1. Introduction

Background and Rationale

Fatigue, social anhedonia, and social functioning are critical constructs that influence individuals’ daily experiences and overall psychological well-being. Fatigue is another term used in this study and is described as a constant feeling of tiredness which is usually related to poor physical and /or mental health. On the other hand, social anhedonia is a reduced ability to derive pleasure from social activities. Among the common symptoms of these two disorders, the affective and social aspect of people’s lives, or social functioning, tends to suffer the most and the most often.

Schizotypy, social anhedonia, social functioning, and fatigue are each one aspects of psychological disorders — primarily of depression and schizophrenia — but no researchers have compared the last three of these four within the same and across different individuals. Fatigue is defined as a pervasive, subjective experience of physical, cognitive, or emotional exhaustion which is severe enough to impair day-to-day functioning. The other word for social anhedonia is the decreased ability to experience pleasure from social interactions. Together, these constructs have a large effect on how well an individual functions in social environments — in other words, social functioning.

These variables have been illuminated in previous research in its interactions. For instance, Billones et al. (2020), [

5] point out that fatigue and anhedonia frequently coexist but are distinct constructs that have varying deleterious effects on quality of life (Billones et al., 2020) [

5]. Fatigue in psychiatric populations does not remit, even after other primary symptoms are treated, and compounds social withdrawal and functional decline (Laraki et al., 2023) [

16] [p.1098932].

It has also been linked to reduced social functioning and more loneliness. In their work, Tan et al. (2020) [

23] [pp.280-289] found that feeling lonely mediated the relationship between social anhedonia and impaired social functioning (such that people with high levels of social anhedonia reported less social engagement and felt more isolated (Tan et al., 2020) [

23] [pp.280-289] Quantitative data from this study indicated that the average age of the 824 participants was 21.03 years old and that of these 72.3% were female, implying that social anhedonia has a profound effect on one’s social functioning. The consequences for interventions are huge, meaning interventions should attempt to reduce loneliness to increase overall social engagement and quality of life.

In addition, the role of fatigue in increasing anhedonia in the clinical scene has been emphasized in scholarship on people clinically diagnosed with schizophrenia. Even controlling depression, fatigue accounted for approximately 20% of the variance in anhedonia, demonstrating that fatigue has an independent and important impact on social functioning (Laraki et al., 2023) [

16] [p.1098932]. The evidence supporting this finding comes from further evidence that social anhedonia predicts long term social impairments in individuals in a three-year longitudinal study by Cohen et al. (2020) [

8] [273–283]. According to Cohen et al. (2020) [

8] [273–283], social anhedonia was associated with lower educational attainment and higher unemployment and continued social withdrawal, relative to control groups.

Finally, the role of fatigue, social anhedonia, and social functioning in this complex interplay and highlight how understanding social impairments in psychiatric populations depends on understanding this interplay. Future research should focus on intervening in these interrelations to optimize patient outcomes clinical and non-clinical.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional, quantitative study design was implemented. Participants were required to be free from specific physical or psychological illnesses in accordance with the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria, or they had to be free of chronic fatigue syndrome. Standardized instruments employed included the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), the Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire (SFQ), and the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS). Furthermore, descriptive statistics, bivariate analyses, correlation, and mediation analyses were conducted to examine the collected data and elucidate the interrelationships among the constructs using the SPSS software.

This study employed quantitative, cross-sectional research design using standardized self-report questionnaires to investigate the relationships between fatigue, social anhedonia and social functioning. Such research designs are commonly used in mental health research because they provide a ‘picture’ of variables at a single point in time across a population (Enneking et al., 2018) [

12] [pp.883-889], which is cost-effective and time-efficient (Bryman, 2006) [

7] [pp.113-197].

This design also allows for cross-sectional comparisons between other types of people (e.g., those with and without diagnosed conditions including MDD and schizophrenia) that are important for understanding the incremental validity of social anhedonia and fatigue regarding social dysfunction (Blanchard et al., 2011) [

6] [pp.587-602]. In addition, quantitative measure includes other numerical data like frequency and severity of symptoms and many more and can establish statistical equation between these two variables by using frequency analysis or structural equation model. It provides a solid basis within which to establish the ways in which fatigue and social anhedonia might impact on social relations on a sample wide basis.

Participants

A diverse mixed gender group of 125 adults, between the ages of 25 and 60 among students and faculty staff in the Arab region. The sample group will exclude individuals with specific health conditions (e.g., chronic fatigue syndrome, sleep disorders etc..) that could confound the result.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size for this study is determined using G*Power, a tool widely utilized for calculating statistical power in psychological research. For a standard multiple frequency analysis with three predictor variables—fatigue, social anhedonia, and social functioning—a minimum sample size of 114 participants is required to detect a medium effect size (f² = 0.15) 80:80 at 5% significance level. However, if the sample size can be expanded to about 150, then the number of lost subjects will be small, and the sample results will generalize well to the population (Rhodes & Plotnikoff, 2005) [

21] [pp.547-555].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The sample for the study will comprise adults, 18 to 65 years, excluding those diagnosed with fatigue and or social anhedonia. In male known to have higher fatigue and social anhedonia levels, certain exclusion criteria include individuals diagnosed with MDD or schizophrenia. At the end of the study surveys, participants will require an internet connection to continue and complete these surveys will be on a secure platform.

Participants with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) are not included in the study because generally fatigue can influence the outcome of the study (Bennett et al., 2014) [

4] [pp.379-388]. It will also exclude those who are possibly receiving major psychological or pharmacological treatment targeting directly fatigue, social anhedonia or their aftermath, as treatment might contaminate the outcomes of the study.

Participant Characteristics

We will seek to achieve as even a gender distribution as possible and will include participants from a variety of sociodemographic backgrounds. In recent studies it has been shown that sociodemographic factors like education level and employment status are very important determinants of fatigue and social functioning. An example is that people with less social support or more social stress report higher fatigue (Mancuso et al., 2006) [

17] [pp.1496-1502]. Conducting more comprehensive analyses of the manner in which these variables interact across different population groups, then we need to ensure these variables are diverse along specific axes.

Previous research suggests social functioning declines with age and fatigue is often higher among older adults with chronic conditions, so the age range for participants has been selected from 18 to 65 years old. A significant portion of this range also includes adults working and/or in families, where impairments in social functioning are particularly relevant (Watt et al., 2000) [

25] [191–200].

Materials

Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) (De Vries et al., 2004) [

10] [pp.279-291]

Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) is widely used to assess fatigue in various domains such as physical, emotional as well as cognitive fatigue. It is comprised of 10 items on which respondents rate their experience of fatigue symptoms on a five-point Likert scale, regarding how often they occur. Cronbach’s alpha values range from 0.71 to 0.82 (indicating good internal consistency reliability); all 17 items contribute to reliability; and the FAS has displayed strong psychometric properties (Ho, et al., 2020) [

13] [pp.3234-3241]. Also, analysis of the FAS by factor analysis revealed that the FAS has a unidimensional structure, supporting its use as a comprehensive fatigue assessment tool (Michielsen et al., 2003) [

19] [pp.345-352]. This measure is particularly useful in this study because it is widely used and has demonstrated reliability and validity in measuring general fatigue that counters social functioning as well as results in higher social anhedonia in the participants.

The FAS has been basically developed and then this checklist has been tested in other population includes peoples with stroke, cancer or multiple Sclerosis other than Parkinson’s diseases and it is beneficial tool for the measurement of fatigue in the different health condition (Tyson & Brown, 2014) [

25] [pp.804-816.]. For instance, it established that in stroke patients, the FAS scores were significantly connected with poorer social functioning and mental well-being as effectiveness raised on the FAS scale tied to higher degrees of fatigue (Ho et al., 2020) [

13] [pp.3234-3241]. Second, the FAS is suited for our investigation because it permits comparison between fatigue, social anhedonia, and social functioning.

Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (Tyrer et al., 2005) [

23]

Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) is a common tool that can be used to evaluate fatigue in any given sphere of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive fatigue. This consists of ten statements on which the respondents give a quintuple Likert scale rating of how often they encounter fatigue symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha values range from 0.71 to 0.82 (indicating good internal consistency reliability); all 17 items contribute to reliability; and the FAS has displayed strong psychometric properties (Ho, et al., 2020) [

13] [pp.3234-3241]. Moreover, the factor analysis of the FAS indicated that the FAS indeed has a unidimensional construct validity making it suitable for use as an overall measure of fatigue. This measure is important in the present study due to its reliability and validity to assess the level of general fatigue the participants may present, which may hinder social functioning and lead to heightened levels of social anhedonia.

Once developed, the FAS has been validated in several different populations including people with stroke, cancer or multiple sclerosis and is a useful tool to measure fatigue in various health conditions (Tyson & Brown, 2014) [

25] [pp.804-816.]. For example, in stroke survivors, the FAS scores were strongly associated with worse social functioning and mental health outcomes, with higher scores on the FAS correlating with more fatigue (Ho et al., 2020) [

13] [pp.3234-3241]. Second, FAS lends itself to our study because it allows for examination of the relation between fatigue, social anhedonia, and social functioning.

Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS) (Eckblad et al., 1982) [

11]

The Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS) is a self-report measure of diminished pleasure from social interaction that is the core feature of social anhedonia. It is a 40-item scale that includes effective and behavioral components of social anhedonia, such as reduction in the interest in forming social bonds, and in taking part in pleasant social activities (Barkus & Badcock, 2019) [

2] [p.436257]. Cronbach’s alpha values of the RSAS have typically been above 0.90 internally and have shown good convergent validity with other measures of anhedonia (Billones et al., 2020) [

5] [p.273].

In fact, the RSAS has been applied to various clinical and nonclinical populations, including people with schizophrenia, depression, and disorders such as anxiety (Barkus 2021) [

1] [pp.77-89]. Individuals who are higher on the RSAS are shown to have poorer social functioning, more loneliness and less social support (Tan et al., 2020) [

22]. This measure is thus essential to this study as it will quantify aspects of social anhedonia and link them to fatigue and social functioning, addressing known gaps in previous research outlined by Wernette (2018) [

27].

Procedure

Recruitment of participants will be done on online platforms (Qualtrics) among adults 18 to 65 years old of varying levels of fatigue and social anhedonia. The inclusion and exclusion criteria will be used to screen participants for eligibility so that the sample as studied comes from the population for study. Participants will first be asked to complete Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), Social Functioning Scale (SFS), and Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS) through Qualtrics, an online survey platform for secure data collection, and be informed consent obtained for them.

The study will be cross sectional and will collect data at a single point in time. Participants will first complete the FAS to determine general fatigue, then the SFS and RSAS will be used to measure social functioning and social anhedonia, respectively. Each participant’s unique identifier will be assigned to prevent reidentification, and records will be stored in a database encrypted to the research team only.

All identifiable information will be removed from the dataset before it is analyzed to ensure data security and confidentiality. The data will be stored on a server that will be password protected, and only de-identified data will be used for statistical analysis of data. All personal information that participants will provide during recruitment will be separated from the research data and will not be able to relate to participants.

The data will be analyzed using SPSS, and descriptive statistics will be calculated for summarize participant demographics, fatigue levels, social functioning scores and social anhedonia scores. Fatigue will be related to social anhedonia and social functioning using multiple frequency analysis. Data collection will begin only after ethical approval can be obtained from the relevant institutional review board.

3. Data Analysis

The data analysis for this study will employ SPSS software, with a focus on descriptive statistics, analysis, correlation, bivariant and mediation analysis.

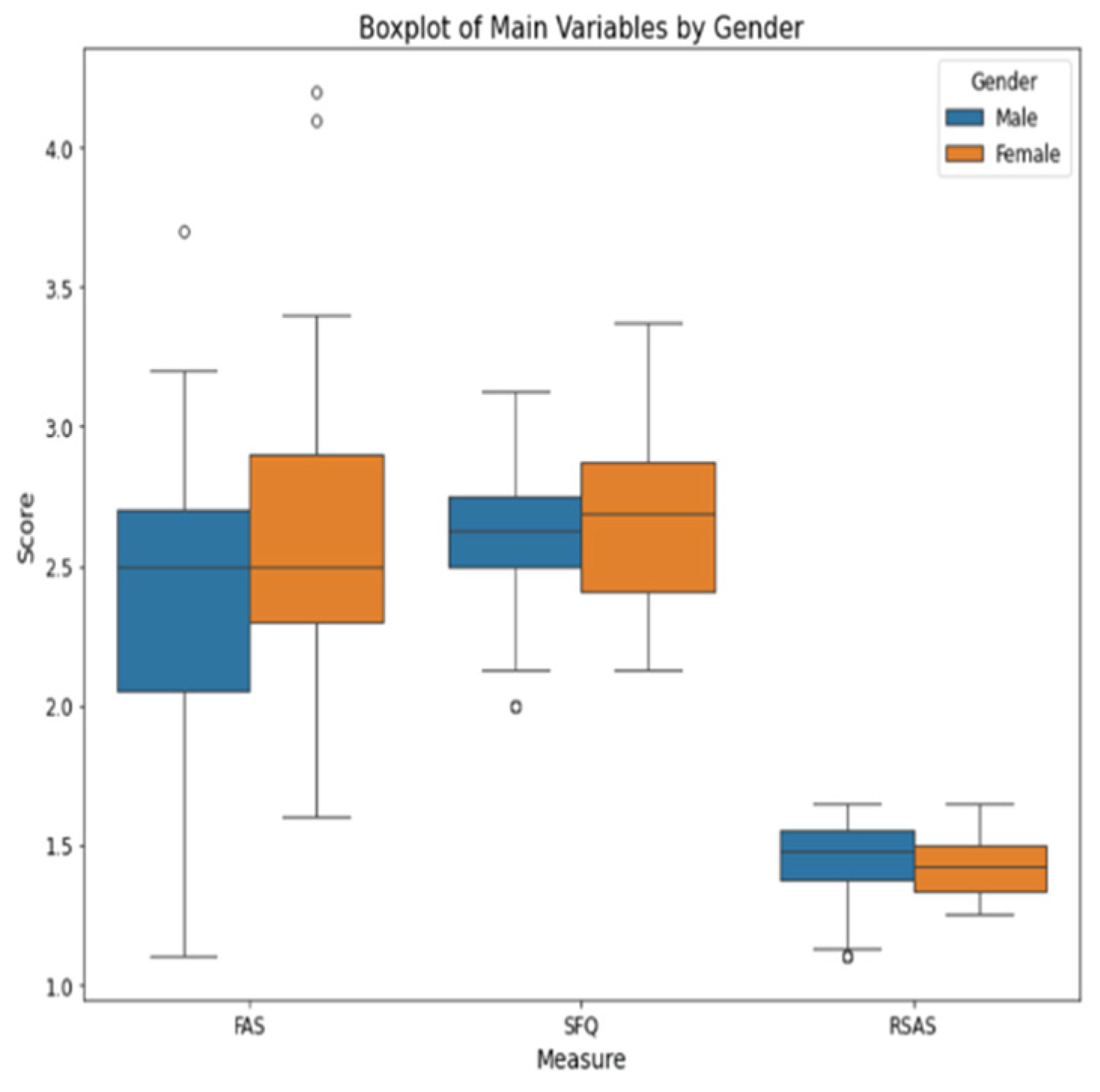

The normality of the data was assessed using histograms and Q-Q plots to ensure appropriate distributional assumptions. For bivariate analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman correlation were employed to examine relationships between variables. Graphs were generated using Python to visually support the findings. The education variable was excluded from further analysis due to highly uneven frequencies and a relatively small sample size; notably, all high school and PhD holders in the dataset were male, contributing to a significant gender imbalance. Three standardized questionnaires, the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire (SFQ), and the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS)—were each summarized into single variables by calculating the mean of their respective items. A descriptive table was prepared to present the sample characteristics. Gender-based bivariate analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test revealed a significant difference in FAS scores between males and females.

The research stratified the data by gender, separating it into male and female groups. This stratification facilitated the identification of differences, and mediation tests were subsequently conducted separately for each gender

Total Effect: The influence of the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) on the Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire (SFQ) without accounting for the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS).

Direct Effect: The effect of the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) on the Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire (SFQ) after controlling for the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS).

Indirect Effect: The effect of the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) on the Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire (SFQ) mediated through the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS)

Ethical Considerations

This study will adhere to institutional and international ethical standards, with ethical approval to be obtained from the relevant university ethics committee prior to the commencement of data collection. This process ensures compliance with established guidelines designed to protect the rights and welfare of participants (Pan, 2018) [

20]. Participant anonymity and confidentiality will be strictly maintained; all collected data will be anonymized and coded to prevent identification of individuals. The anonymized data will be securely managed and analyzed using SPSS software, with only aggregated results presented in the final report (Rockwood & Hayes, 2020) [

22] [pp.396-414]. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants before their involvement in the study. The consent process will include detailed information about the research purpose, procedures, potential risks, and the voluntary nature of participation. Participants will also be informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. These measures uphold ethical research principles, including respect for participant autonomy and dignity (Mardanian-Dehkordi et al., 2018) [

18] [pp210–214]. Finally, the study will follow strict ethical guidelines to protect participant rights, and to secure the integrity of the research process.

4. Results

4.1. Gender Distribution

They provide a response rate of 89.3%. Of these 125 participants, 55 (44%) identified as male and 70 (56%) as female as shown in

Table 1 below. The gender distribution also mirrors a finding of higher prevalence rates of fatigue and social dysfunction in females reported in the literature, which may be due to biologic and psychosocial factors. For example, females might experience greater levels of fatigue and social withdrawal, which could be related to hormonal changes or caregiving responsibilities (Jiang et al., 2023) [

14] [pp.949-958.].

The fact that females (56%) were overrepresented in this study is important, given that it permits a closer examination of sex differences in social functioning and anhedonia. Females have been shown to be more likely to report symptoms of social anhedonia when they have mental health challenges and may offer a fine tuning of their social functioning impairments (Barthel et al., 2020) [

3] [pp1013-1021]. The data is also consistent with a hypothesis that women might have more fatigue and associated social effects, raising the need to develop gender sensitive interventions.

The (

Table 1) above indicates a slightly higher representation of females in the study compared to males. Most participants have a bachelor’s degree (BSc), followed by those with a master’s degree (MSc). There are fewer participants with only a high school education or a PhD. The average score for fatigue assessment is 2.514, with a standard deviation of 0.523, indicating moderate variability in fatigue levels among participants. The average score for social functioning is 2.636, with a relatively low standard deviation of 0.270, suggesting that social functioning scores are consistent across participants. The average score for social anhedonia is 1.428, with a low standard deviation of 0.132, indicating that social anhedonia levels are quite consistent among participants.

4.2. Educational Status

The education level of participants varied significantly, with 52.8% holding a bachelor’s degree, 37.6% a master’s degree, 5.6% having completed high school, and 4% possessing a PhD. These statistics hint at a more well-educated sample thus suggesting that higher educational attainment could influence the participants’ self-perception and coping mechanisms regarding fatigue and anhedonia. For example, Billones et al. (2020) [

5] have associated higher education with better coping strategies and lower prevalence of fatigue related to social dysfunction.

Importantly, those with master’s and PhD qualifications (41.6%) are more likely to be in demanding professional roles, making fatigue more likely. This is consistent with evidence that social withdrawal and fatigue are reported in high stress academic or professional contexts (Laraki et al., 2023) [

16] [p.1098932].

Table 2 above shows A mean fatigue assessment score is significantly higher for females (2.626) compared to males (2.371). The p-value of 0.027 indicates that this difference is statistically insignificant, However, suggesting that females in this sample could experience higher levels of fatigue than males in a larger sample size.

The mean social functioning score is slightly higher for females (2.664) compared to males (2.600). However, the p-value of 0.287 indicates that this difference is statistically insignificant, suggesting that there is no significant difference in social functioning between males and females in this sample.

Furthermore, the mean for social anhedonia is slightly higher in Male with (1.436) compared to female (1.422). However, the p-value of 0.077 indicates that this difference is statistically insignificant, suggesting that there is no significant difference in social anhedonia between males and females in this sample.

The boxplot graph in (

Figure 1) above compares the scores of three measures (Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire (SFQ), and Revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS)) between males and females.

Table 3 above shows a correlation coefficients between the main variables are relatively low, indicating weak relationships. Specifically, fatigue assessment has a weak negative correlation with both social functioning (-0.065) and social anhedonia (-0.143). Social functioning and social anhedonia have a weak positive correlation (0.082). These low correlations suggest that the variables do not strongly influence each other directly.

Table 4 above shows the Total Effect for male shows overall influence of fatigue on social functioning is positive but statistically insignificant (p = 0.146).

Direct Effect: The direct influence of fatigue on social functioning, controlling social anhedonia, is also positive and approaches insignificance (p = 0.056), suggesting a potential direct relationship.

Indirect Effect: The indirect effect through social anhedonia is negatively insignificant, indicating that social anhedonia does not mediate the relationship between fatigue and social functioning for both genders.

In the other hand, the Total Effect for female shows overall influence of fatigue on social functioning is negative and statistically significant (p = 0.007), indicating that higher fatigue is associated with lower social functioning in females.

Direct Effect: The direct influence of fatigue on social functioning, controlling social anhedonia, is also negative and significant (p = 0.008), suggesting a strong direct relationship.

Indirect Effect: The indirect effect through social anhedonia is negligible and insignificant, indicating that social anhedonia does not mediate the relationship between fatigue and social functioning for females.

The analysis reveals a gender-specific pattern in the relationship between fatigue and social functioning. For males, fatigue appears to have a positive but statistically insignificant total and direct effect on social functioning, with no meaningful mediation by social anhedonia. This suggests that while fatigue might be associated with improved social functioning in men, the evidence is not strong enough to confirm a reliable effect.

In contrast, for females, fatigue demonstrates a significant negative impact on social functioning, both in total and direct effects. This indicates that higher levels of fatigue are reliably associated with poorer social functioning among women. Like males, the indirect effect through social anhedonia remains negligible and statistically insignificant, suggesting that social anhedonia does not mediate this relationship in either gender.

Overall, these findings highlight a potential gender difference in how fatigue influences social functioning, with a more pronounced and detrimental effect observed in females.

5. Discussion

This study adds to the growing conversation about how fatigue affects people differently, especially when it comes to gender. The notable negative link between fatigue and social functioning in women supports earlier findings that suggest women might be more susceptible to the social downsides of fatigue. This could be due to a mix of biological, psychological, or sociocultural reasons, like hormonal changes, caregiving roles, or a greater emotional sensitivity to social pressures. On the flip side, the lack of a significant connection in men implies that fatigue might not disrupt their social lives in the same way, or perhaps men have different ways of coping. Interestingly, social anhedonia—essentially a lack of interest in social interactions—doesn’t seem to play a mediating role for either gender. This means that while it’s related to social functioning, it doesn’t statistically clarify how fatigue leads to social difficulties in this group. These insights highlight the need to consider gender when conducting psychosocial research and designing interventions. Creating targeted strategies to tackle fatigue-related social issues in women could be especially helpful.

6. Conclusions

This study reveals a distinct gender pattern in how fatigue impacts social functioning. While fatigue significantly hinders social interactions for women, it doesn’t seem to have the same effect on men, and social anhedonia doesn’t mediate this relationship for either group. These findings suggest that efforts to reduce fatigue could directly enhance social functioning, particularly for women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Naif AL-Mutawa and Ahmed Alshammari; Formal analysis, Ahmed Alshammari; Funding acquisition, Naif AL-Mutawa; Investigation, Ahmed Alshammari; Methodology, Ahmed Alshammari; Project administration, Naif AL-Mutawa; Resources, Naif AL-Mutawa and Ahmed Alshammari; Software, Ahmed Alshammari; Supervision, Naif AL-Mutawa; Visualization, Naif AL-Mutawa; Writing—original draft, Ahmed Alshammari; Writing—review & editing, Naif AL-Mutawa.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Northumbria reference No 2024-8085-8389. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. The ethical process was approved on 20/08/202. The measures are clearly implemented in the following:.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All participants will have the options to skip or withdraw.

Data Availability Statement

The Datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere appreciation to Dr. Ayad Salhieh, Assistant to the President for Student Relations at the Australian University in Kuwait, for his valuable support. We are also grateful to all participants who generously contributed their time and insights. Special thanks are extended to Sara Aman, Information Management Team Leader at Saudi Arabian Chevron; the Educational Consultant at Al-Nibras School; and the Psychologist at Socoon Clinic for their meaningful contributions. Finally, we acknowledge Dr. Raza Ziaeian for his support throughout the analysis of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. All affiliations and financial involvements that could be perceived as potential conflicts have been disclosed.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFS |

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |

| RSAS |

Revised social anhedonia scale |

| FSQ |

Social Functioning Scale Questionnaire |

| FAS |

Fatigue Assessment Scale |

| MDD |

Major Depressive Disorder |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Barkus, E., 2021. The effects of anhedonia in social context. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 8, pp.77-89. [CrossRef]

- Barkus, E. and Badcock, J.C., 2019. A transdiagnostic perspective on social anhedonia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, p.436257. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Barthel, A. L., Pinaire, M. A., Curtiss, J. E., Baker, A. W., Brown, M. L., Hoeppner, S. S., ... & Hofmann, S. G. (2020). Anhedonia is central for the association between quality of life, metacognition, sleep, and affective symptoms in generalized anxiety disorder: A complex network analysis. Journal of affective disorders, 277, pp1013-1021. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B., Goldstein, D., Chen, M., Davenport, T., Vollmer-Conna, U., Scott, E., Hickie, I. and Lloyd, A., 2014. Characterization of fatigue states in medicine and psychiatry by structured interview. Psychosomatic Medicine, 76, pp.379-388. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Billones, R.R., Kumar, S. and Saligan, L.N., 2020. Disentangling fatigue from anhedonia: A scoping review. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), p.273. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, J., Collins, L., Aghevli, M., Leung, W. and Cohen, A., 2011. Social anhedonia and schizotypy in a community sample: The Maryland longitudinal study of schizotypy. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(3), pp.587-602. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A., 2006. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: how is it done? Qualitative Research, 6(1), pp.113-197 [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024].

- Cohen, A. S., McGovern, J. E., Dinzeo, T. J., & Covington, M. A. (2020). Social anhedonia and clinical outcomes in early adulthood: A three-year follow-up study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(3), 273–283. [CrossRef]

- Curt, G., Breitbart, W., Cella, D., Groopman, J., Horning, S.J., Itri, L., Johnson, D.H., Miaskowski, C., Scherr, S.L., Portenoy, R. and Vogelzang, N., 2000. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. The Oncologist, 5(5), pp.353-360. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, J., Michielsen, H., Van Heck, G.L. and Drent, M., 2004. Measuring fatigue in sarcoidosis: the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS). British Journal of Health Psychology, 9(3), pp.279-291.

- Eckblad, M., Chapman, L. J., Chapman, J. P., & Mishlove, M. (1982). The Revised Social Anhedonia Scale.

- Enneking, V., Krüssel, P., Zaremba, D., Dohm, K., Grotegerd, D., Förster, K., Meinert, S., Bürger, C., Dzvonyar, F., Leehr, E., Böhnlein, J., Repple, J., Opel, N., winter, N., Hahn, T., Redlich, R. and Dannlowski, U., 2018. Social anhedonia in major depressive disorder: a symptom-specific neuroimaging approach. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(5), pp.883-889. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.Y.W., Lai, C. and Ng, S., 2020. Measuring fatigue following stroke: The Chinese version of the Fatigue Assessment Scale. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(14), pp.3234-3241. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., Liu, Q., Sun, Y., Yuan, Y., Wu, Z. and Yuan, Y., 2023. Network analysis of psychosomatic symptoms in pharmacists during the pandemic. Psychological Assessment, 35(11), pp.949-958. [Accessed 14 Dec. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Kratz, A.L., Braley, T.J., Foxen-Craft, E., Scott, E., Murphy, J.F. and Murphy, S.L., 2017. How do pain, fatigue, depressive, and cognitive symptoms relate to well-being and social and physical functioning in the daily lives of individuals with multiple sclerosis? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(11), pp.2160-2166. [Accessed 14 Dec. 2024].

- Laraki, Y., Bayard, S., Decombe, A., Capdevielle, D. and Raffard, S., 2023. Preliminary evidence that fatigue contributes to anhedonia in stable individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, p.1098932. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C., Rincon, M., Sayles, W. and Paget, S., 2006. Psychosocial variables and fatigue: a longitudinal study comparing individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and healthy controls. The Journal of Rheumatology, 33(8), pp.1496-1502. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024].

- Mardanian-Dehkordi, L., & Kahangi, L. S. (2018). The relationship between perception of social support and fatigue in patients with cancer. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 23(3), pp210–214. [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, H., De Vries, J. and Van Heck, G.L., 2003. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 54(4), pp.345-352.

- Pan, Y.C., 2018. Influence of social psychological factors on care outcomes of patients with type-2 diabetes. EAEEIE Annual Conference. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024].

- Rhodes, R. and Plotnikoff, R., 2005. Can current physical activity act as a reasonable proxy measure of future physical activity? Evaluating cross-sectional and passive prospective designs with the use of social cognition models. Preventive Medicine, 40(5), pp.547-555. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, N.J. and Hayes, A., 2020. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Behavior Research Methods, pp.396-414 [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024].

- Tyrer, P., Nur, U., Crawford, M., Karlsen, S., McLean, C., Rao, B., & Johnson, T. (2005).Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ).

- Tan, M., Shallis, A. and Barkus, E., 2020. Social anhedonia and social functioning: Loneliness as a mediator. PsyCh Journal, 9(2), pp.280-289 [Accessed 24 Oct. 2024].

- Tyson, S. and Brown, P., 2014. How to measure fatigue in neurological conditions? A systematic review of psychometric properties and clinical utility of measures used so far. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(8), pp.804-816. [CrossRef]

- Watt-Watson, J., Garfinkel, P., Gallop, R., Stevens, B., & Streiner, D. (2000). The impact of nurses’ empathic responses on patients’ pain management in acute care. Nursing Research, 49, 191–200. [CrossRef]

- Wernette, C.J., 2018. Social functioning in anhedonics: A daily diary study. Behavioral Psychology. [Accessed 14 Dec. 2024]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).