Submitted:

01 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

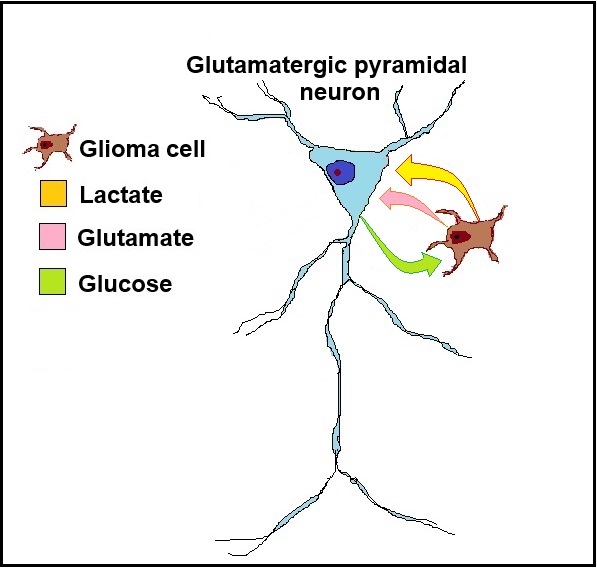

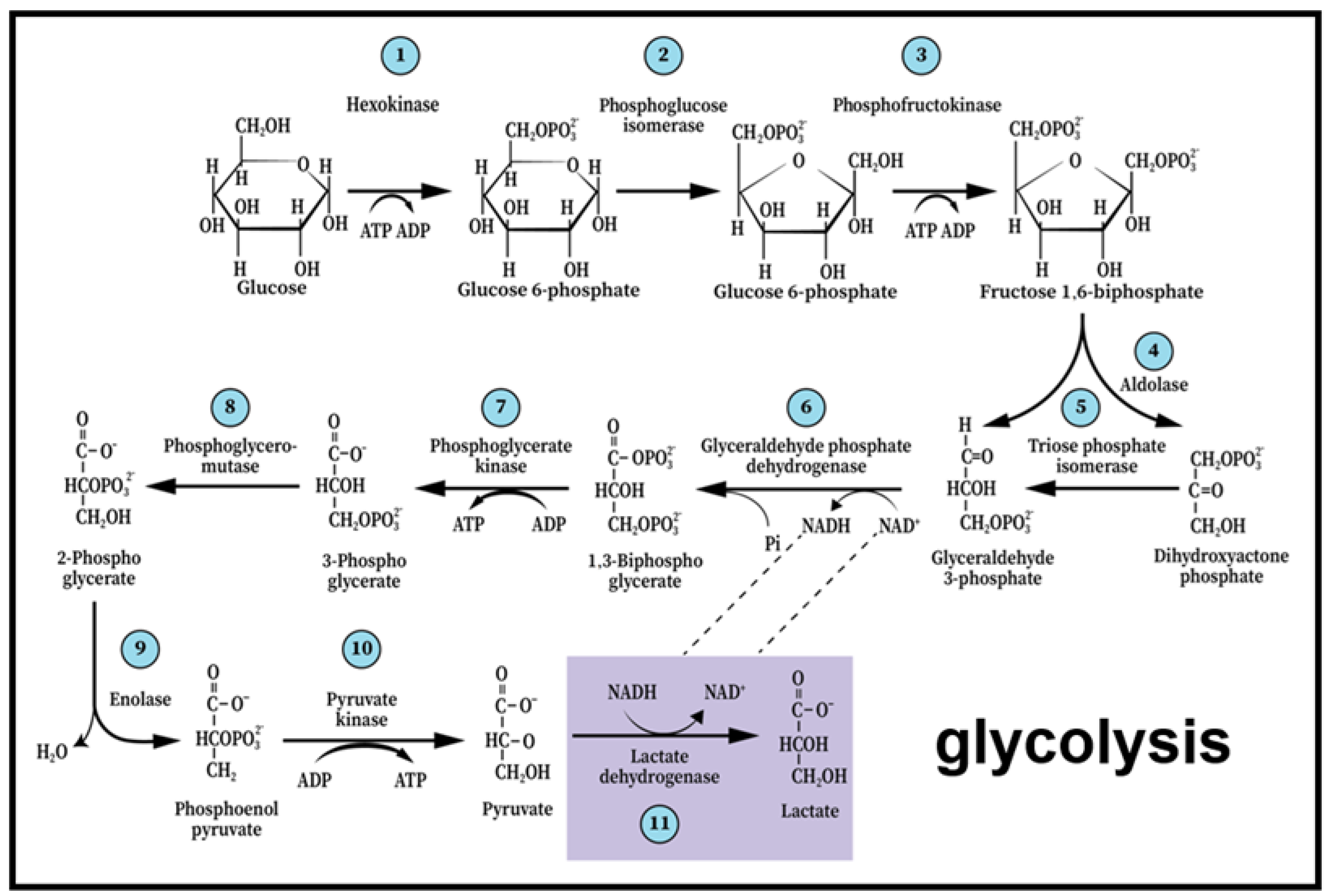

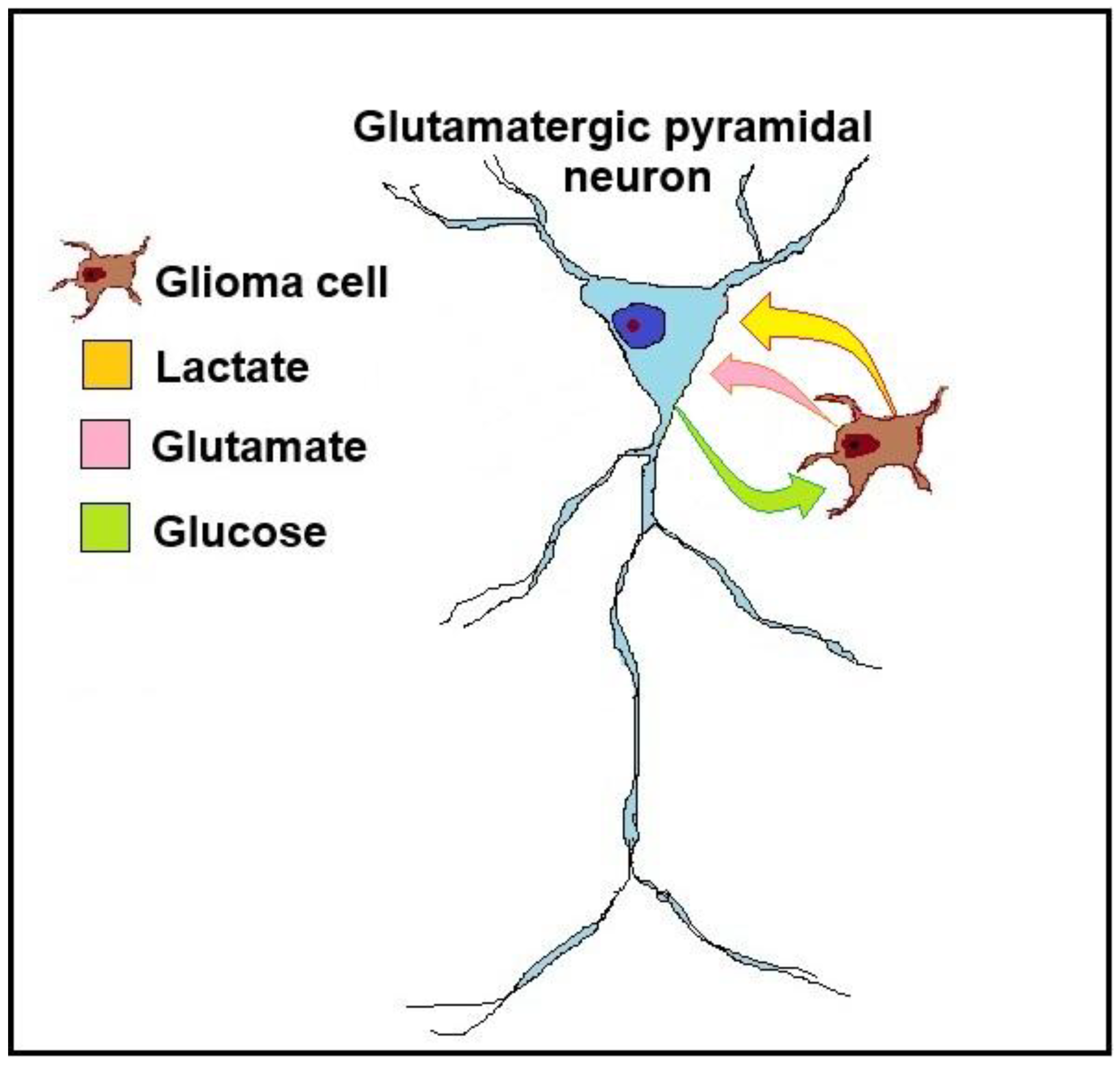

Glioma Neuron Symbiosis (GNS) Hypothesis: Exchanging Lactate for Glucose

Evolution of the Hypothesis

Testing the Hypothesis

Implications

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warburg, F. Wind, E. Negelein, The metabolism of tumors in the body. J. Gen. Physiol. 8 (1927) 519 –530. [CrossRef]

- V.A. Cuddapah, S. Robel, S. Watkins, H. Sontheimer, (2014). A neurocentric perspective on glioma invasion. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 15 (2014) 455-465. [CrossRef]

- V. Venkataramani, Y. Yang, M.C. Schubert, E. Reyhan, S.K. Tetzlaff, N. Wißmann, M. Botz, S.J. Soyka, C.A. Beretta, R.L. Pramatarov, L. Fankhauser, L.G.A. Freudenberg, J. Wagner, D.I. Tanev, M. Ratliff, R. Xie, T. Kessler, D.C. Hoffmann, L. Hai, Y. Dorflinger, S. Hoppe, Y.A. Yabo, A. Golebiewska, S.P. Niclou, F. Sahm, A. Lasorella, M. Slowik, L. Doring, A. Iavarone, W. Wick, T. Kuner, F. Winkler. Glioblastoma hijacks neuronal mechanisms for brain invasion. Cell 185 (2022) 2899–2917 . [CrossRef]

- C.B. Crivii, A.B. Boșca, C.S. Melincovici, A.M. Constantin, M. Mărginean, E. Dronca, R. Suflețel, D. Gonciar, M. Bungărdean, A. Șovrea, Glioblastoma microenvironment and cellular interactions. Cancers, 14 (2022) 1092. [CrossRef]

- S. Gillespie, M. Monje, M. An active role for neurons in glioma progression: making sense of Scherer’s structures. Neuro-oncology, 20 (2018) 1292-1299. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Brooks, Lactate: glycolytic end product and oxidative substrate during sustained exercise in mammals—the “lactate shuttle. Circulation, respiration, and metabolism: current comparative approaches. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 1985, 208-218.

- Schurr, C.A. West, B.M. Rigor, B.M. Lactate-supported synaptic function in the rat hippocampal slice preparation. Science, 1988, 240, 1326–1328. [CrossRef]

- L.B. Gladden, Lactate metabolism: a new paradigm for the third millennium. J. Physiol. 558 (2004) 5-30. [CrossRef]

- L.B. Gladden, A lactatic perspective on metabolism. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 40 (2008) 477-485. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Hall, S. Rajasekaran, T.W. Thomsen, A.R. Peterson, (2016). Lactate: friend or foe. PM&R, 8 (2016) S8-S15. [CrossRef]

- S. Passarella, L. de Bari, D. Valenti, R. Pizzuto, G. Paventi, A. Atlante, Mitochondria and L-lactate metabolism. FEBS letters, 582 (2008) 3569-3576. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, Cerebral glycolysis: a century of persistent misunderstanding and misconception. Front. Neurosci. 8 (2014) 360. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Rogatzki, B.S. Ferguson, M.L. Goodwin, L.B. Gladden, Lactate is always the end product of glycolysis. Front. Neurosci. 22 (2015) 22. [CrossRef]

- G. Van Hall, Lactate as a fuel for mitochondrial respiration. Acta Physiol. Scand. 168 (2000) 643-656. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, P.J. Magistretti, Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 91 (1994) 10625-10629. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, P.J. Magistretti, Excitatory amino acids stimulate aerobic glycolysis in astrocytes via an activation of the Na+/K+ ATPase. Dev. Neurosci. 18 (1996) 336–342. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, Lactate as a pivotal element in neuron-glia metabolic cooperation. Neurochem. Intern. 43 (2003) 331-338. [CrossRef]

- J. Handy, Lactate—the bad boy of metabolism, or simply misunderstood? Current Anaesth. & Crit Care 17 (2006) 71-76. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, P.J. Magistretti, Sweet sixteen for ANLS. J. Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 32 (2012) 1152-1166. [CrossRef]

- S. Passarella, L. de Bari, D. Valenti, R. Pizzuto, G. Paventi, A. Atlante, Mitochondria and L-lactate metabolism. FEBS letters, 582 (2008) 3569-3576. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, Cerebral glycolysis: a century of persistent misunderstanding and misconception. Front. Neurosci. 8 (2014) 360. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Rogatzki, B.S. Ferguson, M.L. Goodwin, L.B. Gladden, Lactate is always the end product of glycolysis. Front. Neurosci. 22 (2015) 22. [CrossRef]

- G. Van Hall, Lactate as a fuel for mitochondrial respiration. Acta Physiol. Scand. 168 (2000) 643-656. [CrossRef]

- M. Nalbandian, M. Takeda, Lactate as a signaling molecule that regulates exercise-induced adaptations.” Biology, 5 (2016) 38. [CrossRef]

- B.S. Ferguson, M.J. Rogatzki, M.L. Goodwin, D.A. Kane, Z. Rightmire, L.B. Gladden, Lactate metabolism: historical context, prior misinterpretations, and current understanding. Euro J. Appl. Physiol. 118 (2018) 691-728. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, R.S. Payne, J.J. Miller, B.M. Rigor, Glia are the main source of lactate utilized by neurons for recovery of function posthypoxia. Brain Res. 774 (1997) 221-224. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, Glycolysis Paradigm Shift Dictates a Reevaluation of Glucose and Oxygen Metabolic Rates of Activated Neural Tissue. Front. Neurosci. 12 (2018) 700. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, Lactate: the ultimate cerebral oxidative energy substrate? J. Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 26 (2006) 142-152. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, Lactate: a major and crucial player in normal function of both muscle and brain. J. Physiol, 586 (2008) 2665. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, From rags to riches: Lactate ascension as a pivotal metabolite in neuroenergetics. Front. Neurosci. 17 (2023) 1145358. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, How the ‘Aerobic/Anaerobic Glycolysis’ Meme Formed a ‘Habit of Mind’ Which Impedes Progress in the Field of Brain Energy Metabolism. Intern. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2024) 1433. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Bittar, Y. Charnay, L. Pellerin, C. Bouras, P.J. Magistretti, Selective distribution of lactate dehydrogenase isoenzymes in neurons and astrocytes of human brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 16 (1996) 1079-1089. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, G. Pellegri, P.G. Bittar, Y. Charnay, C. Bouras, J.L. Martin, N. Stella, P.J. Magistretti, Evidence supporting the existence of an activity-dependent astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle. Dev. Neurosci. 20 (1998) 291-299. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, G. Pellegri, J.L. Martin, P.J. Magistretti, Expression of monocarboxylate transporter mRNAs in mouse brain: support for a distinct role of lactate as an energy substrate for the neonatal vs. adult brain. Proc. Nat Acad Sci, 95 (1998) 3990-3995. [CrossRef]

- K. Pierre, L. Pellerin, R. Debernardi, B.M. Riederer, P.J. Magistretti, Cell-specific localization of monocarboxylate transporters, MCT1 and MCT2, in the adult mouse brain revealed by double immunohistochemical labeling and confocal microscopy. Neuroscience, 100 (2000) 617-627. [CrossRef]

- Aubert, R. Costalat, P.J. Magistretti, L. Pellerin, Brain lactate kinetics: modeling evidence for neuronal lactate uptake upon activation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 102 (2005) 16448-16453. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Bouzier-Sore, P. Voisin, P. Canioni, P.J. Magistretti, L. Pellerin, L. Lactate is a preferential oxidative energy substrate over glucose for neurons in culture. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23 (2003) 1298-1306. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Bouzier-Sore, P. Voisin, V. Bouchaud, E. Bezancon, J. Franconi, L. Pellerin, Competition between glucose and lactate as oxidative energy substrates in both neurons and astrocytes: a comparative NMR study. European J. Neurosci. 24 (2006) 1687-1694. [CrossRef]

- L. Pellerin, A.K. Bouzier-Sore, A. Aubert, S. Serres, M. Merle, R. Costalat, P.J. Magistretti, P.J. Activity-dependent regulation of energy metabolism by astrocytes: an update. Glia, 55 (2007) 55, 1251-1262. [CrossRef]

- M.T. Wyss, R. Jolivet, A. Buck, P.J. Magistretti, B. Weber, In vivo evidence for lactate as a neuronal energy source. J. Neurosci. 31 (2011) 7477-7485. [CrossRef]

- P. Proia, C.M. Di Liegro, G. Schiera, A. Fricano, I. Di Liegro, Lactate as a metabolite and a regulator in the central nervous system. Internat. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (2016) 1450. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, G.S. Wilson, A temporary local energy pool coupled to neuronal activity: fluctuations of extracellular lactate levels in rat brain monitored with rapid-response enzyme-based sensor. J. Neurochem. 69 (1997) 1484-1490. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, J.J. Miller, R.S. Payne, B.M. Rigor, An increase in lactate output by brain tissue serves to meet the energy needs of glutamate-activated neurons. J. Neurosci. 19 (1999) 34-39. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Brooks, Intra-and extra-cellular lactate shuttles. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 32 (2000) 790-799. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Brooks, Cell–cell and intracellular lactate shuttles. J. Physiol. 587 (2009) 5591-5600. [CrossRef]

- H. Qu, A. Håberg, O. Haraldseth, G. Unsgård, U. Sonnewald, U. 13C MR spectroscopy study of lactate as substrate for rat brain. Dev. Neurosci 22 (2000) 429-436. [CrossRef]

- S. Mangia, G. Garreffa, M. Bianciardi, F. Giove, F. Di Salle, B. Maraviglia, The aerobic brain: lactate decrease at the onset of neural activity. Neuroscience, 118 (2003) 7-10. [CrossRef]

- D. Smith, A. Pernet, W.A. Hallett, E. Bingham, P.K. Marsden, S.A. Amiel, Lactate: a preferred fuel for human brain metabolism in vivo. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23 (2003) 658-664. [CrossRef]

- K.A. Kasischke, H.D. Vishwasrao, P.J. Fisher, W.R. Zipfel, W.W. Webb, Neural activity triggers neuronal oxidative metabolism followed by astrocytic glycolysis. Science, 305 (2004) 99-103. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Herard, A. Dubois, C. Escartin, K. Tanaka, T. Delzescaux, P. Hantraye, G. Bonvento, Decreased metabolic response to visual stimulation in the superior colliculus of mice lacking the glial glutamate transporter GLT-1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22 (2005) 1807-1811. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, R.S. Payne, Lactate, not pyruvate, is neuronal aerobic glycolysis end- product: an in vitro electrophysiological study. Neuroscience, 147 (2007) 613-619. [CrossRef]

- T. Hashimoto, R. Hussien, H. Cho, D. Kaufer, G.A. Brooks, Evidence for the mitochondrial lactate oxidation complex in rat neurons: demonstration of an essential component of brain lactate shuttles. PloS one, 3 (2008) e2915. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Erlichman, A. Hewitt, T.L. Damon, M. Hart, J. Kurascz, A. Li, J.C. Leiter, Inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter 2 in the retrotrapezoid nucleus in rats: a test of the astrocyte–neuron lactate-shuttle hypothesis. J. Neurosci. 28 (2008) 4888-4896. [CrossRef]

- C.N. Gallagher, K.L. Carpenter, P. Grice, D.J. Howe, A. Mason, I. Timofeev, D.K. Menon, P.J. Kirpatrick, J.D. Pickard, G.R. Sutherland, P.J. Hutchinson, The human brain utilizes lactate via the tricarboxylic acid cycle: a 13C-labelled microdialysis and high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance study. Brain, 132 (2009) 2839-2849. [CrossRef]

- J. Chuquet, P. Quilichini, E.A. Nimchinsky, G. Buzsáki, Predominant enhancement of glucose uptake in astrocytes versus neurons during activation of the somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci. 30 (2010) 15298-15303. [CrossRef]

- C.R. Figley, Lactate transport and metabolism in the human brain: implications for the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis. J. Neurosci 31 (2011) 4768-4770. [CrossRef]

- Dias, E. Fernandes, R.M. Barbosa, J. Laranjinha, A. Ledo, Astrocytic aerobic glycolysis provides lactate to support neuronal oxidative metabolism in the hippocampus. Biofactors, 49 (2023) 875-886. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pan, M. Monje, Neuron–Glial Interactions in Health and Brain Cancer. Adv. Biol. 6 (2022) 2200122. [CrossRef]

- E. Jung, J. Alfonso, H. Monyer, W. Wick. F. Winkler, Neuronal signatures in cancer. Intern J. Cancer, 147 (2020) 3281-3291. [CrossRef]

- H. Tianzhen, H. Shi, M. Zhu, C. Chen, Y. Su, S. Wen, X. Zhang, J. Chen, Q. Huang, H. Wang, Glioma-neuronal interactions in tumor progression: Mechanism, therapeutic strategies and perspectives. Inter. J. Oncol. 61 (2022) 104. [CrossRef]

- S.C. Buckingham, S.L. Campbell, B.R. Haas, V. Montana, S. Robel, T. Ogunrinu, H. Sontheimer, Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nature Med. 17 (2011) 1269-1274. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Campbell, S.C. Buckingham, H. Sontheimer. Human glioma cells induce hyperexcitability in cortical networks. Epilepsia 53 (2012) 1360-1370. [CrossRef]

- V. Venkataramani, D.I. Tanev, C. Strahle, A. Studier-Fischer, L. Fankhauser, T. Kessler, C. Körber, M. Kardorff, M. Ratliff, R. Xie, H. Horstmann, M. Messer, S.P. Paik, J. Knabbe, F. Sahm, F.T. Kurz, A.A. Acikgöz, F. Herrmannsdörfer, A. Agarwal, D.E. Bergles, A. Chalmers, H. Miletic, S. Turcan, C. Mawrin, D. Hänggi, H-K. Liu, W. Wick, F. Winkler, T. Kuner, Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature, 573 (2019) 538. [CrossRef]

- Z-C, Ye, H. Sontheime, Glioma Cells Release Excitotoxic Concentrations of Glutamate. Cancer Res, 59 (1999) 4383–4391.

- D.A. Turner, D.C. Adamson, Neuronal-astrocyte metabolic interactions: understanding the transition into abnormal astrocytoma metabolism. J. Neuropathol. Exper. Neurol. 70 (2011) 167-176. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, R.S. Payne, J.J. Miller, M.T. Tseng, B.M. Rigor, Blockade of lactate transport exacerbates delayed neuronal damage in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 895 (2001) 268-272. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, R.S. Payne, M.T. Tseng, E. Gozal, D. Gozal, Excitotoxic preconditioning elicited by both glutamate and hypoxia and abolished by lactate transport inhibition in rat hippocampal slices. Neurosci. Let. 307 (2001) 151-154. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Swanson, S.H. Graham, Fluorocitrate and fluoroacetate effects on astrocyte metabolism in vitro. Brain Res. 664 (1994) 94-100. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).