Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Preparation of Activated Carbon Support

2.3. Preparation of Composite Mixture (FeCr/AC)

2.4. Characterization Techniques

2.5. Process for Photo-Fenton Degradation Experiment

3. Results

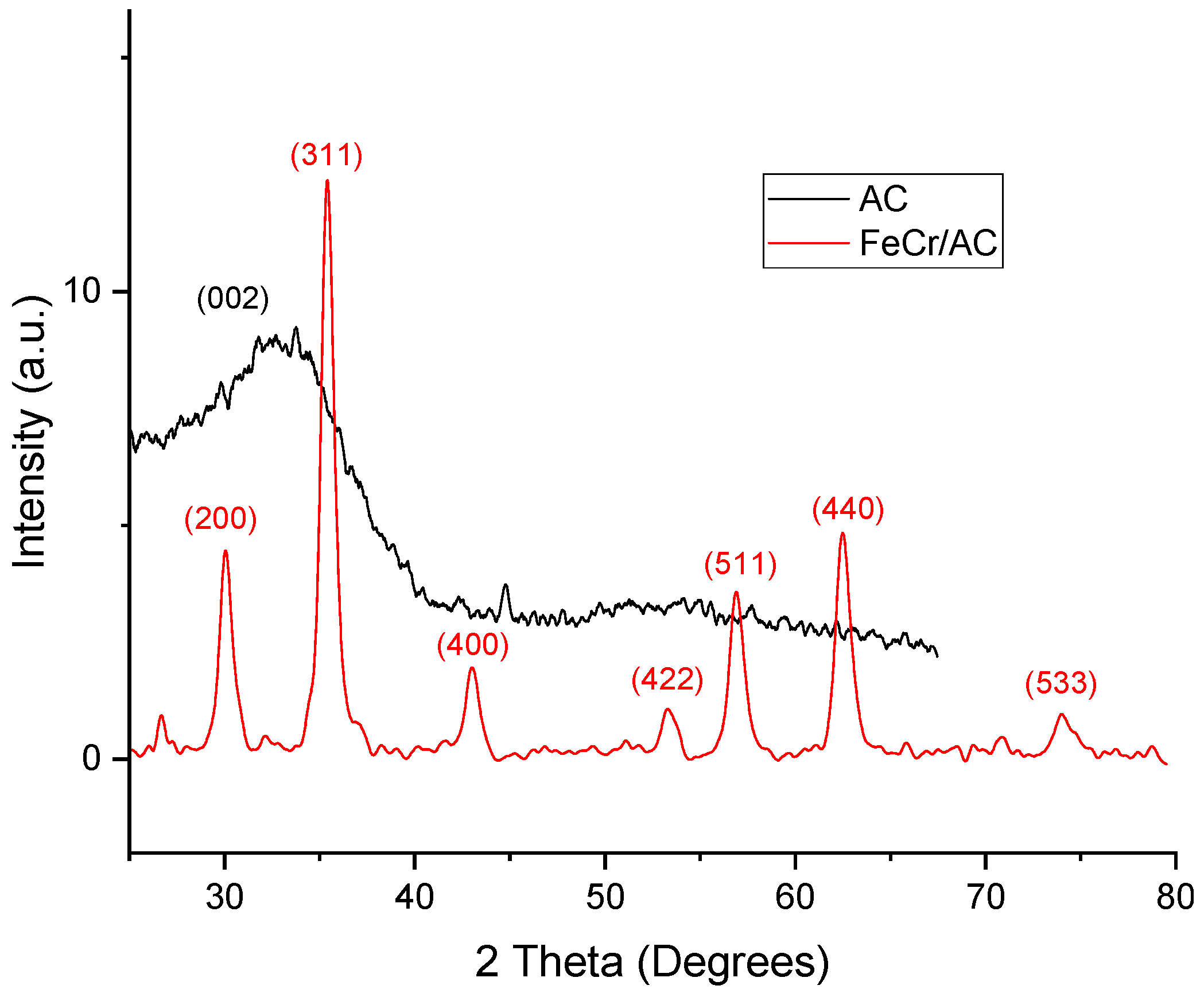

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

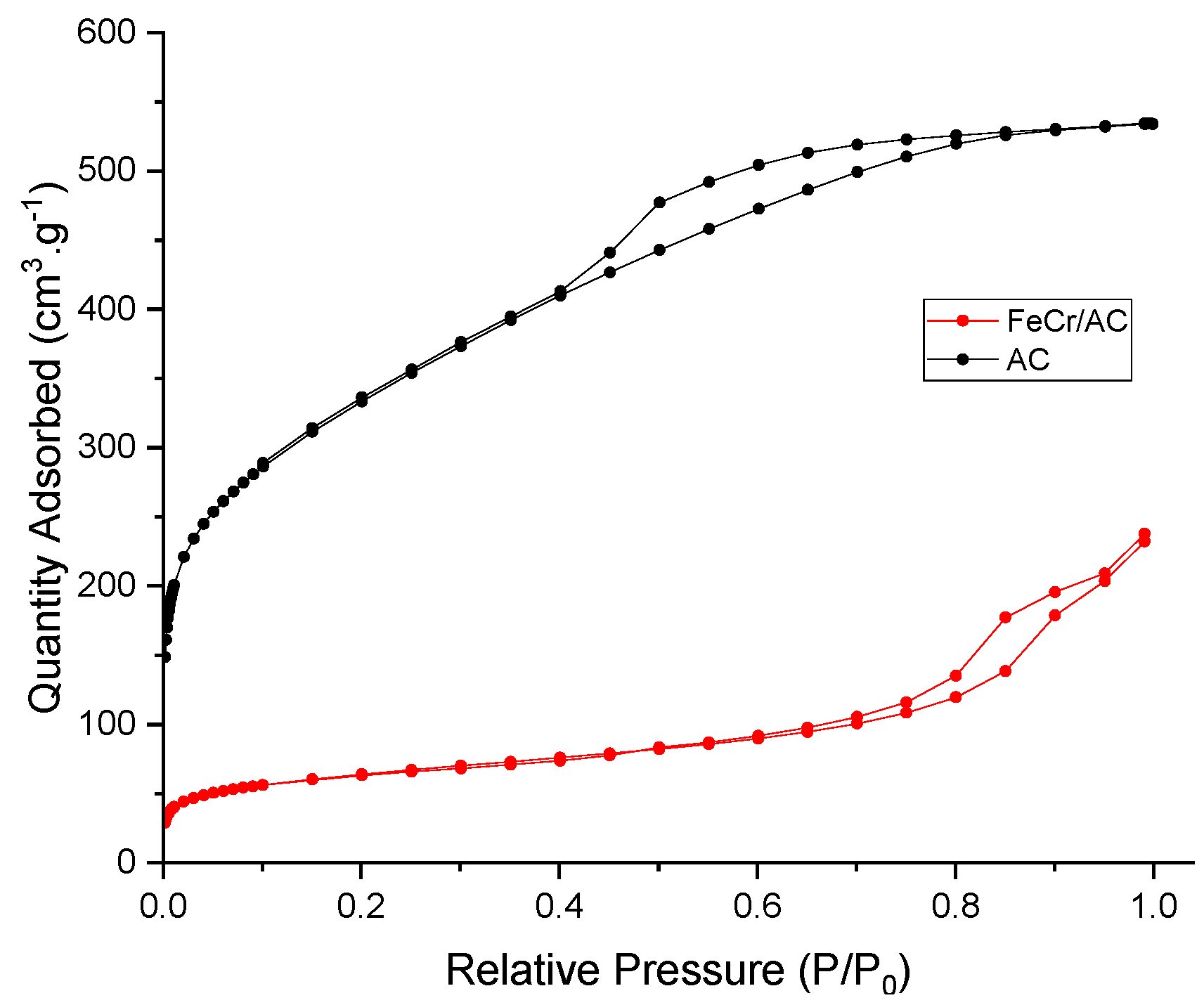

3.2. Brunaeur-Emmet-Teller (BET)

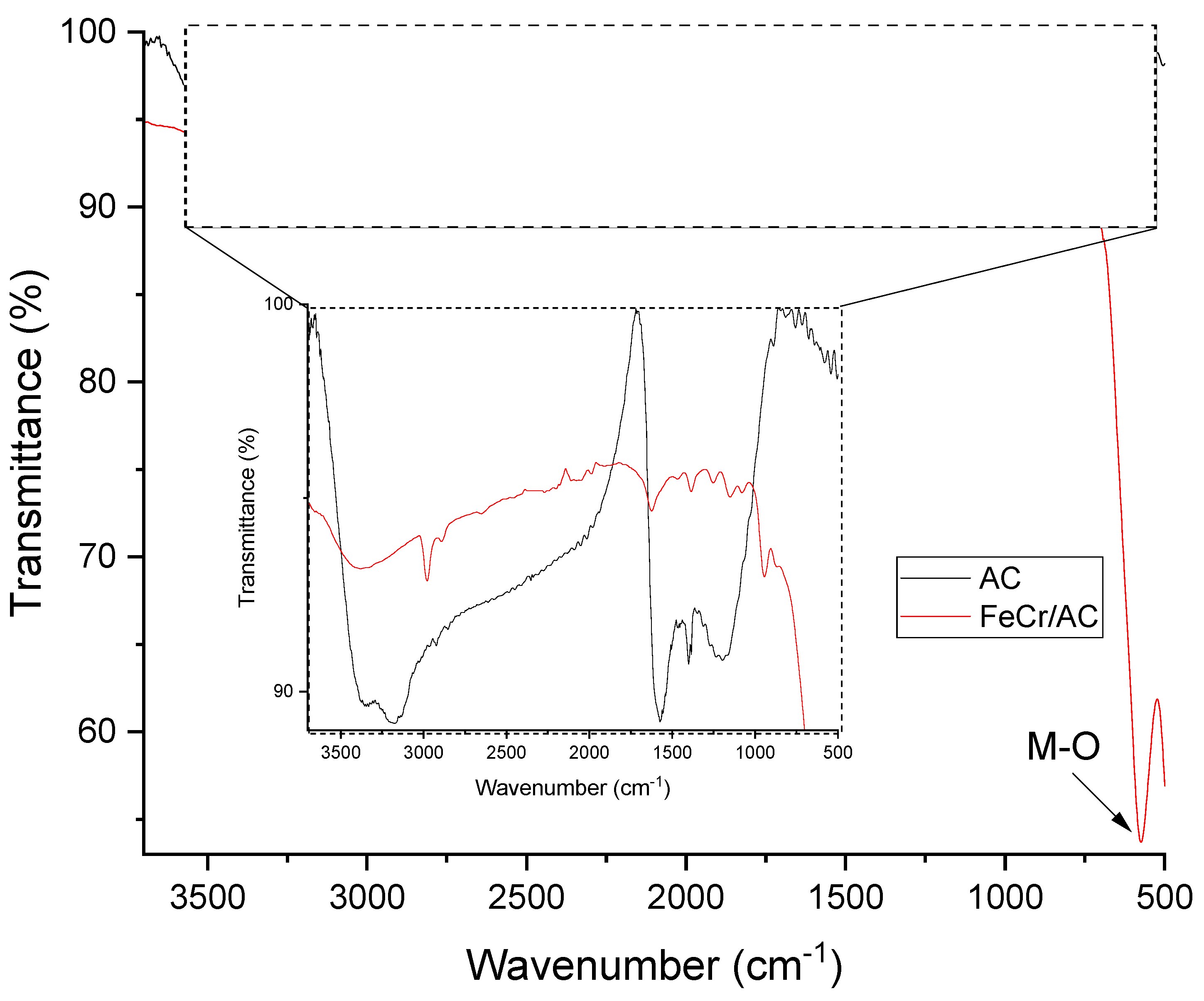

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

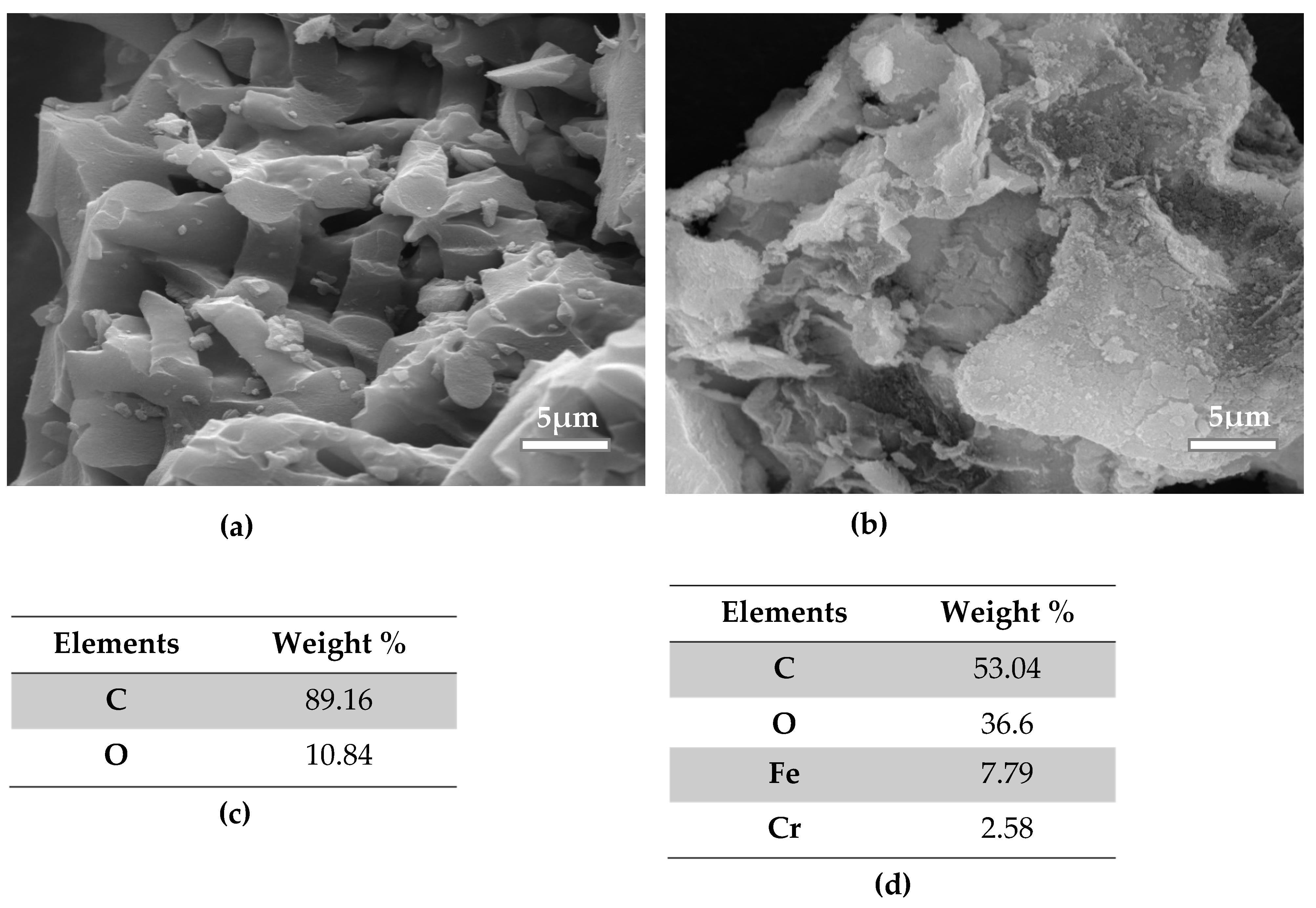

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

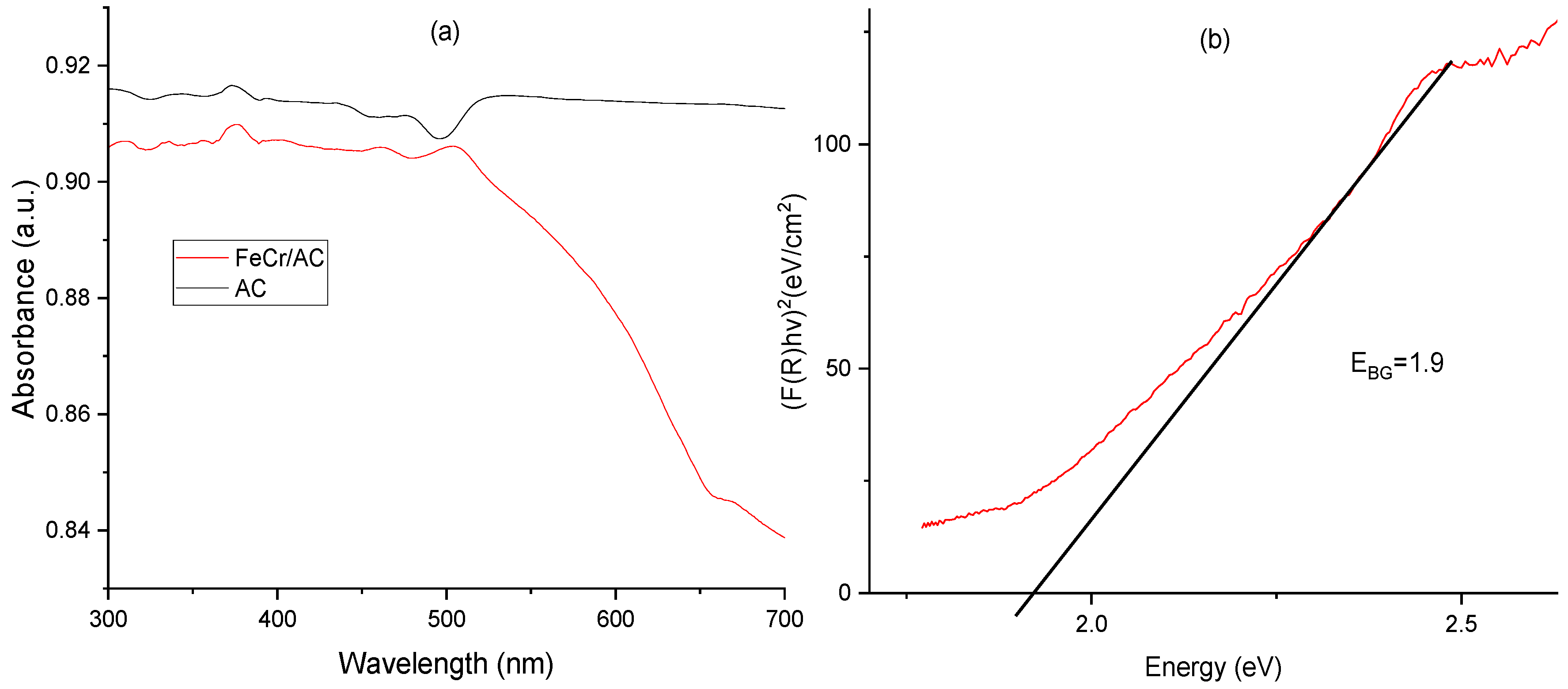

3.5. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

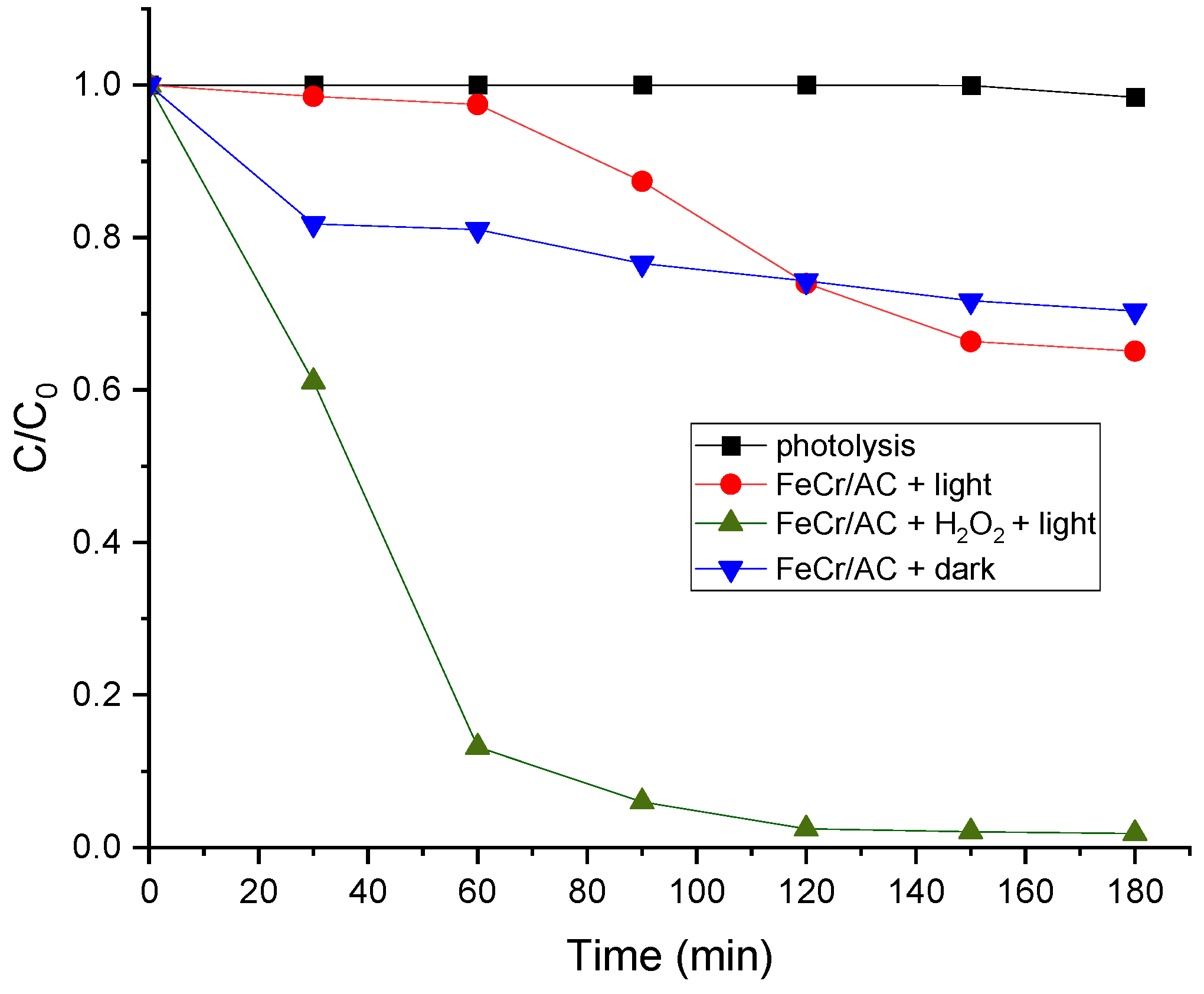

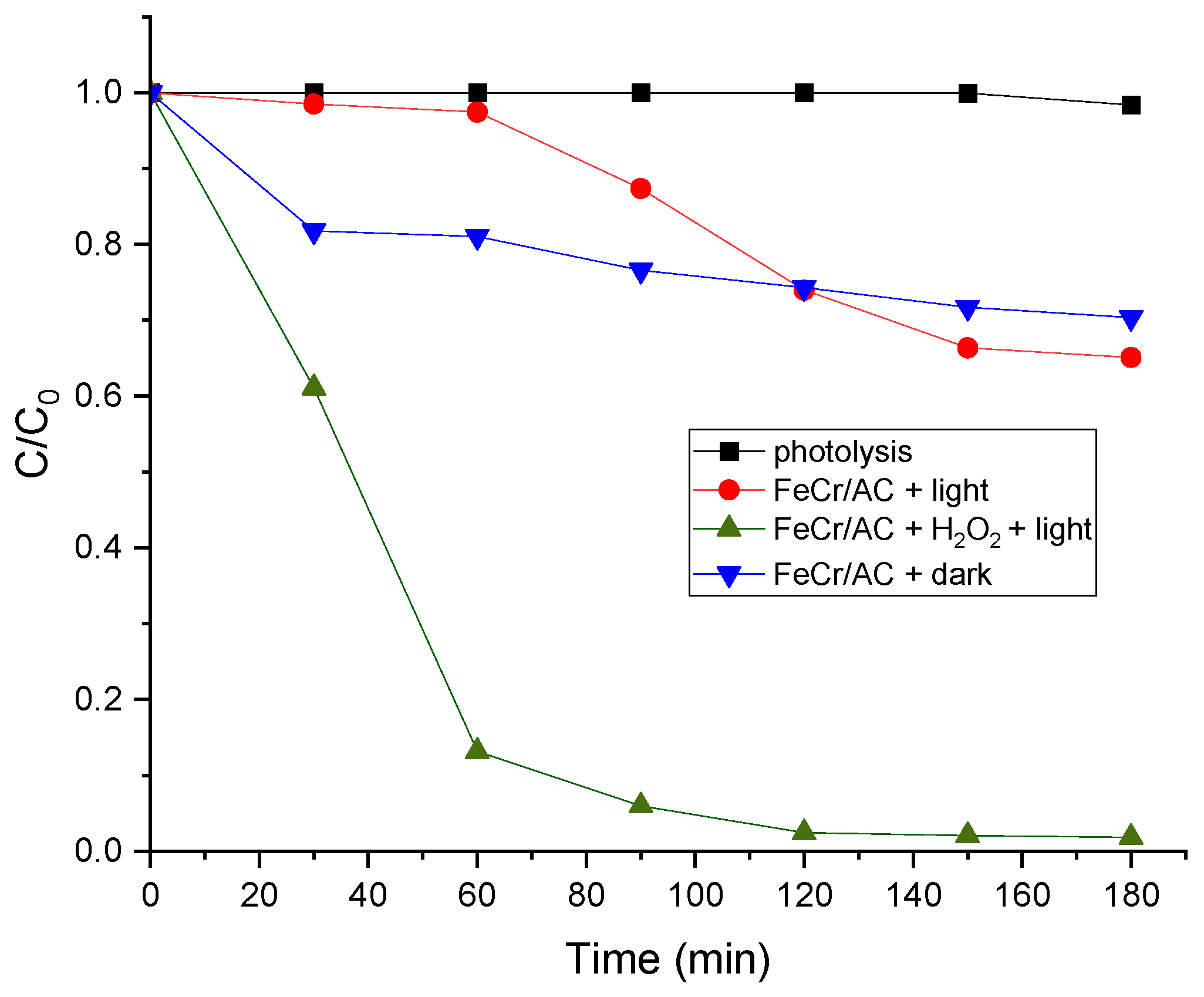

3.6. Photo-Fenton Catalytic Activity of FeCr/AC

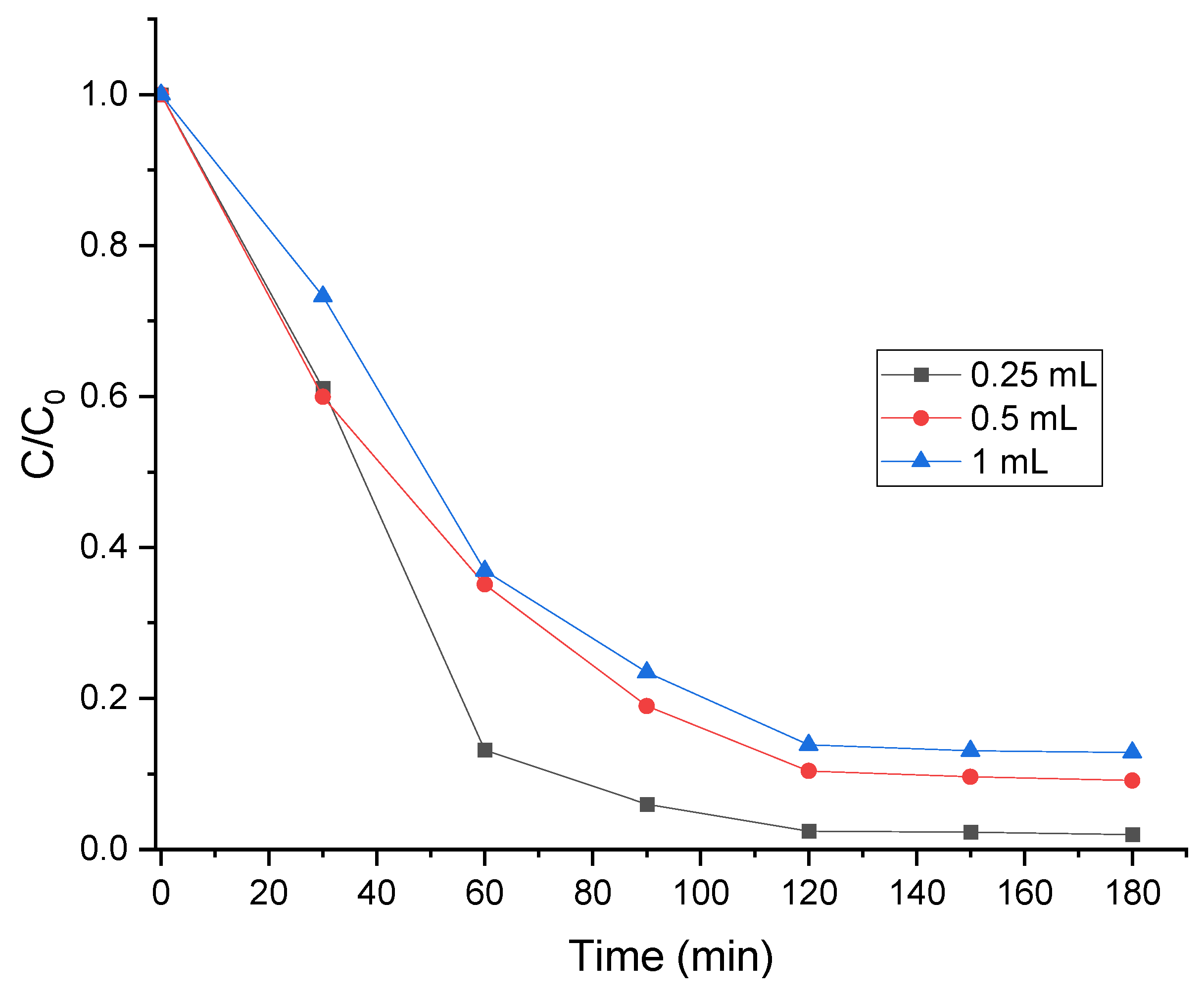

3.7. Impact of Catalyst Amount on MB Degradation

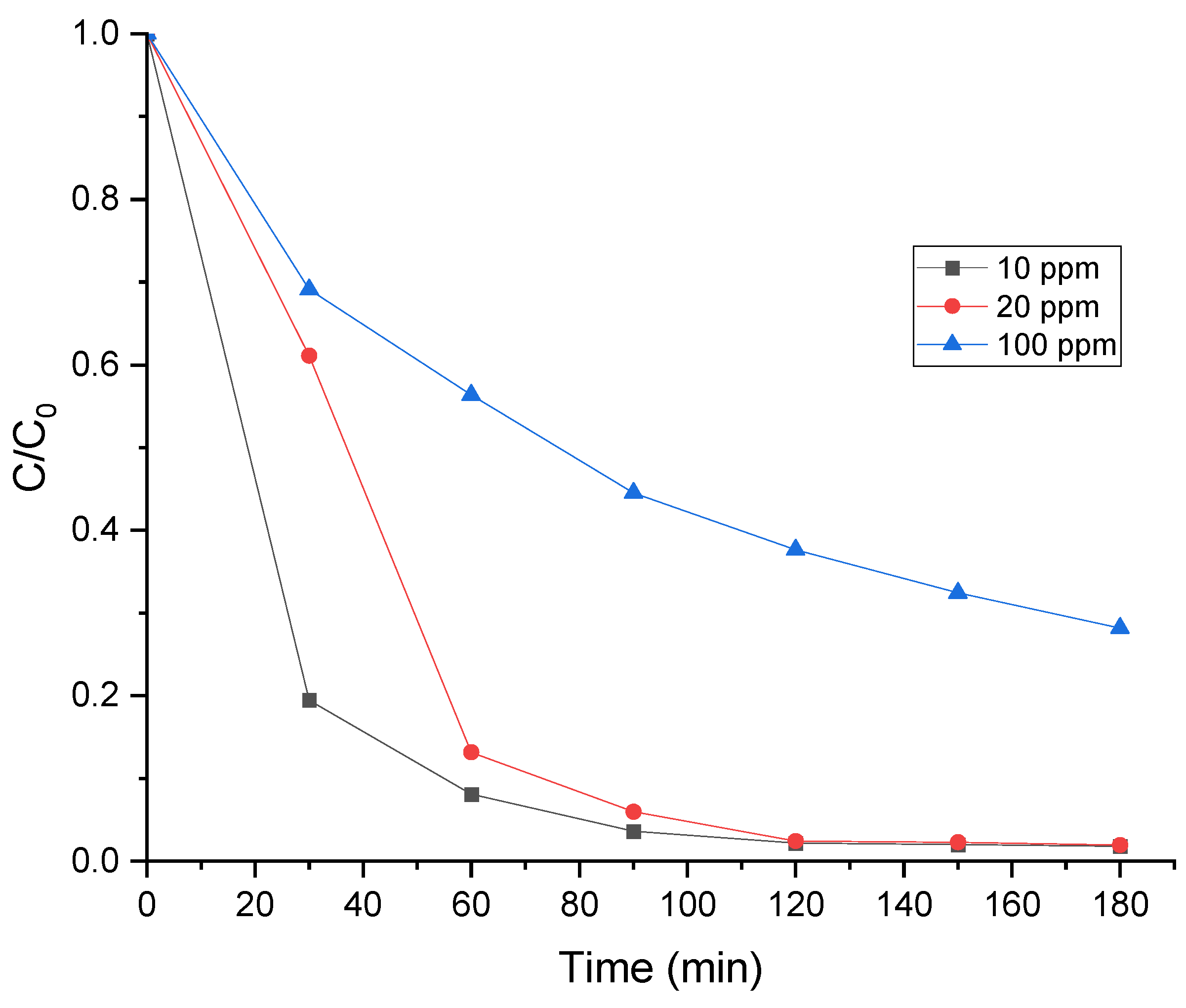

3.8. Impact of Initial MB Concentration

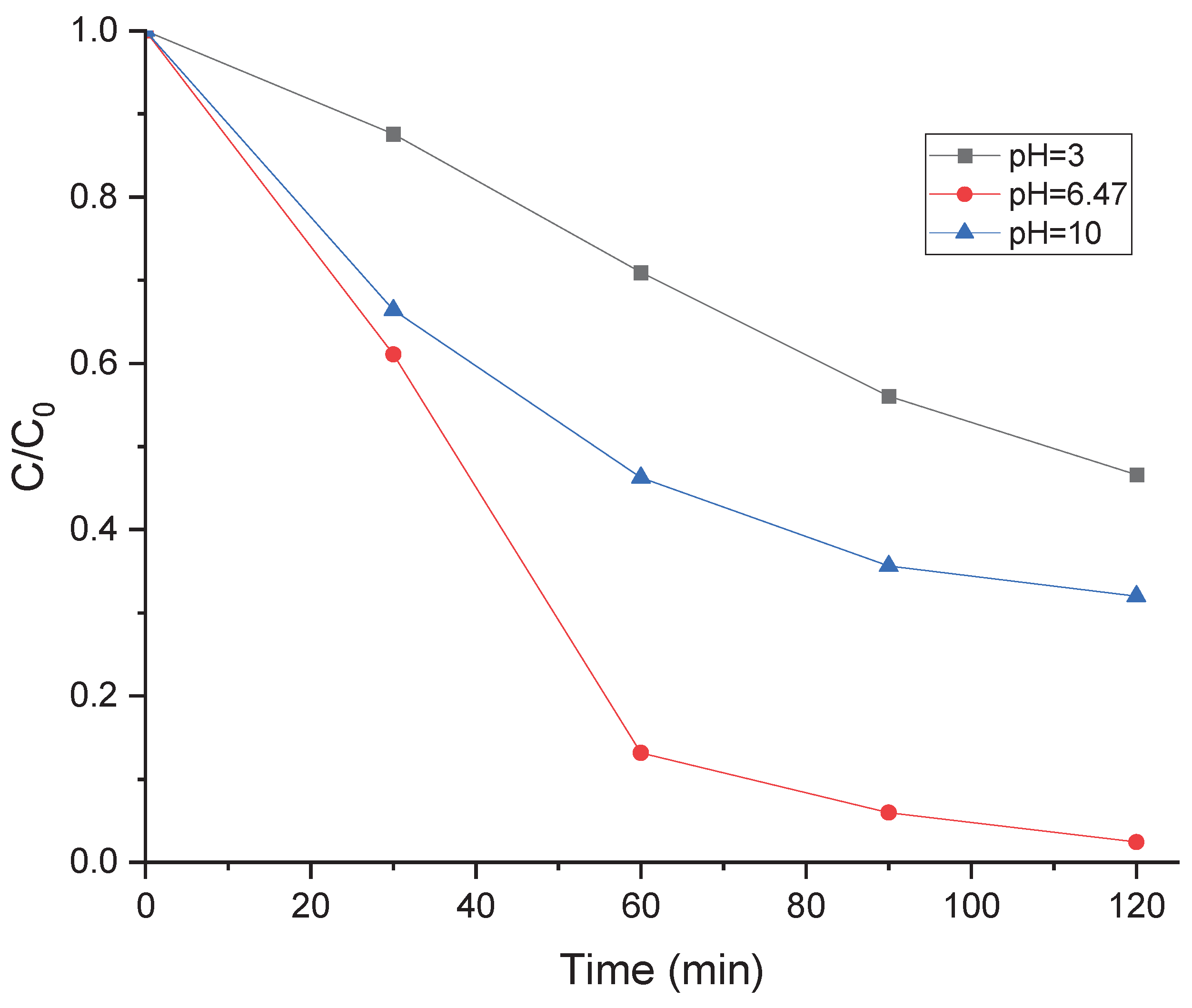

3.9. Impact of Initial pH

3.10. Impact of Oxidant Dosage on MB Degradation

3.11. Kinetic Study of MB

3.12. FeCr/AC Recyclability and Leaching Test

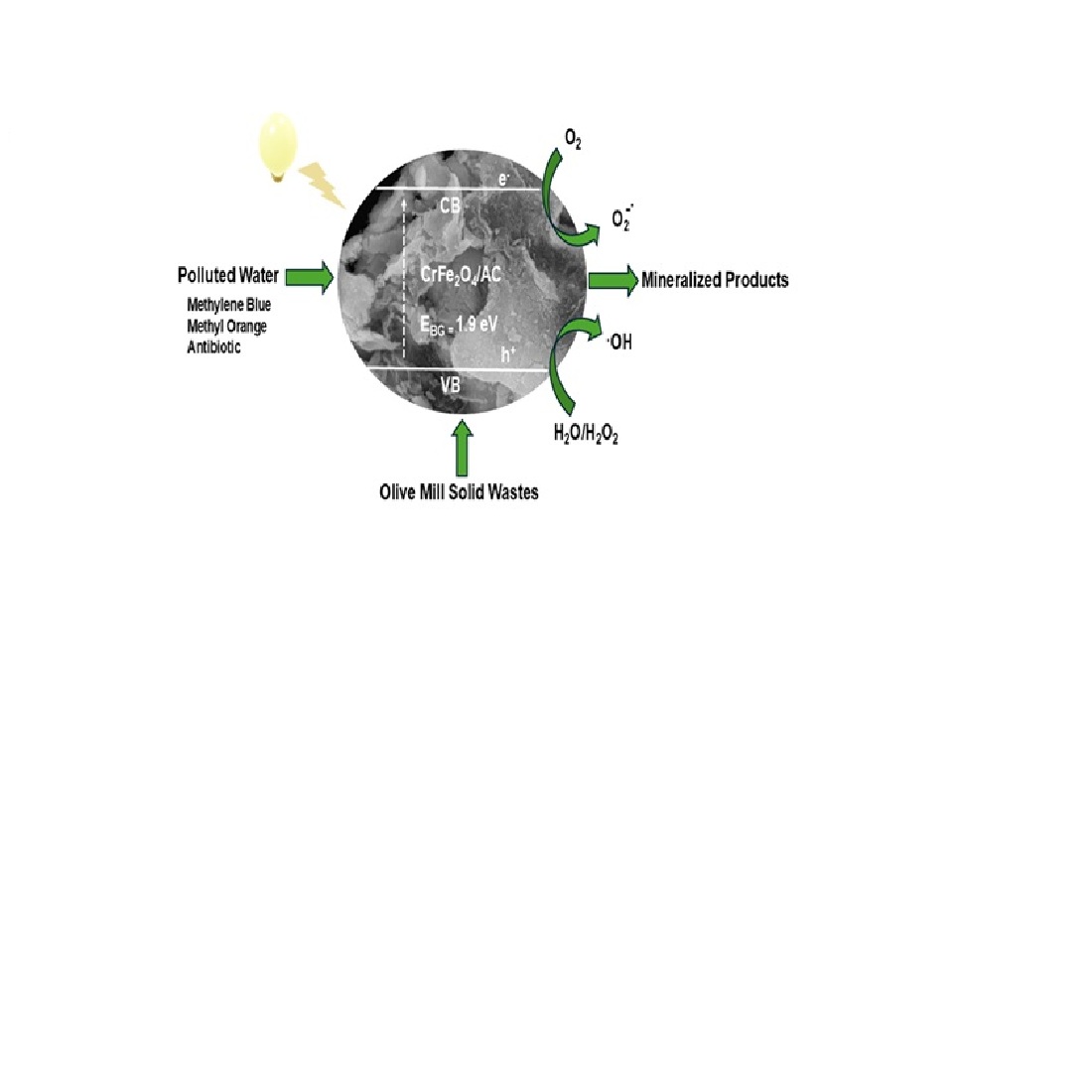

3.13. Possible Mechanism for MB Degradation by FeCr/AC

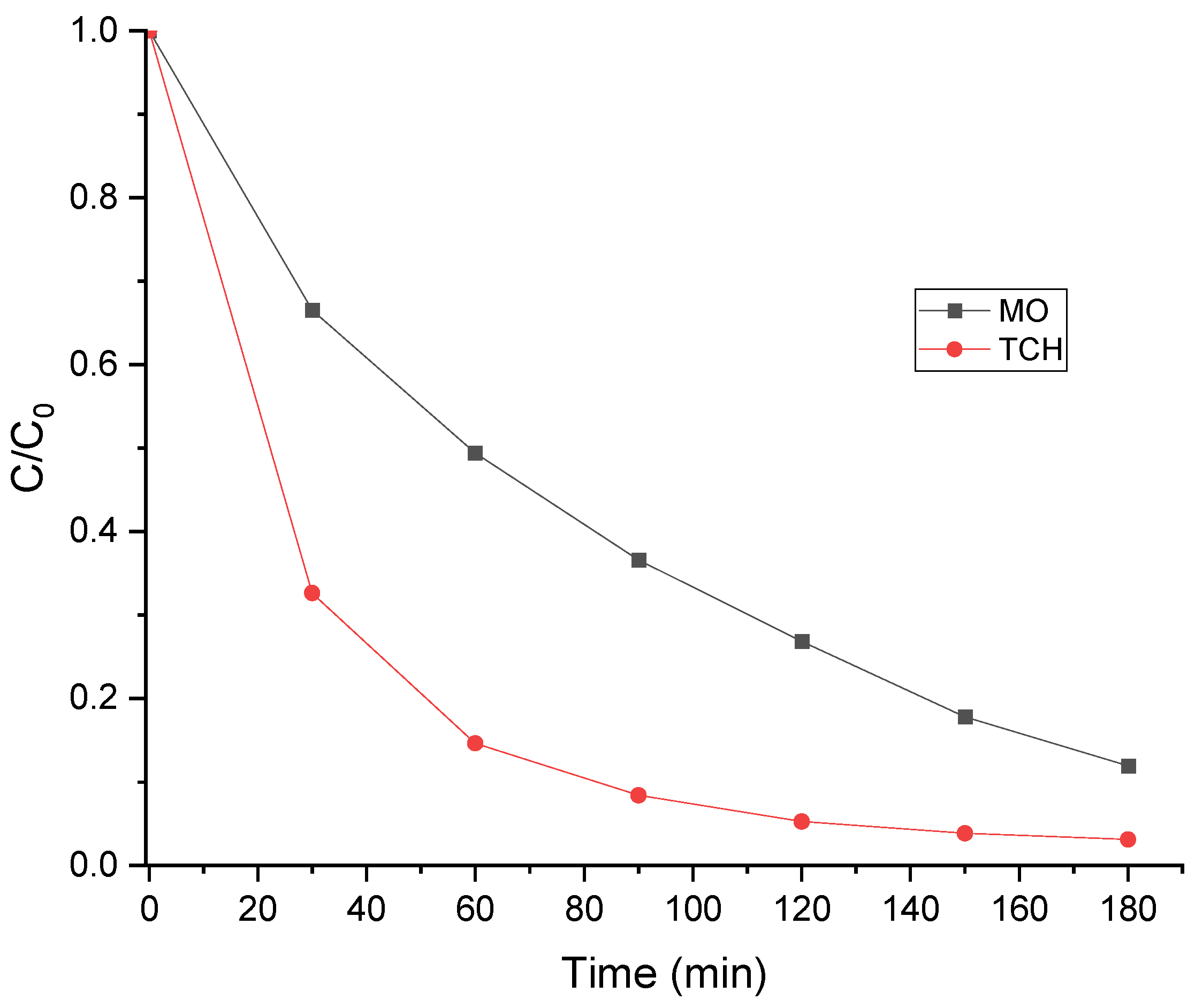

3.14. Degradation of MO and TCH

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Economic Forum (2020). 5 lessons for the future of water. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/covid-19-water-what-can-we-learn/ (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

- Zulfiqar M., Samsudin M. F. R., and Sufian S., “Modelling and optimization of photocatalytic degradation of phenol via TiO2 nanoparticles: An insight into response surface methodology and artificial neural network,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem., 2019, 384, 112039. [CrossRef]

- Pavithra K. G., Kumar P. S., Jaikumar V., and Rajan P. S., “Removal of colorants from wastewater : A review on sources and treatment strategies,” J. Ind. Eng. Chem., 2019, 75, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Vanhulle, S., Trovaslet, M., Enaud, E., Lucas, M., Taghavi, S., Van der Lelie, D., Van Aken, B., Foret, M., Onderwater, R. C. A., Wesenberg, D., Agathos, S. N., Schneider, Y.-J., and Corbisier, A.-M., “Genotoxicity Reduction During a Combined Ozonation / Fungal Treatment of Dye-Contaminated Wastewater,” Env. Sci Technol, 2008, 42, 584–589. [CrossRef]

- Das T. R., Patra S., Madhuri R., and Sharma P. K., “Bismuth oxide decorated graphene oxide nanocomposites synthesized via sonochemical assisted hydrothermal method for adsorption of cationic organic dyes,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2018, 509, 82–93. [CrossRef]

- Hafiz M., Hassanein A., Talhami M., Al-Ejji M., Hassan M. K., and Hawari A. H., “Magnetic nanoparticles draw solution for forward osmosis: Current status and future challenges in wastewater treatment,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2022, 10(6), 108955. [CrossRef]

- Aslan S. and Şirazi M., “Adsorption of Sulfonamide Antibiotic onto Activated Carbon Prepared from an Agro-industrial By-Product as Low-Cost Adsorbent: Equilibrium, Thermodynamic, and Kinetic Studies,” Water, Air, Soil Pollut., 2020, 231(5), 222. [CrossRef]

- Omri A., Wali A., and Benzina M., “Adsorption of bentazon on activated carbon prepared from Lawsonia inermis wood: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies,” Arab. J. Chem., 2016, 9, 1729–S1739. [CrossRef]

- Rosal, R., Rodríguez, A., Perdigón-Melón, J. A., Petre, A., García-Calvo, E., Gómez, M. J., Agüera, A., and Fernández-Alba, A. R., “Occurrence of emerging pollutants in urban wastewater and their removal through biological treatment followed by ozonation,” Water Res., 2010, 44(2), 578–588. [CrossRef]

- Ali, T., Tripathi, P., Azam, A., Raza, W., Ahmed, A. S., Ahmed, A., and Muneer, M., “Photocatalytic performance of Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under visible-light irradiation,” Mater. Res. Express, 2017, 4(1), 15022. [CrossRef]

- Karthik, C., Swathi, N., Pandi Prabha, S., and Caroline, D. G., “Green synthesized rGO-AgNP hybrid nanocomposite – An effective antibacterial adsorbent for photocatalytic removal of DB-14 dye from aqueous solution,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2020, 8(1), 103577. [CrossRef]

- McMullan, G., Meehan, C., Conneely, A., Kirby, N., Robinson, T., Nigam, P., Banat, I. M., Marchant, R., and Smyth, W. F., “Microbial decolourisation and degradation of textile dyes,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2001, 56(1–2), 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Emamjomeh M. M. and Sivakumar M., “Review of pollutants removed by electrocoagulation and electrocoagulation/flotation processes,” J. Environ. Manage., 2009, 90(5), 1663–1679. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle C. A., Rodrigo M. A., Sirés I., and Scialdone O., “Single and Coupled Electrochemical Processes and Reactors for the Abatement of Organic Water Pollutants: A Critical Review,” Chem. Rev., 2015, 115(24), 13362–13407. [CrossRef]

- Momina and Ahmad K., “Feasibility of the adsorption as a process for its large scale adoption across industries for the treatment of wastewater: Research gaps and economic assessment,” J. Clean. Prod., 2023, 388, 136014. [CrossRef]

- Kim S.-H., Kim D.-S., Moradi H., Chang Y.-Y., and Yang J.-K., “Highly porous biobased graphene-like carbon adsorbent for dye removal: Preparation, adsorption mechanisms and optimization,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2023, 11(2), 109278. [CrossRef]

- Dhamorikar, V. G. Lade, P. V Kewalramani, and A. B. Bindwal, “Review on integrated advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment,” J. Ind. Eng. Chem., 2024, 138, 104–122. [CrossRef]

- Sirés I., Brillas E., Oturan M. A., Rodrigo M. A., and Panizza M., “Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: Today and tomorrow. A review,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 2014, 21(14), 8336–8367. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S., Rasul M. G., Brown R., and Hashib M. A., “Influence of parameters on the heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of pesticides and phenolic contaminants in wastewater: A short review,” J. Environ. Manage., 2011, 92(3), 311–330. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B., Li, H., Li, X., Liu, X., Zhang, C., Xu, H., and Zhao, X. S.., “Degradation of Organic Dyes over Fenton-Like Cu2O-Cu/C Catalysts,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2018, 57(42), 14011–14021. [CrossRef]

- Susanti Y. D.and Saleh R., “Efficient photo-, sono-, and sonophoto-fenton-like degradation of the organic pollutant methylene blue using a BiFeO3/graphene composite,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., 2020, 763(1). [CrossRef]

- Vaishnave P., Ameta G., Kumara A., Sharma S., and Ameta S. C., “Sono-photo-Fenton and photo-Fenton degradation of methylene blue: A comparative study,” J. Indian Chem. Soc., 2011, 88(3), 397–403, doi:.

- Halfadji A., Naous M., Kharroubi K. N., Belmehdi F. E. Z., and Aoudia H., “Facile prepared Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a nano-catalyst on photo-fenton process to remediation of methylene blue dye from water: characterisation and optimization,” Glob. Nest J., 2024, 26(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Zhu, R., Yan, L., Fu, H., Xi, Y., Zhou, H., Zhu, G., Zhu, J., and He, H., “Visible-light Ag/AgBr/ferrihydrite catalyst with enhanced heterogeneous photo-Fenton reactivity via electron transfer from Ag/AgBr to ferrihydrite,” Appl. Catal. B Environ., 2018, 239, 280–289. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Gao, J., Li, T., Chen, Y., Wu, Q., Xie, T., Lin, Y., and Dong, S., “Visible-light-driven photo-Fenton reaction with α-Fe2O3/BiOI at near neutral pH: Boosted photogenerated charge separation, optimum operating parameters and mechanism insight,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2019, 554, 531–543. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Y., Yaakob Z., and Akhtar P., “Degradation and mineralization of methylene blue using a heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalyst under visible and solar light irradiation,” Catal. Sci. Technol., 2016, 6(4), 1222–1232. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhou, C., Yuan, Y., Jin, Y., Liu, Y., Jiang, Z., Li, X., Dai, J., Zhang, Y., Siyal, A. A., Ao, W., Fu, J., and Qu, J., “Catalytic degradation of crystal violet and methyl orange in heterogeneous Fenton-like processes,” Chemosphere, 2023, 344, 140406. [CrossRef]

- Tryba B., Piszcz M., Grzmil B., Pattek-Janczyk A., and Morawski A. W., “Photodecomposition of dyes on Fe-C-TiO2 photocatalysts under UV radiation supported by photo-Fenton process,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 162(1), 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Liu S.-Q., Feng L.-R., Xu N., Chen Z.-G., and. Wang X.-M,, “Magnetic nickel ferrite as a heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalyst for the degradation of rhodamine B in the presence of oxalic acid,” Chem. Eng. J., 2012, 203, 432–439. [CrossRef]

- Diao Y., Yan Z., Guo M., and Wang X., “Magnetic multi-metal co-doped magnesium ferrite nanoparticles: An efficient visible light-assisted heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst synthesized from saprolite laterite ore,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2018, 344, 829–838, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.11.029.

- Anchieta, C. G., Severo, E. C., Rigo, C., Mazutti, M. A., Kuhn, R. C., Muller, E. I., Flores, E. M. M., Moreira, R. F. P. M., and Foletto, E. L.., “Rapid and facile preparation of zinc ferrite (ZnFe2O4) oxide by microwave-solvothermal technique and its catalytic activity in heterogeneous photo-Fenton reaction,” Mater. Chem. Phys., 2015, 160, 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Firouzeh N., Paseban A., Ghorbanian M., Asadzadeh S. N., and Amani A., “Recyclable Nano-Magnetic CoFe2O4: a Photo-Fenton Catalyst for Efficient Degradation of Reactive Blue 19,” Bionanoscience, 2024, 14(4), 4481–4492. [CrossRef]

- Fahad Almojil S., Ning J., and Ibrahim Almohana A., “Photo-Fenton process for degradation of methylene blue using copper ferrite@sepiolite clay,” Inorg. Chem. Commun., 2024, 166, 12623. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L., Wang, Z., Fu, Y., Lai, C., Liu, X., Li, B., Liu, S., Yi, H., Li, L., Zhang, M., Li, Z., Cao, W., and Niu, Q. “Gold nanoparticles-modified MnFe2O4 with synergistic catalysis for photo-Fenton degradation of tetracycline under neutral pH,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2021, 414, 125448. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav S. A., Somvanshi S. B., Khedkar M. V, Patade S. R., and Jadhav K. M., “Magneto-structural and photocatalytic behavior of mixed Ni–Zn nano-spinel ferrites: visible light-enabled active photodegradation of rhodamine B,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., 2020, 31(14), 11352–11365. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça M. H., Godinho M. I.,. Catarino M. A, da Silva Pereira M. I., and Costa F. M., “Preparation and characterisation of spinel oxide ferrites suitable for oxygen evolution anodes,” Solid State Sci., 2002, 4(2), 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Valente, F., Astolfi, L., Simoni, E., Danti, S., Franceschini, V., Chicca, M., and Martini, A. “Nanoparticle drug delivery systems for inner ear therapy: An overview,” J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol., 2017, 39, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Casbeer E., Sharma V. K., and. Li X. Z, “Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of ferrites under visible light: A review,” Sep. Purif. Technol., 2012, 87, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Ji, L., Ma, P.-C., Shao, Y., Zhang, H., Gao, W., and Li, Y., “Development of carbon nanotubes/CoFe2O4 magnetic hybrid material for removal of tetrabromobisphenol A and Pb(II),” J. Hazard. Mater., 2014, 265, 104–114. [CrossRef]

- Rooygar A. A.,. Mallah M. H, Abolghasemi H., and Safdari J., “New ‘magmolecular’ process for the separation of antimony(III) from aqueous solution,” J. Chem. Eng. Data, 2014, 59(11), 3545–3554. [CrossRef]

- Goswami M. and Phukan P., “Enhanced adsorption of cationic dyes using sulfonic acid modified activated carbon,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2017, 5(4), 3508–3517. [CrossRef]

- Zabihi M., Khorasheh F., and Shayegan J., “Supported copper and cobalt oxides on activated carbon for simultaneous oxidation of toluene and cyclohexane in air,” RSC Adv., 2015, 5(7), 5107–5122. [CrossRef]

- Bouriche R., Tazibet S., Boutillara Y., Melouki R., Benaliouche F., and Boucheffa Y., “Characterization of Titanium (IV) Oxide Nanoparticles Loaded onto Activated Carbon for the Adsorption of Nitrogen Oxides Produced from the Degradation of Nitrocellulose,” Anal. Lett., 2021, 54(12), 1929–1942. [CrossRef]

- Qadri S., Ganoe A., and Haik Y., “Removal and recovery of acridine orange from solutions by use of magnetic nanoparticles,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 169(1–3), 318–323. [CrossRef]

- Vasileiadou A., Zoras S., and Iordanidis A., “Bioenergy production from olive oil mill solid wastes and their blends with lignite: thermal characterization, kinetics, thermodynamic analysis, and several scenarios for sustainable practices,” Biomass Convers. Biorefinery, 2023, 13(6), 5325–5338. [CrossRef]

- Andriantsiferana C., Mohamed E. F., and Delmas H., “Photocatalytic degradation of an azo-dye on TiO2/activated carbon composite material,” Environ. Technol. (United Kingdom), 2014, 35(3), 355–363. [CrossRef]

- Yuan R., Guan R., Shen W., and Zheng J., “Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by a combination of TiO2 and activated carbon fibers,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2005, 282(1), 87–91. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S. N. U. S., Shah, A. A., Liu, W., Channa, I. A., Chandio, A. D., Chandio, I. A., and Ibupoto, Z. H., “Activated carbon based TiO2 nanocomposites (TiO2@AC) used simultaneous adsorption and photocatalytic oxidation for the efficient removal of Rhodamine-B (Rh–B),” Ceram. Int., 2024, 50(21), 41285–41298. [CrossRef]

- Thirumoolan, D., Ragupathy, S., Renukadevi, S., Rajkumar, P., Rai, R. S., Saravana Kumar, R. M., Hasan, I., Durai, M., and Ahn, Y.-H. “Influence of nickel doping and cotton stalk activated carbon loading on structural, optical, and photocatalytic properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem., 2024, 448, 115300. [CrossRef]

- Tabaja, N., Brouri, D., Casale, S., Zein, S., Jaafar, M., Selmane, M., Toufaily, J., Davidson, A., and Hamieh, T., “Use of SBA-15 silica grains for engineering mixtures of oxides CoFe and NiFe for Advanced Oxidation Reactions under visible and NIR,” Appl. Catal. B Environ., 2019, 253, 69–378. [CrossRef]

- Tabaja, N., Casale, S., Brouri, D., Davidson, A., Obeid, H., Toufaily, J., and Hamieh, T., “Quantum-dots containing Fe/SBA-15 silica as green catalysts for the selective photocatalytic oxidation of alcohol (methanol, under visible light),” Comptes rendus-Chim., 2015,18(3), 358–367. [CrossRef]

- Imraish, A., Abu Thiab, T., Al-Awaida, W., Al-Ameer, H. J., Bustanji, Y., Hammad, H., Alsharif, M., ad Al-Hunaiti A., “In vitro anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of ZnFe2O4 and CrFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized using Boswellia carteri resin,” J. Food Biochem., 2021, 45(6), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-X., Zhou, Y.-R., Wang, M., Zhang, Q., Ji, T., Chen, T.-Y., & Yu, D.-C., “Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution onto viscose-based activated carbon fiber felts: Kinetics and equilibrium studies,” Adsorpt. Sci. Technol., 2019, 37( 3–4), 312–332. [CrossRef]

- Liu P., Huang Y., and Zhang X., “Enhanced electromagnetic absorption properties of reduced graphene oxide-polypyrrole with NiFe2O4 particles prepared with simple hydrothermal method,” Mater. Lett., 2014, 120, 143–146. [CrossRef]

- Parishani M., Nadafan M., Dehghani Z., Malekfar R., and Khorrami G. H. H., “Optical and dielectric properties of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles under different synthesized temperature,” Results Phys., 2017, 7, 3619–3623. [CrossRef]

- Luadthong C., Itthibenchapong V., Viriya-Empikul N., Faungnawakij K., Pavasant P., and Tanthapanichakoon W., “Synthesis, structural characterization, and magnetic property of nanostructured ferrite spinel oxides (AFe2O4, A = Co, Ni and Zn),” Mater. Chem. Phys., 2013, 143(1), 203–208. [CrossRef]

- Doğan M., Sabaz P., Bi̇ci̇l Z., Koçer Kizilduman B., and Turhan Y., “Activated carbon synthesis from tangerine peel and its use in hydrogen storage,” J. Energy Inst., 2020, 93(6), 2176–2185. [CrossRef]

- Baikousi, M., Dimos, K., Bourlinos, A. B., Zbořil, R., Papadas, I., Deligiannakis, Y., and Karakassides, M. A., “Surface decoration of carbon nanosheets with amino-functionalized organosilica nanoparticles,” Appl. Surf. Sci., 2012, 258(8), 3703–3709. [CrossRef]

- Shendrik R., Kaneva E., Radomskaya T., Sharygin I., and Marfin A., “Relationships between the structural, vibrational, and optical properties of microporous cancrinite,” Crystals, 2021, 11(3), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Makofane A., Motaung D. E., and Hintsho-Mbita N. C., “Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and sulfisoxazole from water using biosynthesized zinc ferrite nanoparticles,” Ceram. Int., 2021, 47(16), 22615–22626. [CrossRef]

- Yousif, M., Ibrahim, A. H., Al-Rawi, S. S., Majeed, A., Iqbal, M. A., Kashif, M., Abidin, Z. U., Arbaz, M., Ali, S., Hussain, S. A., Shahzadi, A., and Haider, M. T. “Visible light assisted photooxidative facile degradation of azo dyes in water using a green method,” RSC Adv., 2024, 14(23), 16138–16149. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M., Singh, J., Yashpal, M., Gupta, D. K., Mishra, R. K., Tripathi, S., and Ojha, A. K.., “Synthesis of superparamagnetic bare Fe3O4 nanostructures and core/shell (Fe3O4/alginate) nanocomposites,” Carbohydr. Polym., 2012, 89(3), 821–829. [CrossRef]

- Sriramulu M., Shukla D., and Sumathi S., “Aegle marmelos leaves extract mediated synthesis of zinc ferrite: Antibacterial activity and drug delivery,” Mater. Res. Express, 2018, 5(11), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bharathi K. K., Noor-A-Alam M., Vemuri R. S., and Ramana C. V., “Correlation between microstructure, electrical and optical properties of nanocrystalline NiFe1.925Dy 0.075O4 thin films,” RSC Adv., 2012,2(3), 941–948. [CrossRef]

- Aladdin Jasim N., Esmail Ebrahim S., and Ammar S. H., “Fabrication of ZnxMn1-xFe2O4 metal ferrites for boosted photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine-B dye,” Results Opt., 2023, 13, 00508, doi:.1016/j.rio.2023.100508.

- Toor A. T., Verma A.,. Jotshi C. K, Bajpai P. K., and Singh V., “Photocatalytic degradation of Direct Yellow 12 dye using UV/TiO2 in a shallow pond slurry reactor,” Dye. Pigment., 2006, 68(1), 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Panda N., Sahoo H., and Mohapatra S., “Decolourization of Methyl Orange using Fenton-like mesoporous Fe2O3-SiO2 composite,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2011,185(1), 359–365. [CrossRef]

- Sedlak D. L., “Factors Affecting the Yield of Oxidants from the Reaction of Nanoparticulate Zero-Valent Iron and Oxygen,” Environ. Sci. Technol., 2008, 42(4), 1262–1267. [CrossRef]

- Yu L., Chen J., Liang Z., Xu W., Chen L., and Ye D., “Degradation of phenol using Fe3O4-GO nanocomposite as a heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalyst,” Sep. Purif. Technol., 2016, 171, 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Lu J., Xing J., Chen D., Xu H., Han X., and Li D., “Enhanced photocatalytic activity of β-Ga2O3 nanowires by Au nanoparticles decoration,” J. Mater. Sci., 2019, 54(8), 6530–6541. [CrossRef]

| Sample | SBET (m2 g-1) | Vp (cm3 g-1) | Dpore (nm) | Vµp (cm3 g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure AC | 1148 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 0.055 |

| FeCr/AC | 222 | 0.32 | 9.7 | 0.025 |

| Concentrations (ppm) | k (min-1) | R2 | t1/2 (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.0297 | 0.9785 | 23.33 |

| 20 | 0.0258 | 0.9739 | 26.9 |

| 100 | 0.0077 | 0.9873 | 89.78 |

| Pollutant | First-order kinetic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| k (min-1) | R2 | t1/2 (min) | |

| MO | 0.0115 | 0.9988 | 60.27 |

| TCH | 0.0225 | 0.9731 | 30.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).