of extreme precipitation events in the La Plata Basin in Southern South America (1981–2018). Atmos. Res. 2021, 249, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Lau, K.M. Principal modes of interannual and decadal variability of summer rainfall over South America. Int. J. Climatol. 2001, 21, 1623–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.M.; Laureanti, N.C.; Rodakoviski, R.B.; Gama, C.B. Interdecadal variability and extreme precipitation events in South America during the monsoon season. Clim. Res. 2016, 68, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayano, M.T.; Andreoli, R.V.; Souza, R.A.F. El Niño–Southern Oscillation related teleconnections over South America under distinct Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and Pacific Interdecadal Oscillation backgrounds: La Niña. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 1359–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayano, M.T.; Andreoli, R.V.; Souza, R.A.F. Pacific and Atlantic multidecadal variability relations to the El Niño events and their effects on the South American rainfall. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 2183–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Carvalho, L.M.V. Climate Change in the South American Monsoon System: Present Climate and CMIP5 Projections. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 6660–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, P.; Fu, R.; Vera, C.; Rojas, M. A correlated shortening of the North and South American monsoon seasons in the past few decades. Clim. Dyn. 2015, 45, 3183–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, I.C.; Arias, P.A.; Rojas, M. Evaluation of multiple indices of the South American monsoon. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, E2801–E2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.M.; Tedeschi, R.G. ENSO and extreme rainfall events in South America. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 1589–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, F.E.; Grimm, A.M. The role of synoptic and intraseasonal anomalies in the life cycle of summer rainfall extremes over South America. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 46, 3041–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA/CIRES (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences) OLR data. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.olrcdr.interp.html (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Xie, P.; Chen, M.; Yang, S.; Yatagai, A.; Hayasaka, T.; Fukushima, Y.; Liu, C. A gauge-based analysis of daily precipitation over East Asia. J. Hydrometeorol. 2007, 8, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shi, W.; Xie, P.; Silva, V.B.S.; Kousky, V.E.; Higgins, R.W.; Janowiak, J.E. Assessing objective techniques for gauge-based analyses of global daily precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D04110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmetz, J.; Liu, Q. Outgoing longwave radiation and its diurnal variation at regional scales derived from Meteosat. J. Geophys. Res. 1988, 93, 11192–11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousky, V.E. Pentad outgoing longwave radiation climatology for the South American sector. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 1988, 3, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Liebmann, B.; Smith, C.A. Description of complete (interpolated) outgoing longwave radiation data set. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1996, 77, 1275–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, C.; Higgins, W.; Amador, J.; Ambrizzi, T.; Garreaud, R.; Gochis, D.; Gutzler, D.; Lettenmaier, D.; Marengo, J.; Mechoso, C.R.; Nogues-Paegle, J.; Dias, P.L.S.; Zhang, C. Toward a unified view of the American Monsoon Systems. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 4977–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.M.; Vogel, R.M.; Kroll, C.N. Trends in floods and low flows in the United States: impact of spatial correlation. J. Hydrol. 2000, 240, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Pilon, P.; Phinney, B.; Cavadias, G. The influence of autocorrelation on the ability to detect trend in hydrological series. Hydrol. Process. 2002, 16, 1807–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, M.T.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Liebmann, B.; Silva Dias, M.A. A comprehensive analysis of trends in extreme precipitation over southeastern coast of Brazil. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Non-parametric test against trend. Econometrika 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods, 4th ed.; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Grimm, A.M.; Cavalcanti, I.F.A. Influence of Central and East ENSO on extreme events of precipitation in South America during austral spring and summer. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 2045–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, N.; Bookhagen, B.; Marengo, J.A.; Marwan, N.; von Storch, J.S.; Kurths, J. Extreme rainfall of the South American Monsoon system: A dataset comparison using complex networks. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 1031–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, N.; Bookhagen, B.; Marwan, N.; Kurths, J. Spatiotemporal characteristics and synchronization of extreme rainfall in South America with focus on the Andes Mountain range. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 46, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, J.; Arias, P.; Vieira, S.; Martínez, J. Influence of longer dry seasons in the Southern Amazon on patterns of water vapor transport over northern South America and the Caribbean. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 2647–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandonadi, L.; Acquaotta, F.; Fratianni, S.; Zavattini, J.A. Changes in precipitation extremes in Brazil (Paraná River Basin). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 123, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafee, S.A.A.; Freitas, E.D.; Martins, J.A.; Martins, L.D.; Domingues, L.M.; Nascimento, J.M.P.; Machado, C.B.; Santos, E.B.; Rudke, A.P.; Fujita, T.; Souza, R.A.F.; Hallak, R.; Uvo, C.B. Spatial Trends of Extreme Precipitation Events in the Paraná River Basin. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2020, 59, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Diaz, A.; Abrahão, G.; Justino, F.; Torres, R.; Wilson, A. Extreme climate indices in Brazil: evaluation of downscaled earth system models at high horizontal resolution. Clim. Dyn. 2020, 54, 5065–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.A.; Marengo, J.A.; Seluchi, M.E.; Cuartas, L.A.; Alves, L.M. Some characteristics and impacts of the drought and water crisis in Southeastern Brazil during 2014 and 2015. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2016, 8, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Alves, L.M.; Alvalá, R.C.S.; Cunha, A.P.; Brito, S.; Moraes, O.L.L. Climatic characteristics of the 2010–2016 drought in the semiarid Northeast Brazil region. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2018, 90, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jong, P.; Tanajura, C.A.S.; Sánchez, A.S.; Dargaville, R.; Kiperstok, A.; Torres, E.A. Hydroelectric production from Brazil’s São Francisco River could cease due to climate change and inter-annual variability. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1540–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, D.A.; Dos Santos, C.A.C.; Wardlow, B.D.; Anderson, M.C.; Schiltmeyer, A.V.; Tadesse, T.; Svoboda, M.D. Use of remote sensing indicators to assess effects of drought and human-induced land degradation on ecosystem health in Northeastern Brazil. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 213, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S | Z | p-value | Sen’s slope | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | ONR | 59 | 0.6180 | 0.5366 | 0.0000 |

| DER | -185 | -2.0035 | 0.0451 | 0.0000 | |

| Length | -140 | -1.4691 | 0.1418 | -0.0435 | |

| TP | -407 | -4.2490 | 0.0000 | -10.5465 | |

| S2 | ONR | 142 | 1.4958 | 0.1347 | 0.0370 |

| DER | 25 | 0.2581 | 0.7963 | 0.0000 | |

| Length | -113 | -1.1841 | 0.2364 | -0.0323 | |

| TP | -173 | -1.8001 | 0.0719 | -7.4769 | |

| S3 | ONR | 223 | 2.3646 | 0.0180 | 0.0588 |

| DER | -176 | -1.8698 | 0.0615 | -0.0333 | |

| Length | -265 | -2.7937 | 0.0052 | -0.0833 | |

| TP | -505 | -5.2746 | 0.0000 | -12.8134 | |

| S4 | ONR | -22 | -0.2212 | 0.8249 | 0.0000 |

| DER | -62 | -0.6445 | 0.5193 | 0.0000 | |

| Length | 26 | 0.2631 | 0.7925 | 0.0000 | |

| TP | -291 | -3.0350 | 0.0024 | -7.1430 | |

| S6 | ONR | 113 | 1.1813 | 0.2375 | 0.0455 |

| DER | -85 | -0.8850 | 0.3761 | -0.0345 | |

| Length | -139 | -1.4516 | 0.1466 | -0.0714 | |

| TP | -305 | -3.1815 | 0.0015 | -6.3498 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).