1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

The global energy transition has positioned green hydrogen as a critical solution for deep decarbonization, offering a clean alternative to fossil fuels through renewable-powered water electrolysis. Unlike conventional methods that emit significant

, green hydrogen production achieves near-zero emissions, making it essential for meeting international climate targets [

1,

2]. This technologyś versatility enables applications across hard-to-abate sectors, from heavy industry to long-distance transport, though its widespread adoption faces substantial technical and economic barriers.

1.2. National Context: The Case of Jordan

Jordanś unique combination of high solar irradiance and strategic location presents compelling opportunities for green hydrogen development. With 94% energy import dependence and 3% annual demand growth, the country urgently needs sustainable solutions [

3]. While renewables now contribute 20% of electricity generation, green hydrogen could further diversify the energy mix while addressing energy security concerns. Recent analyses suggest Jordan could produce cost-competitive green hydrogen using its solar potential, creating export opportunities alongside domestic benefits [

4]. However, realizing this potential requires overcoming systemic challenges across the hydrogen value chain.

Jordan faces multifaceted technological hurdles, particularly in electrolyzer efficiency and renewable energy integration [

5]. Current infrastructure limitations compound these challenges, as Jordan lacks dedicated hydrogen storage and distribution networks [

6]. Economic barriers loom large, with high production costs and immature markets requiring strategic policy interventions [

7]. These constraints are exacerbated by Jordanś water scarcity, which complicates the water-intensive electrolysis process despite potential seawater solutions [

8,

9].

1.3. Objectives of This Study

This study systematically examines these interconnected challenges through empirical research with Jordanian energy stakeholders. By analyzing technological readiness, infrastructure gaps, and economic viability, the research provides evidence-based recommendations for green hydrogen deployment. The findings aim to inform Jordanś ongoing energy transition while contributing practical insights to the broader literature on developing-country hydrogen economies.

Jordanś renewable energy targets—aiming for 1.8 GW capacity by 2025—demonstrate a strong commitment to sustainable development [

3]. The government recognizes green hydrogenś potential to leverage these renewable investments while creating new industrial opportunities [

4,

10]. However, success depends on addressing critical infrastructure gaps in grid modernization, storage systems, and transport networks. International partnerships and targeted policy support will be equally vital for attracting the necessary investments and technological capabilities to establish Jordan as a regional green hydrogen hub [

11].

2. Literature Review

Jordanś energy transition toward green hydrogen offers promising potential due to its abundant solar resources. However, it is also marked by critical constraints, particularly in water availability and infrastructure capacity [

12,

13,

14]. In response to these challenges, Jordan has made notable strides through the signing of 13 international agreements and the adoption of a National Hydrogen Strategy, which aims to achieve 8 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 [

15,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, successfully implementing this strategy depends on resolving persistent technological and economic barriers.

2.1. Technological Challenges

Several interrelated technological challenges impede the advancement of green hydrogen in Jordan. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the most critical issues include integrating intermittent renewable energy sources, the operational efficiency of electrolysis technologies, and the countryś severe water scarcity. These limitations must be systematically addressed to enable the large-scale deployment of hydrogen production systems.

Figure 1.

Core technological challenges in Jordanś hydrogen strategy.

Figure 1.

Core technological challenges in Jordanś hydrogen strategy.

2.1.1. Renewable Energy Integration

Jordan benefits from substantial solar energy potential, with average irradiance levels ranging from 5 to 7 kWh/m

2/day, making it an ideal candidate for renewable-powered green hydrogen production via water electrolysis [

18,

19,

20]. Despite this advantage, the intermittent nature of solar and wind energy introduces significant operational challenges. Variability in power supply can reduce electrolyzer efficiency and compromise system longevity, particularly under frequent start-stop cycling.

A range of advanced integration strategies is under active investigation to mitigate these effects. These include smart grid technologies, demand-side management systems, and hybrid renewable energy configurations that combine solar and wind with battery or thermal energy storage [

14,

21]. Among available electrolyzer technologies, Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) systems are considered especially suitable for such dynamic operating environments due to their fast transient response, compact form factor, and tolerance to variable power inputs [

22,

23].

Achieving stable grid-hydrogen coupling and maximizing the utilization of renewable energy sources will be critical to ensuring both the scalability and economic viability of green hydrogen production in Jordan.

2.1.2. Electrolysis Technology

Electrolyzer technologies used in green hydrogen production exhibit distinct trade-offs regarding efficiency, cost, and compatibility with renewable energy sources. Alkaline Electrolyzers (AEL) are commercially mature and widely available; however, they are less responsive to the variable output of renewables and generally require stable, continuous power input. In contrast, Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolyzers offer faster dynamic response and better compatibility with intermittent energy supply but rely on costly noble-metal catalysts, significantly increasing capital expenditure (CAPEX) [

22,

24].

Empirical studies conducted in Aqaba indicate that photovoltaic-driven electrolysis using current technologies can yield a levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) of approximately

$3.13/kg, underscoring the importance of integrating cost-effective renewable energy inputs into the production process [

4].

Recent Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) technology developments present a promising alternative. By eliminating the need for precious metals, AEM electrolyzers have the potential to reduce system costs by 30–40%, while retaining the ability to operate under fluctuating input conditions [

25]. These advancements suggest that strategic investment in next-generation electrolyzer technologies could substantially enhance the economic feasibility of green hydrogen in Jordan.

2.1.3. Water Resource Management

Jordanś extreme water scarcity—estimated at just 100 m

3 per capita per year—poses a critical constraint on the scalability of green hydrogen production [

26]. The electrolysis process requires approximately 9 L of purified water to produce one kilogram of hydrogen, adding significant stress to already limited freshwater resources.

To address this challenge, researchers have explored alternative water sources, including seawater desalination, wastewater treatment, and the utilization of brackish water [

15,

16,

27]. Among these, coastal desalination appears promising given Jordanś access to the Red Sea through Aqaba.

Technological advancements in membrane filtration systems are also contributing to efficiency gains. Recent studies suggest that next-generation membranes can reduce the specific water consumption of electrolysis by 20–30% while enhancing overall system performance [

22]. These innovations are essential for enabling hydrogen production in arid regions and underscore the importance of integrated water-energy planning in Jordanś hydrogen strategy.

2.2. Infrastructure Challenges

The successful deployment of a green hydrogen economy in Jordan hinges on addressing critical infrastructure deficiencies. As illustrated in

Figure 2, three primary areas present substantial barriers: transportation networks, grid compatibility, and the availability of electrolyzer facilities. These components are essential to supporting the full hydrogen value chain—from production to storage and distribution—at commercial scale.

Figure 2.

Key infrastructure challenges for green hydrogen deployment in Jordan.

Figure 2.

Key infrastructure challenges for green hydrogen deployment in Jordan.

2.2.1. Electrolyzer Facilities

The expansion of electrolyzer infrastructure in Jordan is constrained by high capital costs, ranging from

$500 to

$1,400 per kilowatt, and heavy reliance on imported technologies [

23,

28,

29]. These financial and supply chain dependencies pose a significant barrier to the timely scaling of domestic hydrogen production capacity.

As part of its National Hydrogen Strategy, Jordan has targeted deploying 1.5 GW of electrolyzer capacity by 2030 [

17]. Achieving this goal will require substantial investment in physical infrastructure and local technical capabilities, including workforce development, research and development (R&D), and public-private partnerships [

30]. Without these parallel efforts, deployment timelines may face delays and compromise cost-effectiveness.

2.2.2. Energy Grid Compatibility

Renewable energy sources currently contribute approximately 26% of Jordanś total energy mix. However, the grid infrastructure lacks the capacity and flexibility required to accommodate large-scale electrolyzer deployment [

10]. The intermittent nature of solar and wind power exacerbates grid stability challenges, particularly when integrated with the high and variable electrical loads associated with hydrogen production.

To address these issues, one emerging solution is the establishment of "hydrogen valleys"—localized industrial clusters that integrate hydrogen production, storage, and end-use applications within a confined geographic area. These hubs can enhance grid efficiency by minimizing transmission losses, smoothing renewable variability, and optimizing local demand-supply dynamics [

4,

11]. Such an approach may be particularly well-suited to Jordanś infrastructure context, offering a scalable model for integrating hydrogen technologies with existing energy networks.

2.2.3. Transportation Networks

Hydrogenś inherently low volumetric energy density poses significant logistical challenges, necessitating energy-intensive processes such as compression, liquefaction, or chemical conversion into carriers like ammonia or methanol to facilitate efficient transport [

14,

31]. These processes add technical complexity and substantial costs to the hydrogen supply chain.

In response, Jordan is exploring the adaptation of existing infrastructure for hydrogen transmission. One transitional strategy under consideration involves repurposing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen blending in the range of 5–20%

, enabling early-stage transport without the immediate need for dedicated pipelines [

32].

Additionally, the coastal city of Aqaba is positioned as a strategic export hub, capitalizing on its maritime access to support international hydrogen trade [

33]. Establishing a robust transportation infrastructure—both for domestic distribution and export—will be essential for integrating Jordan into emerging regional and global hydrogen markets.

2.2.4. Policy and Financing

Establishing a competitive green hydrogen economy in Jordan by 2030 will require an estimated investment of

$5- 7 billion [

34,

35]. This financing level necessitates mobilizing public and private capital, supported through Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) and sustained international cooperation.

Securing such investment is contingent upon clear policy signals and a stable regulatory environment that reduces investor risk and supports long-term infrastructure development. While Jordan has initiated several strategic roadmaps, key regulatory gaps persist, particularly in hydrogen safety standards, certification schemes, and cross-border trade protocols [

32,

36].

Accelerating the development of a comprehensive and harmonized governance framework that is aligned with the European Union (EU) and other best international practices will be vital. Such a framework will enhance investor confidence, attract green financing, enable technology transfer, and position Jordan as a credible hydrogen exporter within the MENA region.

2.3. Economic Challenges

The economic viability of green hydrogen production in Jordan remains a critical barrier to large-scale deployment. Current estimates place the levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) between

$3.13 and

$4.42 per kilogram, above global competitiveness benchmarks [

4]. This cost challenge is further compounded by the countryś water scarcity, which necessitates additional purification processes that raise operational expenses (OPEX).

Moreover, the limited size of Jordanś domestic hydrogen market restricts the potential for economies of scale, further inflating production costs [

18,

21]. Financing green hydrogen infrastructure also presents structural challenges, with constrained access to capital and investor risk concerns.

To address these issues, stakeholders have proposed a range of innovative financial instruments, including green bonds, blended finance models, and risk-sharing mechanisms [

12,

15,

19]. At the policy level, Jordanś Economic Modernization Vision and recent amendments to the national Electricity Law aim to create a more favorable investment climate for hydrogen projects and to stimulate both domestic and foreign capital inflows [

37].

3. Results

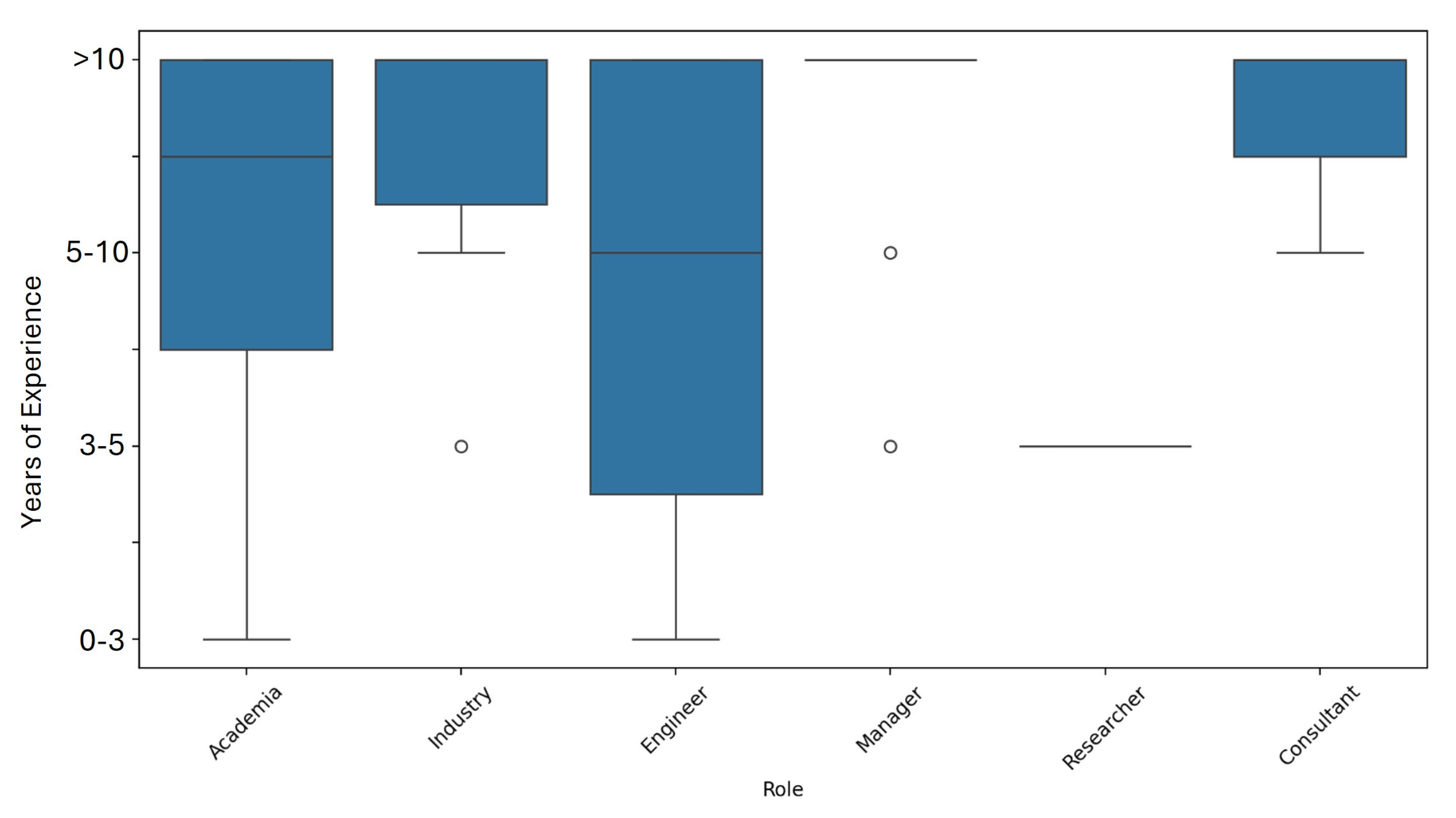

3.1. Stakeholder Demographics

A total of 52 professionals participated in the survey, providing a broad cross-section of Jordan’s energy community. Most respondents (74%) reported more than five years of sector experience, with the largest cohort (55%) exceeding ten years. Sector representation was well distributed: private industry (36%), government agencies (32%), academia (18%), non-governmental organizations (12%), and consulting firms (2%).

Participants occupied six primary professional roles: Engineers (16), Managers (13), Industry Professionals (10), Academics (8), Consultants (3), and Researchers (2).

Figure 3 illustrates how years of experience are distributed within each role, underscoring the seniority of the sample, particularly among engineers and managers, who together account for 29 of the 52 respondents.

Figure 3.

Experience profile of survey respondents by professional role. Bars indicate the number of individuals in each role, segmented by years of experience.

Figure 3.

Experience profile of survey respondents by professional role. Bars indicate the number of individuals in each role, segmented by years of experience.

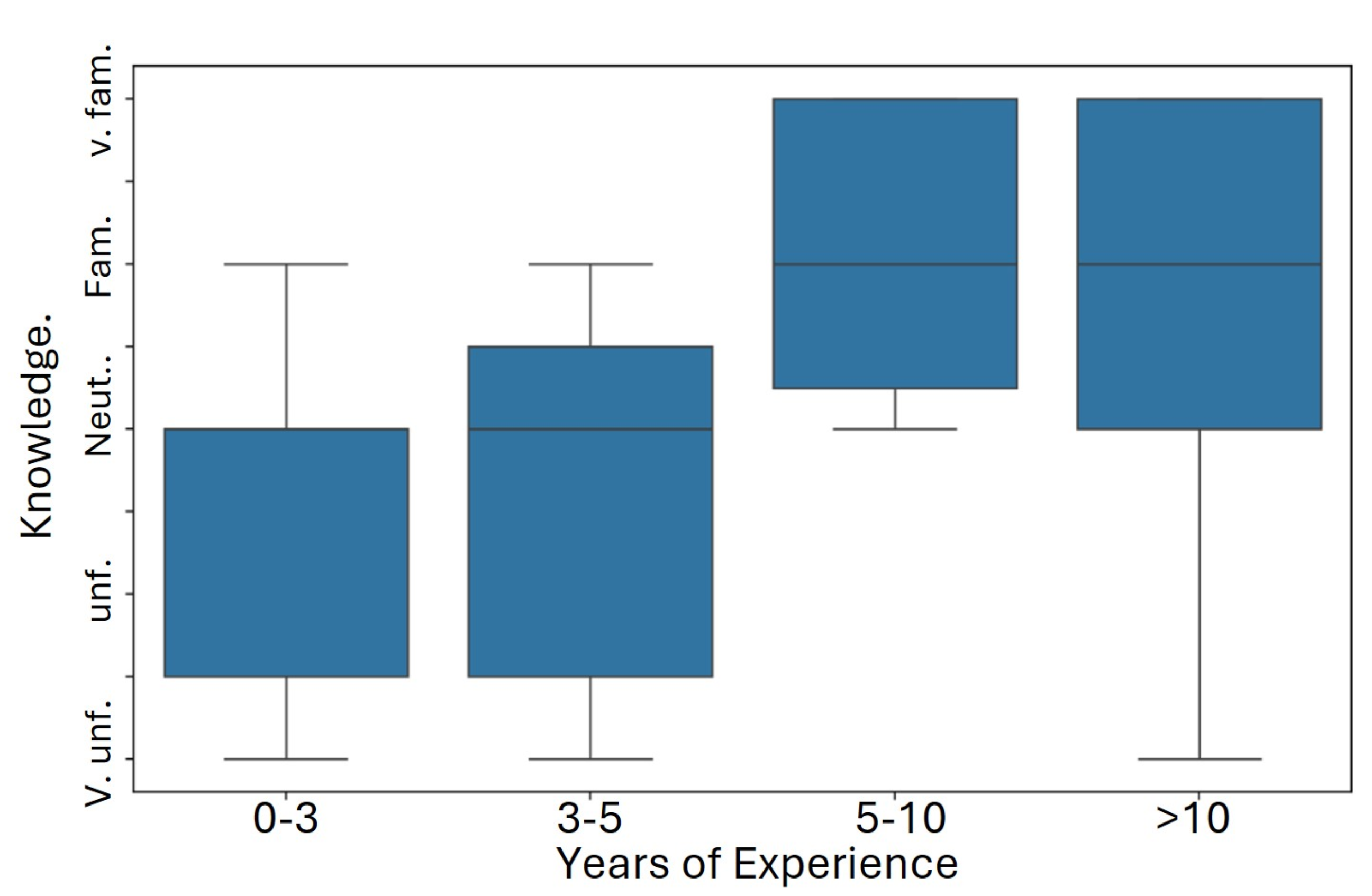

3.2. Knowledge of Green Hydrogen

Respondents exhibited a broad spectrum of familiarity with green hydrogen concepts. The largest share were neutral in their self-assessment (34.6%), followed by those who described themselves as very familiar (26.9%). Participants reporting either slight familiarity or no familiarity together constituted 23.1%, while expert-level familiarity accounted for 15.4%. This distribution confirms that the survey captured viewpoints ranging from introductory awareness to deep technical expertise.

A one-way ANOVA indicates that years of energy-sector experience significantly influence green-hydrogen knowledge

.

Figure 4 visualizes this relationship: professionals with more than ten years in the field are disproportionately represented in the

very familiar and

expert categories, whereas early-career respondents cluster around the neutral midpoint.

Figure 4.

Effect of professional experience on self-reported green-hydrogen knowledge. Columns show the percentage of respondents in each knowledge tier, segmented by three experience brackets.

Figure 4.

Effect of professional experience on self-reported green-hydrogen knowledge. Columns show the percentage of respondents in each knowledge tier, segmented by three experience brackets.

These findings suggest that practical exposure over time is a primary driver of subject-matter confidence. They also highlight a training opportunity: practitioners with fewer than five years of experience form the largest share of the slight and no familiarity groups, indicating where capacity-building programs could be most impactful.

3.3. Applications of Green Hydrogen

A clear consensus emerged on the strategic value of green hydrogen for Jordan’s energy transition. More than two–thirds of respondents (69.2%) rated green-hydrogen deployment as either Important or Very Important; only 3.8% viewed it as Not Important.

Multiple end-use segments were highlighted, often in combination:

The perceived benefits map closely onto these applications. Carbon-emission reduction was most frequently cited (71.2%), followed by enhanced energy security (69.2%), diversification of energy sources (67.3%), and new economic opportunities (61.5%).

Together, these results indicate strong stakeholder alignment around the multifaceted utility of green hydrogen, particularly in industry and power generation, and reinforce the technology’s role as both an environmental and economic lever for Jordan.

3.4. Technological Challenges

Survey respondents identified three principal technical barriers to large–scale green-hydrogen deployment in Jordan: (i) renewable-energy integration, (ii) electrolyzer efficiency, and (iii) water-resource management. The following subsections present the quantitative findings that underpin each theme.

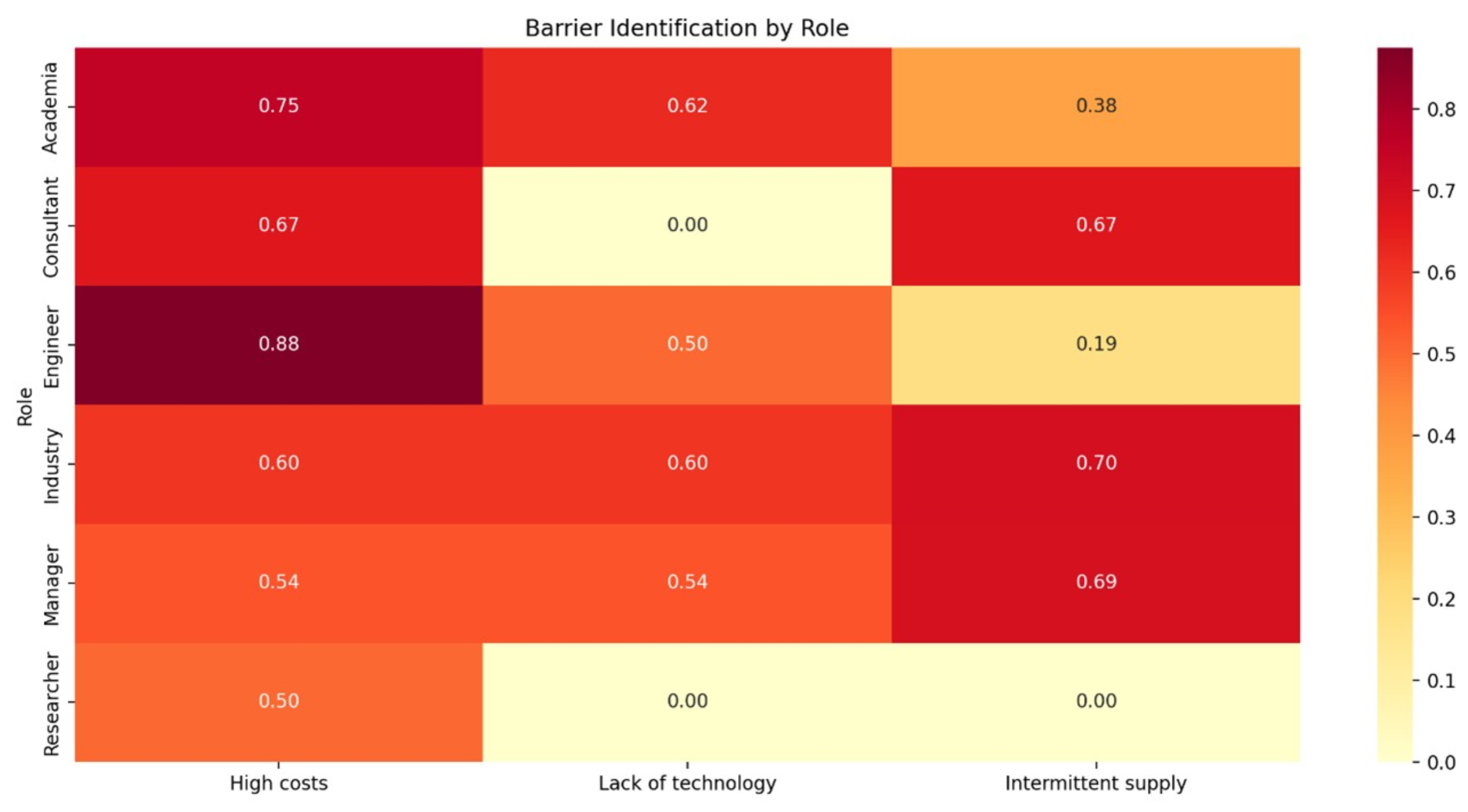

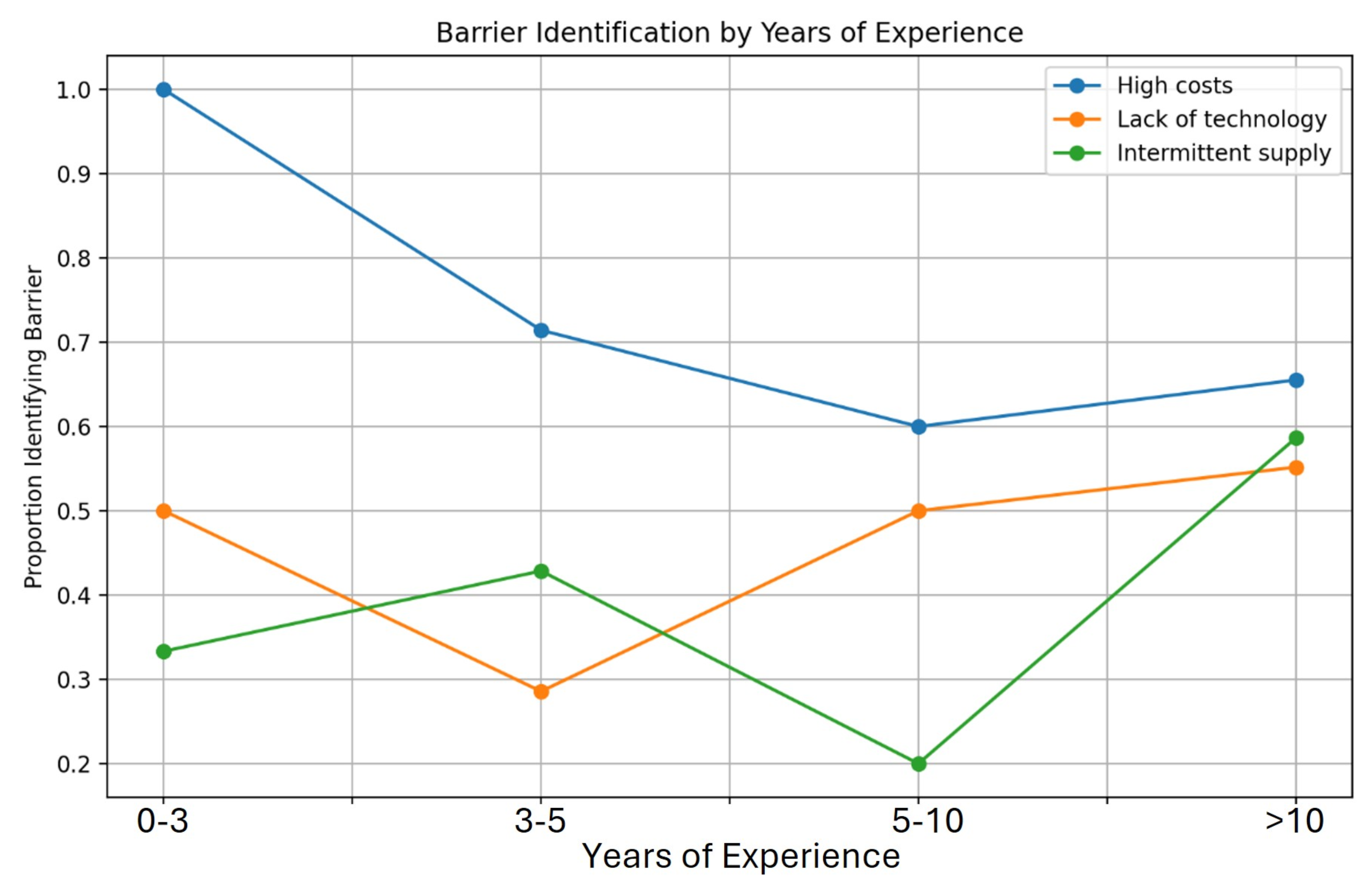

3.4.1. Renewable-Energy Integration

Overall sentiment toward the current effectiveness of renewable–hydrogen coupling was mixed: 36.5% of participants selected Neutral, while 28.8% rated it Effective. Three barriers dominated stakeholder concern:

Figure 5 shows how perceptions vary by professional role. Intermittency was strongly role-dependent

, whereas cost and technology concerns were broadly shared

.

Figure 5.

Barrier identification by Role.

Figure 5.

Barrier identification by Role.

Experience and knowledge further shape these views (

Figure 6Figure 7). Respondents with

years in the sector showed

agreement on the three fundamental barriers, while higher technical-knowledge scores significantly increased the likelihood of selecting

Technology Gaps.

Figure 6.

Barrier identification as a function of years of experience.

Figure 6.

Barrier identification as a function of years of experience.

Figure 7.

Barrier identification by self-reported knowledge level.

Figure 7.

Barrier identification by self-reported knowledge level.

Proposed technical remedies cluster around four options: advanced energy-management systems (31.5%), hybrid renewable portfolios (17.5%), battery storage (16.9%), and smart-grid upgrades (15.7%). Niche solutions—e.g. concentrated solar power and solar gasification—each attracted 0.6% support.

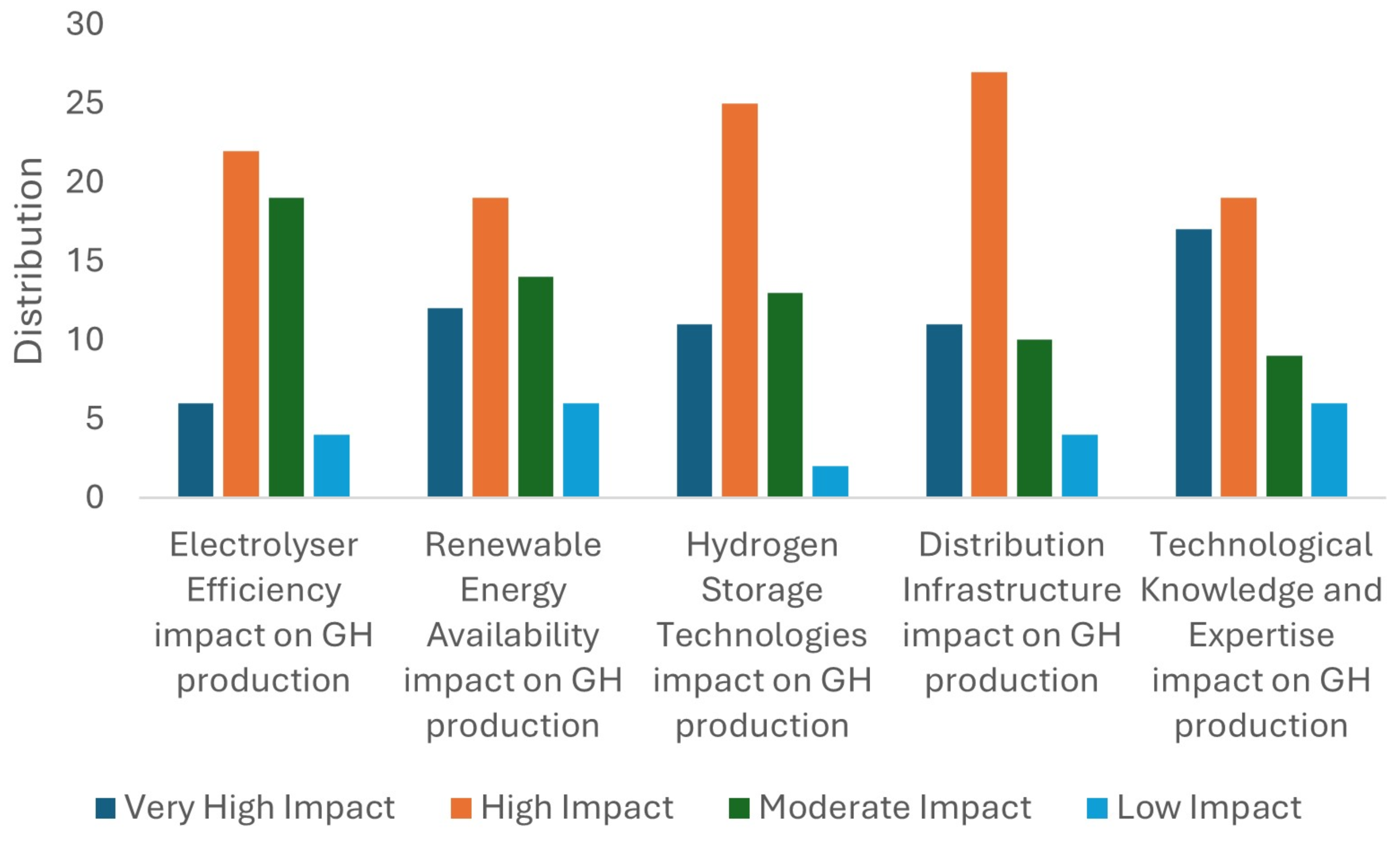

3.4.2. Electrolysis Technology

Figure 8 summarises stakeholder preferences for electrolyzer types and associated hurdles. Proton-Exchange-Membrane (PEM) units were deemed most suitable (

30%), marginally ahead of Alkaline Electrolysis (AEL) (

26%). Nearly half of the respondents (

44%) expressed no clear preference, signalling a need for greater technical outreach.

Figure 8.

Perceived impact of specific technological barriers.

Figure 8.

Perceived impact of specific technological barriers.

Key findings include:

Distribution infrastructure — highest-impact barrier (51.9%).

Hydrogen storage — next highest (48.1%).

Renewable availability rated Very High by 23.1%; electrolyzer efficiency by 11.5%.

Operational pain-points echo these themes: high operating costs (33%), energy consumption (30.6%), and efficiency limitations (20%). Uncertainty about true barriers remains for 10.6% of respondents—evidence of lingering knowledge gaps.

Suggested remedies prioritise R&D investment (36.6%) and broader technology advancement (34.7%), followed by increased capital investment (CAPEX) (24.8%).

3.4.3. Water-Resource Management

Water scarcity is nearly unanimous as a critical concern: 86% of respondents rated it Significant or Very Significant. Alternative water sources favoured are:

Technological solutions mirror these preferences. Desalination technologies led with 78.8% support, while improved water-use efficiency (21%), alternative sources (22%), and integrated water–energy strategies (16%) formed the secondary tier.

The data suggest that an integrated pathway—combining robust renewable supply, next-generation electrolysis, and coastal desalination—is considered the most viable route for Jordan’s hydrogen ambitions.

3.5. Infrastructure Challenges

Survey responses highlight substantial infrastructure gaps that must be bridged before Jordan can scale green-hydrogen deployment. Two domains emerged as the most pressing: grid compatibility and transport logistics.

3.5.1. Grid Compatibility

Respondents expressed limited confidence in the existing electrical grid’s readiness for large-scale electrolyzer integration. Fewer than one in ten (9.6%) deemed the grid compatible, and only 3.8% rated it highly compatible. The remainder described the grid as either slightly compatible (38.5%) or not compatible (23.1%). A chi-square test confirms that perceived compatibility is significantly associated with suggested remedies .

Key obstacles:

Insufficient investment — 40%

Needed grid upgrades — 36%

Technology limitations — 22%

Priority solutions:

Smart-grid deployment — 41%

Physical grid modernisation — 28%

Enhanced regulatory support — 28%

A minority of respondents advocated decentralised approaches (e.g. micro-grids, export-first strategies) to mitigate central-grid stress.

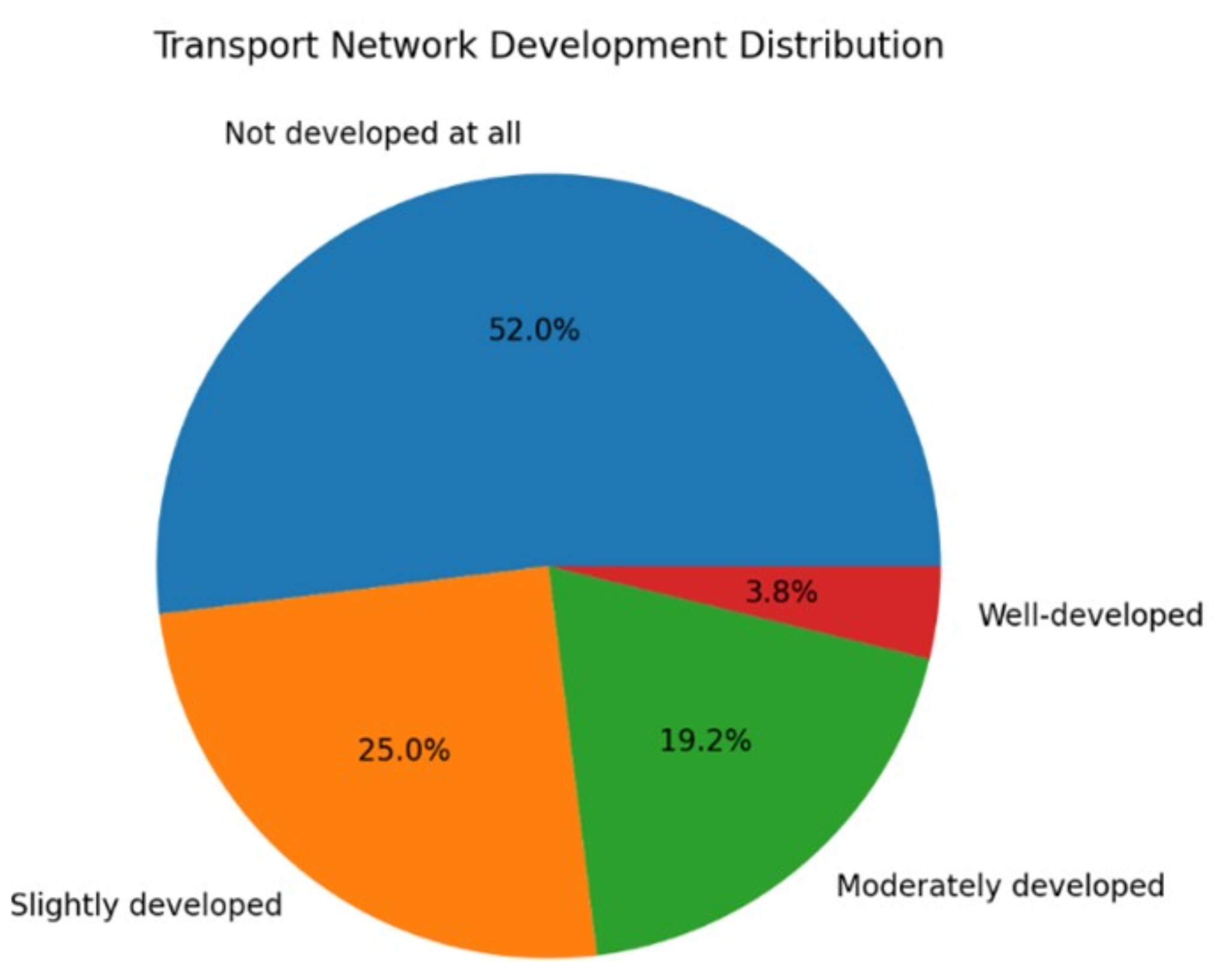

3.5.2. Transport-Network Development

Figure 9 summarises stakeholder assessments of hydrogen-transport readiness. Over half (

51.9%) reported

no network development, while only

3.8% judged current infrastructure

well-developed.

Figure 9.

Perceived maturity of Jordan’s hydrogen-transport infrastructure.

Figure 9.

Perceived maturity of Jordan’s hydrogen-transport infrastructure.

Principal barriers:

Proposed remedies:

Broad infrastructure investment — 84.7%

Storage-facility build-out — 71.2%

Advances in storage technology — 57.7%

Several respondents underscored Aqaba’s potential as an export node, suggesting an export-driven, phased approach: prioritizing port and pipeline upgrades to attract early investment and extending domestic distribution once volumes justify dedicated hydrogen lines.

The grid and transport findings depict an infrastructure ecosystem in its infancy. Stakeholders converge on large-scale investment and smart-technology deployment as necessary precursors to Jordan’s hydrogen rollout.

3.6. Economic Challenges

Stakeholders identified a multifaceted economic landscape in which high production costs, uncertain market demand, and limited access to finance constitute the primary hurdles to green-hydrogen deployment.

3.6.1. Production Costs

Cost perceptions followed a trimodal distribution. A cautiously optimistic minority (23.1%) classified levelized production costs as Very Low (7.7%) or Low (15.4%). The modal response was Moderate (34.6%), whereas 42.3% judged costs High (23.1%) or Very High (19.2%).

Three cost drivers dominated:

Technology-related capital items — 35%

Renewable-energy inputs — 34%

Resource scarcity (primarily water) — 26%

Suggested cost-reduction levers formed a balanced quartet: policy incentives (28%), technological improvements (26%), greater investment (24%), and economies of scale (22%).

3.6.2. Market Demand

Demand expectations were guarded. Only 5.8% of respondents rated market pull as Very Significant, while 34.6% chose Moderately Significant. A further 15.4% perceived demand as minimal.

Priority uptake sectors are:

Industry — 40%

Power generation — 34%

Transportation — 22%

Preferred demand-stimulation tools include subsidies (30%), regulatory support (28%), and tax incentives (26%); public-awareness campaigns were less favoured (15%).

3.6.3. Investment Climate and Financing

Only 11.5% of stakeholders deemed Jordan’s investment climate Very Attractive; 32.7% found it Moderately Attractive, and 26.9% Slightly Attractive. Key deterrents are:

Favoured financing instruments are tax breaks (71.2%), grants or subsidies (63.4%), and public–private partnerships (59.6%); streamlined regulation ranked fourth (46.2%).

Cross-tabulation reveals that respondents prioritising infrastructure investment (38%) are 22 percentage-points more likely to endorse PPPs, while those emphasising R&D (37%) show elevated preference for grant funding (31% versus the 26% baseline).

Qualitative feedback underscores an export-led vision: 18% of open-ended comments cite Jordan’s geographic advantage for serving European and Asian markets, whereas 12% remain sceptical of near-term international demand.

Overall, respondents converge on three financial imperatives:

Cost-reduction measures (cited by 35%) paired with targeted incentives (34%);

Regulatory alignment and risk mitigation (37%);

Coordinated infrastructure and financing strategies, frequently anchored in PPP models.

3.7. Summary of Key Findings

The quantitative evidence reveals (i) a mature, experienced stakeholder base, (ii) strong consensus on green-hydrogen importance across multiple end-use sectors, (iii) three dominant technical barriers—renewable integration, electrolyser performance, and water scarcity—and (iv) infrastructure and financial hurdles that remain unresolved. These results provide the empirical foundation for the subsequent Discussion, where policy, investment, and technology implications are examined in detail.

4. Discussion

The stakeholder survey reveals a complex interplay of technological, infrastructural, and economic challenges shaping the development of green hydrogen in Jordan. This discussion integrates those empirical insights with relevant literature to reflect on the country’s opportunities and constraints.

4.1. Technology and Infrastructure Alignment

Stakeholders favored Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolyzers over alkaline systems due to their compatibility with intermittent renewable energy, an important factor in a solar-dominant context like Jordan. This preference contrasts with certain techno-economic models prioritizing alkaline systems for lower capital costs, suggesting practitioners emphasize system responsiveness over initial expenditure.

Water scarcity emerged as a universal concern, frequently identified as a core barrier to hydrogen production. This concern differs from many theoretical assessments where water availability is considered a secondary issue. Respondents commonly supported seawater desalination as a mitigation strategy, reflecting Jordan’s geographic proximity to the Red Sea, though this approach introduces additional infrastructure and energy demands.

Confidence in the country’s grid infrastructure was limited, with most stakeholders viewing it as inadequate for supporting large-scale electrolyzer integration. Transport networks were also considered underdeveloped. Commonly cited barriers included insufficient investment, physical infrastructure gaps, and unresolved safety considerations.

4.2. Economic and Policy Perspectives

Stakeholders expressed mixed views on the economic feasibility of green hydrogen. Key cost drivers were identified as capital expenses (CAPEX) related to electrolyzer technologies, the cost of renewable energy inputs, and challenges related to water access. Respondents called for comprehensive solutions, including financial incentives, investment mobilization, technological innovation, and system scale and efficiency improvements.

Industrial and power-generation sectors were seen as the most viable entry points for green hydrogen adoption, with less emphasis on transportation. Although there is cautious optimism about the investment climate, stakeholders noted the need for greater regulatory clarity, improved access to finance, and mechanisms to manage investment risk. Preferred financial instruments included tax breaks, direct subsidies, and public–private partnerships.

4.3. Integrated Strategy and Outlook

The findings support an integrated, three-pillar framework for green hydrogen deployment in Jordan:

Technology–Infrastructure Nexus: Investment in renewable integration, electrolyzer deployment, grid modernization, and seawater desalination.

Economic–Policy Ecosystem: Deployment of targeted financial mechanisms and regulatory reforms to improve bankability and lower perceived risks.

Knowledge–Capacity Foundation: Development of technical expertise, institutional readiness, and inclusive stakeholder engagement.

This coordinated approach acknowledges the technical, economic, and policy progress interdependence. Advancing one dimension in isolation is unlikely to deliver transformative outcomes.

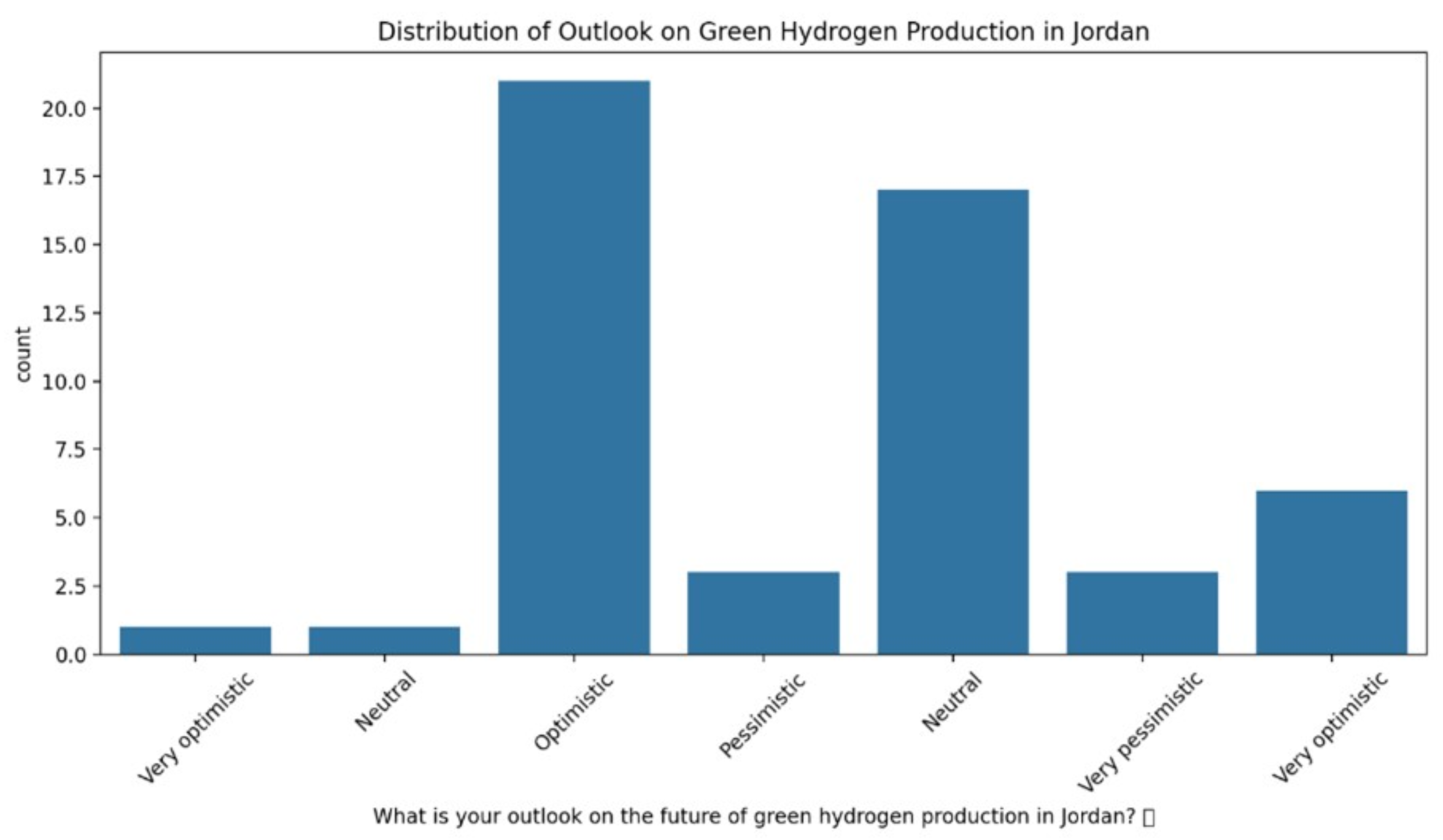

The survey findings also reveal that while stakeholders remain cautious about short-term deployment hurdles, their medium- to long-term outlook on hydrogen in Jordan is largely optimistic. As shown in

Figure 10, most respondents expressed positive expectations about the country’s capacity to develop a competitive green hydrogen sector, reinforcing the need for coordinated national planning and investment.

The findings reflect cautious optimism among stakeholders. Jordan’s abundant renewable resources and strategic location offer a foundation for regional leadership in hydrogen. Still, success will depend on sustained infrastructure investment, effective governance, and capacity building across the public and private sectors.

Figure 10.

Stakeholder outlook on the future of green hydrogen production in Jordan.

Figure 10.

Stakeholder outlook on the future of green hydrogen production in Jordan.

4.4. Comparative Analysis with Existing Studies

The results of our stakeholder-driven study align with and expand upon several existing assessments of green hydrogen development in Jordan. Across the literature, common challenges, such as renewable energy integration, electrolyzer efficiency, and water scarcity, are frequently cited. Our findings confirm these issues but further reveal how practitioners perceive them regarding urgency, interdependency, and practical feasibility.

Our study adds depth by directly capturing the views of energy-sector professionals, who consistently emphasize operational concerns like grid compatibility, infrastructure readiness, and gaps in regulatory and investment frameworks. These perspectives complement model-based studies, such as those by Gado et al. [

38], which rely on techno-economic projections without incorporating on-the-ground stakeholder input. For instance, while prior analyses suggest that water scarcity has a limited impact on hydrogen production costs, our respondents view it as a critical barrier, indicating a disconnect between modeled assumptions and stakeholder risk perceptions.

Similarly, the national-level analysis by Shboul et al. [

10] highlights the importance of a national strategy, international collaboration, and social acceptance—points that our respondents support. Still, it does not fully address operational barriers such as permitting delays, financial instrument preferences, or real-time grid limitations that emerged in our study.

The techno-economic modeling by Jaradat et al.[

4] provides valuable cost comparisons of ALK and PEM electrolyzers in Aqaba, identifying photovoltaic energy as the most economical source. Our findings support this conclusion while adding insight into perceived technical gaps, stakeholder knowledge levels, and investment bottlenecks not visible in simulation-based studies.

Unlike earlier studies focusing on long-term macroeconomic benefits, our results emphasize short-term priorities and practical enablers grounded in stakeholder-validated implementation needs, such as subsidies, PPPs, and regulatory clarity. This micro-level perspective extends existing literature by connecting strategic objectives to local operational realities, offering actionable insights for decision-makers.

5. Conclusions

This study comprehensively assesses Jordan’s green hydrogen landscape by analyzing stakeholder perspectives across the energy, policy, industry, and academic sectors. The findings reveal a cautiously optimistic outlook. While there is widespread recognition of Jordan’s potential, particularly in industrial applications and power generation, significant implementation barriers persist.

Technological limitations remain the most immediate concern. Respondents highlighted renewable intermittency, electrolyzer limitations, and water scarcity as dominant challenges. These technical constraints are compounded by infrastructural deficits, particularly in grid readiness and hydrogen transport infrastructure.

Economically, the sector faces cost-related hurdles that hinder scalability and competitiveness. However, stakeholders identified clear levers for improvement, including targeted policy incentives, technological advancements, and increased investment flows. The interdependence of these elements underscores the need for a coordinated strategy that simultaneously addresses cost, infrastructure, and technology.

Three strategic priorities emerge. First, infrastructure development must focus on grid modernization and storage systems. Second, robust policy frameworks should integrate financial incentives with regulatory stability. Third, international collaboration is essential for technology transfer and export market positioning.

Jordan’s natural advantages—abundant solar resources, growing renewable capacity, and strategic geographic location—can position the country as a regional leader in hydrogen development. Achieving this requires cross-sectoral coordination and integrated planning that advances infrastructure, policy, and innovation.

The study concludes that Jordan’s experience offers an instructive case for other middle-income economies navigating the clean energy transition. Future research should include international stakeholders, apply longitudinal and behavioral approaches, and compare hydrogen pathways across MENA countries. By addressing these practical and analytical gaps, Jordan can help shape a replicable model for green hydrogen deployment in resource-constrained contexts.

Short Biography of Authors

Hussam J. Khasawneh is an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering at Al Hussein Technical University (HTU), Jordan, and is also affiliated with the Mechatronics Engineering Department at The University of Jordan. He received his Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering from The Ohio State University, USA, in 2015. His research focuses on renewable energy systems, green hydrogen, automotive technologies, IoT-based monitoring, and sustainability. Dr. Khasawneh is an IEEE Senior Member and has led several internationally funded research and capacity-building projects. He previously served as the CEO of Jordan’s National Center for Innovation and held advisory roles at the Higher Council for Science and Technology.

Rawan A. Maaitah is the Chemistry Laboratory Supervisor at the Marine Science Station, a joint facility of The University of Jordan and Yarmouk University in Aqaba, Jordan. She holds a B.Sc. in Chemical Engineering from Mutah University and an M.Sc. in Engineering Management. Her professional experience spans seawater quality monitoring, sediment analysis, and pollution studies. Her research interests include environmental sustainability and green hydrogen production, with active participation in national and regional projects addressing marine ecosystem health and renewable energy transitions.

Ahmad AlShdaifat is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Al al-Bayt University, Jordan, where he also serves as Assistant Dean and Head of Department. He earned his Ph.D. in Quaternary Sedimentology from The University of Nottingham, UK. Dr. AlShdaifat is a senior sedimentologist and palaeoenvironmentalist with over a decade of experience in palaeoclimatic reconstruction, environmental statistics, and sedimentary analysis. He has contributed to multiple projects on water resources management and the reuse of treated wastewater.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.K. and R.A.M.; Methodology, H.J.K. and R.A.M.; Software, A.A.; Validation, H.J.K., R.A.M. and A.A.; Formal Analysis, A.A.; Investigation, H.J.K. and R.A.M.; Resources, H.J.K.; Data Curation, R.A.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.J.K., R.A.M. and A.A.; Writing—review and editing, H.J.K. and R.A.M.; Visualization, A.A.; Supervision, H.J.K.; Project Administration, H.J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PEM |

Proton Exchange Membrane |

| AEL |

Alkaline Electrolyzer |

| AEM |

Anion Exchange Membrane |

| LCOH |

Levelized Cost of Hydrogen |

| PPP |

Public–Private Partnership |

| R&D |

Research and Development |

| GW |

Gigawatt |

| kWh |

Kilowatt-hour |

| H2

|

Hydrogen |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| CAPEX |

Capital Expenditure |

| OPEX |

Operational Expenditure |

| EU |

European Union |

References

- Times, J. Jordan secures top spot in renewable energy capacity, with potential to grow — Kharabsheh. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-secures-top-spot-renewable-energy-capacity-potential-grow-%E2%80%94-kharabsheh, 2024.

- Times, J. Jordan leads Arab world in renewable energy production, says Kharabsheh. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-leads-arab-world-renewable-energy-production-says-kharabsheh, 2024.

- Abu-Rumman, G.; Khdair, A.I.; Khdair, S.I. Current status and future investment potential in renewable energy in Jordan: An overview. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaradat, M.; Alsotary, O.; Juaidi, A.; Albatayneh, A.; Alzoubi, A.; Gorjian, S. Potential of Producing Green Hydrogen in Jordan. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, M.; Han, D.S. Efficient solar-powered PEM electrolysis for sustainable hydrogen production: An integrated approach. Emergent Materials 2024, 7, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasree, S.; Hemamalini, V.; Bansal, S.; Al-Farouni, M.; Chaudhari, R.; Landage, M.; Babu, D.S. Integrated Fuel Cell and Electrolyzer Systems for Renewable Energy Storage and Conversion. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2024, Vol. 591, p. 05004.

- Kuterbekov, K.A.; Kabyshev, A.; Bekmyrza, K.; Kubenova, M.; Kabdrakhimova, G.; Ayalew, A.T. Innovative approaches to scaling up hydrogen production and storage for renewable energy integration. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 2024, 19, 2234–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghussain, L.; Ahmad, A.D.; Abubaker, A.M.; Hassan, M.A. A country-scale green energy-water-hydrogen nexus: Jordan as a case study. Solar Energy 2024, 269, 112301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novosel, T.; Ćosić, B.; Pukšec, T.; Krajačić, G.; Duić, N.; Mathiesen, B.; Lund, H.; Mustafa, M. Integration of renewables and reverse osmosis desalination – Case study for the Jordanian energy system with a high share of wind and photovoltaics. Energy 2015, 92, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shboul, B.; Zayed, M.E.; Marashdeh, H.F.; Al-Smad, S.N.; Al-Bourini, A.A.; Amer, B.J.; Qtashat, Z.W.; Alhourani, A.M. Comprehensive assessment of green hydrogen potential in Jordan: economic, environmental and social perspectives. International Journal of Energy Sector Management 2024, 18, 2212–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analytica, O. Jordan’s green hydrogen plans will face challenges. Expert Briefings 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S. Hydrogen as a clean and sustainable energy for green future. Sustainable technologies for green economy 2021, 1, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganza, A.; Gabetti, A.; Pastorino, P.; Zanoli, A.; Sicuro, B.; Barcelò, D.; Esposito, G. Toward Sustainability: An Overview of the Use of Green Hydrogen in the Agriculture and Livestock Sector. Animals 2023, 13, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Jumah, A. A comprehensive review of production, applications, and the path to a sustainable energy future with hydrogen. RSC advances 2024, 14, 26400–26423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Times, T.J. Report sheds light on Power X and green hydrogen opportunities in Jordan. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/report-sheds-light-power-x-green-hydrogen-opportunities-jordan, 2024.

- Muhsen, H.; Al-Mahmodi, M.; Tarawneh, R.; Alkhraibat, A.; Al-Halhouli, A. The Potential of Green Hydrogen and Power-to-X Utilization in Jordanian Industries: Opportunities and Future Prospects. Energies 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatatneh, A. Jordan intensifies green hydrogen efforts with major int’l partnerships. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-intensifies-green-hydrogen-efforts-major-intl-partnerships, 2024.

- of Energy, M.; Resources, M. Projects ER 2021. https://www.memr.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/EN/Project/projectsEr2021.pdf, 2021.

- Khasawneh, H.; Saidan, M.N.; Al-Addous, M. Utilization of hydrogen as clean energy resource in chlor-alkali process. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2019, 37, 1053–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T. Scaling Production of Green Hydrogen with Water Electrolysis. Power Magazine 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abdin, Z.; Mérida, W. Hybrid energy systems for off-grid power supply and hydrogen production based on renewable energy: A techno-economic analysis. Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 196, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Research progress of hydrogen production technology and related catalysts by electrolysis of water. Molecules 2023, 28, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authors, V. Green hydrogen production for sustainable development: a critical review. RSC Sustainable Development 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, W.; Qi, W. Hydrogen production technology by electrolysis of water and its application in renewable energy consumption. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, Vol. 236; 2021; p. 02001. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.C.; Gu, R.E.; Chan, Y.H. Parameter Analysis of Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis System by Numerical Simulation. Energies 2024, 17, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- of Water, M.; Irrigation, J. National Water Strategy 2023-2040: Summary (English Version). https://www.mwi.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/AR/EB_Ticker/National_Water_Strategy_2023-2040_Summary-English_-ver2.pdf, 2023.

- Touili, S.; Merrouni, A.A.; El Hassouani, Y.; Amrani, A.I.; Rachidi, S. Analysis of the yield and production cost of large-scale electrolytic hydrogen from different solar technologies and under several Moroccan climate zones. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 26785–26799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenk, G.; Reichelstein, S. Economics of converting renewable power to hydrogen. Nature Energy 2019, 4, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- of Energy, U.D. Hydrogen production: Electrolysis. https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-production-electrolysis. Accessed: 2025-05-05.

- News, E. Jordan aims to lead in green hydrogen production. https://energynews.biz/jordan-aims-to-lead-in-green-hydrogen-production/, 2024.

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. Green hydrogen: A pathway to a sustainable energy future. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 310–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIZ. Sector Analysis – Jordan. Technical report, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, 2023.

- Al-Khalidi, S. Jordan takes strides towards green ammonia production with four key MOUs. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-takes-strides-towards-green-ammonia-production-four-key-mous, 2023.

- PtX Hub. Jordan - PtX Hub. https://ptx-hub.org/jordan/, 2025.

- Jordan Times. Jordan moves forward with green hydrogen strategy, eyes int’l clean energy role. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-moves-forward-green-hydrogen-strategy-eyes-intl-clean-energy-role, 2025.

- Yap, J.; McLellan, B. Exploring transitions to a hydrogen economy: quantitative insights from an expert survey. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 66, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Hayakawa, A.; Somarathne, K.K.A.; Okafor, E.C. Science and technology of ammonia combustion. Proceedings of the combustion institute 2019, 37, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gado, M.G. Techno-economic-environmental assessment of green hydrogen production for selected countries in the Middle East. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

Hussam J. Khasawneh is an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

at Al Hussein Technical University (HTU), Jordan, and is also affiliated with the Mechatronics Engineering Department at The University of Jordan. He received his Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering from The Ohio State University, USA, in 2015. His research focuses on renewable energy systems, green hydrogen, automotive technologies, IoT-based monitoring, and sustainability. Dr. Khasawneh is an IEEE Senior Member and has led several internationally funded research and capacity-building projects. He

previously served as the CEO of Jordan’s National Center for Innovation

and held advisory roles at the Higher Council for Science and Technology. Hussam J. Khasawneh is an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

at Al Hussein Technical University (HTU), Jordan, and is also affiliated with the Mechatronics Engineering Department at The University of Jordan. He received his Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering from The Ohio State University, USA, in 2015. His research focuses on renewable energy systems, green hydrogen, automotive technologies, IoT-based monitoring, and sustainability. Dr. Khasawneh is an IEEE Senior Member and has led several internationally funded research and capacity-building projects. He

previously served as the CEO of Jordan’s National Center for Innovation

and held advisory roles at the Higher Council for Science and Technology. |

Rawan A. Maaitah is the Chemistry Laboratory Supervisor at the Marine

Science Station, a joint facility of The University of Jordan and Yarmouk

University in Aqaba, Jordan. She holds a B.Sc. in Chemical Engineering

from Mutah University and an M.Sc. in Engineering Management. Her

professional experience spans seawater quality monitoring, sediment analysis,

and pollution studies. Her research interests include environmental

sustainability and green hydrogen production, with active participation

in national and regional projects addressing marine ecosystem health and

renewable energy transitions. Rawan A. Maaitah is the Chemistry Laboratory Supervisor at the Marine

Science Station, a joint facility of The University of Jordan and Yarmouk

University in Aqaba, Jordan. She holds a B.Sc. in Chemical Engineering

from Mutah University and an M.Sc. in Engineering Management. Her

professional experience spans seawater quality monitoring, sediment analysis,

and pollution studies. Her research interests include environmental

sustainability and green hydrogen production, with active participation

in national and regional projects addressing marine ecosystem health and

renewable energy transitions. |

Ahmad AlShdaifat is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental

Sciences, Al al-Bayt University, Jordan, where he also serves as

Assistant Dean and Head of Department. He earned his Ph.D. in Quaternary

Sedimentology from The University of Nottingham, UK. Dr. AlShdaifat is a

senior sedimentologist and palaeoenvironmentalist with over a decade of

experience in palaeoclimatic reconstruction, environmental statistics, and

sedimentary analysis. He has contributed to multiple projects on water

resources management and the reuse of treated wastewater. Ahmad AlShdaifat is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental

Sciences, Al al-Bayt University, Jordan, where he also serves as

Assistant Dean and Head of Department. He earned his Ph.D. in Quaternary

Sedimentology from The University of Nottingham, UK. Dr. AlShdaifat is a

senior sedimentologist and palaeoenvironmentalist with over a decade of

experience in palaeoclimatic reconstruction, environmental statistics, and

sedimentary analysis. He has contributed to multiple projects on water

resources management and the reuse of treated wastewater. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Hussam J. Khasawneh is an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

at Al Hussein Technical University (HTU), Jordan, and is also affiliated with the Mechatronics Engineering Department at The University of Jordan. He received his Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering from The Ohio State University, USA, in 2015. His research focuses on renewable energy systems, green hydrogen, automotive technologies, IoT-based monitoring, and sustainability. Dr. Khasawneh is an IEEE Senior Member and has led several internationally funded research and capacity-building projects. He

previously served as the CEO of Jordan’s National Center for Innovation

and held advisory roles at the Higher Council for Science and Technology.

Hussam J. Khasawneh is an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

at Al Hussein Technical University (HTU), Jordan, and is also affiliated with the Mechatronics Engineering Department at The University of Jordan. He received his Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering from The Ohio State University, USA, in 2015. His research focuses on renewable energy systems, green hydrogen, automotive technologies, IoT-based monitoring, and sustainability. Dr. Khasawneh is an IEEE Senior Member and has led several internationally funded research and capacity-building projects. He

previously served as the CEO of Jordan’s National Center for Innovation

and held advisory roles at the Higher Council for Science and Technology. Rawan A. Maaitah is the Chemistry Laboratory Supervisor at the Marine

Science Station, a joint facility of The University of Jordan and Yarmouk

University in Aqaba, Jordan. She holds a B.Sc. in Chemical Engineering

from Mutah University and an M.Sc. in Engineering Management. Her

professional experience spans seawater quality monitoring, sediment analysis,

and pollution studies. Her research interests include environmental

sustainability and green hydrogen production, with active participation

in national and regional projects addressing marine ecosystem health and

renewable energy transitions.

Rawan A. Maaitah is the Chemistry Laboratory Supervisor at the Marine

Science Station, a joint facility of The University of Jordan and Yarmouk

University in Aqaba, Jordan. She holds a B.Sc. in Chemical Engineering

from Mutah University and an M.Sc. in Engineering Management. Her

professional experience spans seawater quality monitoring, sediment analysis,

and pollution studies. Her research interests include environmental

sustainability and green hydrogen production, with active participation

in national and regional projects addressing marine ecosystem health and

renewable energy transitions. Ahmad AlShdaifat is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental

Sciences, Al al-Bayt University, Jordan, where he also serves as

Assistant Dean and Head of Department. He earned his Ph.D. in Quaternary

Sedimentology from The University of Nottingham, UK. Dr. AlShdaifat is a

senior sedimentologist and palaeoenvironmentalist with over a decade of

experience in palaeoclimatic reconstruction, environmental statistics, and

sedimentary analysis. He has contributed to multiple projects on water

resources management and the reuse of treated wastewater.

Ahmad AlShdaifat is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental

Sciences, Al al-Bayt University, Jordan, where he also serves as

Assistant Dean and Head of Department. He earned his Ph.D. in Quaternary

Sedimentology from The University of Nottingham, UK. Dr. AlShdaifat is a

senior sedimentologist and palaeoenvironmentalist with over a decade of

experience in palaeoclimatic reconstruction, environmental statistics, and

sedimentary analysis. He has contributed to multiple projects on water

resources management and the reuse of treated wastewater.